Abstract

Two Epstein-Barr virus latent cycle promoters for nuclear antigen expression, Wp and Cp, are activated sequentially during virus-induced transformation of B cells to B lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) in vitro. Previously published restriction enzyme studies have indicated hypomethylation of CpG dinucleotides in the Wp and Cp regions of the viral genome in established LCLs, whereas these same regions appeared to be hypermethylated in Burkitt's lymphoma cells, where Wp and Cp are inactive. Here, using the more sensitive technique of bisulfite genomic sequencing, we reexamined the situation in established LCLs with the typical pattern of dominant Cp usage; surprisingly, this showed substantial methylation in the 400-bp regulatory region upstream of the Wp start site. This was not an artifact of long-term in vitro passage, since, in cultures of recently infected B cells, we found progressive methylation of Wp (but not Cp) regulatory sequences occurring between 7 and 21 days postinfection, coincident with the period in which dominant nuclear antigen promoter usage switches from Wp to Cp. Furthermore, in the equivalent in vivo situation, i.e., in the circulating B cells of acute infectious mononucleosis patients undergoing primary EBV infection, we again frequently observed selective methylation of Wp but not Cp sequences. An effector role for methylation in Wp silencing was supported by methylation cassette assays of Wp reporter constructs and by bandshift assays, where the binding of two sets of transcription factors important for Wp activation in B cells, BSAP/Pax5 and CREB/ATF proteins, was shown to be blocked by methylation of their binding sites.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a human gammaherpesvirus, is largely B lymphotropic and possesses a unique set of latent cycle genes whose coordinate expression can drive the proliferation of latently infected B cells. This process can be studied in vitro, where experimental infection of resting B cells leads to the outgrowth of virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) expressing the full range of EBV latent proteins; these include the nuclear antigens EBNA1, -2, -3A, -3B, -3C, and -LP and the latent membrane proteins LMP1, -2A, and -2B (25, 42). Immediately postinfection, viral transcription initiates from the latent cycle promoter Wp. The long primary transcripts thus produced are capable of generating all six EBNA mRNAs but appear to be preferentially, though not exclusively, processed to mRNAs encoding the EBNA2 and EBNA-LP proteins (2, 13, 62, 63). Their appearance leads to activation of an alternative upstream promoter, Cp, from which the full complement of EBNA proteins is expressed, as well as to activation of the more distant LMP promoters (1, 54, 60, 61, 67), thereby completing the full range of latent protein expression. The activation of Cp is followed by a gradual waning of Wp transcription such that Cp is dominant over Wp in most established LCLs (4, 63).

Virus-driven B-cell growth transformation is also observed in vivo during primary EBV infection. Thus, Wp, Cp, and LMP transcripts are detectable in the circulating B-cell pool of infectious mononucleosis (IM) patients (58). However, after resolution of the acute infection and establishment of a lifelong virus carrier state, virus-infected cells in the blood are only detectable within the resting memory B-cell pool (5, 32) and show a different program of viral transcription; in particular, Wp, Cp, and most if not all of the LMP promoters (with the possible exception of LMP2A) appear to be silent (41, 58). The mechanisms of promoter regulation which effect this switch to a more restricted form of virus latency are still not understood. However, some interesting potential clues have come from the study of EBV genome-positive malignancies, such as Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) and nasopharyngeal carcinoma, which also show more limited patterns of latent protein expression than do LCLs (42). In particular, Wp and Cp are silent in such tumors, and the only detectable EBNA, EBNA1, is expressed from a downstream EBNA1-specific promoter, Qp (48–50). Digestion of viral DNA from these tumors, using restriction enzymes that are either sensitive or insensitive to the presence of a methylated cytosine in the target sequence, indicated that several regions of the genome were more heavily methylated in tumor cells than in LCLs (3, 4, 11, 20, 22, 31, 51). These regions included the BamHI W and C fragments, within which Wp and Cp are situated, but not the region around Qp. Given the increasing evidence for methylation at CpG dinucleotides as a general mechanism of promoter silencing in eukaryotic cells (10), this raised the possibility that methylation of EBV latent promoters may be important in maintaining the restricted form of latency found in such tumors. This idea was indeed supported by earlier evidence that exposure of BL cell lines to 5′ azacytidine, an inhibitor of DNA methylation, was capable of rescuing EBNA2 and LMP1 expression in a proportion of cells (16, 30).

With the development of the more sensitive technique of bisulfite genomic sequencing, it is possible to examine the methylation statuses of all CpG dinucleotides within any selected region of DNA rather than only those present within restriction enzyme sites (14). In this context, it is known that Cp can be activated by the binding of EBNA1 to the upstream oriP element (40, 53) and by the binding of two cellular factors, CBF2 and the EBNA2-interacting protein RBP-Jκ/CBF1, to a more promoter-proximal EBNA2 response element (17, 19, 59, 66). While oriP remains unmethylated in BL and nasopharyngeal carcinoma tumor cells (12), Robertson et al. observed hypermethylation of a region of Cp encompassing the EBNA2 response element (46) and, in gel shift assays, showed that methylation of a particular CpG within that element abrogated CBF2 binding (45). This further implied that methylation is important in maintaining Cp in an inactive state in tumor cells. Whether methylation is coincident with, and therefore potentially involved in, the initial silencing of Cp in such cells remains an open question.

The present work describes similar studies in the context of Wp and takes advantage of two features of this promoter. One is the fact that promoter silencing can be followed in real time during the process of virus-induced B-cell transformation (63). The other is the recent identification of upstream regulatory sequences (7) which in reporter assays appear to be critical for Wp activity. These include a YY1 site within a region of the promoter responsible for its low baseline activity in a variety of cell lineages and, more importantly, binding sites for CREB family members (27), for RFX family members, and for the B-cell-specific activator protein BSAP/Pax5 (57a) within a region responsible for the promoter's high B-cell-specific activity. We noted that several of these sites contained CpG dinucleotides and were therefore potentially susceptible to the effect of methylation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tumor biopsy specimens, established cell lines, and recently-infected cells.

The tumor biopsy specimens Sav, Ava, Isa, and Ali were from patients with endemic EBV-positive BL from East Africa (18). The cell lines tested included an EBV-negative sporadic BL line, DG75; the EBV-positive endemic BL cell lines Rael, Jad, and Eze (in which EBV antigen expression is restricted to EBNA1); the EBV-producing marmoset LCL B95.8; three long-established human LCLs, XMW, WBW, and JY; and the human T-leukemic cell line Jurkat. All cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 2 mM glutamine. Before the cell lines were sampled for bisulfite sequencing analysis, the cells were grown for at least 2 weeks in the presence of 200 μM acyclovir in order to block any EBV genome replication in cells spontaneously entering the lytic cycle (28).

For the analysis of cells during EBV-induced transformation in vitro, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were prepared from buffy coat samples (Blood Transfusion Service, Birmingham, United Kingdom) and depleted of T cells by E-rosetting with AET-treated sheep erythrocytes (33). The T-cell-depleted preparations were then exposed to a concentrated B95.8 virus preparation, washed to remove any unbound virus, and plated at 107 cells/25-cm2 flask in culture medium containing 200 μM acyclovir. The cultures (split 1:1 where necessary once growth had begun) were harvested at the indicated times, and the cells were used to provide RNA for EBV transcription analysis and DNA for bisulfite genomic sequencing. The analysis of cells from the blood of IM patients used PBMCs that had been immediately cryopreserved from blood samples taken within 4 to 13 days of the onset of symptoms (58).

RNA extraction and RT-PCR analysis.

RNA was prepared from cell pellets with RNAzol B extraction reagent (Cinna-Biotex) and subjected to reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis. In brief, cDNA synthesis was carried out on 1 μg of RNA using EBV-specific 3′ primers and avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA was then amplified with primer sets specific for Wp-initiated transcripts, Cp-initiated transcripts, BamHI Y3/U/K-spliced EBNA transcripts initiating from Wp or Cp, BamHI Q/U/K-spliced EBNA1 transcripts initiating from Qp or the immediately upstream lytic cycle promoter Fp (36, 50), and BamHI FQ/U/K-spliced EBNA1 transcripts initiating from Fp, and then the PCR products were detected on Southern blots with radiolabeled probes as described previously (36, 58). Quantitation was carried out using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager.

