Abstract

We assessed the feasibility of obtaining parent-collected General Movement Assessment videos using the Baby Moves app. Among 261 participants from 4 Chicago NICUs, 70% submitted videos. Families living in higher areas of childhood opportunity used the app more than those from areas of lower opportunity.

Keywords: General Movement Assessment, pediatric telehealth, infant assessment, Childhood Opportunity Index, NICU Follow-up

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that infants who graduate from a NICU with a high likelihood of having neurodevelopmental disorders receive referrals to specialty follow-up clinics1. While these referrals may be made by NICU providers, the rate of attrition is high, ranging from 10–30% in Australia2 and Canada3, and up to 60% in the United States4–7. Factors that have been significantly associated with those who have difficulty with attendance to follow-up clinic include greater travel distance from clinic8 and older infant gestational age6. Furthermore, the reasons for this attrition have been described as being related to decreased parental social support9, lack of parental resources9, and difficulty scheduling by the parent or provider6.

While addressing the challenges of follow-up clinic attendance for infants with neurodevelopmental concerns is essential, it is worth noting that recent developments in healthcare delivery have created new possibilities. The demand for pediatric telehealth has dramatically increased in recent years after the COVID-19 pandemic10. As a result, policies, payment methods, and acceptance of pediatric telehealth by providers and users have also changed11. This new landscape provides opportunity to ameliorate health inequities related to access to care for populations that are under-resourced using telehealth, including parent-collected data via smartphone apps.

A specific infant assessment that is well-suited for telehealth is the Prechtl General Movement Assessment12. The General Movement Assessment (GMA) is a method for evaluating infant spontaneous movements using a videorecording of infant movement behavior which is scored by a trained assessor. The GMA is the most predictive clinical tool for cerebral palsy (CP) in the young infant13 and is recommended for use in all infants with newborn detectable factors that increase the possibility of having CP14. Many infants who have been hospitalized in a NICU would benefit from receiving a GMA, however implementation has been limited by two primary factors, a lack of trained assessors at each NICU site and high attrition rates to NICU follow-up clinics.

In 2016, the Baby Moves smartphone application (app) was introduced by an Australian research team15 and tested on a large geographical cohort of extremely low birth weight infants and term-born controls16. The use of the app was a feasible method to collect data in the Australian sample16 and was valid in prediction of CP, equivalent to traditional in-person visits17. The goal of our study was to test the feasibility of the Baby Moves smartphone app as a data collection method in a large urban city in the United States, which has differing health care policies and provider networks than the original Australian sample. We examined the feasibility of the Baby Moves smartphone app in a diverse sample, stratified by residence in regions of various childhood opportunity resources in a large US urban population.

Methods

Participants

Infants were recruited prospectively from four neonatal intensive care units (NICU) in Chicago (University of Chicago Medical Center, Northwestern Medicine, University of Illinois Health, and Loyola University Medicine) between August 2019 and May 2022. Recruited infants required either a NICU hospitalization for moderate to late preterm (MLP) birth (32–36 weeks of gestation), or because they had factors that increased the chance of developing CP including very preterm birth (<32 weeks) or other neurological factors (abnormal head ultrasound or MRI findings). Demographic characteristics (including race and ethnicity) and medical histories were extracted from the medical records for each participant. Infants were then stratified by group into those having a higher chance of having CP (born <32 weeks gestational age or with abnormal neuroimaging) or having a moderate chance of developing CP (born moderate-late preterm with no other neurological concerns). Abnormal neuroimaging was defined as any incidence of intraventricular hemorrhage, white matter abnormalities, subcortical or cerebellar lesions, or ventricular enlargement found on either cranial ultrasound or MRI. Informed parental consent was obtained for each infant, and ethics approval for the study was granted by the institutional review board at each participating hospital.

Geocoding and Spatial Analysis

We geocoded each participant’s residential address obtained at the time of birth using ArcGIS Pro version 3.0.1 (Esri, Redlands, CA), a standard Geographic Information Systems (GIS) desktop application. Geocoding is the process of converting textual information, such as an address, into a spatial feature. In total, 253 participant addresses were successfully geocoded. Participant’s addresses were subsequently anonymized by setting a minimum distance from the original address. Datapoints were then randomized within these distances and bounded by Census tracts to keep consistent with the original addresses. Next, the anonymized addresses were overlaid on Census tract-level Childhood Opportunity Index (COI) data for the year 201518 (the most recent COI data available).

