Abstract

Seasonal changes in spring induce flowering by expressing the florigen, FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), in Arabidopsis. FT is expressed in unique phloem companion cells with unknown characteristics. The question of which genes are co-expressed with FT and whether they have roles in flowering remains elusive. Through tissue-specific translatome analysis, we discovered that under long-day conditions with the natural sunlight red/far-red ratio, the FT-producing cells express a gene encoding FPF1-LIKE PROTEIN 1 (FLP1). The master FT regulator, CONSTANS (CO), controls FLP1 expression, suggesting FLP1’s involvement in the photoperiod pathway. FLP1 promotes early flowering independently of FT, is active in the shoot apical meristem, and induces the expression of SEPALLATA 3 (SEP3), a key E-class homeotic gene. Unlike FT, FLP1 facilitates inflorescence stem elongation. Our cumulative evidence indicates that FLP1 may act as a mobile signal. Thus, FLP1 orchestrates floral initiation together with FT and promotes inflorescence stem elongation during reproductive transitions.

Keywords: photoperiodic flowering, florigen, stem growth, natural long days, FT, CO, FPF1 Arabidopsis, gibberellins, auxin

Introduction

The precise regulation of flowering timing is essential for plants’ success in reproduction and survival in natural environments. Seasonal environmental factors, including light and temperature, are integrated as signals to coordinate the timing of flowering predominately through the function of the florigen gene, FT.1,2 FT protein acts as a systemic flowering signal widely conserved in flowering plants.1,2 Under the standard laboratory long-day (LD) conditions, FT exhibits a single evening peak in Arabidopsis. Therefore, FT regulating mechanisms have been discussed based on the expression levels of FT in the evening. However, our recent study in outdoor LD conditions (where natural sunlight is the sole light source) revealed the presence of a bimodal expression pattern of FT with morning and evening peaks.3,4 The morning FT expression is often the major peak in plants grown outside because the evening peak is attenuated by the temperature differences throughout the day.3 The emergence of the FT morning peak is attributed to the abundant far-red light present in the sunlight, which is low in laboratory light sources. The red/far-red light (R/FR) ratio in natural light conditions is approximately 1.0, whereas it is typically greater than 2.0 in laboratory conditions with artificial light sources. This sunlight level R/FR ratio induces FT expression in the morning through the stabilization of CONSTANS (CO), the master regulator of FT, and phytochrome A-mediated FR high-irradiance response.3,4

Following local FT protein synthesis in the leaf phloem companion cells, FT is transported to the shoot apical meristem (SAM).5 FT physically interacts with FD, the SAM-specific bZIP transcription factor (TF), with the assistance of a 14–3-3 protein.6,7 This florigen activation complex (FAC) induces floral integrator genes, such as LEAFY (LFY) and APETALA1 (AP1), to initiate inflorescent development.8 In the ABCE floral organ development model, the combinatorial actions of floral homeotic genes specify identities of sepals, petals, stamens, and carpels. LFY and A-class gene AP1 start expressing during the early stage of inflorescence meristem formation and boost each other’s expression through positive feedback loop regulation.9,10 AP1 subsequently upregulates the major E-class gene SEPALLATA 3 (SEP3) through both direct binding on the SEP3 promoter and downregulation of repressive floral genes such as SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE (SVP).9,11 SEP3 is a crucial player in plant flowering because it not only triggers the expression of B- and C-class genes but is also involved in the formation of all four-type floral organs through the physical interaction with A-, B-, and C-class homeotic proteins.11,12 The induction of LFY and AP1 mediated by FT–FD interaction is currently considered the critical opening event in floral organ formation. However, while AP1 induces SEP3, SEP3 also directly triggers the expression of other homeotic genes, including AP1,13 indicating the positive feedback interaction between AP1 and SEP3. Consistently, like in the case of AP1, constitutive expression of SEP3 is sufficient to induce the early flowering phenotype.14

FLOWERING PROMOTING FACTOR 1 (FPF1), another factor implicated in Arabidopsis floral transition, is a small 12.6-kDa protein with no known functional domain, expressed primarily in inflorescence and floral meristems.15,16 Although the loss-of-function mutant phenotype has not yet been characterized, constitutive expression of FPF1 confers early flowering phenotypes.15,16 In contrast to the well-studied FT-dependent flowering pathway described above, the genetic pathway underlying the FPF1-dependent flowering induction remains elusive. The previous genetic study showed that FPF1 synergistically works with LFY and AP1, downstream components of FT, on flowering,16 suggesting that the mode of action of FPF1 is different from FT. However, it has not yet experimentally been shown whether FPF1’s flowering-promoting function is independent of FT in Arabidopsis. Moreover, FPF1 appears to integrate with gibberellin signaling. Severe reduction of endogenous gibberellin levels, either by the ga2–1 mutation or treatment of paclobutrazol (an inhibitor of gibberellin biosynthesis), reverted the early flowering phenotype induced by FPF1 overexpression,15 suggesting that FPF1 elicits flowering induction through the gibberellin signaling. In addition to the flowering acceleration, when FPF1 is ectopically over-expressed in seedlings, it promotes hypocotyl elongation through cell size expansion, indicating a distinct function from FT. Recent studies also revealed that rice (Oryza sativa) and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) homologs of FPF1 (known in rice as ACCELERATOR OF INTERNODE ELONGATION 1; ACE1) promote stem internode elongation but not flowering induction, suggesting that FPF1’s function in tissue elongation is widely conserved among plant species, but it does not always accompany with acceleration of flowering.17,18

Whereas the genetic pathway and interaction responsible for FPF1-dependent phenotypes are largely inconclusive, a recent study using Brachypodium distachyon revealed that FPF1 family proteins function as repressors of TFs through physical interaction.19 In contrast to Arabidopsis FPF1, two FPF1 homologs of Brachypodium, FPL1 and FPL7, delay flowering. These FPF1 homologs prevent FAC formation and attenuate the DNA binding activity of FD1, an FD homolog of Brachypodium, through protein-protein interactions.19 Thus, it is possible that flowering promotion by FPF1 may also be mediated by the direct interaction with specific TFs.

In Arabidopsis, FT gene expression is restricted to specific phloem companion cells located in the distal parts of a leaf.20,21 Despite decades of research, the question of how florigen-producing cells differ from the rest of the companion cells remains unresolved.20,22 These florigen-producing cells serve as the sites for integrating seasonal cues and transmitting signals to initiate and maintain floral transitions. Thus, understanding the unique characteristics of these cells is essential for unraveling regulatory strategies in plant development and for understanding signal integrations of seasonal information. Given the unique spatial distribution of FT-producing cells among phloem companion cells,20 we employed tissue/cell-specific translatome analysis, Translating Ribosome Affinity Purification (TRAP)-seq,23 to elucidate the unique characteristics of FT-producing cells. It revealed that FT-producing cells in the leaf vasculature may be developing phloem companion cells with active transport and that some known FT-regulating TFs are enriched in these cells. In addition, our translatome analysis demonstrated that, under LD conditions with natural R/FR, FPF1-LIKE PROTEIN 1 (FLP1), a homologous gene of FPF1, is highly expressed in the FT-producing cells. We found that FLP1 not only accelerates flowering in an FT-independent manner but also promotes inflorescence stem elongation. FLP1 induces early flowering when ectopically expressed in the SAM and may function as a systemic signaling protein. Thus, our study uncovered that phloem companion cells specialized for seasonal sensing supply multiple small (and possibly mobile) proteins to orchestrate growth and development during reproductive transitions.

Results

Tissue-specific translatome analysis of florigen-producing cells

To investigate the characteristics of FT-producing cells, we performed tissue/cell-specific translatome (TRAP-seq) analysis, as translatome more closely reflects protein abundance than transcriptome.24 In the TRAP-seq analysis, epitope-tagged RIBOSOMAL PROTEIN L18 (RPL18) controlled by tissue/cell-specific promoters are co-immunoprecipitated with translating mRNAs attached to the tagged RPL18-containing ribosomes. To analyze which transcript is translated in FT-producing cells, we generated the pFT:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 line. To express the FLAG-GFP-RPL18 gene in the same way as FT is expressed, the pFT:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 construct possesses not only the 5.7 kb upstream FT promoter region containing the entire upstream enhancer region “Block C” but also has the genomic sequences spanning from the FT gene to the 3’ Block E enhancer region inserted after the stop codon of FLAG-GFP-RPL18 (Figures 1A and S1A).22,25 To simulate FT expression in natural light environments, plants were grown under LD conditions with the R/FR ratio adjusted to natural sunlight (R/FR = approximately 1.0, referred to as LD+FR) alongside conventional lab LD conditions (R/FR > 2.0). The pFT:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 plants grown under LD+FR showed GFP signals in a part of cotyledon and true leaf vasculatures (Figures S1B and S1C), consistent with the spatial expression pattern of FT. Moreover, the levels of FLAG-GFP-RPL18 transcripts showed uptrends at both Zeitgeber Time 4 (ZT4) and ZT16 under LD+FR conditions compared with those in LD conditions (Figure S1D), indicating our construct captures FT regulation controlled by R/FR ratio changes. To elucidate the translatome profiles unique to the FT-producing companion cells, we included previously established TRAP-seq lines targeting phloem companion cells (pSUC2), mesophyll cells (pRBCS1A), epidermal cells (pCER5), and whole tissues (p35S) as comparison (Figure 1A).23 Although the activity of the 35S promoter is reportedly weaker in reproductive tissues such as bolted stems and inflorescences compared with other tissues, it is stably highly active in whole tissues of cotyledons, young true leaves, and roots at the vegetative stages,26,27 thus, we exploited the p35S:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 line as a whole tissue control for our analysis. Due to the depressed expression levels of the FLAG-GFP-RPL18 gene in the pCER5:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 line obtained from the ABRC stockcenter, we used the pCER5:FLAG-RPL18 line for the epidermal cell translatome. Previous TRAP RNA purification analyses utilized FLAG-RPL18 protein both with and without GFP,23,28 indicating that the presence or absence of GFP with RPL18 does not affect the isolation of translating mRNA. Samples were collected at ZT4, a timepoint four hours after the onset of light, corresponding to the timing of the morning peak of FT in LD+FR.4

Figure 1. The translatome profiling reveals the FT-producing cells are similar to the SUC2-expressing phloem companion cells but express unique transcripts.