Bisulfite genomic sequencing.

Genomic DNA prepared by standard methods was subjected to bisulfite genomic sequencing (14). Briefly, 10-μg aliquots of DNA were digested with EcoRI, denatured in 0.2 M sodium hydroxide for 10 min at room temperature, neutralized in 0.3 M sodium acetate, and ethanol precipitated. The DNA pellet was resuspended in 1.2 ml of freshly made 3.1 M sodium bisulfite–0.5 mM hydroquinone (pH 5), overlaid with mineral oil, and incubated for 20 h at 50°C. The bisulfite-modified DNA was then purified using Qiaquick columns (Qiagen), denatured, neutralized, precipitated, and resuspended in 50 μl of sterile deionized water. For each sample, 2-μl aliquots of bisulfite-modified and unmodified DNA were amplified in strand-specific PCRs with primers specific for the regulatory regions of the Cp and Wp promoters as shown in Table 1. Bisulfite-modified DNA was amplified for 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 90 s; unmodified DNA was amplified for 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 90 s. The cell line samples were amplified with one round of PCR using the inner set of primers, whereas for some of the tumor biopsy and IM patient samples, a nested-PCR approach was required to obtain sufficient PCR product for cloning. In these cases, DNA was amplified with the outer primers, and then one-fifth of this first-round PCR product was amplified in a second round with the appropriate inner primers. The PCR products were gel purified and cloned into Escherichia coli XL-1 Blue using the pGEM-T Easy vector system I (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA was made from individual bacterial colonies using the Wizard plus SV miniprep kit (Promega) and sequenced using the universal primer 5′-GTAAAACGACGGCCAGT (Amersham-Pharmacia).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for bisulfite genomic sequencing analysis

| Primer | Sequence | Coordinatesa |

|---|---|---|

| Cp 5′ outer | 5′-AGGGCGGCCTTGCGAACAATTATTAGTAGC | 10731–10760 |

| Cp 3′ outer | 5′-ACCACTTTAGACGTTGCTCCACCTCTAAGG | 11157–11128 |

| Cp modified outer 5′ | 5′-AGGGTGGTTTTGTGAATAATTATTAGTAGT | 10731–10760 |

| Cp modified outer 3′ | 5′-ACCACTTTAAACATTACTCCACCTCTAAAA | 11157–11128 |

| Wp 5′ outer | 5′-AAAGCGGGTGCAGTAACAGGTAATCTCTGG | 13971–14000 |

| Wp 3′ outer | 5′-CTCCTGGCGCTCTGATGCGACCAGAAATAG | 14399–14370 |

| Wp modified outer 5′ | 5′-AAAGTGGGTGTAGTAATAGGTAATTTTTGG | 13971–14000 |

| Wp modified outer 3′ | 5′-CTCCTAACACTCTAATACAACCAAAAATAA | 14399–14370 |

| Cp 5′ inner | 5′-AATGTGTCCCAATTAGAAACCC | 10839–10861 |

| Cp 3′ inner | 5′-TTGAGCTCTCTTATTGGCTATA | 11091–11070 |

| Cp modified inner 5′ | 5′-AATGTGTTTTAATTAGAAATTT | 10839–10861 |

| Cp modified inner 3′ | 5′-TTAAACTCTCTTATTAACTATA | 11091–11070 |

| Wp 5′ inner | 5′-GACACTTTAGAGCTCTGGAGGAC | 14023–14045 |

| Wp 3′ inner | 5′-CCCTCCCTAGAACTGACAATTGGC | 14335–14312 |

| Wp modified inner 5′ | 5′-GATATTTTAGAGTTTTGGAGGAT | 14023–14045 |

| Wp modified inner 3′ | 5′-CCCTCCCTAAAACTAACAATTAAC | 14335–14312 |

Genome coordinates are given with reference to the B95.8 genomic sequence (6).

Bandshift assays.

The preparation of nuclear extracts, the sequences of wild-type and mutant oligonucleotides used as bandshift probes, and the in vitro binding assay conditions have been described previously (7, 27; Tierney et al., submitted). Oligonucleotides incorporating 5-methylcytosine residues at specific CpG sites were synthesized by Alta Biosciences (University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom).

Methylation cassette assays.

Methylation cassette assays (43) were used to determine the effect of methylation of specific regulatory regions on Wp activity. Four types of cassette assay were carried out in which either the whole Wp regulatory region from −440 to +173 relative to the transcription start site, or the smaller regions −440 to −264, −264 to −170, and −170 to −16, were methylated in the context of an otherwise-unmethylated luciferase reporter vector. For each cassette assay, duplicate 20-μg aliquots of Wp440[NcoI]-GL2, a derivative of Wp 440-GL2 (7) in which an NcoI site had been introduced at −173 to −168 by site-directed mutagenesis, were digested overnight with 30 U of the appropriate enzymes, phenol-chloroform extracted, precipitated, and resuspended in 20 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer. One aliquot was methylated overnight at 37°C in a 30-μl reaction mixture with 10 U of SssI CpG methylase (New England Biolabs), 1× buffer 2 (New England Biolabs), and 160 μM S-adenosyl-methionine. The other aliquot (mock-methylated control) was treated in the same way except that the CpG methylase enzyme was omitted. The methylated and unmethylated cassette fragments and unmethylated vector fragments were gel purified using the Qiaquick gel extraction kit and eluted in 40 μl of sterile deionized water. The efficiency of the methylation reactions was confirmed by digestion of 1 μl of the methylated and mock-methylated vector fragments with 10 U of the methylation-sensitive enzyme SalI (Roche). The methylated or mock-methylated cassette fragments (10 μl) were then ligated back into 1 μl of the unmethylated vector in a 20-μl reaction mixture with 10 U of T4 DNA ligase (Roche). The efficiency of the ligation reaction was assessed by analysis of 1 μl of the ligation reaction mixture on a 1.5% agarose gel. The remainder of the ligation reaction mixtures were then cotransfected into 25 × 106 DG75 or Jurkat cells with 1 μg of β-galactosidase reporter plasmid using the DEAE-dextran method (47). The luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured as described previously (7), with the β-galactosidase values being used to normalize the luciferase data for variations in transfection efficiency.

RESULTS

Methylation status of Wp and Cp in BL and LCL cells in relation to promoter activity.

