Abstract

The low-temperature treatment of 1,1-dibromo-1a,9b-cyclopropa[l]phenanthrene with butyllithium appeared to produce dibenzonorcarynyliden(e/oid) which could be intercepted with phencyclone to produce a hindered spiropentane. The spiropentane readily rearranges, thermally and photochemically, into a triphenylene phenol derivative. The spiropentane and its rearrangement product were characterized by X-ray crystallography.

Several years ago, we reported that the Doering–Moore–Skattebøl (D–M–S) reaction1−3 of 1,1-dibromo-1a,9b-cyclopropa[l]phenanthrene (1) with butyllithium and copper(II) chloride in THF gave the hydrocarbon 2, a cyclotetramer of the strained allene dibenzocycloheptatetraene (5), as shown in Scheme 1.4 Also formed as a byproduct in this reaction is the ether 6 which could be rationalized as an insertion reaction of dibenzonarcarnylidene (4), or a carbenoid equivalent 3 that qualitatively behaves like the carbene,5,6 with the THF used as solvent. We have also previously reported the ylide-forming reaction of 4 with THF.7

Scheme 1. Generation of a Formal Tetramer of Dibenzocycloheptatetraene That Was Previously Reported4 and the Interception of Dibenzonorcarynyliden(e/oid) with Phencyclone to Form a Congested Spiropentane Which Subsequently Rearranges, Thermally or Photochemically, to a Triphenylene Phenol (This Work).

Herein, we describe a congested spiropentane 8 formed in the reaction of 1 with butyllithium at low temperature in the presence of phencyclone (7) as also depicted in Scheme 1. It is notable that 8, with the phenanthrene ring endo to the biphenyl moiety, is produced exclusively, with no evidence for the formation of the exo diastereomer 9. Spiropentane 8 appears to be rather unstable and rearranges almost quantitatively into the phenol 10 upon exposure to heat or light. Interestingly, the color of 10 changed based on the solvent in which the rearrangement occurred. Specifically, thermal rearrangement in hexanes afforded 10 as a red solid that precipitated out of solution, while thermolysis in chloroform or photolysis in benzene-d6 afforded a colorless solid. Dissolving red 10 in dichloromethane irreversibly removed the red color (see the Supporting Information). Single-crystal X-ray structures of 8 and the red form of 10 are shown in Figure 1. Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction could not be obtained from the colorless solid. The FTIR spectra of the red and colorless forms of 10, however, appeared to be identical. One plausible explanation for these observations is that the red and colorless forms of 10 have a polymorphic relationship. Polymorphs can have sharply different colors,8 and our laboratory has also reported such an occurrence previously.9

Figure 1.

Single-crystal X-ray structures of 8 (top) and 10 (bottom). Thermal ellipsoids are shown at the 50% probability level.

Formation of 8 may be explained by the direct addition of 4 to 7 as shown in Scheme 1. An alternative possibility is the Michael addition of 3 to 7 to give the enolate 11 followed by an intramolecular nucleophilic displacement of bromide within 11 to form 8 (Scheme 2). Given the difficulty in effecting nucleophilic substitution reactions on cyclopropyl substrates,10 the mechanism shown in Scheme 2 was deemed unlikely, however, as it requires a hindered nucleophile to displace bromide from a tertiary center in an SN2-like process with an inversion of configuration at a cyclopropyl carbon.11

Scheme 2. An Alternative, but Unlikely, Mechanism for the Formation of 8 Initiated by a Michael Reaction.

