Abstract

Immunotherapy shows efficacy for multiple cancer types and potential for expanded use. However, current immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are ineffective in microsatellite-stable colorectal cancer (CRC), which is more commonly diagnosed. Immunotherapy strategies for non-responsive CRC, including new targets and new combination therapies, are being tested to address this need. Importantly, a subset of inherited germline genetic variants associated with CRC risk are predicted to regulate genes with immune functions, including genes related to existing ICIs, as well as new potential targets in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region and immunoregulatory cytokines. Here, we review discoveries in inherited genetics of CRC related to the immune system and draw connections with ongoing developments and emerging immunotherapy targets.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, pharmacogenomics, colorectal cancer, immune checkpoint inhibitors, GWAS

The need for new immunotherapies for CRC

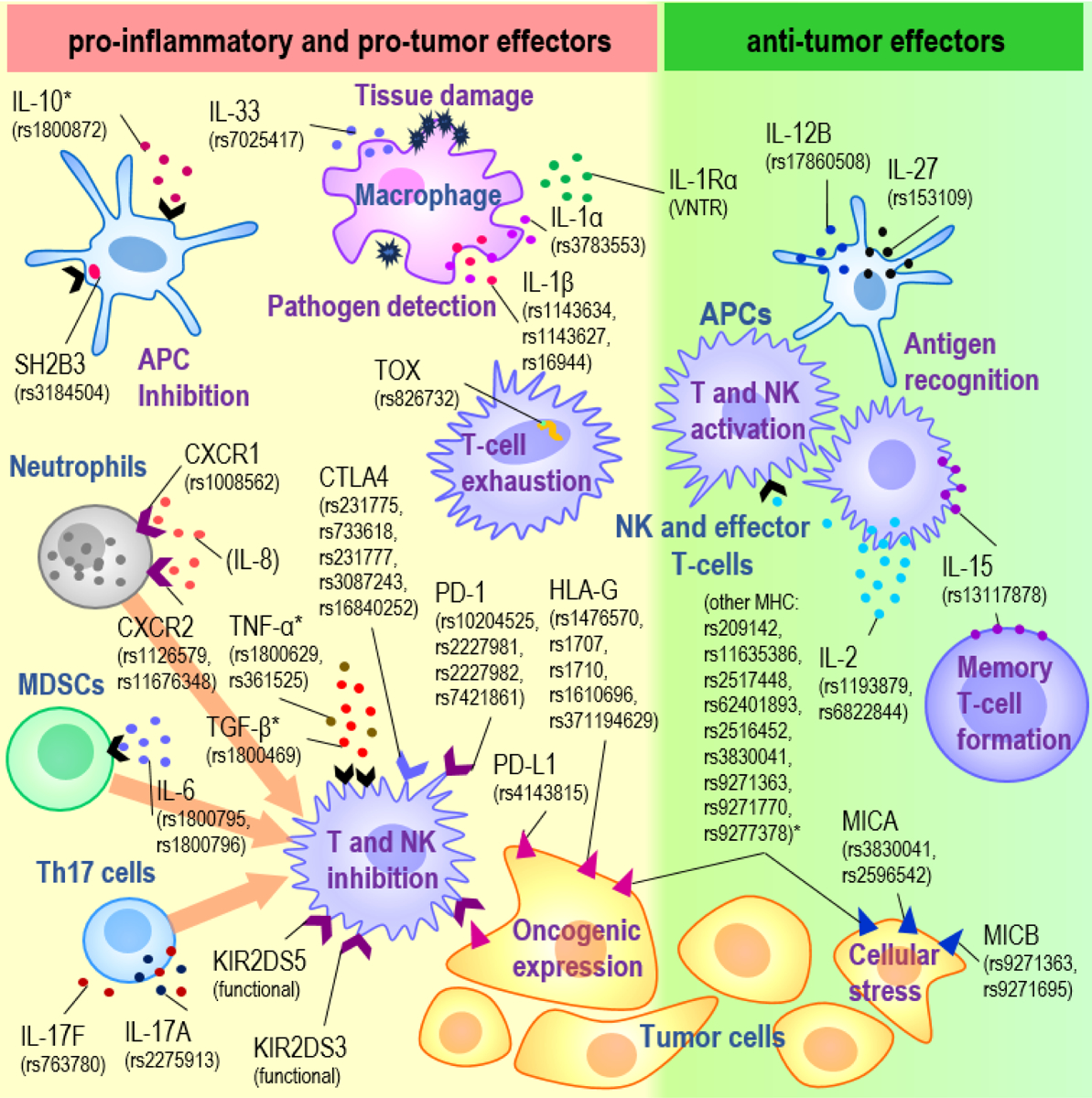

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), monoclonal antibodies that block inhibitory interactions between immune and cancer cells, are the main immunotherapy used to treat colorectal cancer (CRC). To date, ICIs are highly effective in CRC but only in limited circumstances, namely tumors with microsatellite instability (MSI-H) (see glossary). Two specific checkpoint interactions are targeted in current FDA approved ICI therapies. The first targets anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) (Figure 1, Key Figure). PD-L1 is expressed on the extracellular surface of healthy cells and is often upregulated in cancer cells, signaling to protect from cytotoxic activity of immune cells expressing PD-1 receptor [1]. ICI monoclonal antibodies against PD-1 (such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab) and PD-L1 (such as atezolizumab) block this interaction and encourage cytotoxic killing of cancer cells [1]. The second interaction targeted by ICIs is between anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4, CTLA-4, and ligand B7 (Figure 1). The CTLA-4 receptor is expressed on activated or regulatory T cells and competitively binds to B7 ligand of antigen presenting cells, preventing activating CD28 receptors from binding to B7, which results in a subsequent net downregulation of T cell activation [2]. Monoclonal antibodies (such as ipilimumab and tremelimumab) block CTLA-4 receptors, resulting in increased T cell activation and treatment efficacy when combined with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade [3,4].

