Abstract

Objective

The primary objective of this study was to assess, summarize, and compare the current integrated clinical learning opportunities offered for students who matriculated in US doctor of chiropractic programs (DCPs).

Methods

Two authors independently searched all accredited DCP handbooks and websites for clinical training opportunities within integrated settings. The 2 data sets were compared with any discrepancies resolved through discussion. We extracted data for preceptorships, clerkships, and/or rotations within the Department of Defense, Federally Qualified Health Centers, multi-/inter-/transdisciplinary clinics, private/public hospitals, and the Veterans Health Administration. Following data extraction, officials from each DCP were contacted with a request to verify the collected data.

Results

Of the 17 DCPs reviewed, all but 3 offered at least 1 integrated clinical experience, while 41 integrated clinical opportunities were the most offered by a single DCP. There was an average of 9.8 (median 4.0) opportunities per school and an average of 2.5 (median 2.0) clinical setting types. Over half (56%) of all integrated clinical opportunities were within the Veterans Health Administration, followed by multidisciplinary clinic sites (25%).

Conclusion

This work presents preliminary descriptive information of the integrated clinical training opportunities available through DCPs.

Keywords: Chiropractic, Clinical Clerkship, Hospitals, Integrative Medicine, Education

INTRODUCTION

The National Institutes of Health defines integrative health as aiming “for well-coordinated care among different providers and institutions by bringing conventional and complementary approaches together to care for the whole person.”1 In the United States, integration of chiropractic services with primary and specialty care is being actualized in part by a growing trend toward doctors of chiropractic pursuing careers within health care systems. The 2020 National Board of Chiropractic Examiners practice analysis survey demonstrated that more than 18% of respondents practiced within an integrated setting,2 double the percentage reported in 2015.3 In particular, the growth of chiropractic services has been rapid within the Department of Defense and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), increasing the chiropractic services at rates of 10% and 17% respectively.4 In the private sector, chiropractic services are utilized within hospitals and other integrated clinical settings, though the rate of growth is currently unknown.5–7 Chiropractic services have been described in private medical groups,8 university hospital systems,9–11 and Federally Qualified Health Centers.12–14 Another avenue of chiropractor integration has been the implementation of the Primary Spine Practitioner model within at least 7 hospital, payer, or community systems within the United States.15

In most jurisdictions, it is not mandatory for chiropractors to complete postgraduate training as part of their practice requirements. For licensure eligibility, doctor of chiropractic program (DCP) graduates have similar requirements to optometry program graduates16,17 in that they are required to complete clinical didactics, attain a minimum threshold of clinical experience (often referred to as rotations or preceptorship), pass national board examinations, and satisfy local state or territory regulations.18 This differs significantly from the medical profession, which requires 3–7 years of postgraduate training, depending on the chosen specialty or area of practice. The first year of medical residency, referred to as postgraduate year 1 or internship year, is often spent introducing residents to various departments, building the physician's knowledge of specialties, and aiding them in selecting a career path.19

Furthermore, exposure to multiple disciplines expands knowledge of different management approaches, fosters the growth of the entire health care system, improves health outcomes, and provides interprofessional education, which is a necessary step in preparing trainees to be collaborative practice ready.20 Medical residents rate interaction with peers as their “highest source of learning.”21 Starting in 2014, the VHA has offered a 1-year Chiropractic Integrated Clinical Practice residency to recent graduates. There are currently 10 VHA facilities in the United States that have received or are in the process of applying for accreditation of a chiropractic residency program, and they offer a unique opportunity for graduates to participate in hospital-based clinical care, interprofessional rotations, and scholarship.22,23

Collaborative practice and interprofessional team skill sets, including a foundational understanding of medical specialties,19,24 are paramount to facilitating the expansion of chiropractic services within integrated medical settings.6,25 When surveyed, a majority of chiropractors practicing in integrated settings (60.0%) report comanagement of patients with other health care providers.7 Chiropractic students (69.2%) across multiple DCPs recognize clinical training in integrated settings as valuable for the profession26 and welcome the opportunity for participation.27 In a recent study of VHA chiropractors, 31% of respondents reported prior hospital-based integrated experience as part of their student clinical training.28

