Abstract

Objectives:

The present study investigated the roles birthplace and acculturation play in sleep estimates among Hispanic/Latino population at the US-Mexico border.

Measures:

Data were collected in 2016, from N=100 adults of Mexican descent from the city of Nogales, AZ, at the US-Mexico border. Sleep was assessed with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Insomnia Severity Index categorized as none, mild, moderate, and severe, and Multivariable Apnea Prediction Index (MAP) categorized as never, infrequently, and frequently. Acculturation was measured with the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican-Americans II (ARSMA-II).

Results:

The sample consisted of majority Mexican-born (66%, vs. born in the USA 38.2%). Being born in the USA was associated with 55 fewer minutes of nighttime sleep (p=0.011), and 1.65 greater PSQI score (p=0.031). Compared to no symptoms, being born in the USA was associated with greater likelihood of severe difficulty falling asleep (OR=8.3, p=0.030) and severe difficulty staying asleep (OR=11.2, p=0.050), as well as decreased likelihood of breathing pauses during sleep (OR=0.18, P=0.020). These relationships remained significant after Mexican acculturation was entered in these models. However, greater Anglo acculturation appears to mediate one fewer hour of sleep per night, poorer sleep quality, and reporting of severe difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep.

Conclusions:

Among individuals of Mexican descent, being born in the USA (vs Mexico) is associated with about 1 hour less sleep per night, worse sleep quality, more insomnia symptoms, and less mild sleep apnea symptoms. These relationships are influenced by acculturation, primarily degree of Anglo rather than degree of Mexican acculturation.

Keywords: sleep disparities, acculturation, border health, Mexican Americans, nativity

Introduction

Sleep is a biological need and crucial for overall well-being, as poor sleep has been associated with poor health, including obesity (Cappuccio et al., 2008; Patel & Hu, 2008; Teodorescu et al., 2013), cardiovascular disease (Altman et al., 2012; Kawada, 2016; Vgontzas et al., 2009), mortality (Addison et al., 2014; Grandner, Patel, et al., 2010; Kawada, 2016), daytime sleepiness, and deficits in neuro-cognitive function (Alvarez & Ayas, 2004). Poor sleep may represent a unique factor existing at the interface of downstream physiological outcomes and upstream environmental/social/behavioral determinants. The Social Ecological Model of Sleep and Health (Grandner, Hale, et al., 2010) conceptualizes the role of sleep in bridging from upstream environmental/social/behavioral influences and to downstream health outcomes. Facets of sleep have direct effects on both physiological and behavioral mechanisms, that may lead to the negative health outcomes (Altman et al., 2012; Grandner, Seixas, et al., 2016; Markwald et al., 2013; Patel & Hu, 2008; Patel et al., 2015). Furthermore, poor sleep quality may contribute to a number of psychological disturbances including insomnia (Kempler et al., 2016), depression (Becker et al., 2017), anxiety (Gould et al., 2016) and suicide (Bernert et al., 2014). Sleep disturbances such as early morning awakenings, difficulty falling asleep, and poor sleep quality possess a cumulative number of effects that affect millions of US adults daily, yet it remains an unrecognized public health challenge (Hale et al., 2020).

Racial/ethnic disparities in sleep health influence broader indices of overall health (Letzen et al., 2021; Piccolo et al., 2013; Williams et al., 2015). For example, racial minority groups have worse health outcomes and are at increased likelihood of sleep disparities (X. Chen et al., 2015; Jean-Louis & Grandner, 2016; Kingsbury et al., 2013; Petrov & Lichstein, 2016; Williams et al., 2015). Although sleep research looking at diverse populations in the United States exists, it is scarce and requires further investigation. It is important to address racial and ethnic disparities as racial minority populations are already at a significantly higher risk for health disparities (Grandner, Williams, et al., 2016). Further, growing research demonstrates minorities are also more likely to experience shorter sleep durations, less deep sleep and inconsistent sleep timing (Johnson et al., 2019). Location of birth may play a role in racial/ethnic minority groups and sleep, as environment and culture are implicated in sleep health (Newsome et al., 2017; Whinnery et al., 2014).

Relationships between ethnic groups and location of birth have been reported to impact sleep duration and sleep disturbances, however, only a handful of studies looking at the relationship exist in the literature. An epidemiological study that analyzed data collected from adult participants in the 2000–2013 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) looked at birthplace and reported hours of sleep (N=416,152) (Newsome et al., 2017). The results showed that Indian subcontinent-born respondents reported healthy sleep at a higher rate than US-born respondents (OR=1.53, p<0.001) (Newsome et al., 2017). Overall, there was a 19% greater likelihood of sleeping 7–8h/night among foreign born individuals, compared to US-born individuals (OR=1.19, p<0.01) (Newsome et al., 2017). A more recent epidemiological study that analyzed data collected from adult participants in the 2004–2017 NHIS looked at birthplace and self-reported sleep characteristics (e.g. sleep duration, trouble falling asleep, trouble staying asleep, non-restorative sleep, and sleep medications use) among non-Hispanic whites and Hispanic/Latino adults in the US (Gaston et al., 2021). The results showed compared to US born non-Hispanic white adults, foreign-born non-Hispanic whites were not more likely to report non-recommended sleep duration (e.g very short sleep, short sleep and long sleep). However, they were more likely to report trouble staying asleep, non-restorative sleep and sleep medication use (Gaston et al., 2021). Also, compared to US born non-Hispanic whites, US born Mexican adults were as likely to report non-recommended sleep duration, however foreign-born Mexican adults were less likely to report non-recommended sleep duration (Gaston et al., 2021). Overall, adults of Mexican descent were less likely to report sleep disturbances and use of sleep medications, compared to US-born non-Hispanic whites (Gaston et al., 2021).

Furthermore, looking at differences in sleep durations with relation to birthplace, non-US born Latinos, compared to whites, were less likely to report short sleep (Whinnery et al., 2014). Interestingly,US-born Mexican adults were no more likely to report trouble staying asleep compared with foreign-born non-Hispanic whites; however foreign-born Mexican adults were less likely to report trouble staying asleep (Gaston et al., 2021).

Although previous research demonstrates considerable differences among Latino’s health behaviors based on their location of birth (Johnson et al., 2019), research is limited regarding sleep patterns and sleep behaviors. Recent studies expanding on habitual sleep research, show sleep duration is declining amongst Mexican Americans at twice the rate as non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks (Sheehan et al., 2019). In addition, studies have indicated that being born in Mexico is associated with fewer sleep disturbances and better sleep quality (Seicean et al., 2011). Literature also shows Mexicans born in the United States, who may be more Anglo accultured, are generally less healthy than those born in Mexico (Johnson et al., 2019) and have greater negative health behaviors (Hale & Rivero-Fuentes, 2011). Mexican-Americans have been previously reported to have difficulties with short sleep (Cespedes et al., 2016; X. Chen et al., 2015), insomnia (Cespedes et al., 2016; Kaufmann et al., 2016), and sleep apnea (X. Chen et al., 2015), compared to non-Hispanic whites. A recent cross-sectional study (Garcia et al., 2020) assessed self-reported data from the National Health and Interview Survey (NHIS), 2004–2007 (N=303,244), that included nativity status. They found that Latino subgroups born in the US (excluding US-born Cubans) are more likely to report poor sleep duration (Garcia et al., 2020). Interestingly, regardless of birthplace, Puerto Rican adults were more likely than US-born non-Hispanic whites, to report very short sleep and short sleep (Gaston et al., 2021). Findings of these studies can be partially explained by acculturation, as it appears to play an integral role in the relationship between sleep and health outcomes (Hale & Rivero-Fuentes, 2011; Hale et al., 2014).

