Abstract

Background

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza are both typically seasonal diseases, with winter peaks in temperate climates. Coadministration of an RSV vaccine and influenza vaccine could be a benefit, requiring 1 rather than 2 visits to a healthcare provider for individuals receiving both vaccines.

Methods

The primary immunogenicity objective of this phase 3, 1:1 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in healthy adults aged ≥65 years in Australia was to demonstrate noninferiority of immune responses with coadministration of the stabilized RSV prefusion F protein–based vaccine (RSVpreF) and seasonal inactivated influenza vaccine (SIIV) versus SIIV or RSVpreF administered alone, using a 1.5-fold noninferiority margin (lower bound 95% confidence interval >.667). Safety and tolerability were evaluated by collecting reactogenicity and adverse event data.

Results

Of 1403 participants randomized, 1399 received vaccinations (median age, 70; range, 65‒91 years). Local reactions and systemic events were mostly mild or moderate when RSVpreF was coadministered with SIIV or administered alone. No vaccine-related serious adverse events were reported. Geometric mean ratios were 0.86 for RSV-A and 0.85 for RSV-B neutralizing titers at 1 month after RSVpreF administration and 0.77 to 0.90 for strain-specific hemagglutination inhibition assay titers at 1 month after SIIV. All comparisons achieved the prespecified 1.5-fold noninferiority margin.

Conclusions

The primary study objectives were met, demonstrating noninferiority of RSVpreF and SIIV immune responses when RSVpreF was coadministered with SIIV and that RSVpreF had an acceptable safety and tolerability profile when coadministered with SIIV. The results of this study support coadministration of RSVpreF and SIIV in an older-adult population.

Clinical Trials Registration

Keywords: respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, RSVpreF, seasonal inactivated influenza vaccine, coadministration

Coadministration of a respiratory syncytial virus vaccine, RSVpreF, with seasonal inactivated influenza vaccine in adults ≥65 years old resulted in immune responses to both vaccines noninferior to those when administered alone and no clinically significant tolerability or safety issues.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a major cause of lower respiratory illness in people of all ages and can cause severe illness in infants and older adults [1]. In temperate climates, RSV infection typically follows a seasonal pattern, resulting in annual wintertime epidemics [2], although, during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the RSV season was disrupted with interseasonal epidemics observed [3, 4].

Adults aged 65 years and older and those who have chronic heart or lung conditions or are immunocompromised have an increased risk of serious RSV infection [5]. The estimated disease burden among adults aged 60 years and older in high-income countries and regions (ie, the United States, Canada, Europe, Japan, and South Korea) in 2019 was more than 5 million cases of acute respiratory illness, almost half a million RSV-associated hospitalizations, and more than 33 000 in-hospital deaths [6]. Although available studies suggest that RSV morbidity and mortality may be comparable to influenza in older adults [7], the burden of adult RSV disease is underestimated [6, 8].

Like RSV illness, influenza is typically seasonal, with winter peaks in temperate climates. Older adults, particularly those with medical comorbidities, are at increased risk of influenza morbidity and mortality [9], and annual seasonal influenza vaccination is recommended in this population to prevent illness or reduce illness severity [10]. In some countries, high-dose or adjuvanted influenza vaccines are preferentially recommended for adults aged 65 years and older [11–13].

The RSV prefusion F protein–based (RSVpreF) vaccine is a bivalent vaccine containing stabilized prefusion F glycoproteins (preF) from the 2 major co-circulating antigenic subgroups (RSV-A and RSV-B) [14, 15]. In an ongoing global, pivotal phase 3 trial, vaccination with RSVpreF in adults aged 60 years and older was 89% effective in preventing RSV-associated lower respiratory tract illness with 3 or more signs or symptoms at the end of the first full RSV season [16, 17]. Based on the results of this trial, RSVpreF (ABRYSVO; Pfizer, Inc) was recently licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration for the prevention of lower respiratory tract disease caused by RSV in individuals aged 60 years and older [18]. RSVpreF vaccine is also licensed for the prevention of lower respiratory tract disease and severe lower respiratory tract disease caused by RSV in infants from birth through 6 months of age, based on efficacy and safety data from a study in pregnant individuals [18].

