Abstract

Long-term survivors (LTS) of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection provide an opportunity to investigate both viral and host factors that influence the rate of disease progression. We have identified three HIV-1-infected individuals in Australia who have been infected for over 11 years with viruses that contain deletions in the nef and nef-long terminal repeat (nef/LTR) overlap regions. These viruses differ from each other and from other nef-defective strains of HIV-1 previously identified in Australia. One individual, LTS 3, is infected with a virus containing a nef gene with a deletion of 29 bp from the nef/LTR overlap region, resulting in a truncated Nef open reading frame. In addition to the Nef defect, only viruses containing truncated Vif open reading frames of 37 or 69 amino acids could be detected in peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from this patient. LTS 3 had a viral load of less than 20 copies of RNA/ml of plasma. The other two long-term survivors, LTS 9 and LTS 11, had loads of less than 200 copies of RNA/ml of plasma and are infected with viruses with larger deletions in both the nef alone and nef/LTR overlap regions. These viruses contain wild-type vif, vpu, and vpr accessory genes. All three strains of virus had envelope sequences characteristic of macrophagetropic viruses. These findings further indicate the reduced pathogenic potential of nef-defective viruses.

A small percentage (<5%) of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected individuals remain free from AIDS-defining illnesses for longer than 10 years in the absence of therapy (4). Individuals in this group maintaining CD4-positive lymphocyte counts greater than 500 cells/μl without receiving therapy are known as long-term nonprogressors (LTNP). The factors involved in the long-term survival of these patients have been the subject of intense investigations as they may provide information important to the development of HIV-1 vaccines and treatments.

Several factors associated with delayed or slow progression have been identified and include coreceptor (CCR5 and CCR2b) genotype (6, 30), HLA alleles (25), and, in a few individuals, virus genotype. Several defects in the viral genome of HIV-1 strains infecting long-term survivors (LTS) have been reported. These include rev gene mutations (14), mutations in vif, vpr, vpu, and nef genes (22, 23) and deletions in the nef-long terminal repeat (nef/LTR) region of HIV-1 strains (6, 16, 27; R. Geffin, D. Wolf, R. Muller, M. Hill, E. Stellwag, G. Scott, and A. Baur, Keystone Symp. HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment 1998, abstr. 3027, 1998), and deletions in the nef/LTR region have also been reported for HIV-2 (32).

The largest study of LTS infected with a defective HIV-1 strain has been the Sydney Blood Bank Cohort (SBBC) identified in Australia (5, 19, 20, 21, 24). This cohort consists of eight individuals who became infected with a common nef-defective strain of virus after being transfused with blood products from a common donor. After more than 16 years of infection, three of the living cohort members have stable CD4 cell counts and undetectable viral loads (<20 RNA copies/ml of blood), and three, including the donor, have declining CD4 cell counts and viral loads of 1,000 to 10,000 copies/ml (21). Most recently, the donor was diagnosed with AIDS and has commenced highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) (21), and one recipient has also been treated because of declining CD4-positive lymphocyte counts.

There have been two other reports on the sequence structure of nef-defective HIV-1 strains. One study identified a hemophiliac whose virus had deletions in the nef/LTR region (16) that increased in size over time. The other patient acquired HIV-1 infection through sexual intercourse (27) and was infected with a virus containing deletions in nef alone and LTR regions, although wild-type LTR sequences were also present in this patient. These individuals both had undetectable viral loads. The hemophiliac had no reported AIDS-related infections and was reported to have a decline in CD4-positive cell numbers despite low viral loads that was reversed by HAART in 1998 (12). These observations, taken with those from the SBBC, suggest that infection with nef-defective viruses can lead to immune deficiency even when viral loads in the plasma are low to undetectable (less than 200 copies of RNA/ml). However, it is also apparent that individuals infected with these strains have a significantly longer survival time than patients infected with wild-type strains of HIV-1.

In an analysis of viral and host factors associated with long-term nonprogression, 70 persons enrolled in the Australian LTNP study (2) were screened for nef/LTR deletions, mutations in the vif, vpr, and vpu accessory genes, and virus tropism based on env V3 loop sequence. Three LTS infected with HIV-1 strains with different nef/LTR deletions were detected. These three had envelope sequences characteristic of macrophagetropic viruses, and one had point mutations in the vif and vpr genes leading to truncated open reading frames (ORFs).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study group and sample preparation.

The LTS studied in this group were enrolled in the Australian Long-Term Nonprogressor Study (2). All had documented evidence of asymptomatic HIV-1 infection for at least 8 years, with a history of CD4-positive lymphocyte counts of ≥500 cells/μl and no antiretroviral therapy. On recruitment to the study, blood samples were collected and tested for serological reactivity to HIV-1 proteins. All participants tested positive (2). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from these venous blood samples using density gradient centrifugation on Ficoll-Hypaque. Washed PBMCs were resuspended and lysed at a concentration of 5 × 106 to 10 × 106 cells/ml in PCR lysis buffer (24). Viral loads were measured using the Amplicor HIV-1 monitor assay (Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburgh, N.J.).

Amplification of nef/LTR.

Proviral sequences were amplified using Taq DNA polymerase (Roche Diagnostics) and a sensitive triple-nested PCR protocol. The first round used the primers Nef5′5′ (equivalent to nucleotides [nt] 8552 to 8573 of HIV-1NL4-3) and CL6 at a final concentration of 400 nM, the second round used primers Hpa5′ (equivalent to nt 8637 to 8659) and LTR3′ at 200 nM, and the third round combination was Nef5′ and LTR3′, also used at 200 nM. The sequences and coordinates of primers CL6, Nef5′, and LTR3′ have been reported previously (5). The cycling conditions for the primer sets were 94°C for 120 s, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 55°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 80 s, and a final elongation step of 72°C for 7 min. The cycling conditions for the second- and third-round primers were the same as for the first except the elongation time for the 35 cycles was 60 s at 72°C.

