Abstract

To investigate the molecular characteristics and antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from patients with diarrhea in Korea, 327 S. aureus strains were collected between 2007 and 2022. The presence of staphylococcal enterotoxin (SE) and toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1) genes in S. aureus isolates was determined by PCR. The highest expression of the TSST-1 gene was found in the GIMNO type (43.1% of GIMNO type). GIMNO type (Type I) refers to each staphylococcal enterotoxin (SE) gene gene (initials of genes): G = seg; I = sei; M = selm; N = seln; O = selo. Moreover, Type I isolates showed a significantly higher resistance to most antibiotics. A total of 195 GIMNO-type S. aureus strains were analyzed using multilocus sequence typing (MLST), and 18 unique sequence types (STs) were identified. The most frequent sequence type was ST72 (36.9%), followed by ST5 (22.1%) and ST30 (16.9%). Interestingly, ST72 strains showed a higher prevalence of MRSA than the other STs. In conclusion, our results were the first reported for S. aureus strains in Korea, which significantly expanded S. aureus genotype information for the surveillance of pathogenic S. aureus and may provide important epidemiological information to resolve several infectious diseases caused by S. aureus.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10068-023-01478-9.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, Antibiotic resistance, Diarrhea

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is a major bacterial pathogen associated with a number of human diseases (Argudín et al., 2010; Gherardi, 2023). S. aureus secretes various exoproteins [such as staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEs), toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1) and exfoliative toxins (ETs)] which disturb the host immune system and cause diseases such as food poisoning (Appelbaum, 2007; Dinges et al., 2000; G Abril et al., 2020; Hennekinne et al., 2012), toxic shock syndrome (McCormick et al., 2001), and scalded skin syndrome (Ladhani et al., 1999). S. aureus food poisoning caused by SEs is one of the most common foodborne diseases worldwide (Salgado-Pabón et al., 2021). According to the food poisoning statistics system in Korea (www.kfda.go.kr/e-stat/), staphylococcal food poisoning outbreaks occurred in 150 cases and 3720 patients appeared from these cases between 2007 and 2022. In a study conducted in Seoul before 2010, S. aureus was the leading cause of bacterial diarrhea in children. It affects approximately half of the cases, and in subsequent individual studies focusing on specific organs, it remained the predominant bacterial agent (excluding cases involving repetitive infections) (Ryoo, 2021). Also, according to the acute diarrhea laboratory surveillance system (EnterNet-Korea), S. aureus accounts for 34% of the gradually increasing separation rate from diarrhea patients (Kim et al., 2013). Previous studies have highlighted the importance of characterizing S. aureus as a pathogen. Moreover, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is known to cause morbidity and mortality (Algammal et al., 2020; Enright et al., 2002; Guo et al., 2020; Lowy, 2003; Saba et al., 2022). Methicillin resistance in S. aureus is caused by the acquisition of an altered penicillin-binding protein (PBP2a) encoded by the mecA gene located on a mobile genetic element, the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) (Liu et al., 2016; Lowy, 2003).

SEs are heat-stable enterotoxins that are the main cause of staphylococcal food-associated diarrhea outbreaks in humans (Argudín et al., 2010; Pinchuk et al., 2010; Principato et al., 2014). To date, 22 SEs have been identified (Argudín et al., 2010; Dinges et al., 2000; Pinchuk et al., 2010). Based on amino acid sequence comparisons, SEs have been divided into several groups: SEA to SEV, except for SEF, which has been renamed TSST-1 (Hu et al., 2021; Pinchuk et al., 2010). TSST-1 and SEs share common structural and biological properties and are potent activators of T-cell populations, leading to massive systemic cytokine release. They are also known as pyrogenic toxin superantigens (PTSAgs) (Balaban et al., 2000; Choi et al., 1989; Li et al., 2019).

Mobile genetic elements (MGEs) demonstrate intracellular and intercellular mobility and encode putative virulence factors and molecules that confer resistance to antibiotics (Hazen et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2021; Mullany et al., 2015; Timmonsa et al., 2022). Most SEs are encoded by MGEs, including plasmids, prophages, pathogenicity islands, genomic islands, and genes located next to the staphylococcal cassette chromosome (SCC) implicated in methicillin resistance (Arora et al., 2020; Malachowa et al., 2010). Enterotoxin gene cluster (egc) are widely distributed among MGEs (Hu et al., 2016). MGEs demonstrate intracellular and intercellular mobility, and those within one particular cell are called a ‘‘mobilome’’ (Tansirichaiya et al., 2022). To allow bacteria to adjust readily to new environments, the transfer of MGEs between cells is known as lateral or horizontal gene transfer (HGT) (Malachowa et al., 2010; Schwendimann et al., 2021). HGT occurs as prokaryote-to-prokaryote, prokaryote-to-eukaryote, and eukaryote-to-eukaryote transfers of DNA via transformation, bacteriophage transduction, and conjugation. S. aureus contains many types of MGEs, including plasmids, transposons, insertion sequences, bacteriophages, pathogenic islands, and staphylococcal cassette chromosomes (Malachowa et al., 2010). The seg-sei-sem-sen-seo type is well known to be located on the genomic island νSAβ (SaPIn3/m3) (Balaban et al., 2000; Holtfreter et al., 2004; Li et al., 2022). Staphylococcal pathogenicity islands (SaPIs) are integrated into one of six specific sites on the chromosome (atts), and each site is always in the same orientation. The tsst gene has often been identified using sek and seq in SaPI1, sec and sel in SaPIm1 and SaPIn1, and sel and sec in SaPIbov1 together (Novick et al., 2007; Novick et al., 2017). SaPIs can be mobilized following infection with certain staphylococcal bacteriophages or by the induction of endogenous prophages (Cervera-Alamar et al., 2018). Another prevalent egc type in this study was sea-seh-sek-seq a unique sea type. It has been reported that sea-seh-sek-seq genes are localized on phage ψ3 and the sea gene is carried by prophage Sa3mu or encoded in Sa3mw along with other genes (seg and sek) (Kuroda et al., 2001).