We analyzed a subset of subjects who had an address in Cook County, IL, a county which encompasses Chicago and the metropolitan area (population 5,109,29219). Network Analyst extension was used to calculate driving times from each participant’s anonymized address to the nearest Level III NICU center in Cook County. We categorized driving times as 0–15 minutes or greater than 15 minutes. Two maps were created by spatially joining together geocoded participant addresses overlaid on regions of childhood opportunity and estimated drive times respectively.

Childhood Opportunity Index (COI) 2.0

The COI 2.018 has 29 indicators in 3 domains (education, health and environment, and social and economic). COI 2.018 includes variables such as access to quality education, green spaces, healthy food, toxin-free environments, and employment. The developers of COI 2.018 standardized the indicators into composite indices using a z-score transformation and calculated a weighted average across each domain to obtain average domain z-scores. Indicator-specific weights reflect predictions of children’s long-term health and economic outcomes. Domain z-scores are combined into an overall score and define child opportunity levels by ranking neighborhoods into 5 groups (Very Low, Low, Moderate, High, and Very High) based on their scores18. COI 2.0 are available as metro, state, and nationally normalized data. In this analysis we used the nationally normalized COI 2.0 data18.

Video Data Collection

After enrolling in the study, the Baby Moves app20 notified participating families to take a video of the infant at two timepoints: between 12- and 13- weeks and between 14- and 16-weeks corrected age. The app provided families with detailed instructions to record and upload a 3-minute video of the child while actively moving. Infants were filmed in a quiet, alert state (without a pacifier) in the supine position. Videos were then uploaded directly to a research database (REDCap 11.1.21; Vanderbilt University) to be scored by assessors with advanced certification in the Prechtl GMA12 and the Motor Optimality Score Revised (MOS-R)21.

General Movement Assessment and Motor Optimality Score-Revised

A team of trained assessors scored infant videos between 12 and 16 weeks (and 6 days) corrected age, according to Prechtl methodology12. The same video was also used to score the MOS-R21, a detailed scoring of the GMA. Raters were blinded to the infant’s clinical histories at time of assessment.

Statistical Analyses.

Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.1 (2022–06-23). Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample were summarized using standard descriptive statistics. We used Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, chi square tests and Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate, to compare characteristics between infants whose families submitted either one or two videos. We included the characteristic of race and ethnicity to describe the demographics of the users of the app, however when comparing the number of videos, we adjusted the analysis by including COI as a covariate to decrease bias of racial and ethnic differences. We used linear regression to determine if there were associations between the MOS-R and childhood opportunity among children categorized as having high or moderate chance of having CP. Because children in the moderate chance group were all recruited from the same hospital (as the only recruitment criteria), we analyzed the relationship between MOS-R and COI separately from those who were categorized as having a high chance of developing CP. A two-tailed p value of ≤ 0.05 defined statistical significance.