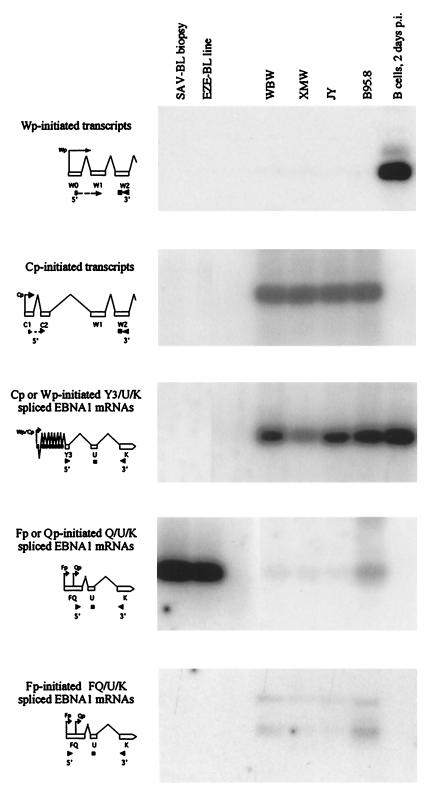

Prior to methylation analysis, we first sought to establish a panel of reference EBV-positive cells in which the activities of Wp and Cp were known. As representatives of cells in which both Wp and Cp were likely to be silent, we selected four endemic BL biopsy cell preparations (from the tumors Sav, Ava, Isa, and Ali) and three endemic BL cell lines; one was the long-established cell line Rael, which has been used in several earlier studies of this kind (11, 31, 51), and the other two (Jad and Eze) were recently established lines in early passage with the classical group I phenotype and restriction of EBV latent protein expression to EBNA1. Preparations of RNA from these cell populations and, as a reference, from normal B cells 2 days following EBV infection in vitro were amplified by RT-PCR using primers specific (i) for Wp-initiated transcripts, (ii) for Cp-initiated transcripts, (iii) for BamHI Y3/U/K-spliced EBNA1 transcripts initiating from Wp or Cp, (iv) for BamHI Q/U/K-spliced EBNA1 transcripts initiating from Qp or from the immediately upstream early lytic cycle promoter Fp, and (v) for the BamHI FQ/U/K-spliced EBNA1 transcript initiating from Fp (36, 50, 58); the products were then run out on a gel and blotted using the appropriate transcript-specific oligonucleotide probe. As shown by the representative samples in Fig. 1, this confirmed that both Wp and Cp were silent and that Qp was active in BL biopsy cells and in BL cell lines. Note that such BL cell populations showed no spontaneous entry of cells into the virus lytic cycle, and accordingly, all Q/U/K-spliced transcripts reflected Qp activity with no detectable contribution from the early lytic cycle promoter Fp. Figure 1 also shows the corresponding results from recently infected B cells and from the four long-established LCLs (including B95.8) selected for this work. While recently infected cells showed only Wp transcription, all four long-established lines displayed the classical pattern of preferential Cp usage with little or no detectable Wp activity. Cp usage was further reflected by the presence of Y3/U/K-spliced transcripts, whereas the very low levels of Q/U/K-spliced transcription in these LCLs (most obvious in B95.8) could be explained by lytic cycle-associated Fp activity.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of EBV transcription in a representative BL biopsy specimen, SAV; a recently established BL cell line, EZE; and four long-established LCLs, WBW, XMW, JY, and B95.8. Corresponding data for experimentally infected B cells (2 days postinfection) are included as a reference. Shown are the results of RT-PCR analysis using primer-probe combinations specific for Wp-initiated transcripts, Cp-initiated transcripts, Wp- or Cp-initiated Y3/U/K-spliced EBNA1 transcripts, Fp- or Qp-initiated Q/U/K-spliced EBNA1 transcripts, and Fp-initiated FQ/U/K-spliced EBNA1 transcripts. Note that Wp, Cp, and Qp are latent cycle promoters and Fp is a lytic cycle promoter.

We then used the method of bisulfite genomic sequencing to determine the methylation status of specific regions of the EBV genome in these cell populations, taking advantage of the fact that sodium bisulfite-hydroquinone modification of single-stranded DNA will convert cytosine residues to uracils while leaving methylcytosines intact. This treatment is followed by strand-specific PCR amplification of the genomic region of interest, cloning of the product, and sequencing of a number of derived clones. In all cases, the sequences were compared with those produced by a parallel amplification and cloning of unmodified DNA from the same cells. To ensure that the assay was detecting the episomal virus genome in latently infected cells and was not complicated by a background of newly replicated, unmethylated genomes from cells in the lytic cycle (55), all cell lines were grown in the presence of 200 μM acyclovir for 2 weeks prior to analysis in order to block viral DNA replication. The various BL and LCL cell populations were assayed as described above, focusing on a 313-bp sequence of Wp encompassing the main lineage-independent region and the B-cell-specific region of the promoter (7) and on a 253-bp sequence of Cp encompassing the EBNA2 response element (45).

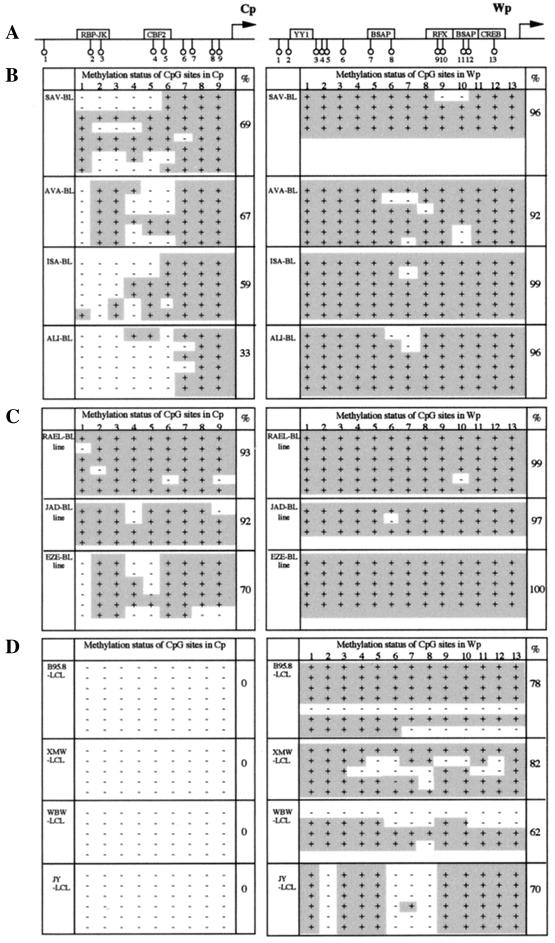

The results are presented in Fig. 2, showing for each cloned product the methylation status of each of the 13 CpGs within the Wp sequence and each of the 9 CpGs within the Cp sequence; note that Fig. 2A identifies the positions of these individual dinucleotides relative to known transcription factor binding sites in the two promoters. All the BL biopsy specimens (Fig. 2B) and the BL cell lines (Fig. 2C) showed almost-complete methylation in the Wp region, with the overall incidence of methylated CpGs ranging from 92 to 100% in the different tumor and cell line samples. This confirmed that the general methylation of BamHI W sequences apparent in BL cells from earlier studies using methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes (3, 11, 31) extends to the CpGs in the critical Wp regulatory region. Parallel analysis of Cp revealed less extensive but still significant methylation in this region (33 to 93% of CpGs were methylated), though interestingly, in contrast to an earlier bisulfite sequencing study of Cp in BL biopsy specimens (46), the critical CpG dinucleotide affecting CBF2 binding (CpG4 [Fig. 2A]) was methylated in less than 50% of sequenced clones from the biopsy specimens studied here. The most surprising observation from this work, however, came when we examined the Cp-using LCLs (Fig. 2D). While the Cp region was uniformly nonmethylated, as expected from earlier reports (11, 31, 51), we found substantial methylation of the Wp region (62 to 82% of CpGs were methylated) in all four cell lines.

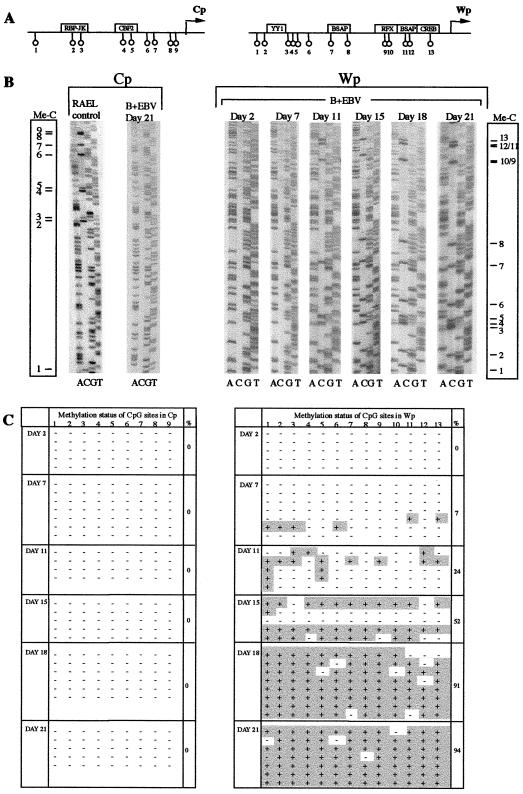

FIG. 2.

Methylation status of Cp and Wp regulatory regions in EBV-positive cells. (A) Diagram showing the main regulatory elements of Cp and Wp and the relative positions of CpG dinucleotides analyzed. (B, C, and D) Results of bisulfite sequencing of these regions in BL biopsy specimens (B), in BL cell lines (C), and in long-established LCLs (D). Several clones of the relevant PCR products were sequenced for each cell sample, and the individual CpG dinucleotides were identified as either methylated (+, shaded) or nonmethylated (−); the overall percentage of methylated CpGs per sample is shown.

Effect of methylation on binding of transcription factors to Wp sequences.