With the typical seasonality of both RSV and influenza, it is possible that RSVpreF vaccine may be given at the same time as seasonal influenza vaccine. Coadministration of these 2 seasonal vaccines would eliminate the need for an additional visit to a healthcare provider for individuals receiving both vaccines; this would likely be convenient for patients and healthcare providers and, in turn, potentially increase vaccination rates. It is important to understand whether the 2 vaccines can be safely coadministered and whether coadministration affects immune responses. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the safety and immunogenicity of RSVpreF when coadministered with seasonal inactivated influenza vaccine (SIIV) compared with administration of either vaccine alone.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

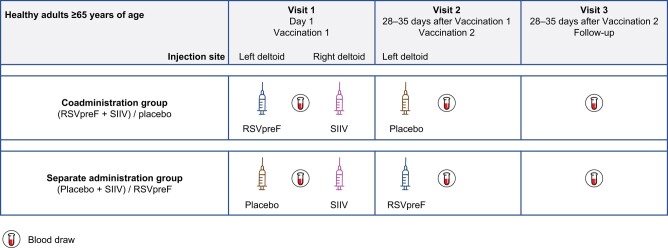

This phase 3, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind study was conducted at 31 sites (clinics) in Australia (NCT05301322). Participants were enrolled by the site staff and randomized 1:1 using interactive response technology to either the coadministration group (RSVpreF + SIIV [Fluad Quad; Seqirus, Inc] administered at visit 1 and placebo administered at visit 2 [1 month later]) or the individual vaccines alone in the sequential administration group (placebo + SIIV administered at visit 1 and RSVpreF administered at visit 2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design. Abbreviations: RSVpreF, respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F protein–based vaccine; SIIV, seasonal inactivated influenza vaccine.

The study included healthy men and women who were 65 years and older. Those with preexisting stable disease (ie, not requiring a significant change in therapy or hospitalization and without worsening of disease during the 6 weeks before enrollment) could participate. Participants were excluded if they had a serious chronic disorder, such as metastatic malignancy, end-stage renal disease, or clinically unstable cardiac disease; had a history of Guillain-Barré syndrome; had a history of severe allergic reaction with any vaccine; allergy to egg proteins or products; had received RSV vaccine any time before enrollment or influenza vaccine within 6 months before study vaccination; or were immunocompromised, with suspected immunodeficiency, or were receiving immunosuppressive therapies. Additional exclusion criteria and methods for randomization and blinding are outlined in the Supplementary Appendix.

The study was conducted in accordance with the consensus ethical principles derived from international guidelines, including the Declaration of Helsinki and the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences International Ethical Guidelines, applicable International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and applicable laws and regulations, including privacy laws. All participants provided written informed consent.

Immunogenicity Objectives and Assessments

Blood was collected before each vaccination and 1 month after the second vaccination, and serum was prepared for immunogenicity assessments. The primary RSV immunogenicity objective was to demonstrate that the immune responses, measured by RSV-A and RSV-B neutralizing titers, elicited by RSVpreF vaccine when coadministered with SIIV were noninferior to those elicited by RSVpreF vaccine alone. The primary SIIV immunogenicity objective was to demonstrate that the immune responses, measured by strain-specific hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) titers, elicited by SIIV when coadministered with RSVpreF were noninferior to those elicited by SIIV alone.

The secondary immunogenicity objectives were to describe the immune responses elicited by RSVpreF and SIIV when coadministered or when administered alone. Exploratory objectives included descriptions of seroprotection and seroconversion rates after SIIV when coadministered with RSVpreF or when administered alone.

Safety Objectives and Assessments

The primary safety objective was to evaluate the safety profiles of RSVpreF when coadministered with SIIV or when administered alone 1 month after SIIV. Local reactions at the RSVpreF or placebo injection site (left deltoid) and systemic events (including fever) occurring within 7 days after each vaccination were recorded by participants in an electronic diary (e-diary) device or smartphone app; SIIV injection-site reactions were not collected via the e-diary but reported as adverse events (AEs). Severity scales for local reactions and systemic events are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Adverse events and serious AEs (SAEs) occurring within 1 month after each vaccination were collected, and investigators assessed causality of AEs relative to the blinded study vaccine (RSVpreF/placebo). The AEs were categorized according to Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities v25.1 terms [19].

Statistical Analysis

Sample-size considerations are summarized in the Supplementary Appendix. Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

The geometric mean ratios (GMRs) of RSV neutralizing titers in the coadministration group to the sequential administration group for RSV-A and RSV-B at 1 month after RSVpreF vaccination were determined along with associated 2-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The GMRs of strain-specific HAI titers in the coadministration group to the sequential administration group at 1 month after receipt of SIIV were determined along with the associated 2-sided 95% CIs. Using a 1.5-fold margin, noninferiority was declared if the lower bound of the 2-sided 95% CI for each GMR was greater than 0.667 for all 4 SIIV strains (H1N1 A/Victoria, H3N2 A/Darwin, B/Austria, and B/Phuket) and for both RSV-A and RSV-B. The 1.5-fold noninferiority margin and lower-bound 2-sided 95% CI cutoff are consistent with the noninferiority criteria used in other vaccine trials [20] and based on precedent established in discussion with regulatory agencies. An exploratory subgroup analysis of the primary immunogenicity endpoints stratified by age (65‒74 years and ≥75 years) was also conducted.