(A) A schematic diagram of constructs equipped with tissue-specific promoters and FLAG-GFP-RPL18 used in this study. It is reported that with or without the inclusion of GFP coding sequences in the RPL18 construct does not affect the efficiency of TRAP.

(B and C) Unique translational patterns of tissue/cell-specific marker transcripts in our TRAP-seq datasets. The tissue/cell-specific TRAP lines are indicated on the left, and the growth conditions are at the top. Plants were grown under LD and LD+FR conditions. Color gradation reflects RPKM values depicted below for each gene. The results from 3 biological replicates are shown. The translated transcript levels of tissue-specific marker genes and typical qRT-PCR reference genes are shown in (B) and (C), respectively.

(D–I) Quantitative Venn diagrams showing overlaps between translatome datasets of pFT:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 and other tissue-specific lines. Up-regulated genes (D, F, and H) and down-regulated genes (E, G, and I) in comparison with p35S:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 under LD+FR conditions. The percentages of the translated genes in each unique portion of the diagrams are shown.

First, we assessed whether our tissue/cell-specific translatome datasets could enrich known marker gene transcripts. The normalized readcounts, Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads (RPKM), of tissue/cell-specific genes driving the tagged RPL18 gene (FT, SUC2, RBCS1A, and CER5) and other marker genes (AHA3 and APL for phloem; XCL1 and XCL2 for xylem; LHCB2.1 for mesophyll cells; ML1 for epidermis; GC1 and FAMA for stomata) were specifically increased in their corresponding lines, while typical reference genes in qRT-PCR analysis (UBQ10, PP2A, and IPP2) were ubiquitously found in all tissues (Figures 1B and C), confirming the unique tissue-specific enrichments of isolated mRNAs from each TRAP line. FT transcripts exhibited higher translation levels in LD+FR compared to LD (Figure 1B), reflecting the induction of the FT morning peak in LD+FR. Neither pFT:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 nor pSUC2:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 lines enriched xylem marker genes, XCP1 and XCP2, indicating that our TRAP-seq analysis provided high-resolution datasets that separated different cell types in vasculature tissues. Moreover, between pFT:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 and pSUC2:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 datasets, some phloem markers, AHA3 and APL, were further enriched in the FT-producing cells (Figure 1B), highlighting the unique characteristics of specific phloem tissues expressing FT. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the variations in translated mRNA levels among the examined tissues, we compared the RPKM values of transcripts detected in each line with those of the control p35S:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 line under LD and LD+FR conditions. This analysis revealed that there were larger numbers of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) existing in pFT, pSUC2, and pCER5-driven lines than in pRBCS1A-driven lines (Figures S2A–H; Data S1), indicating the uniqueness of phloem and epidermal tissues compared with photosynthetic ground tissues. Next, to holistically analyze unique translatome profiles in FT-producing cells, we asked how many DEGs overlapped between pFT and other tissue-specific lines. Overall, the DEGs in pFT:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 mostly overlapped with (but were not entirely contained within) the DEGs in the phloem companion cell-targeting pSUC2:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 and overlapped least with those in the mesophyll cell-enriched pRBCS1A:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 in both LD and LD+FR (Figures 1D–I and S2I–N). These findings indicate that FT-producing cells are closely related to SUC2-expressing phloem companion cells; however, they also have a unique identity.

To gain more insight into the unique characteristics of FT-producing cells, we next identified genes with tissue-specific enrichment patterns similar to FT using gene clustering analysis (Figure 2A and Data S2).29 For this analysis, we applied log2 fold-changes between four tissue/cell-specific RPL18 lines and control p35S:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 line grown under either LD or LD+FR conditions. These eight combinations (four different lines with two growth conditions) were used to separate genes exhibiting similar tissue/cell-specific enrichment patterns. We divided our translatome data into 12 groups in the cluster analysis (Figure 2A). FT, SUC2, RBCS1A, and CER5 genes were grouped into clusters 3 (388 genes), 12 (368 genes), 2 (1,007 genes), and 8 (1,424 genes), respectively. Terms enrichment analysis with Metascape30 showed that clusters 2 and 8 were enriched in genes related to photosynthesis and wax/cutin biosynthesis, respectively, consistent with the functions associated with RBCS1A and CER5 (Figures 2B and D). The SUC2 gene in cluster 12 co-expressed with many EXTENSIN (EXT) genes (EXT6, 8, 7, 9, 10, 13, 15, 16 and 17) encoding cell wall proteins (Figure 2F; Data S2). The emergence of EXT genes is evolutionally associated with plant vascularization.31,32 Thus, possible roles of EXTs in vascular development are under discussion, although their spatial expression patterns are still largely uncharacterized. Cluster 3, which contains FT, showed strong enrichment in terms related to phloem histogenesis, meristem growth regulation, and vascular/ion transport (Figure 2C), suggesting that FT-producing cells may be differentiating phloem companion cells with high transport activity. Among the transporters, FT transporter genes NaKR1, FTIP1, and QKY were highly translated in FT-producing companion cells (Figure 2G),33–35 suggesting that FT protein synthesis and transport are co-regulated. Cluster 11 also included genes highly translated in pFT:FLAG-GFP-RPL18. This cluster enriched genes related to DNA and mRNA metabolic processes, chromosome organization, gene silencing, etc. (Figure 2E), implying that gene transcription and translation are actively regulated in the FT-producing cells. These results imply that FT-producing cells may be differentiating phloem companion cells that are high in metabolic and transport activities within the phloem tissues.

Figure 2. The FT-producing cells are active in transport and nucleic acid metabolism.

(A) Heatmap clustering of the TRAP-seq data. The color indicates log2 fold-change compared to the p35S:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 data. The tissue/cell-specific TRAP lines and the growth conditions are indicated at the bottom of the heatmap. Clusters including FT (Cluster 3, 388 genes), RBCS1A (Cluster 2, 1007 genes), SUC2 (Cluster 12, 368 genes), and CER5 (Cluster 8, 1424 genes) are indicated.

(B–F) The top 10 enriched terms in clusters (2, 3, 8, 11, and 12) in the heatmap shown in (A). Enrichment analysis was conducted using Metascape. pFT, pSUC2, pRBCS1A, and pCER5 on top indicate the transgenic lines for TRAP-seq analysis; pFT:FLAG-RPL18, pSUC2:FLAG-GFP-RPL18, pRBCS1A:FLAG-GFP-RPL18, and pCER5:FLAG-RPL18, respectively. Red and blue colors on the boxes indicating each TRAP-dataset (pFT, pSUC2, pRBCS1A, and pCER5) denote that more than 50% of genes are significantly up- or down-regulated (enriched or depleted) in the target tissues compared to the p35S:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 dataset. The size and color of the bars indicate negative logarithm of the P-values. The cluster 12 genes were associated with only 3 statistically enriched terms.

(G) Unique translational patterns of FT protein-transporting genes in our TRAP-seq datasets. The tissue/cell-specific TRAP lines are indicated on the left, and the growth conditions are at the top. Plants were grown under LD and LD+FR conditions. Color gradation reflects RPKM values depicted below for each gene. The results from 3 biological replicates are shown.

In addition to identifying the molecular function linked to the FT-producing cells, our TRAP-seq datasets could be utilized to classify already known FT regulators from the point of tissue/cell-specific expression patterns. Although numerous FT-regulating transcription factors (TFs) have been identified through genetic studies,3 whether any of these TF transcripts are enriched in FT-producing cells is not known. To address this question, we compared the translational levels of known FT-regulating TFs across different tissues/cells using our TRAP-seq dataset to assess their potential tissue/cell-specific involvement in FT expression under LD+FR conditions (Figures S3 and S4). Although many of the known positive FT regulators showed similar translated mRNA levels across all tested tissues, CO and some CO-interacting regulators (NF-YB2, NF-YC3, APL, AS1, VOZ1, and CIB4) were particularly enriched in FT-producing cells (Figure S3). On the other hand, the levels of negative FT regulators varied across all tissue/cell types examined (Figure S4). Some negative FT regulators (FLC, MAF2, CDF5, COL9, HHO4, etc.) were particularly enriched in FT-producing cells, while specific TF families (DELLA, AP2-like, and bHLH) were enriched in other cell types such as epidermal cells (Figure S4). These results suggest that certain negative FT regulators may control FT levels in FT-producing cells, while other negative regulators may be involved in preventing FT expression in different cell types (such as mesophyll and epidermal cells) to restrict the spatial FT expression patterns.

