Abstract

Background

Hyaluronic acids (HAs) continue to be the fillers of choice worldwide and their popularity is growing. Adverse events (AEs) are able to be resolved through the use of hyaluronidase (HYAL). However, routine HYAL use has been at issue due to perceived safety issues.

Objectives

There are currently no guidelines on the use of HYAL in aesthetic practice, leading to variability in storage, preparation, skin testing, and beliefs concerning AEs. This manuscript interrogated the use of this agent in daily practice.

Methods

A 39-question survey concerning HYAL practice was completed by 264 healthcare practitioners: 244 from interrogated databases and 20 from the consensus panel. Answers from those in the database were compared to those of the consensus panel.

Results

Compared to the database group, the consensus group was more confident in the preparation of HYAL, kept reconstituted HYAL for longer, and was less likely to skin test for HYAL sensitivity and more likely to treat with HYAL in an emergency, even in those with a wasp or bee sting anaphylactic history. Ninety-two percent of all respondents had never observed an acute reaction to HYAL. Just over 1% of respondents had ever observed anaphylaxis. Five percent of practitioners reported longer-term adverse effects, including 3 respondents who reported loss of deep tissues. Consent before injecting HA for the possible requirement of HYAL was always obtained by 74% of practitioners.

Conclusions

Hyaluronidase would appear to be an essential agent for anyone injecting hyaluronic acid filler. However, there is an absence of evidence-based recommendations with respect to the concentration, dosing, and treatment intervals of HYAL, and these should ideally be available.

Level of Evidence: 5

With the growing popularity and administration of hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers, there is likely to be a concomitant growth in filler-related complications and the utilization of hyaluronidase (HYAL) in its role of dissolving HA fillers. Filler-related complications involve unaesthetic results or reactions to the filler such as hypersensitivity, infection, nodule formation, or vascular adverse events.

There are 6 known types of native hyaluronidase. HYAL 1 to 4, PH-20, and HYALP1. HYAL-1 and HYAL-2 are the major hyaluronidases in most tissues (Table 1).1

Table 1.

Types of Endogenous Hyaluronidase, Location, and Function

| Type | Location | Main Role | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HYAL 1 | Liver, kidney, spleen, heart, serum, urine | Intracellular breakdown and hepatic clearance of low MW HA | Intracellular |

| HYAL 2 | Initial breakdown of high MW hyaluranon | Extracellular | |

| HYAL 3 | Testis, bone marrow | Unknown | Limited role |

| HYAL 4 | Placenta, muscle, stem cells | Action on cartilage—also called chondroitin sulphate hydrolase | Limited role |

| PH-20 | Sperm | Fertilization | Fertilization only |

| HYALP-1 | Pseudogene that is not transcribed | Limited role |

HA, hyaluronic acid; MW, molecular weight.

There are several common commercial HYAL products available worldwide, including Hyalase (Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty. Ltd., Macquarie Park, NSW, Australia and Wockhardt UK, Wrexham, UK); Hylenex (Halozyme Therapeutics, Inc., San Diego, CA); Vitrase (Bausch & Lomb Incorporated, Bridgewater, NJ); Hylase Dessau, (RIEMSER Pharma GmbH, Greifswald, Germany); Amphadase (Amphastar Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Rancho Cucamonga, CA); Liporase (Daehan New Pharm Co., Ltd., Hwaseong-si, South Korea); and Hirax (BMI Korea, Uiwamg, South Korea). None of the products are licensed for dissolving injected HA fillers, and there is an absence of guidelines for their use (Table 2).2-4

Table 2.

Common Commercially Available Hyaluronidase Preparations

| Brand name | Country | Manufacturer | Origin | Type | Vial Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyalase | Australia New Zealand |

Sanofi-Aventis | Ovine | Testicular PH-20 | 1500 IU powder |

| Hyalase | UK | Wockhardt | Ovine2 | Testicular PH-20 | 1500 IU powder |

| Vitrase | USA | Bausch & Lomb Incorporated | Ovine | Testicular PH-20 | 200 USP liquid |

| Hylase Dessau | Germany | RIEMSER Pharma GmbH | Bovine3 | Testicular PH-20 | 150 IE powder |

| Amphadase | USA | Amphastar Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | Bovine4 | Testicular PH-20 | 150 USP liquid |

| Liporase | Korea | Daehan New Pharm Co., Ltd. | Bovine | Testicular PH-20 | 1500 IU powder |

| Hirax | Korea | BMI Korea | Bovine | Testicular PH-20 | 1500 IU liquid |

| Hylenex | USA | Halozyme Therapeutics, Inc. | Synthetic recombinant human DNA in hamster ovary cells | Testicular PH-20 | 150 USP liquid |

Note: Wydase, Hydase, and Hyalozima (Brazil) are discontinued.

The aim of this paper was to gain insights into the use of HYAL in aesthetic practice. To that end, a consensus group of expert injectors outlined their practice regarding both elective and emergency use of HYAL. These expert practices were then compared to practitioner habits and usage with survey questions addressed to a broader group with professional backgrounds, predominantly from Australia. Key topics covered included HYAL usage, habits, and perceptions around safety, as well as other practices.

