Abstract

Background

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major cause of chronic disability. Worldwide, it is the leading cause of disability in the under 40s, resulting in severe disability in some 150 to 200 million people per annum. In addition to mood and behavioural problems, cognition—particularly memory, attention and executive function—are commonly impaired by TBI. Cognitive problems following TBI are one of the most important factors in determining people's subjective well‐being and their quality of life. Drugs are widely used in an attempt to improve cognitive functions. Whilst cholinergic agents in TBI have been reviewed, there has not yet been a systematic review or meta‐analysis of the effect on chronic cognitive problems of all centrally acting pharmacological agents.

Objectives

To assess the effects of centrally acting pharmacological agents for treatment of chronic cognitive impairment subsequent to traumatic brain injury in adults.

Search methods

We searched ALOIS—the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group’s Specialised Register—on 16 November 2013, 23 February 2013, 20 January 2014, and 30 December 2014 using the terms: traumatic OR TBI OR "brain injury" OR "brain injuries" OR TBIs OR "axonal injury" OR "axonal injuries". ALOIS contains records of clinical trials identified from monthly searches of a number of major healthcare databases, numerous trial registries and grey literature sources. Supplementary searches were also performed in MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, The Cochrane Library, CINAHL, LILACs, ClinicalTrials.gov, the World Health Organization (WHO) Portal (ICTRP) and Web of Science with conference proceedings.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the effectiveness of any one centrally acting pharmacological agent that affects one or more of the main neurotransmitter systems in people with chronic traumatic brain injury; and there had to be a minimum of 12 months between the injury and entry into the trial.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors examined titles and abstracts of citations obtained from the search. Relevant articles were retrieved for further assessment. A bibliographic search of relevant papers was conducted. We extracted data using a standardised tool, which included data on the incidence of adverse effects. Where necessary we requested additional unpublished data from study authors. Risk of bias was assessed by a single author.

Main results

Only four studies met the criteria for inclusion, with a total of 274 participants. Four pharmacological agents were investigated: modafinil (51 participants); (−)‐OSU6162, a monoamine stabiliser (12 participants of which six had a TBI); atomoxetine (60 participants); and rivastigmine (157 participants). A meta‐analysis could not be performed due to the small number and heterogeneity of the studies.

All studies examined cognitive performance, with the majority of the psychometric sub‐tests showing no difference between treatment and placebo (n = 274, very low quality evidence). For (−)‐OSU6162 modest superiority over placebo was demonstrated on three measures, but markedly inferior performance on another. Rivastigmine was better than placebo on one primary measure, and a single cognitive outcome in a secondary analysis of a subgroup with more severe memory impairment at baseline. The study of modafinil assessed clinical global improvement (n = 51, low quality evidence), and did not find any difference between treatment and placebo. Safety, as measured by adverse events, was reported by all studies (n = 274, very low quality evidence), with significantly more nausea reported by participants who received rivastigmine compared to placebo. There were no other differences in safety between treatment and placebo. No studies reported any deaths.

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence to determine whether pharmacological treatment is effective in chronic cognitive impairment in TBI. Whilst there is a positive finding for rivastigmine on one primary measure, all other primary measures were not better than placebo. The positive findings for (−)‐OSU6162 are interpreted cautiously as the study was small (n = 6). For modafinil and atomoxetine no positive effects were found. All four drugs appear to be relatively well tolerated, although evidence is sparse.

Keywords: Adolescent, Adult, Aged, Humans, Middle Aged, Atomoxetine Hydrochloride, Atomoxetine Hydrochloride/therapeutic use, Benzhydryl Compounds, Benzhydryl Compounds/therapeutic use, Brain Injuries, Brain Injuries/complications, Chronic Disease, Cognition, Cognition/drug effects, Cognition Disorders, Cognition Disorders/drug therapy, Cognition Disorders/etiology, Modafinil, Nootropic Agents, Nootropic Agents/therapeutic use, Piperidines, Piperidines/therapeutic use, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Rivastigmine, Rivastigmine/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Drug treatments for chronic cognitive impairment in traumatic brain injury

Background: Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major cause of long‐term disability across the world. The disability is often related to chronic cognitive impairment, such as changes to memory, attention and problem solving.

Method: We reviewed randomised controlled trials investigating the efficacy of any of the drugs commonly used to treat cognitive impairment after TBI. We included only studies which started treatment at least 12 months after the injury; by this time the cognitive impairment is usually stable.

Results: We identified only four trials for inclusion. These investigated four different drugs—modafinil; the experimental drug (−)‐OSU6162; atomoxetine; and rivastigmine—against placebo. On most measures there was no difference between treatment and placebo. Furthermore, the quality of the evidence was assessed as very low.

The experimental drug called (−)‐OSU6162 was better than placebo on three cognitive measures, although this was a small study with only six participants with TBI. Modafinil, atomoxetine and rivastigmine were not found to be better than placebo. No difference between modafinil and placebo was found on assessment of clinical global improvement. Compared to placebo, more participants on modafinil and fewer on rivastigmine dropped out of the trials. More people taking modafinil, atomoxetine and rivastigmine experienced adverse effects than those on placebo, although the difference is most likely due to chance. Only nausea was statistically more likely in those taking rivastigmine. In the study of (−)‐OSU6162, one participant of three given placebo experienced adverse effects requiring a dose reduction, with no drop‐outs reported. No studies reported any deaths.

Conclusion: Recommendations for, or against, drug treatment of chronic cognitive impairment in TBI cannot be made on the basis of current evidence.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Pharmacological agents compared to placebo for chronic cognitive impairment in traumatic brain injury.

| Modafanil, (−)‐OSU6162, atomoxetine or rivastigmine compared to placebo for chronic cognitive impairment in traumatic brain injury | |||||

| Patient or population: Participants with chronic cognitive impairment in traumatic brain injury Settings: Inpatient or community Intervention: Drug treatment Comparison: Placebo (2 to 10 weeks) | |||||

| Outcomes | Effect of drug treatment for people with cognitive impairment in traumatic brain injury | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Cognitive performance on psychometric tests | The majority of sub‐tests showed no difference between treatment and placebo. Superiority over placebo was shown in one measure in Silver 2006 and several measures in Johansson 2012 and Johansson 2015. However, interpretation of these findings are cautioned. |

See comment. | 274 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 |

Data synthesis was not possible due to the heterogeneity of studies. |

| Clinical global improvement | A single study reported no difference between treatment and placebo. | See comment. | 51 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 |

Data synthesis was not possible as only one study reported a measure on clinical global improvement. |

| Acceptability | No differences between treatment and placebo were found. | See comment. | 274(4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 |

Data synthesis was not possible due to the heterogeneity of studies. |

| Safety | More nausea was reported in participants receiving rivastigmine than placebo (Silver 2006). No other differences were found. | See comment. | 274 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 |

Data synthesis was not possible due to the heterogeneity of studies. |

| Mortality | No deaths were reported by any study. | Not estimable. | 274 (4 studies) | ‐ | |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1 downgraded one level due to serious indirectness, as two of four studies did not investigate cognitive impairment as a primary outcome

2 downgraded one level due to serious inconsistency, due to wide variance of point estimates.

3 downgraded one level due to serious imprecision, as the total population size was less than 400.

Background

Description of the condition

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) can result from closed‐head injury, penetrating‐head injury or a combination thereof. Penetrating‐head injury can affect any region of the brain while closed‐head injury, which includes rapid acceleration‐deceleration injury, can result in focal lesions but always causes diffuse damage. Diffuse damage consists of a combination of one or more of diffuse axonal injury (DAI), hypoxic brain damage, vascular injury, and swelling (Adams 1991), which frequently involve the white matter of the frontal lobes, the corpus callosum and the corona radiata (Gentry 1988). TBI varies widely in its severity. The commonest form, mild TBI, by definition, is associated with altered mental state at the time of injury; either no or brief (under 30 minutes) loss of consciousness; Glasgow Coma Scale score 13 to 15 after 30 minutes; and post‐traumatic amnesia less than 24 hours (Kay 1993). Mild TBI therefore encompasses a broad spectrum of severities, from feeling momentarily dazed following the trauma to 30 minutes loss of consciousness requiring hospital admission. In severe TBI the loss of consciousness or post‐traumatic amnesia can persist for one week or longer, sometimes even weeks to months (Silver 2008).

TBI is a major cause of chronic disability, even following mild injury (Thornhill 2000). Worldwide, it is the leading cause of disability in the under 40s, resulting in severe disability in some 150 to 200 million people per annum (Fleminger 2005). Neuropsychiatric sequelae of varying severity (which include problems with attention, arousal, concentration, executive functioning, memory impairment, personality change, affective disorders, anxiety, psychosis, aggression and irritability), occur in over two‐thirds of survivors while the vulnerability for such complications can persist for decades (Koponen 2002; Himanen 2006; Silver 2008). The majority of those with mild TBI show significant improvement of their symptoms over the first 6 months (Bernstein 1999); but if symptoms have not resolved by 6 to 12 months, they tend to persist (Brown 1994). Those with moderate to severe TBI show significant improvement of cognitive function over the first year following injury (Tabaddor 1984), but improvement appears to plateau by the end of year two (Whyte 2013).