Deletion primers.

Primers were made to HIV-1NL4-3 sequences in the deleted region of the nef/LTR of LTS 3 (nt 9117 to 9138), LTS 9 (nt 9290 to 9311), and LTS 11 (nt 9242 to 9261) and were used in place of LTR3′ in the triple-nested PCR amplification.

Amplification of the envelope V3 region.

The V3 loop was amplified using a nested PCR protocol and primers DR16 (nt 6515 to 6539 of HIV-1NL4-3) and M13R12 (5′-M13R-+, nt 8007 to 8028), DR16 and DR19 (nt 7691 to 7714), and a final round with M13F11 (5′-M13F-+, nt 6532 to 6556) with DR19. M13R refers to the addition of the M13 reverse universal primer sequence (5′-TGCGGATAACAATTTCACACAGG-3′) to the 5′ end of the HIV-1-specific primer sequence. Similarly, M13F refers to the addition of the M13 forward universal primer sequence (5′-TGCCACGACGTTGTAAAACGAC-3′) to the 5′ end of the primer. The primer concentrations and cycling conditions were as described for the nef/LTR region.

Accessory gene amplification.

The region of the HIV-1 genome containing the accessory genes vif, vpr, and vpu (equivalent to nt 4945 to 6372 of HIV-1NL4-3) was amplified using a triple-nested protocol consisting of a first round with primers V1F (nt 4651 to 4672) and V1R (nt 6517 to 6542), a second with primers V2F (nt 4820 to 4843) and V2R (nt 6456 to 6479), and a final round with primers V3F (nt 4945 to 4969) and V3R (nt 6347 to 6372). All coordinates are given relative to HIV-1NL4-3. Primer concentrations and conditions for amplification were essentially those for the nef/LTR region except that Expand High Fidelity polymerase mix (Roche Diagnostics) was used in place of Taq polymerase together with an extension time of 2 min at 72°C.

Sequencing.

Either amplimers were blunt ended, cloned, and sequenced or uncloned products were sequenced following amplification with primers containing M13 forward or M13 reverse tails as described previously (24). Sequences were aligned and analyzed using GeneWorks software (Oxford Molecular Group).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nef/LTR, vif, vpr, vpu, and env sequences described in this study have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AY005982 to AY006090.

RESULTS

Identification of three LTS with deleted nef/LTR regions.

Seventy HIV-1-infected LTS were recruited as part of a study on Australian long-term nonprogressors. Of the 70, 59 participants had viral loads of greater than 200 RNA copies/ml of plasma, and 11 had viral loads of less than 200 RNA copies/ml of plasma. From a single attempt to amplify the nef/LTR region using triple-nested PCR, 54 of the 59 participants with viral loads of greater than 200 copies/ml of plasma yielded a positive nef/LTR amplimer, all of which were wild type in size. Thirty of these were chosen at random to represent viruses from participants with a viral load spread from >200 to over 10,000 RNA copies/ml of plasma. These PCR amplimers were cloned and sequenced, all yielding wild-type Nef ORF (L. J. Ashton, D. I. Rhodes, A. Solomon, L. Deacon, C. Satchell, A. Carr, D. Cooper, R. Biti, G. Stewart, and J. M. Kalder, submitted for publication). The nef/LTR region was successfully amplified, often requiring more than one attempt, from all remaining 11 LTS with viral loads of less than 200 RNA copies/ml. Of these, three, LTS 3, 9, and 11, yielded only nef/LTR PCR amplimers smaller than wild-type HIV-1. LTS 3 had a viral load of less than 20 copies RNA/ml of plasma using the ultrasensitive Amplicor HIV-1 assay, and amplification of the nef/LTR and accessory gene regions from this individual was by far the most difficult. To amplify required a product from LTS 3 required at the very least twice as many PCR attempts as were required from the other LTS, even compared to three other LTS in the group with viral loads of <60 copies RNA/ml of plasma. The other two LTS, LTS 9 and LTS 11, with deletions in the nef/LTR region had viral loads of <200 copies RNA/ml of plasma using the standard Amplicor assay. Epidemiological studies indicated that these three LTS acquired HIV-1 through sexual contact with different people (2).

Amplification of the nef/LTR region from LTS 3 PBMCs was successful in only 3 of 13 PCR attempts (once from a sample collected in December 1995 and twice from a sample collected in September 1998), indicating that the number of provirus copies was very low. Amplimers from both samples were 847 bp in length, 35 bp smaller than the wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 nef/LTR of 882 bp. This individual first tested positive for HIV-1 in February 1985, had a CD4+ cell count of 882 cells/μl, is homozygous for the wild-type CCR5 allele, and is heterozygous for the CCR2b-64I allele (Table 1) (Ashton et al., submitted).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of nef-defective LTS with undetectable levels of HIV-1 RNA in plasma

| LTS | HIV-1 RNA (copies/ml of plasma) | Time of first HIV test | CD4+ cells/μl | Chemokine genotypea

|

Size(s) of nef/LTR (bp)b | Nef ORF (amino acids)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCR5 | CCR2b | ||||||

| 3 | <20 | February 1985 | 1,375 | wt/wt | wt/64I | 847 | 110 |

| 9 | <200 | April 1988 | 860 | wt/wt | wt/wt | 435/610/796 | 4/82d |

| 11 | <200 | June 1985 | 1,431 | wt/Δ32 | wt/wt | 591/776 | 56 |

wt, wild type.

Wild-type nef/LTR is 882 bp.