None of the consensus group had a conflict of interest to declare with the content of this manuscript.

METHODS

Roundtable

A multidisciplinary panel of 20 experienced aesthetic practitioners was convened as a consensus group to discuss administration of hyaluronidase within aesthetic medicine for the treatment of adverse events at the Australasian Society of Cosmetic Dermatology (ASCD) meeting held in February 2022. This group comprised 4 dermatologists, 3 plastic surgeons, 7 aesthetic physicians, 3 nurses, 1 nurse practitioner, 1 ophthalmologist, and 1 dentist.

From this meeting came the concept of conducting a survey to develop an understanding of the beliefs and knowledge of cosmetic practitioners, and to compare these results with those of the consensus group. These questions were framed by the consensus group and refined through a Delphi process to achieve the final set of consensus questions (Appendix, available online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com).

Survey Methodology

To capture practitioner HYAL usage habits across a variety of professional backgrounds, a 39-question survey containing both open and closed questions was drafted, refined by consensus group members, and then sent to 3331 practitioners with a range of backgrounds and experience levels (specialist medical practitioners, general practitioners, nurse practitioners, and nurses). The survey was sent to practitioners in the databases of the ASCD, the Cosmetic Physicians College of Australia (CPCA), Cosmetic Nurses of Australia (can), and the Aesthetic Medical Emergency Team (AMET) and also shared on social media platforms dedicated to aesthetic healthcare professionals. In total, 264 practitioners completed the survey (244 from these databases and 20 consensus group members).

Answers from the consensus group (n = 20), were compared with those from the broader survey group: areas of broad agreement and those in which there seemed to be response variation are detailed in the results and discussion that follow.

We also conducted a subgroup analysis of specialist plastic surgeons and dermatologists (n = 30) for comparison with the nonspecialist respondents (n = 233). Survey questions were constructed to capture information about practitioner experience and usage (Table 3) and their confidence level and habits (Table 4). The questionnaire responses were anonymous, and the survey was constructed and distributed with MailChimp.

Table 3.

Practitioner Demographics, Experience, and Safety Readiness Questions

| Survey questions regarding practitioner experience and usage |

| Demographics: |

| Location, qualification/professional title, experience level (aesthetics) |

| Aesthetic injectable treatments performed |

| Volume of HA filler administered per week |

| Filler adverse events |

| Practitioner experience with vascular occlusion, delayed onset nodules, and elective dissolution of HA |

| Practitioner safety prevention readiness such as adrenaline (epinephrine) and stock level of hyaluronidase in units on site |

HA, hyaluronic acid.

Table 4.

Issues Regarding Practitioner Confidence and Habits

| Survey questions regarding confidence level and habits |

| Practitioner hyaluronidase practice and knowledge: |

| Type and source of hyaluronidase (ovine, bovine, human recombinant) |

| Confidence regarding hyaluronidase |

| Lidocaine addition to hyaluronidase |

| Concentration for vascular occlusion, delayed onset nodules, and elective dissolution |

| Skin testing |

| Allergic reaction: practitioner experience |

| Level of fear surrounding cross-reactivity and allergy rates with bee or wasp allergy |

| Storage |

| Administration for adverse effects |

RESULTS

HYAL Survey Data

Demographics of Respondents

A total of 264 invitees responded to the survey. Eighty-six percent of respondents resided in Australia, 6% were from New Zealand, and 8% came from a range of other countries.

Just over half of respondents were injecting nurses (52.7%). General medical practitioners accounted for 21.6%. Dermatologists, prescribing nurse practitioners, and plastic surgeons each contributed approximately 5% of responses. Eighty-two percent of respondents had at least 5 years of experience in aesthetic medicine, with 55% having over 10 years’ experience. Of relevance, nearly all (99.2%) of respondents reported routinely injecting HA fillers, with 37% administering over 15 syringes per week. The consensus group was more experienced, with 95% of the consensus group having over 10 years of injection experience and 55% administering over 15 syringes a week.

Safety Considerations

Respondents were asked which agents they kept on hand in case of emergency. Ninety-six percent stocked adrenaline (epinephrine) and over 99% stocked HYAL. Regarding understanding of HYAL characteristics, usage, and adverse reactions, 93% of participants felt confident providing this agent. Most respondents employed ovine (sheep) sourced hyaluronidase (85%); however, 11% were unsure of the source. All consensus group members kept HYAL on site.

Storage

Approximately equal numbers stored their HYAL at 4°C (45%) and at room temperature (47%). In Australia and New Zealand, most HYAL comes in a powder form that needs to be reconstituted with saline before administration. Even though almost all respondents and all consensus group members kept HYAL on site, only 33% always (and 13% sometimes) stored reconstituted HYAL for emergency use. One percent of respondents had HYAL in pre-reconstituted form.