The Council on Chiropractic Education accreditation standards stipulates (Section H, meta-competency 8 on interprofessional education) that DCP-assessed outcomes include providing opportunities for students to “use appropriate team building and collaborative strategies with other members of the healthcare team to support a team approach to patient centered care” as a requirement for graduation.18 The Council on Chiropractic Education outlines that interprofessional education may be demonstrated in didactic, clinical, or simulated learning environments but does not explicitly require training in settings with other health care professionals.18 A preliminary descriptive study reported early implementation of chiropractic student trainees within 4 VHA integrated chiropractic clinics,29 but to our knowledge, no studies have investigated the availability of integrated clinical training opportunities across US DCPs. The purpose of this study was to assess, summarize, and compare the current integrated clinical learning opportunities available for students within US DCPs.

METHODS

The VA Puget Sound Human Research Protection Office reviewed this project and determined it did not meet the definition of research requiring institutional review board approval. Similar to other studies, we reviewed public-facing DCP documents and websites.30–32 Doctor of chiropractic institutions were identified from the Association of Chiropractic Colleges (ACC) website.33 Similar to studies by Gliedt et al31 and Cupler et al,32 we included the Sherman College of Chiropractic and also included the newly accredited Universidad Central del Caribe, who are not ACC members but whose students are eligible for US board pre-licensure examinations (Table 1).

Table 1.

- Included US Doctor of Chiropractic Programs

|

Institution |

Location |

| Cleveland University–Kansas City | Overland Park, KS |

| D'Youville College | Buffalo, NY |

| Keiser University | West Palm Beach, FL |

| Life Chiropractic College West | Hayward, CA |

| Life University | Marietta, GA |

| Logan University | Chesterfield, MO |

| National University of Health Sciences | Seminole, FL |

| Lombard, IL | |

| Northeast College of Health Sciences | Seneca Falls, NY |

| Northwestern Health Sciences University | Bloomington, MN |

| Palmer College of Chiropractic | Davenport, IA |

| Port Orange, FL | |

| San Jose, CA | |

| Parker University | Dallas, TX |

| Sherman College of Chiropractic | Spartanburg, SC |

| Southern California University of Health Sciences | Whittier, CA |

| Texas Chiropractic College | Pasadena, TX |

| Universidad Central del Caribe | Bayamon, PR |

| University of Bridgeport School of Chiropractic | Bridgeport, CT |

| University of Western States | Portland, OR |

We searched public-facing DCP websites and electronic program handbooks from July 2021 through September 2021. Each DCP website was combed for the most recent curriculum or handbook, which was then searched digitally using the “find” function for key terms (Table 2).31,32 In addition, the DCP websites were manually searched for available integrated clinical opportunities identified via the same search terms. Data were extracted into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA) to track the following: information source (handbook or website), presence of integrated clinical opportunity (1 = yes or 0 = no), type of integrated clinical opportunities available (1 = yes or 0 = no), number of opportunities (count), number of each opportunity (count), total number of opportunities (count), and length of training (free type or NA = not available). Integrative clinical opportunities were defined as any experiences where the DCP trainee was involved in care delivery within an integrated health care system and in a separate physical space from the DCP training clinics. For example, if a medical doctor supervises or provides care at an on-campus DCP training clinic, that was excluded. In addition, if a DCP has an affiliation with a single health care system but that system allows DCP students at different locations, it was tallied as only 1 opportunity. However, if a DCP has an affiliation with 2 separate systems within the same organization, these were tallied as 2 integrated clinical opportunities (e.g., multiple VHA affiliations with 1 DCP). Any categories that could not be located via a search of the website or curriculum were reported as “0” for “not available.” Multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary clinics were used synonymously.

Table 2.

- Search Terminology

| “integrat,” “clinic,” “rotation,” “clerkship,” “externship,” “preceptorship,” “hospital,” “federal,” “FQHC,” “VA,” “vet,” “defense,” “DOD,” “multidisciplinary,” “interdisciplinary,” and “transdisciplinary” |

Two authors (KM and OA) independently performed the data extraction of each DCP. The 2 data sets were then compared and any discrepancies resolved through discussion. Following data extraction, a clinical dean, a director of clinical education, or an apparent equivalent representative at each DCP was e-mailed with a request to verify the accuracy of our collected information. If no response was received from the DCP contact within 1 week, a follow-up e-mail was sent 1 week later. If still no response was received, we proceeded with the publicly available information but denoted lack of confirmation with an asterisk in our data tables. All analyses were descriptive and proportions reported for categorical variables and mean and median for continuous variables.

