Abstract

Background

The early postpartum period is an important time in which to identify the risk of diabetes in women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). Oral glucose tolerance and other tests can help guide lifestyle management and monitoring to reduce the future risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Objectives

To assess whether reminder systems increase the uptake of testing for type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance in women with a history of GDM.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE and EMBASE (last searched 1 June 2013) and The Cochrane Library (last searched April 2013).

Selection criteria

We included randomised trials of women who had experienced GDM in the index pregnancy and who were then sent any modality of reminder (or control) to complete a test for type 2 diabetes after giving birth.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently screened titles and abstracts for relevance. One author extracted the data, carried out 'Risk of bias' assessments and evaluated the overall study quality according to GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) criteria; the other author double‐checked these procedures. Meta‐analysis was not possible as only one study was eligible for inclusion.

Main results

Only one trial with an unclear risk of bias in the majority of domains was included in the study; the overall study quality was judged to be low. This factorial trial of 256 women compared three types of postal reminder strategies (in a total of 213 women) with usual care (no postal reminder, 43 women) and reported on the uptake of four possible types of glucose tests. The three strategies investigated were: reminders sent to both the woman and the physician; reminder sent to the woman only; and reminder sent to the physician only, all issued approximately three months after the woman had given birth.

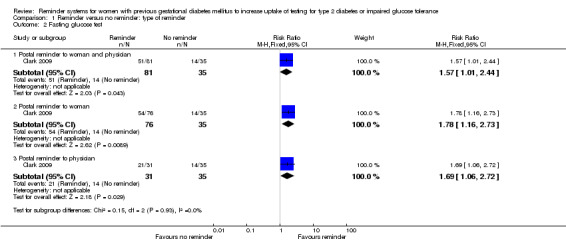

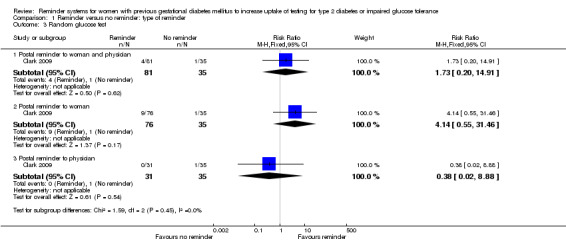

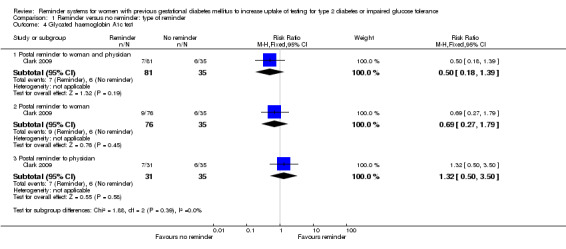

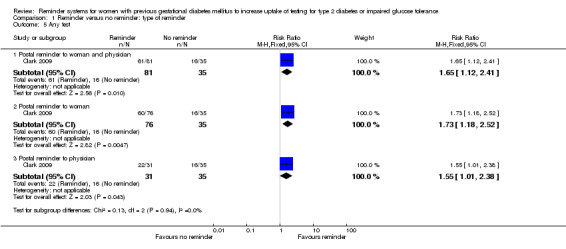

There was low‐quality evidence that all three reminder interventions increased uptake of oral glucose tolerance tests compared with usual care (no reminder system): reminders to the woman and the physician (uptake 60% versus 14%): risk ratio 4.23 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.85 to 9.71); 116 participants); reminder to the woman only (uptake 55% versus 14%): RR 3.87 (95% CI 1.68 to 8.93); 111 participants); reminder to the physician only (uptake 52% versus 14%): RR 3.61 (95% CI 1.50 to 8.71); 66 participants). This represented an increase in uptake from 14% in the no reminder group to 57% across the three reminder groups. There was also an increase in uptake of fasting glucose tests in the reminder group compared with the usual care group: reminders to the woman and the physician versus no reminder (uptake 63% versus 40%): RR 1.57 (95% CI 1.01 to 2.44); reminder to the woman only (uptake 71% versus 40%): RR 1.78 (95% CI 1.16 to 2.73); reminder to the physician only (uptake 68% versus 40%): RR 1.69 (95% CI 1.06 to 2.72). Uptake of random glucose and glycated haemoglobin A1c tests was low, and no statistically significant differences were seen between the reminder and no reminder groups for these tests. Uptake of any test was higher in each of the reminder groups compared with the no reminder group (RR 1.65 (95% CI 1.12 to 2.41); 1.73 (95% CI 1.18 to 2.52); and 1.55 (95% CI 1.01 to 2.38) in the respective reminder groups.

The trial did not report this review's other primary outcomes (proportion of women diagnosed with type 2 diabetes or showing impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose after giving birth; or health‐related quality of life). Nor did it report any secondary review outcomes such as diabetes‐associated morbidity, lifestyle changes, need for insulin, recurrence of GDM or women's and/or health professionals' views of the intervention. No adverse events of the intervention were reported.

Subgroup interaction tests gave no indication that dual reminders (to both women and physicians) were more successful than single reminders to either women or physicians alone. It was also not clear if test uptakes between women in the reminder and no reminder groups differed by type of glucose test undertaken.

Authors' conclusions

Results from the only trial that fulfilled our inclusion criteria showed low‐quality evidence for a marked increase in the uptake of testing for type 2 diabetes in women with previous GDM following the issue of postal reminders. The effects of other forms of reminder systems need to be assessed to see whether test uptake also increases when email and telephone reminders are deployed. We also need a better understanding of why some women fail to take opportunities to be screened postpartum. As the ultimate aim of increasing postpartum testing is to prevent the subsequent development of type 2 diabetes, it is important to determine whether increased test uptake rates also increase women's use of preventive strategies such as lifestyle modifications.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Diabetes, Gestational; Reminder Systems; Correspondence as Topic; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2/diagnosis; Glucose Intolerance; Glucose Intolerance/diagnosis; Glucose Tolerance Test; Glucose Tolerance Test/statistics & numerical data; Postpartum Period; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Reminder systems for women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus to increase uptake of testing for type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance

Review question

To assess the effects of reminder systems to increase uptake of testing for type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance in women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

Background

Some women experience high blood glucose concentrations during pregnancy (termed GDM). Although these high blood glucose concentrations usually normalise immediately after birth, women who have experienced GDM are at an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes in the future. It is therefore important that they are regularly tested for higher than normal blood glucose levels (to detect type 2 diabetes or 'impaired glucose tolerance' which is a prediabetic state sometimes preceding type 2 diabetes), starting in the months after they have given birth. However, for a variety of reasons, many women do not get their blood glucose tested after experiencing GDM.

Study characteristics

A single study of 256 women who had experienced GDM whether posting reminder letters to 213 women or their doctors, three months after the birth of a baby, would help to increase the number of women taking a blood glucose test compared with 43 women sent no reminder.

Key results

This study showed that, compared with no reminder, a postal reminder was around two to four times (depending on the blood glucose test concerned) more likely to encourage women who had experienced GDM to take a blood glucose test three months after having their baby. It did not seem to make a difference if the reminder was sent to the woman only, the physician only or to both the woman and the physician.

The trial did not assess women's quality of life, or how many women were subsequently diagnosed with type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose results after giving birth.

Other kinds of reminders such as email and telephone need to be assessed in studies as they might be easier and more convenient for women than posted reminders. We need to know more about women's preferences and attitudes, and also to find out whether increasing the chances of a woman being tested helps to reduce her risk of developing type 2 diabetes in the future, for example by encouraging a healthier diet and more exercise.

Quality of the evidence

The overall quality of evidence was considered low as the only included study involved few numbers of participants and provided imprecise results.