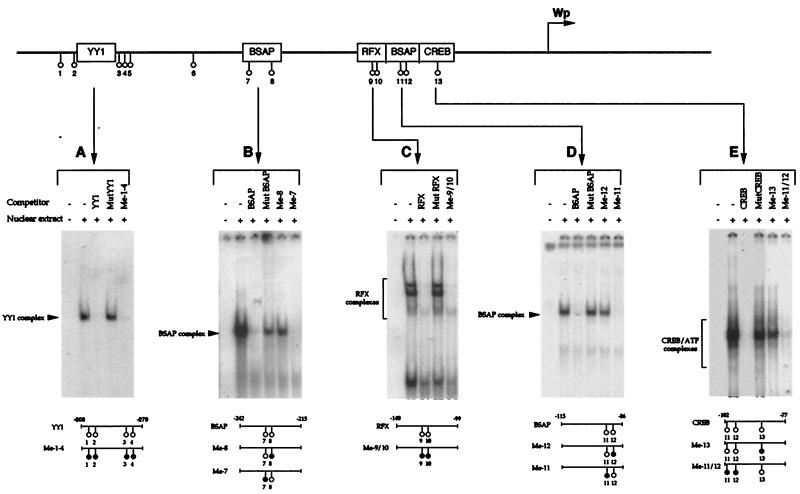

Methylation may inhibit transcription via a number of mechanisms, either by directly blocking the binding of transcription factors to DNA or through the mediation of methyl-CpG-binding proteins, which recruit histone deacetylases to the DNA, leading to remodeling of the chromatin into an inactive configuration (10). We therefore used recently developed bandshift assays (7, 27, 57a) to determine whether methylation of the relevant Wp oligonucleotide sequences affected transcription factor binding for each of the known sites in Wp. This was determined using the methylated derivatives as competitors of factor binding to a labeled wild-type probe; in each case the methylated sequence was compared with the wild-type competitor sequence and with a mutant sequence known to have lost binding activity.

The results of such assays are illustrated in Fig. 3. First, we examined YY1 binding within the lineage-independent region of Wp. Although there are no CpGs within the YY1 consensus binding motif itself, there are five CpGs in close proximity to the motif, four of which lie within the −308 to −279 oligonucleotide used to identify YY1 binding (7). As shown in Fig. 3A, a methylated version of the −308 to −279 oligonucleotide was able to compete for YY1 binding as efficiently as the wild-type competitor in this type of assay; therefore, methylation of the four CpG sites in close proximity to the YY1 site does not abrogate YY1 binding. The analysis was then extended to four individual sites in the B-cell-specific region of Wp which have been shown to bind the B-cell-specific activator protein BSAP/Pax5 (sites −242 to −215 and −115 to −86), RFX family proteins (−140 to −99), and CREB family proteins (−102 to −77). Both BSAP sites contain two CpG dinucleotides, and in both cases, methylation of one particular CpG abrogated factor binding. As shown by the relevant competitor assays using oligonucleotides methylated at a single CpG, the critical positions were CpG 8 in the promoter-distal BSAP site (Fig. 3B) and CpG 12 in the more proximal BSAP site (Fig. 3D). By contrast, the RFX site also contained two CpGs, but methylation at both positions did not affect the interaction with RFX proteins as measured in the competition assay (Fig. 3C). Finally, the binding of CREB/ATF family members was examined using the oligonucleotide probe −102 to −77. Note that this sequence overlaps the more promoter-proximal BSAP site and therefore includes CpGs 11 and 12 from that sequence, in addition to CpG 13. As shown in Fig. 3E, an oligonucleotide methylated at CpGs 11 and 12 was still able to compete effectively for CREB/ATF binding, whereas methylation at CpG 13 led to loss of competition. This work therefore identified CpGs 8, 12, and 13 in the Wp sequence as sites where methylation could block interaction with a relevant transcription factor, namely, BSAP in the cases of CpGs 8 and 12 and CREB/ATF proteins in the case of CpG 13.

FIG. 3.

Methylation sensitivity of transcription factor binding to Wp sequences in band shift assays. Shown are the results obtained for YY1 binding to the −308 to −279 probe (A), BSAP binding to the −242 to −215 probe (B), RFX binding to the −140 to −99 probe (C), BSAP binding to the −115 to −86 probe (D), and CREB binding to the −102 to −77 probe (E). In each case, the assays included a wild-type competitor, a mutant competitor sequence known to have lost transcription factor binding (7, 27, 57a), and derivatives of the wild-type sequence methylated at the CpG sites shown (●). The lanes showing assays conducted with labeled probes in the absence of the DG75 cell nuclear extract served as controls.

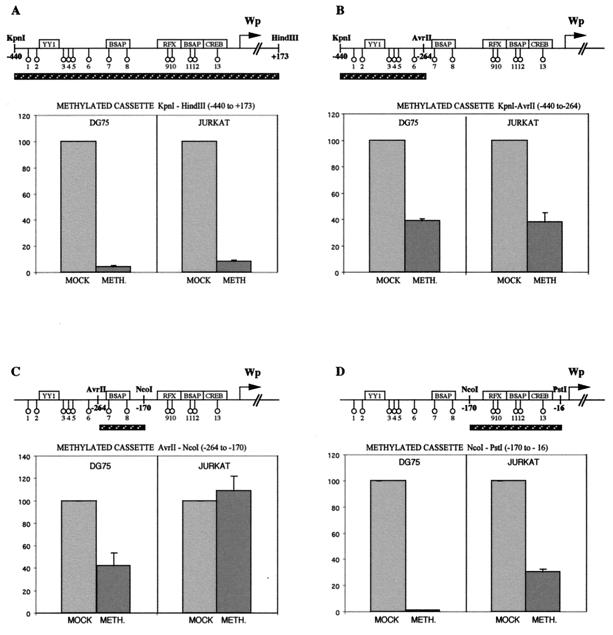

Effect of methylation on the activities of Wp reporter constructs.

The next set of experiments used a methylation cassette approach to examine the effect on promoter activity of methylating specific regions of Wp in a luciferase reporter construct carrying Wp sequences −440 to +173 relative to the transcription start site. All assays were conducted by transient transfection into a representative B-cell line, DG75, in which Wp is fully active, and into a representative non-B-cell line, Jurkat, in which Wp activity is regularly 10- to 20-fold lower (7). The results in Fig. 4 show the activities of the methylated constructs, in each case relative to that of a mock-methylated control construct tested in parallel in the relevant cell background.

FIG. 4.

Cassette replacement experiments to determine the effect of methylating individual regions of Wp sequence in the context of a Wp reporter. The methylated regions were nucleotides −440 to +173 (A), −440 to −264 (B), −264 to −170 (C), and −170 to −16 (D), in each case relative to the Wp transcription start site. The results are shown as histograms of mock-methylated (MOCK; set at 100% activity) versus cassette-methylated (METH.) reporter activities observed in the DG75 B-cell line and in the Jurkat T-cell line.

Methylation of the entire Wp sequence in a KpnI/HindIII cassette (−440 to +173) caused a >90% reduction in promoter activity in both DG75 and Jurkat cells (Fig. 4A), clearly indicating that Wp is sensitive to methylation in this type of in vitro assay. A series of shorter methylated cassettes were then constructed in order to look at the effect of methylating three separate regions of Wp sequence. Note that this involved the creation by site-directed mutagenesis of a unique NcoI site at −170, a change which did not affect Wp activity in either cell type (data not shown). Methylation of the KpnI/AvrII cassette (−440 to −264) containing CpG sites 1 to 6 caused a 60% reduction in Wp activity in both DG75 and Jurkat cells (Fig. 4B). The similarity of the effects in both cell types is consistent with the fact that here methylation was targeted to the lineage-independent region of the promoter. However, since the earlier bandshift assays suggested that YY1 binding to this region was unaffected by methylation (Fig. 3B), we infer that methylation of CpGs 1 to 6 may be reducing promoter activity through some other mechanism. The analysis then went on to focus on two separate areas of the B-cell-specific region of the promoter. Methylation of the AvrII/NcoI cassette (−264 to −170), containing two CpGs, both lying within the promoter-distal BSAP site, caused a 60% reduction in Wp activity in DG75 cells but did not affect activity in Jurkat cells (Fig. 4C). This is consistent with the observation that methylating CpG 8 can abrogate BSAP binding in gel shift assays (Fig. 3B) and also with the recent finding that mutation of this BSAP site leads to a 50 to 70% reduction in Wp activity in B-cell lines but does not affect the promoter's low baseline activity in non-B cells (57a). Finally, methylation of the NcoI/PstI cassette (−170 to −16) targeted CpGs 9 to 13 lying within the adjacent RFX, promoter-proximal BSAP, and CREB binding sites. As shown in Fig. 4D, this essentially abolished all promoter activity in DG75 cells and also caused a 70% inhibition of activity in Jurkat cells. We infer that at least some of the dramatic effect in DG75 cells reflects the abrogation of BSAP and CREB/ATF factor binding to their sites in this region (Fig. 3D and E), since mutations in either site are known to inhibit Wp activity in B cells (27, 57a). Some of the more modest inhibition seen in Jurkat cells may reflect the fact that CREB/ATF binding has a small but significant influence on Wp activity in this cell line (27).

