Abstract

Bovine papillomavirus type 1 (BPV-1) late gene expression is regulated at both transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels. Maturation of the capsid protein (L1) pre-mRNA requires a switch in 3′ splice site utilization. This switch involves activation of the nucleotide (nt) 3605 3′ splice site, which is utilized only in fully differentiated keratinocytes during late stages of the virus life cycle. Our previous studies of the mechanisms that regulate BPV-1 alternative splicing identified three cis-acting elements between these two splice sites. Two purine-rich exonic splicing enhancers, SE1 and SE2, are essential for preferential utilization of the nt 3225 3′ splice site at early stages of the virus life cycle. Another cis-acting element, exonic splicing suppressor 1 (ESS1), represses use of the nt 3225 3′ splice site. In the present study, we investigated the late-stage-specific nt 3605 3′ splice site and showed that it has suboptimal features characterized by a nonconsensus branch point sequence and a weak polypyrimidine track with interspersed purines. In vitro and in vivo experiments showed that utilization of the nt 3605 3′ splice site was not affected by SE2, which is intronically located with respect to the nt 3605 3′ splice site. The intronic location and sequence composition of SE2 are similar to those of the adenovirus IIIa repressor element, which has been shown to inhibit use of a downstream 3′ splice site. Further studies demonstrated that the nt 3605 3′ splice site is controlled by a novel exonic bipartite element consisting of an AC-rich exonic splicing enhancer (SE4) and an exonic splicing suppressor (ESS2) with a UGGU motif. Functionally, this newly identified bipartite element resembles the bipartite element composed of SE1 and ESS1. SE4 also functions on a heterologous 3′ splice site. In contrast, ESS2 functions as an exonic splicing suppressor only in a 3′-splice-site-specific and enhancer-specific manner. Our data indicate that BPV-1 splicing regulation is very complex and is likely to be controlled by multiple splicing factors during keratinocyte differentiation.

Alternative pre-mRNA splicing is an important feature of gene control employed by many viruses and eukaryotic cells (28, 33). In many cases, the mechanisms that regulate splicing remain a mystery. Elucidation of the sequences flanking splice sites and their binding to multiple splicing factors has greatly promoted our understanding of the general splicing machinery (reviewed in references 1, 18, 30, 36, and 48). Recent progress has been made in the identification of a number of exonic and intronic auxiliary splicing elements in viral and cellular genes that promote or repress utilization of alternative splice sites. Work in many laboratories has suggested that, through interaction with multiple cellular splicing factors, exonic or intronic splicing enhancers and suppressors play critical roles in regulating selection of upstream or downstream splice sites.

Two classes of exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs) have been reported. The purine-rich ESEs are the most common and are usually located downstream of a suboptimal 3′ splice site. Through interactions with serine-arginine-rich (SR) proteins, purine-rich ESEs recruit U2AF to suboptimal 3′ splice sites and stimulate spliceosome assembly (16, 26, 32, 35, 42, 43, 55, 61). Purine-rich ESEs can also suppress splicing of a pre-mRNA when they are located in a regulated intron (13, 22). Thus, a purine-rich ESE can function as a splicing enhancer or a splicing suppressor depending on its location. Another class of ESEs is the AC-rich element (ACE). ACEs were identified by in vivo selection experiments and were found to stimulate splicing both in vivo and in vitro (8). AC-rich ESEs have been shown to be involved in the regulated splicing of both viral and cellular genes (8, 15). The mechanism of action of AC-rich ESEs remains largely unknown, although these elements have been proposed to function in a manner similar to that of the purine-rich ESEs.

Exonic splicing suppressors or silencers (ESSs) have recently been identified in several pre-mRNAs (2, 3, 5, 9, 10, 37, 39, 41, 54, 56, 57). These cis elements negatively regulate the utilization of upstream 3′ splice sites. They are frequently located downstream of a juxtaposed ESE but can also function upstream of an ESE (39, 47, 56). Thus, the ESS appears to antagonize the function of the ESEs. Unlike those of the ESEs, the sequences of the ESSs show little similarity to each other. However, each of the ESSs appears to contain a functional core motif. The ESSs bind a number of cellular splicing factors, including SR proteins (57) for the BPV-1 ESS, SC35 for the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tat exon 3 ESS (29), hnRNP H for the rat β-tropomyosin exon 7 ESS (7), and hnRNP A1 for the FGFR 2 K-SAM ESS and for the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tat exon 2 ESS (6, 11). Moreover, the role of the fibronectin EDA ESS has been implicated in the maintenance of an RNA conformation that facilitates display of the adjacent ESE SR protein binding sequences (31). Thus, ESSs may function through multiple mechanisms.

Regulation of bovine papillomavirus type 1 (BPV-1) gene expression at a posttranscriptional level involves both alternative splicing and alternative polyadenylation. The majority of the viral early transcripts are processed using a common 3′ splice site at nucleotide (nt) 3225 and early poly(A) site at nt 4203 in the undifferentiated keratinocyte at early stages of virus infection. However, maturation of the viral late primary transcript to generate the major capsid (L1) mRNA requires utilization of an alternative 3′ splice site at nt 3605 and the late-stage-specific poly(A) site at nt 7175. In situ hybridization studies have demonstrated that the 3605 3′ splice site is utilized only in the fully differentiated keratinocytes during late stages of the virus life cycle (4). Further investigations into the molecular mechanisms that regulate BPV-1 alternative splicing led us to identify three cis-acting elements between the nt 3225 3′ splice site and the nt 3605 3′ splice site. We demonstrated that two purine-rich ESEs, SE1 and SE2, are essential for preferential utilization of the nt 3225 3′ splice site in vitro and in vivo and that this function is mediated through interaction with cellular SR protein splicing factors (54, 55). SE1 and SE2 are also intronic with respect to the nt 3605 3′ splice site and therefore, as mentioned above, have the potential for repressing this site. The third element, an ESS, is located immediately downstream of SE1 and 122 nt upstream of SE2 and suppresses use of the nt 3225 3′ splice site both in vitro (54, 56, 57) and in vivo (58). This element requires an upstream suboptimal 3′ splice site for its function (58), contains a GGCUCCCCC functional core motif, and binds multiple splicing factors, including several SR proteins (57). The mechanism of action of the ESS is poorly understood but may involve interference with normal bridging and recruitment activities of SR proteins. Although these studies have provided us some clues about the regulation of the nt 3225 3′ splice site, little is known about the nature of the nt 3605 3′ splice site or its regulation.

In this study, we have investigated the BPV-1 late-stage-specific nt 3605 3′ splice site and have shown that this site is suboptimal and contains a nonconsensus branch point sequence (BPS) and a polypyrimidine tract (PPT) with interspersed purines. We also showed that SE2 does not function as an intronic splicing repressor. However, our studies revealed that the nt 3605 3′ splice site is regulated by a novel bipartite exonic element consisting of an AC-rich ESE and a UGGU motif-containing ESS. This element functionally resembles the BPV-1 SE1-ESS bipartite element that regulates selection of the upstream nt 3225 3′ splice site (54–58). We have designated this AC-rich ESE SE4 and have designated the UGGU motif-containing ESS ESS2, and we have renamed the BPV-1 ESS (53–58) ESS1. SE4 also functioned on a heterologous 3′ splice site and stimulated splicing of pre-mRNAs containing the nt 3225 3′ splice site. However, ESS2 functioned only in a 3′-splice-site-specific and enhancer-specific manner.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

To construct BPV-1 late minigene expression vectors without a 3225 3′ splice site (Δ3225 3′ ss), the XhoI and Asp718 fragments containing the nt 3225 3′ splice site, SE1, and ESS1, were deleted from plasmids p3231(wt), p3033(SE2m), and p3034(SE2d) (55). Since the Asp718 site is about 20 nt upstream of SE2, this strategy created plasmids p3072(wtSE2), p3073(SE2m), and p3074(SE2d) with only a single 3′ splice site, the nt 3605 3′ splice site.