Currentness of data

This evidence is up to date as of June 2013.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Reminder systems for women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus to increase uptake of testing for type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance | ||||||

|

Population: women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus Settings: university‐affiliated tertiary centre Intervention: postal reminders for women or physicians, or both Comparison: no reminder (usual care) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies)a | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Reminders | No reminders | |||||

|

Proportion of women having their first OGTT after giving birth a) Postal reminder to woman and physician b) Postal reminder to woman c) Postal reminder to physician Follow‐up: up to 1 year |

a)143 per 1000 b) 143 per 1000 c) 143 per 1000 |

a) 604 per 1000

(264 to 1387) b) 553 per 1000 (240 to 1276) c) 516 per 1000 (214 to 1244) |

a) RR 4.23 (1.85 to 9.71) b) RR 3.87 (1.68 to 8.93) c) RR 3.61 (1.50 to 8.71) |

a) 116 (1) b) 111 (1) c) 66 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb | ‐ |

|

Proportion of women having a blood glucose test other than an OGTT after giving birth: fasting blood glucose a) Postal reminder to woman and physician b) Postal reminder to woman c) Postal reminder to physician Follow‐up: up to 1 year |

a) 400 per 1000 b) 400 per 1000 c) 400 per 1000 |

a) 628 per 1000 (404 to 976)

b) 712 per 1000 (464 to 1092) c) 676 per 1000 (424 to 1088) |

a) RR 1.57 (1.01 to 2.44) b) RR 1.78 (1.16 to 2.73) c) RR 1.69 (1.06 to 2.72) |

a) 116 (1) b) 111 (1) c) 66 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb | ‐ |

| Proportion of women diagnosed with type 2 diabetes or showing impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose after giving birth | See comment | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated | |

| Health‐related quality of life | See comment | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated | |

| Diabetes‐associated morbidity | See comment | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated | |

| Costs or other measures of resource use | See comment | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in the footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OGTT: oral glucose tolerance test; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

The basis for the assumed risk is the number of events in the comparator groups

aNumber of participants: the same control group (no reminder) data were used for comparison with the three intervention groups in the four‐arm study bDowngraded by two levels owing to few participants and one included study only, with unclear risk of bias in most domains, and imprecise results (wide confidence intervals)

Background

Description of the condition

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder resulting from a defect in insulin secretion, insulin action or both. A consequence of this is chronic hyperglycaemia (i.e. elevated levels of plasma glucose) with disturbances in carbohydrate, fat and protein metabolism. Long‐term complications of diabetes mellitus include retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy. The risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer is increased.

Being pregnant is a state that creates a degree of metabolic stress, which can include an increase in insulin resistance (Ratner 2007). For some women this results in glucose concentrations high enough for a diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) to be made. Although these high glucose concentrations usually normalise immediately after birth, women who have experienced GDM are at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes in the future (Conway 1999; Hunt 2008; Retnakaran 2008; Retnakaran 2011; Schaefer‐Graf 2002). Both GDM and type 2 diabetes share the two main metabolic defects of insulin resistance and ß‐cell dysfunction (Retnakaran 2008). In fact GDM could be regarded as "type 2 diabetes unmasked by pregnancy" (Bottalico 2007).

Approximately 7% of pregnancies in the USA are complicated by GDM (Nicholson 2008), partly due to increasing rates of obesity (Kim 2010). In Australia, the prevalence of GDM is 5% (AIHW 2010).

It is important to note that the prevalence of GDM is influenced by methods of detection and diagnosis, which differ across the world (ACOG 2013; ADA 2013; Hoffman 1998). For example, following the recent Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes (HAPO) study (HAPO 2008), the recommendation to lower the diagnostic threshold for GDM will result in 18% of pregnant women being diagnosed with this condition (Metzger 2010), nearly trebling the yield of many current methods of diagnosing GDM. Because of variations in diagnostic thresholds, a standard set of diagnostic criteria cannot yet be applied for identifying women with GDM.

Women who have experienced GDM are over seven times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes than women with normal glycaemic concentrations in pregnancy (Bellamy 2009). Cumulative incidence rates of type 2 diabetes range from 30% to 62% in the first five years after giving birth in a woman with previous GDM, and appear to plateau after 10 years (Kim 2002).

The risk of developing type 2 diabetes is proportional to the degree of hyperglycaemia during pregnancy (Retnakaran 2008), with factors such as impaired glucose tolerance, needing insulin to manage GDM, prepregnancy obesity, high‐density lipoprotein‐cholesterol levels less than 50 mg/dL and age older than 35 years all being predictors of diabetes after GDM (Göbl 2011; Nicholson 2008). The International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group has recently described a new category of "overt diabetes in pregnancy", in women with high results for glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), fasting glucose or oral glucose tolerance tests in early pregnancy ‐ although this condition cannot be equated with underlying diabetes. A retrospective audit of women with overt diabetes in pregnancy has shown 21% to have type 2 diabetes and 38% to have impaired fasting glucose/impaired glucose tolerance in the early postpartum period (Wong 2013).

In addition to the increased risk of later type 2 diabetes, women diagnosed with GDM are also at increased risk of recurrent GDM in subsequent pregnancies. Rates of recurrence of GDM range from 30% to 84%, with some of these cases likely to be unrecognised (pregestational) type 2 diabetes (Bottalico 2007; Getahun 2010; Kim 2007).

Description of the intervention

Many international professional and government clinical practice guidelines or consensus statements recommend that women who had GDM in their most recent pregnancy receive an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) between 6 to 12 weeks postpartum to detect type 2 diabetes (ACOG 2013; Metzger 2007; RANZCOG 2011; Simmons 2002). Because of the high risk of future diabetes, these women are often advised to undergo retesting on a regular basis (Metzger 2007; Metzger 2010; NICE 2008; RANZCOG 2011; Simmons 2002).

There is a large gap between these recommendations for postpartum testing and practice. Even though a history of GDM provides a natural prompt to commence screening for type 2 diabetes (Bellamy 2009), most women are not tested. Reported rates of testing vary from 5% to 60%, with probably only 20% to 40% of women with previous GDM having some form of postpartum glucose test (Clark 2009; Conway 1999). In a large US study of nearly one million pregnant women using commercial diagnostic services, 19% (4486/23,299 women diagnosed with GDM) had a postpartum diabetes test within six months of giving birth. However, in this study overall uptake would have been somewhat less than 19% as only two‐thirds of the pregnant women in the study were screened for GDM (Blatt 2011).

Reasons given for not having a postpartum OGTT include: a perception that GDM resolves completely after pregnancy; the emotional stress and time demands of a new baby; the inconvenience of the test; fear of receiving a diagnosis of diabetes; and lack of continuity of postpartum care (Bennett 2011; Hunt 2008; Keely 2010).

Reminder systems have been shown to be effective in many areas of health care, including diabetes (Weingarten 2002). In a systematic review of 54 studies addressing postpartum testing rates among women with a history of GDM, studies of proactive contact with women nearly doubled the testing rates reported in studies of usual care (from an average of 33% to 60%). Proactive contact in this review included phone calls, education programmes and postal reminders (Carson 2013).

Although not conducted specifically in pregnant or postpartum women with diabetes or a history of diabetes, other systematic reviews have demonstrated that clinician reminders can modestly increase rates of preventative care (Dexheimer 2008) and healthcare performance in general (Grimshaw 2006). Thus, reminder systems for women or health professionals (or both) may increase the uptake of postpartum glucose tests. Preventative care reminders have usually been in the form of mailed letters or direct phone calls, with email and mobile phone (SMS (short message service)) messaging now beginning to be used and to show some benefits (Car 2012).

A voluntary national gestational diabetes register, recently established in Australia (http://www.ndss.com.au), is issuing annual reminders to women who have experienced GDM and joined the scheme. An evaluation of its predecessor, the South Australian Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Recall Register, indicates the future potential of registration and follow‐up reminders to increase the uptake of glucose tests and therefore the early detection of type 2 diabetes (Chittleborough 2010).

Adverse effects of the intervention

While a reminder intervention is not envisaged to lead to adverse effects, there is the possibility that reminders may be regarded as intrusive by some people and may even be a source of anxiety.

How the intervention might work

The purpose of postpartum screening of women with previous GDM is to promptly identify those women who will subsequently develop type 2 diabetes. Early identification allows earlier management through preventative strategies such as diet modification, exercise and avoiding excessive weight gain (Nield 2008; Norris 2005; Orozco 2008). Sometimes oral glucose‐lowering drugs or insulin may be added to such lifestyle changes. In a subgroup analysis of the Diabetes Prevention Program, both intensive lifestyle interventions and metformin were effective in delaying or preventing diabetes in women with impaired glucose tolerance and a history of GDM (Ratner 2008).

However, the beneficial effects of these preventive measures will not be realised unless women with previous GDM are screened postpartum, are offered appropriate management and follow up, and then agree to make lifestyle changes. Clinicians and women regard reminder systems for postpartum type 2 diabetes screening as important and useful (Keely 2010), and so reminders are likely to be able to address some of the awareness and behavioural barriers that women face when making lifestyle changes after giving birth, leading to women with a history of GDM being able to avoid a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in the future.

Why it is important to do this review

The incidence of GDM indicates the underlying frequency of type 2 diabetes, with both types of diabetes rising throughout the world (Bellamy 2009).