Figure 1, Key Figure: Variants in immune-related genes associated with CRC.

Variants (indicated by rsIDs) associated with CRC risk or survival from GWAS and/or candidate gene studies and their corresponding immune gene-encoding proteins and main cell types are shown. Cell types include tumor cells (yellow), APCs (blue, branching), macrophages (pink), NK and effector T cells (purple), neutrophils (gray), MDSCs (green), and Th17 cells (blue, round), while interactions involve cytokines (circles), receptors (chevrons) and cell surface proteins (triangles). (i) Variants on the left (yellow background) are genes associated with pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-33, IL-1α, IL-1β, CXCR1, CXCR2, IL-6, IL-17F, IL-17A) downstream effectors of inflammation (TOX, SH2B3), or pro-tumorigenic interactions between tumor and NK and T cells (CTLA4, PD-1, PD-L1, HLA-G, KIR2DS5 and KIR2DS3) (ii) Genes associated with anti-tumor effectors are listed on the right (green background). Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; GWAS, Genome-wide association study; APCs, antigen presenting cells; NK, Natural Killer; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell; Th17, T-helper 17. *genes with mixed or uncertain effects

In a recent United States-based study of ~100,000 CRC patients, 14% of CRC tumors were MSI-H and potential candidates for ICI treatment [5]. MSI-H tumors show high mutation levels, often due to mismatch repair (MMR) defects. These tumors develop a high tumor mutation burden (TMB) and neoantigen load, which leads to higher immune cell infiltration compared to microsatellite stable (MSS) tumors [6]. MSS tumors rarely respond to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade, while most MSI-H tumors show therapeutic benefit [7]. Combination CTLA-4/PD-1 blockade has nearly 100% pathological response in MSI-H tumors and improved response over PD-1 blockade monotherapy [4]. Despite the high initial response rate, ICI therapeutic resistance has been observed in up to 50% of MSI-H CRC patients [8] and is linked to factors such as T-cell exhaustion, inflammation, and oncogene-driven immune inhibition [1]. Thus, there is a need for additional immunotherapy strategies for CRC effective for both MSS and MSI-H resistant tumors.

Findings from germline genetic and genomics studies can provide clues for novel approaches by illuminating new therapeutic directions and biomarkers. CRC is predominately sporadic with a polygenic effect, driven by the net effect of many common genetic variants with low individual effects [9]. Conversely, the inheritance of rare high-risk pathogenic variants associated with a monogenic CRC cancer syndrome only accounts for 2–5% of CRC [8]; the most common of these syndromes are caused by inherited pathogenic variants in genes essential for DNA repair and proofreading [10]. These include Lynch syndrome which is caused by a pathogenic variant in one of four DNA mismatch repair genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2), polymerase proofreadin-gassociated polyposis caused by pathogenic variants in POLE or POLD1, and autosomal recessive MUTYH-associated polyposis which is characterized by impaired DNA base excision repair [10]. Due to accelerated DNA damage, tumors arising in individuals with these syndromes are typically MSI-H or have high TMB and are thus treated effectively with established ICIs [10]. Therefore, when considering immunotherapy strategies for MSS CRC, functional understanding of single nucleotide variants (SNVs) associated with sporadic CRC has potential to provide novel insights. In this review, we connect findings from genomics studies of CRC risk to advances in immunotherapy.

The state of colorectal cancer risk allele identification

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) identify risk variants by comparing the frequency of individual germline SNVs throughout the genome in CRC cases compared to unaffected controls. Currently we are in a “post-GWAS” era as research efforts move from discovery to interpretation of GWAS findings. Still, there is substantial heritability for CRC that is not yet explained [8], particularly for understudied populations. Furthermore, many CRC risk alleles have been only recently identified. A 2023 GWAS of CRC, comprised of 100,204 cases and 154,587 controls of European and East Asian ancestry, identified 170 loci associated with CRC risk, 37 of which were previously unknown [9]. Fernandez-Rozadilla et al projected that to identify 80% of CRC genetic heritability through GWAS would require a sample size of over 500,000 cases, currently a prohibitively high number [9]. The remaining undiscovered heritability in Europeans and East Asians is likely limited to rare variants or variants with very weak effects. New CRC risk alleles are more likely to be identified in underrepresented populations, such as individuals of African ancestry as well as studying variants not included in GWAS, such as structural variants, or using other multi-omics approaches [9].

While GWAS are agnostic and assess variants throughout the genome, candidate gene studies are hypothesis-driven and include a limited number of variants. The candidate gene case-control approach predates GWAS, though it is still used due to its advantage of detecting risk effects in smaller studies by reducing the number of multiple comparisons adjustments needed for statistical power. Because SNVs are selected for study based on a hypothesis, functional interpretation can be more straightforward than GWAS, though both approaches have ongoing interpretation challenges.

