Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate the clinical safety and efficacy of stent-assisted coil embolization of unruptured wide-necked paraclinoid aneurysms based on the projection distribution.

Methods

Between November 2015 and September 2020, 267 unruptured paraclinod aneurysms in 236 patients were identified with a wide neck or unfavorable dome-to-neck ratio and treated with stent-assisted coiling technique. The classification of this segment aneurysms was simplified to the dorsal group (located on the anterior wall) and ventral group (Non-dorsal). Following propensity score matching analysis, the clinical and radiographic data were compared between the two groups.

Results

Among 267 aneurysms, 186 were located on the ventral wall and 81 were on the dorsal wall. Dorsal wall aneurysms had a larger size (p < .001), wider neck (p = .001), and higher dome-to-neck ratio (p = .023) compared with ventral wall aneurysms. Propensity score-matched analysis found that dorsal group had a significantly higher likelihood of unfavorable results in immediate (residual sac, 39.4% vs. 18.2%, p = .007) and follow-up angiography (residual sac, 14.8% vs. 1.9%, p = .037) compared with ventral group, with significant difference in recurrence rates (9.3% vs. 0%, p = .028). The rates of procedure-related complications were not significantly different, but one thromboembolic event occurred in the dorsal group with clinical deterioration.

Conclusions

Traditional stent-assisted coiling can be given preference in paraclinoid aneurysms located on the ventral wall. The relatively high rate of recurrence in dorsal wall aneurysms with stent assistance may require other treatment options.

Keywords: Paraclinoid aneurysm, stent, coil embolization

Introduction

Paraclinoid aneurysms are defined as aneurysms arising from the internal carotid artery (ICA) from the distal origin of the dural ring to the posterior communicating artery, and they account for about 5% of the intracranial aneurysms. 1 The complex adjacent anatomy poses a major technical challenge for microsurgical treatment of these aneurysms.2,3 With the development of novel devices and the need for less invasive treatment, an increasing number of paraclinoid aneurysms are referred for endovascular treatment.4–11

Flow diversion has been a promising treatment strategy for paraclinoid aneurysms in the quest for a more effective treatment aiming for stable aneurysmal exclusion, but the technique of stents in embolization of wide-necked paraclinoid aneurysms is still used in treating routine aneurysms.8,10–16 Previous studies have reported that the dorsally located aneurysms may increase the technical difficulty of endovascular embolization due to the unfavorable aneurysmal geometries and the severe curvature of the carotid siphon.17,18 However, the comparative data of characteristics and treatment results with stent application in different projections of paraclinoid aneurysms are limited. In this study, we sought to compare clinical and angiographic outcomes of wide-necked paraclinoid aneurysms after stent assistance based on different projections following propensity score matching analysis.

Materials and methods

Patient and aneurysm description

From November 2015 to September 2020, a total of 235 consecutive patients with 267 unruptured wide-necked paraclinoid aneurysms using the stent-assisted coiling technique were included in this study. The selection criteria were as follows: (1) unruptured aneurysms arising from the distal origin dural ring to the posterior communicating artery, (2) treated with stent-assisted coiling technique due to wide-necked aneurysms, and (3) complete clinical and imaging data. Patients were excluded if they were treated with flow diversion. Wide-necked aneurysms were defined as aneurysms with a neck size ≥ 4 mm or an unfavorable dome-to-neck ratio < 2 as measured on digital subtraction angiography (DSA). The aneurysms larger than 7 mm were considered for endovascular treatment due to a high risk of rupture. 6 Small aneurysms (3–7 mm) were generally treated in our study under the following conditions: multiple aneurysms, aneurysms present with irregular shape or a daughter sac, family history of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), or patients with deep anxiety. In our study, paraclinoid dorsal wall aneurysms were generally defined as aneurysms that arose from the anterior wall and projected superiorly, while ventral wall aneurysms were defined as aneurysms that arose from the medial, lateral, or inferior wall of paraclinoid ICA and aneurysmal projection is in any direction except superior on the anterior wall. 18 Based on the risk of rupture, aneurysm size was classified as small (< 7 mm) or large (≥ 7 mm). 6 Patient characteristics, procedure details, and follow-up outcomes were prospectively recorded in our hospital. Based on the retrospective study design, the requirement for patient informed consent for study inclusion was waived and this study was approved by our institutional review board.