The healthy immigrant effect refers to the fact that recent migrants are in better health than the nonimmigrant population in the host country (Hamilton & Hagos, 2021). However, over an average of 10–20 years, the health of migrants converges with the native population in the destination country (Markides & Rote, 2019). The decline in the health advantage as duration of stay increases, might be related to combination of multiple factors, one of which includes stress of acculturation (Markides & Rote, 2019). Acculturation has been broadly defined as any change that results from contact between individuals, or groups of individuals, and those from different cultural backgrounds. Research has noted that acculturation and ethnic stress amongst Latinos are also associated with poor sleep (Alcantara et al., 2017) and negative health outcomes (Ahluwalia et al., 2007; Hale & Rivero-Fuentes, 2011). Specifically, in a sample of individuals of Mexican descent, greater Anglo acculturation has been shown to reduce weekend sleep duration and efficiency, worsen insomnia severity and sleep quality, and increase sleep apnea risk and sleep medication use (Ghani, Delgadillo, et al., 2020; Kachikis & Breitkopf, 2012). Also, greater Anglo acculturation may be a predictor of worse health outcomes (Hale & Rivero-Fuentes, 2011), due to adaptation of a westernized lifestyle. It is reasonable to suggest that culture in society may influence sleep, therefore location of birth may represent another pathway influencing sleep disparities amongst minorities.

Most epidemiological and laboratory studies regarding Hispanic/Latinos and Mexican Americans have not used validated or standardized questionnaires to measure sleep and have not accounted for acculturation. Additionally, studies are mostly focused on urban settings (Kachikis & Breitkopf, 2012; Martinez-Miller et al., 2019; Sorlie et al., 2010) and less work has been documented in more vulnerable towns and rural communities. These communities are more insular and may face different challenges when compared to urban Hispanic/Latinos. For example, speaking the Spanish language (always or in some context) is identified as being a barrier to work in these regions. Additionally, although the border region is one of the fastest growing in the nation, with a majority Hispanic population, there is also lower educational attainments, lower income status, higher rates of unemployment and poverty, significant shortage of health care providers. In Nogales, Arizona, a population of about 20,000 residents, approximately 94% of the residents identify as Hispanic/Latino, 18% of the residents obtained a college degree, 30% live in poverty, median annual income per household is $29,000, and 20% of the residents below the age of 65, are without health insurance (US Census Bureau, 2021). According to the United States Census Bureau, Nogales, AZ is considered a rural region as the total population is <50,000 (US Census Bureau, 2021).

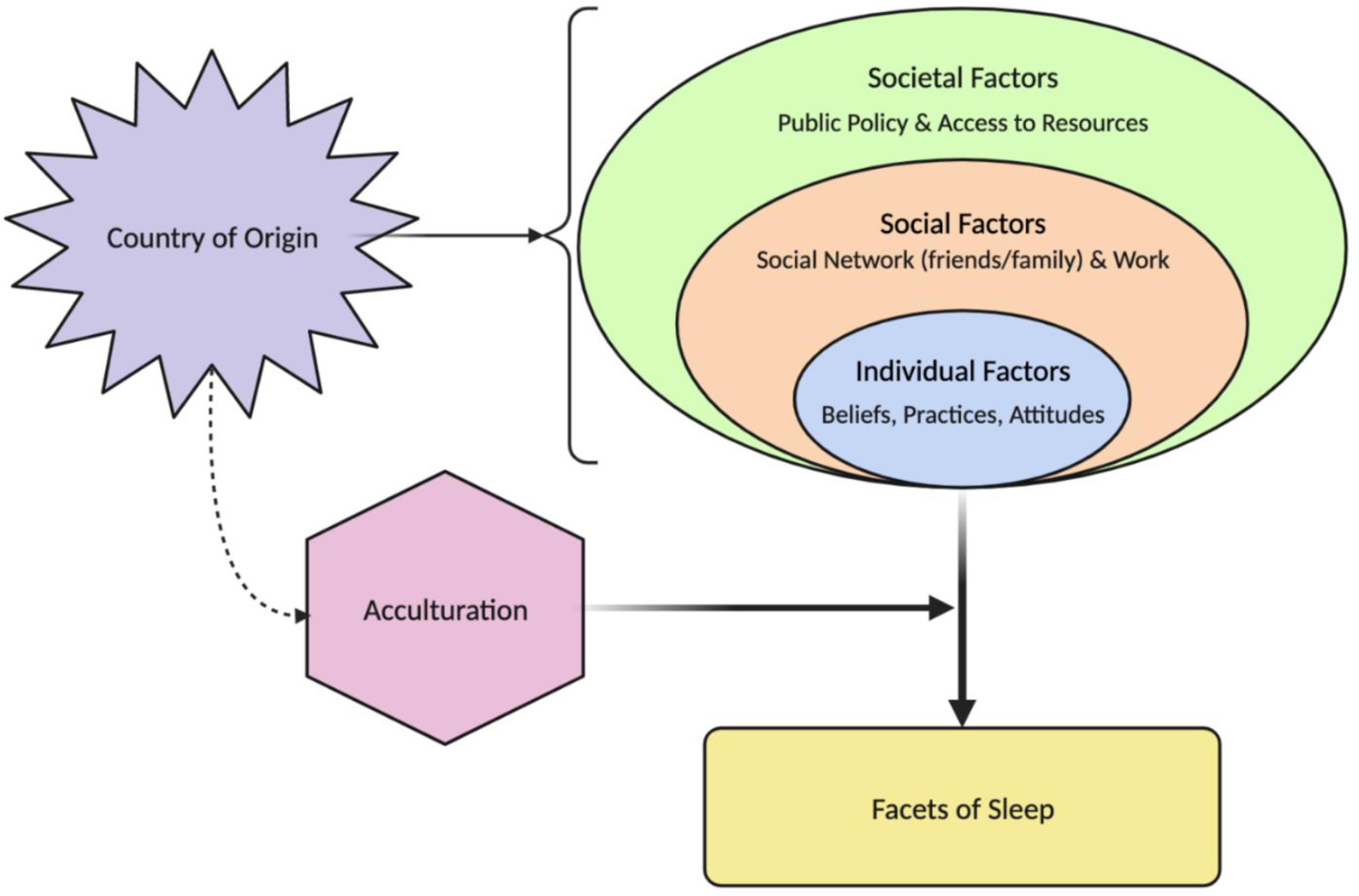

Country of origin may influence sleep health, especially in a border region. The hypothesized model for this relationship can be seen in Figure 1 [Figure 1 near here]. In this image, the social-ecological model of sleep health is abbreviated to include upstream individual factors (e.g. beliefs and practices), embedded in social factors (e.g. family and work), which are then embedded in societal factors (e.g. policy and access to resources), that influence sleep health. In our hypothesized model, country of origin exerts influence on all three of these levels, in various ways, indirectly influencing sleep health. Further complicating this issue at the border is acculturation, which serves as a filter (e.g., moderator) by which these factors influenced by country of origin themselves influence sleep health. For example, country of origin may have instilled certain sleep-related practices, stressed certain social norms, and provided certain societal structures that influenced sleep health, but the current influence of those may be modified in the presence of acculturation, which may change, replace, or compete with existing beliefs/practices, social norms, and/or societal structures.

Figure 1:

Abbreviated Socioecological model of sleep health

Limited work has been done at the border regarding health disparities, although it has important public health implications. Even less work has been done regarding sleep disparities and nativity status, as identifying sleep disparities by country of origin would allow for a new opportunity to identify modifiable risk factors. This is especially important in Mexican-Americans, as the negative health outcomes associated with short and long sleep duration (i.e., cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity) are prevalent in this population, when compared to non-Hispanic whites (Mozumdar & Liguori, 2011). Therefore, the present study examined the relationships between location of birth and sleep quality, sleep duration, insomnia severity and symptoms, and sleep apnea symptoms, while accounting for acculturation, in the city of Nogales, AZ at the US-Mexico border. We hypothesize those born in the United States (US) will have poorer sleep quality, reduced sleep duration, greater overall insomnia severity and severe insomnia symptoms and frequent snoring, gasping and breathing pauses episodes. We also hypothesize that Anglo acculturation will mediate several of these associations.

