Abstract

This study investigated the impact of different temperatures and durations on the structural and emulsifying properties of copra meal protein. Additionally, the stability of copra meal protein Pickering emulsions was assessed through rheological and interfacial characteristics. Findings revealed a positive correlation between emulsification properties and heating temperature and duration. Thermal aggregates, facilitated by hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and disulfide bonds, significantly enhanced surface hydrophobicity. Heat-treated copra meal protein-based Pickering emulsions demonstrate enhanced adsorption at the oil-water interface and resistance to diffusion. The three-phase contact angle increases from 57.7° to 79.8° following heating at 95 °C for 30 min. The addition of NaCl and heating treatment did not affect emulsion particle size or interface adsorption ability. But it improved the rheological properties to varying degrees. These results offer valuable insights for optimizing the physicochemical and functional attributes of copra meal protein in the food industry.

Keywords: Copra meal protein, Heat treatment, Pickering emulsion, Interfacial properties, Stability

Highlights

-

•

Heat treatment improved the functional properties of copra meal protein.

-

•

The adsorption percentage of heat induced copra meal protein reached to 89.36%.

-

•

Pickering emulsions produced with heated copra meal protein remain stable.

1. Introduction

Emulsions have wide-ranging applications across sectors such as food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetics industries. Traditional emulsions stabilize the oil-water interface with surfactant molecules, while Pickering emulsions involve solid particles adsorbed at the oil-water interface. In comparison to traditional emulsions, Pickering emulsions are characterized by particles that undergo irreversible adsorption at the oil-water interface, thereby forming an interfacial membrane. This phenomenon imparts enhanced resistance to coalescence and ensures long-term stability (Dai, Chen, Fu, Wang, & Zhang, 2023). Consequently, Pickering emulsions exhibit greater potential for development compared to traditional emulsions. As the demand for safe and healthy food continues to rise, there has been a growing focus on employing environmentally friendly and safe biomacromolecules, including protein and polysaccharides, in the Pickering particles research (Phosanam, Moreira, Adhikari, Adhikari, & Losso, 2023). This trend is gradually supplanting the utilization of inorganic materials such as SiO2. Plant proteins emerge as particularly viable candidates for future Pickering particles, owing to their cost-effectiveness and reduced environmental footprint (Graca, Raymundo, & de Sousa, 2016).

Coconuts are crucial tropical and subtropical crops with substantial economic importance. Coconut protein boasts a well-balanced amino acid composition, rendering it highly nutritious and holding great promise for promoting health and preventing diseases (Thaiphanit & Anprung, 2016). Copra meal, the byproduct of coconut oil extraction, has been produced on a massive scale but is often used as low-cost animal feed or wasted. Copra meal could serve as a significant source of new plant protein due to its high protein content ranging from 15% to 25% (Rodsamran & Sothornvit, 2018). Nevertheless, the inferior emulsifying properties of copra meal protein (CMP) compared to proteins such as soybean protein limit its application in the food industry (Qianqian Zhu et al., 2024).

Efforts to extract proteins from coconut-related materials and enhance their functional properties using physical, chemical, or biological methods have garnered significant attention. For instance, Sun et al. (2022) employed high-intensity ultrasound and pH-shift treatment to enhance the heat stability of coconut milk, particularly under alkaline pH-shift treatment. Chen et al. (2023) utilized non-covalent interaction between polyphenols and coconut globulin to successful prepare high internal phase Pickering emulsions (HIPPE). Additionally, notable advancements have been made in enhancing the emulsifying properties of coconut protein through polysaccharide complexes (Zhou et al., 2021). Recent studies have also explored the use of pulsed light (Qianqian Zhu et al., 2024) and plasma technologies (Chen, Chen, Fang, Pei, & Zhang, 2024) for function improvement of coconut protein. However, the coconut protein discussed in prior research originates from fresh coconut meat or coconut milk, differing in composition from CMP. There remains a scarcity of information regarding the structure-function relationship in CMP, underscoring the importance of enriching the foundational research in this area.

Heat treatment is a widely employed method in food processing that can effectively modify proteins and thereby alter their functional properties. When subjected to heat, proteins undergo unfolding, thereby exposing hydrophobic groups within their structure and inducing functional changes. Li's research demonstrated that heat treatment heightened the foamability, emulsification, and digestibility of Phaseolus vulgaris L. protein (Li, Tian, Liu, Dou, & Diao, 2023). Similar results have been extensively reported for soybean (Liu et al., 2020) and pea proteins (Shand, Ya, Pietrasik, & Wanasundara, 2007). However, excessive heat treatment may also lead to a decline in the functional attributes of proteins (Chao & Aluko, 2018). The selection of appropriate temperature and duration is crucial for enhancing the functional properties of proteins.

This study aimed to investigate the effect of heat temperature and duration on the structural and emulsifying properties of CMP aggregates and CMP-based Pickering emulsion. The CMP aggregates were analyzed for tertiary structure, secondary structure, surface hydrophobicity, wettability and emulsification. The stability of the emulsions prepared from CMP and heat-treated CMP was assessed through rheological and interfacial property analysis, elucidating the correlation between interfacial properties and emulsion stability. The objective is to provide a theoretical basis and technical guidance for the application of CMP in food processing.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

The copra meal was purchased from Hainan YeZeFang Company. The MCT (octanoic acid: decanoic acid = 7:3) was obtained from Guangzhou Yongyi Food Materials Co., Ltd., China. All the chemicals utilized in this study were of analytical grade.

2.2. CMP preparation

The defatted copra meal was dissolved in 0.1 mol L−1 phosphate buffer (PB) with pH 10. Following hydration at 4 °C for 12 h, the sample was centrifuged at 7654 ×g for 15 min. Subsequently, the supernatant was obtained using a 400-mesh nylon cloth. The pH of the supernatant was adjusted to 3.5 using 1 mol L−1 HCl, followed by 1.5 h of settling. Afterward, the sample was centrifuged at 7654 ×g for 15 min to obtain the protein precipitate. The protein precipitate underwent dialysis and lyophilization before storage for subsequent use.

2.3. CMP aggregate preparation and determination

2.3.1. CMP aggregate preparation

The CMP aggregate was prepared followed by Zhang, Liang, Tian, Chen and Subirade (2012) with slight modification. Initially, the CMP was dissolved in 0.1 mol L−1 PB with a pH of 7. Subsequently, the mixture was magnetically stirred at 25 °C for 2 h, followed by overnight hydration at 4 °C. After hydration, the mixture underwent centrifugation at 2990 ×g for 15 min, with the precipitate subsequently removed via filtration through a 400-mesh gauze to obtain a clarified solution. The protein concentration in the supernatant was measured using the Bradford assay and subsequently adjusted to 10 mg mL−1 using 0.1 mol L−1 PB at pH 7. After that, the samples were heated at different temperatures (65 °C, 75 °C, 85 °C, 95 °C) for 30 min. Furthermore, another group of samples were heated at 95 °C for varying durations (5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 min). Post-heat treatment, the samples were promptly cooled to ambient temperature in an ice bath and subsequently stored at 4 °C for further analysis.