To replace the wild-type (wt) SE2 with the adenovirus (Ad) IIIa repressor element (3RE) in the BPV-1 late gene expression vector, an overlap extension PCR technique (12, 17) was performed on plasmid p3030(pZMZ19-1) (54). Basically, two pairs of primers were used for PCR. Primer oZMZ194 (5′- ACGGTACCGGTGGACTTGGCATC/GCGTGGAGGAATATGACGAGGA CGATGAGTACGAGCCAGAGGACGGCGA/TGACTCTCCCAAGGCGC ACCAC-3′) was complementary to primer oZMZ195 (5′-GTGGTGCGCCTT GGGAGAGTCA/TCGCCGTCCTCTGGCTCGTACTCATCGTCCTCG TCATATTCCTCCACGC/GATGCCAAGTCCACCGGTACCGT-3′). oZMZ194 and oZMZ195 contain the 3RE in the middle of the oligonucleotide sequence and were combined with primers oCCB73 (5′-GGCATTAAAAGGGCAGACCTG-3′) and oZMZ164 (5′-ATTTTTGTCTCTCTGTCGG-3′), respectively, for separate PCRs. The two PCR products were then gel purified and annealed together through their overlapping sequences. Finally, the annealed PCR mixture was reamplified by PCR using the primer oCCB73 in combination with the primer oZMZ164. The reamplified PCR products were digested with XhoI and BstXI. The 821-bp XhoI and BstXI fragment was swapped into the corresponding site of plasmid p3231. The new plasmid, p3084, containing the 3RE substituted for SE2, was verified by sequencing. Subsequently, the XhoI and Asp718 fragments containing the nt 3225 3′ splice site, SE1, and ESS1 were deleted from plasmid p3084 to create plasmid p3085 with only a single 3′ splice site, the nt 3605 3′ splice site.

Ad IIIa expression vectors pGDIIIa and pGDIIIa(−3RE) were obtained from G. Akusjärvi (22, 25). pGDIIIa has a 3RE in its intron, whereas pGDIIIa(−3RE) has no 3RE but a rabbit β-globin sequence substitution in the position (see Fig. 2). Replacement of the β-globin insert in pGDIIIa(−3RE) by BPV-1 SE2 or ESS was carried out by cloning of annealed synthetic oligonucleotides containing SE2 or ESS sequences into the vector at BglII and EagI sites as described previously (22) and confirmed by sequencing. The new plasmids, p3090(SE2) and p3091(ESS), were then used to prepare DNA templates.

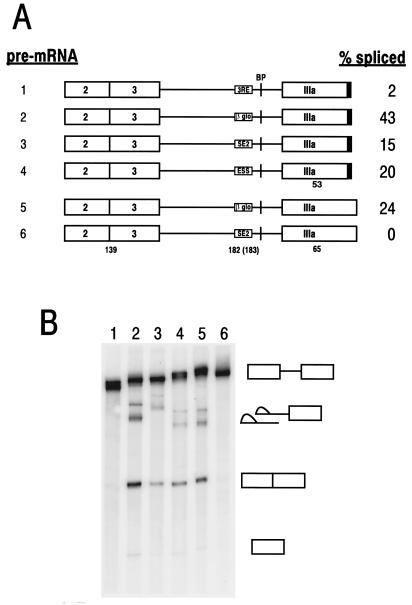

FIG. 2.

BPV-1 SE2 functions in vitro as an intronic splicing repressor in an Ad late IIIa pre-mRNA. (A) The maps of the Ad IIIa pre-mRNAs with (pre-mRNAs 1 to 4) or without (pre-mRNAs 5 and 6) a U1 binding site (5′ splice site) (solid box) at the 3′ end. Exons (large boxes) and introns (lines) are indicated. The BP is shown as a vertical line. The 3RE or its substitutions are located within the intron immediately upstream of the BP and are individually labeled in the corresponding box. The numbers below the diagrams are the sizes in nucleotides of the exons and introns. Splicing efficiencies are shown on the right and were calculated as described previously (55) from the splicing gel in panel B. (B) Splicing gel, showing the identities of the corresponding splicing products on the right (from top to bottom: pre-mRNAs, splicing intermediates, fully spliced products, and 5′ exons). The products from each splicing reaction were analyzed by electrophoresis on an 8% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gel. The numbers at the top of the gel indicate the pre-mRNAs in panel A used for splicing.

Preparation of DNA templates and pre-mRNAs.

The BPV-1 DNA templates were generated by PCR using a chimeric 5′ T7-BPV-1 primer (oFD127, 5′- TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGA/GCGCCTGGCACCGAATCC-3′) combined with an antisense 3′ primer with a 5′ end at nt 3640 (oZMZ158), nt 3665 (oZMZ159), nt 3690 (oZMZ160), nt 3715 (oZMZ161), nt 3746 (oCCB57), or nt 3784 (oZMZ154) (see Fig. 3A and 5). To create a DNA template transcribing a pre-mRNA with an nt 3764 5′ splice site GC-to-GU or -GG mutation but with its 3′ end at nt 3784, the 5′ primer described above was combined with a mutagenic antisense 3′ primer, oCCB62 (nt 3764 GU) or oCCB86 (nt 3764 GG) (see Fig. 3A). Alternatively, a chimeric 3′ BPV-1-U1 binding site antisense primer (oZMZ 166; 5′-GTACTCACCCC/TTTTCACCCGAAAGCGATAGC-3′) was used to substitute for other 3′ antisense primers for the PCR preparation of the DNA templates which transcribe pre-mRNAs containing a U1 binding site downstream of the nt 3605 3′ splice site (see Fig. 3B). Other mutagenic nt 3715 3′ antisense primers (oZMZ184 [5′-GGACGAGACTACCCTGGCGTCCGCCGAACCAGGTGGTGGTGCAGTTCTCG-3′], oZMZ185 [5′-TTTCAGC ACCGTTGTCAGCAACTGTCAGCATGGTGGTGGTGCAGTTCTCG-3′], oZMZ186 [5′-TTTCAGCACCGACCACAGCAACTGTGAACCAGGTGGTGGTGCAGTTCTCG-3′], and oZMZ187 [5′-TTTCAGCACCGACCACAGCAACTGTCAGCATGGTGGTGGTGCAGTTCTCG-3′]) were also used to generate the DNA templates that transcribe pre-mRNAs with defined mutations in exon 2 (see Fig. 7A, top).

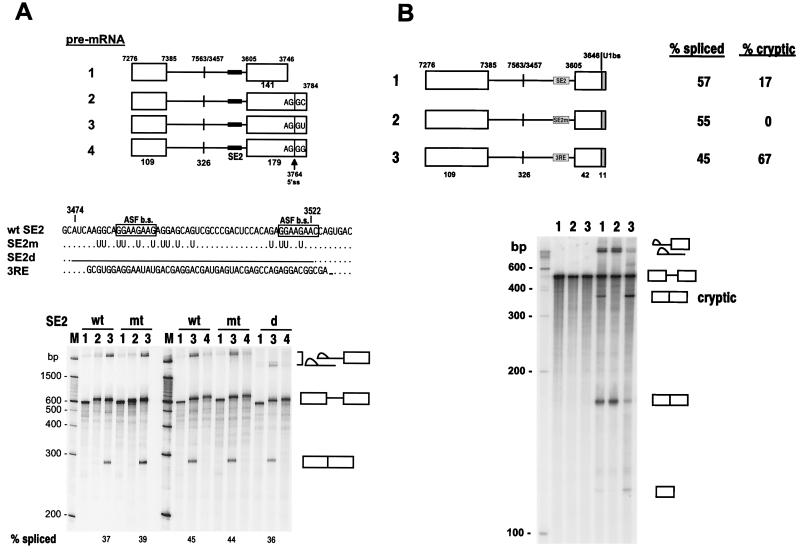

FIG. 3.

In vitro analysis of the role of BPV-1 SE2 in the regulation of the nt 3605 3′ splice site in BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs. (A) BPV-1 SE2 does not function as an intronic splicing repressor in BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs containing no nt 3225 3′ splice site. Structures of the pre-mRNAs with or without a downstream exon 2 5′ splice site (5′ ss) used for in vitro splicing are shown at the top of the panel. The nt 3764 5′ splice site is indicated by an arrowhead, with its splice junction sequence, AG|GC, AG|GU, or AG|GG, shown. Each pre-mRNA has three versions containing a wt (from p3072) or mt (from p3073) SE2 or with SE2 deleted (from p3074). The numbers above the pre-mRNA structures are nucleotide positions in the BPV-1 genome. The numbers below the structures indicate the sizes in nucleotides of exons (open boxes) and introns (lines). The sequences of SE2 and its substitutions, including the Ad 3RE, are shown in the middle. At the bottom of the panel are two splicing gels. The corresponding splicing products are displayed on the right. The products from each splicing reaction were analyzed by electrophoresis on an 8% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gel. The numbers at the top of the gel correspond to each pre-mRNA used for splicing. Splicing efficiencies are shown at the bottom of the gel and were calculated as described previously (55). (B) BPV-1 SE2 and Ad 3RE stimulate cryptic splicing in BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs. A consensus 5′ splice site is located at nt 3646 in these pre-mRNAs. The pre-mRNAs were transcribed from p3072(wt SE2), p3073(mt SE2), and p3074(Ad 3RE) DNA templates, respectively. Other descriptions are the same as for panel A.