Methods

Participants

The sample population included N=100 adult participants who identified as Mexican descent. Participants were recruited in the fall of 2016, from Nogales, AZ, a city in Santa Cruz County, located at the US-Mexico Border. The sample was recruited as a convenience sample and only 100 participants were recruited, as this was a pilot study. Recruitment entailed in-person solicitations via booths outside of local shopping establishments, community centers and recreational areas. Advertisements included flyers and word of mouth, but also social media posts in both English and Spanish. Inclusion criteria included (1) ability to speak English or Spanish, (2) at least 18 years old, (3) identify as Mexican descent and residing in Nogales, AZ, (4) not considered a shift worker, (5) does not have a medical condition determined by the principal investigator to likely impede their ability to provide consent or participate. This study was approved by the University of Arizona Institutional Review Board (protocol # 1608763580) and written informed consent was obtained from participants prior to participation.

Measures

Surveys were administered in English or Spanish per the participant’s preference. All measures previously translated and validated were used when possible. For those questionnaires not previously translated in Spanish (MAP), guideline-based iterative translation procedures were followed (Hilton & Skrutkowski, 2002; Van de Vijver & Hambleton, 1996), that have been previously used (Ghani, Delgadillo, et al., 2020; Ghani et al., 2021).

Surveys were completed on touchscreen tablet devices. When necessary, study staff would help participants by providing guidance and assistance in both English and Spanish. All surveys were checked for completeness and there was no missing data.

Insomnia was assessed with the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) (Bastien et al., 2001) that assesses the nature, severity, and impact of insomnia (Bastien et al., 2001; Morin et al., 2011). We used both the published English (Bastien et al., 2001) and Spanish (Fernandez-Mendoza et al., 2012) versions. The internal consistency has been previously reported as 0.74 (Bastien et al., 2001), similar to the Cronbach alpha of this study, which was 0.77. Specific items from the ISI for difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, early morning awakenings, categorized as none, mild, moderate, and severe were utilized in the analysis. The ISI measure was used as a continuous variable.

Sleep quality and sleep duration were assessed with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (Buysse et al., 1989), a standard measure in sleep research that broadly assesses several dimensions of sleep. We used published English (Buysse et al., 1989) and Spanish (Tomfohr et al., 2013) versions. The PSQI calculates a total score based on 7 subscales, with scores over 5 considered as “poor” sleep quality. In addition to the overall score, sleep duration was assessed with the item asking “How many hours of actual sleep did you get at night? (This may be different than the number of hours you spend in bed).” Responses were assessed as a continuous variable. The Cronbach’s alpha of this study was 0.59, which reflects the heterogeneity within the PSQI measure.

Sleep apnea risk was assessed with items from Multivariable Apnea Prediction (MAP) Index (Maislin et al., 1995), a validated measure for assessing symptoms of snoring, waking up snorting/gasping, and breathing pauses during sleep as well as age, body mass index and sex. Sleep apnea risk is characterized as a percentage (0–100%) likelihood. We used the published English version and the translated Spanish version, that had been previously utilized in this Mexican-American population (Ghani, Delgadillo, et al., 2020). The Cronbach alpha for the self-reported items of the MAP was 0.71.

Acculturation was measured using the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican-Americans (ARSMA-II) (Cuellar et al., 1995), which is an appropriate scale to use in this population, as it was first developed in both English and Spanish language. ARSMA-II is a modified version of the original ARSMA scale, where the ARSMA-II scale is culture-specific for Mexican-Americans), however it has limited utility with other Hispanic (non-Mexican) groups (Cuellar et al., 1995). This scale computes separate subscales for Mexican and Anglo acculturation (subscale range 0–4), where greater scores indicate greater acculturation along each of those dimensions. The two cultural orientation subscales were found to have good internal reliabilities (Cronbach’s Alpha=0.86 and 0.88 for Anglo subscale and the Mexican subscale, respectively). The ARSMA-II yielded a Pearson correlation coefficient of r=0.89. This scale has been previously used in this population (Ghani, Delgadillo, et al., 2020; Ghani et al., 2021).

Statistical Analysis

Linear regression analyses examined associations between location of birth (born in Mexico or USA) as a binary predictor variable and each continuous sleep-related outcome variable, including PSQI score, ISI score, sleep duration (hours) and MAP sleep apnea risk score (percent).

Continuous variables were examined using linear regression. Binary variables (sleep apnea symptoms) were evaluated with binary logistic regression, and insomnia symptoms were evaluated with multinomial logistic regression, with “no symptoms” as reference. Covariates included age, sex, education. To examine whether observed relationships were explained by degree of Mexican and/or Anglo acculturation, separate models included acculturation score as an additional mediating variable. All analyses were completed using STATA 14.0 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX).

Results

Characteristics of the sample.

Characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 1. 66% of the surveyed population was born in Mexico. [Table 1 near here]. The mean age of the complete sample was 36.5 (SD 19.1), and 47% were female. A greater percentage of those born in the USA obtained a college degree, compared to those born in Mexico, although no significant differences were seen between the groups. No differences between age, sex, body mass index (BMI), sleep quality, insomnia severity, snoring, or gasping were seen between those born in the US and those born in Mexico. Of note, BMI data was calculated for 94 participants, as 6 respondents failed to provide either height or weight. Of the people born in Mexico, 55% completed measures in Spanish and of those born in the USA, 18% completed measures In Spanish. Individuals born in Mexico were more likely to fill out measures in Spanish (p<0.050). Significant group differences were found among those born in Mexico, having a higher Mexican acculturation scale score (p=0.008). Those born in the US had a higher Anglo acculturation score (p<0.0001). Univariate analyses showed that sleep duration was shorter among those born in USA (p=0.011), and those born in Mexico were more likely to report breathing pauses during sleep (p=0.023).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample

| Variable | Category/Units | Complete Sample | Born in Mexico | Born in USA | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 100 | 66 | 34 | ||

| Age | Years | 36.5 ± 19.1 | 36.7 ± 20.7 | 36.1 ± 15.7 | 0.866 |

| Sex | Female | 47.0% | 51.5% | 38.2% | 0.208 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | kg/m2 | 48.7 ± 6.1 | 29.7 ± 5.9 | 31.1 ± 6.4 | 0.287 |

| Education | College Graduate | 25.0% | 19.7% | 35.3% | 0.133 |

| Some College | 25.0% | 22.7% | 29.4% | ||

| High School | 23.0% | 24.2% | 20.6% | ||

| Less Than High School | 27.0% | 33.3% | 14.7% | ||

| Acculturation | Mexican | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 0.008 |

| Anglo | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | <0.0001 | |

| PSQI (Sleep Quality) | PSQI Score | 7.7 ± 3.5 | 7.3 ± 3.4 | 8.5 ± 3.5 | 0.115 |

| Sleep Duration | Hours | 6.1 ± 1.8 | 6.4 ± 1.8 | 5.5 ± 1.6 | 0.011 |

| Insomnia Severity | ISI Score | 9.1 ± 4.2 | 9.1 ± 4.0 | 9.3 ± 4.6 | 0.767 |

| Difficulty Falling Asleep | None | 31.0% | 34.9% | 23.5% | 0.307 |

| Mild | 37.0% | 39.4% | 32.4% | ||

| Moderate | 21.0% | 16.7% | 29.4% | ||

| Severe | 11.0% | 9.1% | 14.7% | ||

| Difficulty Staying Asleep | None | 36.0% | 40.9% | 26.5% | 0.400 |

| Mild | 25.0% | 25.8% | 23.5% | ||

| Moderate | 30.0% | 25.8% | 38.2% | ||

| Severe | 9.0% | 7.6% | 11.8% | ||

| Early Morning Awakenings | None | 36.0% | 34.9% | 38.2% | 0.493 |

| Mild | 25.0% | 21.2% | 32.4% | ||

| Moderate | 23.0% | 25.8% | 17.7% | ||

| Severe | 16.0% | 18.2% | 11.8% | ||

| Snoring | Yes | 68.8% | 69.8% | 66.7% | 0.750 |

| Gasping | Yes | 36.7% | 41.4% | 28.1% | 0.212 |

| Stop Breathing | Yes | 23.2% | 30.2% | 9.4% | 0.023 |

Place of Birth and Overall Sleep Duration and Quality

Results of regression analyses examining place of birth associated with PSQI score (and sleep duration item) are shown in Table 2 [Table 2 near here]. No relationship was seen with global PSQI score in unadjusted analyses however, in adjusted analyses we saw 1.65 higher PSQI score for those born in the USA, suggesting worse sleep quality. This relationship appears to be mediated by higher Anglo acculturation (p=0.377), but not Mexican acculturation (p= 0.041). Also, in unadjusted analyses, those born in US (vs Mexico) reported approximately 55 fewer minutes of sleep. This relationship was maintained after adjustment for covariates (and nominally increased to 1 hour and 2 minutes). This relationship was mediated by Anglo (p=0.124), but not Mexican acculturation (p= 0.020). No differences were seen across groups for overall ISI score.

