SUMMARY

The sole unifying feature of the incredibly diverse Archaea is their isoprenoid-based ether-linked lipid membranes. Unique lipid membrane composition, including an abundance of membrane-spanning, tetraether lipids, impart resistance to extreme conditions. Many questions remain, however, regarding the synthesis and modification of tetraether lipids, and how dynamic changes to archaeal lipid membrane composition support hyperthermophily. Tetraether membranes, termed glycerol dibiphytanyl glycerol tetraethers (GDGTs), are generated by tetraether synthase (Tes) by joining the tails of two bilayer lipids known as archaeol. GDGTs are often further specialized through addition of cyclopentane rings by GDGT ring synthase (Grs). A positive correlation between relative GDGT abundance and entry into stationary phase growth has been observed, but the physiological impact of inhibiting GDGT synthesis has not previously been reported. Here, we demonstrate that the model hyperthermophile Thermococcus kodakarensis remains viable when Tes (TK2145) or Grs (TK0167) are deleted, permitting phenotypic and lipid analyses at different temperatures. The absence of cyclopentane rings in GDGTs does not impact growth in T. kodakarensis, but an overabundance of rings due to ectopic Grs expression is highly fitness negative at supra-optimal temperatures. In contrast, deletion of Tes resulted in the loss of all GDGTs, cyclization of archaeol, and loss of viability upon transition to stationary phase in this model archaea. These results demonstrate the critical roles of highly specialized, dynamic, isoprenoid-based lipid membranes for archaeal survival in high temperature.

Keywords: Tetraether lipids, tetraether synthase, GDGT, archaeol, thermophily, archaea

Plain Language Summary

The preponderance of tetraether membrane spanning lipids in many archaeal clades indicates a fitness advantage of unique membranes for archaeal survival. The inability to rationally control the synthesis of tetraether, and cyclized tetraether-lipids has limited investigations into how dynamic shifts in lipid composition support archaeal growth and phase transitions. Employing the facile genetic system of the model hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis that naturally synthesizes abundant tetraether lipids, we identified and targeted the genes necessary for tetraether lipid synthesis and derivatization. While impairing tetraether lipid biosynthesis is possible, the lack of specialized lipids dramatically impairs long-term survival, supporting a critical role for dynamic lipidome changes in supporting archaeal life in the extremes.

Graphical Abstract

Unique archaeal lipid membrane composition, including membrane-spanning, tetraether lipids, presumably contribute to survival in extreme pH, temperature, and salinity. Biosynthesis of tetraether lipids in the model species Thermococcus kodakarensis promotes survival at high temperature and we demonstrate that alternative lipid species are produced when tetraether lipid biosynthesis is compromised.

INTRODUCTION

The diversity of marine and terrestrial environments containing an abundance of microbial life continues to expand and often beguiles the limits of life itself. Archaea often dominate and thrive in the extremes of temperature, salinity, pressure, and pH (Merino et al., 2019; Teske et al., 2021). The unique, domain-specific, isoprenoid-based lipid membranes generated by all Archaea (Koga, 2014) are thought to assist but cannot completely resolve rationales for survival in the extremes. Beyond compositional and structural differences, the dynamic response of archaeal lipid membranes to changes in growth phase, growth rate, and temperature support adaptive responses to rapid and often dramatic stimuli in highly volatile environments (Elling et al., 2014; Hurley et al., 2016; Qin et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2023; Zhou et al., 2020).

Archaeal membranes are composed of glycerol-1-phosphate (G1P) ether-linked to two isoprenoid-based branched chains, typically 20 carbons each (archaeol) (Fig.1). Archaeal lipid composition contrasts with the glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) ester-linked fatty acid-based lipids common in Bacteria and Eukarya (Matsumi et al., 2011; Straub et al., 2018). Many archaea also fuse their diether bilayers (archaeols) to form tetraether monolayer membranes known as glycerol dibiphytanyl glycerol tetraethers (GDGTs) (Fig.1) (Matsumi et al., 2011; Straub et al., 2018). GDGTs are further modified through addition of cyclopentane or cyclohexane rings within the isoprenoid chains to generate a series of cyclized GDGTs (Sinninghe Damsté et al., 2002). The properties, and potential biotechnological and commercial value of archaeal isoprenoid-based lipids demand an understanding of their synthesis and role in promoting fitness in extreme habitats.

Figure 1. Tetraether lipid biosynthetic pathway in T. kodakarensis.

The C20 isoprenoid chains of archaeol are covalently linked to generate GDGT (also termed GDGT-0), through the activity of TK2145, Tk-Tes, with GTGT and macrocyclic archaeol (MA) as intermediate or side products, respectively. Production of cyclized-tetraether lipids (GDGT-1, 2, 3, 4), is catalyzed by TK0167, Tk-Grs. Archaeol-1 and archaeol-2 are detected only in strains ectopically expressing Tk-Grs or those with disruption of native Tk-Tes activities.

The formation of GDGT from archaeol and subsequent cyclization are thought to primarily modify cell membrane fluidity and permeability, aiding archaeal organisms to adapt to a wide range of environmental parameters (Valentine, 2007; Van de Vossenberg et al., 1998a; Zhou et al., 2020). The dynamic changes of archaeal lipid composition in response to environmental variation, combined with the geologically relevant stability of archaeal lipids, also provide a reliable method to infer ancient sea surface temperatures, informing paleoclimate studies (Schouten et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016). Further, the unique properties of archaeal lipid membranes, often termed archaeosomes, offer promise for therapeutic approaches, including nano-drug delivery protocols and vaccine delivery as an alternative to the more conventional liposome-based systems (Jia et al., 2022; Lilia Romero & Jose Morilla, 2023; Santhosh & Genova, 2022). Controlled and reliable production of specialized archaeosomes with novel compositions and novel properties is also of major biotechnological interest. However, while GDGT properties have been readily investigated in artificial systems, biological platforms wherein GDGT and cyclized GDGT synthesis can be controlled and regulated are lacking.

GDGT synthesis is achieved through the action of the radical S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) superfamily protein GDGT-macrocyclic archaeol synthase (GDGT-MAS) (Lloyd et al., 2022) also known as tetraether synthase (Tes) (Zeng et al., 2022). Formation of cyclopentane rings in GDGT-0 (no rings) at the C-7 and C-3 positions is catalyzed by another radical SAM superfamily protein, GDGT ring synthase (Grs), first characterized in Sulfolobus acidocaldarius (Zeng et al., 2019). While biochemical studies have determined the enzymes responsible for production of GDGT-0 and its cyclized derivatives, biological manipulations have been lacking due to presumed essentiality of Tes (Zeng et al., 2022). Thermococcus kodakarensis is a highly versatile, genetically tractable hyperthermophilic, anaerobic, archaeon that naturally synthesizes GDGT-0, and to a much lesser extent, its ring bearing derivatives. The relative abundance of GDGT lipids in T. kodakarensis under optimal growth conditions has been determined in previous studies and found to vary between ~25 – 80% based on the extraction and analysis methods used. T. kodakarensis undergoes substantial diether to tetraether lipid composition changes in response to temperature and growth phase (Matsuno et al., 2009; Tourte et al., 2020) that GDGT synthesis, which involves Tes activities, contributes to hyperthermophilic physiology. In this study, we generated Tes and Grs deletion mutants demonstrating that neither tetraether membrane formation nor membrane cyclization was essential in T. kodakarensis. Physiological characterization of these mutants and of strains ectopically expressing Tes and Grs demonstrated the importance of tetraether lipids for thermophily and fitness in the extremes for T. kodakarensis while also revealing unexpected cyclization responses.

RESULTS

TK2145 and TK0167 encode the non-essential tetraether synthase (Tes) and GDGT-ring synthase (Grs), respectively.

Analyses of the lipidome of T. kodakarensis strains revealed the presence of membrane-spanning glycerol dibiphytanyl glycerol tetraethers (GDGTs) and a small percentage of cyclized GDGTs, thus predicting the presence of an active Tes and Grs (Fig. 2C–D & S2A). Based on homology with recently identified Tes enzymes (Zeng et al., 2019, 2022), TK2145 was predicted to encode the sole Tes homolog (1e−170 e-value, 45% identity) in T. kodakarensis (Tk-Tes); however, no biochemical or genetic evidence supporting TK2145 as Tk-Tes was previously reported. An unbiased mutagenesis of T. kodakarensis (Orita et al., 2019) revealed that inactivation of TK2145 resulted in reduced hyperthermotolerance in T. kodakarensis, but lipid analyses were not performed to confirm loss of GDGT production. The co-purification of the product of TK2145 with TK2140, a DNA ligase (Li et al., 2010), is the only other previous, and still unexplained, information on the role of the product of TK2145 in vivo. We also searched the T. kodakarensis genome for a potential Grs homolog and identified TK0167 as a strong candidate (8e−72 e-value, 32% identity to GrsA). Beyond basic transcriptomics (Jäger et al., 2014) or microarray data (Čuboňová et al., 2012) demonstrating expression of TK0167, no previous information on the role(s) of TK0167 has been reported.