Methylation status of Wp and Cp during virus-induced B-cell transformation in vitro.

Given the earlier evidence of Wp methylation in established Cp-using LCLs (Fig. 2D), we next carried out a time course study of Wp and Cp methylation status in relation to the usage of these promoters over a 4-week period following experimental infection of resting human B cells in vitro. Briefly, T-cell-depleted PBMCs from adult donors were exposed to a B95.8 virus preparation and then cultured in the presence of 200 μM acyclovir, and cells were harvested for DNA and RNA analysis at days 2, 7, 11, 15, 18, 21, and 28 of culture. In such experiments, foci of lymphoblastoid cells were apparent in infected (but not in uninfected control) cultures within the first week postinfection, and the first subculture could be made by days 7 to 10; thereafter, the emerging LCL could be subcultured 1:1 every 4 days.

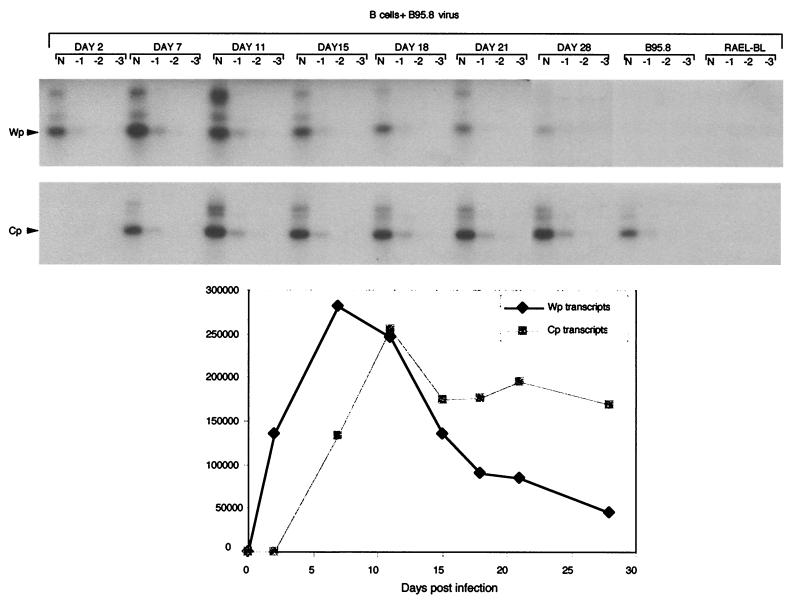

To monitor promoter usage during the time course of the experiment, we employed semiquantitative RT-PCR assays of Wp-initiated and Cp-initiated transcription. For this purpose, 10-fold dilutions of a cDNA preparation made from the infected cells using a W2 exon 3′ primer (common to both Wp and Cp transcripts) were amplified using this same 3′ primer and a Wp-specific or Cp-specific 5′ primer. Both PCR products were then detected on a Southern blot using an internal W2 probe, again common to both transcripts, and the signals were quantitated by phosphorimage analysis. Figure 5 shows the Southern blots and derived quantitative results from one such experiment. Wp-initiated transcripts were detectable by day 2 postinfection in the absence of any detectable Cp activity. By day 7, Wp transcription levels reached their peak, whereas Cp activity was still rising at that time to a maximum at day 11. Thereafter, Cp transcription levels stabilized while Wp levels fell progressively until they were barely detectable on the Southern blot by day 28. This general pattern of results is consistent with previous reports documenting the selective use of Wp in freshly infected cells followed by Wp-to-Cp switching during the process of LCL establishment (63). It is worth noting here that the level of Wp transcription measured on day 2 must derive only from that subpopulation of cultured cells which were actively infected at that time (estimated at 10 to 20% of the cells on the basis of EBNA-LP immunofluorescence staining [unpublished observations]), whereas transcripts detected at day 15 and beyond derive from cultures in which essentially every cell is infected. The level of Wp transcription per infected cell on day 2 relative to that on day 15 and beyond is therefore much greater than is first apparent from Fig. 5.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of Wp and Cp transcription in recently-infected B cells. Gels showing Wp- and Cp-specific RT-PCR signals, in each case obtained by amplifying neat (N) and 10 (−1)-, 100 (−2)-, and 1,000 (−3)-fold dilutions of W2-primed cDNA. Results are shown for B cells 2, 7, 11, 15, 18, 21, and 28 days postinfection, as well as for the B95.8 LCL and Rael-BL lines as controls. Shown below the gel are the quantitative results of signal intensity phosphorimage analysis.

We then used bisulfite genomic sequencing to monitor the methylation status of Wp and Cp in the same cells. Figure 6A and B shows representative sequencing gels and a summary of the results. As would be predicted from our earlier data (Fig. 2D), as well as from published findings on established LCLs (11, 31, 51), Cp remained unmethylated at all time points during the transformation process. By contrast, we observed progressive methylation of Wp sequences, first detectable at occasional CpGs by day 7 and almost complete by days 18 to 21. This same pattern of results was obtained in a second time course experiment involving the sequencing of a similar number of clones at each time point.

FIG. 6.

Methylation status of Cp and Wp regulatory regions in B cells 4 to 21 days following B95.8 EBV infection. (A) Diagram showing the main regulatory elements of Cp and Wp and the relative positions of CpG dinucleotides analyzed. (B) Representative sequencing gels of bisulfite-modified DNA for Cp in Rael BL cells versus B cells at 21 days postinfection (p.i.) and for Wp in B cells at 2, 7, 11, 15, 18, and 21 days p.i. The diagrams on the left and right of the gels indicate the expected positions of methylated cytosine in the C sequencing track. (C) Summarized results of bisulfite sequencing of the Cp and Wp regions presented as in Fig. 2.

Methylation status of Wp and Cp in B cells during primary infection in vivo.

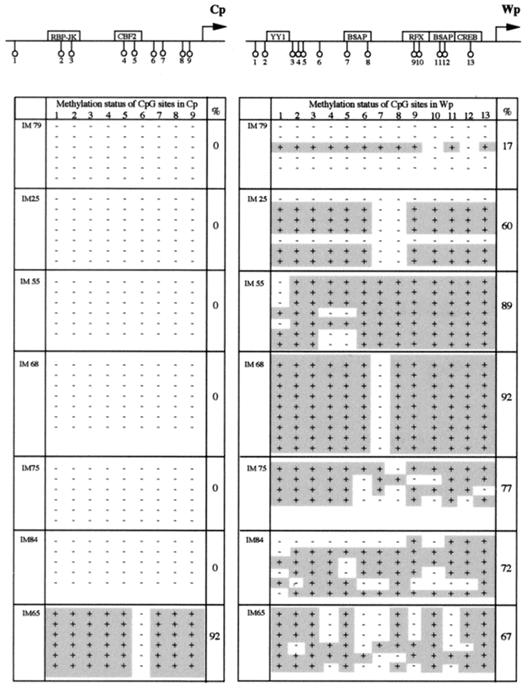

Previous studies have shown that during primary infection in vivo, as seen in acute IM patients, both Wp-initiated and Cp-initiated transcripts can be amplified from latently infected B cells in the blood (58), consistent with these cells being in the process of virus-driven growth transformation. We used bisulfite genomic sequencing to screen cryopreserved PBMC preparations from seven such IM patients, each bled within 4 to 13 days of the onset of clinical symptoms, and the results are summarized in Fig. 7. In six of seven patients we found that Cp sequences were completely unmethylated, whereas there was almost complete methylation at Cp in the remaining case. Importantly, however, there was evidence of Wp methylation in every case, and in six of seven patients this involved ≥60% of the CpG sites analyzed from each patient.

FIG. 7.