The FT-producing cells express FLP1

With tissue-specific translatome datasets, we also aimed to identify a novel regulator of morning FT induction and developmentally relevant genes co-expressed with FT, which might have been overlooked by common usage of the artificial light (R/FR >2.0) growth conditions. To explore this possibility, we analyzed translational changes in specific tissues/cells, particularly FT-producing cells, upon adjustment of the R/FR ratio (Data S3). As expected, adjusting the R/FR ratio significantly increased the translational levels of FT transcripts in all TRAP lines except the pCER5:FLAG-RPL18 line (Figures 3A and S5). However, only a small number of genes were significantly upregulated by the R/FR adjustment across all examined tissues and cell types. In pFT:FLAG-GFP-RPL18, unlike FR-marker genes such as PIL1 and HFR1, none of the known FT-regulating TFs were strongly enriched by the light treatment (Figure 3A and Data S3).

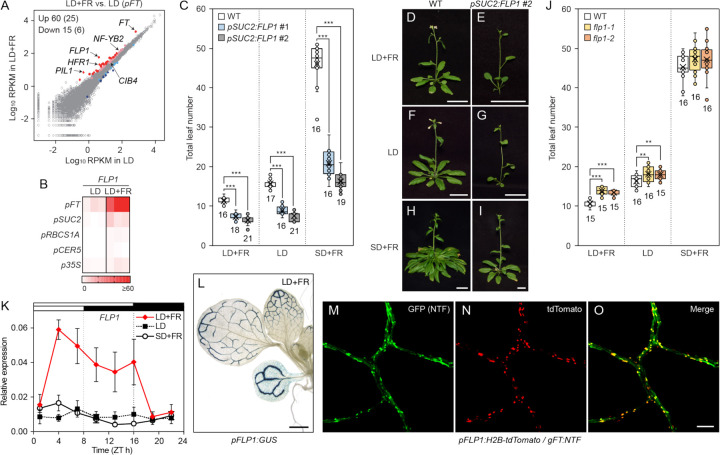

Figure 3. FLP1 is a photoperiodic flowering activator expressed in the FT-producing cells.

(A) Comparison between translatome datasets of the pFT:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 plants grown under LD and LD+FR conditions. X and Y axes are log10-transformed RPKM values in LD and LD+FR, respectively. Red/pink and blue/light blue color dots indicate significantly up-regulated and down-regulated genes in LD+FR (FDR < 0.05). Red and blue colors exhibit more than 2-fold difference, while pink and light blue are less than 2-fold difference. The number of the genes with FDR < 0.05 and, within the parenthesis, that of genes with FDR < 0.05 and more than 2-fold difference, are shown in the left corner. The positions of FT, FLP1, FR-marker genes (PIL1 and HFR), and FT regulators (CIB4 and NY-FB2) are indicated.

(B) Tissue/cell-specific translational levels of FLP1 mRNA in TRAP-seq. Letters on the left indicate the tissue/cell-specific TRAP lines used. The growth conditions are displayed on the top. The colors of squares indicate RPKM values in each biological replicate (n = 3).

(C) Accelerated flowering of the pSUC2:FLP1 overexpressors. The bottom and top lines of the box indicate the first and third quantiles, and the bottom and top lines of the whisker denote minimum and maximum values. Circles indicate inner and outlier points. The bar and the X mark inside the box are median and mean values, respectively. The numbers below the box indicate sample sizes. Asterisks denote significant differences from WT (***P<0.001, t-test).

(D–I) The representative images of flowered WT (D, F, and H) and pSUC2:FLP1 #2 (E, G, and I) plants grown under the LD+FR (D and E), LD (F and G), and SD+FR (H and I) conditions. Scale bar, 2 cm.

(J) The flowering phenotype of the flp1 mutants. The results were obtained and displayed the same way as the pSUC2:FLP1 plant results shown in (C). Asterisks denote significant differences from WT (**P<0.01; ***P<0.001, t-test).

(K) Time course of FLP1 gene expression in WT plants grown under LD+FR, LD, and SD+FR. The results represent the means ± SEM. (n = 3 biologically independent samples). White and black bars on top indicate time periods with light and dark.

(L) FLP1 promoter-driven GUS activity under the LD+FR conditions. There was no visible staining around the SAM and in the roots. Scale bar, 1 mm.

(M–O) Overlapped distribution patterns of FT- and FLP1-promoter activities in leaf minor veins in LD+FR. pFT:NTF (M), FLP1:H2B-tdTomato (N), and merge of GFP and RFP channel images (O). Note that GFP signals from NTF were observed in nuclei but also sometimes in both nuclei and the cytosol, while RFP signals from H2B-tdTomato exclusively existed in the nuclei. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Instead, we found that the translated mRNA level of a gene named FLP1 (At4g31380), a homolog of the meristem-expressing flowering activator FPF1,15,16 was upregulated predominantly in FT-producing cells under LD+FR conditions (Figures 3A, 3B and S5). FLP1 encodes a 14-kDa protein without any known functional domains. Due to its substantial homology with FPF1 (63% identity and 77% similarity over the entire 124 amino acids), we hypothesized that FLP1 may also play a role in regulating flowering. To investigate this hypothesis, given the phloem-specific expression of FLP1, we overexpressed FLP1 using the SUC2 promoter in wild-type (WT) plants possessing the pFT:GUS reporter (Figure S6).21 Remarkably, the pSUC2:FLP1 lines displayed strong early flowering phenotypes under all growth conditions, including short-day conditions with sunlight R/FR (SD+FR), which usually do not induce FT expression (Figures 3C–I). We generated flp1 mutants to assess the loss-of-function effect of FLP1 (Figure S7). Consistent with the high expression of FLP1 under LD+FR conditions (Figure 3B), the flp1 mutants exhibited a late flowering phenotype in LD+FR (Figure 3J). These results indicate that FLP1 functions as a flowering activator.

Having established the genetic role of FLP1 in flowering regulation, we then conducted a detailed analysis of FLP1 expression patterns. By analyzing the diurnal time course of FLP1 expression levels under LD+FR, LD, and SD+FR conditions, we found that FLP1 was specifically induced under LD+FR conditions during the daytime (Figure 3K). This indicates that both the LD photoperiod and the appropriate R/FR ratio mimicking natural sunlight are required to induce the FLP1 gene, similar to the morning induction of FT.

The Arabidopsis genome contains another uncharacterized FLP1 homolog, FLP2 (At5g10625). Unlike FLP1, our TRAP-seq datasets and qRT-PCR analysis demonstrated that neither FLP2 nor FPF1 showed induction by the R/FR light adjustment, although FLP2 also exhibited the highest expression in FT-producing cells among tested tissue/cell types (Figure S8).

We next examined FLP1 spatial expression patterns using the FLP1 promoter-driven GUS (ß-Glucuronidase) gene to assess whether FLP1 induction is tissue-specific (Figure 3L). The spatial expression pattern of FLP1 in LD+FR resembled that of FT.21 To more precisely investigate the extent to which the spatial expression patterns of FLP1 overlap with FT, we generated the pFLP1:H2B-tdTomato/pFT:NTF transgenic line (NTF: Nuclear Targeting Fusion protein, which contains GFP36). This dual reporter line demonstrated that FLP1 spatial expression signals highly overlapped with FT-expressing companion cells in leaf minor veins (Figures 3M–O and S9). Thus, we conclude that FLP1 is spatiotemporally induced in a manner similar to morning FT under natural LD conditions to regulate flowering.

FLP1 promotes flowering in parallel with FT

Because FLP1 is expressed in FT-producing cells and promotes flowering, we investigated the genetic relationship between FLP1 and FT. To assess whether the early flowering phenotypes in pSUC2:FLP1 lines were caused by an increase in FT expression, we measured FT expression levels in 2-week-old plants. FT expression was significantly higher in the pSUC2:FLP1 lines under both LD+FR and LD conditions (Figure 4A). The pFT:GUS assay demonstrated that FLP1 overexpression enhanced FT promoter activity specifically in cotyledons (Figures 4B–D). However, under SD+FR conditions, FT expression levels remained low in the pSUC2:FLP1 lines, although flowering timing of SD+FR-grown pSUC2:FLP1 is comparable with LD-grown WT plants (Figures 3C, 4A, and 4E–G). This low FT level persisted even in 3-week-old plants in SD+FR (Figures 4A and 4H–J). In addition, despite their late flowering phenotype of the flp1 mutants in LD+FR, the flp1 mutants did not exhibit decreased FT expression under LD+FR conditions (Figure 4A). Hence, FT expression change alone cannot fully explain the flowering acceleration caused by FLP1. To explore other potential factors contributing to FLP1-induced flowering acceleration, we examined the expression of TWIN SISTER OF FT (TSF), the closest homolog of FT with a similar function in floral induction (Figure S10).37 However, we observed no significant difference in TSF expression among the plant lines examined, suggesting that neither changes in FT nor TSF expression can fully account for the flowering acceleration mediated by FLP1.

Figure 4. FLP1 induces flowering independently of FT in a CO-dependent manner.

(A) FT expression in WT, pSUC2:FLP1, and flp1 mutants. FT gene expression levels were analyzed in the plants grown under LD+FR, LD, and SD+FR for 2 or 3 weeks and harvested at ZT4 and ZT16. The results represent the means ± SEM. Each dot indicates a biological replicate (n = 4). Asterisks denote significant differences from WT (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001, t-test).