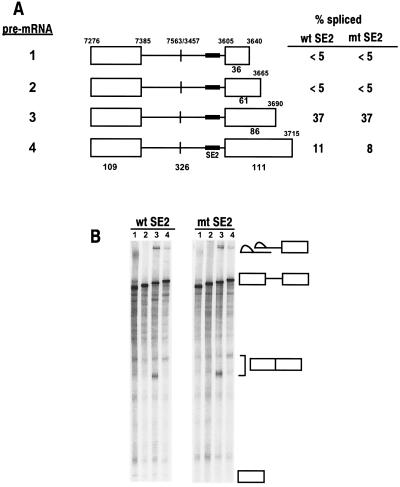

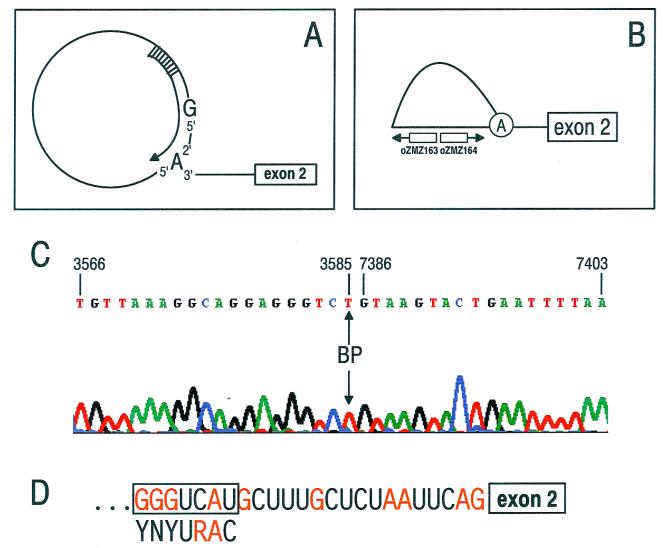

FIG. 5.

Identification of a novel bipartite splicing regulatory element downstream of the nt 3605 3′ splice site. (A) Maps of the pre-mRNAs with various lengths of exon 2. The numbers above the pre-mRNAs are nucleotide positions in the BPV-1 genome. The numbers below the pre-mRNAs indicate the sizes in nucleotides of exons (open boxes) and introns (lines). Each pre-mRNA has either a wt SE2 (from p3072) or an mt SE2 (from p3073). The splicing efficiency of each pre-mRNA was calculated as described previously (53) from the splicing gel in panel B. (B) Splicing gel, showing the corresponding splicing products on the right. The products from each splicing reaction were analyzed as for Fig. 2B. The numbers at the top of the gel correspond to each pre-mRNA with wt or mt SE2 in panel A used for splicing.

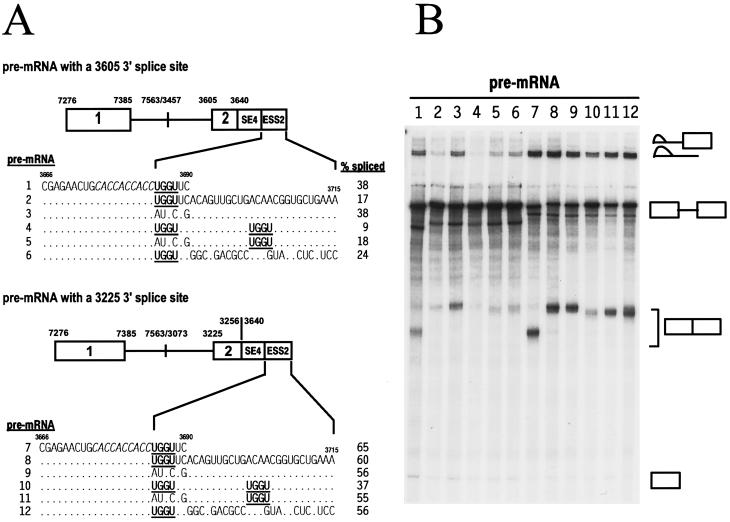

FIG. 7.

Identification of a UGGU splicing suppressor motif. (A) Structures of two different sets of BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs used for splicing. Two sets of the pre-mRNAs transcribed, respectively, from PCR templates generated from plasmid p3072 (top; the pre-mRNAs with a 3605 3′ splice site) and p3030 (bottom; the pre-mRNAs with a 3225 3′ splice site) share the same exon 1 but differ in their introns and exon 2. The following pre-mRNA-specific 3′ primers were used: oZMZ160 (pre-mRNA 1), oZMZ161 (pre-mRNA 2), oZMZ185 (pre-mRNAs 3 and 9), oZMZ186 (pre-mRNAs 4 and 10), oZMZ187 (pre-mRNAs 5 and 11), oZMZ184 (pre-mRNAs 6 and 12), oZMZ168 (pre-mRNA 7), and oZMZ183 (pre-mRNA 8). The descriptions of the diagrams are the same as for Fig. 6B. The SE4 in exon 2 is boxed in each diagram. The nucleotide sequence of the SE4, with an italic ACE motif, is shown along with that of the ESS2 or its derivatives in which the UGGU motifs are in boldface and underlined. The splicing efficiency (% spliced) was calculated from the gel in panel B as described previously (53). (B) Splicing gel, showing the corresponding splicing products on the right. The products from each splicing reaction were analyzed as for Fig. 2B. The numbers at the top of the gel correspond to each pre-mRNA in panel A used for splicing.

For testing the putative SE4 or ESS2 at a heterologous nt 3225 3′ splice site, BPV-1 DNA templates were produced from plasmid p3030 by PCR using the 5′ primer oFD127 described above combined with one of the following 3′ antisense primers: oZMZ84 (56), oZMZ102 (56), oZMZ168 (5′-GAACCAGGTGGTGGTGCAGTTCTCGTAGCGATGTCTATGGTTCTTTTTCAC/GGATGCGACCCAGACTCCGTC-3′), oZMZ169 (5′-GAACCAGGTGGTGGTGCAGTTCTCG/GGATGCGACCCAGACTCCGTC-3′), oZMZ170 (5′-GAACCAGGACTAGCATCAGCACTCG/GGATGCGACCCAGACTCCGTC-3′), oZMZ171 (5′-T TTCAGCACCGTTGTCAGCAACTGTGAACCAGGTGGTGGTGCAGTTC TCG/GGATGCGACCCAGACTCCGTC-3′), oZMZ172 (5′-TTTCAGCACCGTTGTCAGCAACTGT/GGATGCGACCCAGACTCCGTC-3′), or oZMZ173 (5′-TTTCAGCACCGTTGTCAGCAACTGT/GGCTGGGCTGGCTCGGCTTCTTTTCC-3′). The pre-mRNAs transcribed from these DNA templates were used for the in vitro splicing assay (see Fig. 6). Alternatively, the oZMZ168-generated DNA templates from plasmid p3030 were reamplified by PCR using the 5′ primer described above but a different 3′ antisense primer, oZMZ183 (5′- TTTCAGCACCGTTGTCAGCAACTGTGAACCAGGTGGTGGTGCAGTT CTCG-3′), oZMZ184, oZMZ185, oZMZ186, or oZMZ187, to create the DNA templates that transcribe pre-mRNAs with defined mutations in exon 2 (see Fig. 7A, bottom).

FIG. 6.

Functional analysis of SE4 and its downstream sequence ESS2 for selection of a heterologous nt 3225 3′ splice site for in vitro splicing. (A) Structures of the pre-mRNAs transcribed from plasmid p3030-derived DNA templates. The following pre-mRNA-specific 3′ primers were used: oZMZ84 (pre-mRNA 1), oZMZ102 (pre-mRNA 2), oZMZ168 (pre-mRNA 3), oZMZ169 (pre-mRNA 4), oZMZ170 (pre-mRNA 5), oZMZ171 (pre-mRNA 6), oZMZ172 (pre-mRNA 7), and oZMZ173 (pre-mRNA 8). Pre-mRNA 1 differs from pre-mRNAs 3 to 7 only in its SE1 region. The latter five pre-mRNAs had SE1 replaced by individual sequences as shown below the map. The ACE motif is underlined. The numbers above the sequences indicate nucleotide positions in the BPV-1 genome. The dots indicate unchanged nucleotides. Pre-mRNA 2 differs from pre-mRNA 8 by two different fragments downstream of SE1, boxed in the map. Other descriptions are the same as for Fig. 5A. (B) Splicing gel, showing the corresponding splicing products on the right. The products from each splicing reaction were analyzed as in Fig. 2B. The numbers at the top of the gel correspond to each pre-mRNA in panel A used for splicing. The splicing efficiency (% spliced) at the bottom of the gel was calculated as described previously (53).

