Abstract

Using the simian immunodeficiency virus/human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV)-macaque model of AIDS, we had shown in a previous report that a live, nonpathogenic strain of SHIV, further attenuated by deletion of the vpu gene and inoculated orally into adult macaques, had effectively prevented AIDS following vaginal inoculation with pathogenic SHIVKU. Examination of lymph nodes from the animals at 18 weeks postchallenge had shown that all six animals were persistently infected with challenge virus. We report here on a 2-year follow-up study on the nature of the persistent infections in these animals. DNA of the vaccine virus was present in the lymph nodes at all time points tested, as far as 135 weeks postchallenge. In contrast, the DNA of SHIVKU became undetectable in one animal by week 55 and in three others by week 63. These four macaques have remained negative for SHIVKU DNA as far as the last time point examined at week 135. Quantification of the total viral DNA concentration in lymph nodes during the observation period showed a steady decline. All animals developed neutralizing antibody and cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte responses to SHIVKU that persisted throughout the observation period. Vaccine-like viruses were isolated from two animals, and a SHIVKU-like virus was isolated from one of the two macaques that remained positive for SHIVKU DNA. There was no evidence of recombination between the vaccine and the challenge viruses. Thus, immunization with the live vaccine not only prevented disease but also contributed to the steady decline in the virus burdens in the animals.

Despite the pressing need for a vaccine against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), evaluation of the efficacy of any vaccine candidate in human beings will require several years of observation. The reasons for this are that the incubation period and the clinical course of HIV-induced disease are both unpredictably variable and that the immunological correlates of protection against HIV infection and/or disease are not known (16). Evaluation of the concept that a vaccine against HIV could be developed despite the formidable biological properties of this virus has been greatly expedited using macaque models of HIV pathogenesis (5, 6, 8, 9, 22, 23). Use of the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) model has pioneered this field and demonstrated that deletion of accessory genes from genomes of pathogenic viruses greatly attenuated the virulence of the latter agents and that use of such viruses as live vaccines induced protection against disease caused by pathogenic strains of SIV (10–13, 31). The SIV/HIV (SHIV)-macaque model was created on the rationale that this virus is biologically closer to HIV than to SIV because it has the envelope of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) (17). Use of the SHIV-macaque system to model vaccine efficacy required the availability of a predictably pathogenic strain of SHIV that could serve as challenge. SHIVKU satisfied this condition because it not only causes both the loss of CD4+ T cells and AIDS but it is also pathogenic after inoculation on the vaginal mucosal surface, thus providing a model of sexually transmitted HIV. Following leads on vaccine development in the SIV system, we deleted the accessory gene vpu from a strain of nonpathogenic SHIV and used this virus as a vaccine to test the concept that an orally inoculated vaccine could induce protection against AIDS caused by vaginally inoculated pathogenic SHIVKU (10).

In a previous report we had shown that orally inoculated vaccine virus, ΔvpuSHIVPPc (V-II), caused a transiently productive subclinical systemic infection in all of the macaques and that that this resulted in infection and establishment of vaccine virus DNA in the lymph nodes of the animals. Intravaginal challenge of the six immunized and four nonimmunized animals with SHIVKU resulted in infection in all 10 animals with this virus. However, whereas the nonimmunized animals rapidly developed productive infection followed by the onset of AIDS, the infection with SHIVKU in the six immunized animals was maintained at a minimally productive level that had no pathological effects. Nevertheless, DNA of challenge virus persisted in the lymph nodes of all six animals when examined at 18 weeks postchallenge (10).

In this study we report on the nature of the persistent infection caused by the two viruses. All six immunized animals have remained healthy, and all developed and maintained strong antibody and cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses against both viruses. DNA of the vaccine virus has persisted in lymph nodes of all six animals throughout the observation period. However, whereas the DNA of the challenge virus was also present in all six animals at 18 weeks postchallenge, concentrations of this DNA in the animals progressively decreased with time, and by 63 weeks postchallenge it had become undetectable in four of the six animals. This suggested that the immunization had not only prevented AIDS but also contributed to the gradual decline in the level of challenge virus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Amplification of vpu/gp120 sequences for detection of viral sequences in DNA isolated from PBMC and lymph node.

DNA was isolated from lymph node tissue or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) as previously described (10). The vpu/gp120 regions of viral genomes were amplified by nested PCR that produces fragments diagnostic for either vaccine virus DNA or challenge virus DNA as previously described (10). After the second round of amplification, challenge virus DNA, which has an intact vpu gene, yields a fragment of 431 bp, while vaccine virus DNA yields a fragment of 371 bp. Amplification of each sample was repeated four times in separate reactions to ensure accuracy. This assay is capable of detecting one viral genome in 103 cells. Detection of viral sequences using a nested PCR assay specific for challenge virus DNA was accomplished as described above. However, for the second round of PCR the antisense oligonucleotide primer used was 5′-CACAAAATAGAGTGGTGGTTGCTTCCT-3′. This primer is complementary to nucleotides 6361 to 6387 of the HIV (HxB2) genome. This region corresponds to the vpu gene and is present in the challenge virus SHIVKU but is absent from the vaccine virus (ΔvpuSHIVPPc). Thus, when this oligonucleotide is used in the assay described above, challenge virus DNA yields a fragment of 197 bp after the second round of amplification, while vaccine virus DNA does not yield any detectable fragment. This assay is capable of detecting one viral genome in 104 cells.

Virus recovery from lymph nodes.

Lymph node cells were obtained from mesenteric lymph node tissue, and CD4+ cells were negatively selected using immunomagnetic beads as previously described (9). The CD4+ cells were counted and stimulated with phytohemagglutinin (1 μg/ml) for 48 h, and 2 × 106 cells were cocultured with 106 C8166 indicator cells. After cocultivation for 7 days, the cultures were examined for cytopathic effect (CPE). Cells and supernatant from cultures exhibiting CPE were pooled and used to inoculate fresh C8166 cells. DNA from infected cultures was then isolated using a QIAAMP kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) according to the directions provided by the manufacturer.

Amplification of gp120 and nef sequences for sequencing.

