INTRODUCTION

Parasites are unicellular or multicellular organisms, classified as protozoa, helminths, or arthropods. Colonization of human gut by certain protozoa (Table 1) or helminths (Table 2) can result in gastroenteritis. The frequency of parasitic gastroenteritis displays wide variation throughout the world, where the incidence and prevalence of disease parallel the frequency of parasites in endemic versus nonendemic geographies. Specific exposures, such as drinking river water and eating raw meats, predispose to parasitic gastroenteritis regardless of location in endemic landscapes. Moreover, patient populations, for example, organ transplant recipients, are at high risk of developing intense parasitic infections due to immunosuppression.

Table 1.

Overview of protozoal infections causing gastroenteritis

| Parasite | Geographic Region | At-risk Populations | Symptoms | Diagnosis | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giardia | Worldwide, usually due to contaminated surface water | Affects both immunocompetent and immunocompromised | Bloating and diarrhea | Stool examination for trophozoites and cysts | Metronidazole, 500 mg, twice daily for 5–7 d |

| Cryptosporidiosis | Worldwide | Affects both immunocompetent and immunocompromised but prolonged and more severe infection in immunosuppressed individuals (AIDS or organ transplant recipients) | Profuse diarrhea | ELISA for Cryptosporidia antigen | Supportive care for immunocompetent patients Can consider nitazoxanide or trimethroprim-sulfamethoxazole if immunocompromised |

| Cystoisospora | Tropical and subtropical climates | Immigrants and immunosuppressed patients (AIDS) | Nonbloody diarrhea | Direct visualization of oocysts in stool | Trimethroprim-sulfamethoxazole |

| Amebic dysentery | Tropical climate, more common in areas with poor sanitation | Men who have sex with men | Abdominal pain Bloody diarrhea | Identification of trophozoits and cysts in stool | Metronidazole, 500–750 mg, 3 times daily for 10 d + intraluminal agent |

Table 2.

Overview of helminth infections causing gastroenteritis

| Parasite | Geographic Region | At-risk Populations | Symptoms | Diagnosis | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascaris lumbricoides | Worldwide, but more prevalent in less-developed countries | Poor sanitation Affects both immunocompetent and immunocompromised |

Usually asymptomatic, but can present with obstructive symptoms | Direct visualization of eggs in stool | Albendazole, 400 mg, 1-time dose |

| S stercoralis | Tropical and semitropical regions | More severe infection in immunocompromised and alcoholic patients | Nausea, abdominal pain, or occult blood loss | ELISA for IgG against S stercoralis | Ivermectin, 200 mg/kg, 1-time dose |

| C philippinensis | Philippines Thailand Egypt |

Affects both immunocompetent and immunocompromised | Protein-losing enteropathy, steatorrhea | Direct visualization of eggs or larvae in stool | Albendazole, 200 mg, twice daily for 10 d Mebendazole, 200 mg, twice daily for 20 d |

| Hookworm—Necator americanus, Ancylostoma duodenale | Americas, South Pacific, Indonesia, Southern Asia, and Central Africa | Affects both immunocompetent and immunocompromised | Iron deficiency anemia | Direct visualization of eggs or larvae in stool | Albendazole, 400 mg, once Mebendazole, 100, mg, twice daily for 3 d |

| Whipworm—Trichuis trichiura | Temperate and tropical countries, more prevalent in areas with poor sanitation | Children | Iron deficiency anemia Abdominal pain Rectal bleeding Rectal prolapse |

Direct visualization of eggs or larvae in stool | Albendazole, 400 mg, and ivermectin, 200 μg/kg, 1 dose Mebendazole, 100 mg, twice daily for 3 e Albendazole, 400 mg, daily for 3 d |

| Pinworm—Enterobius vermicularis | No geographic constraints | Affects both immunocompetent and immunocompromised | Perianal pruritus | Cellophane tape test | Albendazole, 400 mg, once Mebendazole, 100 mg, once Administer second dose, 15 d after first to prevent reinfection |

| Hymenolepis species | Worldwide | Affects both immunocompetent and immunocompromised | Usually asymptomatic but heavy infections cause anorexia and diarrhea | Direct visualization of eggs in stool | Praziquantel, 25 mg/kg, once. Consider treating family members. |

| Diphyllobothrium species | Northern Europe, Russia, and Alaska | Most common in middle-aged men | Vitamin B12 deficiency, abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation | Direct visualization of eggs or larvae in stool | Praziquantel, 10 mg/kg, as a single dose |

| Taenia species | Worldwide | Affects both immunocompetent and immunocompromised | Intestinal infection is largely asymptomatic but can cause abdominal pain and diarrhea | Direct visualization of eggs in stool | Praziquantel, 10 mg/kg, as a single dose Albendazole, 400 mg, daily for 3 d |

| Schistosoma species | Tropical | People living in tropical rural areas with frequent fresh water contact | Noncirrhotic portal hypertension, variceal bleeding | Direct visualization of eggs in stool | Praziquantel 40–60 mg/kg (one or two divided doses) |

In the United States, infections by protozoa are the most frequent causes of parasitic gastroenteritis.1 Illness due to helminthic infections, however, occur especially in people with previous travel to or residence in locations where these agents are endemic. Diarrhea is a frequent symptom of protozoal gastroenteritis but not helminth infection. Parasites also can cause eosinophilic inflammation. Therefore, parasite and especially helminth infections should be included in differential diagnosis for patients who present with peripheral eosinophilia or in whom biopsies from the gastrointestinal tract show eosinophilic infiltrates.2 Stool studies often are essential in diagnostic work-up.

Although well appreciated for causing morbidity and mortality, some parasites also may benefit human health by improving the diversity of intestinal microbiota and assisting in development of a homeostatic healthy immune system. In this context, parasites that enhance immunoregulation may help protect from allergy, autoimmunity, and other immune-mediated disorders.3,4 This article focuses only on the diseases caused by parasites, but these complex eukaryotic organisms also may illuminate novel approaches of therapy for the chronic immune-mediated diseases now epidemic in highly industrialized locales.

PROTOZOAL GASTROENTERITIS

Four groups of protozoa, Giardia, Cryptosporidia, Isosopora, and Amoeba or Entamoeba, can cause gastroenteritis. Outbreaks of protozoal gastroenteritis usually are associated with poor sanitary conditions, and infection usually occurs after drinking contaminated water. A fifth protozoan, Toxoplasma gondii, utilizes the gastrointestinal tract of the cat as its definitive host for sexual reproduction. Humans serve as intermediary host but Toxoplasma sporozoites can invade the intestinal epithelium of humans and rarely cause intestinal symptoms.

GIARDIA GASTROENTERITIS

G intestinalis, also known as G lamblia or G duodenalis, is a microscopic protozoan, with adult trophozoites 10 μm to 20 μm in length. The source of infection usually is ingestion of contaminated water, such as lakes, ponds, or rivers. Although the Giardia trophozoites inhabit the human gut, they are shed in cyst form with the stool. Giardia cysts enable the parasite to survive outside the host and render the parasite resistant to chlorine-mediated disinfection. Therefore, swimming pools or public water supplies, if contaminated with human feces or agricultural overspills, can cause Giardia outbreaks. Although the infection usually is self-limited and responds to antibiotics, Giardia infection can create lasting gastrointestinal symptoms, such as gas, bloating, and diarrhea, which can be due to lactose or fructose intolerance, associated with disaccharides deficiency5,6 on intestinal brush border. Giardia infection also constitutes a frequent cause of nonulcer dyspepsia.