Table 2.

Association between being born in the USA and sleep quality, overall insomnia severity, and sleep duration, N=34

| Outcome | Born in US | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | Duration (minutes) | 95% CI | P |

| Unadjusted | ||||

| PSQI Score | 1.2 | (−0.3, 2.6) | 0.112 | |

| Sleep Duration | −0.9 | −55 | (−1.6, −0.2) | 0.013 |

| ISI Score | 0.3 | (−1.5, 2.1) | 0.756 | |

| Adjusted (Age, Sex, Education) | ||||

| PSQI Score | 1.7 | (0.2, 3.2) | 0.031 | |

| Sleep Duration | −1.0 | −62 | (−1.8, −0.3) | 0.009 |

| ISI Score | 0.9 | (−1.0, 2.8) | 0.349 | |

| Adjusted + Mexican Acculturation | ||||

| PSQI Score | 1.6 | (0.1, 3.2) | 0.041 | |

| Sleep Duration | −0.9 | −54 | (−1.7, −0.1) | 0.020 |

| ISI Score | 0.8 | (−1.1, 2.8) | 0.398 | |

| Adjusted + Anglo Acculturation | ||||

| PSQI Score | 0.8 | (−0.9, 2.5) | 0.377 | |

| Sleep Duration | −0.7 | −42 | (−1.6, 0.2) | 0.124 |

| ISI Score | −0.6 | (−2.7, 1.5) | 0.579 | |

Place of Birth and Insomnia

The analysis in Table 3 [Table 3 near here] examines multinomial logistic regression, with insomnia symptom as dependent variable (mild, moderate, and severe, relative to none) and country of origin as independent variable (US, relative to Mexico), unadjusted, adjusted for covariates, and adjusted for both covariates and acculturation. In these analyses, the relative likelihood of those born in the US (vs Mexico) of reporting each symptom severity (vs none) is reported. Although no relationships were seen in unadjusted analyses, in adjusted analyses, those born in the US compared to those born in Mexico, were more likely to report severe difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep (relative to no difficulty). Specifically, those born in the US were 8.3 times as likely to report severe difficulty falling asleep (relative to no difficulty) and 11.2 times as likely to report severe difficulty staying asleep. These relationships were mediated by greater Anglo acculturation score (p=0.129, p=0.194, respectively).

Table 3.

Association between being born in the USA and insomnia symptoms, N=34

| Outcome | Born in US | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Unadjusted | ||||

| Difficulty Falling Asleep | None | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Mild | 1.2 | (0.4, 3.5) | 0.720 | |

| Moderate | 2.6 | (0.8, 8.5) | 0.109 | |

| Severe | 2.4 | (0.6, 10.0) | 0.232 | |

| Difficulty Staying Asleep | None | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Mild | 1.4 | (0.5, 4.4) | 0.550 | |

| Moderate | 2.3 | (0.8, 6.5) | 0.119 | |

| Severe | 2.4 | (0.5, 10.9) | 0.258 | |

| Early Morning Awakenings | None | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Mild | 1.4 | (0.5, 3.9) | 0.536 | |

| Moderate | 0.6 | (0.2, 2.0) | 0.423 | |

| Severe | 0.6 | (0.2, 2.2) | 0.433 | |

| Adjusted (Age, Sex, Education) | ||||

| Difficulty Falling Asleep | None | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Mild | 1.1 | (0.3, 3.5) | 0.926 | |

| Moderate | 1.9 | (0.5, 7.2) | 0.373 | |

| Severe | 8.3 | (1.2, 55.8) | 0.030 | |

| Difficulty Staying Asleep | None | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Mild | 1.3 | (0.4, 4.4) | 0.719 | |

| Moderate | 1.9 | (0.6, 6.2) | 0.309 | |

| Severe | 11.2 | (1.1, 118.0) | 0.045 | |

| Early Morning Awakenings | None | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Mild | 1.1 | (0.3, 3.5) | 0.913 | |

| Moderate | 0.6 | (0.2, 2.1) | 0.404 | |

| Severe | 0.6 | (0.1, 2.6) | 0.480 | |

| Adjusted + Mexican Acculturation | ||||

| Difficulty Falling Asleep | None | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Mild | 0.9 | (0.3, 3.0) | 0.865 | |

| Moderate | 1.6 | (0.4, 6.5) | 0.499 | |

| Severe | 7.2 | (1.0, 51.5) | 0.048 | |

| Difficulty Staying Asleep | None | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Mild | 1.2 | (0.3, 4.4) | 0.763 | |

| Moderate | 1.8 | (0.5, 6.2) | 0.346 | |

| Severe | 10.8 | (1.0, 115.6) | 0.049 | |

| Early Morning Awakenings | None | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Mild | 1.2 | (0.4, 4.2) | 0.726 | |

| Moderate | 0.6 | (0.4, 2.5) | 0.526 | |

| Severe | 0.6 | (0.1, 3.0) | 0.567 | |

| Adjusted + Anglo Acculturation | ||||

| Difficulty Falling Asleep | None | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Mild | 1.0 | (0.3, 4.0) | 0.993 | |

| Moderate | 1.1 | (0.2, 5.3) | 0.887 | |

| Severe | 5.1 | (0.6, 42.1) | 0.129 | |

| Difficulty Staying Asleep | None | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Mild | 0.9 | (0.2, 3.9) | 0.892 | |

| Moderate | 1.1 | (0.3, 4.6) | 0.852 | |

| Severe | 5.4 | (0.4, 68.3) | 0.194 | |

| Early Morning Awakenings | None | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Mild | 1.1 | (0.3, 4.3) | 0.912 | |

| Moderate | 0.7 | (0.1, 3.2) | 0.611 | |

| Severe | 0.5 | (0.1, 2.4) | 0.353 | |

Place of Birth and Sleep Apnea

Results of analyses of sleep apnea symptoms are reported in Table 4 [Table 4 near here]. In unadjusted analyses, those born in US were 80% less likely to report breathing pauses during sleep, compared to those born in Mexico. These relationships were maintained in adjusted analyses and did not appear to be mediated by acculturation scores.

Table 4.

Relationships between being born in the USA and sleep apnea symptoms, N=34

| Outcome | Born in US | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | oOR | 95% CI | P |

| Unadjusted | |||

| Snoring | 1.4 | (0.6, 3.0) | 0.427 |

| Gasping | 0.7 | (0.3, 1.7) | 0.430 |

| Stop Breathing | 0.2 | (0.1, 0.8) | 0.025 |

| Adjusted (Age, Sex, Education) | |||

| Snoring | 1.2 | (0.5, 2.7) | 0.652 |

| Gasping | 0.6 | (0.2, 1.5) | 0.253 |

| Stop Breathing | 0.2 | (0.0, 0.7) | 0.017 |

| Adjusted + Mexican Acculturation | |||

| Snoring | 1.3 | (0.6, 3.0) | 0.554 |

| Gasping | 0.9 | (0.3, 2.5) | 0.784 |

| Stop Breathing | 0.2 | (0.1, 1.0) | 0.049 |

| Adjusted + Anglo Acculturation | |||

| Snoring | 1.2 | (0.5, 2.9) | 0.750 |

| Gasping | 0.4 | (0.1, 1.1) | 0.066 |

| Stop Breathing | 0.2 | (0.0, 0.7) | 0.017 |

Discussion

This study examined the relationships between location of birth and several sleep parameters in a sample of adults of Mexican descent living at the US-Mexico border, and associations with degree of Mexican or Anglo acculturation. Overall findings of this study showed being born in the United States was associated with about one fewer hour of sleep per night and poorer sleep quality, mediated by greater Anglo acculturation but not Mexican acculturation. Additionally, differences between separate insomnia symptoms were seen, such that those born in the US were more likely to report severe difficulty falling asleep and difficulty staying asleep, also mediated by degree of Anglo acculturation. Lastly, we found that individuals born in US were 80% less likely to report breathing pauses during sleep, however this relationship was not mediated by either acculturation scores.

