Summary

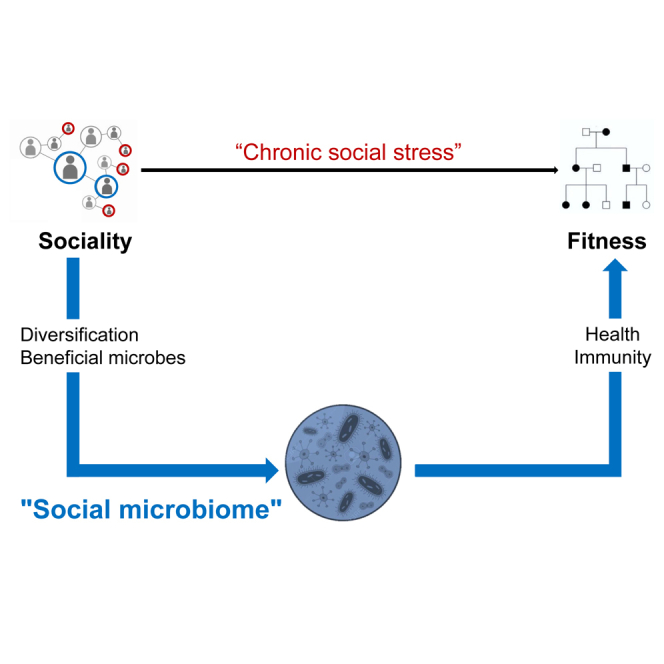

In many social mammals, early social life and social integration in adulthood largely predict individual health, lifespan, and reproductive success. So far, research has mainly focused on chronic stress as the physiological mediator between social environment and fitness. Here, we propose an alternative, non-exclusive mechanism relying on microbially mediated effects: social relationships with conspecifics in early life and adulthood might strongly contribute to diversifying host microbiomes and to the transmission of beneficial microbes. In turn, more diverse and valuable microbiomes would promote pathogen resistance and optimal health and translate into lifelong fitness benefits. This mechanism relies on recent findings showing that microbiomes are largely transmitted via social routes and play a pervasive role in host development, physiology and susceptibility to pathogens. We suggest that the social transmission of microbes could explain the sociality-fitness nexus to a similar or higher extent than chronic social stress and deserves empirical studies in social mammals.

Subject areas: Microbiology, Microbiome, Social sciences

Graphical abstract

Microbiology; Microbiome; Social sciences

The quality of the social environment is one of the strongest predictors of health and longevity in humans,4 a conspicuous relationship also observed in many other social mammals—with effect sizes of strikingly high amplitudes.5 Early-life social adversity, social integration (the number and strength of social bonds), and social status (dominance rank) are the three major aspects of the social environment strongly predicting fitness. In most mammalian orders, individuals that experience adverse social conditions in early life, such as maternal loss, that are poorly social integrated throughout their lifetime, or—to a lesser extent—that acquire low social status, display considerably higher offspring mortality and shorter lifespans than individuals enjoying a rich social life (reviewed in a study by Snyder-Mackler et al.5).

Despite broad theoretical and biomedical interests in understanding this sociality-fitness nexus, researchers have mainly focused on chronic exposure to “social stress” in individuals facing adverse social environments, leading to detrimental neuroendocrine and immune responses.5 Indeed, evidence in laboratory animals indicate that social conditions promoting chronic stress, such as social isolation or the removal of a social companion, predict dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and changes in signaling in the sympathetic nervous system. These changes are accompanied by elevated glucocorticoids (GCs) production6 as well as immune dysregulation and chronic inflammation.7 Furthermore, when experienced over the long-term, chronic stress seems to predispose individuals to a range of illnesses8 and shorten lifespan.9,10 Research on the proximate mechanisms governing phenotypic responses to early life social adversity has likewise been largely limited to studies on GCs, especially because the HPA axis undergoes important programming in early life and appears particularly sensitive to social perturbations during this specific time window.11,12

Chronic social stress, as a mediating physiological pathway in the sociality-fitness nexus, shows, however, some limitations in its explanatory power. From an evolutionary perspective, selection should not maintain a physiological response routinely challenging fitness. Some researchers have argued that animals in their natural environments are unlikely to experience chronic social stress to the degree that it could shorten lifespan.13 In addition, the best evidence for social causation between chronic stress and fitness mostly comes from biomedical research in laboratory animals.5 Comparatively little research has been undertaken in natural populations, and this body of work lead to mixed outcomes with a large majority of non-significant or small effect sizes14,15 (but see a study by Campos et al.10). Exposure to chronic stress is therefore unlikely to explain alone the pervasive sociality-fitness nexus observed in nature.

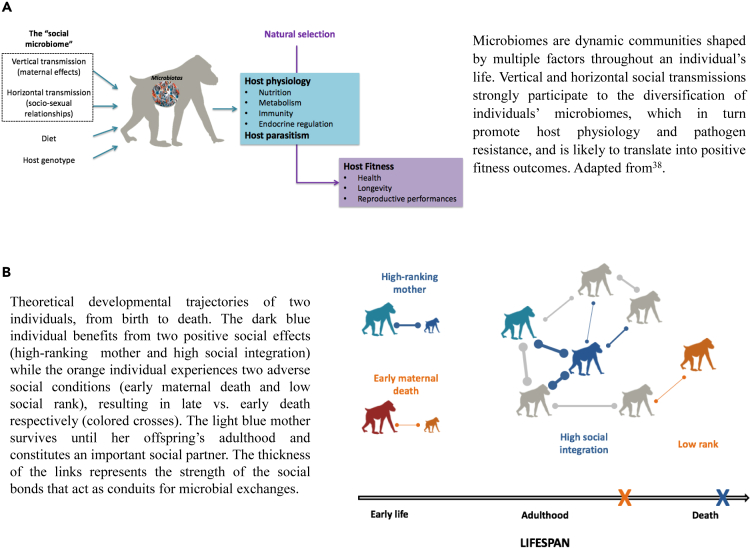

In parallel, the last decade of research has revealed how microbiomes participate in the regulation of virtually all aspects of host biology. Symbiotic microbes contribute to host nutrition and metabolism,16 educate and modulate the host immune system,17,18 protect against pathogen infections,19,20 and are involved in numerous endocrine and central nervous system signaling pathways.21 In addition, some recent findings have highlighted the extent to which microbial diversity and composition are shaped by the social environment (recently reviewed in a study by Sarkar et al.3), along with phylogeny, diet, habitat, host traits and genetics.22,23,24 Here, we refer to the “social microbiome” as the microbial communities that are acquired from the conspecifics via two distinct mechanisms: (1) a vertical transmission of microbial taxa directly from parent to offspring25 and (2) a horizontal “social” transmission mediated by direct physical contacts, shared environmental surfaces, or coprophagy (see glossary for definition)3 (Figure 1A). Thus, hereafter the “social microbiome” refers to any microbes acquired from parent and/or non-parent conspecifics and do not originate from the physical environment (e.g., diet, soil, and water).