2.3.2. Particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and ζ-potential of CMP

The samples were diluted using deionized water to 1 mg mL−1 and adjusted to pH 7. Subsequently, the particle size distribution, PDI, ζ-potential and were measured with Zetasizer Nano ZSE (Malvern Instruments Ltd., British). The parameters were set with temperature is 25 °C, refractive index of 1.330, and particle refractive index of 1.414.

2.3.3. Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS)

The sample was diluted to 5 mg mL−1 using 0.1 mol L−1 PB at pH 7. SAXS analysis was conducted utilizing Nano-in Xider (Xenocs, France), positioning the sample 938 mm distant from the small-angle detector. Each sample was scanned for 15 times, with the background signal from the buffer subtracted, to obtain the average value at 25 °C.

2.3.4. Transmission electron microscopy

Following the method of Chen et al. (2023), the samples was diluted to 0.01 mg mL−1 and subsequently placed on a copper grid for natural drying. 1% phosphotungstic acid dye were applied with 5 drops, left for 2 min, and excess dye was absorbed using filter paper. This staining process will be repeated thrice with deionized water to ensure the removal of any surplus dye. Finally, the morphology of the samples was observed using TEM (HT7830, HITACHI, Japan).

2.3.5. Measurement of the fluorescence emission spectra

The fluorescence measurements were conducted according to the method of Chen et al. (2023). Sample was diluted to 0.1 mg mL−1 using 0.1 mol L−1 PB with pH 7. The determination was applied to avoid inner filter effects. The intrinsic fluorescence spectra, with the Ex 280 nm, slit width of 2.5 nm, voltage of 700 V, and scan rate of 1200 nm min−1, were measured to characterize the changes in its tertiary structure (F-7000, HITACHI, Japan).

2.3.6. Measurement of fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

According to Tian et al. (2023), the sample powder was freeze-dried and blended with dried KBr in a ratio of 1:100. The mixture was then compacted to form a transparent sheet with 2 mm in thickness. Subsequently, the sample was scanned with the spectral range of 4000–400 cm−1 (at a resolution of 4 cm−1) by Using infrared spectroscopy (T-27, BRUKER). Furthermore, the secondary structure alterations were analyzed through band allocation using Peak Fit 4.12 according to the method of Chen et al. (2023).

2.3.7. Measurement of sulfhydryl content

The total sulfhydryl group, free sulfhydryl group, and disulfide bond content of the samples were determined following the method by Guo et al. (2021).

2.3.8. Measurement of the surface hydrophobicity index (H0)

The measurement of H0 was conducted by the method of Tian et al. (2023). Specifically, an 8 mmol L−1 8-Anilino-1-naphthalenesulfonic acid (ANS−) solution was prepared in a pH 7, 0.1 mol L−1 PB utilizing ANS− as a hydrophobic probe. Samples were then diluted to concentrations of 0.2 mg mL−1, 0.4 mg mL−1, 0.6 mg mL−1, 0.8 mg mL−1, and 1 mg mL−1 using 0.1 mol L−1 PB, respectively. Each sample with 5 mL was mixed with 40 μL of ANS− and allowed to stand shielded from light for 15 min. The fluorescence intensity was measured using a fluor spectrophotometer, employing an excitation wavelength of 390 nm, a slit width of 2.5 nm, and a voltage of 700 V. The initial slope of the curve obtained by plotting protein concentration against fluorescence intensity was utilized as H0.

2.3.9. Measurement of contact angle

The contact angle was determined using the sessile drop method by OSA instrument (OT100, Ningbo NB Scientific Instruments Co., Ltd., Ningbo, China). Initially, protein powder was compacted into thin sheets of approximately 2 mm. These sheets were then placed in a container filled with MCT oil, and a droplet of 5 μL deionized water was dispensed onto each sheet using a needle. The contact angle was calculated using the Laplace-Young equation, as described by Xiao et al. (2022).

2.3.10. Measurement of Interfacial pressure (π)

The interfacial tension between Unheated-CMP and heated-CMP at 95 °C for 30 min was measured using the pendant drop method, employing the OSA (OT100, Ningbo NB Scientific Instruments Co., Ltd., Ningbo, China). In this procedure, a needle was submerged in MCT oil, suspending a 20 μL droplet of 1% protein solution, and the variations in interfacial tension over a period of 10,800 s were recorded, with measurements taken at 10 s intervals (Tao et al., 2024). The density of MCT oil was determined to be 0.9398 g cm−3, while the density of the protein solution was measured to be 1.0048 g cm−3. All measurements were conducted at ambient temperature.

| (1) |

| (2) |

While, as the C for the capillary constant, delta for the sample solution with the density difference between oil phase, g is the acceleration of gravity. The values σ1 and σ0 denote the interfacial tension of the samples and the buffer, respectively.

2.3.11. Emulsion activity and emulsion stability

According to Guo et al. (2021), the sample was diluted to a concentration of 0.5 mg mL−1 using 0.1 mol L−1 PB. It's mixed with MCT at a ratio of 1:4 and homogenized using IKA T25 (IKA T25, 10 N, German) at 20,000 rpm for 1 min. Take 5 μL of the Pickering emulsion and dilute it 200-fold with 0.1% Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Measure the OD500 using a UV–visible spectrophotometer, and record it as A0. After 30 min, measure it again and record it as A30. The calculation method for the emulsification activity index (EAI) and emulsion stability index (ESI) is as follows:

| (3) |

| (4) |

Among them, the DF for diluted multiples (×200); c is the sample concentration (g mL−1); φ is the passing optical path (1 cm) and θ is the oil phase ratio (0.20). Where ∆t = 30 min.

2.4. Preparation and characterization of Pickering emulsions

The Pickering emulsion specimens were derived from unheated or heated (95 °C, 30 min) CMP aggregates, spanning a range of protein concentrations from 0.1% to 1% (w:v), and MCT volumes varying from 20% to 80% (v:v). Initially, MCT was blended with CMP aggregate dispersions, followed by homogenization at 10000 rpm for 1 min utilizing a high-shear homogenizer (IKA T25, S25N, German). Subsequently, the Pickering emulsion samples, with the exception of those containing 80% oil, underwent processing at a pressure of 55 MPa using a microfluidizer (NanoGenizer30k, the United States). The Pickering emulsion was then stored in a refrigerated environment at 4 °C for subsequent testing. To inhibit microbial growth, 0.02% thimerosal sodium was introduced into the Pickering emulsion.

2.4.1. Measurement of the Pickering emulsion's particle size and ζ-potential

According to the method of Shen, Wu, Zhao and Zhou (2024) and modified slightly. The particle size distribution of Pickering emulsion was determined using the laser diffraction method by Particle sizer (MAZ3000, Malvern Instruments Ltd., British). Initially, a 1% SDS solution was poured into the sample chamber of the particle sizer to prevent droplet flocculation. Subsequently, the Pickering emulsion will be added to attain an obscuration level falling within the range of 8% to 12%. The refractive index of the sample is determined to be 1.414, while the medium refractive index is 1.333. All measurements will be conducted under ambient conditions.

Dilute the Pickering emulsion 500-fold with deionized water at pH 7. Use a Zetasizer Nano ZSE to measure its ζ-potential. Allow the system to equilibrate for 120 s (Qiaomei Zhu, Li, Li, & Wang, 2020).

