Key Points

Question

Is acupuncture an effective treatment to reduce symptoms of radiation-induced xerostomia once it becomes chronic after the completion of radiotherapy for head and neck cancer?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial including 258 patients with head and neck cancer, true acupuncture was effective at improving symptoms of radiation-induced xerostomia and overall quality of life (QOL) compared with standard oral hygiene. Although there was some suggestion of a sham effect, the benefits of sham treatment were minimal and not associated with improvements in overall QOL.

Meaning

The findings from this trial suggest that use of real acupuncture reduces chronic radiation-induced xerostomia and leads to improvement in QOL.

Abstract

Importance

Patients with head and neck cancer who undergo radiotherapy can develop chronic radiation-induced xerostomia. Prior acupuncture studies were single center and rated as having high risk of bias, making it difficult to know the benefits of acupuncture for treating radiation-induced xerostomia.

Objective

To compare true acupuncture (TA), sham acupuncture (SA), and standard oral hygiene (SOH) for treating radiation-induced xerostomia.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A randomized, blinded, 3-arm, placebo-controlled trial was conducted between July 29, 2013, and June 9, 2021. Data analysis was performed from March 9, 2022, through May 17, 2023. Patients reporting grade 2 or 3 radiation-induced xerostomia 12 months or more postradiotherapy for head and neck cancer were recruited from community-based cancer centers across the US that were part of the Wake Forest National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program Research Base. Participants had received bilateral radiotherapy with no history of xerostomia.

Interventions

Participants received SOH and were randomized to TA, SA, or SOH only. Participants in the TA and SA cohorts were treated 2 times per week for 4 weeks. Those experiencing a minor response received another 4 weeks of treatment.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Patient-reported outcomes for xerostomia (Xerostomia Questionnaire, primary outcome) and quality of life (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General) were collected at baseline, 4 (primary time point), 8, 12, and 26 weeks. All analyses were intention to treat.

Results

A total of 258 patients (201 men [77.9%]; mean [SD] age, 65.0 [9.16] years), participated from 33 sites across 13 states. Overall, 86 patients were assigned to each study arm. Mean (SD) years from diagnosis was 4.21 (3.74) years, 67.1% (n = 173) had stage IV disease. At week 4, Xerostomia Questionnaire scores revealed significant between-group differences, with lower Xerostomia Questionnaire scores with TA vs SOH (TA: 50.6; SOH: 57.3; difference, −6.67; 95% CI, −11.08 to −2.27; P = .003), and differences between TA and SA (TA: 50.6; SA: 55.0; difference, −4.41; 95% CI, −8.62 to −0.19; P = .04) yet did not reach statistical significance after adjustment for multiple comparisons. There was no significant difference between SA and SOH. Group differences in Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General scores revealed statistically significant group differences at week 4, with higher scores with TA vs SOH (TA: 101.6; SOH: 97.7; difference, 3.91; 95% CI, 1.43-6.38; P = .002) and at week 12, with higher scores with TA vs SA (TA: 102.1; SA: 98.4; difference, 3.64; 95% CI, 1.10-6.18; P = .005) and TA vs SOH (TA: 102.1; SOH: 97.4; difference, 4.61; 95% CI, 1.99-7.23; P = .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this trial suggest that TA was more effective in treating chronic radiation-induced xerostomia 1 or more years after the end of radiotherapy than SA or SOH.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02589938

This randomized clinical trial evaluates the use of acupuncture in the treatment of xerostomia in patients with head and neck cancer who received radiotherapy.

Introduction

By the end of radiotherapy, more than 50% of patients with head and neck cancer experience hyposalivation with the subjective sensation termed radiation-induced xerostomia (RIX)1,2,3; its influence on quality of life among patients with cancer is well established.4,5 Patients experience decreased or total lack of saliva secretion leading to pain and difficulty speaking, chewing, swallowing, and sleeping, as well as taste aberration, insufficient nutritional intake, weight loss, caries, loss/deterioration of dentition, and gingivitis.6 Despite some success with cytoprotection (eg, amifostine)7 and physical techniques designed to reduce salivary gland exposure during radiotherapy,8 acute and chronic RIX still occur9 with no reliable treatment.10

A number of randomized and observational studies have found acupuncture can stimulate saliva flow and improve patient-reported outcomes among participants with RIX.11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 These studies were conducted by different investigators, in multiple countries, using different acupuncture points, yet all produced similar positive results. One study even demonstrated long-term effects (>3 years) on saliva production,13 and several studies14,21,23,24 found that acupuncture can prevent RIX when given concurrently with radiotherapy. However, prior trials lacked blinding or sham controls and/or had small sample size.

A large, 2-center (US and China), 3-arm, sham-controlled, phase 3 clinical trial of acupuncture to prevent RIX when provided concurrently with radiotherapy was conducted.17 This trial found that xerostomia was significantly lower in the true acupuncture (TA) group compared with standard oral hygiene (SOH) and marginally lower than a sham acupuncture (SA) group. To our knowledge, there have been no phase 3, multicenter trials to examine the effects of acupuncture to treat chronic RIX. The present randomized, phase 3, blinded, sham-controlled, multicenter trial examined whether TA could symptomatically improve RIX in patients with head and neck cancer with moderate or severe RIX.25

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The study was launched July 2013 under the oversight of the MD Anderson Community Clinical Oncology Program Research Base. Twenty-eight participants were recruited across multiple centers from July 29, 2013, to August 20, 2015. The trial was subsequently transferred to the Wake Forest National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) Research Base where the trial continued from April 7, 2016, through June 9, 2021 (protocol available in Supplement 1). The trial was approved by the institutional review boards of the Wake Forest University School of Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and each NCORP site where participants were enrolled and provided informed consent; they did not receive financial compensation. The study follows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline for RCTs.

Eligibility criteria included (1) diagnosis of head and neck cancer; (2) aged 18 years or older; (3) ability to read, write, and understand English; (4) received only first-line bilateral external-beam radiotherapy with curative intent 12 or more months prior to enrollment; (5) grade 2 or 3 xerostomia per Radiation Therapy Oncology Group scale known to be due to radiotherapy; (6) had anatomically intact parotid glands and at least 1 submandibular gland; (7) had never received acupuncture for xerostomia; and (8) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 2. Exclusion criteria included (1) history of xerostomia, Sjögren syndrome, or other illness known to affect salivation prior to radiotherapy; (2) suspected or known closure of salivary gland ducts on either side; (3) currently receiving or planning to receive other xerostomia treatment; (4) receiving (past 30 days) or planning to receive any investigational drug for any condition; (5) active systemic infection or skin infection at/near acupuncture sites; and (6) receiving chemotherapy or any drug known to affect xerostomia during the study period. All treatments known to affect salivation had to be stopped 14 days or more prior to enrollment.

