Abstract

To study in vivo tRNA3Lys genomic placement and the initiation step of reverse transcription in human immunodeficiency virus type 1, total viral RNA isolated from either wild-type or protease-negative (PR−) virus was used as the source of primer tRNA3Lys/genomic RNA templates in an in vitro reverse transcription assay. At low dCTP concentrations, both the rate and extent of the first nucleotide incorporated into tRNA3Lys, dCTP, were lower with PR− than with wild-type total viral RNA. Transient in vitro exposure of either type of primer/template RNA to NCp7 increased PR− dCTP incorporation to wild-type levels but did not change the level of wild-type dCTP incorporation. Exposure of either primer/template to Pr55gag had no effect on initiation. These results indicate that while Pr55gag is sufficient for tRNA3Lys placement onto the genome, exposure of this complex to mature NCp7 is required for optimum tRNA3Lys placement and initiation of reverse transcription.

The initial stages of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) assembly involve the interaction of the precursor protein Pr55gag with itself and with Pr160gag-pol. During or after budding, Pr55gag is cleaved by viral protease to the mature viral proteins, which include matrix, capsid, nucleocapsid, and p6; Pr160gag-pol is cleaved by viral protease into matrix, capsid, nucleocapsid, and the viral enzymes protease, reverse transcriptase (RT), and integrase (20). Viral genomic RNA (1) and cellular tRNALys (15) are also selectively packaged into the virus during assembly of the precursor proteins. One of the tRNALys isoacceptors, tRNA3Lys, binds to the primer binding site (PBS) on the genomic RNA, where it acts as the primer for initiation of reverse transcription. Both the selective incorporation of tRNA3Lys (17) and its placement onto the PBS (12) occur independently of precursor protein processing, and work has shown that while Pr160gag-pol is required for selective packaging of tRNA3Lys into Pr55gag particles (17), Pr55gag plays a major role in placing tRNA3Lys onto the PBS (3, 6).

While primer tRNA interacts with the PBS via the 3′-terminal 18 nucleotides of the primer tRNA, chemical and enzymatic probing and computer modeling indicate that additional interactions occur between regions upstream of the HIV-1 PBS and the D, TΨC, and anticodon loops of tRNA3Lys (13, 14). It is thus likely that extensive denaturation of tRNA3Lys, as well as the genomic RNA region containing the PBS, occurs during and after its placement onto the viral RNA genome. In HIV-1, mature nucleocapsid protein NCp7 facilitates the in vitro annealing of tRNA3Lys to in vitro-transcribed genomic RNA sequence (5), probably by unwinding the secondary structure of tRNA3Lys in vitro (16), and the stem-loop structures in the PBS area of the genomic RNA (14). Nevertheless, genomic placement of tRNA3Lys onto the PBS in vivo does not require precursor proteolysis (12). Although mature NCp7 does not appear to be required for the initial genomic placement of tRNA3Lys, we provide evidence in this work that it does optimize the final placement of the primer tRNA3Lys onto the PBS.