The prevalence of egc in S. aureus isolates from various food sources, such as raw meat, dairy products, milk, and cheese, has been reported worldwide (Bianchi et al., 2013; Hwang et al., 2007; Lim et al., 2023; Normanno, 2007; Viçosa et al., 2013). Moreover, the incidence ratio of egc is higher than that of classical SE genes in various foods (Bianchi et al., 2013; Hwang et al., 2007; Machado et al., 2020; Rosec et al., 2002). Another study reported a high frequency of egc-positive S. aureus isolates in patients with atopic eczema (Mempel et al., 2003; Ogonowska et al., 2020). These studies suggest that egc-positive S. aureus strains are widely distributed in the environment and can cause severe infectious diseases. sea is a high-frequency gene that comprises many gene patterns (Rasmi et al., 2022). The sea gene is the most frequently detected classical SE gene in S. aureus food poisoning (SFP) cases in Korea (Hwang et al., 2013) and Japan (Shimizu et al., 2000).

In this study, to identify the major toxin types and antibiotic resistance patterns of S. aureus isolates in Korea, we conducted molecular analyses and antibiotic resistance assays on S. aureus isolates obtained from patients with diarrhea between 2007 and 2022.

Materials and methods

Identification of bacterial isolates

A total of 327 S. aureus strains were collected, which were isolated from diarrheal patients between 2007 and 2022 in Korea (Supplementary Data Table S1). S. aureus isolates were cultivated in typtic soy agar (Becton Dickinson, USA) overnight at 37 ºC. All isolates were identified as S. aureus by spreading the samples on S. aureus selective medium and mannitol salt agar (BD, USA). Subsequently, PCR was performed using Sa442 S. aureus-specific primers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Primers used in this study

| Set | Toxin | Primer sequence (5ʹ–3ʹ) | Amplicon size (bp) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | sea | F | GGTTATCAATGTGCGGGTGG | 113 | In this study |