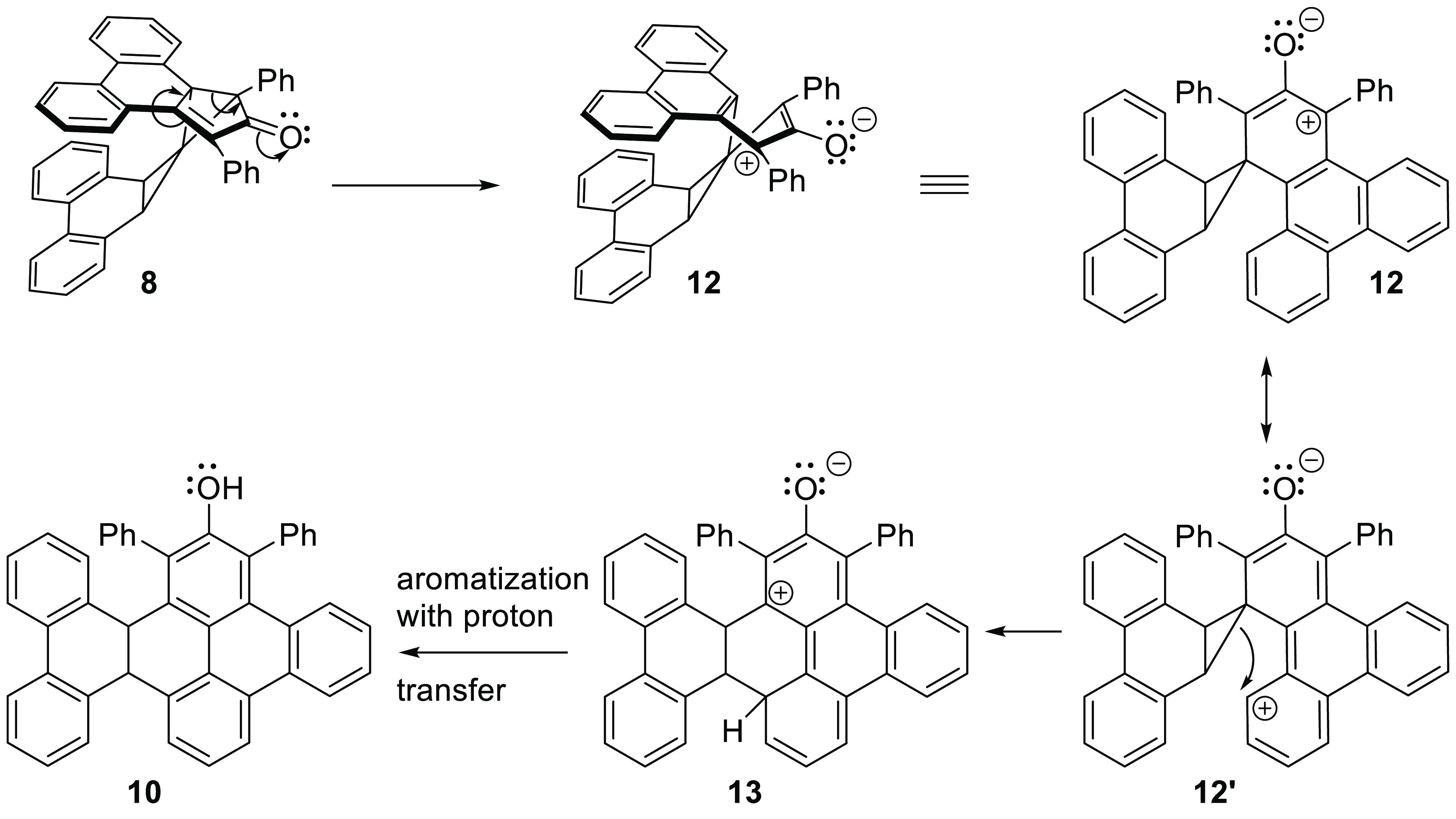

Although the precise manner by which 8 rearranges into 10 remains unknown, a plausible mechanistic hypothesis is offered in Scheme 3. The first step, which simultaneously aromatizes the central phenanthrene ring of the erstwhile phencyclone and relieves strain in the spiropentane moiety, leads to the zwitterion 12. It is notable that the anionic part of the zwitterion is an enolate, whereas the cation enjoys extensive benzylic stabilization. One particular resonance form of 12, designated as 12′, may be viewed as a vinylogous cyclopropylcarbinyl cation. Rearrangement of this cation, effectively initiating an electrophilic aromatic substitution, is accompanied by strain release in the cyclopropyl ring and formation of intermediate 13. Finally, a proton transfer accompanied by aromatization converts 13 into the observed phenol 10.

Scheme 3. Proposed Mechanism for the Rearrangement of Spiropentane 8 into Phenol 10.

The structure and reactivity of 4 were calculated at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/def2-TZVP//B2PLYP/def2-TZVP level of theory.12−19 These calculations indicated that triplet 4 was 15.40 kcal/mol higher in energy than the singlet (see the Supporting Information).20 The calculated potential energy surface (PES) connecting singlet 4 to allene 5 is shown in Figure 2. These calculations revealed that singlet carbene 4 has to overcome a barrier of 6.70 kcal/mol en route to 5, and that 5 was 49.3 kcal/mol lower in energy than 4.

Figure 2.

Potential energy surface diagram for the ring opening of singlet 4 to allene 5 through transition state TS computed at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/def2-TZVP//B2PLYP/def2-TZVP level of theory. Optimized geometries, relative energies, imaginary frequency, and T1 diagnostic values are shown.

Additionally, DLPNO-CCSD(T)/def2-TZVP//B3LYP/def2-SVP calculations13,14,17−19,21,22 indicated that the endo spiropentane adduct 8 is 6.68 kcal/mol more stable than its exo isomer 9. This preference is consistent with our experimental observations and may be attributable to the favorable π-stacking interactions between the phenanthrene and biphenyl moieties in 8 and the transition state leading up to it. The optimized structures of 8 and 9 are presented in the Supporting Information.

In summary, we have synthesized a crowded endo spiropentane 8, formed via the formal trapping of a dibenzonorcarynyliden(e/oid) (3/4) by phencyclone. Computational studies predict that the endo diastereomer is more stable than the exo form which was not detected as a product. Calculations also show that singlet 4 is more stable than the triplet and has to overcome a modest barrier to ring open to the relatively more stable strained cyclic allene 5. The light- or heat-induced rearrangement of 8 into phenol 10 was also observed and rationalized by a plausible mechanism.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Science Foundation for support of this work through grant number CHE-1955874.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.orglett.4c01001.