Wild-type Nef ORF has 206 amino acids.

Of the 82 amino acids, 62 were amino acids of Nef sequence, with amino acids 30 to 41 inclusive, relative to HIV-1NL4-3, being absent.

Amplification of the nef/LTR from LTS 9 gave three different products, 435, 610, and 796 bp (Fig. 1). The larger sequences of 796 and 610 bp were amplified from a sample collected in October 1996, whereas the smaller 435-bp sequence, together with the 796-bp and 610-bp sequences, was amplified from a sample collected 17 months later (March 1998). No 435-bp nef/LTR sequence could be amplified from the October 1996 sample even after five independent PCR attempts. This individual first tested positive in April 1988 and has a viral load of less than 200 copies/ml, a CD4+ cell count of 860 cells/μl, and wild-type CCR5 and CCR2b alleles (Table 1).

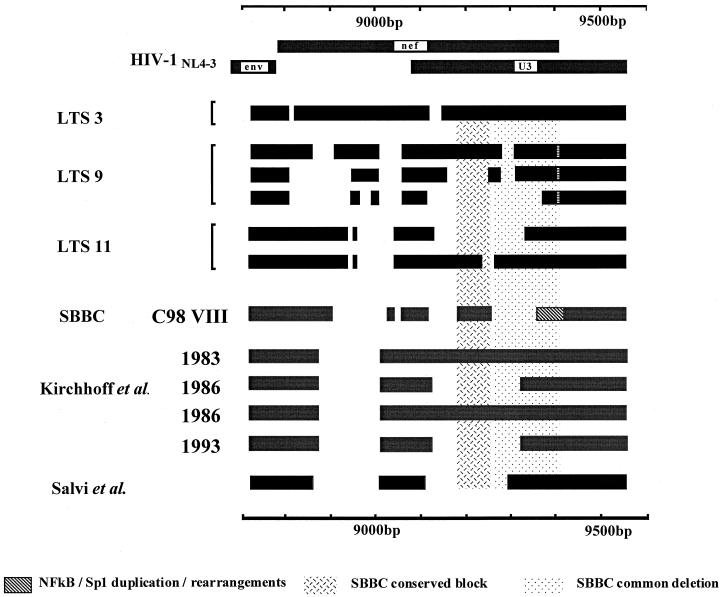

FIG. 1.

Deletions in the nef/LTR region in viral sequences amplified from LTS 3, 9, and 11 compared with other nef-defective viruses. Blocks represent nucleotide sequence, and gaps represent deletions. The hashed region in U3 in LTS 9 represents the TCF-1α duplication. The speckled block represents the SBBC common deletion, and the hashed block represents sequence conserved in the SBBC strains. Other LTS sequences were from Kirchhoff et al. (16) and Salvi et al. (27). The SBBC C98VIII sequence is from Rhodes et al. (abstr., 1999). The sequences for LTS 3, 9, and 11 have been deposited in GenBank with accession numbers AY006061 to AY006063, AY006064 to AY006075, and AY005982 to AY005990, respectively.

Amplification of the nef/LTR region from LTS 11 consistently gave two sizes of nef/LTR amplimers, 591 and 776 bp, from a sample collected in September 1997. Similar-sized products were also amplified from a sample collected in April 1998. This individual first tested positive for HIV-1 in June 1985, has a viral load of less than 200 copies/ml and CD4+ cell counts of 1,431 cells/μl, and is heterozygous for the CCR5Δ32 allele (31) (Table 1).

Sequence analysis of nef/LTR regions from LTS 3, 9, and 11.

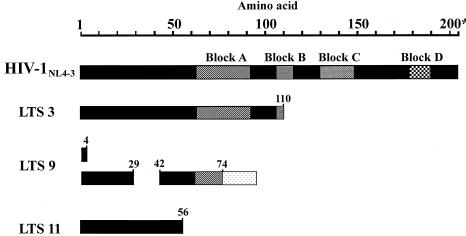

Sequencing of both cloned and uncloned nef/LTR products (24) amplified from LTS 3 (December 1995 and September 1998 samples) revealed an in-frame deletion of 6 bp from the 5′ end of the nef gene, beginning at nt 8815 relative to HIV-1NL4-3. This corresponds to the loss of two amino acids, equivalent to amino acids 10 and 11 of HIV-1NL4-3 Nef, from an area of known sequence polymorphism (29). A further 29 bp of sequence was also deleted from the U3 region beginning at nt 9113 (Fig. 1). The remaining sequence is like that of wild-type strains, retaining regions essential for viral replication and, unlike the SBBC strains, contains no alterations in the enhancer and basal promoter regions (NF-κB and Sp1 binding regions, nt 9425 to 9484 of HIV-1NL4-3). Amplification of the nef/LTR region from the September 1998 sample using an Expand High Fidelity polymerase mix yielded an identical nef/LTR product. The 29-bp deletion resulted in a change in reading frame, yielding a truncated Nef ORF of 110 amino acids, compared with 206 amino acids for Nef of HIV-1NL4-3, and 4 additional non-Nef amino acids before an in-phase termination codon. Of the four conserved amino acid blocks of Nef (defined by Shugars et al. [29]), the encoded 110-amino-acid protein of LTS 3 contains conserved block A and half of block B but lacks blocks C and D (Fig. 2) and therefore is unlikely to be fully functional. The expression of this Nef protein has not been determined.

FIG. 2.

Predicted Nef ORFs of the three defective LTS viruses lack the majority of the conserved Nef blocks. Blocks A, B, C, and D represent conserved Nef amino acid sequence structures (29). Non-Nef amino acids in LTS 9 are represented as a stippled box. Numbering represents amino acids.

