Abstract

The Epstein-Barr virus LMP2A protein was expressed in a human keratinocyte cell line, HaCaT, and effects on epithelial cell growth were detected in organotypic raft cultures and in vivo in nude mice. Raft cultures derived from LMP2A-expressing cells were hyperproliferative, and epithelial differentiation was inhibited. The LMP2A-expressing HaCaT cells were able to grow anchorage independently and formed colonies in soft agar. HaCaT cells expressing LMP2A were highly tumorigenic and formed aggressive tumors in nude mice. The LMP2A tumors were poorly differentiated and highly proliferative, in contrast to occasional tumors that arose from parental HaCaT cells and vector control cells, which grew slowly and remained highly differentiated. Animals injected with LMP2A-expressing cells developed frequent metastases, which predominantly involved lymphoid organs. Involucrin, a marker of epithelial differentiation, and E-cadherin, involved in the maintenance of intercellular contact, were downregulated in LMP2A tumors. Whereas activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway was not observed, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3-kinase)-dependent activation of the serine-threonine kinase Akt was detected in LMP2A-expressing cells and LMP2A tumors. Inhibition of this pathway blocked growth in soft agar. These data indicate that LMP2A greatly affects cell growth and differentiation pathways in epithelial cells, in part through activation of the PI3-kinase–Akt pathway.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a ubiquitous herpesvirus of the family Gammaherpesviridae. Primary infection occurs in the oropharyngeal epithelium, which is permissive for virus replication. Trafficking B lymphocytes are subsequently infected by progeny virions that go on to establish a lifelong latent infection in the B-cell compartment with periodic reactivation and reinfection of the oropharyngeal epithelium, virus release, and transmission of virus via the salivary route (27). EBV is associated with a number of human malignancies, such as Burkitt's lymphoma, Hodgkin's lymphoma, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease, and the epithelial cell malignancy nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) (27, 42, 44–46, 56). In EBV latency, only a subset of genes is expressed. Different types of latency can be distinguished according to the latent gene products expressed. In type I latency, characteristic of Burkitt's lymphoma, only the EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1), transcripts from the BamHI-A region of the genome (10), and the EBERs, small, nonpolyadenylated RNAs with an unknown function, are expressed. In B-cell lines immortalized by EBV in vitro, all latent genes are expressed, which include EBNA1 through -6, BamHI-A transcripts, EBERs, and three latent membrane proteins, LMP1, LMP2A, and LMP2B (latency III). The pattern of gene expression is more restricted in NPC, with expression of EBNA1, EBERs, BamHI-A transcripts, and the latent membrane proteins (latency II) (27).

LMP2A and -2B arise from two different promoters, and transcription proceeds across the fused terminal repeats of the viral episome (49). Whereas both proteins contains 12 transmembrane domains, only LMP2A has a 119-amino-acid cytoplasmic N terminus encoded by exon 1, which is unique to LMP2A. The role of LMP2A has been analyzed mainly in B cells, where it inhibits B-cell receptor signaling that would induce EBV lytic replication (32). The LMP2A amino terminus contains nine tyrosine residues, several of which are found in the context of phosphotyrosine-containing protein-protein interaction motifs. An immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) is found at tyrosines 74 and 85. ITAMs are characterized by the consensus sequence YXXL/I(X6–8)YXXL/I and are present in associated molecules of the B- and T-cell receptor signaling complexes, as well as the Fc receptor complexes (55; M. Reth, Letter, Nature 338:383–384, 1989). ITAMs, when phosphorylated by Src family kinases, serve as docking sites for the tandem SH2 domains of the tyrosine kinases Syk and ZAP70 in B and T cells, respectively. Activation of Syk in B cells lies upstream of multiple signal transduction events such as activation of phospholipase Cγ2 and subsequent stimulation of Ca2+ release from intracellular stores and activation of the Ras–mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade. LMP2A is phosphorylated by Src family kinases, Lyn and Fyn, in B cells, an event that depends on a YEEA motif found in the LMP2A N terminus that closely resembles the consensus sequence for Src SH2 domain interaction motifs, YEEI/L (11, 21, 23, 31). Binding of Lyn to this motif at tyrosine 112 subsequently leads to phosphorylation of the ITAM, which in turn is able to bind to and sequester Syk (22). Additionally, LMP2A binds to and is phosphorylated by the MAPK Erk1 (41). LMP2A interaction with components of the B-cell receptor (BCR) signal transduction cascade results in inhibition of these molecules and downstream processes in response to BCR stimulation (35, 37). In the absence of LMP2A expression, BCR engagement ultimately leads to the activation of transcription factors which are able to induce the expression of the EBV immediate-early genes BZLF1 and BRLF1, followed by induction of viral lytic replication (36). The negative regulation of BCR signals by LMP2A is thought to contribute to the maintenance of viral latency. Genetic analysis of LMP2A indicated that LMP2A is not required for B-cell transformation (33, 34). However, studies with LMP2A transgenic mice have demonstrated that LMP2A expression under certain circumstances enables B-cell survival (13).

Expression of both LMP2A and -2B has been detected in NPC, and nude-mouse-passaged NPC tumors and NPC patients have high antibody titers to both LMP2A and -2B, indicating that expression of the protein is important during some stage of progression to disease (9, 12, 29). To investigate the possible changes in epithelial cell behavior conferred upon LMP2A expression, LMP2A was expressed in a spontaneously immortalized human keratinocyte cell line, HaCaT (8). HaCaT cells retain their potential to terminally differentiate in response to various stimuli, such as growth in organotypic or suspension cultures, and have been used in vitro to model normal human squamous epithelium (52). In this study, LMP2A was expressed in HaCaT cells by retrovirus-mediated gene transfer and the phenotype of stable, LMP2A-expressing pools was analyzed in organotypic raft culture, in soft agar, and by subcutaneous injection into nude mice. The results indicate that LMP2A has potent transforming abilities in HaCaT cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Production of recombinant retroviruses.

The LMP2A cDNA, carboxy terminally tagged with a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope, was subcloned into the retroviral vector pBabe containing the puromycin resistance gene as a selectable marker. Human 293T kidney cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg of the vector pBabe or pBabe LMP2A, 1 μg of pGI-VSV-G (vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G envelope), and 1 μg of pGPZ9 (Moloney murine leukemia virus gag-pol). At 48 h after transfection, culture supernatant was harvested and clarified by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge at 16,000 × g and 4°C. HaCaT cells were transduced by incubation with retrovirus-containing 293T supernatant and Polybrene at 8 μg/ml overnight. Following transduction, the cells were split into dishes containing selection medium puromycin at 0.5 μg/ml). Stable colonies were pooled after 2 weeks of selection.