In clinical practice, Giardia infestation usually is diagnosed with stool studies, including nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs). Direct duodenal biopsy has poor sensitivity, although NAATs are under investigation to see whether they can increase the diagnostic yield from duodenal biopsies.7 The disease is treated easily with metronidazole in most cases, although drug resistance has been reported in recent years.3

INTESTINAL CRYPTOSPORIDIOSIS

Cryptosporidium parvum causes a self-limited gastroenteritis in immunocompetent individuals, which presents with profuse diarrhea. It is transmitted easily because ingestion of as little as few hundred protozoa can cause diarrheal disease, and Cryptosporidia have constituted the leading cause waterborne outbreaks from pools or recreational water parks in recent years.8 Furthermore, Cryptosporidia cause severe and long-lasting diarrhea in immunosuppressed individuals, such as those with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) or organ transplant recipients. Diagnosis of Cryptosporidia in stool is difficult. Therefore, patients with suspected cryptosporidiosis are asked to send several stool samples, for identification of the parasite by acid-fast staining or its antigens by immunofluorescence or ELISA.9,10 Rarely, Cryptosporidia are diagnosed by careful examination of intestinal biopsies during histopathology and identification of basophilic, spherical structures, 3 μm to 8 μm in size, clustered along the epithelium.9 Cryptosporidiosis in immunocompetent patients does not require treatment, except making sure that patients (especially young children) do not get dehydrated. Immune reconstitution in patients treated for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-AIDS reduces colonization and, likewise, reducing immunosuppression should be considered in transplant recipients with profuse diarrhea due to C parvum. Immunocompetent patients with cryptosporidiosis can be treated with nitazoxanide, although the benefit of this approach in immunosuppressed patients is questionable.11

CYSTOISOSPORA GASTROENTERITIS

Cystoisospora belli is a unicellular protozoan, which inhabits the human intestine in tropical and subtropical climates. The parasite causes gastroenteritis associated with nonbloody diarrhea. Cystoisospora gastroenteritis is rare in developed countries. The infection is seen mostly in patients with HIV-AIDS, especially in sub-Saharan Africa or in immigrants from this region.12,13 Unlike cryptosporidiosis, gastroenteritis due to Cystoisospora rarely is seen in immunosuppressed patients and but can occur.14 Diagnosis is established by showing the oocysts in stool. Repeat sampling often is needed to increase the yield. Rarely, microscopic examination of duodenal aspirates or histopathologic examination of intestinal biopsies may make a diagnosis. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is the treatment of choice.

AMEBIC DYSENTERY

The protozoon Entamoeba histolytica causes bloody diarrhea called amebic dysentery. The parasite is transmitted fecal-orally. Tropical climate and poor sanitary conditions facilitate the transmission of the parasite. It also can affect men involved in sexual relationship with other men. A majority of infections due to E histolytica have a mild course with abdominal pain and loose bowel movements. A minority of patients, however, present with systemic symptoms, fever, and amebic dysentery. These cases can require differentiation from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), especially in patients whose presentation mimics ulcerative colitis but lack the clinical, colonoscopic, or histopathologic evidence for chronicity seen with IBD. The predilection of the pathogen for cecum and the ascending colon can help differentiate from ulcerative colitis, which uniformly affects the rectum and can involve more proximal segments of the colon in a contiguous fashion. The visualization of flask-shaped ulcers in colonic biopsies also can help with the differentiation of amebic dysentery from other causes of bloody diarrhea. Diagnosis rests on identification of organisms in freshly isolated stool specimens or colonic biopsies. E dispar is morphologically identical to E histolytica but rarely is pathogenic,15 if pathogenic at all. The 2 species can be distinguished by NAATs or by detection of antigens unique to E histolytica using immunochemistry or ELISA tests.16 Systemic treatment is with a 10-day course of metronidazole, which acts only on the trophozoite stage. Patients also should be treated with a luminally acting agent, such as paromomycin (a nonabsorbable aminoglycoside), to eradicate cysts and prevent reinfection.

HELMINTH INFECTIONS

Parasitic worms (helminths) now are encountered in nonendemic locales due to ease of travel and consumption of exotic cuisines. Helminths are grouped by phylum: nematodes (roundworms) and platyhelminthes (flatworms), the latter made up of cestodes (tapeworms) and trematodes (flukes). Although they all are called worms, they are evolutionarily vastly distant. Infection easily can be missed by health care providers, especially if a careful travel or emigration history is not obtained. Many helminths can survive for decades in a host. In areas where these infections are rare, they usually are diagnosed incidentally while testing for more common diseases. Helminth infection also can be hard to diagnose because it can cause little to no symptoms. Diagnosis may be made by stool studies, direct visualization, or serologic studies.17

NEMATODES (ROUNDWORMS)

Ascaris lumbricoides

Ascaris lumbricoides is a parasitic roundworm and a member of the group of soil-transmitted helminths (STHs). It is the largest nematode that can colonize humans. It infects as many as a quarter of the population of the world and is the most prevalent STH infection in humans.18 It infects mainly children living in lower socioeconomic locales.19 The adult parasites live in the human intestine. Infection occurs by ingesting eggs that are passed in the feces of infected individuals. This can occur through fecal-oral routes with handling contaminated detritus or through consumption of vegetables or fruits that have been exposed.20,21 The eggs are relatively sticky and can adhere to the surface of many items that then are ngested.22 Risk factors for developing infection include poverty, poor living conditions, and inadequate sewage disposal.20 Unfortunately, sterilizing immunity does not develop after infection. Eggs are infective only once they are embryonated and contain third-stage larvae. The ingested eggs hatch in the small bowel (duodenum/jejunum). Larvae migrate to the lungs, exit through the alveoli, are coughed-up, and then are swallowed to re-reach the intestine. They become mature adults after 14 days to 20 days, with female adults releasing millions of eggs into feces by approximately 70 days after ingestion. The adult worms live for approximately 1 year. The worms are unable to multiply in the host because their eggs require incubation outside the host to reach infectivity.20,23

Often infection is asymptomatic and worms are found unexpectedly on endoscopy or seen in radiographic imaging. Clinical manifestation typically occurs in those only with heavy worm burden. Symptoms of heavy infection reflect effects of larval migration and adult worm behavior. Pulmonary symptoms can include cough, wheezing, and fever. As the larvae move into the lung alveoli, they can cause hemorrhage and consolidation. Gastrointestinal tract infection can lead to abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. A large number of adult worms can cause partial or complete small bowel obstruction. Worms also may invade the bile ducts, liver, or pancreatic ducts, leading to abscesses, ascending cholangitis, acalculous cholecystitis, or acute pancreatitis. Rare fatal infection occurs when obstruction leads to intestinal necrosis and bowel perforation.20,21,23

Infection usually is diagnosed after an adult worm is passed with defecation. Microscopic eggs are identifiable in stool but this requires direct visual identification by experienced personnel.24 Furthermore, identification can be problematic with low worm burden. Even double-slide Kato-Katz (2 separate slides from the same sample) has a sensitivity of only 64.6% and can be as low as 55% in low parasitic burden.25 A recent study looked at identifying helminth DNA in stool using NAATs showed higher sensitivity for Ascaris but more studies are needed to determine implications for clinical practice.18,24 Adult worms can be identified during endoscopy or on imaging. They have characteristic appearance on ultrasound, appearing as long stripes that do not cast acoustic shadows. Serum antibody testing is not done routinely because it may not reflect active infection in patients from endemic areas. Chronic infection usually is not associated with peripheral eosinophilia because the adult worms reside in the intestinal lumen.26

Current drugs approved for treatment include albendazole, mebendazole, levami-sole, and pyrantel pamoate, with a cure rate of more than 95% (93.2–97.3).23,27 Asymptomatic colonization typically is treated with a single dose of albendazole at 400 mg. Albendazole has potential teratogenicity; so typically pregnant women are treated with pyrantel pamoate, although studies have shown no adverse events from albendazole compared with placebo.28 A recent Cochrane review compared albendazole, mebendazole, and ivermectin. All drugs were highly effective for both parasitologic cure and reduced egg excretion. There was no clear difference in efficacy among the 3 drugs.19 If pulmonary manifestations are present, a 400-mg dose of albendazole dose should be given twice, 1 month apart. Patients also should receive steroids to reduce the risk of developing pneumonitis. Intestinal obstruction should be treated conservatively with bowel rest, decompression, and a single dose of albendazole. If the worms migrate into the biliary system, treatment should be given for several days because the worms are susceptible to the drug only after they migrate out of the bile duct. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for worm extraction may be needed in cases of biliary obstruction and ascending cholangitis. Although the infection typically is easy to treat, in most endemic areas, patients become rapidly reinfected.20,27 Health education and improved sanitation become inconsequential for long-term infection control.20,23

Strongyloides stercoralis

Strongyloides stercoralis is a roundworm whose larvae reside in soil in tropical and subtropical regions. Adults reside in the small intestine.29 The parasite is estimated to infect upwards of 370 million people worldwide. Although infections most often are asymptomatic, mortality rates can reach as high as 85% in immunocompromised patients.