PCR amplifications of gp120 and nef sequences were performed as previously described (27). Three separate amplifications were performed for each isolate. PCR products from each amplification reaction were purified on an agarose gel and cloned in PGEM-T (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Plasmids containing gp120 and nef were sequenced using the Bigdye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase, FS (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Reactions were run utilizing an Applied Biosystems 377 Prism XL automated DNA sequencer. Sequences from the 5′ and 3′ ends were determined with T7 and SP6 primers. Internal sequences were determined using primers 7265 (5′-CTCCCTGGTCCTCTCTGG-3′) and 7181 (5′-TAAAACCATAATAGTACAGC-3′). Challenge virus DNA was distinguished from vaccine virus DNA by the deletion in vpu. A minimum of one clone from each of the three separate amplifications of DNA from each viral isolate was sequenced. Consensus sequences are based on a minimum of three independently derived clones.

Lymphocyte proliferation assay.

PBMC from different macaques were cultured in triplicate in the presence or absence of UV-irradiated and heat-inactivated SHIVKU for 4 days (14). Cells were then pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine for 18 h before being subjected to scintillation spectroscopy. Stimulation indices were calculated as mean counts per minute (cpm), i.e., the cpm in stimulated wells/mean cpm in control wells.

Generation of bulk CTL population and chromium release assay.

CTL activity was determined as described elsewhere (14, 15, 28). Briefly, CTL effectors were prepared by stimulating PBMC from different macaques with UV-irradiated autologous CD4+ T cells infected with SHIVKU. Targets were autologous CD4+ T cells infected with SHIVKU or autologous B cells infected with recombinant vaccinia virus expressing HIVenv, SIVgag, or SIVpol and then labeled with 51Cr. Effector/target ratios ranging from 100:1 to 10:1 were used in a 4-h chromium release assay. The percent specific cytoxicity was calculated as follows: [(test release − spontaneous release)/(maximum release − spontaneous release)] × 100.

Quantitative PCR of viral DNA.

Quantification of viral DNA in tissue samples was performed using a modification of a procedure described previously (25).

Serum neutralization assay.

Neutralizing antibody titer in plasma was determined as previously described (10). Briefly, twofold serial dilutions of heat-inactivated plasma were prepared in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 5 mM NaHCO3 and 50 μg of gentamicin (R-10) per ml in quadruplicate in a flat-bottom 96-well plate. Suspensions of eight 50% tissue culture infective doses of either VII or SHIVKU virus in R-10 were added to each well, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h, followed by the addition of 104 C8166 cells to each well. After 1 week of incubation at 37°C, each well was scored for CPE, and the 50% neutralization titer was calculated by the Karber method (10).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequence data reported here have been assigned GenBank accession no. AY006474 (VPEy-gp120), AY006476 (VPEy-Nef), AY006472 (SHIVKU/8124-gp120), AY006475 (SHIVKU/8124-Nef), AY006473 (VPWl-gp120), and AY006477 (VPWl-Nef).

RESULTS

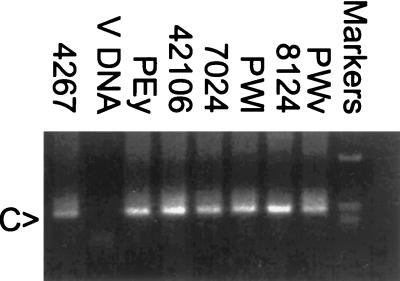

As reported previously (10), the vaccine virus, V-II (ΔvpuSHIVPPc), had replicated productively in all six animals tested after oral inoculation. This productive phase of infection lasted 10 to 12 weeks, after which virus replication became restricted, as indicated by a lack of detectable infection in PBMC after this period. The animals were challenged vaginally with SHIVKU 7 months after immunization. Infectious PBMC were sporadically detected in four of the animals during the first-20-week postchallenge period but, beyond this time point, virus was not isolated again for the duration of the observation period of 135 weeks. Viral RNA in plasma has been below the limit of detection throughout the observation period (results not shown). Analysis of DNA from lymph node biopsies at 18 weeks postchallenge showed a full-length vpu gene in all six animals, indicating that all animals had become infected with challenge virus. Further, a nested PCR assay, using an oligonucleotide primer whose sequence is complementary to a region of vpu found only in challenge virus DNA, confirmed that all animals were infected with SHIVKU (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

PCR detection of challenge virus DNA in the lymph nodes of animals inoculated with VII and challenged with SHIVKU. At week 18 postchallenge, lymph node biopsies were performed, and DNA was isolated and then amplified using a nested-PCR assay specific for DNA from SHIVKU. Aliquots of the PCR were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel, and DNA was visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Lanes: 1, amplification of DNA isolated from lymph node of the control animal 4267; 2, amplification of V-DNA; 3 to 8, amplification of DNA isolated from the lymph nodes of animals PEy, 42106, 7024, PWl, 8124, and PWv, respectively; 9, 1-kb molecular size marker. The arrow on the left marked C indicates the positions of the fragments amplified from C-DNA.

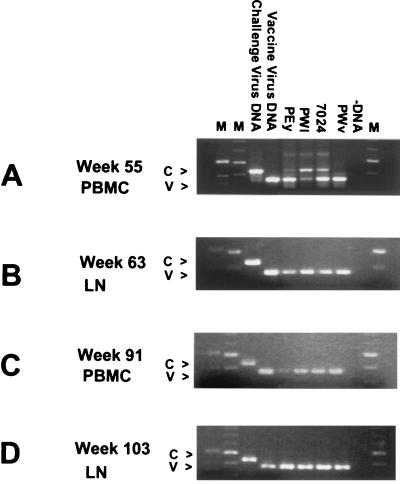

Using PCR primers that distinguish between the full-length and truncated vpu genes of challenge and vaccine viruses, respectively, we examined PBMC or lymph nodes of the animals at four intervals between weeks 55 and 103 postchallenge to determine the identity of the virus DNA present at these periods. Two animals, 8124 and 42106, showed the presence of DNA from both vaccine and challenge viruses throughout the monitoring period (Table 1 and data not shown). The DNA PCR data from the other four animals are shown in Fig. 2 and are summarized in Table 1. The data showed that the DNAs of both viruses were present in three of the four animals at week 55. The fourth animal, PWv, showed the presence of only vaccine virus DNA (V-DNA) at this time point, even though challenge virus DNA (C-DNA) had been detected at week 18 (10). Examination of lymph nodes biopsied at week 63 showed that challenge virus DNA had become undetectable in three additional animals, PEy, PWl, and 7024. Examination of lymph nodes biopsied at week 103 showed results identical to those seen at week 63, confirming that challenge virus DNA had become undetectable in four of the six animals. Quantitative analysis of viral DNA concentrations in lymph nodes using real-time PCR demonstrated that total viral DNA concentrations declined in all six animals between weeks 63 and 135 (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Detection of V-DNA and C-DNA and virus recovery in macaques immunized with vaccine II and challenged with SHIVKU

| Macaque | Viral DNA ina:

|

Identity of recovered virusb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBMC (wk 55) | Lymph node (wk 63) | PBMC (wk 91) | Lymph node (wk 103) | ||

| PEy | C/V | V | V | V | V |

| PWl | C/V | V | V | V | V |

| 7024 | C/V | V | V | V | NR |

| PWv | V | V | V | V | NR |

| 42106 | C/V | C/V | C/V | C/V | NR |

| 8124 | C/V | C/V | C/V | C/V | C |

C/V, V-DNA and C-DNA; V, V-DNA only; C, C-DNA only.

