Abstract

Tobacco use is associated with morbidity and mortality. Many individuals who present to treatment facilities with substance use disorders (SUDs) other than tobacco use disorder also smoke cigarettes or have a concomitant tobacco use disorder. Despite high rates of smoking among those with an SUD, and numerous demonstrated benefits of comprehensive SUD treatment for tobacco use in addition to co-occurring SUDs, not all facilities address the treatment of comorbid tobacco use disorder. In addition, facilities vary widely in terms of tobacco use policies on campus. This study examined SUD facility smoking policies in a national sample of N = 16,623 SUD treatment providers in the United States in 2021. Most facilities with outpatient treatment (52.1%) and facilities with residential treatment (67.8%) had a smoking policy that permitted smoking in designated outdoor area(s). A multinomial logistic regression model found that among facilities with outpatient treatment (n = 13,778), those located in a state with laws requiring tobacco free grounds at SUD facilities, those with tobacco screening/education/counseling services, and those with nicotine pharmacotherapy were less likely to have an unrestrictive tobacco smoking policy. Among facilities with residential treatment (n = 3449), those with tobacco screening/education/counseling services were less likely to have an unrestrictive tobacco smoking policy. There is variability in smoking policies and tobacco use treatment options in SUD treatment facilities across the United States. Since tobacco use is associated with negative biomedical outcomes, more should be done to ensure that SUD treatment also focuses on reducing the harms of tobacco use.

Keywords: Nicotine, pharmacotherapy, policy, substance use disorder, treatment

Introduction

In 2021, more than 1 out of 10 Americans smoked cigarettes – an estimated 28 million people. 1 While the prevalence of tobacco use both globally and in the United States has decreased since the beginning of the 21st century, cigarette smoking remains a pressing public health concern. 2 As has been widely acknowledged for decades, cigarette use is inextricably linked to numerous negative health consequences, including cardiovascular disease, lung disease, gastric and duodenal ulcers, osteoporosis, reproductive disorders, adverse postoperative events, and delayed wound healing.3-5 Not only is cigarette use associated with significant morbidity, it is also a leading cause of preventable mortality in the United States. 5 Each year, cigarette smoking causes 8 million premature deaths globally and nearly half a million deaths across the country, including those from secondhand smoke. 2 The life expectancy of a person who smokes tobacco is at least 10 years shorter than persons who do not smoke tobacco.5,6 Additionally, the economic burden of smoking-related costs in the United States is large. Estimates from the CDC approximate that cigarette smoking cost the U.S. more than $600 billion in 2018, including healthcare costs and lost productivity from smoking-related morbidity and mortality. 7 Although nicotine is highly addictive and smoking cessation has proven challenging for many, reduction in tobacco use has clear short-term and long-lasting economic and health benefits.4,8,9

Despite promising trends in smoking cessation across the general population, data suggest that the prevalence of tobacco use among individuals with a substance use disorder (SUD) remains elevated compared to those without.10-12 Many individuals who present to treatment facilities with substance use disorders (SUDs) other than tobacco use disorder also smoke cigarettes or have a concomitant tobacco use disorder. 13 For example, a review article on the smoking prevalence in SUD treatment found that across included studies, the lowest prevalence in a single year was 65%. 11 Although some persons may experience barriers to accessing and entering SUD treatment (eg, financial access, lack of insurance coverage, stigma),14-18 studies examining outcomes of treatment have found that SUD treatment is linked to reduced substance use, decreased criminal justice involvement, and improved quality of life.19-24 Further, SUD treatment varies across different levels of care (eg, outpatient and residential programs), which are often associated with different severities of SUD-related factors and treatment needs. 25 Despite high rates of smoking among those with an SUD and numerous demonstrated benefits of comprehensive addiction treatment, which includes treatment for tobacco use in addition to co-occurring SUDs, not all facilities address the treatment of comorbid tobacco use disorder. In addition, facilities vary widely in terms of tobacco use policies on campus. 26 A previous study using a national sample of SUD treatment facilities in 2016 found that 64% screened persons for tobacco use, 47% provided smoking cessation counseling, and 35% had smoke free campus policies. 26

The distribution of various smoking policies in SUD treatment may vary by the laws of the state in which a treatment facility is housed. 27 Further, the proportion of adults who smoke cigarettes also varies between different states. However, not much is known about the relative influence of state-level and organization-level factors on SUD treatment facility smoking policies. Specifically, in this study we examine, at the state level, the proportion of adults who smoke in a state and differences in state laws requiring tobacco-free grounds, and at the organization level, whether a facility conducts tobacco use screening and whether SUD treatment facilities offer nicotine pharmacotherapy treatment as factors related to SUD treatment facility smoking policies.

The aims of this research were to:

Aim 1: Describe SUD treatment facility tobacco-related treatment options and smoking policies.

Aim 2: Examine how state-level and organizational-level factors are related to SUD facility smoking policies.

This current study examined SUD facility smoking policies in a national sample of treatment providers during the year 2021. Findings from this exploratory study are needed to examine the current range of smoking policies in SUD treatment facilities and potential state and organizational level factors associated with these policies.