| R | GCCATAAATTGATCGGCACT | ||||

| seb | F | TGTTCGGGTATTTGAAGATGG | 155 | In this study | |

| R | CCGTTTCATAAGGCGAGTTG | ||||

| sec | F | GGAGGAATAACAAAACATGAAGG | 216 | In this study | |

| R | TCCTGTTTCATATGGTGAACTG | ||||

| sed | F | GAGGTGTCACTCCACACGAA | 294 | In this study | |

| R | CGGGAAAATCACCCTTAACA | ||||

| see | F | GCATGTATGTACGGGGGTGT | 372 | In this study | |

| R | CAAATCAATATGGAGGTTCTCTGA | ||||

| seg | F | ACGTCTCCACCTGTTGAAGG | 450 | In this study | |

| R | TCCAGATTCAAATGCAGAACC | ||||

| seh | F | CGAAAGCAGAAGATTTACACGA | 524 | In this study | |

| R | TCTAGGAGTTTTCATATCAAATTCAA | ||||

| sei | F | AGGTGATATTGGTGTAGGTAAC | 641 | In this study | |

| R | CATATGATATTTCGACATCAAGATG | ||||

| P2 | sej | F | CATGTATGTATGGTGGAGTAACAC | 103 | In this study |

| R | GGAACAACAGTTCTGATGCTATCAATC | ||||

| sek | F | ATGGCGGAGTCACAGCTACT | 146 | In this study | |

| R | GACATCAATCTCTTGAGCGGTA | ||||

| sel | F | AAAAATGGTTACCGCACAAGA | 220 | In this study | |

| R | GCTTTCTGGAAGACCGTATCC | ||||

| sem | F | GCTGATGTCGGAGTTTTGAA | 317 | In this study | |

| R | TGATGTTCTCCATTAACCCAAA | ||||

| sen | F | CTTATGAGATTGTTCTACATAGCTG | 390 | In this study | |

| R | CTCCTCCGTATAAGCATGATGT | ||||

| seo | F | GCATATGCAAATGAAGAAGATCC | 468 | In this study | |

| R | TTGTGCAGTAACTTTCTTTTTATCTG | ||||

| sep | F | CTGAATTGCAGGGAACTGCT | 538 | In this study | |

| R | ACCAACCGAATCACCAGAAG | ||||

| seq | F | CACTGTTAGCTTGTTTTTCTTCACA | 609 | In this study | |

| R | TGACCAGTTCCGGTGTAAAA | ||||

| tsst -1 | F | TGCAAAAGCATCTACAAACGA | 499 | Srinivasan et al | |

| R | TGTGGATCCGTCATTCATTG | ||||

| mecA | F | GCAATACAATCGCACATACATT | 148 | Chen et al | |

| R | CCTGTTTGAGGGTGGATAGC | ||||

| Sa442 | F | GTCGGGTACACGATATTCTTCACG | 158 | Reischl et al | |

| R | CTCTCGTATGACCAGCTTCGGTAC |

Staphylococcal Enterotoxin (SE) gene screening by multiplex PCR

To detect the SE genes, multiplex PCR assays were performed using the primers listed in Table 1. A single colony of cultured S. aureus was suspended in 100 ul of distilled water, heated at 95ºC for 10 min, and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 2 min. The supernatants were used for the PCR as DNA extracts. PCR for the detection of 16 SE genes was performed using the PowerChek™ S. aureus toxin ID Multiplex PCR kit (Kogenebiotech Co., Korea). PCR was initiated with 5 min pre-incubation at 94 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, and 7 min extension at 72 °C. Amplified products were analyzed by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by staining with SYBR® Gold nucleic acid gel stain (Invitrogen) on a GelDoc XR system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Canada).

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis

S. aureu sstrains were analyzed using MLST. Seven housekeeping genes (arcC, aroE, glpF, gmk, pta, tpi, yqiL) were amplified by PCR using the primers described on the website (http: //saureus.beta.mlst.net). PCR amplifications were carried out under the following condition: 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 60 s, and a 7 min extension at 72 °C with 2.5U/reaction TAKARA Ex Taq™ DNA polymerase (TAKARA, Japan). Raw sequences were concatenated using BioEdit. The sequences of each locus were compared with the allele sequences on the MLST website and STs were identified for each combination of the seven housekeeping gene alleles. Each isolate was characterized by its allelic profile. Cluster analysis of S. aureus isolates was performed using the eBURST program (http: //eburst.mlst.net), and clonal complexes (CCs) were defined using the criterion of six out of seven alleles.

Antimicrobial susceptibility

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing for S.aureus isolates was performed using the VITEK 2 automated system with an AST- P601Card (bioMérieux, France), according to the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). The following antibiotics were tested: ciprofloxacin (CIP), clindamycin (CM), erythromycin (E), nitrofurantoin (FT), gentamicin (GM), inducible clindamycin resistance (ICR), linezolid (LNZ), mupirocin (MUP), oxacillin (OX1), cefoxitin screen (OXSF), benzylpenicillin (P), quinupristin/dalfopristin (QDA), rifampicin (RA), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (SXT), tetracycline (TE), teicoplanin (TEC), telithromycin (TEL), tigecycline (TGC), and vancomycin (VA). To analyze the AST- P601 card VITEK data, we performed an offline beta-lactamase test using a beta-lactamase identification stick (Oxoid) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Detection of mecA gene by real-time PCR

The mecA gene was screening by real-time PCR using mecA gene primers listed in Table 1. Amplifications were performed with the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix also from Applied Biosystems. The thermal cycling process consisted of an initial step at 50 °C for 2 min, followed by an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min. Subsequently, 45 cycles of PCR were performed at 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. The real-time PCR was performed on a LightCycler® 480 (Roche) using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ (Takara). Amplicon quantities were calculated using LightCycler® 480 Software (Roche).

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism version 9 was used for statistical analysis. For comparisons of two variables, chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Profile of enterotoxin genes in S. aureus isolates

S. aureus is a common causative agent of food poisoning and hospital-acquired infections. SEs are activated as superantigens and are the main cause of food contamination (Argudín et al., 2010; Salgado-Pabón et al., 2021). Several SE genes comprise an operon, designated as the enterotoxin gene cluster (egc). The combination of seg and sei was reported to be frequently detected in strains isolated from cases of food poisoning (Schwendimann et al., 2021) in France (Rosec et al., 2002), Taiwan (Chiang et al., 2006) and Korea (Cha et al., 2006). To determine the presence of toxin genes in S. aureus isolates from patients with diarrhea, we performed PCR amplification of 16 SEs and TSST-1 genes in 327 S. aureus isolates. The most frequent toxin gene was seg (62.2% among the isolates), followed by sen (58.1%), seo (57.8%), sei (57.2%), sea (56.3%). sem (48.7%), seh (24.3%), and sek (23.2%). The TSST-1 gene was detected in 32.9% of the isolates (Fig. 1). As shown in Table 2, three notable gene patterns were identified: seg-sei-sem-sen-seo (GIMNO), sea-seh-sek-seq (AHKQ), and sea (A). Out of the total of 327 isolates, 195 of them, accounting for approximately 59.6%, exhibited the GIMNO pattern, which was referred to as Type I. Seventy-five isolates (22.9%) possessed AHKQ pattern (Type II), and 36 isolates (11%) contained sea gene (Type III). The prevalence of Type I was significantly higher than that of the other types among the isolates (p < 0.05). For each type, the isolates contained at least two genes; the detailed detection rates are shown in Supplementary Table S2. Interestingly, the frequency of TSST-1-possessing strains was significantly higher in Type I than in Type II and III strains (Table 2) (p < 0.05). In this study, the highest prevalence of egc type was seg-sei-sem-sen-seo (Type I), which possesses various subtypes. The seg-sei-sem-sen-seo type is well known to be located on the genomic island νSAβ (SaPIn3/m3) (Balaban et al., 2000; Holtfreter et al., 2004; Li et al., 2022). Staphylococcal pathogenicity islands (SaPIs) are integrated into one of six specific sites on the chromosome (atts), and each site is always in the same orientation. The tsst gene has often been identified using sek and seq in SaPI1, sec and sel in SaPIm1 and SaPIn1, and sel and sec in SaPIbov1 together (Novick et al., 2007; Novick et al., 2017). SaPIs can be mobilized following infection with certain staphylococcal bacteriophages or by the induction of endogenous prophages (Cervera-Alamar et al., 2018). Another prevalent egc type in this study was sea-seh-sek-seq a unique sea type. It has been reported that sea-seh-sek-seq genes are localized on phage ψ3 and the sea gene is carried by prophage Sa3mu or encoded in Sa3mw along with other genes (seg and sek) (Kuroda et al., 2001).