(B–J) The effect of FLP1 overexpression on the FT promoter activity. GUS staining assay was conducted using pFT:GUS lines with WT background (B, E, and H), pSUC2:FLP1 #1 (C, F, and I), and pSUC2:FLP1 #2 (D, G, and J) grown under LD+FR conditions for 2 weeks (B–D), SD+FR for 2 (E–G) and 3 weeks (H–J). Arrowheads indicate increased FT promoter activity repeatedly observed in cotyledons of the pSUC2:FLP1 lines grown in LD+FR. Scale bars, 1 mm.

(K) Time course of FLP1 expression in WT, ft-1, ft-101, and ft-1 tsf-1 double mutant plants grown in LD+FR. White and black bars on top indicate time with light and dark. The results represent the means ± SEM (n = 3 biologically independent samples).

(L) The positions of CO-responsive element (CORE), CCACA motif, and G-box cis-element sequences on the 1.8 kb-upstream of FLP1, which was used as the FLP1 promoter sequences in our experiments.

(M) Time course of FLP1 expression in WT and co-101 mutant plants grown in LD+FR. The results represent the means ± SEM (n = 3 biologically independent samples).

(N) A Model of the CO-dependent regulation of FLP1 and FT. CO regulates the expression of both FLP1 and FT in photoperiod- and far-red light-dependent manners. FT and FLP1 promote floral transition in parallel. FLP1 may increase FT expression under LD potentially through the unknown positive feedback pathway.

(O) The effect of FLP1 overexpression on flowering of ft-101 and co-101 mutants. The bottom and top lines of the box indicate the first and third quantiles, and the bottom and top lines of the whisker denote minimum and maximum values. Circles indicate inner and outlier points. The bar and the X mark inside the box indicate median and mean values, respectively. The numbers below the box indicate the sample sizes. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P<0.05, Tukey’s test).

(P) The effect of the flp1 mutation on flowering time of the ft-101 and co-101 mutants. Different letters indicate a statistically significant difference (P<0.05, Tukey’s test).

Next, we explored the possibility that FLP1 accelerates flowering as a downstream component of FT by quantifying FLP1 expression in ft and ft tsf double mutants. FLP1 expression levels in these mutants were comparable with those in WT plants (Figure 4K), indicating that FT (and TSF) are not upstream of FLP1. Given the similar spatial and temporal expression patterns of FLP1 and FT under natural light conditions, we began to suspect that core modulators of FT expression might drive their similar patterns of expression. CO, a key transcriptional activator of FT, binds to CO-responsive elements [COREs; TGTG(N2–3)ATG] and CCACA motifs located proximal to the transcriptional start site of FT.22 Finding CORE and CCACA motifs in the FLP1 promoter (Figure 4L) prompted us to analyze FLP1 expression in the co mutant. The induction of FLP1 was nearly abolished in this mutant under LD+FR conditions (Figure 4M), suggesting that CO may directly regulate FLP1. These results indicate that FLP1 is a component within the photoperiod pathway and CO likely regulates the transcription of FT and FLP1, which promote flowering in parallel, in the same companion cells under natural light conditions (Figure 4N).

Since FLP1 appears downstream of CO in parallel with FT, we transformed pSUC2:FLP1 into ft-101 and co-101 mutant lines to ask whether FLP1 alone was sufficient to induce flowering independently of FT. Multiple pSUC2:FLP1/ft-101 and pSUC2:FLP1/co-101 lines flowered early compared to the ft-101 and co-101 parental lines in LD+FR, LD, and SD+FR (Figures 4O and S11), indicating that functional CO and FT are not essential for FLP1-dependent flowering induction once FLP1 is expressed. We further analyzed the flowering time of flp1–1 ft-101 and flp1–1 co-101 double mutants (Figure 4P). The flp1–1 ft-101 mutant flowered later than the ft-101 mutant under LD+FR and LD conditions, indicating that FT and FLP1 act additively to promote flowering. The flp1–1 co-101 lines also showed later flowering than the co-101 line in LD+FR, although the difference was smaller (Figure 4P). Since CO function was necessary for FLP1 induction, the small but significant delay in flowering in flp1–1 co-101 double mutant lines was unexpected, suggesting that even the marginal levels of FLP1 mRNA present in the co-101 mutant might contribute to the induction of flowering or that FLP1 may also regulate flowering other than the photoperiodic pathway.15 These findings indicate that FLP1 may promote flowering through an FT-independent mechanism.

FLP1 promotes inflorescence stem growth

We speculated on the reasons behind plants equipping FLP1 as an independent flowering inducer parallel to FT. One possibility is that FLP1 acts as a booster of flowering to ensure developmental transition occurs at the optimal timing under natural light conditions. However, beyond its role in flowering, we also observed that FLP1 overexpressors and flp1 mutants exhibited significantly elongated and shortened hypocotyl and leaf length, respectively (Figures 5A–C), similar to previous studies on FPF1 overexpression phenotypes.15 These results suggest that FLP1 possesses developmental functions distinct from FT.

Figure 5. FLP1 promotes stem elongation.

(A) Representative images of hypocotyls of 10-day-old WT, pSUC2:FLP1 plants, and flp1 mutants under LD+FR conditions. Scale bar, 1 mm.

(B) Hypocotyl length of 10-day-old WT, pSUC2:FLP1, and flp1 plants grown under LD+FR conditions. The results represent the means ± SEM of independent biological replicates. Each dot indicates a biological replicate (n = 15).

(C) Length of 1st and 2nd true leaves (from the tip of the leaf blade to end of the petiole) of 14-day-old WT, pSUC2:FLP1, and flp1 mutants grown under LD+FR conditions. Each dot indicates a biological replicate (n ≥ 40). Black bars indicate means. Asterisks denote significant differences from WT (***P<0.001, t-test).

(D) The effects of overexpression of FLP1 and mutations of FLP1 and FLP2 on inflorescence stem elongation. Stem length was measured 4, 7, and 8 days after the visible flower bud formation at the SAM. The results represent the means of independent biological replicates ± SEM. Each dot indicates a biological replicate (n = 16–29). Asterisks denote significant differences from WT (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001, t-test).

(E and F) The effect of overexpression of FLP1 on stem elongation of Nicotiana benthamiana. The arrowheads indicate the position of the leaf branching. The same colors of the arrowheads in (E) and (F) exhibit the same developmental sets of leaf branches in these plants. Plants shown in the figures are LD-grown 4-week-old plants. Scale bar, 2 cm.

Recent studies revealed that FPF1 homologs in rice (ACE1) and tomato promote stem elongation.17,18 These reports led us to hypothesize that FLP1 may also affect inflorescence stem growth. We analyzed the length of inflorescence stems over time following the floral transition. In this experiment, we individually set the day 0 of the stem measurement for each plant as the day when the first flower bud structure of the plant was visible at the SAM (before the recognizable stem elongation). Thus, flowering timing differences among individuals do not affect the results of timings of inflorescence stem elongation. Our stem measurement analysis revealed that FLP1 overexpression significantly promoted inflorescence stem elongation (Figure 5D). The negative effect of the flp1 mutations on stem elongation was moderate, suggesting the involvement of other redundant factors. Considering that FLP2 was also expressed in FT-producing cells, albeit at lower levels, and that FLP1 and FLP2 share 65% amino acid identity and 78% amino acid similarity, we hypothesized that FLP1 and FLP2 may have overlapped functions. To investigate this, we generated the flp1 flp2 double mutants by genome editing (Figure S12). The flp1 flp2 mutants showed more severe stem elongation defects than the flp1 single mutants (Figure 5D), suggesting functional redundancy existed between FLP1 and FLP2. Furthermore, we demonstrated that Arabidopsis FLP1 overexpression induced substantial stem elongation in N. benthaminana (Figures 5E, F, and S13). As FPF1/FLP1 homologs exist in a wide variety of angiosperms (monocots and eudicots),17 their functional roles in stem elongation are likely conserved among diverse plant species. In addition, overexpression of N. tabacum FPF1 in a few Nicotiana varieties induced early flowering with an elongated bolted stem.38 Taken together, our findings demonstrate that FLP1 regulates both flowering and stem elongation processes in Arabidopsis.

FLP1 induces a floral homeotic gene expression

To identify genes associated with the flowering and growth phenotypes of FLP1 overexpressors and flp1 mutants, we performed RNA-seq analysis by comparing 2-week-old WT with pSUC2:FLP1 #2 under LD+FR and SD+FR conditions as well as flp1–1 under LD+FR conditions sampled at ZT4 (Data S4–6). pSUC2:FLP1 #2 showed upregulation of auxin- and gibberellin-responsive genes under LD+FR and SD+FR conditions, respectively (Figure S14), implying possible contributions of these hormones in flowering and growth phenotypes of pSUC2:FLP1 lines. Previous studies also showed that overexpression of FPF1 homologs in rice, ROOT ARCHITECTURE ASSOCIATED 1 and FPF1-LIKE 4, enhanced auxin levels and signaling.39,40 Moreover, gibberellin is crucial for FPF1-dependent flowering and stem internode phenotypes.15–17 Therefore, we quantified the levels of auxin and gibberellin, together with other phytohormones also implicated in growth and cellular differentiation in Arabidopsis using WT, pSUC2:FLP1 #2 and flp1–1 lines (Figure S15). Plants significantly changed levels of many hormones between LD+FR and SD+FR conditions (Figure S15). However, FLP1 gene expression levels did not affect indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) contents at least at the whole plant levels. Gibberellin A4 (GA4) was decreased in the flp1–1 line, but no change in pSUC2:FLP1 #2, suggesting that GA4 accumulation is not the primary cause of flowering acceleration and stem elongation. We also observed that there were no obvious changes in the levels of other phytohormones by the alternation of FLP1 expression levels, suggesting that the developmental changes observed in FLP1 overexpressors and flp1 mutants are not primarily attributable to the alterations in phytohormone levels.

