Abstract

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTLP), a unique variant of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, clinically mimics subcutaneous panniculitis. It is typified by the development of multiple plaques or subcutaneous erythematous nodules, predominantly on the extremities and trunk. Epidemiological findings reveal a greater incidence in females than males, affecting a wide demographic, including pediatric and adult cohorts, with a median onset age of around 30 years. Diagnosis of SPTLP is complex, hinging on skin biopsy analyses and the identification of T-cell lineage-specific immunohistochemical markers. Treatment modalities for SPTLP are varied; while corticosteroids may be beneficial initially for many patients, a substantial number require chemotherapy, especially in cases of poor response or relapse. Generally, SPTLP progresses slowly, yet approximately 20% of cases advance to hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), often correlating with a negative prognosis. We report a case of a young male patient presenting with prolonged fever, multiple skin lesions accompanied by HLH, a poor clinical course, and eventual death, diagnosed postmortem with SPTLP. In addition, we also present a literature review of the current evidence of some updates related to SPTLP.

Keywords: subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocyosis

Introduction

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL) is a rare entity within the spectrum of cutaneous lymphomas. 1 These lymphomas, which account for less than 1% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas, predominantly affect young adults, with a median age at diagnosis ranging from 30 to 40 years, and exhibit a slight female preponderance. 2

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, a cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma, presents clinically with nonspecific symptoms such as weight loss, low-grade fever, and general malaise in approximately half of the patients, while others may exhibit only localized signs. 3 Characteristically, patients develop multiple subcutaneous nodules or plaques, primarily on the extremities or trunk, with occasional involvement of rare sites like the mesentery.1,2 The differential diagnosis for SPTCL is broad, including various forms of panniculitis and lupus erythematosus panniculitis (LEP).2,3 Laboratory findings in patients with SPTCL often reveal cytopenia and elevated liver function tests.1-3

Diagnosing SPTCL poses a challenge due to its overlapping features with nonneoplastic panniculitides and other T-cell lymphomas. Histologically, it is marked by lymphocytic infiltrates predominantly involving the fat lobules, sparing the septa, and characterized by atypical lymphocytes with irregular, hyperchromatic nuclei rimming individual fat cells. 4

Immunohistochemically, neoplastic cells in SPTCL express an α/β cytotoxic T-cell phenotype, including markers such as CD8, TIA1, granzyme B, and perforin, but not CD56 and CD4.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has reclassified SPTCL into 2 distinct phenotypes based on T-cell receptor (TCR) expression. The α/β T-cell phenotype (CD8+, CD4−, CD56−) is associated with SPTCL and generally has a favorable prognosis, often responding well to immunosuppressive treatments. Conversely, primary cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma (PCGD-TCL; eg, CD4−, CD8−, CD56+) is linked to a poorer prognosis, with both phenotypes expressing granzyme B, perforin, and TIA1. 5

In addition, panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma can be complicated by hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) in 15% to 25% of cases. 6 Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is a severe systemic inflammatory syndrome characterized by an overproduction of cytokines from activated T cells and histiocytes. 7 This condition can be triggered by various neoplastic and nonneoplastic factors, including viral infections and rheumatic diseases, and is histopathologically identified by the widespread accumulation of lymphocytes and macrophages in multiple organs.3,6,7

Case Presentation

A 20-year-old male, with no known history of allergies, presented with symptoms initiating approximately 3 months before hospital admission. Clinical manifestations included persistent high fever and the development of dark red, oval-shaped, firm skin plaques, ranging from 4 to 8 cm in diameter, on the chest, back, and waist. Initial treatment comprised 32 mg/day of Medrol and topical Tacrolimus, leading to the resolution of fever and decreased skin inflammation. The patient was discharged with ongoing topical therapy. However, 3 weeks preceding the current hospitalization, he experienced a continuous fever between 38°C to 39°C, alongside the emergence of dark brown pigmented patches on the chest, abdomen, waist, lower leg, which were tender but not indurated (Figure 1). Concurrent ankle pain exacerbated by movement was also reported. Subsequent admission to hospital was for further evaluation and management. Notable test results were presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Patient photographs showed lesions presenting as erythematous plaques and nodules (arrows) on the skin of the right lower leg (A) and abdomen (B).

Table 1.