Raft cultures.

A 2.4-ml volume of rat tail collagen mixed with 3 × 105 normal human fibroblasts was reconstituted with 300 μl of 10× Dulbecco modified Eagle medium H (DMEM-H), 300 μl of 10× reconstitution buffer (2.2% NaHCO3, 50 mM NaOH, 200 mM HEPES [pH 7.3]), and 3 μl of 10 N NaOH and allowed to gel in tissue culture inserts (Falcon) overnight. HaCaT cells (106) were seeded on top of the gels and cultured submerged overnight to confluency. Confluent cultures were raised to the air-liquid interface and fed daily from below with RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics for 14 days. Rafts were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, paraffin embedded, and sectioned.

Soft agar assays.

Soft agar plates were prepared by pouring 7 ml of Bacto Agar medium (1 ml of 2× DMEM-H, 1 ml of fetal bovine serum, 0.1 ml of penicillin-streptomycin, 6.9 ml of 1× DMEM, 1 ml of 5% Bacto Agar in water), incubated at 39°C (the agar was preheated to 52°C before addition), into 60-mm-diameter dishes. The agar was allowed to solidify and overlaid with 2 ml of Bacto Agar medium containing 4.67 × 104 cells. The cultures were fed weekly with 0.5 ml of DMEM-H containing antibiotics for 3 weeks. In some experiments, the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3-kinase) inhibitor LY294002 was added to the agar medium to a concentration of 10 μM and replenished in DMEM-H upon feeding. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Tumorigenicity studies.

Parental HaCaT, vector control, and LMP2A-expressing cells were trypsinized, washed extensively with phosphate-buffered saline solution, and adjusted to a concentration of 5 × 106 cells in a 100-μl total volume. The cells were subcutaneously injected into 3- to 5-week-old nude mice, and the appearance of tumors was monitored. Mice were sacrificed when tumor volumes reached 1 cm3. For proliferation studies, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 50 mg of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) per kg of body weight three times at 20-min intervals prior to sacrifice. Tumors were divided and frozen for preparation of tissue lysates or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histological analysis. All animals were examined for the presence of metastases.

Preparation of tumor lysates and immunoblots.

Frozen tissues were homogenized in a Dismembrator (Braun) for 30 s and extracted with NP-40 lysis buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 20 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Equal amounts of protein were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to Immobilon P membranes (Millipore). Polyclonal anti-HA antibody and a monoclonal anti-involucrin antibody were obtained from Santa Cruz and Sigma, respectively. The anti-active Akt antibody (New England Biolabs) recognizes phosphorylation of serine 473 and was used at a dilution of 1:1,000. Detection of total Akt was performed with a polyclonal antibody obtained from New England Biolabs and used at a dilution of 1:1,000. A monoclonal anti-E-cadherin antibody was purchased from Upstate Biotechnologies and used at a dilution of 1:2,500. Wortmannin was added for 30 min at a concentration of 0.1 μM to inhibit PI3-kinase in vitro.

Immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed with the LSAB+ immunohistochemistry kit (DAKO) in accordance with the manufacturer's specifications. For all stains, epitope retrieval by digestion with trypsin was performed prior to application of the primary antibody. The anti-involucrin monoclonal antibody was used at a dilution of 1:50. HA stains were performed with a polyclonal antibody at a 1:40 dilution. BrdU incorporation was detected with a BrdU staining kit (Oncogene Research Products) used in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS

LMP2A expression in HaCaT cells.

The LMP2A cDNA, tagged with an HA epitope at the C terminus, was subcloned into the retroviral expression vector pBabe containing the puromycin resistance gene to allow selection of transduced cells. Infectious replication-deficient recombinant virus was produced by transient transfection into human 293T cells together with the gag-pol and env genes (VSV-G). HaCaT cells were transduced with retrovirus-containing 293T cell culture supernatant, and infected cells were selected for puromycin resistance. Resistant cells were pooled and assayed for LMP2A expression by anti-HA Western blotting (see below). Pools expressing the highest levels of LMP2A were used for future studies.

Characteristics of LMP2A-expressing HaCaT cells in organotypic raft cultures.

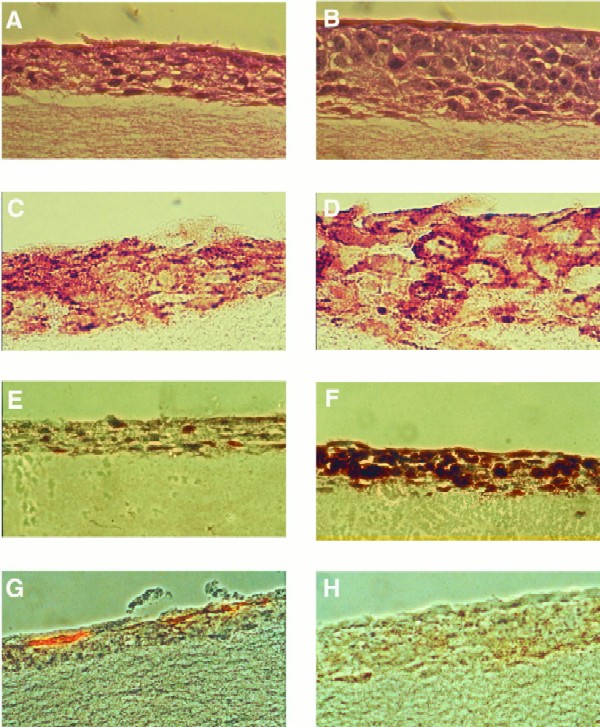

The organotypic raft culture system has been used as an in vitro model for squamous epithelial cell differentiation (2). Epithelial cells are seeded onto a collagen gel containing feeder fibroblasts and grown under submerged conditions. When confluence is reached, the cells are lifted to the air-liquid interface and fed from below through the collagen-fibroblast layer. Over the course of 14 to 21 days, the epithelial cells form multiple layers and exhibit characteristics of differentiated epithelia such as the formation of nonproliferating suprabasal layers, upregulation of proteins of the cornified envelope, and specific distribution of keratins. HaCaT cells have previously been examined for their behavior in organotypic culture and exhibit many features of normal stratified epithelium when cultured under these conditions (52). Raft cultures derived from LMP2A-expressing HaCaT cells showed a morphology strikingly different from that of vector control rafts. The LMP2A-expressing rafts were thickened and the cells were more rounded with large nuclei in comparison to the flattened appearance of vector control cells (Fig. 1A and B). Enucleated cells were detectable in the most suprabasal layers of vector control rafts only. To confirm that the cells retained LMP2A expression under these culture conditions, immunohistochemical analysis was performed. While only background staining was detected with anti-HA antibodies in the vector control rafts, a discrete membrane-staining pattern, suggestive of LMP2A, was evident in LMP2A-expressing rafts in all cell layers (Fig. 1C and D). These data indicate that LMP2A was expressed throughout the time in culture and in the suprabasal layers.