There is often a lag from identification of a risk variant to functional interpretation because risk SNVs are typically located in non-coding regions of the genome with predicted transcription regulatory functions [10]. After GWAS, the likely causal SNV(s) for each locus is frequently determined through fine mapping. The effector gene and SNV function can be predicted based on proximity to mapped chromatin features from epigenetic studies, such as expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) [10]. Transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) and methylome-wide association studies (MWAS) are also being employed to validate GWAS findings and effector genes [9]. These approaches are not definitive for function and are often followed by more intensive in vitro studies such as transcription factor binding studies, massively parallel reporter assays (MPRAs), or high-throughput CRISPR screens. For additional functional insight, testing of interactions between inherited genetic variants and other factors, such as co-occurring traits, multiple variants, environmental factors, or treatment efficacy may be conducted.

Utility of risk variants

CRC risk variants have the potential to improve outcomes by illuminating strategies for prevention and treatment, identification of unaffected individuals needing heighted screening, and individualizing CRC treatment based on genetic findings. Genes associated with CRC risk are being evaluated as treatment targets in preclinical mechanistic studies and clinical trials.

Furthermore, polygenic risk scores, pharmacogenomics, and combined prediction models may be used to identify individuals with CRCs that are more likely to respond to ICIs or to predict the most effective ICI. While identification of MSI-H CRC is part of routine clinical practice and informs on treatment recommendations including efficacy for ICIs, the utility of germline pharmacogenomics for ICI response for MSS CRC is less understood. There is some promise in this area as a recent pan-cancer candidate gene study of ICI response and toxicity found SNVs associated with ICI efficacy mapped near predicted effector genes involved in the tumor microenvironment and immunoregulatory cytokines, including CCL2, IL1RN, IL12B, CXCR3, and IL6R, and SNVs associated with ICI toxicity mapped near effector genes directly related to the targets, such as CTLA4 and PD-L1 encoding gene, CD274 [13].

In CRC, understanding heritable risk of immune-related adverse events (AE) is of great interest, though AE are not generally a deterrent for use of ICIs as patients who have these events show a stronger treatment response and net survival benefit [14]. Indeed, ICI-treatment related deaths are rare, occurring in less than 2% of patients, and are often due to organ-specific effects (e.g. myocarditis or colitis) [14]. Instead, heritable risk may indicate the need for stricter monitoring and earlier intervention for AE [14]. With increased use of ICIs, it may be possible to develop models using germline variants associated with severe ICI-toxicity in combination with other biomarkers to identify individuals for whom ICI treatment may not be warranted or for those that will need closer monitoring and immediate intervention for AE.

Genetic variants and immune checkpoint targets PDL-1, PD-1 and CTLA4

The PD-1 receptor is encoded by PDCD1. Before the importance of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway in cancer was appreciated, PDCD1 variants were identified as risk factors for multiple autoimmune diseases, including type 1 diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis [15]. The role of PDCD1 and CD274 SNVs in CRC risk has been explored in candidate gene studies with mixed findings. In single cohort studies and meta-analyses of CRC with ≥450 cases, few associations were identified (Table 1). One PDCD1 3’UTR SNV, rs10204525, was associated with reduced progression-free and overall survival [16], though this variant was not significant for CRC susceptibility in a separate study [17]. Other studies on PDCD1 SNVs have also shown mixed findings [17–19]. A meta-analysis identified pan-cancer risk with both PDCD1 and CD274 SNVs, and four were significant in stratified analyses of gastrointestinal cancers (Table 1), though not all were significant in CRC-specific studies [17,20].

Table 1:

Variants in ICI genes associated with CRC risk.

| Gene | Variant | Risk effects | Model (#cases/controls) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDCD1 (PD-1) | rs10204525, 3′UTR | Reduced overall survival (HR=1.48, P value=0.02) | Survival, dominant (668/NA) | [16] |

| Reduced progression-free survival (HR=1.50, P value=0.034) | ||||

| PDCD1 (PD-1) | rs2227981, synonymous | Pan-cancer risk (OR=0.82, P value=0.04) | Recessive (5622/5450) | [20] |

| GI cancer risk (OR=0.60, P value=0.01) | Dominant (906/1151) | |||

| PDCD1 (PD-1) | rs2227982, missense, p.Ala215Val | GI cancer risk (OR= 1.18, P value=0.01) | Heterozygous (2571/3543) | [20] |

| PDCD1 (PD-1) | rs7421861, intronic | GI cancer risk (OR = 1.19, P value=0.04) | Heterozygous (2526/3565) | [20] |

| CD274 (PD-L1) | rs4143815, 3’UTR | GI cancer risk (OR= 0.59, P value= 0.03) | Homozygous (2321/2573) | [20] |

| CTLA4 | rs231775, missense, p.Thr17Ala | Risk effect specific to CRC and thyroid cancer (OR=1.40, P value=0.022) | Homozygous (1,003/1,303) | [2] |

| CTLA4 | rs733618, promoter | CRC risk, predicted alteration to favor alternate splicing (OR=1.27, P value=0.04) | Over-dominant (1089/1489) | [22,23] |

| CTLA4 | rs231777, intronic | Colon cancer risk, Asian specific (OR=1.30, P value=0.047) | Dominant (627/601) | [18,19] |

| CTLA4 | rs3087243, downstream | CRC risk and survival, European specific (OR= 1.32, P value=0.04, survival HR=1.54, P value=0.03) | Dominant (491/433) | [2,24] |

| CTLA4 | rs16840252, promoter | Colon cancer risk (OR=2.54, P value=0.04) | Recessive (1,005/1,303) | [2] |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio; CRC, colorectal cancer; GI, gastrointestinal; #, number