An interesting finding of this study was that being born in the US, when compared to being born in Mexico, was associated with one fewer hour of sleep per night, on average. Literature on location of birth and sleep have varying results. Our findings are similar to previous literature where we see foreign-born individuals living in the US had a 19% greater likelihood of sleeping 7–8h per night, when compared to US-born individuals (Newsome et al., 2017). Also, Americans born in Mexico had a greater likelihood of sleeping 7–8h per night, compared to those from Africa (Newsome et al., 2017). Additionally, individuals of Mexican descent born in Mexico are less likely to report short sleep, compared to those born in the US (Whinnery et al., 2014). Similarly, compared to US born non-Hispanic whites, foreign-born Mexican adults were less likely to report very short and short sleep duration (Gaston et al., 2021). However, our findings contrast with a more recent epidemiological study (Garcia et al., 2020) looking at sleep patterns among US Latinos by nativity and country of origin, using National Health and Interview Survey data from 2004–2017 (N=303,244). In that sample, foreign-born Mexicans were more likely to report short sleep duration relative to US-born Whites (OR: 1.08; 95% CI 1.01, 1.15), after accounting for various covariates. However, the magnitude of disadvantage relative to US-born Whites varied by Latino subgroups. Interestingly, all foreign-born groups (except for Mexicans) had an increased likelihood of reporting short sleep relative to US-born Whites, and US-born counterparts (Garcia et al., 2020). Reasons for the differences in findings may include methodology as our study utilized validated questionnaires to assess various sleep aspects. Lastly, location of study may also impact the differences, as our results were obtained from a city at the US-Mexico border where a majority of the individuals residing there in this region, identified as Mexican descent. The border may differ in many factors when compared to urban/suburban regions, which is where most epidemiological studies have been previously conducted.

Additionally, we found being born in the US was associated with worse sleep quality, supporting current literature. A brief communication by Hale and colleagues (Hale & Rivero-Fuentes, 2011) proposed that compared to Mexican immigrants, Mexican-Americans born in the US may be at increased risk of habitual short sleep duration, however no other sleep-related outcomes were available and authors did not further explore individual risk factors (e.g., cultural shift) that may impact the effect on the observed relationships. A population-based study assessing differences in sleep between Mexican-born immigrants living in the US compared to their US-born Mexican American counterpart and the general US population, revealed Mexican immigrants had a significant overall lower prevalence of poor sleep and sleep-related outcomes (Seicean et al., 2011); specifically, regression analysis showed Mexico-born immigrants living in the US had significantly reduced odds of short habitual sleep time, insomnia, and sleep associated disturbances (Seicean et al., 2011). Interestingly, despite Mexican immigrants having higher rates of poverty, lower rates of high school completion and higher rates of living with a partner, when compared to their US-born counterparts, they still presented with lower odds of sleep-related problems (Seicean et al., 2011). Lower socioeconomic status is usually linked to living in environments that may aggravate sleep disturbances, such as inconvenient light exposure, traffic noise, temperature, decreased feelings of safety, and increased levels of stress. A cross-sectional analysis performed in 2,156 US Hispanic/Latino adult participants from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos revealed the prevalence of short sleep, low sleep efficiency, and late sleep midpoint were all prevalent among those living in an unsafe neighborhood. Additionally, risk of sleeping <6 hours was greater in those living in an unsafe compared to a safe neighborhood (Simonelli et al., 2017). These findings may offer a unique opportunity to identify potentially modifiable mediating factors between the relationship of disadvantaged environments and sleep quality among Mexican immigrants living in the US. Our study did not assess for environmental factors and future studies should consider including a broader sociodemographic measurement strategy, especially at the US-border, as they may differ compared to urban and suburban areas.

Social cohesion and support among racial/ethnic minorities and the socioeconomically disadvantaged Hispanic communities may partially explain associations with sleep duration and quality. Although little research exists addressing social support and sleep quality, especially at the border, studies have found that positive mental and physical benefits are attenuated with a higher degree of familial support amongst Latino communities (Bird et al., 2001; J. M. Ruiz et al., 2013). It is reasonable to suggest culture and location of birth may contribute to societal cohesiveness and support, which may play a role in sleep health. The US-Mexico border provides a unique opportunity in public health to address the social determinants of health. The border region is a complex milieu of cultures, peoples, languages, and traditions; therefore, characterization of the border is complex. The social, cultural, economic, and political context provides the backdrop for the health and well-being of US border residents. Our study focused on individuals residing at the US-Mexico border and determined shorter sleep duration and poorer sleep quality as well as severe disturbances were associated with being born in the US and were mediated by Anglo acculturation. Similar to previous findings, Anglo acculturation has been reported to exacerbate sleep problems or prevent individuals from experiencing adequate sleep (Abraido-Lanza et al., 2005; Hale & Rivero-Fuentes, 2011; Voss & Tuin, 2008). Nearly half of Latinos in the US are foreign-born, which can be an important modifier that has implications for understanding the effects of place exposures on health.

Interestingly, the findings of this study support a concept called “Latino Mortality Paradox,” particularly among Latino immigrants to the US, where they arrive in the US with better health but the longer they live in the US, the more their health declines (Abraido-Lanza et al., 2005; J. M. Ruiz et al., 2013). This paradox exerts influence in the morbidity patterns that have been observed in the Latino population by country of origin (Borrell et al., 2011; Y. Chen et al., 2020; Garcia et al., 2018; Patel et al., 2015). Acculturation may partially explain the “Latino Mortality Paradox,” as prior research on Latinos has found that acculturation (Hale & Rivero-Fuentes, 2011), and ethnic stress, which are likely driven by the disadvantaged minority status of Latinos in the US, are associated with poor sleep (Alcantara et al., 2017). Of note, stress and health behaviors, specifically smoking, appeared to attenuate the relationship between sleep duration and acculturation, (Hale & Rivero-Fuentes, 2011). Several of our study’s findings were mediated by Anglo acculturation, suggesting adapting to a westernized culture leads to worse sleep outcomes. An important factor that was not assessed in the present study was the role of acculturative stress, which should be considered in future studies. As sleep is linked to chronic conditions (Grandner, Hale, et al., 2010), sleep can be a key physiological mechanism explaining group differences in health and these differences may influence specific stressors associated with minority status in the US that influence poor sleep.

Specifically, we found those born in the US were 8.3 times more likely to report severe difficulty falling asleep and 11.2 times more likely to report severe difficulties staying asleep, which was mediated by Anglo acculturation. These individual mediations (in addition to adjusted covariates age, sex, and education level) indicated evident relationships in acculturation and sleep, an area that can be further explored in its relation to sleep. An epidemiological study found that Mexican Americans and Mexican-born immigrants were less likely to report difficulty falling asleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, and early morning awakenings, after adjusting for covariates (Grandner et al., 2013). Additionally, non-Mexican Hispanic/Latinos were also less likely to report sleep disturbances and sleep apnea symptoms, compared to non-Hispanic whites. Further adjustment for birthplace and socioeconomics, revealed individuals born in Mexico were less likely than US-born respondents to report many sleep disturbances sleep maintenance difficulties, and snorting/snoring during sleep (Grandner et al., 2013). These individuals may be working jobs requiring long hours and hard labor, therefore leaving them tired enough to fall asleep quicker and experience higher levels of undisturbed sleep. Unfortunately, our study did not assess whether labor or types of jobs may have contributed to our findings. Although shift work was assessed in this study, there were too few respondents to perform any analysis. Therefore, future studies should include shift workers, as sleep disturbances due to shift work are common and predisposes individuals to chronic diseases (Jehan et al., 2017).