Notable Test Results From Our Patient.

| Laboratory tests -WBC: 0.5 G/L (normal, 3.6-11.2); NEU: 0.2 G/L (normal, 1.8-7.8), RBC: 2.57 T/L (normal, 3.73-5.5), PLT: 57 G/L (normal, 159-386). -PT: 13.5 seconds (normal, 9.4-12.5); APTT: 48.8 seconds (normal, 27-37); Fibrinogen: 0.62 G/L (normal, 2-4). -GOT: 623 U/L (normal, 0-35); GPT: 296 U/L (normal, 0-45); Total Bilirubin: 208.1 μmol/L (normal, 5-21); Direct Bilirubin: 121.8 μmol/L (normal, 0-3.4); NH3: 39.7 μmol/L (normal, 10-48); Albumin: 28.1 g/L (normal, 35-53); CK: 1026 U/L (normal, 0-171); LDH: 4482 U/L (normal, 0-248). -Ferritin: 706-580 ng/ml (normal, 11-336.2), Triglycerides: 5.8-4.5 mmol/L (normal, 0-1.7), D-dimer: 209576 (normal, 0-255). |

| Bone marrow aspiration: Reduced bone marrow cellularity. |

| Chest computed tomography: Mild collapse, interstitial thickening, and consolidation in the lower lobes of both lungs. Bilateral pleural effusion, pericardial effusion. Edema of the skin and subcutaneous tissue in the chest area. Several reactive lymph nodes in the axillary area, inflammatory. |

| Abdominal ultrasound: Enlarged liver and spleen. |

| Testing for 18 autoantibodies was negative. |

| ANA 8 profile was negative. |

| First skin biopsy: No pathological findings in the skin tissue (a full biopsy including the subcutaneous fat was not obtained due to coagulation disorder). |

The patient was diagnosed with HLH and acute liver failure, warranting close monitoring for systemic disease, not excluding malignancies such as SPTCL and HLH. The treatment regimen included pulse therapy with methylprednisolone at 1 g/day and cyclosporin at 6 mg/kg/day, supplemented with oxygen therapy, granulocyte-stimulating agents, correction of coagulation abnormalities, prophylaxis against bleeding, and hepatoprotective measures.

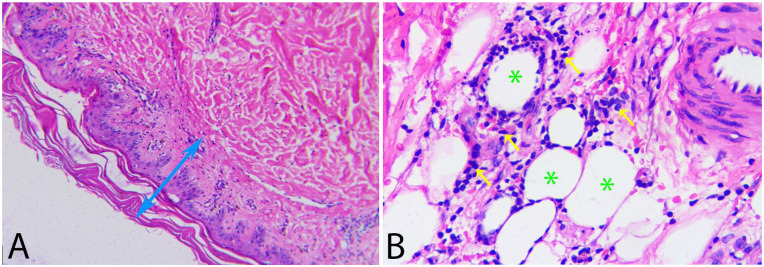

Despite initial treatment, the patient’s condition deteriorated, marked by progressive respiratory failure. This necessitated 2 plasma exchange sessions, IVIG transfusion, escalation of antibiotic therapy, and continued administration of solumedrol at 80 mg/day and cyclosporin at 6 mg/kg/day, along with high-flow nasal cannula oxygen support. A subsequent skin biopsy, the second of its kind, led to a definitive diagnosis of SPTCL. Histological examination revealed a normal epidermis and dermis, but with extensive infiltration of atypical lymphocytes in the subcutaneous fat layer, clustering around adipocytes, displaying hyperchromatic and irregularly bordered nuclei of small to medium size (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining showed positivity for CD3, a high proliferation index with Ki-67 (+, 50%), and positivity for CD8, with negativity for CD20, CD4, and CD56 (Figure 3). In light of the poor response to treatment, the patient’s clinical course worsened, culminating in his demise.

Figure 2.

Microscopic images of hematoxylin-eosin staining sections: (A) Normal appearance of the epidermal and dermal layers (double-headed arrow, 200× magnification). (B) Subcutaneous fat layer infiltrated with numerous atypical lymphocytes (arrows), clustering around the periphery of fat cells (asterisks), with hyperchromatic nuclei, irregular nuclear membranes, and ranging in size from small to medium (400× magnification).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical staining images showed that tumor cells positive for CD3 (A, 400× magnification) and CD8 (B, 400× magnification), with stained brown-yellow; negative for CD4 (C, 400× magnification) and CD56 (D, 400× magnification).