Geometric means (at each applicable visit) and geometric mean fold-rises (GMFRs; from before to each applicable time point after RSVpreF vaccination) of the RSV neutralizing titers and the associated 2-sided 95% CIs were determined for each vaccine group (coadministration group vs sequential administration group) for RSV-A and RSV-B. Geometric means (at baseline and 1 month after SIIV) and GMFRs (from before vaccination to 1 month after vaccination with SIIV) of strain-specific HAI titers and the associated 2-sided 95% CIs were summarized similarly.

Empirical reverse cumulative distribution curves plotted the proportions of participants with values equal to or exceeding a specified assay value versus the indicated assay value for all observed assay values. Seroprotection (defined as strain-specific HAI titers ≥1:40 before vaccination and 1 month after vaccination with SIIV) rates were determined along with the associated Clopper-Pearson 95% CIs. Seroconversion was defined as an HAI titer less than 1:10 before vaccination with SIIV and with an HAI titer of 1:40 or greater 1 month after vaccination with SIIV, or an HAI titer 1:10 or greater before vaccination and with a 4-fold or more increase in HAI titer 1 month after vaccination with SIIV. For each influenza strain, counts and percentages of participants with strain-specific HAI titer seroconversion 1 month after vaccination with SIIV were determined along with the associated Clopper-Pearson 95% CIs.

The primary safety objective was evaluated by descriptive summary statistics for local reactions, systemic events, AEs, and SAEs after each vaccination for each vaccine group along with 95% CIs computed using the Clopper-Pearson method.

RESULTS

Participants

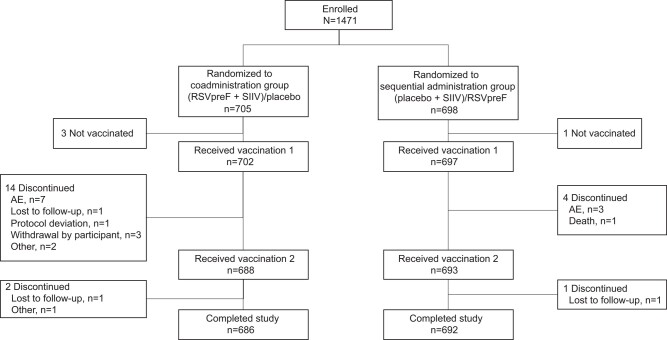

The study was conducted from 13 April to 12 October 2022 in Australia to coincide with the typical Southern Hemisphere RSV and influenza seasons. In total, 1403 participants were randomized (coadministration group, n = 705; sequential administration group, n = 698) (Figure 2). Overall, 98.2% (1378/1403) of participants completed the study (coadministration group, 97.3% [686/705]; sequential administration group, 99.1% [692/698]). Baseline demographic characteristics were well balanced between study groups (Table 1). The median (range) age was 70 (65–91) years; 55% (770/1399) of participants were female, 95% (1334/1399) were White, and 45% (630/1399) reported current or former tobacco use. The majority of participants (∼95%) reported a history of medical conditions expected in older adults, including respiratory and cardiac conditions (∼22% and 17% in each group, respectively). The clinically significant medical history of the participants is summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Figure 2.

Participant disposition. “Enrolled” refers to participants who were recruited by study site staff and gave written informed consent, regardless of whether they were randomized. Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; RSVpreF, respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F protein–based vaccine; SIIV, seasonal inactivated influenza vaccine.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| Coadministration Group (RSVpreF + SIIV)/placebo (na = 703) | Sequential Administration Group (Placebo + SIIV)/RSVpreF (na = 696) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at vaccination, median (range), y | 70 (65–91) | 70 (65–88) |

| Age group at vaccination 1, n (%) | ||

| 65–74 y | 567 (80.7) | 559 (80.3) |

| ≥75 y | 136 (19.3) | 137 (19.7) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 305 (43.4) | 324 (46.6) |

| Female | 398 (56.6) | 372 (53.4) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 669 (95.2) | 665 (95.5) |

| Asian | 22 (3.1) | 21 (3.0) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 4 (0.6) | 3 (0.4) |

| Not reported | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.3) | 4 (0.6) |

| Multiracial | 4 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) |

| Racial designation, n (%) | ||

| Indigenous Australianb | 3 (0.4) | 6 (0.9) |

| Otherc | 302 (43.0) | 281 (40.4) |

| Missing | 398 (56.6) | 409 (58.8) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic/non-Latino | 652 (92.7) | 647 (93.0) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 5 (0.7) | 8 (1.1) |

| Not reported | 46 (6.5) | 41 (5.9) |

| Tobacco use, n (%) | ||

| Current | 30 (4.3) | 36 (5.2) |

| Former | 294 (41.8) | 270 (38.8) |

| Never | 379 (53.9) | 390 (56.0) |

Data are for the safety population.