Virus recovery was performed at week 63. NR, no virus could be recovered at week 63.

FIG. 2.

PCR analysis of viral sequences present in PBMC and lymph nodes of animals inoculated with VII and challenged with SHIVKU. Lymph node biopsies and PBMC isolations were performed, DNA isolated, and then amplified using nested PCR. Aliquots of the PCR were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel, and DNA was visualized by ethidium bromide staining. (A) PCR analysis of DNA isolated from PBMC 55 weeks after challenge. Lanes: 1, 1-kb molecular size marker; 2, 100-bp molecular size marker; 3, challenge virus-positive control; 4, vaccine virus-positive control; 5 to 8, amplification of DNA from animals PEy, PWl, 7024, and PWv, respectively; 9, −DNA control; 10, 100-bp molecular size marker. Arrows on the left marked V or C indicate the positions of DNA fragments amplified from vaccine virus or challenge virus, respectively. (B) PCR analysis of DNA isolated from lymph node tissue 63 weeks after challenge. Lanes are in the same order as in panel A. (C) PCR analysis of DNA isolated from PBMC 91 weeks after challenge. Lanes are in the same order as in panel A. (D) PCR analysis of DNA isolated from lymph node 103 weeks after challenge. Lanes are in the same order as in panel A.

TABLE 2.

Viral DNA loads (SHIV DNA copies/105 cell equivalents) in vaccinated macaques

| Time postchallenge (wk) | SHIV DNA copies/105 cell Eq in macaque:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEy | PWl | 7024 | PWv | 42106 | 8124 | |

| 63 | 2,600 | 20,000 | 5,800 | 12,000 | 700 | 250 |

| 103 | 2,900 | 2,600 | 5,100 | 1,100 | 980 | 3,900 |

| 135 | 10 | 550 | –a | 1,100 | 36 | 53 |

This animal died at 117 weeks postchallenge of causes unrelated to SHIV infection.

Virus isolation attempts were performed on lymph node cells after depletion of CD8+ T cells and activation of the remainder with mitogen, followed by cocultivation with indicator cell cultures. Using this method, at week 63, we isolated vaccine-like virus from animals PWl and PEy and challenge-like virus from animal 8124. Infectious virus could not be isolated from lymph node tissue of animal 7024, PWv, or 42106. These data are summarized in Table 1.

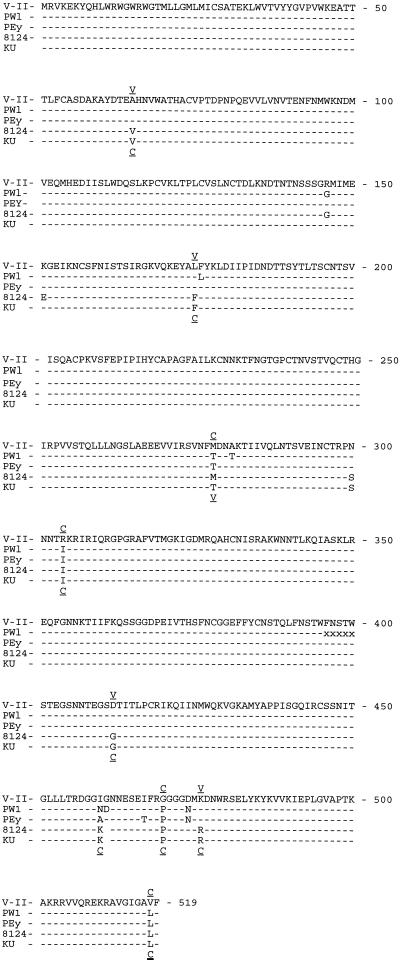

Sequence analysis of the vpu/gp120 region of the viruses recovered from animals PWl and PEy (VPWl and VPEy, respectively) demonstrated that they have the vpu deletion and gp120 sequences characteristic of vaccine virus. Examination of Fig. 3 shows that there are 10 and 7 amino acid differences in VPWl-gp120 and VPEy-gp120, respectively, compared to the corresponding sequence of the vaccine virus that was used for inoculation. In VPWl-gp120 there was also a deletion of five amino acids which had been caused by the elimination of one copy of a directly repeated nucleotide sequence. Four of these amino acid replacements are identical in VPEy-gp120 and VPWl-gp120 (M278T, R3041, G470P, and D474N). The amino acid changes at amino acids 278, 304, and 470 resulted in the replacement of an amino acid characteristic of vaccine virus with an amino acid characteristic of challenge virus. Interspersed among these changes were amino acids characteristic of vaccine virus (i.e., at amino acids 65, 175, 412, and 476). Thus, it is much more likely that the amino acid changes were caused by a constellation of amino acid replacements rather than by recombination events between challenge virus and vaccine virus.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the consensus amino acid sequences of gp120 from the recovered viruses, the challenge virus, and the vaccine virus. The predicted protein sequences of gp120 from the viruses recovered from macaques PEy, PWl, and 8124 are aligned with the gp120 sequences of the vaccine, V-II, and challenge, SHIVKU, viruses. The underlined letters above the alignment indicate whether that amino acid of the recovered virus from PEy or PWl is characteristic of the vaccine or challenge virus. The underlined letters below the alignment indicate whether that amino acid of the virus recovered from animal 8124 is characteristic of vaccine or challenge virus. “x” denotes the deletion of an amino acid.