Procedures

Participants were assessed for eligibility and provided informed consent. At baseline, participants received SOH instructions, completed patient-reported outcome forms, and provided sialometry samples. Participants were randomized to 1 of 3 treatment groups: (1) TA, (2) SA, or (3) SOH. Participants in the acupuncture groups had 2 treatments per week for 4 weeks (standard for a course of acupuncture) and received SOH instructions. Patients completed questionnaires and underwent sialometry testing again at week 4; if participants in the TA or SA cohorts had a minor response (10- to 19-point Xerostomia Questionnaire [XQ] decrease from baseline), they continued their assigned acupuncture treatment twice per week for another 4 weeks. Patients who had no response, partial response, or complete response received no further acupuncture treatment and simply completed the remaining assessments. This procedure was used to better reflect acupuncture clinical practice and determine the persistence of improvement without further treatment for those responding. Patients subsequently completed patient-reported outcomes and sialometry testing at weeks 8, 12, and 26. Patients in the SOH group or SA group were offered 3 sessions of TA at no cost post study completion.

Randomization and Blinding

Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to TA, SA, or SOH, using adaptive minimization randomization23 stratified by cancer stage, age, sex, time since radiotherapy, mean parotid radiotherapy doses received (left and right side calculated separately, balanced between groups), and baseline XQ scores. To avoid risk of unblinding between TA and SA, we used a previously successful procedure17 in which patients were told the study was examining 2 forms of acupuncture compared with a usual care group. As patients in both groups received real needles in real acupoints, this study description is not deception. Participants and site staff were blinded to TA and SA group assignment.

Acupuncture Treatment

Participants in both groups were placed in a comfortable supine position. A total of 14 points, body and ear, were used for both groups. All sites were applied for 20 minutes.

True Acupuncture

Points were selected based on (1) previously published studies reporting xerostomia reversal,17,18,19,24 (2) classical traditional Chinese medicine theory,26,27 and (3) current understanding of anatomical locations and neurovascular tissues associated with salivary function. Acupuncture points were at 3 sites on each ear (Shenmen, point 0, salivary gland 2-prime19,20), a site on the chin (CV24), a site on each forearm (LU7), a site on each hand (LI 1-prime19,20), and a site on each leg (K6) with 1 placebo needle at GB32 for a total of 14 sites. For body points, standardized techniques for location were used.

Sham Acupuncture

Well-designed clinical acupuncture trials require a sham procedure that is indistinguishable from real treatment, yet inactive. Although no standard has been established for placebo controls in acupuncture trials, nonpenetrating needles placed at inactive points are recommended. A validated, nonpenetrating, telescoping needle with a separate device that attaches it to the skin was used.28,29 Although needling anywhere on the ear may cause a physiologic response, prior research has identified 3 nonactive points on the helix of the ear.30,31,32

The SA followed the same schedule as TA. Three fixed points were used on each ear located in the middle of the ear helix and are known as helix 2, helix 3, and helix 4.33 The sham procedure for body points included sham needles at inactive points: sham location 1: 0.5 cun (a body inch used in traditional Chinese medicine to locate acupoints) below and 0.5 cun lateral to CV 24 on the chin; sham location 2: 0.5 cun radial and 0.5 cun proximal to Sanjiao 6 between Sanjiao and LI channels (bilateral upper extremity); sham location 3: 2 cun above sham location 2 between Sanjiao and LI channels and between LI7 and LI8 (bilateral upper extremity); and sham location 4: 1.0 cun below and 0.5 cun lateral to ST36, between ST and GB channels (bilateral lower extremity) (in traditional Chinese medicine, a cun is an anatomical measure based on the patient’s own body and equals the width of the thumb at the knuckle).26 One real acupuncture needle was inserted at GB32, not indicated for dry mouth, to achieve de qi sensation.

Needles

The acupuncture needles (Seirin Corp, Kyoto, Japan) used in the ear and LI 1-prime were 40 gauge ×15 mm, and the needles used for all other body points were 36 gauge ×30 mm, conforming to the requirements of the ISO 9002, EN46002, and CE.

Acupuncture was performed by a certified acupuncturist (including M.K.G., J.K.M., and 50 other acupuncturists) designated by each site. Study acupuncturists met state licensing requirements, passed the National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine examination (if required by state regulations), and had at least 1 year of clinical acupuncture experience. Group or 1-on-1 training sessions were conducted for each acupuncturist.

Standard Oral Hygiene

All patients received SOH information: instructions regarding mouth rinses, lip balms, mild fluoride toothpaste, importance of adequate oral hydration, and other standard advice. All participants continued SOH throughout the study.

Outcomes

The subjective sensation of dry mouth is not associated with objective saliva flow rate; the US Food and Drug Administration requires patient-reported outcome measures for assessing xerostomia interventions. Patient-reported outcomes including the XQ (primary outcome) and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General [FACT-G]; secondary outcome) were completed at baseline and weeks 4, 8, 12, and 26. The Acupuncture Expectancy Scale was collected at baseline for all participants and at week 4 in the TA and SA groups only.

The validated, 8-item XQ is the prime standard measure for xerostomia.1,2 Items are summed and transformed linearly to produce a summary score from 0 to 100. Higher scores represent more xerostomia, with a 10-point difference or change considered clinically significant.

The FACT-G quality-of-life instrument is a commonly used questionnaire.34 The total score is reported, with higher scores representing better quality of life.

The 4-item Acupuncture Expectancy Scale was used to ensure there were no baseline group differences in expectations of benefit of acupuncture on dry mouth and to assess aspects of blinding after the first 4 weeks of acupuncture for the TA and SA groups.35 Higher scores represent greater expectancy that acupuncture will help with dry mouth.

Response Assessment

Response was assessed by examining change in XQ scores from baseline to weeks 4, 8, 12, and 26. Response categories included no response (any increase in XQ scores or decrease of <10 points), minor response (10- to 19-point decrease in XQ score), partial response (≥20-point decrease in XQ score), and complete response (complete resolution of xerostomia, with XQ = 0).1,2

Adverse events were assessed at each time point using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0.36 Only grade 1 to 3 adverse events (as acupuncture is not a life-threatening treatment) that were definitely related, probably related, or possibly related to the intervention were reported.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed from March 9, 2022, to May 17, 2023. The primary end point was XQ at week 4. The study was powered to detect a difference of 10 points, accepted as clinically significant on the XQ1,2 and on a 0 to 100 scale,37 with an assumed SD of 16 between each pair of groups on XQ and required 64 participants per group (N = 192), assuming a t test with a 2-sided significance level of P = .0167 (adjusting for 3 comparisons) and 84% power. To allow for a dropout rate of up to 20%, 240 patients were recruited.