Abbreviations: RSVpreF, respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F protein-based vaccine; SIIV, seasonal inactivated influenza vaccine.

aNumber of participants in the specified vaccine group; these values were used as the denominators for the percentage calculations.

bDefined as a racial designation being Australian Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander.

cDefined as a non-missing racial designation other than Australian Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander and includes Indian Subcontinent Asian, Southeast Asian, Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, and other.

Immunogenicity

For the primary immunogenicity evaluation, 1352 (96%) participants were included in the evaluable RSV immunogenicity population and 1367 (97%) were included in the evaluable SIIV immunogenicity population.

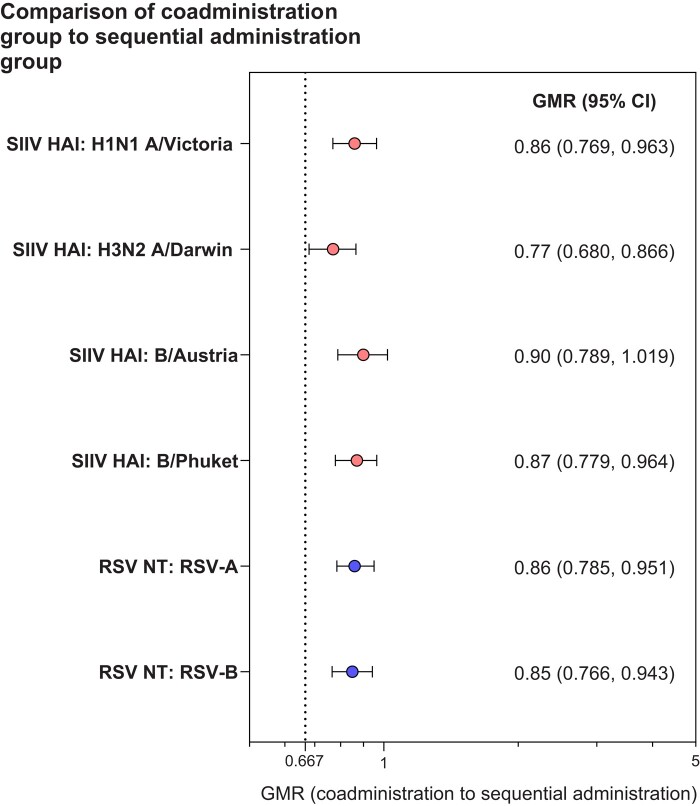

The GMRs for coadministration to sequential administration were 0.86 for RSV-A and 0.85 for RSV-B neutralizing titers at 1 month after RSVpreF vaccination and 0.77 to 0.90 for strain-specific HAI titers at 1 month after vaccination with SIIV (Figure 3), with each of the 6 assay strains/subgroups achieving the 1.5-fold prespecified noninferiority margin (lower bound 95% CI >0.667). The primary immunogenicity objectives of the study were therefore achieved. In the subgroup analysis, immune responses in participants aged 75 years and older were consistent with the overall population (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 3.

Geometric mean ratios (95% CIs) for influenza strain HAI titers and RSV neutralizing titers at 1 month after vaccination. Data are for the evaluable SIIV immunogenicity population and evaluable RSV immunogenicity population. Two-sided 95% CIs were based on the Student’s t distribution. The dotted line represents the prespecified noninferiority margin. The number of participants with valid and determinate assay results for the specified assay in the respective evaluable immunogenicity population was 674–681. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GMR, geometric mean ratio; HAI, hemagglutination inhibition; NT, 50% neutralizing titer; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RSVpreF, respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F protein–based vaccine; SIIV, seasonal inactivated influenza vaccine.

The GMFRs of RSV 50% neutralizing titers from baseline (before vaccination) to 1 month after vaccination showed robust immune responses when RSVpreF was coadministered with SIIV (10.0 and 10.1 for RSV-A and RSV-B, respectively) or administered alone (11.4 and 12.0, respectively) (Supplementary Figure 2A). The GMFRs of the HAI assay 1 month after receiving SIIV alone ranged from 2.3 to 5.4 across the 4 influenza strains, and GMFRs 1 month after receiving SIIV coadministered with RSVpreF ranged from 2.1 to 4.1 (Supplementary Figure 2B).

Reverse cumulative distribution curves of RSV-A and RSV-B 50% neutralizing titers 1 month after RSVpreF was coadministered with SIIV or administered alone and of HAI titers 1 month after SIIV was coadministered with RSVpreF or administered alone are shown in Supplementary Figure 3. Rates of seroprotection and seroconversion were generally similar across the 4 influenza strains (Supplementary Table 3).

