Abstract

Photoluminescent coordination complexes of Cr(III) are of interest as near-infrared spin-flip emitters. Here, we explore the preparation, electrochemistry, and photophysical properties of the first two examples of homoleptic N-heterocyclic carbene complexes of Cr(III), featuring 2,6-bis(imidazolyl)pyridine (ImPyIm) and 2-imidazolylpyridine (ImPy) ligands. The complex [Cr(ImPy)3]3+ displays luminescence at 803 nm on the microsecond time scale (13.7 μs) from a spin-flip doublet excited state, which transient absorption spectroscopy reveals to be populated within several picoseconds following photoexcitation. Conversely, [Cr(ImPyIm)2]3+ is nonemissive and has a ca. 500 ps excited-state lifetime.

Short abstract

The synthesis, characterization, and photophysical study of homoleptic N-heterocyclic carbene complexes of Cr(III) are provided, and near-infrared (NIR) spin-flip luminescence in fluid solution with microsecond lifetime is observed.

Photoactive complexes of Cr(III) have long been of interest due to long-lived luminescence in the deep-red and near-infrared (NIR) spectral regions, which originates from spin-flip metal-centered (2MC) excited states of doublet multiplicity (e.g., 2E and 2T1).1−4 While classical Cr(III)-centered luminophores have typically been plagued by low quantum yields (Φem < 0.1%),5,6 pioneering developments made in molecular design over the past decade, in particular the reporting of the efficient NIR emitter [Cr(ddpd)2]3+ (ddpd = N,N′-dimethyl-N,N′-dipyridine-2-ylpyridine-2,6-diamine),7 has allowed Cr(III)-based emitters to reach quantum yields of up to 30%8 with luminescence lifetimes on the millisecond time scale.9,10 Key to this success is the use of strong-field donors in conjunction with a close-to-ideal octahedral coordination geometry in achieving large ligand-field splitting. This enhanced splitting shifts strongly distorted 4T2 states to higher energy, preventing their population through back-intersystem crossing (bISC) and therefore minimizing nonradiative deactivation of the desirable and luminescent 2T1/2E states.

With the continued development of Cr(III)-based emitters comes the need to control the energy, and hence the color, of luminescence. To date, the vast majority of Cr(III) luminophores feature polypyridyl-based ligand architectures and typically emit within the narrow range of ca.720–780 nm.4 The energy of the phosphorescent 2MC excited states is strongly dependent upon the degree of interelectronic repulsion at the metal center and is hence governed by the nephelauxetic effect of the ligand set.11 Consequently, diversification of ligand design and the introduction of new, ideally strong-field, donor moieties to Cr(III) coordination chemistry is an essential tool in achieving control over the energy of luminescence. We have recently reported the luminescent chromium(III) triazolyl complex [Cr(btmp)2]3+ [btmp = 2,6-bis(4-phenyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-ylmethyl)pyridine], although phosphorescence falls within the more typical spectral region at λem = 760 nm.12 A series of complexes featuring 1,8-(bis-oxazolyl)carbazolide ligands were reported to emit over the range 813–845 nm in fluid solution,13 whereas the complex [Cr(bpi)2]3+ [bpi = 1,3-bis(2′-pyridylimino)isoindoline] displays weak room temperature (r.t.) luminescence centered at 950 nm.14 The homoleptic neutral cyclometalate [Cr(ppy)3] is also reported to be luminescent at 910 nm.15 Emission is successfully shifted into the NIR-II range through the use of a π-donating carbazolato fragment in [Cr(dpc)2]+ [dpc = 3,6-di-tert-butyl-1,8-di(pyridine-2-yl)carbazolato] (λem = 1067 nm), albeit only observable at cryogenic temperature.16

In an effort to not only optimize ligand-field strength but also continue to diversify the range of donors utilized within photoactive Cr(III) coordination complexes, N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) are a new avenue to explore. As strong σ donors, NHCs are anticipated to cause particularly large ligand-field splitting and consequent destabilization of deleterious 4T2 excited states, thus promoting long-lived luminescence from the interconfigurational doublet states. Indeed, NHCs are now ubiquitous throughout transition-metal coordination chemistry and have been used to achieve favorable photophysical properties for complexes of Fe(II),17 Fe(III),18 Co(III),19 and Mn(IV).20 Surprisingly, NHCs have seldom been combined with Cr(III) centers,21 featuring only within heteroleptic complexes which catalyze the oligomerization of ethylene but for which no photophysical properties are reported.22−25