In contrast, multiple CTLA4 SNVs are associated with CRC susceptibility in candidate gene studies (Table 1). CTLA4 variant rs231775 has drawn considerable interest because it is a common coding missense variant (p.Thr17Ala, c.49A>G), and meta-analyses showed increased CRC risk associated with the A allele [21,22]. The A allele conveyed risk for CRC and thyroid cancer but was protective against most other cancers evaluated, suggesting differential biology by tissue type [21]. Two SNVs map ~2kb upstream of CTLA4 in a region important for CTLA4 transcriptional regulation. Rs733618 increases CRC risk when two risk alleles are inherited; it is predicted to alter an NF-1 transcription factor binding site, leading to alternative splicing [22,23]. The other variant, rs16840252, increases colon cancer risk [2]. Other CTLA4 SNVs show varied findings. It is unclear if these differences are related to study heterogeneity, study design or ancestry. For example, the CTLA4 3’UTR variant rs3087243 was significant for CRC risk in individuals of European ancestry [24] but not in multiple studies of individuals of Asian ancestry [2,18]. Conversely, rs231777, an intronic variant, conveyed CRC risk in Asians [18] but not in Europeans [19]. Additional meta-analyses, functional studies, and fine mapping are needed to clarify how CTLA4 polymorphisms alter an individual’s risk of developing CRC and if they are informative for predictions of immunotherapy response.

These studies support the idea that variants in established CRC immunotherapy target genes can increase CRC risk. Some uncertainty stems from inconsistency between studies and lack of validation in large GWAS for CRC susceptibility. GWAS and additional candidate gene studies have identified CRC risk SNVs involved in other aspects of immune-tumor interactions, and these may be of relevance for future immunotherapy.

CRC risk associations and the highly variable major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is essential for antigen presentation, a cell-cell interaction that can activate T-cells and natural killer (NK) cells in response to oncogenic mutations. Many components of the MHC and related immunoregulatory machinery are encoded by genes on the short arm of chromosome 6, a gene dense region with extreme genetic variability [25]. This variability makes it challenging to study risk effects of single variants in part due to ancestry-specific effects and conditional risk by combinations of variants [11,26]. Despite this complexity, multiple GWAS risk loci for CRC have been identified in the MHC region (Table 2), though their functional impacts are yet to be completely deciphered [11]. In the MHC region, mRNA transcripts are associated with CRC risk in TWAS, as are CpG islands and shores in MWAS, reinforcing the importance of MHC gene regulation in CRC development [11]. More precise associations may be elucidated by focused analyses of haplotypes of multiple adjacent variants, as this approach has been effective for other diseases [27].

Table 2:

Variants in the MHC region associated with CRC risk.

| Variant/location | Type of study, (#cases/controls) | Ancestry-specific effects | Predicted impact | Other published SNVs | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs209142: HCG14 promoter (OR=1.09*, P value= 3.66×10−8) | GWAS (100,204/154,587) | Higher risk in Europeans | Unknown | None | [11] |

| rs1476570: HLA-G intron (OR=1.12, P value=6.71×10−9) | GWAS (22,775/47,731) | Asian-specific risk | eQTL of HLA-G and HLA-V | None | [33] |

| rs1707: HLA-G 3′UTR (0R=0.64, P value=0.021) | Candidate gene, dominant model (308/294) | Studied only in Europeans | HLA-G expression and mRNA stability | rs1710, rs1610696, rs371194629 | [31] |

| rs116353863†: intergenic (OR=1.46*, P value= 3.21×10−9) | GWAS (100,204/154,587) | No differences in Europeans and Asians | Unknown | None | [11] |

| rs2517448: intergenic (OR=1.11*, P value= 1.61×10−11) | GWAS (100,204/154,587) | No differences in Europeans and Asians | eQTL of HCG20, weaker effects in 17 others, including 5 HLA genes | rs3131043 | [11,12] |

| rs62401893: HLA-B intron (OR=1.27*, P value= 3.06×10−8) | GWAS (100,204/154,587) | No differences in Europeans and Asians | Unknown | rs116685461 | [11] |

| rs2596542: MICA promoter, MICA-AS1 intron (HR= 0.75, P value=0.04) | Candidate gene (236/8,609) Protein level (312/10,834) |

No differences in European and African ancestry | Soluble MICA protein | None | [37] |

| rs2516452: intergenic (0R=0.85*, P value= 4.82×10−11) | GWAS (100,204/154,587) | No differences in Europeans and Asians | Unknown | rs2516420 | [11] |

| rs3830041: NOTCH4 intron (OR=1.16, P value=1.65×10−8) | GWAS (22,775/47,731) | Asian-specific risk | eQTL of MICA | None | [33] |

| rs9271363: intergenic (OR=1.21*, P value=8.86×10−20) | GWAS (100,204/154,587) | No differences in Europeans and Asians | Unknown | rs9271695 | [11] |

| rs9271770: intergenic (OR= 1.08, P value=3.6×10−8) | GWAS (34,627/71,379) | Only studied in Europeans | eQTL of HLA-DRB5 and HLA-DRB1, weaker effects in 3 other genes | None | [12] |

| rs9277378: HLA-DPA1 promoter, HLA-DPB1 intron (OR=0.92, P value=0.002) | Cross-cancer pleiotropy study (10,039/30,277) | Only studied in Europeans | eQTL of HLA-DPB2, weaker effects in 5 genes | None | [60] |

Abbreviations: #, number; GWAS, Genome wide association study; eQTL, expression quantitative trait loci; HR, hazard ratio.