Primary analyses were 2-sided t tests at week 4 comparing all 3 groups. Repeated measures analysis of covariance models were also conducted to estimate differences in each outcome, adjusting for baseline value, group, time, and group by time interaction, assuming an unstructured covariance. Clinical response differences in XQ scores (partial responses or clinically significant xerostomia defined as XQ >30) were examined using χ2 tests. Adverse events were summarized by group. All analyses were intention to treat. Secondary sensitivity analyses to account for missing data using multiple imputation for outcomes (XQ, FACT-G, and Acupuncture Expectancy Scale) were performed using monotone regression with 1000 iterations. Age, sex, race and ethnicity, and job status were used for the imputation. Imputation values were restricted to a minimum and maximum range dictated by each outcome. Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).38

Results

Of the 258 participants who consented and were randomized, mean (SD) age was 65.0 (9.16) years; median age was 65.2 (IQR, 21.1-84.7) years, 77.9% (n = 201) were men and 22.1% (n = 57) were women, 5.0% (n = 13) were Asian, 6.2% (n = 16) were Hispanic or Latino, and 88.8% (n = 229) were non-Hispanic White (self-reported race and ethnicity), and 64.3% (n = 166) were married. A total of 97.5% (n = 234) had grade 2 xerostomia and were a mean (SD) of 4.21 (3.74) years from diagnosis (range, 1.17-18.42 years); 67.1% (n = 173) had stage IV cancer. Participants were enrolled from 33 NCORP practices over 12 states in the continental US (California, Illinois, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, Ohio, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Washington) and Hawaii. There were no significant group differences in demographic or medical characteristics (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1. Baseline Demographic, Radiation, and Clinical Characteristics by Treatment Groupa.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined (N = 258) | TA (n = 86) | SA (n = 86) | SOH (n = 86) | |

| Age at enrollment, mean (SD), y | 65.0 (9.2) | 65.0 (8.6) | 64.4 (9.9) | 65.6 (9.0) |

| Age stratification, y | ||||

| <40 | 2 (0.8) | 0 | 2 (2.3) | 0 |

| 41-55 | 43 (16.7) | 14 (16.3) | 13 (15.1) | 16 (18.6) |

| 56-70 | 143 (55.4) | 50 (58.1) | 47 (54.7) | 46 (53.5) |

| >70 | 70 (27.1) | 22 (25.6) | 24 (27.9) | 24 (27.9) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 26.7 (5.5) | 26.0 (4.3) | 26.5 (5.7) | 27.6 (6.2) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 201 (77.9) | 68 (79.1) | 67 (77.9) | 66 (76.7) |

| Female | 57 (22.1) | 18 (20.9) | 19 (22.1) | 20 (23.3) |

| Race and ethnicityb | ||||

| African American | 9 (3.5) | 2 (2.3) | 5 (5.8) | 2 (2.3) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (0.8) | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 1 (1.2) |

| Asian | 13 (5.0) | 4 (4.7) | 2 (2.3) | 7 (8.1) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 16 (6.2) | 3 (3.5) | 7 (8.1) | 6 (7.0) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.2) |

| White | 229 (88.8) | 77 (89.5) | 77 (89.5) | 75 (87.2) |

| >1 Race | 4 (1.6) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (2.3) | 0 |

| Insurance | ||||

| Medicare | 101 (39.2) | 32 (37.2) | 35 (40.7) | 34 (39.5) |

| Medicaid | 15 (5.8) | 2 (2.3) | 5 (5.8) | 8 (9.3) |

| Private | 154 (59.7) | 56 (65.1) | 51 (59.3) | 47 (54.7) |

| None | 13 (5.0) | 4 (4.7) | 5 (5.8) | 4 (4.7) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single (never married) | 18 (7.0) | 4 (4.7) | 10 (11.6) | 4 (4.7) |

| Married/living like married | 166 (64.3) | 61 (70.9) | 48 (55.8) | 57 (66.3) |

| Separated/divorced | 34 (13.2) | 8 (9.3) | 14 (16.3) | 12 (13.9) |

| Widowed | 11 (4.3) | 4 (4.7) | 4 (4.7) | 3 (3.5) |

| Unknown | 29 (11.2) | 9 (10.4) | 10 (11.6) | 10 (11.6) |

| Educational level | ||||

| High school | 55 (21.3) | 18 (20.9) | 17 (19.8) | 20 (23.3) |

| Some college/training | 88 (34.1) | 27 (31.4) | 30 (34.9) | 31 (36.0) |

| College degree (BA/BS) | 51 (19.8) | 20 (23.3) | 16 (18.6) | 15 (17.5) |

| Advanced degree | 34 (13.2) | 11 (12.8) | 13 (15.1) | 10 (11.6) |

| Unknown | 30 (11.6) | 10 (11.6) | 10 (11.6) | 10 (11.6) |

| Job status | ||||

| Retired | 95 (36.8) | 37 (43.0) | 28 (32.6) | 30 (34.9) |

| Employed (full time/part time) | 86 (33.3) | 29 (33.7) | 26 (30.2) | 31 (36.0) |

| Disabled (unable to work) | 22 (8.6) | 5 (5.8) | 7 (8.1) | 10 (11.6) |

| Other/unknown | 55 (21.3) | 15 (17.5) | 25 (29.1) | 15 (17.5) |

| RTOG scale grade | ||||

| Grade 2 | 234 (97.5) | 77 (96.3) | 80 (98.8) | 77 (97.5) |

| Grade 3 | 6 (2.5) | 3 (3.8) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.5) |