Methods

Datasets

Three data sources were used to examine state-level data associated with SUD facility smoking policies. These data are (1) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Prevalence & Trends Data: 2020, 28 (2) National Substance Use and Mental Health Services Survey (N-SUMHSS), 2021, 29 and (3) U.S. State Laws Requiring Tobacco-Free Grounds for Mental Health and Substance Use Facilities. 30 As all the data used in this study are de-identified (treatment facilities) and publicly available, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board considered this study to be Not Human Subjects Research.

Behavioral risk factor surveillance system (BRFSS) prevalence & trends data: 2020

The BRFSS Prevalence & Trends Data is provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and contains national and state-level data about health topics, such as alcohol consumption and tobacco use. 28 The BRFSS is a cross-sectional study that is used to collect prevalence data on behaviors of adults in the U.S. regarding health-related behavior. 28 For this study, the BRFSS Prevalence & Trends Data were provided the proportion of adults who used tobacco in each state for the year 2020. 28

National substance use and mental health services survey (N-SUMHSS), 2021

The N-SUMHSS, 2021, is provided by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and contains facility characteristics about SUD and mental health facilities at all treatment facilities known to SAMHSA in a given year using survey data from facility representatives collected by mail, phone, or online. 29 For this study, data from the N-SUMHSS, 2021 survey were used to examine SUD treatment facility characteristics that included whether or not each facility offered tobacco assessment screening, provided tobacco education/counseling, offered nicotine replacement pharmacotherapy, offered non-nicotine cessation pharmacotherapy, and had smoking policies for the year 2021. 29 SUD treatment facilities in this dataset served as the unit of analysis for this study.

U.S. State laws requiring tobacco-free grounds for mental health and substance use facilities

Data regarding U.S. State Laws Requiring Tobacco-Free Grounds for Mental Health and Substance Use Facilities were obtained from the Public Health Law Center at Mitchell Hamline Law School. 30 These data are publicly available and were captured by scanning state laws and regulations about smoking on the premises of substance use treatment facilities as of January 1, 2022. 30 For this study, these data were used to describe the percentages of SUD treatment facilities in a state based on the state laws requiring tobacco-free grounds for SUD treatment facilities. 30 Details about the specific laws for each state may be found elsewhere (See Reference number 30). 30

Sample selection

The N-SUMHSS, 2021 contains data on 32,371 SUD and mental health disorder treatment facilities in the U.S. 29 The following sample selection criteria were applied to identify the study sample: (1) provided SUD treatment, (2) non-missing data for the outcome, the facility’s smoking policy, and (3) based in the U.S. (excluded U.S. territories), which provided a sample of 16,623 SUD treatment facilities. Data for the following study variables were missing: residential treatment (n = 5 missing), assessment screening for tobacco use (n = 131 missing), education and counseling smoking/tobacco cessation (n = 153 missing), pharmacotherapy: nicotine replacement (n = 204 missing), and pharmacotherapy: non-nicotine cessation (n = 210 missing). Using Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test, the data were examined and determined to be MCAR (P = .591), indicating no bias from listwise deletion. After removing facilities that were missing data for study variables, a final analytic sample of 16,042 was included in the study. This analytic sample was bifurcated to conduct the analyses within two subsamples, (1) N = 13,778 SUD facilities with outpatient treatment and (2) N = 3449 SUD facilities with non-hospital residential (residential) treatment.

Measures

Binary state proportion of adults who use tobacco

The BRFSS Prevalence & Trends Data were used to create this variable which identifies the 2020 state proportion of adults who use tobacco. 28 This numerical variable was used to create a binary variable that included two values (1) SUD treatment facilities located in the 25 states (and DC) with the lowest proportion of adults who use tobacco and (2) SUD treatment facilities located in the 25 states with the highest proportion of adults who use tobacco. The states were dichotomized to conduct an exploratory examination comparing states with the highest prevalence of adults who smoke to states with the lowest prevalence of adults who smoke.

State laws requiring tobacco-free grounds

The U.S. State Laws Requiring Tobacco-Free Grounds for Mental Health and Substance Use Facilities was used to create this variable which identifies whether a state has a law or regulation requiring SUD treatment facilities to have tobacco-free premises. 30 This categorical variable included Yes, Partial, and No as response options. For the purpose of these analyses, a two-level variable was created with the following values (1) Yes or Partial and (2) No to describe whether a facility was located in a state with laws requiring tobacco-free grounds.

Assessment screening or education/counseling for tobacco

The N-SUMHSS, 2021 was used to create this variable, which identifies whether the SUD treatment facilities had assessment screening and/or education/counseling for tobacco. 29 Two binary (Yes/No) variables in the dataset were merged to create this variable. One of the merged variables describes whether a facility conducts assessment screening for tobacco use, while the other variable describes whether a facility provides education/counseling for tobacco. 29 A facility that selected yes to one or both of these services was identified as having assessment screening or education/counseling for tobacco. The final variable was re-coded to (1) Yes and (2) No.

