Abstract

CDK5 kinase plays a central role in the regulation of neuronal functions, and its hyperactivation has been associated with neurodegenerative pathologies and more recently with several human cancers, in particular lung cancer. However, ATP-competitive inhibitors targeting CDK5 are poorly selective and suffer limitations, calling for new classes of inhibitors. In a screen for allosteric modulators of CDK5, we identified ethaverine and closely related derivative papaverine and showed that they inhibit cell proliferation and migration of non small cell lung cancer cell lines. Moreover the efficacy of these compounds is significantly enhanced when combined with the ATP-competitive inhibitor roscovitine, suggesting an additive dual mechanism of inhibition targeting CDK5. These compounds do not affect CDK5 stability, but thermodenaturation studies performed with A549 cell extracts infer that they interact with CDK5 in cellulo. Furthermore, the inhibitory potentials of ethaverine and papaverine are reduced in A549 cells treated with siRNA directed against CDK5. Taken together, our results provide unexpected and novel evidence that ethaverine and papaverine constitute promising leads that can be repurposed for targeting CDK5 in lung cancer.

Keywords: CDK5, kinase, small molecule inhibitor, lung cancer, proliferation, migration

CDK5 kinase is an atypical member of the CDK family, first identified in the brain and historically described as neurospecific due to the localization of its main partner p35/p25.1,2 Its neuronal functions have been largely described in various regulatory pathways in the central nervous system (CNS) such as axonal guidance, synaptic transmission, synapse formation, neuronal maturation, and migration.3 CDK5 dysregulation results in the development of several neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases, as well as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.4 Well beyond its neuronal functions, CDK5 regulates a wide variety of biological functions in non-neuronal tissues such as angiogenesis, myogenesis, vesicular transport, cell adhesion, and migration.5−7 Overexpression of CDK5 has been reported in many human cancers, including colorectal, head/neck, breast, lung, ovarian, lymphoma, prostatic, sarcoma, myeloma, and bladder cancers, thereby emerging as a relevant therapeutic target in oncology.8−10 In lung cancer in particular, several studies have established an inverse correlation between CDK5/p35 expression in patients with non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and survival, inferring that CDK5 constitutes a prognostic biomarker.11 Although the mechanism describing CDK5 regulation and role in lung cancer remains poorly characterized, it has been described as a tumor promoter that enhances cell proliferation and metastasis in lung cancer.12 CDK5 activity, required for migration and invasion of lung cancer cells, was shown to be regulated by achaete-scute homologue-1 (ASH1).13 Taken together, these studies provide a strong rationale for targeting CDK5 dysregulation to propose new therapeutic strategies for lung cancer.

Inhibition of CDK5 expression and/or activity reduces lung cancer cell proliferation and metastasis.12,13 However, there are currently no inhibitors of CDK5 used in the clinic for cancer therapeutics. Indeed, most inhibitors developed that target CDK5, such as roscovitine, dinaciclib, or AT7519, bind to the ATP pocket and are quite promiscuous, consequently eliciting non specific and off-target effect-related secondary effects.9 With the aim of developing new generation CDK5-specific inhibitors, we previously developed a conformational biosensor (CDKCONF5) that discriminates against ATP-competitive inhibitors, which was implemented for screening purposes, thereby enabling successful identification of allosteric CDK5 inhibitors.14 In this study, we report two new compounds, ethaverine and papaverine, that we identified through a repositioning approach using CDKCONF5 biosensor by screening a small library of drugs already characterized for therapeutic indications. The opium alkaloid papaverine and its ethyl derivative ethaverine are primarily used as antispasmodic drugs described to inhibit phosphodiesterase PDE4 and PDE10A.15,16 We characterized the effect of these two compounds in the A549 lung cancer cell line and found that they inhibited proliferation and migration. Combination of ethaverine or papaverine with the ATP-competitive inhibitor roscovitine further enhanced inhibition, suggesting a dual mechanism of action involving two different binding sites or populations of CDK5. Moreover, studies in H1299 and PC9 cell lines reveal differences in CDK5 inhibition, suggesting a possible dependence on p53. Stability studies did not reveal any major effect of ethaverine or papaverine on CDK5 protein levels. However, CETSA (cell extract thermodenaturation studies) revealed differences in CDK5 protein thermodenaturation profile, suggesting that ethaverine and papaverine interact with CDK5 in a cellular context. Finally siRNA-mediated downregulation of CDK5 in A549 cells considerably limits inhibition by ethaverine and papaverine, revealing the on-target selectivity of these compounds.

This study provides insight into drug repositioning and repurposing of ethaverine and papaverine, highlighting a promising and attractive targeting strategy through combination of these newly identified allosteric modulators of CDK5 and ATP-competitive inhibitors of CDK5.

Results

Ethaverine is a Conformational Modulator of CDK5 that Targets CDK5 in A549 Cells

The previously described conformational biosensor CDKCONF514 was applied to screen a small set of 640 compounds, selected on the basis of structural diversity, and including original scaffolds from F. Bihel’s lab (Université de Strasbourg) as well as known pharmacological tools dedicated to drug repurposing. While this assay discriminates against ATP-pocket binding compounds (10 μM ATP, roscovitine), compounds that bind CDK5 and induce conformational changes within the C-lobe and the activation loop are expected to induce significant changes in CDKCONF5 fluorescence. Ethaverine was identified as a hit at 10 μM in the primary screen with an increase in the fluorescence emission of CDKCONF5-Cy3 of 50%, significantly above that of the positive control (the CDK-activating protein CIV), although it is a much smaller compound (Figure 1A). To address the specificity of ethaverine for CDKCONF5, we compared its effect on the CDKCONF2 biosensor derived from CDK2, the most closely related kinase to CDK5, and found that at 10 μM, it did not induce any fluorescence enhancement indicative of its selectivity for CDK5 over CDK2 (Figure 1B). Ethaverine (Figure 1C, R = Et) is not a marketed drug but has been tested in humans, and its very close analog papaverine (Figure 1C, R = Me) has been used for decades as a vasodilator for the treatment of cerebral and peripheral ischemia associated with arterial spasm. Both papaverine and ethaverine act by inhibiting phosphodiesterase in smooth muscle cells, which produce increased tissue levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate and cyclic guanosine 3,5-monophosphate and subsequent relaxation of the vascular smooth muscle.15,16 As papaverine and ethaverine have been tested in humans by the oral route without showing any major toxic effect in patients,23,24 we considered both compounds for further studies. In order to address whether ethaverine and papaverine could inhibit CDK5 activity, we performed kinase activity assays with recombinant CDK5/p2518 using R-roscovitine as a positive control. These experiments revealed that ethaverine and papaverine did not inhibit the catalytic activity of CDK5, irrespective of the ATP concentration (10 and 200 μM) (Supplementary Figure S1), confirming that they do not bind the ATP pocket of CDK5, in line with their identification in a screen which discriminates against ATP-pocket binders, and that they do not tamper with its catalytic function, although they bind and modulate CDK5 conformation.