The early postpartum period is an important time in which to identify the risk of diabetes in women with a history of GDM or milder glucose intolerance in pregnancy (Retnakaran 2008) and to translate postpartum testing into practice (Oza‐Frank 2013). In fact, some researchers posit that prevention of subsequent type 2 diabetes may be the most compelling reason to diagnose GDM (Keely 2012a). For a majority of women with a history of GDM, the opportunity to prevent subsequent type 2 diabetes is currently missed, as is the chance to detect any problems and intervene to prevent future diabetic complications such as cardiovascular disease (Kitzmiller 2007; Shah 2008) and future metabolic dysfunction (Stuebe 2011), and also the chance to reduce the risk of diabetes in their children (Clausen 2008; Dabelea 2011).

Early detection may also reduce healthcare costs ‐ in a Swedish longitudinal study, women diagnosed with diabetes after GDM had a more than 14‐fold likelihood of healthcare utilisation, with an annual healthcare cost 101% higher than in controls (Anderberg 2012).

This review evaluates the effects of reminder strategies to identify all possible women with previous GDM, follow them up, and offer them appropriate management and treatment. A Cochrane review assessing the effects of interventions to prevent type 2 diabetes in women with previous GDM is currently being prepared (Wendland 2011).

Objectives

To assess the effects of reminder systems to increase uptake of testing for type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance in women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled clinical trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

Women with a diagnosis of GDM in the index pregnancy.

Diagnostic criteria

To be consistent with changes in classification and diagnostic criteria for diabetes mellitus through the years, a diagnosis of GDM had to be established using the standard criteria valid at the start of the trial (e.g. ADA 1999; ADA 2008; WHO 1998). Participants in the single included trial were women who had been treated for GDM ‐ no further details were given. In future versions of the review, we plan to subject diagnostic criteria to a sensitivity analysis.

Types of interventions

Intervention

Reminders of any modality (post, email, phone (direct call or short SMS text) to either women with a history of GDM or their health professional, or both.

Control

A different kind of reminder.

No reminder.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Proportion of women having their first OGTT (> 6 weeks to ≤ 6 months, > 6 months to ≤ 12 months, > 12 months) after giving birth.

Proportion of women having a blood glucose test other than an OGTT (> 6 weeks to ≤ 6 months, > 6 months to ≤ 12 months, > 12 months) after giving birth.

Proportion of women diagnosed with type 2 diabetes or showing impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose after giving birth.

Health‐related quality of life.

Secondary outcomes

Diabetes‐associated morbidity.

Death from any cause.

Adverse events.

Blood glucose concentrations.

HbA1c levels.

Appropriate referral or management, or both.

GDM recurrence in the next or any subsequent pregnancy.

Depression or depressive symptoms, anxiety, distress (as reported by authors).

Self‐reported lifestyle changes (e.g. increase in exercise or physical activity, dietary modification, weight loss strategies).

Body mass index (BMI) or body weight.

Need for insulin or other glucose‐lowering medications after giving birth.

Breastfeeding.

Women's views of the intervention.

Health professionals' views of the intervention.

Costs or other measures of resource use.

Timing of outcome measurement

We specified short‐term endpoints to be those measured between 6 weeks and 6 months after giving birth; medium‐term between more than 6 months and 12 months after giving birth; and long‐term more than 12 months after giving birth.

'Summary of findings' table

We present a 'Table 1' reporting the following outcomes listed according to priority.

Proportion of women having their first OGTT after giving birth.

Proportion of women having a blood glucose test other than an OGTT after giving birth.

Proportion of women diagnosed with type 2 diabetes or showing impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose after giving birth.

Health‐related quality of life.

Diabetes‐associated morbidity.

Costs or other measures of resource use.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following sources from inception to the specified date.

The Cochrane Library (April 2013).

MEDLINE (until 1 June 2013).

EMBASE (until 1 June 2013).

We also searched databases of ongoing trials (metaRegister of Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com/mrct/) and the EU Clinical Trials register (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/)). We have provided information, including trial identifier, about identified studies in the 'Characteristics of ongoing studies' table and the appendix 'matrix of study endpoints (trial documents)'.

For detailed search strategies, please see Appendix 1. We used PubMed's 'My NCBI' (National Center for Biotechnology Information) email alert service for the identification of newly published studies using a basic search strategy (see Appendix 1).

In future, if additional key words of relevance are detected during any of the electronic or other searches we will modify the electronic search strategies to incorporate these terms. We will include studies published in any language.

If we carry out additional searches, we will send the electronic search results to the Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group to be included in databases that are not available at the editorial office.

Searching other resources

We attempted to identify additional studies by searching the reference lists of included trials and relevant reviews.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

To identify studies to be assessed further, two review authors (PM, CAC) independently scanned the abstract, title or both sections of every record retrieved.

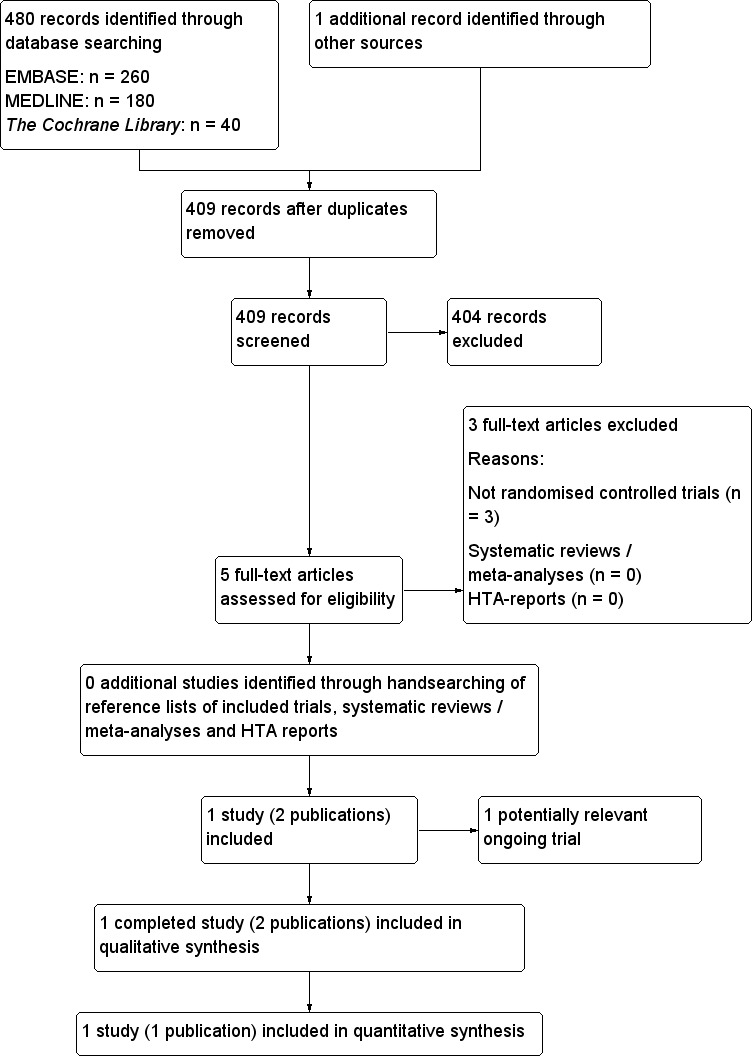

All potentially relevant articles were investigated as full text. No differences in opinion regarding study inclusion occurred at this stage. A PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses) flow‐chart of study selection is provided (Figure 1) (Liberati 2009).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

For studies fulfilling inclusion criteria, two review authors (PM, CAC) independently abstracted relevant population and intervention characteristics using standard data extraction templates (for details, see Table 2; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; and Appendix 6), with disagreements resolved by discussion. We sent an email request to the contact person of the single included study (Appendix 7) but no reply has been received to date.

1. Overview of study populations.

| Characteristic | Intervention(s) and comparator(s) | Sample sizea | Screened/eligible [N] | Randomised [N] | Finishing study [N] | Randomised finishing study [%] | Follow‐up timeb |

| Clark 2009 | I1: physician/woman reminder | 220 (2:1 randomisation for the women interventions vs the physician intervention) ClinicalTrials.gov information: 67 women in each group, total sample size of the study would be 268 women |

490 | 88 | 81 | 92 | Up to 12 months (postal reminders were sent 3 months after eligible women had given birth) |

| I2: woman‐only reminder | 84 | 76 | 90 | ||||

| I3: physician‐only reminder | 41 | 31 | 76 | ||||

| C: no reminders | 43 | 35 | 81 | ||||

| total: | 256 | 223 | 87 | ||||

| Total | All interventions | 213 | 188 | 88 | |||

| All controls | 43 | 35 | 81 | ||||

| All interventions and controls | 256 | 223 | 87 | ||||

aAccording to power calculation in study publication or report

bDuration of intervention and/or follow‐up under randomised conditions until end of study

Dealing with duplicate publications

In the case of duplicate publications and companion papers of a primary study, we have tried to maximise yield of information by the simultaneous evaluation of all available data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (PM, CAC) assessed the single trial independently. There were no disagreements, but in future updates of the review we will resolve possible disagreements by consensus, or in consultation with a third party.