Procedural details

The procedure was conducted under general anesthesia. After the deployment of a 6-French Envoy guiding catheter (Cordis, Miami Lakes, FL, USA), systemic heparinization was performed by administering with a loading dose of 70 IU/kg intravenously and maintained with an additional dose of 1000 IU per hour to activate the clotting time at 2–2.5 times the patient's baseline level during the procedure. The semi-jailing technique was used in all cases. The microcatheter with predetermined shape (Headway-17, MicroVention Tustin, CA, USA) was manipulated over a microwire and navigated into the aneurysms. The aneurysms were packed with detachable coils after the stent was partially deployed to prevent distal coil protrusion into the parent artery. The stents used for treatment included Neuroform EZ stent (Stryker Neurovascular Fremont, Cork, Ireland), Lvis stent (Micro Vention Tustin, California, USA), and Enterprise stent (Codman Neurovascular, Raynham, MA). Immediate angiographic outcome after the procedure was performed to assess the exact degree of aneurysm occlusion. (The illustrative cases were given in Figure 1 and Figure 2)

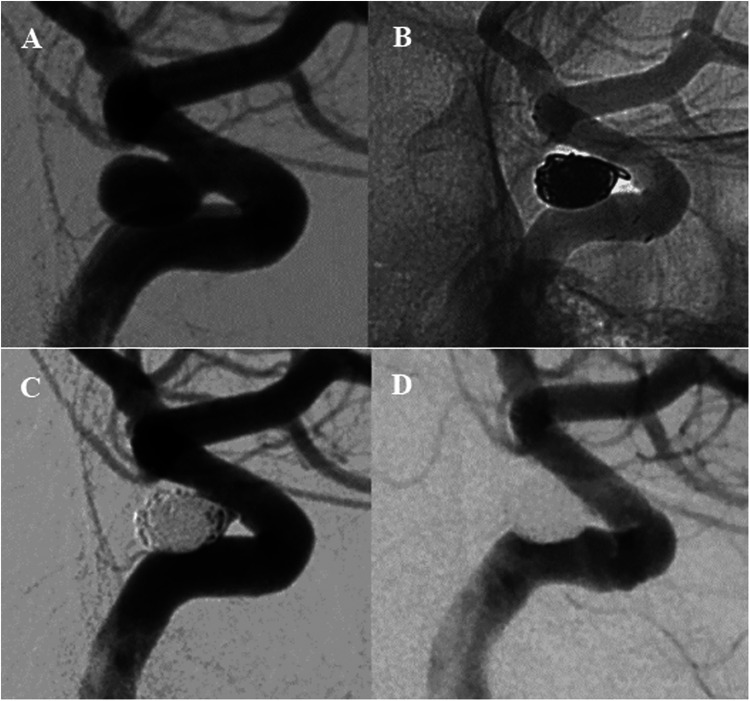

Figure 1.

Cerebral angiography (A) before endovascular treatment showed a wide-necked paraclinoid aneurysm located on the ventral wall. (B, C) Stent-assisted coiling technique was performed during the procedure and angiography immediately showed incomplete occlusion of the aneurysm sac. Angiographic follow-up at 6-month (D) demonstrated complete occlusion of the aneurysm sac.

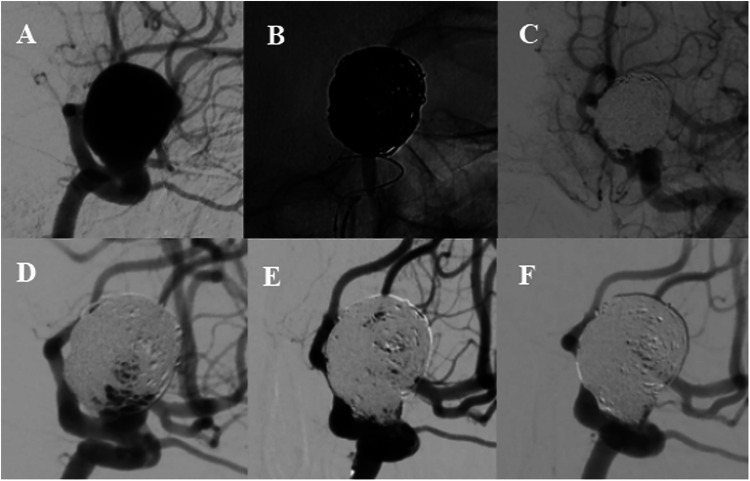

Figure 2.