Ad DNA templates were prepared from plasmids pGDIIIa, pGDIIIa(−3RE), p3090, and p3091 by PCR using a 5′ SP6 primer (oJR3) (56) combined with a 3′ antisense primer, oESR7 (5′-TTAAGGCCGGACGGCTGG-3′) or oZMZ165 (5′-GTACTCACCCC/CAGCGCCGCCCGCAC-3′), for transcribing a pre-mRNA with (oZMZ165) or without (oESR7) a U1 binding site at the 3′ end (see Fig. 2).

All DNA templates prepared as described above were gel purified and transcribed into pre-mRNAs by in vitro runoff transcription with T7 (for BPV-1) or SP6 (for Ad IIIa) RNA polymerase as described previously (53).

In vitro splicing and detection of splicing products.

The detailed protocols for in vitro splicing and detection of splicing products have been described in our previous publication (53).

BP mapping.

The branch point (BP)-mapping method was adapted from the literature (45) with minor modifications. To map the BP in the BPV-1 late pre-mRNA, an in vitro splicing assay of the cold pre-mRNA was performed under the standard splicing conditions (53). The spliced products were phenol extracted, ethanol precipitated, and resuspended in 10 μl of RNase-free water. The extracted products (4 μl) were then used for reverse transcription (RT) by Superscript II (Gibco-BRL, Rockville, Md.) under the conditions described by the manufacturer. An antisense primer, oZMZ163, with its 5′ end positioned at nt 7472 (5′-ATAACGTGTTCGGTCCCGC-3′) in the BPV-1 genome, was used for synthesis of the cDNA. For subsequent PCRs, half of the RT reaction mixtures were applied to the reactions. The cDNA was amplified by PCR with the same antisense primer, oZMZ163, in combination with a sense primer, oZMZ164 (see above), with its 5′ end positioned at nt 7490 in the BPV-1 genome. The PCR products were then gel purified and sequenced with the primer oZMZ164.

Transfection of 293 cells and RT-PCR analysis of spliced BPV-1 late mRNAs.

Transfectam reagent (Promega) was used to transfect 2 μg of wt or mutant (mt) expression vector DNA into human 293 cells plated in 60-mm-diameter dishes. Total cellular RNA was prepared after 48 h using TRIzol (Gibco-BRL) following the manufacturer's instructions. Following DNase I treatment, 500 ng of total cellular RNA was reverse transcribed at 42°C using random hexamers as primers and then amplified for 35 cycles using different pairs of primers as described in the figure legends. An L1 cDNA and a mixture of L2-L and L2-S cDNAs generated from L2 mRNAs spliced using the nt 3225 3′ splice site and 3605 3′ splice site, respectively, were used as PCR controls.

RESULTS

Mapping of the branch point of the BPV-1 late-stage-specific nt 3605 3′ splice site.

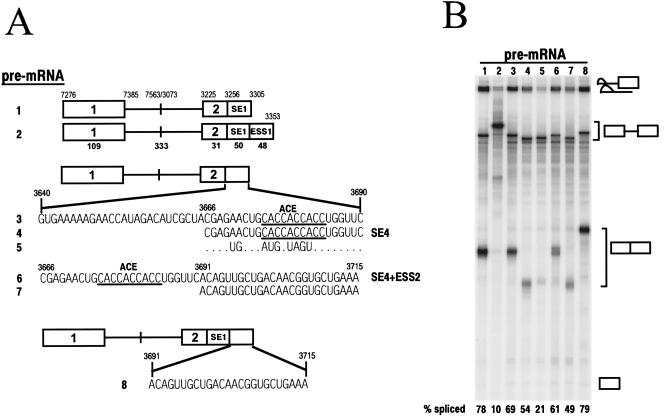

The nt 3605 3′ splice site is used only in highly differentiated keratinocytes at a late stage of viral infection (4). However, little is known about the regulation of this site. The BP of the site was mapped to determine if a nonconsensus BPS contributes to the suboptimal nature of the site. BP mapping requires efficient formation of splicing intermediates in vitro. Efficient in vitro splicing of a BPV-1 late pre-mRNA containing an nt 3605 3′ splice site was obtained using a consensus 5′ splice site or U1 binding site as a strong exonic splicing enhancer (see Fig. 3A, pre-mRNA 3) (24). Splicing of this pre-mRNA was carried out under splicing conditions described previously (53), and the splicing products were then used for mapping the BP (see Materials and Methods). Our strategy took advantage of the ability of Superscript II to read through the 5′-to-2′ phosphodiester bond present in lariat splicing intermediates and therefore to convert the lariat circle into linear cDNA that can be amplified by PCR (Fig. 1A and B) (45). The sequence of this cDNA is shown in Fig. 1C and demonstrates that the G residue at the 5′ end of the intron (nt 7386) is linked to the BP at nt 3585. Note, however, that the A residue of the BP was replaced by a T residue during RT, as reported previously (45). The BPS (nt 3580 to 3586) is shown in Fig. 1D and has a typical BP A residue, like most mammalian BPs. The BP is located 19 nt upstream of the nt 3605 3′ splice junction and is also typical in its location. However, the BPV-1 nt 3585 BPS (GGGUCAU [the BP is underlined]) deviates from the mammalian BP consensus sequence (YNYURAC) at four positions and is thus suboptimal.

FIG. 1.

Mapping of the BP at the nt 3605 3′ splice site by Superscript II RT-PCR and sequencing. (A) Diagram of a lariat-containing splicing intermediate produced from the wt SE2 pre-mRNA 3 (Fig. 3A) and direction of RT by Superscript II. (B) Diagram of the pair of primers designed for PCR and sequencing. (C) Sequence of the PCR products obtained using oZMZ164 as the primer. The numbers are nucleotide positions in the BPV-1 genome. An arrowhead indicates the BP. Note that the BP A is converted to a T. (D) Sequence of the nt 3605 3′ splice site. The BPS is in a box, under which the mammalian BPS consensus sequence is displayed for comparison.

Between the nt 3585 BP and the nt 3605 3′ splice junction is a PPT. Similar to many other viral and mammalian PPTs, this PPT contains four interspersed purines (Fig. 1D) and is therefore predicted to be suboptimal. Based on the sequence data of both the BPS and the PPT, we conclude that the nt 3605 3′ splice site is a weak or suboptimal 3′ splice site that is likely to be regulated by intronic or exonic cis elements.

The intronic purine-rich SE2 upstream of the nt 3585 BP does not function as a repressor for nt 3605 3′-splice-site usage.

SE2 is a purine-rich exonic splicing enhancer that has a strong affinity for SR proteins and regulates utilization of the nt 3225 3′ splice site in BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs (54, 55). However, in addition to its exonic location with respect to the nt 3225 3′ splice site, SE2 is also intronic with respect to the nt 3605 3′ splice site and lies only 55 nt upstream of the nt 3585 BP. A similar SR protein binding element, the Ad 3RE, has been shown to inhibit use of a downstream 3′ splice site by blocking the binding of the U2 snRNP at the BP (22, 23). We therefore hypothesized that SE2 may also function as an intronic splicing repressor, especially given the suboptimal nature of the nt 3605 3′ splice site. Several approaches were used to address this question. First, an Ad IIIa pre-mRNA was constructed in which the 3RE was replaced by SE2, and the splicing efficiency of this chimeric pre-mRNA was then analyzed under in vitro splicing conditions. An Ad IIIa pre-mRNA in which the 3RE was replaced by β-globin sequences served as a control (22, 23). As expected, both the Ad 3RE and the BPV-1 SE2 repressed splicing of the Ad IIIa pre-mRNA compared with the β-globin control sequences, although SE2 did not repress as strongly as the 3RE (Fig. 2, compare pre-mRNAs 1 and 3 to pre-mRNA 2). The efficiency of the suppression by SE2 was comparable to that of suppression by the BPV-1 ESS, a pyrimidine-rich ESS that also binds multiple RNA splicing factors, including SR proteins (57). The pre-mRNAs described above also contained a strong 5′ splice site at the 3′ end of exon 2. A downstream 5′ splice site has been shown to function as a splicing enhancer and can activate the splicing of an upstream intron (19, 20, 24, 46). The ability of SE2 to function as an intronic splicing suppressor was also tested in an Ad IIIa pre-mRNA lacking a downstream 5′ splice site. Complete suppression of splicing of this pre-mRNA was seen (Fig. 2, compare pre-mRNAs 5 and 6). Thus, the intronic splicing suppressor function of SE2 can be partially counteracted by a downstream 5′ splice site.