FIG. 1.

Characterization of HaCaT cell organotypic raft cultures. Hematoxylin-eosin stains of vector control (A) and LMP2A-expressing (B) HaCaT rafts are shown. LMP2A rafts are thickened with rounded cells containing large nuclei. Cells in vector control rafts are flattened, and enucleated cells are evident in the top layers of the culture. LMP2A expression was detected in the plasma membrane of cells in all layers of the epithelium using a rabbit HA antiserum and a biotin-streptavidin-peroxidase detection system (DAKO) (D). Background staining is evident in vector control rafts (C). Cell proliferation was determined by BrdU incorporation and staining with an anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody. Single BrdU-positive cells were observed in vector control rafts (E), while LMP2A-expressing rafts were highly proliferative (F). Localization of proliferating cells was not restricted to the basal cell layer. LMP2A blocks cell differentiation. The differentiation marker involucrin was present in the topmost layers of the epithelium of vector control rafts (G) but was not detected in LMP2A-expressing rafts (H).

To determine if the overall thickening of the LMP2A-expressing raft cultures reflected an increased rate of proliferation, vector control and LMP2A-expressing rafts were labeled with BrdU prior to harvesting and BrdU incorporation was monitored by immunohistochemistry assay to detect DNA-synthesizing cells (Fig. 1E and F). Single scattered BrdU-positive cells were detected in the vector control cultures, whereas the number of proliferating cells was greatly increased in the LMP2A-expressing rafts. In addition, the proliferating cells were not restricted to the basal cell layer, as expected for normal differentiated epithelia, but were present in all cell layers.

LMP2A inhibits epithelial cell differentiation.

To determine possible effects of LMP2A expression on epithelial cell differentiation, the expression of markers of differentiation was examined. Involucrin, a suprabasal precursor protein of the cornified envelope, is expressed in stratified keratinizing epithelia and is indicative of squamous differentiation (4, 54). Involucrin expression was detected in the upper two layers of vector control epithelium but was not observed in the LMP2A-expressing rafts (Fig. 1G and H). These data, together with the absence of enucleated cells in the top layers of LMP2A-expressing rafts and the presence of proliferating suprabasal cells, demonstrate that LMP2A expression interferes with the ability of epithelial cells to differentiate.

LMP2A expression in HaCaT cells confers anchorage independence.

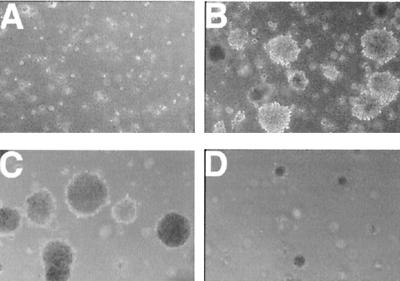

The ability to grow independently of attachment to a matrix is a hallmark of malignantly transformed cells. Therefore, parental, vector control, and LMP2A-expressing HaCaT cells were tested for the ability to grow in soft agar. LMP2A-expressing cells rapidly formed numerous colonies after approximately 1 week in culture, whereas vector control cells and parental cells did not grow (Fig. 2A and B). Three independently established pools of LMP2A-expressing HaCaT cells infected with separately prepared virus stocks tested positive for anchorage independence. Parental HaCaT cells and three independently established pools of vector control cells were reproducibly unable to grow in soft agar. Representative results of an experiment conducted in triplicate are presented in Table 1. The colonies were counted in five random microscopic fields at low magnification for each cell line.

FIG. 2.

LMP2A-expressing HaCaT cells are anchorage independent. Vector control or LMP2A-expressing cells (6.7 × 104) were cultured in soft agar for 3 weeks. Vector control cells formed only small clumps of cells (A). Efficient colony formation was detected only in the HaCaT LMP2A cells (B). Growth in soft agar is PI3-kinase dependent. Colony formation was inhibited with a significant decrease in colony size in dishes treated with the PI3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 at 10 μM (D) but not in dimethyl sulfoxide-treated control dishes (C).

TABLE 1.

Summary of soft agar assay results and tumorigenicity dataa

| Cell type | No. of colonies in soft agar | No. of tumors/no. of mice | Time of appearanceb | No. of animals with metastases/total | Organs or area involved (no. of mice) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental HaCaT | 0 | 1/3 | >8 | 0/3 | None |

| HaCaT vector | 0 | 3/6 | >8 | 0/6 | None |

| LMP2A HaCaT | 206 | 18/18 | 1–2 | 10/18 | Mesenteric and subhepatic LNc (10), abdomen (1) |

Vector control and LMP2A-expressing HaCaT cells were cultured in soft agar for 3 weeks, and colonies were counted in five random microscopic fields at ×5 magnification. Tumor formation was assayed after subcutaneous injection of cells into nude mice. Of the animals injected with LMP2A-expressing cells, 55% developed metastases involving mainly lymphoid tissues. Several animals had multiple-organ involvement.

Weeks postinjection.

LN, lymph nodes.

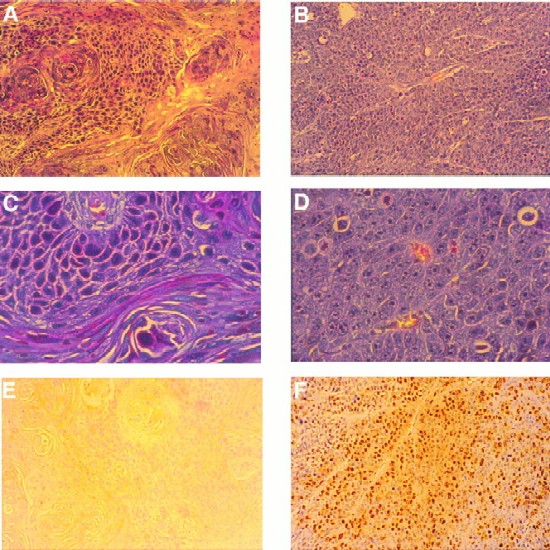

Tumorigenicity in nude mice.