| Baseline XQ scores | ||||

| <30 | 10 (3.9) | 4 (4.7) | 3 (3.5) | 3 (3.5) |

| 30-39 | 19 (7.4) | 7 (8.1) | 6 (7.0) | 6 (7.0) |

| 40-49 | 37 (14.3) | 11 (12.8) | 13 (15.1) | 13 (15.1) |

| ≥50 | 192 (74.4) | 64 (74.4) | 64 (74.4) | 64 (74.4) |

| Baseline AES score | 12.1 (4.0) | 11.9 (4.1) | 11.7 (3.7) | 12.7 (4.3) |

| ECOG score | ||||

| 0 | 173 (68.9) | 56 (66.7) | 61 (72.6) | 56 (67.5) |

| 1 | 75 (29.9) | 26 (31.0) | 23 (27.4) | 26 (31.3) |

| 2 | 3 (1.2) | 2 (2.4) | 0 | 1 (1.2) |

| Stage of disease | ||||

| I | 23 (8.9) | 8 (9.3) | 7 (8.1) | 8 (9.3) |

| II | 21 (8.1) | 7 (8.1) | 8 (9.3) | 6 (7.0) |

| III | 41 (15.9) | 13 (15.1) | 13 (15.1) | 15 (17.4) |

| IV | 173 (67.1) | 58 (67.4) | 58 (67.4) | 57 (66.3) |

| Left mean parotid radiotherapy doses, Gy | ||||

| <10 | 5 (1.9) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | 3 (3.5) |

| 10 to <20 | 25 (9.7) | 9 (10.5) | 9 (10.5) | 7 (8.1) |

| 20 to <30 | 110 (42.6) | 35 (40.7) | 38 (44.2) | 37 (43.0) |

| 30 to <40 | 50 (19.4) | 17 (19.8) | 16 (18.6) | 17 (19.8) |

| 40 to <50 | 21 (8.1) | 7 (8.1) | 7 (8.1) | 7 (8.1) |

| 50 to <60 | 18 (7.0) | 6 (7.0) | 6 (7.0) | 6 (7.0) |

| ≥60 | 29 (11.2) | 11 (12.8) | 9 (10.5) | 9 (10.5) |

| Right mean parotid radiotherapy doses, Gy | ||||

| <10 | 11 (4.3) | 3 (3.5) | 4 (4.7) | 4 (4.7) |

| 10 to <20 | 26 (10.1) | 9 (10.5) | 9 (10.5) | 8 (9.3) |

| 20 to <30 | 104 (40.3) | 35 (40.7) | 34 (39.5) | 35 (40.7) |

| 30 to <40 | 49 (19.0) | 17 (19.8) | 15 (17.4) | 17 (19.8) |

| 40 to <50 | 24 (9.3) | 7 (8.1) | 9 (10.5) | 8 (9.3) |

| 50 to <60 | 26 (10.1) | 9 (10.5) | 8 (9.3) | 9 (10.5) |

| ≥60 | 18 (7.0) | 6 (7.0) | 7 (8.1) | 5 (5.8) |

Abbreviations: AES, Acupuncture Expectancy Scale; BA, bachelor of arts; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); BS, bachelor of science; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; RTOG, Radiation Therapy Oncology Group; SA, sham acupuncture; SOH, standard oral hygiene; TA, true acupuncture; XQ, Xerostomia Questionnaire.

There were no significant between-group differences.

Race and ethnicity were self-reported.

Table 2. Least Squares Mean Estimates With 95% CI for Each Treatment Group by Timea.

| Time week | LS mean (95% CI) | Pairwise comparisons | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TA | SA | SOH | TA v SOH | SA v SOH | TA v SA | |||||

| LS means difference (95% CI) | P value | LS means difference (95% CI) | P value | LS means difference (95% CI) | P value | |||||

| XQ score | ||||||||||

| 4 | 50.59 (47.67 to 53.50) | 54.99 (51.95 to 58.03) | 57.26 (53.95 to 60.57) | −6.67 (−11.08 to −2.27) | .003 | −2.27 (−6.76 to 2.23) | .32 | −4.41 (−8.62 to −0.19) | .04 | |

| 8 | 48.80 (45.28 to 52.32) | 51.20 (47.59 to 54.81) | 55.19 (51.30 to 59.08) | −6.39 (−11.64 to −1.15) | .02 | −3.99 (−9.30 to 1.31) | .14 | −2.40 (−7.44 to 2.64) | .35 | |

| 12 | 48.93 (45.29 to 52.57) | 49.94 (46.20 to 53.68) | 54.81 (50.88 to 58.75) | −5.88 (−11.24 to −0.52) | .03 | −4.87 (−10.30 to 0.55) | .08 | −1.01 (−6.23 to 4.21) | .70 | |

| 26 | 49.22 (45.51 to 52.92) | 47.38 (43.58 to 51.18) | 54.39 (50.37 to 58.42) | −5.18 (−10.65 to 0.29) | .06 | −7.01 (−12.55 to −1.48) | .01 | 1.84 (−3.47 to 7.14) | .50 | |

| FACT-G total | ||||||||||

| 4 | 101.59 (99.96 to 103.23) | 100.07 (98.39 to 101.75) | 97.69 (95.82 to 99.55) | 3.91 (1.43 to 6.38) | .002 | 2.38 (−0.13 to 4.89) | .06 | 1.53 (−0.82 to 3.87) | .20 | |

| 8 | 101.05 (99.14 to 102.96) | 100.12 (98.18 to 102.05) | 99.51 (97.38 to 101.64) | 1.55 (−1.32 to 4.41) | .29 | 0.61 (−2.27 to 3.49) | .68 | 0.94 (−1.78 to 3.66) | .50 | |

| 12 | 102.05 (100.28 to 103.83) | 98.41 (96.60 to 100.23) | 97.44 (95.53 to 99.36) | 4.61 (1.99 to 7.23) | .001 | 0.97 (−1.67 to 3.61) | .47 | 3.64 (1.10 to 6.18) | .005 | |

| 26 | 100.45 (98.24 to 102.67) | 100.09 (97.82 to 102.35) | 98.67 (96.23 to 101.11) | 1.78 (−1.52 to 5.08) | .29 | 1.42 (−1.91 to 4.75) | .40 | 0.36 (−2.80 to 3.53) | .82 | |

| AES score | ||||||||||

| 4 | 10.78 (10.03 to 11.52) | 10.70 (9.91 to 11.48) | NA | NA | NA | 0.08 (−1.00 to 1.16) | .88 | |||

Abbreviations: AES, Acupuncture Expectancy Scale; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General; LS, least squares; NA, not applicable; SA, sham acupuncture; SOH, standard oral hygiene; TA, true acupuncture; XQ, Xerostomia Questionnaire.

eTable 2 in Supplement 2 provides raw means. Models adjusted for baseline outcome, treatment group, time, and interaction of treatment over time, with an unstructured covariance.