The life cycle of the nematode parasite occurs in 2 parts. Infection begins after filariform larvae residing in soil penetrate skin. The first stage of infection usually is asymptomatic, but when symptoms are present, they result from a local allergic reaction or urticarial serpiginous rash at the site of larva entry.29,30 Larvae then migrate through the skin into the blood stream and to the lungs. Passage through the lungs can cause Loeffler syndrome, with symptoms of wheezing, cough, and shortness of breath. Pulmonary infiltrates also may be present on radiologic imaging. Entry into the gut is accomplished after larvae penetrate alveoli, migrate up the tracheobronchial tree, and subsequently are swallowed. Maturation is completed in the small intestine when adult worms lodge in submucosal tissue and molt. Gastrointestinal symptoms may occur beginning 2 weeks after exposure and usually are fairly nonspecific and can include pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and malabsorption.30 Acute infection that goes undiagnosed can progress to chronic infection. Deposited parasite eggs hatch in the small intestinal lumen, releasing rhabditiform larvae that pass with the stool. Some of the rhabditiform larvae can develop into infective filariform larvae, penetrate the intestinal epithelium, and restart the life cycle. This ability to cause autoinfection allows the parasite to persist its host for decades.30 Most patients with chronic infection have uncomplicated disease and remain asymptomatic. Others have intermittent attacks of gastrointestinal or pulmonary symptoms. Many patients also have peripheral eosinophilia. A small subset of patients with chronic infection can present with hyperinfection syndrome or disseminated strongyloidiasis. In hyperinfection, systemic sepsis and multiorgan failure can occur as a consequence of extensive larva-induced injury.29 Disseminated disease occurs when parasites are present in organs outside of lungs, skin, and the gastrointestinal track. Disseminated strongyloidiasis occurs mainly in immunocompromised hosts or can occur when asymptomatic patients are treated with steroids or immunosuppression for an unrelated condition.29 Studies have documented increased prevalence of chronic infection in alcoholic patients. The exact mechanism is unclear but may be related to altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis or reduced gastrointestinal transit.31

Diagnosis can be challenging because many infected individuals remain asymptomatic. Diagnosis can be made by detecting live larvae in feces on agar plate culture. Larvae often are present in the stool intermittently or in such low numbers that detection is difficult.30,32 Diagnostic sensitivity improves from 50% to almost 100%, when the number of stool specimens tested is increased from 3 to 7.30,33 Other diagnostic tests include NAATs on stool samples. Even NAATs require testing multiple stool samples.30,33 Low sensitivity is thought to be due to nucleases and reaction inhibitors present in feces. Blood testing for IgG antibodies against Strongyloides species is the preferred method for detection. IgG antibodies against S stercoralis are detectable 2 weeks after infection, peak at 6, and then can be present up to 20 weeks after clearance of the infection. Antibody titer is lower in patients with mild or asymptomatic infections. Detection of IgG4 anti-Strongyloides antibodies has improved specificity compared with other classes of anti-Stronglyloides IgG.30,34,35

The treatment goal should be complete eradication to prevent autoinfection and associated hyperinfection and dissemination syndromes. Standard treatment is with a single dose of ivermectin, which is sufficient to kill adult worms but does not affect larvae migrating through tissue. Repeat doses of ivermectin, given 2 weeks after the first dose, prevent recurrent autoinfection. Recently, a multicenter study showed that a single dose was as effective as repeated dosing36 so this repeat treatment may not be required. Immunocompromised patients or patients with hyperinfection continue to require repeat dosing at day 3, day 16, and day 17 after the initial dose.20

Capillaria philippinensis

Parasitic infection with Capillaria philippinensis occurs after eating parasites infected raw freshwater fish. The infection is deadly if not promptly treated.37 The first reported cases were in the Philippines. Capillariasis is a zoonosis; freshwater fish are the intermediate host, with the definitive reservoir hosts being other animals that eat these fish (such as birds).38,39 Larvae mature into adults in the small intestine of the definitive hosts and deposit shelled eggs that drop back into the water, embryonate, and are ingested by fish completing the life cycle. Female adults also deposit eggs that lack a shell and embryonate in the host to cause autoinfection. Escalating infection in humans produces a sprue-like illness characterized by protein-losing enteropathy and steatorrhea. Diagnosis is made by identifying egg and larvae in feces. The eggs have a characteristic peanut shape that aids in their identification. Stool ELISA tests detecting C philippinensis coproantigen or NAATs detecting its DNA have increased sensitivity and specificity greatly compared with microscopic examination.38 Treatment consists of an extended course of either albendazole or mebendazole.20

Hookworms (Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale)

Hookworms (Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale) infect more than 400 million people worldwide. Infection is most prevalent in tropical regions of South America, Africa, and Asia. Chronic infection can cause a wide array of nonspecific symptoms, including fatigue, abdominal pain, weight loss, anemia, and diarrhea. Infection in pregnant women can lead to poor fetal outcomes, including increased mortality and low birthweight.40

The life cycle begins when eggs are passed out of the body and hatch to release larvae that mature through several stages before they become infective. The infective larvae penetrate human skin, pass through the blood stream to the lungs, gain access to the airway, and eventually are swallowed. Adult worms can live in the small intestine for up to 10 years.40

Symptoms are based on disease burden. Patients with low parasite burden usually are asymptomatic. A high parasitic burden can cause iron deficiency anemia as adult worms feed on intestinal epithelial cells and blood. Reinfection can occur after treatment, because there is no sterilizing host immunity.20,41

Diagnosis is made by direct visualization of eggs under the microscope using the Kato-Katz technique. Low-level infections may be missed with this method due to decreased egg excretion in the stool.42 Formol-ether concentration techniques and NAATs have increased the sensitivity.42,43

Infection is treated either with 3 days of mebendazole or a single dose of albendazole.41 In endemic areas, it is important to improve sanitation with clean water supply and sewage treatment.43

Whipworm (Trichuris trichiura)

The whipworm Trichuris trichiura is a roundworm that infects humans. Heavy disease burden is seen in children in areas with poor sanitation.44 The life cycle begins when eggs from human feces are deposited in soil. The eggs mature in 2 weeks to 3 weeks and become infective. Warm and humid climates are important for this maturation. Due to poor hygiene, infectious eggs are ingested and then hatch in the small intestine. Most larvae then migrate to the cecum, where they mature and anchor to the mucosa.45

Most infections are asymptomatic but, when symptomatic, symptoms typically include abdominal pain and rectal bleeding. Nighttime stooling with mucus discharge also can be reported by patients. Heavy worm infestation can lead to rectal prolapse. Children can develop abnormal growth and impaired cognitive development as a result of iron deficiency anemia and poor nutrition worsened by the worm burden. The worm can live upwards of 4 years.