Pharmacotherapy: nicotine replacement or non-nicotine cessation

The N-SUMHSS, 2021 was used to create this variable which identifies whether the SUD treatment facilities in this sample had pharmacotherapies for nicotine. 29 Two binary (Yes/No) variables in the dataset were merged to create this variable. One of the merged variables described whether a facility provides nicotine replacement pharmacotherapy, while the other variable describes whether a facility provides non-nicotine cessation pharmacotherapy. 29 A facility that selected yes to one or either of these services was identified as having pharmacotherapy: nicotine replacement or non-nicotine cessation. The final variable was recoded to (1) Yes and (2) No.

Facility smoking policy

The N-SUMHSS, 2021 was used to create this variable which identifies an SUD treatment facility’s smoking policy. 29 The dataset contains six different values for this variable that includes (1) not permitted to smoke anywhere outside or within any building, (2) permitted in designated outdoor area(s), (3) permitted anywhere outside, (4) permitted designated indoor area(s), (5) permitted anywhere inside, and (6) permitted anywhere without restriction. Because of small cell sizes, the last three values were merged to examine different levels of smoking policies in SUD treatment facilities. Therefore, for the purpose of this study, this variable included three values: (1) not permitted to smoke anywhere outside or within any building, (2) permitted in designated outdoor area(s), and (3) permitted anywhere outside, designated indoor area(s), anywhere inside, or anywhere. This three-level variable served as the dependent variable for this study.

Data analysis

IBM SPSS Version 28.0 31 was used to complete the statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics were used to separately examine the (1) N = 13,778 SUD facilities with outpatient treatment and (2) N = 3449 SUD facilities with non-hospital residential treatment. Multinomial logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine facility smoking policies as the dependent variable. The reference value for smoking policies is “not permitted to smoke anywhere outside or within any building”. Independent variables included (1) Binary State Proportion of Adults who use Tobacco (Reference: lowest 25 states and DC), (2) State Laws Requiring Tobacco-Free Grounds (Reference: No), (3) Assessment Screening or Education/Counseling for Tobacco (Reference: No), and (4) Pharmacotherapy: Nicotine Replacement or Non-Nicotine Cessation (Reference: No). All four independent variables were analyzed separately to examine the unadjusted odds ratios. The four independent variables were also added to the model simultaneously to examine the adjusted odds ratios (AORs). The analyses were conducted within two groups, facilities with outpatient treatment and facilities with non-hospital residential treatment. This paper will focus on the results of the simultaneous models. However, the unadjusted models are presented in table format to show the independent variable changes from the individual to simultaneous models. The simultaneous multinomial logistic regression model in facilities with non-hospital residential treatment excluded the pharmacotherapy variable. This methodological adjustment was made due to five cells (10.4%) having zero frequencies. State level data were plotted using the R 32 packages “ggplot2” 33 and “usmap”. 34

Results

Facility characteristics

Characteristics of outpatient substance use disorder treatment facilities

Characteristics of the N = 13,778 facilities with outpatient treatment may be found in the second column of Table 1. Most outpatient facilities (n = 8,053, 58.4%) were in the 25 states (and DC) with the lowest proportion of adults who use tobacco. Further, most outpatient facilities (n = 10,428, 75.7%) were in states that did not have laws requiring tobacco-free grounds for SUD facilities. Smoking policies in outpatient facilities included 40.6% (n = 5600) of facilities not permitting smoking anywhere outside or within any building, 52.1% (n = 7172) of facilities permitting smoking in designated outdoor area(s), and 7.3% (n = 1006) permitting smoking anywhere outside, designated indoor area(s), anywhere inside, or anywhere.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Outpatient and Residential Substance Use Disorder Treatment Facilities.

| Characteristics | N = 13,778 | N = 3449 |

|---|---|---|

| Facilities with Outpatient Treatment | Facilities with Residential Treatment | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| State proportion of adults who use tobacco | ||

| 8.2 to 12.7 Percent | 4933 (35.8%) | 1484 (43.0%) |

| 12.8 to 15.1 Percent | 2833 (20.6%) | 724 (21.0%) |

| 15.2 to 18.1 Percent | 2834 (20.6%) | 581 (16.8%) |

| 18.2 to 22.6 Percent | 3178 (23.1%) | 660 (19.1%) |

| Binary state proportion of adults who use tobacco | ||

| In the 25 states (and DC) with the lowest proportion of adults who use tobacco | 8053 (58.4%) | 2250 (65.2%) |

| In the 25 states with the highest proportion of adults who use tobacco | 5725 (41.6%) | 1199 (34.8%) |

| State laws requiring tobacco-free grounds for SUD facilities | ||

| Yes | 2523 (18.3%) | 510 (14.8%) |

| Partial | 827 (6.0%) | 139 (4.0%) |

| No | 10,428 (75.7%) | 2800 (81.2%) |

| Outpatient treatment | 13,778 (100.0%) | 1185 (34.4%) |

| Residential treatment | 1185 (8.6%) | 3449 (100.0%) |

| Assessment screening for tobacco use | 11,090 (80.5%) | 2739 (79.4%) |

| Education and Counseling smoking/Tobacco Cessation | 8828 (64.1%) | 2520 (73.1%) |