Classification

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma is a distinct type of T-cell lymphoma, first identified in a series of 8 cases in 1991.2,3,5 It was not until 2001 that the WHO officially recognized it as a unique entity. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma predominantly affects individuals in their late thirties, with the median age at diagnosis being 39 years WHO Reclassification and Phenotypic Distinctions.3-5 Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma was initially divided into 2 phenotypes, a classification that the WHO has since revised. World Health Organization’s reclassification now identifies 2 distinct phenotypes of SPTCL based on TCR expression.1,4,7 The α/β T-cell phenotype, characterized by CD8+, CD4−, and CD56− expression, is commonly associated with SPTCL and tends to have a favorable prognosis, often responding well to immunosuppressive therapy. In contrast, the phenotype known as PCGD-TCL, marked by CD4-, CD8-, and CD56+ expression, is generally linked to a poorer prognosis. Both phenotypes are characterized by the expression of granzyme B, perforin, and TIA1.2,5,8

Epidemiology and Clinical Presentation

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, a rare form of skin lymphoma, predominantly affects young adults, typically presenting between the ages of 30 and 40 years. This disease shows a slight female predominance and accounts for less than 1% of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases. 2 Patients with SPTCL usually exhibit multiple, painless subcutaneous plaques or nodules, primarily located on the trunk and extremities. Some of these nodules may spontaneously regress, while others may appear at different sites. Common systemic symptoms include fevers, chills, night sweats, weight loss, and myalgias. The differential diagnosis for SPTCL is broad and includes various skin conditions such as eczema, psoriasis, dermatitis, cellulitis, and LEP.2,5 In addition, a notable percentage of SPTCL patients, up to 20%, may present with coexisting autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus (LE).6,8

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

Histopathologically, SPTCL is identified by a dense infiltration of lymphocytes and histiocytes into subcutaneous fat tissue, often arranged in a lobular pattern with fat necrosis. The atypical lymphocytes exhibit irregular hyperchromatic nuclei, and a defining feature is the rimming of individual fat spaces by neoplastic lymphocytes. 9 Immunohistochemically, the presence of predominantly CD8+ T-lymphocytes, along with the absence of septal fibrosis, B-cell follicles, and plasma cells, helps distinguish SPTCL from conditions like LEP. 10

We conducted additional immunohistochemical tests to supplement the histopathological diagnosis of this case, particularly for differential diagnosis, especially distinguishing it from Primary Cutaneous Gamma-Delta T-cell Lymphoma (PCGD-TCL). In SPTCL, the expression of CD3 (+), CD8 (+), CD4 (−), CD56 (−), with strong expression of cytotoxic proteins: Granzyme B, TIA-1, and perforin (secreted by tumor cells) and Alpha/beta TCR (+), Gamma TCR (−), and high Ki67. The immunohistochemical results are consistent with SPTCL, showing positive expression in tumor cells for CD3, CD8, negative for CD4 and CD56, and high Ki67 about 50%.8-10

Differential Diagnosis

In a comprehensive analysis of the differential diagnosis of SPTCL, there are several different diagnoses to consider, including LE, primary cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma (PCGD-TCL), and extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type (ENKTL). Key differences were observed in clinical presentation, histopathology, immunohistochemistry, prognosis, treatment, and associated conditions, as summarized in Table 2.2,5,7,10,11

Table 2.

Differential Diagnosis of STCCL with Lupus Erythematosus (LE), Primary Cutaneous Gamma-Delta T-cell Lymphoma (PCGD-TCL), and Extranodal Natural Killer/T-cell Lymphoma, Nasal Type (ENKTL).2,5,7,10,11.