2.4.2. Measurement of rheological property

Using a rheometer (HAAKE MARS40, Thermo Fisher), select parallel plates with a diameter of 35 mm and a sample measurement gap of 1 mm. Set the stress at 0.1% and conduct a frequency sweep in the range of 0.1–10 Hz to obtain the sample's loss modulus (G") and storage modulus (G'). Measure the apparent viscosity of the sample within the shear rate range of 0.01 s−1-100 s−1. The measurements will be performed at a temperature of 25 °C (Qiaomei Zhu et al., 2020).

2.4.3. Measurement of storage stability

To conduct a phase emulsion analysis index, the Pickering emulsion storage glass bottles were refrigerated at 4 °C. The initial height of the Pickering emulsion (H0) was recorded along with the height after serum layer (H1), then calculated the creaming index (CI). Photos were taken during the process to keep a record of the Pickering emulsion's status.

| (5) |

2.4.4. Measurement of interface protein adsorbed percentage (AP) and concentration (Γ)

To separate water and Pickering emulsion, centrifuge the Pickering emulsion for 5 min at 7654 ×g. This will divide the Pickering emulsion into an upper layer and a lower layer consisting of water. Extract the water layer with a syringe from the bottom, pass it through a 0.45 μm membranes, and measure the protein concentration (C1). Use the initial protein concentration (C0) for comparison (Chen et al., 2023).

| (6) |

| (7) |

Among them, d3, 2 is 1% SDS data for the determination of dispersed phase, θ as oil phase volume fraction.

2.4.5. Measurement of confocal laser scanning microscopy

Following the method of Ko and Kim (2021), prepare a 0.1% acetone solution of Nile red and Nile blue. Add 1 mL of the Pickering emulsion to 20 μL of the mixed dye solution, mix evenly in the dark overnight, and spot 5 μL of the sample on a slide. Obtain confocal microscopy images using 561 nm and 633 nm excitation sources (A1RHD25+ N-SIM + N-STORM, Nikon Corporation). Nile Red imparts a red colour to the MCT, while Nile Blue dyes the protein green.

2.4.6. Effect of salt ion concentration on Pickering emulsions

Preparing a 20% MCT Pickering emulsion with the oil phase volume using the section 2.4 method and a 1% protein concentration. Next, add NaCl solids to the Pickering emulsion, making its concentration reaches 0 mM, 200 mM, 400 mM, 600 mM, and 800 mM, respectively. Measure the particle size, potential, viscosity, frequency sweep, and creaming index of the Pickering emulsions. Analyze the impact of salt ion strength on the Pickering emulsions.

2.4.7. Thermal stability of the Pickering emulsions

The thermal stability of the Pickering emulsion with 1% CMP and 20% (v/v) MCT was studied. Specifically, the Pickering emulsion underwent heating at temperatures ranging from 40 °C to 100 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, cooling the samples to 25 °C, the assessments were carried out, including the particle size, ζ-potential, viscosity, frequency sweep and creaming index of the samples.

2.5. Data analysis

The tests were repeated three times and the data was analyzed by SPSS. The results are presented as an average ± SD, and Duncan's multiple range test was used to identify significant differences (p < 0.05) between the groups of the company. The pictures were drawn by origin 22.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Structure and characterization of the samples

3.1.1. The CMP particle size, PDI and ζ-potential

Fig. 1a and b illustrate the particle size and Polydispersity Index (PDI) outcomes of CMP aggregates subjected to varying heat treatments. Comparative analysis revealed that thermal treatment induced a notable increase in the average size of the aggregates while concurrently reducing PDI values in the samples. This observation suggested that thermal processing promoted the formation of larger CMP aggregates, yielding a more concentrated particle size distribution, compared to the unheated-CMP. Among the heat-treated samples, a significant increase in the average particle size of CMP aggregates was observed as the temperature elevated from 65 °C to 95 °C, transitioning from 77.33 nm to 112.70 nm. Correspondingly, the PDI raised from 0.25 to 0.41. Conversely, prolonging the duration of heating from 5 to 30 min led to an increase in average size. Notably, the PDI decreased with heating durations extended from 5 to 10 min, with no significant differences observed between 10 and 25 min. However, prolonged heating durations exceeding 25 min led to the formation of larger and more irregular aggregates. These observations suggested that prolonged heating durations induced aggregation, resulting in the formation of aggregates with non-uniform sizes.

Fig. 1.

The particle size and PDI of samples at different temperatures (a) and duration (b), respectively; the particle ζ-potential of samples at different temperatures (c) and duration (d), respectively; the small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) graphs of samples at different temperatures (e) and duration (f); the transmission electron microscopy of samples at different temperatures and duration (g), where the length of the yellow lines represents 200 nm. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

It is worth noting that the trends of particle size and ζ-potential are similar. The ζ-potential is related to the surface charge state of the protein, reflecting many physical and chemical properties at the interface. Importantly, a high absolute value of the ζ-potential contributes to greater stability of the suspension (Předota, Machesky, & Wesolowski, 2016). The absolute value of the ζ-potential increases as the temperature rises. There is no significant change in the absolute ζ-potential value when the temperature exceeds 75 °C. At 95 °C, the absolute potential value increased from 17.16 mV to 28.28 mV. This is due to the relaxation of the CMP structure during the heat treatment process, which exposes charged amino acids such as aspartic acid and glutamic acid to the aqueous environment, leading to an increase in the absolute ζ-potential value of the CMP. At 95 °C, there was no significant difference in ζ-potential after heating for >10 min (Fig. 1c and d). However, the increase in electrostatic repulsion was not sufficient to suppress the formation of high molecular weight aggregates, resulting in precipitation.

3.1.2. Analysis of SAXS data

SAXS is a widely used technique for studying the submicroscopic structure of systems (Chen et al., 2023). As shown in the Fig. 1e and f, when the heating temperature is 65 °C, the scattering pattern is consistent with the original sample. There is a “bump” in the range of 0.008 A−1 to 0.05 A−1, indicating that CMP and CMP-65 °C may form a multi-dispersed core-shell structure (Hu et al., 2019). However, the larger aggregates formed during heating result in slightly lower scattering intensity of CMP-65 °C compared to CMP. When the heating temperature is between 75 °C and 95 °C, the scattering pattern is similar. It is noteworthy that the “bump” disappears and forms a shoulder, indicating the formation of larger aggregates with smooth surfaces. High scattering intensity appears at q < 0.008 A−1, which might be attributed to the reorganization of CMP structure and the detachment of non-aggregated small molecule proteins during the heating process (Yang, Gu, Banjar, Li, & Hemar, 2018). With increasing duration, the scattering intensity slightly decreases, suggesting a positive correlation between aggregate size and temperature as well as duration.

3.1.3. Transmission electron microscopy

TEM can visually visualize the shape and size of the samples. Fig. 1g shows the CMP images captured by TEM. It is evident that as the temperature increases, the particle size of the CMP increases and transitions from nearly circular to irregular, forming larger aggregates after 75 °C. With heating at 95 °C for >10 min, the aggregation of CMP becomes even more pronounced. The TEM results also confirmed with the particle size of CMP and the scattered light intensity of SAXS.