We assessed risk of bias using The Cochrane Collaboration's tool (Higgins 2011a; Higgins 2011b). We used the following criteria.

Random sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding (performance bias and detection bias), separated for blinding of participants and personnel, and blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting (reporting bias) ‐ see Appendix 5.

Other bias.

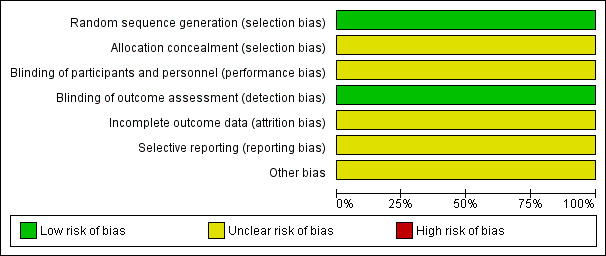

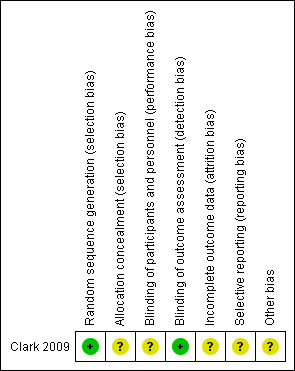

We judged risk of bias criteria as 'low risk', 'high risk' or 'unclear risk', and evaluated individual bias items as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We have included a 'Risk of bias' graph (Figure 2) and a 'Risk of bias summary' figure (Figure 3).

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

We assessed the impact of individual bias domains on study results at endpoint and study levels.

For blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessors) and attrition bias (incomplete outcome data) we intend, in the future, to evaluate risk of bias separately for subjective and objective outcomes. In the single trial included in this version of the review, we considered all of the trial's reported outcomes to be objective, namely the proportion of women undergoing an OGTT after giving birth (primary outcome) and the performance of other postpartum screening tests, singly or as any combination of tests (primary outcomes).

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data are expressed as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Continuous data will be expressed as differences in means (MDs) with 95% CIs, if reported in trials included in future versions of this review.

Unit of analysis issues

If relevant trials are included in future versions of the review, we will take into account the level at which randomisation occurred, such as cross‐over trials, cluster‐randomised trials and multiple observations for the same outcome.

Dealing with missing data

We investigated attrition rates (e.g. drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals) and critically appraised issues of missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned not to report study results as meta‐analytically pooled effect estimates when there was substantial clinical, methodological or statistical heterogeneity.

We planned to identify heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plots and by using a standard Chi2 test with a significance level of α = 0.1, in view of the low power of this test. We will examine heterogeneity specifically, employing the I2 statistic, which quantifies inconsistency across studies, to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003), where an I2 statistic of 75% or greater indicates a considerable level of inconsistency (Higgins 2011a).

If heterogeneity is found, we plan to determine potential reasons for it by examining individual study and subgroup characteristics.

We expect the following characteristics to introduce clinical heterogeneity.

Severity of GDM (e.g. insulin required during index pregnancy).

Type of test ‐ OGTT or other glucose test.

Result of glucose test(s) ‐ normal/abnormal; high or low results if abnormal.

Thresholds used in glucose tests for defining normal and abnormal.

Parity.

Maternal age.

Maternal BMI.

Reasons for not having a glucose test.

Modality of reminder.

Who was reminded (clinician or woman, or both).

In this version of the review, we were able to explore, to a limited extent, the effects of the factors type of test and who was reminded (see the Results section).

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates we will use funnel plots when 10 or more studies are included for a given outcome, in order to assess small study effects. Owing to several possible explanations for funnel plot asymmetry we will interpret results carefully (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

We planned to use a random‐effects model. In future updates, unless there is good evidence for homogeneous effects across studies, we will primarily summarise data at low risk of bias by means of a random‐effects model (Wood 2008). We will interpret random‐effects meta‐analyses with due consideration of the whole distribution of effects, ideally by presenting a prediction interval. A prediction interval specifies a predicted range for the true treatment effect in an individual study (Riley 2011). In addition, we will perform statistical analyses according to the statistical guidelines referenced in the latest version of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to carry out subgroup analyses of the primary outcome parameter(s) (see above) and to investigate interaction, but there were insufficient data to enable us to do this.

The following subgroup analyses are planned for future updates.

Severity of GDM in index pregnancy (need for insulin or other diabetes medication).

Maternal age (> 35 years versus ≤ 35 years).

Maternal BMI (normal, overweight or obese) ‐ either prepregnancy or after giving birth.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses in order to explore the influence of the following factors on effect sizes.

Restricting the analysis to published studies.

Restricting the analysis by taking into account risk of bias, as specified in the section Assessment of risk of bias in included studies.

Restricting the analysis to very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results.

Restricting the analysis to studies using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), country.

We planned also to test the robustness of the results by repeating the analysis using different measures of effect size (RR, odds ratio etc.) and different statistical models (fixed‐effect and random‐effects models).

However, as only one study met the inclusion criteria, it was not possible to conduct any sensitivity analyses.

Results

Description of studies

For a detailed description of studies, see the Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Results of the search

The initial search identified 481 records (see Figure 1 for the amended PRISMA flow chart); from these, five full text papers were identified for further examination. We excluded the other studies on the basis of their titles or abstracts because they did not meet the inclusion criteria or were not relevant to the question under study or were a duplicate report. After screening the full text of the selected publications, one study (two publications) met the inclusion criteria (Clark 2009).

Included studies

A detailed description of the characteristics of the included study is presented in the Characteristics of included studies table and in Appendix 2, Appendix 3, Appendix 4, Appendix 5 and Appendix 6.

Comparisons

This was a factorial trial of physician and woman pairs; there were four groups (physician/woman reminders; physician‐only reminder; woman‐only reminder; and no reminder).

Overview of study populations

A total of 256 women (and their family physician) were included in the trial. In this trial, 88 women were randomised to the woman/physician reminder group, 41 to the physician‐only reminder group; 84 to the woman‐only reminder group and 43 to the usual care (no reminder) group. Results were available for 223 (87%) of the 256 women.

Study design

The RCT was single‐centred, and women and their physicians were recruited between 2002 and 2005.

Due to the nature of the intervention (postal reminders), blinding was not feasible.

Settings

The RCT was conducted in a Canadian university hospital setting.

Participants

Most women were aged 30 years or more (78%). Over half (52%) had a family history of type 2 diabetes and 14% of women had been diagnosed with GDM in a previous pregnancy. Over half (62%) required insulin treatment for their current GDM.

BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 at baseline ranged from 24% in the women‐only reminder group to 46% in the no‐reminder group.

Criteria for inclusion in the study are outlined in the Characteristics of included studies table. A major exclusion criterion was loss of contact with the woman or physician.

Diagnosis

Clark 2009 did not report the diagnostic criteria used to determine GDM ‐ women eligible for the study were those treated for GDM.

Interventions

Three months after eligible women had given birth, postal reminders were sent to the woman only, to the physician only, and to both the woman and physician. No reminders were sent to women in the control group.

Women and physicians were contacted three times during the one‐year post‐study survey follow‐up: women were contacted by telephone twice and by mail once, and physicians were contacted by fax, telephone and mail.

The duration of follow‐up was up to one year after giving birth.

Outcomes

The single included study reported only the proportion of tests completed within one year of giving birth. The prespecified primary outcome was the proportion of women who underwent an OGTT within one year of giving birth.

Secondary outcomes were the performance of other postpartum screening tests (venous fasting glucose, venous random glucose, HbA1c or any combination of these).

Excluded studies

Three studies were excluded after careful evaluation of the full publication (Lega 2012; Shea 2011; Vesco 2012) ‐ see Figure 1.

Reasons for exclusion were that each of the three studies, although addressing the topic of the review, were not randomised studies. For further details, see Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

For details on risk of bias in the included study, see the Characteristics of included studies table.

For an overview of review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item in the included study (Clark 2009), see Figure 2 and Figure 3.

We judged the primary outcome and the four secondary outcomes reported by Clark 2009 to be objective outcomes.

Allocation

We judged the method of sequence generation used in the one included study to be adequate. However, details about allocation concealment were unclear and to date we have not received a response from the study contact author providing further clarification.