Calculated OR from Beta value,

Rare variant, minor allele frequency <0.05

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes of the MHC region

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes are a large family of genes involved in antigen presentation and other immune recognition functions. Somatic loss of MHC class I HLA gene expression in colorectal tumor cells is a known mechanism for immune evasion [28,29]. While there are CRC risk variants with suspected regulatory effects on multiple HLA genes (Table 2), HLA-G variants have been well-characterized. HLA-G is an inhibitory signal important for maternal-fetal immune tolerance that can be expressed by tumors, resulting in heightened immune evasion and worse outcomes [30] (Figure 1). Variants in the 3’ UTR of HLA-G have been studied in candidate gene studies for CRC risk [31] and response to treatment [32], with some risk associations identified (Table 2). Notably, intergenic variant rs1476570 was associated with increased CRC risk in a GWAS of East Asians; it maps to an eQTL for altered expression of HLA-G and other HLA genes [33]. Because of its immunosuppressive function and limited expression in normal adult cells, HLA-G has drawn interest as a tumor-specific target [30]. In in-vitro and in vivo models, CAR-T cells generated to target HLA-G were effective at killing tumor cells, though multiple obstacles to use CAR-T cells to treat solid tumors remain [30].

MHC class I chain-related proteins (MICA and MICB) of the MHC region

The MHC class I chain-related proteins A and B (MICA and MICB) are cellular stress-induced signals that activate cytotoxic activity of nearby NK cells and some T-cells. MICA and MICB are activating when expressed on the surface of tumor cells. Conversely, they induce an inhibitory effect when they undergo proteolytic shedding and become soluble, blocking their corresponding NKG2D receptors [34] (Figure 1). Following this paradigm, high MICB expression in CRC cells indicates favorable prognosis [35], but soluble expression is associated with worse prognosis [36]. Multiple inherited variants are associated with levels of soluble MICB, one of which, rs2596542, is also associated with CRC (Table 2) [37]. Short tandem repeat (STR) variants within MICA are associated with CRC risk and increase invasion and metastatic properties in in vitro functional studies [38]. MICA variant rs3830041 is associated with CRC in Asians and is an eQTL for reduced MICA surface expression in normal colon tissue [33]. Multiple GWAS have identified CRC risk effects of two nearby variants, rs9271363 [11] and rs9271695 [26], which have predicted MICB regulatory functions. Given the complexity of the MICA/B ligand-NKG2D receptor interaction, proposed therapeutic approaches target ligand shedding and soluble MICA/B. One in vitro study generated antibodies that blocked the MICA domain required for shedding without blocking NKG2D surface binding and activation. Another in vitro study determined that regorafenib, a multi-kinase inhibitor that disrupts angiogenesis, effectively reduced soluble MICA [36]. Regorafenib is now in use for refractory CRC treatment in clinical trials, including combination therapy with ICIs [39]. Some trials have shown synergistic effects, though it is yet to be determined whether this is due to regorafenib’s anti-angiogenic properties, enhanced ICI immunogenic effects by reducing soluble MICA, or other tumor immune microenvironment changes [39]. To model tumor-immune interaction, an in vitro study used colon spheroids cocultured with lymphocytes and found a synergistic anti-tumor effect through blockade of MICA/B and NKG2A [40]. While the genetic complexity of the MHC region is challenging to interpret for individual CRC risk effects, MICA/B and HLA-G are promising future immunotherapy targets.

MHC receptors: killer immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR)

Several MHC class I ligand receptors belong to a large family of killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) that are expressed on NK cells and a subset of T cells [25] (Figure 1). KI-Rencoding genes are highly variable with SNVs as well as insertion/deletions and copy number variations that completely shift which KIR genes result in functional proteins [25]. Individuals with complete coding sequences of KIR2DS3 and KIR2DS5 showed increased CRC risk in a candidate gene study [41] and meta-analysis [42], respectively. In phase II clinical trials, CRC patients lacking functional KIR2DS4 exhibited improved overall survival [43] and were more likely to respond when treated with cetuximab, an anti-EGFR antibody that indirectly stimulates NK cells [44].

Secreted cytokines and chemokines

Immune cell activity depends on a network of cytokine-receptor interactions. This network has been extensively studied for immunotherapy applications with over 27 different cytokine-based treatments in clinical trials [45]. Most interactions are not yet fully characterized, but functions relevant to immunotherapy have been identified, such as immune mobilization and tumor cell signaling resulting in a synergistic effect with ICIs.