In addition to mood and behavioural problems, memory, attention and executive function are commonly impaired by TBI (Lippert‐Gruner 2006), and prove difficult to remedy (Salazar 2000). Selective attention, the attending to chosen information at the expense of other stimuli, is mediated bottom‐up by the ascending reticular activating system and top‐down by the prefrontal, parietal and limbic cortices (Aharon‐Peretz 2007). Those with TBI demonstrate slowed reaction times, poor sustained attention, difficulty in ignoring task‐irrelevant information and perform poorly on tests of divided attention (Aharon‐Peretz 2007). The Central Executive System (CES) component of working memory appears to be particularly vulnerable in TBI, and impairment is associated with other symptoms of the dysexecutive syndrome (McDowell 1997). Executive dysfunction may partly explain problems with recall of long‐term episodic and semantic memory, due to an ineffective search strategy, though damage in the medial temporal lobes or diencephalic structures will cause anterograde amnesia that is characterised by impaired recall and recognition. Closed‐head injury tends to cause cognitive impairment in multiple domains whereas penetrating injuries can result in a focal cognitive deficit.

The UK's 'National Service Framework for Long Term Conditions' (DH) has highlighted the need for comprehensive interdisciplinary care that improves people's quality of life and carers' distress. Neurocognitive problems following TBI are one of the most important factors in determining people's subjective well‐being and their quality of life (Teasdale 2005). Hence, the focus is on improving neurocognitive functions, which may include the use of pharmacological approaches in addition to traditional neurorehabilitation.

Description of the intervention

The interventions to be studied are all widely‐available, centrally acting pharmacological agents that affect one or more of the major neurotransmitter systems (dopaminergic, serotonergic, GABAergic, glutamatergic and cholinergic) that are thought to underpin cognitive functions.

How the intervention might work

The neurotransmitter changes caused by traumatic brain injury have been far more extensively researched in the acute phase of brain injury than in chronic TBI (Mysiw 1997). During the acute phase the location of the injury results in different patterns of altered neurotransmitter function (Van Woerkom 1977). However, there are reasons to suspect that pharmacological manipulation of neurotransmitter systems in chronic TBI could enhance cognitive function.

Animal neurotransmitter studies have shown dopamine (DA) is found in high concentrations in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate, areas known to be intimately involved in working memory, attention and executive cognitive functioning (Previc 1999). The noradrenergic (NA) neurones originate in the locus coeruleus and lateral tegmental area and project into the cerebellum and hippocampus as well as diffusely through the cerebral cortex. Both NA and DA are known to play significant roles in arousal, motivation, learning and memory (Cooper 1991a; Cooper 1991b).

Severe TBI (acute Glasgow coma scale (GCS) ≤ 8) with diffuse axonal injury is associated with reduced turnover of 5‐hydroxy tryptophan (5HT). The serotonergic system is implicated in the function of the reticular activating system (RAS) and hippocampus, involved in alertness and memory respectively (Van Woerkom 1990). The serotonergic system, which projects from the midline raphe to the limbic system, neostriatum, thalamus and cerebellar and cerebral cortices, is involved in arousal, memory, mood and learning (Cooper 1991c).

There are two main cholinergic systems. The basal forebrain cholinergic complex includes the nucleus basalis of Meynert, septal nuclei and the nucleus of the diagonal band. A second system arises from the pedunculopontine and laterodorsal tegmental nuclei and these project to the thalamus, cerebellum and ascending reticular formation. The cholinergic system therefore helps maintain arousal and has been found to increase neuronal responsiveness to sensory input (Heilman 1993). An increase in cholinergic function is necessary for tasks requiring sustained and divided attention, maintaining vigilance, neural plasticity required for laying down memory and recognition memory (Tenovuo 2006). It has been suggested that following TBI there is a perturbation of cholinergic systems (Hayes 1989). After an acute period of increased cholinergic activity, a long‐standing hypocholinergic state develops. Structures in the medial temporal lobes, such as the hippocampus and limbic system that are rich in cholinergic neurons, are highly susceptible to traumatic and hypoxic injury (Arciniegas 1999).

Why it is important to do this review

Whilst Poole and Agrawal examined the role for cholinergic agents in TBI (Poole 2008), there has not yet been a systematic review or meta‐analysis of all commonly used psychotropic drugs in chronic cognitive impairment. Given the lack of knowledge of chronic changes in neurotransmitter systems following TBI the authors believed that it was sensible to study all psychotropic drugs that modulate the main neurotransmitter systems (noradrenaline, dopamine, serotonin, glutamate, acetylcholine).

Objectives

To assess the effects of centrally acting pharmacological agents for treatment of chronic cognitive impairment subsequent to traumatic brain injury in adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

As outlined in the protocol (Poole 2011), we only included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or cross‐over design studies assessing the effectiveness of any one centrally acting pharmacological agent that affects one or more of the main neurotransmitter systems in people with chronic traumatic brain injury (12 months or longer since the injury). We chose twelve months as a suitable time point because the majority of spontaneous biological improvement in neurocognitive functions takes place within this period (Brooks 1976); and only a few people show significant spontaneous recovery after 12 months (Jennett & Bond 1975). However, we acknowledge that any chosen time point is somewhat arbitrary. We only included trials if treatment with the pharmacological agent was compared with a placebo control group, and required that included trials showed evidence of concealment of allocation to treatment and control groups.

Types of participants

Human adults who have sustained mild to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) resulting in chronic cognitive impairment.

Types of interventions

1) Antidepressants

2) Antipsychotics

3) Dopamine agonists

4) Cholinergic agents

5) Psychostimulants

The authors reviewed trials investigating all centrally acting pharmacological agents that modulate the main neurotransmitter systems.

We did not review combinations of pharmacological agents because pharmacodynamic and kinetic factors would obscure the results.

We required that the intervention must be instigated 12 months or more after the injury.

Types of outcome measures

We required all outcome measures to be valid measures of the domain in question (that is tests of memory must be validated as such). However, we expected a wide variety of measures to be employed across studies and so we did not require that each one has been validated in the TBI population as this was anticipated to limit the number of studies that could be included. We required outcome measures to have demonstrated a high test‐retest reliability (> 0.8) in studies assessing their psychometric properties.

Primary outcomes

• Global severity of cognitive impairment

• Memory performance on psychometric tests

• Performance on neuropsychological tests that evaluate other aspects of cognitive functioning

• Scores on screening measures assessing cognitive function or general severity of cognitive impairment (e.g. mini–mental state examination (MMSE), Cambridge cognitive assessment (CAMCOG), Alzheimer disease assessment scale‐cognitive (ADAS‐Cog) or clinical dementia rating (CDR) scale

• Clinical global impression of change

Secondary outcomes

• Acceptability of treatment (as measured by withdrawal from trial)

• Safety (as measured by incidence of adverse effects)

• Mortality

• Subjective benefit (as measured by a validated tool)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched ALOIS (www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/alois)—the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group’s Specialised Register—on 16 November 2011, 23 February 2013, 20 January 2014 and 30 December 2014. The search terms used were: traumatic OR TBI OR "brain injury" OR "brain injuries" OR TBIs OR "axonal injury" OR "axonal injuries".

ALOIS is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group and contains studies in the areas of dementia prevention, dementia treatment and cognitive enhancement in healthy people. The studies are identified from:

Monthly searches of a number of major healthcare databases: MEDLINE (Ovid SP), EMBASE (Ovid SP), CINAHL, (EBSCOhost), PsycINFO (Ovid SP) and LILACS (BIREME)

Monthly searches of a number of trial registers: ISRCTN; UMIN (Japan's Trial Register); the WHO portal (which covers ClinicalTrials.gov; ISRCTN; the Chinese Clinical Trials Register; the German Clinical Trials Register; the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials; and the Netherlands National Trials Register; plus others)

Quarterly search of The Cochrane Library’s Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Six‐monthly searches of a number of grey literature sources: ISI Web of Knowledge Conference Proceedings; Index to Theses; Australasian Digital Theses

To view a list of all sources searched for ALOIS see About ALOIS on the ALOIS website.

Details of the search strategies used for the retrieval of reports of trials from the healthcare databases, CENTRAL and conference proceedings can be viewed in the ‘Methods used in reviews’ section within the editorial information about the Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group.

We performed additional searches in many of the sources listed above to cover the timeframe from the last searches performed for ALOIS to ensure that the search for the review was as up to date and as comprehensive as possible. The search strategies used can be seen in Appendix 1.