Blinding

Although it would not have been feasible to blind participants and personnel to the reminder interventions, objective outcomes such as glucose test results may not have been unduly influenced by knowledge of group allocation. Nevertheless, we made a conservative judgement that there was an unclear risk of performance bias in the included study.

Incomplete outcome data

The single included study (Clark 2009) reported only objective outcomes.

Overall 33/256 (13%) of participants were lost to follow‐up. The attrition rate was higher (more than double) in the two groups of women not sent a reminder than in the two groups of women who were sent a reminder.

The authors reported that they conducted two analyses, one assuming that all women lost to follow‐up were screened and the other that they were not screened, stating "results were unchanged".

Due to the fairly high losses and the differential loss rates between groups, we judged the risk of attrition bias to be unclear.

Selective reporting

We rated selective reporting bias as unclear. Although most expected outcomes were reported, women's or physicians' views, morbidity or resource use were not reported.

Other potential sources of bias

Due to some evidence of baseline imbalance, we judged this component to be at an unclear risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Baseline characteristics

For details of baseline characteristics, see Appendix 3 and Appendix 4.

Primary outcomes

Proportion of women who underwent an OGTT within one year of giving birth

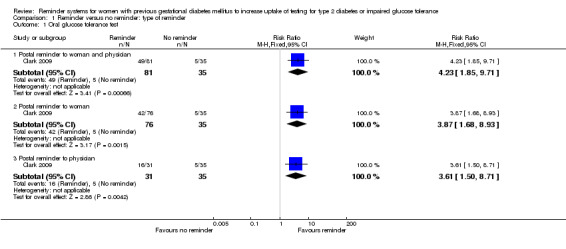

In a single trial (with an overall unclear risk of bias) of 256 women, all three reminder interventions were more effective than usual care (no reminder system) in terms of women undertaking an OGTT approximately three months after giving birth. RRs for each comparison were as follows (Analysis 1.1) (percentages indicate rate of uptake in each group).

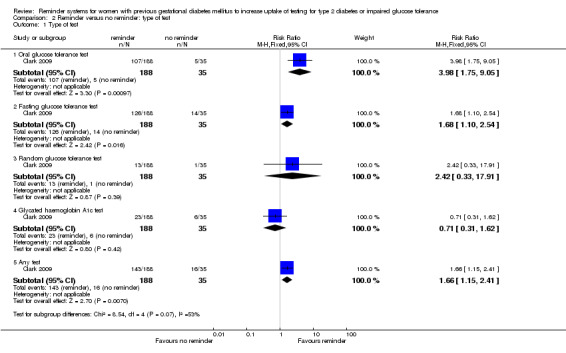

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Reminder versus no reminder: type of reminder, Outcome 1 Oral glucose tolerance test.

Postal reminder sent to both woman and physician (60%) versus usual care (14%): RR 4.23 (95% CI 1.85 to 9.71).

Postal reminder sent to woman only (55%) versus usual care (14%): RR 3.87 (95% CI 1.68 to 8.93).

Postal reminder sent to physician only (52%) versus usual care (14%): RR 3.61 (95% CI 1.50 to 8.71).

Rates of test uptake did not differ substantially between the three interventions, as indicated by the non‐significant subgroup differences test (Chi2 = 0.07; P value = 0.97, I2 = 0%).

Proportion of women having a blood glucose test other than an OGTT after giving birth

Fasting glucose test

In line with the OGTT findings above, women in all three reminder groups were more likely than those receiving no reminder to undergo a fasting glucose test approximately three months after giving birth (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Reminder versus no reminder: type of reminder, Outcome 2 Fasting glucose test.

Postal reminder sent to both woman and physician (63%) versus usual care (40%): RR 1.57 (95% CI 1.01 to 2.44).

Postal reminder sent to woman only (71%) versus usual care (40%): RR 1.78 (95% CI 1.16 to 2.73).

Postal reminder sent to physician only (68%) versus usual care (40%): RR 1.69 (95% CI 1.06 to 2.72).

Rates of test uptake did not differ substantially between the three interventions, as indicated by the non‐significant subgroup differences test (Chi2 = 0.15; P value = 0.45, I2 = 0%).

Random glucose test

No significant differences in uptake rates were seen for random glucose testing approximately three months after women had given birth (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Reminder versus no reminder: type of reminder, Outcome 3 Random glucose test.

Postal reminder sent to both woman and physician (5%) versus usual care (3%): RR 1.73 (95% CI 0.20 to 14.91).

Postal reminder sent to woman only (12%) versus usual care (3%): RR 4.14 (95% CI 0.55 to 31.46).

Postal reminder sent to physician only (0%) versus usual care (3%): RR 0.38 (95% CI 0.02 to 8.88).

The subgroup interaction test was not significant (Chi² = 1.59; P value = 0.45, I² = 0%).

Glycated haemoglobin A1c test

No significant differences in uptake rates were seen for HbA1c testing approximately three months after women had given birth (Analysis 1.4):

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Reminder versus no reminder: type of reminder, Outcome 4 Glycated haemoglobin A1c test.

Postal reminder sent to both woman and physician (9%) versus usual care (17%): RR 0.50 (95% CI 0.18 to 1.39).

Postal reminder sent to woman only (12%) versus usual care (17%): RR 0.69 (95% CI 0.27 to 1.79).

Postal reminder sent to physician only (23%) versus usual care (17%): RR 1.32 (95% CI 0.50 to 3.50).

The subgroup interaction test was not significant (Chi² = 1.88; P value = 0.39, I² = 0%).

Any test

When assessed as any of the above tests undertaken by women three months after giving birth, all three intervention groups were significantly more effective with regard to test uptake than the control (no reminder) group (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Reminder versus no reminder: type of reminder, Outcome 5 Any test.

Postal reminder sent to both woman and physician (75%) versus usual care (46%): RR 1.65 (95% CI 1.12 to 2.41).

Postal reminder sent to woman only (79%) versus usual care (46%): RR 1.73 (95% CI 1.18 to 2.52).

Postal reminder sent to physician only (71%) versus usual care (46%): RR 1.55 95% (CI 1.01 to 2.38).

The subgroup interaction test was not significant (Chi² = 0.13; P value = 0.94, I² = 0%).

Proportion of women diagnosed with type 2 diabetes or showing impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose after giving birth

Not investigated.

Health‐related quality of life

Not investigated.

Secondary outcomes

None of our predefined secondary outcomes ‐ diabetes‐associated morbidity; death from any cause; adverse events; blood glucose concentrations; HbA1c levels; appropriate referral and/or management; GDM recurrence in the next or any subsequent pregnancy; depression or depressive symptoms, anxiety, distress; self‐reported lifestyle changes; BMI or body weight; need for insulin or other glucose‐lowering medications after giving birth; breastfeeding; women's views of the intervention; health professionals' views of the intervention; and costs or other measures of resource use ‐ were investigated in the included study.

Subgroup analyses

By type of reminder ‐ see above.

By type of test ‐ no clear differences were seen between the various types of tests of glucose status ‐ Analysis 2.1, with a non‐significant subgroup interaction test (Chi2 = 8.54; P value = 0.07, I2 = 53%).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Reminder versus no reminder: type of test, Outcome 1 Type of test.

Sensitivity analyses

As only one study was included in the review, no sensitivity analyses were conducted.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Only one completed trial, with an unclear risk of bias, that fulfilled the inclusion criteria was identified (Clark 2009), and thus the overall quality of the evidence was judged to be low (Table 1). This RCT found all three reminder interventions to be significantly more effective than usual care (no reminder system), in terms of women with a history of GDM undertaking an OGTT three months after giving birth. Whether reminders were sent just to the physician or to the woman, or to both, the likelihood of test completion was three‐to‐four‐fold higher than if no reminders were sent. For example, the dual reminder intervention resulted in 60% of women completing their OGTT compared with 14% in the no reminder group. Significantly more women in the reminder groups (compared with no reminder) also completed a fasting glucose test, although the respective intervention and control rates were more comparable with each other ‐ approximately 67% and 40%.

Reminders had very little impact on the uptake of random glucose and HbA1c tests, with a low uptake of either test in intervention and control groups.

Subgroup interaction tests gave no indication that dual reminders (sent to both women and physicians) were more successful than single reminders sent either to women or physicians alone. It was also not clear wether the rate of test uptake between women in the reminder and no reminder groups differed by type of glucose test undertaken.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The evidence base is very incomplete, with one relatively small RCT only identified to date as addressing the question posed by this review. This RCT reported only the uptake of various glucose tests (our other prespecified outcomes were not investigated) and utilised only postal reminders.