The altered properties of HaCaT LMP2A cells observed in organotypic culture and the ability to grow in soft agar suggested that these cells were transformed. To determine whether LMP2A expression confers tumorigenicity, parental HaCaT, vector control, and LMP2A-expressing cells were injected subcutaneously into nude mice. LMP2A-expressing cells rapidly formed tumors in all of the animals 1 to 2 weeks postinjection, while vector control and parental HaCaT cells were significantly less tumorigenic (Table 1). One out of three animals injected with parental HaCaT cells and three out of six animals injected with vector control cells developed small tumors more than 8 weeks after injection. The LMP2A-negative tumors grew slowly and remained small. Hematoxylin-eosin stains of tumor sections revealed homogeneous cell morphology in the LMP2A-induced tumors with pale-staining pleomorphic nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant mitotic figures (Fig. 3B and D). Evidence of squamous differentiation with polarized basal and suprabasal flattened cells was not observed. In contrast, a tumor formed by parental HaCaT cells was well differentiated with polarized cells, obvious squamous differentiation, abundant keratin expression, and well-developed keratin pearls (Fig. 3A and C). HaCaT vector control cells also formed well-differentiated tumors (data not shown). The overall appearance of the LMP2A tumors strikingly resembled poorly differentiated or nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinomas similar to NPC. Interestingly, the LMP2A tumors were highly vascularized, containing abundant blood vessels, in contrast to the parental tumors.

FIG. 3.

LMP2A expression induces tumorigenicity in nude mice. Hematoxylin-eosin stains of tumor sections of a parental tumor (A and C) and an LMP2A-induced tumor (B and D) are shown. Parental or LMP2A-expressing HaCaT cells (5 × 106) were injected subcutaneously into nude mice. The parental tumor, which appeared >8 weeks postinjection, was well differentiated, with a distinction between polarized and squamous cells. Abundant keratin whorls were detected. LMP2A tumors, which appeared after 1 to 2 weeks, were poorly differentiated. The cells contained large pleomorphic nuclei with distinct nucleoli. Blood vessels were abundant. No signs of differentiation were detected. (E and F) LMP2A-induced tumors were highly proliferative. Prior to sacrifice, animals were injected three times with BrdU at 50 mg/kg of body weight at 20-min intervals. Proliferating cells in the parental tumor (E) and the LMP2A tumor (F) were detected with an anti-BrdU antibody. Approximately 20 to 30% of the cells in LMP2A tumors stained positive for BrdU. Magnifications, A, B, E, and F, ×20; C and D, ×80.

The rapid appearance of LMP2A tumors suggested a highly proliferative phenotype. Actively proliferating cells were labeled by intraperitoneal injection of BrdU into animals prior to sacrifice and detected by immunohistochemical staining of tumor sections (Fig. 3E and F). On average, approximately 20 to 30% of the cells in LMP2A tumors and up to 50% of the cell population in certain areas of the tumors stained positive for BrdU incorporation while BrdU staining was undetectable in the HaCaT parental tumor, confirming the differences observed in raft cultures and the difference in growth rate between LMP2A and control tumors. These data suggest that LMP2A expression induces tumorigenicity in HaCaT cells. In agreement with the data obtained with the organotypic raft cultures, LMP2A-expressing HaCaT cells were impaired in the ability to differentiate and were highly proliferative in vivo.

LMP2A tumors are metastatic.

The rapidity with which LMP2A tumors appeared soon after injection suggested a very aggressive malignant phenotype. Therefore, animals with tumors were examined for the presence of metastases. Approximately 55% of the animals had lymph node metastases. Mesenteric and subhepatic lymph nodes, but not cervical lymph nodes, were primarily affected. One animal had a highly vascularized abdominal mass (Table 1). Metastatic tissues were highly proliferative with a high percentage of cells staining positive for BrdU incorporation (data not shown). Histological examination of metastatic tissues revealed complete replacement of lymphoid tissue with epithelial cells (data not shown). In some animals, the tumors invaded the abdominal cavity through the adjacent muscle and connective tissues. These results illustrate the aggressive phenotype of LMP2A-induced tumors in nude mice, which might provide an excellent in vitro model system with which to study mechanisms of metastasis.

Molecular analysis of LMP2A tumors.

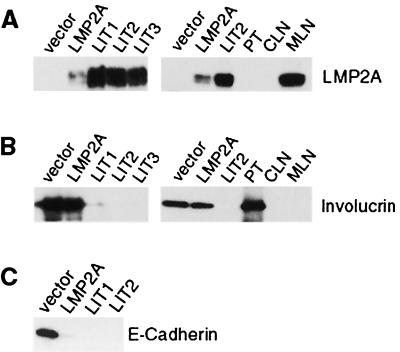

To confirm that LMP2A expression was retained during growth in vivo, its expression in tumors, HaCaT vector control cells, and HaCaT LMP2A-expressing cells grown in vitro was determined by immunoblot analysis. The level of LMP2A expression was strikingly elevated in LMP2A tumors compared to that in cells grown in tissue culture, suggesting that selection for cells expressing high levels of LMP2A occurred during tumor formation (Fig. 4A). The levels of LMP2A in the tumor cells were also considerably higher than in a single EBV-infected cord blood cell line (data not shown). However, levels of LMP2A expression can vary significantly between individual lymphoblastoid cell lines (41). As expected, LMP2A was absent from the parental tumor and was expressed at high levels in a metastatic mesenteric lymph node but not in an unaffected cervical lymph node.

FIG. 4.

Immunoblot analysis of tumor lysates. (A) LMP2A expression detected with anti-HA polyclonal serum. Tumors expressed high levels of LMP2A (LIT1 to 3). LMP2A expression was not detected in a tumor arising form parental HaCaT cells (PT) or in a normal cervical lymph node (CLN). In contrast, a metastatic mesenteric lymph node (MLN) expressed high levels of LMP2A. (B) Involucrin expression detected with a mouse monoclonal antibody. Expression of involucrin was greatly decreased in LMP2A tumors, whereas fairly high levels were observed in both LMP2A and vector control cells in tissue culture. (C) LMP2A-expressing cells and tumors lose expression of E-cadherin. E-cadherin was detected by immunoblotting.

