This systematic review and meta-analysis investigates clinical outcomes and postdischarge treatment after acute coronary syndromes or revascularization among people living with HIV.

Key Points

Question

What are the postdischarge outcomes for patients living with HIV after acute coronary syndromes or coronary revascularization?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 studies involving 9499 patients living with HIV and 1 531 117 patients without HIV, patients living with HIV had a higher risk of all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events, recurrent acute coronary syndromes, and admission for heart failure after the index event, despite being approximately 11 years younger at the time of the event. Patients living with HIV were more likely to be current smokers and engage in illicit drug use and had higher triglyceride and lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels than those without HIV.

Meaning

This analysis highlights the need for attention toward secondary prevention strategies to address poor outcomes of cardiovascular disease among patients living with HIV.

Abstract

Importance

Clinical outcomes after acute coronary syndromes (ACS) or percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) in people living with HIV have not been characterized in sufficient detail, and extant data have not been synthesized adequately.

Objective

To better characterize clinical outcomes and postdischarge treatment of patients living with HIV after ACS or PCIs compared with patients in an HIV-negative control group.

Data Sources

Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science were searched for all available longitudinal studies of patients living with HIV after ACS or PCIs from inception until August 2023.

Study Selection

Included studies met the following criteria: patients living with HIV and HIV-negative comparator group included, patients presenting with ACS or undergoing PCI included, and longitudinal follow-up data collected after the initial event.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data extraction was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement. Clinical outcome data were pooled using a random-effects model meta-analysis.

Main Outcome and Measures

The following clinical outcomes were studied: all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events, cardiovascular death, recurrent ACS, stroke, new heart failure, total lesion revascularization, and total vessel revascularization. The maximally adjusted relative risk (RR) of clinical outcomes on follow-up comparing patients living with HIV with patients in control groups was taken as the main outcome measure.

Results

A total of 15 studies including 9499 patients living with HIV (pooled proportion [range], 76.4% [64.3%-100%] male; pooled mean [range] age, 56.2 [47.0-63.0] years) and 1 531 117 patients without HIV in a control group (pooled proportion [range], 61.7% [59.7%-100%] male; pooled mean [range] age, 67.7 [42.0-69.4] years) were included; both populations were predominantly male, but patients living with HIV were younger by approximately 11 years. Patients living with HIV were also significantly more likely to be current smokers (pooled proportion [range], 59.1% [24.0%-75.0%] smokers vs 42.8% [26.0%-64.1%] smokers) and engage in illicit drug use (pooled proportion [range], 31.2% [2.0%-33.7%] drug use vs 6.8% [0%-11.5%] drug use) and had higher triglyceride (pooled mean [range], 233 [167-268] vs 171 [148-220] mg/dL) and lower high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (pooled mean [range], 40 [26-43] vs 46 [29-46] mg/dL) levels. Populations with and without HIV were followed up for a pooled mean (range) of 16.2 (3.0-60.8) months and 11.9 (3.0-60.8) months, respectively. On postdischarge follow-up, patients living with HIV had lower prevalence of statin (pooled proportion [range], 53.3% [45.8%-96.1%] vs 59.9% [58.4%-99.0%]) and β-blocker (pooled proportion [range], 54.0% [51.3%-90.0%] vs 60.6% [59.6%-93.6%]) prescriptions compared with those in the control group, but these differences were not statistically significant. There was a significantly increased risk among patients living with HIV vs those without HIV for all-cause mortality (RR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.32-2.04), major adverse cardiovascular events (RR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.01-1.22), recurrent ACS (RR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.12-2.97), and admissions for new heart failure (RR, 3.39; 95% CI, 1.73-6.62).

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings suggest the need for attention toward secondary prevention strategies to address poor outcomes of cardiovascular disease among patients living with HIV.

Introduction

The widespread use of effective antiretroviral therapies (ARTs) has led to increased survivorship among people living with HIV. Therefore, people living with HIV are experiencing an increased prevalence of age-related disease, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD).1,2 The increase in CVD in this population has been attributed to multiple factors, including increasing age, the increase in burden of traditional CVD factors and psychosocial risk factors, the long-term metabolic effects of ART, and the low-grade immune activation of chronic HIV.1,3,4,5,6,7,8

Epidemiological studies have shown that compared with populations without HIV, people living with HIV have a higher risk of coronary artery disease, acute coronary syndromes (ACS), and heart failure, with onset at younger ages.4,9,10,11,12 Given this earlier emergence of CVD among people living with HIV, there has been significant attention and evidence generated for primary prevention strategies involving statins.13,14 In conjunction with these studies, characterization of longitudinal CVD outcomes is important to identify strategies for secondary prevention and further improve survivorship among people living with HIV. Studies on clinical outcomes after ACS and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) among patients living with HIV have shown higher rates of recurrent coronary disease and mortality compared with patients in HIV-negative control groups.11,15,16,17 However, this association has not been characterized in sufficient detail in current literature, and extant data have not been adequately synthesized. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies of patients living with HIV after ACS or PCIs to better characterize clinical outcomes and postdischarge treatment compared with patients in HIV-negative control groups.

Methods

We report this systematic review and meta-analysis according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline. This study was not preregistered. Please see the eMethods in Supplement 1 for a detailed description of methods used in this meta-analysis, as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

Search and Extraction

We searched Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science for all available articles from inception to August 2023 for the key terms coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, non-fatal myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, revascularization, percutaneous coronary intervention, and secondary prevention. We also reviewed references of relevant articles.

Articles were screened by 2 reviewers (M.H. and M.C.) by title and abstract and later by full text. We included studies if they fulfilled the following criteria: patients living with HIV and a comparator group of patients without HIV (control group) included, patients with obstructive coronary artery disease presenting with ACS or undergoing revascularization through PCI included, and longitudinal follow-up data on clinical outcomes after initial event collected. We initially also searched for studies that discussed outcomes after stroke and peripheral artery disease.