Sequencing of the 435-, 610-, and 796-bp nef/LTR amplimers obtained from LTS 9 showed deletions occurring in similar positions in the three nef/LTR populations, but the sizes of the deletions varied (Fig. 1). All clones shared an identical 47-bp deletion between nt 9008 and 9056 relative to the wild type, and all lacked sequence between nt 8868 and 8904 and nt 9287 and 9307. All sequences possessed wild-type enhancer and basal promoter regions and a duplication of 16 bp in the putative TCF-1α/RBF-2 binding region immediately 5′ of NF-κB site II (Fig. 1). This duplication is known as the most frequent naturally occurring HIV-1 length polymorphism (9).

Translation of the largest sequence, 796 bp, gave a Nef ORF encoding to amino acid 74, although it lacks 12 amino acids, from positions 30 to 41 inclusive relative to HIV-1NL4-3. After amino acid 74, the reading frame changes, encoding a further 20 non-Nef amino acids before a premature stop codon. The putative Nef protein contains only half of conserved block A and does not contain the other three conserved blocks (Fig. 2). Translation of the smaller sequences, 610 and 435 bp, gives a Nef ORF of only 4 amino acids before an in-phase termination codon (Fig. 2).

The sequences of the 591- and 776-bp nef/LTR products from LTS 11 both lacked 79 nt from the nef-alone region between nt 8961 and 9039 relative to the HIV-1NL4-3 sequence. This deletion removes sequence coding for the Pxx repeat of Nef (29) and results in a Nef ORF of only 56 amino acids due to the introduction of a termination codon after the first deletion. The Nef ORF does not encode any of the conserved Nef blocks (Fig. 2). The deletions in the nef/LTR overlap region differ in size between these two populations (Fig. 1). The majority of clones lacked the negative regulatory element region (nt 9188 to 9343), although 3 of the 10 clones sequenced lacked only 18 bp (nt 9240 to 9257) from this region.

Absence of full-length nef/LTR sequences in LTS 3, 9, and 11.

To determine whether wild-type nef/LTR sequences were also present in LTS 3, 9, and 11, primers were made to HIV-1NL4-3 sequences in the deleted regions and used in conjunction with Nef5′ in a triple-nested PCR amplification. In addition to reamplification from PBMCs, second-round PCRs that yielded the deleted nef/LTR fragments were also amplified with the appropriate deletion primers. In no instance did products result from the use of the deletion primers on samples from the three LTS. Amplification of control HIV-1NL4-3 PBMC lysates gave expected amplimers of 460, 633, and 583 bp for deletion primers LTS 3, 9, and 11, respectively, at a sensitivity of 1 copy per 100,000 cells. Taken together with the absence of any full-length nef/LTR products from other PCR amplifications, these results indicate that full-length nef/LTR sequences are not present in PBMCs from these LTS.

Envelope V3 sequences indicate that viruses are macrophagetropic.

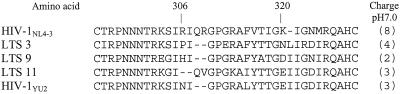

Several attempts to culture virus from PBMCs from the three LTS were unsuccessful even when CD8 cell depletion coculture techniques were used (2). To determine the tropism of these viruses, the V3 loop region of the envelope gene was amplified and sequenced. The resulting sequences from LTS 3, 9, and 11 were translated, giving peptides with overall charges of positive 4, 2, and 3, respectively, at pH 7. No sequences had positively charged amino acids at both the 306 and 320 amino acid positions, and as the V3 loop is acidic (Fig. 3), the viruses are likely to be macrophagetropic (7, 10). The amino acid sequence GPER present at the tip of the V3 loop in LTS 3 is unusual and has been reported only once (18).

FIG. 3.

env V3 loop sequences of LTS 3, 9, and 11 viruses compared with the T-cell-tropic virus HIV-1NL4-3 and the macrophagetropic HIV-1YU2. The sequences of LTS 3, 9, and 11 are representative of macrophagetropic viruses. The overall charge of the V3 loop at pH 7 is given for each sequence. Numbering of amino acids is relative to the HIV-1NL4-3 Env sequence.

Accessory gene sequences from LTS 3 encode only truncated Vif.