Respondents who did not have reconstituted HYAL commercially available were very confident (69%) or somewhat confident (25%) in their ability to reconstitute hyaluronidase. The consensus group were very confident (85%) or somewhat confident (10%) in their ability to reconstitute HYAL. Only 26% reported discarding HYAL within 24 hours of dilution, 29% reported keeping reconstituted hyaluronidase for 2 weeks or less, and 33% reported keeping diluted HYAL for 2 to 4 weeks. In the consensus group 55% kept the reconstituted hyaluronidase for up to 4 weeks and 30% for up to 2 weeks.

Skin Testing and Patient History

Overall, a slightly higher percentage of respondents stated they had never skin tested with HYAL before administration (29%), compared to 25% who stated that they always did a skin test before use (Figure 1). A total of 38% of participants stated that they sometimes skin tested if the patient had a history suggesting allergy may be more likely. The consensus group was less inclined to perform skin tests before providing HYAL, with 20% of the consensus group sometimes performing skin tests, vs 65% of the database. No member of the consensus group “always” performed skin tests, vs 26% of the database who always did.

Figure 1.

Comparison of consensus members and general respondents regarding skin testing before hyaluronidase treatment. Sixty-five percent of external practitioners would perform a skin test, vs 20% of the consensus practitioners. HCP, healthcare practitioner.

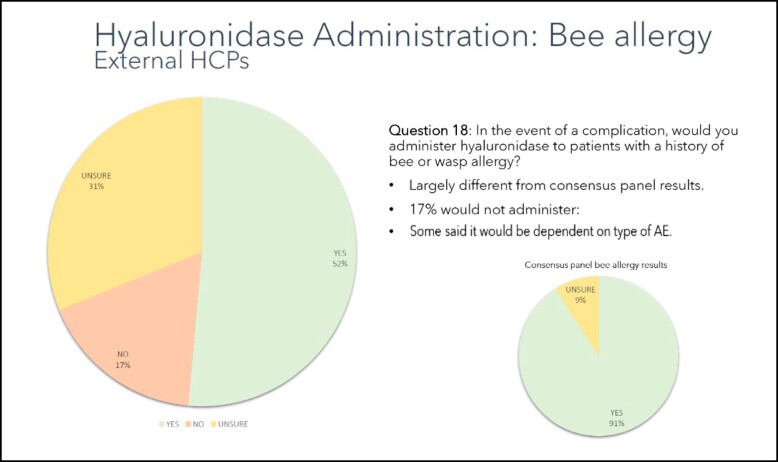

For patients with a past history of bee or wasp sting allergy, over half of respondents (54%) indicated that they would be willing to inject HYAL in case of an emergency, with 29% reporting that they were unsure and 16% reporting that they would not. In the consensus group respondents were much more likely (91%) to inject HYAL (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Willingness to treat patients with bee sting allergies with HYAL. Ninety-one percent of the consensus group would administer hyaluronidase to those with bee or wasp sting allergy, vs only 52% of the external practitioners. HCP, healthcare practitioner.

Hyaluronidase Reactions

When asked a series of questions about reaction to HYAL usage, 92% of respondents had not observed an acute reaction (within 60 minutes of injection), while 8% stated that they had seen a reaction severe enough to require medical intervention (Figure 3). Of those reactions that required medical intervention, only just over 1% (3/264) of respondents had seen anaphylaxis occur, while less than 7% (18/264) had observed angioedema (9) or severe swelling (9). Of those respondents who reported having observed at least 1 reaction requiring medical intervention, only 1 case of localized angioedema and swelling progressed to anaphylaxis and required epinephrine. All other reported reactions did not interfere with daily living. Of note, the initial dose of HYAL reported for all cases in which acute reactions were observed was quite low, with less than 500 U injected in over 70% of cases.

Figure 3.

Percentage of respondents reporting acute reactions to HYAL. Ninety-two percent of respondents had not visualized an adverse acute reaction to HYAL, whereas 8% did to varying degrees.

Longer-term Effects of HYAL

Participants were asked about whether they had observed long-term effects following the administration of HYAL. Overall, 95% had never observed long-term effects following HYAL, while 5% reported longer-term adverse reactions, including delayed swelling (2 cases), urticaria (1 case), and other skin rashes (2 cases). Destruction of deep tissues was cited by 3 respondents (1%). One clinician in the consensus group reported long-term loss or change in elasticity, whereas the rest of the group had seen no persistent effects from hyaluronidase use. There was no questioning of the reason for giving HYAL and whether the destruction may have been due to issues such as ischemia-induced tissue loss rather than due directly to the HYAL.