| Assessment screening or education/Counseling for tobacco a | 11,624 (84.4%) | 2964 (85.9%) |

| Pharmacotherapy: Nicotine replacement | 4618 (33.5%) | 1955 (56.7%) |

| Pharmacotherapy: Non-Nicotine Cessation | 4397 (31.9%) | 1418 (41.1%) |

| Pharmacotherapy: Nicotine replacement or Non-Nicotine cessation b | 5307 (38.5%) | 2036 (59.0%) |

| Facility smoking policy | ||

| Not permitted to smoke anywhere outside or within any building | 5600 (40.6%) | 1062 (30.8%) |

| Permitted in designated outdoor Area(s) | 7172 (52.1%) | 2338 (67.8%) |

| Permitted anywhere outside, designated indoor Area(s), anywhere inside, or anywhere | 1006 (7.3%) | 49 (1.4%) |

aThis variable is a combination of (1) Assessment Screening for Tobacco Use and (2) Education and Counseling Smoking/Tobacco Cessation.

bThis variable is a combination of (1) Pharmacotherapy: Nicotine Replacement and (2) Pharmacotherapy: Non-Nicotine Cessation.

Characteristics of residential substance use disorder treatment facilities

Characteristics of the N = 3449 facilities with residential treatment may be found in the third column of Table 1. Most residential facilities (n = 2,250, 65.2%) were in the 25 states (and DC) with the lowest proportion of adults who use tobacco. Further, most residential facilities (n = 2,800, 81.2%) were in states that did not have laws requiring tobacco-free grounds for SUD facilities. Smoking policies in residential facilities included 30.8% (n = 1062 of facilities not permitting smoking anywhere outside or within any building, 67.8% (n = 2338) of facilities permitting smoking in designated outdoor area(s), and 1.4% (n = 49) permitting smoking anywhere outside, designated indoor area(s), anywhere inside, or anywhere.

State level data

State level data may be found in Supplemental Table 1. States with the lowest and highest proportions of adults who use tobacco in 2020 were Utah (8.2%) and West Virginia (22.6%). Nine states had a state law requiring tobacco-free grounds for SUD treatment facilities. These nine states are: Alaska, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, and Oregon. Four states were identified as having laws that partially require tobacco-free grounds for SUD treatment facilities. Figure 1 geographically plots these state-level laws.

Figure 1.

State laws and regulations requiring tobacco-free grounds.

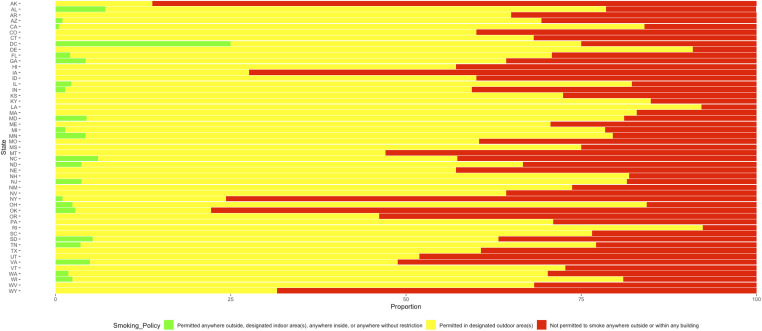

State-level proportions of outpatient SUD facility smoking policies may be found in Figure 2, and the state-level proportions of residential SUD facility smoking policies may be found in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

State level proportions of outpatient facility smoking policies.

Figure 3.

State level proportions of non-hospital residential facility smoking policies.

Outpatient substance use disorder facility smoking policies

Table 2 shows results from the multinomial logistic regression models examining outpatient SUD facility smoking policies. Facilities in the top 25 states of adults who use tobacco had higher odds of having a smoking policy of permitted in designated outdoor area(s) than a policy of not permitted to smoke anywhere outside or within any building (AOR = 1.167, 95% CI = 1.085, 1.256, P < .001). Facilities in states with laws requiring tobacco-free grounds for SUD facilities (AOR = .475, 95% CI = .437, .516, P < .001), facilities with assessment screening or education/counseling for tobacco (AOR = .584, 95% CI = .522, .654, P < .001), and with pharmacotherapy: nicotine replacement or non-nicotine cessation (AOR = .591, 95% CI = .548, .637, P < .001), had lower odds of having a smoking policy of permitted in designated outdoor area(s) than a policy of not permitted to smoke anywhere outside or within any building.

Table 2.