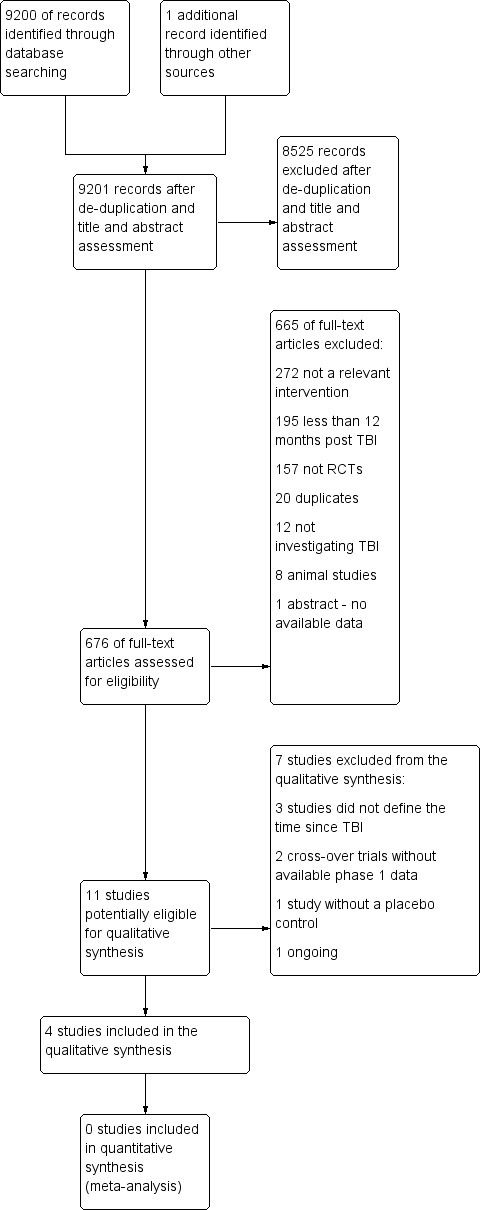

The searches retrieved a total of 9200 results. After a first‐assess and a de‐duplication, 676 references were left to further assess for possible inclusion or exclusion within the review.

Searching other resources

The authors handsearched the bibliographies of all relevant papers identified for any additional citations and also consulted experts and pharmaceutical companies to check for any omissions from our identified studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors (DD and NP) examined titles and abstracts of citations obtained from the search, and obviously irrelevant articles were discarded. An article was retrieved for further assessment in the presence of any suggestion that the article described a relevant randomised controlled trial.

Two authors (DD and NP) independently assessed the retrieved articles for inclusion in the review according to the criteria above. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Two authors (DD and NP) extracted data. If any differences emerged then agreement was reached by consensus. The authors extracted data from the published reports using standardised tools. In addition to summary statistics for each trial and each outcome we extracted details on the number and types of participants, the interventions, randomisation and blinding. For continuous data we extracted the mean change from baseline, the standard error of the mean change, and the number of participants for each treatment group at each assessment. For binary data we sought the numbers in each treatment group and the numbers experiencing the outcome of interest. We requested additional data from the original study authors if this data was unavailable in the published paper.

We defined the baseline assessment as the latest available assessment prior to randomisation, but no longer than two months before.

We sought data for each outcome measure and on every person assessed.

In studies where a cross‐over design was used, we only extracted data from the first treatment phase after randomisation.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The same review author (DD) assessed the methodological quality of all studies included in the review. The author used the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool as described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), to assess the methods used by each study to control six potential sources of bias (sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias). Overall quality of evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach (Schünemann 2011).

The authors gave particular emphasis to allocation concealment, as empirical research has shown that a lack of adequate allocation concealment is associated with bias. Trials with unclear concealment measures have been shown to yield more pronounced estimates of treatment effects than trials that have taken adequate measures to conceal allocation schedules, but this is less pronounced than for inadequately concealed trials (Chalmers 1983; Schulz 1995). Thus trials were included if they were of low or unclear risk, whilst those assessed as high risk were not.

Measures of treatment effect

The authors expressed the treatment effect for continuous outcomes, as the mean difference. For dichotomous outcomes, we expressed risk ratios which for clinicians are easier to interpret than odds ratios. We did not report treatment effects in terms of number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) as the data extracted gave mean changes from baseline only and could not be interpreted in terms of treatment response.

Unit of analysis issues

The authors only included data from the first treatment phase after randomisation in studies of a cross‐over design.

Dealing with missing data

The authors sought intention‐to‐treat data but, if unavailable in the publications, we included 'on‐treatment' data or the data for those who completed the trial.

Assessment of heterogeneity

The authors did not conduct an assessment of heterogeneity as the three studies identified were clinically heterogeneous and results were not pooled.

Assessment of reporting biases

The authors minimised the potential for publication bias by contacting study authors, pharmaceutical companies and experts to assist in the identification of unpublished studies. Furthermore, we contacted authors of identified studies to enquire about duplication of studies and outcome reporting bias.

We did not create a funnel plot as an insufficient number of studies were identified.

Data synthesis

We deemed data synthesis to be inappropriate due to the small number of studies identified, which also differed in interventions and outcome measures.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not assess for statistical heterogeneity as data synthesis was not possible.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not conduct sensitivity analyses as we did not conduct data synthesis.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The results of the search are summarised in Figure 1. A total of 9200 records were identified after removal of duplicates and first assessment. One additional paper was identified after contacting a study author (Johansson 2015). A total of 676 papers were reviewed for suitability for inclusion, of which four studies met the criteria for inclusion. Two cross‐over studies could not be included as they did not report separate phase one outcome data, which the authors were unable to provide when contacted (Speech 1993; Tenovuo 2009). One study did not include a placebo control group (Johansson 2015). One study investigating rivastigmine was identified to be ongoing, and is described in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The four studies meeting inclusion criteria are described in the Characteristics of included studies tables. One study investigated modafinil (Jha 2008), a wake‐promoting agent with effects on multiple neurotransmitter systems, including histaminergic, serotonergic, and glutaminergic activity that may be secondary to stimulation of catecholamine systems (Minzenberg 2008). The second investigated (−)‐OSU6162 (Johansson 2012), a monoamine stabiliser agent with dopaminergic (Lahti 2007), and serotonergic effects (Burstein 2011; Carlsson 2011). The third investigated atomoxetine (Ripley 2014), a noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (Zerbe 1985). Lastly, Silver 2006 investigated rivastigmine which is an acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitor (Giacobini 2002). Three studies (Jha 2008, Ripley 2014 and Silver 2006) were conducted in the United States, whilst Johansson 2012 was conducted in Sweden.

Jha 2008 is a single centre randomised placebo‐controlled crossover trial, examining the efficacy of modafinil in the treatment of fatigue or excessive day‐time sleepiness, which included secondary measures assessing global and cognitive function. Fifty‐one men and women aged 16 to 65 were recruited from an inpatient rehabilitation unit. For inclusion, participants were required to suffer from fatigue or excessive daytime sleepiness that compromised functioning. Although the mean baseline ImPACT (Immediate Post Concussion Assessment Cognitive Testing) score was provided for the group this is difficult to interpret. The ImPACT is a neuropsychological test which compares the subject against aged‐matched normative data. It would therefore be important to know the baseline for each individual to ascertain the degree of cognitive impairment at baseline. Relevant exclusion criteria were: the presence of a neurological or neuropsychiatric diagnosis that would impair evaluation of the intervention; other diagnoses that may cause excessive daytime sleepiness; concurrent medication use; clinically significant systemic medical conditions; epilepsy; cardiovascular disease; severe hepatic or renal impairment; psychiatric or behavioural disturbance that would impair evaluation of the intervention; pregnancy. In the treatment arm, modafinil was titrated to 200 mg twice daily orally over a two‐week period and continued for a further eight weeks. Participants in the placebo arm were administered tablets at the same frequency as for modafinil. After a four‐week washout period participants were switched to the opposite arm. The primary outcome measures of the study related to fatigue and daytime sleepiness. Relevant cognitive or global outcome measures included the Medical Outcome Study 12‐Item Short Form Survey (SF‐12), ImPACT, and the Conners' Continuous Performance Test II (CPT‐II). The measures were administered at baseline, week four and week ten of treatment (repeated at week four and ten following cross‐over). Only results from the first treatment phase were included in this review. We contacted the study authors who provided unpublished phase one outcome data for cognitive outcomes and adverse effects.

Johansson 2012 is a single centre cross‐over randomised placebo controlled study, examining the efficacy of (−)‐OSU6162 on long‐term mental fatigue following TBI or stroke. Twelve men and women aged 30 to 65 were recruited through a local Swedish newspaper advertisement or from the Department of Neurology at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg. Participants were included if they were at least one year post‐TBI or stroke, but not more than 10 years, and had suffered pathological mental fatigue for at least one year. Participants were required to have otherwise recovered from neurological symptoms, have a Glasgow Outcome Scale (Extended) (GOS‐E) score indicating at least moderate disability or better (> 5), and have completed education to high school equivalent and speak Swedish. Participants were excluded if they were deemed to suffer significant cognitive impairment, as measured by scores more than two standard deviations worse on the cognitive tests used by the study, or in the case of significant neurological or psychiatric comorbidity, substance misuse, or pregnancy. Participants receiving (−)‐OSU6162 were administered 15 mg twice daily in week one, 30 mg twice daily in week two, and 45 mg twice daily in weeks three and four. Dose variation was possible if a participant had responded at a lower dose and then experienced decreased efficacy or adverse effects at a higher dose, therefore permitting a reduction to the previous dose. The process of administration in the placebo arm was not explicitly described. The primary outcome measure of the study assessed fatigue. The relevant secondary cognitive outcome measures were the Trail Making Tests A,B,C & D, WAIS‐III digit symbol coding, WAIS‐III digit span and the FAS verbal fluency test. These were administered at baseline and four weeks. A week 8 assessment was conducted following the crossover, the results of which are not relevant to this review. We contacted the study authors, who provided unpublished outcome data specific to TBI participants in phase one of the trial.