Diagnosis usually is made by direct visualization of eggs using the Kato-Katz method. The eggs have a characteristic lemon shape.46 Diagnosis can be challenging because ability to detect eggs in stool samples is low with low parasite burden and is dependent on the timing of stool collection in relation to release of eggs from the female worm. Stool NAATs demonstrated higher sensitivity (93.7%) than microscopic examination but still had only moderate sample to sample reproducibility, suggesting the need to test multiple stool samples.42

Options for treatment include albendazole or mebendazole, although efficacy is less than in treatment of other STHs. The lower efficacy of current antihelminthic medications has spurred studies evaluating combination therapy. A recent study showed better efficacy with combined therapy of ivermectin-albendazole compared with monotherapy.42 A recent randomized control trial assessed efficacy of moxidectin coadministered with albendazole versus moxidectin monotherapy for treatment. Cure rates of 62% to 69% with moxidectin with 400 mg of albendazole were achieved.47 Another double-blind, randomized controlled trial in children looked at combination of albendazole with pyrantel pamoate compared with albendazole monotherapy. Unfortunately, this study showed that combination therapy did not improve cure rates or reduce egg burden48 compared with monotherapy.

Pinworm (Enterobius vermicularis)

Humans are the only natural host for Enterobius vermicularis, commonly called pinworm. Infection typically occurs in children by direct ingestion of eggs.49 Risk factors for developing the infection include poor hygiene and eating after touching contaminated items.50 The organism spreads easily in confined living situations.

Once ingested, the eggs hatch to release larvae that migrate to the ileum and cecum, develop into adult worms, and begin to deposit eggs in approximately 1 month. The infection usually is asymptomatic. At night, female pinworms migrate to and deposit eggs in the perianal area, which can cause significant pruritus. Itching can cause a continued cycle of infection by ingesting the eggs from the fingers and restarting the life cycle of the worm.51

Symptoms, if present, typically embody perianal pruritus. With excessive itching, perianal excoriation can occur. Abdominal pain, watery diarrhea, insomnia (from itching), and vaginitis52 also have been reported. If the worms cause local inflammation around the appendiceal opening, appendicitis can occur.50

Diagnosis is made after isolating the organism on an adhesive surface and examining it under the microscope. This typically occurs by placing tape over the perianal area. Stool studies are not helpful because the egg deposition occurs outside the intestine.51

Treatment consists of albendazole, 400 mg, given twice with the second dose occurring 2 weeks after the initial dose. Mebendazole also can be given in a similar fashion but at a dose of 100 mg. Reinfection can occur especially within the same household, so the entire household should be treated regardless of symptoms once 1 member is diagnosed.

Anisakiasis

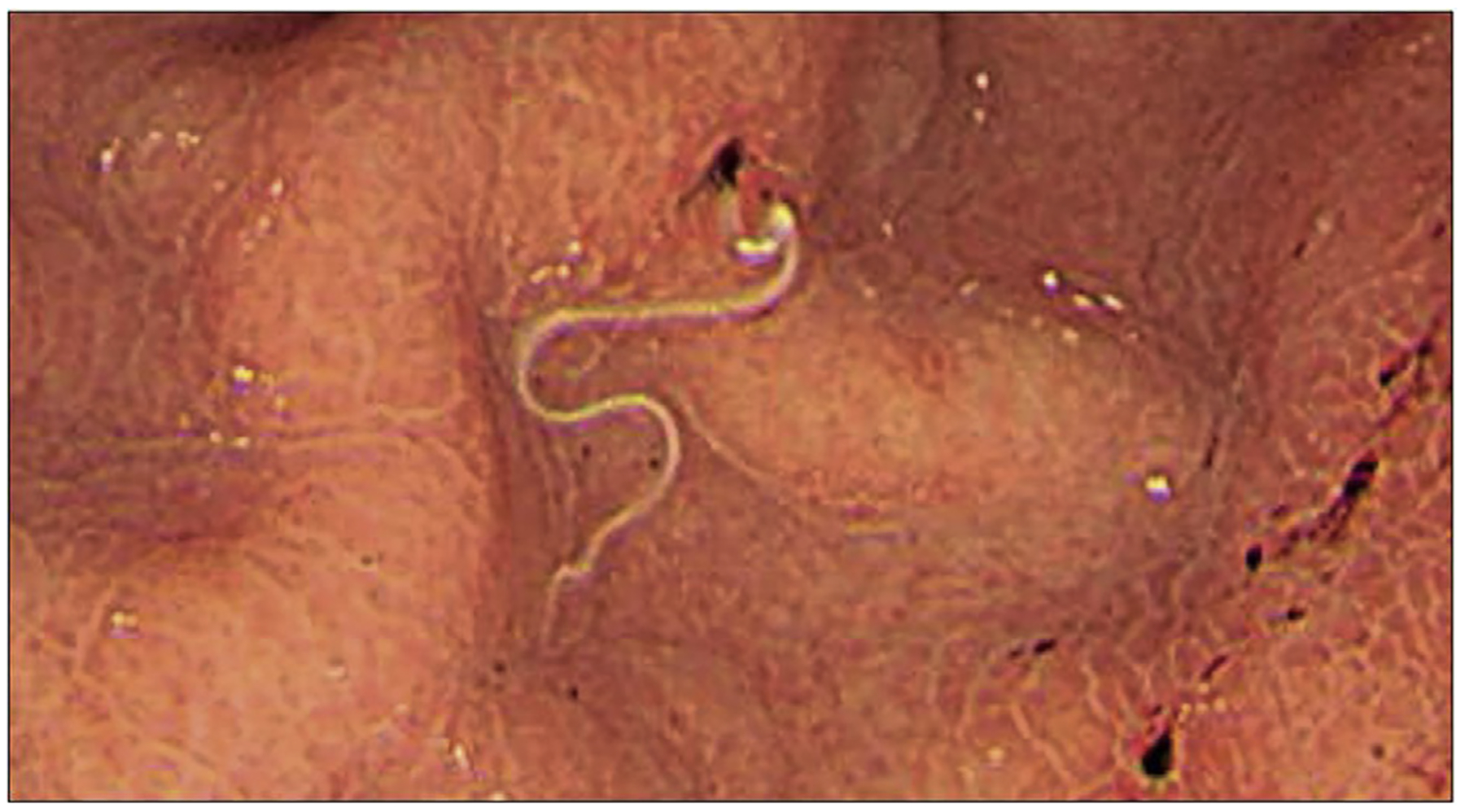

Anisakiasis is caused by transient infection with Anisakis simplex, A pegreffii, or A decipiens after consumption of raw fish. The worms cause a self-limited infestation in humans53 (Fig. 1), which can cause erosions, ulcers, or even perforation in the stomach, when they try to escape the lumen. The risk of bleeding gastric ulcers is approximately only 0.5%. Treatment includes albendazole or endoscopic removal of worms.54,55

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic appearance of A simplex in a patient seen for abdominal pain. (From Kondo T. DWoe sushi: gastric anisakiasis, The Lancet 2018;392(10155):1340; with permission.)