We extracted the following data where available using standardized forms: study characteristics, baseline demographics (ie, age, sex, and race and ethnicity) and other characteristics (ie, underlying comorbidities, revascularization strategies, and postdischarge medications) of HIV-positive and HIV-negative control populations, HIV-specific characteristics (use of ART, CD4 count, and viral load), number of events by group and hazard ratios (HRs) of clinical outcomes (ie, all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events [MACE], cardiovascular death, recurrent ACS, stroke, total lesion revascularization, total vessel revascularization, and admission for heart failure). We extracted maximally adjusted HRs where available, as well as unadjusted (crude) or minimally adjusted HRs for clinical outcomes. We captured data on race and ethnicity to help assess the full scope of diversity among patients living with HIV and how applicable our data may be within the global population of people living with HIV. Race and ethnicity were self-reported in the study by Shitole et al.18 In the other studies reporting this information, data were obtained from review of medical records, including electronic health records. Reported race and ethnicity categories included African American, American Indian, Asian, Hispanic, Pacific Islander, White, and other. We primarily report aggregated data for Black, White, and Hispanic populations only given that there were limited data available on other races and ethnicities.

Statistical Analysis

We combined summary study characteristics (eg, mean age, percentage male and female, percentage Black and White, and percentage Hispanic) across studies using study sizes as analytical weights to provide estimates of pooled means or percentages. The δ and P values comparing summary study-level characteristics (means or prevalences pooled across studies) between HIV-positive and HIV-negative groups were calculated from a linear regression model of each variable on HIV status weighted by the number of participants for each study (ie, a fixed-effects meta-regression). When HRs were not reported, we calculated crude risk ratios from the number of events in each group. In 2 studies,15,19 data were reported as odds ratios. We pooled HRs of clinical outcomes across studies using a random-effects model meta-analysis, estimating between-study heterogeneity using the DerSimonian-Laird method.20 As a sensitivity analysis, we also estimated between-study heterogeneity using the residual maximum likelihood method and calculated variances (P values and CIs) of pooled relative risk (RR) estimates using modifications proposed by Knapp and Hartung.21 For the purpose of the meta-analysis, we considered odds ratios, risk ratios, and HRs as equivalent measures of RR.

We assessed between-study heterogeneity using the Cochran Q statistic and I2 statistic, which estimates the percentage of total variation across studies due to true between-study difference rather than chance.22,23 We did not explore heterogeneity further owing to the limited numbers of studies available for most comparisons.

The quality of included studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort studies.24 We visually inspected funnel plots to assess the risk of publication bias. We also performed the Egger test for small study bias, although this was limited by the small number of studies that were generally available for investigated outcomes. Where there were P values trending toward small study bias, we performed trim and fill analyses to help assess the impact of the bias on pooled estimates (even if Egger test P values did not reach statistical significance). A 2-sided P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant. For the meta-analysis of RRs, we report point estimates and 95% CIs. All analyses were performed using Stata software statistical software version 15 (StataCorp).

Results

An initial search yielded 3263 studies, which were screened using titles, abstracts, and full texts. Studies reviewing patient outcomes after diagnoses and interventions of peripheral artery disease and stroke were limited, reporting mainly in-hospital outcomes, short-term follow-up, or results without non-HIV comparator groups, and were not further considered in this meta-analysis. We identified 15 studies11,15,16,18,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 of post-ACS or revascularization outcomes from 2003 to 2023 that met inclusion criteria (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). Of identified studies, 2 were abstracts.30,31 All were retrospective cohort studies except for 3 prospective studies (Table 1).11,26,30

Table 1. Study Characteristics, Patient Characteristics, and Outcomes.

| Characteristic | Study | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matetzky et al,26 2003 | Hsue et al,34 2004 | Ren et al,27 2009 | Lorgis et al,15 2013 | Carballo et al,16 2015 | Badr et al,32 2015 | Jeon et al,25 2017 | Mandal et al,31 2017 | Cua et al,30 2014 | Marcus et al,29 2019 | Boccara et al,11 2020 | Shitole et al,18 2020 | Postigo et al,28 2020 | Parks et al,33 2021 | Parikh et al35 2023 | |

| Study date | 1998-2000 | 1993-2003 | 2000-2007 | 2005-2009 | 2005-2011 | 2003-2011 | 2002-2014 | 2003-2016 | 2002-2010 | 1996-2010 | 2003-2006 | 2008-2014 | 2000-2018 | 2014-2016 | 2009-2019 |

| Study design | PC | COS | RC | RC | RC | COS | RC | COS | PC | RC | PC | RC | RC | COS | RC |

| Population source | Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles | San Francisco General Hospital | California Pacific Medical Center | PMSI database in France | Swiss HIV Cohort Study | MedStar Washington | Ontario HIV databases | Rural Kolkata, India | Veterans Aging Cohort | Kaiser Permanente | 23 CCUs in France | Montefiore Hospital, NY | Gregorio Maranon Hospital, Madrid, Spain | Symphony Health data warehouse | VA Healthcare System |

| Patients, No. | |||||||||||||||

| Control | 48 | 68 | 97 | 1216 | 5328 | 112 | 259 475 | 32 | 1564 | 86 321 | 195 | 1152 | 184 | 1 118 514 | 56 811 |

| HIV | 24 | 68 | 97 | 608 | 133 | 112 | 345 | 32 | 479 | 226 | 103 | 22 | 92 | 6612 | 546 |

| Age, mean, y | |||||||||||||||

| Control | 48 | 61 | 54 | 50 | 64 | 58 | 69.4 | 42.0 | NA | 67 | 50 | 60 | 51.3 | 67.4 | 67.1 |

| HIV | 47.0 | 50 | 53 | 50 | 51 | 58 | 54.4 | 49 | NA | 54 | 48 | 50 | 51.3 | 57.4 | 63.0 |

| Sex,% | |||||||||||||||

| Male | |||||||||||||||

| Control | 87.5 | 61.7 | 100 | 88.6 | 72.2 | 64.3 | 61.7 | 87.5 | NA | 63 | 94.3 | 66.7 | 92.4 | 59.7 | 98.1 |

| HIV | 87.5 | 89.7 | 100 | 88.6 | 85.0 | 64.3 | 87.0 | 93.8 | NA | 94 | 93.2 | 72.7 | 92.4 | 71.2 | 98.9 |

| Female | |||||||||||||||

| Control | 12.5 | 38.2 | 0 | 11.4 | 27.8 | 35.7 | 38.3 | 12.5 | NA | 37 | 5.7 | 33.3 | 7.6 | 40.3 | 1.9 |