RESULTS

Seventeen publicly facing DCP curriculums and websites were searched, with the majority of information sourced from DCP websites. The types and number of integrated clinical training opportunities can be found in Tables 3 and 4. A total of 166 opportunities exist for US DCP students to gain experience in integrated clinical settings. A majority, 88.2% (15/17), of DCPs reported offering training in at least 1 integrated setting, with a mean of 9.8 total integrated opportunities (median 4.0) and a mean of 2.5 (median 2.0) different types of settings. The maximum number of integrated training experiences available through a single DCP was 41.

Table 3.

- Number of Integrated Clinical Opportunities Available

|

Institution |

Location Found |

ICO Available |

No. of Types |

DoD |

FQHC |

M/I/T |

P/P |

VHA |

| Cleveland University–Kansas City a | Website | Y | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| D'Youville College a | Website | Y | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Keiser University a | Website | Y | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Life Chiropractic College West a | Handbook and website | N | 0 | No integrated clinical opportunities demonstrated in public-facing documents | ||||

| Life University a | Handbook and website | Y | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Logan University | Website | Y | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| National University of Health Sciencesc | Website | Y | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Northeast College of Health Sciences a | Website | Y | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Northwestern Health Sciences University a | Website | Y | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Palmer College of Chiropracticc | Website | Y | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Parker University | Handbook and website | Y | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Sherman College of Chiropractic a | Handbook and website | N | 0 | No integrated clinical opportunities demonstrated in public-facing documents | ||||

| Southern California University of Health Sciences ab | Handbook and website | Y | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Texas Chiropractic College | Handbook and website | Y | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| University of Bridgeport School of Chiropractic | Website | Y | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Universidad Central del Caribe | Handbook and website | Y | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| University of Western States | Website | Y | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 15 | 5 | 7 | 12 | 6 | 10 | ||

Data were not confirmed with doctor of chiropractic program.

Doctor of chiropractic program notified of updated information available, re-searched March 2022.

Includes all campuses

ICO indicates integrated clinical opportunity; DoD, Department of Defense; FQHC, Federally Qualified Health Center; M/I/T, multi-/inter-/transdisciplinary; P/P, public/private hospital; VHA, Veterans Health Administration; Y, yes, N, no.

Table 4.

- Number of Opportunities Available per Integrated Clinical Opportunity Type

|

Institution |

Total No. of Opportunities |

DoD |

FQHC |

M/I/T |

P/P |

VHA |

| Cleveland University–Kansas City a | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| D'Youville College a | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Keiser University a | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Life Chiropractic College West a | 0 | No integrated clinical opportunities demonstrated in public-facing documents | ||||

| Life University a | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Logan University | 20 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 10 |

| National University of Health Sciencesb | 10 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| Northeast College of Health Sciences | 16 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 7 |

| Northwestern Health Sciences University a | 4 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Palmer College of Chiropracticb | 41 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 34 |

| Parker University | 28 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 17 |

| Sherman College of Chiropractic a | 0 | No integrated clinical opportunities demonstrated in public-facing documents | ||||

| Southern California University of Health Sciences a | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Texas Chiropractic College | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| University of Bridgeport School of Chiropractic a | 6 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Universidad Central del Caribe | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| University of Western States | 16 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 10 |

| Total | 9 | 13 | 42 | 9 | 93 | 166 |

Data were not confirmed with the doctor of chiropractic program.

Includes all campuses

DoD indicates Department of Defense; FQHC, Federally Qualified Health Center; M/I/T, multi-/inter-/transdisciplinary; P/P, public/private hospital; VHA, Veterans Health Administration.