CESTODES (TAPEWORMS)

Hymenolepis nana and Hymenolepis diminuta

Dwarf tapeworm (Hymenolepis nana) is the most common cestode that infects humans. Adults measure 1.5 cm to 4.0 cm in length. H diminuta can grow to nearly twice that length. Among cestodes, H nana is unique in that it can be transmitted directly from person to person. This direct pathway permits autoinfection with increasing symptoms. H nana also infects rodents but the strains that infect rodents appear to be different than the strains that infect people. The rodent tapeworm (H diminuta) normally infect rodents but humans also can harbor the parasite (zoonotic infection).56 Hymenolepis eggs from either species are passed with stool and can be ingested by small arthropods like flour beetles or grain beetles. There they hatch to release an oncosphere and develop into cysticercoid larvae. Rodents or humans that ingest the infected arthropods acquire the helminth, which evaginates to form a scolex that attaches to the intestinal mucosa and matures to form a chain of proglottids, each containing numerous eggs. H nana can dispense with the need for an arthropod intermediate host. Ingested eggs hatch in the human small intestine, each releasing an oncosphere that penetrates the mucosa and develops into a cysticercoid larva. The cysticercoid escapes from a ruptured villus, forms a scolex and completes the life cycle, as discussed previously. It even is possible for the H nana eggs to hatch directly without needing passage outside of the host (autoinfection). Direct infection permits spread to close associates (eg, household members) and autoinfection permits escalation of symptoms. Patients usually are asymptomatic but with heavy infections can have anorexia, bloating, cramps, and diarrhea. Diagnosis is by finding eggs in the stool or serendipitously by seeing the adult tapeworms on endoscopy.57 Treatment of infection with either species is 1 dose of praziquantel, 25 mg/kg. Patients with H nana should have a second dose of 25 mg/kg, 1 week after the first. Household members also should be tested and treated for H nana.

Diphyllobothrium Species

Diphyllobothriasis (fish tapeworm) is a parasitic zoonosis caused by eating poorly cooked fish harboring infectious larvae. Infection can cause a wide array of symptoms and disease severity. There are a total of 18 described species of Diphyllobothrium that can infect humans but a majority are due to either D latum or D nihonkaiense. Infection is most common in middle-aged men. It is postulated that infection rates may increase with rising preference for eating raw fish and new methods for rapidly freezing fish.58

The complex life cycle begins with embryonation of eggs in water under favorable conditions. Transmission to humans occurs with ingestion of raw or undercooked fish infected with plerocercoid larvae. Once ingested, the mature tapeworm attaches to the host’s small intestine and matures into a tapeworm. In the small intestine, these worms can cause changes in structure and neuroendocrine response and secretion.58 The classic symptom of D latum infection is pernicious anemia due to vitamin B12 deficiency because the parasite competes with the host’s absorption and use of the vitamin. Diagnosis is made by direct visualization of eggs or proglottids in stool with molecular testing to determine species.16 Treatment consists of a single dose of praziquantel. Praziquantel can be given safely in pregnancy.59

Taenia Species

Zoonotic tapeworms that infect people include beef tapeworm (Taenia saginata) and pork tapeworms (T solium and T asiatica). In addition to cattle, intermediate hosts for T saginata include reindeer, and buffalo. T saginata is the most common tapeworm infection in humans. The prevalence is higher in the Pacific and Asia and in areas with poor sanitation where there is not routine enforcement of meat inspection.60 Infection occurs after humans consume raw or undercooked meat that contains encysted parasitic larvae.61,62

The reproductive cycle begins when cattle or swine ingest water or a vegetation contaminated with stool containing parasitic eggs. Ingested eggs release onco-spheres that break through the intestinal wall and disseminate through the body where the cysticerci encyst in striated muscle other tissues. After ingestion of raw or undercooked meat, the cysticerci evaginate in human body to create a scolex that attaches to the jejunum. Once attached, the parasite forms a tape-like chain of proglottids which mature, break from the distal end, and release eggs that pass with the stool. Worms can live in the human intestine for many years.

Symptoms can include abdominal pain and diarrhea although most people are asymptomatic. The eggs of T saginata are not infective to humans whereas the eggs of T solium are infective. Ingesting eggs of T solium leads to cysticercosis. Dissemination to the brain results in neurocysticercosis, which is a frequent cause of epilepsy in endemic regions.

Diagnosis usually is made by microscopic examination to find eggs or proglottids in the stool. Fecal examination often allows for diagnosis of the genus but not the species as the eggs are indistinguishable. If proglottids are seen, these can be distinguished by length and number of uterine branches. Species can be differentiated using NAATs63 or through antibody detection for T solium excretory-secretory antigen. Cysticercosis can be tested for serologically64 but neurocysticercosis requires imaging in addition to serodiagnosis.65

Common antihelmintic drugs typically provide good coverage for treatment. Historically, praziquantel and niclosamide are considered first-line treatment options although niclosamide is not available in the United States. Albendazole also is effective. Albendazole and praziquantel cross the blood-brain barrier and can cause neurologic symptoms in patients with latent neurocysticercosis. Neurocysticercosis is treated with albendazole and the addition of an antiepileptic along with glucocorticoids to limit neuroinflammation.65

Echinococcus Species

Cystic echinococcosis, also called hydatid cyst disease, results from a zoonotic infection by one of the tapeworms of the Echinococcus species, with E granulosus the most well-known.66 Humans serve as intermediate hosts harboring the metacestode form. Ingested parasite eggs hatch in the intestinal lumen, each releasing an oncosphere that penetrates the mucosa and travels with the portal blood to the liver and mesenteric tissues. The parasite develops into a fluid-filled cyst harboring many (thousands) protoscolices. If the cyst ruptures, the released protoscolices can develop into disseminated secondary cysts. Rupture also result in anaphylaxis due to release of antigenic fluid contents. Most often, the infection is asymptomatic unless the cyst size affects organ function or erodes into a bile duct (cystobiliary fistula). Humans do not harbor adult worms, so no eggs are present in stool. Diagnosis is made by ultrasound or MRI of cysts.67 Calcification is not a reliable sign of cyst nonviability. Treatment depends on cyst location, cyst complexity, and secondary complications. Treatment options include surgery, sclerosis (puncture, aspiration, injection, or reaspiration) to kill the germinal layer of the cyst, and drug therapy with albendazole (2 doses of 5 mg/kg/d, for up to 6 months).66

TREMATODES (FLUKES)

Blood Flukes (Schistosoma Species)