Management of Emergencies

Vascular Occlusion

Close to 60% of respondents had managed vascular occlusion with HYAL, with over 20% having managed at least 4 cases. The most common concentration of HYAL in this setting was 500 to 750 IU/ml (35%), followed by 300 to 375 IU/ml (24%), 150 to 250 IU/ml (23%), and 1500 IU/ml (15%). Frequency of HYAL in this setting included hourly injection (36%), every 30 to 45 minutes (26%), every 15 minutes (33%), and daily (6%). Most respondents reported having no maximum dose (73%; continuing until blood flow was restored), 11% reported a 3000 U maximum, 11% reported a 7500 U maximum, and 5% reported a 15,000 U upper limit. More practitioners employed a needle as their instrument for HYAL delivery (57%), with most of the others utilizing both cannulae and needles (42%) and less than 1% cannulae alone. In the consensus group, 3 members (15%) had not managed an intravascular event. Of the remainder 4 (20%) had handled 1 to 3 events, 7 (35%) between 4 to 10, and 6 (30%) over 30 events. The most common concentration administered was 500 to 750 IU/ml (9/20, 45%) and their most common injection interval was 30 to 45 minutes (11/20, 55%). Similar to the broad group, most consensus members (16/20, 80%) had no upper limit for HYAL injection, and all employed a mixture of needles and cannulae or needles alone. No consensus members performed the procedure with cannulae alone.

Delayed Nodules

Respondents were asked how many delayed nodules they had directly managed or treated. A total of 72% of respondents had managed a delayed inflammatory nodule, with 33% having treated 1 to 3 nodules, 17% between 4 and 10 nodules, and 12% more than 10. The HYAL concentration in this setting was most commonly 150 to 250 IU/ml (37%), followed by 300 to 375 IU/ml (20%), 500 IU/ml (15%), 750 IU/ml (8%) and 1500 IU/ml (9%). The most popular dose for treating nodules was considerably lower than the most popular dose (500-750 IU/ml) chosen for treating vascular occlusion. Delayed inflammatory nodules were most commonly treated at 1- to 2-week intervals (56%) or 24- to 48-hour intervals (34%).

In the consensus group 17/20 (85%) had managed a delayed inflammatory nodule, with 9/20 (36%) between 4 and 10 nodules, 4/20 (20%) between 10 to 29, and 4/10 (20%) more than 30. The HYAL concentration in this setting was widely split, with 5/20 giving doses of 150 to 250 us/ml, 500 us/ml, and 1500 us/ml. Delayed inflammatory nodules were most commonly treated at 1- to 2-week intervals (17/20, 85%).

Elective Treatment

For elective treatment of “overfilled” patients or dissolving misplaced material, both respondents and the consensus group reported administering a lower HYAL concentration, and the most commonly reported treatment interval was 1 to 2 weeks (71%).

Consent Issues

Respondents were asked whether they obtained consent from patients before treatment with HA fillers for the emergency use of HYAL if needed. A total of 74% obtained consent before treatment, 19% did not, and the remainder did sometimes. Eighty-two percent of respondents reported discussing these issues with their patients, with a small percentage sometimes discussing HYAL (3%), and 5% not discussing HYAL with their patients.

Obtaining consent was more widely practiced in the consensus group. Two practitioners did not obtain consent, 16/20 (80%) always did, and 2/20 (10%) sometimes did.

The subgroup of specialists had fewer differences from the nonspecialists than might be expected. The specialists kept fewer units of hyaluronidase (1500-6000) than nonspecialists (7500-13,500). Most specialists kept hyaluronidase refrigerated, with administration within 24 hours, while nonspecialists were more likely to keep their hyaluronidase at room temperature and keep it for up to 4 weeks. More importantly, the specialist group largely responded “never” to the question about skin testing, vs the nonspecialists, who mostly answered “sometimes.”

DISCUSSION

The antigenicity of hyaluronidase was explored. Hyaluronidases are glycoproteins and can act as an antigen and induce an immune response. This is due in part to their epitopes, which are part of the protein's molecular surface and are recognized by specific antibodies. The antigenicity of HYAL and the understanding of immunological cross-reactions is determined by the epitope structure and may elicit CD4+ T-cell reactions when activated by varying types of hyaluronidases.5,6

HYAL can provoke a hypersensitivity-like response such as swelling and erythema, although skin allergy tests remain negative. This type of reaction indicates a Type A adverse drug reaction, a predictable nonallergic reaction that occurs by virtue of the pharmacology of the drug. Type B drug reactions are allergic and are not predictable responses to the pharmacological actions of the drug.3,7,8 Rare cases of hypersensitivity to HYAL have been described since 1984, with a reported incidence of 0.05% to 0.69%; urticaria and angioedema symptoms are reported to occur in approximately 0.1%.2,4,9 Most reported cases of hypersensitivity to HYAL are acute or delayed reactions in the ophthalmic and anesthetic literature, after receiving animal-derived HYAL.8,10 There are few reports of HYAL-related allergic reactions in the dermatologic literature.11,12 However, with the increased use of HYAL in cosmetic medicine the incidence may currently be underreported. The incidence of allergic reaction and anaphylaxis reporting is very low, except in high-dose IV HYAL doses exceeding 200,000 IU. If a Type I reaction occurs the rate increases to 33%.7,13

Case reports on HYAL hypersensitivity in the literature indicate that immediate Type I (IgE) and or delayed Type IV (T-cell mediated) reactions are the most common. Type I hypersensitivity symptoms are usually mild and include soft tissue angioedema, localized swelling, pruritis, and erythema where the antigen has been injected.2,14-16 The incidence of hypersensitivity and allergy, including anaphylaxis, is more commonly associated with animal-derived and compounded products. There are currently no reports of an allergic immunogenic hypersensitivity reaction with human recombinant hyaluronidase rHuPH20 Hylenex, which is well tolerated.2,7,11,17