Cerebral angiography (A) demonstrated a wide-necked paraclinoid aneurysm located on the dorsal wall. (B) Stent-assisted coiling technique was used during the procedure and immediate angiography image (C) showed residual aneurysm occlusion. Follow-up angiography at 6 months (D) indicated a recurrence, and re-coiling was performed (E). Angiogram (F) at 12-month showed complete aneurysm occlusion.

Patients with the stent-assisted technique were routinely pretreated with pharmacological therapy, including a regimen of aspirin 100 mg and clopidogrel 75 mg per day for at least 5 days. After discharge, patients were required with daily 100 mg/day aspirin and 75 mg/day clopidogrel orally for 3 months, and daily aspirin at 100 mg/day for an additional 6 months.

Outcomes assessment

Procedure-related complications included intraprocedural aneurysm rupture, thromboembolic events, or neurological deficit with visual impairment. The follow-up angiography was performed about 6 months after the procedure, and subsequent computed tomography (CT) angiography or magnetic resonance (MR) angiography 1 year after the first follow-up angiography was recommended. The angiographic results were collected and the aneurysm occlusion degree was classified as complete obliteration (Raymond 1), neck remnant (Raymond 2), and residual aneurysm (Raymond 3). 19 Recurrence was defined as an increase in the contrast flow filling at follow-up imaging. Clinical outcomes were evaluated by using the modified Rankin scale (mRS) score and good outcomes were defined as an mRS of 0–2. The mRS scores at 6 months were obtained from the clinic or telephonic interview.

Statistics analysis

Continuous variables were described as mean (standard deviation, SD) or medians (interquartile range, IQR) and categorical variables as frequencies (%). The Student's t-test or a Mann-Whitney U test was performed to analyze continuous data. The Fisher exact or χ2 test was used for the analyzes of categorical data. The statistical significance threshold was α = 0.05. One-to-one propensity score-matched analysis were performed by using the nearest neighbor method. Statistical analyzes were carried out with SPSS Statistic 20 (IBM- Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

Patient and aneurysm characteristics

Among the 236 patients, the mean age was 58.9 years (SD, 9.8), and 183 of them (77.5%) were female. Sixty-one of the 236 patients (25.8%) had multiple aneurysms. The mean aneurysm size of dorsal group aneurysms was significantly larger than that of ventral group aneurysms (6.1 ± 6.6 vs. 4.8 ± 2.3, p < .001). In addition, the dorsal group aneurysms had a lager neck width (4.7 ± 2.4 vs. 3.7 ± 1.3, p < .001) and dome to neck ratio (1.5 ± 0.5 vs. 1.2 ± 0.3, p = .001) compared with ventral group aneurysms. Patients in the dorsal wall group were more likely to be associated with multiple aneurysms (p < .001). The comparisons of baseline characteristics between the two groups were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison between ventral and dorsal cohort, before propensity score matching.

| Variable | Ventral Group (n = 186) | Dorsal Group (n = 81) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 59.1 ± 10.0 | 58.6 ± 9.7 | 0.736 | |

| Female gender | 132 (76.7) | 60 (77.9) | 0.081 | |

| Multiple aneurysms | 40 (23.3) | 36 (46.8) | <.001 | |

| Hypertension | 99 (53.2) | 33 (40.7) | 0.061 | |

| Size of aneurysm, mm | 4.8 ± 2.3 | 6.1 ± 6.6 | <.001 | |

| 3-7 mm | 162 (85.7) | 57 (70.4) | ||

| ≥ 7 mm | 24 (14.3) | 24 (29.6) | ||

| Neck width, mm | 3.8 ± 1.3 | 4.7 ± 2.4 | 0.001 | |

| Dome-to-neck ratio | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 0.023 | |

| Procedure times, min | 82.5 ± 16.2 | 91.5 ± 21.2 | 0.386 | |

| Procedure-related complications | 3 (1.6) | 3 (3.7) | 0.541 | |

| Immediate angiography results | <.001 | |||

| Complete and near complete occlusion | 162 (87.1) | 48 (59.3) | ||

| Residual sac | 24 (12.9) | 33 (40.7) | ||

| Completed angiography follow-up | 152 (81.7) | 66 (81.5) | ||

| Follow-up angiography results | <.001 | |||

| Complete and near complete occlusion | 149/152 (98.0) | 55/66 (83.3) | ||

| Residual sac | 3/152 (2.0) | 11/66 (16.7) | ||

| Recurrences | 1/152 (0.7) | 6/66 (9.1) | 0.003 | |

| Retreatment | 0 | 4/66 (6.1) | 0.008 |

Endovascular details and angiographic outcomes

The stent-assisted technique was used in all aneurysms. The number of stents used with Neuroform EZ, Enterprise, and Lvis were 185 (69.3%), 35 (13.1%), and 47 (17.6%). The immediate complete occlusion rate was 54.1% and progressed to 82.1% at follow-up angiography with an average time of 7.2 ± 6.4 months (range 5–16 months).