By analyzing the overlap of upregulated genes in pSUC2:FLP1 under LD+FR and SD+FR conditions and downregulated genes in flp1–1 under LD+FR conditions, we identified 14 genes as putatively acting downstream of FLP1 under these conditions (Figure 6A). Most of these genes encode nutrient transporters (that could be important for growth and development); however, we also found two TF genes, SEP3 and PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR 8 (PIF8), among the 14 genes. PIF8 promotes hypocotyl elongation under FR light conditions,41 and could plausibly contribute to the hypocotyl phenotypes of FLP1 overexpressors and flp1 mutants. SEP3 is a key floral homeotic E-class gene whose overexpression causes early flowering.14

Figure 6. FLP1 induces the floral homeotic gene SEP3 in a FT-independent manner.

(A) A Venn diagram consisting of up-regulated genes in 2-week-old pSUC2:FLP1 #2 plants grown under LD+FR and SD+FR, and down-regulated genes in flp1–1 mutant grown under LD+FR compared to the WT grown under the same conditions. The table on the right lists 14 genes that were overlapped by three conditions. Genes encoding transcription factors and nutrient transporters were highlighted in pink and blue, respectively.

(B–G) The effect of FLP1 levels on the gene expression at 1-week-old plants. Plants were grown under LD+FR conditions for 1 week and harvested at ZT4 and ZT16. The relative expression levels of FLP1 (B), FT (D), TSF (E), and floral homeotic genes, SEP3 (C), LFY (F), and AP1 (G) were analyzed. The results represent the means ± SEM. Each dot indicates a biological replicate (n = 4). Asterisks denote significant differences from WT (*P<0.05; ***P<0.001, t-test).

(H–K) The effect of FLP1 overexpression on the gene expression in the ft-101 and co-101 mutant backgrounds. The expression of FLP1 (H) and floral homeotic genes, SEP3 (I), LFY (J), and AP1 (K) were analyzed. Plants were grown under LD+FR conditions for 2 weeks and harvested at ZT4. The results represent the means ± SEM. Each dot indicates a biological replicate (n = 4). Asterisks denote significant differences from the parental line (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001, t-test).

Consistent with our RNA-seq analysis, qRT-PCR analysis demonstrated that both SEP3 and PIF8 were upregulated in pSUC2:FLP1 and downregulated in flp1 mutants under LD+FR conditions (Figures S16A and C). However, FT was also upregulated in 2-week-old pSUC2:FLP1 lines under LD+FR conditions (Figure 4A), which could potentially contribute to the observed increase in SEP3 levels. To eliminate the possible influence of FT on SEP3 induction, since FT expression increases with plant maturation,42 we examined gene expression in younger seedlings and tested whether SEP3 induction started before or after FT induction by FLP1. In 1-week-old plants, SEP3 was significantly upregulated in pSUC2:FLP1 lines at both ZT4 and ZT16 according to FLP1 expression levels, while neither FT nor TSF showed consistent upregulation by FLP1 (Figures 6B–E), indicating that FLP1 induced SEP3 before FT induction.

Similarly, under SD+FR conditions, although the amplitude was lower in pSUC2:FLP1 #1, both pSUC2:FLP1 lines showed significant SEP3 upregulation at ZT4 in 2-week-old and ZT16 in 3-week-old plants (Figure S16B). Since FT expression is extremely low under SD+FR conditions, these results support the notion that FT is not essential for FLP1-dependent SEP3 induction. To genetically confirm this finding, we analyzed SEP3 expression in pSUC2:FLP1/ft-101 #2 and pSUC2:FLP1/co-101 #2 lines. Compared with the parental lines, these transgenic lines showed significant upregulation of SEP3 in both RNA-seq and qRT-PCR analyses (Figures 6H and I, Data S7). Using RNA-seq and qRT-PCR, we further addressed whether repressors of SEP3, such as SVP,11 might be suppressed by FLP1; however, we did not observe a clear correlation between the expression of SEP3 and its repressors including SVP (Figure S17).

In the current model of the FT-dependent flowering pathway, FT forms a complex with the bZIP transcription factor FD that induces the expression of LFY and AP1, followed by the derepression and direct activation of SEP3.8,9,11 Because FLP1 does not rely on FT for its SEP3 induction, we asked next whether FLP1 activates SEP3 through the pathway mediating LFY and AP1. We therefore examined the expression of these FT downstream genes in our lines. At 1 week old, the pSUC2:FLP1 lines did not consistently upregulate LFY and AP1 (Figures 6F and G), in marked contrast to SEP3 upregulation. Furthermore, in pSUC2:FLP1 plants grown under SD+FR conditions for 2–3 weeks, the induction of LFY and AP1 was weaker than that of SEP3 (Figures S16F and H). In the 2-week-old ft-101 and co-101 backgrounds, significant upregulation of AP1 expression by pSUC2:FLP1 was not observed, while SEP3 was clearly upregulated (Figures 6H–K). Taken together, our results suggest that FLP1 induces flowering through SEP3 induction in an LFY- or AP1-independent manner, which differs from the FT-dependent mechanism that requires LFY and AP1 induction prior to SEP3.

FLP1 acts at the shoot apical meristem potentially through the interaction with TFs

To test whether FLP1 is active at the SAM in promoting flowering, we expressed FLP1 using the SAM-specific UNUSUAL FLORAL ORGANS (UFO) promoter.43 Our pUFO:FLP1 lines showed significant early flowering under LD and SD+FR conditions (Figure 7A), although it did not flower as early as pSUC2:FLP1 lines likely due to the less FLP1 protein amount expressed in these lines. This result indicates that FLP1 can promote flowering at the SAM. Because FLP1 is a small protein lacking known functional domains, we questioned if FLP1 has TF interacting partners to modulate plant gene expression, similar to the FT–FD interaction. Employing a yeast two-hybrid Arabidopsis TF library comprising 1,736 TFs, we identified potential interactors with FLP1 (Data S8). To further narrow down functionally relevant interactors, we included FPF1 as a bait protein, considering the functional similarity between FLP1 and FPF1. We found that 162 TFs interacted with both FLP1 and FPF1 in yeast (Data S8). Interestingly, neither FLP1 nor FPF1 interacted with FD in our yeast two-hybrid assay, suggesting that the mode of action of FLP1 on flowering could be different from that of FT in Arabidopsis. Of these candidates, we selected 22 TFs based on their known functions in floral transitions and inflorescence stem elongation and validated their physical interaction with FLP1 using an in vitro protein-protein binding assay (Data S8 and Figures S18A–C).44,45 In this assay, 16 TFs exhibited more than 2-fold signals compared to the negative control (Figure S18A). Notably, these positive TF interactors included those expressed at the SAM and involved in regulating cell fate determination during the floral transition, such as WUSCHEL (WUS), DORNRÖSCHEN (DRN), DORNRÖSCHEN-LIKE (DNL), and PUCHI.8,46

Figure 7. FLP1 may be a vascular-mobile protein that may function in the tissues distantly from leaves.

(A) The flowering phenotype of the pUFO:FLP1 lines grown under LD+FR, LD, and SD+FR. Asterisks denote significant differences from WT (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001, t-test).

(B–D) BiFC assay for physical interaction between FLP1-sfGFP11 and WUS-sfGFP1–10 in tobacco epidermal cells shown in the reconstitution of GFP signals (B). Histone H2B-tdTomato (C) marks the positions of nuclei. The image (D) is the merged image of GFP and RFP channels. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(E) A schematic diagram of the P2A system that enables to independently express two proteins, FLP1-mCerulean and 3xNLS-YFP proteins, using the single promoter-driven construct.

(F–H) Confocal images of cleared true leaf of pSUC2:FLP1-mCerulean-P2A-3xNLS-YFP excited with 405 nm. The locations of 3xNLS-YFP (F) and FLP1-mCerulean-P2A (G) in a true leaf are shown. The image (H) shows the autofluorescence of the same sample. Arrowheads in (G) indicate mCerulean signals in the vasculatures where YFP signals in (F) are low. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(I) Grafting junction (indicated by arrowheads) of p35S:GFP-FLP1 scion and WT rootstock. The images of the GFP and DIC channels were merged. Scale bar, 500 μm.

(J) Movement of the GFP-FLP1 protein to the WT rootstock from the p35S:GFP-FLP1 scion. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(K) The Y-shape grafted plant at 6 days after grafting (DAG). The circle indicates the location of the SAM of the stock used for gene expression analysis in (L). A black arrowhead and a white open arrowhead depict the positions of the graft junction and the bottom of the hypocotyl of the stock plant, respectively. Scale bar, 1 mm.

(L) The effect of FLP1 derived from the scion on SEP3 gene expression in the SAM of the flp1–1 stock at 14 DAG. The results represent the means of independent biological replicates ± SEM. Each dot indicates a biological replicate derived from independent grafted plants (n = 11–12). The percentage signifies a relative difference compared to the control flp1–1 scion. An asterisk denotes a significant difference (*P<0.05, t-test).

(M) Representative images of the SAM containing tissues of the flp1–1 stock grafted with either pSUC2:FLP1 #2 scion or the flp1–1 scion on 18 DAG. The image was used to measure the height of the inflorescence stem. Scale bar, 1 mm.