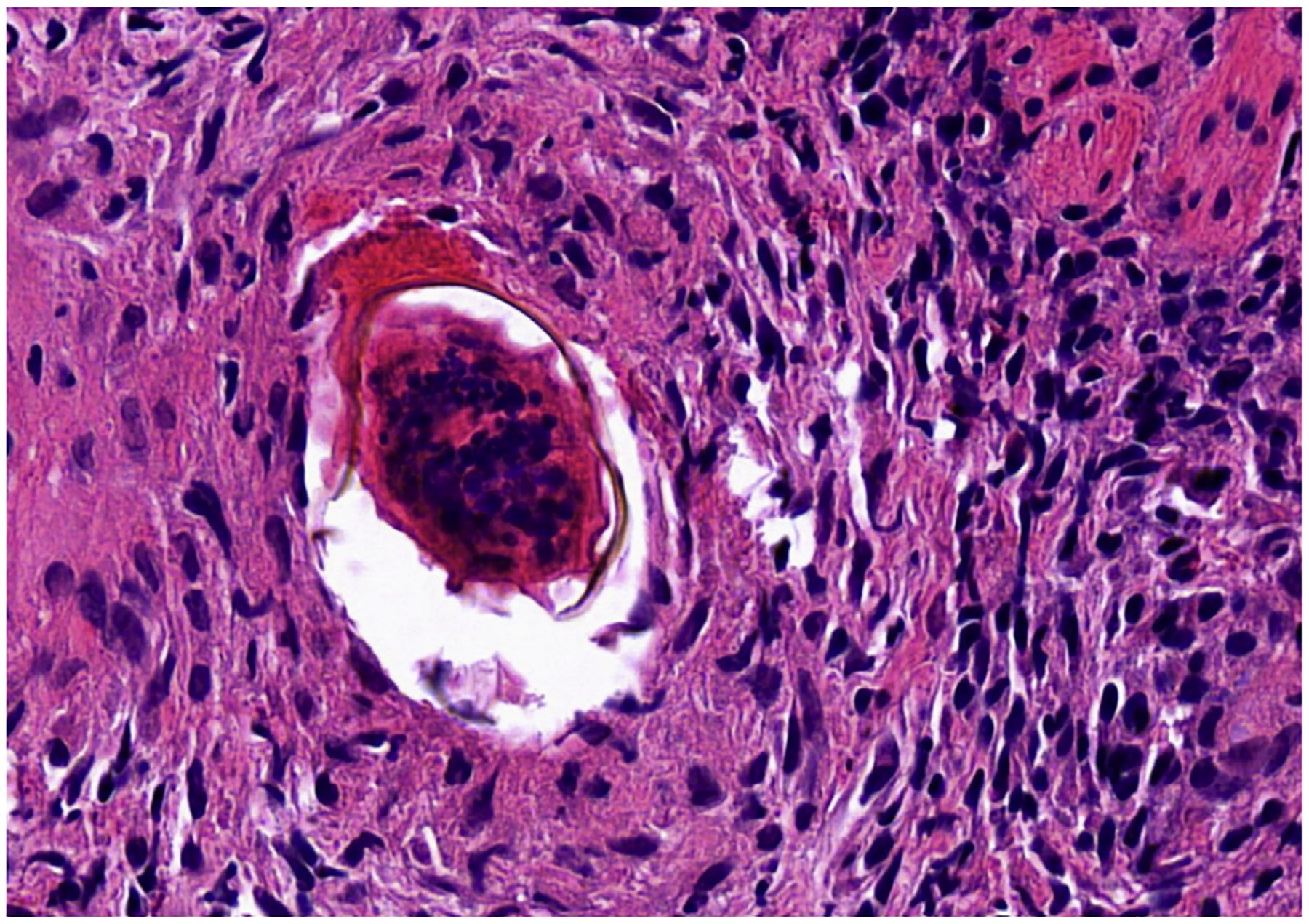

Schistosomiasis is a parasitic disease caused by 1 of several species of the Schistosoma that reside in veins draining the hollow viscera. Infection occurs by contacting contaminated water.68 In humans, infection in the intestinal and hepatic system is caused by S mansoni, S japonicum, S intercalatum, or S mekongi. The life cycle is complex, needing the use of a tropical aquatic snail as an intermediate host. After multiplying asexually in the snails, larvae (cercariae) escape into the water and enter the human body by penetrating through the host’s intact skin. From the skin, they pass with blood to the lungs and eventually migrate to the mesenteric venules, where they mature and begin to deposit eggs intravascularly.69 Acute symptoms may consist of abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, or malaise. Chronic disease occurs from the local inflammation precipitated by eggs trapped in surrounding tissue. Disease burden and symptoms depend on the organ system involved. In intestinal involvement, eggs either are trapped in tissue or pass through the intestinal wall to cause granulomatous inflammation, bleeding, or even pseudopolyps. In the liver, eggs can be trapped in the presinusoidal vessels causing presinusoidal (pipestem) fibrosis, noncirrhotic portal hypertension, and esophageal varices.70 Diagnosis typically is made by detection of eggs in feces. Nonetheless, diagnosis of a patient with schistosomiasis may require a high degree of suspicion guided by serology and classic radiologic findings. Rarely, investigation may find Schistosoma eggs and the granulomas in tissue biopsies71 (Fig. 2), although this is very insensitive. Treatment typically consists of praziquantel, 40 mg/kg, as a single dose.68,70

Fig. 2.

Colonic biopsy from a patient with schistosomiasis with the egg embedded in lamina propria and surrounded by granulomatous reaction (hematoxylin-eosin, 400x original magnification). (Courtesy of Dr Sarag Boukhar, University of Iowa.)

Intestinal Flukes

There are many intestinal flukes that can infect humans, but the most common offenders are Fasciolopsis buski, Echinostoma species, and Heterophyes species. They all have a complex life cycle: adult worms deposit eggs that pass in the stool, eggs hatch in water to release miracidia that infect snails, infected snails release cercariae, cercariae encyst on plants (F buski) or infect then encyst in fish and/or mollusks (Echinostoma spp and Heterophyes spp) as metacercariae. Once ingested, metacercariae excyst in the intestine, attach to the mucosa, and mature into adult worms. Intestinal flukes do not produce symptoms in most people but can cause abdominal discomfort and diarrhea if present in high numbers. Diagnosis is made by identifying flukes on endoscopy72,73 or, more commonly, by identifying eggs passed with stool. Treatment is with 1 dose of praziquantel, 25 mg/kg.

Liver Flukes

Liver flukes reside in the bile ducts. They have a complex lifecycle employing freshwater snails as an intermediate host. People acquire these parasites by eating metacercariae encysted on freshwater plants (Fasciola hepatica and F gigantica) or in raw or undercooked fish (Clonorchis sinensis, Opisthorchis viverrini, and O felineus). Fasciola metacercariae excyst in the small intestine, burrow through the intestinal wall to the peritoneal cavity, migrate to the liver, and then journey through the hepatic parenchyma to the bile ducts. C sinensis and Opisthorchis spp excyst in the stomach and small bowel then migrate along the mucosa to the ampulla and then enter the bile duct. Once in the bile ducts, the organisms mature into adult worms that release eggs that pass with bile into the stool, and if deposited in fresh water, hatch to release miracidia that then infect snails. Liver flukes are long-lived (decades) and cause no symptoms in most people. When symptomatic, liver flukes cause recurrent cholangitis, biliary duct dilation/obstruction, and rarely pancreatitis or eosinophilic liver abscess.74 The most worrisome complication from C sinensis and O viverrine is cholangiocarcinoma.75,76 The longevity of the parasite and the risk for cholangiocarcinoma drive the recommendation to screen individuals from endemic areas for these liver flukes.

Diagnosis is made by finding eggs in the stool or by seeing curvilinear lucencies in the bile duct on ERCP.77,78 Fascioliasis requires treatment with triclabendazole (10 mg/kg, single dose) whereas C sinensis and Opisthorchis spp can be treated with praziquantel (25 mg/kg, every 8 hours for 3 doses).

HELMINTHS AS IMMUNE MODULATORS

According to hygiene hypothesis, early childhood exposure to infectious agents, such as helminths,protect from immune-mediated diseases.79 Helminth infections are common in developing countries, in which public hygiene is less advanced and immune-mediated diseases are less frequent, whereas immune-mediated diseases are on the rise in industrialized societies practicing high levels of sanitation.80,81 The idea that helminths can regulate aberrant immune reactivity in these disorders was promoted by further experimental data demonstrating that helminths stimulate immune regulatory pathways and suppress inflammation in animal models.82 Furthermore, some human trials have reported potential benefit in using helminths to regulate immunity in patients with celiac disease, IBD, or other immune-mediated disorders.82–84 These observations gave rise to current research to determine the immunologic pathways exploited by helminths that protect from various immune-mediated pathologies.85

Helminths alter immune reactivity of mammalian host through the effect of their own products85 or through altering the composition of intestinal microbiota.86,87 In this context, intestinal microbiota has emerged as a factor contributing to the induction of or protection from immune-mediated diseases.88 Further research on helminths and their interaction with microbiota is expected to lead to prevention and better management of immune-mediated disorders.

SUMMARY

Gastroenteritis and hepatobiliary disease due to various parasites continue to threaten public health despite advances in hygienic practices and sanitation. Parasites also can cause lethal and devastating gastroenteritis in immunosuppressed patient groups. Careful history and a thorough diagnostic work-up are essential for the diagnosis and management of parasitic infection. Basic research on helminthic parasites also can identify factors that may protect from developing immune-mediated disorders and improve clinical care of patients with these disorders.

CLINICS CARE POINTS.