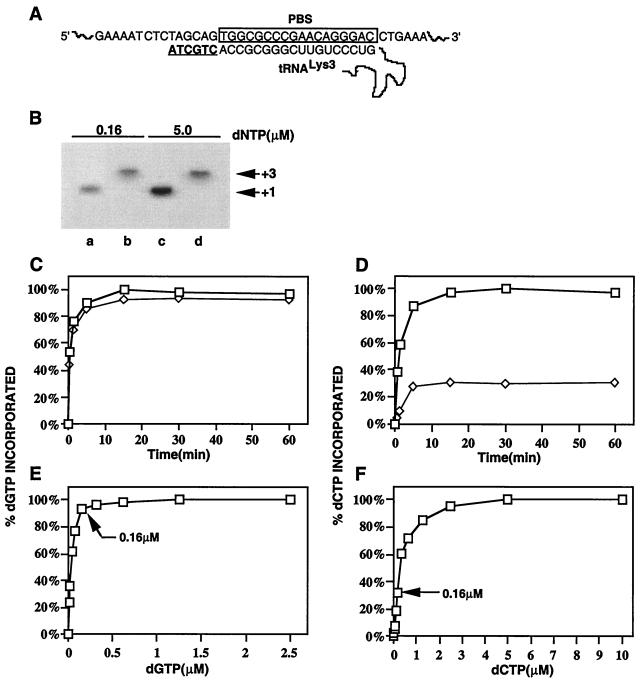

Figure 1A shows the first six deoxyribonucleotides incorporated during reverse transcription in HIV-1. We have previously reported that primer tRNA3Lys exists on the HIV-1 genome both in an unextended form and as a tRNA extended by two deoxynucleotides (12). In that work, total viral RNA was used as the source of primer/template in an in vitro reverse transcription reaction, in the presence of a single radioactive nucleotide. tRNA3Lys was shown to be extended one base when [α-32P]dCTP was used, indicating the presence of unextended tRNA3Lys placed on the genome. A three-base-extended tRNA3Lys was detected when [α-32P]dGTP was used, indicating the presence of two-base-extended tRNA3Lys placed on the genome (12). No radioactive nucleotide incorporation into tRNA3Lys was detected when either [α-32P]dATP or [α-32P]dTTP was used alone.

FIG. 1.

Initiation of in vitro reverse transcription primed by wild-type total viral RNA using either [α-32P]dGTP (three-base extension of tRNA3Lys) or [α-32P]dCTP (one-base extension of tRNA3Lys. (A) Diagram showing the first six dNTPs incorporated into tRNA3Lys during the initiation of reverse transcription. (B) 1D PAGE of tRNA3Lys extension products. Shown is the ability of tRNA3Lys to be extended in the presence of a single dNTP in an in vitro RT reaction primed by wild-type total viral RNA. The single dNTP used is either [α-32P]dCTP (lanes a and c) or [α-32P]dGTP (lanes b and d). (C to F) Dependence of synthesis tRNA3Lys extension products on time (C and D) and dNTP substrate concentration (E and F). Products were resolved by 1D PAGE and quantitated by phosphorimaging. (C) Time courses of dGTP incorporation onto tRNA3Lys at 0.16 (◊) and 5.0 (□) μM dGTP, as normalized to maximum incorporation of dGTP at 5 μM dGTP. (D) Time courses of incorporation of dCTP onto tRNA3Lys at 0.16 (◊) and 5.0 (□) μM dCTP, as normalized to maximum incorporation of dCTP at 5.0 μM dCTP. (E) Dependence of dGTP incorporation on dGTP substrate concentration, normalized to maximum dGTP incorporation. Reverse transcription was for 30 min. (F) Dependence of dCTP incorporation on dCTP substrate concentration, normalized to maximum dCTP incorporation. Reverse transcription was for 30 min.

At low deoxyribonucleotide concentrations, the incorporation of dCTP into unextended tRNA3Lys shows a greater dependency on the concentration of dCTP than does the incorporation of dGTP into two-base-extended tRNA3Lys. The one-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (1D PAGE) data in Fig. 1B show the tRNA3Lys extension products resulting from an in vitro reverse transcription reaction using total wild-type BH10 viral RNA as the source of primer/template in the presence of a single radioactive nucleotide, either [α-32P]dCTP or [α-32P]dGTP. The transfection of COS7 cells with HIV-1 proviral DNA, isolation of virions and total viral RNA, use of total viral RNA as the source of primer tRNA3Lys genomic RNA template in an in vitro reverse transcription system, and 1D PAGE analysis of the reaction products were as previously described (11, 12). Equal amounts of genomic RNA were used in the reaction, with the amount of genomic RNA in the total viral RNA sample determined by dot blot hybridization with a genomic RNA probe (18). Total viral RNA was incubated at 37°C in 20 μl of RT buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 60 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol) containing 50 ng of purified HIV RT, 10 U of RNasin, and various radioactive α-32P-labeled deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs). The extension product was ethanol precipitated, resuspended, and analyzed on 6% polyacrylamide–7 M urea–1× Tris-borate-EDTA. The data in Fig. 1B indicate that the unextended and two-base-extended tRNA3Lys are at approximately equal concentrations when reverse transcription is carried out at a deoxyribonucleotide substrate concentration of 0.16 μM; at 5.0 μM, approximately 75% of the placed tRNA3Lys is unextended, while 25% is two-base extended. As shown in Fig. 1C to F, this difference appears to be due to a lower association constant for dCTP than for dGTP. While dGTP substrate concentrations of 0.16 and 5.0 μM do not affect the time course for the dGTP reaction (Fig. 1C), both the rate and extent of dCTP incorporation are significantly lower when the reaction is carried out at 0.16 rather than 5.0 μM (Fig. 1D). Similarly, there is little difference in the extent of incorporation of dGTP when substrate dGTP concentrations of 0.16 and 5.0 μM are used (Fig. 1E), while there is a more than threefold difference in the extents of incorporation between the dCTP incorporated at substrate dCTP concentrations of 0.16 and 5.0 μM. These data indicate that the incorporation of dGTP onto tRNA3Lys appears to have a higher association constant than dCTP incorporation. While this could reflect differences in base position (1 versus 3) in the cDNA extension of primer tRNA3Lys, it is more likely due to differences in dNTPs, since it had been reported that in an in vitro reverse transcription system, the KM for a dCTP/HIV-1 RT reaction (3.3 μM) was 10-fold greater than that than for a dGTP/HIV-1 RT reaction (0.33 μM) (9).