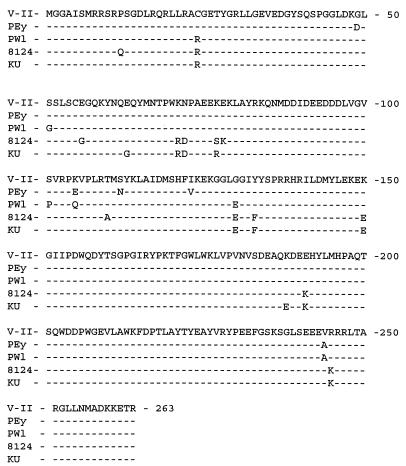

Analysis of the nef gene of the viruses showed five and six amino acid substitutions, respectively, in VPWl, and VPEy (Fig. 4). VPWl-Nef has a K105E substitution, while VPEy-Nef had a K105Q substitution. Amino acid 105 is within the SH3 domain that has been previously identified in Nef. The other changes seen in Nef were animal specific.

FIG. 4.

Alignment of the consensus amino acid sequences of Nef from SHIVKU, VII, and the viruses recovered from animals PEy, PWl, and 8124. The predicted protein sequences of Nef from SHIVKU and the viruses recovered from macaques PEy and PWl are aligned with the Nef sequence of the vaccine virus, V-II.

DNA sequence analysis revealed that the virus isolated from macaque 8124, SHIVKU-8124, has an intact vpu gene, along with a gp120 region that is closely related to SHIVKU (Fig. 3), demonstrating that this virus was derived from the challenge virus. This virus has three amino acid differences compared to the sequence from the challenge virus. Two of these changes are in V1, a region that is subject to frequent amino acid changes in challenge-derived viruses (P. Silverstein, unpublished observations). The third change, a T278M replacement, caused the loss of a potential glycosylation site. SHIVKU-8124-Nef has four amino acid changes compared to the corresponding sequence in SHIVKU (Fig. 4).

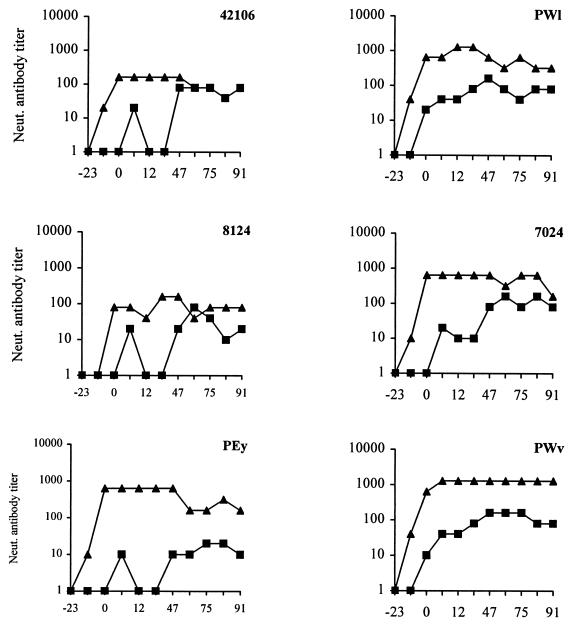

Sequentially collected plasma samples from vaccinated and control animals were tested for the presence of neutralizing antibodies against vaccine and challenge viruses. The results of these experiments are shown in Fig. 5. None of the nonimmunized animals challenged with SHIVKU developed detectable neutralizing antibodies to the virus (results not shown). However, three vaccinated animals developed high titers of neutralizing antibodies against vaccine virus that peaked after challenge (reciprocal neutralizing antibody titers of 160 to 1,280). The other three animals developed high titers of neutralizing antibodies that peaked the week of challenge (reciprocal neutralizing antibody titers of 160 to 640). These antibodies persisted throughout the 104-week postchallenge observation period. Prechallenge serum from two macaques, PWl and PWv, neutralized SHIVKU (antibody titers of 1/20 and 1/10, respectively). However, antibodies from four of six vaccinates did not neutralize pathogenic virus SHIVKU, indicating that at least some of the neutralization epitopes on vaccine virus were different from those on the challenge virus. After challenge with pathogenic virus, all six vaccinates developed SHIVKU-specific neutralizing antibodies that persisted throughout the observation period.

FIG. 5.

Titers of neutralizing antibodies to vaccine and challenge viruses in immunized animals. Sequential samples of sera were collected and tested for the presence of neutralizing antibody to VII (▴) and SHIVKU (■).

T-cell proliferative responses in immunized animals were also assessed at different time points starting at 47 weeks after challenge (Table 3). All vaccinated macaques showed persistent T-helper responses to both the vaccine and the challenge viruses. Macaque 8124, from which challenge-like virus was isolated at week 63, exhibited the best T-helper response. Animals from which vaccine-like viruses were isolated (PEy and PWl) had T-helper responses similar to those seen in animals from which virus could not be isolated.

TABLE 3.

Proliferative T-cell responses to vaccine and challenge viral antigens in macaques at various times following challenge

| Macaque | Antigena | Stimulation index at:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wk 47 | Wk 59 | Wk 72 | Wk 79 | Wk 91 | Wk 99 | ||

| 42106 | ΔvpuSHIVPPc | 11.3 | 7.1 | NDb | ND | 5.6 | 5.0 |

| SHIVKU | 4.7 | 5.1 | 9.4 | 22.7 | 4.3 | 4.5 | |

| 7024 | ΔvpuSHIVPPc | 9.6 | 5.4 | ND | ND | 4.1 | 3.8 |

| SHIVKU | 6.0 | 4.8 | 3.8 | 4.3 | 4.0 | 3.5 | |

| 8124 | ΔvpuSHIVPPc | 11.5 | 10.2 | ND | ND | 28.2 | 38.3 |

| SHIVKU | 6.3 | 8.3 | 15.8 | 25.0 | 19.5 | 30.2 | |

| PEy | ΔvpuSHIVPPc | 8.4 | 6.5 | ND | ND | 7.0 | 4.6 |

| SHIVKU | 11.4 | 5.6 | 6.1 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 4.5 | |

| PWl | ΔvpuSHIVPPc | 6.4 | 7.7 | ND | ND | 9.7 | 6.5 |

| SHIVKU | 11.0 | 5.7 | 7.1 | 18.0 | 6.8 | 4.6 | |

| PWv | ΔvpuSHIVPPc | 8.55 | 10.2 | ND | ND | 11.3 | 9.1 |

| SHIVKU | 11.0 | 6.8 | 5.6 | 12.4 | 6.5 | 4.4 | |

| PDb | ΔvpuSHIVPPc | 1.2 | 1.6 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| SHIVKU | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.9 | ND | ND | |

A total of 20 μl of UV-irradiated and heat-inactivated virus was added to each well and used as a source of antigen.