The imidazolium salts ImPyIm-H2 and PyIm-H (Scheme 1) were deprotonated with lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide (LiHMDS) at −40 °C in anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF) before the addition of a suspension of CrIICl2 in THF. Subsequent aerial oxidation in the presence of NH4PF6 afforded 1 and 2 as air- and moisture-stable yellow solids in yields of 23% and 56%, respectively. The magnetic susceptibilities of 1 and 2 were 3.82 and 3.90 μB, respectively, consistent with that expected for d3 coordination complexes with a quartet ground-state electronic configuration (3.87 μB).

Scheme 1. Synthetic Route to Cr(III) NHC Complexes 1 and 2.

X-ray diffraction studies reveal 1 to crystallize in space group P21/c (Figure 1a), with C2–Cr1–C12 and C2–Cr1–N3 bond angles of 153.7(1)° and 76.7(1)°, respectively, revealing significant distortion of the coordination environment away from an ideal octahedral geometry due to the tris-chelating nature of the ligand. The torsion angle between the central pyridyl and flanking imidazolylidene moieties is 2.8°, revealing the essentially planar nature of the ligand, with the lack of conformational flexibility preventing helical wrapping around the Cr(III) center, as observed for [Cr(ddpd)2]3+ 7 and [Cr(btmp)2]3+ 12 for example. The Cr–N(pyridyl) bond length of 2.020(4) Å is typical for Cr(III) complexes,7,10,12 with the Cr–C(carbene) lengths being only slightly longer at ca. 2.1 Å. Complex 2 crystallizes in the Pbcm space group, with the molecular structure (Figure 1b) revealing that the asymmetric ligand adopts a meridional arrangement around the Cr(III) center. The use of bis-chelating ligands provides a pseudooctahedral coordination environment that is less distorted than that observed for 1, with C9–Cr1–C9′ and C9–Cr1–N1 bond angles of 174.2(4)° and 77.9(2)°, respectively.

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of 1 (a) and 2 (b). Thermal ellipsoids are shown at 50% probability, with H atoms, counterions, and cocrystallized solvent molecules removed for clarity.

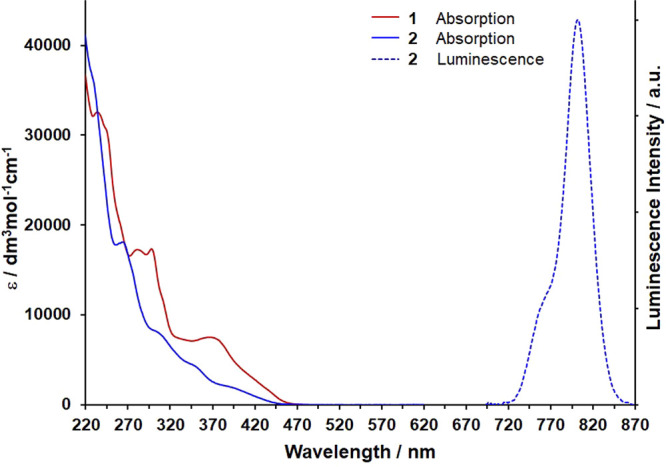

Electronic absorption spectra recorded for MeCN solutions of 1 and 2 are shown in Figure 2. Both complexes exhibit intense absorbance features in the region of 240 nm, attributed to ligand-localized π–π* excitations, with further transitions between 275 and 325 nm likely having largely ligand-based charge-transfer and π–π* character. With the aid of quantum-chemical calculations (Figures S11 and S12 and Tables S3 and S4), we assign the broad, moderately intense absorption envelope between 325 and 450 nm to transitions of predominantly ligand-to-metal charge-transfer (LMCT) character. These charge-transfer absorbances obscure very weak ligand-field absorptions, the lowest in energy of which are calculated to arise at approximately 25000 cm–1 for both 1 and 2.

Figure 2.

Electronic absorption and luminescence spectra (λex = 350 nm) recorded for aerated r.t. MeCN solutions of 1 and 2.