Ripley 2014 is a single centre randomised placebo‐controlled cross‐over trial, examining the efficacy of atomoxetine in the treatment of attention impairment. Sixty men and women aged 18 to 65 were recruited by posting flyers to people who had received inpatient rehabilitation following TBI, or through clinicians handing leaflets to people with TBI in the community. Flyers were also distributed to various brain injury organisations. For inclusion, participants were required to have a history of moderate to severe TBI, defined by a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 12 or less, post‐traumatic amnesia which lasted more than 24 hours or radiographic evidence of intracranial trauma. Telephone screening was conducted to administer the Adult ADHD Self‐Report Scale (ASRS‐v1.1) and the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ). The Other CFQ was also administered if a primary carer or significant other was available. A score of four or higher on the ASRS, 0.35 or higher on the CFQ, or 0.42 or higher on the Other CFQ was required for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were: non‐English speaking participants; current seizure history; cardiovascular disease; history of psychiatric illness requiring hospital treatment; use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors; severe renal or hepatic impairment; pregnancy or lactating. After baseline assessment all participants received a placebo run‐in for two weeks. In the treatment arm, atomoxetine 40 mg was administered twice a day for two weeks. Participants in the placebo arm were administered tablets of identical appearance according to the same schedule. After a two‐week placebo washout period participants were switched to the opposite arm for a further two weeks. The primary outcome measure of the study was the Power of Attention factor of the Cognitive Drug Research (CDR) Computerized Cognitive Assessment System. The CDR is a computer‐controlled battery of tests that provides factor scores for Power of Attention (POA), Continuity of Attention (COA), Quality of Working Memory (QWM), Quality of Episodic Memory (QEM), and Speed of Memory (SOM). Secondary measures in the study included COA, QEM and SOM factor scores of the CDR. Further secondary measures were the Efficiency of Attention score calculated from the Power of Attention score, Stroop Colour and Word Test, the Adult ADHD Self‐Report Scale and Neurobehavioral Functioning Inventory scores. Only results from the first treatment phase were included in this review. The study authors provided unpublished phase one outcome data for cognitive outcomes and adverse effects on request.

Silver 2006 is a multicentre randomised placebo controlled trial examining the efficacy of rivastigmine on cognitive function. One‐hundred and fifty men and women aged 18 to 50 were recruited across 19 sites. Participants with cognitive impairment following non‐penetrating traumatic brain injury were included. At baseline, participants were required to have a difference of at least one standard deviation between current estimated intelligence measured by the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, third edition (WAIS‐III) and current verbal attention or verbal memory functioning measured by the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery Rapid Visual Information Processing A subtest (CANTAB RVIP A) or the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT) total trials one to three. Relevant exclusion criteria were: medical, psychiatric or substance use disorders that could impair evaluation of the intervention; acute or severe pulmonary or cardiovascular disease; primary neurodegenerative disorders; epilepsy; medication known to affect cognitive functioning in TBI; history of major brain surgery or penetrating brain injury. Participants receiving rivastigmine started at 1.5 mg twice daily for four weeks, after which the dose was increased to 3 mg twice daily. If not tolerated due to adverse side effects, the dose could either be reduced to 4.5 mg or 3 mg daily (also in divided doses). A matching placebo was administered according to the same schedule as for rivastigmine. Primary outcome measures were the CANTAB RVIP A and the HVLT. These were administered at baseline and weeks four, eight and twelve. Secondary outcome measures were only administered at baseline and week twelve, and included; Controlled Oral Word Association; WAIS‐III Digit span; WAIS‐III Letter Number Sequencing; and Trail Making Tests Parts A and B. We contacted the study authors for additional data, which was unavailable. Therefore, outcomes for the Neurobehavioral Functioning Inventory (NFI), Diener Satisfaction with Life Scale, and Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGI) could not be reported.

Excluded studies

We excluded two cross‐over studies as neither reported phase 1 outcome data, which the authors were unable to provide when contacted (Speech 1993; Tenovuo 2009). We excluded three other studies as the time since TBI was not clearly stated (León‐Carrión 2000; Plenger 1996; Schneider 1999). One study (Johansson 2015) was excluded as the control group did not receive a placebo.

Risk of bias in included studies

Judgements for risks of bias are detailed in the Characteristics of included studies section and summarised in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Jha 2008 and Ripley 2014 described adequate procedures to reduce selection bias and were rated as low risk. Johansson 2012 did not describe the randomisation process, other than reporting that an external system was employed; therefore we rated the study as unclear risk for random sequence generation, and low risk of allocation concealment due to the use of an external process. A limited description of the randomisation and concealment process was provided by Silver 2006; therefore we rated the risks of bias as unclear.

Blinding

All studies were assessed to be of low risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed risk of attrition bias as high in Jha 2008 as not all participants who were randomised were included in the analysis and reference was not made to intention‐to‐treat analysis. We assessed Johansson 2012, Ripley 2014 and Silver 2006 as low risk.

Selective reporting

Outcomes were reported as planned in the protocol by Jha 2008, Johansson 2012, and Ripley 2014 , and therefore we assessed reporting bias as low risk.

Silver 2006 varied from the protocol in terms of inclusion criteria and outcome measurement time‐scales. The published protocol registered with ClinicalTrials.gov planned to include participants aged 18 to 65, while the published study states the inclusion criteria as 18 to 50 years. Of more concern, a different cognitive battery was used in the study to that proposed in the protocol to determine inclusion into the trial. The protocol included subjects one standard deviation or more below the mean on the California Verbal Learning test, Tower of London test, Verbal Memory Learning test and the Test Battery for Attentional Performance. However, the completed study included subjects who performed below one standard deviation on the Verbal subtest on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) and attention or verbal memory as assessed by the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery CANTAB), Rapid Visual Information processing (RVIP), or the Hopkins Verbal learning Test (HVLT). Also, the protocol planned for treatment for 20 weeks, as opposed to 12 weeks in the completed study. Both these discrepancies appear to have been balanced across both arms of the study: we therefore assessed the risk of bias as low.

Other potential sources of bias

Only Ripley 2014 and Silver 2006 investigated treatment of cognitive impairment as a primary outcome measure, with Jha 2008 and Johansson 2012 primarily investigating treatment of fatigue. Limited information on the severity of TBI was provided by the studies, and similarly limited data on baseline cognitive impairment at inclusion were provided. These factors may have introduced bias through variation in the recruitment or selection of participants, and consequently assessment of outcome.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Each of the reported studies included measures relating to one of the primary outcomes of this review: namely, cognitive function as assessed by standardised psychometric tests. Of the four studies, only Ripley 2014 and Silver 2006 reported cognitive function as a primary outcome measures. Primary outcome measures for Jha 2008 were for fatigue; and for Johansson 2012, mental fatigue. Reported secondary measures included safety and acceptability data. Due to the small numbers, we have reported outcomes separately for each study. Synthesis of data was not possible, with sub‐tests of psychometric batteries favouring both treatment and placebo arms, as shown in Table 1.

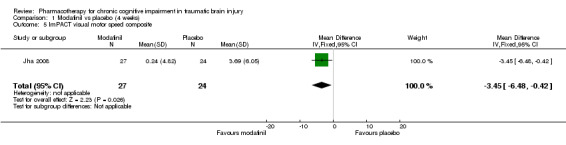

In Jha 2008 unpublished data for relevant cognitive outcomes were provided by the study authors. These data were generated by the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), rather than the original statistician’s Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) syntax for the mixed model used in the published paper. Consequently this resulted in different mean scores compared to the original study, but not to the significance of the findings. A single significant difference at week 4 was found in ImPACT visual motor speed composite score, which was not attributable treatment, as there was a positive change in the placebo arm, whilst the score in the modafinil arm remained essentially unchanged (Analysis 1.5). At week 10, no significant differences between modafinil and placebo were found on all relevant measures, including the SF‐12 mental, SF‐12 physical, ImPACT verbal memory composite, ImPACT visual memory composite, ImPACT visual motor speed composite, ImPACT reaction time composite, CCPT‐II number of omissions or CCPT‐II number of commissions (Analysis 2.1 to Analysis 2.8).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Modafinil vs placebo (4 weeks), Outcome 5 ImPACT visual motor speed composite.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Modafinil vs placebo (10 weeks), Outcome 1 SF‐12 Physical.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Modafinil vs placebo (10 weeks), Outcome 8 CCPT‐II No. of commissions.