While activation of NK and T-cells typically improves response to CRC treatment, inflammation is immunosuppressive and has pro-tumorigenic effects, promoting ICI resistance [8]. Inflammatory bowel diseases, such as colitis, increase CRC risk [46] and can be a severe side effect of ICIs [47]. CRC risk variants have been identified in genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL1A, IL1B, IL1RN, IL6, IL17A, IL17F, and IL33, as well as IL-8 receptor genes CXCR1 and CXCR2 (Table 3, Figure 1). Among these findings, variants in IL33 (rs7025417) and IL1B (rs1143634 and rs1143623) are of interest because they also associate with mRNA expression [48,49]. Variants in the receptor of IL-6, IL6R, and the antagonist to IL-1, IL1RN, are also relevant because variants in related genes have been associated with ICI success in a pan-cancer pharmacogenomic study [13]. Pharmacological reduction of inflammation through inhibition of these cytokines may improve ICI efficacy in combined CRC treatment. Functional studies have shown synergistic effects of combined treatment or re-sensitization of ICI resistant tumors (Table 3).

Table 3:

Variants in cytokine genes associated with CRC risk and relevant functional findings.

| Gene | Variant/Location | Study model (#cases/controls) | Function | Key functional and clinical trial findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net pro-inflammatory and pro-tumorigenic effect | |||||

| IL1A | rs3783553: 3’UTR (0R=1.75, P value=0.01) | Heterozygous (721/746) | -Nonspecific immune system and pro-tumorigenicresponses -IL-1α and IL-1β secreted by macrophages in response to endocytosis of potential pathogens -IL-1 receptor antagonist IL-1Rα blocks IL-1 receptor 1, preventing inflammation |

-IL-1 receptor antagonist, Anakinra, is effective for some cancers -Modest efficacy in CRC when combined with chemotherapy |

[45,49,61–64] |

| IL1B | rs1143634: synonymous* (OR=0.74, P value=0.01) | Allelic (527/639) | |||

| rs1143623: promoter* (OR=0.78, P value=0.01) | Allelic (527/639) | ||||

| rs1143627: promoter (OR = 0.83, P value=0.03) | Dominant (3064/5426) | ||||

| rs16944: promoter (0R=0.72, P value<0.001) | Heterozygous (1824/3130) | ||||

| IL1RN | intron VNTR (OR=1.49, P value=0.045) | Dominant (1686/2896) | |||

| IL33 | rs7025417: intron* (OR=0.82, P value=0.005) | Allelic (768/876) | -Widely expressed, similar to IL-1α, pro-tumorigenic in CRC | -Disruption of IL-33 and receptor, stimulation 2 (ST2), causes increased T-cell activity and response to anti-PD-1 therapy in a preclinical model | [48,65] |

| IL17A | rs2275913: promoter (OR=1.75, P value <0.001) | Dominant (2599/2845) | -Secreted primarily by Th17 cells -Modulates microbiome-immune interactions in epithelial tissue -Can upregulate tumor PD-L1, reducing ICI efficacy |

-In in vitro and in vivo models, inhibition combined with anti- PD-1 treatment shows synergistic effect -Clinical trials in patients with MSS CRC in progress. |

[66–68] |

| IL17F | rs763780: missense, (OR=0.43, P value=0.02) | Homozygous, European-specific effect (2599/2845) | -Homology to IL-17A and can form heterodimers, though they have non-redundant functions -Both act in synergy with TNFα |

||

| IL6 | rs1800795: promoter (0R=1.10, P value=0.01) | Allelic (7399/9808) | Regulates myeloid- derived suppressor cells (MDSC), which inhibit NK and T-cell anti-tumor activity, negative CRC prognostic marker | -Inhibition with monoclonal antibody combined with anti- PD-1 therapy shows stronger response than either alone in vivo and in vitro. | [69,70] |

| rs1800796: promoter (0R=1.07, P value<0.001) | Allelic (2581/3363) | ||||

| CXCR1 (receptor to IL-8) | rs1008562: upstream (OR= 1.57, P value = 0.003) | Homozygous, rectal-specific (754/955) | -Chemokine recruits pro-inflammatory macrophages and neutrophils to the site of inflammation -Inhibits CD8+ T-cells -High levels are associated with ICI resistance |

-IL-8 and receptor blockade are in clinical trials of combination therapies in non-CRC cancers -Antibody therapy may re-sensitize tumors de-sensitized to growth inhibitors |

[46,71–73] |

| CXCR2 (receptor to IL-8) | rs1126579: 3′ UTR (OR=1.56, P value=0.001) | Homozygous, rectal-specific (752/959) | |||

| rs11676348: downstream (0R=0.93, P value= 8.3×10−4) | Additive (11,794/14,190) | ||||

| Net anti-tumorigenic effect | |||||

| IL2 | rs11938795: upstream (OR=1.3, P value=0.01) | Allelic (467/467) | -Adaptive immune response -Typically produced by dendritic, NK and T-cells after antigen recognition |

-Often used in combination therapy, though rarely for CRC -Stimulates proliferation and activation of T and B cells -Can induce AE -Expands regulatory T cells (Tregs) and MDSCs that inhibit anti-tumor immune response |

[45,51,74] |

| rs6822844: upstream (OR=1.31, P value=0.02) | Allelic (467/467) | ||||

| IL15 | rs13117878: intron 2 (OR=1.23, P value=0.04) | Homozygous, colon cancer (1553/1956) | -IL-2 family member, supports formation of CD8+ memory T cells, prevention of T-cell immunotolerance -Membrane-bound and lower expression than IL-2, which impacts prospective treatment strategies |