Involucrin expression in both the parental HaCaT cells and the LMP2A tumors was analyzed as a marker of cell differentiation (Fig. 4B). In tissue culture, vector control and LMP2A-expressing HaCaT cells expressed considerable amounts of involucrin. In contrast, involucrin levels were greatly decreased in all of the LMP2A tumors examined while the parental tumor retained a high level of involucrin expression. Involucrin expression was not detected in the metastatic or unaffected lymph nodes. These data confirm results obtained in organotypic culture, where involucrin expression was also decreased in LMP2A-expressing cells.

Cadherins are a class of cell surface molecules predominantly involved in maintaining cell-cell contact through adherens junctions. There have been numerous reports of altered levels of cadherin expression in human cancers (5, 7). Cadherins are required for intercellular contact and the maintenance of epithelial integrity. Loss of cadherin expression is often correlated with increased invasion and is found predominantly in poorly differentiated tumors, whereas differentiated carcinomas often retain normal levels of cadherin expression. Expression of E-cadherin was examined by immunoblot assay of lysates from vector control and LMP2A-expressing HaCaT cells, as well as tumor lysates. Interestingly, E-cadherin was readily detectable only in HaCaT vector control cells and not in LMP2A-expressing cells grown in vitro or in LMP2A tumors (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that downregulation of cadherin expression is involved in the pronounced metastatic behavior of LMP2A tumors.

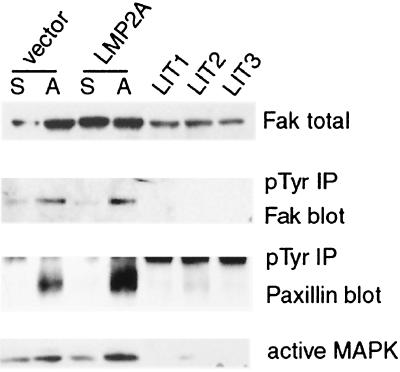

Cell adhesion signaling and MAPK pathways are not activated in LMP2A tumors.

A previous study indicated that LMP2A became phosphorylated upon plating onto extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins (50). Integrin-ECM interactions lead to activation of the focal adhesion kinase Fak and also to subsequent activation of the MAPK pathway (28). MAPK is activated by both integrin and growth factor signaling and is an important signal transduction pathway involved in cell proliferation and survival (30, 50). Therefore, it was important to determine if these pathways are affected by LMP2A expression. Detection of total Fak expression revealed that its levels are decreased in LMP2A tumors compared to vector control and LMP2A-expressing cells in culture (Fig. 5, top panel). Fak becomes phosphorylated on tyrosine when activated, and the levels of phosphorylated Fak increased upon fibronectin stimulation in both vector control and LMP2A-expressing cells. However, phosphorylated Fak was not detected in the LMP2A tumors, suggesting that this pathway was not activated by LMP2A expression in vivo (Fig. 5, second panel). This was confirmed by investigation of the phosphorylation status of the cytoskeletal protein paxillin, a substrate of Fak and Src. Tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin was readily stimulated by adhesion of tissue culture cells to fibronectin but was not detected in LMP2A tumors (Fig. 5, third panel). In addition, activation of MAPKs, as illustrated by ERK2, could be stimulated in vitro in both LMP2A-expressing and vector control cells, while activated ERK1 and ERK2 were not detected in the LMP2A tumors (Fig. 5, bottom panel). These data indicate that LMP2A expression does not inhibit integrin-mediated Fak activation, nor is Fak or MAPK activated as a component of the transformed, tumorigenic phenotype.

FIG. 5.

LMP2A does not activate cell adhesion signaling or the MAPK pathway. Levels of focal adhesion kinase, Fak, expression in whole-cell extracts of the vector control, LMP2A-expressing cells, and tumors (LIT) are shown in the top panel. Phosphotyrosine (pTyr) immunoprecipitation (IP) from lysates of suspended (S) or adherent (A) fibronectin-stimulated cells and tumor lysates, followed by Fak and paxillin blotting, is shown in the second and third panels. Cell adhesion stimulates Fak and paxillin phosphorylation. Neither Fak nor paxillin was phosphorylated significantly in LMP2A tumors. MAPK activation was detected with an antibody recognizing the dually phosphorylated activated form. Cell adhesion to fibronectin stimulated ERK2, whereas neither ERK1 nor ERK2 was activated in LMP2A tumors (bottom panel).

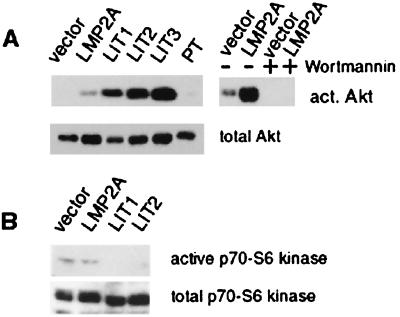

LMP2A activates PI3-kinase–Akt signaling.

LMP2A has been shown to affect the PI3-kinase pathway in B lymphocytes (35). The regulatory 85-kDa regulatory subunit of PI3-kinase is constitutively phosphorylated to higher levels in LMP2A-expressing B cells; however, increased activation of PI3-kinase by BCR signaling is blocked by LMP2A. Activation of the PI3-kinase pathway leads to phosphorylation and activation of Akt, a serine-threonine kinase which is implicated in activation of NFκB and inhibition of apoptosis (14, 15, 17, 20, 25, 40, 47). Although the levels of Akt protein were similar in the control and LMP2A-expressing cell lines, activated Akt was detected only in LMP2A-expressing cells (Fig. 6A). Similar to the increased levels of LMP2A in the tumors, considerably elevated levels of activated Akt were detected in the LMP2A tumors, with no activated Akt in the parental tumor. Wortmannin, a PI3-kinase inhibitor, completely blocked Akt activation in both vector control and LMP2A-expressing cells in vitro, confirming that Akt activation is mediated through PI3-kinase in these cells. In addition, a second specific inhibitor of PI3-kinase, LY294002, significantly decreased the overall number and size of HaCaT LMP2A colonies formed in soft agar (Fig. 2C and D). These data indicate that LMP2A activation of Akt is mediated by PI3-kinase and suggest that the altered growth properties, manifested by anchorage-independent growth, are dependent on PI3-kinase activation.