Outpatient Substance Use Disorder Facility Smoking Policies: Multinomial Logistic Regression Model.

| Permitted in Designated Outdoor Area(s) vs Not Permitted to Smoke Anywhere Outside or Within Any Building | Permitted in Designated Outdoor Area(s) vs Not Permitted to Smoke Anywhere Outside or Within Any Building | Permitted Anywhere Outside, Designated Indoor Area(s), Anywhere Inside, or Anywhere vs Not Permitted to Smoke Anywhere Outside or Within Any Building | Permitted Anywhere Outside, Designated Indoor Area(s), Anywhere Inside, or Anywhere vs Not Permitted to Smoke Anywhere Outside or Within Any Building | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Unadjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Unadjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

| State proportion of adults who use tobacco | ||||||||

| Highest 25 states vs Lowest 25 states and DC | 1.143*** | 1.065, 1.227 | 1.167*** | 1.085, 1.256 | 1.045 | .912, 1.198 | 1.055 | .918, 1.213 |

| State laws requiring tobacco-free grounds a | ||||||||

| Yes or partial vs No | .451*** | .416, .490 | .475*** | .437, .516 | .644*** | .551, .752 | .725*** | .619, .850 |

| Assessment screening or education/Counseling b | ||||||||

| Yes vs No | .457*** | .410, .509 | .584*** | .522, .654 | .238*** | .202, .279 | .348*** | .294, .412 |

| Pharmacotherapy c | ||||||||

| Yes vs No | .516*** | .480, .554 | .591*** | .548, .637 | .259*** | .220, .305 | .333*** | .281, .395 |

N = 13,778

afor SUD Facilities.

bfor Tobacco.

cNicotine Replacement or Non-Nicotine Cessation.

*P < .05.

**P < .01.

***P < .001.

Facilities in states with laws requiring tobacco-free grounds for SUD facilities (AOR = .725, 95% CI = .619, .850, P < .001), facilities with assessment screening or education/counseling for tobacco (AOR = .348, 95% CI = .294, .412, P < .001), and with pharmacotherapy: nicotine replacement or non-nicotine cessation (AOR = .333, 95% CI = .281, .395, P < .001), had lower odds of having a smoking policy of permitted anywhere outside, designated indoor area(s), anywhere inside, or anywhere than a policy of not permitted to smoke anywhere outside or within any building.

Non-hospital residential substance use disorder facility smoking policies

Table 3 shows results from the multinomial logistic regression models examining outpatient SUD facility smoking policies. Facilities in states with laws requiring tobacco-free grounds for SUD facilities (AOR = .310, 95% CI = .259, .370, P < .001) had lower odds of having a smoking policy of permitted in designated outdoor area(s) than a policy of not permitted to smoke anywhere outside or within any building.

Table 3.

Residential Substance Use Disorder Facility Smoking Policies: Multinomial Logistic Regression Model.

| Permitted in Designated Outdoor Area(s) vs. Not Permitted to Smoke Anywhere Outside or Within Any Building | Permitted in Designated Outdoor Area(s) vs. Not Permitted to Smoke Anywhere Outside or Within Any Building | Permitted Anywhere Outside, Designated Indoor Area(s), Anywhere Inside, or Anywhere vs. Not Permitted to Smoke Anywhere Outside or Within Any Building | Permitted Anywhere Outside, Designated Indoor Area(s), Anywhere Inside, or Anywhere vs. Not Permitted to Smoke Anywhere Outside or Within Any Building | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Unadjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Unadjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

| State proportion of adults who use tobacco | ||||||||

| Highest 25 states vs Lowest 25 states and DC | .892 | .766, 1.038 | .968 | .827, 1.131 | 1.308 | .733, 2.335 | 1.303 | .726, 2.340 |

| State laws requiring tobacco-free grounds a | ||||||||

| Yes or partial vs No | .306*** | .257, .366 | .310*** | .259, .370 | .686 | .353, 1.332 | .747 | .381, 1.465 |

| Assessment screening or education/Counseling b | ||||||||

| Yes vs No | .788* | .634, .981 | .861 | .689, 1.077 | .232*** | .126, .427 | .240*** | .130, .444 |

| Pharmacotherapy c | ||||||||

| Yes vs No | .902 | .778, 1.046 | .309*** | .168, .568 | ||||

N = 3449.

Note: The Pharmacotherapy: Nicotine Replacement or Non-Nicotine Cessation Variable was not added to the adjusted models due to small cell sizes.

afor SUD Facilities.

bfor Tobacco.

cNicotine Replacement or Non-Nicotine Cessation.

*P < .05.

**P < .01.

***P < .001.

Facilities with assessment screening or education/counseling for tobacco (AOR = .240, 95% CI = .130, .444, P < .001), had lower odds of having a smoking policy of permitted anywhere outside, designated indoor area(s), anywhere inside, or anywhere than a policy of not permitted to smoke anywhere outside or within any building.

Discussion

This study was an examination of smoking policies in outpatient and residential SUD treatment facilities and their relationship with state level (eg, proportion of adults who smoke and state laws) and treatment facility level characteristics (eg, tobacco use screening and pharmacotherapy).