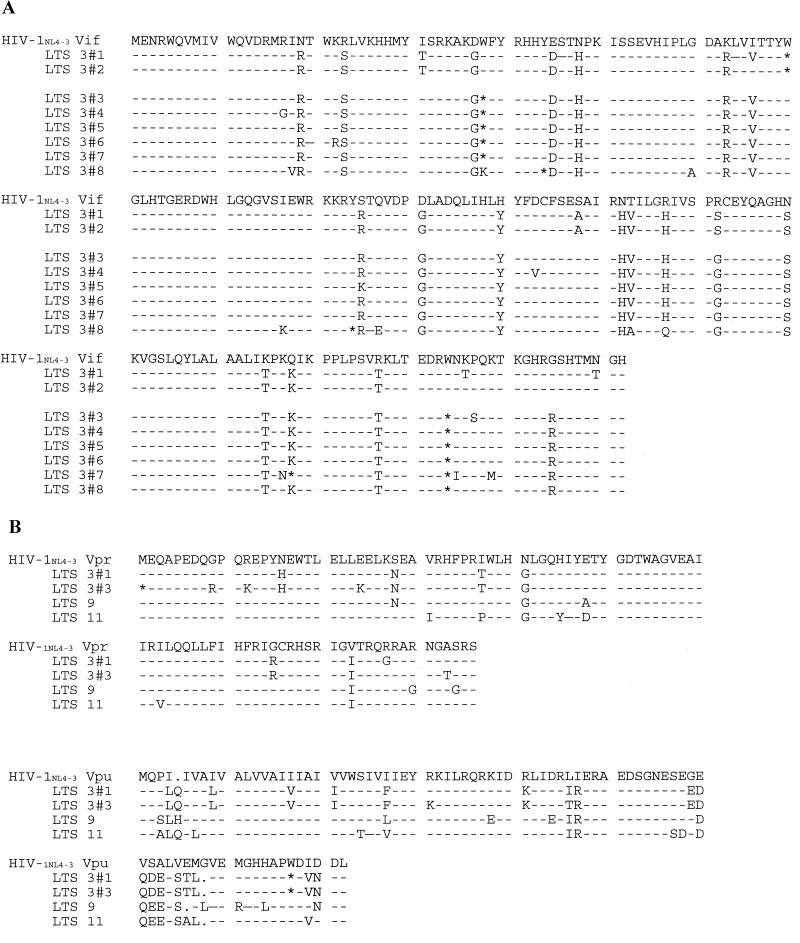

To ascertain whether there are defects in other HIV-1 genes which might contribute to the viral loads of <200 RNA copies/ml of plasma in the 11 individuals, we amplified and sequenced their proviral vif, vpr, and vpu genes and the first coding exons of the tat and rev gene regions. Of the 11 screened, only clones from LTS 3 possessed only truncated Vif ORFs. As encountered with the amplification of the nef/LTR region from LTS 3, amplification of the accessory gene region was also the most difficult of all LTS studied. Of 11 attempts to amplify the accessory gene region from the LTS 3 December 1995 sample, only 1 was successful, and of eight independent PCR attempts on the LTS 3 September 1998 sample, two were successful. These were all cloned and sequenced (Fig. 4A). Typically for other LTS with viral loads of <200 RNA copies/ml of plasma, only one or two PCR attempts were necessary to yield the desired product. Analysis of amplimers from LTS 9 and 11 also had several novel single amino acid differences from those reported previously (1, 18) and are described in more detail below.

FIG. 4.

Alignments of accessory protein sequences from LTS. (A) Representative Vif amino acid sequences from LTS 3 clones compared with HIV-1NL4-3. Dashes indicate identical amino acids, and differences from HIV-1NL4-3 are indicated by the single-letter amino acid code. The asterisks (∗) denote the positions of premature termination codons. Clones 1 and 2 were amplified from a sample collected in December 1995, and clones 3 through 8 were amplified from a sample collected in September 1998. (B) Representative Vpr and Vpu sequences from LTS 3, 9, and 11 compared with HIV-1NL4-3. Dashes indicate identical amino acids, and differences from HIV-1NL4-3 are indicated by the single-letter amino acid code. The asterisks (∗) denote the positions of premature termination codons, and dots represent gaps in the sequence alignment. Clones LTS 3#1 and LTS 3#3 are representative clones from the December 1995 and September 1998 samples, respectively. (GenBank accession numbers AY005982 to AY006090).

Sequence analysis of the accessory genes from LTS 3 showed wild-type length sequences for vif, vpr, and vpu and the first coding exons of tat and rev. However, translation of the vif gene sequence from 12 clones and the uncloned products from the December 1995 sample gave a truncated Vif ORF of only 69 amino acids, compared with 192 for Vif of HIV-1NL4-3 (Fig. 4A). The sequences of eight of the clones and the uncloned material are represented by that shown as LTS 3#1. The sequence of the remaining 4 of the 12 clones is represented as LTS 3#2. The accessory genes from a more recent sample (September 1998) were also amplified and sequenced. Of 20 vif clones and the uncloned product sequenced, 19 encoded a Vif ORF of only 37 amino acids (Fig. 4A). The truncated ORFs were due to the presence of a premature stop codon as a result of a G-to-A mutation in the tryptophan codons at amino acids 70 and 38 for the earlier and later samples, respectively. The reading frame in all clones encoding the 69-amino-acid Vif remained open after the stop codons to the end of the wild-type Vif ORF. Clones encoding the 37-amino-acid Vif ORF also had a stop codon at position 174; however, none had a stop codon at position 70. Half of the full-length vif clones sequenced had a sequence represented by LTS 3#3. Another two clones also had an additional stop codon at position 158 (Fig. 4A). In addition, 1 of the 20 clones examined from the September 1998 sample was found to encode a Vif ORF of 43 amino acids, and this clone also contained stop codons at positions 94 and 174 (Fig. 4A). No clones with a Vif ORF of 37 amino acids could be recovered from the December 1995 sample that gave the ORF of 69 amino acids. Several sequence variations from HIV-1NL4-3 were observed that have been identified in other LTS sequences (1, 23, 35).

A full-length Vpr protein was encoded by five clones examined and the uncloned fragments amplified from the December 1995 sample (Fig. 4B). However, of 20 clones examined in this region from the September 1998 sample, none possessed the ATG start codon for the Vpr ORF. This codon overlaps the premature stop codon at amino acid 174 of Vif and in Vpr has become an ATA codon.

Apart from one amino acid variation, N16H, which was present in all Vpr ORFs amplified from the December 1995 sample (LTS 3#1, Fig. 4B) and present in the sequences amplified from the September 1998 sample (LTS 3#3, Fig. 4B), the other variations from HIV-1NL4-3 Vpr have been observed previously. These were not suggested to affect Vpr function (23, 33, 35). The N16H variation occurs in the nuclear localization region; however, whether it has any effect on Vpr function is not known.

The Vpu ORF of LTS 3 is 75 amino acids, lacking 6 amino acids from the carboxyl terminus compared to HIV-1NL4-3 (Fig. 4B). An identical truncation has been reported previously in an LTNP sequence (35), although in that study by Zhang et al. (35), it represented only one of seven clones. The effect of this truncation on Vpu function is not known. The first coding exons of rev and tat were intact in all clones.