Figure 2. Long-term survival of T. kodakarensis demands Tes (TK2145) catalyzed tetraether lipid production but not Grs (TK0167) catalyzed cyclization, .

(A) The genomic locus of TK0167, predicted to encode Tk-Grs (blue), shown with flanking genes (green) in the parental strain (TS559) (Top) and in the TK0167 partial deletion strain (Δgrs; AL010) (Bottom). (B) The genomic locus of TK2145, predicted to encode Tk-Tes (blue), shown with flanking genes (green) in the parental strain (TS559) (Top) and in the TK2145 deletion strain (Δtes; AL016) (Bottom). (C) LC-MS extracted ion chromatograms of one replicate of the acid hydrolyzed lipid extracts from the parent strain TS559, the Δtes strain, and the Δtes strain complemented with TK2145. GDGT production was lost upon deletion of Tk-Tes and restored with ectopic expression of TK2145. (D) LC-MS extracted ion chromatograms of one replicate of the acid hydrolyzed lipid extracts from the parent strain TS559, the Δgrs strain, and the Δgrs strain complemented with TK0167. Deletion of Tk-Grs resulted in the loss of cyclized GDGTs and cyclization was restored with ectopic expression of TK0167. (E and F) Exponential growth rates of T. kodakarensis at 85°C (E) and 95°C (F) are not significantly impacted by deletion of TK2145 (Tk-Tes; strain AL016) or TK0167 (Tk-Grs; AL010), however, deletion of Tk-Tes (TK2145) dramatically impacts survival upon entry into stationary phase.

To establish the potential roles of TK2145 and TK0167 in lipid production and maturation in T. kodakarensis, we individually targeted each locus for deletion with established genetic techniques (Liman et al., 2022) (Fig. 2A & B). While the entire open reading frame of TK2145 was deleted, a portion of TK0167 was intentionally not targeted for genomic deletion due to the presence of small RNA identified in our previous transcriptomic data that overlaps with TK0167 (Jäger et al., 2014). Deletion of TK2145 from the parental strain TS559 was successful (generating strain AL016; Δtes), as was the desired partial deletion of TK0167 (generating strain AL010; Δgrs) (Table 1). The exact endpoints of each markerless genomic deletion were confirmed first by PCR amplification of genomic regions and Sanger sequencing of amplicons, followed by whole genome sequencing, at >100X coverage for each strain (Fig. S1A & B). Total genome analyses of the Δtes and Δgrs strains confirmed deletion of the TK2145 and TK0167 sequences, respectively, and established that neither strain acquired any secondary mutations throughout the remainder of the genome.

Table 1.

T. kodakarensis strains used in this study

| Strain | Details | Source |

|---|---|---|

| TS559 | Parental Strain | Santangelo et al. (2010) |

| AL010 | TS559 ΔTK0167* | This study |

| AL016 | TS559 ΔTK2145 | This study |

| AL017 | TS559 + pTS543 | This study |

| AL018 | TS559 + pTS543-TK0167 | This study |

| AL019 | TS559 + pTS543-TK2145 | This study |

| AL020 | AL010 + pTS543 | This study |

| AL021 | AL010 + pTS543-TK0167 | This study |

| AL022 | AL016 + pTS543 | This study |

| AL023 | AL016 + pTS543-TK2145 | This study |

To confirm that deletion of putative Tes and Grs homologs abolished GDGT formation and cyclization, respectively, we carried out triplicate lipid analyses of the T. kodakarensis parental strain, TS559, and the Tk-Tes and Tk-Grs deletion strains grown to late-stationary phase at 85°C (Fig. 2C–D, 3C–D, 4C–D & S2A–B, & E). Freeze-dried biomass was acid hydrolyzed to generate core lipids, which lack headgroups, for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analyses and revealed the production of both tetraether and diether lipids (Fig. 2C–D & S2A). Archaeol (m/z = 653) production was observed in all three strains (Fig. 2C & S2A–B, & E), while the Δtes strain displayed a complete absence of all tetraether lipid species (m/z = 1304–1294) (Fig. 2C, S2B, & S3A–F); note that the trace for the Δtes strain is displayed at three orders of magnitude lower intensity, yet no signal indicative of GDGT-0 was observed. Complementation of the Δtes strain via ectopic expression of Tk-Tes restored GDGT-0 production (Fig. 2C & S2C & D) demonstrating that Tes activities are encoded at the TK2145 locus and that no other Tes activities exist within T. kodakarensis. The viability of the Tk-Tes mutant contrasts with the presumed essentiality of the S. acidocaldarius Tes (Zeng et al., 2019), suggesting that tetraether membranes may be more critical in some archaeal clades than others.

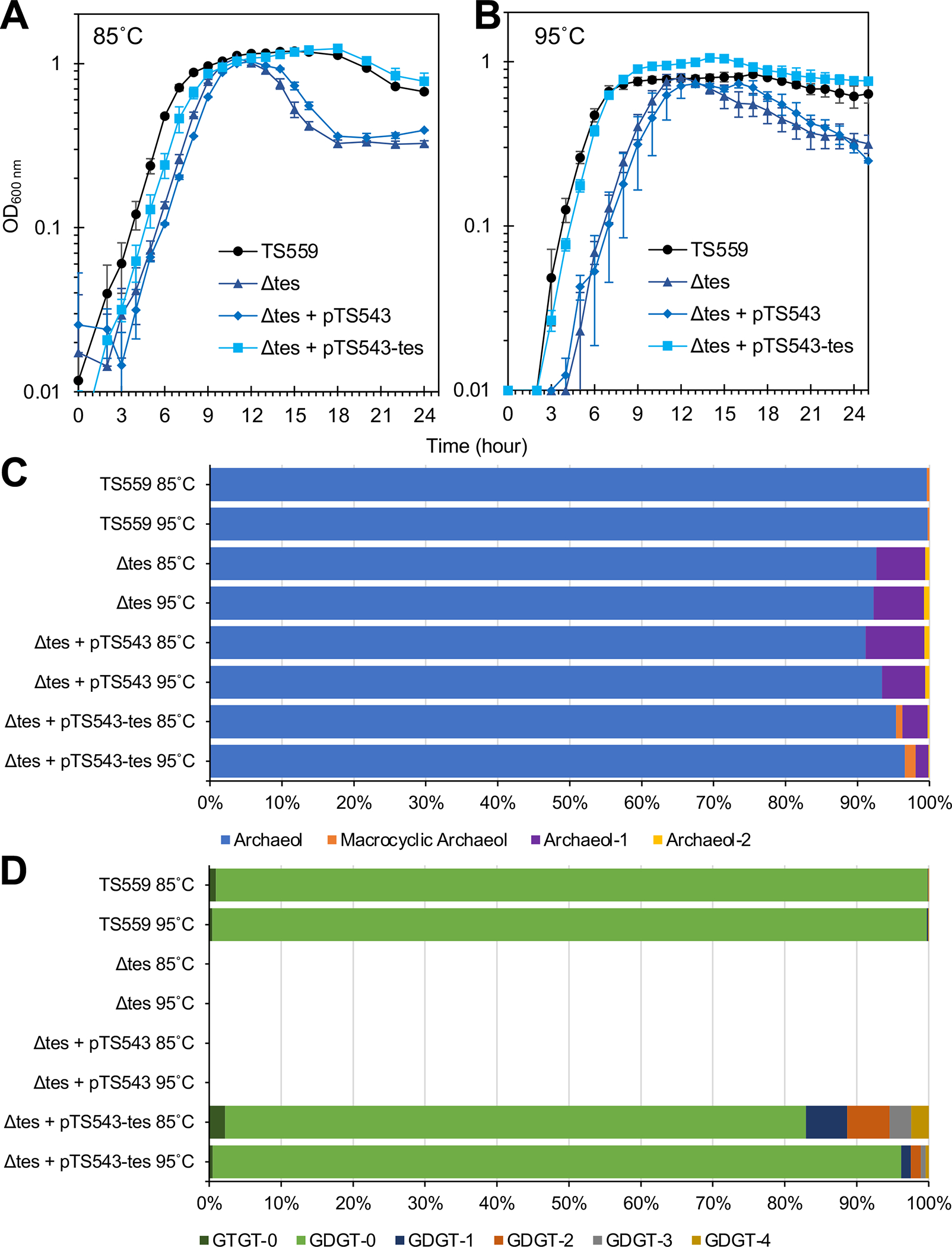

Figure 3. Loss of hyperthermophily due to loss of tetraether lipid synthesis is restored via ectopic complementation of Tk-Tes activities.