FIG. 6.

LMP2A expression activates Akt in a PI3-kinase-dependent fashion. (A) Immunoblot analysis with an antibody recognizing the activated form, phosphorylated on serine 473 (top). Akt activity is higher in LMP2A-expressing tissue culture cells and LMP2A tumors than in vector control cells. No activated (act.) Akt is detectable in a parental tumor (PT). PI3-kinase inhibition by wortmannin treatment for 30 min prior to harvesting of the cells leads to inhibition of Akt activity. Akt is expressed at similar levels in all of the cells and tissues examined (bottom). (B) Ribosomal S6 kinase is not activated by LMP2A expression. Tissue culture cell and LMP2A tumors (LIT) were analyzed by immunoblotting with an antibody that recognized the phosphorylated activated form of S6 kinase (top). S6 kinase levels are similar in all of the cells and tissues examined (bottom).

Akt activation involves both lipid second messengers and phosphorylation events. Phosphoinositols created by PI3-kinase bind to the pleckstrin homology domain of Akt, targeting it to the membrane, where phosphorylation of positive regulatory sites at threonine 308 and serine 473 occurs (20). One of the kinases implicated in positive regulation of Akt is 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1, which is activated through the PI3-kinase pathway (1). 3-Phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 also activates the ribosomal protein S6 kinase, a key regulator of the biosynthesis of components of the protein translation machinery (1, 3, 18). To determine if activation of PI3-kinase induces the activation of S6 kinase, S6 kinase was identified on immunoblots using antibodies that recognize the phosphorylated activated form. A low level of activated S6 kinase was observed in vector control and LMP2A-expressing HaCaT cells but was not detected in LMP2A tumors (Fig. 6B). These data indicate that not all PI3-kinase dependent pathways are activated by LMP2A and that Akt seems to be selectively targeted.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here reveal that LMP2A is able to induce epithelial cell transformation. LMP2A-expressing HaCaT cells formed hyperplastic, undifferentiated raft cultures, readily formed colonies in soft agar, and induced the formation of aggressive, poorly differentiated, and metastatic tumors in nude mice. Another EBV latent membrane protein, LMP1, has been shown to induce tumorigenicity and transformation of primary rodent fibroblasts and to inhibit differentiation of a squamous carcinoma cell line, SCC12F, in organotypic culture (16). However, LMP1-expressing HaCaT cells formed well-differentiated tumors in SCID mice and terminal differentiation in suspension culture was not inhibited by LMP1 (39). In addition, LMP1 HaCaT cell tumors appeared slowly 6 to 8 weeks postinjection, in contrast to LMP2A-expressing HaCaT cells, which formed aggressive metastatic neoplasms 1 to 2 weeks after inoculation. The LMP2A tumors were also poorly differentiated, in contrast to LMP1-induced HaCaT tumors. The same undifferentiated phenotype observed in organotypic culture suggests that inhibition of differentiation is an important consequence of LMP2A expression in epithelial cells. Inhibition of differentiation and thickening of the suprabasal layers by LMP2A have also recently been observed in another immortalized keratinocyte cell line, FEP 1811, in organotypic culture (19).

Histologically, the LMP2A tumors were similar to unkeratinizing or poorly differentiated NPC tumors. LMP2A tumors were surprisingly metastatic, with an incidence of approximately 55%. Metastases were restricted mainly to lymphoid organs, involving lymph nodes adjacent to the site of inoculation. This is very similar to NPC, where 75 to 80% of patients initially present with cervical lymph node metastases. It is interesting that signs of invasion into the matrix were not evident in organotypic culture, suggesting that other factors, such as paracrine signaling in the animal, might contribute to the development of metastases. Furthermore, the noted loss of cadherin expression in tumor tissue points to a possible mechanism by which cells lose their adhesion to neighboring cells, allowing them to break away from the primary tumor and invade through the ECM, thereby initiating the metastatic process. It is also interesting that LMP2A-expressing HaCaT cells expressed considerable amounts of involucrin in tissue culture and that involucrin levels were greatly decreased during tumor formation. In contrast, cadherin expression was lost in LMP2A-expressing tissue culture cells prior to tumor formation. This loss of cadherin expression may also contribute to the inhibition of cell differentiation.

The MAPK cascade, one of the major proliferative signal transduction pathways, was not activated in LMP2A-expressing cells or tumors, whereas PI3-kinase-dependent activation of Akt, a molecule that has been implicated in the inhibition of apoptosis and in NFκB activation, was observed. Some of the effects mediated by Akt include phosphorylation of Bad and phosphorylation of the forkhead transcription factor (FKHR). Phosphorylated Bad binds to 14-3-3 proteins, which prevents formation of proapoptotic Bad/Bcl-2 or Bad/BclXL heterodimers (24, 57). The forkhead family of transcription factors plays a pivotal role in the regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation. It has been shown that Akt phosphorylates FKHR1, an event that prevents FKHR1 entry into the nucleus (6). A potential link between Akt activation and differentiation has also been implied (48). Ribosomal S6 kinase is important in the control of the cellular protein translation machinery and has been linked to the control of cell proliferation (18). Although activation of both Akt and S6 kinase is PI3-kinase dependent (43), S6 kinase was not activated significantly in LMP2A-expressing tissue culture cells and its activated form was not detected in LMP2A tumors. This finding indicates that PI3-kinase-dependent activation of Akt by LMP2A is uncoupled from S6 kinase activation. Elucidation of the mechanism of this differential regulation will provide important insight into the control of PI3-kinase signaling and its downstream effectors. While this work was in progress, LMP2A-mediated activation of Akt in B cells was also detected (R. Longnecker, personal communication). As HaCaT is an immortalized cell line, it is likely that the activation of Akt by LMP2A, in combination with other genetic changes unique to HaCaT cells, contributes to the aggressive tumorigenic phenotype of these cells. Continued study of LMP2A-expressing HaCaT cells will identify the critical events and activated pathways that result in striking changes in growth properties, tumorigenicity, and metastasis.