Figure 1.

Identification of Ethaverine as an allosteric modulator of CDK5. (A) Fluorescence-based screen for allosteric modulators of CDK5 with the CDKCONF5-Cy3 biosensor led to identification of ethaverine; Ctrl+ is 200 nM of the CDK-activating protein CIV and Ctrl- corresponds to 10 μM ATP as described in ref (14). (B) Fluorescence-based assay with CDKCONF2 biosensor as described in ref (17). Ethaverine does not modulate the fluorescence of CDKCONF2-Cy3. (C) Chemical structures of ethaverine and papaverine. Ethaverine bears four ethyl groups (R = Et), whereas papaverine bears four methyl groups (R = Me). (D) Thermodenaturation profiles of CDK5 from lysates of A549 cells following treatment with roscovitine, ethaverine, or papaverine at their IC50 concentration. Statistical significance: *p < 0.0332, **p < 0.0021.

In order to address whether ethaverine and papaverine might target CDK5 in A549 cells, we asked whether any of these inhibitors were indeed engaged in target binding in a cellular context. To this aim, we first determined the IC50 of these compounds on A549 cell proliferation after 24 h and found that all three compounds had very similar IC50 values: 9.1 ± 1.9, 10.6 ± 5.4, and 8 ± 3 μM for roscovitine, ethaverine, and papaverine, respectively (Supplementary Figure S2). We therefore treated A549 cells with each of these compounds at concentrations equal to their IC50 values and then subjected them to thermodenaturation (CETSA assays) essentially as described in ref (20), i.e., following 1 h treatment of cells with inhibitors (Figure 1D). The relative concentration of CDK5 protein was determined by Western blotting and quantified relative to its concentration at 37 °C. Comparison of the thermodenaturation profiles of CDK5 between mock-treated and roscovitine-treated A549 cells revealed a slight destabilization of CDK5 following roscovitine treatment, between 41 and 45 °C. Papaverine treatment yielded a CDK5 thermodenaturation profile similar to that of roscovitine. In contrast, treatment with ethaverine revealed a different profile tending toward stabilization of CDK5 compared to mock-treated A549 cells. The differences observed in all cases relative to mock-treated cells infer target engagement of CDK5. It should however be noted that statistical variability observed at different temperatures may be associated with incomplete target engagement after only 1 h inhibitor treatment in the CETSA protocol used.

Characterization of the Inhibitory Potential of Ethaverine and Papaverine on Proliferation of A549 Lung Cancer Cell Line

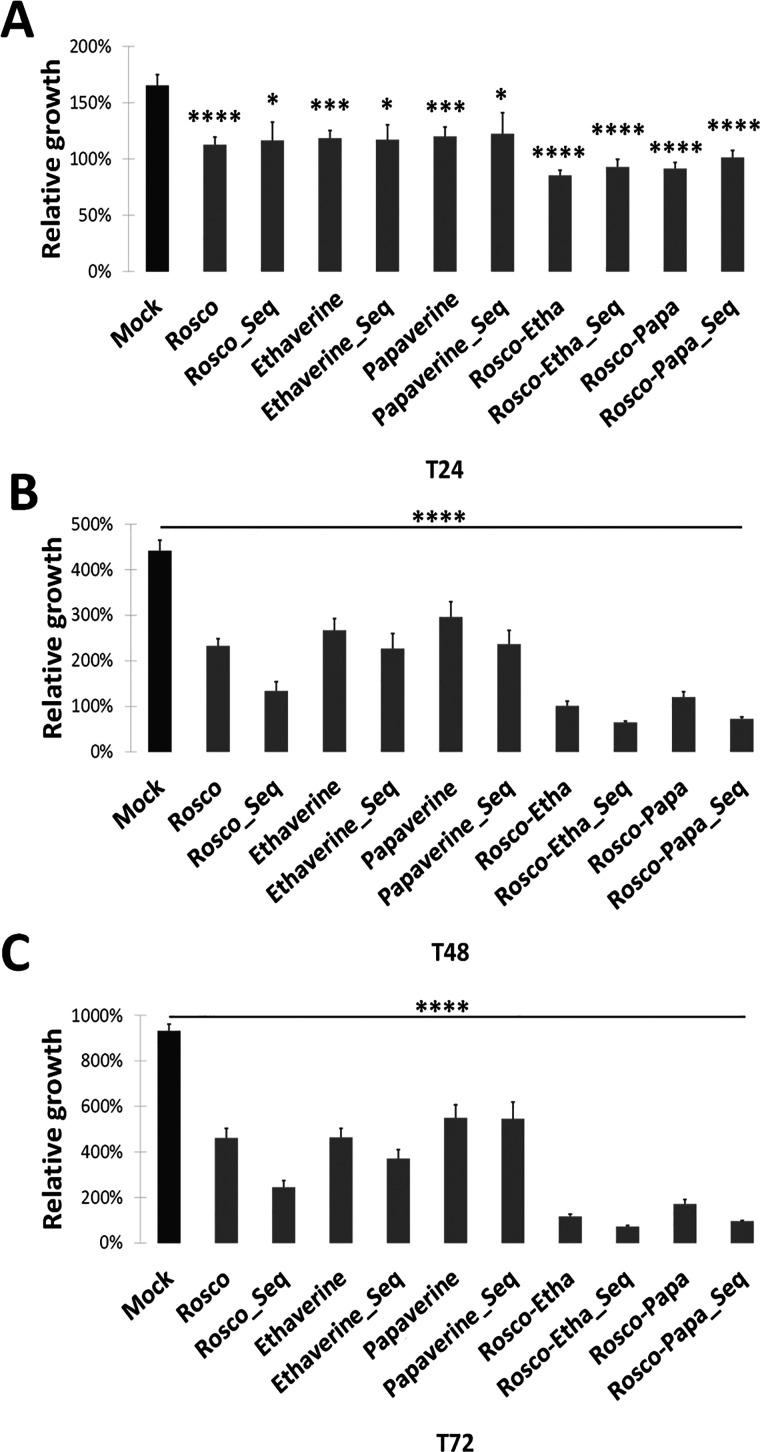

In order to gain further insight into the inhibitory potential of ethaverine and papaverine, we compared their efficacy after 24, 48, and 72 h treatment with IC50 concentrations, i.e., 9.1 ± 1.9, 10.6 ± 5.4, and 8 ± 3 μM for roscovitine, ethaverine, and papaverine, respectively (Figure 2A–C, Table 1,Supplementary Table S1). These kinetic studies revealed that the relative inhibitory efficacy of each compound increased over time with 28 ± 5.8, 39 ± 9.5, and 50 ± 8.6% inhibition of A549 proliferation after 24, 48, and 72 h treatment with 11 μM ethaverine, respectively. Very similar values were obtained following treatment with 8 μM papaverine with 27 ± 7, 33 ± 11.4, and 41 ± 10.2% inhibition and for 9 μM roscovitine with 32 ± 6.1, 47 ± 6.8, and 51 ± 9% inhibition after 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively.