ND, not determined.

To determine whether inhibition of SHIVKU replication in animals correlated with the presence of cell-mediated immune responses, we examined PBMC from each animal for the presence of cytotoxic T lymphocytes against SHIVKU. Tests performed several times between weeks 55 and 103 have shown the same basic pattern illustrated in Table 4. These data showed that all of the animals had developed challenge virus-specific CTLs. This activity was directed against the Gag, Pol, and Env proteins.

TABLE 4.

Virus-specific CTL activities in macaques immunized with V-II and challenged with SHIVKU

| Macaque | % Specific lysis againsta:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHIVKU | HIVenv | SIVgag | SIVpol | |

| 42106 | 47.1 | 27.6 | 37.6 | 32.1 |

| 7024 | 37.7 | 27.3 | 50.1 | 36.6 |

| 8124 | 62.7 | 27.5 | 38.6 | 27.0 |

| PEy | 43.0 | 36.3 | 44.3 | 36.0 |

| PWl | 51.4 | 38.5 | 52.3 | 40.5 |

| PWV | 46.9 | 30.9 | 43.9 | 36.2 |

Macaques inoculated with V-II were tested for CTL activity at week 96 postchallenge. The specific lysis values shown here are at an effector/target ratio of 40:1. SHIVKU-specific lysis was determined by infecting concanavalin A-stimulated CD8+ depleted PBMC with SHIVKU and using these cells as targets in a 4-h chromium release assay. The Env, Gag, and Pol specific lysis values were determined by infecting herpesvirus papio-transformed B-LCL with recombinant vaccinia virus expressing one of these proteins and then using these cells as targets in a 4-h chromium release assay.

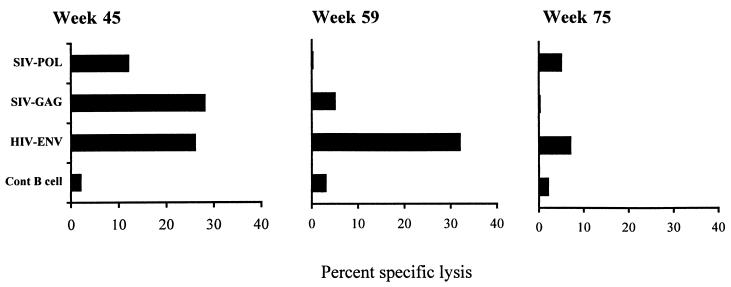

All of the control animals exhibited high virus burdens (viral RNA, >105 copies/ml), massive loss of CD4+ T cells, and a lack of detectable neutralizing antibodies against SHIVKU. Three of the four control animals died within 6 months of challenge, but a fourth animal survived for 83 weeks. The longest-surviving control animal, PDb, developed virus-specific CTLs against Gag, Pol, and Env (Fig. 6). By week 59 the CTLs against Gag and Pol disappeared, and by week 75 the CTLs to Env also became undetectable. This animal never developed a significant level of T-helper response to either vaccine or challenge viruses and ultimately succumbed to disease at week 82. The lack of T-helper response at these three time points may have been due to the fact that this animal had already experienced a precipitous decline in CD4+ T cells (10). This sequence of pathogenesis events is very similar to that in human beings succumbing to infection with HIV-1.

FIG. 6.

CTL activity in a nonimmunized macaque, PDb, that survived for 83 weeks after challenge with SHIVKU. PBMC collected from PDb at weeks 45, 59, or 75 postchallenge were stimulated in vitro with UV-irradiated autologous CD4+ T cells infected with SHIVKU. The growing PBMC were used as effectors in a 4-h chromium release assay and were tested against mock-infected T cells, B-LCLs infected with wild-type vaccinia virus, and recombinant vaccinia virus expressing HIVEnv, SIVGag, and SIVPol. The CTL activity shown here is the specific lysis obtained at an effector/target ratio of 40:1.

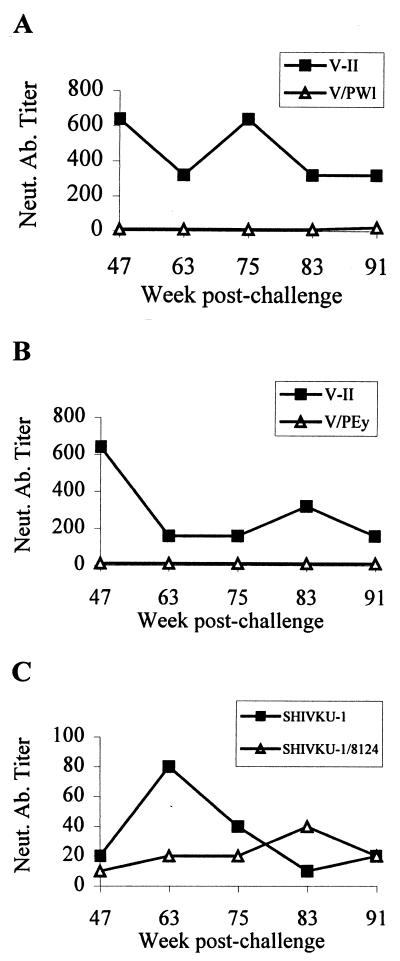

We determined whether the changes in the genomes of the vaccine-like viruses isolated from animals PWl and PEy and the SHIVKU-like virus isolated from animal 8124 had any effect on their susceptibility to neutralization. Virus neutralization tests using plasma collected at the late time points showed that, whereas the antibodies in the plasma of animals PWl and PEy neutralized the vaccine virus at high dilutions, the same antibodies were only minimally effective against the new viruses (Fig. 7A and B). In contrast, the SHIVKU variant isolated from animal 8124, which had undergone a much smaller number of changes, was neutralized at approximately the same dilutions of plasma that neutralized SHIVKU (Fig. 7C).

FIG. 7.

Comparative analysis of neutralizing antibodies (Neut. Ab.) against challenge and reemergent viruses in macaques immunized with VII and challenged with SHIVKU. Three of the six macaques yielded replication-competent virus at week 63. Two of the recovered viruses were derived from vaccine virus (animals PEy and PWl), while one animal yielded virus derived from SHIVKU (animal 8124). Sequentially collected plasma samples from these three macaques were tested for their ability to neutralize both the parental and the recovered viruses. Titers of neutralizing antibodies in serum samples collected from animals PWl (A), PEy (B), and 8124 (C) are shown.