3.1.4. The Endogenous fluorescence emission spectra

Endogenous fluorescence spectroscopy is a technique that indirectly reflects changes in the position of tryptophan residues and provides insights into the structural alterations of proteins through the measurement of tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra (Zhao et al., 2022). As temperature and duration increases, there is a decrease in fluorescence intensity (Fig. 2a and b). In theory, the fluorescence of Try can be quenched by the transfer of protons from charged amino groups. Meanwhile, λmax value shows a red-shift from 338.2 nm to 340.8 nm (Fig. 2a), indicating a relaxation of the CMP structure. This suggests an increase in the polarity of the hydrophobic amino acid microenvironment within the protein, exposing it to the aqueous environment. During the heating process from 0 to 5 min, there is no red shift observed in λmax, but there is a decrease in protein fluorescence intensity. However, when the heating duration exceeds 5 min, λmax shifts to 340.8 nm, while the fluorescence intensity remains relatively unchanged (Fig. 2b). This indicates that after heating at 95 °C for 10 min, there is only a slight alteration in the tertiary structure. Increasing the temperature and duration of heating facilitates changes in the CMP tertiary structure, exposing hydrophobic moieties and enhancing its hydrophobicity.

Fig. 2.

The fluorescence spectra of samples at different temperatures (a) and duration (b); the infrared spectra of samples at different temperatures (c) and duration (d); the variations in the content of free thiol and disulfide bonds in the samples at different temperatures (e) and duration (f); the surface hydrophobicity index of samples at different temperatures (g) and duration (h).

3.1.5. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

FTIR spectroscopy, based on the molecular vibration absorption characteristics, is one of the important methods for detecting protein conformation and structure. As depicted in Fig. 2c and d, the absorption peak at 3600–3200 cm−1 corresponds to the -OH group and becomes broader with increasing temperature, indicating intermolecular -OH coupling and the strong role of hydrogen bonding in CMP aggregation. The peak at 2964 cm−1 experiences variation across all samples and can be attributed to the anti-symmetric stretching of -CH3 (Chen et al., 2023). The increase in the peak at 2925.8 cm−1 is ascribed to the presence of negatively charged free carboxyl groups (Shaddel et al., 2018). The peaks at 1654 cm−1 and 1543 cm−1 are associated with the stretching of C O and the symmetric stretching of N-C=O, respectively (Jia, Cao, Ji, Zhang, & Muhoza, 2020). The spectral region of 1700–1600 cm−1, known as the amide I band, offers a wealth of information regarding protein secondary structures. Analysis of this region using Peakfit v 4.12 revealed the content of different secondary structures in CMP, as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composition of the secondary structure.

| Samples | Composition of the secondary structure (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-helix | β-sheet | β-turn | Random coil | |

| Unheated | 14.4aA | 29.3bF | 23.8aA | 32.6cD |

| 65 °C-30 min | 10.1b | 34.7a | 21.9c | 33.3b |

| 75 °C-30 min | 8.6c | 34.1a | 24.1a | 33.2b |

| 85 °C-30 min | 8.9c | 34.4ab | 21.5c | 35.2a |

| 95 °C-30 min | 7.6dD | 34.1aD | 23.0bBC | 35.3aA |

| 95 °C-25 min | 9.3B | 33.1E | 23.3AB | 34.3B |

| 95 °C-`20 min | 6.9E | 35.1C | 22.9BC | 35.1A |

| 95 °C-15 min | 8.2C | 36.7B | 22.7BC | 32.4D |

| 95 °C-10 min | 9.7B | 39.0 A | 20.9D | 30.4E |

| 95 °C-5 min | 9.9B | 33.9D | 22.5C | 33.2C |

| Pooled standard deviation | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

Note: Different English letters indicate significant differences among samples, with lowercase letters representing differences among samples at different temperatures, and uppercase letters representing differences among samples at different time points (p < 0.05).

CMP exhibits a lower α-helix (14.4%) and a higher random coil (32.6%), which also implies its potential emulsifying properties. This provides further evidence for the stability of CMP Pickering emulsions discussed later. The content of β-sheet and β-turn are 29.3% and 23.8%, respectively. As temperature and duration increase, the α-helix content decreases to 7.6%, while the random coil content continues to rise to 35.3%. There are minimal changes in the percentages of β-sheet and β-turn. The unfolding of α-helix and the increase in random coil content endow CMP with flexibility (Tan et al., 2021), making it more capable of forming interfacial films at oil-water interfaces.

3.1.6. Sulfhydryl content

The changes in thiol groups and disulfide bonds during the heating process are illustrated in Fig. 2e and f. The content of disulfide bonds increases with rising temperature but becomes insignificant when the temperature exceeds 85 °C. Concurrently, the content of free sulfhydryl group decreased. Heat treatment results in the unfolding of the protein structure, leading to the exposure of -SH groups, which in turn form disulfide bonds and contribute to the cross-linking reactions between free sulfhydryl groups. These processes are critical for the formation of stable aggregates (Li et al., 2020). The increase in free sulfhydryl content from 15 to 30 min may indicate further protein unfolding without the formation of additional disulfide bonds.

3.1.7. Surface hydrophobicity index

The hydrophobicity is closely associated with the emulsifying activity of proteins. As the temperature rises, hydrophobic groups are exposed, causing an increase in the hydrophobicity of CMP surfaces, particularly rapidly beyond 75 °C (Fig. 2g). However, at 95 °C, there is no significant change in heating duration exceeding 5 min (p > 0.05), with maximum values reached at 15 min. Nevertheless, denatured proteins are thermodynamically unstable, and continuous heating leads to the formation of aggregates through forces such as hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interaction, resulting in a decline in surface hydrophobicity after 15 min (Fig. 2h) (Guo et al., 2021). This result is consistent with the observed trends in the changes of the higher-order tertiary and secondary structures mentioned above.

3.1.8. Contact angle

The contact angle is a crucial indicator for measuring the wetting properties of a substance, and it offers a macroscopic view of the protein's hydrophilic/hydrophobic nature. A contact angle smaller than 90° signifies hydrophilicity, while a value >90° indicates hydrophobicity. Only when the angle approaches 90° can it stabilize at the oil-water interface better (Cui et al., 2023). The results demonstrate that the contact angles of CMP are all <90°, indicating its hydrophilic nature. Heating at 65 °C did not significantly alter the hydrophilicity of CMP. When the temperature exceeded 75 °C, the contact angle increased from 57.7° to 81.9°, 84.7°, and 79.8° (Fig. 3d). Upon heating at 95 °C for 5 min, the contact angle rose to 76.5°, reaching a maximum of 80.2° at 15 min, aligning with the surface hydrophobicity index (Fig. 2g and h). The tendency of the contact angle toward 90° provides strong evidence for the subsequent formation of a high internal phase emulsion.

Fig. 3.

The emulsification activity and stability of samples at different temperatures (a) and duration (b); the interface pressure for the unheated and the heated (95 °C for 30 min) samples (c); the contact angle of samples at different temperatures and duration (d).