Figure 1.

Microbially mediated effects of social environment on fitness in nature

(A) Overall pathways by which the social microbiome might shape host physiology and parasitism, and ultimately fitness, in mammals. (B) Both the early life and adult social environment likely interact to shape to social microbiome.

Combined together, those findings open a new avenue of research on the microbial pathways through which sociality could contribute to health and fitness outcomes in nature. Although poorly considered in naturalistic studies, previous researchers have argued that the social transmission of beneficial gastro-intestinal (GI) symbionts might mitigate the enhanced risk of pathogen infection in social species, constituting an underappreciated benefit of group living.26,27 In a recent review,29 the GI microbiome has been identified as an overlooked pathway by which differences in social, political, and economic factors could contribute to health inequities in humans.28 Here, we build on this previous theoretical framework to propose microbiomes—at multiple body sites—as a missing physiological pathway at the very origin of the relationship between sociality and fitness in wild mammals. We propose that the quality of the social environment, both in early life (via parent-to-infant microbial transmission) and adulthood (via socio-sexual relationships with conspecifics), strongly contributes to the diversification of individual GI, skin, genital, oral, respiratory microbiomes and to the transmission of beneficial microbial taxa among individuals living in groups. In turn, these more diverse and valuable microbiomes are predicted to directly improve host development, nutrition, metabolism, immune and neuroendocrine functions, and above all, pathogen resistance throughout lifespan. The sum of these health-promoting effects could directly explain how social relationships translate into massive positive fitness outcomes in nature. We thus propose an alternative, although non-exclusive, physiological mechanism to the “chronic stress” hypothesis which warrants further empirical investigations. Such microbial diversification and social transmission of health-promoting microbes hold great potential to mediate the relationship between each of the three aspects of the social environment (i.e., early life diversity, social integration, and social status) and individual fitness in social mammals, including in humans, where individuals of different socioeconomic status experience health disparities and differential morbidity.28

Glossary.

Microbiota: the abundant and diverse communities of symbiotic bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses living in and on eukaryotic hosts.

Beneficial microbe: microbe of functional significance that positively impacts host fitness. This includes any microbe that provides a specific nutritional, physiological, metabolic or immune advantage to its host (e.g., utilization of a new dietary item or enhanced resistance against a specific pathogen).

Vertical transmission: transfer of microbe(s) directly from parents to offspring.1 As per a study by Robinson et al.,2 it includes the microbes passed via the egg or in the womb (the strictest definition of vertical transmission), but also those transmitted during or shortly after birth (e.g., from the birth canal and inoculated during breastfeeding).

Horizontal transmission: transfer of microbes via the social environment (i.e., social partners) and the physical environment (i.e., food, water, or soil).1 For clarity, in this perspective we use “horizontal social transmission” to refer to microbes acquired from any conspecifics. Horizontal social transmission can occur via direct physical contacts (e.g., grooming, licking, body contacts, copulations, nest-sharing), shared surfaces (microbes originating from non-contact social behaviors, such as contact with fecal material of conspecifics when foraging) or coprophagy.3 We use “horizontal environmental transmission” otherwise.

Social microbiome: the community of microbes that are acquired at multiple body sites by hosts through their social interactions.3 In this perspective, we use “social microbiome” to refer to both vertical transmission and horizontal social transmission.

Microbiomes impact a wide range of host phenotypes

In mammals, microorganisms start colonizing the host immediately during and after birth and assemble into ecological communities that quickly change and evolve until reaching a stable, but nonetheless dynamic, microbial composition after weaning.25,29 The trajectory of microbial maturation in early life30 and the microbiome diversity and composition during adulthood31 are both highly variable between individuals. Such inter-individual differences in microbial composition influence a variety of host phenotypes.32

The GI microbiome, reaching particularly large microbial densities in the lower intestinal tract, has been the most studied in this respect so far. Intestinal microbes metabolize otherwise inaccessible dietary substrates and produce short-chain fatty acids that are used as an additional source of energy for the host,33 supply essential vitamins, detoxify plant secondary compounds,34 and participate to important digestive processes such as insulin secretion, maintenance of glucose homeostasis, and lipid absorption.35 They further program several aspects of host energy metabolism, such as the regulation of fat storage.36 In wild mammals, adaptive shifts in GI microbial composition with environmental variation is increasingly recognized as an important physiological mechanism through which animals adapt to seasonal changes in diet and maintain their energy balance during challenging periods.37 This dietary and metabolic flexibility provided by GI microbes influence host phenotypic plasticity and life history traits38,39 and likely participate to host local adaptation.40

In addition, mounting evidence suggests that the GI microbiome affects host resistance and tolerance to numerous pathogenic bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites.19,20,41 The GI tract is a mucosal surface constantly exposed to the external environment and, as such, has developed elaborated innate and adaptive immune responses to prevent pathogen invasion. GI microbes contribute directly to pathogen resistance by (1) outcompeting pathogens for nutrients and space,41 (2) producing antimicrobial and antiviral peptides inhibiting pathogenic growth,42 and (3) stimulating mucus production and ensuring the integrity of the intestinal barrier.43 Experiments on laboratory animals devoid of GI microbiota (“germ-free”) have clearly demonstrated the critical role of the GI microbiome in pathogen resistance. Germ-free or antibiotic-treated mice, for instance, show extremely poor immune resistance and higher mortality when infected by a variety of enteric bacteria (e.g., Shigella flexneri, Listeria monocytogenes, and Salmonella enterica)44 or virus (e.g., influenza A virus).45 GI microbes also participate indirectly to pathogen resistance by engaging in a crosstalk with the host immune system upon pathogen detection. In particular, the GI microbiome trains the host immune system in early life46 and modulates the host immune response later in life by directing the differentiation of the pro- and anti-inflammatory responses following infection.18,42 During helminth and protozoa infections, for example, the GI microbiome decreases the pro-inflammatory host immune response, which in turn promotes host tolerance to parasites.47 Symbiotic microbes thus participate to the equilibrium between inflammation and homeostasis in the gut.18