There is usually no link between a patient's history of allergies and the risk of an allergic response to HYAL. However, allergy to bee or wasp venom, part of the Hymenoptera family, increases the likelihood of allergy to HYAL and poses a significant risk of cross-reactivity with injection. The literature reports of allergy are almost exclusively linked to previous exposure to HYAL or bee or wasp venom.18 Once exposed, an individual becomes sensitized. Primary sensitization appears to be a prerequisite for such an allergic response due to the variability of the onset of symptoms, and suggests that both Type I and Type IV hypersensitivity reactions may contribute to this response.2,19 Repeated HYAL injection in an individual will allow for a greater degree of sensitization and therefore increase the risk of a hypersensitivity reaction.18,20 Additionally, a history of atopy or asthma, irrespective of allergy to Hymenoptera, has also been shown to increase the risk of hypersensitivity to HYAL.17

The presence of proteins, compounding Impurities, preservatives, or additives also may cause reactions and make it difficult to determine the direct cause of allergy when HYAL is injected. For example, bacteriostatic saline, often utilized to reconstitute HYAL, is preserved with benzyl alcohol. Benzyl alcohol has a known rate of 1.3% Type IV hypersensitivity reaction, which is considerably higher than the overall incidence of hypersensitivity to HYAL.16,18,21 Toxicity is rare. HYAL at concentrations greater than 1:10 (1500:10 mL) can be an irritant to the tissues, and localized irritation would present commonly as erythema, pain, swelling, and itching, which also may be confused with an IgE hypersensitivity.16

It has been 20 years since the first soft tissue HA fillers were approved in the United States, and 25 years in Australia and New Zealand. Sophisticated manufacturing techniques have provided aesthetic practitioners with biocompatible and effective soft tissue implants. Their favorable safety profile and the minimally invasive placement has contributed significantly to their popularity. Additionally, they can be administered by a range of practitioners, from nurses to dentists and doctors.

Integral to safety is the ready availability of commercial HYAL enzyme preparations that can break down HA in the event of misplacement, nodule formation, or vascular occlusion. Although this product has been administered in surgery and ophthalmology for many years, there are no clear guidelines yet available for HYAL in aesthetic practice, and it remains off-label for this indication. This has led to a situation in which variable practices are common, but the extent of variability in the community was incompletely understood. This study aimed to help clarify community variability, with the longer-term goal of providing best practice recommendations.

It is clear from the results of this survey of experienced Australian and New Zealand aesthetic injectors (50% of whom were nurses) that there remains significant variability in the administration of HYAL. Although 99.2% had it on site in case of emergency and 93% felt confident administering this agent, there was wide diversity in practice around storage, handling, and administration, particularly in the event of a bee or wasp allergy or another adverse event.

Key Survey Findings and Issues Requiring Future Clarification

Storage and preparation were interrogated. Ovine hyaluronidase (Hyalase Sanofi) is available in Australia and was most commonly administered by this group (86%). This product comes as freeze-dried powder with manufacturer data sheet instructions for it to be stored at less than 25°C before being reconstituted and then immediately discarded after use. Approximately half of our respondents stored the agent in a refrigerator, with a similar number storing it in reconstituted form, ready for and emergency. When stored reconstituted, only 26% discarded it within 24 hours, and the rest stored it in the refrigerator for up to a month.

All consensus group members kept HYAL on site, and 70% of the consensus group kept their reconstituted HYAL in the refrigerator at 4°C.

Issues raised included the following. All clinics should store HYAL on site for emergency, but clear guidelines are absent in the literature with respect to HYAL storage once reconstituted. There appear to be no data to support the storage of reconstituted HYAL, either at room temperature or in the refrigerator. The manufacturer's data sheet suggests storing the unreconstituted product at temperatures of less than 25°C, but once the ampule is opened the manufacturer recommends immediate use. Any leftover product is to be discarded. This is not common practice for HYAL in the context of tissue HA fillers. More data than that provided by the current product information is clearly needed to guide correct storage of HYAL. It has been suggested that 7500 IU of HYAL should be kept on site by injecting practitioners.22

The consensus group were concerned about the rate of skin testing. Of concern was the incidence of skin testing in a setting where there was a low sensitivity rate, combined with a lack of understanding of the reading and implications of a skin test result. Of the general respondents, over 70% sometimes or always skin tested before administration. This was particularly concerning in an emergency setting, in which skin testing and its interpretation would likely result in a negative patient outcome.