3.1.9. Interfacial pressure

The dynamic adsorption, penetration, and rearrangement of proteins at the oil-water interface are not only crucial for their emulsifying properties but also vital for the stability of the emulsion (Tang & Shen, 2015). If the adsorption process is diffusion-controlled, the interfacial pressure has a linear relationship with the square root of time. As depicted in Fig. 3c, the unheated-CMP interfacial pressure increases with prolonged time and can be divided into three stages: the first stage represents the diffusion-controlled adsorption process, predominantly involving the diffusion of particles from the aqueous phase to the oil-water interface; the second stage embodies the mesoporous diffusion, indicating the protein's penetration into the interface; the third stage involves microporous diffusion, where the protein undergoes structural rearrangement at the interface, forming a viscoelastic interfacial film. In contrast, the heated-CMP interfacial pressure remains largely unchanged, indicating that its adsorption is not influenced by diffusion and can rapidly stabilize at the oil-water interface. The interfacial pressure of heated-CMP is lower than that of unheated-CMP. This may be due to changes in the conformation of flexible particles at the oil-water interface, which could alter the distribution of proteins at the interface, thereby reducing interfacial pressure. Additionally, heated-CMP has a higher percentage of interface adsorption and is prone to aggregation at the interface, increasing particle interaction and leading to a decrease in interfacial pressure.

3.2. Emulsification and emulsion stability

EAI and ESI are crucial parameters that characterize the emulsifying properties of proteins. EAI indicates the maximum surface area formed per gram of protein, while ESI represents the protein's ability to maintain the emulsion structure against changes. As illustrated in the Fig. 3a and b, with the increase of temperature and duration, EAI and ESI of CMP were significantly improved. At 95 °C for 30 min, CMP demonstrated optimal EAI and ESI. EAI increased from 12.4 m2/g to 22.8 m2/g, a 1.84-fold increase. ESI also increased from 34.48 min to 77.2 min, a 2.24-fold increase. The results indicate that the emulsifying activity and stability of CMP show no significant differences, after heating at 95 °C for 25 min. This is attributed to the enhanced flexibility of the protein structure after heating, which facilitates the reorganization of protein aggregates through hydrogen bonds, disulfide bonds, and hydrophobic interactions, resulting in a higher surface hydrophobicity, as mentioned previously.

The enhancement of emulsification performance will open up new avenues for CMP. Therefore, a CMP preparation method involving heating at 95 °C for 30 min was chosen to investigate the influence of protein concentration and oil-to-protein ratio on the emulsion. Furthermore, the stability of the emulsion was tested at different salt ion strengths and temperatures.

3.3. The influence of different protein concentrations of the Pickering emulsions

3.3.1. Particle size and ζ-potential of the Pickering emulsions

As the concentration of the CMP increases, the particle size of the Pickering emulsion decreases while the ζ-potential increases (Fig. 4a and b), this is consistent with the results of Zhao's study (Zhao, Wu, Xing, Xu, & Zhou, 2019). Generally, smaller particle size indicates higher stability of the Pickering emulsion. A higher absolute value of the ζ-potential promotes a better balance between the Pickering emulsion droplets. At the same concentration, the Pickering emulsion formed by the heated-CMP has a smaller particle size compared to the unheated-CMP. It could be attributed to the heightened adsorption percentage of the heated-CMP, resulting in a greater stabilization of proteins at the oil-water interface. This observation is confirmed by Fig. 4f, where the lower aqueous phase of the heated-CMP Pickering emulsion appears transparent, while the lower phase of the unheated-CMP Pickering emulsion appears turbid with unseparated droplets and unabsorbed protein. As shown in Fig. 4b, with the increase in protein concentration, the ζ-potential of the Pickering emulsion droplets decreases. The ζ-potential of the unheated-CMP Pickering emulsion changes from −55.13 mV to −46.30 mV, while the ζ-potential of the heated-CMP Pickering emulsion changes from −45.77 mV to −40.57 mV. The ζ-potential absolute value exceeding 30 mV is beneficial to enhance the stability of the Pickering emulsion system.

Fig. 4.

The particle size distribution (a) and ζ-potential (b) of Pickering emulsions at different protein concentrations; the storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G′′) of Pickering emulsions at different protein concentrations, both in the unheated-CMP Pickering emulsions and the heated-CMP Pickering emulsions (c); the apparent viscosity of the Pickering emulsions (d); the confocal laser scanning microscopy images of Pickering emulsions at different protein concentrations (e), where the length of the yellow line and white line segment represent 50 μm and 2.5 μm, respectively; the picture of the Pickering emulsion storage process (f); the creaming indices during storage (g). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.3.2. Rheological properties of Pickering emulsions

All samples exhibit a storage modulus (G') higher than the loss modulus (G"). The larger the difference between the storage modulus (G') and the loss modulus (G") with increasing protein concentration, the greater the resistance to shear frequency, as shown in Fig. 4c. Both the unheated-CMP and the heated-CMP Pickering emulsions show the appearance of yield points with changing frequencies, except for Pickering emulsions with heated protein concentrations exceeding 0.5%. The presence of yield points indicates a transition of the Pickering emulsion from gel-like behavior to sol-like behavior (Gao et al., 2023). With increasing protein concentration, the apparent viscosity of the Pickering emulsion also increases. This is attributed to the formation of a three-dimensional network structure by the proteins in the water phase, which contributes to the stability of the Pickering emulsion. All Pickering emulsions demonstrate pseudoplastic fluid behavior, where in viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate (Fig. 4d).

3.3.3. Confocal laser scanning microscopy

Fig. 4e shows confocal laser scanning microscopy images of the Pickering emulsions at different protein concentrations, the particle size trend is consistent with Fig. 4a. Higher potential leads to independent existence of the Pickering emulsion droplets, and the heated protein emulsion exhibits a more uniform particle size distribution.

3.3.4. Creaming index

After 2 weeks of storage at 4 °C, the separation status of the emulsions were recorded (Fig. 4f and g). The height of the Pickering emulsion increased with increasing concentration and reached a stable state after 7 days. No oiling-out was observed even after one month. In other words, the addition of an appropriate amount of protein effectively prevents Pickering emulsion separation.

In summary, increasing the concentration of CMP helps to reduce the particle size of the Pickering emulsion and make it more uniform. It also increases the viscosity, and solid-like behavior of the Pickering emulsion, resulting in improved stability. This is attributed to the increased interfacial protein content and coverage (Table S1).