In the ventral group, post-procedure angiography showed that the complete occlusion and neck remnants were achieved in 162 aneurysms (87.1%), and residual aneurysm occlusion was observed in 24 aneurysms (12.9%). Follow-up angiography was available in 146 patients with 152 ventral wall aneurysms, and 98.0% (149/152) of them had complete or near-complete occlusion after stent assistance at follow-up. Among 81 aneurysms in the dorsal group, complete occlusion and neck remnants after the procedure were achieved in 48 aneurysms (59.3%), and residual occlusion was obtained in 33 aneurysms (40.7%). Follow-up angiography at 6 months was available in 66 dorsal wall aneurysms, including 11 (16.7%) aneurysms with residual sac. Compared with ventral group aneurysms (Table 1), the dorsal group aneurysms had more unfavorable results at immediate (residual sac, 40.7% vs. 12.9%, p < .001) and follow-up radiological outcomes (residual sac, 16.7% vs. 2.0%, p < .001). The recurrences were more presented in the dorsal group (9.1% vs. 0.7%, p = .003). Four of 7 patients with recurrences underwent recoiling treatment after evaluation, and another three patients rejected the treatment and choose close follow-up.

Procedural complications and clinical outcome

In this study, the overall complications rate was 2.5%. Procedure-related complications occurred in three patients (1.6%) in the ventral group without permanent neurologic dysfunction. Among them, two patients experienced thromboembolic events, which resulted in transient morbidity. After intravenous administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, the symptoms subsided within a few days. Another patient was found with a prolapsing coil during the procedure that was compressed by another stent deployment. Three thromboembolic events were discovered in patients with dorsal wall aneurysms. Of the 3 patients, one patient developed acute thrombosis with severe vasospasm during stent placement, which did not improve after urokinase thrombolysis. Large cerebral infarction with cerebral edema was found on subsequent CT scans, resulting in a poor outcome after decompressive craniectomy. Another two patients experienced thromboembolic events without neurologic sequelae. There were no hemorrhagic complications. The rate of complications in the dorsal group was higher than that of the ventral group, but the difference was not significant (p = .541).

Clinical follow-up was available in all patients with an average time of 18.2 ± 12.4 months (range 3–42 months). Good clinical outcomes with an mRS score of 0–2 at 6-month were achieved in 235 patients (99.6%). One patient with serious procedure-related complications had an mRS score of 5 after decompressive craniectomy.

Propensity score matched analysis

Propensity score-adjusted characteristics and outcomes are shown in Table 2. Following 1:1 matching, 66 pairs from each dorsal and ventral group were matched after controlling for age, gender, hypertension, the presence of multiple aneurysms, maximal diameter, neck width, and dome-to-neck ratio, without statistical difference in demographic and clinical characteristics. Dorsal group had a significantly higher likelihood of unfavorable results in immediate (residual sac, 39.4% vs. 18.2%, p = .007) and follow-up angiography (residual sac, 14.8% vs. 1.9%, p = .037) compared with ventral group. The recurrence rates were significantly different between the dorsal and ventral groups (9.3% vs. 0%, p = .028). The rates of procedure-related complications and retreatment were not significantly different between the two groups.

Table 2.

Propensity score matching: controlled for age, gender, hypertension, multiple aneurysms, max diameter, neck width, dome-to-neck ratio.