Fig. 1.

The occurrence of 17 toxin genes in 327 S.aureus clinical isolates

Table 2.

Staphylococcal enterotoxin (SE) genotyping of S. aureus isolates

| Type | Enterotoxin pattern | No. of isolates (% of total) | No. of positive tsst gene isolates (% of each Type) | No. of positive mecA gene isolates (% of each Type) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | seg-sei-sem-sen-seo | |||

| The isolate including 5 genes | 147 (45.0) | 61 (31.3) | 82 (41.5) | |

| The isolate including 4 genes | 29 (8.9) | 22 (11.3) | 2 (1.0) | |

| The isolate including 3 or 2 genes | 19 (5.8) | 1 (0.5) | 5 (2.6) | |

| Total | 195 (59.6) | 84 (43.1) | 84 (43.1) | |

| II | sea-seh-sek-seq | |||

| The isolate including 4 genes | 58 (17.7) | 10 (13.5) | 1 (1.4) | |

| The isolate including 3 or 2 genes | 17 (5.2) | 5 (6.8) | 7 (9.5) | |

| Total | 75 (22.9) | 15 (20.0) | 8 (10.8) | |

| III | single sea | 36 (11.0) | 6 (16.7) | 2 (5.6) |

| Etc | 16 (4.9) | 2 (11.8) | 6 (35.3) | |

| None enterotoxin | 5 (1.5) | 1 (20.0) | – | |

| Total | 327 | 106 (33.0) | 104 (31.8) | |

Antibiotic resistance analyses of the isolates and MRSA detection

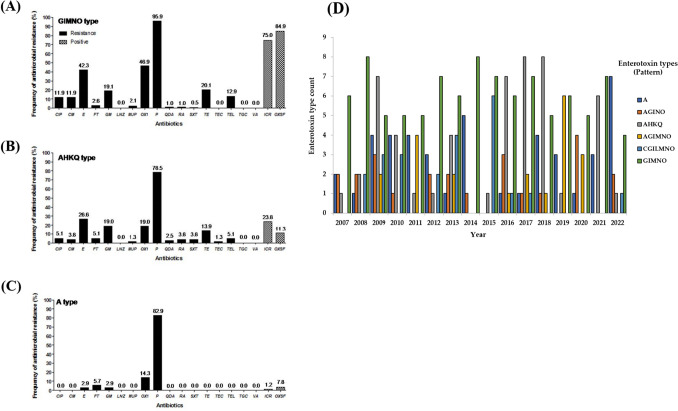

The antibiotic resistance rates of S. aureus isolates are shown in Table 3. Most of the isolates were more resistant to β-lactam antibiotics, benzylpenicillin (89.2%), oxacillin (36.2%), and macrolide; erythromycin (34%), when compared with other antibiotics. These antibiotics are commonly used in clinical treatment. The strains also showed relatively high resistance to aminoglycoside gentamicin (16.4%) and tetracycline; tetracycline (16.4%). However, no other isolates showed resistance to oxazolidinone, linezolid and glycylcycline, tigecycline. Resistance to common antibiotics, such as beta-lactams (benzyl penicillin, oxacillin) and erythromycin, was frequently detected in S aureus strains, which is consistent with other studies (Appelbaum, 2007; Gan et al., 2021; Lowy, 2003). As shown in Fig. 2, antibiotic resistance was significantly different in association with enterotoxin type. Type I isolates showed significantly higher resistance to most antibiotics. In particular, the prevalence of MRSA was higher in Type I (46.9%) than in Types II (19%, p < 0.05) or III (14.3%, p < 0.05). Real-time PCR analysis using mecA gene primer showed that the mecA gene of most MRSA strains in each type was detected. Type I isolates showed significantly higher detection rate to mecA (43.1%). In contrast, the detection rate of mecA of other types was lower than that of Type I (Table 2). The association between the egc type and antibiotic resistance of S. aureus found in this study is very meaningful for the prevention of staphylococcal food-poisoning outbreaks (SFPO), especially MRSA (Johler et al., 2015; Ono et al., 2017). Egc typing may become a simple method for the characterization of the strains related with SFPO and MRSA possessing mecA gene. Therefore, the result that the proportion of MRSA strains was higher in Type I than in the other types suggests that ongoing surveillance and investigation of Type I S aureus isolates are needed.