(A & B) The growth of triplicate biological cultures of T. kodakarensis strains TS559 (black), Δtes (dark blue), Δtes + pTS543 (blue), and pTS543 + pTS543-TK2145 (light blue) were monitored via changes in optical density (at 600nm) at 85°C and 95°C, respectively, revealing the rescue of reduced survival during transition to stationary phase due to the lack of Tk-Tes activities. (C & D) Lipid analyses of triplicate biological cultures of T. kodakarensis strains grown at 85°C and 95°C reveals that ectopic expression of Tk-Tes activities restores tetraether lipid synthesis to strains lacking TK2145 on the genome and an unanticipated increase in cyclized GDGTs. Panel C and D show diether and tetraether lipid production, respectively.

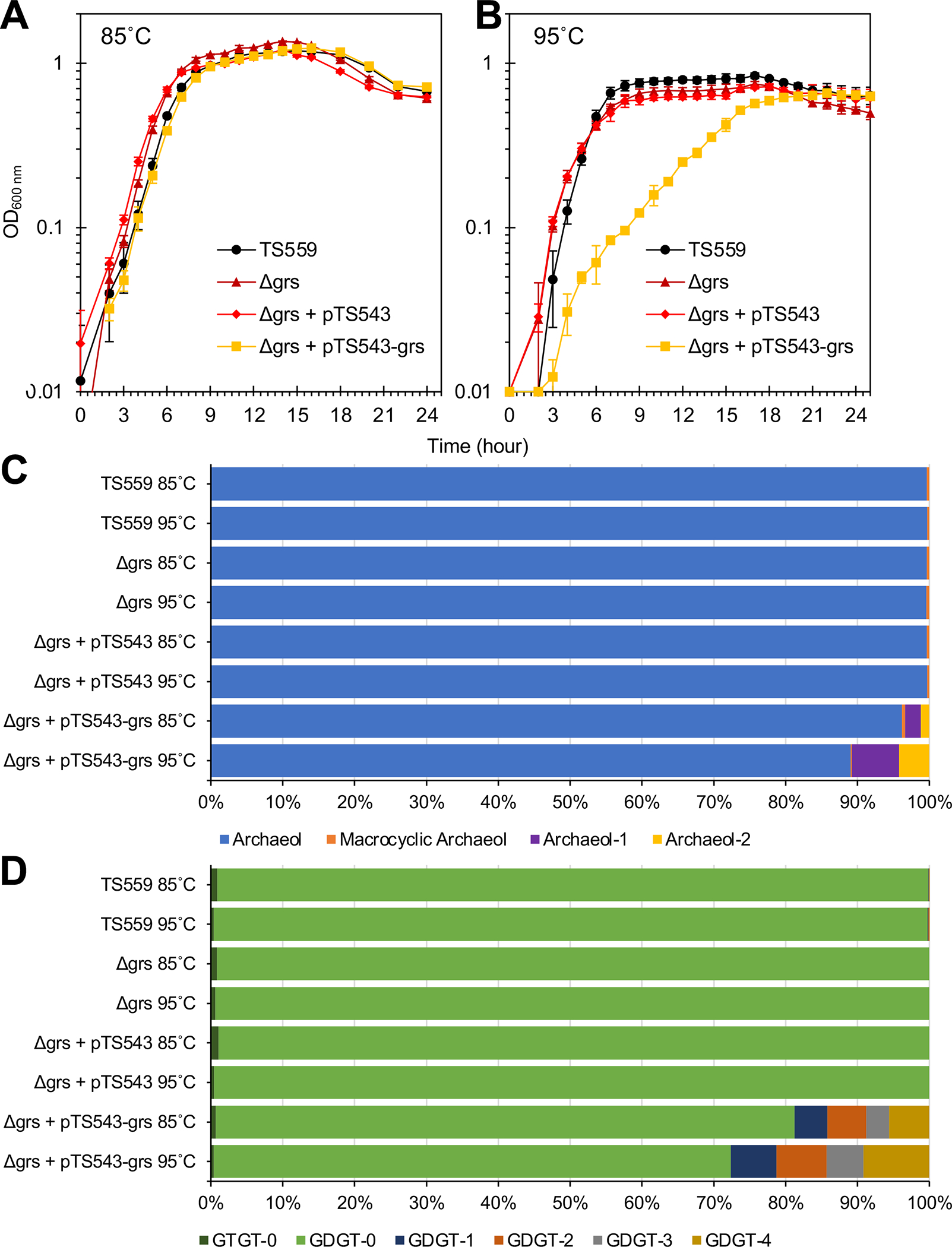

Figure 4. Dramatic increases in cyclized GDGTs from ectopic Tk-Grs expression coincide with growth defects at supra-optimal temperature.

(A & B) Triplicate biological cultures of T. kodakarensis strains TS559 (black), Δgrs (dark red), Δgrs + pTS543 (red), and Δgrs + pTS543-TK0167 (orange) were monitored for changes in optical density (at 600nm) at 85°C and 95°C, respectively. Ectopic expression of Tk-Grs (orange) resulted in impaired growth at 95°C. (C & D) Lipidome analyses of triplicate biological cultures of T. kodakarensis strains grown at 85°C and 95°C. Ectopic TK-Grs expression increases cyclized-GDGT levels ~50-fold (to ~20% of extracted core lipids). Panel C and D show diether and tetraether lipid production, respectively.

Lipid analyses of the parental strain TS559 revealed small amounts (<1% of all tetraether lipids) of GDGT-1, 2, 3, and 4 whereas the Tk-Grs deletion strain displayed a complete loss of cyclized GDGTs while archaeol and GDGT-0 remained present (Fig. 2D). Complementation via ectopic Grs (TK0167) expression restored cyclized GDGT production in the Δgrs strain (Fig. 2D & S2F & G) confirming that the TK0167 locus encodes Grs activity. The complete loss of GDGT-1, 2, 3, and 4 in the Δgrs strain also adumbrates that no redundant Grs activities are present in T. kodakarensis.

Lack of GDGTs impacts late stationary phase survival.

The biological importance of tetraether lipids has not previously been investigated in vivo due to the presumed essentiality of Tes (Zeng et al., 2022). Given the small percentage (~0.1%) of tetraethers that were cyclized in the parental strain, it was not surprising that deletion of Tk-Grs (strain AL010) did not result in a significant defect in growth rate or final cell densities at 85°C (optimal) or 95°C (supra-optimal, but tolerable) (Fig. 2E & F). In contrast, eliminating Tk-Tes (strain AL016) resulted in substantial impacts on survival upon transition from late-exponential phase to stationary phase (Fig. 2E & F). Aside from the slightly elongated lag phase, the rate of Δtes growth largely matched that of the parental strain TS559 at both optimal and supra-optimal growth temperatures. Whereas TS559 showed only minor reductions in optical density upon reaching stationary phase, suggestive of minor impacts to viability, the optical density of Δtes (AL016) drops significantly upon entry into stationary phase (Fig. 2E & F). These data imply that most (~50–75%) of the culture perishes in stationary phase due to the lack of tetraether lipids and provides in vivo evidence that tetraether lipids are necessary to promote viability in stationary phase T. kodakarensis cultures. Given the known volatile nature and ever-changing nutrient availability of hydrothermal vents, the fitness of T. kodakarensis strains lacking tetraether lipids pales in comparison to tetraether-containing strains in natural environments.

The rescued production of core tetraether lipids in the Tes mutant via ectopic Tk-Tes activities restored the decline in population density that was observed in the Δtes strain upon entry to stationary phase. Ectopic Tk-Tes expression completely restored growth phenotypes at both 85°C and 95°C (Fig. 3A & B). Our findings thus not only genetically confirm the function of TK2145 as a Tes, but also confirm the stationary phase phenotype of cells lacking Tk-Tes can be rescued through complementation.

Aberrant production of cyclized tetraether lipids dramatically impairs hyperthermophilic growth.

As less than 1% of GDGTs were cyclized in the parental strain TS559, we predicted that ectopic complementation of Tk-Grs might result in an overabundance of cyclic tetraethers, permitting evaluation of the impact of increased lipid rings on microbial fitness (Fig. 4 and S2A & G). We introduced an autonomously replicating plasmid (Santangelo et al., 2010) directing Grs expression from a strong promoter (Scott et al., 2021) into the parental strain TS559 and the Δgrs strain (Fig. 4 & S4); strains of TS559 and Δgrs retaining the same plasmid (pTS543) lacking the grs expression cassette were also generated as controls (Table 1).