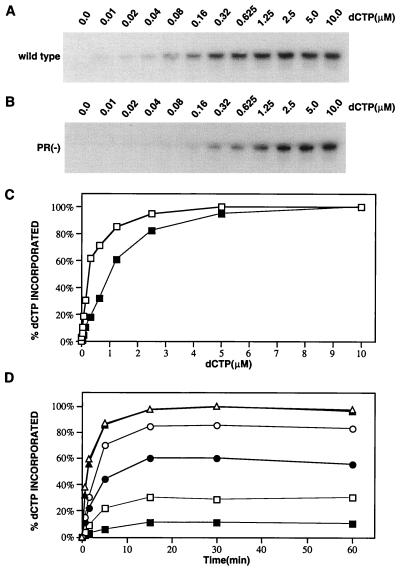

The data shown in Fig. 2 indicate that both the rate and extent of incorporation of the first dCTP into tRNA3Lys are lower when tRNA3Lys is placed onto the viral genome in a protease-negative (PR−) virus rather than in a wild-type virus. Total viral RNA from either type of virus was used as the source of primer/template in the in vitro RT reaction mixture containing different concentrations of [α-32P]dCTP. Equal amounts of unextended tRNA3Lys, as determined by the amount of reaction product at 5.0 μM dCTP, were used in each reaction mixture. Wild-type genomic RNA contains both unextended and two-base-extended tRNA3Lys, while PR− viruses do not contain detectable extended tRNA3Lys (12). We have thus found that in reactions used herein, which contain equal amounts of unextended tRNA3Lys, the PR− primer/template RNA generally contains 10 to 20% less genomic RNA than is found for wild-type primer/template RNA, reflecting the presence of two-base-extended tRNA3Lys on some wild-type primer/template RNAs.

FIG. 2.

Dependence of one-base extension of tRNA3Lys ([α-32P]dCTP] incorporation) on dCTP substrate concentration, using wild-type and PR− primer/template RNAs. Reverse transcription experiments were carried out using as the source of primer/template RNA total viral RNA isolated from either wild-type HIV-1 or PR− HIV-1. (A and B) 1D PAGE-analysis of [α-32P]dCTP incorporation onto tRNA3Lys as a function of dCTP substrate concentration, using total viral RNA isolated from either wild-type virus (A) or PR− (B) as the source of primer/template RNA. (C) Graphic representation of the results presented in panels A (□) and B (■). Both curves are plotted by normalizing to the maximum dCTP incorporation, using wild-type total viral RNA. (D) Time courses of [α-32P]dCTP incorporation onto tRNA3Lys, using wild-type (open symbols) or PR− (closed symbols) total viral RNA as the source of primer/template RNA at dCTP concentrations of 0.16 (squares), 1.25 (circles), and 5 (triangles) μM.