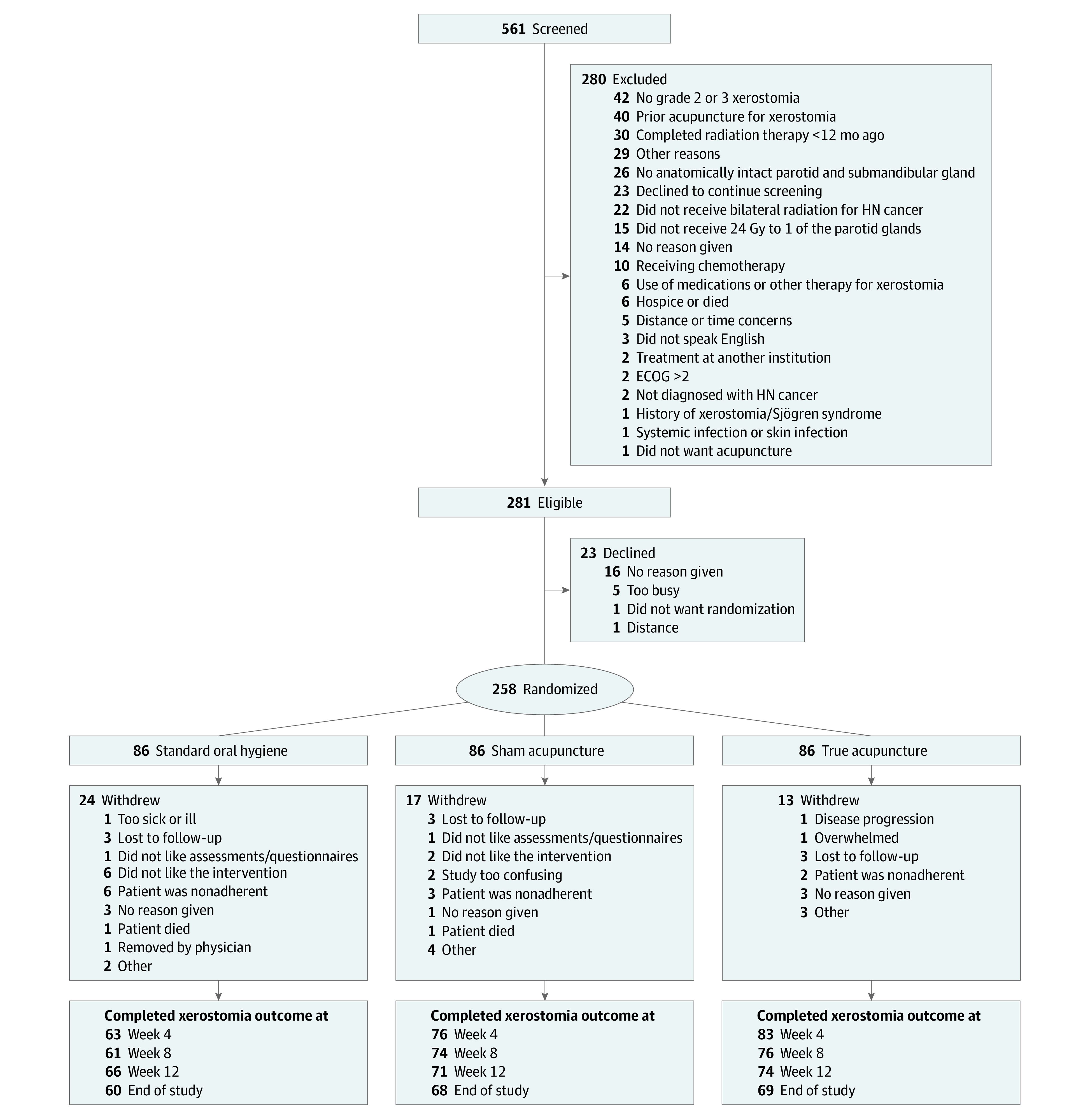

Enrollment and Retention

Of 561 screens, 281 patients (50.1%) were eligible (Figure 1), and 23 (4.1%) declined participation. The remaining 258 participants provided informed consent and then were randomized, resulting in 86 in each group and an 1:1:1 allocation. A total of 54 participants (20.9%) withdrew from the study before the week 4 assessment (TA: 13, SA: 17, and SOH: 24) (Figure 1). There were differential dropout rates at week 4 by group (TA, 2.4%; SA, 10.6%; and SOH, 23.8%; P < .001), job status (retired, 6.4%; employed, 10.5%; disabled/unable to work, 27.3%; and other/unknown, 19.2%; P = .02), race (African American, 44.4%; American Indian or Alaska Native, 50%; Asian, 7.7%; Native American or Pacific Islander, 100%; White, 10.7%; P = .007), and ethnicity (Hispanic, 31.3%; non-Hispanic, 10.9%; P = .03).

Figure 1. Patient Flowchart.

ECOG indicates Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HN, head and neck.

Treatments

Acupuncturist experience ranged from 1 to 20 or more years. Adherence was high in the TA and SA groups, with 94.4% (152 patients [TA, 83; SA, 69]) receiving 6 of 8 treatments and 78.3% (126 patients [TA, 72; SA, 54]) receiving all 8 treatments. After the week 4 assessment, 13 patients in the TA group and 12 in the SA group underwent a second course of treatment, with 82% of patients in the TA group and 100% of patients in the SA group receiving 6 or more treatments.

Xerostomia

There were no significant mean (SD) group differences in XQ at baseline (TA: 63.0 [17.1], SA: 62.1 [17.5], SOH: 63.2 [16.8]; P = .91) (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). The analysis of covariance (controlling for baseline XQ) at week 4 revealed a group main effect (P = .02), with TA reporting significantly lower XQ scores than SOH (TA: 50.6; SOH: 57.3; difference, −6.67; 95% CI, −11.08 to −2.27; P = .003), with marginal differences based on the adjusted P value between TA and SA (TA: 50.6; SA: 55.0; difference, −4.41; 95% CI, −8.62 to −0.19; P = .04), yet no significant differences between SA and SOH (SA: 55.0; SOH: 57.3, difference, −2.27; 95% CI, −6.76 to 2.23; P = .32) (Table 2; eTable 1 in Supplement 2 provides raw means).