As predicted, introduction of the Tk-Grs complementation vector (pTS543-TK0167) into the Δgrs strain not only restored the production of cyclized GDGTs but also dramatically increased cyclization. The Ring Index (RI) is defined as the weighted average of ring numbers in GDGT compounds (Zhang et al., 2016). We observed a massive increase in the RI from just 0.002 and 0.004 in TS559 at 85°C and 95°C, respectively, to 0.470 and 0.740 in the Δgrs strains complemented with ectopic Grs expression at 85°C and 95°C, respectively (Fig. 4D & S5, Table 2). Tk-Grs ectopic expression in the parental strain TS559 also dramatically shifted the lipid composition compared to the parental strain (Fig. S4C & D), increasing the average RI to 0.413 and 0.588 at 85°C and 95°C, respectively (Fig. S5). Thus, ectopic expression of Tk-Grs can result in strains where ~19–28% of the tetraether lipids are cyclized, providing a route to the large-scale production of cyclized GDGTs in T. kodakarensis (Figs. 4D & S4D). Additionally, when Tk-Grs is ectopically expressed in Δgrs at 60°C, an even greater average RI of 1.67 is observed and ~53% of the tetraether lipids are cyclized, indicating that GDGT cyclization has a complex relationship with temperature (Fig. S5 & S7A).

Table 2.

Core lipid analysis of all T. kodakarensis strains

| Strain | Details | 85˚C | 95˚C | Source | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archaeol | (s.d.) | MA | (s.d.) | Archaeol-1 | (s.d.) | Archaeol-2 | (s.d.) | GTGT-0 | (s.d.) | GDGT-0 | (s.d.) | GDGT-1 | (s.d.) | GDGT-2 | (s.d.) | GDGT-3 | (s.d.) | GDGT-4 | (s.d.) | Archaeol | (s.d.) | MA | (s.d.) | Archaeol-1 | (s.d.) | Archaeol-2 | (s.d.) | GTGT-0 | (s.d.) | GDGT-0 | (s.d.) | GDGT-1 | (s.d.) | GDGT-2 | (s.d.) | GDGT-3 | (s.d.) | GDGT-4 | (s.d.) | |||

| TS559 | Parental Strain | 2.16E-01 | 7.38E-02 | 8.14E-04 | 3.92E-04 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 7.24E-03 | 3.89E-03 | 7.75E-01 | 7.04E-02 | 5.26E-04 | 2.70E-04 | 4.26E-04 | 1.75E-04 | 5.69E-05 | 4.14E-05 | 3.89E-05 | 2.82E-05 | 2.96E-01 | 4.95E-02 | 8.30E-04 | 2.89E-04 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 2.88E-03 | 5.82E-04 | 6.98E-01 | 4.79E-02 | 9.93E-04 | 6.86E-04 | 5.71E-04 | 3.20E-04 | 1.01E-04 | 2.90E-05 | 9.74E-05 | 7.80E-05 | Santangelo et al. (2010) |

| AL010 | TS559 □TK0167* | 2.16E-01 | 7.31E-02 | 7.81E-04 | 4.66E-04 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 6.71E-03 | 5.69E-03 | 7.77E-01 | 6.87E-02 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 2.91E-01 | 1.12E-02 | 1.26E-03 | 2.54E-04 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 4.57E-03 | 1.25E-03 | 7.03E-01 | 1.02E-02 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | This study |

| AL016 | TS559 □TK2145 | 9.26E-01 | 1.74E-02 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 6.78E-02 | 1.59E-02 | 5.75E-03 | 1.58E-03 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 9.23E-01 | 5.11E-02 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 7.00E-02 | 4.57E-02 | 7.35E-03 | 5.43E-03 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | This study |

| AL017 | TS559 + pTS543 | 2.46E-01 | 1.01E-01 | 7.39E-04 | 2.61E-04 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 5.83E-03 | 3.45E-03 | 7.47E-01 | 9.80E-02 | 4.82E-04 | 1.67E-04 | 3.54E-04 | 8.09E-05 | 5.61E-05 | 4.02E-05 | 1.81E-05 | 2.56E-05 | 3.26E-01 | 3.23E-02 | 1.26E-03 | 4.65E-04 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 3.50E-03 | 7.31E-04 | 6.67E-01 | 3.44E-02 | 1.51E-03 | 1.33E-03 | 8.59E-04 | 6.61E-04 | 1.67E-04 | 1.09E-04 | 1.56E-04 | 1.85E-04 | This study |

| AL018 | TS559 + pTS543- TK0167 | 2.17E-01 | 6.30E-02 | 8.05E-04 | 3.95E-04 | 4.57E-03 | 2.23E-03 | 2.94E-03 | 1.48E-03 | 5.04E-03 | 2.26E-03 | 6.31E-01 | 5.11E-02 | 4.04E-02 | 5.99E-03 | 4.43E-02 | 7.05E-03 | 2.28E-02 | 2.16E-03 | 3.01E-02 | 3.40E-03 | 2.41E-01 | 3.31E-02 | 5.30E-04 | 3.88E-04 | 8.55E-03 | 5.79E-03 | 6.21E-03 | 4.83E-03 | 2.22E-03 | 8.84E-04 | 5.56E-01 | 9.46E-02 | 5.06E-02 | 3.02E-02 | 5.65E-02 | 3.61E-02 | 3.37E-02 | 2.07E-02 | 4.44E-02 | 3.01E-02 | This study |

| AL019 | TS559 + pTS543- TK2145 | 1.55E-01 | 7.83E-02 | 1.58E-02 | 9.21E-03 | 1.09E-03 | 4.08E-04 | 1.30E-04 | 1.13E-04 | 1.99E-03 | 1.01E-03 | 8.20E-01 | 8.54E-02 | 2.12E-03 | 7.04E-04 | 2.42E-03 | 5.87E-04 | 1.05E-03 | 3.71E-04 | 8.81E-04 | 2.22E-04 | 1.22E-01 | 2.69E-02 | 6.54E-03 | 1.93E-03 | 1.06E-03 | 1.13E-03 | 1.38E-04 | 1.14E-04 | 5.42E-04 | 9.37E-05 | 8.64E-01 | 3.02E-02 | 2.46E-03 | 1.94E-03 | 2.02E-03 | 1.39E-03 | 7.13E-04 | 5.11E-04 | 5.91E-04 | 4.02E-04 | This study |

| AL020 | AL010 + pTS543 | 2.65E-01 | 1.37E-01 | 9.58E-04 | 7.45E-04 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 7.94E-03 | 4.84E-03 | 7.26E-01 | 1.34E-01 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 2.29E-01 | 4.09E-02 | 7.32E-04 | 2.32E-04 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 3.58E-03 | 1.48E-04 | 7.67E-01 | 4.10E-02 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | This study |

| AL021 | AL010 + pTS543- TK0167 | 2.18E-01 | 7.42E-02 | 9.50E-04 | 4.95E-04 | 5.01E-03 | 1.68E-03 | 2.65E-03 | 7.43E-04 | 5.39E-03 | 4.20E-03 | 6.22E-01 | 4.56E-02 | 3.55E-02 | 1.13E-02 | 4.18E-02 | 1.12E-02 | 2.45E-02 | 5.76E-03 | 4.32E-02 | 1.11E-02 | 2.33E-01 | 4.18E-02 | 4.74E-04 | 3.35E-04 | 1.72E-02 | 1.18E-02 | 1.11E-02 | 7.94E-03 | 3.08E-03 | 9.85E-04 | 5.30E-01 | 1.51E-01 | 4.70E-02 | 2.06E-02 | 5.13E-02 | 3.06E-02 | 3.76E-02 | 2.45E-02 | 6.77E-02 | 5.06E-02 | This study |

| AL022 | AL016 + pTS543 | 9.12E-01 | 2.82E-03 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 8.16E-02 | 2.15E-03 | 6.86E-03 | 7.02E-04 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 9.34E-01 | 3.79E-02 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 6.02E-02 | 3.41E-02 | 5.93E-03 | 3.86E-03 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | This study |