Figure 2 shows the rate and extent of the incorporation of the first-base dCTP onto unextended tRNA3Lys, using as the source of primer/template total viral RNA isolated from either wild-type or PR− virus. At lower dCTP concentrations, the rate and extent of dCTP incorporation into tRNA3Lys are lower with PR− than with wild-type primer/template RNA (Fig. 2A to C). The reactions in Fig. 1C were carried out for 30 min, at which time the reaction was complete, as shown in Fig. 1D by the time courses for these reactions using both primer/tRNA templates at three different dCTP concentrations. The results in Fig. 2 indicate that the primer tRNA3Lys interaction with the genomic RNA in a PR− virion is different from that found for tRNA3Lys placed in a wild-type virion.

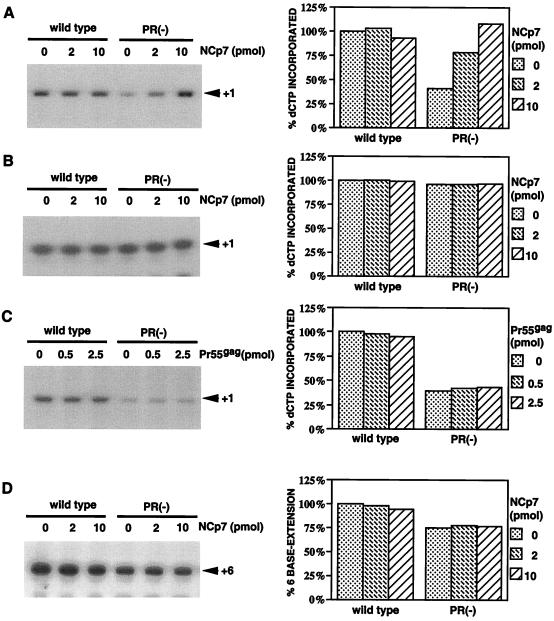

We next investigated the possibility that as a result of Pr55gag proteolytic processing, mature NCp7 may alter the conformation of the primer/template complex, thereby enhancing the amount of reaction between dCTP and primer tRNA3Lys (Fig. 3). The 72-amino-acid HIV-1 NCp7 peptide used in this analysis was prepared by solid-phase chemical synthesis as previously described (4). Plasmid pGST-Gag, which codes for a glutathione-S-transferase (GST)–Gag fusion protein, was a kind gift from Michelle Bouyac. It was used to synthesize GST-Gag in Escherichia coli, and the protein was isolated from the bacterial lysate using glutathione-agarose beads as previously described (2). After exposure of primer/template RNA to the protein, the NCp7 or Pr55gag was removed by proteinase K digestion and phenol-chloroform extraction. Then reverse transcription was initiated through the addition of RT, and the reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min.

FIG. 3.

Effect on the incorporation of [α-32P]dCTP into tRNA3Lys by exposure of wild-type and PR− primer/template RNAs to NCp7 or Pr55gag. (A to C) Left, 1D PAGE detection of one-base, RT-catalyzed DNA extension products of tRNALys3 ([α-32P]dCTP incorporation) as a function of prior exposure of primer/template RNA in vitro to either NCp7 (A and B) or Pr55gag (C) in RT buffer at 37°C for 30 min. Right, graphic representation of these results, normalized to dCTP incorporation, using wild-type primer/template RNA without exposure to NCp7 or Pr55gag. Primer/template RNAs (wild type and PR−) were exposed to NCp7 or Pr55gag and, after deproteinization, used in RT reactions carried out either at 0.16 (A and C) or 5.0 (B) μM dCTP. Equal amounts of unextended tRNA3Lys, as determined by the amount of reaction product at 5.0 μM dCTP, were used in all reaction mixtures. (D) Similar to the experiment in panel A except that to measure extension of unextended and two-base-extended tRNA3Lys, the incorporation of four dNTPs into a six-base DNA extension was measured. Values are normalized to six-base DNA extension obtained using wild-type primer/template RNA without exposure to NCp7.

In the presence of 0.16 μM dCTP (Fig. 3A) and in the absence of prior exposure of the primer/template RNA to nucleocapsid protein, incorporation of dCTP by wild-type primer/template was 2.5 times greater than that for PR− primer/template RNA. Exposure of the wild-type primer/template complex to 2 and 10 pmol of NCp7 had little effect on dCTP incorporation, but similar exposure of the PR− primer/template RNA to NCp7 resulted in a two- and threefold increases in dCTP incorporation, respectively, reaching levels obtained using wild-type primer/template RNA. Removal of the added NCp7 with phenol-chloroform before use of the primer/template RNA in reverse transcription indicated that NCp7 acts by producing a stable alteration in the tRNA3Lys/genomic RNA conformation that cannot be produced by Pr55gag alone (Fig. 3C). This could involve alterations in the conformation of either genomic RNA, tRNA3Lys, or both. Differences in the thermostability of murine and HIV-1 genomic RNA dimers isolated from wild-type and PR− viruses have also been reported (7, 8).