LTS 9 and 11 contain full-length accessory genes.

The accessory gene region amplified from LTS 9 yielded a full-length Vif ORF of 192 amino acids in two of five clones. A third had an ORF of 173 amino acids. The two clones encoding full-length Vif ORF also contained full-length ORFs for Vpr (96 amino acids) and Vpu (81 amino acids) (Fig. 4B). The other three clones gave a Vpr ORF of 17 amino acids and a Vpu ORF of 22 amino acids. Of the clones with full-length ORFs, several unreported amino acid variations were observed, Vif-encoded amino acid variation H183R and Vpr-encoded variation E48A (Fig. 4B). The effect of these variations on the function of the accessory proteins is unknown. All clones gave intact first coding exons for rev and tat.

Sequences from the accessory gene region from LTS 11 yielded full-length ORFs for the vif, vpr, and vpu genes and the first exons of rev and tat. Several amino acid variations from the HIV-1NL4-3 sequence were observed, and those previously unreported were, in Vif K63I, H73N and conservative amino acid changes in Vpr(V31I) and in Vpu(I26V) (Fig. 4B). It is not known whether these variations have an effect on the function of the proteins.

DISCUSSION

Of the almost 5% of HIV-1-positive individuals who are LTS, our study shows that approximately 4% (3 of 70) of the individuals in the Australian LTNP cohort are infected with viruses containing nef-defective genomes. These represent 3 of 11 individuals in the study who had viral loads of <200 copies of RNA/ml.

The three new nef-defective HIV-1 strains identified in this study differ in sequence structure from the transfusion-transmitted SBBC strains of virus previously identified in Australia (5) in two significant respects. First, the LTS identified in the present study contain nucleotide sequence in a region (nt 9281 to 9438) deleted in all SBBC strains, and second, they lack the duplications and rearrangements in the NF-κB and Sp1 transcription factor binding domains characteristic of SBBC strains. Second, the majority of clones (7 of 10) from LTS 11 and three of nine clones from LTS 9 lack a purine-rich sequence block, reported to be an NF-AT binding region (28), that is conserved in all SBBC strains (Fig. 1). The possible index partner of LTS 9 appears to be infected with a wild-type strain of HIV-1 (D. Rhodes, unpublished data). The deletions observed in the three LTS viruses described here also differ from each other and from those of other nef-deleted HIV-1 strains reported elsewhere (16, 27), indicating that in general, regions not essential for replication are equally susceptible to deletion. Sequence differences in the auxiliary genes, env V3 loop, and nef/LTR regions as well as differences in the number and location of nef/LTR deletions indicate that these strains of HIV-1 are unrelated.

The strains identified in this study retain all the basic elements of the nef/LTR region required for replication, namely, the polypurine tract, the start of the U3 region, and the enhancer and basal promoter regions. The strain found in LTS 3 is unique among nef-defective strains, as no provirus with full-length nef/LTR or Vif ORF could be found in any of the samples analyzed. These results suggest the presence of a strain defective in both nef and vif. The difficulty in amplifying viral sequences, the undetectable viral loads (<20 copies of RNA/ml of plasma), and the inability to culture virus from this individual make it difficult to prove conclusively that these defects occur together in the same virus genome. However, these properties are consistent with the replication of primate lentiviruses that contain multiple accessory gene defects (8). During the amplification procedure, a proofreading polymerase was used to negate PCR error as a factor in the detection of truncated Vif ORFs. Intrasample sequence variation was also observed among clones from LTS 3, indicating that more than one truncated Vif template molecule was amplified. Unexpectedly, no clones containing stop codons at both amino acids 37 and 68 were found. However, these different-length ORFs were amplified from samples collected at different times; the 37-amino-acid ORF was present in the more recent sample, whereas only the 68-amino-acid ORF was detected in the earlier sample. Clones from this sample also had an additional stop codon at amino acid 174, and therefore the production of a full-length Vif protein would require more than one reversion. The presence of the mutation at 174 also abolishes the wild-type start codon for Vpr, and no Vpr clones that had a start codon were found in the more recent (September 1998) sample. Mutations in Vpr have previously been shown to be associated with long-term nonprogression (23, 33). Further attempts are being undertaken to determine whether full-length Vif ORFs are or ever were present in this LTS by testing for antibodies to different peptides from Vif using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technique similar to that described for Nef (13).

It is also somewhat surprising that the small nef/LTR deletion seen in LTS 3 persisted, as it has been reported that small deletions, albeit an in-frame 12-bp deletion, in the nef gene of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) was readily repaired to wild-type Nef sequences with loss of attenuation of the virus (34). Together with the defects in the nef gene, the defects in vif of LTS 3 would be expected to contribute significantly to the low viral loads (less than 20 copies/ml) and the inability to isolate virus from this individual, as Vif-defective HIV-1 very poorly infects PBMCs (11). Further evidence to suggest the presence of a highly attenuated virus is the absence of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte effector cell responses in this individual (E. Keoshkenan, L. J. Ashton, D. G. Smith, J. B. Ziegler, G. J. Stewart, J. M. Kaldor, D. A. Cooper, and R. Ffrench, submitted for publication). In addition, with this reduced replication capacity the repair of the small nef/LTR deletion and the truncated Vif ORF would be less likely to occur.