Figure 2.

Papaverine and Ethaverine inhibit proliferation of A549 cells. Proliferation assays performed on A549 cells with 9 μM roscovitine, 11 μM ethaverine, or 8 μM papaverine alone, in combination, or following sequential addition (A) after 24 h, (B) after 48 h, and (C) after 72 h. Histograms represent mean relative growth of A549 cells as determined by crystal violet absorbance measured at 595 nm ± SEM relative to their absorbance at T0 in three independent experiments.

Table 1. Relative Inhibition of A549 Cells 24, 48, and 72 h after Treatmenta.

| treatments | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roscovitine | 31.8 ± 6.1 | 47.3 ± 6.8 | 50.5 ± 9 |

| Roscovitine_Seq | 29.6 ± 14 | 69.7 ± 14.9 | 73.7 ± 12.2 |

| Ethaverine | 28.3 ± 5.8 | 39.5 ± 9.5 | 50.2 ± 8.6 |

| Ethaverine_Seq | 29.1 ± 11.3 | 48.6 ± 14.5 | 60.2 ± 10.5 |

| Papaverine | 27.4 ± 7 | 33.0 ± 11.4 | 40.9 ± 10.2 |

| Papaverine_Seq | 26.0 ± 15.3 | 46.4 ± 12.6 | 41.4 ± 13.4 |

| Rosco-Etha | 48.3 ± 5.3 | 77.1 ± 10.2 | 87.5 ± 8.4 |

| Rosco-Etha_Seq | 43.8 ± 7.4 | 85.3 ± 4.3 | 92.3 ± 8.6 |

| Rosco-Papa | 44.6 ± 6 | 72.8 ± 9.9 | 81.6 ± 11.4 |

| Rosco-Papa_Seq | 38.6 ± 6 | 83.5 ± 5.2 | 89.7 ± 3.2 |

A549 cells were treated once with 9 μM Roscovitine, 11 μM Ethaverine, or 8 μM Papaverine alone or with combinations of 9 μM Roscovitine/11 μM Ethaverine (Rosco-Etha) or 9 μM Roscovitine/8 μM Papaverine (Rosco-Papa) or treated sequentially (“_Seq”) every 24 h with each compound or combinations. % Cell inhibition relative to the mock are represented as mean ± SEM.

To further address the potency of these drugs over time, we asked whether sequential treatment every 24 h might enhance inhibition observed with a single treatment of A549 cells (Figure 2A–C, Table 1). Sequential treatment with 9 μM roscovitine significantly improved the inhibition of proliferation, indicative of a cumulative effect which was already quite noticeable after 48h with 70 ± 14.9% inhibition compared to 47 ± 6.8% with a single treatment of roscovitine and 74 ± 12.2% inhibition compared to 51 ± 9% after 72 h. Likewise, sequential treatment with 11 μM ethaverine inhibited proliferation more potently but less significantly than roscovitine with 49 ± 14.5% compared to 39 ± 9.5% inhibition of proliferation with a single treatment after 48 h and 60 ± 10.5% compared to 50 ± 8.6% inhibition of A549 cell proliferation with a single treatment after 72 h. Sequential treatment with 8 μM papaverine exhibited a similar inhibitory profile to ethaverine at 48 h with 46 ± 12.6% compared to 33 ± 11.4% inhibition of proliferation with a single treatment after 48 h but no significant difference compared to single treatment after 72 h, with 41% inhibition A549 cell proliferation in both cases.

Since roscovitine targets the ATP pocket of CDK5, while ethaverine and its closely related derivative papaverine were identified as non-ATP pocket binding, allosteric modulators of CDK5 function, we asked to what extent their combination might further potentiate inhibition of A549 cell proliferation (Figure 2A–C, Table 1). While treatment of A549 cells with concentrations equal to IC50 values of roscovitine (9 μM), ethaverine (11 μM), or papaverine (8 μM) alone inhibited A549 proliferation on average by 30% after 24 h, the combination of roscovitine with ethaverine or with papaverine promoted a significant increase of inhibition, with 48 ± 5.3 and 45 ± 6% inhibition, respectively, after 24 h treatment. Likewise roscovitine/ethaverine and roscovitine/papaverine treatments induced 77 ± 10.2 and 73 ± 10.2% inhibition of A549 cell proliferation after 48 h treatment as compared to 47 ± 6.8, 39 ± 9.5, and 33 ± 11.4% for roscovitine, ethaverine, and papaverine, respectively. After 72 h treatment, the combinatorial treatments achieved 88 ± 8.4 and 82 ± 11.4% inhibition as compared to 51 ± 9, 50 ± 8.6, and 41 ± 10.2% for roscovitine, ethaverine, and papaverine. Although the combined treatments were not synergistic, the effect of roscovitine with either ethaverine or papaverine was additive and practically complete at 72 h.

Interestingly, when 9 μM roscovitine was combined with 5.5 μM (1/2 IC50) ethaverine, a similar inhibitory efficacy was observed with 53.8 ± 9.3, 78.1 ± 6.3, and 85.2 ± 2.2% proliferation inhibition after 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively (Supplementary Figure S3, Supplementary Table S2). Conversely, 9 μM roscovitine combined with 22 μM ethaverine (or 2 IC50) did not improve inhibition of proliferation significantly compared to the combination of 9 μM roscovitine with 11 μM ethaverine, with 56.9, 85.1, and 91.6% inhibition after 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively. Likewise combinatorial treatment of A549 cells with roscovitine and pPapaverine yielded additive effects that enabled complete or almost complete inhibition of A549 proliferation after 48–72 h treatment, with comparable inhibition efficacies whether papaverine was at 8 μM, 4 μM (1/2 IC50), or 16 μM (2 IC50) (Supplementary Figure S4, Supplementary Table S3).