The Modafinil group experienced more adverse events than those taking placebo. However, there were no significant differences in the effect estimates (Analysis 7.1 to Analysis 7.10). Two participants in the treatment arm left the trial early versus none in the control group. Again, this was not statistically significant (Analysis 6.1). No deaths were reported during the study.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Modafinil vs placebo adverse events, Outcome 1 Dizziness.

7.10. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Modafinil vs placebo adverse events, Outcome 10 Unknown.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Acceptability of treatment, Outcome 1 Modafinil vs placebo.

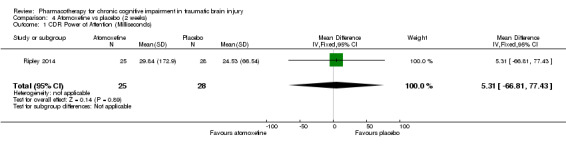

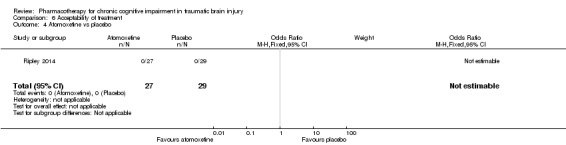

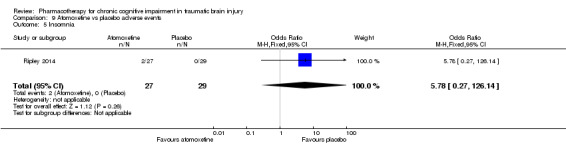

In Ripley 2014 atomoxetine was found not to be significantly different from placebo on all cognitive test (Analysis 4.1 to Analysis 4.5). There was no difference in acceptability, with no drop outs reported during the first treatment phase (Analysis 6.4). Numerically more side effects were reported with atomoxetine, but there were no significant differences in effects estimates (Analysis 9.1 to Analysis 9.10). These analyses accord with the findings of the original paper (Ripley 2014), in which no statistical difference between atomoxetine and placebo was found, when pre‐ and post cross‐over phases were combined in the analysis.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Atomoxetine vs placebo (2 weeks), Outcome 1 CDR Power of Attention (Milliseconds).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Atomoxetine vs placebo (2 weeks), Outcome 5 Adult ADHD Self‐Report Scale (ASRS‐v1.1.).

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Acceptability of treatment, Outcome 4 Atomoxetine vs placebo.

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Atomoxetine vs placebo adverse events, Outcome 1 Headache.

9.10. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Atomoxetine vs placebo adverse events, Outcome 10 Urinary retention.

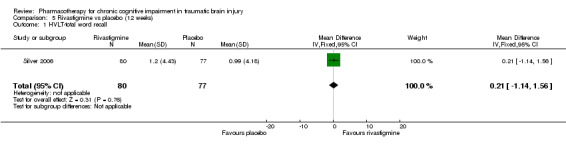

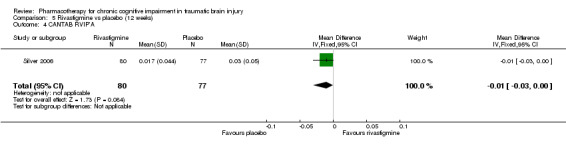

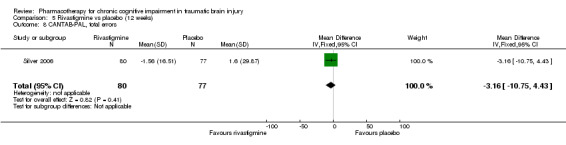

In Silver 2006 rivastigmine was found not to be significantly different from placebo on all cognitive tests (Analysis 5.1 to Analysis 5.5, and Analysis 5.7 to Analysis 5.12) apart from an effect estimate favouring rivastigmine according to the CANTAB RVIP, mean latency (−44.54 milliseconds, 95% CI −88.62 to −0.46 Analysis 5.6). However, Silver 2006 did not report a significant difference for this measure (P = 0.129), which may be explained by the use of a different statistical test. On a secondary analysis of a subgroup of participants with greater cognitive impairment at baseline, as measured by at least 25% impairment on the HVLT, significant superiority of rivastigmine over placebo was found on the CANTAB RVIP mean latency test at weeks four and 12 (reported by the study in graphical format only). Numerical data other than a P value of < 0.05 were not reported, and were not available when requested from the study authors.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Rivastigmine vs placebo (12 weeks), Outcome 1 HVLT‐total word recall.

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Rivastigmine vs placebo (12 weeks), Outcome 5 CANTAB–SWM, total errors.

5.7. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Rivastigmine vs placebo (12 weeks), Outcome 7 CANTAB‐RT, simple reaction time, ms.

5.12. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Rivastigmine vs placebo (12 weeks), Outcome 12 WAIS‐III‐DS scaled score.

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Rivastigmine vs placebo (12 weeks), Outcome 6 CANTAB RVIP, mean latency, ms.

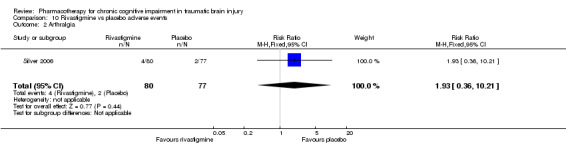

Placebo was numerically slightly less acceptable than rivastigmine (Analysis 6.2). Rivastigmine was numerically less safe than placebo as measured by adverse effects, with a higher rate of nausea in participants given rivastigmine the only significant difference compared to placebo (19/80, 23.8% versus 6/77, 7.8%, risk ratio 3.05, 95% CI 1.29 to 7.22 Analysis 10.6). No deaths were reported during the study.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Acceptability of treatment, Outcome 2 Rivastigmine vs placebo.

10.6. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Rivastigmine vs placebo adverse events, Outcome 6 Nausea.

In Johansson 2012 data for phase 1 TBI participants were provided by the study authors. Effect estimates showed significantly higher scores for (−)‐OSU6162 than placebo for Trail Making Test A (−9.20 seconds, 95% CI −12.19 to −6.21 Analysis 3.1), Trail Making Test B (−6.20 seconds, 95% CI, −7.81 to −4.59 Analysis 3.2) and WAIS‐III Digit symbol coding (8.60, 95% CI 6.47 to 10.73 Analysis 3.5) showed significantly higher scores for (−)‐OSU6162 than placebo. Trail Making Test D strongly favoured placebo (53.80 seconds, 95% CI 36.76 to 70.24 Analysis 3.4). No significant differences in effect estimates were found for Trail Making Test C, WAIS‐III digit span, and FAS verbal fluency (Analysis 3.3, Analysis 3.6 & Analysis 3.7). One participant required a dose reduction due to adverse effects in the placebo arm. There were no drop‐outs (TBI participants). No reference was made to deaths.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (−)‐OSU6162 vs placebo (4 weeks), Outcome 1 Trail Making Test A (seconds).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (−)‐OSU6162 vs placebo (4 weeks), Outcome 2 Trail Making Test B (seconds).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (−)‐OSU6162 vs placebo (4 weeks), Outcome 5 WAIS‐III Digit Symbol Coding.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (−)‐OSU6162 vs placebo (4 weeks), Outcome 4 Trail Making Test D (seconds).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (−)‐OSU6162 vs placebo (4 weeks), Outcome 3 Trail Making Test C (seconds).

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (−)‐OSU6162 vs placebo (4 weeks), Outcome 6 WAIS‐III Digit‐Span.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (−)‐OSU6162 vs placebo (4 weeks), Outcome 7 FAS Verbal Fluency (total words).

Discussion

Summary of main results

The search has found only seven RCTs (including six cross‐over trials) investigating the pharmacological treatment of chronic cognitive impairment at least 12 months after TBI, with five trials providing data suitable for inclusion. Two cross‐over trials that otherwise met criteria for inclusion were not included as phase one outcome data were unavailable. One trial was rejected as it did not include a placebo control group.

The pharmacological agents investigated were modafinil, rivastigmine, atomoxetine, and (−)‐OSU6162. Superiority over placebo for (−)‐OSU6162 was demonstrated in Trail Making Tests A, B and WAIS‐III digit symbol coding, but (−)‐OSU6162 was also inferior to placebo in Trail Making Test D (Johansson 2012). Superiority over placebo was not demonstrated for modafinil (Jha 2008); or atomoxetine (Ripley 2014). Superiority of rivastigmine over placebo was demonstrated by only one primary measure (CANTAB RVIP, mean latency) according to the effect estimate by this review. Interpretation of this finding is cautioned as Silver 2006 did not report a statistically significant difference, which may be attributed to a different statistical test used. In addition the confidence interval for the effect estimate is wide and approaches statistical non‐significance. Separately on a secondary analysis of a subgroup of participants assessed to have greater cognitive impairment, significant superiority of rivastigmine was demonstrated on a single measure (Silver 2006).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

No strong RCT evidence to support the pharmacological treatment of chronic cognitive impairment in TBI has been found by this review. However, when considering the significant disability associated with chronic TBI, pharmacological treatments may still be considered as part of a comprehensive management strategy for chronic cognitive impairment, including non‐pharmacological approaches for which there is reasonable evidence (Lu 2012).