The size of the defective nef/LTR amplified from LTS 9 appears to be decreasing over time, suggesting an evolution of the defective nef/LTR sequences. Studies by us and others (16; D. Rhodes, A. Solomon, D. McPhee, and N. Deacon, Abstr. XIth Int. Cong. Virol. 1999, abstr. VW23.06) have demonstrated the evolution of nef-defective HIV-1 strains by additional deletions in this region. Similar evolution of the nef/LTR region has also been observed in nef-defective SIV strains in macaques that progress to AIDS (3, 17). The results from our studies with the SBBC strain of HIV-1 (Rhodes et al., abstr. 1999) indicate that the smaller viruses have a replication advantage over the larger ones, highlighting the importance of monitoring viral loads and viral quasispecies in LTS containing nef-defective viruses. In addition to the defective nef genes in LTS 9, all clones were found to encode Vpr with an unusual E48A difference compared with HIV-1NL4-3. The effect of this nonconservative amino acid difference on Vpr structure and function remains to be investigated.

Sequences from LTS 11 showed a nef-defective virus strain that maintains a Nef ORF of 56 amino acids, although presumably it is not fully functional due to the absence of conserved Nef regions. This strain also encodes a Vif protein with a previously unreported difference from other sequences, the nonconservative K63I substitution. Whether this has any effect on the structure and function of Vif is not known, and therefore any contribution of this difference to the low viral load remains to be determined. In addition to the contribution of a nef-defective virus to long-term nonprogression, LTS 11 is heterozygous for the CCR5Δ32 allele.

In all three LTS strains, defects are present in the LTR gene promoter region. Studies in this laboratory on the SBBC viruses (5) have demonstrated that deletions in the LTR region can alter a virus's ability to replicate (Rhodes et al., abstr.; unpublished data). It is likely, therefore, that these mutations, although somewhat different between strains, together with the nef deletions and the unusual variations observed in the accessory proteins, also contribute to the low viral loads and lack of progression in these LTS.

This study has also identified what appears to be a unique nef- and vif-defective strain of virus. If this virus is found to replicate productively, albeit at a much reduced level, it would provide valuable information regarding the pathogenicity in humans of HIV-1 defective in multiple genes. It is doubtful this strain would make a useful live attenuated virus vaccine candidate, as the level of protection is inversely correlated to the level of attenuation of the virus (15, 26). Studies in the SIV/macaque model using vif-defective SIV strains have failed to induce protective immune responses (15). Follow-up studies on these individuals will provide additional information regarding the contribution of nef to HIV-1 pathogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all of the study participants.