| HIV | 12.5 | 10.3 | 0 | 11.4 | 15.0 | 35.7 | 13.0 | 6.2 | NA | 6 | 6.8 | 27.3 | 7.6 | 28.8 | 1.1 |

| Race and ethnicity, % | |||||||||||||||

| Black | |||||||||||||||

| Control | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 21.4 | NA | NA | NA | 6.5 | NA | 20.3 | NA | 2.5 | 14.0 |

| HIV | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 62.5 | NA | NA | NA | 15 | NA | 22.7 | NA | 7.0 | 34.8 |

| Hispanic | |||||||||||||||

| Control | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.7 | NA | 36.3 | NA | 3.8 | NA |

| HIV | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.4 | NA | 54.6 | NA | 8.2 | NA |

| White | |||||||||||||||

| Control | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 68 | NA | 23.1 | NA | 14.3 | 83.7 |

| HIV | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 64 | NA | 9.1 | NA | 7.2 | 63.4 |

| Outcomes, No. | |||||||||||||||

| MACE | |||||||||||||||

| Control | NA | NA | 29 | NA | 1078 | 19 | NA | 1 | 451 | NA | 39 | 425 | 30 | NA | 9910 |

| HIV | 2 | NA | 32 | NA | 20 | 28 | NA | 3 | 143 | NA | 22 | 11 | 17 | NA | 121 |

| Death | |||||||||||||||

| Control | NA | NA | 2 | NA | 135 | 12 | NA | NA | 73 | 16 401 | NA | 185 | 7 | 114 933 | 4373 |

| HIV | NA | NA | 3 | NA | 5 | 17 | NA | NA | 35 | 35 | NA | 3 | 6 | 724 | 57 |

Abbreviations: CCUs, coronary care unit; COS, comparative observational study; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; NA, not available; PC, prospective cohort; PMSI, Programme de Médicalisation des Systèm’s d'Information; RC, retrospective cohort; VA, Veterans Affairs.

Details of patient characteristics and outcomes by study are presented in Table 1 and eTable 1 in Supplement 1. A total of 9499 patients living with HIV (pooled proportion [range], 76.4% [64.3%-100%] male; pooled mean [range] age, 56.2 [47.0-63.0] years; pooled proportion [range], 10.1% [95% CI, 7.0%-62.5%] Black; 8.1% [95% CI, 0.4%-54.6%] Hispanic, and 13.1% [95% CI, 7.2%-64.0%] White) and 1 531 117 patients in control groups without HIV (pooled proportion [range], 61.7% [59.7%-100%] male; pooled mean [range] age, 67.7 [42.0-69.4] years; pooled proportion [range], 3.3% [95% CI, 2.5%-21.4%] Black, 3.6% [95% CI, 0.7%-36.3%] Hispanic, and 21.1% [95% CI, 14.3%-68.0%] White) who experienced ACS or underwent coronary revascularization were included in the meta-analysis. Summary baseline characteristics of study participants and comparisons of patients living with HIV with patients in control groups are presented in Table 2 and eTable 2 in Supplement 1. The mean age of patients living with HIV was 11.1 years (95% CI, 6.2-16.0 years) less than that of patients in HIV-negative control groups (P < .001). HIV-positive and control populations were similarly male dominant. Patients living with HIV were statistically significantly more likely to be current smokers (pooled proportion [range], 59.1% [24.0%-75.0%] smokers vs 42.8% [26.0%-64.1%] smokers; P < .001) and engage in illicit drug use (pooled proportion [range], 31.2% [2.0%-33.7%] drug use vs 6.8% [0%-11.5%] drug use; P < .001) and had significantly higher pooled mean (range) triglyceride (233 [167-268] vs 171 [148-220] mg/dL; P = .01) and lower pooled mean (range) high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (40 [26-43] vs 46 [29-46] mg/dL; P = .03) levels. (To convert triglycerides and cholesterol to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0113 and 0.0259, respectively.) There were similar proportions of patients with diabetes, hypertension, and a family history of coronary artery disease in the 2 groups (Table 2; eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

Table 2. Patient Demographics With Breakdown of Total Number of Studies and Patients.

| Variable, % | Patients living with HIV | Patients without HIV | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies, No. (N = 15) | Patients, No. (n = 9499) | Pooled mean (range) | Studies, No. (N = 15) | Patients, No. (n = 1 531 117) | Pooled mean (range) | ||

| Follow up, mean, mo | 14 | 9431 | 16.2 (3.0-60.8) | 14 | 1 474 238 | 11.9 (3.0-60.8) | NA |

| Age, mean or median, ya | 14 | 9020 | 56.2 (47.0-63.0) | 14 | 1 529 553 | 67.7 (42.0-69.4) | <.001 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 14 | 9020 | 76.4 (64.3-100) | 14 | 1 529 553 | 61.7 (59.7-100) | .94 |

| Female | 14 | 9020 | 23.6 (0-35.7) | 14 | 1 529 553 | 38.3 (0-40.3) | .94 |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||||

| Black | 5 | 7518 | 10.1 (7.0-62.5) | 5 | 1 262 910 | 3.3 (2.5-21.4) | .60 |

| Hispanic | 3 | 6860 | 8.1 (0.4-54.6) | 3 | 1 205 987 | 3.6 (0.7-36.3) | .73 |

| White | 4 | 7406 | 13.1 (7.2-64.0) | 4 | 1 262 798 | 21.1 (14.3-68.0) | .94 |

| Diabetes | 14 | 9020 | 42.7 (8.7-50.7) | 14 | 1 529 553 | 43.2 (10.7-47.8) | .98 |

| Hypertension | 14 | 9020 | 76.4 (17.4-87.3) | 14 | 1 529 553 | 82.3 (22.1-89.3) | .79 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 10 | 1704 | 55.8 (25.0-84.2) | 10 | 59 915 | 86.7 (29.0-88.6) | .07 |

| Current smoker | 11 | 7903 | 59.1 (24.0-75.0) | 11 | 1 126 946 | 42.8 (26.0-64.1) | <.001 |

| Illicit drug use | 6 | 7472 | 31.2 (2.0-33.7) | 6 | 1 176 953 | 6.8 (0-11.5) | <.001 |

| CKD | 8 | 8480 | 31.1 (2.1-35.6) | 7 | 1 436 380 | 23.1 (1.8-25.6) | .67 |

| Family history of CAD | 8 | 1040 | 21.4 (13.5-56.3) | 8 | 63 746 | 17.9 (15.9-59.4) | .77 |