We had previously shown that LMP2A interacts with epithelial cell ECM signaling pathways in epithelial cells and that signaling molecules different from those in B cells functionally interact with LMP2A in epithelial cells (51). It is possible that signaling events elicited by integrin engagement lead to LMP2A phosphorylation and that LMP2A modulates some component of integrin signaling. A recent study demonstrated that PI3-kinase activation by the α6β4 integrin leads to an invasive phenotype (53), and adhesion of epithelial cells to their ECM leads to protection from apoptosis through activation of PI3-kinase–Akt signaling (26). Constitutively active PI3-kinase has been shown to allow cells to grow anchorage independently (38). Constitutive activation of this pathway by LMP2A is likely critical to the anchorage-independent growth of LMP2A-expressing HaCaT cells. This is supported by the finding that the PI3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 was able to potently inhibit colony formation in soft agar.

The data presented here indicate that LMP2A dramatically affects epithelial cell growth and differentiation and that these effects are in part mediated through activation of the PI3-kinase–Akt pathway. LMP2A expression is consistently detected in NPC, and the similarity of the HaCaT LMP2A tumors to NPC suggests that LMP2A also affects epithelial cell differentiation and growth properties in vivo. It is important to determine to how LMP2A contributes to the characteristic properties of NPC and to identify the signaling pathways that are affected.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Natalie Edmund for excellent assistance with the animal experiments.