This work was supported by grants to the National Centre in HIV Virology and the National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research from the Australian National Council on AIDS and Related Diseases through the Commonwealth AIDS Research Grants Committee and the Macfarlane Burnet Centre for Medical Research Fund.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander L, Weiskopf E, Greenough T C, Gaddis N C, Auerbach M R, Malim M H, O'Brien S J, Walker B D, Sullivan J L, Desrosiers R C. Unusual polymorphisms in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 associated with nonprogressive infection. J Virol. 2000;74:4361–4376. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4361-4376.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashton L J, Carr A, Cunningham P H, Roggensack M, McLean K, Law M, Robertson M, Cooper D A, Kaldor J M. Predictors of progression in long-term nonprogressors. Australian Long-Term Nonprogressor Study Group. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1998;14:117–121. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baba T W, Liska V, Khimani A H, Ray N B, Dailey P J, Penninck D, Bronson R, Greene M F, McClure H M, Martin L N, Ruprecht R M. Live attenuated, multiply deleted simian immunodeficiency virus causes AIDS in infant and adult macaques. Nat Med. 1999;5:194–203. doi: 10.1038/5557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchbinder S P, Katz M H, Hessol N A, O'Malley P M, Homberg S D. Long-term HIV-1 infection without immunologic progression. AIDS. 1994;8:1123–1128. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199408000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deacon N J, Tsykin A, Solomon A, Smith K, Ludford-Menting M, Hooker D J, McPhee D A, Greenway A L, Ellet A, Chatfield C, Lawson V A, Crowe S, Maerz A, Sonza S, Learmont J, Sullivan J S, Cunningham A, Dwyer D, Dowton D, Mills J. Genomic structure of an attenuated quasi species of HIV-1 from a blood transfusion donor and recipients. Science. 1995;270:988–991. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean M, Carrington M, Winkler C, Huttley G A, Smith M W, Allikmets R, Goedert J J, Buchbinder S P, Vittinghoff E, Gomperts E, Donfield S, Vlahov D, Kaslow R, Saah A, Rinaldo C, Detels R, O'Brien S J. Genetic restriction of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS by a deletion allele of the CKR5 structural gene. Science. 1996;273:1856–1862. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Jong J J, De Ronde A, Keulen W, Tersmette M, Goudsmit J. Minimal requirements for the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 V3 domain to support the syncytium-inducing phenotype: analysis by single amino acid substitution. J Virol. 1992;66:6777–6780. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6777-6780.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desrosiers R C, Lifson J D, Gibbs J S, Czajak S C, Howe A Y, Arthur L O, Johnson R P. Identification of highly attenuated mutants of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1998;72:1431–1437. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1431-1437.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Estable M C, Bell B, Merzouki A, Montaner J S G, O'Shaugnessy M V, Sadowski I J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat variants from 42 patients representing all stages of infection display a wide range of sequence polymorphism and transcription activity. J Virol. 1996;70:4053–4062. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.4053-4062.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fouchier R A M, Groenink M, Kootstra N A, Tersmette M, Huisman H G, Miedema F, Schuitemaker H. Phenotype-associated sequence variation in the third variable domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 molecule. J Virol. 1992;66:3183–3187. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.3183-3187.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabuzda D H, Lawrence K, Langhoff E, Terwilliger E, Dorfman T, Haseltine W, Sodroski J. Role of vif in replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Virol. 1992;66:6489–6495. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6489-6495.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenough T C, Sullivan J L, Desrosiers R C. Declining CD4 T-cell counts in a person infected with nef-deleted HIV-1. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:236–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901213400314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenway A L, Mills J, Rhodes D, Deacon N J, McPhee D A. Serological detection of attenuated HIV-1 variants with nef gene deletions. AIDS. 1998;12:555–561. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199806000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iversen A K, Shpaer E G, Rodrgio A G, Hirsch M S, Walker B D, Sheppard H W, Merigan T C, Mullins J I. Persistence of attenuated rev genes in a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected asymptomatic individual. J Virol. 1995;69:5743–5753. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5743-5753.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson R P. Live attenuated AIDS vaccines: hazards and hopes. Nat Med. 1999;5:154–155. doi: 10.1038/5515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirchhoff F, Greenough T C, Brettler D B, Sullivan J L, Desrosiers R C. Brief report: absence of intact nef sequences in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:228–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501263320405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirchhoff F, Kestler III H W, Desrosiers R C. Upstream U3 sequences in simian immunodeficiency virus are selectively deleted in vivo in the absence of an intact nef gene. J Virol. 1994;68:2031–2037. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.2031-2037.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korber B, Hahn B, Foley B, Mellors J W, Leitner T, Myers G, McCutchan F, Kuiken C. Human retroviruses and AIDS database 1997. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Learmont J, Cook L, Dunckley H, Sullivan J S. Update on long-term symptomless HIV type 1 infection in recipients of blood products from a single donor. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11:1. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Learmont J, Tindall B, Evans L, Cunningham A, Cunningham P, Wells J, Penny R, Kaldor J, Cooper D. Long-term symptomless HIV-1 infection in recipients of blood products from a single donor. Lancet. 1992;340:863–867. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93281-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Learmont J, Geczy A F, Mills J M, Ashton L J, Raynes-Greenow C H, Garsia R J, Dyer W B, McIntyre L, Oelrichs R B, Rhodes D I, Deacon N J, Sullivan J S. Immunologic and virologic status after 14 to 18 years of infection with an attenuated strain of HIV-1. A report from the Sydney Blood Bank Cohort. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1715–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906033402203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mariani R, Kirchhoff F, Greenough T C, Sullivan J L, Desrosiers R C, Skowronski J. High frequency of defective nef alleles in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1996;70:7752–7764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7752-7764.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michael N L, Chang G, D'Arcy L A, Ehrenberg P K, Mariani R, Busch M P, Birx D L, Schwartz D H. Defective accessory genes in a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected long-term survivor lacking recoverable virus. J Virol. 1995;69:4228–4236. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4228-4236.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhodes D, Solomon A, Bolton W, Wood J, Sullivan J, Learmont J, Deacon N. Identification of a new recipient in the Sydney blood bank cohort: a long-term HIV type 1-infected seroindeterminate individual. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1999;15:1433–1439. doi: 10.1089/088922299309946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roger M. Influence of host genes on HIV-1 disease progression. FASEB J. 1998;9:625–632. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.9.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruprecht R M, Baba T W, Rasmussen R, Hu Y, Sharma P L. Murine and simian retrovirus models: the threshold hypothesis. AIDS. 1996;10(Suppl. A):S33–S40. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199601001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salvi R, Garbuglia A R, Di Caro A, Pulciani S, Montella F, Benedetto A. Grossly defective nef gene sequences in a human immunodeficiency virus type-1 seropositive long-term nonprogressor. J Virol. 1998;72:3646–3657. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3646-3657.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw J P, Utz P J, Durand D B, Toole J J, Emmel E A, Crabtree G R. Identification of a putative regulator of early T cell activation genes. Science. 1988;241:202–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shugars D C, Smith M S, Glueck D H, Nantermet P V, Seiller-Moiseiwitsch F, Swanstrom R. Analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nef gene sequences present in vivo. J Virol. 1993;67:4639–4650. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4639-4650.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith M W, Dean M, Carrington M, Winkler C, Huttley G A, Lomb D A, Goedert J J, O'Brien T R, Jacobson L P, Kaslow R, Buchbinder S, Vittinghoff E, Vlahov D, Hoots K, Hilgartner M W, O'Brien S J. Contrasting genetic influence of CCR2 and CCR5 variants on HIV-1 infection and disease progression. Science. 1997;277:959–965. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stewart G J, Ashton L J, Biti R A, Ffrench R A, Bennetts B H, Newcombe N R, Benson E M, Carr A, Cooper D A, Kaldor J M. Increased frequency of CCR-5 and delta 32 heterozygotes among long-term non-progressors with HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 1997;11:1833–1838. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199715000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Switzer W M, Wiktor S, Soriano V, Silva-Graca A, Mansinho K, Coulibaly I-M, Ekpini E, Greenberg A E, Folks T M, Heneine W. Evidence of Nef truncation in human immunodeficiency virus type 2 infection. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:65–71. doi: 10.1086/513819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang B, Ge Y, Palasanthirin S H, Xiang J, Ziegler J, Dwyer D E, Randle C, Dowton D, Cunningham A, Saksena N. Gene defects clustered at the C-terminus of the vpr gene of HIV-1 in long-term nonprogressing mother and child pair: in vivo evolution of vpr quasispecies in blood and plasma. Virology. 1996;223:224–232. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whatmore A M, Cook N, Hall G A, Sharpe S, Rud E W, Cranage M P. Repair and evolution of nef in vivo modulates simian immunodeficiency virus virulence. J Virol. 1995;69:5117–5123. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.5117-5123.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang L, Huang Y, Yuan H, Tuttleton S, Ho D D. Genetic characterization of vif, vpr, and vpu sequences from long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Virology. 1997;228:340–349. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]