Results

Participants

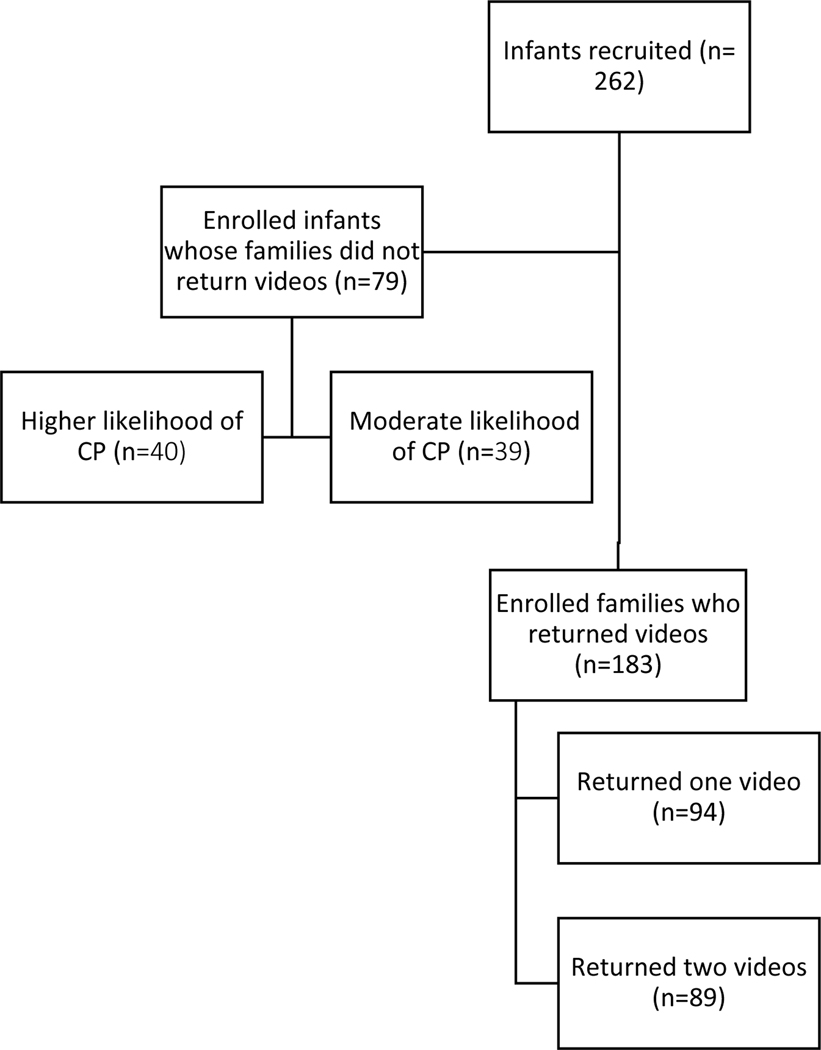

We enrolled 261 participants, including 112 infants who had a history of late-moderate preterm birth with no other medical conditions and 149 infants (57%) with medical complexity which qualified them for a NICU developmental follow-up clinic. The flow chart of participant involvement in study is detailed in Figure 1; 183 infants (70%) were included for analysis of movement data by video recording. Among all participants, a total of 272 videos were submitted. Of these videos, two were not scorable (<1%) because the child was too irritable. Six videos (2%) were rated as poor quality due to short length (n=2), infant wearing clothing which covered limbs (n=3), or camera angle misaligned (n=1). Reasons for not submitting any videos included attrition or technical difficulties with the app22. Additional reasons for submitting only one video included later enrollment into study after 12–13 weeks gestational age, difficulties with infant’s family cell phone, and the family was provided with a reminder to complete a recording after the first video was due.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of enrolled participants

Within the sample of recruited infants (n=261), a total of 199 different Census Tracts were identified. Most children enrolled (n= 109, 42%) were living in an area that, at time of birth, was considered to have a Very Low Childhood Opportunity Index (COI). The remainder of the sample were living in Very High (15%), High (21%) Moderate (10%) and Low (10%) regions of childhood opportunity. Two percent of the sample was not geocoded due to missing address data. Figure 2 details the anonymized addresses of participants mapped onto COI regions.

Figure 2.

Anonymized geocoded addresses of Baby Moves App participants at birth plotted on a map of Cook County, Illinois, categorized by nationally normed Childhood Opportunity Levels in 2015.

Group Differences by Drive Time to a Level III NICU Center

Figure 3 depicts the driving times to the nearest Level III NICU Center in Cook County, Illinois among the participants. Drive time was associated with COI level (p=0.008). Families living in regions of High COI had 3.0 times the odds of a shorter drive to the nearest NICU (95%CI: 1.16–8.85). Similarly, families living in regions of Very High COI had 8.73 higher odds of having a shorter drive time compared with families living in regions of Very Low COI (95%CI: 1.62–162.3).

Figure 3.

Anonymized geocoded addresses of Baby Moves App participants at birth plotted on a map of Cook County, Illinois, categorized by drive times to the nearest Level III NICU Center.

Group Differences among Those Who Submitted One or Two Videos

Infants whose families submitted only one video displayed significantly lower birthweights and gestational ages and were more likely to have been categorized as having a higher chance of developing CP compared with families who submitted two videos (Table I). Race and ethnicity were initially significant different between these two groups, however, after adjusting for COI (confounding variable), these differences were no longer statistically significant (Table I).

Table 1.

Medical and demographic characteristics of 183 infants and families who submitted one or two videos using the BabyMoves smartphone app

| One Video (n=94) | Two Videos (n=89) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational Age in weeks, median (IQR) | 29 (26,33) | 33 (28, 35) | <0.001a |

|

| |||

| Birthweight in grams, median (IQR) | 1151 (708, 4295) | 1956 (940, 2530) | <0.001a |