(N) The length of the inflorescence stem of the flp1–1 stock at 18 DAG. The results represent the means of independent biological replicates ± SEM. Each dot indicates a biological replicate (n = 15–19). Asterisks denote significant differences (**P<0.01, t-test).

(O) A model of coordination of flowering and inflorescence stem growth by FLP1 and FT. CO regulates the expression of both FLP1 and FT in photoperiod- and far-red light-dependent manners. FT is synthesized in specific leaf phloem companion cells in response to environmental stimuli and moved to the SAM to induce flowering by directly upregulating LFY and AP1. FLP1 is also synthesized in the same cells where FT is synthesized. It can move through the phloem, and possibly the movement of FLP1 may be important for promoting floral transition through SEP3 induction. FLP1 also participates in the inflorescence stem elongation.

A recent study revealed that WUS represses SEP3 expression by direct binding to its promoter,47 implying a possible link between FLP1 and WUS proteins with SEP3 transcription. It prompted us to conduct a BiFC assay to further confirm the interactions between FLP1 and WUS (Figures 7B–D and S18D–P). In the tobacco transient expression system, consistent with the results described above, FLP1 strongly interacted with WUS in the nucleus forming speckle-like structures (Figure S18P). Although further investigation is required to understand the molecular functions of FLP1, our results raised the possibility that FLP1 promotes flowering through the interaction with developmentally important TFs such as WUS, which directly alters SEP3 gene expression. Given the TF-deactivating function of Brachypodium FPF1 homologs,19 FLP1 may attenuate WUS’s transcriptional activities through physical interaction.

FLP1 may behave like a mobile flowering-promoting signal

FLP1 is a 14-kDa small protein synthesized in the same florigen-producing phloem companion cells active in long-distance transport, including the transportation of FT protein (Figures 2C and G). Previous proteome studies have detected FLP1 protein in various plant tissues distantly from leaves, including floral organs and roots.48–50 Similarly, the rice FLP1 homolog, ACE1, is broadly induced within the internodes of elongated stems upon submergence, but it is implicated to function at the intercalary meristem.17 Taken together with its flowering-promoting activity at the SAM (Figure 7A), it is plausible that FLP1 may act as a mobile signal for flowering. To explore this possibility, we investigated FLP1’s movement in leaves using the pSUC2:FLP1-mCelurean-P2A-3xNLS-YFP line (Figures 7E–H and S19). Since the P2A sequence causes protein cleavage during translation, two different proteins, FLP1-mCerulean and 3xNLS-YFP, are produced simultaneously by the same promoter activity (Figure 7E). In the tobacco transient assay, FLP1-mCelurean did not exhibit a specific cellular localization, whereas 3xNLS-YFP strongly accumulated in the nucleus, confirming the P2A protein cleavage system is working in planta (Figure S19A). In the pSUC2:FLP1-mCelurean-P2A-3xNLS-YFP line, we could track the movement of FLP1-mCerulean in leaf vascular tissues by comparing the localization patterns of CFP with nuclear-localized three tandemerized YFP likely to stay in the cells where synthesized. This Arabidopsis transgenic line showed early flowering (Figure S19B), indicating FLP1-mCerulean retained the flowering-promoting function. Even in the locations with relatively low SUC2 promoter activity, the FLP1-mCerulean signal appeared more uniform within the phloem (Figures 7F and G), suggesting that FLP1-mCerulean is translocated from the originally expressing companion cells. To further confirm FLP1’s movement, we conducted grafting of p35S:GFP-FLP1 shoot scions and WT rootstocks (Figures 7I and S20). The GFP-FLP1 protein exhibited no specific cellular localization as FLP1-mCerulean (Figures S20A and B). The GFP-FLP1 protein synthesized in the scion was observed along the phloem of the Arabidopsis WT rootstock near the tip (Figure 7J), indicating that GFP-FLP1 was translocated to the root through the vasculature.

Given its potential as a mobile signaling protein, we further studied whether the effect of FLP1 on flowering is transferable to the SAM using Y-shape micrografting (Figure 7K). Here, the hypocotyls of flp1–1 or pSUC2:FLP1 #2 scions were inserted into the hypocotyl of flp1–1 stocks. Once the grafting was successful, on 11 days after grafting (DAG), all the leaves in the stock plants were carefully removed to ensure that only the scion plant controlled phloem streaming. In other words, the removal of the leaves relegated the flp1–1 stock plant to acting primarily as a sink tissue. We assessed the movement of FLP1 from the scions to the SAM of the flp1–1 stock based on the SEP3 gene induction and flowering promotion of the stock. At 14 DAG, the pSUC2:FLP1 #2 scion significantly increased SEP3 expression in the SAM of the flp1–1 stock compared to the flp1–1 stock grafted with the flp1–1 scion (Figure 7L). Consistent with the higher expression levels of SEP3 at the SAM, the pSUC2:FLP1 scion increased the inflorescence length of the flp1–1 stock compared to the flp1–1 stock with the flp1–1 scion at 18 DAG (Figures 7M and N), indicating the progression of the flowering stage and potentially inflorescence stem elongation induced by FLP1 supplied from the scion. Although our Y-grafting experiments do not eliminate the movement of possible FLP1-induced molecules, the cumulative evidence supports the possibility that FLP1 might be a mobile protein regulating flowering time and stem elongation.

Discussion

FT gene expression is confined to the specific phloem companion cells. Therefore, analyzing specific gene expression profiles in these specialized cells is crucial to understand how plants integrate environmental information and find the timing of the transition to the reproductive growth stage. We employed TRAP-seq translatome analysis that enabled us to isolate mRNAs specifically translated in FT-producing cells as well as in other tissue types (Figure 1). An advantage of translatome analysis is a higher correlation with proteome than transcriptome in eukaryote cells.24 Our TRAP-seq analysis revealed that uniquely translated mRNA populations in FT-producing cells resembled those in SUC2-expressing phloem companion cells, compared with those in photosynthetic RBCS1A-expressing tissues or in CER5-expressing epidermal tissues (Figures 1D–I and S2), indicating we succeeded isolating specialized companion cells expressing FT. Highly enriched translating mRNA in FT-expressing cells suggest that these cells might be differentiating or newly differentiated phloem companion cells, which are active in metabolism and transportation (Figures 2A–F). These cells uniquely express genes important for FT transport, together with FT (Figure 2G), suggesting that FT protein synthesis and transport are coordinated. Our datasets also provided insights into tissue-specific expression of known FT transcriptional regulators (Figures S3 and S4). Notably, we observed more tissue-specific translational differences of negative FT regulators than of positive regulators. As often regulation of the expression of negative factors is the primary regulatory strategy of plants, FT tissue-specific expression may also be controlled by the presence or absence of specific negative regulators in different tissues.

Our TRAP-seq analysis also facilitated the identification of a novel flowering regulator. Using plants grown under modified LD growth conditions that mimic natural light quality, we have identified a previously uncharacterized FLP1 as a possible systemic protein involved in the regulation of both flowering and stem elongation (Figure 7O). FLP1 and FT induce flowering in parallel, but they are under the regulation of CO, suggesting that CO regulates multiple flowering signals simultaneously. Both under the CO regulation, FLP1 and FT form the coherent type 1 feed-forward loop (C1-FFL) with OR gate in natural long days to induce flowering (Figure 4N). The C1-FFL is the most common feed-forward loops that exist in biological systems, and the OR logic C1-FFL ensures continuous output generation (i.e., continuous flowering induction) even having an abrupt loss of input signals (i.e., variable nature of flowering inducing environmental conditions).51,52 Having the FT/FLP1 C1-FFL may facilitate plants to induce and maintain flowering status under ever-changing natural environments in spring.

Because FLP1 is induced in LD+FR but not in LD, it is plausible that factors other than CO are required for FLP1 gene expression. The promoter of the FLP1 gene possesses a G-box element, a consensus DNA-binding site of PIF transcription factors (Figure 4L). Our recent study revealed that PIF7 contributes to the morning FT gene expression in a phyA-dependent manner under the same LD+FR conditions.4 It is interesting to ask whether plants use the same pathway to induce FLP1 gene expression under natural light conditions.

In addition to its flowering role, FLP1 also possesses a distinct function from FT, which is the promotion of inflorescence stem elongation. The coordination between flowering and inflorescence stem elongation in plants remains poorly understood despite being a common phenomenon.53 A system using photoperiod- and R/FR ratio-dependent CO function to regulate the expression of both FLP1 and FT, each with both similar and unique functions, appeals as a convincing mechanism for the orchestration of the complex developmental changes that accompany the floral transition (Figure 7O). FLP1 and FT are synthesized in the same restricted leaf phloem companion cells, possibly similar to FT, FLP1 may be translocated to the SAM to accelerate the floral transition. Our gene expression analyses indicate that the primary target of FLP1 is SEP3, which probably contributes to flowering induction through positive feedback regulation among homeotic genes.9,13 In addition to the flowering promotion, unlike FT, FLP1 accelerated inflorescence stem elongation through an unknown mechanism. Given the presence of FLP1 homologs across various plant species17 and the consistent role of a few characterized FLP1 homologs as regulators of flowering, growth, or both,15–18,38–40,54,55 these factors may also function as systemic regulators to coordinate the growth and development in meristematic tissues in response to changing environments.