| BMI, mean | 6 | 948 | 26.5 (22.0-29.7) | 6 | 63 630 | 29.8 (26.0-30.4) | .27 |

| Cholesterol, mean, mg/dL | |||||||

| Total | 7 | 549 | 193 (173-209) | 7 | 5952 | 207 (177-210) | .09 |

| HDL | 7 | 549 | 40 (26-43) | 7 | 5952 | 46 (29-46) | .03 |

| LDL | 6 | 416 | 111 (96- 133) | 6 | 624 | 122 (107-136) | .21 |

| Triglycerides, mean, mg/dL | 6 | 416 | 233 (167-268) | 6 | 624 | 171 (148-220) | .01 |

| Diagnosis | |||||||

| ACS | 13 | 8474 | 99.0 (42.5-100) | 12 | 1 472 694 | 100 (50.0-100) | .58 |

| STEMI | 13 | 8675 | 21.5 (9.2-100) | 12 | 1 270 030 | 14.7 (6.3-100) | .63 |

| NSTEMI | 10 | 7933 | 49.2 (5.0-52.1) | 9 | 1 267 550 | 50.8 (10.0-52.7) | .93 |

| UA | 8 | 7342 | 33.6 (17.4-45.5) | 8 | 1 205 523 | 33.6 (12.5-50) | .99 |

| Underwent PCI | 12 | 8795 | 48.0 (35.3-100) | 11 | 1 179 945 | 40.4 (30.9-100) | .83 |

| Received stent | 7 | 8017 | 32.3 (19.5-100) | 7 | 1 177 361 | 24.4 (16.2-100) | .89 |

| Received CABG | 5 | 1292 | 0.8 (0-12.5) | 4 | 59 363 | 0.1 (0-8.7) | .76 |

| Discharged with medication | |||||||

| Statin | 7 | 7532 | 53.3 (45.8-96.1) | 6 | 1 182 184 | 59.9 (58.4-99.0) | .79 |

| β-blocker | 5 | 7375 | 54.0 (51.3-90.0) | 5 | 1 176 856 | 60.6 (59.6-93.6) | .74 |

| Antiplateletb | 5 | 6962 | 39.1 (36.3-100) | 5 | 1 125 373 | 43.2 (42.9-100) | .84 |

| LVEF after event | 8 | 1028 | 49.4 (44.0-55.4) | 7 | 58 599 | 50.9 (48.0-54.8) | .20 |

| HIV duration, mean, y | 5 | 360 | 11.2 (8.5-12.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Current CD4 count, mean, cells/mm3 | 8 | 1025 | 377 (318-462) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Viral load <200 copies/mL | 5 | 382 | 77.8 (63.3-94.6) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Prescribed ART | 9 | 1246 | 75.2 (50.0-94.1) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Protease inhibitor | |||||||

| Prescribed | 8 | 1095 | 47.6 (25.0-85.6) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Duration, mean, mo | 3 | 268 | 68.7 (36.0-81.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: ACS, acute coronary syndrome; ART, antiretroviral therapy; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NA; not applicable; NSTEMI, non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; UA, unstable angina.

SI conversion factors: To convert cholesterol to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259; triglycerides to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0113.

Some studies provided median, which was taken as approximation of the central tendency, like the mean.

Parks et al33 defined antiplatelets as P2Y2 inhibitors, and the authors acknowledge that the study may have included a significant proportion of patients with type 2 myocardial infarction due to its retrospective, observational nature. When Parks et al33 is excluded for antiplatelet analysis, the aggregated percentage of patients discharged receiving antiplatelets was 92.8% (range, 86.7%-100%) for patients living with HIV and 97.0% (range, 81.5%-100%) for patients in control groups.

Patients with HIV had been diagnosed with HIV for a pooled mean (range) of 11.2 (8.5-12.0) years. From 9 studies11,16,18,26,28,29,31,34,35 that provided these data, a pooled proportion (range) of 75.2% (50.0%-94.1%) of patients living with HIV were receiving ART and 47.6% (25.0%-85.6%) had previously received protease inhibitor therapy. The pooled mean (range) CD4 count was 377 (318-462) cells/mm3 among patients living with HIV, and most of these patients (pooled proportion [range], 77.8% [63.3%-94.6%]) had a viral load less of than 200 copies per mL (Table 2).

Among 13 studies11,15,16,18,25,26,27,28,29,31,32,33,34 that reported data on ACS, patients living with HIV and those in control groups presented similarly with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, and unstable angina. Additionally, the groups received PCIs or coronary artery bypass graft surgery at similar proportions. After revascularization, pooled mean (range) left ventricular ejection fraction values were similar between groups (49.4% [44.0%-55.4%] vs 50.9% [48.0%-54.8%]). On postdischarge follow up, patients living with HIV had a lower proportion (range) of statin (53.3% [45.8%-96.1%] vs 59.9% [58.4%-99.0%]) and β-blocker (54.0% [51.3%-90.0%] vs 60.6% [59.6%-93.6%]) prescription compared with patients in control groups, but these differences were not statistically significant (Table 2; eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