Experimental procedures, NMR and IR spectra, crystal structures, and computational details (DOCX)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- von E. Doering W.; LaFlamme P.M. A two-step synthesis of Allenes from olefins. Tetrahedron 1958, 2, 75–9. 10.1016/0040-4020(58)88025-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore W. R.; Ward H. R. Reactions of gem-dibromocyclopropanes with alkyllithium reagents. Formation of allenes, spiropentanes, and a derivative of bicyclopropylidene. J. Org. Chem. 1960, 25, 2073. 10.1021/jo01081a054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skattebol L. The Synthesis of Allenes from 1.1-Dihalocyclopropane Derivatives and Alkyllithium. Acta Chem. Scand. 1963, 17, 1683. 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.17-1683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahlokozera T.; Goods J. B.; Childs A. M.; Thamattoor D. M. Crystal Structure of a Cyclotetramer from a Strained Cyclic Allene. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 5095–5097. 10.1021/ol902177b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detailed calculation on the D–M–S reaction of the parent system, 1,1-dibromocyclopropane, indicates that the initially formed carbenoid species, 1-bromo-1-lithiocyclopropane, directly ring opens to the allene by eschewing the free carbene. See:Voukides A. C.; Cahill K. J.; Johnson R. P. Computational Studies on a Carbenoid Mechanism for the Doering-Moore-Skattebol Reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 11815–11823. 10.1021/jo401847v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbenoids have been defined as “intermediates which exhibit reactions qualitatively similar to those of carbenes without necessarily being free divalent species”. See:Closs G. L.; Moss R. A. Carbenoid formation of arylcyclopropanes from olefins, benzal bromites, and organolithium compounds and from photolysis of aryldiazomethanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 4042–53. 10.1021/ja01073a029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esquivel-Amores E.; Rogers K.; Thamattoor L. R.; Thamattoor D. M. Double trap: A single product from the THF-initiated interception of a cyclopropylidene(oid) and its rearranged strained cyclic allene. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1172, 108. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.01.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira B. A.; Castiglioni C.; Fausto R. Color polymorphism in organic crystals. Commun. Chem. 2020, 3, 34. 10.1038/s42004-020-0279-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein R. I.; Guo R.; Hughes C.; Maurer D. P.; Newhouse T. R.; Sisto T. J.; Conry R. R.; Price S. L.; Thamattoor D. M. Concomitant conformational dimorphism in 1,2-bis(9-anthryl)acetylene. CrystEngComm 2015, 17, 4877–4882. 10.1039/C5CE00745C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown H. C.; Fletcher R. S.; Johannesen R. B. I-Strain as a Factor in the Chemistry of Ring Compounds1, 2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 212–221. 10.1021/ja01145a072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For a rare example of an SN2-like displacement at a cyclopropyl carbon by an oxyanion, see:Turkenburg L. A. M.; De Wolf W. H.; Bickelhaupt F.; Stam C. H.; Konijn M. SN2 substitution with inversion at a cyclopropyl carbon atom: formation of 9-oxatetra-cyclo[6.2.1.01,6.06,10]undecane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 3471–3476. 10.1021/ja00376a037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S. Semiempirical hybrid density functional with perturbative second-order correlation. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124, 034108 10.1063/1.2148954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F.; Ahlrichs R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. 10.1039/b508541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F. Accurate Coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1057–65. 10.1039/b515623h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellweg A.; Hättig C.; Höfener S.; Klopper W. Optimized accurate auxiliary basis sets for RI-MP2 and RI-CC2 calculations for the atoms Rb to Rn. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2007, 117, 587–597. 10.1007/s00214-007-0250-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chmela J.; Harding M. E. Optimized auxiliary basis sets for density fitted post-Hartree–Fock calculations of lanthanide containing molecules. Mol. Phys. 2018, 116, 1523–1538. 10.1080/00268976.2018.1433336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riplinger C.; Pinski P.; Becker U.; Valeev E. F.; Neese F. Sparse maps—A systematic infrastructure for reduced-scaling electronic structure methods. II. Linear scaling domain based pair natural orbital coupled cluster theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 144, 024109 10.1063/1.4939030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riplinger C.; Sandhoefer B.; Hansen A.; Neese F. Natural triple excitations in local coupled cluster calculations with pair natural orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 134101 10.1063/1.4821834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riplinger C.; Neese F. An efficient and near linear scaling pair natural orbital based local coupled cluster method. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 034106 10.1063/1.4773581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methods, basis sets, auxilary basis sets, and other relevant information can also be found in the Supporting Information.

- Becke A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A Gen. Phys. 1988, 38, 3098–100. 10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.