This work was supported by NIH grant CA 32979 to N.R.-T.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alessi D R, Kozlowski M T, Weng Q P, Morrice N, Avruch J. 3-Phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1) phosphorylates and activates the p70 S6 kinase in vivo and in vitro. Curr Biol. 1998;8:69–81. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assilineau D, Prunieras M. Reconstruction of ‘simplified’ skin: control of fabrication. Br J Dermatol. 1984;111:219–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1984.tb15608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balendran A, Currie R, Armstrong C G, Avruch J, Alessi D R. Evidence that 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 mediates phosphorylation of p70 S6 kinase in vivo at Thr-412 as well as Thr-252. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37400–37406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banks-Schlegel S, Green H. Involucrin synthesis and tissue assembly by keratinocytes in natural and cultured human epithelia. J Cell Biol. 1981;90:732–737. doi: 10.1083/jcb.90.3.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behrens J. Cadherins and catenins: role in signal transduction and tumor progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1999;18:15–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1006200102166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biggs W H, 3rd, Meisenhelder J, Hunter T, Cavenee W K, Arden K C. Protein kinase B/Akt-mediated phosphorylation promotes nuclear exclusion of the winged helix transcription factor FKHR1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7421–7426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birchmeier W, Behrens J. Cadherin expression in carcinomas: role in the formation of cell junctions and the prevention of invasiveness. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1198:11–26. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boukamp P, Petrussevska R T, Breitkreutz D, Hornung J, Markham A, Fusenig N E. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:761–771. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.3.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brooks L, Yao Q Y, Rickinson A B, Young L S. Epstein-Barr virus latent gene transcription in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells: coexpression of EBNA1, LMP1, and LMP2 transcripts. J Virol. 1992;66:2689–2697. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2689-2697.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks L A, Lear A L, Young L S, Rickinson A B. Transcripts from the Epstein-Barr virus BamHI A fragment are detectable in all three forms of virus latency. J Virol. 1993;67:3182–3190. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3182-3190.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burkhardt A L, Bolen J B, Kieff E, Longnecker R. An Epstein-Barr virus transformation-associated membrane protein interacts with src family tyrosine kinases. J Virol. 1992;66:5161–5167. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.5161-5167.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Busson P, McCoy R, Sadler R, Gilligan K, Tursz T, Raab-Traub N. Consistent transcription of the Epstein-Barr virus LMP2 gene in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Virol. 1992;66:3257–3262. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.3257-3262.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caldwell R G, Wilson J B, Anderson S J, Longnecker R. Epstein-Barr virus LMP2A drives B cell development and survival in the absence of normal B cell receptor signals. Immunity. 1998;9:405–411. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80623-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardone M H, Roy N, Stennicke H R, Salvesen G S, Franke T F, Stanbridge E, Frisch S, Reed J C. Regulation of cell death protease caspase-9 by phosphorylation. Science. 1998;282:1318–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Datta S R, Dudek H, Tao X, Masters S, Fu H, Gotoh Y, Greenberg M E. Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell. 1997;91:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawson C W, Rickinson A B, Young L S. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein inhibits human epithelial cell differentiation. Nature. 1990;344:777–780. doi: 10.1038/344777a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.del Peso L, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Page C, Herrera R, Nunez G. Interleukin-3-induced phosphorylation of BAD through the protein kinase Akt. Science. 1997;278:687–689. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dufner A, Thomas G. Ribosomal S6 kinase signaling and the control of translation. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:100–109. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farwell D G, McDougall J K, Coltrera M D. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane proteins leads to changes in keratinocyte cell adhesion. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108:851–859. doi: 10.1177/000348949910800906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franke T F, Kaplan D R, Cantley L C, Toker A. Direct regulation of the Akt proto-oncogene product by phosphatidylinositol-3,4-bisphosphate. Science. 1997;275:665–668. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fruehling S, Lee S K, Herrold R, Frech B, Laux G, Kremmer E, Grässer F A, Longnecker R. Identification of latent membrane protein 2A (LMP2A) domains essential for the LMP2A dominant-negative effect on B-lymphocyte surface immunoglobulin signal transduction. J Virol. 1996;70:6216–6226. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6216-6226.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fruehling S, Longnecker R. The immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif of Epstein-Barr virus LMP2A is essential for blocking BCR-mediated signal transduction. Virology. 1997;235:241–251. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fruehling S, Swart R, Dolwick K M, Kremmer E, Longnecker R. Tyrosine 112 of latent membrane protein 2a is essential for protein tyrosine kinase loading and regulation of Epstein-Barr virus latency. J Virol. 1998;72:7796–7806. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7796-7806.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu S Y, Kaipia A, Zhu L, Hsueh A J. Interference of BAD (Bcl-xL/Bcl-2-associated death promoter)-induced apoptosis in mammalian cells by 14-3-3 isoforms and P11. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:1858–1867. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.12.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kane L P, Shapiro V S, Stokoe D, Weiss A. Induction of NF-κB by the Akt/PKB kinase. Curr Biol. 1999;9:601–604. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80265-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khwaja A, Rodriguez-Viciana P, Wennstrom S, Warne P H, Downward J. Matrix adhesion and Ras transformation both activate a phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase and protein kinase B/Akt cellular survival pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16:2783–2793. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus and its replication. In: Fields B, Knipe D, Howley P, editors. Fields virology. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 2343–2396. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kornberg L, Earp H S, Parsons J T, Schaller M, Juliano R L. Cell adhesion or integrin clustering increases phosphorylation of a focal adhesion-associated tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23439–23442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lennette E T, Winberg G, Yadav M, Enblad G, Klein G. Antibodies to LMP2A/2B in EBV-carrying malignancies. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:1875–1878. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00354-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin T H, Aplin A E, Shen Y, Chen Q, Schaller M, Romer L, Aukhil I, Juliano R L. Integrin-mediated activation of MAP kinase is independent of FAK: evidence for dual integrin signaling pathways in fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:1385–1395. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.6.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longnecker R, Druker B, Roberts T M, Kieff E. An Epstein-Barr virus protein associated with cell growth transformation interacts with a tyrosine kinase. J Virol. 1991;65:3681–3692. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3681-3692.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Longnecker R, Miller C L. Regulation of Epstein-Barr virus latency by latent membrane protein 2. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:38–42. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)81504-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Longnecker R, Miller C L, Miao X-Q, Marchini A, Kieff E. The only domain which distinguishes Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2A (LMP2A) from LMP2B is dispensable for lymphocyte infection and growth transformation in vitro; LMP2A is therefore nonessential. J Virol. 1992;66:6461–6469. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6461-6469.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Longnecker R, Miller C L, Tomkinson B, Miao X-Q, Kieff E. Deletion of DNA encoding the first five transmembrane domains of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane proteins 2A and 2B. J Virol. 1993;67:5068–5074. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.5068-5074.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller C L, Burkhardt A L, Lee J H, Stealey B, Longnecker R, Bolen J B, Kieff E. Integral membrane protein 2 of Epstein-Barr virus regulates reactivation from latency through dominant negative effects on protein-tyrosine kinases. Immunity. 1995;2:155–166. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(95)80040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller C L, Lee J H, Kieff E, Longnecker R. An integral membrane protein (LMP2) blocks reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus from latency following surface immunoglobulin crosslinking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:772–776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller C L, Longnecker R, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2A blocks calcium mobilization in B lymphocytes. J Virol. 1993;67:3087–3094. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3087-3094.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moore S M, Rintoul R C, Walker T R, Chilvers E R, Haslett C, Sethi T. The presence of a constitutively active phosphoinositide 3-kinase in small cell lung cancer cells mediates anchorage-independent proliferation via a protein kinase B- and p70s6k-dependent pathway. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5239–5247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicholson L J, Hopwood P, Johannessen I, Salisbury J R, Codd J, Thorley-Lawson D, Crawford D H. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein does not inhibit differentiation and induces tumorigenicity of human epithelial cells. Oncogene. 1997;15:275–283. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozes O N, Mayo L D, Gustin J A, Pfeffer S R, Pfeffer L M, Donner D B. NF-κB activation by tumour necrosis factor requires the Akt serine-threonine kinase. Nature. 1999;401:82–85. doi: 10.1038/43466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Panousis C G, Rowe D T. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2 associates with and is a substrate for mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Virol. 1997;71:4752–4760. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4752-4760.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pathmanathan R, Prasad U, Sadler R, Flynn K, Raab-Traub N. Clonal proliferations of cells infected with Epstein-Barr virus in preinvasive lesions related to nasopharyngeal carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:693–698. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199509143331103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pullen N, Dennis P B, Andjelkovic M, Dufner A, Kozma S C, Hemmings B A, Thomas G. Phosphorylation and activation of p70s6k by PDK1. Science. 1998;279:707–710. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5351.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raab-Traub N. Epstein-Barr virus infection in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Infect Agents Dis. 1992;1:173–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raab-Traub N, Flynn K. The structure of the termini of the Epstein-Barr virus as a marker of clonal cellular proliferation. Cell. 1986;47:883–889. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90803-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raab-Traub N, Flynn K, Klein C, Pizza G, De Vinci C, Occhiuzzi L, Farneti G, Caliceti U, Pirodda E. EBV associated malignancies. J Exp Pathol. 1987;3:449–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Romashkova J A, Makarov S S. NF-κB is a target of AKT in anti-apoptotic PDGF signalling. Nature. 1999;401:86–90. doi: 10.1038/43474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rommel C, Clarke B A, Zimmermann S, Nunez L, Rossman R, Reid K, Moelling K, Yancopoulos G D, Glass D J. Differentiation stage-specific inhibition of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway by Akt. Science. 1999;286:1738–1741. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sample J, Liebowitz D, Kieff E. Two related Epstein-Barr virus membrane proteins are encoded by separate genes. J Virol. 1989;63:933–937. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.2.933-937.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schlaepfer D D, Hanks S K, Hunter T, van der Geer P. Integrin-mediated signal transduction linked to Ras pathway by GRB2 binding to focal adhesion kinase. Nature. 1994;372:786–791. doi: 10.1038/372786a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scholle F, Longnecker R, Raab-Traub N. Epithelial cell adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins induces tyrosine phosphorylation of the Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2: a role for C-terminal Src kinase. J Virol. 1999;73:4767–4775. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4767-4775.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schoop V M, Mirancea N, Fusenig N E. Epidermal organization and differentiation of HaCaT keratinocytes in organotypic coculture with human dermal fibroblasts. J Investig Dermatol. 1999;112:343–353. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shaw L M, Rabinovitz I, Wang H H, Toker A, Mercurio A M. Activation of phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase by the α6β4 integrin promotes carcinoma invasion. Cell. 1997;91:949–960. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80486-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Watt F M. Involucrin and other markers of keratinocyte terminal differentiation. J Investig Dermatol. 1983;81:100s–103s. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12540786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weiss A, Littman D R. Signal transduction by lymphocyte antigen receptors. Cell. 1994;76:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Young L S, Dawson C W, Clark D, Rupani H, Busson P, Tursz T, Johnson A, Rickinson A B. Epstein-Barr virus gene expression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:1051–1065. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-5-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zha J, Harada H, Yang E, Jockel J, Korsmeyer S J. Serine phosphorylation of death agonist BAD in response to survival factor results in binding to 14-3-3 not BCL-XL. Cell. 1996;87:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]