The consensus group were significantly less inclined than the general population group to perform skin tests before HYAL (Figure 2); this was in line with the British Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI), which states that skin tests should not be done to screen for drug allergy in the absence of a clinical history of a Type 1 hypersensitivity. Where there is a clinical history of drug allergy, skin testing is recommended in specialist allergy centers only. In addition, there is no validated test concentration of HYAL. The information available is based mainly on case studies, which suggest dosages of between 15 and 30 units. However, the reports are inconsistent, and in many the findings may be explained by local skin irritation caused by the enzyme rather than a Type IV reaction. Therefore, HYAL skin testing currently performed by aesthetic practitioners is neither reliable nor valid and could result in anaphylaxis if performed in patients with a history of anaphylaxis to bee or wasp stings (ideally, one should not perform a skin test in a patient with a possible history of anaphylaxis to HYAL or a wasp or bee allergy).16 Experience was also a determinant in performance of a skin test, with more experienced practitioners less likely to perform a skin test (Figures 3, 4).

Figure 4.

Years of experience in injection plotted against tendency to perform prospective skin testing indicates a much lower likelihood with greater experience. Fifty percent of those with 2 to 4 years’ experience would always perform such tests, vs 12% of those with experience of 10 years and above.

Issues raised included the following. Should skin tests ever be performed? If a patient has a history of anaphylaxis due to a wasp or bee allergy is it better not to treat with fillers at all? If in doubt, is it preferable to send this patient to an allergy center for skin testing?

The consensus group inquired into the likely behavior of the group when faced with an emergency situation requiring hyaluronidase in a patient with a known bee or wasp sting allergy. A small majority of the general group (54%) was willing to inject in an emergency in the presence of a history of known bee or wasp allergy. The remainder expressed uncertainty or refusal.

The consensus group was much more willing to inject hyaluronidase for a complication in a patient with a bee or wasp sting allergy. Allergy to these stings may take the form of a large localized reaction (LLR) or an anaphylactic reaction. An LLR involves pain, swelling, and erythema of the skin and subcutaneous tissue surrounding the sting; the risk of anaphylaxis from a subsequent sting is greater than 5%. If the patient has had a previous anaphylactic reaction to a bee or wasp sting, then the risk of anaphylaxis to a subsequent sting is at least 60%.20 The decision to give HYAL in a patient with bee or wasp allergy should depend on the severity of the complication and the severity of the patient's allergic reactions. Another factor to consider is the practitioner's ability to manage anaphylaxis, as well as the availability of appropriate facilities to manage anaphylaxis.

Issues raised included the following. Should a practitioner inject a patient with a previous severe reaction to bees or wasps with HA? If a patient has a severe vascular occlusion, a visual or cerebral embolization, should the practitioner be sufficiently skilled to begin treatment with HYAL? If treatment is provided, should the practitioner have adrenaline (epinephrine) on hand and know how to use it?

The consensus group investigated hyaluronidase use in the event of complications. Reconstitution concentrations for managing vascular occlusions varied considerably for most respondents, ranging between 300 to 750 IU/ml, with a minority (15%) giving 1500 IU/ml. The majority re-treated at 15- to 60-minute intervals, with no maximum dose, until blood flow was restored. Nearly 30%, however, indicated they would only treat up to a maximum dose. Twenty percent of the consensus group set themselves an upper limit, and 55% injected at 30- to 45-minute intervals for a vascular occlusion. The disparity in responses indicated a further need for clarity regarding HYAL emergency use.

Respondents varied also in their treatment of nodules with HYAL. Most had managed or treated nodules, but there were significant differences in the concentrations of HYAL given. However, in general lower doses of HYAL were employed than those given for the treatment of vascular occlusion.

The consensus group demonstrated no substantial difference in their approach, and tended to treat more nodules.

Issues raised included the following. Guidance would be helpful regarding the optimal intervals between repeat treatment sessions and optimal dosing for nodules and for vascular occlusion. With elective treatment, most chose a lower concentration than that administered for other HYAL indications.

Regarding consent for HYAL administration before the initial HA injection, most respondents (74%) required patients to consent to the possible requirement for HYAL and discussed the possible adverse reactions to that agent.

Issues raised included the following. In Australia, this is now mandated in the consenting process, even though HYAL for aesthetic use is still not approved by the regulatory authority.

Limitations

Limitations of this study included the low response rate to the survey. This was to some extent inevitable because it was driven only by emails to databases of organizations. There was also difficulty equating HYAL treatment dosing with the exact nature and make of hyaluronic acid employed. The study also relied on respondents’ memory of events and their ability to classify the severity of and treatment doses for these events.

We believe that this study adds to the available literature by highlighting the actual use of hyaluronidase in practitioners’ daily practice. We have focused on HYAL clinical practices and understandings of HYAL and its antigenicity, such as the need for skin testing, which may be inaccurate. We compared usage, dosage, and emergency management in the consensus group with the broader, possibly less experienced, group participants. Future research should be directed to providing evidence for best use of this agent, addressing concerns regarding its antigenicity, storage, and utilization in emergency situations.

Further limitations related to the questions asked in the initial survey. There was no question asking whether nurses were administering injections under supervision; this may be significant to address in future research. In Australia, all injecting nurses are directed by a prescribing doctor, but it is unclear how direct this supervision is. We also asked whether the respondents had seen tissue loss as a result of HYAL, but did not follow up with questions about what condition was being treated. Tissue loss in these respondents secondary to ischemic loss of tissue rather than HYAL-induced tissue loss cannot be excluded.