Finally, sequential treatment of A549 cells with combinations of Roscovitine and either ethaverine or papaverine only induced a very slight increase in inhibition compared to a single treatment of these drug combinations, indicating that complete inhibition was essentially achieved with a single combination of the ATP-competitive inhibitor and an allosteric inhibitor of CDK5 after 48 and 72 h. Roscovitine/ethaverine sequential treatment promoted 85 ± 4.3 and 92 ± 8.6% inhibition after 48 and 72 h, respectively, as compared to 77 ± 10.2 and 88 ± 8.4% for roscovitine/ethaverine single treatment. Roscovitine/papaverine sequential treatment induced 84 ± 5.2 and 90 ± 3.2% inhibition after 48 and 72 h, respectively, compared to 77 ± 9.9 and 88 ± 11.4% for a single treatment (Figure 2A–C, Table 2,Supplementary Table S1).

Table 2. Relative Inhibition of H1299 and PC9 Cells 24, 48, and 72 h after treatmenta.

| cell line | treatments | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1299 | Roscovitine | 14.4 ± 12.3 | 26.5 ± 7.2 | 32.4 ± 8.7 |

| Ethaverine | 31.6 ± 12.4 | 40.7 ± 8.4 | 49.4 ± 9.2 | |

| Papaverine | 29.3 ± 13.9 | 34.5 ± 9.3 | 43.5 ± 8.7 | |

| Rosco-Etha | 36.4 ± 11.3 | 60.9 ± 7.3 | 75.5 ± 5.3 | |

| Rosco-Papa | 34.5 ± 13.8 | 56.3 ± 2.9 | 72.2 ± 6.7 | |

| PC9 | Roscovitine | 22.9 ± 12 | 27.9 ± 14.1 | 14.2 ± 6.3 |

| Ethaverine | 40.1 ± 12.1 | 48.1 ± 4.8 | 40.3 ± 5.7 | |

| Papaverine | 34.7 ± 14.1 | 32.0 ± 6.6 | 18.7 ± 4.2 | |

| Rosco-Etha | 45.4 ± 15 | 69.0 ± 5.1 | 72.3 ± 5.3 | |

| Rosco-Papa | 41.1 ± 17.2 | 62.2 ± 21.5 | 61.4 ± 9.8 |

H1299 and PC9 cells were treated with 9 μM Roscovitine, 11 μM Ethaverine, or 8 μM Papaverine alone or with combinations of 9 μM Roscovitine/11μM Ethaverine (Rosco-Etha) or 9 μM Roscovitine/8μM Papaverine (Rosco-Papa). % Cell inhibition relative to the mock data are represented as mean ± SEM.

Taken together, the differences observed between roscovitine, ethaverine, and papaverine when A549 cells were treated sequentially with these drugs as well as the increased inhibitory efficacy observed with combinations of roscovitine with ethaverine or papaverine highlight both differences in inhibitory potential over time and point to different mechanisms of action among roscovitine, ethaverine, and papaverine.

Roscovitine, Ethaverine, and Papaverine Exhibit Different Inhibitory Profiles in NSCLC Cell Lines with Different p53 Status

An interdependent regulatory mechanism has been described between CDK5 and p53.25 Since A549 cells are p53 +/+, we asked whether ethaverine and papaverine exhibited the same inhibitory efficacy in other NSCLC cell lines, in which p53 was either deleted or mutated. To this aim, the H1299 cell line which is p53–/– and the PC9 cell line which harbors the p53 R248Q mutation were treated with roscovitine, ethaverine, and papaverine.26 While the efficacy of ethaverine and papaverine in H1299 and PC9 was quite similar to that observed in A549 cells with an average 30% inhibition after 24 h treatment, roscovitine was much less efficient with only 14 ± 12.3 and 23 ± 12% inhibition in H1299 and PC9, respectively, compared to 32 ± 6.1% in A549 cells (Figure 3, Table 2,Supplementary Table S4). In line with this reduced efficacy of Roscovitine in H1299 cells, we observed that the combined treatment of roscovitine with either ethaverine or papaverine only inhibited H1299 cell proliferation by 36 ± 11.3 and 35 ± 13.8%, respectively, after 24h compared to 48 ± 5.3 and 45 ± 6% inhibition in A549 cells. PC9 cell proliferation was still inhibited to the same extent as A549 cells, with 45 ± 15 and 41 ± 17.2% inhibition after 24 h treatment. Comparison of the inhibitory efficacies of these drugs after 48h again revealed much lower efficacy of roscovitine in H1299 and PC9 cells with 27 ± 7.2 and 28 ± 14.1% inhibition, respectively, compared to 47 ± 6.8% inhibition of A549 cells, whereas ethaverine and papaverine exhibited very similar inhibitory efficacy in all three cell lines, with an average 40% inhibition of ethaverine and 33% inhibition of papaverine. Again, in line with the reduced efficacy of roscovitine, combined treatments lead to lower inhibition of proliferation of the H1299 and PC9 cell lines, with 61 ± 7.3 and 69 ± 5.1% inhibition following combined treatment with roscovitine and ethaverine in H1299 and PC9 cell lines compared to 77 ± 10.2% inhibition in A549 cell lines and 56 ± 2.9 and 62 ± 21.5% inhibition following combined treatment with roscovitine and papaverine in H1299 and PC9 cell lines compared to 73 ± 9.9% inhibition in A549 cells. The reduced efficacy of roscovitine in H1299 and PC9 cells was observed after 72 h with 32 ± 8.7 and 14 ± 6.3% inhibition in H1299 and PC9 cells compared to 51 ± 9% inhibition in A549 cells. However, treatment with ethaverine and papaverine exhibited different trends, the former inducing 49 ± 9.2, 40 ± 5.7, and 50 ± 9% inhibition of H1299, PC9, and A549 cells, respectively, while papaverine induced 44 ± 8.7 and 19 ± 4.2% inhibition in H1299 and PC9 cells compared to 41 ± 10.2% inhibition in A549 cells. Again, combined treatments with roscovitine/ethaverine and with roscovitine/papaverine were slightly less efficient in H1299 and PC9 cells, with 76 ± 5.3 and 72 ± 6.7% inhibition in H1299 cells and 72 ± 5.3 and 61 ± 9.8% in PC9 cells compared to 88 ± 8.4 and 82 ± 11.4% inhibition in A549 cells.

Figure 3.

Papaverine and ethaverine inhibit proliferation of H1299 and PC9 cells. Proliferation assays performed on (A) H1299 cells and (B) PC9 with 9 μM roscovitine, 11 μM ethaverine, or 8 μM papaverine alone or in combination as described for A549 cells in Figure 2. Histograms represent mean relative growth of cells as determined by crystal violet absorbance measured at 595 nm ± SEM relative to their absorbance at T0 in three independent experiments. Statistical significance: *p < 0.0332, **p < 0.0021, ***p < 0.002, and ****p < 0.0001.