| Variable | Ventral group (n = 66) | Dorsal group (n = 66) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 59.9 ± 9.2 | 58.9 ± 10.2 | 0.548 | |

| Female gender | 51 (77.3) | 51 (77.3) | 1.000 | |

| Hypertension | 35 (53.0) | 29 (43.9) | 0.296 | |

| Multiple anerusyms | 30 (45.5) | 29 (43.9) | 0.861 | |

| Size of aneurysm, mm | 5.3 ± 2.4 | 5.5 ± 2.6 | 0.648 | |

| Neck width, mm | 4.1 ± 1.7 | 4.1 ± 1.4 | 0.913 | |

| Dome-to-neck ratio | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.748 | |

| Procedure times, min | 83.5 ± 15.6 | 90.5 ± 20.4 | 0.314 | |

| Procedure-related complications | 1 (1.5) | 1 (3.7) | 1.000 | |

| Immediate angiography results | 0.007 | |||

| Complete and near complete occlusion | 54 (81.8) | 40 (60.6) | ||

| Residual sac | 12 (18.2) | 26 (39.4) | ||

| Completed angiography follow-up | 54 (81.8) | 54 (81.8) | ||

| Follow-up angiography results | 0.037 | |||

| Complete and near complete occlusion | 53/54 (98.1) | 46/54 (85.2) | ||

| Residual sac | 1/54 (1.9) | 8/54 (14.8) | ||

| Recurrences | 0 | 5/54 (9.3) | 0.028 | |

| Retreatment | 0 | 4/54 (7.4) | 0.118 |

Discussion

In this large cohort study, we retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of patients who underwent stent-assisted coiling procedures for wide-necked paraclinoid aneurysms. The simplified classification of this segment aneurysms was adopted based on the angiographic direction, which could guide us in clinical treatment strategies and microcatheter shaping, as reported by Oh et al. 18 Following the propensity score matching analysis, we found that paraclinoid aneurysms located on the dorsal wall had a higher likelihood of unfavorable results in immediate and follow-up angiography compared with ventral wall aneurysms, with a higher recurrence rate at follow-up.

The proportion of initial complete occlusion of paraclinoid aneurysms after standard endovascular treatment in previous reports ranged from 38% to 72.6%. 6 In our study, the immediate complete occlusion rate using the stent assistance technique was 54.1%, respectively. Furthermore, we found that immediate angiographic outcomes were more unfavorable in dorsal group aneurysms. The probable causes were that dorsal wall aneurysms often showed an irregular geometric shape and the microcatheter was relatively unstable due to abrupt curvature of the carotid siphon, which caused difficulty to achieve dense embolization with coiling. 20 In contrast, the operation of microcatheter reshaping and navigation techniques was easier in the posterior projection of the aneurysm.

Conventional coil embolization for the paraclinoid aneurysms is often considered prone to recanalization after endovascular treatment, which was varied from 5.0% to 23.1% in previous studies.4–6,9,17,21 In the present study, of our experience treating unruptured paraclinoid aneurysms using the traditional stent-assisted technique, we observed a stable progression toward complete aneurysm occlusion (84.1% at follow-up). The progression could possibly be attributed to subsequent thrombus formation around the coil mass and the effects of stent implantation.22,23 Regarding the choice of stents, the open-cell stent was recommended because this type of stent can potentially achieve good expansion and opposition to the wall in curving arterial segments and provide satisfactory coverage of the aneurysmal neck. 24 In addition, when we compared dorsal and ventral group aneurysms, statistically significant differences were found in terms of follow-up angiographic outcomes. Sugiyama et al. 25 reported that the degree of flexion of the ICA may change the hemodynamic stress and long-term outcomes following embolization of paraclinoid aneurysms. Kim et al. 26 showed that paraclinoid aneurysms at different locations had different hemodynamic stress and progressive embolization effect, which may be caused by the curvature and twist of vessels. The residual sac and recurrence were more found in dorsal group aneurysms in the present study, which could be explained by the larger ICA curve of dorsal wall aneurysms with higher hemodynamic stress compared with the ventral aneurysms.

The complications of coiling and stent-assisted coiling are essentially limited to thromboembolic events and intraprocedural aneurysmal rupture. Previous reports have found that the complication rate of endovascular treatment for paraclinoid aneurysms ranged from 1.4%∼15.4% and mortality was 0%.4–6,9,17 In our study, the overall complication was 2.5% and the mortality was 0%. No occlusion of the branch ophthalmic artery was found during the operation, and no hemorrhagic event was observed. Complications between the two groups were not significant but one serious procedure-related complication occurred in the dorsal group. These results indicated that the stent-assisted coiling treatment for unruptured paraclinoid aneurysms was relatively safe, especially in ventral aneurysms.