Although FPF1 family proteins, including FLP1, lack any known functional domains, a recent study unveiled that FPF1 homologs of Brachypodium physically repress the DNA binding of the FD1,19 raised a possibility that other FPF1 family proteins also deactivate TFs. In our Y2H analysis, neither FLP1 nor FPF1 interacted with FD (Data S8). Moreover, Brachypodium FPF1 homologs genetically depend on functional FT to control flowering,19 while our study demonstrated that FLP1 flowering function is independent from FT (Figure 4O). Although further confirmation is still required, these results suggest that Arabidopsis FD may not be involved in FLP1- or FPF1-dependent flowering regulation, unlike the case of Brachypodium. We found that FLP1 strongly interacts with WUS. Since WUS is a direct negative regulator of SEP3, FLP1 might interfere with the transcriptional activity of WUS by attenuating its DNA binding activity. The WUS gene is essential for stem cell maintenance. Thus, its mutation causes pleiotropic defects, including the severe disruption of flower formation, preventing us from investigating the genetic interaction between FLP1 and WUS using flowering time measurements. In the future, the FLP1’s role in SEP3 induction and its possible interaction with WUS should be investigated more in-depth.

Limitation of the study

Although our experimental evidence supports the hypothesis that FLP1 may act as a mobile signal of flowering, we have not yet directly confirmed its movement to the SAM. We have attempted to generate a variety of different FLP1 fusion constructs; however, based on the flowering and stem elongation phenotypes of the overexpressors, some fusion proteins appeared to lose their functionality. FLP1 apparently easily loses its activity by the protein fusion possibly due to the small molecular size (14 kDa). In addition, observation of the movement of small proteins (attached to larger tagged proteins) to the SAM in Arabidopsis often seems challenging due to the narrow path to the SAM as shown in the case of FT.56 Even after the FT protein had been recognized as a florigen for a while, its movement to the SAM in Arabidopsis had not been experimentally proven until recently.57 As the mobility of FT to the SAM was demonstrated through interaction with FD using the BiFC system incorporating superfold fluorescence proteins,57 the utilization of interacting TFs might help detect the movement of FLP1 to the SAM in the future. In this study, we demonstrated that FLP1 is active in the SAM to induce flowering (Figure 7A), suggesting that FLP1 proteins produced in the leaf phloem companion cells can be active if they move to the SAM. The conventional Arabidopsis micrografting experiment showed that GFP-FLP1 can be transferred through the phloem to the root tip (Figures 7I and J). The Y-shape micrografting experiments demonstrated that the flowering-promoting activity of FLP1 can be transmitted to the grafted flp1–1 stock plants (Figures 7K–N). At this point, our data still cannot rule out the possibility that FLP1 promotes the production of other mobile signals of flowering, such as other signal proteins, phytohormones, and metabolites. However, if FLP1 mediates flowering induction via other molecules, it is unlikely to be FT since FLP1 induces flowering in an FT-independent manner (Figures 4O and S11). TSF is also unlikely, given the minor effect of FLP1 on TSF gene expression (Figure S10). Gibberellin or auxin appears not primary cause either, as FLP1 overexpression did not affect levels of these phytohormones (Figure S15). We have not measured levels of flowering-promoting metabolites such as trehalose-6-phosphate;58 however, our RNA-seq experiments suggest that the effect of FLP1 on genes related to sugar metabolism including TREHALOSE-6-PHOSPHATE SYNTHASE 1 is minor (Figure S14). Although none of these known mobile signals of flowering might not account for the flowering-promoting activity of FLP1, we still need further investigation to examine whether FLP1 itself may act as a mobile signal of flowering and stem elongation. At least, our analysis indicates that FT-producing cells co-express FLP1, which could induce SEP3 expression to contribute to floral transition and subsequent fluorescence stem elongation under natural long-day conditions.

STAR Methods

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Takato Imaizumi (takato@uw.edu).

Materials availability

All data required to support the claims of this paper are included in the main and supplemental information.

All reagents generated in this study are available on request from the lead contact.

Data and code availability

The TRAP-seq and RNA-seq data have been deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) Sequence Read Archive under accession number, DRA016554 and DRA016641, respectively.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and study participant details

Plants were grown either on 1x Linsmaier and Skoog (LS) media plates without sucrose containing 0.8% (w/v) agar or Sunshine Mix 4 soils (Sun Gro Horticulture) as described in Song et al.3 with minor adjustments. Surface sterilized seeds were sown on media plates or soils at a low density to avoid shading effects from neighboring plants. Seeds sown on plates or soils were kept in 4 °C for at least for 2 days for stratification prior to transferring to the incubators.

Plants on plates were grown in plant incubators (Percival Scientific and Nippon Medical & Chemical Instruments) at constant 22 °C under white fluorescent or LED light with a fluence rate of 90–110 μmol m−2 sec−1. In long-day (LD; 16-hour light and 8-hour dark) conditions without far-red light (FR) LED, the red/far-red (R/FR) ratio was >2.0. In LD+FR and short-day (SD+FR; 8-hour light and 16-hour dark) conditions in which the R/FR ratios were adjusted to approximately 1.0 using dimmable FR LED light (Fluence Bioengineering and Co. Fuji Electric) connecting to the timer switch. To diffuse and dim FR light from the light source, the FR LED light fixture was covered with one-layer white printer paper. The R/FR ratio was frequently checked using spectrophotometers and R/FR sensors (Spectrum Technologies, Apogee Instruments, and Nippon Medical & Chemical Instruments) to make sure that the proper R/FR rates were maintained.

For soil growth, soils were supplemented with a slow-release fertilizer (Osmocote 14–1414, Scotts Miracle-Gro) and a pesticide (Bonide, Systemic Granules) and filled in standard flats with inserts (STF-1020-OPEN and STI-0804, T.O. Plastics). For flowering time measurements, plants on soil flats were grown in PGC Flex reach-in models with broad-spectrum white light and FR LED lighting (Conviron) at constant 22 °C. For LD and LD+FR conditions, the fluorescence rate was set to 100 μmol m−2 sec−1; for SD+FR conditions, 200 μmol m−2 sec−1. The number of rosette and cauline leaves of soil-grown plants was counted when the length of the bolting stem became about 1 cm. For inflorescence stem length measurements, plants were grown in the same Percival Scientific plant incubators used for sterile growth in plates. For inflorescence stem elongation analysis, the plants were grown under LD+FR conditions. The total length of the bolting stems was recorded 4, 7, and 8 days after the formation of the visible flower bud.

Method details

Molecular cloning and plant materials

All Arabidopsis thaliana transgenic plants and mutants are Col-0 background. To generate pSUC2:FLP1 and pUFO:FLP1 transgenic lines, the full length of FLP1 cDNA was amplified by the primers (5’- CACCATGTCTGGTGTGTGGGTATTCAACA −3’ and 5’-TACTACATGTCACGGACATGGAAG-3’) and cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). Once sequences of FLP1 cDNA were verified, FLP1 cDNA was transferred to the binary GATEWAY vectors, pH7SUC2 and pH7UFO, both of which the 35S promoter in pH7WG259 was replaced by 0.9 kb of SUC2 and 2.6 kb of UFO promoters, respectively. The pSUC2:FLP1 construct was transformed into wild-type (WT) plants possessing pFT:GUS reporter gene,21 ft-101, and co-101 plants. The pUFO:FLP1 construct was transformed into WT. To generate p35S:GFP-FLP1 lines, the FLP1 cDNA in pENTR/D-TOPO was transformed into the vector pK7WGF2,59 which has an N-terminal GFP gene. The p35S:GFP-FLP1 construct was transformed into WT. All transgenic overexpressor lines have single insertions of the constructs and are homozygote when utilized.

The flp1–1 and flp1–2 mutant lines were generated by CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing of WT plants using pKI1.1R plasmid.60 To make pKI1.1R containing single gRNA targeting the FLP1 coding region, the annealed primers (5’-ATTGTAACCAGCAGCAGAGGATG-3’ and 5’-AAACCATCCTCTGCTGCTGGTTA-3’) were inserted into pKI1.1R as previously described.60 To generate the flp1 flp2 double mutants, FLP2 was mutated in the flp1–2 mutant background using the pKIR1.1 construct containing single gRNA targeting the FLP2 coding region made by the primer set (5’-ATTGTAAGATGAGACGGCTTCAC-3’ and 5’-AAACGTGAAGCCGTCTCATCTTA-3’). All gene-editing T-DNAs were genetically removed from the genome-edited mutant lines by the T3 stage.