This effect of NCp7 on increasing dCTP incorporation into tRNA3Lys was also examined using RT reaction mixtures containing 5.0 μM dCTP (Fig. 3B). We showed in Fig. 2 that in the presence of 5.0 μM dCTP, dCTP incorporation was maximum and similar using either wild-type or PR− virus. Exposure of either wild-type or PR− primer/template RNA to NCp7 had no further effect on dCTP incorporation at 5.0 μM dCTP, unlike the effect seen with 0.16 μM dCTP (Fig. 3A). This indicates that the amount of tRNA3Lys placed on either genomic RNA is maximal under these conditions (5.0 μM dCTP) and that the exposure of these templates to NCp7 does not facilitate further in vitro annealing of primer tRNA3Lys.

This was further examined by directly measuring total placement of extendable tRNA3Lys in the absence and presence of exposure of primer/template RNA to NCp7 (Fig. 3D). The RT reaction mixture contained non-rate-limiting amounts of 200 μM dCTP and 200 μM dTTP, plus 10 μCi of [α-32P]dGTP (0.16 μM). The replacement of dATP with 50 μM ddATP terminated the DNA extension product of unextended and two-base-extended tRNA3Lys at six bases (Fig. 1A). The reactions shown in Fig. 3D used equal amount of unextended tRNA3Lys, which accounts for the fact that total synthesis using wild-type primer/template RNA was about 25% higher than that using PR− primer/template RNA, since only the former had two-base-extended tRNA3Lys as well as unextended tRNA3Lys. It can be seen that there was little change in the total placement of tRNA3Lys upon addition of NCp7 to either primer/template RNA type.

According to the model presented, Pr55gag can place tRNA3Lys onto the viral genome, but mature NCp7 may be required to configure this interaction for optimum priming. If this is so, then the prior exposure of a PR− primer/template RNA to Pr55gag should not increase initiation of reverse transcription at low dCTP concentrations, as is found when NCp7 is added. The data in Fig. 3C indicate that this is true. Various amounts of Pr55gag protein (0.5 and 2.5 pmol) were preincubated with primer/template complex in RT buffer at 37°C for 30 min. The Pr55gag protein was removed by proteinase K digestion and phenol-chloroform extraction, as described above, before initiation of the one-base RT extension reaction. The data in Fig. 3C show that Pr55gag does not increase initiation from tRNA3Lys placed on the genome in either wild-type or PR− virions. Since tRNA3Lys placement has been shown to be facilitated both in vitro (6) and in vivo (3) by Pr55gag, this also indicates that the NCp7-facilitated increase in dCTP incorporation into tRNA3Lys using the PR− primer/template at a low dCTP concentration is not the result of increased in vitro placement of tRNA3Lys onto the template.

The differences observed for wild-type and PR− primer/templates in the rate and extent of initiation of reverse transcription may reflect differences in affinity of dCTP for a conformationally altered RT or primer tRNA3Lys. Current evidence indicates that during the initiation of reverse transcription, RT binds first to the primer tRNA/template complex and then to the dNTP (10, 19). It is therefore possible that differences in the conformations between the wild-type and PR− primer tRNA/template complexes can induce correspondingly different conformations of the RT binding to these complexes, thereby affecting the affinity of the enzyme for dCTP. This phenomenon has been reported for artificial primer/templates. For example, it was found that the reaction between dCTP and HIV-1 RT using poly(rI)-oligo(dC) had a KM of 12.2 μM, while the same reaction using a heteropolymeric primer/template had a KM of 3.3 μM (9).