Safety

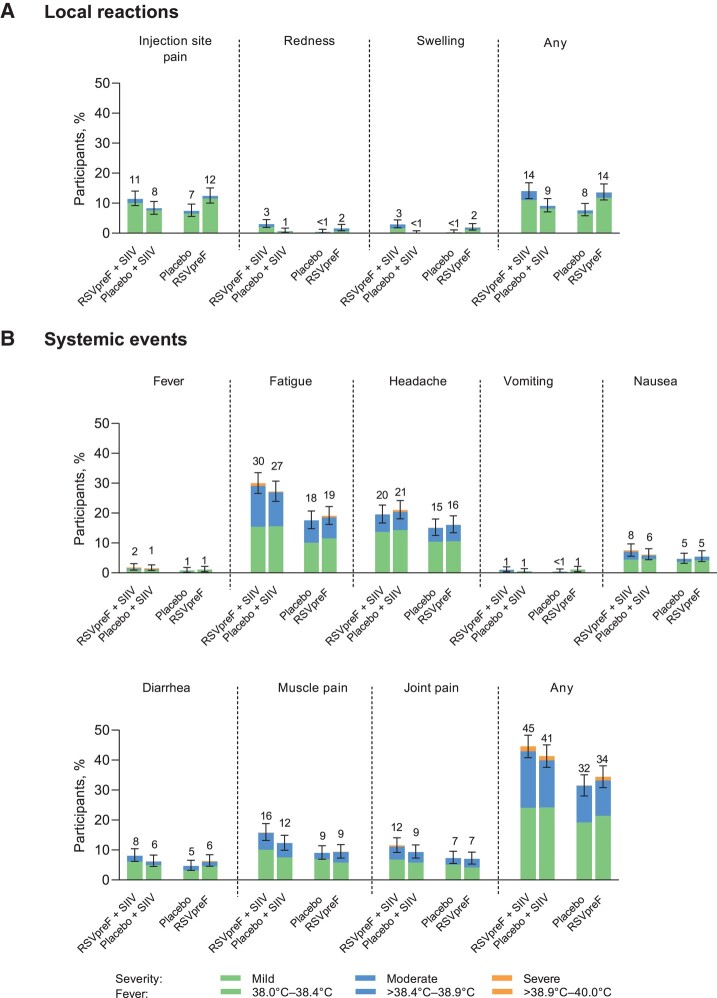

Local reactions and systemic events were mostly mild or moderate when RSVpreF was coadministered with SIIV. Local reaction rates were assessed only at the RSVpreF or placebo injection site and were higher after vaccination with RSVpreF (either with SIIV coadministered in the contralateral arm or given alone) compared with placebo (13.7−14.0% vs 7.6−9.1%) (Figure 4A). The most common local reaction was injection-site pain (reported in 11.4–12.4% of participants after receiving RSVpreF). Systemic events reported after receiving RSVpreF plus SIIV concomitantly (44.7%) were slightly higher than for those receiving placebo and SIIV (41.4%), followed by RSVpreF alone (34.4%) and placebo alone (31.6%) (Figure 4B). The most commonly reported systemic events were fatigue (30.0% of participants receiving RSVpreF plus SIIV concomitantly, 27.1% receiving placebo and SIIV, 19.1% receiving RSVpreF alone, and 17.6% receiving placebo alone) and headache (19.7% after receiving RSVpreF plus SIIV concomitantly, 20.9% after placebo and SIIV, 16.2% after RSVpreF alone, and 15.1% after placebo). Most systemic events were mild or moderate; the percentage of participants reporting any severe systemic event after vaccination was 0.1% to 1.7% across groups. The occurrence of fever after vaccination was low (1.9% after receiving RSVpreF plus SIIV concomitantly, 1.4% after placebo and SIIV, 1.2% after RSVpreF alone, and 0.9% after placebo); no fevers higher than 40.0°C were reported during the study. The median onset of local reactions after receiving RSVpreF plus SIIV concomitantly or RSVpreF alone was 1 to 2 days after vaccination and resolved after a median duration of 1 to 2 days. The median onset of systemic events after receiving RSVpreF plus SIIV concomitantly or RSVpreF alone was 1 to 3 days and 1 to 3.5 days after vaccination, respectively. The median duration of systemic events after receiving RSVpreF plus SIIV concomitantly or RSVpreF alone was 1 to 2 days.

Figure 4.

Local reactions (A) and systemic events (B) reported within 7 days of vaccination. Data are for the safety population. Severity grading of the specific local reactions and systemic events is provided in Supplementary Table 1. Error bars represent 95% CIs computed using the Clopper-Pearson method and numbers above the bars indicate the percentage of participants in each group reporting the specified event (rounded to whole numbers). Local reactions were reported by participants at the RSVpreF or placebo injection site only. RSVpreF + SIIV (n = 701); placebo (n = 681); placebo + SIIV (n = 693); RSVpreF alone (n = 686). Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RSVpreF, respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F protein–based vaccine; SIIV, seasonal inactivated influenza vaccine.