Facilities with outpatient treatment had more restrictive smoking policies if they were in a state with laws that placed restrictions on smoking in SUD treatment facilities, conducted assessment, screening, or education/counseling for tobacco use, or provided tobacco-related pharmacotherapy. In outpatient treatment, persons typically leave the facility after receiving treatment. Therefore, while they are able to smoke after departing from the facility, providing tobacco-related treatment services such as pharmacotherapy or counseling may reduce the potential harms of at-risk tobacco use or a tobacco use disorder. 35 This study found facilities with residential treatment as having more restrictive smoking policies if they conducted assessment, screening, or education/counseling for tobacco use. Like facilities with outpatient treatment, tobacco treatment services are similarly needed in facilities with residential treatment as these persons may experience the effects of nicotine withdrawal.35-37 This is especially true since residential treatment implies more limited access to leaving the treatment facility than outpatient treatment.

Considering that smoking is associated with returning to previous patterns of substance use,38,39 support and treatment are needed for persons who smoke and receive SUD treatment. In addition to screening, comprehensive treatment for tobacco use disorder must include tobacco education, counseling, and nicotine replacement therapy. Nicotine replacement therapy such as transdermal patches, gum, nasal spray, and lozenges, has been shown to aid in quitting and reduce the rates of smoking by 50 to 70%. 37 Additionally, staff education and training can help abate biases around tobacco use and reduce barriers to integrating comprehensive tobacco cessation programs in SUD treatment settings.40,41 These training programs are important as barriers to the integration of more comprehensive tobacco cessation programs in SUD facilities have historically included staff attitudes, lack of staff training, clinical lore (including misconceptions such as “tobacco is not a real drug”), smoking culture, staff smoking, resource limitations, and resistance to smoke free grounds.42,43 For facilities that offer tobacco related treatment, especially, having smoke-free campus policies for everyone including patients, staff, and others, will best support the health and success of their patients. Some perceptions exist that emphasizing smoking cessation during addiction treatment jeopardizes treatment retention and success. However, data suggests that smoking cessation does not have a negative effect on the treatment of concomitant substance use disorders and has been shown to aid substance use disorder treatment outcomes in some studies (with other studies finding no differences in outcomes such as abstinence from alcohol and other drugs, highlighting the need for future research).44-48

Findings from this study identified the variability of smoking policies among facilities in each state. There are identifiable differences in the proportion of facility smoking policies between facilities in the same state and between the states themselves (see Figures 1–3). Several states have mandated smoking bans in either specific areas of SUD treatment facilities or throughout the entire campus. There is a historical context to these policies, as New Jersey became the first state to implement tobacco-free ground requirements in residential treatment facilities in 2001.49,50 Fears emerged that these bans would discourage individuals with a tobacco use disorder from entering treatment programs or lead to premature departure from treatment. However, in a follow up evaluation, survey results indicated that 41% of individuals who smoke did not use any tobacco during their treatment stay, and there was no increase in irregular discharges or reduction in proportion of individuals who smoke among those entering residential treatment. 50

In 2008, New York required all state-certified addiction treatment programs to require smoke-free grounds, to implement smoke-free policies for treatment center staff, and to provide tobacco dependence interventions for all persons receiving treatment.51,52 A one-year follow-up indicated that smoking among individuals that received treatment decreased from 69.4% to 62.8% and those who received residential treatment were more likely to report having quit smoking after policy implementation. 51 Although a five-year follow-up (from 2008 to 2013) did not find a significant decrease in smoking prevalence among persons who received treatment, a decrease in the average number of cigarettes smoked per day (13.7 to 10.2) was identified among individuals who received treatment and the prevalence of smoking among staff decreased (35.2% to 21.8%). 52 In 2013, the Center for Dependency, Addiction, and Rehabilitation, part of the University of Colorado Hospital system, implemented a tobacco-free policy, including nicotine replacement therapy, individual smoking cessation education, and group tobacco cessation counseling to support persons who received treatment. 53 The policy led to abstinence among individuals who smoke entering treatment and also prevented the initiation of tobacco use among persons who did not smoke tobacco. In addition, individuals receiving treatment who had used tobacco at admission were 9 times more likely to report an intention to remain tobacco-free at the time of discharge compared to those who attended the program prior to policy implementation. 53 Overall, the geopolitical context of each state and SUD smoking policies is varied and includes different histories. Given that targeted interventions for smoking cessation, including smoking bans, have demonstrated promise for reducing tobacco-related disparities among individuals with a substance use disorder, states and treatment facilities must act to reduce the harms related to tobacco use by effectively supporting and treating persons with an SUD who also smoke. Further, tobacco prevention and education efforts in these facilities nationwide may reduce the harmful impacts of tobacco use.