Methylation status of Cp and Wp regulatory regions in EBV-positive cells from the blood of seven individual IM patients. The data are presented as in Fig. 2.

DISCUSSION

Several earlier studies using methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes on EBV-positive tumors and established cell lines have shown a correlation between viral genome methylation in certain latent promoter regions and restricted patterns of latent gene expression (3, 11, 20, 22, 31, 51). These studies could not address whether methylation had occurred at the time of promoter silencing, in which case it might be a primary cause of transcriptional down-regulation, or had accrued later (26) as a means of maintaining the already-silenced state. In the present study, we have followed the methylation status of Wp during its natural down-regulation in vitro, as recently infected cells switch from Wp to Cp usage, and have focused on regions of Wp now known to contain key transcription factor binding elements. We chose the method of bisulfite genomic sequencing, since this allows all CpGs within the amplified regions to be analyzed rather than only those within restriction enzyme sites. Recent studies using this approach on tumor biopsies and cell lines have given a much more precise picture of CpG methylation status around the Qp, Cp, and LMP1 promoters (12, 46, 51, 56, 57) and have shown, for instance, that Cp silencing is not always accompanied by the type of blanket methylation of CpG sites (including that within the CBF2 binding sequence) initially inferred from restriction enzyme analysis (46). This result was in fact confirmed in the present work when, as an internal control, we analyzed the methylation of Cp sequences amplified from BL biopsy specimens and BL-derived cell lines (Fig. 2B and C). More importantly, Fig. 2 provides the first bisulfite sequence data on Wp methylation in tumor material and cell lines. Here, we were interested to note that the 13 CpGs in the 400 bp upstream of the transcription factor start site were not only consistently methylated in BL biopsy specimens and BL cell lines but also frequently methylated in established LCLs (Fig. 2D).

Such a result would not have been anticipated from earlier analyses of the BamHI W fragment in LCLs using the methylation-sensitive HpaII enzyme and its methylation-resistant isoschizomer, MspI. In these reports, although there was some heterogeneity in methylation patterns, the BamHI W region appeared to be significantly less methylated in LCLs than in BL lines (3, 11, 31). However, the HpaII enzyme is not informative about CpGs in the important 400-bp regulatory region of the promoter, and the only study to use the potentially more informative HhaI enzyme focused entirely on Wp in BL cell lines (22). It is worth noting here that, in order to simplify the interpretation of our initial screening assays on established LCLs, we confined our attention to cell lines showing classical Cp usage in the absence of detectable Wp activity; the situation in other established LCLs, where Cp is dominant but accompanied by persistent low-level Wp transcription (64), remains to be determined. We also were careful to study the cell lines after 2 weeks of maintenance in acyclovir, thereby ensuring that the analysis was not complicated by the presence of unmethylated progeny genomes produced by lytically infected cells in the culture (55). Such precautions over the choice and pretreatment of LCLs were not taken in earlier studies of BamHI W methylation by restriction enzyme analysis.

Recent work with reporter constructs, building on the initial studies of Jansson et al. (22), has identified several sites within a 400-bp region of Wp where the binding of cell transcription factors contributes to promoter activation. These include a YY1 site in a lineage-independent region of the promoter that is responsible for much of the low baseline activity of Wp in non-B cells and sites for BSAP, RFX family members, and CREB/ATF proteins which lie within the B-cell-specific region and which are all required for high-level promoter function in B cells (7, 27, 57a). We sought to determine whether methylation of CpGs in these areas might affect factor binding in in vitro bandshift assays and/or the activity of Wp reporter constructs in methylation cassette experiments. Such approaches showed that YY1 binding was not grossly affected by methylation, though we cannot rule out slight changes in affinity that would not have been detected in these particular assays, whereas cassette methylation of the lineage-independent region in toto caused a significant reduction of Wp activity in both B- and non-B-cell lines. Possibly methylation is affecting transcriptional activity by another route in these circumstances, perhaps by the recruitment of methyl-CpG-binding proteins to the DNA and induction of a more condensed configuration (10, 23, 34). Of the transcription factors conferring B-cell-specific activity, the binding of RFX proteins to their site (which contains two CpGs) was also unaffected by methylation; this is consistent with the literature on RFX proteins, which in some cases, as here, bind independently of methylation status and in others are selective for methylated sequence motifs (15, 52, 65). In contrast, the binding of BSAP to both its sites and of CREB/ATF proteins to their site was in each case abrogated by methylation of one particular CpG in the recognition sequence; this appears to be the first report of the methylation sensitivity of BSAP binding, whereas that of CREB/ATF binding is well documented in other contexts (21, 29). In line with earlier results from Wp constructs where individual binding sites in the B-cell-specific region had been mutated (7, 57a), cassette methylation of an AvrII/NcoI fragment of Wp which selectively targeted the more distal BSAP site caused a B-cell-specific impairment of promoter activity while methylation of the region containing the adjacent RFX, BSAP, and CREB binding sites caused a dramatic inhibition that was preferentially exerted in B cells. Collectively, these findings strongly suggest that methylation of Wp across the 400-bp regulatory region, were it to occur in the context of a viral infection, could contribute to promoter silencing.

Further experiments provide evidence that such methylation does occur in recently infected B cells at a time which is coincident with Wp-to-Cp switching. We first analyzed the growth transformation process in vitro; note that the precise kinetics of transformation will depend upon the virus dose as well as the particular conditions of B-cell culture, and even using the concentrated virus preparations employed here, there will be a degree of asynchrony at the single-cell level. Again, the cultures were maintained in the continual presence of acyclovir to avoid complications from recently infected cells entering the lytic cycle. Using semiquantitative RT-PCR assays of Wp and Cp transcription, we were able to show (in line with earlier reports [62, 63]) that Wp was activated first and reached its peak within the first week postinfection and then declined to much lower levels by days 21 to 28. By contrast, Cp was delayed in its activation and peaked slightly later but was maintained at a high level thereafter (Fig. 5). The important point is that, while Cp remained unmethylated throughout the process of LCL establishment, Wp became progressively methylated, with the first evidence of methylated residues appearing as early as day 7 and with >90% of CpGs affected by days 18 to 21 (Fig. 6).

Finally, we examined the methylation status of Wp and Cp in the circulating B cells of IM patients undergoing primary EBV infection. At this stage, the transient phase of virus-driven B-cell proliferation in vivo appears to be at its height, with latently infected LCL-like cells expressing the full spectrum of EBV latent proteins being detectable in blood and lymphoid tissues (35, 37, 58). In an earlier study from this laboratory, RT-PCR analysis of IM B cells using Wp- and Cp-specific assays of equal sensitivity showed strong expression of Cp transcripts in all 14 patients studied, whereas only 9 of 14 were positive for Wp transcripts, in many cases at barely detectable levels (58). This strongly suggests that the Wp-to-Cp transition is well advanced in the blood in many cases of acute IM. It is significant, therefore, that in the present work (Fig. 7) we observed extensive methylation of Wp but not Cp sequences in five of the seven patients studied and some methylation at Wp but not Cp in a sixth patient; the seventh patient showed methylation at both promoters, a pattern which other groups have found to be typical of latently infected cells in the memory B-cell pool of long-term virus carriers (38, 44). We could not quantitate Wp and Cp transcript levels in the PBMCs of these patients due to limitations of available cell numbers. However, the parallels between our present methylation analysis and our earlier transcriptional analysis, conducted on a different set of patients, strongly suggest that Wp down-regulation is coincident with methylation of the promoter in vivo just as it is in vitro.

In interpreting these findings, however, it is important to note that there are several (up to 10) copies of the Wp-containing BamHI W fragment in the EBV genome, constituting a large internal repeat which lies immediately downstream of the BamHI C fragment containing Cp (6). As in all earlier studies of Wp, our data on promoter methylation are therefore summative of all Wp copies in the resident EBV genome. The relevance of such studies might be questioned, therefore, if, as one result has implied (64), Wp transcription initiates mainly from the most 5′ copy of the promoter. This result, however, came from a highly unusual EBV recombinant in which Cp is defective and in which there are only two copies of Wp. The observation was that EBNA transcription in LCLs established using this recombinant virus came from the 5′ Wp copy, but the relative activities of the two Wp copies in freshly infected cells were never examined (64). It seems likely that in the early stages of B-cell infection with a wild-type virus, all copies of Wp are active; this is the most logical inference from the finding that EBNA-LP is hyperexpressed during transformation as a ladder of isoforms with different numbers of BamHI W-encoded repeat domains (13). In such circumstances, therefore, the mechanism of subsequent Wp down-regulation should apply to all copies of Wp. In any case, we would expect some 10% of our independently generated PCR clones to derive from the most 5′ Wp region. In that context, in successive in vitro transformation experiments, we have sequenced more than 35 Wp clones at later time points and have found that every one was methylated at the majority of CpG sites. This strongly suggests that all copies of Wp, including the most 5′ copy, are subject to methylation during transformation.