In a later paper from the authors of the included RCT (Clark 2012), the need for other reminder methods such as SMS was emphasised and, in a subsequent survey administered to 51 women with GDM, the authors of this RCT found that most women with GDM said they wished to receive a reminder as a voice message on their home (Iandline) phone; a majority (73%) wanted their primary care physician to receive a reminder (Keely 2012b).

As the ultimate aim of increasing postpartum testing is to identify women at risk and to prevent the subsequent development of type 2 diabetes, it is important to test preventive interventions such as lifestyle changes, ideally in RCTs. These interventions and any subsequent implementation require careful design as there are many barriers that women with previous GDM face when making lifestyle changes after giving birth, even when they are aware of their increased future risk of type 2 diabetes (Lie 2013).

Numbers of women diagnosed with GDM are likely to continue to increase due both to demographic changes (older mothers, increasing rates of obesity) as well as the proposed diagnostic threshold changes (Metzger 2010).

Quality of the evidence

We assessed most of the 'Risk of bias' components to be unclear and, consequently, we have some reservations about the findings from the single included trial. The overall quality of evidence was judged to be low due to the imprecision of the results (i.e. wide CIs) (Table 1).

Potential biases in the review process

Although a comprehensive search was undertaken, there may be relevant unpublished studies or grey literature that we did not find.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Although we did not identify any other completed RCTs assessing the effect of reminders in improving the uptake of glucose tests after birth in women with a history of GDM, one RCT, testing whether SMS reminders can increase test uptakes in such women, is underway (Heatley 2013).

A number of cohort studies and reviews have found lower than optimal test uptake, in line with the findings of Clark 2009. A review by Tovar 2011 reported that 34% to 73% of women with a history of GDM completed postpartum glucose screening. In the Carson 2013 review, programmes where women with a history GDM were proactively contacted showed an increase of about one‐third in postpartum glucose testing compared with usual care. A later study, not included in Carson 2013, compared telephone nurse management programmes and found that postpartum glucose testing was increased over 20‐fold when referral proportions in centres were high (over 70%) (Ferrara 2012).

Other follow‐up studies from Clark and colleagues show an initial increase in postpartum diabetes screening after the Clark 2009 RCT (Vesco 2012), and Shea 2011 reported a higher likelihood of having an OGTT if a postal or phone reminder had been sent as routine practice (although at 28% for reminders and 14% for no reminders, test uptake was much lower in actual practice than in the Clark 2009 RCT).

While the OGTT is considered to be the most accurate screening test for postpartum diabetes (ADA 2013), other tests, such as fasting glucose and HbA1c, may be less burdensome for women, and have acceptable performance when timed appropriately (Kim 2011).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

While only one trial fulfilled our inclusion criteria and the overall quality of evidence was low, it showed that postal reminders increased the uptake of testing for type 2 diabetes in women with previous gestational diabetes (GDM). Other forms of reminder systems (e.g. email and telephone reminders) could potentially be effective, although our review was not able to compare these approaches due to lack of studies. The number of women diagnosed with GDM is projected to rise due to expected increases in BMI and maternal age, as well as possible changes to diagnostic thresholds, so healthcare systems will require effective postpartum reminder and diabetes screening programmes.

Implications for research.

The effects of other forms of reminder systems need to be assessed to see whether test uptake is also increased when email and telephone reminders are deployed. We also need a better understanding of why some women fail to take opportunities to be screened postpartum. As the ultimate aim of increasing postpartum testing is to prevent the subsequent development of type 2 diabetes, it is important to determine whether increased test uptake rates also increase women's use of preventive strategies such as lifestyle modifications.

Acknowledgements

None.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

| Search terms and databases |

| Unless otherwise stated, search terms are free text terms. Abbreviations: '$': stands for any character; '?': substitutes one or no character; adj: adjacent (i.e. number of words within range of search term); exp: exploded MeSH; MeSH: medical subject heading (MEDLINE medical index term); pt: publication type; sh: MeSH; tw: text word. |

| The Cochrane Library |

| #1 MeSH descriptor Reminder Systems explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor Follow‐up studies explode all trees #3 MeSH descriptor Telephone explode all trees #4 MeSH descriptor Telemedicine explode all trees #5 (remind* in All Text or recall* in All Text or letter* in All Text or e‐mail in All Text or email in All Text or sms in All Text or telephon in All Text or telefon in All Text or phon in All Text or fon in All Text or follow‐up in All Text) #6 ( (colo?r in All Text and cod* in All Text) or postcard* in All Text or postal in All Text or (mobile in All Text and phon in All Text) or (internet in All Text and based in All Text) ) #7 (telemedicine in All Text or teleconsultation* in All Text or (medical in All Text and record* in All Text) or (flow in All Text and sheet* in All Text) ) #8 (screen* in All Text or test* in All Text) #9 (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8) #10 MeSH descriptor Diabetes mellitus explode all trees #11 MeSH descriptor Diabetes mellitus explode all trees with qualifiers: PC #12 MeSH descriptor Glucose intolerance explode all trees #13 MeSH descriptor Insulin resistance explode all trees #14 MeSH descriptor Diabetes, gestational explode all trees #15 ( (diabet* in All Text near/6 diagnos* in All Text) or (diabet* in All Text near/6 prevention* in All Text) or (diabet* in All Text near/6 control* in All Text) ) #16 ( (impaired in All Text near/6 glucos* in All Text) and toleranc* in All Text) #17 (glucos* in All Text and intoleranc* in All Text) #18 (insulin in All Text and resistanc* in All Text) #19 (gestational in All Text near/3 diabet* in All Text) #20 gdm in All Text #21 (#10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20) #22 MeSH descriptor postpartum period explode all trees #23 MeSH descriptor Postnatal care explode all trees #24 ( (postpartum in All Text near/6 screen* in All Text) or (postpartum in All Text near/6 management* in All Text) or (postpartum in All Text near/6 period* in All Text) or (postpartum in All Text near/6 care in All Text) ) #25 ( (post in All Text and (partum in All Text near/6 screen* in All Text) ) or (post in All Text and (partum in All Text near/6 management* in All Text) ) or (post in All Text and (partum in All Text near/6 period* in All Text) ) or (post in All Text and (partum in All Text near/6 care in All Text) ) ) #26 ( (postnatal in All Text near/6 period* in All Text) or (postnatal in All Text near/6 care in All Text) or (postnatal in All Text near/6 test* in All Text) ) #27 ( (post in All Text and (natal in All Text near/6 period* in All Text) ) or (post in All Text and (natal in All Text near/6 care in All Text) ) or (post in All Text and (natal in All Text near/6 test* in All Text) ) ) #28 ( (after in All Text near/3 birth in All Text) or (after in All Text near/3 deliver* in All Text) ) #29 (#22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 or #27 or #28) #30 (#9 and #21 and #29) |

| MEDLINE |

| 1 exp Reminder Systems/ 2 exp Follow‐up studies/ 3 exp Telephone/ 4 exp Telemedicine/ 5 (remind* or recall* or letter* or e‐mail or email or sms or telephon or telefon or follow‐up or phon or fon).tw,ot. 6 (colo?r cod* or letter* or postcard* or postal or mobile phon* or internet based).tw,ot. 7 (telemedicine or teleconsultation or medical record or flow sheet).tw,ot. 8 (screen* or test*).tw,ot. 9 or/1‐8 10 exp Diabetes Mellitus/di [Diagnosis] 11 exp Diabetes Mellitus/pc [Prevention & Control] 12 exp Glucose Intolerance/ 13 exp Insulin Resistance/ 14 (diabet* adj6 (diagnos* or prevention* or control*)).tw,ot. 15 (impaired adj6 glucose toleranc*).tw,ot. 16 insulin resistanc*.tw,ot. 17 glucose intoleranc*.tw,ot. 18 exp Diabetes, Gestational/ 19 (gestational adj diabet*).tw,ot. 20 gdm.tw,ot. 21 or/10‐20 22 exp Postpartum Period/ 23 exp Postnatal Care/ 24 ((postpartum or post partum) adj6 (screen* or management* or period* or care)).tw,ot. 25 ((postnatal or post natal) adj6 (period* or care or test*)).tw,ot. 26 (after adj (birth* or deliver*)).tw,ot. 27 or/22‐26 28 randomized controlled trial.pt. 29 controlled clinical trial.pt. 30 randomi?ed.ab. 31 placebo.ab. 32 drug therapy.fs. 33 randomly.ab. 34 trial.ab. 35 groups.ab. 36 or/28‐35 37 Meta‐analysis.pt. 38 exp Technology Assessment, Biomedical/ 39 exp Meta‐analysis/ 40 exp Meta‐analysis as topic/ 41 hta.tw,ot. 42 (health technology adj6 assessment$).tw,ot. 43 (meta analy$ or metaanaly$ or meta?analy$).tw,ot. 44 ((review$ or search$) adj10 (literature$ or medical database$ or medline or pubmed or embase or cochrane or cinahl or psycinfo or psyclit or healthstar or biosis or current content$ or systemat$)).tw,ot. 45 or/37‐44 46 36 or 45 47 (comment or editorial or historical‐article).pt. 48 46 not 47 49 9 and 21 and 27 and 48 50 (animals not (animals and humans)).sh. 51 49 not 50 |