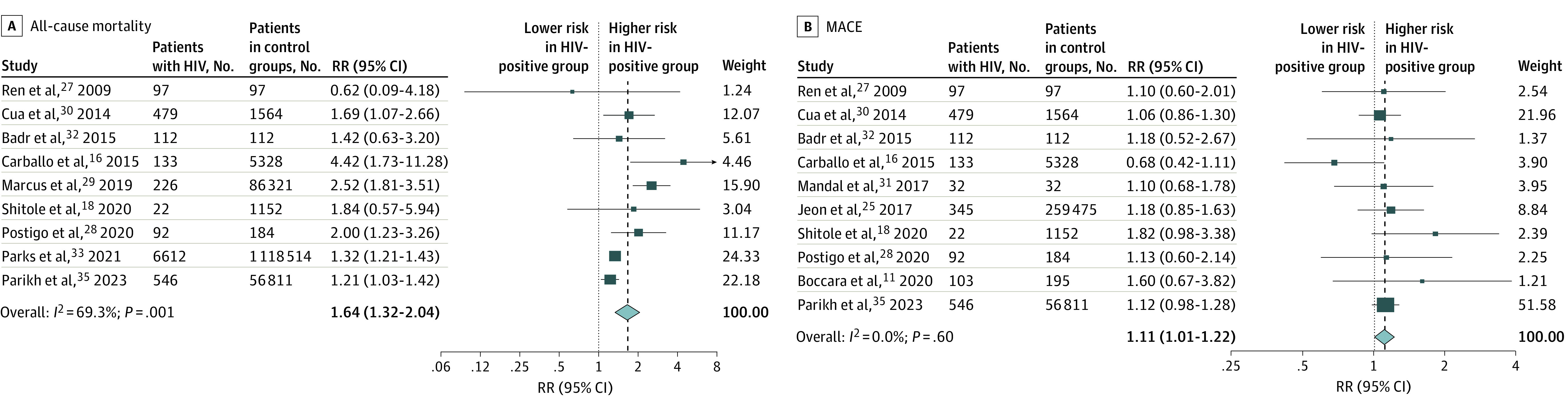

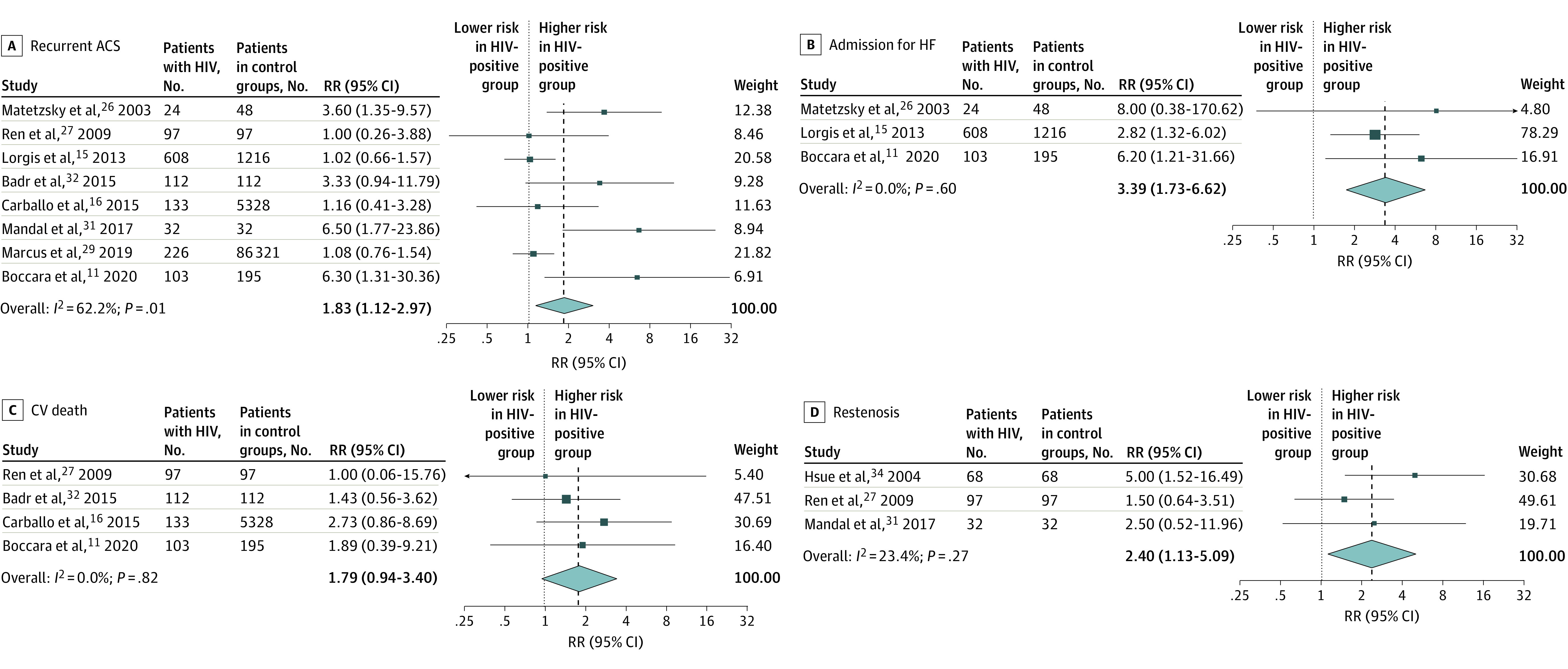

Over a pooled mean (range) follow-up of a mean of 16.2 (3.0-60.8) months after ACS or revascularization, patients living with HIV had a significantly higher adjusted risk of all-cause mortality (pooled adjusted RR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.32-2.04), MACE (RR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.01-1.22), recurrent ACS (RR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.12-2.97), and heart failure readmission (RR, 3.39; 95% CI, 1.73-6.62) (Figure 1), as well as restenosis (RR, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.13-5.09) (Figure 2) compared with patients in HIV-negative control groups (pooled mean [range] follow-up, 11.9 [3.0-60.8] months). For CV death, total vessel revascularization, and total lesion revascularization, pooled HRs showed no significantly higher risk among patients living with HIV compared with patients in control groups (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1). RRs of clinical outcomes and adjustment variables included in multivariate models that were reported by each study are presented in eTable 3 in Supplement 1. Sensitivity analyses specifying an alternative method for the random-effects model yielded comparable results (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). In a separate subsidiary analysis, there was no association between HIV status and risk of post–ACS or PCI mortality, recurrent ACS, or MACE outcomes in the unadjusted (minimally adjusted in some studies) model (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1).

Figure 1. Pooled Relative Risks (RRs) for All-Cause Death and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE).

Dark blue boxes indicate RRs, and horizontal bars indicate 95% CIs. Sizes of dark blue boxes are proportional to the inverse variance. The light blue diamond indicates the pooled RR estimate and 95% CI in the random-effects model meta-analysis. RRs are maximally adjusted estimates as reported by studies (see eTable 1 in Supplement 1 for adjustment variables). Badr et al32 for RR of all-cause death and Postigo et al28 for RR of MACE were crude estimates calculated by this study’s authors based on number of participants and number of events reported for patients living with HIV and control groups. The definition of MACE for Shitole et al18 and Postigo et al28 was death or cardiovascular admissions.

Figure 2. Pooled Relative Risks (RRs) for Other Outcomes.

RRs are shown for recurrent acute coronary syndrome (ACS) (A), heart failure (HF) admission (B), cardiovascular (CV) death (C), and restenosis (D). Dark blue boxes indicate RRs, and horizontal bars indicate 95% CIs. Sizes of dark blue boxes are proportional to the inverse variance. The light blue diamond indicates the pooled RR estimate and 95% CI in the random-effects model meta-analysis.