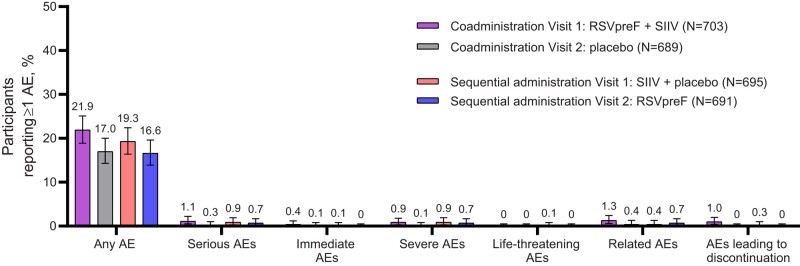

For AEs reported within 1 month after each vaccination, 21.9% of participants reported AEs after receiving RSVpreF plus SIIV concomitantly, 19.3% after placebo and SIIV, 16.6% after RSVpreF alone, and 17.0% after placebo alone (Figure 5). The most commonly reported AEs within 1 month after each vaccination were in the infections and infestations system organ class (8.8−12.2%), with COVID-19 being the most frequent AE (2.9−5.1%) (Supplementary Table 4). Atrial fibrillation was reported by 3 participants, all considered by the investigator to be unrelated to study vaccination: 1 participant on day 31 after receiving RSVpreF plus SIIV (nonserious AE, related to coronary artery bypass graft surgery), 1 participant on day 22 after receiving RSVpreF alone (SAE, related to aortic valve replacement procedure), and 1 participant on day 26 after receiving RSVpreF alone (nonserious AE, not related to study vaccination). The only AE reported in more than 1 participant that was considered to be related to study vaccination (either RSVpreF or placebo) by the investigator was lymphadenopathy, which occurred in 2 (0.3%) participants after coadministration of RSVpreF and SIIV (1 participant reported submandibular lymphadenopathy on day 2 after vaccination lasting 3 days; the other reported enlarged neck lymph node on day 2 after vaccination lasting 1 day).

Figure 5.

Adverse event summary within 1 month of each vaccination. Data are for the safety population. The numbers above the bars show the percentage of participants who experienced 1 or more of the specified type of event within 1 month after the respective vaccination. Error bars represent exact 2-sided 95% CIs calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method. An immediate AE was defined as any AE that occurred within the first 30 minutes after administration of study vaccine (RSVpreF or placebo). Related AEs were determined by the investigator. Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; CI, confidence interval; RSVpreF, respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F protein–based vaccine; SIIV, seasonal inactivated influenza vaccine.

One month after vaccination, SAEs were reported in 1.1% of participants who received RSVpreF plus SIIV concomitantly and in 0.9% of those receiving placebo and SIIV; no SAEs were considered to be study vaccine–related. No participants reported Guillain-Barré syndrome or other immune-mediated demyelinating conditions. One participant with a history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, mitral valve incompetence, and aortic stenosis died of cardiac failure 28 days after receipt of placebo and SIIV; the death was not considered vaccine-related by the investigator.

DISCUSSION

We found that the bivalent RSVpreF vaccine and SIIV can be safely coadministered to individuals aged 65 years and older, with immune responses meeting the prespecified immunogenicity endpoint for noninferiority for both vaccines. Robust immune responses were observed when RSVpreF was coadministered with SIIV or given alone. When RSVpreF was administered alone, RSV neutralizing titer GMFRs were similar to previous studies in this age group [21, 22]. Immune responses were similar among study groups, with comparable HAI titer seroprotection and seroconversion rates. A subgroup analysis showed that results in participants aged 75 years and older were consistent with the overall population, albeit with wider CIs due to lower numbers relative to 65- to 74-year-olds. The HAI titers for H3N2 trended lower than the other influenza strains tested, but met noninferiority criteria. Collectively, these results support coadministration of RSVpreF and SIIV as an appropriate option, as evidenced by noninferior immune responses and lack of clinically significant tolerability or safety issues. No neuroinflammatory or demyelinating conditions were reported in the study.

By eliminating the need for an additional vaccination visit, coadministration of RSVpreF vaccine and influenza vaccine in individuals who are recommended to receive both vaccines may offer convenience to patients and healthcare providers. At the end of the 2022–2023 winter, influenza vaccine uptake in the United States was 71% in adults aged 65 years and older, which was higher than the previous year [23]. If this encouraging uptake could be sustained and influenza vaccine coadministered with RSVpreF, this would help protect a substantial proportion of older adults against these important respiratory pathogens. This is especially important given the surge in RSV cases in the Northern Hemisphere in the fall of 2022 [24, 25]. Coadministration of influenza vaccines with other respiratory vaccines, for example those targeting COVID-19 and pneumococcal disease, has also been shown to be safe and immunogenic [26–28].