| AL023 | AL016 + pTS543- TK2145 | 4.01E-01 | 2.29E-01 | 3.63E-03 | 2.54E-03 | 1.47E-02 | 9.13E-03 | 1.06E-03 | 8.30E-04 | 1.30E-02 | 7.94E-03 | 4.68E-01 | 1.89E-01 | 3.32E-02 | 1.47E-02 | 3.42E-02 | 1.63E-02 | 1.74E-02 | 8.18E-03 | 1.42E-02 | 6.62E-03 | 2.39E-01 | 4.01E-02 | 3.73E-03 | 1.09E-03 | 4.32E-03 | 3.75E-03 | 4.09E-04 | 3.71E-04 | 3.49E-03 | 8.80E-04 | 7.20E-01 | 5.09E-02 | 1.02E-02 | 6.70E-03 | 1.05E-02 | 5.94E-03 | 4.86E-03 | 3.04E-03 | 3.37E-03 | 2.28E-03 | This study |

| Strain | Details | 60˚C | Source | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Archaeol | (s.d.) | MA | (s.d.) | Archaeol-1 | (s.d.) | Archaeol-2 | (s.d.) | GTGT-0 | (s.d.) | GDGT-0 | (s.d.) | GDGT-1 | (s.d.) | GDGT-2 | (s.d.) | GDGT-3 | (s.d.) | GDGT-4 | (s.d.) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| AL010 | TS559 □TK0167* | 4.07E-01 | 2.95E-02 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 7.03E-03 | 6.02E-04 | 5.86E-01 | 2.93E-02 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | This study | ||||||||||||||||||||

| AL021 | AL010 + pTS543- TK0167 | 3.71E-01 | 9.30E-03 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 2.21E-01 | 6.16E-03 | 1.66E-01 | 9.65E-03 | 2.00E-03 | 2.23E-04 | 1.12E-01 | 8.17E-03 | 1.63E-02 | 1.84E-03 | 2.12E-02 | 1.58E-03 | 2.07E-02 | 2.04E-03 | 6.98E-02 | 2.04E-03 | This study | ||||||||||||||||||||

The increased relative abundance of cyclized GDGTs in the parental and Δgrs strains ectopically expressing Tk-Grs is not benign and results in substantial defects at increased growth temperatures (Fig. 4A & B, S4A & B). While increased Grs activities throughout the growth cycle are tolerated without significant impact at the optimal growth temperature of 85°C, ectopic expression of Tk-Grs at 95°C dramatically slows growth, although final cell densities matching parental strains are eventually achieved (Fig. 4A & B, S4A & B). Thus, while an increase in the proportion of GDGTs that are cyclized from natural levels of ~0.1% to ~19% is well-tolerated at 85°C, near identical increases from ~0.3% to ~28% at 95°C results in dramatic fitness consequences (Fig. 4B & S4B). It will be of interest to determine how increases in cyclized GDGTs change key parameters of membrane biology (e.g., stability, fluidity, and permeability) in T. kodakarensis that result in impaired growth rates at supra-optimal temperatures.

Disruption of native Tk-Tes or Tk-Grs activity results in unexpected lipid composition changes.

As expected, the complete loss of GDGTs in the Δtes strain results in a membrane composed of only diether lipids. However, unexpectedly, we found that the Δtes strain is capable of cyclizing these diether lipids, producing putative ring containing derivatives of archaeol, here termed archaeol-1 and archaeol-2 with one and two rings, respectively (Fig. 1, 3C, & S6A–D, Table 2), supported by mass spectra and hydrogenation experiments described later in the text. In the absence of its presumed natural GDGT substrates, Tk-Grs uses archaeol as a substrate, resulting in the Δtes strain converting ~7% of its diether lipids to archaeol-1 and archaeol-2 at both 85°C and 95°C (Fig. 3C and Table 2). The significance of newly cyclized archaeols is emphasized by the fact that the cyclized diethers in Δtes are ~70-fold higher (~7% of core diethers) than the abundance of all cyclized tetraethers (~0.1% of core tetraethers) in the parental strain TS559 (Fig. 3C & D).

Archaeol-1 and archaeol-2 were also detected in strains ectopically expressing Tk-Grs where ~3% and 11% of the core diether lipids were cyclized at 85°C and 95°C, respectively (Fig. 4C & S6E & F). Growth of the Δgrs complementation strain (Δgrs + pTS543-grs) at 60°C resulted in the robust production of archaeol-1 and -2, together accounting for ~51% of the total core diether lipids while archaeol-1 and -2 were completely absent in the Δgrs strain (Fig. S7B & C). The high levels of these cyclized diether lipids allowed for their characterization via gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), following trimethylsilylation (TMS) derivatization. This analysis revealed the presence of two chromatographically separated archaeol-1 isomers (termed archaeol-1a and -1b) and three chromatographically separated archaeol-2 isomers (termed archaeol-2a, -2b, and -2c) with nearly identical electron impact (EI) mass spectra (Fig. S7D, S9, & S10). EI mass spectra of TMS-archaeol (Fig. S8) in these samples closely matched that in Dawson et al. (Dawson et al., 2012); however, mass spectra of both TMS-archaeol-1 isomers differed from archaeol with a single double bond (Fig. S9, S14, & S15 and Fig. 2B in Dawson et al.). Further, hydrogenation of acid-hydrolyzed total lipid extracts containing archaeol-1 and -2 demonstrated that these lipids are immune to hydrogenation and thus do not contain double bonds but instead contain rings (Fig. S16A–C). This hydrogenation experiment, in combination with 1) the observed mass spectra, 2) the delayed elution times of archaeol-1 and -2 compared to archaeol (Fig S7C), typical of ring-bearing but not double bond possessing derivatives that elute earlier (Fig. S16B & C) (Liu et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2013), and 3) the robust production of these lipids when ectopically expressing Tk-Grs (Fig. S7C), strongly supports that archaeol-1 and archaeol-2 contain cyclopentane rings within their C-20 isoprenoid chains (Fig. 1). (Liu et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2013)

Further, our analyses reveal that two regioisomers of archaeol-1 are possible; these are isomers that differ by which tail the ring is placed in – either the C3 glycerol bonded tail or the C2 glycerol bonded tail (Fig. S9). The EI mass spectra of both TMS-archaeol-1a and TMS-archaeol-1b reveals that both isomers are actually a mixture of the two regioisomers as demonstrated by the co-occurrence of the m/z = 307, 412 fragment ion pair and the m/z = 309, 410 fragment ion pair in the same mass spectrum, each pair resulting from the C2-C3 glycerol bond cleavage of a different regioisomer (Fig. S9, S14, & S15). However, the m/z = 307, 412 fragment ion pair is dominant over the m/z = 309, 410 pair, indicating that the ring is more commonly found in the C3 glycerol bonded tail (tail furthest from the headgroup) and suggesting that Tk-Grs prefers to cyclize at this location first (Fig. S9, S14, & S15).

The restoration of Tk-Tes activities in the Δtes complementation strain also resulted in unexpected changes to the lipidome. As expected, restoring Tk-Tes expression and activities via ectopic expression in the Δtes strain restored production of GDGT-0 (Fig. 3D). Surprisingly, ectopic expression of Tk-Tes also resulted in an increased abundance of GDGT-1, 2, 3, and 4 with an average ring index of 0.358 at 85°C. This was similar to that of strains ectopically expressing Tk-Grs at 85°C (Δgrs + pTS543-grs RI = 0.470 and TS559 + pTS543-grs RI = 0.413), although this increased cyclization was much less at 95°C with an RI of just 0.080 (Fig. S5). An increase in the average RI was also observed for the parent strain (TS559) overexpressing Tk-Tes. However, the RI increase is much lower at both 85°C (RI = 0.016) and 95°C (RI = 0.013) than in the complementation strain but still an increase as compared to 0.002 and 0.004 in the parental strain at 85°C and 95°C, respectively (Fig. S5). These findings indicate that the activities of Grs, which may be temperature-regulated, are impacted by the ectopic expression of Tes.

DISCUSSION

Like all archaea, T. kodakarensis generates an isoprenoid-based lipid membrane that responds to environmental and growth phase changes. Instead of a conventional bilayer, the membranes of many archaea are dominated by membrane-spanning tetraether lipids termed GDGTs that are synthesized by the activities of a tetraether lipid synthase (Tes) (Lloyd et al., 2022; Zeng et al., 2022). GDGTs can be modified through the formation of ring structures within the dibiphytanyl tails by the activity of GDGT-ring synthase (Grs) (Zeng et al., 2019). Ring-containing lipids are typically only minor constituents of the total lipidome of the Thermococcales (Tourte et al., 2020) but can be the dominant membrane lipids in other Archaea including Thaumarchaeota (Pitcher et al., 2009), Sulfolobales (Jensen et al., 2015), and Thermoplasmatales (Uda et al., 2004) species. Cyclized GDGTS are thought to impart unique properties to membranes that support survival in the extremes (Matsuno et al., 2009; Meador et al., 2014; Tierney & Tingley, 2015; Van de Vossenberg et al., 1998b, 1998a; Zhou et al., 2020) but the synthesis, modification, and impacts of such on hyperthermophily are understudied in vivo.