-Combination treatment with anti PD-1 reinvigorated response of refractorytumors, but induced AE -An immunocytokine with combined function to block PD-1 and prolong IL-15 half-life showed efficacy in in vitro models |

[71,75] |

| IL12B | rs17860508: promoter indel* (OR=1.81, P value =0.007) | Homozygous (329/342) | -Produced by antigen presenting cells in response to pathogens -Inhibits immunosuppressive MDSCs and activates NK and T cells |

-Direct dosing was prohibitively high in clinical trials -Localized delivery strategies are in development |

[45,50,76] |

| IL27 | rs153109: promoter (OR=1.41, P value <0.0001) | Dominant (1560/1590) | -IL-12 family member, expressed by APCs, activates multiple innate and adaptive immune cells, including CD8+ T cells | -In in vivo models, overexpression by adenoviral vector increased anti-tumor activities of T cells -In consideration for future adoptive T-cell transfer treatment |

[77,78] |

| High pleiotropy, mixed or uncertain net effect | |||||

| IL10 | rs1800872: promoter (0R=0.65, P value <0.001) | Dominant, Asian-specific risk (3259/4992) | -Immunosuppressive functions, blocks antigen presentation, effect in CRC remains unclear | -Antibody blockade promoted anti-tumor T-cell activity through enhanced antigen presentation in vitro | [79,80] |

| rs1800871: (0R=1.28, P value=0.02) | Allelic (477/544) | ||||

| TGFB1 | rs1800469: promoter (0R= 0.78, P value= 0.02) | 0ver-dominant (8664/12532) | -Tumor stage-dependent effects; anti-tumorigenic in early stages, and pro-tumorigenic in advanced stages -Involved in Treg regulation and inhibition of NK and T-cell activity |

-A small molecule inhibitor, Pirfenidone, reduced tumor growth, inflammation and fibrosis in in vitro and in vivo studies -Combined ICI and anti-TGFβ antibodies, as well as bispecific antibodies effective against both TGF-β and PD-L1, are being evaluated in clinical trials |

[81–83] |

| TNF | rs1800629: promoter (0R=1.42, P value=0.004) | Recessive, elevated risk in Asians (0R=2.23, P value=0.001) (4412/5528) | -Suspected net pro-tumorigenic effect, dependent on the balance of cell types and overall cytokine signaling | -Inhibitors are clinically available and are safe to repurpose in short term use to prevent immune related AE in ICI treatment (ie. colitis) | [84,85] |

| rs361525: promoter, (0R=0.47, P value 0.01) | 0ver-dominant, European-specific risk (901/1179) | ||||

Abbreviations: #, number; OR, odds ratio; CRC, colorectal cancer; Th17, helper-T 17; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitors; MSS, microsatellite-stable; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cells; NK, natural killer; AE, adverse events; Treg, regulatory T cells; APC, antigen presenting cell.

Additionally identified an mRNA expression effect

Cytokines can also support anti-tumor immune activity by downregulating inflammatory pathways or activating NK and T cells. Secretion of anti-tumorigenic cytokines is a common response to antigen presentation. Anti-tumorigenic cytokine genes associated with CRC susceptibility include IL2, IL12B, IL15, and IL27 (Table 3, Figure 1). Variants in IL12B are associated with mRNA expression changes [50] and ICI effectiveness in other cancers [13]. The first cytokine-based cancer treatment developed was purified IL-2 [45]. It is effective in some cancers, often in combined therapies, though it can have AE due to pleiotropic activity and the high dose required for efficacy [51]. Recently, strategies to deliver anti-tumorigenic cytokines in a targeted fashion, such as localized delivery and prolonged half-life through immunocytokines, are in development (Table 3).

Other cytokines have pleiotropic functions that are not entirely characterized or show both pro-and anti-tumorigenic effects that complicate the practicality of targeting them for treatment. This is the case for IL10, TNF and TGFB1, though all are being studied for therapeutic potential in CRC (Table 3, Figure 1). Studies of inherited risk variants of these cytokines that extend beyond overall CRC risk, such as association with survival or tumor stage, may be valuable for understanding potential therapeutic benefit.

Effectors of inflammation

Gene SH2B3 encodes lymphocyte adaptor LNK, a ubiquitously expressed protein involved in hematopoiesis, inflammatory signaling through TNF-α, activation of the JAK-STAT pathway, and migration of immune cells through the endothelial barrier [52] (Figure 1). GWAS identified a missense variant of SH2B3 (rs3184504; p.R262W, c.784T>C) that increases CRC risk [11]. Interestingly, the C allele is also protective against coronary artery disease, hypertension, and multiple aging phenotypes, among others in a phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) [53]. The C allele is predominant in African (allele frequency=0.90) and East Asian (0.99) populations but is less common in those of European ancestry (0.49) [54]. Interest in SH2B3 as a therapeutic target has been limited, likely due to this phenotypic potential trade-off [53].