Table 3.

Antibiotics resistance pattern of S. aureus isolates

| Class of antibiotics | Antibiotics | No. (%) of resistant isolates |

|---|---|---|

| β-lactams | Benzylpenicillin | 294 (89.2) |

| Oxacillin | 119 (36.2) | |

| Glycopeptides | Vancomycin | 1 (0.3) |

| Teicoplanin | 1 (0.3) | |

| Quinolones | Ciprofloxacin | 27 (8.2) |

| Lincosamide | Clindamycin | 26 (7.9) |

| Macrolide | Erythromycin | 112 (34) |

| Nitrofuran | Nitrofurantoin | 11 (3.3) |

| Aminoglycoside | Gentamicin | 54 (16.4) |

| Oxazolidinone | Linezolid | – |

| Monooxycarbolic acid | Mupirocin | 5 (1.5) |

| streptogramin | Quinupristin/Dalfopristin | 4 (1.2) |

| Ansamycin | Rifampicin | 5 (1.5) |

| Sulfonamides | Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole | 4 (1.2) |

| Tetracycline | Tetracycline | 54 (16.4) |

| Ketolide | Telithromycin | 30 (9.1) |

| Glycylcycline | Tigecycline | – |

| Positive | ||

|---|---|---|

| Lincosamide | Inducible Clindamycin Resistance | 92 (28) |

| Cephams | Cefoxitin Screen | 114 (34.7) |

Fig. 2.

The resistance of 19 antibiotic agent following enterotoxin types. The percentage of isolates was determined by containing each antibiotic agent in isolates. (A). GIMNO type (Type I), (B) AHKQ type (Type II), (C) A type (Type III), (D) The enterotoxin genotypic and phenotypic trends year by year (2007–2022)

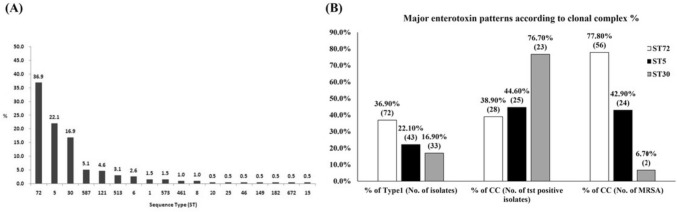

MLST analyses of the Type I S. aureus isolates

To characterize the bacterial lineage, 195 Type I S. aureus isolates were identified using MLST analysis. MLST is a useful tool for identifying bacterial lineages. As shown in Fig. 3(A), the MLST of 195 Type I strains represented 18 different MLST STs, which are well-known STs (Supplementary Data Table S3). The most frequent sequence type was ST72 (36.9%), followed by ST5 (22.1%) and ST30 (16.9%). ST72 strains represented 77.8% of MRSA higher than other CCs and included a lot of GIMNO gene patterns. ST5 strains comprised 42.9% of MRSA, 44.6% of TSST-1-positive strain, and included a lot of CGILMNO gene patterns. Interestingly, CC30 had lower MRSA occurrence (6.7%) and higher TSST-1-positive strain (76.7%) than other STs. The major enterotoxin pattern in CC30 was AGINO (n = 23) (Fig. 3(B)).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of sequence types (STs) in Type Ι group and major enterotoxin patterns according to clonal complex. (A) Percentage of sequence types (STs) in Type Ι group, (B) Major enterotoxin patterns according to clonal complex