To address whether the differences in response between these three cell lines were associated with differences in IC50 values for roscovitine, ethaverine, and papaverine, we determined the IC50 values for each drug in PC9 and H1299 cell lines (Supplementary Figure S2). IC50 values for PC9 cells are 19.8 ± 1.6 for roscovitine, 24.7 ± 7.6 for ethaverine, and 23.4 ± 2.4 for papaverine. In H1299 cells, the IC50 values are 16.6 ± 4.8 for roscovitine, 20.3 ± 7.3 for ethaverine, and 18.5 ± 3 for papaverine. Furthermore, statistical analysis revealed that the main and most significant differences in inhibitory efficacy between A549 cells and the two other cell lines were observed for roscovitine at 24, 48, and 72 h, as well as for ethaverine in PC9 cells and papaverine in PC9 cells at 24 and 72 h (Supplementary Figure S5). While differences in the IC50 values for roscovitine between A549 and the two other cell lines can explain the lower inhibitory efficacy obtained in our experiments with treatments using the IC50 concentrations determined in A549 cells, they cannot explain the greater inhibitory efficacy in PC9 cells for ethaverine and papaverine since the IC50 values for these two compounds are 2–3 fold greater than those in A549 cells. Likewise it is quite surprising to observe similar inhibitory efficacies of H1299 cells in our experiments for ethaverine and papaverine since their IC50 values are approximately 2-fold greater than those in A549 cells.

Taken together, these results raise the question of CDK5 inhibition relative to the p53 status. They reveal that the ATP-competitive inhibitor roscovitine and the allosteric modulators ethaverine and papaverine still inhibit CDK5 efficiently in an additive fashion when combined. However, they also show that ethaverine and papaverine are more robust inhibitors than Roscovitine since efficacy of the latter is reduced when wild-type p53 is not expressed, whereas ethaverine and papaverine efficacy is essentially identical, irrespective of the p53 status. Since CDK5 has been shown to stabilize and promote p53 activation, thereby contributing to neuronal cell death,25 we further investigated whether ethaverine might somehow impact p53 expression and found that p53 levels increase following treatment of A549 cells with 11 μM ethaverine for 48 h (Supplementary Figure S6).

Knockdown of CDK5 with siRNA Combined with Drugs Targeting CDK5 Reduces Inhibition of A549 Cell Proliferation by Ethaverine

To address the selectivity of CDK5 inhibition by ethaverine and roscovitine, we finally asked whether these drugs might still be effective on inhibition of A549 proliferation following downregulation of CDK5 protein by siRNA treatment. To this aim, we first established experimental conditions to achieve a significant knockdown of CDK5 protein (40–50%) 24 h following treatment of A549 cells with 100 or 200 nM siRNA complexed with the cell-penetrating peptide CADY as previously described19 (Figure 4A). siRNA directed against CDK5 induced a transient inhibition of A549 cell proliferation when cells were treated once, i.e., 26% after 24 h and 19% after 48 h (Figure 4B, Table 3). However, a second siRNA treatment 24 h after the first (siRNA 1 + 2) elicited a greater inhibition of CDK5 proliferation, i.e., 51% compared to 19% inhibition 48 h after initial treatment, and a third boost of siRNA led to 62% inhibition 72 h after initial treatment. When cells were treated with roscovitine/ethaverine combination (IC50 concentration of each), 24 h after A549 cells had been treated once with siRNA directed against CDK5 and incubated for another 24 h (i.e., 48 h total siRNA + Rosco/Etha), there was an additional 25% inhibition of proliferation, relative to A549 cells treated once with siRNA alone, inferring that there was still plenty of active CDK5 to be inhibited by roscovitine/ethaverine. In contrast, no additional inhibition of A549 cell proliferation was observed when cells were treated with roscovitine/ethaverine following a double treatment with siRNA (siRNA1 + 2 + Rosco/Etha) relative to cells treated twice with siRNA alone (siRNA 1 + 2) 48 h after the first treatment, with 42% ± 5.2 and 51% ± 1.7 inhibition, respectively. Likewise, cells treated with a combination of roscovitine/ethaverine following daily treatment with siRNA (siRNA 1 + 2 + 3 + Rosco/Etha) with 66% ± 2.7 inhibition of proliferation after 72 h did not exhibit any additional inhibition compared to cells treated with roscovitine/ethaverine alone for 72 h, with 66% ± 1.5 inhibition of proliferation and cells treated three times with siRNA directed against CDK5 (siRNA 1 + 2 + 3) with 62% ± 5.1 inhibition. Taken together, these results infer that once CDK5 protein levels are significantly downregulated, there is no further inhibition possible, in line with the selectivity of Ethaverine for CDK5. While CDK5 levels are reduced by 40–50% following a single siRNA treatment after 24 h, CDK5 levels increase again significantly after 48 h, implying that it is resynthesized following the 24 h knockdown (Figure 4C). In contrast, a triple siRNA treatment leads to 71% CDK5 knockdown relative to mock at 72 h. This significant knockdown of CDK5 protein is in line with both the significant inhibition of A549 cell proliferation after 72 h and also explains why roscovitine and ethaverine cotreatment has no further effect on cell proliferation of the triple siRNA-treated cells.

Figure 4.

Knockdown of CDK5 with siRNA combined with ethaverine and papaverine treatments in A549 cells. (A) A549 cells were treated with 100 or 200 nM siRNA targeting CDK5. Representative Western blots of CDK5 and GAPDH and quantification of relative CDK5 protein levels in 20 μg lysates from mock and siRNA-treated A549 cells from three independent experiments after 24 h treatment. (B) Crystal violet proliferation assay of mock-treated A549 cells and A549 cells treated with 100 nM siRNA targeting CDK5 one, two, or three times (siRNA 1, 1 + 2 or 1 + 2 + 3), after 24, 48, and 72 h alone or combined with roscovitine/ethaverine treatment (24 h after the first siRNA treatment). (C) Western blot of CDK5 levels 48 h after the first siRNA treatment and after 72 h with three siRNA treatments and their respective mock-treated cells at 24 h and at 72 h; quantification of CDK5 levels in treated cells relative to that in mock-treated cells at the same time points.

Table 3. (see Figure 4) Relative Inhibition of A549 Cells Treated with siRNA Alone or Combined with Roscovtine/Ethaverinea.

| treatments | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h |

|---|---|---|---|

| siRNA 1 | 25.7 ± 3 | 19.3 ± 0.7 | |

| siRNA 1 + 2 | 51.1 ± 1.7 | ||

| siRNA 1 + 2 + 3 | 62.2 | ||

| Rosco/Etha | 28.3 ± 1.7 | 66.2 ± 1.5 | |

| siRNA 1 + Rosco/Etha | 44.6 ± 0.7 | ||

| siRNA 1 + 2 + Rosco/Etha | 42.0 ± 5.2 | ||

| siRNA 1 + 2 + 3 | 62.1 ± 5.1 | ||

| siRNA 1 + 2 + 3 + Rosco/Etha | 66 ± 2.7 |

A549 cells were treated with 100 nM siRNA 24 h after seeding, and then again 24 and 48 h later alone or combined with Roscovitine/Ethaverine. % Cell inhibition relative to the mock measured 24 and 48 h after inhibitor treatment are represented as mean ± SEM.