Quality of the evidence

Since only four studies investigating different agents with heterogenous outcome measures met the criteria for inclusion, synthesis of outcomes was not possible. Only two studies concerned the treatment of cognitive impairment as a primary measure (Ripley 2014;Silver 2006), whilst the other two examined the impact on cognitive function as a secondary outcome, with primary outcomes concerned with the treatment of mental fatigue thereby limiting generalisability (Jha 2008; Johansson 2012). That Johansson 2012 also excluded participants with significant cognitive impairment further limits generalisability. The small study size of Johansson 2012, with only six TBI participants may have increased the risk of erroneous results. This study also assessed a relatively short period of treatment (four weeks). The majority of the data reported in this review for Jha 2008, Johansson 2012, and Ripley 2014 were also unpublished. Overall the studies were largely assessed to be at low or unclear risk of bias.

Using the GRADE approach, we rated the quality of evidence for cognitive performance on psychometric tests, acceptability and safety as very low. Quality was downgraded one level for each rating, due to: serious indirectness, as two of four studies did not investigate cognitive impairment as a primary outcome; serious inconsistency, due to wide variance of point estimates; and serious imprecision, as the total population size was less than 400. Quality of evidence for clinical global improvement was rated as low, downgraded due to serious indirectness, as the relevant study did not investigate cognitive impairment as a primary outcome; and serious imprecision, as the population size was less than 400.

Potential biases in the review process

Strengths of this review are that a comprehensive search strategy was employed, which together with a bibliographic search is likely to have identified all relevant studies. The title and abstract search and review of full‐text papers was conducted independently by two study authors (DD & NP) to reduce inclusion bias. A limitation was that a single‐author assessment of bias was conducted. A weakness of this review is that phase 1 data from two cross‐over studies were not available from the respective authors (Speech 1993;Tenovuo 2009), and therefore could not be included, reducing the number of included studies. However, only Tenovuo 2009 reported statistically significant results on two measures, which suggests the findings of this review would not have been substantially altered.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The findings of this review reflect those of Poole 2008 which found little high quality evidence for the pharmacological treatment of cognitive impairment in TBI; whilst no definitive evidence was found, the review concluded that there was suggestive evidence for cholinesterase inhibitors and choline. Another earlier review by Griffin 2003 concluded that there was only preliminary evidence for further investigation of cholinergic agents. Since Poole 2008 which reviewed the RCT by Silver 2006, only one further RCT relevant to this review has been published (Jha 2008). Methodological differences between this review and that by Poole 2008 and Griffin 2003 is that it is limited to chronic cognitive impairment, but is also broader by including drugs other than cholinergic agents.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Recommendations for the pharmacological treatment of chronic cognitive impairment in TBI cannot be made on the basis of RCT evidence despite a pharmacodynamic rationale, as disruption of cholinergic systems secondary to brain injury has been demonstrated (Heilman 1993; Tenovuo 2006; Arciniegas 1999). Potential benefits of treatments, even if modest, might still be considered in the context of the high prevalence (Fleminger 2005), and substantial disability associated with TBI (Thornhill 2000). In addition, there is no RCT evidence recommending against the use of pharmacological treatments which seem safe and well tolerated and the costs are reducing (with drugs such as donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine coming off patent).

The absence of clinical effectiveness of centrally acting pharmacological agents is in contrast to the developing evidence base for rehabilitative techniques such as environmental adaptations, errorless learning, external memory aids and retrieval stratagems recommended by experts in the field (Wilson 2002). The benefits of cognitive rehabilitation have also been supported by a recent review (Lu 2012).

Implications for research.

This review demonstrates the need for further RCTs to investigate the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments for chronic cognitive impairment in adults with traumatic brain injury. Future RCTs investigating cognitive impairment in chronic TBI in adults should define the severity of TBI, the degree of cognitive impairment at baseline, with inclusion only of participants who sustained TBI more than 12 months before. Studies are needed to determine the efficacy and acceptability of all of the types of interventions that this review sought to investigate, to include antidepressants, antipsychotics, dopamine agonists, cholinergics and psychostimulants compared to placebo. In assessing outcomes, in addition to the use of validated measures to assess global severity of cognitive impairment and memory performance, assessment of neurobehavioural symptoms of TBI, such as personality change and dysexecutive syndrome may be particularly worthwhile, as such symptoms may have profound adverse impact on both social and occupational functioning, and therefore illness burden.

An updated search of the literature is recommended in five years.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Sue Marcus for providing editorial support and Anna Noel‐Storr for conducting the initial and updated searches.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Sources searched and search strategies used

|

Source |

Search strategy | Hits retrieved |

| 1. ALOIS (www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/alois) [last searched 30 December 2014] |

Keyword search: traumatic OR TBI OR "brain injury" OR "brain injuries" OR TBIs OR "axonal injury" OR "axonal injuries" |

Dec 2011: 41 Feb 2013: 9 Jan 2014: 1 Dec 2014: 1 |

| 2. MEDLINE In‐process and other non‐indexed citations and MEDLINE 1950‐present (Ovid SP) [last searched 30 December 2014] |