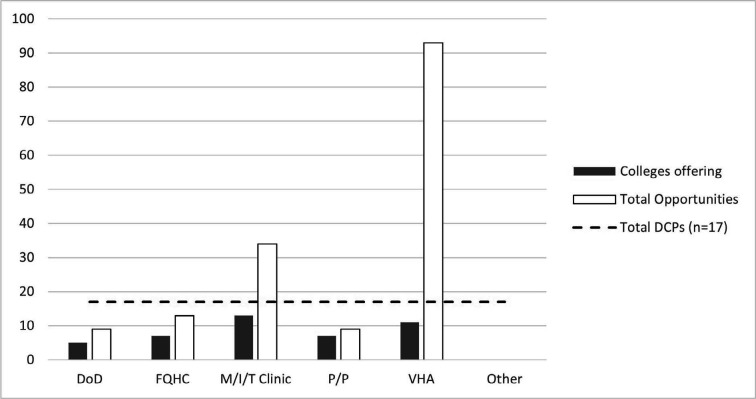

VHA affiliations were the most prevalent integrated clinical experience, accounting for 56.0% (93/166) of total integrated opportunities in affiliation with 64.7% (11/17) of DCPs (Fig. 1). Multi-/inter-/transdisciplinary clinics were the second most common integrated opportunity at 25.0% (42/166) while being offered at the most DCPs (13/17 [76.5%]). In addition, DCPs listed integrated opportunities offered through partnerships with Federally Qualified Health Centers 41.2% (7/17), private/public hospitals 41.2% (7/17), and Department of Defense sites 29.4% (5/17) (Fig. 1, Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 1.

- Number and settings of integrated clinic opportunities. DC indicates doctor of chiropractic; DCP, doctor of chiropractic program; DoD, Department of Defense; FQHC, Federally Qualified Health Center; M/I/T, multi-/inter-/transdisciplinary; PP, private/public hospital; VHA, Veterans Health Administration.

Descriptions of the duration of integrated clinical training were limited in availability and heterogeneous. Several DCPs reported program length by academic calendar (trimesters, quarters, and so on), by traditional calendar (weeks or months), or not at all. When contacted, 8 of the 17 DCPs reported additional opportunities not listed in public documents at the time of data extraction.

DISCUSSION

This work demonstrates that at least 1 integrated clinical opportunity is available to chiropractic students through a majority of US DCPs. However, 6 of the 17 DCPs accounted for 78.9% (131/166) of the integrated clinical opportunities. The public-facing documents revealed that 3 DCPs did not offer clinical training opportunities on-site in integrated medical facilities and that 9 DCPs offered fewer than 10 opportunities in total. VHA is the largest health care training institution in the United States,34 and, consistently, VHA comprised nearly two-thirds of the integrated clinical opportunities identified for DCP student trainees. There are several factors that may contribute to the strong representation of VHA chiropractic integrated clinical opportunities, including a mission dedicated to education and training health care personnel, the presence of national professional leadership, and inherent infrastructure allowing for the development of academic affiliations as a pipeline to accessing trainees.4 Continued expansion of DCP affiliations within other integrated settings may improve DCP clinical experiences and help early career chiropractors excel in diverse environments with a spectrum of patients and providers.

It is apparent that DCP students and the chiropractic profession believe integration to be important.25,27 The steady growth of chiropractors providing care at traditional medical centers4,15,22 heightens the importance of integrated clinical training in these settings while in the clinical phase of a DCP. Further, integrated clinical training opportunities could serve as an important facilitator to developing interprofessional skills and building relationships for future expansion of chiropractic integration efforts in integrated clinical settings and scholarly research activities. While the VHA chiropractic residency offers an opportunity for integrated training after graduation, very few spots are available at this time, and this lends toward a significant gap in the availability of advanced hospital-based training opportunities for practicing chiropractors.

The positive impact that chiropractic services have on the health care system has been well documented. Several studies have shown that implementation of chiropractic within hospital settings improved disability outcomes in patients with chronic spinal pain14,35 and reduced the escalation of costly spine services, including opioids,36–38 diagnostic imaging,5,39 injections,39 and surgery.40 Cost comparisons consistently demonstrate that management of spine care conditions inclusive of chiropractic has resulted in lower associated costs for patient care.41–43 The colocation of care between chiropractic and physician teams is reported to be important to patients and is likely to facilitate communication, collaboration, and trust between providers.44,45

A majority of chiropractic students are multimodal learners with a significant preference for kinesthetic learning.46 As chiropractic is a very hands-on profession and because high-quality experiences may enhance clinical decision making and overall quality of patient care,47 the authors speculate that opportunities to learn and practice chiropractic within integrated clinical spaces may facilitate the retention and translation of these behaviors into clinical practice. A reported two-thirds of chiropractic students are neutral to or in favor of a mandatory postgraduate residency program prior to professional licensure.48 Participation in an integrated clinical training program may positively influence the students' recognition of the benefit of and encourage them to apply for residency programs. It is unclear how the presence of integrated clinical training opportunities may affect decision making for potential chiropractic applicants and/or school marketing strategies.