Although this study was conducted in older adults, we expect that the favorable safety profile and robust immunogenicity observed with coadministration would support broader application.

Strengths of this study include the randomized, double-blind design, which enabled comparison of RSVpreF and SIIV coadministration to sequential administration while providing all participants with both vaccines. The study was conducted in adults 65 years and older, a population well recognized for being substantially at risk of severe complications of both RSV illness and influenza infection [5, 9]. Study limitations include that the only participants evaluated were those aged 65 years and older from Australia, with demographic characteristics that differ from other countries. Another study limitation is that immunocompromised individuals were excluded.

Conclusions

The study met the primary endpoint, demonstrating that immune responses to RSVpreF and SIIV were noninferior when the vaccines were coadministered. The results also support the safety and tolerability of RSVpreF when coadministered with SIIV. Collectively, these results support coadministration of RSVpreF and SIIV in adults aged 65 years and older to help protect against these 2 important respiratory pathogens in this vulnerable population.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Eugene Athan, Barwon Health, Deakin University, Geelong, Victoria, Australia.

James Baber, Vaccine Clinical Research, Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Karen Quan, Vaccine Clinical Research, Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Robert J Scott, USC Clinical Trials, Sippy Downs, Queensland, Australia.

Anna Jaques, Vaccine Clinical Research, Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Qin Jiang, Pfizer Vaccine Research and Development, Collegeville, Pennsylvania, USA.

Wen Li, Pfizer Vaccine Research and Development, Collegeville, Pennsylvania, USA.

David Cooper, Pfizer Vaccine Research and Development, Pearl River, New York, USA.

Mark W Cutler, Pfizer Vaccine Research and Development, Pearl River, New York, USA.

Elena V Kalinina, Pfizer Vaccine Research and Development, Pearl River, New York, USA.

Annaliesa S Anderson, Pfizer Vaccine Research and Development, Pearl River, New York, USA.

Kena A Swanson, Pfizer Vaccine Research and Development, Pearl River, New York, USA.

William C Gruber, Pfizer Vaccine Research and Development, Pearl River, New York, USA.

Alejandra Gurtman, Pfizer Vaccine Research and Development, Pearl River, New York, USA.

Beate Schmoele-Thoma, Pfizer Pharma GmbH, Berlin, Germany.

for the Study C3671006 Investigator Group:

Christopher Argent, Mark Arya, Eugene Athan, Paul Bird, Mark Bloch, Sheetal Bull, David Colquhoun, Gustinna De Silva, Sachin Deshmukh, Peter Eizenberg, Christopher Gilfillan, Elizabeth Gunner, Valerie Hiew, Amber Leah, Indika Leelasena, Jason Lickliter, Anthony McGirr, Rahul Mohan, Claire Morbey, Louise Murdoch, Mark Nelson, A Munro Neville, Matthew O'Sullivan, Christopher Rook, Marc Russo, Philip Ryan, Robert Scott, Sze Tai, Florence Tiong, Olga Voloshyna, and Peter Wark

Notes

Author Contributions. E. A. and R. J. S. were involved in data collection and analysis and interpretation of results. J. B., K. Q., A. J., Q. J., D. C., A. S. A., K. A. S., W. C. G., A. G., and B. S.-T. were involved in study concept and design, and analysis and interpretation of results. W. L. was involved in analysis and interpretation of results. M. W. C. was involved in data collection. E. V. K. was involved in the study concept and design and data collection. All authors drafted the manuscript and/or reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments. The authors thank all of the participants who volunteered for this trial; the investigators and study site personnel in the C3671006 Clinical Trial Group for their contributions; as well as Pfizer colleagues from Vaccine Clinical Research and Development, High-Throughput Clinical Testing, Clinical Development Operations, Global Site and Study Operations, Pharmaceutical Sciences, Vaccine Regulatory, and Project Management for their contributions to the success of this study. Editorial/medical writing support was provided by Sheena Hunt, PhD, and Tricia Newell, PhD, of ICON (Blue Bell, PA, USA) and was funded by Pfizer, Inc.

Data availability. Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions, and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

Financial support. This work was supported by Pfizer, Inc.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) disease. Available at: https://www.who.int/teams/health-product-policy-and-standards/standards-and-specifications/vaccine-standardization/respiratory-syncytial-virus-disease. Accessed 18 May 2023.