| Condition | SPTCL | LE | PCGD-TCL | ENKTL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical presentation | Typically presents with subcutaneous plaques or nodules on lower extremities, upper extremities, and trunk. Systemic symptoms like fever and hepatosplenomegaly may be present. | More commonly presents on the face and proximal extremities. Fever and hepatosplenomegaly can also be observed. | Prefers middle-aged adults. Lesions may be superficial with surface ulceration. Systemic symptoms and lymphadenopathy are common. | May present with subcutaneous involvement. |

| Histopathology | Dense infiltration of lymphocytes and histiocytes into subcutaneous fat tissue, often with rimming of individual fat spaces by neoplastic lymphocytes. | Involvement of the epidermis, interface change, a mixture of CD4 and CD8 T-cells, lymphoid follicles, and plasma cell aggregates. | Three patterns observed: epidermotropic, dermal, and subcutaneous. The subcutaneous pattern can resemble SPTCL but with less prominent rimming of adipocytes. | Positive for EBV, distinguishing it from SPTCL. |

| Immunohistochemistry | Expresses α/β cytotoxic T-cell phenotype, including CD8, TIA1, granzyme B, and perforin, but not CD56 and CD4. | Shows a mixture of CD4 and CD8 T-cells, CD123+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells, and plasma cells. | Positive for CD56, TCR gamma, TIA1, granzyme B, and perforin. Typically, negative for CD4, CD8, and beta F1. | Distinctive for its EBV positivity. |

| Prognosis and treatment | Generally favorable prognosis. Treated effectively with immunosuppressive medication. | Variable prognosis depending on the severity and organ involvement. Treated with immunosuppressants and steroids. | Poor prognosis with a 5-year survival of 10%. Treatment includes aggressive chemotherapy. | Aggressive lymphoma with variable prognosis. Treatment includes chemotherapy and possibly stem cell transplantation. |

| Associated conditions | Associated with HLH in 15%-20% of cases. | Up to 20% of patients have an associated autoimmune disease like systemic lupus erythematosus. | HLH develops in 50% of cases. | - |

Association With HLH

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma can be complicated by HLH in 15% to 20% of cases.6,9 Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is a severe systemic inflammatory response triggered by overactive cytokines produced by activated T-cells and histiocytes. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis can be induced by both neoplastic and nonneoplastic agents, including viruses and rheumatic diseases. Histopathologically, HLH is characterized by widespread accumulation of lymphocytes and mature macrophages in organs like the spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow, liver, and cerebrospinal fluid.3,4,12

In our patient, tests indicated a reduction in blood cell lines and elevated liver enzymes, with hepatosplenomegaly suggesting accompanying HLH. During the second hospital admission of our patient, a more severe condition of the disease was recorded, with accompanying HLH manifesting in the second week after admission. Although the bone marrow biopsy did not show abnormalities, the patient met 5 out of 8 diagnostic criteria for HLH according to the Histiocyte Society, including (1) continuous high fever over 38.5°C for more than 7 days, (2) enlarged spleen, (3) increased blood triglycerides over 3 mmol/l (normal, <1.7), (4) increased ferritin >500 ng/mL (normal, Male: 12-300, Female: 12-150), (5) decreased blood fibrinogen ≤1.5 g/L (normal, 2.0-4.0). Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is a rare disorder associated with abnormal activation of T cells and natural killer cells, leading to a significant increase in cytokines in the blood, loss of macrophage control, resulting in excessive phagocytosis in the endothelial reticulum system.2,5,7,12

Treatment

Regarding treatment, polychemotherapy with one or more drugs was once considered the standard for treating SPTCL and PCGD-TCL when both diseases were viewed as a single entity. However, due to the differing prognoses of the 2 diseases, in 2008, the WHO distinguished them as separate entities. Currently, there is still no standard treatment method for SPTCL. 1 Studies have indicated that most cases are successfully treated with systemic corticosteroids or immunosuppressants such as etoposide, cyclosporine A, methotrexate, chlorambucil, and bexarotene.2,9,13

In patients with accompanying HLH, the selected treatment is high-dose corticosteroids combined with cyclosporin A or stem cell transplantation with chemotherapy.12,14 Our patient initially received corticosteroid treatment upon admission, with the dosage gradually increased as the disease progressed. When the patient developed accompanying HLH, in addition to treatments for multiorgan damage such as plasma exchange and coagulation disorder management, the patient was also given pulse therapy with high-dose corticosteroids combined with cyclosporine at a dose of 6 mg/kg/day. However, the patient’s condition deteriorated and eventually led to death.