REFERENCES

- 1.Berkowitz R, Fisher J, Goff S P. RNA packaging. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;214:177–218. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80145-7_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouyac M, Courcoul M, Bertoia G, Baudat Y, Gabuzda D, Blanc D, Chazal N, Boulanger P, Sire J, Vigne R, Spire B. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif protein binds to the Pr55gag precursor. J Virol. 1997;71:9358–9365. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9358-9365.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cen S, Huang Y, Khorchid A, Darlix J L, Wainberg M A, Kleiman L. The role of Pr55gag in the annealing of tRNA3Lys to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomic RNA. J Virol. 1999;73:4485–4488. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4485-4488.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Rocquigny H, Ficheux D, Fournie-Zaluski M C, Darlix J L, Roques B. First large scale chemical synthesis of the 72 amino acid HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein NCp7 in an active form. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;180:1010–1018. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Rocquigny H, Gabus C, Vincent A, Fournie-Zaluski M-C, Roques B, Darlix J-L. Viral RNA annealing activities of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein require only peptide domains outside the zinc fingers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6472–6476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng Y X, Campbell S, Harvin D, Ehresmann B, Ehresmann C, Rein A. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag polyprotein has nucleic acid chaperone activity: possible role in dimerization of genomic RNA and placement of tRNA on the primer binding site. J Virol. 1999;73:4251–4256. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4251-4256.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu W, Gorelick R J, Rein A. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 dimeric RNA from wild-type and protease-defective virions. J Virol. 1994;68:5013–5018. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5013-5018.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu W, Rein A. Maturation of dimeric viral RNA of Moloney murine leukemia virus. J Virol. 1993;67:5443–5449. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5443-5449.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gu Z, Fletcher R S, Arts E J, Wainberg M A, Parniak M A. The K65R mutant reverse transcriptase of HIV-1 cross-resistant to 2′,3′- dideoxycytidine, 2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine, and 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine shows reduced sensitivity to specific dideoxynucleoside triphosphate inhibitors in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28118–28122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsieh J, Zinnen S, Modrich P. Kinetic mechanism of the DNA-dependent DNA polymerase activity of human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24607–24613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang Y, Khorchid A, Gabor J, Wang J, Li X, Darlix J L, Wainberg M A, Kleiman L. The role of nucleocapsid and U5 stem/A-rich loop sequences in tRNA3Lys genomic placement and initiation of reverse transcription in human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:3907–3915. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3907-3915.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Y, Wang J, Shalom A, Li Z, Khorchid A, Wainberg M A, Kleiman L. Primer tRNA3Lys on the viral genome exists in unextended and two base-extended forms within mature human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1997;71:726–728. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.726-728.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isel C, Ehresmann C, Keith G, Ehresmann B, Marquet R. Initiation of reverse transcription of HIV-1: secondary structure of the HIV-1 RNA/tRNALys3 (template/primer) complex. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:236–250. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isel C, Marquet R, Keith G, Ehresmann C, Ehresmann B. Modified nucleotides of tRNALys3 modulate primer/template loop-loop interaction in the initiation complex of HIV-1 reverse transcription. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:25269–25272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang M, Mak J, Ladha A, Cohen E, Klein M, Rovinski B, Kleiman L. Identification of tRNAs incorporated into wild-type and mutant human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1993;67:3246–3253. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3246-3253.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan R, Giedroc D P. Recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid (NCp7) protein unwinds tRNA. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:6689–6695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mak J, Jiang M, Wainberg M A, Hammarskjold M-L, Rekosh D, Kleiman L. Role of Pr160gag-pol in mediating the selective incorporation of tRNALys into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J Virol. 1994;68:2065–2072. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2065-2072.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mak J, Khorchid A, Cao Q, Huang Y, Lowy I, Parniak M A, Prasad V R, Wainberg M A, Kleiman L. Effects of mutations in Pr160gag-pol upon tRNALys3 and Pr160gag-pol incorporation into HIV-1. J Mol Biol. 1997;265:419–431. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel P H, Jacobo-Molina A, Ding J, Tantillo C, Clark A D, Raag R, Nanni R G, Hughes S H, Arnold E. Insights into DNA polymerization mechanisms from structure and function analysis of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Biochemistry. 1995;34:5351–5363. doi: 10.1021/bi00016a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swanstrom R, Wills J W. Synthesis, assembly, and processing of viral proteins. In: Coffin J M, Hughes S H, Varmus H E, editors. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 263–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]