CONCLUSIONS

There is a need for evidence-based guidelines on the storage and dosing for different indications, because practitioner habits varied significantly. Concerns around allergy to HYAL appear to be overstated, considering its rarity and that it may be leading to unusual practices. Skin testing, if ever required, would be best addressed in specialist allergy clinics rather than in the injecting clinic. Although HYAL has a low rate of allergenicity and a very low rate of severe allergy, there is a belief that it is more allergenic than it is. Severe (albeit rare) reactions were reported only with animal-derived HYAL, rather than the human recombinant option. The risk of severe reaction increases with a history of bee or wasp anaphylaxis; however, practitioners are divided on the utility of skin tests as a screening tool. This prospective screening appears at odds with normal practice for medical treatments and suggests a further education requirement for practitioners. Certainly, it is not desirable that a positive skin test or a history of bee or wasp sting severe allergy should delay remedial emergency use of HYAL such as in an intravascular event. Hesitancy to deliver treatment is apparent in this survey, demonstrating an unfortunate and dangerous interpretation of the science.

Supplemental Material

This article contains supplemental material located online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com.

Supplementary Material

Disclosures

Ms Currie has received speaker fees from Allergan Japan Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) and Health Cert (Singapore), is a speaker for and founder of Aesthetic MET (Melbourne, Australia), and is a clinical trainer contractor for Galderma, Inc. (Lausanne, Switzerland). She has received support to attend meetings, participate in data safety monitoring, and has a leadership role in and participates on a data safety monitoring board/advisory board for Aesthetic MET. Ms Granata has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speaker's bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Allergan Japan, EnVogue Skin (Sydney, Australia) (sales, clinical education and training), Mint (Hansbiomed, Seoul, South Korea), Vivacy (Paris, France), and PDO threads (Sydney, Australia); is cofounder of and speaker for Aesthetic MET; and is a former regional sales manager for Galderma pharmaceuticals. She has also received financial support for conference attendance from EnVogue, Vivacy, and Aesthetic MET. Dr Goodman has received consulting fees from Caliway Biopharmaceuticals Co., Ltd. (New Taipei City, Taiwan); fees for lectures and presentations from Allergan Inc. (Irvine, CA), and Cutera lasers (Brisbane, CA); support for attending meetings from IBSA Pharmaceuticals (Parsippany, NJ); has a leadership position as President of the Australasian Society of Cosmetic Dermatology (ASCD); and has received equipment from Alma Lasers (Tel Aviv, Israel) and Lutronic lasers (Goyang-si, South Korea). He has been on advisory boards for IBSA, Galderma, Allergan, and Caliway. Ms Wallace has received consulting fees from Merz (Merz Pharma GmbH & Co. KGaA, Frankfurt, Germany). Dr Hart has received speaker fees from Allergan/Abbvie (Chicago, IL) and Dermosmetica (Coburg North, Australia)and has received travel support and consultancy payments and serves on advisory boards for Allergan/Abbvie. Dr Rivkin has received grants or contracts from Allergan, Merz, Galderma, and Suneva (San Diego, CA) and has received consulting fees, honoraria for lectures, presentations, speaker's bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events, support for attending meetings and/or travel from Allergan, Merz, and Galderma, and has participated on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Allergan, Merz, and Galderma. Dr Porter has received speaker fees and training stock from Allergan Aesthetics and has written medicolegal reports for Sinergy Medical Reports (Sydney, Australia). Dr Lin has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speaker's bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events and support for attending meetings and/or travel from Allergan and Merz. Dr Corduff has received consulting fees, payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speaker's bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events, support to attend educational events, and has served on advisory boards for Merz. Dr Davies has received consulting fees from Teoxane Pharmaceuticals (Geneva, Switzerland) and in his position as medical director at Silk Laser Clinics (Adelaide, Australia), Australian Laser Clinics (Queensland, Australia) and Eden Laser Clinics (Sydney, Australia). He has received speaker fees at Aesthetics 23, NSS 2022 and 2023, ASCD 2022, and ROAR 2022 and 2023 conferences. Mr Clague has received consulting fees from Hugel Aesthetics (Newport Beach, CA), Croma Pharma (Leobendorf, Austria), Cryomed (Alexandria, Australia) and Xytide Biotech (Sydney, Australia). He has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speaker's bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Alma Lasers, Galderma, Hugel, Croma, Cryomed, and Xytide Biotech. He has received support for attending meetings from Galderma, Hugel, Allergan, Croma, Cryomed, and Xytide Biotech. He has a leadership position in the Cosmetic Nurses Association as a board member. Dr Callan has received speaker fees from Allergan Aesthetics and Merz and payment for lectures at the Aesthetics 23 meeting and the CPD Institute (Cheltenham, Australia). Dr McDonald has received personal payments for lectures and presentations from Allergan Aesthetics, Galderma, IBSA, L’Oreal (Paris, France), iNova Pharmaceuticals (Chatswood, Australia), K Bridge Medical (Victoria, Australia), and Dermalogica (Carson, CA) . She has received support for attending meetings as a speaker from Allergan Aesthetics, Galderma, IBSA, L’Oreal, and K Bridge Medical and serves on advisory boards and has a leadership position for Australasian Society of Cosmetic Dermatology and the advisory board for Galderma (QM1114 Advisory board). Dr Magnusson has received payment for chairing and speaking at an educational event and received support for travel for attending meetings from Abbvie/Allergan medical aesthetics. Dr Bekhor has received consulting fees from Merz aesthetics. Dr Rudd, Dr Harris, Mr Walker, Dr Harris, Dr Tsirbas, and Dr Welsh have no conflicts of interest or disclosures to declare.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Paap MK, Silkiss RZ. The interaction between hyaluronidase and hyaluronic acid gel fillers—a review of the literature and comparative analysis. Plast Aesthet Res. 2020;7:36. doi: 10.20517/2347-9264.2020.121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murray G, Convery C, Walker L, Davies E. Guideline for the safe use of hyaluronidase in aesthetic medicine, including modified high-dose protocol. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(8):E69–E75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kaufman G. Adverse drug reactions: classification, susceptibility and reporting. Nurs Stand. 2016;30(50):53–63. doi: 10.7748/ns.2016.e10214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu L, Liu X, Jian X, et al. Delayed allergic hypersensitivity to hyaluronidase during the treatment of granulomatous hyaluronic acid reactions. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17(6):991–995. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Printz MA, Sugarman BJ, Paladini RD, et al. Risk factors, hyaluronidase expression, and clinical immunogenicity of recombinant human hyaluronidase PH20, an enzyme enabling subcutaneous drug administration. AAPS J. 2022;24(6):110. doi: 10.1208/s12248-022-00757-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Padavattan S, Schirmer T, Schmidt M, et al. Identification of a B-cell epitope of hyaluronidase, a major bee venom allergen, from its crystal structure in complex with a specific Fab. J Mol Biol. 2007;368(3):742–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yocum RC, Kennard D, Heiner LS. Assessment and implication of the allergic sensitivity to a single dose of recombinant human hyaluronidase injection: a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Infus Nurs. 2007;30(5):293–299. doi: 10.1097/01.NAN.0000292572.70387.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scolaro RJ, Crilly HM, Maycock EJ, et al. Australian and New Zealand anaesthetic allergy group perioperative anaphylaxis investigation guidelines. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2017;45(5):543–555. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1704500504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cohen BE, Bashey S, Wysong A. The use of hyaluronidase in cosmetic dermatology: a review of the literature. J Clin Investigat Dermatol. 2015;3(2):7. doi: 10.13188/2373-1044.1000018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Silverstein SM, Greenbaum S, Stern R. Hyaluronidase in ophthalmology. J Appl Res. 2012;12(1):12–13. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rindsjö E, Scheynius A. Mechanisms of IgE-mediated allergy. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316(8):1384–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.02.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Landau M. Hyaluronidase caveats in treating filler complications. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(Suppl 1):S347–S353. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Murray G, Convery C, Walker L, Davies E. Hyaluronidase guideline: pharmacology, allergy and elective use. Accessed January 14, 2023. https://aestheticdoctors.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/CMAC-Hyaluronidase-Pharmacology-Allergy-and-Elective-Use.pdf