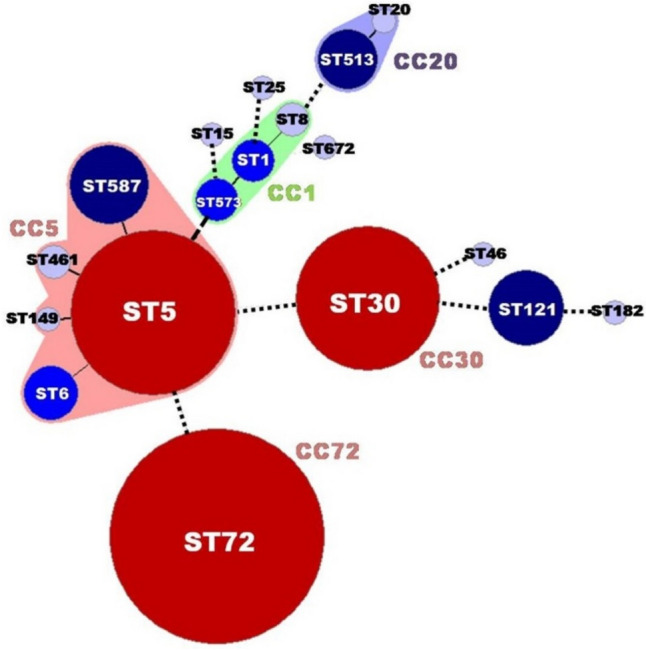

Phylogenetic trees of the STs analyzed above were generated and compared with those of the housekeeping gene profile similarity. As shown in Fig. 4, phylogenetic analysis indicated that three major CCs (CC72, CC30, and CC5) were found in Type I strains; the CCs had very little genetic relationship. We observed that the major ST types in Type I strains were ST72, ST5, and ST30 (Gergova et al., 2022). Previous studies have reported that ST72, ST5, and ST30 are common sequence types in Korea (Cha et al., 2006; Hwang et al., 2013; Park et al., 2019) and that most MRSA isolates are ST72 (Batool et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2011). In conclusion, we identified a major egc-type S. aureus isolated from patients with diarrhea in Korea. egc-positive strains originating from patients with diarrhea accounted for half of the total and had a high MRSA ratio. These results were the first reported for S. aureus strains in Korea, which significantly expanded S. aureus genotype information for the surveillance of pathogenic S. aureus. Furthermore, vaccine development associated with egc-related superantigens and MRSA is required to prevent pathogenic S. aureus.

Fig. 4.

MLST dendrogram of 195 egc-positive S. aureus isolates

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from Sun Moon University (2018-01810001).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jung-Beom Kim, Email: okjbkim@scnu.ac.kr.

Seung-Hak Cho, Email: skcho7824@naver.com.