| EMBASE |

| 1 exp reminder system/ 2 exp follow up/ 3 exp telephone/ 4 exp telemedicine/ or exp telecommunication/ 5 (remind*or recall or letter* or e‐mail or email or sms or telephon# or telefon# or phon# or fon# or follow‐up).tw,ot. 6 (colo?r cod* or postcard* or postal or internet based).tw,ot. 7 (telemedicine or teleconsultation* or medical record* or flow sheet).tw,ot. 8 (screen* or test*).tw,ot. 9 or/1‐8 10 exp diabetes mellitus/di [Diagnosis] 11 exp diabetes mellitus/pc [Prevention] 12 exp glucose intolerance/ 13 exp insulin resistance/ 14 exp pregnancy diabetes mellitus/ 15 (diabet* adj6 (diagnos* or prevention* or control*)).tw,ot. 16 (impaired adj6 glucos* toleranc*).tw,ot. 17 (insulin resistanc* or glucose intoleranc*).tw,ot. 18 (gestational adj3 diabet$).tw,ot. 19 GDM.tw,ot. 20 or/10‐19 21 exp puerperium/ 22 exp postnatal care/ 23 ((postpartum or post partum) adj6 (screen* or management* or period* or care)).tw,ot. 24 ((postnatal or post natal) adj6 (period* or care or test*)).tw,ot. 25 (after adj3 (birth* or deliver*)).tw,ot. 26 or/21‐25 27 exp Randomized Controlled Trial/ 28 exp Controlled Clinical Trial/ 29 exp Clinical Trial/ 30 exp Comparative Study/ 31 exp Drug comparison/ 32 exp Randomization/ 33 exp Crossover procedure/ 34 exp Double blind procedure/ 35 exp Single blind procedure/ 36 exp Placebo/ 37 exp Prospective Study/ 38 ((clinical or control$ or comparativ$ or placebo$ or prospectiv$ or randomi?ed) adj3 (trial$ or stud$)).ab,ti. 39 (random$ adj6 (allocat$ or assign$ or basis or order$)).ab,ti. 40 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj6 (blind$ or mask$)).ab,ti. 41 (cross over or crossover).ab,ti. 42 or/27‐41 43 exp meta analysis/ 44 (metaanaly$ or meta analy$ or meta?analy$).ab,ti,ot. 45 ((review$ or search$) adj10 (literature$ or medical database$ or medline or pubmed or embase or cochrane or cinahl or psycinfo or psyclit or healthstar or biosis or current content$ or systematic$)).ab,ti,ot. 46 exp Literature/ 47 exp Biomedical Technology Assessment/ 48 hta.tw,ot. 49 (health technology adj6 assessment$).tw,ot. 50 or/43‐49 51 42 or 50 52 (comment or editorial or historical‐article).pt. 53 51 not 52 54 9 and 20 and 26 and 53 55 limit 54 to human |

| 'My NCBI' alert service |

| postpartum AND diabetes |

Appendix 2. Description of interventions

|

Characteristic Study ID |

Intervention(s) | Comparator(s) |

| Clark 2009 | Postal reminder to physicians and women | No reminder |

| Postal reminder to women only | ||

| Postal reminder to physicians only | ||

| Postal reminders were sent once to the woman and/or the physician approximately 3 months after women gave birth |

Appendix 3. Baseline characteristics (I)

|

Characteristic Study ID |

Intervention(s) and comparator(s) | Duration of intervention (duration of follow‐up) | Participating women | Year(s) of study | Country | Setting | Ethnic groups [%] |

| Clark 2009 | I1: postal reminder to women and physicians at approximately 3 months | 3 months (within 1 year of giving birth) |

Women attending high‐risk obstetric unit for GDM treatment (and their family physicians) | 2002‐2005 | Canada | High‐risk obstetric unit in a university hospital | White 59.3 |

| I2: postal reminder to women only at approximately 3 months | White 57.9 | ||||||

| I3: postal reminder to physicians at approximately 3 months | White 61.3 | ||||||

| C1: no reminder (usual care) | White 74.3 | ||||||

| all: | White 61.4 | ||||||

| GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus | |||||||

Appendix 4. Baseline characteristics (II)

|

Characteristic Study ID |

Intervention(s) and control(s) | Age ≥ 30 years [N (%)] | BMI ≥ 30 kg/m² [N (%)] | Previous GDM [N (%)] | GDM treated with insulin [N (%)] |

| Clark 2009 | I1: postal reminder to women and physicians at approximately 3 months | 59 (72.8) | 30 (37.0) | 8 (9.9) | 48 (59.3) |

| I2: postal reminder to women only at approximately 3 months | 59 (77.6) | 18 (23.7) | 10 (13.2) | 44 (57.9) | |

| I3: postal reminder to physicians at approximately 3 months | 26 (83.9) | 9 (29.0) | 7 (22.6) | 19 (61.3) | |

| C1: no reminder (usual care) | 29 (82.9) | 16 (45.7) | 7 (20.0) | 26 (74.3) | |

| all: | 173 (77.6) | 73 (32.7) | 32 (14.3) | 137 (61.4) | |

| BMI: body mass index; GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus | |||||

Appendix 5. Matrix of study endpoints (publications)

| Study ID | Endpoint reported in publication | Endpoint not measured | Time of measurementa | |

| Clark 2009 | Review's primary outcomes | |||

| Proportion of women having their first OGTT after giving birth | x | Within 1 year after giving birth | ||

| Proportion of women having a blood glucose test other than an OGTT after giving birth | x | ‐ | ||

| Proportion of women diagnosed with type 2 diabetes or showing impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose after giving birth | x | ‐ | ||

| Health‐related quality of life | x | ‐ | ||

| Review's secondary outcomes | ||||

| Diabetes‐associated morbidity | x | |||

| Death from any cause | x | |||

| Adverse events | x | |||

| Blood glucose concentrations | x | ‐ | ||

| HbA1c levels | x | ‐ | ||

| Appropriate referral and/or management | x | |||

| GDM recurrence in the next or any subsequent pregnancy | x | |||

| Depression or depressive symptoms, anxiety, distress (as reported by authors) | x | |||

| Self‐reported 'lifestyle' changes (e.g. increase in exercise or physical activity, dietary modification, weight loss strategies) | x | |||

| Body mass index (BMI) or body weight | x | |||

| Need for insulin or other glucose lowering medications after giving birth | x | |||

| Breastfeeding | x | |||

| Women's views of the intervention | x | |||

| Health professionals' views of the intervention | x | |||

| Costs or other measures of resource use | x | |||

| Other than review's primary/secondary outcomes reported in publication (classification: P/S/O)b | ||||

| Obstetric and neonatal outcomes, and physician characteristics that might lead to increased screening (O) | ||||

| Subgroups reported in publication | ||||

| (1) Effect of physician intervention (all women who received a reminder or no women who received a reminder) (2) Effect of woman intervention (physicians who did or did not receive a reminder) | ||||

| "‐" denotes not reported aUnderlined data denote times of measurement for primary and secondary review outcomes, if measured and reported in the results section of the publication (other times represent planned but not reported points in time) b(P) Primary or (S) secondary endpoint(s) refer to verbatim statements in the publication; (O) other endpoints relate to outcomes which were not specified as 'primary' or 'secondary' outcomes in the publication GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus; HbA1c: glycated haemoglobin A1c; OGTT: oral glucose tolerance test | ||||

Appendix 6. Matrix of study endpoints (trial documents)

|

Characteristic Study ID (trial identifier) |

Endpoint | Time of measurement |

| Clark 2009 [from NCT00212914 entry] | Proportion of women screened for type 2 diabetes with a 2‐hour 75 g OGTT (Pa) | Up to 12 months |

| Proportion of women screened with tests other than a 2‐hour OGTT (S) | Up to 12 months | |

| Characteristics associated with screening: all continuous and categorical characteristics of each woman collected at baseline, the characteristics of the baby, birth complications and characteristics of the physician (S) | ‐ | |

| Characteristics associated with screening for type 2 diabetes mellitus or impaired glucose tolerance (S) | ‐ | |

| Survey (S): the family physicians and woman will be contacted for a semi‐structured interview once the woman is at least six months postpartum. The investigator who is performing the interview will be blinded to the woman's group allocation. Women will be surveyed to determine their satisfaction with the screening method and qualitatively review their suggestions to evaluate barriers to the adoption of the screening recommendation and increase adoption in their practice or experience | ‐ | |

| "‐" denotes not reported Endpoint in bold = review's primary outcome a(P) primary or (S) secondary endpoint(s) refer to verbatim statements in the document; (O) other endpoints relate to outcomes which were not specified as 'primary' or 'secondary' outcomes in the publication OGTT; oral glucose tolerance test | ||