To synthesize the pFT:NTF construct, we used pENTR/D-TOPO harboring 5.7 kb upstream of FT, nuclear-targeting fusion protein (NTF),36 and FT genomic and downstream regions. The construct was subsequently transformed into the GATEWAY destination vector pGWB50161. Due to the technical difficulty in cloning 5.7 kb promoter region within single PCR, several shorter fragments were cloned first and ligated together to generate the 5,722 bp of the FT promoter. First, 3,553 to 5,722 bp upstream region containing SpeI, SacI, and XhoI sites at 3’ end was amplified by PCR using primers (5’-CACCATTTGCTGAACAAAAATCTATTAC-3’ and 5’-CTCGAGGAGCTCACTAGTATATAAGAGATATGTGTCAATCC-3’, restriction enzyme recognition sequences in the primers are underlined hereafter) and cloned into pENTR/D-TOPO. Subsequently, 1,719 to 3,923 bp upstream of FT was amplified using primers (5’-ACTTGGATATGATGTTAAGTATC-3’ and 5’- TATTTTCTACTAATTTTAGTTACACAC-3’), and 1,754 to 3,834 bp upstream region was inserted using SpeI and SacI sites. Next, 1 to 1,870 bp upstream region was amplified using primers (ATTAATCTTGTCTGCGACTGCGACC-3’ and 5’-AGCTCGAGCTTTGATCTTGAACAAACAGGTGGTTTC-3’), and 1 to 1,754 bp upstream region was inserted using SacI and XhoI sites. To fuse FT promoter and NTF, NTF sequences containing XhoI sites at 5’ and 3’ ends were amplified by PCR using primers (5’-ATCTCGAGATGGATCATTCAGCGAAAAC-3’ and 5’-GACTCGAGTCAAGATCCACCAGTATCCTC −3’) and inserted into pENTR/D-TOPO carrying 5.7 kb upstream of FT promoter using XhoI sites. Finally, FT genomic fragment (Chr1: 24,331,510–24,335,529) containing FT gene body (exons, introns and 3’-UTR) as well as following 1,822 bp of the 3’ sequences, including FT regulatory element Block E,72 were amplified using primers (5’-GGCGCGCCATGTCTATAAATATAAGAGA-3’ and 5’- GGCGCGCCTATTAAACTAGCAGTCAAA-3’) and inserted into the AscI site existed in the pENTR/D-TOPO already containing FT promoter and NTF genes. The resulting pENTR/D-TOPO construct containing both 5’ and 3’ sequences of FT and the NTF gene was introduced into pGWB501 binary vector (referred to as pFT:NTF). The pFT:NTF construct was transformed into WT plants containing pACT2:BirA36 for future use for INTACT (isolation of nuclei tagged in specific cell types) approach.

To generate pFT:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 for TRAP-seq, we amplified the FLAG-GFP-RPL18 fragment using primers containing a SalI site (5’-ACGCGTCGACGGTACCTATTTTTACAACAA-3’) and an AscI site (5’-GGCGCGCCCCGGCCGCCGTGCT-3’) and cloned into XhoI and AscI sites (note SalI- and XhoI-cut overhands are the same) in the same pENTR/D-TOPO used for generating pFT:NTF, which already contains the 5.7 kb upstream of FT promoter. Then the same 3’ FT genomic regions (spanning from FT gene body to the Block E sequences) was inserted into the AscI site to generate the entire pFT:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 construct. The pFT:FLAG-GFP-RPL18 construct harboring from the FT promoter to genomic FT sequences was transferred to the pGWB401 binary vector and transformed into WT.

The pFLP1:H2B-tdTomato construct was made by swapping the heat-shock promoter (HS) of pPZP21162 HS:H2B-tdTomato with 1,853 bp of the FLP1 promoter. The FLP1 promoter was amplified by the primers (5’- CCTGCAGGAGAATCTGATGATGTTGAGGCTAGTCG-3’ and 5’- GTCGACGACTCCGTTTTTGTTGAATACCCACAC-3’) and inserted using SbfI and SalI restriction enzyme sites. This construct was transformed into the already established pFT:NTF plants.

To synthesize the pSUC2:mCerulean-P2A-3xNLS-YFP construct, we first cloned multiple cloning sites of pRTL273 into pENTR/D-TOPO (denoted pENTR-MCS). Next, 3xNLS-YFP derived from pGreenIIM RPS5A-mDII-ntdTomato/RPS5A-DII-n3Venus74 was cloned into BamHI and XbaI sites of the pENTR-MCS. Using NPSN12-mCerulean75 as a template, mCerulean-P2A was amplified by PCR using primers (5’-GAGCTCCTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCC-3’ and 5’-GGATCCCCCATAGGTCCAGGATTTTCTTCAACATCTCCAGCTTGCTTAAGAAGAGAA AAATTAGTAGCGCCGCTGCCCATATGCTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCCGAG-3’), and inserted into SacI and BamHI sites of the pENTR-MCS clone already containing 3xNLS-YFP cDNA. To generate an in-frame fusion of FLP1 and mCerulean genes, the full length of FLP1 cDNA, whose stop codon was replaced with SacI site, was amplified using the primers (5’CACCATGTCTGGTGTGTGGGTATTCAACA-3’ and 5’-GAGCTCCATGTCACGGACATGGAAGA-3’) and cloned into the different pENTR/D-TOPO plasmid. This FLP1 cDNA without the stop codon was excised by NotI and SacI and inserted into NotI and SacI sites of the pENTR-MCS containing mCerulean-P2A-3xNLS-YFP cDNA. Finally, the pENTR-MCS containing fused FLP1-mCerulean-P2A-3xNLS gene was transformed into the pH7SUC2 vector. The pSUC2:FLP1-mCerulean-P2A-3xNLS-YFP construct was transformed into WT plants.

To generate the FLP1:GUS construct, 1,858 bp of FLP1 promoter was amplified by the primers (5’-AAAGCTTGAAGCAGAATCTGATGATGTTGAGGCTAGTCGTTATCAC-3’ and 5’- CGGATCCGTTGTAAGGATTCTCCACCAGCCTCATGACTCCG-3’) and inserted into HindIII and BamHI sites of pBI101.65 The resulting FLP1:GUS construct was transformed into WT plants.

Translating Ribosome Affinity Purification sequencing (TRAP-seq)

All transgenic lines for TRAP-seq, p35S:FLAG-GFP-RPL18, pRBCS1A:FLAG-GFP-RPL18, pCER5:FLAG-RPL18, pSUC2:FLAG-RPL1823 and pFT:HF-GFP-RPL18 (Figure 1A) were grown in 1xLS plates as described above. Ten-day-old plants grown under LD conditions were transferred to LD+FR or kept growing in the same LD chamber for additional 4 days. Whole tissues including roots of 14-day-old plants were quickly harvested and frozen in liquid nitrogen. TRAP RNA was isolated as previously described.23 Pulverized tissues were homogenized in approximately five-time volume (w/v) of polysome extraction buffer [0.2 M Tris-HCl pH 9.0, 0.2 M KCl, 0.025 M EGTA, 0.035 M MgCl2, 1% (w/v) Brij-35, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 1% (v/v) Igepal CA 630, and 1% (v/v) Tween 20, 1% (v/v) Polyoxyethylene (10) tridecyl ether, 1mM DTT, 1mM PMSF, 50 μg/mL cycloheximide, and 50 μg/mL chloramphenicol]. Homogenized samples were centrifuged in 16,000xg for 15 min at 4 °C, subsequently, the supernatant was filtrated with Miracloth. Protein G Dynabeads (Invitrogen) coupled with anti-FLAG M2 antibody (F1804, Sigma-Aldrich) was applied to the filtrated samples transferred to 50 mL falcon tube, followed by the incubation at 4 °C for 2 hours with gentle shaking using a rocking platform. Subsequently, beads were collected with magnets for 4 min at 4 °C. After the supernatant was removed using a pipet, 6 mL of freshly prepared wash buffer (0.2 M Tris-HCl pH 9.0, 0.2 M KCl, 0.025 M EGTA, 0.035 M MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 100 μg/mL cycloheximide, and 50 μg/mL chloramphenicol) were added to the beads, mixed by gentle inverting the tube, and incubated at 4 °C for 2 min with gentle shaking on rocking platform. Beads were collected with magnets at 4 °C for 4 min, supernatant was removed carefully. This washing step was repeated two more times with 6 mL and 1 mL of the washing buffer. After 1 mL of the washing buffer was removed, 450 μL of RLT Lysis buffer (Qiagen) with 4.5 μL β-mercaptoethanol was directly added to the beads and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. The rest of the process for TRAP RNA isolation was conducted following by the manufacture protocol of RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) except for skipping the use of shredder spin columns. RNA-seq libraries for 3’-Degital Gene expression were prepared using YourSeq Strand-Specific mRNA Library Prep Kit (Amaryllis Nucleics) following the manufacture protocol. Sequencing was performed on the Illumina Nextseq 550 platform. Approximately 20 to 66 million reads (average 38 million reads) were produced from each sample. Adapter and low-quality sequences were trimmed by Trimmomatic software (version 0.32) (LEADING:20, TRAILING: 20, MINLEN: 36).76 By HISAT2 software (version 2.2),66 the remaining reads were mapped to Arabidopsis genome sequences from The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR, version 10) (http://www.arabidopsis.org/). Mapped reads were lined to 32,398 Arabidopsis annotated genes by Cufflinks software (version 2.2.1).67 As the expression intensities, the number of mapped reads was normalized by Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads (RPKM). In transgenic plants, expressional differences between LD and LD+FR were inferred by Cuffdiff software (version 2.2.1) in 32,948 genes.67 Up- and down-regulated genes were defined as genes with significantly higher and lower RPKM reads (FDR < 0.05), respectively. The interactomes were constructed based on FLOR-ID77 using Cytoscape.68

qRT-PCR

For the time course gene expression analyses, total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen), and cDNA synthesis and quantitative PCR (qPCR) were performed as previously described.78 For other tests, total RNA was extracted from plants grown on plates using NucleoSpin RNA extraction kit (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co.). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using 2 μg RNA and PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara Bio). qRT-PCR was performed using the first-strand cDNAs diluted 5-fold in water and KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Master Mix (2x) kit (Roche) and gene-specific primers in a LightCycler 96 (Roche). ISOPENTENYL PYROPHOSPHATE / DIMETHYLALLYL PYROPHOSPHATE ISOMERASE (IPP2) and PROTEIN PHOSPHATASE 2A SUBUNIT A3 (PP2AA3) were used as the internal control for normalization. For statistical tests, log2-transformed relative expression values were used to meet the requirements for homogeneity of variance. qPCR primers used in this study are listed in Table S1.

GUS assay