This study expands the literature by providing state and facility level factors associated with different smoking policies in SUD treatment and reflects an innovative use of publicly available data sources. However, study findings should be considered alongside limitations. While the N-SUMHSS 2021 facility smoking policy variable has six possible values, we reduced this to a three-level dependent variable due to small cell sizes. As described in the measures section of this paper, many independent variables and their values were also combined to account for small cell sizes. Further, small cell sizes did not allow for the opportunity to examine an adjusted model using all the independent variables among the residential SUD treatment facilities in our sample. Other unexamined, latent factors may also be associated with different facility smoking policies that were not addressed in the current study. Lastly, the current study did not examine vaping policies in these facilities. Considering the prominence of vaping, future studies should examine vaping policies in a national sample of SUD treatment facilities. Despite these limitations, this study provides pertinent data regarding the describing variability of smoking policies in SUD treatment facilities and some of the factors that may shape these policies.

Conclusion

There is variability in smoking policies and tobacco use treatment options in SUD treatment facilities within and across states in the U.S. Since tobacco use is associated with negative biomedical outcomes, more should be done to ensure that SUD treatment also focuses on reducing the harms of tobacco use.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Smoking Policies of Outpatient and Residential Substance Use Disorder Treatment Facilities in the United States by Alison G. Holt, Andrea Hussong, M. Gabriela Castro, Kelly Bossenbroek Fedoriw, Allison M. Schmidt, Amy Prentice, and Orrin D. Ware in Group & Organization Management.

Ethical Statement

Ethical Approval

As all the data used in this study are publicly available, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board considered this study to be Not Human Subjects Research.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: : Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Fast facts and fact sheets: smoking and cigarettes. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fast_facts/index.htm

- 2.GBD 2019 Tobacco Collaborators . Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021;397(10292):2337-2360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01169-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartecchi CE, MacKenzie TD, Schrier RW. The human costs of tobacco use. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(13):907-912. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403313301307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallucci G, Tartarone A, Lerose R, Lalinga AV, Capobianco AM. Cardiovascular risk of smoking and benefits of smoking cessation. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12(7):3866-3876. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2020.02.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health . The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):341-350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Economic trends in tobacco. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/economics/econ_facts/index.htm#economic-costs

- 8.Lightwood JM, Glantz SA. Short-term economic and health benefits of smoking cessation: myocardial infarction and stroke. Circulation. 1997;96(4):1089-1096. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.4.1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor DH, Hasselblad V, Henley SJ, Thun MJ, Sloan FA. Benefits of smoking cessation for longevity. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(6):990-996. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalman D, Morissette SB, George TP. Co-morbidity of smoking in patients with psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am J Addict. 2005;14(2):106-123. doi: 10.1080/10550490590924728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guydish J, Passalacqua E, Tajima B, Chan M, Chun J, Bostrom A. Smoking prevalence in addiction treatment: a review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(6):401-411. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han B, Einstein EB, Compton WM. Patterns and characteristics of nicotine dependence among adults with cigarette use in the US, 2006-2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(6):e2319602. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.19602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McClure EA, Campbell AN, Pavlicova M, et al. Cigarette smoking during substance use disorder treatment: secondary outcomes from a national drug abuse treatment clinical trials network study. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;53:39-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farhoudian A, Razaghi E, Hooshyari Z, et al. Barriers and facilitators to substance use disorder treatment: an overview of systematic reviews. Subst Abuse. 2022;16:11782218221118462. doi: 10.1177/11782218221118462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomko C, Olfson M, Mojtabai R. Gaps and barriers in drug and alcohol treatment following implementation of the affordable care act. Drug Alcohol Depend Rep. 2022;5:100115. doi: 10.1016/j.dadr.2022.100115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Priester MA, Browne T, Iachini A, Clone S, DeHart D, Seay KD. Treatment access barriers and disparities among individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: an integrative literature review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;61:47-59. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Y, Perkins DR, Stearns AE. Barriers and facilitators to treatment engagement among clients in inpatient substance abuse treatment. Qual Health Res. 2018;28(9):1474-1485. doi: 10.1177/1049732318771005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dickson-Gomez J, Weeks M, Green D, Boutouis S, Galletly C, Christenson E. Insurance barriers to substance use disorder treatment after passage of mental health and addiction parity laws and the affordable care act: a qualitative analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend Rep. 2022;3:100051. doi: 10.1016/j.dadr.2022.100051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daigre C, Rodríguez L, Roncero C, et al. Treatment retention and abstinence of patients with substance use disorders according to addiction severity and psychiatry comorbidity: a six-month follow-up study in an outpatient unit. Addict Behav. 2021;117:106832. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hser YI, Evans E, Huang D, Anglin DM. Relationship between drug treatment services, retention, and outcomes. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(7):767-774. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.7.767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Facing addiction in America: the Surgeon General’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health. Chapter 4, Early intervention, treatment, and management of substance use disorders. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424859/.[Not Available in CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gossop M, Marsden J, Stewart D, Rolfe A. Reductions in acquisitive crime and drug use after treatment of addiction problems: 1-year follow-up outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;58(1-2):165-172. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00077-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hubbard RL, Craddock SG, Anderson J. Overview of 5-year followup outcomes in the drug abuse treatment outcome studies (DATOS). J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;25(3):125-134. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00130-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ettner SL, Huang D, Evans E, et al. Benefit-cost in the California treatment outcome project: does substance abuse treatment “pay for itself”. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(1):192-213. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00466.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mee-Lee D, Shulman GD, Fishman MJ, Gastfriend DR, Miller SM. The ASAM Criteria: Treatment Criteria for Addictive, Substance-Related, and Co-occurring Conditions. 3rd ed. The Change Companies; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marynak K, VanFrank B, Tetlow S, et al. Tobacco cessation interventions and smoke-free policies in mental health and substance abuse treatment facilities - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(18):519-523. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6718a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krauth D, Apollonio DE. Overview of state policies requiring smoking cessation therapy in psychiatric hospitals and drug abuse treatment centers. Tob Induc Dis. 2015;13:33. doi: 10.1186/s12971-015-0059-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Behavioral risk factor surveillance system: prevalence & trends data. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/index.html