The functions of other microbial communities have been far less studied but emerging evidence also points to their important role in modulating host immunity. Microbes from the upper respiratory tract shape host susceptibility to several respiratory viral infections.48 For example, Staphylococcus aureus, a normal inhabitant of the respiratory mucosa, protects against influenza-mediated lethal inflammation in wild-type mice compared to germ-free mice.49 The skin microbiome has been associated to infection susceptibility by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans causing the white-nose syndrome in North American hibernating bats.50 Resistant individuals harbored a more diverse and abundant host-associated bacterial and fungal community on the skin compared to susceptible bats, and some specific strains were directly found to inhibit the growth of the pathogenic fungus in vitro. In humans, the female genital microbiome is commonly dominated by the genus Lactobacillus that secrete lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide that create an important barrier against sexually transmitted bacterial (e.g., Chlamydia trachomatis and Gardnerella vaginalis) and viral (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]-1, human herpes simplex virus 2) infections, respectively.51 Some Lactobacillus strains seem to be more protective than others and their carriers display a lower susceptibility of acquiring sexually transmitted diseases.51

Overall, pathogen protection conferred by host-associated microbiomes has been proposed as the main evolutionary advantage for the host to tolerate such dense microbial communities.41 Research in this field now focus on how these diverse symbiotic microbial communities colonizing multiple body sites (GI, oral, nasal, skin, and genital) form an interconnected signaling network altogether shaping host pathogen resistance and health. Recent studies of the complex interplay of the gut-skin-brain axis have highlighted, for instance, how GI microbiome dysbiosis can trigger skin disorders and how, in turn, skin conditions impact gut health in humans.52

Diversified and stable microbiomes are highly beneficial

In general, more diverse (i.e., higher taxonomic richness) microbial communities are associated with better metabolism functioning,53,54 better pathogen resistance41 and optimal health status55 for the host. More diverse microbial compositions are thought to use more completely the nutrients and space available at the mucosal surfaces and give fewer opportunities for pathogens to invade.41,56 Highly diversified GI microbiome, and in particular an increase in the prevalence of rare taxa at the expense of core taxa during old ages, has been related to pattern of healthy aging and longevity in humans, for instance.57 Microbial diversity also increases resilience to community perturbations and promotes microbial stability (i.e., the capacity of the community to retain its similarity in composition in response to disturbances) by creating functional redundancy between microbes and preserving functional capacity in hosts in case of microbial lineages extinctions.58,59 Although microbial diversity and composition are highly variable between individuals,31 the extent of intra-individual longitudinal variation depends on the body site,60 but even the skin microbiome constantly exposed to the external environment seem to be largely stable over time.61,62

By contrast, less diverse and more unstable microbial communities generally increase host susceptibility to bacterial and viral infections and are often associated with poor health outcomes.18,55 In humans, depletion or perturbations in microbial communities—due to e.g., sanitation, Western diets, and antibiotics—have been linked to numerous metabolic and immune disorders including obesity, type 1 diabetes, asthma, atopy, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and cardiovascular diseases.55 Mechanisms to maintain microbial diversity and stability are thus likely to be under strong directional selection in nature.

Despite an overall positive impact of high microbial diversity, there are exceptions to this rule. For instance, vaginal microbiomes typically display low diversity in humans and a more diverse community may be indicative of dysbiosis.63 Similarly, infants who are exclusively breastfed typically have a low GI microbial diversity, containing few highly specialized milk-degrader microbes, while formula-fed infants harbor more diverse and mature GI microbiomes that often contain potentially pathogenic microbes.64,65

Social contacts promote microbiomes’ diversity and stability

Meanwhile, a growing literature shows that characteristics of the social environment, in particular how individuals are organized in social networks, act as conduits for microbial exchanges within a host population. Vertical microbial transmission from mother to offspring during and shortly after birth is believed to seed and influence both the diversity and composition of the offspring’s microbiome,66,67 which then continues to be shaped by social contacts with conspecifics later in life through horizontal social transmission.3,68

Mother-to-infant vertical transmission

Mothers are an important reservoir of microbes for their offspring in early life.66,67 Maternal vertical transmission is thought to be particularly salient in mammals due to viviparity and prolonged periods of lactation.22 During parturition, infants are initially inoculated by their mothers’ vaginal, fecal, and skin microbiomes.30,66 Following birth, microbial transmission from the mother continues with the ingestion of milk microbes during nursing and the acquisition of GI microbes mediated by body contacts.69,70 Such vertical transmission is believed to promote faithful non-genetic inheritance of maternal microbial phenotype and is increasingly recognized as an important evolutionary force driving deterministic microbial assembly in mammals22,67 as well as codiversification between host and microbial genomes within and between populations in humans.71 Increasing evidence shows that microbially mediated maternal effects can further persist post-weaning through physical contacts, especially in species where mother-offspring dyads reside in the same social group (such as in female-philopatric species) and display preferential social bonds.22 However, in such case, post-weaning maternal transmission is considered as horizontal social transmission, rather than vertical transmission, both in its mechanism and evolutionary significance.

Horizontal social transmission from conspecifics

During adulthood, microbiomes are also largely transmitted via social and sexual contacts between conspecifics, either by direct physical contacts (e.g., grooming, licking, and copulations), shared surfaces, or coprophagy.3,72 This literature—though highly biased toward the GI microbiome—indicates that individuals living in the same social group exhibit higher similarity in their microbial communities.3 Furthermore, individuals with larger social networks, or those benefiting from a rich social environment, harbor, on average, more diverse microbiomes than those that are poorly socially integrated.73 At the dyadic level, pairs of individuals that engage in more frequent social68,74,75 and sexual76,77 interactions also exhibit more similar microbial communities. In yellow baboons, for instance, individuals that frequently groom each other exhibit highly similar GI microbiomes (about 15–20% of shared microbial taxa), even when controlling for kinship and shared diet.74 In kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla), breeding pairs exhibit higher similarity in their cloacal communities than non-breeding pairs.77 These “socially structured” microbial taxa are further preferentially found in some taxonomic groups such as anaerobic GI microbes that probably need intimate physical contacts to be transmitted as they do not survive in the environment.3 In baboons, for example, these socially shared microbial strains include the families Bifidobacteriaceae, Coriobacteriaceae, and Veillonellaceae that have been linked to beneficial health effects in humans. The duration and intimacy of socio-sexual contacts are therefore expected to influence both the quantity and taxonomic composition of the shared microbial taxa.3

Disentangling the different transmission routes

In wild animal populations, unraveling the precise source of newly acquired microbes in a given host, whether stemming from social or environmental factors, remains challenging. Two fundamental predictions can nonetheless offer valuable insights. First, socially acquired microbes should be host-specific and body site-specific and, in the case of the GI microbiome, it should be mostly strict or facultative anaerobes, while environmentally acquired microbes should be aerobes (or facultative) anaerobes.3 Second, within a given social group, individuals should be exposed to a similar set of environmental microbes because the physical environment tends to be relatively homogeneous (same soil, same water sources, and similar diet). Hence, the presence or abundance of environmentally acquired microbes should not vary based on the social environment. In contrast, the social environment is highly heterogeneous (each individual has more or less preferred partners and many dyads never interact, for example). The presence or abundance of socially transmitted microbes should thus closely follow the social network and the inter-individual variation in the degree of sociality.