Cyclic voltammograms (Figure 3) show that both 1 and 2 display three fully electrochemically reversible reduction waves between −0.9 and −2.4 V versus ferrocenium/ferrocene (vs Fc+/Fc; Table 1). Because electrochemical reduction in complexes of Cr(III) may be metal-based7 or ligand-based,26−28 we carried out spectroelectrochemical monitoring to aid our assignment of each reduction process (Figures S2 and S3). Changes in the absorption spectra accompanying the first reduction process at ca. −0.9 V reveal the growth of new absorbances across the visible region, in particular the appearance of a broad, featureless band centered at 700 nm for 1 and two bands at 630 and 790 nm for 2. The position and intensity of these bands (ε ≈ 8000 M–1 cm–1) are not compatible with those expected for a metal-localized reduction process10,27 but rather are more consistent with π–π* or charge-transfer transitions associated with coordinated ImPyIm•– and ImPy•– radical fragments. Further electrochemical reduction of 1 and 2 results in the appearance of additional significant features across the visible region (Figures S2 and S3), which are again consistent with ligand-localized transitions.

Figure 3.

Cyclic voltammograms (vs Fc+/Fc) recorded at 100 mV s–1 for 1.5 × 10–3 mol dm–3 MeCN solutions of 1 and 2 containing nBu4NPF6.

Table 1. Summarized Photophysical and Electrochemical Data Recorded for MeCN Solutions of 1 and 2.

|

E1/2/V vs Fc+/Fc (ΔEa,c/mV)d |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λabs/nm (ε/mol–1 dm3 cm–1)a | λem/nma,c | τem/μs | Ered(1) | Ered(2) | Ered(3) | |

| 1 | 233 (32740), 245 (30555), 284 (17220), 300 (17300), 370 (7475), 422 (2580) | –0.91 (72) | –1.39 (66) | –1.92 (70) | ||

| 2 | 230 (35775), 237 (17720), 308 (7850), 351 (4300), 398 (1760) | 803 | 13.7a (18.8b) | –0.92 (81) | –1.58 (85) | –2.43 (94) |

Aerated MeCN.

Deaerated MeCN.

λex = 350 nm.

Recorded at 100 mV s–1. ΔEa,c for Fc+/Fc = 70 mV.

Excitation of an aerated acetonitrile (MeCN) solution of 2 at 350 nm results in the observation of a sharp luminescence band centered at 803 nm accompanied by a less intense shoulder at 765 nm, which is absent from the spectrum recorded at 77 K (Figures 2 and S6). These spectral features are assigned to phosphorescence from the closely spaced and thermally equilibrated 2E and 2T1 excited states, respectively. Consistent with this assignment, a luminescence lifetime of 13.7 μs at r.t. was determined by time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC), which increases to 18.8 μs upon exclusion of molecular oxygen. Likewise, the quantum yield of luminescence increases marginally for deoxygenated fluid solutions from 0.014 to 0.016%, which, although low, is respectable for complexes that emit beyond 800 nm under ambient conditions. This low luminescence efficiency may, in part, be due to a decrease in energy of the emissive states and consequent energy-gap law effects,13,29,30 while torsional degrees of freedom available within the bidentate ligands may result in a more flexible structure and consequent enhancement of nonradiative deactivation channels. The position of the observed luminescence maximum is noteworthy because it is shifted outside of the rather narrow range typically observed for the more extensively studied polypyridyl-based Cr(III)-centered spin-flip emitters, likely due to a subtly increased nephelauxetic effect imparted by the NHC donors. In stark contrast to 2, complex 1 is nonemissive in both fluid solution and in a frozen solvent glass at 77 K. This is attributed to the significant deviation of the coordination sphere away from an ideal octahedral geometry upon coordination of the conformationally rigid ImPyIm ligand and the consequent reduction in the ligand-field strength despite the presence of four NHC donors.