|

| |||

| English is primary anguage (%) | 74 (86) | 79 (94) | 0.138b |

|

| |||

| Multiple gestation birth (%) | 15 (17) | 10 (11) | 0.405b |

|

| |||

| Developmental Chance of Having CP (%) | |||

| Moderate | 29 (32) | 45 (51) | 0.013b |

| High | 63 (68) | 44 (49) | |

|

| |||

| Childhood Opportunity Index (%) | |||

| Very High | 9 (10) | 18 (20) | 0.055b |

| High | 19 (21) | 25 (28) | |

| Moderate | 9 (10) | 12 (14) | |

| Low | 7 (8) | 6 (7) | |

| Very Low | 46 (51) | 27 (31) | |

|

| |||

| Race and ethnicity (%) | |||

| Asian | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | Unadjusted p =0.010c |

| Hispanic | 15 (16) | 11 (12) | Adjusted p= 0.77d |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 42 (45) | 22 (25) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 35 (38) | 42 (47) | |

| Other | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | |

| Unknown | 7 (8) | 12 (13) | |

Symbols in p-value column indicate the statistical test used for group comparison as follows:

Wilcoxon rank sum

Chi-square test

Fisher exact test

Adjusted p-value was calculated using logistic regression, adjusted for COI

When comparing the number of videos returned among families, there was no overall difference in the infant’s COI categorizations (p=0.056). However, compared with families living in Very Low COI regions, families from Very High COI regions had 3.41 times the odds of submitting two videos (95% CI 1.37–8.97) and families from High COI regions had 2.24 times the odds of submitting two videos (95% CI 1.05–4.86). Differences between groups of infants who did and did not submit videos were reported previously22.

Motor Optimality Scores by Childhood Opportunity Index

Motor optimality (MOS-R) scores did not significantly differ by COI between groups of infants having either moderate or high chance of developing CP (p=0.557 and p=0.723 respectively). The assessment of fidgety movements and Motor Optimality Scores in this cohort have been previously described22.

Discussion

Through the implementation of the Baby Moves smartphone application, we demonstrated the feasibility of collecting parent-recorded GMA data from a diverse sample of infants residing in areas with differing levels of childhood opportunity. Our findings showcase the potential of this novel approach for improving the reach and scope of developmental monitoring for infants after NICU discharge. More specifically, our high return rate (70%) of parent-collected neurodevelopmental data at 3 months was greater than previously reported rates of return to developmental follow-up clinic visits in the US6, 7. Evaluation at this important timepoint allows providers to refer children to services at the time of greatest brain plasticity, maximizing their impact.

We found that families living in areas of Very Low childhood opportunity used the app less, highlighting a need for targeted supports to ensure equitable access to resources like this app. The use of a smartphone app could serve as a solution to previously identified barriers to follow-up attrition as it eliminates the need to travel from to a clinic, does not require a scheduled appointment, and reduces the additional time and financial resources associated with an in-person visit. Moreover, most children in our sample were living in communities with limited resources, classified as having Very Low Childhood Opportunity. These families faced considerably longer travel times to the nearest NICU center compared with families living in areas with High or Very High Childhood Opportunity, potentially making it even more challenging for them to attend in-person appointments. Hence, utilizing an app in the home setting may represent a solution for enhancing the engagement, contact and monitoring of NICU graduates who face difficulties attending a follow-up clinic. While the short video of the infant sent by parents for our study does not replace the type of assessment that infants receive in follow-up clinic, it did provide adequate information for completion of the GMA and MOS-R and delineates infants who would benefit from additional follow-up. This model of data analysis may also be beneficial for other research trials or clinical applications where clinical teams do not have trained GMA assessors on site in NICU follow-up clinics.

The Baby Moves app has been used successfully to study general movements in a large Australian cohort of extremely low birth weight and full-term infants covering a large geographical area16. We shared similar success with implementation of the app in a large urban city in the United States, despite differing health care systems in these two countries. Additionally, we observed that the usage of the Baby Moves app among our sample was similar to the Australian cohort16. We found that families of infants who had a lower gestational age and birthweight used the app less than families of infants who had higher gestational age and birth weights, mirroring previously reported findings16. Furthermore, we found that families of children living in regions of Very Low childhood opportunity utilized the app less than those living in areas of High of Very High childhood opportunity, consistent with previous findings related to app usage by socioeconomic status16. However, we did not replicate all findings of the Australian study16. While the Australian team found a difference in app utilization between participants who did and did not speak English as a primary language, we did not find a difference between these groups. The majority of our participants were primarily English speakers which may have explained our different findings and may also be a source of bias in our sample.