- 14. Krishna MT, Ewan PW, Diwakar L, et al. Diagnosis and management of hymenoptera venom allergy: British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI) guidelines. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41(9):1201–1220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03788.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abbas M, Moussa M, Akel H. Type I hypersensitivity reaction. [Updated 2022 Jul 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560561/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marwa K, Kondamudi NP. Type IV hypersensitivity reaction. [Updated 2022 Aug 14]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562228/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Knowles SP, Printz MA, Kang DW, LaBarre MJ, Tannenbaum RP. Safety of recombinant human hyaluronidase PH20 for subcutaneous drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2021;18(11):1673–1685. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2021.1981286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tripp M, Ribeiro M, Kmiecik S, Go R. A “rash” decision in anesthetic management: benzyl alcohol allergy in the perioperative period. Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2021;2021:8859823. doi: 10.1155/2021/8859823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Borchard K, Puy R, Nixon R. Hyaluronidase allergy: a rare cause of periorbital inflammation. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51(1):49–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2009.00593.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bailey SH, Fagien S, Rohrich RJ. Changing role of hyaluronidase in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(2):127e–132e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a4c282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martins MS, Ferreira MS, Almeida IF, Sousa E. Occurrence of allergens in cosmetics for sensitive skin. Cosmetics. 2022;9(2):32. doi: 10.3390/cosmetics9020032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goodman GJ, Magnusson MR, Callan P, et al. A consensus on minimizing the risk of hyaluronic acid embolic visual loss and suggestions for immediate bedside management. Aesthet Surg J. 2020;40(9):1009–1021. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjz312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.