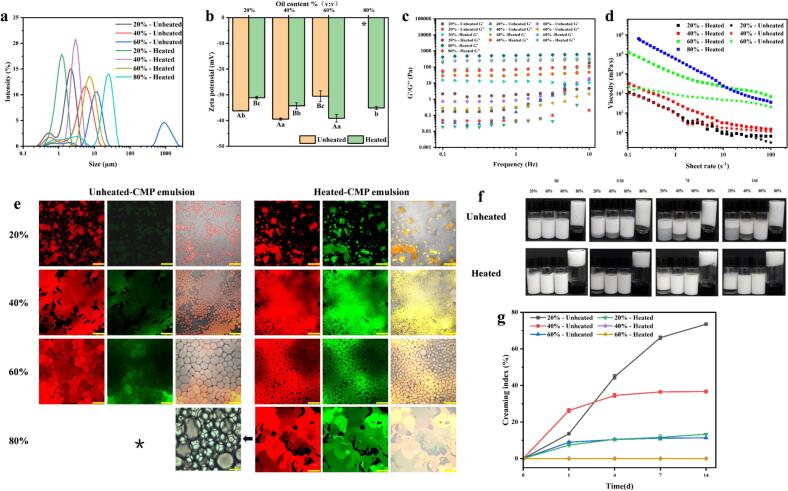

3.4. The influence of different oil phase proportion of Pickering emulsions

3.4.1. Particle size and ζ-potential of the Pickering emulsions

The particle size of the Pickering emulsion significantly increases with the increase in oil phase ratio (Fig. 5a), while the adsorption percentage remains unchanged (Table S1). This results in a decrease in the interfacial protein content, making the concentration of the CMP a limiting factor in reducing the particle size of the Pickering emulsion. The absolute value of the heated-CMP Pickering emulsion's ζ-potential increases from 31.13 mV to 39.13 mV with the increase in the oil phase (Fig. 5b). The decrease in interfacial protein content leads to weakened interactions between interfacial proteins, resulting in an increase in the distance between the tightly packed layer and the dispersed layer, manifested as an increase in the absolute value of the ζ-potential of the droplets. With an increase in oil phase ratio, the heated-CMP is able to stabilize the formation of HIPPE, while unheated-CMP cannot (Fig. 5f). This is attributed to the significant improvement in surface hydrophobicity and contact angle.

Fig. 5.

The particle size distribution (a) and ζ-potential (b) of Pickering emulsions with different oil phases; the G′/G′′ of Pickering emulsions with different oil phases (c), both in the unheated-CMP Pickering emulsions and the heated-CMP Pickering emulsions; the apparent viscosity of the Pickering emulsions with different oil phases (d); the confocal laser scanning microscopy images of Pickering emulsions with different oil phases (e), while the length of the yellow line segment marks 50 μm; the picture of the Pickering emulsion storage process (f); the creaming indices during storage (g). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.4.2. Rheological properties of Pickering emulsions

In the frequency range of 0.1–10 Hz, the stabilized Pickering emulsions formed by the heated-CMP exhibit a higher storage modulus (G') than the loss modulus (G"), demonstrating gel-like behavior characteristic of an elastic solid. The gel elasticity increases with the increase in oil phase, while the unheated-CMP Pickering emulsions show a yield point and frequency-dependent G' and G" (Fig. 5c). The apparent viscosity increases with the increase in oil phase, with the Pickering emulsions formed by the heated-CMP showing higher viscosity compared to the unheated-CMP. The viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate, demonstrating shear-thinning behavior (Fig. 5d).

3.4.3. Confocal laser scanning microscopy

Fig. 5e shows images of the Pickering emulsion captured under confocal laser scanning microscopy. It is noticeable that the extent of coalescence of the Pickering emulsion droplets increases with the increase in oil phase ratio. The three-dimensional network structure formed by the coalescence of the droplets provides a reasonable explanation for the absence of phase separation in the Pickering emulsion. Simultaneously, this also contributes to the increase in the apparent viscosity of the Pickering emulsion. When the oil phase exceeds 40%, the unheated-CMP Pickering emulsion undergoes coalescence, which becomes more significant at 60%. This is due to the lower interfacial protein content, which is not sufficient to form a robust interfacial membrane, under external forces, the Pickering emulsion tends to stabilize by forming larger droplets to increase the coverage of interfacial proteins. On the other hand, the heated-CMP Pickering emulsion exhibits higher interfacial protein adsorption, and no coalescence occurs even at 60% oil phase ratio. However, at 80%, the HIPPE formed by 1% Heated protein undergoes liquefaction under external pressure, resulting in shape change. Therefore, it is necessary to increase the concentration of the heated protein or manufacture CMP particles with higher performance to form a stable and high-performance HIPPE. The attached Figure shows images of the HIPPE under an optical microscope.

3.4.4. Creaming index

The creaming index (CI) decreases with the increase in oil phase (Fig. 5g). This is possibly due to the higher content of Pickering emulsion formed with a higher oil phase ratio. Furthermore, the increase in emulsion viscosity, as the oil phase's viscosity is higher than water, inhibits phase separation (Gao et al., 2023). As shown in Fig. 5f, beyond a threshold of 40% in the oil phase ratio, the Pickering emulsion remains free from any occurrence of separation.

3.5. Effect of different salt ion concentrations on Pickering emulsions

3.5.1. Particle size and ζ-potential of the Pickering emulsions

The presence of salt ions can reduce the surface charge of proteins, leading to the aggregation of protein particles (Gu, Li, Shi, & Xiao, 2022). Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the influence of different salt ion concentrations on Pickering emulsions. Fig. 6 illustrates the impact of different NaCl concentrations on the Pickering emulsion. The increase in NaCl concentration did not affect the particle size distribution of the unheated-CMP Pickering emulsion but reduced the absolute value of the Pickering emulsion's ζ-potential (Fig. 6a and b), likely due to electrostatic screening. Simultaneously, an increase in NaCl concentration accelerates the phase separation of the Pickering emulsion. This is because the increase in NaCl concentration reduces the percentage of protein adsorption at the interface, leading to a decrease in the number of interfacial proteins (Table S2). As a result, the interaction between oil droplets weakens,this is consistent with the findings of Zhu, Chen, McClements, Zou, and Liu (2018) and Gu et al. (2022). Unheated-CMP may experience steric hindrance at the oil-water interface, and increasing salt ion concentration reduces protein-protein interactions, causing some proteins to detach from the interface. The clarification of the underlying aqueous phase may be attributed to the salting out effect. However, it has been found that the final CI is not significantly affected due to the sufficient presence of interfacial proteins, which helps maintain the stability of the Pickering emulsion droplets (Fig. 6e and f). The increase in NaCl concentration did not have a significant effect on the particle size, potential, and CI of the heated-CMP Pickering emulsion.

Fig. 6.

The particle size (a) and ζ-potential (b) of Pickering emulsions at different salt ion concentrations; the G′/G′′ of the unheated-CMP Pickering emulsions and the heated-CMP Pickering emulsions at different salt ion concentrations (c); the apparent viscosity of the Pickering emulsions at different salt ion concentrations (d); the picture of the Pickering emulsion storage process (e); the creaming indices of the unheated-CMP Pickering emulsions and the heated-CMP Pickering emulsions at different salt ion concentrations (f).

3.5.2. Rheological properties of Pickering emulsions

At NaCl concentrations of 0–600 mM, there was a slight increase in the apparent viscosity and G′/G′′. At 800 mM, there was a decrease in both apparent viscosity and G′/G′′ (Fig. 6c and d). This could be attributed to NaCl concentrations of 0–600 mM promoting droplet aggregation, enhancing the strength of the network structure, which led to an increase in apparent viscosity and G′/G′′, as reported previously (Sun et al., 2022). However, high NaCl concentrations exhibited a disruptive trend, causing a decrease in apparent viscosity and G′/G′′. It is essential to note that the interfacial area per protein molecule and the interfacial protein coverage were not affected by NaCl concentration, indicating the crucial role of Pickering emulsion stability.

In summary, the critical factor for stabilizing Pickering emulsion droplets is the content of interfacial proteins. A high protein content forms a dense interfacial membrane on the surface of oil droplets, which can resist adverse conditions. Unheated-CMP and heated-CMP Pickering emulsions, both prepared with 1% protein concentration and 20% MCT, demonstrated strong resistance to salt ions.