In this study, we established that T. kodakarensis strains lacking the tetraether synthase Tes (TK2145) are viable despite the complete lack of tetraether lipids. The hyperthermophilic growth of T. kodakarensis is thus not dependent on tetraether lipids, although the lack of tetraether lipid synthesis leads to a dramatic loss of viability upon entry into the stationary phase. In the absence of natural GDGT substrates in the T. kodakarensis Δtes deletion strain, the GDGT cyclase Grs instead modifies ~7% of archaeol to mono- or di-ring containing compounds (archaeol-1 and archaeol-2; Fig. 1) that may assist in preserving lipid membrane integrity and function in the absence of tetraether lipids. Deletion of Grs (TK0167) eliminates the production of the small (<1%) percentage of cyclic GDGTs found in natural membranes and is generally not phenotypic. While loss of ring-containing GDGTs is fitness-neutral under laboratory conditions, aberrant levels of ring-containing GDGTs are not well tolerated at supra-optimal growth temperatures upon overexpression of Grs in vivo. Overproduction of Grs throughout all growth phases does provide a route to abundant (~53%, 19%, and 28% of tetraether lipids at 60°C, 85°C, and 95°C, respectively) ringed-GDGT production, but these high levels of derivatized GDGTs led to significant growth defects at 95°C. Furthermore, the effects of temperature on cyclization appear to be complex, as increased levels of cyclized GDGTs are observed at both supra-optimal (95°C) and sub-optimal (60°C) temperatures. While increases in cyclized GDGTs in response to increased temperature have been well documented in many archaea, other physiological factors known to influence GDGT cyclization, such as growth rate, also change with temperature and thus may have confounding effects on cyclization levels. Alternatively, the turnover of cyclized GDGTs could be reduced at suboptimal growth temperatures, or Tk-Grs may simply function more efficiently under such conditions. Taken together, our findings show the importance of tetraether lipid synthesis in the long-term survival of T. kodakarensis. The regulation of lipid composition appears to be critical for both archaeal hyperthermophily and growth phase transitions. It is also likely that combinatorial changes to environmental variables (e.g., temperature, salinity, pressure, and pH) will also direct changes to the lipidome that will reveal other critical roles for tetraether lipids and their cyclized derivatives.

Our findings also demonstrate the production of new lipid types, specifically archaeol-1 and archaeol-2. While macrocyclic archaeol containing one and two rings has been observed in environmental lipid extracts (Stadnitskaia et al., 2003), the presence of rings in archaeol and cyclized diether lipids in culture have not been previously observed. Tk-Grs appears to be promiscuous, allowing the production of cyclized diethers when ectopically expressed throughout the growth phases, especially at 60°C where they comprise half of the diether lipids, interestingly equal to the proportion of GDGTs cyclized at this temperature. This suggests that Tk-Grs can work equally well on both diether and tetraether lipids under certain conditions.

The mass spectra of the two archaeol-1 isomers provide further biochemical insights into Tk-Grs function. Fragmentation patterns demonstrate that Tk-Grs can form the first ring in either lipid tail but that it prefers to do so on the tail furthest from the headgroup. Additionally, the presence of multiple chromatographically resolved isomers of archaeol-1 and -2 has interesting implications for our understanding of the stereochemistry of the ring moieties in archaeal lipids (Fig. S11A & B, S12A–E). While the observed isomers of archaeol-1 and -2 could in theory be the result of different ring shapes (e.g., cyclohexane) or cyclization at different positions along the phytanyl tail (e.g., at C-3), no biochemical precedence exists for such multifaceted activity of Grs. Further, we 1) do not observe LC chromatographic resolution of the isomers that would suggest varying ring shapes (Liu et al., 2016), 2) do not detect the presence of archaeol with more than 2 rings (possible if C3 and C7 cyclization occurs), and 3) do not detect fragments in the mass spectra of the archaeol-2 isomers that would indicate that the two rings can be found together on one tail. Thus, we hypothesize that the different isomers of archaeol-1 and -2 are diastereomers of one another, differing in their stereochemistry around the cyclopentane ring (cis vs. trans configuration) (Fig. S11A & B, S12A–E). Previous studies have determined that the stereochemistry of the cyclopentane rings in GDGTs from S. acidocaldarius (Montenegro et al., 2003), crenarchaeol from Thaumarchaeota (Holzheimer et al., 2021), and environmental GDGT-derived compounds (Lutnaes et al., 2006) appears to be exclusively trans, particularly with a C7(S)-C10(S) configuration. However, one notable exception is the potential presence of a cis-configured cyclopentane ring in the enigmatic crenarchaeol isomer (Sinninghe Damsté et al., 2018). Thus, it is unclear if the suggested additional stereoisomers of archaeol-1 and archaeol-2 are merely artifacts of the “unnatural” cyclization of archaeol or if they are indicative of the stereochemistry of the rings in the GDGTs of T. kodakarensis as well. Given the demands for biological routes for large-scale production of derivatized GDGTs (Jia et al., 2022; Lilia Romero & Jose Morilla, 2023; Santhosh & Genova, 2022), strains that express wildtype and potential-variant forms of Grs hold substantial promise.

Rescued recovery of GDGT synthesis via ectopic Tk-Tes expression in genomically-deleted Tes strains also reproducibly increases the total amount of cyclic GDGTs observed in comparison to the overexpression of Tk-Tes in the parental strain. Based on previous T. kodakarensis transcriptomic data, Tk-Tes (encoded by TK2145) is co-expressed with TK2146, which is annotated as a hypothetical regulatory protein. Perhaps the co-expression of Tes and TK2146 in the parental strain but not in the Δtes strain played a role in the regulation of cyclopentane ring production in T. kodakarensis. These findings ultimately warrant more investigation into the main regulatory pathway that controls the production of cyclic GDGTs.

In conclusion, the ability to manipulate lipidome composition in T. kodakarensis offers a powerful mechanism to study the impacts of tetraether lipid biosynthesis on archaeal physiology and survival in the extremes. Investigations into the interplay between GDGT biosynthesis, modification, and cellular viability in different environments will allow a better understanding of the roles of these tetraether lipids in the evolution of archaeal organisms. Although the properties of these new lipids still require further investigation, the expansion and control of lipid diversity in T. kodakarensis can be utilized for biotechnology applications in relation to drug deliveries and vaccines.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

Microbial growth and media conditions

The constructed strains of T. kodakarensis were anaerobically cultured as previously described in artificial sea water (ASW) media supplemented with 5 g/l tryptone, 5 g/l yeast extract, 5 g/l pyruvate, 2 g/l elemental sulfur (S°), and a KOD1-vitamin mixture with or without 1 mM agmatine (Liman et al., 2022). Culture growth at 85°C or 95°C was monitored using optical density measurements at 600 nm. Growth rates of a minimum of three independent biological replicates were monitored and plotted for each strain. Biomass harvested for lipid extractions and analyses were either grown at 85°C or 95°C and harvested 24 hours post-inoculum (late-stationary phase) and stored frozen (at −80°C or on dry ice) until sample processing for lipid extraction.

T. kodakarensis strain constructions

Strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All T. kodakarensis deletion strains were constructed via homologous recombination resulting in markerless deletions on the genome as previously described (Liman et al., 2022). Deletion strain genotypes were confirmed through whole genome sequencing (WGS) at >100x coverage using Oxford Nanopore MinION sequencing and visualized using Integrative Genomics Viewer. Complemented strains were constructed as previously described (Santangelo et al., 2010; Scott et al., 2021). Briefly, strains carrying the expression vectors were selected based on agmatine autotrophy and cultured without agmatine supplementation. Retention of expression plasmids were confirmed via PCR using primers flanking the insertion site of the gene of interest.

Lipid extraction and analyses

Frozen biomass samples were freeze-dried, resuspended in methanol (MeOH), and transferred to glass tubes where the solvent was evaporated under a N2 stream. Samples were acid hydrolyzed in 2 mL 1 M HCl in MeOH for 3 hours at 90°C before being neutralized by addition of 1 mL 2 M KOH in MeOH and diluted with 5 mL of deionized water. Samples were extracted three times with 5 mL dichloromethane (DCM) which was pooled and evaporated under a N2 stream. Samples were then resuspended in 1 mL of 9:1 MeOH:DCM and filtered through 0.45-μm polytetrafluoroethylene filters.