There are many avenues for future research efforts, which may include studying (1) the impact of training in an integrated clinical setting on DCP students' education and the influence such experiences have on career paths, (2) the competitiveness and utilization of integrated clinical training opportunities by chiropractic students, (3) the perceptions and attitudes toward chiropractic training in integrated clinical settings from other health care disciplines and trainees, (4) the quality of learning (number and complexity of cases seen, level of student involvement in patient care, use of integrated electronic health records, and ability to observe and interact with physicians and allied health care providers and health care trainees of other professions) across different environments, and (5) a repeat assessment of integrated clinical training opportunities at DCPs at a later time to evaluate growth and sustainment of opportunities.

Limitations

As other similarly approached reviews have acknowledged, there are several limitations to searching public-facing documents.30–32 The DCPs may not have had all current integrated clinical training opportunities listed. Several DCPs' websites were vague in their descriptions of the integrated clinical opportunities, or the descriptions were not found within a clinical training section of the website, which made collecting the opportunities challenging. While attempts were made to contact each DCP's officials for confirmation, responses were varied. Furthermore, the majority of DCPs who responded to the confirmation e-mails reported a substantially higher number of integrated clinical training opportunities available. For example, during data extraction, 1 DCP's public-facing documents revealed no integrated clinical training opportunities, but the DCP reported 16 when contacted for confirmation. These differences may be due to not having an up-to-date list on their websites or the addition of new affiliations formed between the time of data extraction and DCP administrator contact. These numbers can change within an academic year as new affiliations are created or dissolved.

Next, it was beyond the scope of this review to account for student utilization of the opportunities available in a given cycle (trimester, quarter, and so on) or how many students can utilize an integrated clinical training opportunity at 1 time. This information could not be ascertained from the public-facing documents. Finally, this work was primarily quantitative in nature and did not evaluate the content or quality of each clinical opportunity.

CONCLUSION

A spectrum of integrated clinical training opportunities is offered by US DCPs. As of the fall of 2021, 166 integrated clinical training opportunities existed across 17 US DCPs, with 6 DCPs accounting for 78.9% (n = 131) of the opportunities, and most were offered at academically affiliated VHA facilities. This work presents the current state of integrated clinical training opportunities available at US DCPs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The content of this article reflects the view of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government. The authors received indirect support from their institutions in the form of computers, workspace, and time to prepare the article.

Footnotes

FUNDING AND CONFLICTS OF INTEREST The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: what's in a name? Apr, 2021. Accessed February 14, 2022. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name.

- 2.Himelfarb I, Hyland J.Practice analysis of chiropractic 2020: a project report, survey analysis, and summary of chiropractic practice in the United States. National Board of Chiropractic Examiners. 2020. Accessed July 18, 2021. https://www.nbce.org/practice-analysis-of-chiropractic-2020.

- 3.Christensen M, Hyland J, Goertz C, Kollasch M.Practice analysis of chiropractic 2015: a project report, survey analysis, and summary of chiropractic practice in the United States. National Board of Chiropractic Examiners. 2015. Accessed July 18, 2021. https://www.nbce.org/nbce-news/analysis-2015/