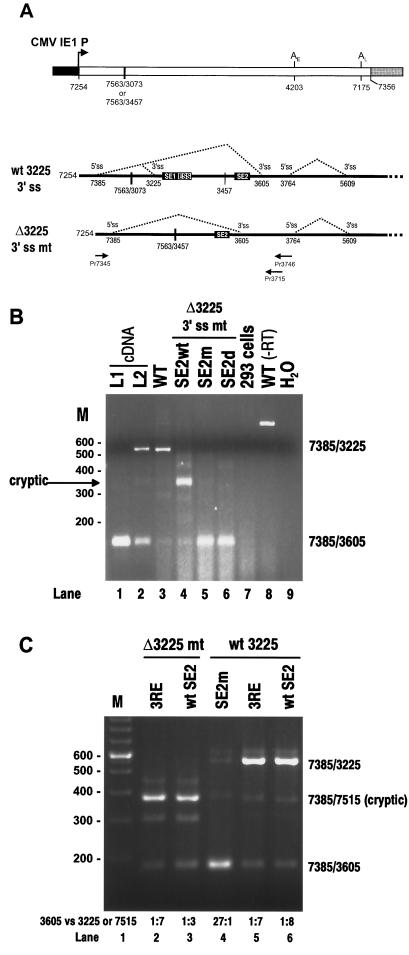

To determine if SE2 also functions as an intronic splicing suppressor in BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs, several nt 3605 3′ splice site-containing pre-mRNAs were constructed with either a wt or an mt SE2 element (Fig. 3). These pre-mRNAs also differed by the presence or absence of a downstream 5′ splice site as a splicing enhancer. The pre-mRNAs were tested under in vitro splicing conditions (53). As shown in Fig. 3A, the only pre-mRNA that gave detectable splicing products was pre-mRNA 3, which contains a consensus downstream 5′ splice site. No significant difference in splicing efficiency was seen for pre-mRNAs containing a wt or an mt SE2, suggesting that SE2 does not function as an intronic splicing repressor in BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs. Moving the downstream 5′ splice site 118 nt closer to the nt 3605 3′ splice site enhanced splicing efficiency somewhat, but again, the total splicing efficiencies in the wt- and mt-SE2-containing pre-mRNAs were indistinguishable (Fig. 3B, compare pre-mRNAs 1 and 2). However, in this context, wt SE2, but not the mt SE2, activated a cryptic 3′ splice site upstream of SE2. Replacement of SE2 with the Ad 3RE element gave a pattern of splicing similar to that seen for SE2. However, the cryptic 3′ splice site was used 67% of the time with the 3RE compared with only 17% of the time with SE2 (Fig. 3B, compare pre-mRNAs 1 and 3). These data suggest that, in combination with a strong downstream 5′ splice site, both the BPV-1 SE2 and the Ad 3RE function preferentially as ESEs and activate an upstream cryptic 3′ splice site rather than functioning as intronic splicing suppressors on the downstream 3′ splice site. By itself, SE2 is incapable of activating the upstream cryptic 3′ splice site in vitro (Fig. 3A, pre-mRNAs 1, 2, and 4).

Activation of cryptic splicing by SE2 or the 3RE was also demonstrated in vivo in a BPV-1 minigene expression vector. In the first experiment, the effects of mutations in SE2 were tested in a BPV-1 minigene expression vector in which the nt 3225 3′ splice site, SE1, and the ESS were deleted (Fig. 4A). In this context, efficient utilization of the nt 3605 3′ splice site was seen in 293 cells only for pre-mRNAs containing point mutations in SE2 or with SE2 deleted (Fig. 4B, lanes 5 and 6). In contrast, splicing of a pre-mRNA containing wt SE2 was accomplished predominantly through activation of an upstream cryptic 3′ splice site (Fig. 4B, lane 4). Subsequent sequence analysis of the cryptically spliced mRNA mapped the cryptic 3′ splice junction at BPV-1 nt 7515 (data not shown). In the second experiment, the Ad 3RE was substituted for SE2 in BPV-1 late minigene expression vectors with or without the nt 3225 3′ splice site, SE1, and the ESS (Fig. 4A). Transfection of 293 cells with these expression vectors revealed that the 3RE is functionally equivalent to SE2 in stimulating selection of an upstream 3′ splice site at the expense of the downstream nt 3605 3′ splice site (Fig. 4C, lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6). Mutation of SE2 in pre-mRNAs either with or without the nt 3225 3′ splice site switched splice site selection from the upstream splice site (nt 3225 or cryptic, respectively) to the downstream nt 3605 3′ splice site (Fig. 4B and C). These data are consistent with our previously published observations (55). It is difficult at present to determine if this in vivo switch was due to a relief of repression of the downstream 3′ splice site, a loss of enhancer activity on the upstream 3′ splice site, or both. Taken together, our data suggest that SE2 plays a role as an exonic splicing enhancer only in BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs even though it is capable of functioning as an intronic splicing suppressor in an Ad late IIIa pre-mRNA.

FIG. 4.

In vivo functional analysis of the BPV-1 SE2 and Ad 3RE in BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs. (A) Structure of the BPV-1 late minigene transcription unit expression vectors and the splicing patterns of the pre-mRNAs expressed from these vectors. At the ends of the late minigene (open box) are the cytomegalovirus (CMV) IE1 promoter (solid box) and pUC18 (shaded box). The numbers below the lines are the nucleotide positions in the BPV-1 genome. Early and late poly(A) sites are indicated as AE and AL above the lines. A large deletion in the intron region of the genome is shown by a heavy vertical line. Below the minigene diagram are the structures of the minigene transcripts. The relative positions of SE1, ESS, and SE2 are shown, as well as the nucleotide positions of the 5′ splice site (5′ss) and 3′ splice site (3′ss). Two pairs of primers used for the RT-PCR assays shown in panels B and C are indicated by arrows under the transcripts and named by the locations of their 5′ ends. The following plasmids were used for transfection of 293 cells: p3231(wt 3225 3′ ss + wt SE2), p3033(wt 3225 + SE2m), p3084(wt 3225 3′ ss + 3RE), p3072(Δ3225 3′ss + wt SE2), p3085(Δ3225 3′ss + 3RE), p3073(Δ3225 3′ss + SE2m), and p3074(Δ3225 3′ss + SE2d) (see Materials and Methods for construction of the plasmids). The nucleotide sequences of wt and mt SE2 and Ad 3RE in the pre-mRNAs expressed from the plasmids described above are shown in Fig. 3A. (B and C) RT-PCR analysis of BPV-1 late mRNAs transcribed and spliced in 293 cells from the expression vectors containing wt or mt SE2 or 3RE with or without the nt 3225 3′ splice site as indicated above each gel. Total cell RNA was extracted and digested with RNase-free DNase I before RT-PCR analysis. Several controls were included for the assays, including p3231(wt)-transfected 293 cell RNAs, untransfected 293 cell RNA, and water controls. Total cell RNA extracted from p3231(wt)-transfected 293 cells but not treated with RNase-free DNase I [WT (−RT)] and BPV-1 L1 cDNA and a 10:1 mixture of L2-L and L2-S cDNA were also used as templates for PCR amplification in panel B. The predicted sizes of the RT-PCR products differ between the panels due to the use of different sets of primers: Pr7345 and Pr3715 for panel B and Pr7345 and Pr3746 for panel C.

Identification of a novel bipartite splicing regulatory cis element downstream of the nt 3605 3′ splice site.

The suboptimal nature of the nt 3605 3′ splice site and the undetectable in vitro splicing activity seen with pre-mRNAs 1 and 2 (Fig. 3A) suggested that this splice site might be regulated by exonic cis elements similar to those that regulate the nt 3225 3′ splice site. In particular, our previous studies showed that the activity of an ESS can be dominant over that of an ESE in in vitro splicing assays (58). To map potential regulatory elements downstream of the nt 3605 3′ splice site, BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs containing various lengths of the exon downstream of this site were prepared and tested for splicing in vitro (Fig. 5A). Pre-mRNAs with 3′ ends at nt 3640 or 3665 gave no detectable splicing products, suggesting that there are no splicing enhancer elements between the nt 3605 3′ splice site and nt 3665 (Fig. 5, pre-mRNAs 1 and 2, respectively). In contrast, a pre-mRNA extending to nt 3690 showed considerable splicing activity (pre-mRNA 3). These data indicate the presence of an ESE and map its 3′ boundary to the region between nt 3665 and 3690. In addition, the splicing efficiency of this pre-mRNA was independent of the presence of a wt SE2 in the intron. This confirms our previous conclusion that SE2 does not function as an intronic splicing suppressor in BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs. Sequence analysis shows that the region between nt 3665 and 3690 is rich in A and C, a property of ACE-like enhancers (8). We have designated this ACE-like enhancer SE4. Surprisingly, pre-mRNA 4, which extends an additional 25 nt to nt 3715, showed more than a threefold reduction of splicing efficiency compared to pre-mRNA 3. Sequences downstream of nt 3715 had little additional effect on splicing in vitro (Fig. 3A). These results suggest that this region contains an ESS and that the 3′ boundary of this ESS is located between nt 3690 and 3715. We have designated this negative cis element ESS2 and renamed our previously published ESS ESS1 to distinguish the two elements (54, 56, 57, 58). Thus, SE4 and ESS2 form a bipartite splicing regulator that positively and negatively controls the usage of the upstream nt 3605 3′ splice site. This is reminiscent of the bipartite element (SE1 and ESS1) that regulates the nt 3225 3′ splice site.