3.6. Different temperature treatment effect on Pickering emulsions

3.6.1. Particle size and ζ-potential of the Pickering emulsions

Thermal treatment is a common processing method in the food industry, and the exploration of Pickering emulsion stability at high temperatures is particularly important. The Pickering emulsions were heated at 40 °C, 60 °C, 80 °C, and 100 °C for 30 min, and then cooled to 25 °C for characterization. As depicted in Fig. 7a and b, the unheated-CMP Pickering emulsion showed no change in particle size after treatment, while the absolute value of ζ-potential decreased at 25–80 °C and increased at 100 °C. It is possible that after heat treatment, the proteins undergo denaturation and aggregation, leading to the coverage of polar sites by the aggregates, resulting in a decrease in the absolute value of the ζ-potential. The increase in temperature to 100 °C decreases the interfacial protein content, leading to a decrease in the protein-protein interaction forces and an increase in the electrical double layer distance, thereby resulting in an increase in the absolute value of the ζ-potential. Thermal treatment had no significant effect on the particle size and creaming index of the heated-CMP Pickering emulsion, Meanwhile, the absolute value of the potential in the heated-CMP Pickering emulsion continues to increase, possibly due to the thermal treatment enhancing the protein-protein interactions at the interface, leading to their reorganization at the interface.

Fig. 7.

The particle size (a) and ζ-potential (b) of Pickering emulsions at different temperatures; the G′/G′′ of the unheated-CMP Pickering emulsions and heated-CMP Pickering emulsions at different temperatures (c); the apparent viscosity of the Pickering emulsions at different temperatures (d); the picture of the Pickering emulsion storage process (e); the creaming indices of the unheated-CMP Pickering emulsions and the heated-CMP Pickering emulsions at different temperatures (g).

3.6.2. Rheological properties of Pickering emulsions

Heating also delayed the Pickering emulsion stratification (Fig. 7e and f), reduced the creaming index, and exhibited a decreasing trend in apparent viscosity. On one hand, the protein in the aqueous phase expanded during heating, forming a network structure that delayed Pickering emulsion stratification. On the other hand, from the interface perspective, heating increased the interfacial protein content (Table S2), leading to an increase in G′/G′′ at 25–80 °C due to the interaction of interfacial proteins. However, the decrease in G′/G′′ at 100 °C was attributed to the excessive temperature causing desorption of interfacial proteins (Liang et al., 2017).

The apparent viscosity and the G'/G" of the thermally treated the heated-CMP Pickering emulsion were both increased, particularly at 100 °C (Fig. 7c). The interfacial protein content remained unchanged with variations in temperature (Table S2), exemplifying its exceptional heat resistance.

Overall, both types of Pickering emulsions exhibit good thermal stability, but the heated-CMP Pickering emulsion is more stable than the unheated-CMP Pickering emulsion, with improved performance after heating. This phenomenon has been reported previously as well (Dai et al., 2023).

4. Conclusion

The research findings indicate that heating CMP at 95 °C for 30 min effectively improves its emulsifying performance. This improvement is attributed to the formation of aggregates by CMP under hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and disulfide bond interactions, leading to a remarkable increase in surface hydrophobicity. These aggregates can rapidly adsorb to the oil-water interface, thereby increasing the interfacial protein adsorption percentage. The interfacial protein content has a strong correlation with the properties of the Pickering emulsion. A higher interfacial protein content results in smaller, more uniform Pickering emulsion droplet size and stronger rheological properties. However, the relationship between interfacial protein content and rheological properties is influenced by the oil phase ratio, salt ion concentration, and temperature. For the unheated-CMP Pickering emulsion, the interfacial protein content decreases with increasing NaCl concentration, while heating at a lower temperature could promote protein adsorption, but could not achieve the effect of protein heat treatment. On the other hand, the heated-CMP Pickering emulsion exhibits interfacial protein content that is not influenced by NaCl concentration or heating temperature, demonstrating greater stability. In summary, environmental factors impact Pickering emulsions by influencing the content of interfacial proteins, and heated CMP can resist adverse external conditions to maintain the thermal stability of the Pickering emulsion. The heated-CMP demonstrates excellent Pickering emulsion properties, broadening its potential applications as an emulsifier in coconut milk or as a delivery system for transporting bioactive substances.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yujie Guo: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Tian Tian: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Chili Zeng: Software, Investigation. Hong Wang: Writing – review & editing. Tao Yang: Investigation. Weibiao Zhou: Supervision. Xiaonan Sui: Methodology. Liang Chen: Visualization. Zhaoxian Huang: Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Lianzhou Jiang: Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 32360589 and 32230082); International Science & Technology Cooperation Program of Hainan Province (No: GHYF2023006); Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 322QN245); Research Project of the Collaborative Innovation Center of Hainan University (No:XTCX2022NYC20), and Hainan University Research Start-up Fund (No: KYQD(ZR)-22011); The China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No.2023 M732131); Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund (ZDYF2024XDNY170).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101442.

Contributor Information

Zhaoxian Huang, Email: huangzhaoxian@hainanu.edu.cn.