- 2. Chadha M, Hirve S, Bancej C, et al. Human respiratory syncytial virus and influenza seasonality patterns—early findings from the WHO Global Respiratory Syncytial Virus Surveillance. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2020; 14:638–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baker RE, Park SW, Yang W, Vecchi GA, Metcalf CJE, Grenfell BT. The impact of COVID-19 nonpharmaceutical interventions on the future dynamics of endemic infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020; 117:30547–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eden JS, Sikazwe C, Xie R, et al. Off-season RSV epidemics in Australia after easing of COVID-19 restrictions. Nat Commun 2022; 13:2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . RSV in older adults and adults with chronic medical conditions. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/high-risk/older-adults.html. Accessed 18 May 2023.

- 6. Savic M, Penders Y, Shi T, Branche A, Pircon JY. Respiratory syncytial virus disease burden in adults aged 60 years and older in high-income countries: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2023; 17:e13031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ackerson B, Tseng HF, Sy LS, et al. Severe morbidity and mortality associated with respiratory syncytial virus versus influenza infection in hospitalized older adults. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69:197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tin Tin Htar M, Yerramalla MS, Moïsi JC, Swerdlow DL. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Infect 2020; 148:e48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Langer J, Welch VL, Moran MM, et al. High clinical burden of influenza disease in adults aged ≥ 65 years: can we do better? A systematic literature review. Adv Ther 2023; 40:1601–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization . Influenza (seasonal). Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal). Accessed 18 May 2023.

- 11. Grohskopf LA, Blanton LH, Ferdinands JM, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022–23 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep 2022; 71:1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. UK Security Health Agency . National flu immunisation programme 2023 to 2024 letter. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-flu-immunisation-programme-plan/national-flu-immunisation-programme-2023-to-2024-letter. Accessed 28 November 2023.

- 13. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care . Australian immunisation handbook. Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/immunisation/when-to-get-vaccinated/national-immunisation-program-schedule. Accessed 30 May 2023.

- 14. Walsh EE, Falsey AR, Scott DA, et al. A randomized phase 1/2 study of a respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F vaccine. J Infect Dis 2022; 225:1357–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ghildyal R, Hogg G, Mills J, Meanger J. Detection and subgrouping of respiratory syncytial virus directly from nasopharyngeal aspirates. Clin Microbiol Infect 1997; 3:120–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Walsh EE, Polack FP, Zareba AM, et al. Efficacy and safety of bivalent respiratory syncytial virus (RSVpreF) vaccine in older adults. Presented at: IDWeek; October 19–23, 2022; Washington, DC.

- 17. Gurtman A. ACIP meeting respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) older adults vaccine: RSVpreF older adults: clinical development program updates. Available at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/129992. Accessed 24 July 2023.

- 18. ABRYSVO (RSVpreF vaccine) . Full prescribing information. New York, NY: Pfizer, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Medical Dictionary for Research Activities . Available at: https://www.meddra.org/. Accessed 28 November 2023.

- 20. Donken R, de Melker HE, Rots NY, Berbers G, Knol MJ. Comparing vaccines: a systematic review of the use of the non-inferiority margin in vaccine trials. Vaccine 2015; 33:1426–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baber J, Arya M, Moodley Y, et al. A phase 1/2 study of a respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F vaccine with and without adjuvant in healthy older adults. J Infect Dis 2022; 226:2054–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Falsey AR, Walsh EE, Scott DA, et al. Phase 1/2 randomized study of the immunogenicity, safety, and tolerability of a respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F vaccine in adults with concomitant inactivated influenza vaccine. J Infect Dis 2022; 225:2056–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Weekly flu vaccination dashboard. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/dashboard/vaccination-dashboard.html#:∼:text=Estimates%20as%20of%20the%20end,the%20end%20of%202019%2D20. Accessed 30 May 2023.

- 24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Increased respiratory virus activity, especially among children, early in the 2022–2023 fall and winter. Available at: https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2022/han00479.asp#print. Accessed 30 May 2023.

- 25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . RSV-NET. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/research/rsv-net/dashboard.html. Accessed 20 June 2023.

- 26. Cannon K, Cardona JF, Yacisin K, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine coadministered with quadrivalent influenza vaccine: a phase 3 randomized trial. Vaccine 2023; 41:2137–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Izikson R, Brune D, Bolduc JS, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a high-dose quadrivalent influenza vaccine administered concomitantly with a third dose of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in adults aged ≥65 years: a phase 2, randomised, open-label study. Lancet Respir Med 2022; 10:392–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shenyu W, Xiaoqian D, Bo C, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a SARS-CoV-2 inactivated vaccine (CoronaVac) co-administered with an inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine: a randomized, open-label, controlled study in healthy adults aged 18 to 59 years in China. Vaccine 2022; 40:5356–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.