There was generally low heterogeneity across studies for most outcomes (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Visual inspection of the funnel plot for publication bias assessment and Egger tests did not suggest the presence of significant publication bias (eFigure 4 in Supplement 1). For the all-cause mortality outcome, the Egger test for bias was borderline, and so we performed trim and fill analysis; this yielded similar results (RR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.30-2.00). Included studies were of moderate to high quality based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, indicating a low to moderate risk of bias (eTable 5 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

We performed a literature-based systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 studies of longitudinal clinical outcomes after ACS or revascularization from 2003 to 2023, comprising a total of 9499 patients living with HIV and 1 531 117 patients without HIV in control groups. We found that patients living with HIV were younger and had a higher risk of all-cause mortality, MACE, recurrent ACS, and heart failure after the index event. We also noted lower rates of statin and β-blocker prescription after discharge among patients living with HIV. Overall, these findings highlight the need to develop and implement strategies for secondary prevention of CVD among patients living with HIV.

The increased mortality, recurrence of ACS, and heart failure admissions among patients living with HIV may be attributed to increased traditional CVD risk factors, psychosocial factors, HIV-related chronic inflammation, and long-term effects of ART.11,16 These factors are equally difficult to control after an initial coronary event.19,35,36 The study by Boccara et al11 from 2020 compared its findings with those of their first, 2011 study37 and noted an increased rate of recurrence of ACS in patients living with HIV; the authors also noted persistent smoking and chronic inflammation as factors associated with some of the greatest increases in risk for recurrent disease. This further reinforces the need for a multifaceted approach to secondary prevention.

Of note, our study found suboptimal statin prescription in patients living with HIV after ACS or revascularization, which is consistent with results of other retrospective studies.11,18,19,26,28,38,39,40,41,42 These findings and those of the Evaluating the Use of Pitavastatin to Reduce the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in HIV-Infected Adults (REPRIEVE) trial,14 which demonstrated the benefits of pitavastatin for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease among patients living with HIV, highlight the need for a concerted effort to improve guideline-directed statin prescription and adherence among these patients.43 Additionally, the higher prevalence of smoking and higher triglyceride levels we found among patients living with HIV highlight areas for optimization, with the goal of improving secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Differences in statin and β-blocker prescriptions on follow-up were not statistically significant, although patients living with HIV had numerically lower percentages for both outcomes.

Our pooled estimates for postdischarge antiplatelet therapy are influenced by the study from Parks et al,33 which defined antiplatelet use as a filled prescription for clopidogrel, ticagrelor, prasugrel, or ticlopidine and as a retrospective observational study, could not reliably exclude patients with type 2 myocardial infarctions who would not typically qualify for these therapies. In that study’s sensitivity analyses of patients who received coronary angiography, percentages of patients with postdischarge antiplatelet therapies were significantly higher. We performed an analysis of aggregate postdischarge antiplatelet therapy rates excluding data from Parks et al,33 and aggregate data for postdischarge antiplatelet therapy was much higher.

Few studies reported race or ethnicity of participants, leading to overall low aggregate percentages of White and Black patients living with HIV in our analysis, which is not representative of the global population of these patients. Race and ethnicity in most studies were obtained from review of electronic health records, except in the study by Shitole et al,18 in which race and ethnicity were self-reported. The analysis of race and ethnicity was skewed by 2 studies; in 1 study,44 most of the population’s race and ethnicity was unknown, and in the other study,19 the population was mainly Hispanic. Likewise, the percentage of patients who underwent PCIs was lower than expected for a typical population presenting with ACS. This was also contributed by the Parks et al study,33 which included patients with type 2 myocardial infarctions, who were not candidates for PCIs in their analysis.

Most studies in our analysis included patients receiving ART with low viral loads and CD4 counts greater than 200 cells/mm3, indicating patients with good control of their HIV disease, who are representative of people living with HIV in the current era.1,4,7,45 We found 8 studies11,16,26,27,28,31,34,35 that reported use of protease inhibitors among approximately 50% of patients living with HIV (47.6%). Protease inhibitors are known to have metabolic effects associated with CVD, presenting a plausible explanation for the difference in hypertriglyceridemia between patients living with HIV and patients without HIV in our study.46 Modern ART regimens have transitioned away from the use of protease inhibitors and now include integrase inhibitors.7 Conflicting data have emerged around the possible association of integrase inhibitors with increased incidence of CVD.47,48 Therefore, further research on long-term outcomes associated with ART will be essential to primary and secondary prevention of CVD among patients living with HIV.

The period after ACS or PCI provides additional opportunity to introduce aggressive interventions to improve CVD risk factors in patients living with HIV, and these interventions may involve multidisciplinary teams. Ensuring access to and engagement of cardiologists for patients living with HIV will be important to improve outcomes, especially among underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities.49 Input from pharmacists can also help with optimal selection of statin types, other lipid-lowering agents, and dosages to avoid drug interactions and drug-related adverse effects and maximize adherence to these therapies. Additionally, input from addiction medicine specialists and psychologists can help address underlying mental health disorders (eg, depression and anxiety) and behavioral risk factors (eg, smoking, alcohol use, and cocaine use). In our study, patients living with HIV were more likely to be smokers and engage in illicit drug use, similar to contemporary studies that also show that these behaviors are associated with an overall increased mortality in patients living with HIV despite adequate control of their underlying infection.50 Likewise, assistance from social workers can help to mitigate social determinants associated with diet and the ability to afford crucial medications.36,51,52,53 Addressing this latter aspect is critically important to improve secondary outcomes of CVD in patients living with HIV because despite increased prescription rates for cardioprotective medications, patients living with HIV have been found to be less likely to fill these medications.38,42,52 A multifaceted or multidisciplinary intervention to address psychosocial barriers to cardiovascular care may have the potential to limit mortality and morbidity after ACS or PCI for patients living with HIV.