Prognosis

While SPTCL typically does not involve lymph nodes, there have been atypical cases exhibiting extracutaneous involvement, particularly in the mesentery. These instances tend to be more aggressive, unresponsive to multiagent chemotherapy, and are associated with a poorer prognosis. 15 Such atypical presentations highlight the importance of comprehensive clinical and histopathological evaluations to inform suitable treatment strategies.

Prognostically, most SPTCL cases have a favorable outlook, characterized by slow progression and a 5-year survival rate ranging from 85% to 91%, with a low risk of nodal or systemic spread. 4 Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis occurs in 15% to 20% of cases and is linked to a poor prognosis, with only 46% of patients surviving beyond 5 years. In our patient, HLH developed in the later stages of the disease, leading to rapid and severe progression. Despite intensive and multidisciplinary treatment efforts, the patient ultimately succumbed to complications including sepsis, liver damage, and severe coagulopathy.

Transcriptomic Profiling and Molecular Mechanisms

Recent transcriptomic profiling analyses have provided insights into disease-related enrichment pathways and gene functions in SPTCL patients. This research may illuminate molecular mechanisms driving disease activity, offering potential targets for novel therapeutic interventions. 16

Conclusion

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, a complex and potentially life-threatening condition, requires a nuanced approach to diagnosis and treatment. The distinction between its phenotypes, based on histopathological and immunohistochemical characteristics, is crucial for guiding treatment strategies and predicting prognosis. Early recognition and treatment, especially in cases complicated by HLH, are vital for improving patient outcomes.

Footnotes

Author’s Note: The case was partially presented at the 4th Vietnamese French cancer conference in 2023.

Data Availability Statement: The data that support the findings of this work are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: No ethical approval is required.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s family for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

ORCID iDs: Khac Tuyen Nguyen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6056-4997

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6056-4997

Van Trung Hoang  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7857-4387

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7857-4387

References

- 1. Parveen Z, Thompson K. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-Cell lymphoma: redefinition of diagnostic criteria in the recent World Health Organization-European organization for research and treatment of cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(2):303-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bagheri F, Cervellione KL, Delgado B, et al. An illustrative case of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. J Skin Cancer. 2011;2011:824528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Willemze R, Jansen PM, Cerroni L, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: definition, classification, and prognostic factors: an EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Group Study of 83 cases. Blood. 2008;111:838-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sugeeth MT, Narayanan G, Jayasudha AV, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2017;30:76-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hrudka J, Eis V, Heřman J, et al. Panniculitis-like T-cell-lymphoma in the mesentery associated with hemophagocytic syndrome: autopsy case report. Diagn Pathol. 2019;14:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Geller S, Myskowski PL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz SM, Moskowitz AJ. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), rare subtypes: five case presentations and review of the literature. Chin Clin Oncol. 2019;8(1):5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yuan L, Sun L, Bo J, et al. Durable remission in a patient with refractory subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation through withdrawal of cyclosporine. Ann Transplant. 2011;16(3):135-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. López-Lerma I, Peñate Y, Gallardo F, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: clinical features, therapeutic approach, and outcome in a case series of 16 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(5):892-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Salhany KE, Macon WR, Choi JK, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and genotypic analysis of alpha/beta and gamma/delta subtypes. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22(7):881-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Magro CM, Crowson AN, Kovatich AJ, Burns F. Lupus profundus, indeterminate lymphocytic lobular panniculitis and subcutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a spectrum of subcuticular T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28(5):235-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Musick SR, Lynch DT. Subcutaneous Panniculitis-Like T-Cell Lymphoma. StatPearls Publishing. Accessed 1 March 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538517 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Janka GE. Hemophagocytic syndromes. Blood Rev. 2007;21:245-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ohtsuka M, Miura T, Yamamoto T. Clinical characteristics, differential diagnosis, and treatment outcome of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: a literature review of published Japanese cases. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:34-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nusshag C, Morath C, Zeier M, Weigand MA, Merle U, Brenner T. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in an adult kidney transplant recipient successfully treated by plasmapheresis: A case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(50):e9283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mody A, Cherry D, Georgescu G, et al. A rare case of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T cell lymphoma with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis mimicking cellulitis. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:e927142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li X, Severson KJ, Patel MH, et al. Comparative transcriptomics of alpha-beta subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma and primary cutaneous gamma delta T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2020;136:17. [Google Scholar]