- 4. Green B, Dunn A. An essential guide to chiropractic in the United States Military Health System and Veterans Health Administration J Chiropr Humanit 2022. 28 35–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Whedon J, Toler A, Bezdijan S, Goehl J. Implementation of the primary spine care model in a multi-clinician primary care setting: an observational cohort study J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2020. 43 (7) 667–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lisi A, Salsbury S, Twist E, Goertz C. Chiropractic integration into private sector medical facilities: a multisite qualitative case study J Altern Complement Med 2018. 24 (8) 792–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Salsbury S, Goertz C, Twist E, Lisi A. Integration of doctors of chiropractic into private sector health care facilities in the United States: a descriptive survey J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2018. 41 (2) 149–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mattox R, Trager R, Kettner N. Effort thrombosis in 2 athletes suspected of musculoskeletal injury J Chiropr Med 2019. 18 (3) 213–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bernstein C, Wayne P, Rist P, et al. Integrating chiropractic care into the treatment of migraine headaches in a tertiary care hospital: a case series. Glob Adv Health Med. 2019;8:2165956119835778. doi: 10.1177/2164956119835778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bezdijan S, Whedon J, Goehl J, Kazal LJ. Experiences and attitudes about chiropractic care and prescription drug therapy among patients with back pain: a cross-sectional survey J Chiropr Med 2021. 20 (1) 1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Branson R. Hospital-based chiropractic integration within a large private hospital system in Minnesota: a 10-year example J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2009. 32 (9) 740–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mann D, Mattox R. Chiropractic management of a patient with chronic pain in a federally qualified health center: a case report J Chiropr Med 2018. 17 (2) 117–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lewis K, Battaglia P. Differentiating bilateral symptomatic hand osteoarthritis from rheumatoid arthritis using sonography when clinical and radiographic features are nonspecific: a case report J Chiropr Med 2019. 18 (1) 56–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Prater C, Tepe M, Battaglia P. Integrating a multidisciplinary pain team and chiropractic care in a community health center: an observational study of managing chronic spinal pain. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720953680. doi: 10.1177/2150132720953680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murphy D, Justice B, Bise C, Timko M, Stevans J, Schneider M. The primary spine practitioner as a new role in healthcare systems in North America. Chiropr Man Ther. 2022;30((1)):6. doi: 10.1186/s12998-022-00414-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Erwin W, Korpela A, Jones RC. Chiropractors as primary spine care providers: precedents and essential measures J Can Chiropr Assoc 2013. 57 (4) 285–291 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry. Optometry: a career guide. Aug, 2020. Accessed May 24, 2022. https://optometriceducation.org/pdfs/careerguide-august-2020.pdf.

- 18.Council on Chiropractic Education. CCE accreditation standards: principles, process, & requirements for accreditation. Jul, 2020. Accessed July 18, 2021. https://www.cce-usa.org/uploads/1/0/6/5/106500339/2020_cce__accreditation_standards__current_.pdf.

- 19. Austin-McClellan L, Lisi A. An overview of the medical specialties most relevant to chiropractic practice and education J Chiropr Educ 2021. 35 (1) 72–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gilbert J, Yan J, Hoffman S. A. WHO report: framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice J Allied Health 2010. 39 (suppl 1) 196–197 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baldwin DJ, Daugherty S. How residents say they learn: a national, multi-specialty survey of first- and second-year residents J Grad Med Educ 2016. 8 (4) 631–639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lisi A.Department of Veterans Affairs chiropractic residency programs: overview and update. Nov, 2021. Accessed July 18, 2021. https://www.rehab.va.gov/PROSTHETICS/chiro/VAChiroResidencyProgramUpdate.pdf.

- 23. US Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation and prosthetic services—VA chiropractic education and training August 11, 2022. Accessed October 27, 2022. https://www.prosthetics.va.gov/chiro/Residency_Programs.asp

- 24. Schneider M, Murphy D, Hartvigsen J. Spine care as a framework for the chiropractic identity J Chiropr Humanit 2016. 23 (1) 14–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lisi A, Salsbury S, Hawk C, et al. Chiropractic integrated care pathway for low back pain in veterans: results of a Delphi consensus process J Manip Physiol Ther 2018. 41 (2) 137–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gliedt J, Hawk C, Anderson M, et al. Chiropractic identity, role and future: a survey of North American chiropractic students. Chiropr Man Ther. 2015;23((1)):4. doi: 10.1186/s12998-014-0048-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Knieper MJ, Bhatti JL, Dc EJT. Perceptions of chiropractic students regarding interprofessional health care teams J Chiropr Educ 2022. Mar 1; 36 (1) 30–36 10.7899/JCE-20-9. PMID: 34320646; PMCID: PMC8895838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Halloran S, Coleman B, Kawecki T, Long C, Goertz C, Lisi A. Characteristics and practice patterns of U.S. Veterans Health Administration doctors of chiropractic: a cross-sectional survey J Manip Physiol Ther 2021. 44 (7) 535–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dunn A. A survey of chiropractic academic affiliations within the department of veterans affairs health care system J Chiropr Educ 2007. 21 (2) 138–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Funk M, Frisina-Deyo A, Mirtz T, Perle S. The prevalence of the term subluxation in chiropractic degree program curricula throughout the world. Chiropr Man Ther. 2018;26:24. doi: 10.1186/s12998-018-0191-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gliedt J, Battaglia P, Holmes B. The prevalence of psychosocial related terminology in chiropractic program courses, chiropractic accreditation standards, and chiropractic examining board testing content in the United States. Chiropr Man Ther. 2020;28((1)):43. doi: 10.1186/s12998-020-00332-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cupler ZA, Price M, Daniels CJ. The prevalence of suicide prevention training and suicide-related terminology in United States chiropractic training and licensing requirements J Chiropr Educ 2022. Oct 1; 36 (2) 93–102 10.7899/JCE-21-14. PMID: 35061035; PMCID: PMC9536234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Association of Chiropractic Colleges. Study chiropractic. 2022. Accessed February 14. https://www.chirocolleges.org/find-a-school.