Appendix 7. Survey of authors providing information on trials

|

Characteristic Study ID |

Study author contacted | Study author replied | Study author asked for additional information | Study author provided data |

| Clark 2009 | Yes | No | Yes | No |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Reminder versus no reminder: type of reminder.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Oral glucose tolerance test | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Postal reminder to woman and physician | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.23 [1.85, 9.71] |

| 1.2 Postal reminder to woman | 1 | 111 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.87 [1.68, 8.93] |

| 1.3 Postal reminder to physician | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.61 [1.50, 8.71] |

| 2 Fasting glucose test | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Postal reminder to woman and physician | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.57 [1.01, 2.44] |

| 2.2 Postal reminder to woman | 1 | 111 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.78 [1.16, 2.73] |

| 2.3 Postal reminder to physician | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.69 [1.06, 2.72] |

| 3 Random glucose test | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Postal reminder to woman and physician | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.73 [0.20, 14.91] |

| 3.2 Postal reminder to woman | 1 | 111 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.14 [0.55, 31.46] |

| 3.3 Postal reminder to physician | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.02, 8.88] |

| 4 Glycated haemoglobin A1c test | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Postal reminder to woman and physician | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.18, 1.39] |

| 4.2 Postal reminder to woman | 1 | 111 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.27, 1.79] |

| 4.3 Postal reminder to physician | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.32 [0.50, 3.50] |

| 5 Any test | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Postal reminder to woman and physician | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.65 [1.12, 2.41] |

| 5.2 Postal reminder to woman | 1 | 111 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.73 [1.18, 2.52] |

| 5.3 Postal reminder to physician | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.55 [1.01, 2.38] |

Comparison 2. Reminder versus no reminder: type of test.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Type of test | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Oral glucose tolerance test | 1 | 223 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.98 [1.75, 9.05] |

| 1.2 Fasting glucose tolerance test | 1 | 223 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.68 [1.10, 2.54] |

| 1.3 Random glucose tolerance test | 1 | 223 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.42 [0.33, 17.91] |

| 1.4 Glycated haemoglobin A1c test | 1 | 223 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.31, 1.62] |

| 1.5 Any test | 1 | 223 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.66 [1.15, 2.41] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Clark 2009.

| Methods |

Factorial randomised controlled clinical trial (NCT00212914) Randomisation ratio: 2 x 2 factorial trial (2:1 ratio for physician/women reminders and women‐only reminders versus physician‐only reminders and controls (no reminders)) |

|

| Participants |

256 women were randomised into four groups (see 'Interventions' below) Inclusion criteria: women, regardless of age, who attended the High Risk Obstetrical Unit (Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) between 29 August 2002 and 31 March 2005, for treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus (diagnostic criteria for GDM not reported) and who provided written informed consent. Exclusion criteria: no family physician, the family physician already had a woman enrolled, the woman was already enrolled from a previous pregnancy, the birth did not take place at Ottawa Hospital, there was no live birth, or contact was lost with the woman or her family physician by the end of study survey. Diagnostic criteria: NA |

|

| Interventions |

Number of study centres: 1 (Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) Treatment before study: NA Titration period: NA 1) Reminder sent to physician and woman at ˜3 months: n = 88: informed the physician that the woman had received a requisition for the recommended screening test. 2) Reminder sent to the woman but not to the physician at ˜3 months: n = 84: reminded the woman of the importance of screening and contained the laboratory requisition to complete a screening OGTT. 3) Reminder sent to the physician but not the woman at ˜3 months: n = 41: included the CDA recommendation and a woman‐specific recommendation from the GDM healthcare team to screen the woman during the postpartum period for diabetes mellitus with an OGTT. 4) No reminder sent (usual care): n = 43: no information sent to woman or the physician from the study regarding postpartum screening. Postal reminders were sent once to the woman and/or the physician approximately 3 months after the woman gave birth to conform with the recommended screening time period of 6 weeks to 6 months. |

|

| Outcomes |

Objective outcome Primary outcome: proportion of women who underwent an OGTT within 1 year of giving birth Secondary outcome: performance of other postpartum screening tests (venous fasting glucose, venous random glucose, glycated haemoglobin or any combination of these) |

|

| Study details |

Run‐in period: NA Study terminated before regular end: no Registered with ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00212914 |

|

| Publication details |

Language of publication: English Other funding: Canadian Institute of Health Research, Knowledge Translation and Exchange Publication status: full article |

|

| Stated aim of study | Quote from publication: "to determine whether postal reminders that are sent after delivery to a patient [with gestational diabetes mellitus], to her physician, or to both would increase postpartum screening" | |

| Notes | Rationale for the 2:1 randomisation ratio not fully explained (the authors assumed physicians would be more likely to comply with recommendations delivered at the time the decision is made than women who received the recommendation). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote from publication: "computer‐generated randomization list"; quote from ClinicalTrials.gov: "The design is a 2 x 2 factorial randomized controlled trial stratified by clinic location. Randomization will be performed by the Research Coordinator using a computer generated randomization number and a variable block size of 4 and 8" Comment: adequate method |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote from publication: "assigned randomly" Comment: insufficient information provided to judge if there was adequate allocation concealment |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Objective outcomes | Unclear risk | Quote from publication: "The investigators and statistician were blinded to group allocation because the patients were not seen routinely after delivery in follow‐up"; quote from ClinicalTrials.gov: "The HRU team, the investigators, and the patient will be blinded to the patient's group allocation" Comment: women were not blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Objective outcomes | Low risk | Quote from publication: NA; quote from ClinicalTrials.gov: "All patients will have a similar process and similar intensity in the follow‐up of the screening results. We expect with this method of ascertaining the primary outcome we will be able to determine whether the patient was screened or not. The investigator who is gathering the information from the physician or patient will be blinded to the patient's group allocation" Comment: not reported in publication reporting the study findings |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Objective outcomes | Unclear risk | Quote from publication: "33 patients were lost to follow‐up and were excluded from the analysis" Comment: 33/256 (13%) lost to follow‐up.

The attrition rate was higher (more than double) in the two groups of women not sent a reminder than in the two groups of women sent a reminder; the authors reported two analyses, one assuming that all women lost to follow‐up were screened and the other that they were not screened, stating "results were unchanged" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: most expected outcomes were reported, although women's or physicians' views were not reported, nor were any morbidity or resource use outcomes |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Comment: perhaps some imbalance in baseline characteristics ‐ women in the usual care and physician‐only reminder group were older and more likely to have had previous GDM than the other groups; the usual care and women/physician‐reminder group had a higher mean BMI than the other groups |

BMI: body mass index; CDA: Canadian Diabetes Association; GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus; GP: general practitioner; HRU: High Risk Obstetrical Clinics; NA: not applicable; OGTT: oral glucose tolerance test

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Lega 2012 | Retrospective chart review |

| Shea 2011 | Study of implementation of postpartum reminders into routine care |

| Vesco 2012 | Before and after implementation study; system changes as well as postpartum reminders |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Heatley 2013.

| Trial name or title | Acronym: DIAMIND |

| Methods |

Allocation: telephone randomisation using a randomisation schedule with balanced variable blocks, prepared by a researcher not involved with recruitment or clinical care Masking: partial ‐ personnel administering the intervention; personnel assessing outcomes Primary purpose: to assess the impact of short message service text reminders on uptake of postpartum diabetes screening (glucose tolerance tests) |

| Participants |

Condition: gestational diabetes mellitus Enrolment: after giving birth and before discharge from hospital Inclusion criteria: women diagnosed with gestational diabetes in their index pregnancy (positive oral glucose tolerance test with fasting glucose ≥ 5.5 mmol/L or two‐hour glucose level ≥ 7.8 mmol/L, or both), with access to a personal mobile phone, whose blood glucose profile measurements prior to discharge were normal (finger prick fasting value < 6 mmol/L and postprandial values of < 8 mmol/L), who provide written, informed consent Exclusion criteria: pregestational diabetes mellitus; triplet or higher order multiple birth or stillbirth in the index pregnancy; requirement for interpreter |

| Interventions |