Following excitation of an MeCN solution of 2 with a 400 nm, 40 fs laser pulse, a very broad transient signal appears across the spectral window (350–700 nm; Figure 4b), which undergoes complex evolution within the first 10 ps. Global analysis reveals several decay components (Figure S10), sub-100 fs, 0.38 ps, 2.3 ps, and a constant. The fastest, sub-100 fs process is too close to the instrument response to be resolved and likely corresponds to internal conversion within a hot manifold of quartet states, convolved with intersystem crossing (ISC) to the doublet manifold; surprisingly, ISC in 2 occurs much faster than the ∼800 fs that we recently determined for a luminescent Cr(III) complex.12 The spectrum of the next kinetic component, 0.38 ps, shows a bleaching of the ground-state absorbencies below 370 nm and, superimposed on a broad positive background, spectral features at 430, 550, and 630 nm, which somewhat resemble those of two-electron-reduced 2 (Figure S3b). With a lifetime of ca. 0.38 ps, this species evolves into the next excited state, lacking the 430 nm feature but retaining rather indistinct 550 and 665 nm bands, in addition to a band at ca. 368 nm. With ca. 2 ps lifetime, this state evolves into the final excited state, whose spectrum is dominated by a broad, somewhat structured absorption band centered at 430 nm (473 nm shoulder), with a weaker band at 615 nm and a small feature at 385 nm. This spectral shape persists beyond the time scale of the experiment (7 ns). The difference between the spectra associated with the 0.38 and 2.32 ps components (Figure S10d) implies population of states of different electronic origin within the doublet manifold. The final component represents population of the close-lying and thermally equilibrated phosphorescent 2T1 and 2E states. The lifetime of this final excited state determined by independent laser flash photolysis experiments (Figure S8) is 13.4 μs, being in good agreement with the emission lifetime determined by TCSPC measurements.

Figure 4.

Transient absorption spectra recorded for aerated MeCN solutions of (a) 1 and (b) 2 (λex = 400 nm).

Mirroring the stark differences in the photoluminescence characteristics of 1 and 2, transient absorption spectra recorded for 1 (Figure 4a) reveal rapid excited-state decay, with all excited-state absorption features decaying within 1.5 ns. Interestingly, the best fit of the ultrafast data was achieved with a branched kinetic model, where the state initially populated upon photoexcitation rapidly (<100 fs) evolves to populate two independent excited states (Figure S9). A short-lived state (τ = 3.9 ps) is characterized by a slightly structured broad absorption band centered around 500 nm (similar to doubly reduced 1; Figure S2b). The second excited state has absorbances at approximately 400, 470, and 670 nm (similar to the absorption spectrum of the anion of 1; Figure S2a) and a lifetime of 476 ps. These features are possibly representative of 4LMCT and/or strongly Jahn–Teller distorted 4T2 levels, populated via 2MC-deactivating bISC (τ < 100 fs) as a result of the distorted geometry and weakened ligand field, the strength of which may also depend upon the relative arrangement of pyridyl and NHC fragments. Alongside the possible operation of additional nonradiative deactivation pathways, this rapid deactivation of the excited state accounts for the lack of spin-flip luminescence in 1.

In summary, the first two examples of homoleptic Cr(III) complexes featuring NHC donors are presented. [Cr(ImPy)3]3+ displays spin-flip luminescence at 803 nm on the microsecond time scale, with the luminescent excited states populated within several picoseconds following photoexcitation. The employment of NHC donors provides sufficient ligand-field strength to promote population of the desirable doublet excited states, with minimal bISC to the deactivating quartet manifold. Continuing to widen the scope of donors employed within photoactive Cr(III) complexes will enable a significant expansion of chemical space for future exploration and the further development of new NIR-emissive materials.

Acknowledgments

P.A.S. acknowledges financial support from the Royal Society (RGS\R2\192292) and the Royal Society of Chemistry (RF19-2770) in addition to the Leverhulme Trust (RPG-2022-128). R.W.J. thanks the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) for a doctoral studentship (EP/R513234/1). J.A.W., R.C., I.I.I., D.C., and T.M.R. thank the University of Sheffield for support and the EPSRC for a Capital Award to the Lord Porter Laser Laboratory. J.A.W and I.I.I. also acknowledge support from the EPSRC (EP/T012455/1).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.4c01270.