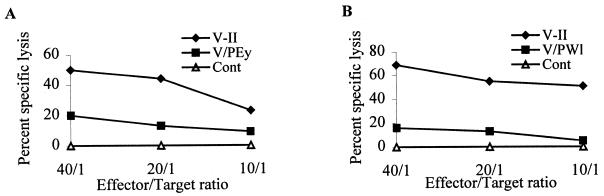

Similarly, we wished to determine whether genetic changes in the two vaccine virus variants affected the ability of CTLs to lyse cells infected with these new agents. The results demonstrated that cells infected with VPEy or VPWl were lysed at a significantly lower efficiency than cells infected with the original vaccine (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Comparative CTL activities of two animals against parental and recovered virus. PBMC collected at week 130 postchallenge were stimulated with UV-irradiated autologous CD4+ T cells infected with either vaccine or reemergent virus. Two weeks after cocultivation, growing PBMCs were used as effectors in a 4-h chromium release assay and then tested at effector/target ratios of 40:1, 20:1, and 10:1. The targets included mock-infected, vaccine-infected, and CD4+ T cells infected with reemergent virus.

DISCUSSION

The studies reported here extend findings in our first report that oral immunization of six macaques with the live virus vaccine V-II (ΔvpuSHIVPPc) resulted in protection from productive replication and disease caused by vaginally inoculated SHIVKU (10). All six animals became infected with the challenge virus, but all vaccinates have controlled replication of the virus. This protection has lasted more than 2 years. The animals have remained healthy and are free of infectious cells in the peripheral blood. They do not have detectable viral RNA in plasma and have not sustained any loss of CD4+ T cells. This control over SHIVKU is associated with persistent neutralizing antibodies and cell-mediated immune responses to this virus.

The present report focuses on the viruses that have persisted in these vaccinates. DNA of the vaccine virus (V-DNA) has persisted in all six animals throughout the observation period of 135 weeks, and infectious vaccine virus was isolated from lymph node of two of these animals at week 63. DNA of SHIVKU was also present in the lymph nodes of the six animals in the first few months following challenge but, during the subsequent period, this DNA became undetectable in four of the six animals, and challenge virus could not be isolated from lymph node cells. Of the remaining two animals in which SHIVKU DNA persisted, infectious SHIVKU has been isolated from the lymph node of only one. These results suggest that the vaccine had not only contributed to the suppression of replication of SHIVKU but also to the gradual reduction in total viral load. The validity of the claim for the reduction in challenge virus DNA burden is supported by the fact that a single set of primers was used to amplify both species of DNA. Because the primers bound to identical sites in both DNA species and the sequences of the amplified fragments were similar, the amplification of one species served as an internal control for the amplification of the other species. Thus, the detection of V-DNA and challenge virus DNA (C-DNA) in PBMC from week 55 and the detection of only V-DNA at later time points reflected a decline in the DNA concentration of the challenge virus relative to the DNA concentration of vaccine virus. This relative change could have been brought about by either a decline in the level of C-DNA or an increase in the level of V-DNA. If the change in the relative levels of C-DNA and V-DNA was due to a decline in the level of C-DNA, then a decline in total DNA load in these tissues would have been expected. However, if the change in the relative levels of C-DNA and V-DNA was due to an increase in V-DNA, then an increase in total viral DNA load would have been expected. In order to distinguish between these two possibilities, total viral DNA load in the animals was quantitated using a real-time PCR assay. Between weeks 63 and 135, the viral DNA load in three of the four animals, i.e., PEy, PWl, and PWv, declined dramatically. The fourth animal, 7024, died of causes unrelated to SHIV infection at week 117. However, the viral DNA load in this animal had also declined between weeks 63 and 103. Thus, the change in the ratio of C-DNA to V-DNA was due to a decrease in the concentration of the DNA of the challenge virus. These data introduce the possibility that a vaccine could contribute to the reduction of viral DNA load, as well as protection from disease.

In our previous report (10), only C-DNA was detected in three vaccinates at 18 weeks after challenge, but V-DNA was readily detected at later time points. This could have been due to the reactivation of latent reservoirs of vaccine virus by infection with the challenge virus. The reactivation then resulted in increased levels of V-DNA. Another possible explanation for this is that the lack of detection of V-DNA was due to a transient increase in the level of C-DNA associated with the initial burst of replication of challenge virus. Because the PCR assay used to detect V-DNA and C-DNA is similar to competitive PCR, an increase in the level of C-DNA would outcompete V-DNA in the PCR, allowing the detection of only C-DNA. As the replication of challenge virus was brought under control and the level of C-DNA started to decline, V-DNA once again became readily detectable.

Nucleotide sequence analysis of the env and nef genes of the persistent viruses obtained from the animals in this vaccine group has shown changes unique to each agent. Viruses recovered from PEy and PWl have an M-T change at amino acid 278 of gp120, resulting in the gain of a glycosylation site in these viruses. It is well established that glycosylation of gp120 plays an important role in immune recognition of the virus (20, 24). Aside from the gain of a glycosylation site at amino acid 278, gp120 of PWl had a deletion of five amino acids between amino acids 396 and 400 that eliminated a glycosylation site. These amino acid replacements and deletions might have been capable of causing major conformational changes in the gp120 molecule and may have contributed to the altered neutralization pattern of these agents.

Although there are reports of viral recombination in animals dually infected with two strains of SIVmac (3, 30), we found no evidence of recombination between vaccine and challenge viruses in the vaccinated animals. Viral gp120 sequences from the vaccine-like viruses recovered from PEy and PWl have clusters of amino acid replacements that could have arisen by recombination between vaccine and challenge sequences. However, multiple recombination events would have to be invoked to explain the interspersion of vaccine-like and challenge-like sequences. Such a high level of recombination within a region less than 2 kb in length is extremely unlikely.

In the vaccine-like viruses that were recovered from these animals, there are two amino acid changes in Nef that PEy and PWl have in common. One of these amino acid replacements is the K-Q/E change at amino acid 105 that is in an SH3 domain. These domains have been shown to regulate protein-protein interactions. Thus, this amino acid change may cause alterations in protein-protein interactions that are either quantitatively or qualitatively different than those seen with the parental vaccine virus.