Limitations

The findings of this meta-analysis should be considered in context of several limitations. First, given that this was a literature based meta-analysis of aggregate published data, we were unable to compare the association between HIV status and CVD outcomes by clinically important subgroup, such as age, race and ethnicity, or sex. Second, the degree of adjustment for confounders in RR estimates is limited to what is reported in individual studies, is not consistent across studies, and may be inadequate overall. For instance, very few studies accounted for HIV-specific characteristics. However, the goal of the meta-analysis was to understand the difference in secondary CVD outcomes stratified by HIV status regardless of factors that may be contributing to them. We also performed a comparison between maximally adjusted and unadjusted or minimally adjusted RRs to provide further insight into the association. Our analysis showed that there was no association between HIV status and post-ACS or -PCI mortality, recurrent ACS, or MACE outcomes in the unadjusted model. This is likely due to the reverse confounding effect of age given that patients living with HIV were significantly younger than patients in control groups, with a difference of 11 years in pooled mean age across studies. Third, most studies included in this review evaluated patients living with HIV who lived in high-income countries, which may limit generalizability to the global population of patients living with HIV. Fourth, we were not able to perform subgroup analyses of patients who had ACS and were treated medically vs PCI, as well as those who received PCI for stable coronary disease, because these data were not reported separately. Future assessment of outcomes within these subgroups would be important for preventative efforts. Fifth, we were unable to identify timelines for prescription of or adherence to ART or cardioprotective medications based on these aggregate data. Understanding these trends will also be an important focus for secondary prevention in future studies.

Conclusions

In this literature based systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies from 2000 to 2023, we found that patients living with HIV were significantly younger than patients in control groups. Patients living with HIV had a significantly higher risk of all-cause mortality, MACE, recurrent ACS, and admission for heart failure after the index event compared with patients in control groups.

Patients living with HIV were also significantly more likely to be current smokers and engage in illicit drug use and had higher triglyceride levels at baseline. As more data emerge for primary prevention, this analysis highlights the need for optimization of secondary prevention strategies to address poor outcomes of CVD among patients living with HIV. Future studies can focus on assessing the role of aggressive interventions, including use of multidisciplinary teams to target important risk factors and improve prescription of and adherence to cardioprotective medications among patients living with HIV after ACS or PCI.

eTable 1. Additional Patient Characteristics by Study for Patients Living With HIV and Patients in Control Groups

eTable 2. Comparison of Patient Characteristics Between Patients Living With HIV and Patients in Control Groups

eTable 3. Clinical Outcomes, Relative Risks, and Adjustment Variables by Study

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analysis of Pooled Relative Risks Calculated Using Knapp-Hartung Method for Random-Effects Model Meta-Analysis

eTable 5. Quality Assessment of Included Studies With Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

eFigure 1. Study Flow Sheet

eFigure 2. Pooled Relative Risks for Patients Living With HIV vs Patients in Control Groups for TLR and TVR

eFigure 3. Pooled Unadjusted Relative Risks for Patients Living With HIV vs Patients in Control Groups for All-Cause Mortality, MACE, and Recurrent ACS

eFigure 4. Funnel Plot of Relative Risks for All-Cause Mortality and MACE

eMethods. Detailed Description of Statistical Analysis

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Feinstein MJ, Hsue PY, Benjamin LA, et al. Characteristics, prevention, and management of cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;140(2):e98-e124. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber R, Ruppik M, Rickenbach M, et al. ; Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS) . Decreasing mortality and changing patterns of causes of death in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. HIV Med. 2013;14(4):195-207. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2012.01051.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freiberg MS, So-Armah K. HIV and cardiovascular disease: we need a mechanism, and we need a plan. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;4(3):e003411. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.So-Armah K, Freiberg MS. HIV and cardiovascular disease: update on clinical events, special populations, and novel biomarkers. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018;15(3):233-244. doi: 10.1007/s11904-018-0400-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, et al. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):614-622. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerrato E, D’Ascenzo F, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. Acute coronary syndrome in HIV patients: from pathophysiology to clinical practice. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2012;2(1):50-55. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2012.02.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friis-Møller N, Thiébaut R, Reiss P, et al. ; DAD study group . Predicting the risk of cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected patients: the data collection on adverse effects of anti-HIV drugs study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17(5):491-501. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328336a150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.So-Armah K, Gupta SK, Kundu S, et al. Depression and all-cause mortality risk in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected US veterans: a cohort study. HIV Med. 2019;20(5):317-329. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erqou S, Jiang L, Choudhary G, et al. Heart failure outcomes and associated factors among veterans with human immunodeficiency virus infection. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(6):501-511. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2019.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haji MS, Ge A, Halladay C, et al. Two decade trends in cardiovascular disease risk factor and outcome burden among veterans with HIV. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(9):1646. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(22)02637-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boccara F, Mary-Krause M, Potard V, et al. ; PACS-HIV (Prognosis of Acute Coronary Syndrome in HIV-Infected Patients) Investigators . HIV infection and long-term residual cardiovascular risk after acute coronary syndrome. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(17):e017578. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.017578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boccara F. Acute coronary syndrome in HIV-infected patients. Does it differ from that in the general population? Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;103(11-12):567-569. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2010.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Douglas PS, Umbleja T, Bloomfield GS, et al. Cardiovascular risk and health among people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) eligible for primary prevention: insights from the REPRIEVE trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(11):2009-2022. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grinspoon SK, Fitch KV, Zanni MV, et al. ; REPRIEVE Investigators . Pitavastatin to prevent cardiovascular disease in HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(8):687-699. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2304146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lorgis L, Cottenet J, Molins G, et al. Outcomes after acute myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients: analysis of data from a French nationwide hospital medical information database. Circulation. 2013;127(17):1767-1774. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carballo D, Delhumeau C, Carballo S, et al. ; Swiss HIV Cohort Study and AMIS registry . Increased mortality after a first myocardial infarction in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients; a nested cohort study. AIDS Res Ther. 2015;12(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s12981-015-0045-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erqou S, Rodriguez-Barradas MC. Secondary prevention of myocardial infarction in people living with HIV infection. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(17):e018140. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.018140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shitole SG, Kuniholm MH, Hanna DB, et al. Association of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus infection with long-term outcomes post-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction in a disadvantaged urban community. Atherosclerosis. 2020;311:60-66. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parks M, Secemsky E, Yeh R, et al. Post-discharge outcomes following acute coronary syndrome in HIV [ disparities for PLWH ]. Abstract presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; March 8-11, 2020; Boston, MA. Accessed April 3, 2024. https://www.natap.org/2020/CROI/croi_220.htm [Google Scholar]