Experimental methods and instrumentation, synthetic procedures, crystallographic data, steady-state and time-resolved photophysical data, and computational details and data (PDF)

Author Contributions

† R.W.J. and R.A.C. contributed equally to this work. This manuscript was written with contributions from all authors.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kane-Maguire N. A. P.Photochemistry and Photophysics of Coordination Compounds: Chromium. In Photochemistry and Photophysics of Coordination Compounds I; Balzani V., Campagna S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, 2007; pp 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk A. D. Photochemistry and Photophysics of Chromium(III) Complexes. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99 (6), 1607–1640. 10.1021/cr960111+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenknecht P. S.; Ford P. C. Metal centered ligand field excited states: Their roles in the design and performance of transition metal based photochemical molecular devices. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255 (5), 591–616. 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scattergood P. A.Recent advances in chromium coordination chemistry: luminescent materials and photocatalysis. Organometallic Chemistry; The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2021; Vol. 43, pp 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk A. D.; Porter G. B. Luminescence of chromium(III) complexes. J. Phys. Chem. 1980, 84 (8), 887–891. 10.1021/j100445a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serpone N.; Jamieson M. A.; Henry M. S.; Hoffman M. Z.; Bolletta F.; Maestri M. Excited-state behavior of polypyridyl complexes of chromium(III). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101 (11), 2907–2916. 10.1021/ja00505a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otto S.; Grabolle M.; Förster C.; Kreitner C.; Resch-Genger U.; Heinze K. [Cr(ddpd)2]3+: A Molecular, Water-Soluble, Highly NIR-Emissive Ruby Analogue. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54 (39), 11572–11576. 10.1002/anie.201504894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Otto S.; Dorn M.; Kreidt E.; Lebon J.; Sršan L.; Di Martino-Fumo P.; Gerhards M.; Resch-Genger U.; Seitz M.; et al. Deuterated Molecular Ruby with Record Luminescence Quantum Yield. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (4), 1112–1116. 10.1002/anie.201711350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Kitzmann W. R.; Weigert F.; Förster C.; Wang X.; Heinze K.; Resch-Genger U. Matrix Effects on Photoluminescence and Oxygen Sensitivity of a Molecular Ruby. ChemPhotoChem. 2022, 6 (6), e202100296 10.1002/cptc.202100296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Treiling S.; Wang C.; Förster C.; Reichenauer F.; Kalmbach J.; Boden P.; Harris J. P.; Carrella L. M.; Rentschler E.; Resch-Genger U.; et al. Luminescence and Light-Driven Energy and Electron Transfer from an Exceptionally Long-Lived Excited State of a Non-Innocent Chromium(III) Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58 (50), 18075–18085. 10.1002/anie.201909325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha N.; Yaltseva P.; Wenger O. S. The Nephelauxetic Effect Becomes an Important Design Factor for Photoactive First-Row Transition Metal Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62 (30), e202303864 10.1002/anie.202303864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. W.; Auty A. J.; Wu G.; Persson P.; Appleby M. V.; Chekulaev D.; Rice C. R.; Weinstein J. A.; Elliott P. I. P.; Scattergood P. A. Direct Determination of the Rate of Intersystem Crossing in a Near-IR Luminescent Cr(III) Triazolyl Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145 (22), 12081–12092. 10.1021/jacs.3c01543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.; Yang Q.; He J.; Zou W.; Liao K.; Chang X.; Zou C.; Lu W. The energy gap law for NIR-phosphorescent Cr(III) complexes. Dalton Transactions 2023, 52 (9), 2561–2565. 10.1039/D2DT02872G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawicka N.; Craze C. J.; Horton P. N.; Coles S. J.; Richards E.; Pope S. J. A. Long-lived, near-IR emission from Cr(III) under ambient conditions. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58 (38), 5733–5736. 10.1039/D2CC01434C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein L.; Boden P.; Naumann R.; Förster C.; Niedner-Schatteburg G.; Heinze K. The overlooked NIR luminescence of Cr(ppy)3. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58 (22), 3701–3704. 10.1039/D2CC00680D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha N.; Jiménez J.-R.; Pfund B.; Prescimone A.; Piguet C.; Wenger O. S. A Near-Infrared-II Emissive Chromium(III) Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (44), 23722–23728. 