This study provided a good opportunity to examine the role of neutralizing antibodies in protection against challenge virus. Four of the animals did not have neutralizing antibodies to SHIVKU at the time of challenge. These antibodies appeared after challenge. In the two animals that did have SHIVKU neutralizing antibodies, the titers were low. These increased after challenge. Therefore, neutralizing antibodies appeared to play a minimal role in controlling the initial burst of SHIVKU replication.

It is also of interest that all animals displayed significantly different neutralization titers to SHIVKU and VII, despite the fact that the gp120 sequences of these viruses are closely related. It is possible that one or more amino acid substitutions directly altered a major neutralization epitope(s) resulting in the change in neutralization titer. One of the differences between the gp120 sequences of SHIVKU and VII is the presence of a potential glycosylation site at amino acid 278. As discussed above, glycosylation has been shown to play an important role in the conformation of this protein and thus may be responsible for the difference in neutralization titer.

In contrast to neutralizing antibodies, CTLs may have played a major role in the control of replication of SHIVKU. Although we do not have prechallenge CTL data on these animals, other animals immunized in an identical manner with this vaccine developed CTLs against proteins of this challenge virus within 6 months of immunization. These CTLs have persisted for more than 1 year (A. Kumar et al., unpublished observations). In addition, the longest-surviving control animal in this study was the only macaque to produce cell-mediated immune responses against the challenge virus. Taken together, these two lines of evidence suggest that CTLs have played a major role in suppressing virus replication and perhaps in the progressive elimination of infected cells. Our data are in agreement with other data that suggest a role for CTLs in the control of HIV replication in humans (2, 18, 19) and SIV replication in macaques (12, 13, 31). Further, the recent demonstration that depletion of CD8+ T cells in SIV-infected macaques resulted in loss of CTLs and in higher viral burdens provided strong support for the importance of the role of CTLs in suppression of virus replication (7, 26).

In the present study, all six vaccinated macaques had virus-specific CTLs that were present almost 2 years after challenge with pathogenic virus SHIVKU. In all six animals, CTLs were directed against the envelope as well as the core proteins of the virus. CTL activity was mediated by classical CD8+ major histocompatibility complex-restricted CTLs. Although we did not find any distinctive bias regarding the induction of CTLs to individual proteins, Gag-specific CTL activity was higher than that induced to Env or Pol. We also did not find any difference in the immune responses between the animals from which virus was recovered from lymph node (i.e., animals PEy, PWl, and 8124) and those animals from which virus was not recovered (i.e., animals PWv, 7024, and 42106).

This study demonstrated that the immunized animals have maintained high levels of humoral and cell-mediated immune responses despite the lack of detectable replication in PBMC and a lack of detectable viral RNA in plasma. However, these immune responses correlated with the persistence of viral DNA derived from vaccine virus. This DNA could represent a reservoir of latent virus that is capable of sporadic reactivation. Reactivation from this viral reservoir could provide the persistent source of antigen that is thought to be necessary for the maintenance of high levels of immune responses. In view of the fact that virus-specific CTLs and CD4+ T-helper cells, as well as neutralizing antibodies, were present in the face of the progressive decline in levels of challenge virus, it is likely that both arms of the immune response are responsible for the progressive loss of this virus.

This study also demonstrated that, although both V-DNA and the immune responses to vaccine virus were persistent, there must have been a substantial decline in the level of V-DNA. In animals PEy and PWl, this decrease occurred despite the reduction in effectiveness of the immune response to the newly isolated variants compared to the response to the parental vaccine viruses. This raises the possibility that mechanisms other than the cellular and humoral immune responses may have been responsible for the maintenance of low viral loads of the vaccine virus. This alternate mechanism of virus control might include soluble factors that have been shown to be inhibitory to virus replication (1, 4, 21, 29). Alternatively, although the effectiveness of the immune responses to the new variants is reduced, they may be sufficiently potent to inhibit the replication of a virus that is already attenuated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Fenglan Jia for excellent technical assistance. We also thank Norman Letvin, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass., for providing herpesvirus papio stocks; D. Panicali and G. Mazzara, Therion Biologics, Cambridge, Mass., for recombinant vaccinia viruses; and the University of Kansas Medical Center Biotechnology Support Facility for assistance in DNA sequencing.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI-29382, RR-13152, RR-06753, and NS-32203 and NCI contract number NO1-CO-56000.