The “social microbiome” likely mediates the effects of early life adversity, social integration and social status on fitness in mammals

Given that maternal vertical transmission shapes the trajectory of early life microbiome maturation, it will likely modulate offspring developmental outcomes.78 Early life microbial colonization and diversification are known to influence infants’ growth and phenotypic development,79,80 the maturation and education of the immune system,17 as well as neurodevelopment,81 thus leading to profound health and fitness consequences across the life course.82 In humans, numerous clinical studies have shown how perturbations in the normal pattern of mother-offspring vertical transmission during the perinatal period (e.g., Caesarean section, maternal antibiotic use, or formula feeding) can translate into metabolic- and immune-associated disorders in offspring, that often persist during childhood and until adulthood, such as type 1 diabetes, obesity, IBD, or asthma.82 In rodents, experimental manipulations have demonstrated that maternal stress during pregnancy causally alters vaginal microbiota composition, and in turn, the vertical transmission of this dysbiotic community results in impaired metabolic, immunologic, and neurodevelopmental functions in the neonate.78,83

In mammals, social adverse conditions challenging the initial quantity and quality of vertical transmission of maternal microbes could therefore mediate the relationships between early-life social adversity and fitness outcomes pervasively observed in nature11 (Figure 1B). For instance, early maternal death may deprive offspring from an important source of microbes, leading to the establishment of poorly diversified microbiomes and/or characterized by the absence of beneficial microbial taxa in offspring (Figure 1B). Such microbially mediated maternal effects could explain, at least partly, the adverse effects of early maternal loss on offspring development and fitness. In addition, low-ranking or poorly socially integrated mothers may carry and transmit less diversified milk or GI microbiomes to their infants, potentially explaining why their offspring usually grow slower and display shorter lifespan than those born to high-ranking mothers or to those benefiting from a rich social life.5 Recent studies in mammals have shown, for example, that maternal traits, such as parity (i.e., the number of times a female reproduced), are associated with differences in offspring’s GI composition and translates into variation in the speed of offspring’s GI microbiome maturation.79

Longitudinal behavioral and microbial data on mother-offspring dyads are now needed to address those outstanding questions and compare the relative importance of the different sources of microbes (i.e., maternal, conspecifics, and environment) that participate to the assembly of the infant microbiomes according to developmental conditions (with or without adversity) to ultimately link them to fitness proxies (e.g., immune markers, physiological markers of energetic conditions, somatic growth, motor-skill development, and survival to weaning). In particular, we expect that maternal microbial transmission would mediate the effect of the social environment on offspring fitness in species (1) with prolonged periods of lactation and maternal care, (2) where offspring phenotypic development is sensitive to maternal energetic conditions, and (3) when mother-offspring social bonds continue post-weaning and are important for offspring fitness, such as across mother-daughter dyads in female philopatric species. In such cases, differences in the quality of post-weaning maternal transmission will continue to widen differences between offspring benefiting from a high-quality mother (i.e., with high microbial diversity and/or enriched in beneficial symbionts) vs. low quality mother (with poor microbial diversity and/or depleted in beneficial symbionts).

The social microbiome might not only mediate the relationship between early life adversity and fitness, but also between the adult social environment (social integration and status throughout lifespan) and fitness. Highly socially integrated or high-ranking individuals are generally exposed to numerous socio-sexual partners and have more choice over their partners.84 These highly integrated and/or high-ranking individuals are thus likely to harbor more diverse and stable microbiomes throughout their life because of their rich social life3 but could also acquire more beneficial microbes if they select socio-sexual partners depending on their microbial communities. Microbes evolve rapidly by mutation, recombination and horizontal gene transfers85 and respond rapidly to local selective pressures.40 Each individual thus harbors a unique set of microbes and some might provide adaptive benefits to the host (e.g., adapted to local pathogenic pressures or providing nutritional advantages). Social individuals will be more likely to acquire those rare beneficial symbionts. Both diversified and beneficial microbial communities would in turn directly improve nutrition, physiology and, above all, pathogen resistance in these social individuals, and ultimately explain their improved health, longevity, and reproductive success27,28,86 (Figure 1B). Yet, empirical evidence of microbially mediated health and protective benefits acquired from the social environment remains elusive so far, and is currently restricted to eusocial insects. In cockroaches and termites (Dictyoptera sp., Cryptocercus punctulatus), coprophagy is essential to newly hatched nymphs to acquire cellulolytic intestinal symbionts from conspecifics and process their nutritional intake.87 In honeybees (Apis mellifera), GI microbes acquired from nestmates in early life reduce individual susceptibility to the protozoa Lotmaria passim.88 Similarly, socially transmitted GI microbial taxa protect bumble bees (Bombus terrestris) from infection by the trypanosomatid Crithidia bombi.89

Yet, some socially transmitted microbes might be pathogenic. Indeed, while natural selection is expected to decrease pathogenicity and virulence of vertically transmitted symbionts, no such selection exerts on horizontally transmitted microbes.90 Pathogens in particular have efficient dispersal strategies (they are typically facultative anaerobes) and are likely to be horizontally transmitted, as recently found in the human oral social microbiome.91 On the other side, if the microbes that positively impact host fitness are less likely to be environmentally transmissible (such as any anaerobic fermentative bacteria providing nutritional functions), social interactions will present the only possible pathway by which symbionts of high functional significance are acquired.3 If acquiring beneficial microbes from conspecifics provide important fitness benefits to the host, selection should favor behavioral adaptations to ensure that individuals will obtain those microbes from the social environment, at each generation. Selection will act differently on vertically transmitted beneficial microbes (those are very likely to be transmitted faithfully from mother to offspring in mammalian species with extended maternal care) versus on horizontally transmitted beneficial microbes who will need to be acquired de novo at each generation (those will be transmitted more unfaithfully and require the evolution of specific social behaviors toward conspecifics to be transmitted—e.g., preferentially grooming healthy individuals). In group-living mammals, we can thus expect that social behavior may have evolved to buffer against the transmission of pathogenic microbes (e.g., via avoidance of sick individuals or careful socio-sexual partner choice92), while facilitating sharing the beneficial ones. Empirical investigation needs now to be undertaken in social mammals to elucidate these pathways.