BPV-1 SE4 functions as an ESE for a heterologous 3′ splice site.

To further characterize SE4, a BPV-1 late pre-mRNA containing the nt 3225 3′ splice site was used to test if SE4 could function as an ESE for a heterologous splice site. Previous studies demonstrated that the nt 3225 3′ splice site is suboptimal and requires an enhancer (SE1) for its function (54, 55). In the studies described below, SE1 was replaced by SE4 or SE4 derivatives, and the resulting pre-mRNAs were tested under in vitro splicing conditions (53). Pre-mRNAs containing a larger fragment spanning nt 3640 to 3690 (Fig. 6, pre-mRNA 3) or a smaller fragment containing just the AC-rich region and a few flanking nucleotides (Fig. 6, pre-mRNA 4) were spliced nearly as efficiently as a pre-mRNA containing SE1 (Fig. 6, pre-mRNA 1). However, a mutation in the ACE motif of SE4 reduced splicing about 2.5-fold (Fig. 6, pre-mRNA 5). These data indicate that SE4 can function as an ESE for a heterologous 3′ splice site and confirm that SE4 belongs to the ACE class of ESEs.

ESS2 contains a UGGU core suppressor motif, and two copies of this motif make a strong suppressor.

ESS2 was further characterized by mutational analysis in its natural context in an nt 3605 3′ splice site-containing pre-mRNA. In these studies, ESS2 sequences were kept at their normal positions relative to SE4. As shown in Fig. 5, addition of sequences between nt 3690 and 3715 repressed splicing more than twofold (also see Fig. 7, pre-mRNA 2). Surprisingly, extensive base substitutions within this region only partially restored splicing (Fig. 7, pre-mRNA 6), suggesting that ESS2 actually extends upstream of nt 3691. This is consistent with the observation that the sequences between nt 3691 and 3715 actually enhanced splicing of an nt 3225 3′ splice site-containing pre-mRNA almost as much as the ACE motif in SE4 (Fig. 6, compare pre-mRNAs 4 and 7), indicating that these sequences are not the suppressor. In contrast, point mutations in the sequence UGGU (Fig. 7, pre-mRNA 3) that lies immediately downstream of the ACE enhancer motif of SE4 but just upstream of nt 3691 fully restored splicing to that seen for pre-mRNA 1 (Fig. 7), suggesting that the sequence UGGU is an essential component of ESS2. However, the UGGU suppressor core motif appears not to function in vitro when located at the 3′ end of a pre-mRNA (Fig. 7, pre-mRNA 1). Similar observations have been made for the core motif GGCUCCCCC in ESS1 (57). Further evidence for a UGGU suppressor core motif comes from the observation that a UGGU sequence placed 16 nt downstream of the ACE enhancer motif (Fig. 7, pre-mRNA 5) suppressed splicing as efficiently as the original UGGU motif. In fact, duplication of the core motif (Fig. 7, pre-mRNA 4) reduced splicing efficiency even further, indicating that two copies of the UGGU motif are better than one copy for suppression of splicing.

The ability of ESS2 with the UGGU motif to function on a heterologous 3′ splice site was also tested. For these studies, the same mutations in ESS2 were tested in a BPV-1 nt 3225 3′ splice site-containing pre-mRNA. This system was chosen because the regulation of the nt 3225 3′ splice site by a bipartite splicing regulator (SE1 plus ESS1) has been extensively studied (54–57). SE1 and ESS1 were replaced by SE4 and ESS2 in the pre-mRNAs shown in Fig. 7. In multiple pre-mRNAs, a single copy of the UGGU motif did not suppress splicing (Fig. 7, pre-mRNAs 7 to 9, 11, and 12; also compare pre-mRNAs 4 and 6 in Fig. 6). However, almost twofold inhibition of SE4-enhanced splicing of the nt 3225 3′ splice site was obtained with two UGGU motifs (Fig. 7, pre-mRNA 10). Additional experiments were conducted to determine if three copies of the UGGU motif would suppress splicing even better than two copies. However, three copies of the UGGU motif (equally spaced at 16 nt) did not inhibit SE4-enhanced splicing of the nt 3225 3′ splice site any more efficiently than two copies (data not shown). In addition, neither two nor three copies of the UGGU motif inhibited SE1-stimulated splicing of the nt 3225 3′ splice site (data not shown). Based on these observations, we conclude that ESS2 contains a UGGU core motif that functions not only in a splice site-specific but also in an enhancer-specific manner.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated the suboptimal nature of the BPV-1 nt 3605 3′ splice site, a viral late-stage-specific 3′ splice site utilized only in fully differentiated keratinocytes. This 3′ splice site contains both a nonconsensus BPS and a suboptimal PPT. Such suboptimal features are typical of regulated 3′ splice sites and have been seen in several viral systems (25, 40), including the BPV-1 nt 3225 3′ splice site (54). In general, a conventional 3′ splice site is composed of three critical elements: a BPS, a PPT (usually with a stretch of U residues), and an AG dinucleotide at the 3′ end of the intron. If all three are consensus, they sequentially bind three different cellular splicing factors in order: U2AF35 binds first to the AG dinucleotide (50, 60), followed by U2AF65 binding to the PPT (14, 21, 34, 38, 44, 51, 52), and then U2 snRNP binds to the BPS (49, 59). In the assembly of the spliceosome, recognition of the 5′ splice site by U1 snRNP and the 3′ splice site by U2AF and the U2 snRNP is essential. Binding of cellular splicing factors to pre-mRNAs with a nonconsensus element is often inefficient, leading to poor splicing efficiency. These pre-mRNAs are frequently subject to regulation by intronic or exonic cis elements, such as ESEs and ESSs. The BPS GGGUCAU (the BP is underlined) at the BPV-1 nt 3605 3′ splice site deviates from the mammalian consensus YNYURAC at four positions. The PPT of this 3′ splice site has a length of 15 nt between the BPS and the AG dinucleotide. The PPT has no runs of uridines longer than three and also contains four interspersed purines. Thus, the weak nature of this site allows it to be subject to regulation by cis elements.

In previous studies, we demonstrated that BPV-1 SE2 functions as a strong ESE that regulates utilization of the upstream nt 3225 3′ splice site in BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs. The intronic location of SE2 with respect to the nt 3605 3′ splice site led us to hypothesize that SE2 might have an additional role as an intronic splicing repressor. This hypothesis was based on similarities between SE2 and the Ad 3RE, an element that functions as an intronic repressor and negatively regulates splicing of Ad IIIa pre-mRNA (22, 23). Both SE2 and the 3RE are purine rich, have high affinity for SR proteins, and have an intronic location near a BPS. Surprisingly, our data show that SE2, although not as strong as the 3RE, was capable of functioning as an intronic splicing repressor in an Ad IIIa pre-mRNA, but not in a BPV-1 late pre-mRNA. In the context of a BPV-1 late pre-mRNA, both SE2 and the 3RE functioned preferentially as ESEs and activated a cryptic splice site further upstream. The contradictory functions of both SE2 and the 3RE in two different systems may be attributed to differences in spacing between the element and the downstream BPS. In the Ad IIIa pre-mRNA, both the 3RE and SE2 were located only 6 nt upstream of the BP, whereas these elements were positioned 57 nt upstream of the nt 3605 3′ splice site BP in the BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs. Thus, inhibition of splicing of the Ad IIIa pre-mRNAs by both the 3RE and SE2 could easily be explained by steric hindrance between SR proteins binding to these elements and U2 snRNP binding at the BPS. In the case of BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs, SE2 and the 3RE were much further upstream of the BP. This greater distance may prevent the RNA-SR protein complex from physically reaching the downstream BP. Further studies are needed to test this hypothesis by moving SE2 or the 3RE closer to the BP at nt 3585 and analyzing if they then function as an intronic splicing repressor in BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs. However, examination of the sequence (nt 3535 to 3584) between SE2 and the nt 3585 BP showed two additional putative ASF/SF2 binding sites (SRSASGA, where S represents G or C and R represents purine) (27) that are 25 nt apart. We named this putative splicing enhancer SE3. Interestingly, one of the ASF/SF2 binding sites in SE3 is just 5 nt upstream of the nt 3585 BP, a distance reminiscent of that of the 3RE from the Ad IIIa BP. However, functional analysis of full-length or partial SE3 fragments in a heterologous nt 3225 3′ splice site-containing pre-mRNA or in Drosophila dsx pre-mRNAs showed that this is only a weak ESE (data not shown) (54). Thus, these putative binding sites are unlikely to have the same degree of repressor activity as the 3RE, which can function as a potent ESE.