10.1002/anie.202106398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chábera P.; Kjaer K. S.; Prakash O.; Honarfar A.; Liu Y.; Fredin L. A.; Harlang T. C. B.; Lidin S.; Uhlig J.; Sundström V.; et al. Fe(II) Hexa N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complex with a 528 ps Metal-to-Ligand Charge-Transfer Excited-State Lifetime. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9 (3), 459–463. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b02962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjær K. S.; Kaul N.; Prakash O.; Chábera P.; Rosemann N. W.; Honarfar A.; Gordivska O.; Fredin L. A.; Bergquist K.-E.; Häggström L.; et al. Luminescence and reactivity of a charge-transfer excited iron complex with nanosecond lifetime. Science 2019, 363 (6424), 249–253. 10.1126/science.aau7160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufhold S.; Rosemann N. W.; Chábera P.; Lindh L.; Bolaño Losada I.; Uhlig J.; Pascher T.; Strand D.; Wärnmark K.; Yartsev A.; et al. Microsecond Photoluminescence and Photoreactivity of a Metal-Centered Excited State in a Hexacarbene–Co(III) Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (3), 1307–1312. 10.1021/jacs.0c12151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J. P.; Reber C.; Colmer H. E.; Jackson T. A.; Forshaw A. P.; Smith J. M.; Kinney R. A.; Telser J. Near-infrared 2Eg → 4A2g and visible LMCT luminescence from a molecular bis-(tris(carbene)borate) manganese(IV) complex. Can. J. Chem. 2017, 95 (5), 547–552. 10.1139/cjc-2016-0607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uetake Y.; Niwa T.; Nakada M. Synthesis and characterization of a new C2-symmetrical chiral tridentate N-heterocyclic carbene ligand coordinated Cr(III) complex. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2015, 26 (2), 158–162. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2015.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness D. S.; Gibson V. C.; Wass D. F.; Steed J. W. Bis(carbene)pyridine Complexes of Cr(III): Exceptionally Active Catalysts for the Oligomerization of Ethylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125 (42), 12716–12717. 10.1021/ja037217o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness D. S.; Suttil J. A.; Gardiner M. G.; Davies N. W. Ethylene Oligomerization with Cr–NHC Catalysts: Further Insights into the Extended Metallacycle Mechanism of Chain Growth. Organometallics 2008, 27 (16), 4238–4247. 10.1021/om800398e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness D. S.; Gibson V. C.; Steed J. W. Bis(carbene)pyridine Complexes of the Early to Middle Transition Metals: Survey of Ethylene Oligomerization and Polymerization Capability. Organometallics 2004, 23 (26), 6288–6292. 10.1021/om049246t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thagfi J. A.; Lavoie G. G. Preparation and Reactivity Study of Chromium(III), Iron(II), and Cobalt(II) Complexes of 1,3-Bis(imino)benzimidazol-2-ylidene and 1,3-Bis(imino)pyrimidin-2-ylidene. Organometallics 2012, 31 (21), 7351–7358. 10.1021/om300873k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough C. C.; Sproules S.; Weyhermüller T.; DeBeer S.; Wieghardt K. Electronic and Molecular Structures of the Members of the Electron Transfer Series [Cr(tbpy)3]n (n = 3+, 2+, 1+, 0): An X-ray Absorption Spectroscopic and Density Functional Theoretical Study. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50 (24), 12446–12462. 10.1021/ic201123x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough C. C.; Lancaster K. M.; DeBeer S.; Weyhermüller T.; Sproules S.; Wieghardt K. Experimental Fingerprints for Redox-Active Terpyridine in [Cr(tpy)2](PF6)n (n = 3–0), and the Remarkable Electronic Structure of [Cr(tpy)2]1-. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51 (6), 3718–3732. 10.1021/ic2027219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowda A. S.; Petersen J. L.; Milsmann C. Redox Chemistry of Bis(pyrrolyl)pyridine Chromium and Molybdenum Complexes: An Experimental and Density Functional Theoretical Study. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57 (4), 1919–1934. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b02809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspar J. V.; Kober E. M.; Sullivan B. P.; Meyer T. J. Application of the energy gap law to the decay of charge-transfer excited states. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104 (2), 630–632. 10.1021/ja00366a051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caspar J. V.; Meyer T. J. Application of the energy gap law to nonradiative, excited-state decay. J. Phys. Chem. 1983, 87 (6), 952–957. 10.1021/j100229a010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.