- 34. Veterans Health Administration About VHA April 18, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2022. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutVHA.asp

- 35. Dougherty P, Karuza J, Dun A, Savion D, Katz P. Spinal manipulative therapy for chronic lower back pain in older veterans: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2014. 5 (4) 154–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Acharya M, Chopra D, Smith AM, Fritz JM, Martin BC. Associations Between Early Chiropractic Care and Physical Therapy on Subsequent Opioid Use Among Persons With Low Back Pain in Arkansas J Chiropr Med. 2022 Jun 21 (2) 67–76 10.1016/j.jcm.2022.02.007. Epub 2022 May 21. PMID: 35774633; PMCID: PMC9237579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Corcoran K, Bastian L, Gunderson C, et al. Association between chiropractic use and opioid receipt among patients with spinal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis Pain Med 2020. 21 (2) e139–e145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Whedon J, Toler A, Goehl J, Kazal L. Association between utilization of chiropractic services for treatment of low-back pain and use of prescription opioids J Altern Complement Med 2018. 24 (6) 552–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bezdijan S, Whedon J, Russell R, Goehl J, Kazal L. Efficiency of primary spine care as compared to conventional primary care: a retrospective observational study at an academic medical center. Chiropr Man Ther. 2022;30((1)):1. doi: 10.1186/s12998-022-00411-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Keeney B, Fulton-Kehoe D, Turner J, et al. Early predictors of lumbar spine surgery after occupational back injury: results from a prospective study of workers in Washington State Spine Phila Pa 1976 2013. 38 (11) 953–964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Whedon J, Bezdijan S, Dennis P, Russell R. Cost comparison of two approaches to chiropractic care for patients with acute and sub-acute low back pain care episodes: a cohort study. Chiropr Man Ther. 2020;28((1)):68. doi: 10.1186/s12998-020-00356-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hurwitz E, Li D, Guillen J, et al. Variations in patterns of utilization and charges for the care of low back pain in North Carolina, 2000 to 2009: a statewide claims' data analysis J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2016. 39 (4) 252–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hurwitz E, Dongmei L, Guillen J, et al. Variations in patterns of utilization and charges for the care of neck pain in North Carolina, 2000 to 2009: A statewide claims' data analysis J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2016. 39 (4) 240–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bonciani M, Schäfer W, Barsanti S, et al. The benefits of co-location in primary care practices: the perspectives of general practitioners and patients in 34 countries BMC Health Serv Res 2018. 18 (1) 1–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mallard F, Lemeunier N, Mior S, Pecourneau V, Cote P. Characteristics, expectations, experiences of care, and satisfaction of patients receiving chiropractic care in a French university hospital in Toulouse (France) over one year: a case study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23:229. doi: 10.1186/s12891-022-05147-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Whillier S, Lystad R, Abi-Arrage D, et al. The learning style preferences of chiropractic students: a cross-sectional study J Chiropr Educ 2014. 28 (1) 21–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dane D, Dane A, Crowther E. A survey of perceptions and behaviors of chiropractic interns pertaining to evidence-based principles in clinical decision making J Chiropr Educ 2016. 30 (2) 131–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gliedt J, Briggs S, Williams J, Smith D, Blampied J. Background, expectations and beliefs of a chiropractic student population: a cross-sectional survey J Chiropr Educ 2012. 26 (2) 146–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]