Another limitation is that we did not collect additional cultural information such as time spent with family, dinner times, work shift times, and naps. Compared to individualistic Anglo culture in the US, Latino culture is recognized as valuing cooperation, collectivism, and working together for the good of the group (Rodriguez & Olswang, 2003). It is possible individuals of immigrant status continue these practices exhibited in their home country while living in the US. By working together, they might minimize the tasks that need completion after work or at night, allowing them to experience better sleep patterns. Potential trends can be further investigated in association to not only where one was born, but the way one grew up including the individual’s behavior, practices, and philosophy. Looking into the aforementioned characteristics in contrast to the different dynamics of sleep has the potential to bring insight into how the two can be further correlated. Future studies should also assess other environmental, social and behavioral factors, (i.e., types of jobs, total hours working, quality of life, and psychosocial factors) and how they may impact sleep quality, sleep duration, sleep disturbances, in this population.

Lastly, looking at sleep apnea risk, we see that those born in the US were 80% less likely to report greater pauses in breathing throughout the night, when compared to those born in Mexico, after adjusting for covariates. Interestingly, this relationship was not mediated by Mexican or Anglo acculturation. In data examined from 16,415 Latinx(s) from HCHS/SOL (Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos), Redline and colleagues (Redline et al., 2014) found that although sleep symptoms and sleep duration varied amongst Latino subgroups, those who identified as being Mexican, reported the lowest incidences of “stop breathing,” independent of sex. Additionally, Redline and colleagues (Redline et al., 2014) found low rates of clinically recognized sleep apnea diagnoses in the Hispanic/Latino group. This finding has important implications, as the Hispanic/Latino population may disproportionately experience negative health consequences associated with impaired sleep, such as diabetes, hypertension and obesity (Daviglus et al., 2012). Li and colleagues (Li et al., 2021) also examined HCHS/SOL data finding that sleep disordered breathing (SDB) was associated with a 54% increased likelihood of hypertension and 33% increased likelihood of diabetes, with no differences in sex. Further, insomnia was associated with 37% increased likelihood of hypertension with greater association for men (Ghani, Begay, et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). Reasons for differences in our findings may be methodology and measurements of “stop of breathing” and assessments of comorbid health conditions. Because those born in Mexico were more likely to complete measures in Spanish, there is a possibility of a translation bias, which may partially explain the results we found. Other potential reasons for our findings might be due to better healthcare access as studies have shown USA born individuals have better access to healthcare facilities and insurance (Grandner et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2015). It would be interesting to assess factors why this may be the case among those born in the USA compared to those born in Mexico. Alternatively, looking at other borders and larger samples could allow us to see if nativity plays a unique role in reported pauses in breathing throughout the night or if this relationship is geographically influenced.

Limitations

There are several limitations worth noting. First, the sample size was small for a population-based study, as this sample was recruited as a convenience sample for a pilot study. Despite being one of the largest studies using validated measures conducted at a US-Mexico border, prevalence estimates, and associations need to be replicated in a larger sample size. Also, the cross-sectional nature of analysis prevents us from making inferences of causality.

Secondly, despite using validated instruments for sleep measures, they were self-reported which may be at risk for recall and reporting bias. Also, other information about sleep habits such as regularity of sleep schedule and naps were not assessed. More accurate measures such as prospective (e.g., sleep diary) and objective (e.g., actigraphy) measures were not available. We also did not collect details about medical histories (i.e., sleep disorders, sleep medications) or obtained medical records as they were not available at the time of the study. Future studies should obtain reliable medical records that may be useful to determine if the diagnosis of sleep disorders impact the results obtained in this study.

Thirdly, language acculturation has been previously demonstrated to influence sleep in Mexican immigrants (Hale et al., 2014; Heilemann et al., 2012) and could be considered a confounding variable. However, we did not include language spoken as a covariate in this study, therefore future studies should consider assessing the role of language and sleep in this population.

Of note, some of the results of Table 3 may be underpowered due to relatively small sample size, as could be noted by wide confidence intervals in some of the analyses. These results would need to be replicated in the future either using alternate analysis methods or larger sample sizes.

Also, the use of logistic regression in these cross-sectional analyses, where the sleep outcomes were not rare, may overestimate effects. Future studies in larger samples should use more robust methods.

Lastly, concern remains regarding that confounding may exist due to unmeasured or poorly measured factors, which is common in observational studies.

Conclusion

Overall, sleep duration and quality are essential in attaining and maintaining good health both physiologically and neurologically. These same sleep conditions can be and are often dependent on setting and interestingly, the environment an individual is born and raised in. This study analyzed potential associations between sleep and being Mexican or Mexican-American, particularly juxtaposing sleep duration and quality alongside the individual’s acculturation. These individuals consisted of 100 people within the city of Nogales, AZ age 18 and older. Three major trends were identified once the data was adjusted for covariates. Sleep duration was on average shorter for those born in the US, those born in the US reported fewer breathing pauses during sleep, and those born in the US were 8.3 times more likely to report difficulty falling asleep and 11.2 times more likely to report difficulty staying asleep. These relationships appear to be mediated by Anglo acculturation in US born Mexicans, however other social-environmental or biogenetic influences may be involved as well, especially at the border as border health disparities are important because there are socioenvironmental differences, when compared to urban or suburban locations.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Brooke Mason for her time, effort, creativity, and assistance in creating the abbreviated socioecological figure for this manuscript.

Funding:

This work was supported by the NIH under Grant R01DA051321; NIH under Grant R01MD011600; NIH under Grant T32HL007249; University of Arizona Health Sciences Grant.

Footnotes

Declarations

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Disclosure: I am reporting that MAG received grants from Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Kemin Foods, and consulting from Fitbit, Natrol, Merck, Casper, SPV, Merck, Sunovion, University of Maryland, and New York University. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study. OMB discloses that he received subcontract grants to Penn State from Proactive Life (formerly Mobile Sleep Technologies), doing business as SleepSpace (National Science Foundation grant #1622766 and NIH/National Institute on Aging Small Business Innovation Research Program R43AG056250, R44 AG056250); received honoraria/travel support for lectures from Boston University, Boston College, Tufts School of Dental Medicine, New York University, University of Miami, Harvard Chan School of Public Health, and Allstate; received consulting fees from SleepNumber; and receives an honorarium for his role as the Editor in Chief of Sleep Health sleephealthjournal.org. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study. SRP has received grant funding through his institution from Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Philips Respironics, Respicardia, and Sommetrics. He has served as a consultant for Bayer Pharmaceuticals and serves on the medical advisory board for NovaResp Technologies. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study. SP has received consulting fees from Jazz Pharmaceuticals; research grants to the institution from industry (Philips, Inc., Sommetrics, Inc., Verily Lifesciences, Inc., U.S. Biotest, Inc., and Regeneron, Inc.) and foundations (Sergei Brin Foundation, American Academy of Sleep Medicine Foundation). He has a U.S. patent that has been licensed to SaiOx, Inc. (United States Patent 10,758,700) for a home-based ventilation system that is not related to this manuscript.

Ethics Approval: The study procedure was performed in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the University of Arizona IRB (protocol # 1608763580) and informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Consent for publication: not applicable