In practice, horizontal social transmission is assessed by linking social networks or dyadic social bonds to microbial similarities among individuals, while controlling for dietary, environmental and genetic similarity among hosts. Sarkar et al.3 developed detailed predictions about the expected strength of social microbial transmission according to the species-level (e.g., social and mating system, dispersal, and parenting style), group-level (e.g., group size, social network modularity, and age-sex distribution) and individual-level (e.g., number of social partners, network centrality, rank, age, and sex) characteristics. Linking the composition of the social microbiome to host fitness requires longitudinal, individually centred data on social behaviors, parasitic and nutritional statuses, and immunological markers to test, for example, whether highly social individuals benefit from higher resistance to pathogen infections via the diversity or composition of their microbiome and if protective symbionts are also the ones that are socially acquired. Structural equation models (SEMs), such as path analysis79 or mediation analysis,93 can resolve complex multivariate relationships among a suite of interrelated variables and emerge as promising statistical tools to address whether the relationship between sociality and fitness is mediated significantly and directly or indirectly by the social microbiome. Such models would further allow researchers to assess the relative importance of the “chronic stress” hypothesis (e.g., measured by GCs concentration and/or immune markers) and the “social microbiome” hypothesis. We expect that horizontal social transmission would mediate the effect of the social environment on individual fitness in species (1) living in large groups, (2) with hierarchical relationships, and (3) well differentiated and stable social and sexual interactions. Such characteristics may, indeed, generate important inter-individual differences in horizontal social transmission.

Effects of the GI microbiome on physiological stress

The GI microbiome engages in a bidirectional communication with the brain through neural, endocrine and immune pathways (referred to as the “gut-brain axis”)21 and is a key player in the physiology of the stress response during both development and adulthood.94 This association should be considered when exploring the physiological pathways underlying the sociality-fitness nexus.

GI microbes produce a variety of neurotransmitters (e.g., gamma-aminobutyric acid [GABA] and serotonin) and metabolites (e.g., short chain fatty acids) that interact with the HPA axis, influence GCs synthesis, and participate to signaling pathways in the brain.21,94,95 Laboratory studies have demonstrated the extent to which the development and regulation of the host’s HPA axis activity is controlled by the GI microbiome and, in turn, how the GI microbiome responds to signals sent by the HPA axis.95,96 In adult mice, for example, Enterococcus faecalis promotes affiliative social behavior during encounters with a novel individual by dampening the HPA-axis-mediated production of corticosterone and by suppressing overactive stress response.97 In early life, the programming of the HPA axis by the GI microbiome shapes the overall stress reactivity over lifespan: germ-free mice generally display HPA hyper-activity and produce abnormal anxiety-like behaviors.94,96 Maternal separation or antibiotic exposure that translate into alterations of early microbial compositions can result in the long-term modulation of stress-related physiology and behaviors.98 By contrast, microbial recolonization can normalize adrenal responses but only within a critical window during early development.99

To date, the few empirical studies addressing these questions in wild populations have primarily concentrated on understanding the impact of the stress response and elevated GCs production on the GI microbiome,100,101 with less emphasis on exploring the reciprocal aspect of this relationship. In turn, we propose here that severe disruptions in the social microbiome, due to e.g., early life adversities or social isolation, may impact the host’s HPA axis activity and trigger in turn the release of stress-related hormones and associated inflammatory responses. Disentangling complex and related effects of the social microbiomes vs. the social stress response is an important avenue for future research.

Conclusions and future directions

The social transmission of microbes has the potential to confer fitness benefits in ways that could explain the sociality-fitness nexus, to a similar—or even higher—extent than chronic social stress. As discussed previously, microbiomes regulate virtually all aspects of host physiology, with pervasive effects on endocrine, metabolism, and immune functions of organisms during development and adulthood. More than 90% of the current studies have focused on the GI microbiome but microbes at multiple body sites (oral, nasal, skin, or genital microbiomes) appear as promising candidates to understand inter-individual differences in reproductive success and lifespan in nature and deserved further investigation. Additionally, microbially mediated pathogen protection has the potential to explain large effect sizes of the social environment on fitness because pathogens exert one of the most important selective pressures on their hosts in nature. To interpret the widespread and pervasive sociality-fitness nexus reported in wild social mammals, we propose here that a far-reaching part of the explanatory power traditionally attributed to chronic social stress might in fact directly result both from the diversification of these communities via socio-sexual contacts, and from the social transmission of beneficial microbial communities.

Long-term studies in wild social mammals are particularly well suited to investigate this alternative mechanism. First, the social environments of nonhuman mammals are simpler than those experienced by humans and measures of early life adversity, social integration, and social status have all been well characterized and are strongly linked to individual fitness.5 Furthermore, most studies of host-microbiome relationships have been conducted either in (western) humans, where experimentations are limited for ethical reasons, or in laboratory (germ-free) rodents. The continued utilization of these models restricts our understanding of the microbiome as a complex ecosystem governed by eco-evolutionary processes. Wild mammal microbiomes are in less altered states than those found in contemporary humans that experience modified selective pressures due to modern medicine, industrial diet and lifestyle.38 There is thus now an urgent need to incorporate studies of non-model species living in ecologically realistic environments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a research grant from the University of Montpellier Programme d’Excellence I-SITE Soutien à la Recherche, 2022, obtained by A.B. We thank Lauren Petrullo for providing feedbacks on an early manuscript and the anonymous reviewer for their comments that improved the manuscript.

Author contributions

A.B. and M.J.E.C: conceptualization, writing – original draft, and writing – review & editing.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Alice Baniel, Email: alice.baniel@umontpellier.fr.

Marie J.E. Charpentier, Email: marie.charpentier@umontpellier.fr.