- 29.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . National Substance Use and Mental Health Services Survey (N-SUMHSS): 2021. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Public Health Law Center at Mitchell Hamline School of Law . U.S. State laws requiring tobacco-free grounds for mental health and substance use facilities. https://www.publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/resources/Tobacco-Free-State-Policies-Mental-Health-Substance-Use-Facilities.pdf.[Not Available in CrossRef]

- 31.IBM Corp. IBM . SPSS Statistics: Version 28.0. Armonk, NY 2021. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- 32.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.R-project.org/

- 33.Wickham H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34.CRAN . Package usmap. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/usmap/index.html

- 35.Siu AL, US Preventive Services Task Force . Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: U.S. Preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(8):622-634. doi: 10.7326/M15-2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLaughlin I, Dani JA, De Biasi M. Nicotine withdrawal. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2015;24:99-123. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-13482-6_4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hartmann‐Boyce J, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Bullen C, Lancaster T. Nicotine replacement therapy versus control for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5:CD000146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinberger AH, Platt J, Copeland J, Goodwin RD. Is cannabis use associated with increased risk of cigarette smoking initiation, persistence, and relapse? longitudinal data from a representative sample of US adults. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(2):2254. doi: 10.4088/JCP.17m11522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weinberger AH, Platt J, Zhu J, Levin J, Ganz O, Goodwin RD. Cigarette use and cannabis use disorder onset, persistence, and relapse: longitudinal data from a representative sample of US adults. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82(4):20m13713. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20m13713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guydish J, Le T, Hosakote S, et al. Tobacco use among substance use disorder (SUD) treatment staff is associated with tobacco-related services received by clients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2022;132:108496. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martínez C, Lisha N, McCuistian C, Strauss E, Deluchi K, Guydish J. Comparing client and staff reports on tobacco-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and services provided in substance use treatment. Tob Induc Dis. 2023;21:45. doi: 10.18332/tid/160974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ziedonis DM, Guydish J, Williams J, Steinberg M, Foulds J. Barriers and solutions to addressing tobacco dependence in addiction treatment programs. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29(3):228-235 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pagano A, Tajima B, Guydish J. Barriers and facilitators to tobacco cessation in a nationwide sample of addiction treatment programs. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;67:22-29. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baca CT, Yahne CE. Smoking cessation during substance abuse treatment: what you need to know. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36(2):205-219. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsoh JY, Chi FW, Mertens JR, Weisner CM. Stopping smoking during first year of substance use treatment predicted 9-year alcohol and drug treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;114(2-3):110-118. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McKelvey K, Thrul J, Ramo D. Impact of quitting smoking and smoking cessation treatment on substance use outcomes: an updated and narrative review. Addict Behav. 2017;65:161-170. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Appollonio D, Philipps R, Bero L. Interventions for tobacco use cessation in people in treatment for or recovery from substance use disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11(11):CD010274. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010274.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thurgood SL, McNeill A, Clark-Carter D, Brose LS. A systematic review of smoking cessation interventions for adults in substance abuse treatment or recovery. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):993-1001. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams J, Order-Connors B, Edwards N. Integrating tobacco dependence treatment and tobacco-free standards into addiction treatment: New Jersey’ experience. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29(3):236-240 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams JM, Foulds J, Dwyer M, et al. The integration of tobacco dependence treatment and tobacco-free standards into residential addictions treatment in New Jersey. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28(4):331-340. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guydish J, Tajima B, Kulaga A, et al. The New York policy on smoking in addiction treatment: findings after 1 year. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):e17-e25. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pagano A, Guydish J, Le T, et al. Smoking behaviors and attitudes among clients and staff at new york addiction treatment programs following a smoking ban: findings after 5 years. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):1274-1281. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Richey R, Garver-Apgar C, Martin L, Morris C. Tobacco-free policy outcomes for an inpatient substance abuse treatment center. Health Promot Pract. 2017;18(4):554-560. doi: 10.1177/1524839916687542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Smoking Policies of Outpatient and Residential Substance Use Disorder Treatment Facilities in the United States by Alison G. Holt, Andrea Hussong, M. Gabriela Castro, Kelly Bossenbroek Fedoriw, Allison M. Schmidt, Amy Prentice, and Orrin D. Ware in Group & Organization Management.