We would nevertheless stress that the temporal coincidence of Wp methylation and Wp-to-Cp switching during virus-induced B-cell transformation is merely consistent with, and cannot be interpreted as proof of, a causal relationship. It is possible that Wp is down-regulated by another primary mechanism, perhaps interference by transcription initiated at the upstream Cp (39, 40), and that this then rapidly induces methylation of the silenced promoters by de novo cellular DNA methylases (10). It may also be relevant that the BamHI W repeat region of the genome contains extensive potential secondary structure (24), a situation that appears to generate preferred substrates for methyltransferases (8, 9). Clearly, this methylation of Wp sequences does not spread to Cp in in vitro-transformed LCL cells, where the full pattern of latent gene expression is maintained. By contrast, methylation does eventually spread to Cp in at least some infected cells in vivo (38, 44). This almost certainly reflects the fact that additional physiological signals exist in vivo, probably linked to B-cell differentiation, which lead to Cp suppression and to the establishment of a reservoir of virus-carrying resting memory B cells. What the present work makes clear is that Wp methylation is a relatively early event in the process of B-cell transformation, occurring coincident with Wp-to-Cp switching, and that the ability to inhibit both transcription factor binding to Wp regulatory elements and Wp activity in reporter assays is consistent with an effector role for methylation in the silencing of this promoter.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

R.J.T. and H.E.K. contributed equally to this work.

We thank Debbie Williams for excellent secretarial help.