References

- 1.Ebert D. The epidemiology and evolution of symbionts with mixed-mode transmission. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2013;44:623–643. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson C.D., Bohannan B.J., Britton R.A. Scales of persistence: transmission and the microbiome. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019;50:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarkar A., Harty S., Johnson K.V.A., Moeller A.H., Archie E.A., Schell L.D., Carmody R.N., Clutton-Brock T.H., Dunbar R.I.M., Burnet P.W.J. Microbial transmission in animal social networks and the social microbiome. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020;4:1020–1035. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holt-Lunstad J., Smith T.B., Layton J.B. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snyder-Mackler N., Burger J.R., Gaydosh L., Belsky D.W., Noppert G.A., Campos F.A., Bartolomucci A., Yang Y.C., Aiello A.E., O’Rand A., et al. Social determinants of health and survival in humans and other animals. Science. 2020;368:eaax9553. doi: 10.1126/science.aax9553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sterlemann V., Ganea K., Liebl C., Harbich D., Alam S., Holsboer F., Müller M.B., Schmidt M.V. Long-term behavioral and neuroendocrine alterations following chronic social stress in mice: implications for stress-related disorders. Horm. Behav. 2008;53:386–394. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi A., Flanigan M.E., McEwen B.S., Russo S.J. Aggression, social stress, and the immune system in humans and animal models. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018;12:56. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farbstein D., Hollander N., Peled O., Apter A., Fennig S., Haberman Y., Gitman H., Yaniv I., Shkalim V., Pick C.G., et al. Social isolation dysregulates endocrine and behavioral stress while increasing malignant burden of spontaneous mammary tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:22393–22398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910753106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Razzoli M., Nyuyki-Dufe K., Gurney A., Erickson C., McCallum J., Spielman N., Marzullo M., Patricelli J., Kurata M., Pope E.A., et al. Social stress shortens lifespan in mice. Aging Cell. 2018;17:e12778. doi: 10.1111/acel.12778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campos F.A., Archie E.A., Gesquiere L.R., Tung J., Altmann J., Alberts S.C. Glucocorticoid exposure predicts survival in female baboons. Sci. Adv. 2021;7 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abf6759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu A., Petrullo L., Carrera S., Feder J., Schneider-Crease I., Snyder-Mackler N. Developmental responses to early-life adversity: evolutionary and mechanistic perspectives. Evol. Anthropol. 2019;28:249–266. doi: 10.1002/evan.21791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bunea I.M., Szentágotai-Tătar A., Miu A.C. Early-life adversity and cortisol response to social stress: a meta-analysis. Transl. Psychiatry. 2017;7:1274. doi: 10.1038/s41398-017-0032-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boonstra R. Reality as the leading cause of stress: rethinking the impact of chronic stress in nature. Funct. Ecol. 2013;27:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beehner J.C., Bergman T.J. The next step for stress research in primates: to identify relationships between glucocorticoid secretion and fitness. Horm. Behav. 2017;91:68–83. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoenle L.A., Zimmer C., Miller E.T., Vitousek M.N. Does variation in glucocorticoid concentrations predict fitness? A phylogenetic meta-analysis. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2021;300 doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2020.113611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flint H.J., Scott K.P., Louis P., Duncan S.H. The role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;9:577–589. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al Nabhani Z., Eberl G. Imprinting of the immune system by the microbiota early in life. Mucosal Immunol. 2020;13:183–189. doi: 10.1038/s41385-020-0257-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Round J.L., Mazmanian S.K. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:313–323. doi: 10.1038/nri2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abt M.C., Pamer E.G. Commensal bacteria mediated defenses against pathogens. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2014;29:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ducarmon Q.R., Zwittink R.D., Hornung B.V.H., van Schaik W., Young V.B., Kuijper E.J. Gut microbiota and colonization resistance against bacterial enteric infection. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2019;83:e00007-19. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00007-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cryan J.F., O’riordan K.J., Cowan C.S.M., Sandhu K.V., Bastiaanssen T.F.S., Boehme M., Codagnone M.G., Cussotto S., Fulling C., Golubeva A.V., et al. The microbiota-gut-brain axis. Physiol. Rev. 2019;99:1877–2013. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mallott E.K., Amato K.R. Host specificity of the gut microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021;19:639–653. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00562-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grieneisen L., Dasari M., Gould T.J., Björk J.R., Grenier J.C., Yotova V., Jansen D., Gottel N., Gordon J.B., Learn N.H., et al. Gut microbiome heritability is nearly universal but environmentally contingent. Science. 2021;373:181–186. doi: 10.1126/science.aba5483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Youngblut N.D., Reischer G.H., Walters W., Schuster N., Walzer C., Stalder G., Ley R.E., Farnleitner A.H. Host diet and evolutionary history explain different aspects of gut microbiome diversity among vertebrate clades. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2200. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10191-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang S., Ryan C.A., Boyaval P., Dempsey E.M., Ross R.P., Stanton C. Maternal vertical transmission affecting early-life microbiota development. Trends Microbiol. 2020;28:28–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2019.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lombardo M.P. Access to mutualistic endosymbiotic microbes: an underappreciated benefit of group living. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2008;62:479–497. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ezenwa V.O., Ghai R.R., McKay A.F., Williams A.E. Group living and pathogen infection revisited. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2016;12:66–72. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amato K.R., Arrieta M.C., Azad M.B., Bailey M.T., Broussard J.L., Bruggeling C.E., Claud E.C., Costello E.K., Davenport E.R., Dutilh B.E., et al. The human gut microbiome and health inequities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2017947118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guittar J., Shade A., Litchman E. Trait-based community assembly and succession of the infant gut microbiome. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:512. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08377-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Muinck E.J., Trosvik P. Individuality and convergence of the infant gut microbiota during the first year of life. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2233. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04641-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Björk J.R., Dasari M.R., Roche K., Grieneisen L., Gould T.J., Grenier J.C., Yotova V., Gottel N., Jansen D., Gesquiere L.R., et al. Synchrony and idiosyncrasy in the gut microbiome of wild baboons. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2022;6:955–964. doi: 10.1038/s41559-022-01773-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki T.A. Links between natural variation in the microbiome and host fitness in wild mammals. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2017;57:756–769. doi: 10.1093/icb/icx104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flint H.J., Scott K.P., Duncan S.H., Louis P., Forano E. Microbial degradation of complex carbohydrates in the gut. Gut Microb. 2012;3:289–306. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kohl K.D., Weiss R.B., Cox J., Dale C., Dearing M.D. Gut microbes of mammalian herbivores facilitate intake of plant toxins. Ecol. Lett. 2014;17:1238–1246. doi: 10.1111/ele.12329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez-Guryn K., Hubert N., Frazier K., Urlass S., Musch M.W., Ojeda P., Pierre J.F., Miyoshi J., Sontag T.J., Cham C.M., et al. Small intestine microbiota regulate host digestive and absorptive adaptive responses to dietary lipids. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:458–469.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morrison D.J., Preston T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microb. 2016;7:189–200. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2015.1134082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amato K.R., Leigh S.R., Kent A., Mackie R.I., Yeoman C.J., Stumpf R.M., Wilson B.A., Nelson K.E., White B.A., Garber P.A. The gut microbiota appears to compensate for seasonal diet variation in the wild black howler monkey (Alouatta pigra) Microb. Ecol. 2015;69:434–443. doi: 10.1007/s00248-014-0554-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amato K.R. Incorporating the gut microbiota into models of human and non-human primate ecology and evolution. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2016;159:196–215. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macke E., Tasiemski A., Massol F., Callens M., Decaestecker E. Life history and eco-evolutionary dynamics in light of the gut microbiota. Oikos. 2017;126:508–531. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki T.A., Ley R.E. The role of the microbiota in human genetic adaptation. Science. 2020;370 doi: 10.1126/science.aaz6827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McLaren M.R., Callahan B.J. Pathogen resistance may be the principal evolutionary advantage provided by the microbiome. Philos Trans R Soc B: Biol. Sci. 2020;375 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2019.0592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buffie C.G., Pamer E.G. Microbiota-mediated colonization resistance against intestinal pathogens. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13:790–801. doi: 10.1038/nri3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashida H., Ogawa M., Kim M., Mimuro H., Sasakawa C. Bacteria and host interactions in the gut epithelial barrier. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;8:36–45. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lawley T.D., Clare S., Walker A.W., Goulding D., Stabler R.A., Croucher N., Mastroeni P., Scott P., Raisen C., Mottram L., et al. Antibiotic treatment of Clostridium difficile carrier mice triggers a supershedder state, spore-mediated transmission, and severe disease in immunocompromised hosts. Infect. Immun. 2009;77:3661–3669. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00558-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosshart S.P., Vassallo B.G., Angeletti D., Hutchinson D.S., Morgan A.P., Takeda K., Hickman H.D., McCulloch J.A., Badger J.H., Ajami N.J., et al. Wild mouse gut microbiota promotes host fitness and improves disease resistance. Cell. 2017;171:1015–1028.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ximenez C., Torres J. Development of microbiota in infants and its role in maturation of gut mucosa and immune system. Arch. Med. Res. 2017;48:666–680. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chabé M., Lokmer A., Ségurel L. Gut protozoa: friends or foes of the human gut microbiota? Trends Parasitol. 2017;33:925–934. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pichon M., Lina B., Josset L. Impact of the respiratory microbiome on host responses to respiratory viral infection. Vaccines. 2017;5:40. doi: 10.3390/vaccines5040040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang J., Li F., Sun R., Gao X., Wei H., Li L.J., Tian Z. Bacterial colonization dampens influenza-mediated acute lung injury via induction of M2 alveolar macrophages. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2106–2110. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vanderwolf K.J., Campbell L.J., Goldberg T.L., Blehert D.S., Lorch J.M. Skin fungal assemblages of bats vary based on susceptibility to white-nose syndrome. ISME J. 2021;15:909–920. doi: 10.1038/s41396-020-00821-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lima M.T., Andrade A.C.d.S.P., Oliveira G.P., Nicoli J.R., Martins F.d.S., Kroon E.G., Abrahão J.S., Kroon E.G., Abrahão J.S. Virus and microbiota relationships in humans and other mammals: an evolutionary view. Hum. Microb. J. 2019;11 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Șchiopu C.G., Ștefănescu C., Boloș A., Diaconescu S., Gilca-Blanariu G.E., Ștefănescu G. Functional gastrointestinal disorders with psychiatric symptoms: involvement of the microbiome–gut–brain axis in the pathophysiology and case management. Microorganisms. 2022;10 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10112199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lozupone C.A., Stombaugh J.I., Gordon J.I., Jansson J.K., Knight R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2012;489:220–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huttenhower C., Gevers D., Knight R., Abubucker S., Badger J.H., Chinwalla A.T., Creasy H.H., Earl A.M., Fitzgerald M.G., Fulton R.S., et al. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blaser M.J., Falkow S. What are the consequences of the disappearing human microbiota? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:887–894. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jones M.L., Rivett D.W., Pascual-García A., Bell T. Relationships between community composition, productivity and invasion resistance in semi-natural bacterial microcosms. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.71811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilmanski T., Diener C., Rappaport N., Patwardhan S., Wiedrick J., Lapidus J., Earls J.C., Zimmer A., Glusman G., Robinson M., et al. Gut microbiome pattern reflects healthy ageing and predicts survival in humans. Nat. Metab. 2021;3:274–286. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00348-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Relman D.A. The human microbiome: ecosystem resilience and health. Nutr. Rev. 2012;70:S2–S9. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coyte K.Z., Schluter J., Foster K.R. The ecology of the microbiome: networks, competition, and stability. Science. 2015;350:663–666. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Costello E.K., Lauber C.L., Hamady M., Fierer N., Gordon J.I., Knight R. Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science. 2009;326:1694–1697. doi: 10.1126/science.1177486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oh J., Byrd A.L., Park M., NISC Comparative Sequencing Program. Kong H.H., Segre J.A. Temporal stability of the human skin microbiome. Cell. 2016;165:854–866. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grice E.A., Kong H.H., Conlan S., Deming C.B., Davis J., Young A.C., NISC Comparative Sequencing Program. Bouffard G.G., Blakesley R.W., Murray P.R., et al. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science. 2009;324:1190–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.1171700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ceccarani C., Foschi C., Parolin C., D’Antuono A., Gaspari V., Consolandi C., Laghi L., Camboni T., Vitali B., Severgnini M., Marangoni A. Diversity of vaginal microbiome and metabolome during genital infections. Sci. Rep. 2019;9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50410-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ma J., Li Z., Zhang W., Zhang C., Zhang Y., Mei H., Zhuo N., Wang H., Wang L., Wu D. Comparison of gut microbiota in exclusively breast-fed and formula-fed babies: a study of 91 term infants. Sci. Rep. 2020;10 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72635-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roger L.C., Costabile A., Holland D.T., Hoyles L., McCartney A.L. Examination of faecal Bifidobacterium populations in breast- and formula-fed infants during the first 18 months of life. Microbiology (N. Y.) 2010;156:3329–3341. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.043224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ferretti P., Pasolli E., Tett A., Asnicar F., Gorfer V., Fedi S., Armanini F., Truong D.T., Manara S., Zolfo M., et al. Mother-to-infant microbial transmission from different body sites shapes the developing infant gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;24:133–145.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moeller A.H., Suzuki T.A., Phifer-Rixey M., Nachman M.W. Transmission modes of the mammalian gut microbiota. Science. 2018;362:453–457. doi: 10.1126/science.aat7164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Valles-Colomer M., Blanco-Míguez A., Manghi P., Asnicar F., Dubois L., Golzato D., Armanini F., Cumbo F., Huang K.D., Manara S., et al. The person-to-person transmission landscape of the gut and oral microbiomes. Nature. 2023;614:125–135. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05620-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Asnicar F., Manara S., Zolfo M., Truong D.T., Scholz M., Armanini F., Ferretti P., Gorfer V., Pedrotti A., Tett A., Segata N. Studying vertical microbiome transmission from mothers to infants by strain-level metagenomic profiling. mSystems. 