Flow diversion is considered a promising treatment strategy for complex paraclinoid aneurysms aiming for stable aneurysmal exclusion. Michael et al. 7 performed a retrospective analysis to compare outcomes of patients with paraclinoid aneurysms after flow-diverting stents (FDS) placement with those of patients after coiling, and they reported a higher rate of complete occlusion at the last follow-up angiography in patients with flow diversion treatment (89% vs. 78%). Similarly, Griessenauer et al. 15 reported the results of FDS treatment for 160 paraclinoid aneurysms, and they found a 92.1% rate of complete and near-complete occlusion at follow-up DSA. We found a satisfactory 98.1% rate in the ventral group and an 83.3% rate in the dorsal group regarding long-term complete and near-complete occlusion. It has been confirmed that FDS deployment can influence the anatomic changes of anatomic carotid siphon morphology and lead to changes in hemodynamics, which significantly increased the frequency of complete occlusion at follow-up. 27 Thus, FDS treatment may be considered as an alternative option for large dorsal group aneurysms with large ICA angles to reduce recurrence. A previously published meta-analysis showed that FDS treatment for intracranial aneurysms had a slightly higher procedural complication rate than with other conventional endovascular treatment methods. 13 The complication rates for treating paraclinoid aneurysms using the FDS varied from 8%-16% in the previous studies.7,14,15,28–30 We found a low complication rate of 2.5% in our study, and one patient with permanent neurologic dysfunction was seen in the dorsal group.

Several potential limitations should be mentioned in this study. First, this study has the inherent limitations of its retrospective design based on a single-center experience. Second, this group of paraclinoid aneurysms treated with several different types of stents may have heterogeneity, thus the results should be interpreted carefully. In addition, the lack of independent core lab adjudication and patient loss to follow-up may affect the interpretation of the results. Forth, intracranial aneurysms widely differ from each other regarding angles, three-axis dome and neck diameters, and types of carotid siphon that indirectly impact the endovascular strategy. Thus, the results cannot reliably predict the outcomes of individual cases. At last, most of the aneurysms included were small aneurysms, which may influence the external validity of the results.

Conclusions

Traditional stent-assisted coiling is more suitable for paraclinoid ventral aneurysms, with low rates of procedure-related complication and recurrence. The relatively high rate of recurrence in the paraclinoid dorsal aneurysms with stent assistance coiling technique suggests that FDS sometimes may be a better option, especially in large and complex aneurysms.

Footnotes

Contributors: Heng Ni; conception, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, drafting, revising, and approving the manuscript. Yu Hang, Sheng Liu, Zhen-Yu Jia, Hai-Bin Shi, Lin-Bo Zhao; conception, data acquisition, revising and approving the manuscript. Jai Shankar; conception, data interpretation, revising and approval of manuscript.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in the studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Based on the retrospective study design, the requirement for patient informed consent for study inclusion was waived.

ORCID iD: Heng Ni https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8537-3751