Time-Lapse Studies of Kinetics of Cell Division Inhibition and Migration

To gain further insight into the kinetics and mechanism leading to inhibition of cell proliferation, we performed time-lapse imaging on A549 cells treated with Roscovitine, Ethaverine or Papaverine alone at their IC50 value, or in combination and counted the number of cell divisions following each treatment over the first 24 h, then during the interval between 24 and 48 h (Figure 5 and Supplementary Tables S5 and S6). These studies revealed that inhibition of cell division was more effective during the second 24 h interval for Ethaverine and Papaverine, whereas the average number of cell divisions remained similar for cells treated with Roscovitine during the first 24 h post-treatment and during the interval from 24–48 h. Combinations of either Ethaverine or Papaverine with Roscovitine were already quite effective during the first 24 h and cell division remained inhibited up to 48 h.

Figure 5.

Time-lapse imaging of A549 cells treated with ethaverine and papaverine reveals differences in cell division A549 cells were either mock-treated or treated with roscovitine, ethaverine, papaverine at their IC50 concentration or cotreated with roscovitine/ethaverine or roscovitine/papaverine and timelapse microscopy was performed (a) for the first 24 h following treatment and (b) between 24 and 48 h post-treatment. The total number of cell divisions was counted from the images acquired in three independent experiments and six different fields per experiment and are represented as box plots. Statistical significance: ****p < 0.0001.

We further performed FACS analysis following propidium iodide staining of A549 cells treated with Roscovitine or Ethaverine for 48 h, but did not observe any major effect on the 2N or 4N content of cells (Supplementary Figure S7). Western Blots of cyclin A, cyclin B, phospho-cyclin B, and phospho-Histone H3, revealed a net increase in cyclin A levels, a decrease in cyclin B1 levels, and slight increase in phosphor-cyclin B1 and phosphor-Histone H1 (Supplementary Figure S8). We finally addressed whether apoptosis was induced and performed Western blots of cleaved caspase 3, caspase 8, caspase 9 and cleaved PARP after 48 h treatment with 10 μM ethaverine. Quantification of their expression levels relative to GAPDH revealed an increase in caspase 8 and 3, but no significant increase in cleaved caspase 9 or PARP (Supplementary Figure S9).

Since CDK5 has been reported for its function in cell migration,27−31 we further asked whether ethaverine and papaverine might affect this process in addition to cell division. To this aim, a standard “scratch test”21,22 was performed on A549 cells grown to confluence by inflicting a wound and monitoring the kinetics of recolonization over 24 and 48 h (Figure 6, Supplementary Figure S10 and Supplementary Tables S7 and S8). Mock-treated cells recolonized the wound surface quite rapidly, essentially during the first 24 h. Roscovitine treatment reduced migration of cells to recolonize the wound by approximately half during the first 24 h but, after this time, exhibited similar kinetics to mock-treated cells. In contrast, ethaverine and papaverine exhibited a very similar behavior to mock-treated cells over the first 24 h but then completely stopped migrating between 24 and 48 h. Combined treatment of roscovitine and either ethaverine or papaverine affected migration similarly to roscovitine during the first 24 h and almost completely inhibited migration during the next 24 h, following a similar trend to cells treated with ethaverine and papaverine alone. Taken together, these results again point to distinct mechanisms of action for roscovitine and ethaverine/papaverine, the former affecting migration at an early stage and the latter 24–48 h after treatment, whether alone or in combination.

Figure 6.

Time-lapse imaging of A549 cells treated with ethaverine and papaverine reveals differences in cell migration. A549 cells were either mock-treated or treated with roscovitine, ethaverine, or papaverine at their IC50 concentrations or cotreated with roscovitine/rthaverine or roscovitine/papaverine, and time-lapse microscopy was performed for the first 24 h following treatment and between 24 and 48 h post-treatment. (a) Ability of cells to recolonize the wounded area in the well where a scratch had been made is represented as the percentage of surface coverage relative to T0 (scratch) Histogram values represent the mean ± SD from five different fields in each of two independent experiments. Statistical significance: *p < 0.0332, **p < 0.0021, ***p < 0.002, and ****p < 0.0001. (c) Micrographs of mock-treated and ethaverine-treated cells (b) Representative micrographs of mock-treated cells and cells treated with papaverine.

Discussion

Lung cancers and, in particular, NSCLC currently suffer from a lack of efficient targeted therapies. CDK5 hyperactivity has been reported in human lung cancers and constitutes an attractive therapeutic target.11,12 Although a wide variety of CDK5 inhibitors are available, including compounds targeting the ATP pocket such as roscovitine, purvalanol, dinaciclib, and AT7519 and peptides targeting the CDK5/p25 interface,9 the former lack selectivity, resulting in a variety of undesirable secondary effects, and the latter are characterized by penetration and bioavailability issues that limit their development for clinical use.

In this study, we report on the identification of ethaverine and its closely related derivative papaverine, which we have identified as allosteric modulators of CDK5 using a conformational CDK5 biosensor.14 Since ethaverine and papaverine are well-established PDE inhibitors,15,16 it was quite surprising to identify these compounds repositioned as CDK5 binders and modulators of its conformation. Our in vitro assays with CDKCONF5/CDKCONF2 indicate that these compounds indeed bind selectively to CDK5, and our CETSA studies suggest that ethaverine and papaverine interact physically with CDK5 in A549 cells since its thermodenaturation profile was affected following treatment with these inhibitors.

We demonstrate that ethaverine and papaverine target CDK5 function in cell proliferation and migration, thereby offering alternatives to conventional ATP-competitive inhibitors. We have shown that these compounds inhibit proliferation of the A549 lung cancer cell line with moderate efficiency, comparable to that of roscovitine. However, we have also found that their combination with the ATP-competitive inhibitor roscovitine leads to essentially complete inhibition of proliferation, suggesting that ethaverine/papaverine and roscovitine may simultaneously target CDK5 through different binding pockets or alternatively target different populations of CDK5. In fact, the differences observed between roscovitine, ethaverine, and papaverine throughout this study, whether in proliferation assays, following sequential treatments, in different cell lines, or in time-lapse imaging studies of cell division and migration, point to different mechanisms of action between these newly identified allosteric modulators of CDK5 and roscovitine. Last but not least, our finding that ethaverine and papaverine are more robust inhibitors than roscovitine in cells that do not express wild-type p53 underscores their therapeutic attractivity in cancers that lack p53 or express mutant forms such as R248Q.