Competing interests: not applicable

Availability of data and materials: not applicable

References

- Abraido-Lanza AF, Chao MT, & Florez KR (2005). Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation? Implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Soc Sci Med, 61(6), 1243–1255. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addison C, Jenkins B, White M, & LaVigne DA (2014). Sleep duration and mortality risk. Sleep, 37(8), 1279–1280. 10.5665/sleep.3910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia IB, Ford ES, Link M, & Bolen JC (2007). Acculturation, weight, and weight-related behaviors among Mexican Americans in the United States. Ethn Dis, 17(4), 643–649. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18072373 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcantara C, Patel SR, Carnethon M, Castaneda S, Isasi CR, Davis S, Ramos A, Arredondo E, Redline S, Zee PC, & Gallo LC (2017). Stress and Sleep: Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Sociocultural Ancillary Study. SSM Popul Health, 3, 713–721. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman NG, Izci-Balserak B, Schopfer E, Jackson N, Rattanaumpawan P, Gehrman PR, Patel NP, & Grandner MA (2012). Sleep duration versus sleep insufficiency as predictors of cardiometabolic health outcomes. Sleep Med, 13(10), 1261–1270. 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez GG, & Ayas NT (2004). The impact of daily sleep duration on health: a review of the literature. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs, 19(2), 56–59. 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2004.02422.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien CH, Vallieres A, & Morin CM (2001). Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med, 2(4), 297–307. 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker NB, Jesus SN, Joao K, Viseu JN, & Martins RIS (2017). Depression and sleep quality in older adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Health Med, 22(8), 889–895. 10.1080/13548506.2016.1274042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernert RA, Turvey CL, Conwell Y, & Joiner TE Jr. (2014). Association of poor subjective sleep quality with risk for death by suicide during a 10-year period: a longitudinal, population-based study of late life. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(10), 1129–1137. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Canino GJ, Davies M, Zhang H, Ramirez R, & Lahey BB (2001). Prevalence and correlates of antisocial behaviors among three ethnic groups. J Abnorm Child Psychol, 29(6), 465–478. 10.1023/a:1012279707372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell LN, Menendez BS, & Joseph SP (2011). Racial/ethnic disparities on self-reported hypertension in New York City: examining disparities among Hispanic subgroups. Ethn Dis, 21(4), 429–436. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22428346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, & Kupfer DJ (1989). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res, 28(2), 193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccio FP, Taggart FM, Kandala NB, Currie A, Peile E, Stranges S, & Miller MA (2008). Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Sleep, 31(5), 619–626. 10.1093/sleep/31.5.619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cespedes EM, Dudley KA, Sotres-Alvarez D, Zee PC, Daviglus ML, Shah NA, Talavera GA, Gallo LC, Mattei J, Qi Q, Ramos AR, Schneiderman N, Espinoza-Giacinto RA, & Patel SR (2016). Joint associations of insomnia and sleep duration with prevalent diabetes: The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). J Diabetes, 8(3), 387–397. 10.1111/1753-0407.12308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Wang R, Zee P, Lutsey PL, Javaheri S, Alcantara C, Jackson CL, Williams MA, & Redline S (2015). Racial/Ethnic Differences in Sleep Disturbances: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Sleep, 38(6), 877–888. 10.5665/sleep.4732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Freedman ND, Rodriquez EJ, Shiels MS, Napoles AM, Withrow DR, Spillane S, Sigel B, Perez-Stable EJ, & Berrington de Gonzalez A (2020). Trends in Premature Deaths Among Adults in the United States and Latin America. JAMA Netw Open, 3(2), e1921085. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar I, Arnold B, & Maldonado R (1995). Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA Scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavorial Sciences, 17(3), 275–304. [Google Scholar]

- Daviglus ML, Talavera GA, Aviles-Santa ML, Allison M, Cai J, Criqui MH, Gellman M, Giachello AL, Gouskova N, Kaplan RC, LaVange L, Penedo F, Perreira K, Pirzada A, Schneiderman N, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Sorlie PD, & Stamler J (2012). Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. JAMA, 308(17), 1775–1784. 10.1001/jama.2012.14517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Mendoza J, Rodriguez-Munoz A, Vela-Bueno A, Olavarrieta-Bernardino S, Calhoun SL, Bixler EO, & Vgontzas AN (2012). The Spanish version of the Insomnia Severity Index: a confirmatory factor analysis. Sleep Med, 13(2), 207–210. 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia C, Garcia MA, & Ailshire JA (2018). Sociocultural variability in the Latino population: Age patterns and differences in morbidity among older US adults. Demogr Res, 38, 1605–1618. 10.4054/DemRes.2018.38.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia C, Sheehan CM, Flores-Gonzalez N, & Ailshire JA (2020). Sleep Patterns among US Latinos by Nativity and Country of Origin: Results from the National Health Interview Survey. Ethn Dis, 30(1), 119–128. 10.18865/ed.30.1.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston SA, Martinez-Miller EE, McGrath J, Jackson Ii WB, Napoles A, Perez-Stable E, & Jackson CL (2021). Disparities in multiple sleep characteristics among non-Hispanic White and Hispanic/Latino adults by birthplace and language preference: cross-sectional results from the US National Health Interview Survey. BMJ Open, 11(9), e047834. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghani SB, Begay TK, & Grandner MA (2020). Sleep Disordered Breathing and Insomnia as Cardiometabolic Risk Factors Among US Hispanics/Latinos. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 10.1164/rccm.202008-3171ED [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghani SB, Delgadillo ME, Granados K, Okuagu AC, Alfonso-Miller P, Buxton OM, Patel SR, Ruiz J, Parthasarathy S, Haynes PL, Molina P, Seixas A, Williams N, Jean-Louis G, & Grandner MA (2020). Acculturation Associated with Sleep Duration, Sleep Quality, and Sleep Disorders at the US-Mexico Border. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 17(19). 10.3390/ijerph17197138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghani SB, Delgadillo ME, Granados K, Okuagu AC, Wills CCA, Alfonso-Miller P, Buxton OM, Patel SR, Ruiz J, Parthasarathy S, Haynes PL, Molina P, Seixas A, Jean-Louis G, & Grandner MA (2021). Patterns of Eating Associated with Sleep Characteristics: A Pilot Study among Individuals of Mexican Descent at the US-Mexico Border. Behav Sleep Med, 1–12. 10.1080/15402002.2021.1902814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould CE, Beaudreau SA, O’Hara R, & Edelstein BA (2016). Perceived anxiety control is associated with sleep disturbance in young and older adults. Aging Ment Health, 20(8), 856–860. 10.1080/13607863.2015.1043617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner MA, Hale L, Moore M, & Patel NP (2010). Mortality associated with short sleep duration: The evidence, the possible mechanisms, and the future. Sleep Med Rev, 14(3), 191–203. 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner MA, Jackson NJ, Pigeon WR, Gooneratne NS, & Patel NP (2012). State and regional prevalence of sleep disturbance and daytime fatigue. J Clin Sleep Med, 8(1), 77–86. 10.5664/jcsm.1668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner MA, Patel NP, Gehrman PR, Xie D, Sha D, Weaver T, & Gooneratne N (2010). Who gets the best sleep? Ethnic and socioeconomic factors related to sleep complaints. Sleep Med, 11(5), 470–478. 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner MA, Petrov ME, Rattanaumpawan P, Jackson N, Platt A, & Patel NP (2013). Sleep symptoms, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic position. J Clin Sleep Med, 9(9), 897–905; 905A–905D. 10.5664/jcsm.2990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner MA, Seixas A, Shetty S, & Shenoy S (2016). Sleep Duration and Diabetes Risk: Population Trends and Potential Mechanisms. Curr Diab Rep, 16(11), 106. 10.1007/s11892-016-0805-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner MA, Williams NJ, Knutson KL, Roberts D, & Jean-Louis G (2016). Sleep disparity, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic position. Sleep Med, 18, 7–18. 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale L, & Rivero-Fuentes E (2011). Negative acculturation in sleep duration among Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans. J Immigr Minor Health, 13(2), 402–407. 10.1007/s10903-009-9284-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale L, Troxel W, & Buysse DJ (2020). Sleep Health: An Opportunity for Public Health to Address Health Equity. Annu Rev Public Health, 41, 81–99. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale L, Troxel WM, Kravitz HM, Hall MH, & Matthews KA (2014). Acculturation and sleep among a multiethnic sample of women: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Sleep, 37(2), 309–317. 10.5665/sleep.3404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton TG, & Hagos R (2021). Race and the Healthy Immigrant Effect. Public Policy Aging Rep, 31(1), 14–18. 10.1093/ppar/praa042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilemann MV, Choudhury SM, Kury FS, & Lee KA (2012). Factors associated with sleep disturbance in women of Mexican descent. J Adv Nurs, 68(10), 2256–2266. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05918.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton A, & Skrutkowski M (2002). Translating instruments into other languages: development and testing processes. Cancer Nurs, 25(1), 1–7. 10.1097/00002820-200202000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean-Louis G, & Grandner M (2016). Importance of recognizing sleep health disparities and implementing innovative interventions to reduce these disparities. Sleep Med, 18, 1–2. 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jehan S, Zizi F, Pandi-Perumal SR, Myers AK, Auguste E, Jean-Louis G, & McFarlane SI (2017). Shift Work and Sleep: Medical Implications and Management. Sleep Med Disord, 1(2). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29517053 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DA, Jackson CL, Williams NJ, & Alcantara C (2019). Are sleep patterns influenced by race/ethnicity - a marker of relative advantage or disadvantage? Evidence to date. Nat Sci Sleep, 11, 79–95. 10.2147/NSS.S169312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachikis AB, & Breitkopf CR (2012). Predictors of sleep characteristics among women in southeast Texas. Womens Health Issues, 22(1), e99–109. 10.1016/j.whi.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann CN, Mojtabai R, Hock RS, Thorpe RJ Jr., Canham SL, Chen LY, Wennberg AM, Chen-Edinboro LP, & Spira AP (2016). Racial/Ethnic Differences in Insomnia Trajectories Among U.S. Older Adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 24(7), 575–584. 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.02.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawada T (2016). Sleep duration and coronary heart disease mortality. Int J Cardiol, 215, 110. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempler L, Sharpe L, Miller CB, & Bartlett DJ (2016). Do psychosocial sleep interventions improve infant sleep or maternal mood in the postnatal period? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev, 29, 15–22. 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsbury JH, Buxton OM, & Emmons KM (2013). Sleep and its Relationship to Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep, 7(5). 10.1007/s12170-013-0330-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letzen JE, Robinson M, Saletin J, Sheinberg R, Smith MT, & Campbell CM (2021). Racial disparities in sleep-related cardiac function in young, healthy adults: Implications for cardiovascular-related health. Sleep 10.1093/sleep/zsab164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Sotres-Alvarez D, Gallo LC, Ramos AR, Aviles-Santa L, Perreira KM, Isasi CR, Zee PC, Savin KL, Schneiderman N, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Sofer T, Daviglus M, & Redline S (2021). Associations of Sleep-disordered Breathing and Insomnia with Incident Hypertension and Diabetes. The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 203(3), 356–365. 10.1164/rccm.201912-2330OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maislin G, Pack AI, Kribbs NB, Smith PL, Schwartz AR, Kline LR, Schwab RJ, & Dinges DF (1995). A survey screen for prediction of apnea. Sleep, 18(3), 158–166. 10.1093/sleep/18.3.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS, & Rote S (2019). The Healthy Immigrant Effect and Aging in the United States and Other Western Countries. Gerontologist, 59(2), 205–214. 10.1093/geront/gny136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markwald RR, Melanson EL, Smith MR, Higgins J, Perreault L, Eckel RH, & Wright KP Jr. (2013). Impact of insufficient sleep on total daily energy expenditure, food intake, and weight gain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 110(14), 5695–5700. 10.1073/pnas.1216951110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Miller EE, Prather AA, Robinson WR, Avery CL, Yang YC, Haan MN, & Aiello AE (2019). US acculturation and poor sleep among an intergenerational cohort of adult Latinos in Sacramento, California. Sleep, 42(3). 10.1093/sleep/zsy246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM, Belleville G, Belanger L, & Ivers H (2011). The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep, 34(5), 601–608. 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozumdar A, & Liguori G (2011). Persistent increase of prevalence of metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults: NHANES III to NHANES 1999–2006. Diabetes Care, 34(1), 216–219. 10.2337/dc10-0879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsome V, Seixas A, Iwelunmor J, Zizi F, Kothare S, & Jean-Louis G (2017). Place of Birth and Sleep Duration: Analysis of the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Int J Environ Res Public Health, 14(7). 10.3390/ijerph14070738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SR, & Hu FB (2008). Short sleep duration and weight gain: a systematic review. Obesity (Silver Spring), 16(3), 643–653. 10.1038/oby.2007.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SR, Sotres-Alvarez D, Castaneda SF, Dudley KA, Gallo LC, Hernandez R, Medeiros EA, Penedo FJ, Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Ramos AR, Redline S, Reid KJ, & Zee PC (2015). Social and Health Correlates of Sleep Duration in a US Hispanic Population: Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Sleep, 38(10), 1515–1522. 10.5665/sleep.5036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrov ME, & Lichstein KL (2016). Differences in sleep between black and white adults: an update and future directions. Sleep Med, 18, 74–81. 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo RS, Yang M, Bliwise DL, Yaggi HK, & Araujo AB (2013). Racial and socioeconomic disparities in sleep and chronic disease: results of a longitudinal investigation. Ethn Dis, 23(4), 499–507. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24392615 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redline S, Sotres-Alvarez D, Loredo J, Hall M, Patel SR, Ramos A, Shah N, Ries A, Arens R, Barnhart J, Youngblood M, Zee P, & Daviglus ML (2014). Sleep-disordered breathing in Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds. The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 189(3), 335–344. 10.1164/rccm.201309-1735OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez BL, & Olswang LB (2003). Mexican-American and Anglo-American mothers’ beliefs and values about child rearing, education, and language impairment. Am J Speech Lang Pathol, 12(4), 452–462. 10.1044/1058-0360(2003/091) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz JM, Steffen P, & Smith TB (2013). Hispanic mortality paradox: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the longitudinal literature. Am J Public Health, 103(3), e52–60. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz JMH, H. A.; Mehl MR; O’Conner MF (2016). The Hispanic health paradox: From epidemiological phenomenon to contribution opportunities for psychological science. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 19(4), 462–476. [Google Scholar]