2017;2 doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00164-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jost T., Lacroix C., Braegger C.P., Rochat F., Chassard C. Vertical mother-neonate transfer of maternal gut bacteria via breastfeeding. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;16:2891–2904. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Suzuki T.A., Fitzstevens J.L., Schmidt V.T., Enav H., Huus K.E., Mbong Ngwese M., Grießhammer A., Pfleiderer A., Adegbite B.R., Zinsou J.F., et al. Codiversification of gut microbiota with humans. Science. 2022;377:1328–1332. doi: 10.1126/science.abm7759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Archie E.A., Tung J. Social behavior and the microbiome. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2015;6:28–34. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Perofsky A.C., Lewis R.J., Abondano L.A., Difiore A., Meyers L.A. Hierarchical social networks shape gut microbial composition in wild Verreaux’s sifaka. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2017;284 doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tung J., Barreiro L.B., Burns M.B., Grenier J.C., Lynch J., Grieneisen L.E., Altmann J., Alberts S.C., Blekhman R., Archie E.A. Social networks predict gut microbiome composition in wild baboons. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.05224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Raulo A., Allen B.E., Troitsky T., Husby A., Firth J.A., Coulson T., Knowles S.C.L. Social networks strongly predict the gut microbiota of wild mice. ISME J. 2021;15:2601–2613. doi: 10.1038/s41396-021-00949-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Escallón C., Belden L.K., Moore I.T. The cloacal microbiome changes with the breeding season in a wild bird. Integr. Org. Biol. 2019;1 doi: 10.1093/iob/oby009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.White J., Mirleau P., Danchin E., Mulard H., Hatch S.A., Heeb P., Wagner R.H. Sexually transmitted bacteria affect female cloacal assemblages in a wild bird. Ecol. Lett. 2010;13:1515–1524. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jašarević E., Bale T.L. Prenatal and postnatal contributions of the maternal microbiome on offspring programming. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2019;55 doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2019.100797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Petrullo L., Baniel A., Jorgensen M.J., Sams S., Snyder-Mackler N., Lu A. The early life microbiota mediates maternal effects on offspring growth in a nonhuman primate. iScience. 2022;25 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.103948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Blanton L.V., Charbonneau M.R., Salih T., Barratt M.J., Venkatesh S., Ilkaveya O., Subramanian S., Manary M.J., Trehan I., Jorgensen J.M., et al. Gut bacteria that prevent growth impairments transmitted by microbiota from malnourished children. Science. 2016;351:6275. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pronovost G.N., Hsiao E.Y. Perinatal interactions between the microbiome, immunity, and neurodevelopment. Immunity. 2019;50:18–36. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stiemsma L.T., Michels K.B. The role of the microbiome in the developmental origins of health and disease. Pediatrics. 2018;141 doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hartman S., Sayler K., Belsky J. Prenatal stress enhances postnatal plasticity: the role of microbiota. Dev. Psychobiol. 2019;61:729–738. doi: 10.1002/dev.21816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schino G. Grooming, competition and social rank among female primates: a meta-analysis. Anim. Behav. 2001;62:265–271. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brito I.L. Examining horizontal gene transfer in microbial communities. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021;19:442–453. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00534-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rowe M., Veerus L., Trosvik P., Buckling A., Pizzari T. The reproductive microbiome: an emerging driver of sexual selection, sexual conflict, mating systems, and reproductive isolation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2020;35:220–234. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2019.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nalepa C.A., Bignell D.E., Bandi C. Detritivory, coprophagy, and the evolution of digestive mutualisms in Dictyoptera. Insectes Soc. 2001;48:194–201. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schwarz R.S., Moran N.A., Evans J.D. Early gut colonizers shape parasite susceptibility and microbiota composition in honey bee workers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:9345–9350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606631113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Koch H., Schmid-Hempel P. Socially transmitted gut microbiota protect bumble bees against an intestinal parasite. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:19288–19292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110474108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ewald P.W. Transmission modes and evolution of the parasitism-mutualism continuum. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1987;503:295–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb40616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Musciotto F., Dobon B., Greenacre M., Mira A., Chaudhary N., Salali G.D., Gerbault P., Schlaepfer R., Astete L.H., Ngales M., et al. Agta hunter–gatherer oral microbiomes are shaped by contact network structure. Evol. Hum. Sci. 2023;5:e9. doi: 10.1017/ehs.2023.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Stockmaier S., Stroeymeyt N., Shattuck E.C., Hawley D.M., Meyers L.A., Bolnick D.I. Infectious diseases and social distancing in nature. Science. 2021;371:eabc8881. doi: 10.1126/science.abc8881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rosenbaum S., Zeng S., Campos F.A., Gesquiere L.R., Altmann J., Alberts S.C., Li F., Archie E.A. Social bonds do not mediate the relationship between early adversity and adult glucocorticoids in wild baboons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:20052–20062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004524117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Foster J.A., Rinaman L., Cryan J.F. Stress & the gut-brain axis: regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiol. Stress. 2017;7:124–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Vodička M., Ergang P., Hrnčíř T., Mikulecká A., Kvapilová P., Vagnerová K., Šestáková B., Fajstová A., Hermanová P., Hudcovic T., et al. Microbiota affects the expression of genes involved in HPA axis regulation and local metabolism of glucocorticoids in chronic psychosocial stress. Brain Behav. Immun. 2018;73:615–624. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Clarke G., Grenham S., Scully P., Fitzgerald P., Moloney R.D., Shanahan F., Dinan T.G., Cryan J.F. The microbiome-gut-brain axis during early life regulates the hippocampal serotonergic system in a sex-dependent manner. Mol. Psychiatr. 2013;18:666–673. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wu W.L., Adame M.D., Liou C.W., Barlow J.T., Lai T.T., Sharon G., Schretter C.E., Needham B.D., Wang M.I., Tang W., et al. Microbiota regulate social behaviour via stress response neurons in the brain. Nature. 2021;595:409–414. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03669-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rincel M., Darnaudéry M. Maternal separation in rodents: a journey from gut to brain and nutritional perspectives. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2020;79:113–132. doi: 10.1017/S0029665119000958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sudo N., Chida Y., Aiba Y., Sonoda J., Oyama N., Yu X.N., Kubo C., Koga Y. Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. J. Physiol. 2004;558:263–275. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.063388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Stothart M.R., Bobbie C.B., Schulte-Hostedde A.I., Boonstra R., Palme R., Mykytczuk N.C.S., Newman A.E.M. Stress and the microbiome: linking glucocorticoids to bacterial community dynamics in wild red squirrels. Biol. Lett. 2016;12 doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2015.0875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Noguera J.C., Aira M., Pérez-Losada M., Domínguez J., Velando A. Glucocorticoids modulate gastrointestinal microbiome in a wild bird. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018;5 doi: 10.1098/rsos.171743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]