Lianzhou Jiang, Email: jlzname@163.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The interfacial adsorption percentage and the content of interfacial proteins.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Chao D., Aluko R.E. Modification of the structural, emulsifying, and foaming properties of an isolated pea protein by thermal pretreatment. CyTA Journal of Food. 2018;16(1):357–366. doi: 10.1080/19476337.2017.1406536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Song Y., Wang Z., Ji H., Du Z., Ma Q.…Sun Y. Developments in small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) for characterizing the structure of surfactant-macromolecule interactions and their complex. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2023;251 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.126288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Chen Y., Fang Y., Pei Z., Zhang W. Coconut milk treated by atmospheric cold plasma: Effect on quality and stability. Food Chemistry. 2024;430 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.137045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Chen Y., Jiang L., Huang Z., Zhang W., Yun Y. Improvement of emulsifying stability of coconut globulin by noncovalent interactions with coffee polyphenols. Food Chemistry: X. 2023;20 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2023.100954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Chen Y., Jiang L., Yang Z., Fang Y., Zhang W. Shear emulsification condition strategy impact high internal phase Pickering emulsions stabilized by coconut globulin-tannic acid: Structure of protein at the oil-water interface. LWT- Food Science and Technology. 2023;187 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2023.115283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui S., McClements D.J., Shi J., Xu X., Ning F., Liu C.…Dai L. Fabrication and characterization of low-fat Pickering emulsion gels stabilized by zein/phytic acid complex nanoparticles. Food Chemistry. 2023;402 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H., Chen H., Fu Y., Wang H., Zhang Y. Myofibrillar protein microgels stabilized high internal phase Pickering emulsions with heat-promoted stability. Food Hydrocolloids. 2023;138 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.108474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Lin D., Peng H., Zhang R., Zhang B., Yang X. Low oil Pickering emulsion gels stabilized by bacterial cellulose nanofiber/soybean protein isolate: An excellent fat replacer for ice cream. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2023;247 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graca C., Raymundo A., de Sousa I. Rheology changes in oil-in-water emulsions stabilized by a complex system of animal and vegetable proteins induced by thermal processing. LWT- Food Science and Technology. 2016;74:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.07.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gu R., Li C., Shi X., Xiao H. Naturally occurring protein/polysaccharide hybrid nanoparticles for stabilizing oil-in-water Pickering emulsions and the formation mechanism. Food Chemistry. 2022;395 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z., Huang Z., Guo Y., Li B., Yu W., Zhou L.…Wang Z. Effects of high-pressure homogenization on structural and emulsifying properties of thermally soluble aggregated kidney bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) proteins. Food Hydrocolloids. 2021;119 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.106835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Zhang X., Chen D., Li N., Hemar Y., Yu B.…Sun Y. How much can we trust polysorbates as food protein stabilizers - the case of bovine casein. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;96:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.05.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia C., Cao D., Ji S., Zhang X., Muhoza B. Tannic acid-assisted cross-linked nanoparticles as a delivery system of eugenol: The characterization, thermal degradation and antioxidant properties. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;104 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.105717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ko E.B., Kim J.-Y. Application of starch nanoparticles as a stabilizer for Pickering emulsions: Effect of environmental factors and approach for enhancing its storage stability. Food Hydrocolloids. 2021;120 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.106984. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Tian Y., Liu C., Dou Z., Diao J. Effects of heat treatment on the structural and functional properties of Phaseolus vulgaris L. Protein. Foods. 2023;12(15):2869. doi: 10.3390/foods12152869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Chen L., Hua Y., Chen Y., Kong X., Zhang C. Effect of preheating-induced denaturation during protein production on the structure and gelling properties of soybean proteins. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;105 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.105846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y., Gillies G., Matia-Merino L., Ye A., Patel H., Golding M. Structure and stability of sodium-caseinate-stabilized oil-in-water emulsions as influenced by heat treatment. Food Hydrocolloids. 2017;66:307–317. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.11.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Zeng J., Sun B., Zhang N., He Y., Shi Y., Zhu X. Ultrasound-assisted mild heating treatment improves the emulsifying properties of 11S globulins. MOLECULES. 2020;25(4):875. doi: 10.3390/molecules25040875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phosanam A., Moreira J., Adhikari B., Adhikari A., Losso J.N. Stabilization of ginger essential oil Pickering emulsions by pineapple cellulose nanocrystals. Current Research in Food Science. 2023;7 doi: 10.1016/j.crfs.2023.100575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Předota M., Machesky M.L., Wesolowski D.J. Molecular origins of the zeta potential. Langmuir. 2016;32(40):10189–10198. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b02493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodsamran P., Sothornvit R. Physicochemical and functional properties of protein concentrate from by-product of coconut processing. Food Chemistry. 2018;241:364–371. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.08.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaddel R., Hesari J., Azadmard-Damirchi S., Hamishehkar H., Fathi-Achachlouei B., Huang Q. Use of gelatin and gum Arabic for encapsulation of black raspberry anthocyanins by complex coacervation. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2018;107:1800–1810. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shand P.J., Ya H., Pietrasik Z., Wanasundara P.K.J.P.D. Physicochemical and textural properties of heat-induced pea protein isolate gels. Food Chemistry. 2007;102(4):1119–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.06.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen P., Wu J., Zhao M., Zhou F. Does particle size matter for soy protein nanoparticles in the fabrication and lipolysis of pickering-like emulsions? Food Hydrocolloids. 2024;153 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2024.110005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Chen H., Chen W., Zhong Q., Shen Y., Zhang M. Effect of ultrasound on pH-shift to improve thermal stability of coconut milk by modifying physicochemical properties of coconut milk protein. LWT- Food Science and Technology. 2022;167 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.113861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M., Xu J., Gao H., Yu Z., Liang J., Mu D.…Zheng Z. Effects of combined high hydrostatic pressure and pH-shifting pretreatment on the structure and emulsifying properties of soy protein isolates. Journal of Food Engineering. 2021;306 doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2021.110622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C.-H., Shen L. Dynamic adsorption and dilatational properties of BSA at oil/water interface: Role of conformational flexibility. Food Hydrocolloids. 2015;43:388–399. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2014.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y., Cai J., Wang P., Chen J., Zhou L., Yang Z., Xu X. Exploring the relationship between the interfacial properties and emulsion properties of ultrasound-assisted cross-linked myofibrillar protein. Food Hydrocolloids. 2024;146 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.109287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thaiphanit S., Anprung P. Physicochemical and emulsion properties of edible protein concentrate from coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) processing by-products and the influence of heat treatment. Food Hydrocolloids. 2016;52:756–765. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2015.08.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian T., Liu S., Li L., Wang S., Cheng L., Feng J., Wang Z., Tong X., Wang H., Jiang L. Soy protein fibrils–β-carotene interaction mechanisms: Toward high nutrient plant-based mayonnaise. LWT- Food Science and Technology. 2023;184 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2023.114870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian T., Ren K., Cao X., Peng X., Zheng L., Dai S.…Jiang L. High moisture extrusion of soybean-wheat co-precipitation protein: Mechanism of fibrosis based on different extrusion energy regulation. Food Hydrocolloids. 2023;144 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.108950. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q., Chen Z., Xie X., Zhang Y., Chen J., Weng H., Chen F., Xiao A. A novel Pickering emulsion stabilized solely by hydrophobic agar microgels. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2022;297 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.120035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Gu Q., Banjar W., Li N., Hemar Y. In situ study of skim milk structure changes under high hydrostatic pressure using synchrotron SAXS. Food Hydrocolloids. 2018;77:772–776. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.11.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Liang L., Tian Z., Chen L., Subirade M. Preparation and in vitro evaluation of calcium-induced soy protein isolate nanoparticles and their formation mechanism study. Food Chemistry. 2012;133(2):390–399. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., Wang W., Zhao R., Yan T., Xu W., Xu E., Liu D. The hydrophobic interaction for ellagic acid binding to soybean protein isolate: Multi-spectroscopy and molecular docking analysis. LWT- Food Science and Technology. 2022;170 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.114110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Wu T., Xing T., Xu X.-L., Zhou G. Rheological and physical properties of O/W protein emulsions stabilized by isoelectric solubilization/precipitation isolated protein: The underlying effects of varying protein concentrations. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;95:580–589. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.03.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Niu H., Luo T., Yun Y., Zhang M., Chen W.…Chen W. Effect of glycosylation with sugar beet pectin on the interfacial behaviour and emulsifying ability of coconut protein. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2021;183:1621–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q., Chen W., Wang L., Chen W., Zhang M., Zhong Q.…Chen H. Development of high internal phase emulsions using coconut protein isolates modified by pulsed light: Relationship of interfacial behavior and emulsifying stability. Food Hydrocolloids. 2024;148 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.109495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q., Li Y., Li S., Wang W. Fabrication and characterization of acid soluble collagen stabilized Pickering emulsions. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;106 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.105875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Chen X., McClements D.J., Zou L., Liu W. pH-, ion- and temperature-dependent emulsion gels: Fabricated by addition of whey protein to gliadin-nanoparticle coated lipid droplets. Food Hydrocolloids. 2018;77:870–878. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.11.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The interfacial adsorption percentage and the content of interfacial proteins.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.