We have previously shown that combination strategies using kinase inhibitors that target CDKs through different mechanisms of action constitute promising therapeutic strategies enabling to achieve complete inhibition.32 In this study, we demonstrate that the combination of ethaverine or papaverine with the ATP-competitive inhibitor roscovitine induces an additive and efficient inhibition of NSCLC cell proliferation. Hence, the combination of these different compounds is an attractive strategy for anticancer therapeutics that offers several advantages a single drug cannot achieve. ATP-competitive kinase inhibitors are notorious for their promiscuity as well as their ability to induce resistance, essentially associated with mutations in the ATP-binding pocket or compensation mechanisms.33,34 In contrast, allosteric modulators are believed to achieve greater selectivity by targeting pockets and interfaces which are not conserved in different kinases and little if any resistance.35−38

Conclusions

This study provides insight into drug repositioning and repurposing of ethaverine and papaverine and highlights a promising and attractive targeting strategy through a combination of these newly identified allosteric modulators of CDK5 and ATP-competitive inhibitors of CDK5. Our strategy emphasizes the originality and relevance of a conformational biosensor to identify allosteric modulators of kinase function, providing a means to screen for “old drugs” which may be repurposed for cancer therapeutics. It also reveals that combinatorial treatment with allosteric drugs and ATP-competitive inhibitors can enhance inhibition of the same target, thereby reducing the overall concentration of drugs required for treatment and potentially preventing emergence of resistance. The efficient inhibition of lung cancer cell proliferation and migration by ethaverine/papaverine and roscovitine suggests that CDK5 targeting could involve either two distinct binding sites or two conformationally distinct populations of CDK5. The combination of compounds targeting the same kinase with different mechanisms of action can be expected to tamper with distinct functions or signaling processes simultaneously and therefore constitutes an efficient therapeutic strategy. Moreover a combination of FDA-approved inhibitors targeting other kinases currently used in NSCLC such as erlotinib, gefinitib, or crizotinib or CDK4/6 inhibitors abemaciclib, palbociclib, and ribociclib might potentially also be combined with ethaverine or papaverine.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the continuous support from the CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique). We acknowledge the MRI imaging facility (CRBM Montpellier, FRANCE), a member of the national infrastructure France-BioImaging and Euro-BioImaging. The authors also thank the Cancéropôle Grand Ouest (3MC network—Marine Molecules, Metabolism and Cancer), GIS IBiSA (Infrastructures en Biologie Santé et Agronomie), and Biogenouest (Western France life science and environment core facility network supported by the Conseil Régional de Bretagne) for supporting the KISSf screening facility (FR2424, CNRS and Sorbonne Université), Roscoff, France.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CDK

cyclin-dependent kinase

- CDK5

cyclin-dependent kinase 5

- NSCLC

non small cell lung cancer.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsptsci.4c00023.