Core lipids were analyzed on an Agilent 1260 Infinity II series high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) instrument coupled to an Agilent G6125B single quadrupole mass spectrometer with the electrospray ionization (ESI) interface in positive mode. ESI-MS conditions were as follows: drying gas temperature 300°C, drying gas flow rate 8.0 L/min, nebulizer pressure 35 psi, capillary voltage 3500 V, and fragmentor voltage 175 V in scanning mode with a range of m/z = 600–1400.

Core lipids were separated with reverse phase chromatography on a Kinetex 1.7 μm XB-C18 100 Å LC column (150 × 2.1 mm) by a method modified from Rattray and Smittenberg (Rattray & Smittenberg, 2020) with mobile phase A: MeOH with 0.04% formic acid and 0.03% NH3 and mobile phase B: isopropanol with 0.04% formic acid and 0.03% NH3. An initial mobile phase of 60A:40B was held for 1 minute and then linearly ramped to 50A:50B over 19 minutes. This composition was held for 15 minutes and then linearly ramped back to 60A:40B over 5 minutes which was then held for 10 minutes to allow for re-equilibration. A large injection volume of 25 μL was used to detect all compounds of interest. Compounds were identified by the mass of the protonated parent ion ([M+H]+) coupled with comparison of elution times to laboratory standards or to those found in previous literature (Rattray & Smittenberg, 2020). The non-response factor corrected relative intensities of compounds were calculated using the manually integrated peak areas of the [M+H]+ ions only.

For gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis of diether lipids, acid hydrolyzed lipid extracts were trimethylsilyl (TMS) derivatized in 100 μL of a 1:1 solution of [pyridine]: [N,O-Bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) with 1% trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS)] for 1 hour at 70°C. 5 μL of the resulting reaction mixture was immediately injected on the GC-MS for analysis.

Diether lipids were analyzed on an Agilent 7890B Series GC instrument coupled to an Agilent 5977A Series MSD in EI mode at 70 eV, scanning over a range of m/z = 50 – 900. Lipids were separated on two Agilent DB-17HT columns (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.15 μm film thickness) connected in series using helium as the carrier gas with a constant flow rate of 1.1 mL/min. GC conditions were as follows: 60°C to 200°C at 10 degrees/min, then 200°C to 300°C at 4 degrees/min, and finally held at 300°C for 60 minutes.

Culture of Halorubrum lacusprofundi and Base Hydrolysis of Biomass

Liquid cultures (75 mL) of H. lacusprofundi DSM 5036 were grown on DSMZ Medium 372 at 10 °C, shaking for five months. H. lacusprofundi biomass was base hydrolyzed in 2 mL 1M KOH in MeOH for 3 hours at 70 °C. Reactions were neutralized with 1 mL 2M HCl in MeOH. The core lipids were then extracted and analyzed as described for T. kodakarensis.

Lipid sample hydrogenation

The lipid extract was resuspended in 2 mL of 1:1 MeOH:ethyl acetate (EtOAc). Argon was bubbled through the solution for 10 min before platinum(IV) oxide (~15 mg, 66 μmol) was added. The reaction mixture was placed in a Parr pressure vessel which was then pressurized to 60 psi with H2, and the reaction mixture was continuously stirred with magnetic stir bars. After 16 hours, the pressure was released, and argon was bubbled through the reaction for 10 min. The reaction was then filtered through celite with additional portions of EtOAc and then concentrated under vacuum.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research efforts at CSU were supported with funding (to TJS) from the National Science Foundation, grants 2016857 and 2022065, the US Department of Energy, grant DE-SC0014597, the USA National Institutes of Health, GM100329 and GM143963, and from the USA National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Exobiology program, 80NSSC20K0613. AAG and PVW were supported with funding from the Simons Foundation, award 735931.

Footnotes

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

FOR REVIEWERS ONLY

Whole genome sequencing data has been deposited into NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1022152. The raw sequencing data will be freely accessible upon publication. The following reviewer link is provided for verification: https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1022152?reviewer=sddubj7rutlsfoteg5l77o5h4i