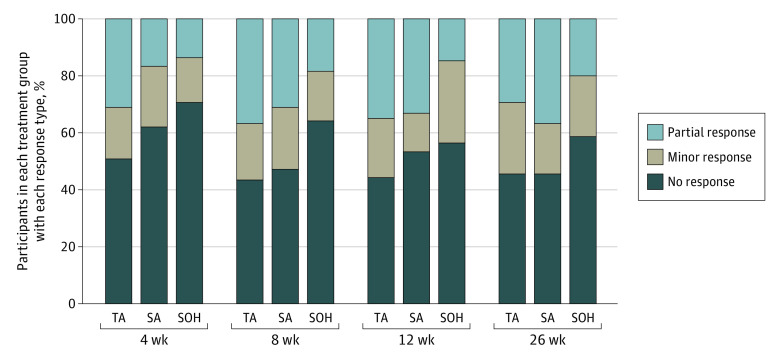

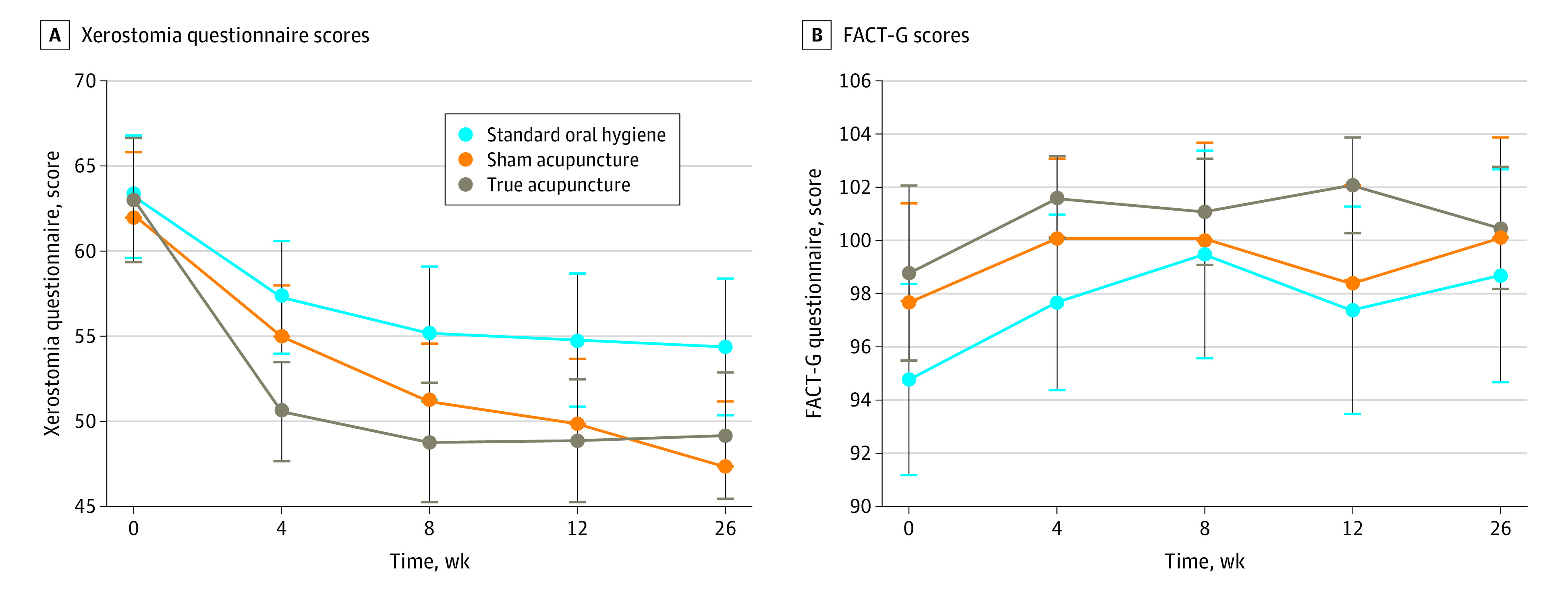

In the mixed-model analyses of repeated measures (Figure 2A), there was a significant group by time interaction revealing group differences at each time point. Similar to the week 4 outcomes, the TA group continued to report statistically significantly lower XQ scores at weeks 8 and 12 than the SOH group, yet by week 26 only the SA group reported lower XQ scores than the SOH group, with no other significant differences. Distributions of response were significantly different between TA and SOH at weeks 4, 8, and 12 (P = .03 for each time point) (Figure 3), with twice as many patients in the TA cohort having a partial response at week 4 (TA: 31.3% [26 of 83]; SA: 17.1% [13 of 76]; SOH: 14.1% [9 of 64]). Similarly, proportions of participants with clinically significant xerostomia (defined as XQ >30) were significantly different for TA compared with SOH at weeks 4 (84.3% [70 of 83] vs 95.3% [61 of 64]; P = .03) and 12 (73.0% [54 of 74] vs 90.9% [60 of 66]; P = .01). No other differences were observed for clinically significant xerostomia rates.

Figure 2. Least Squares Mean Model Estimates for Xerostomia Questionnaire Scores and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G) Scores by Treatment Group.

A, Least squares mean model estimates for Xerostomia Questionnaire. Unadjusted baseline mean and 95% CIs presented for reference, but adjusted mean and 95% CIs are presented for weeks 4, 8, 12, and 26. There were statistically significant differences between true acupuncture and standard oral hygiene (P = .003) at week 4 and between sham acupuncture and standard oral hygiene at week 26, true acupuncture vs standard oral hygiene at week 8 (P = .02), week 12 (P = .03), and week 26 (P = .06). B, Least squares mean model estimates for FACT-G scores. Unadjusted baseline mean and 95% CIs presented for reference, but adjusted mean and 95% CIs are presented for weeks 4, 8, 12, and 26. There were statistically significant differences between true acupuncture vs standard oral hygiene at week 4 (P = .002) and between true acupuncture vs standard oral hygiene (P = .001) and true acupuncture vs sham acupuncture (P = .005) at week 12.

Figure 3. Response Rates Based on Xerostomia Questionnaire (XQ) Scores by Treatment Group at Each Time Point.

Difference in distributions between true acupuncture (TA) and standard oral hygiene (SOH) was statistically significant at weeks 4, 8, and 12 (P = .03 for each time point). Difference in distribution between sham acupuncture (SA) and SOH was significant at week 12 (P = .01). Differences were assessed using χ2 tests. No response indicates any increase in XQ scores or decrease of less than 10 points; minor response, 10- to 19-point decrease in XQ score; and partial response, 20 points or more decrease in XQ score.

FACT-G

The mixed-model repeated-measures analyses for the FACT-G scores followed a similar pattern as XQ, revealing significant group differences at week 4 with higher scores in the TA compared with the SOH cohort (TA: 101.6; SOH: 97.7; difference, 3.91; 95% CI, 1.43-6.38; P = .002), and week 12, with higher scores in the TA vs SA cohort (TA: 102.1; SA: 98.4; difference, 3.64; 95% CI, 1.10-6.18; P = .005) and higher scores in the TA compared with the SOH cohort (TA: 102.1; SOH: 97.4; difference, 4.61; 95% CI, 1.99-7.23; P = .001), with no between-group differences at week 26 (Table 2 and Figure 2B). Multiple imputation sensitivity analyses were robust to the results found in the primary analyses, with the exception of TA vs SA at week 4 (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Acupuncture Expectancy Questionnaire

There were no significant group differences in expectations of the effect of acupuncture on dry mouth symptoms at any time point. This suggests that blinding was maintained (Table 1 baseline and Table 2, week 4).