In this study, we also searched for exonic cis elements that might regulate the suboptimal BPV-1 nt 3605 3′ splice site and identified a novel bipartite regulator composed of the ESE SE4 and the ESS ESS2. Functionally, SE4 is very similar to SE1 and SE2, which are essential for activation of the BPV-1 nt 3225 3′ splice site. However, SE4 differs from SE1 and SE2 in its sequence composition and the presence of an AC-rich motif. This element belongs to the ACE class of ESEs (8), whereas SE1 and SE2 belong to the purine-rich ESE class and have two ASF/SF2 binding sites each (54, 55). Interestingly, sequence analysis of SE4 indicates that there is a potential SRp40 binding site (ACDGS, where D represents residues other than C and S represents G or C) (27) immediately upstream of the AC-rich motif which was also mutated in the ACE point mutation analysis (Fig. 6, pre-mRNA 5). SE1 and SE2 have been extensively studied and feature a strong affinity for the SR proteins ASF/SF2, SRp55, and SRp75 (55). Whether SE4 functions through interaction with SR proteins remains to be elucidated. However, there are data suggesting that SR protein binding is essential for the activity of ACE enhancers (8). The BPV-1 ESS2 described in this report has several interesting features. First, it has a UGGU core suppressor motif which has not been described previously. Secondly, the suppressor core requires additional nucleotide sequences downstream for its function in vitro and does not function as a suppressor if it is positioned at the 3′ end of the pre-mRNA. This property resembles the core motif GGCUCCCCC in ESS1 (57). Whether the sequences downstream of the UGGU motif make sequence-specific contributions to ESS2 function is not clear from our study. RNA sequences 3′ to the core may stabilize the binding of splicing factors or protect the core from 3′ exoribonucleolytic digestion in vitro. In the context of an nt 3225 3′ splice site-containing pre-mRNA, these sequences had no effect on SE1-enhanced splicing (Fig. 6, pre-mRNA 8) and actually enhanced splicing of a pre-mRNA containing no other enhancers (Fig. 6, pre-mRNA 7). Thus, the UGGU repressor motif appears to be flanked by enhancers. Analysis of the sequences between nt 3691 and 3715 revealed multiple potential binding sites for SRp40 (ACDGS) and SRp55 (USCGKM, where S represents G or C, K represents U or G, and M represents A or C) (27). Interestingly, the sequences downstream of the core motif in ESS1 have also been shown to bind SR proteins (57). Thirdly, the suppressor core motif UGGU is located immediately downstream of the third ACC repeat within the AC-rich motif of SE4, but it also functions well when relocated 16 nt away from the upstream AC-rich motif (Fig. 7, pre-mRNA 5). Analysis of the secondary structure of this region predicts that the UGGU motif base pairs with the upstream sequence ACCA within the AC-rich motif. This suggests that ESS2 may function through secondary-structure-mediated interference with splicing factor binding to the upstream SE4. The involvement of RNA secondary structure in the function of an ESS has been described in the regulation of fibronectin EDA exon alternative splicing. In that system, the role of the ESS element is to maintain the proper RNA conformation, with the ESE displayed in a loop structure for optimal binding of splicing factors (31).

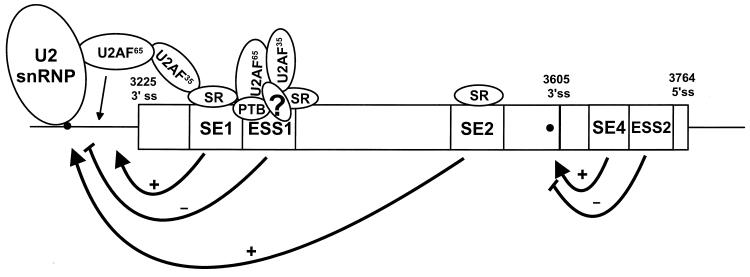

In summary, we have demonstrated that the BPV-1 late-stage-specific nt 3605 3′ splice site is a suboptimal 3′ splice site with a nonconsensus BPS and a weak PPT. We have also identified a new bipartite exonic regulatory element that controls the usage of the nt 3605 3′ splice site in vitro. This bipartite regulatory element consists of an ACE-like enhancer, SE4, and a UGGU motif-containing ESS2. While SE4 functions in pre-mRNAs with a heterologous 3′ splice site, ESS2 behaves in a splice site-specific and enhancer-specific manner. Work is in progress in our laboratory to determine how these two elements function in vivo. A model of how these elements fit into the overall regulation of BPV-1 3′ splice site selection is shown in Fig. 8. Selection of the suboptimal nt 3225 and 3605 3′ splice sites is regulated through five viral cis elements, three ESEs (SE1, SE2, and SE4) and two ESSs (ESS1 and ESS2). Although the factors binding to SE4 and ESS2 remain unknown, we believe that the ESEs stimulate splicing at both suboptimal splice sites through recruitment of splicing factors at early stages of spliceosome assembly (61). The ESSs play a negative role in the selection of two suboptimal 3′ splice sites. Cellular splicing factors, such as SR proteins, appear to play a key role in this regulation. The posttranslational modification status and overall balance of splicing factors would affect each cis element's function, and consequently, alternative splicing of the BPV-1 late pre-mRNA.

FIG. 8.