References

- Algammal AM, Hetta HF, Elkelish A, Alkhalifah DH, Hozzein WN, Batiha GE, El Nahhas N, Mabrok MA. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): one health perspective approach to the bacterium epidemiology, virulence factors, antibiotic-resistance, and zoonotic impact. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020;13:3255–3265. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S272733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PC. Microbiology of antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2007;45:165–170. doi: 10.1086/519474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argudín MÁ, Mendoza MC, Rodicio MR. Food poisoning and Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins. Toxins. 2010;2:1751–1774. doi: 10.3390/toxins2071751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora S, Li X, Hillhouse A, Konganti K, Little SV, Lawhon SD, Threadgill D, Shelburne S, Hook M. Staphylococcus epidermidis MSCRAMM SesJ is encoded in composite islands. mBio. 2020;11(1):e02911–e2919. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02911-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban N, Rasooly A. Staphylococcal enterotoxins. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2000;61:1–10. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batool N, Shamim A, Chaurasia AK, Kim KK. Genome-wide analysis of Staphylococcus aureus sequence type 72 isolates provides insights into resistance against antimicrobial agents and virulence potential. Front. Microbiol. 2021;11:613800. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.613800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi DM, Gallina S, Bellio A, Chiesa F, Civera T, Decastelli L. Enterotoxin gene profiles of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from milk and dairy products in Italy. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2013;58:190–196. doi: 10.1111/lam.12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervera-Alamar M, Guzmán-Markevitch K, Žiemytė M, Ortí L, Bernabé-Quispe P, Pineda-Lucena A, Pemán J, Tormo-Mas MÁ. Mobilisation mechanism of pathogenicity islands by endogenous phages in Staphylococcus aureus clinical strains. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:16742. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34918-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha JO, Lee JK, Jung YH, Yoo JI, Park YK, Kim BS, Lee YS. Molecular analysis of Staphylococcus aureus isolates associated with staphylococcal food poisoning in South Korea. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006;101:864–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang YC, Chang LT, Lin CW, Yang CY, Tsen HY. The detection of staphylococcal enterotoxins K, L, and M and survey of staphylococcal enterotoxin types in Staphylococcus aureus isolates from food poisoning cases. J. Food Prot. 2006;5:1072–1079. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-69.5.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YW, Kotzin B, Herron L, Callahan J, Marrack P, Kappler J. Interaction of Staphylococcus aureus toxin “superantigens” with human T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:8941–8945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinges MM, Orwin PM, Schlievert PM. Exotoxins of Staphylococcus aureus. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2000;13:16–34. doi: 10.1128/CMR.13.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright MC, Robinson DA, Randle G, Feil EJ, Grundmann H, Spratt BG. The evolutionary history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99:7687–7692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122108599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- G Abril A, G Villa T, Barros-Velázquez J, Cañas B, Sánchez-Pérez A, Calo-Mata P, Carrera M. Staphylococcus aureus exotoxins and their detection in the dairy industry and mastitis. Toxins (Basel). 12: 537 (2020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gan T, Shu G, Fu H, Yan Q, Zhang W, Tang H, Yin L, Zhao L, Lin J. Antimicrobial resistance and genotyping of Staphylococcus aureus obtained from food animals in Sichuan Province, China. BMC Veterinary Research. 2021;17:177. doi: 10.1186/s12917-021-02884-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergova R, Tsitou VM, Dimov SG, Boyanova L, Mihova K, Strateva T, Gergova I, Markovska R. Molecular epidemiology, virulence and antimicrobial resistance of Bulgarian methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2022;69(3):193–200. doi: 10.1556/030.2022.01766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gherardi G. Staphylococcus aureus infection: pathogenesis and antimicrobial resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24(9):8182. doi: 10.3390/ijms24098182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Song G, Sun M, Wang J, Wang Y. Prevalence and therapies of antibiotic-resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020;10:107. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazen TH, Pan L, Gu JD, Sobecky PA. The contribution of mobile genetic elements to the evolution and ecology of Vibrios. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2010;74(3):485–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennekinne J-A, De Buyser M-L, Dragacci S. Staphylococcus aureus and its food poisoning toxins: characterization and outbreak investigation. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2012;36:815–836. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtfreter S, Bauer K, Thomas D. egc-encoded superantigens from Staphylococcus aureus are neutralized by human sera much less efficiently than are classical staphylococcal enterotoxins or toxic shock. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:4061–4071. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.4061-4071.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D-L, Li S, Fang R, Ono HK. Update on molecular diversity and multipathogenicity of staphylococcal superantigen toxins. Animal Disease. 2021;1:7. doi: 10.1186/s44149-021-00007-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Yang X, Li J, Lv N, Liu F, Wu J, Lin IY, Wu N, Weimer BC, Gao GF, Liu Y, Zhu B. The bacterial mobile resistome transfer network connecting the animal and human microbiomes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016;82(22):6672–6681. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01802-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang J-W, Joo E-J, Ha JM, Lee W, Kim E, Yune S, Chung DR, Jeon K. Community-acquired necrotizing pneumonia caused by ST72-SCCmec type IV-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Korea. Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases. 2013;75:75–78. doi: 10.4046/trd.2013.75.2.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SY, Kim SH, Jang EJ, Kwon NH, Park YK, Koo HC, Jung WK, Kim JM, Park YH. Novel multiplex PCR for the detection of the Staphylococcus aureus superantigen and its application to raw meat isolates in Korea. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2007;117:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johler S, Giannini P, Jermini M, Hummerjohann J, Baumgartner A, Stephan R. Further evidence for staphylococcal food poisoning outbreaks caused by egc-encoded enterotoxins. Toxins (basel) 2015;7:997–1004. doi: 10.3390/toxins7030997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CN, Sheriff EK, Duerkop BA, Chatterjee A. Let me upgrade you: impact of mobile genetic elements on Enterococcal adaptation and evolution. Journal of Bacteriology. 2021;203(21):e0017721. doi: 10.1128/JB.00177-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ES, Lee HJ, Chung G-T, Lee Y-S, Shin D-H, Jung S-I, Song K-H, Park W-B, Kim NJ, Park KU, Kim E-C, Oh M-D, Kim HB. Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates in Korea. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2011;49:1979–1982. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00098-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim N, Cha I, Kim J, Chung GT, Kang Y, Hong S. The prevalence and characteristics of bacteria causing acute diarrhea in Korea, 2012. The Korean Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2013;16:174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda M, Ohta T, Uchiyama I, Baba T, Yuzawa H, Kobayashi I, Cui L, Oguchi A, Aoki K, Nagai Y, Lian J, Ito T, Kanamori M, Matsumaru H, Maruyama A, Murakami H, Hosoyama A, Mizutani-Ui Y, Takahashi NK, Sawano T, Inoue R, Kaito C, Sekimizu K, Hirakawa H, Kuhara S, Goto S, Yabuzaki J, Kanehisa M, Yamashita A, Oshima K, Furuya K, Yoshino C, Shiba T, Hattori M, Ogasawara N, Hayashi H, Hiramatsu K. Whole genome sequencing of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2001;357:1225–1240. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladhani S, Joannou CL, Lochrie DP, Evans RW, Poston SM. Clinical, microbial, and biochemical aspects of the exfoliative toxins causing staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1999;12:224–242. doi: 10.1128/CMR.12.2.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Huang T, Xu K, Li C, Li Y. Molecular characteristics and virulence gene profiles of Staphylococcus aureus isolates in Hainan, China. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2019;19(1):873. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4547-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Tang Y, Jiang Z, Wang Z, Li Q, Jiao X. Molecular characterization of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus from the intestinal tracts of adult patients in China. Pathogens. 2022;11(9):978. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11090978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim KL, Khor WC, Ong KH, Timothy L, Aung KT. Occurrence and patterns of enterotoxin genes, spa types and antimicrobial resistance patterns in Staphylococcus aureus in food and food contact surfaces in Singapore. Microorganisms. 2023;11(7):1785. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11071785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Chen D, Peters BM, Li L, Li B, Xu Z, Shirliff ME. Staphylococcal chromosomal cassettes mec (SCCmec): a mobile genetic element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microbial pathogenesis. 2016;101:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowy F. Antimicrobial resistance: the example of Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;111:1265–1273. doi: 10.1172/JCI18535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado V, Pardo L, Cuello D, Giudice G, Luna PC, Varela G, Camou T, Schelotto F. Presence of genes encoding enterotoxins in Staphylococcus aureus isolates recovered from food, food establishment surfaces and cases of foodborne diseases. Revista Tropical Medicine Institute of São Paulo. 2020;62:e5. doi: 10.1590/s1678-9946202062005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malachowa N, DeLeo FR. Mobile genetic elements of Staphylococcus aureus. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2010;67:3057–3071. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0389-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick JK, Yarwood JM, Schlievert PM. Toxic shock syndrome and bacterial superantigens: an update. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2001;55:77–104. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mempel M, Lina G, Hojka M, Schnopp C, Seidl H-P, Schäfer T, Ring J, Vandenesch F, Abeck D. High prevalence of superantigens associated with the egc locus in Staphylococcus aureus isolates from patients with atopic eczema. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious. 2003;22:306–309. doi: 10.1007/s10096-003-0928-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullany P, Allan E, Roberts AP. Mobile genetic elements in Clostridium difficile and their role in genome function. Res. Microbiol. 2015;166:361–367. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normanno G, La Salandra G, Dambrosio A, Quaglia NC, Corrente M, Parisi A, Santagada G, Firinu A, Crisetti E, Celano GV. Occurrence, characterization and antimicrobial resistance of enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus isolated from meat and dairy products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007;115:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick RP, Ram G. Staphylococcal pathogenicity islands—movers and shakers in the genomic firmament. Current Opinion in Microbiology . 2017;38:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick R, Subedi A. The SaPIs: mobile pathogenicity islands of Staphylococcus. Chem. Immunol. Allergy. 2007;93:42–57. doi: 10.1159/000100857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogonowska P, Gilaberte Y, Barańska-Rybak W, Nakonieczna J. colonization with Staphylococcus aureus in atopic dermatitis patients: attempts to reveal the unknown. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2020;11:567090. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.567090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono HK, Hirose S, Naito I, Satoo Y, Asano K, Hu DL, Omoe K, Nakane A. The emetic activity of staphylococcal enterotoxins, SEK, SEL, SEM, SEN and SEO in a small emetic animal model, the house musk shrew. Microbiology and Immunology. 2017;61:12–16. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SG, Lee HS, Park JY, Lee H. Molecular epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus in skin and soft tissue infections and bone and joint infections in Korean children. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2019;34(49):e315. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2019.34.e315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinchuk IV, Beswick EJ, Reyes VE. Staphylococcal enterotoxins. Toxins. 2010;2:2177–2197. doi: 10.3390/toxins2082177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Principato MA, Qian B-F. Staphylococcal enterotoxins in the Etiopathogenesis of mucosal autoimmunity within the gastrointestinal tract. Toxins (basel). 2014;6(5):1471–1489. doi: 10.3390/toxins6051471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmi AH, Ahmed EF, Darwish AMA, Gad GFM. Virulence genes distributed among Staphylococcus aureus causing wound infections and their correlation to antibiotic resistance. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022;22:652. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07624-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosec J, Gigaud O. Staphylococcal enterotoxin genes of classical and new types detected by PCR in France. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002;77:61–70. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo E. Causes of acute gastroenteritis in Korean children between 2004 and 2019. Clinical and Experimental Pediatrics. 2021;64(6):260–268. doi: 10.3345/cep.2020.01256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saba CKS, Naa-Inour F, Kpordze SW. Antibiotic resistance pattern of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli from mobile phones of healthcare workers in public hospitals in Ghana. Pan African Medical Journal. 2022;41:259. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2022.41.259.29281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado-Pabón W, Tran PM. Chapter 25—Staphylococcal food poisoning. In: Morris Jr. JG, Vugia DJJ, editors. Foodborne infections and intoxications. 5. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2021. pp. 417–430. [Google Scholar]