REFERENCES

- 1.Garzino-Demo A, Moss R B, Margolick J B, Cleghorn F, Sill A, Blattner W A, Cocchi F, Carlo D J, DeVico A L, Gallo R C. Spontaneous and antigen-induced production of HIV-inhibitory beta-chemokines are associated with AIDS-free status. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11986–11991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goulder P J, Rowland-Jones S, McMichael A, Walker B D. Anti-HIV cellular immunity: recent advances towards vaccine design. AIDS. 1999;13:S121–S136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gundlach B R, Lewis M G, Sopper S, Schnell T, Sodroski J, Stahl-Hennig C, Uberla K. Evidence for recombination of live, attenuated immunodeficiency virus vaccine with challenge virus to a more virulent strain. J Virol. 2000;74:3537–3542. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3537-3542.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heeney J L, Teeuwsen V J, van Gils M, Bogers W M, De Giuli M, Radaelli A, Barnett S, Morein B, Akerblom L, Wang Y, Lehner T, Davis D. Beta-chemokines and neutralizing antibody titers correlate with sterilizing immunity generated in HIV-1-vaccinated macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10803–10808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch V M, Dapolito G, Johnson P R, Elkins W R, London W T, Montali R J, Goldstein S, Brown C. Induction of AIDS by simian immunodeficiency virus from an African green monkey: species-specific variation in pathogenicity correlates with the extent of in vivo replication. J Virol. 1995;69:955–967. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.955-967.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Igarashi T, Endo Y, Englund G, Sadjadpour R, Matano T, Buckler C, Buckler-White A, Plishka R, Theodore T, Shibata R, Martin M. Emergence of a highly pathogenic simian/human immunodeficiency virus in a rhesus macaque treated with anti-CD8 mAb during a primary infection with a nonpathogenic virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14049–14054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin X, Bauer D E, Tuttleton S E, Lewin S, Gettie A, Blanchard J, Irwin C E, Safrit J T, Mittler J, Weinberger L, Kostrikis L G, Zhang L, Perelson A S, Ho D D. Dramatic rise in plasma viremia after CD8+ T cell depletion in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J Exp Med. 1999;189:991–998. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.6.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joag S V, Adany I, Li Z, Foresman L, Pinson D M, Wang C, Stephens E B, Raghavan R, Narayan O. Animal model of mucosally transmitted human immunodeficiency virus type 1 disease: intravaginal and oral deposition of simian/human immunodeficiency virus in macaques results in systemic infection, elimination of CD4+ T cells, and AIDS. J Virol. 1997;71:4016–4023. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.4016-4023.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joag S V, Li Z, Foresman L, Stephens E B, Zhao L J, Adany I, Pinson D M, McClure H M, Narayan O. Chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus that causes progressive loss of CD4+ T cells and AIDS in pig-tailed macaques. J Virol. 1996;70:3189–3197. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3189-3197.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joag S V, Liu Z Q, Stephens E B, Smith M S, Kumar A, Li Z, Wang C, Sheffer D, Jia F, Foresman L, Adany I, Lifson J, McClure H M, Narayan O. Oral immunization of macaques with attenuated vaccine virus induces protection against vaginally transmitted AIDS. J Virol. 1998;72:9069–9078. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9069-9078.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson R P, Desrosiers R C. Protective immunity induced by live attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:436–443. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson R P, Glickman R L, Yang J Q, Kaur A, Dion J T, Mulligan M J, Desrosiers R C. Induction of vigorous cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses by live attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1997;71:7711–7718. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7711-7718.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson R P, Lifson J D, Czajak S C, Cole K S, Manson K H, Glickman R, Yang J, Montefiori D C, Montelaro R, Wyand M S, Desrosiers R C. Highly attenuated vaccine strains of simian immunodeficiency virus protect against vaginal challenge: inverse relationship of degree of protection with level of attenuation. J Virol. 1999;73:4952–4961. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4952-4961.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar A, Lifson J, Silverstein P S, Jia F, Sheffer D, Li Z, Narayan O. Evaluation of immune responses induced by HIV-1 gp120 in rhesus macaques: effect of vaccination on challenge with homologous and heterologous strains of simian human immunodeficiency viruses. Virology. 2000;274:149–164. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar A, Stipp H, Sheffer D, Narayan O. Use of herpesvirus saimiri-immortalized macaque CD4 T cell clones as stimulators and targets of CTL responses in macaque/AIDs models. J Immunol Methods. 1999;230:47–58. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Letvin N L. Progress in the development of an HIV-1 vaccine. Science. 1998;280:1875–1880. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, Lord C I, Haseltine W, Letvin N L, Sodroski J. Infection of cynomolgus monkeys with a chimeric HIV-1/SIVmac virus that expresses the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:639–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McMichael A J, O'Callaghan C A. A new look at T cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1367–1371. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.9.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogg G S, Jin X, Bonhoeffer S, Dunbar P R, Nowak M A, Monard S, Segal J P, Cao Y, Rowland-Jones S L, Cerundolo V, Hurley A, Markowitz M, Ho D D, Nixon D F, McMichael A J. Quantitation of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and plasma load of viral RNA. Science. 1998;279:2103–2106. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5359.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Overbaugh J, Rudensey L M. Alterations in potential sites for glycosylation predominate during evolution of the simian immunodeficiency virus envelope gene in macaques. J Virol. 1992;66:5937–5948. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.10.5937-5948.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pal R, Garzino-Demo A, Markham P D, Burns J, Brown M, Gallo R C, DeVico A L. Inhibition of HIV-1 infection by the beta-chemokine MDC. Science. 1997;278:695–698. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reimann K A, Li J T, Veazey R, Halloran M, Park I W, Karlsson G B, Sodroski J, Letvin N L. A chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus expressing a primary patient human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate env causes an AIDS-like disease after in vivo passage in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1996;70:6922–6928. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6922-6928.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reimann K A, Li J T, Voss G, Lekutis C, Tenner-Racz K, Racz P, Lin W, Montefiori D C, Lee-Parritz D E, Lu Y, Collman R G, Sodroski J, Letvin N L. An env gene derived from a primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate confers high in vivo replicative capacity to a chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1996;70:3198–3206. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3198-3206.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reitter J N, Means R E, Desrosiers R C. A role for carbohydrates in immune evasion in AIDS. Nat Med. 1998;4:679–684. doi: 10.1038/nm0698-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rossio J L, Esser M T, Suryanarayana K, Schneider D K, Bess J W J, Vasquez G M, Wiltrout T A, Chertova E, Grimes M K, Sattentau Q, Arthur L O, Henderson L E, Lifson J D. Inactivation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity with preservation of conformational and functional integrity of virion surface proteins. J Virol. 1998;72:7992–8001. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7992-8001.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmitz J E, Kuroda M J, Santra S, Sasseville V G, Simon M A, Lifton M A, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Dalesandro M, Scallon B J, Ghrayeb J, Forman M A, Montefiori D C, Rieber E P, Letvin N L, Reimann K A. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+ lymphocytes. Science. 1999;283:857–860. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephens E B, Mukherjee S, Sahni M, Zhuge W, Raghavan R, Singh D K, Leung K, Atkinson B, Li Z, Joag S V, Liu Z Q, Narayan O. A cell-free stock of simian-human immunodeficiency virus that causes AIDS in pig-tailed macaques has a limited number of amino acid substitutions in both SIVmac and HIV-1 regions of the genome and has offered cytotropism. Virology. 1997;231:313–321. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stipp H, Kumar A, Narayan O. Characterization of immune escape viruses from a macaque immunized with live-virus vaccine and challenged with SHIVKu. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2000;16:1573–1580. doi: 10.1089/088922200750006092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Tao L, Mitchell E, Bogers W M, Doyle C, Bravery C A, Bergmeier L A, Kelly C G, Heeney J L, Lehner T. Generation of CD8 suppressor factor and beta chemokines, induced by xenogeneic immunization, in the prevention of simian immunodeficiency virus infection in macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5223–5228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wooley D P, Smith R A, Czajak S, Desrosiers R C. Direct demonstration of retroviral recombination in a rhesus monkey. J Virol. 1997;71:9650–9653. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9650-9653.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wyand M S, Manson K, Montefiori D C, Lifson J D, Johnson R P, Desrosiers R C. Protection by live, attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus against heterologous challenge. J Virol. 1999;73:8356–8363. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8356-8363.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]