This work was funded by the Cancer Research Campaign, United Kingdom.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbot S D, Rowe M, Cadwallader K, Gordon J, Ricksten A, Rymo L, Rickinson A B. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA 2) induces expression of the virus-coded latent membrane protein (LMP) J Virol. 1990;64:2126–2134. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.2126-2134.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfieri C, Birkenbach M, Kieff E. Early events in Epstein-Barr virus infection of human B lymphocytes. Virology. 1991;181:595–608. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90893-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allday M J, Kundu D, Finerty S, Griffin B E. CpG methylation of viral DNA in EBV-associated tumours. Int J Cancer. 1990;45:1125–1130. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910450623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altiok E, Minarovits J, Li-Fu H, Conteras-Brodin B A, Klein G, Ernberg I. Host-cell-phenotype-dependent control of the BCR2/BWR1 promoter complex regulates the expression of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigens 2–6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:905–909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.3.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babcock G J, Decker L L, Volk M, Thorley-Lawson D A. EBV persistence in memory B cells in vivo. Immunity. 1998;9:395–404. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80622-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baer R, Bankier A T, Biggin M D, Deininger P L, Farrell P J, Gibson T G, Hatfull G, Hudson G S, Satchwell S C, Seguin C, Tuffnel P S, Barrell B G. DNA sequence and expression of the B95-8 Epstein-Barr virus genome. Nature. 1984;310:207–211. doi: 10.1038/310207a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell A I, Skinner J, Kirby H, Rickinson A B. Characterisation of regulatory sequences at the Epstein-Barr virus BamHI W promoter. Virology. 1998;252:149–161. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bender J. Cytosine methylation of repeated sequences in eukaryotes: the role of DNA pairing. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:252–256. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bestor T H, Tycko B. Creation of genome methylation patterns. Nat Genet. 1996;12:363–367. doi: 10.1038/ng0496-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bird A P, Wolffe A P. Methylation-induced repression—belts, braces and chromatin. Cell. 1999;99:451–454. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ernberg I, Falk K, Minarovits J, Busson P, Tursz T, Masucci M, Klein G. The role of methylation in the phenotype-dependent modulation of Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 2 and latent membrane protein genes in cells latently infected with Epstein-Barr virus. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:2980–3002. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-11-2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falk K, Szekely L, Aleman A, Ernberg I. Specific methylation patterns in two control regions of Epstein-Barr virus latency: the LMP1-coding upstream regulatory region and an origin of DNA replication (oriP) J Virol. 1998;72:2969–2974. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2969-2974.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finke J, Rowe M, Kallin B, Ernberg I, Rosen A, Dillner J, Klein G. Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies against Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen (EBNA5) detect multiple protein species in Burkitt lymphoma and lymphoblastoid cell lines. J Virol. 1987;61:3870–3878. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3870-3878.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frommer M, McDonald L E, Millar D S, Collis C M, Watt F, Griff G W, Molloy P L, Paul C L. A genomic sequencing protocol that yields a positive display of 5-methylcytosine residues in individual DNA strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1827–1831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia A D, Ostapchuk P, Hearing P. Methylation-dependent and independent DNA binding of nuclear factor EF-C. Virology. 1991;182:857–860. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90629-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregory C D, Rowe M, Rickinson A B. Different Epstein-Barr-virus (EBV) B cell interactions in phenotypically distinct clones of a Burkitt lymphoma cell line. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:1481–1495. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-7-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grossman S R, Johannsen E, Tong X, Yalamanchili R, Kieff E. The Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 transactivator is directed to response elements by the JK recombination signal binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7568–7572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Habeshaw G, Yao Q-Y, Bell A I, Morton D, Rickinson A B. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 sequences in endemic and sporadic Burkitt's lymphoma reflect virus strains prevalent in different geographic areas. J Virol. 1999;73:965–975. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.965-975.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henkel T, Ling P D, Hayward S D, Petersen M G. Mediation of Epstein-Barr virus EBNA2 transactivation by recombination signal-binding protein JK. Science. 1994;265:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.8016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu L-F, Minarovits J, Shi-Long C, Contreras-Salazar B, Rymo L, Falk K, Klein G, Ernberg I. Variable expression of latent membrane protein in nasopharyngeal carcinoma can be related to methylation status of the Epstein-Barr virus BNLF-1 5′ flanking region. J Virol. 1991;65:1558–1567. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1558-1567.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iguchi-Ariga S M M, Schaffner W. CpG methylation of the cAMP-responsive enhancer/promoter sequence TGACGTCA abolishes specific factor binding as well as transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 1989;3:612–619. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jansson A, Masucci M, Rymo L. Methylation of discrete sites within the enhancer region regulates the activity of the Epstein-Barr virus BamHI W promoter in Burkitt lymphoma lines. J Virol. 1992;66:62–69. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.62-69.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones P L, Veenstra G J, Wade P A, Vermaak D, Kass S U, Landsberger N, Strouboulis J, Wolffe A P. Methylated DNA and MeCP2 recruit histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nat Genet. 1998;19:187–191. doi: 10.1038/561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karlin S. Significant potential secondary structures in the Epstein-Barr virus genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:6915–6919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.18.6915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus and its replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 2343–2396. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kintner C, Sugden B. Conservation and progressive methylation of Epstein-Barr viral DNA sequences in transformed cells. J Virol. 1981;38:305–316. doi: 10.1128/jvi.38.1.305-316.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirby H, Rickinson A B, Bell A I. The activity of the Epstein-Barr virus BamHI W promoter in B cells is dependent on the binding of CREB/ATF factors. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:1057–1066. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-4-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin J-C, Smith M C, Pagano J S. Prolonged inhibitory effects of 9-(1,3-dihydroxy-2-propoxymethyl)guanine against replication of Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol. 1984;50:50–55. doi: 10.1128/jvi.50.1.50-55.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mancini D N, Rodenhiser D I, Ainsworth P J, O'Malley F P, Singh S M, Xing W, Archer T K. CpG methylation within the 5′ regulatory region of the BRCA1 gene is tumour-specific and includes a putative CREB binding site. Oncogene. 1998;16:1161–1169. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masucci M G, Contreras-Salazar B, Ragnar E, Falk K, Minarovits J, Ernberg I, Klein G. 5-Azacytidine up-regulates the expression of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA-2) through EBNA-6 and latent membrane protein in the Burkitt's lymphoma line Rael. J Virol. 1989;63:3135–3141. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.3135-3141.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minarovits J, Minarovits-Kormuta S, Ehlin-Henriksson B, Falk K, Klein G, Ernberg I. Host cell phenotype-dependent methylation patterns of Epstein-Barr virus DNA. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:1591–1599. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-7-1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyashita E M, Yang B, Babcock G J, Thorley-Lawson D. Identification of the site of Epstein-Barr virus persistence in vivo as a resting B cell. J Virol. 1997;71:4882–4891. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.4882-4891.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moss D J, Rickinson A B, Pope J H. Long-term T-cell-mediated immunity to Epstein-Barr virus in man. I. Complete regression of virus-induced transformation in cultures of seropositive donor leukocytes. Int J Cancer. 1978;22:662–668. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910220604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nan X, Ng H N, Johnson C A, Laherty C D, Turner B M, Eisenman R N, Bird A. Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature. 1998;393:386–389. doi: 10.1038/30764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niedobitek G, Herbst H, Young L S, Brooks L, Masucci M G, Crocker J, Rickinson A B, Stein H. Patterns of Epstein-Barr virus infection in non-neoplastic lymphoid tissue. Blood. 1992;79:2520–2526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nonkwelo C, Skinner J, Bell A I, Rickinson A B, Sample J. Transcription start sites downstream of the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) Fp promoter in early-passage Burkitt lymphoma cells define a fourth promoter for expression of the EBV EBNA-1 protein. J Virol. 1996;70:623–627. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.623-627.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pallesen G, Hamilton-Dutoit S J, Rowe M, Young L S. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus latent gene products in tumour cells of Hodgkin's disease. Lancet. 1991;337:320–322. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90943-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paulson E J, Speck S H. Differential methylation of Epstein-Barr virus latency promoters facilitate viral persistence in healthy seropositive individuals. J Virol. 1999;73:9959–9968. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.9959-9968.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puglielli M T, Desai N, Speck S H. Regulation of EBNA gene transcription in lymphoblastoid cell lines: characterization of sequences downstream of BCR2 (Cp) J Virol. 1997;71:120–128. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.120-128.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Puglielli M T, Woisetschlaeger M, Speck S H. oriP is essential for EBNA gene promoter activity in Epstein-Barr virus-immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines. J Virol. 1996;70:5758–5768. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.5758-5768.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qu L, Rowe D T. Epstein-Barr virus latent gene expression in uncultured peripheral blood lymphocytes. J Virol. 1992;66:3715–3724. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.6.3715-3724.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rickinson A B, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 2397–2446. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robertson K D, Ambinder R F. Mapping promoter regions that are hypersensitive to methylation-mediated inhibition of transcription: application of the methylation cassette assay to the Epstein-Barr virus major latency promoter. J Virol. 1997;71:6445–6454. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6445-6454.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robertson K D, Ambinder R F. Methylation of the Epstein-Barr virus genome in normal lymphocytes. Blood. 1997;90:4480–4484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robertson K D, Hayward S D, Ling P D, Samid D, Ambinder R F. Transcriptional activation of the Epstein-Barr virus latency C promoter after 5-azacytidine treatment: evidence that demethylation at a single CpG site is crucial. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6150–6159. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robertson K D, Manna A, Swinnen L J, Zong J C, Gulley M L, Ambinder R F. CpG methylation of the major Epstein-Barr virus latency promoter in Burkitt's lymphoma and Hodgkin's disease. Blood. 1996;88:3129–3136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sample J, Brooks L, Sample C, Young L, Rowe M, Gregory C, Rickinson A, Kieff E. Restricted Epstein-Barr virus protein expression in Burkitt lymphoma is due to a different Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 1 transcriptional initiation site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6343–6347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schaefer B C, Woisetschlaeger M, Strominger J L, Speck S H. Exclusive expression of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 in Burkitt lymphoma arises from a third promoter, distinct from the promoters used in latently infected lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6550–6554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schaefer B C, Strominger J L, Speck S H. Redefining the Epstein-Barr virus-encoded nuclear antigen EBNA-1 gene promoter and transcription in group I Burkitt lymphoma cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10565–10569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schaefer B C, Strominger J L, Speck S H. Host-cell-determined methylation of specific Epstein-Barr virus promoters regulates the choice between distinct viral latency programs. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:364–377. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sengupta P K, Ehrlich M, Smith B D. A methylation-responsive MDBP/RFX site in the first exon of the collagen α2(I) promoter. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36649–36655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sugden B, Warren N. A promoter of Epstein-Barr virus that can function during latent infection can be transactivated by EBNA1, a viral protein required for viral DNA replication during latent infection. J Virol. 1989;63:2644–2649. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.6.2644-2649.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sung N S, Kenney S, Gutsch D, Pagano J S. EBNA2 transactivates a lymphoid-specific enhancer in the BamHI C promoter of Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol. 1991;65:2164–2169. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2164-2169.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Szyf M, Eliasson L, Mann V, Klein G, Raizin A. Cellular and viral DNA hypomethylation associated with induction of Epstein-Barr virus lytic cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:8090–8094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tao Q, Robertson K D, Manns A, Hildesheim A, Ambinder R F. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in endemic Burkitt's lymphoma: molecular analysis of primary tissue. Blood. 1998;91:1373–1381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tao Q, Robertson K D, Manns A, Hildesheim A, Ambinder R F. The Epstein-Barr virus major latent promoter Qp is constitutively active, hypomethylated, and methylation sensitive. J Virol. 1998;72:7075–7083. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7075-7083.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57a.Tierney R, Kirby H, Nagra J, Rickinson A, Bell A. The Epstein-Barr virus promoter initiating B-cell transformation is activated by RFX proteins and the B-cell-specific activator protein BSAP/Pax5. J Virol. 2000;74:10458–10467. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.22.10458-10467.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tierney R J, Steven N, Young L S, Rickinson A B. Epstein-Barr virus latency in blood mononuclear cells: analysis of viral gene transcription during primary infection and in the carrier state. J Virol. 1994;68:7374–7385. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7374-7385.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Waltzer L, Logeat F, Brou C, Israel A, Sargeant A, Manet E. The human Jκ recombination signal sequence binding protein (RBP-Jκ) targets the Epstein-Barr virus EBNA2 protein to its DNA responsive elements. EMBO J. 1994;13:5633–5638. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06901.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang F, Tsang S-F, Kurilla M G, Cohen J J, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 transactivates latent membrane protein LMP1. J Virol. 1990;64:3407–3416. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.7.3407-3416.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Woisetschlaeger M, Jin X W, Yandava C N, Furmanski L A, Strominger J L, Speck S H. Role for the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 in viral promoter switching during initial stages of infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3942–3946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Woisetschlaeger M, Strominger J L, Speck S H. Mutually exclusive use of viral promoters in Epstein-Barr virus latently infected lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6498–6502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Woisetschlaeger M, Yandava C N, Furmanski L A, Strominger J L, Speck S H. Promoter switching in Epstein-Barr virus during the initial stages of infection of B lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1725–1729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yoo L I, Mooney M, Puglielli M T, Speck S H. B cell lines immortalized with an Epstein-Barr virus mutant lacking the Cp EBNA2 enhancer are biased towards utilization of the oriP-proximal EBNA gene promoter Wp1. J Virol. 1997;71:9134–9142. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9134-9142.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang X Y, Asiedu C K, Supakar P C, Khan R, Ehrlich K C, Ehrlich M. Binding sites in mammalian genes and viral gene regulatory regions recognised by methylated DNA binding protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6253–6260. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.21.6253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zimber-Strobl U, Strobl L J, Meitinger C, Hinrichs R, Sakai T, Furukawa T, Hong T, Bornkamm G W. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 exerts its transactivating function through interaction with recombination signal binding protein RBP-Jκ, the homologue of Drosophila suppressor of hairless. EMBO J. 1994;13:4973–4982. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06824.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zimber-Strobl U, Suentzenich K-O, Laux G, Eick E, Cordier M, Calender A, Billaud M, Lenoir G M, Bornkamm G W. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 activates transcription of the terminal protein gene. J Virol. 1991;65:415–423. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.415-423.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]