References

- Čuboňová L, Katano M, Kanai T, Atomi H, Reeve JN, & Santangelo TJ (2012). An Archaeal Histone Is Required for Transformation of Thermococcus kodakarensis. Journal of Bacteriology, 194(24), 6864. 10.1128/JB.01523-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson KS, Freeman KH, & Macalady JL (2012). Molecular characterization of core lipids from halophilic archaea grown under different salinity conditions. Organic Geochemistry, 48, 1–8. 10.1016/J.ORGGEOCHEM.2012.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elling FJ, Könneke M, Lipp JS, Becker KW, Gagen EJ, & Hinrichs KU (2014). Effects of growth phase on the membrane lipid composition of the thaumarchaeon Nitrosopumilus maritimus and their implications for archaeal lipid distributions in the marine environment. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 141, 579–597. 10.1016/J.GCA.2014.07.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holzheimer M, Sinninghe Damsté JS, Schouten S, Havenith RWA, Cunha AV, & Minnaard AJ (2021). Total Synthesis of the Alleged Structure of Crenarchaeol Enables Structure Revision**. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition, 60(32). 10.1002/anie.202105384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley SJ, Elling FJ, Könneke M, Buchwald C, Wankel SD, Santoro AE, Lipp JS, Hinrichs KU, & Pearson A (2016). Influence of ammonia oxidation rate on thaumarchaeal lipid composition and the TEX86 temperature proxy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(28), 7762–7767. 10.1073/PNAS.1518534113/SUPPL_FILE/PNAS.1518534113.SAPP.PDF [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäger D, Förstner KU, Sharma CM, Santangelo TJ, & Reeve JN (2014). Primary transcriptome map of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis. BMC Genomics, 15, 684. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen SM, Neesgaard VL, Skjoldbjerg SLN, Brandl M, Ejsing CS, & Treusch AH (2015). The effects of temperature and growth phase on the lipidomes of Sulfolobus islandicus and Sulfolobus tokodaii. Life, 5(3). 10.3390/life5031539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Agbayani G, Chandan V, Iqbal U, Dudani R, Qian H, Jakubek Z, Chan K, Harrison B, Deschatelets L, Akache B, & McCluskie MJ (2022). Evaluation of Adjuvant Activity and Bio-Distribution of Archaeosomes Prepared Using Microfluidic Technology. Pharmaceutics 2022, Vol. 14, Page 2291, 14(11), 2291. 10.3390/PHARMACEUTICS14112291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga Y (2014). From promiscuity to the lipid divide: On the evolution of distinct membranes in archaea and bacteria. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 78(3–4), 234–242. 10.1007/S00239-014-9613-4/FIGURES/3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Santangelo TJ, Čuboňová L, Reeve JN, & Kelman Z (2010). Affinity purification of an archaeal DNA replication protein network. MBio, 1(5), 221–231. 10.1128/MBIO.00221-10/ASSET/2A5C2029-2319-443B-BCFE-DFDFDCAB2AC6/ASSETS/GRAPHIC/MBO0041010510003.JPEG [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilia Romero E, & Jose Morilla M (2023). Ether lipids from archaeas in nano-drug delivery and vaccination. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 634, 122632. 10.1016/J.IJPHARM.2023.122632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liman GLS, Stettler ME, & Santangelo TJ (2022). Transformation Techniques for the Anaerobic Hyperthermophile Thermococcus kodakarensis. Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.J.), 2522, 87. 10.1007/978-1-0716-2445-6_5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XL, De Santiago Torio A, Bosak T, & Summons RE (2016). Novel archaeal tetraether lipids with a cyclohexyl ring identified in Fayetteville Green Lake, NY, and other sulfidic lacustrine settings. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry : RCM, 30(10), 1197–1205. 10.1002/RCM.7549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd CT, Iwig DF, Wang B, Cossu M, Metcalf WW, Boal AK, & Booker SJ (2022). Discovery, structure and mechanism of a tetraether lipid synthase. Nature, 609(7925), 197. 10.1038/S41586-022-05120-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutnaes BF, Brandal Ø, Sjöblom J, & Krane J (2006). Archaeal C80 isoprenoid tetraacids responsible for naphthenate deposition in crude oil processing. Organic and Biomolecular Chemistry, 4(4). 10.1039/b516907k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumi R, Atomi H, Driessen AJM, & van der Oost J (2011). Isoprenoid biosynthesis in Archaea – Biochemical and evolutionary implications. Research in Microbiology, 162(1), 39–52. 10.1016/J.RESMIC.2010.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuno Y, Sugai A, Higashibata H, Fukuda W, Ueda K, Uda I, Sato I, Itoh T, Imanaka T, & Fujiwara S (2009). Effect of Growth Temperature and Growth Phase on the Lipid Composition of the Archaeal Membrane from Thermococcus kodakaraensis. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 73(1), 104–108. 10.1271/BBB.80520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador TB, Gagen EJ, Loscar ME, Goldhammer T, Yoshinaga MY, Wendt J, Thomm M, & Hinrichs KU (2014). Thermococcus kodakarensis modulates its polar membrane lipids and elemental composition according to growth stage and phosphate availability. Frontiers in Microbiology, 5(JAN). 10.3389/FMICB.2014.00010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merino N, Aronson HS, Bojanova DP, Feyhl-Buska J, Wong ML, Zhang S, & Giovannelli D (2019). Living at the extremes: Extremophiles and the limits of life in a planetary context. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10(MAR), 780. 10.3389/FMICB.2019.00780/BIBTEX [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro E, Gabler B, Paradies G, Seemann M, & Helmchen G (2003). Determination of the configuration of an Archaea membrane lipid containing cyclopentane rings by total synthesis. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition, 42(21). 10.1002/anie.200250629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orita I, Futatsuishi R, Adachi K, Ohira T, Kaneko A, Minowa K, Suzuki M, Tamura T, Nakamura S, Imanaka T, Suzuki T, & Fukui T (2019). Random mutagenesis of a hyperthermophilic archaeon identified tRNA modifications associated with cellular hyperthermotolerance. Nucleic Acids Research, 47(4), 1964. 10.1093/NAR/GKY1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher A, Rychlik N, Hopmans EC, Spieck E, Rijpstra WIC, Ossebaar J, Schouten S, Wagner M, & Damsté JSS (2009). Crenarchaeol dominates the membrane lipids of Candidatus Nitrososphaera gargensis, a thermophilic Group I.1b Archaeon. The ISME Journal 2009 4:4, 4(4), 542–552. 10.1038/ismej.2009.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin W, Carlson LT, Armbrust EV, Devol AH, Moffett JW, Stahl DA, & Ingalls AE (2015). Confounding effects of oxygen and temperature on the TEX86 signature of marine Thaumarchaeota. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(35), 10979–10984. 10.1073/PNAS.1501568112/SUPPL_FILE/PNAS.1501568112.SAPP.PDF [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattray JE, & Smittenberg RH (2020). Separation of Branched and Isoprenoid Glycerol Dialkyl Glycerol Tetraether (GDGT) Isomers in Peat Soils and Marine Sediments Using Reverse Phase Chromatography. Frontiers in Marine Science, 7. 10.3389/fmars.2020.539601 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo TJ, Čuboňová L, & Reeve JN (2010). Thermococcus kodakarensis Genetics: Tk1827-encoded β-glycosidase, new positive-selection protocol, and targeted and repetitive deletion technology. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 76(4), 1044–1052. 10.1128/AEM.02497-09/SUPPL_FILE/AEM02497_SUPPLEMENTARY_FIGS_2.PDF [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhosh PB, & Genova J (2022). Archaeosomes: New Generation of Liposomes Based on Archaeal Lipids for Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications. ACS Omega, 8, 1. 10.1021/ACSOMEGA.2C06034/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/AO2C06034_0004.JPEG [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouten S, Hopmans EC, Schefuß E, & Sinninghe Damsté JS (2002). Distributional variations in marine crenarchaeotal membrane lipids: a new tool for reconstructing ancient sea water temperatures? Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 204(1–2), 265–274. 10.1016/S0012-821X(02)00979-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KA, Williams SA, & Santangelo TJ (2021). Thermococcus kodakarensis provides a versatile hyperthermophilic archaeal platform for protein expression. Methods in Enzymology, 659, 243. 10.1016/BS.MIE.2021.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinninghe Damsté JS, Rijpstra WIC, Hopmans EC, den Uijl MJ, Weijers JWH, & Schouten S (2018). The enigmatic structure of the crenarchaeol isomer. Organic Geochemistry, 124. 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2018.06.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinninghe Damsté JS, Schouten S, Hopmans EC, Van Duin ACT, & Geenevasen JAJ (2002). Crenarchaeol. Journal of Lipid Research, 43(10), 1641–1651. 10.1194/JLR.M200148-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadnitskaia A, Baas M, Ivanov MK, Van Weering TCE, & Sinninghe Damsté JS (2003). Novel archaeal macrocyclic diether core membrane lipids in a methane-derived carbonate crust from a mud volcano in the Sorokin Trough, NE Black Sea. Archaea, 1(3), 165. 10.1155/2003/329175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub CT, Counts JA, Nguyen DMN, Wu C-H, Zeldes BM, Crosby JR, Conway JM, Otten JK, Lipscomb GL, Schut GJ, Adams MWW, & Kelly RM (2018). Biotechnology of extremely thermophilic archaea. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 42(5), 543–578. 10.1093/femsre/fuy012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teske A, Amils R, Ramírez GA, & Reysenbach AL (2021). Editorial: Archaea in the Environment: Views on Archaeal Distribution, Activity, and Biogeography. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12, 497. 10.3389/FMICB.2021.667596/BIBTEX [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney JE, & Tingley MP (2015). A TEX86 surface sediment database and extended Bayesian calibration. Scientific Data 2015 2:1, 2(1), 1–10. 10.1038/sdata.2015.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourte M, Schaeffer P, Grossi V, & Oger PM (2020). Functionalized Membrane Domains: An Ancestral Feature of Archaea? Frontiers in Microbiology, 11. 10.3389/FMICB.2020.00526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uda I, Sugai A, Itoh YH, & Itoh T (2004). Variation in Molecular Species of Core Lipids from the Order Thermoplasmales Strains Depends on the Growth Temperature. Journal of Oleo Science, 53(8). 10.5650/jos.53.399 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine DL (2007). Adaptations to energy stress dictate the ecology and evolution of the Archaea. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2007 5:4, 5(4), 316–323. 10.1038/nrmicro1619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Vossenberg JLCM, Driessen AJM, & Konings WN (1998a). The essence of being extremophilic: The role of the unique archaeal membrane lipids. Extremophiles, 2(3), 163–170. 10.1007/S007920050056/METRICS [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Vossenberg JLCM, Driessen AJM, & Konings WN (1998b). The essence of being extremophilic: The role of the unique archaeal membrane lipids. Extremophiles, 2(3), 163–170. 10.1007/S007920050056/METRICS [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JX, Xie W, Zhang YG, Meador TB, & Zhang CL (2017). Evaluating production of cyclopentyl tetraethers by Marine Group II Euryarchaeota in the pearl river estuary and coastal South China Sea: Potential impact on the TEX86 paleothermometer. Frontiers in Microbiology, 8(OCT), 2077. 10.3389/FMICB.2017.02077/BIBTEX [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Chen H, Chen Y, Chen A, Feng X, Zhao B, Zheng F, Fang H, Zhang C, & Zeng Z (2023). Thermophilic archaeon orchestrates temporal expression of GDGT ring synthases in response to temperature and acidity stress. Environmental Microbiology, 25(2), 575–587. 10.1111/1462-2920.16301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Z, Chen H, Yang H, Chen Y, Yang W, Feng X, Pei H, & Welander PV (2022). Identification of a protein responsible for the synthesis of archaeal membrane-spanning GDGT lipids. Nature Communications 2022 13:1, 13(1), 1–9. 10.1038/s41467-022-29264-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Z, Liu XL, Farley KR, Wei JH, Metcalf WW, Summons RE, & Welander PV (2019). GDGT cyclization proteins identify the dominant archaeal sources of tetraether lipids in the ocean. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(45), 22505–22511. 10.1073/PNAS.1909306116/SUPPL_FILE/PNAS.1909306116.SAPP.PDF [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YG, Pagani M, & Wang Z (2016). Ring Index: A new strategy to evaluate the integrity of TEX86 paleothermometry. Paleoceanography, 31(2), 220–232. 10.1002/2015PA002848 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou A, Weber Y, Chiu BK, Elling FJ, Cobban AB, Pearson A, & Leavitt WD (2020). Energy flux controls tetraether lipid cyclization in Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. Environmental Microbiology, 22(1), 343–353. 10.1111/1462-2920.14851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C, Lipp JS, Wörmer L, Becker KW, Schröder J, & Hinrichs KU (2013). Comprehensive glycerol ether lipid fingerprints through a novel reversed phase liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry protocol. Organic Geochemistry, 65, 53–62. 10.1016/J.ORGGEOCHEM.2013.09.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

FOR REVIEWERS ONLY

Whole genome sequencing data has been deposited into NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1022152. The raw sequencing data will be freely accessible upon publication. The following reviewer link is provided for verification: https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1022152?reviewer=sddubj7rutlsfoteg5l77o5h4i