Adverse Events

No serious adverse events occurred. Six adverse events were reported across all groups (SOH: 0; SA: 3; TA: 3). Adverse events with SA included 1 patient, facial edema, 1 patient, flulike symptom, and 1 patient, joint pain (all grade 3). Adverse events with TA included 1 patient, hypertension (grade 3), 1 patient, headache (grade 1), and 1 patient, bruising (grade 1).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first randomized, sham-controlled, phase 3, multicenter clinical trial to evaluate acupuncture for chronic RIX in patients with head and neck cancer after radiotherapy. The results are consistent with several past smaller trials.12,24,39,40,41,42,43 Although there were no statistically significant differences between TA and SA based on the adjusted P values, there was a 4.4-point difference (P = .04) with the only statistically significant differences emerging between TA and SOH. Similarly, 31.3% of patients receiving TA had a partial response at week 4 vs only 17.1% with SA and 14.1% with SOH, suggesting a clinically significant benefit with TA. Differences between TA and SOH remained through week 12. The SA group improved over time and reached statistically significant differences from SOH by week 26, but there were no significant differences between TA and SA at week 26, suggesting that both forms of acupuncture were effective. Although the absolute differences between groups did not reach 10 points on the XQ, the proportion of patients no longer meeting the clinical definition for xerostomia was only improved with TA vs SOH. Moreover, examination of changes in quality of life showed improvement with TA compared with SOH at week 4; the differences reached statistical significance between TA and SA and between TA and SOH at week 12. Both XQ and quality-of-life findings suggest that perhaps subsequent maintenance acupuncture treatments are needed to maintain or enhance the effects of acupuncture.

The sham procedure was effective in maintaining blinding, with both groups reporting high expectations of benefit after week 4. There were differential dropout rates at week 4, mainly noted in patients in the SOH group. Because real needles were inserted in the helix of the ears and a real point on the leg, the sham treatment cannot be considered a true placebo. Although placebo-controlled trials impart important information toward understanding mechanisms, the choice of placebo comparators in acupuncture trials remains highly debated. Thus, as other large, 3-arm acupuncture trials have demonstrated, the most relevant comparison is between TA and usual care.44,45,46

Although acupuncture mechanisms are not well understood, findings from multiple studies suggest possible central nervous system effects through manipulation of the fascia.15,16,47,48,49 Studies have revealed significant increased blood flow in the skin of the cheek of patients with xerostomia.47 Other plausible hypotheses suggest that increased production of certain neuropeptides after acupuncture stimulation may cause vasodilation and increased microcirculation.15,16,48 Deng et al49 explored neuronal substrates during acupuncture for RIX using functional magnetic resonance imaging. True acupuncture was associated with activation of areas of the brain where sensory stimuli and expectation/suggestion signals are integrated, an effect not seen with SA. Furthermore, TA caused significantly more saliva production, also related to neurologic changes.

Strengths and Limitations

This study had a number of strengths and limitations. The trial was unable to recruit a large sample of racially and ethnically underserved participants. Yet it recruited participants from more than 30 clinics, representing one of the largest acupuncture studies, increasing generalizability. Some positive effects associated with acupuncture may be due to nonspecific factors (eg, conditioning, expectations, self-empowerment, patient-practitioner relationship) that were not assessed.50 Most patients only received 4 weeks of acupuncture, and no maintenance treatments were provided.

Conclusions

Acupuncture is minimally invasive and inexpensive, has a low incidence of adverse effects, and was found to be superior to standard care in treating chronic RIX after treatment in this large phase 3 trial. Based on these and other findings, acupuncture may be considered as a treatment option for patients with chronic RIX.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Raw Means and Standard Deviations for All Outcomes Listed by Treatment Group and Time

eTable 2. Multiple Imputation Sensitivity Analysis for Least Square Mean Estimates With 95% Confidence Intervals for Each Treatment Group by Time