Proposed model for the function of the BPV-1 ESEs and ESSs in regulation of BPV-1 alternative splicing. 3′ ss, 3′ splice site; 5′ ss, 5′ splice site; ?, hypothetical factor(s); solid circles, BPS; +, enhances splicing; −, suppresses splicing. Arrows indicate sites at which elements function.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Goran Akusjärvi for the gift of plasmids pGDIIIa and pGDIII(−3RE).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams M D, Rudner D Z, Rio D C. Biochemistry and regulation of pre-mRNA splicing. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:331–339. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amendt B A, Hesslein D, Chang L-J, Stoltzfus C M. Presence of negative and positive cis-acting RNA splicing elements within and flanking the first tat coding exon of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3960–3970. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amendt B A, Si Z-H, Stoltzfus C M. Presence of exon splicing silencers within human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tat exon 2 and tat-rev exon 3: evidence for inhibition mediated by cellular factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4606–4615. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barksdale S K, Baker C C. Differentiation-specific alternative splicing of bovine papillomavirus late mRNAs. J Virol. 1995;69:6553–6556. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6553-6556.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caputi M, Casari G, Guenzi S, Tagliabue R, Sidoli A, Melo C A, Baralle F E. A novel bipartite splicing enhancer modulates the differential processing of the human fibronectin EDA exon. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1018–1022. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.6.1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caputi M, Mayeda A, Krainer A R, Zahler A M. hnRNP A/B proteins are required for inhibition of HIV-1 pre-mRNA splicing. EMBO J. 1999;18:4060–4067. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen C D, Kobayashi R, Helfman D M. Binding of hnRNP H to an exonic splicing silencer is involved in the regulation of alternative splicing of the rat beta-tropomyosin gene. Genes Dev. 1999;13:593–606. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.5.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coulter L R, Landree M A, Cooper T A. Identification of a new class of exonic splicing enhancers by in vivo selection. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2143–2150. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Gatto F, Breathnach R. Exon and intron sequences, respectively, repress and activate splicing of a fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 alternative exon. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4825–4834. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.4825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Del Gatto F, Gesnel M C, Breathnach R. The exon sequence TAGG can inhibit splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2017–2021. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.11.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Gatto-Konczak F, Olive M, Gesnel M C, Breathnach R. hnRNP A1 recruited to an exon in vivo can function as an exon splicing silencer. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:251–260. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang G, Weiser B, Visosky A, Moran T, Burger H. PCR-mediated recombination: a general method applied to construct chimeric infectious molecular clones of plasma-derived HIV-1 RNA. Nat Med. 1999;5:239–242. doi: 10.1038/5607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallego M E, Gattoni R, Stevenin J, Marie J, Expert-Bezancon A. The SR splicing factors ASF/SF2 and SC35 have antagonistic effects on intronic enhancer-dependent splicing of the beta-tropomyosin alternative exon 6A. EMBO J. 1997;16:1772–1784. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaur R K, Valcarcel J, Green M R. Sequential recognition of the pre-mRNA branch point by U2AF65 and a novel spliceosome-associated 28-kDa protein. RNA. 1995;1:407–417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gersappe A, Pintel D J. CA- and purine-rich elements form a novel bipartite exon enhancer which governs inclusion of the minute virus of mice NS2-specific exon in both singly and doubly spliced mRNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:364–375. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graveley B R, Hertel K J, Maniatis T. A systematic analysis of the factors that determine the strength of pre-mRNA splicing enhancers. EMBO J. 1998;17:6747–6756. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho S N, Hunt H D, Horton R M, Pullen J K, Pease L R. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodges D, Bernstein S I. Genetic and biochemical analysis of alternative RNA splicing. Adv Genet. 1994;31:207–281. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60399-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman B E, Grabowski P J. U1 snRNP targets an essential splicing factor, U2AF65, to the 3′ splice site by a network of interactions spanning the exon. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2554–2568. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang D Y, Cohen J B. Base pairing at the 5′ splice site with U1 small nuclear RNA promotes splicing of the upstream intron but may be dispensable for splicing of the downstream intron. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3012–3022. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanaar R, Roche S E, Beall E L, Green M R, Rio D C. The conserved pre-mRNA splicing factor U2AF from Drosophila: requirement for viability. Science. 1993;262:569–573. doi: 10.1126/science.7692602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanopka A, Muhlemann O, Akusjarvi G. Inhibition by SR proteins of splicing of a regulated adenovirus pre-mRNA. Nature. 1996;381:535–538. doi: 10.1038/381535a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanopka A, Muhlemann O, Petersen-Mahrt S, Estmer C, Ohrmalm C, Akusjarvi G. Regulation of adenovirus alternative RNA splicing by dephosphorylation of SR proteins. Nature. 1998;393:185–187. doi: 10.1038/30277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kreivi J-P, Zefrivitz K, Akusjärvi G. A U1 snRNA binding site improves the efficiency of in vitro pre-mRNA splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6956. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.24.6956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreivi J-P, Zerivitz K, Akusjärvi G. Sequences involved in the control of adenovirus L1 alternative RNA splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:2379–2386. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.9.2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lavigueur A, La Branche H, Kornblihtt A R, Chabot B. A splicing enhancer in the human fibronectin alternate ED1 exon interacts with SR proteins and stimulates U2 snRNP binding. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2405–2417. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12a.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu H X, Zhang M, Krainer A R. Identification of functional exonic splicing enhancer motifs recognized by individual SR proteins. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1998–2012. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maniatis T. Mechanisms of alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Science. 1991;251:33–34. doi: 10.1126/science.1824726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayeda A, Screaton G R, Chandler S D, Fu X D, Krainer A R. Substrate specificities of SR proteins in constitutive splicing are determined by their RNA recognition motifs and composite pre-mRNA exonic elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1853–1863. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore M J, Query C C, Sharp P A. Splicing of precursors to messenger RNAs by the spliceosome. In: Gestland R F, Atkins J F, editors. The RNA world. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 303–357. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muro A F, Caputi M, Pariyarath R, Pagani F, Buratti E, Baralle F E. Regulation of fibronectin EDA exon alternative splicing: possible role of RNA secondary structure for enhancer display. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2657–2671. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagel R J, Lancaster A M, Zahler A M. Specific binding of an exonic splicing enhancer by the pre-mRNA splicing factor SRp55. RNA. 1998;4:11–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norton P A. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing: factors involved in splice site selection. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:1–7. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Potashkin J, Naik K, Wentz-Hunter K. U2AF homolog required for splicing in vivo. Science. 1993;262:573–575. doi: 10.1126/science.8211184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramchatesingh J, Zahler A M, Neugebauer K M, Roth M B, Cooper T A. A subset of SR proteins activates splicing of the cardiac troponin T alternative exon by direct interactions with an exonic enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4898–4907. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.4898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharp P A. Split genes and RNA splicing. Cell. 1994;77:805–816. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Si Z, Amendt B A, Stoltzfus C M. Splicing efficiency of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tat RNA is determined by both a suboptimal 3′ splice site and a 10 nucleotide exon splicing silencer element located within tat exon 2. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:861–867. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.4.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh R, Valcarcel J, Green M R. Distinct binding specificities and functions of higher eukaryotic polypyrimidine tract-binding proteins. Science. 1995;268:1173–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.7761834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Staffa A, Acheson N H, Cochrane A. Novel exonic elements that modulate splicing of the human fibronectin EDA exon. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:33394–33401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Staffa A, Cochrane A. The tat/rev intron of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is inefficiently spliced because of suboptimal signals in the 3′ splice site. J Virol. 1994;68:3071–3079. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3071-3079.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Staffa A, Cochrane A. Identification of positive and negative splicing regulatory elements within the terminal tat-rev exon of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4597–4605. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun Q, Mayeda A, Hampson R K, Krainer A R, Rottman F M. General splicing factor SF2/ASF promotes alternative splicing by binding to an exonic splicing enhancer. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2598–2608. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanaka K, Watakabe A, Shimura Y. Polypurine sequences within a downstream exon function as a splicing enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1347–1354. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valcarcel J, Gaur R K, Singh R, Green M R. Interaction of U2AF65 RS region with pre-mRNA of branch point and promotion base pairing with U2 snRNA. Science. 1996;273:1706–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5282.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vogel J, Hess W R, Borner T. Precise branch point mapping and quantification of splicing intermediates. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2030–2031. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.10.2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watakabe A, Tanaka K, Shimura Y. The role of exon sequences in splice site selection. Genes Dev. 1993;7:407–418. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wentz M P, Moore B E, Cloyd M W, Berget S M, Donehower L A. A naturally arising mutation of a potential silencer of exon splicing in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 induces dominant aberrant splicing and arrests virus production. J Virol. 1997;71:8542–8551. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8542-8551.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Will C L, Luhrmann R. Protein functions in pre-mRNA splicing. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:320–328. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu J, Manley J L. Mammalian pre-mRNA branch site selection by U2 snRNP involves base pairing. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1553–1561. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.10.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu S, Romfo C M, Nilsen T W, Green M R. Functional recognition of the 3′ splice site AG by the splicing factor U2AF35. Nature. 1999;402:832–835. doi: 10.1038/45590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zamore P D, Green M R. Identification, purification, and biochemical characterization of U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein auxiliary factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9243–9247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zamore P D, Patton J G, Green M R. Cloning and domain structure of the mammalian splicing factor U2AF. Nature. 1992;355:609–614. doi: 10.1038/355609a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng Z M, Baker C C. Parameters that affect in vitro splicing of bovine papillomavirus type 1 late pre-mRNAs. J Virol Methods. 2000;85:203–214. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(99)00172-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zheng Z M, He P J, Baker C C. Selection of the bovine papillomavirus type 1 nucleotide 3225 3′ splice site is regulated through an exonic splicing enhancer and its juxtaposed exonic splicing suppressor. J Virol. 1996;70:4691–4699. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4691-4699.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng Z M, He P J, Baker C C. Structural, functional, and protein binding analyses of bovine papillomavirus type 1 exonic splicing enhancers. J Virol. 1997;71:9096–9107. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9096-9107.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zheng Z M, He P J, Baker C C. Function of a bovine papillomavirus type 1 exonic splicing suppressor requires a suboptimal upstream 3′ splice site. J Virol. 1999;73:29–36. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.29-36.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng Z M, Huynen M, Baker C C. A pyrimidine-rich exonic splicing suppressor binds multiple RNA splicing factors and inhibits spliceosome assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14088–14093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zheng Z M, Quintero J, Reid E S, Gocke C, Baker C C. Optimization of a weak 3′ splice site counteracts the function of a bovine papillomavirus type 1 exonic splicing suppressor in vitro and in vivo. J Virol. 2000;74:5902–5910. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.5902-5910.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhuang Y, Weiner A M. A compensatory base change in human U2 snRNA can suppress a branch site mutation. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1545–1552. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.10.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zorio D A, Blumenthal T. Both subunits of U2AF recognize the 3′ splice site in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1999;402:835–838. doi: 10.1038/45597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zuo P, Maniatis T. The splicing factor U2AF35 mediates critical protein-protein interactions in constitutive and enhancer-dependent splicing. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1356–1368. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]