1. randomized controlled trial.pt. 2. controlled clinical trial.pt. 3. randomized.ab. 4. placebo.ab. 5. drug therapy.fs. 6. randomly.ab. 7. trial.ab. 8. groups.ab. 9. or/1‐8 10. (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. 11. 9 not 10 12. ("drug treatment*" or "pharmacological treatment*" or pharmacotherapy).ti,ab. 13. Cholinergic Agents/ 14. (cholinomimetic or cholinergic*).ti,ab. 15. (arecolin* or arecholin*).ti,ab. 16. (meclofenoxat* or meclophenoxat*).ti,ab. 17. (centrofenoxin* or centrophenoxin*).ti,ab. 18. ("ANP 235" or "EN 1627").ti,ab. 19. (deanol* or demanol* or "CR 121" or "RS 86").ti,ab. 20. (physostigmin* or fysostigmin* or lecithin* or lecitin*).ti,ab. 21. (choline or cholin or coline).ti,ab. 22. (tacrin* or takrin*).ti,ab. 23. (tetrahydroaminoacridin* or tetrahydroaminacrin* or "CI 970" or THA or THAA).ti,ab. 24. ("7‐methoxyacridin*" or "7‐metoxyacridin*" or methoxytacrin* or metoxytacrin* or metoxytakrin* or methoxycrin* or metoxycrin* or MEOTA).ti,ab. 25. (ipidacrin* or amiridin* or NIK247 or "NIK 247").ti,ab. 26. (donepezil* or E2020 or "E 2020" or galanthamin* or galantamin* or "CGP 37267").ti,ab. 27. (rivastigmin* or ENA713 or "ENA 713" or "212 713").ti,ab. 28. (eptastigmin* or heptylstigmin* or heptylphysostigmin* or heptylfysostigmin*).ti,ab. 29. ("L 693 487" or MF201 or "MF 201" or metrifonat* or metriphonat*).ti,ab. 30. (trichlorfon* or trichlorphon* or trichlorfen* or trichlorphen* or "L 1359" or "Bay a 9826" or "Bay 1 1359").ti,ab. 31. (xanomelin* or "LY 246708" or "FG 10232" or cevimelin* or AF102B or "AF 102B'").ti,ab. 32. ("FKS 508" or "SND 5008" or SNK508 or SNI2011).ti,ab. 33. or/12‐32 34. Antidepressive Agents/ 35. Antidepressive Agents, Second‐Generation/ 36. Antidepressive Agents, Tricyclic/ 37. (Amesergide or amineptine hydrochloride or amitriptyline).ti,ab. 38. (amoxapine or "benactyzine hydrochloride" or brofaromine or "bupropion hydrochloride" or "butriptyline hydrochloride").ti,ab. 39. (cianopramine or "citalopram hydrobromide" or clomipramine or "clorgyline hydrochloride" or clovcxamine).ti,ab. 40. ("demexiptiline hydrochloride" or "desipramine hydrochloride" or "dibenzepin hydrochloride" or "dimetacrine tartrate" or "dothiepin hydrochloride" or "doxepin hydrochloride" or "etoperidone hydrochloride").ti,ab. 41. (femoxetine or "fezolamine fumarate" or "fluoxetine hydrochloride" or "fluvoxamine maleate").ti,ab. 42. (ifoxetine or "imipramine hydrochloride" or "iprindole hydrochloride" or "iproniazid phosphate" or isocarboxazid or levoprotiline or "lofepramine hydrochloride" or "maprotiline hydrochloride").ti,ab. 43. (medifoxamine or "melitracen hydrochloride" or "metapramine fumarate" or "mianserin hydrochloride" or milnacipran or "minapri hydrochloride" or mirtazapine).ti,ab. 44. (moclobemide or nefazodone hydrochloride or nialamide or nomifensine maleate or nortriptyline hydrochloride or opipramol hydrochloride or oxaflozane hydrochloride or oxaprotiline hydrochloride or oxitriptan).ti,ab. 45. (paroxetine hydrochloride or phenelzine sulphate or pirlindole or propizepine hydrochloride or protriptyline hydrochloride).ti,ab. 46. (quinupramine or rolipram or rubidium chloride or sertraline hydrochloride or setiptiline or sibutramine or teniloxazine or tianepine sodium or tofenacin hydrochloride).ti,ab. 47. (oloxatone or tranylcypromine sulphate or trazadone hydrochloride or trimipramine or tryptophan or venlafaxine hydrochloride or viloxazine hydrochloride or viqualine or zimelidine hydrochloride).ti,ab. 48. or/34‐47 49. Antipsychotic Agents/ 50. (clozapine or olanzapine or pirenzepine or sertindole or imidazoles or indoles).ti,ab. 51. (risperidone or quetiapine or ziprasidone or piperazines or thiazoles or sulpiride or zotepine or zotepine or amisulpride).ti,ab. 52. (sulpride or deniban or solian or socian or sulamid or DAN or abilify or OPC or clozaril or alemoxan or elcrit or froidir or klozapol).ti,ab. 53. (leponex or olasek or ziprexa or zyprexa or seroquel or risperdal or belivon or risperin).ti,ab. 54. (rispolept or rispolin or neripros or rizodal or serdolect or serlect or zoleptil or aiglonyl or alimoral or ansium).ti,ab. 55. (arminol or betamaks or calmoflorine or championyl or darleton or depex or depreal or desisulpid or digton or dixibon).ti,ab. 56. (dobren or dogmatil or dogmatyl or dolmatil or dresent or eclorion or eglonyl or enimon or equilid or esipride or fardalan).ti,ab. 57. (fidelan or intrasil or lebopride or mariastel or meresa or mirbanil or neogama or neoride or noneston or norestran).ti,ab. 58. (normum or nufarol or nylipark or omaha or omiryl or ozedeprin or paratil or prosulpin or psicocen or quastil).ti,ab. 59. (quiridil or restful or stamoneurol or sulp or sulparex or sulpiphar or sulpir or sulpirid or sulpiryd or sulpitil or sulpivert).ti,ab. 60. (sulpril or suprium or synedil or tepavil or tepazepam or valirem or neogamma or zemorcon or zeprid or zymocomb).ti,ab. 61. (geodon or zoleptil or Benperidol or anquil or benperidols or frenactil or glianimon or psichoben or Chlorpromazine).ti,ab. 62. (aminazins or ancholactil or biscasil or bukatel or chlorazin or chlorpromazin or clordezalin or fenactil or fleksin).ti,ab. 63. (kloproman or klorproman or largactil or largatrex or megaphen or Nevropromazine or Plegomazin or Propaphenin).ti,ab. 64. (prozil or prozin or repazine or solidon or tardyl or thorazine or zuledin or Flupentixol or depixol or fluanxel or fluanxol).ti,ab. 65. (Fluphenazine or anatensol or cardilac or cenilene or dapotum or decafen or decazate or decentan or eutimox).ti,ab. 66. (fludecate or flufenazin or lyogen or lyoridin or lyorodin or mirenil or modecate or moditen or omca or pacinol or permitil).ti,ab. 67. (prolixin or prolongatum or sevinol or siqualone or fludecasin or Haloperidol or alased or aloperidin or avant).ti,ab. 68. (bioperidolo or buteridol or cereen or decaldol or decanoate or dozic or duraperidol or fortunan or haldol or haloneural).ti,ab. 69. (haloper or haloperin or norodol or novo‐peridol or peridol or sedaperidol or serenace or serenelfi or sevium or sigaperidol).ti,ab. 70. (sylador or vesadol or vesalium or zafrionil or levomepromazine or methotrimeprazine or levium or levomepromazin).ti,ab. 71. (levoprome or levozin or neurocil or norzinan or novo‐meprazine or nozinan or sinogan or tisercin or tisercinetta).ti,ab. 72. (veractil or Pericyazine or neulactil or perphenazine or decentan or peratsin or perdenasin or terfluoperazine or trilafon).ti,ab. 73. (trilafan or triptafen or fentazin or Pimozide or antalon or norofren or orap or pirium or Prochlorperazine).ti,ab. 74. (buccastem or bukatel or chlorperazinum or compazine or cotrazine or emetiral or klometil or mitil or nu‐prochlor).ti,ab. 75. (prochlorperazin or scripto‐metic or stemetil or tementil or trinigrin or ultrazac or ultrazinol or vertigon or Promazine).ti,ab. 76. (prazine or promazin or protactyl or prozyl or sinophenin or sparine or talofen or Thioridazine or aldazine or elperil).ti,ab. 77. (flaracantyl or mallorol or mefurine or meleril or mellaril or melleretten or mellerettes or melleril or orsanil or ridazine).ti,ab. 78. (stalleril or thioridazin or tirodil or visergil or Trifluperazine or discimer or eskazine or foille or iremo or jatroneural).ti,ab. 79. (jatrosom or modalina or oxyperazine or parmodalin or parstelin or sedofren or sporalon or stelabid or stelazine).ti,ab. 80. (stelbid or stelium or stilizan or terfluoperazine or terflurazine or terfluzin or terfluzine or trifluoperazin or trisedyl).ti,ab. 81. (Pipotiazine or lonseren or piportil or piportyl or Zuclopenthixol or ciatyl or cisordinol or clopixol or sordinol).ti,ab. 82. or/49‐81 83. (amantadine or bromocriptine or mazindol or pergolide or dopamine agonist).ti,ab. 84. (amphetamine or d‐amphetamine or dexamphetamine or dextroamphetamine or methamphetamine or Methylphenidate or Modafinil or adrafinil or provigil).ti,ab. 85. (melatonin or N‐ACETYL‐5‐METHOXYTRYPTAMINE or atomoxetine or memanthine).ti,ab. 86. or/83‐85 87. Brain Injuries/ 88. Brain Concussion/ 89. Brain Hemorrhage, Traumatic/ 90. Brain Injury, Chronic/ 91. Diffuse Axonal Injury/ 92. "brain injur*".ti,ab. 93. (TBI or TBIs).ti,ab. 94. ("hypoxic brain damage" or "diffuse axonal injur*" or DAI or DAIs).ti,ab. 95. "head injur*".ti,ab. 96. (brain adj2 trauma*).ti,ab. 97. (head adj2 trauma*).ti,ab. 98. concussion.ti,ab. 99. "brain contusion".ti,ab. 100. 33 or 48 or 82 or 86 101. or/87‐99 102. 100 and 101 103. 11 and 102 |

Dec 2011: 652 Feb 2013: 95 Jan 2014: 36 Dec 2014: 98 |

| 3. EMBASE 1980‐2011 week 45 (Ovid SP) [last searched 30 December 2014] |

1. "traumatic brain injur*".ti,ab. 2. (TBI or TBIs).ti,ab. 3. ("hypoxic brain damage" or "diffuse axonal injur*" or DAI or DAIs).ti,ab. 4. (brain adj2 trauma*).ti,ab. 5. (head adj2 trauma*).ti,ab. 6. concussion.ti,ab. 7. "brain contusion".ti,ab. 8. exp *traumatic brain injury/ 9. or/1‐8 10. randomly.ab. 11. RCT.ti,ab. 12. clinical trial/ 13. randomi?ed.ab. 14. placebo*.ti,ab. 15. groups.ab. 16. "double‐blind*".ti,ab. 17. or/10‐16 18. 9 and 17 |

Dec 2011: 1199 Feb 2013: 367 Jan 2014: 461 Dec 2014: 478 |

| 4. PSYCINFO 1806‐November week 3 2011 (Ovid SP) [last searched 30 December 2014] |

1. traumatic brain injury/ 2. (TBI or TBIs).ti,ab. 3. ("hypoxic brain damage" or "diffuse axonal injur*" or DAI or DAIs).ti,ab. 4. "head injur*".ti,ab. 5. (brain adj2 trauma*).ti,ab. 6. (head adj2 trauma*).ti,ab. 7. concussion.ti,ab. 8. "brain contusion".ti,ab. 9. or/1‐8 10. randomi?ed.ab. 11. placebo*.ti,ab. 12. "double‐blind*".ti,ab. 13. randomly.ab. 14. "single‐blind*".ti,ab. 15. RCT.ti,ab. 16. or/10‐15 17. 9 and 16 |

Dec 2011: 430 Feb 2013: 157 Jan 2014: 84 Dec 2014: 117 |

| 5. CINAHL (EBSCOhost) [last searched 30 December 2014] |

S1 TX "traumatic brain injur*" S2 (MM "Brain Injuries") S3 TX "hypoxic brain damage" OR "diffuse axonal injur*" S4 TX "brain contusion" S5 TX "brain trauma*" S6 TX "head trauma*" S7 TX TBI OR TBIs S8 S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 S9 (MH "Randomized Controlled Trials") S10 TX placebo* S11 TX randomly S12 TX "double‐blind*" OR "single‐blind*" S13 S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 S8 AND S13 |