- 20.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45(Pt A):139-145. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Borm GF. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cochran WG. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics. 1954;10(1):101-129. doi: 10.2307/3001666 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539-1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lo CK, Mertz D, Loeb M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeon C, Lau C, Kendall CE, et al. Mortality and health service use following acute myocardial infarction among persons with HIV: a population-based study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2017;33(12):1214-1219. doi: 10.1089/aid.2017.0128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matetzky S, Domingo M, Kar S, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(4):457-460. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.4.457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren X, Trilesskaya M, Kwan DM, Nguyen K, Shaw RE, Hui PY. Comparison of outcomes using bare metal versus drug-eluting stents in coronary artery disease patients with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(2):216-222. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.03.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Postigo A, Díez-Delhoyo F, Devesa C, et al. Clinical profile, anatomical features and long-term outcome of acute coronary syndromes in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Intern Med J. 2020;50(12):1518-1523. doi: 10.1111/imj.14744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marcus JL, Hurley LB, Prasad A, et al. Recurrence after hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals. HIV Med. 2019;20(1):19-26. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cua B, Justice A, McGinnis K, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention outcomes in HIV+ and HIV-patients. Conference Abstract. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7(suppl_1):A308. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandal PC. TCTAP A-081 Comparative Observational Study of Procedural Outcomes and Long Term Prognosis of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in ’HIV' Infected Patients of Rural West Bengal, India. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(16):S45. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Badr S, Minha S, Kitabata H, et al. Safety and long-term outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with human immunodeficiency virus. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;85(2):192-198. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parks MM, Secemsky EA, Yeh RW, et al. Longitudinal management and outcomes of acute coronary syndrome in persons living with HIV infection. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2021;7(3):273-279. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsue PY, Giri K, Erickson S, et al. Clinical features of acute coronary syndromes in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Circulation. 2004;109(3):316-319. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000114520.38748.AA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parikh RV, Hebbe A, Barón AE, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes among people living with HIV undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the Veterans Affairs Clinical Assessment, Reporting, and Tracking Program. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12(4):e028082. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.028082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freiberg MS. HIV and cardiovascular disease—an ounce of prevention. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(8):760-761. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2306782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boccara F, Mary-Krause M, Teiger E, et al. ; Prognosis of Acute Coronary Syndrome in HIV-infected patients (PACS) Investigators . Acute coronary syndrome in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: characteristics and 1 year prognosis. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(1):41-50. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erqou S, Papaila A, Halladay C, et al. Variation in statin prescription among veterans with HIV and known atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2022;249:12-22. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2022.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenson RS, Colantonio LD, Burkholder G, Chen L, Muntner P. Abstract 18543: trends in statin use among adults with and without HIV. Circulation. 2017;136:A18543. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larson D, Won SH, Ganesan A, et al. Statin usage and cardiovascular risk among people living with HIV in the U.S. Military HIV Natural History Study. HIV Med. 2022;23(3):249-258. doi: 10.1111/hiv.13195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelly SG, Krueger KM, Grant JL, et al. Statin prescribing practices in the comprehensive care for HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;76(1):e26-e29. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Todd JV, Cole SR, Wohl DA, et al. Underutilization of statins when indicated in HIV-seropositive and seronegative women. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2017;31(11):447-454. doi: 10.1089/apc.2017.0145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boccara F, Miantezila Basilua J, Mary-Krause M, et al. ; on behalf the PACS-HIV investigators (Prognosis of Acute Coronary Syndrome in HIV-infected patients) . Statin therapy and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol reduction in HIV-infected individuals after acute coronary syndrome: results from the PACS-HIV lipids substudy. Am Heart J. 2017;183:91-101. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shitole SG, Kuniholm MH, Peng AY, et al. Abstract 20323: human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C Virus (HCV) infection and risk of adverse outcomes after ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in a low-income urban population. Circulation. 2017;136(suppl_1). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shah ASV, Stelzle D, Lee KK, et al. Global burden of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV: systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2018;138(11):1100-1112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.033369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Penzak SR, Chuck SK. Management of protease inhibitor-associated hyperlipidemia. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2002;2(2):91-106. doi: 10.2165/00129784-200202020-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neesgaard B, Greenberg L, Miró JM, et al. Associations between integrase strand-transfer inhibitors and cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV: a multicentre prospective study from the RESPOND cohort consortium. Lancet HIV. 2022;9(7):e474-e485. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(22)00094-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Surial B, Chammartin F, Damas J, et al. ; Swiss HIV Cohort Study . Impact of integrase inhibitors on cardiovascular disease events in people with human immunodeficiency virus starting antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;77(5):729-737. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciad286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bloomfield GS, Hill CL, Chiswell K, et al. Cardiology encounters for underrepresented racial and ethnic groups with human immunodeficiency virus and borderline cardiovascular disease risk. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023. doi: 10.1007/s40615-023-01627-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petoumenos K, Law MG. Smoking, alcohol and illicit drug use effects on survival in HIV-positive persons. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11(5):514-520. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown JL, Diclemente RJ. Secondary HIV prevention: novel intervention approaches to impact populations most at risk. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8(4):269-276. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0092-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ladapo JA, Richards AK, DeWitt CM, et al. Disparities in the quality of cardiovascular care between HIV-infected versus HIV-uninfected adults in the United States: a cross-sectional study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(11):e007107. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lesko CR, Todd JV, Cole SR, et al. ; WIHS Investigators . Mortality under plausible interventions on antiretroviral treatment and depression in HIV-infected women: an application of the parametric g-formula. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(12):783-789.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Additional Patient Characteristics by Study for Patients Living With HIV and Patients in Control Groups

eTable 2. Comparison of Patient Characteristics Between Patients Living With HIV and Patients in Control Groups

eTable 3. Clinical Outcomes, Relative Risks, and Adjustment Variables by Study

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analysis of Pooled Relative Risks Calculated Using Knapp-Hartung Method for Random-Effects Model Meta-Analysis

eTable 5. Quality Assessment of Included Studies With Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

eFigure 1. Study Flow Sheet

eFigure 2. Pooled Relative Risks for Patients Living With HIV vs Patients in Control Groups for TLR and TVR

eFigure 3. Pooled Unadjusted Relative Risks for Patients Living With HIV vs Patients in Control Groups for All-Cause Mortality, MACE, and Recurrent ACS

eFigure 4. Funnel Plot of Relative Risks for All-Cause Mortality and MACE

eMethods. Detailed Description of Statistical Analysis

Data Sharing Statement