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Eisbruch A, Kim HM, Terrell JE, Marsh LH, Dawson LA, Ship JA. Xerostomia and its predictors following parotid-sparing irradiation of head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50(3):695-704. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(01)01512-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pacholke HD, Amdur RJ, Morris CG, et al. Late xerostomia after intensity-modulated radiation therapy versus conventional radiotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 2005;28(4):351-358. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000158826.88179.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisbruch A, Ten Haken RK, Kim HM, Marsh LH, Ship JA. Dose, volume, and function relationships in parotid salivary glands following conformal and intensity-modulated irradiation of head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45(3):577-587. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(99)00247-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertram U. Xerostomia: clinical aspects, pathology and pathogenesis. Acta Odontol Scand. 1967;25(suppl 49):e2410421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dreizen S, Brown LR, Handler S, Levy BM. Radiation-induced xerostomia in cancer patients: effect on salivary and serum electrolytes. Cancer. 1976;38(1):273-278. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin SC, Jen YM, Chang YC, Lin CC. Assessment of xerostomia and its impact on quality of life in head and neck cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy, and validation of the Taiwanese version of the xerostomia questionnaire. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36(2):141-148. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brizel DM, Wasserman TH, Henke M, et al. Phase III randomized trial of amifostine as a radioprotector in head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(19):3339-3345. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.19.3339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nutting CM, Morden JP, Harrington KJ, et al. ; PARSPORT trial management group . Parotid-sparing intensity modulated versus conventional radiotherapy in head and neck cancer (PARSPORT): a phase 3 multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):127-136. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70290-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisbruch A, Ship JA, Dawson LA, et al. Salivary gland sparing and improved target irradiation by conformal and intensity modulated irradiation of head and neck cancer. World J Surg. 2003;27(7):832-837. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7105-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chambers MS, Rosenthal DI, Weber RS. Radiation-induced xerostomia. Head Neck. 2007;29(1):58-63. doi: 10.1002/hed.20456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersen SW, Machin D. Acupuncture treatment of patients with radiation-induced xerostomia. Oral Oncol. 1997;33(2):146-147. doi: 10.1016/S0964-1955(96)00058-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blom M, Dawidson I, Fernberg JO, Johnson G, Angmar-Månsson B. Acupuncture treatment of patients with radiation-induced xerostomia. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1996;32B(3):182-190. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(95)00085-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blom M, Lundeberg T. Long-term follow-up of patients treated with acupuncture for xerostomia and the influence of additional treatment. Oral Dis. 2000;6(1):15-24. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2000.tb00316.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braga FP, Lemos Junior CA, Alves FA, Migliari DA. Acupuncture for the prevention of radiation-induced xerostomia in patients with head and neck cancer. Braz Oral Res. 2011;25(2):180-185. doi: 10.1590/S1806-83242011000200014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawidson I, Angmar-Månsson B, Blom M, Theodorsson E, Lundeberg T. Sensory stimulation (acupuncture) increases the release of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in the saliva of xerostomia sufferers. Neuropeptides. 1998;32(6):543-548. doi: 10.1016/S0143-4179(98)90083-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawidson I, Angmar-Mânsson B, Blom M, Theodorsson E, Lundeberg T. Sensory stimulation (acupuncture) increases the release of calcitonin gene-related peptide in the saliva of xerostomia sufferers. Neuropeptides. 1999;33(3):244-250. doi: 10.1054/npep.1999.0759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia MK, Meng Z, Rosenthal DI, et al. Effect of true and sham acupuncture on radiation-induced xerostomia among patients with head and neck cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12):e1916910. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia MK, Niemtzow RC, McQuade J, et al. Acupuncture for xerostomia in patients with cancer: an update. Med Acupunct. 2015;27(5):158-167. doi: 10.1089/acu.2015.1104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnstone PA, Niemtzow RC, Riffenburgh RH. Acupuncture for xerostomia: clinical update. Cancer. 2002;94(4):1151-1156. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnstone PA, Peng YP, May BC, Inouye WS, Niemtzow RC. Acupuncture for pilocarpine-resistant xerostomia following radiotherapy for head and neck malignancies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50(2):353-357. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(00)01530-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menezes ASDS, Sanches GLG, Gomes ESB, et al. The combination of traditional and auricular acupuncture to prevent xerostomia and anxiety in irradiated patients with HNSCC: a preventive, parallel, single-blind, 2-arm controlled study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2021;131(6):675-683. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2021.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rydholm M, Strang P. Acupuncture for patients in hospital-based home care suffering from xerostomia. J Palliat Care. 1999;15(4):20-23. doi: 10.1177/082585979901500404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics. 1975;31(1):103-115. doi: 10.2307/2529712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meng Z, Garcia MK, Hu C, et al. Randomized controlled trial of acupuncture for prevention of radiation-induced xerostomia among patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 2012;118(13):3337-3344. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen L, Danhauer SC, Rosenthal DI, et al. A phase III, randomized, sham-controlled trial of acupuncture for treatment of radiation-induced xerostomia (RIX) in patients with head and neck cancer: Wake Forest NCI Community Oncology Research Program Research Base (WF NCORP RB) trial WF-97115. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16)(suppl):12004. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.12004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deadman P, Al-Khafaji M, Baker K. A Manual of Acupuncture. Journal of Chinese Medicine Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion. Deng L, Gan Y, He Sea, eds. Foreign Languages Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park J, White A, Stevinson C, Ernst E, James M. Validating a new non-penetrating sham acupuncture device: two randomised controlled trials. Acupunct Med. 2002;20(4):168-174. doi: 10.1136/aim.20.4.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park JJ. Developing and validating a sham acupuncture needle. Acupunct Med. 2009;27(3):93. doi: 10.1136/aim.2009.001495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Usichenko TI, Dinse M, Hermsen M, Witstruck T, Pavlovic D, Lehmann C. Auricular acupuncture for pain relief after total hip arthroplasty—a randomized controlled study. Pain. 2005;114(3):320-327. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Usichenko TI, Dinse M, Lysenyuk VP, Wendt M, Pavlovic D, Lehmann C. Auricular acupuncture reduces intraoperative fentanyl requirement during hip arthroplasty—a randomized double-blinded study. Acupunct Electrother Res. 2006;31(3-4):213-221. doi: 10.3727/036012906815844265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Usichenko TI, Hermsen M, Witstruck T, et al. Auricular acupuncture for pain relief after ambulatory knee arthroscopy—a pilot study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2(2):185-189. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang LC. Auriculotherapy: Diagnosis and Treatment. Longevity Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570-579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mao JJ, Xie SX, Bowman MA. Uncovering the expectancy effect: the validation of the acupuncture expectancy scale. Altern Ther Health Med. 2010;16(6):22-27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events . version 5.0. November 27, 2017. Accessed April 9, 2024. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcae_v5_quick_reference_5x7.pdf

- 37.Sloan JA, Frost MH, Berzon R, et al. ; Clinical Significance Consensus Meeting Group . The clinical significance of quality of life assessments in oncology: a summary for clinicians. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(10):988-998. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0085-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.SAS/STAT 15.3 User’s Guide. SAS Institute Inc; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meng Z, Kay Garcia M, Hu C, et al. Sham-controlled, randomised, feasibility trial of acupuncture for prevention of radiation-induced xerostomia among patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(11):1692-1699. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.12.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cho JH, Chung WK, Kang W, Choi SM, Cho CK, Son CG. Manual acupuncture improved quality of life in cancer patients with radiation-induced xerostomia. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(5):523-526. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pfister DG, Cassileth BR, Deng GE, et al. Acupuncture for pain and dysfunction after neck dissection: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15):2565-2570. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simcock R, Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Group acupuncture to relieve radiation induced xerostomia: a feasibility study. Acupunct Med. 2009;27(3):109-113. doi: 10.1136/aim.2009.000935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simcock R, Fallowfield L, Monson K, et al. ; ARIX Steering Committee . ARIX: a randomised trial of acupuncture v oral care sessions in patients with chronic xerostomia following treatment of head and neck cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(3):776-783. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hershman DL, Unger JM, Greenlee H, et al. Comparison of acupuncture vs sham acupuncture or waiting list control in the treatment of aromatase inhibitor–related joint pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2241720. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.41720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mao JJ, Bowman MA, Xie SX, Bruner D, DeMichele A, Farrar JT. Electroacupuncture versus gabapentin for hot flashes among breast cancer survivors: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(31):3615-3620. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.9412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mao JJ, Xie SX, Farrar JT, et al. A randomised trial of electro-acupuncture for arthralgia related to aromatase inhibitor use. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(2):267-276. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.09.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blom M, Lundeberg T, Dawidson I, Angmar-Månsson B. Effects on local blood flux of acupuncture stimulation used to treat xerostomia in patients suffering from Sjögren’s syndrome. J Oral Rehabil. 1993;20(5):541-548. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1993.tb01641.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dawidson I, Angmar-Månsson B, Blom M, Theodorsson E, Lundeberg T. The influence of sensory stimulation (acupuncture) on the release of neuropeptides in the saliva of healthy subjects. Life Sci. 1998;63(8):659-674. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(98)00317-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deng G, Hou BL, Holodny AI, Cassileth BR. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) changes and saliva production associated with acupuncture at LI-2 acupuncture point: a randomized controlled study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:37. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaptchuk TJ, Kelley JM, Conboy LA, et al. Components of placebo effect: randomised controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ. 2008;336(7651):999-1003. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39524.439618.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Raw Means and Standard Deviations for All Outcomes Listed by Treatment Group and Time

eTable 2. Multiple Imputation Sensitivity Analysis for Least Square Mean Estimates With 95% Confidence Intervals for Each Treatment Group by Time

Data Sharing Statement