We included two samples of infants, moderate-late preterm infants (32–36 weeks gestational age) and those traditionally monitored in developmental follow-up clinics (<32 weeks gestational age or with abnormal neuroimaging findings), to utilize the Baby Moves App. Although infants born moderate-late preterm do not often qualify for follow-up programs, they still have increased incidence of neurodevelopmental adversity23, 24 and structural brain differences25–27 compared with term-born peers. Therefore, employing the Baby Moves app to collect GMA data in this population may be a method to provide some follow-up screening for these children without requiring the full resources of an in-person visit. The second population we tested included those infants that are more regularly referred for NICU follow-up clinic.

While we did not specifically collect data on attrition rates to the NICU follow-up clinics in our study prior to use of the app, others have found that the attrition rate for the first visit at NICU follow-up clinic in large urban US cities has been found to be as high as 40%4, 6, with attrition increasing in subsequent visits to over 60%7. We had a 70% return rate overall for all participants, suggesting the Baby Moves app may be another way to engage and monitor the those infants who would otherwise not return for follow-up assessment. Furthermore, because infants with higher attrition rates have been reported to have higher incidences of disability2, 28, 29, it is imperative that these children be followed and triaged into appropriate intervention services. Further qualitative work is needed to understand how to improve usability of the app to improve engagement for all families.

Our study design had limitations as one hospital site included only children with moderate-late preterm birth, and therefore excluded most children who met the criteria for developmental follow-up clinics. This hospital site had a larger proportion of patients residing in areas categorized as Very High, High, or Moderate COI. In our sample, we found that families with infants with moderate chance of developing CP had greater engagement with the app than those with higher chance of developing CP. Because of our hospital site recruitment, it is difficult to disentangle whether these differences were due mostly to socioeconomic status (COI level), medical complexity, or a combination of these factors. Due to this design limitation, we analyzed MOS-R scores separately for groups of children with different chances of having CP (moderate chance and high chance). Although we found no significant differences in MOS-R scores among groups based on COI, this may be influenced by our study design, as the groups were analyzed within more homogeneous COI regions. Future studies should include children with the highest likelihood of developing CP from various COI areas to gain a better understanding of the relationship between COI and spontaneous motor behavior.

In conclusion, our implementation of the Baby Moves smartphone application showed feasibility in collecting parent-recorded GMA data for a diverse sample of infants residing in areas with varying levels of childhood opportunity in a large US city. We suggest that this approach has the potential to enhance the accessibility and inclusivity of infant developmental follow-up after NICU discharge, improve identification and triage of children into timely and appropriate intervention services, and improve developmental outcomes and family support.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank Meg Naber and the participating families and infants for their important contributions.

Funding Sources:

This project was generously supported by Northwestern University Department of Physical Therapy and Human Movement Science and the Shirley Ryan Ability Lab. CP receives support from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant KL2TR001424. Michael Msall was supported in part by T73 Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental and Related Disorders Training Program (LEND, T73MC11047) and the Health Resources and Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services (UA6MC32492), the Life Course Intervention Research Network. Preterm Research Node: Engaging Families of Preterm Babies to Optimize Thriving and Well-Being.

Footnotes

Reprints: no reprints requested

Conflict of Interest: Peyton and Spittle are members of the General Movements Trust Speakers Bureau. deRegnier is an Associate Editor for The Journal of Pediatrics.

References:

- [1].Newborn FA. Hospital discharge of the high-risk neonate. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1119–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Callanan C, Doyle LW, Rickards AL, Kelly EA, Ford GW, Davis NM. Children followed with difficulty: how do they differ? Journal of paediatrics and child health. 2001;37:152–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ballantyne M, Stevens B, Guttmann A, Willan AR, Rosenbaum P. Transition to neonatal follow-up programs: is attendance a problem? The Journal of perinatal & neonatal nursing. 2012;26:90–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Brachio SS, Farkouh-Karoleski C, Abreu A, Zygmunt A, Purugganan O, Garey D. Improving neonatal follow-up: a quality improvement study analyzing in-hospital interventions and long-term show rates. Pediatric quality & safety. 2020;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tyson JE, Lasky RE, Rosenfeld CR, Dowling S, Gant N Jr. An analysis of potential biases in the loss of indigent infants to follow-up. Early human development. 1988;16:13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Swearingen C, Simpson P, Cabacungan E, Cohen S. Social disparities negatively impact neonatal follow-up clinic attendance of premature infants discharged from the neonatal intensive care unit. Journal of Perinatology. 2020;40:790–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tang BG, Lee HC, Gray EE, Gould JB, Hintz SR. Programmatic and administrative barriers to high-risk infant follow-up care. American Journal of Perinatology. 2018;35:940–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ballantyne M, Stevens B, Guttmann A, Willan AR, Rosenbaum P. Maternal and infant predictors of attendance at Neonatal Follow-Up programmes. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2014;40:250–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ballantyne M, Benzies K, Rosenbaum P, Lodha A. Mothers’ and health care providers’ perspectives of the barriers and facilitators to attendance at C anadian neonatal follow-up programs. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2015;41:722–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Brotman JJ, Kotloff RM. Providing outpatient telehealth services in the United States: before and during coronavirus disease 2019. Chest. 2021;159:1548–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Koonin LM, Hoots B, Tsang CA, Leroy Z, Farris K, Jolly B, et al. Trends in the use of telehealth during the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January–March 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69:1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Einspieler C, Prechtl HF, Bos AF, Ferrari F, Cioni G. Prechtl’s method on the qualitative assessment of general movements in preterm, term and young infants: McKeith Press; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bosanquet M, Copeland L, Ware R, Boyd R. A systematic review of tests to predict cerebral palsy in young children. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2013;55:418–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Novak I, Morgan C, Adde L, et al. Early, accurate diagnosis and early intervention in cerebral palsy: Advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA Pediatrics. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Spittle AJ, Olsen J, Kwong A, Doyle LW, Marschik PB, Einspieler C, et al. The Baby Moves prospective cohort study protocol: using a smartphone application with the General Movements Assessment to predict neurodevelopmental outcomes at age 2 years for extremely preterm or extremely low birthweight infants. BMJ open. 2016;6:e013446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kwong AKL, Eeles AL, Olsen JE, Cheong JLY, Doyle LW, Spittle AJ. The Baby Moves smartphone app for general movements assessment: Engagement amongst extremely preterm and term-born infants in a state-wide geographical study. Journal of paediatrics and child health. 2019;55:548–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kwong AKL, Doyle LW, Olsen JE, Eeles AL, Zannino D, Mainzer RM, et al. Parent-recorded videos of infant spontaneous movement: Comparisons at 3–4 months and relationships with 2-year developmental outcomes in extremely preterm, extremely low birthweight and term-born infants. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Noelke C, Noelke C, McArdle N. Child Opportunity Index 2.0. Published online. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Population Estimates, July 1, 2022, Cook County, Illinois. Quick Facts: U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kwong AKL, Doyle LW, Olsen JE, Eeles AL, Lee KJ, Cheong JLY, et al. Early motor repertoire and neurodevelopment at 2 years in infants born extremely preterm or extremely-low-birthweight. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Einspieler C, Bos AF, Krieber-Tomantschger M, Alvarado E, Barbosa VM, Bertoncelli N, et al. Cerebral palsy: early markers of clinical phenotype and functional outcome. Journal of clinical medicine. 2019;8:1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Peyton C, Millman R, Rodriguez S, Boswell L, Naber M, Spittle A, et al. Motor Optimality Scores are significantly lower in a population of high-risk infants than in infants born moderate-late preterm. Early Human Development. 2022:105684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].de Gamarra-Oca LF, Ojeda N, Gómez-Gastiasoro A, Peña J, Ibarretxe-Bilbao N, García-Guerrero MA, et al. Long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes after moderate and late preterm birth: a systematic review. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2021;237:168–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Cheong JL, Doyle LW, Burnett AC, Lee KJ, Walsh JM, Potter CR, et al. Association between moderate and late preterm birth and neurodevelopment and social-emotional development at age 2 years. JAMA pediatrics. 2017;171:e164805-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].KellE, Thompson DK, Spittle AJ, Chen J, Seal M, Anderson PJ, et al. Regional brain volumes, microstructure and neurodevelopment in moderate–late preterm children. Archives of Disease in Childhood-Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 2020;105:593–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kelly CE, Cheong JLY, Gabra Fam L, Leemans A, Seal ML, Doyle LW, et al. Moderate and late preterm infants exhibit widespread brain white matter microstructure alterations at term-equivalent age relative to term-born controls. Brain Imaging and Behavior. 2016;10:41–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Walsh JM, Doyle LW, Anderson PJ, Lee KJ, Cheong JLY. Moderate and late preterm birth: effect on brain size and maturation at term-equivalent age. Radiology. 2014;273:232–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tin W, Fritz S, Wariyar U, Hey E. Outcome of very preterm birth: children reviewed with ease at 2 years differ from those followed up with difficulty. Archives of Disease in Childhood-Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 1998;79:F83–F7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wolke D, Söhne B, Ohrt B, Riegel K. Follow-up of preterm children: important to document dropouts. The Lancet. 1995;345:447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.