Dec 2011: 255 Feb 2013: 70 Jan 2014: 46 Dec 2014: 69 |

| 6. Web of Science (1945‐present) (via ISI Web of Science) [last searched 30 December 2014] |

Topic=("traumatic brain injury" OR TBI OR TBIs) AND Topic=(randomly OR randomised OR randomized OR RCT) NOT Title=(mice OR mouse OR rat OR rats OR animal OR model) Timespan=All Years. Databases=SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI‐S, CPCI‐SSH. Lemmatization=On |

Dec 2011: 1395 Feb 2013: 596 Jan 2014: 411 Dec 2014: 233 |

| 7. LILACS (BIREME) [last searched 30 December 2014] |

traumatic brain injury [Words] and random or RCT or randomised OR randomized OR trial OR placebo OR groups [Words] | Dec 2011: 16 Feb 2013: 5 Jan 2014: 0 Dec 2014: 0 |

| 8. CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library) [last searched 30 December 2014] |

#1 MeSH descriptor Brain Injuries explode all trees #2 TBI OR TBIs #3 "hypoxic brain damage" OR "diffuse axonal injur*" #4 "head injur*" #5 brain N/2 trauma* #6 head N/2 trauma* #7 "brain contusion" #8 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7) |

Dec 2011: 963 Feb 2013: 67 Jan 2014: 15 Dec 2014: 57 |

| 9. Clinicaltrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) [last searched 30 December 2014] |

Advanced search: Condition: (Traumatic brain injury OR TBI OR TBIs OR brain contusion OR concussion) AND Intervention studies | Dec 2011: 255 Feb 2013: 64 Jan 2014: 8 Dec 2014: 2 |

| 10. ICTRP Search Portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch) [includes: Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry; ClinicalTrilas.gov; ISRCTN; Chinese Clinical Trial Registry; Clinical Trials Registry – India; Clinical Research Information Service – Republic of Korea; German Clinical Trials Register; Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials; Japan Primary Registries Network; Pan African Clinical Trial Registry; Sri Lanka Clinical Trials Registry; The Netherlands National Trial Register] [last searched 30 December 2014] |

Advanced search: Condition: (Traumatic brain injury OR TBI OR TBIs OR brain contusion OR concussion) | Dec 2011: 364 Feb 2013: 73 Jan 2014: 0 Dec 2014: 2 |

| TOTAL before de‐duplication and assessment based on title and abstract screening | Dec 2011: 5582 Feb 2013: 1503 Jan 2014: 1062 Dec 2014: 1053 TOTAL: 9200 |

|

| TOTAL after de‐duplication and assessment based on title and abstract screening | Dec 2011: 438 Feb 2013: 142 Jan 2014: 71 Dec 2014: 24 TOTAL: 675 |

|

Appendix 2. Glossary of abbreviations of cognitive tests

CANTAB: Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery. Computerised test battery assessing learning, memory, attention, problem solving, executive function and vigilance.

CANTAB‐PAL: Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery Paired Associates Learning.

CANTAB RVIP A': Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery Rapid Visual Information Processing. A subtest measuring sensitivity to a stimulus.

CANTAB RVIP mean latency: Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery Rapid Visual Information Processing. Measure of time to respond to a stimulus.

CANTAB‐RT: Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery Reaction Time.

CANTAB‐SWM: Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery Spatial Working Memory.

CDR: Cognitive Drug Research Computerized Cognitive Assessment System. A computer‐controlled battery of tests including reaction time, spatial memory, numeric memory, word and picture recognition.

CCPT‐II: Conners’ Continuous Performance Test II. Computerised assessment of sustained visual attention.

COWA: Controlled Oral Word Association. Assessment of verbal fluency and word finding.

FAS test: F‐A‐S. A subtest of the Neurosensory Center Comprehensive Examination for Aphasia. Assessment of phonemic word fluency.

HVLT: Hopkins Verbal Learning Test. Verbally administered test assessing verbal learning, verbal memory, long‐term recall, and recognition memory.

ImPACT: Immediate Post Concussion Assessment Cognitive Testing. Computerised battery of cognitive tests that provides scores for verbal memory, visual memory, visual motor speed and reaction time.

SF‐12 physical/mental: Medical Outcome Study 12‐Item Short Form Survey. Measure of health‐related quality of life.

Trail A, B, C & D. Assessment of sequencing, mental flexibility and divided attention.

WAIS‐III‐DS: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale Digit Span. Assessment of short term verbal and auditory memory.

WAIS‐III Digit Symbol Coding: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale Digit Symbol Coding. Assessment of information processing speed.

Appendix 3. Methods for future updates

| Unit of analyses issues |

| In any studies utilising a cross‐over design, only data from the first treatment phase after randomisation will be eligible for inclusion. In the case that numerous eligible studies take repeated observations of outcomes then time frames that reflect short,medium and long term follow‐up will be selected. Time frames will be defined as short term if at six weeks or less, medium term between six and 24 weeks, while long term studies will run for six months or more. If repeated observations are not a significant issue then the longest follow‐up will be selected for each study. |

| Assessment of heterogeneity |

| Heterogeneity to be tested using a standard Chi2 statistic with a P = 0.1 being considered significant and quantified using the I2 statistic. If there is evidence of heterogeneity of the treatment effect between trials then a random‐effects model will be used. If heterogeneity is too great (that is I2 > 75%) then meta‐analysis will not be possible. |

| Assessment of reporting biases |

| To minimize the potential for publication bias, study authors, pharmaceutical companies and experts will be contacted to assist in the identification of unpublished studies. Furthermore, authors of identified studies will be contacted to enquire about duplication of studies and outcome reporting bias. Unpublished studies will be included in the meta‐analysis and the methodology and potential

for bias assessed using the same criteria as outlined above (see: ’Assessment of risk of bias in included studies’). The intervention effect estimates from each study will be plotted against a measure of each study’s size or precision to create a funnel plot. If enough studies are identified (usually > 10) then the asymmetry can be assessed statistically (Begg and Mazumdar 1994), otherwise the funnel plot will be cautiously interpreted with the limitations of this method explicitly stated in the discussion. |

| Data synthesis |

| The review authors expect the studies to employ a wide range of tools assessing the same cognitive function and so meta‐analysis will utilize the standardised mean difference approach, standardising

the mean differences to a single scale. Differences in the direction of scales measuring the same outcome will be dealt with by multiplying by −1 to ensure all scales point are in the same direction. As usual, a study’s weight will be calculated using the standard deviation and sample size. A summary (pooled) intervention effect estimate will then be calculated as a weighted average of the intervention effects estimated in the individual studies, as described in the Cochrane Handbook, section 9.4.2. Depending upon whether heterogeneity of results is identified, we will decide whether a fixed‐effect or a random‐effects model is used for meta‐analysis. In either case the inverse variance method will be used. The duration of the trials may vary considerably. If the range is considered too great to combine all trials into one meta‐analysis the data can be divided into smaller time frames and a separate meta analysis conducted for each period. Some trials may contribute data to more than one time period if multiple assessments have been made. Pharmacotherapeutic interventions will be combined depending on the general class of drug (for example antidepressants). Subsequent subgroup analyses will focus on the neurotransmitter systems affected by the intervention (for example serotonergic). Some pharmacotherapies may be included in more than one analysis if they are known to significantly affect multiple neurotransmitter systems. For example, duloxetine would be included in the serotonergic and adrenergic analyses. Standard texts on psychopharmacology and manufacturers’ information will be consulted to establish the pharmacodynamic properties of each agent. The formation of subgroups will be conducted once the search has been performed but before the outcomes have been extracted. |

| Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity |

| If statistical heterogeneity is identified then we will adopt the strategies recommended in the Cochrane Handbook, section 9.5.3. We will evaluate possible reasons for the heterogeneity by assessing subgroups of trials: (i) difference in quality of trial, and (ii) severity of TBI.We will compare outcomes in those with mild TBI against those who suffered moderate to severe injury. Mild should be defined as Glasgow coma scale (GCS) greater than or equal to 13 with no penetrating injury. |

| Sensitivity analysis |

| Issues suitable for sensitivity analysis will be identified during the review process. If a particular decision appears to affect the findings then we will attempt to understand this and perhaps gain further information from the authors of the original studies. Sensitivity analyses will be presented in table format and will inform the interpretation of the review’s findings. |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Modafinil vs placebo (4 weeks).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 SF‐12 Physical | 1 | 51 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.18 [‐6.34, 1.98] |

| 2 SF‐12 Mental | 1 | 51 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.95 [‐2.84, 6.74] |

| 3 ImPACT verbal memory composite | 1 | 51 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.42 [‐4.42, 7.26] |

| 4 ImPACT visual memory composite | 1 | 51 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [‐6.52, 7.02] |

| 5 ImPACT visual motor speed composite | 1 | 51 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐3.45 [‐6.48, ‐0.42] |

| 6 ImPACT reaction time composite | 1 | 51 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.02 [‐0.04, 0.08] |

| 7 CCPT‐II No. of omissions | 1 | 51 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 16.57 [‐3.59, 36.73] |