In case of clinical suspicion, the healthcare provider should alert the laboratory for the possibility of a parasitic infection, because the laboratory may not routinely test for helminth eggs or check the specimen for the presence of protozoa.

Parasitic infections and especially helminths should be included in the differential diagnosis for patients who present with peripheral eosinophilia.

A careful history on travel or emigration is important in the diagnosis of parasitic diseases.

Detection of a parasite can occasionally surprise the endoscopist during the diagnostic work-up.

KEY POINTS.

Protozoa or helminths are rare causes of gastroenteritis in industrialized countries, but in developing countries they cause significant morbidity.

Certain exposures (eg. drinking shallow well water and eating raw or poorly cooked meats) or medical conditions (eg. immune suppression) can permit devastating parasitic infections in gastrointestinal tract.

Helminths alter the composition of gut microbiota. In this context, helminth infection is investigated as a regulator of immune diseases.

DISCLOSURE

This work was supported by Merit Awards from the Department of Veterans Affairs BX002715 (D.E. Elliott) and BX002906 (M.N. Ince).

REFERENCES

- 1.La Via WV, B1P. Parasitic gastroenteritis. Pediatr Ann 1994;23(10):556–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehta P, Furuta GT. Eosinophils in gastrointestinal disorders: eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel diseases, and parasitic infections. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2015;35(3):413–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leung AKC, Leung AAM, Wong AHC, et al. Giardiasis: an overview. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov 2019;13(2):134–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayelign B, Akalu Y, Teferi B, et al. Helminth induced immunoregulation and novel therapeutic avenue of allergy. J Asthma Allergy 2020;13:439–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trelis M, Taroncher-Ferrer S, Gozalbo M, et al. Giardia intestinalis and fructose malabsorption: a frequent association. Nutrients 2019;11(12):2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rana SV, Bhasin DK, Vinayak VK. Lactose hydrogen breath test in Giardia lamblia-positive patients. Dig Dis Sci 2005;50(2):259–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jangra M, Dutta U, Shah J, et al. Role of polymerase chain reaction in stool and duodenal biopsy for diagnosis of giardiasis in patients with persistent/chronic diarrhea. Dig Dis Sci 2020;65(8):2345–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Painter JE, Gargano JW, Collier SA, et al. Giardiasis surveillance – United States, 2011–2012. MMWR Suppl 2015;64(3):15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khurana S, Chaudhary P. Laboratory diagnosis of cryptosporidiosis. Trop Parasitol 2018;8(1):2–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saha R, Saxena B, Jamir ST, et al. Prevalence of cryptosporidiosis in symptomatic immunocompetent children and comparative evaluation of its diagnosis by Ziehl-Neelsen staining and antigen detection techniques. Trop Parasitol 2019; 9(1):18–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.La Hoz RM, Morris MI, Practice ASTIDCo. Intestinal parasites including cryptosporidium, cyclospora, giardia, and microsporidia, entamoeba histolytica, strongyloides, schistosomiasis, and echinococcus: guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant 2019;33(9):e13618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang ZD, Liu Q, Liu HH, et al. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium, microsporidia and Isospora infection in HIV-infected people: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasites & vectors 2018;11(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lagrange-Xelot M, Porcher R, Sarfati C, et al. Isosporiasis in patients with HIV infection in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era in France. HIV Med 2008; 9(2):126–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stein J, Tannich E, Hartmann F. An unusual complication in ulcerative colitis during treatment with azathioprine and infliximab: Isospora belli as ‘Casus belli. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013. bcr2013009837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliveira FM, Neumann E, Gomes MA, et al. Entamoeba dispar: could it be pathogenic. Trop Parasitol 2015;5(1):9–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonin P, Trudel L. Detection and differentiation of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar isolates in clinical samples by PCR and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol 2003;41(1):237–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ince MN and Elliott DE. Intestinal worms. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt L, editors. Schlesinger and Fortran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease. 12th edition;-Philadelphia,USA:Elsevier.2020:114:1847–1867.e5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pilotte N, Maasch JRMA, Easton AV, et al. Targeting a highly repeated germline DNA sequence for improved real-time PCR-based detection of Ascaris infection in human stool. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(7):e0007593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conterno LO, Turchi MD, Corrêa I, et al. Anthelmintic drugs for treating ascariasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;(4):CD010599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sleisenger MH, Feldman M, Friedman LS, et al. Sleisenger & Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. 8th edition.Philadelphia: Saunders, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Tameemi K, Kabakli R. Ascaris lumbricoides: Epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment and control. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research 2020; 13(4):8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holland POLCV. The public health importance of Ascaris Lumbricoides Parasitology 2000. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Leung AK, Leung AA, Wong AH, et al. Human ascariasis: an updated review. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov 2020;14(2):133–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benjamin-Chung J, Pilotte N, Ercumen A, et al. Comparison of multi-parallel qPCR and double-slide Kato-Katz for detection of soil-transmitted helminth infection among children in rural Bangladesh. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020;14(4): e0008087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nikolay BBS, Pullan RL. Sensitivity of diagnostic tests for human soil-transmitted helminth infections: a meta-analysis in the absence of a true gold standard. Int J Parasitol 2014;44(11):765–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weller PF. Eosinophilia in travelers. Med Clin North Am 1992;76(6):1413–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chai JY, Sohn WM, Hong SJ, et al. Effect of mass drug administration with a single dose of albendazole on ascaris lumbricoides and trichuris trichiura infection among school children in Yangon Region, Myanmar. Korean J Parasitol 2020; 58(2):195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ndibazza J, Muhangi L, Akishule D, et al. Effects of deworming during pregnancy on maternal and perinatal outcomes in Entebbe, Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50(4):531–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karanam LS, Basavraj GK, Papireddy CKR. Strongyloides stercoralis Hyper infection Syndrome. Indian J Surg 2020, May 12;1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arifin N, Hanafiah KM, Ahmad H, et al. Serodiagnosis and early detection of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2019;52(3):371–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Souza JN, Oliveira CL, Araujo WAC, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis in alcoholic patients: implications of alcohol intake in the frequency of infection and parasite load. Pathogens 2020;9(6):422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaewrat W, Sengthong C, Yingklang M, et al. Improved agar plate culture conditions for diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis. Acta Trop 2020;203:105291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dacal E, Saugar JM, Soler T, et al. Parasitological versus molecular diagnosis of strongyloidiasis in serial stool samples: how many? J Helminthol 2018;92(1):12–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bisoffi Z, Buonfrate D, Sequi M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of five serologic tests for Strongyloides stercoralis infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014;8(1):e2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norsyahida A, Riazi M, Sadjjadi S, et al. Laboratory detection of strongyloidiasis: IgG-, IgG4-and IgE-ELISAs and cross-reactivity with lymphatic filariasis. Parasite Immunol 2013;35(5–6):174–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buonfrate D, Salas-Coronas J, Munoz J, et al. Multiple-dose versus single-dose ivermectin for Strongyloides stercoralis infection (Strong Treat 1 to 4): a multi-centre, open-label, phase 3, randomised controlled superiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2019;19(11):1181–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Dib N, Ali MI. Can thick-shelled eggs of Capillaria philippinensis embryonate within the host? J Parasit Dis 2020;44(3):666–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khalifa MM, Abdel-Rahman SM, Bakir HY, et al. Comparison of the diagnostic performance of microscopic examination, Copro-ELISA, and Copro-PCR in the diagnosis of Capillaria philippinensis infections. PLoS One 2020;15(6):e0234746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Attia RA, Tolba ME, Yones DA, et al. Capillaria philippinensis in Upper Egypt: has it become endemic? Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012;86(1):126–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Logan J, Pearson MS, Manda SS, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the secreted proteome of adult Necator americanus hookworms. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020; 14(5):e0008237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mourao Dias Magalhaes L, Silva Araujo Passos L, Toshio Fujiwara R, et al. Immunopathology and modulation induced by hookworms: from understanding to intervention. Parasite Immunol 2020;43(2):e12798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keller L, Patel C, Welsche S, et al. Performance of the Kato-Katz method and real time polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of soil-transmitted helminthiasis in the framework of a randomised controlled trial: treatment efficacy and day-to-day variation. Parasit Vectors 2020;13(1):517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riaz M, Aslam N, Zainab R, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, challenges, and the currently available diagnostic tools for the determination of helminth infections in humans. Eur J Inflamm 2020;18:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bundy DA, Cooper ES. Trichuris and trichuriasis in humans. Adv Parasitol 1989; 28:107–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen CC, Liu KW, Tai CM. An unexpected worm hanging over the cecum. Gastroenterology 2014;146(7):e7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nejsum P, Andersen KL, Andersen SD, et al. Mebendazole treatment persistently alters the size profile and morphology of Trichuris trichiura eggs. Acta Trop 2020; 204:105347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keller L, Palmeirim MS, Ame SM, et al. Efficacy and safety of ascending dosages of moxidectin and moxidectin-albendazole against trichuris trichiura in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2020;70(6):1193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sapulete EJJ, de Dwi Lingga Utama IMG, Sanjaya Putra IGN, et al. Efficacy of albendazole-pyrantel pamoate compared to albendazole alone for trichuris trichiura infection in children: a double blind randomised controlled trial. Malays J Med Sci 2020;27(3):67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Akinci O, Kepil N, Erzin YZ, et al. Enterobius vermicularis infestation mimicking rectal malignancy. Turkiye Parazitol Derg 2020;44(1):58–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taghipour A, Olfatifar M, Javanmard E, et al. The neglected role of Enterobius vermicularis in appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2020; 15(4):e0232143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wendt S, Trawinski H, Schubert S, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of pinworm infection. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2019;116(13):213–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsai CY, Junod R, Jacot-Guillarmod M, et al. Vaginal Enterobius vermicularis diagnosed on liquid-based cytology during Papanicolaou test cervical cancer screening: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol 2018;46(2):179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kondo T Woe sushi: gastric anisakiasis. Lancet 2018;392(10155):1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bernardo S, Castro-Pocas F. Gastric anisakiasis. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;88(4): 766–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hamada K, Uedo N, Tomita Y, et al. A bleeding gastric ulcer caused by anisakiasis. Ann Gastroenterol 2016;29(3):378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Panti-May JA, Rodriguez-Vivas RI, Garcia-Prieto L, et al. Worldwide overview of human infections with Hymenolepis diminuta. Parasitol Res 2020;119(7): 1997–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tanaka K, Hamada Y, Nakamura M, et al. Hymenolepis nana infection detected by magnifying colonoscopy with narrow-band imaging (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2017;86(5):923–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scholz T, Garcia HH, Kuchta R, et al. Update on the human broad tapeworm (genus diphyllobothrium), including clinical relevance. Clin Microbiol Rev 2009; 22(1):146–60. Table of Contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Friedman JF, Olveda RM, Mirochnick MH, et al. Praziquantel for the treatment of schistosomiasis during human pregnancy. Bull World Health Organ 2018;96(1): 59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Braae UC, Thomas LF, Robertson LJ, et al. Epidemiology of Taenia saginata taeniosis/cysticercosis: a systematic review of the distribution in the Americas. Parasit Vectors 2018;11(1):518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eichenberger RM, Thomas LF, Gabriel S, et al. Epidemiology of Taenia saginata taeniosis/cysticercosis: a systematic review of the distribution in East, Southeast and South Asia. Parasit Vectors 2020;13(1):234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eom KS, Rim HJ, Jeon HK. Taenia asiatica: historical overview of taeniasis and cysticercosis with molecular characterization. Adv Parasitol 2020;108:133–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nkouawa A, Sako Y, Okamoto M, et al. Simple identification of human taenia species by multiplex loop-mediated isothermal amplification in combination with dot enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2016;94(6):1318–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rodriguez S, Wilkins P, Dorny P. Immunological and molecular diagnosis of cysticercosis. Pathog Glob Health 2012;106(5):286–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.White AC Jr, Coyle CM, Rajshekhar V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of neurocysticercosis: 2017 clinical practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Am J Trop Med Hyg 2018;98(4):945–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Agudelo Higuita NI, Brunetti E, McCloskey C. Cystic echinococcosis. J Clin Microbiol 2016;54(3):518–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA, et al. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop 2010; 114(1):1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Siqueira LDP, Fontes DAF, Aguilera CSB, et al. Schistosomiasis: drugs used and treatment strategies. Acta Trop 2017;176:179–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Di Bella S, Riccardi N, Giacobbe DR, et al. History of schistosomiasis (bilharziasis) in humans: from Egyptian medical papyri to molecular biology on mummies. Pathog Glob Health 2018;112(5):268–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McManus DP, Dunne DW, Sacko M, et al. Schistosomiasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018;4(1):13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gray DJ, Ross AG, Li YS, et al. Diagnosis and management of schistosomiasis. BMJ 2011;342:d2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee TH, Huang CT, Chung CS. Education and imaging. Gastrointestinal: fasciolopsis buski infestation diagnosed by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;26(9):1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sah R, Khadka S, Hamal R, et al. Human echinostomiasis: a case report. BMC Res Notes 2018;11(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Behzad C, Lahmi F, Iranshahi M, et al. Finding of biliary fascioliasis by endoscopic ultrasonography in a patient with eosinophilic liver abscess. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2014;8(2):310–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hong ST, Fang Y. Clonorchis sinensis and clonorchiasis, an update. Parasitol Int 2012;61(1):17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sripa B, Brindley PJ, Mulvenna J, et al. The tumorigenic liver fluke Opisthorchis viverrini–multiple pathways to cancer. Trends Parasitol 2012;28(10):395–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Uskudar O, Parlak E. A swimmer in the bile duct. Diagnosis: Fasciola hepatica. Gastroenterology 2011;140(7):e3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Choi BI, Han JK, Hong ST, et al. Clonorchiasis and cholangiocarcinoma: etiologic relationship and imaging diagnosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004;17(3):540–52, table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Varyani F, Fleming JO, Maizels RM. Helminths in the gastrointestinal tract as modulators of immunity and pathology. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2017; 312(6):G537–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bach JF. The effect of infections on susceptibility to autoimmune and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med 2002;347(12):911–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yazdanbakhsh M, Kremsner PG, van RR. Allergy, parasites, and the hygiene hypothesis. Science 2002;296(5567):490–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Elliott DE, Weinstock JV. Nematodes and human therapeutic trials for inflammatory disease. Parasite Immunol 2017;39(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fleming JO, Weinstock JV. Clinical trials of helminth therapy in autoimmune diseases: rationale and findings. Parasite Immunol 2015;37(6):277–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Croese J, Giacomin P, Navarro S, et al. Experimental hookworm infection and gluten microchallenge promote tolerance in celiac disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135(2):508–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maizels RM, Smits HH, McSorley HJ. Modulation of host immunity by helminths: the expanding repertoire of parasite effector molecules. Immunity 2018;49(5): 801–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lee SC, Tang MS, Easton AV, et al. Linking the effects of helminth infection, diet and the gut microbiota with human whole-blood signatures. PLoS Pathog 2019; 15(12):e1008066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Martin I, Kaisar MMM, Wiria AE, et al. The effect of gut microbiome composition on human immune responses: an exploration of interference by helminth infections. Front Genet 2019;10:1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wu WH, Zegarra-Ruiz DF, Diehl GE. Intestinal microbes in autoimmune and inflammatory disease. Front Immunol 2020;11:597966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]