- Schwendimann L, Merda D, Berger T, Denayer S, Feraudet-Tarisse C, Kläui AJ, Messio S, Mistou MY, Nia Y, Hennekinne JA, Graber HU. Staphylococcal enterotoxin gene cluster: prediction of enterotoxin (SEG and SEI) production and of the source of food poisoning on the basis of v Saβ typing. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2021;87(5):e0266220. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02662-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu A, Fujita M, Igarashi H. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus coagulase type VII isolates from Staphylococcal food poisoning outbreaks (1980–1995) in Tokyo, Japan, by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2000;38:3746–3749. doi: 10.1128/JCM.38.10.3746-3749.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tansirichaiya S, Goodman RN, Guo X, Bulgasim I, Samuelsen Ø, Al-Haroni M, Roberts AP. Intracellular transposition and capture of mobile genetic elements following intercellular conjugation of multidrug resistance conjugative plasmids from clinical Enterobacteriaceae isolates. Microbiology Spectrum. 2022;10(1):e0214021. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02140-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmonsa CM, Shaziba SUA, Katza LA. Epigenetic influences of mobile genetic elements on ciliate genome architecture and evolution. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 2022;69(5):e12891. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viçosa GN, Le Loir A, Le Loir Y, de Carvalho AF, Nero LA. egc characterization of enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus isolates obtained from raw milk and cheese. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013;165:227–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuke SO, Omoe K, Aikawa Y, Kano M, Ono HK, Hu DL, Nakane A, Sugai M. Investigation of Staphylococcus aureus positive for Staphylococcal enterotoxin S and T genes. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. 2021;83(7):1120–1127. doi: 10.1292/jvms.20-0662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.