References

- 1.Day AL. Aneurysms of the ophthalmic segment. A clinical and anatomical analysis. J Neurosurg 1990; 72: 677–691. 1990/05/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yadla S, Campbell PG, Grobelny B, et al. Open and endovascular treatment of unruptured carotid-ophthalmic aneurysms: clinical and radiographic outcomes. Neurosurgery 2011; 68: 1434–1443. discussion 1443. 2011/01/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Jesus O, Sekhar LN, Riedel CJ. Clinoid and paraclinoid aneurysms: surgical anatomy, operative techniques, and outcome. Surg Neurol 1999; 51: 477–487. discussion 487–478. 1999/05/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogilvy CS, Natarajan SK, Jahshan S, et al. Stent-assisted coiling of paraclinoid aneurysms: risks and effectiveness. J Neurointerv Surg 2011; 3: 14–20. 2011/10/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Urso PI, Karadeli HH, Kallmes DF, et al. Coiling for paraclinoid aneurysms: time to make way for flow diverters? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 1470–1474. 2012/03/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimizu K, Imamura H, Mineharu Y, et al. Endovascular treatment of unruptured paraclinoid aneurysms: single-center experience with 400 cases and literature review. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016; 37: 679–685. 2015/10/31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva MA, See AP, Khandelwal P, et al. Comparison of flow diversion with clipping and coiling for the treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms in 115 patients. J Neurosurg 2018: 1–8. 2018/06/23. DOI: 10.3171/2018.1.JNS171774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Touze R, Gravellier B, Rolla-Bigliani C, et al. Occlusion rate and visual complications with flow-diverter stent placed across the ophthalmic artery’s origin for carotid-ophthalmic aneurysms: a meta-analysis. Neurosurgery 2019. 2019/06/20. DOI: 10.1093/neuros/nyz202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Li Y, Jiang C, et al. Endovascular treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms: 142 aneurysms in one centre. J Neurointerv Surg 2013; 5: 552–556. 2012/10/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kunert P, Wojtowicz K, Zylkowski J, et al. Flow-diverting devices in the treatment of unruptured ophthalmic segment aneurysms at a mean clinical follow-up of 5 years. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 9206. 2021/04/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun Y, Li Y, Li AM. Endovascular treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms. Interv Neuroradiol 2011; 17: 425–430. 2011/12/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walcott BP, Stapleton CJ, Torok CM, et al. Flow diversion for the treatment of an unruptured paraclinoid carotid artery aneurysm. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown 2017; 13: 537. 2017/08/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou G, Zhu YQ, Su M, et al. Flow-diverting devices versus coil embolization for intracranial aneurysms: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg 2016; 88: 640–645. 2015/11/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Maria F, Pistocchi S, Clarencon F, et al. Flow diversion versus standard endovascular techniques for the treatment of unruptured carotid-ophthalmic aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36: 2325–2330. 2015/08/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griessenauer CJ, Piske RL, Baccin CE, et al. Flow diverters for treatment of 160 ophthalmic segment aneurysms: evaluation of safety and efficacy in a multicenter cohort. Neurosurgery 2017; 80: 726–732. 2017/03/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adeeb N, Griessenauer CJ, Foreman PM, et al. Comparison of stent-assisted coil embolization and the pipeline embolization device for endovascular treatment of ophthalmic segment aneurysms: a multicenter cohort study. World Neurosurg 2017; 105: 206–212. 2017/06/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeon JY, Hong SC, Kim JS, et al. Unruptured non-branching site aneurysms located on the anterior (dorsal) wall of the supraclinoid internal carotid artery: aneurysmal characteristics and outcomes following endovascular treatment. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2012; 154: 2163–2171. 2012/10/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oh SY, Lee KS, Kim BS, et al. Management strategy of surgical and endovascular treatment of unruptured paraclinoid aneurysms based on the location of aneurysms. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2015; 128: 72–77. 2014/12/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raymond J, Guilbert F, Weill A, et al. Long-term angiographic recurrences after selective endovascular treatment of aneurysms with detachable coils. Stroke 2003; 34: 1398–1403. 2003/05/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon BJ, Im S-H, Park JC, et al. Shaping and navigating methods of microcatheters for endovascular treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2010; 67: 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lv N, Zhao R, Yang P, et al. Predictors of recurrence after stent-assisted coil embolization of paraclinoid aneurysms. J Clin Neurosci 2016; 33: 173–176. 2016/08/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King RM, Chueh JY, van der Bom IM, et al. The effect of intracranial stent implantation on the curvature of the cerebrovasculature. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 1657–1662. 2012/04/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawson MF, Newman WC, Chi YY, et al. Stent-associated flow remodeling causes further occlusion of incompletely coiled aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2011; 69: 598–603. discussion 603–594. 2011/03/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ni H, Zhao LB, Liu S, et al. Open-cell stent-assisted coiling for the treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms: traditional endovascular treatment is still not out of date. Neuroradiology 2021; 63: 1521–1530. 2021/02/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sugiyama N, Fujii T, Yatomi K, et al. Endovascular treatment for lateral wall paraclinoid aneurysms and the influence of internal carotid artery angle. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2021; 61: 275–283. 2021/03/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JJ, Yang H, Kim YB, et al. The quantitative comparison between high wall shear stress and high strain in the formation of paraclinoid aneurysms. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 7947. 2021/04/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waihrich E, Clavel P, Mendes G, et al. Influence of anatomic changes on the outcomes of carotid siphon aneurysms after deployment of flow-diverter stents. Neurosurgery 2018; 83: 1226–1233. 2018/02/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lanzino G, Crobeddu E, Cloft HJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of flow diversion for paraclinoid aneurysms: a matched-pair analysis compared with standard endovascular approaches. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 2158–2161. 2012/07/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moon K, Albuquerque FC, Ducruet AF, et al. Treatment of ophthalmic segment carotid aneurysms using the pipeline embolization device: clinical and angiographic follow-up. Neurol Res 2014; 36: 344–350. 2014/03/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burrows AM, Brinjikji W, Puffer RC, et al. Flow diversion for ophthalmic artery aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016; 37: 1866–1869. 2016/06/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]