CDK5/p25 kinase activity inhibition by roscovitine, ethaverine, and papaverine; determination of IC50 values for roscovitine, ethaverine, and papaverine in A549 cells; A549 proliferation assay following treatment with ethaverine and roscovitine/ethaverine; A549 proliferation assay following treatment with papaverine and roscovitine/papaverine; statistical differences between cell lines following treatment with drugs; Western blotting of p53 levels in A549 cells treated with ethaverine; FACS analysis of A549 cells treated with roscovitine, ethaverine, and papaverine; Western blotting of cell cycle markers; Western blotting of apoptosis markers; time-lapse imaging of A549 cell migration; relative proliferation of A549 cells; relative proliferation and inhibition of A549 cells; and relative proliferation of A549 cells (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors./All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work was funded by the LABEX Medalis (ANR-10-LABX-0034) and by the Interdisciplinary Thematic Institute IMS (Institut du Médicament de Strasbourg), as part of the ITI 2021–2028 program of the University of Strasbourg, CNRS and Inserm supported by IdEx Unistra (ANR-10-IDEX-0002) and SFRI (STRAT’US project, ANR-20-SFRI-0012) under the framework of the French Investments for the Future Program. A.L. received a fellowship from the Princely Government of Monaco.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hellmich M. R.; Pant H. C.; Wada E.; Battey J. F. Neuronal cdc2-like kinase: a cdc2-related protein kinase with predominantly neuronal expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992, 89, 10867–10871. 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai L.-H.; Delalle I.; Caviness V. S.; Chae T.; Harlow E. p35 is a neural-specific regulatory subunit of cyclin-dependent kinase 5. Nature 1994, 371, 419–423. 10.1038/371419a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhavan R.; Tsai L. H. A decade of CDK5. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 749–749. 10.1038/35096019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung Z. H.; Ip N. Y. CDK5: A multifaceted kinase in neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Cell Biol. 2012, 22, 1696175. 10.1016/j;tcb.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Vallejos E.; Utreras E.; Gonzales-Billault C. Going out of the brain: Non-nervous system physiological and pathological functions of Cdk5. Cell Signal. 2012, 24, 44–52. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S.; Sicinski P. A kinase of many talents: Non-neuronal functions of CDK5 in development and disease. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 190287 10.1098/rsob.190287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales J. L.; Lee K. Y. Extraneuronal roles of cyclin-dependent kinase 5. BioEssays 2006, 28, 1023–1034. 10.1002/bies.20473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozo K.; Bibb J. A. The Emerging Role of Cdk5 in Cancer. Trends Cancer 2016, 63, 217–232. 10.1002/hep.28274.Integrin. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyressatre M.; Prével C.; Pellerano M.; Morris M. C. Targeting cyclin-dependent kinases in human cancers: From small molecules to peptide inhibitors. Cancer (Basel). 2015, 7, 179–237. 10.3390/cancers7010179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shupp A.; Casimiro M. C.; Restell R. G. Biological functions of CDK5 and potential CDK5 targeted clinical treatments. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 17373–17382. 10.18632/oncotarget.14538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. L.; Wang X. Y.; Huang B. X.; Zhu F.; Zhang R. G.; Wu G. Expression of CDK5/p35 in resected patients with non-small cell lung cancer: Relation to prognosis. Med. Oncol. 2011, 28, 673–678. 10.1007/s12032-010-9519-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J.; Xie S.; Liu Y.; Shen C.; Song X.; Zhou G. L.; Wang C. CDK5 functions as a tumor promoter in human lung cancer. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 3950–3961. 10.71.50/jca.25967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demelash A.; Rudrabhatla P.; Pant H. C.; Wang X.; Amin N. D.; McWhite C. D.; Naizhen X.; Linnoila R. I. Achaete-scute homologue-1(ASH) stimulates migration of lung cancer cells through Cdk5/p35 pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell 2012, 23, 2856–2866. 10.1091/mbc.e10-12-1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyressatre M.; Arama D. P.; Laure A.; González-Vera J. A.; Pellerano M.; Masurier N.; Morris M. C. Identification of Quinazolinone Analogs Targeting CDK5 Kinase Activity and Glioblastoma Cell Proliferation. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 691. 10.3389/fchem.2020.00691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bihel F. J. J.; Justiniano H.; Schmitt M.; Hellal M.; Ibrahim M. A.; Lugnier C.; Bourguignon J. J. New PDE4 inhibitors based on pharmacophoric similarity between Papaverine and tofisopam. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 6567–6572. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siuciak J. A.; Chapin D. S.; Harms J. F.; Lebel L. A.; McCarthy S. A.; Chambers L.; Shrikhande A.; Wong S.; Menniti F. S.; Schmidt C. J. Inhibition of the striatum-enriched phosphodiesterase PDE10A: A novel approach to the treatment of psychosis. Neuropharmacology 2006, 51, 386–396. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellerano M.; Tcherniuk S.; Perals C.; Ngoc Van T. N.; Garcin E.; Mahuteau-Betzer F.; Teulade-Fichou M. P.; Morris M. C. Targeting Conformational Activation of CDK2 Kinase. Biotechnol. J. 2017, 12, 201600531 10.1002/biot.201600531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyressatre M.; Laure A.; Pellerano M.; Boukhaddaoui H.; Soussi I.; Morris M. C. Fluorescent Biosensor of CDK5 Kinase Activity in Glioblastoma Cell Extracts and Living Cells. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 15, 1–24. 10.1002/biot.201900474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombez L.; Aldrian-Herrada G.; Konate K.; Nguyen Q. N.; McMaster G. K.; Brasseur R.; Heitz F.; Divita G. A new potent secondary amphipathic cell-penetrating peptide for siRNA delivery into mammalian cells. Mol. Ther. 2009, 17, 95–103. 10.1038/mt.2008.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen T. P.; Peltier J.; Härtlova A.; Gierliński M.; Jansen V. M.; Trost M.; Björklund M. Thermal proteome profiling of breast cancer cells reveals proteasomal activation by CDK 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib. EMBO J. 2018, 37, 1–19. 10.15252/embj.201798359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C. C.; Park A. Y.; Guan J. L. In vitro scratch assay: A convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 329–333. 10.1038/nprot.2007.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Arnedo A.; Figueroa F. T.; Clavijo C.; Arbeláez P.; Cruz J. C.; Muñoz-Camargo C. An image J plugin for the high throughput image analysis of in vitro scratch wound healing assays. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0232565 10.1371/journal.pone.0232565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald W. J.; Baeder D. H. Pharmacology of ethaverine HC1: human and animal studies. South Med. J. 1975, 68, 1481–1484. 10.1097/00007611-197512000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritschel W. A.; Hammer G. V. Pharmacokinetics of papaverine in man. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Biopharm. 1977, 15, 227–228. 10.1097/00007611-197512000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H.; Kim H. S.; Lee S. J.; Kim K. T. Stabilization and activation of p53 induced by Cdk5 contributes to neuronal cell death. J. Cell Sci. 2007, 120, 2259–2271. 10.1242/jcs.03468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellerano M.; Naud-Martin D.; Mahuteau-Betzer F.; Morille M.; Morris M. C. Fluorescent Biosensor for Detection of the R248Q Aggregation-Prone Mutant of p53. ChemBioChem. 2019, 20, 605–613. 10.1002/cbic.201800531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebl J.; Weitensteiner S. B.; Vereb G.; Takács L.; Fürst R.; Vollmar A. M.; Zahler S. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 regulates endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 35932–35943. 10.1074/jbc.M110.126177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C.; Negash S.; Guo H. T.; Ledee D.; Wang H. S.; Zelenka P. CDK5 regulates cell adhesion and migration in corneal epithelial cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2002, 1, 12–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohshima T.; Gilmore E. C.; Longenecker G.; Jacobowitz D. M.; Brady R. O.; Herrup K.; Kulkarni A. B. Migration defects of cdk5(−/−) neurons in the developing cerebellum is cell autonomous. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 6017–6026. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-06017.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strock C. J.; Park J. I.; Nakakura E. K.; Bova G. S.; Isaacs J. T.; Ball D. W.; Nelkin B. D. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 activity controls cell motility and metastatic potential of prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 7509–7515. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisht S.; Nolting J.; Schütte U.; Haarmann J.; Jain P.; Shah D.; Brossart P.; Flaherty P.; Feldmann G. Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 5 (CDK5) Controls Melanoma Cell Motility, Invasiveness, and Metastatic Spread-Identification of a Promising Novel therapeutic target. Trans. Oncology 2015, 8, 295–307. 10.1016/j.tranon.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouclier C.; Simon M.; Laconde G.; Pellerano M.; Diot S.; Lantuejoul S.; Busser B.; Vanwonterghem L.; Vollaire J.; Josserand V.; et al. Stapled peptide targeting the CDK4/Cyclin D interface combined with Abemaciclib inhibits KRAS mutant lung cancer growth. Theranostics 2020, 10, 2008–2028. 10.7150/thno.40971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines E.; Chen T.; Kommajosyula N.; Chen Z.; Herter-Sprie G. S.; Cornell L.; Wong K. K.; Shapiro G. I. Palbociclib resistance confers dependence on an FGFR-MAP kinase-mTOR-driven pathway in KRAS-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 31572–31589. 10.18632/oncotarget.25803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Abreu M. T.; Palafox M.; Asghar U.; Rivas M. A.; Cutts R. J.; Garcia-Murillas I.; Pearson A.; Guzman M.; Rodriguez O.; Grueso J.; et al. Early adaptation and acquired resistance to CDK4/6 inhibition in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 2301–2313. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P.; Alessi D. R. Kinase Drug Discovery – What’s Next in the Field?. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 96–104. 10.1021/cb300610s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarnera E.; Berezovsky I. N. Allosteric sites: remote control in regulation of protein activity. Curr.Opin.Struct.Biol. 2016, 37, 1–8. 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong M.; Seeliger M. A. Targeting conformational plasticity of protein kinases. ACS Chem.Biol. 2015, 10, 190–200. 10.1021/cb500870a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroux A. E.; Biondi R. M. Renaissance of Allostery to Disrupt Protein Kinase Interactions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2020, 45, 27–41. 10.1016/j.tibs.2019.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.