- Seicean S, Neuhauser D, Strohl K, & Redline S (2011). An exploration of differences in sleep characteristics between Mexico-born US immigrants and other Americans to address the Hispanic Paradox. Sleep, 34(8), 1021–1031. 10.5665/SLEEP.1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan CM, Frochen SE, Walsemann KM, & Ailshire JA (2019). Are U.S. adults reporting less sleep?: Findings from sleep duration trends in the National Health Interview Survey, 2004–2017. Sleep, 42(2). 10.1093/sleep/zsy221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonelli G, Dudley KA, Weng J, Gallo LC, Perreira K, Shah NA, Alcantara C, Zee PC, Ramos AR, Llabre MM, Sotres-Alvarez D, Wang R, & Patel SR (2017). Neighborhood Factors as Predictors of Poor Sleep in the Sueno Ancillary Study of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Sleep, 40(1). 10.1093/sleep/zsw025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorlie PD, Aviles-Santa LM, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Kaplan RC, Daviglus ML, Giachello AL, Schneiderman N, Raij L, Talavera G, Allison M, Lavange L, Chambless LE, & Heiss G (2010). Design and implementation of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann Epidemiol, 20(8), 629–641. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teodorescu M, Polomis DA, Gangnon RE, Consens FB, Chervin RD, & Teodorescu MC (2013). Sleep duration, asthma and obesity. J Asthma, 50(9), 945–953. 10.3109/02770903.2013.831871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomfohr LM, Schweizer CA, Dimsdale JE, & Loredo JS (2013). Psychometric characteristics of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in English speaking non-Hispanic whites and English and Spanish speaking Hispanics of Mexican descent. J Clin Sleep Med, 9(1), 61–66. 10.5664/jcsm.2342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. (2021). Quick Facts: Santa Cruz County, Arizona US Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Vijver FJ, & Hambleton RK (1996). Translating Tests: Some Practical Guidelines. European Psychologist, 1(2), 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Bixler EO, Chrousos GP, & Vela-Bueno A (2009). Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with a high risk for hypertension. Sleep, 32(4), 491–497. 10.1093/sleep/32.4.491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss U, & Tuin I (2008). Integration of immigrants into a new culture is related to poor sleep quality. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 6, 61. 10.1186/1477-7525-6-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whinnery J, Jackson N, Rattanaumpawan P, & Grandner MA (2014). Short and long sleep duration associated with race/ethnicity, sociodemographics, and socioeconomic position. Sleep, 37(3), 601–611. 10.5665/sleep.3508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams NJ, Grandne MA, Snipes A, Rogers A, Williams O, Airhihenbuwa C, & Jean-Louis G (2015). Racial/ethnic disparities in sleep health and health care: importance of the sociocultural context. Sleep Health, 1(1), 28–35. 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]