T-cell exhaustion and TOX

After prolonged antigen stimulation, effector T cells can undergo exhaustion in which T-cells show reduced cytokine production, high inhibition, and low proliferation [55]. Reversing or preventing T-cell exhaustion is a top priority for improving ICI efficacy [55]. Inflammatory cytokines can induce T-cell exhaustion, and the subsequent epigenetic changes are driven by transcription factors, predominately thymocyte selection-associated HMG bOX (TOX) [55] (Figure 1). GWAS identified a CRC risk variant in the intron of TOX, rs826732, and the associated TWAS found TOX expression changes associated with CRC risk [11]. TOX functions as a transcription factor and an essential regulator of exhaustion in in vitro and in vivo studies [55]. TOX inhibition could result in the ability to reverse T-cell exhaustion and improve ICI efficacy.

Immunoediting and tumor evolution

Tumors undergo phenotypic shifts as somatic mutations accumulate and the tumor adapts for accelerated growth. Cancer immunoediting influences somatic mutations because of variable immune response to mutated cells presenting neoantigens; after a mutation event, a cell may be recognized as foreign and eliminated by the innate or adaptive immune system, or it can evade detection and continue to divide [56]. Immune evasion is promoted by mutations in MHC class 1 genes that impair antigen presentation or mutations that induce tumor expression of immune-inhibitory ligands CTLA4 or PD1. Germline variants may impact immunoediting by increasing expression of key immune suppression-related proteins or suppression of genes important for recognition of neoantigens. For example, HLA genotypes have been proposed as biomarkers for response to ICIs [57] and cancer risk in individuals with Lynch syndrome by modifying the immune system’s ability to present or detect neoantigens [58].

Concluding remarks

Great strides have been made in our understanding of inherited risk for CRC, but an interpretive gap in applying findings to development of treatment strategies remains (see Outstanding Questions). Some variants associated with risk through candidate gene studies have been evaluated in parallel for clinical utility in treatment or as biomarkers. However, there is additional potential for novel discovery of markers for ICI therapeutic response or new immunotherapy targets by studying immune-related loci identified through unbiased GWAS approaches, such as MICB, SH2B3, TOX, and the HLA genes. With at least 170 CRC risk loci identified through GWAS [11], it may be of greatest benefit to focus on genes that are part of immune pathways relevant for treatment or prognosis, although many common tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes also exert indirect or direct effects on the immune system. Some CRC risk effects observed are ancestry-specific, which may render these variants limited for directing treatment to certain populations. This underlines the importance of considering ancestry as well as other variables such as sex, age, tumor characteristics, and social determinants of health in interpretation of genetic results and their clinical implications. Pharmacogenomics of CRC patients who respond to ICIs, particularly patients with MSS tumors, is also understudied. As more variations of ICIs are tested in clinical trials of CRC, this is increasingly feasible to study.

Outstanding questions.

Are there genomic loci associated with ICI success in MSS CRC, and how can we further use pharmacogenomic data to determine individualized ICI treatment in CRC?

For many loci associated with CRC risk, the causal SNVs and functional effects have not yet been characterized. How will continued interpretation of GWAS findings and new GWAS loci (eg. TOX) be informative for future treatment?

Some CRC risk loci effects are ancestry-specific. What are the genetic and functional mechanisms responsible for observed population-specific effects?

Which specific loci and genetic variants within the highly variable and gene-dense MHC region are driving inherited CRC risk effects observed in GWAS?

Due to pleotropic effects of cytokines, there are challenges to use them therapeutically. Can inherited variants associated with CRC risk be informative for identifying clinical targets or personalized medicine?

Can MWAS and TWAS elucidate immune loci associated with CRC risk that may yield new treatment strategies?

Due in part to the complexity of immune checkpoint regulation, combination therapies are showing better efficacy than ICIs alone. Multiple combination therapies are in clinical trials and others show promising synergistic effects in in vivo and in vitro models. Ongoing challenges to ICI efficacy include improving immune recruitment to tumors, reversing resistance, managing autoimmune effects, and preventing T-cell exhaustion. As highlighted (Tables 1 and 2), many CRC risk genes are relevant to these functions, and variants from these loci may be predictive biomarkers for these phenotypes. Inherited CRC risk variants may reveal immunotherapy targets that will be effective for MSS CRC. For example, targets other than PD-1 and CTLA-4, such as MICA/B, may be effective, particularly for resistant or non-responsive tumors. Future pharmacogenomic studies may inform personalized immunotherapy for CRC by determining ideal treatment based on genotypes at key loci or via polygenic risk scores.

In summary, the knowledge we have gained on common genetic variants associated with CRC risk may be able to be leveraged for better prediction of therapeutic response as well as in the development of new immunotherapies and combination therapies for treating CRC.

Highlights.

Inherited germline genetic variants associated with risk and outcomes in colorectal cancer (CRC) have been identified in genes that encode the critical components of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) immunotherapy.

Germline variants in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region and its associated killer immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) are associated with both CRC risk and immune function and are being evaluated as immunotherapy targets.

Germline variants in genes encoding immunoregulatory cytokines, receptors, and effectors are associated with CRC risk and inflammation. Cytokine-based therapeutic strategies are being evaluated, often in combination therapy with existing ICIs.

Acknowledgements

Work was supported by the National Cancer Institute, grant R01 CA215151 (AET) and a Pelotonia Graduate Fellowship (NPT).

Glossary

- Candidate gene study

A hypothesis-driven case-control approach to study the association of a limited number of inherited genetic variants with a trait

- CAR-T

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, an approach to induce anti-cancer cytotoxic activity of T-cells, typically to treat hematological cancers. Patient T-cells are extracted and undergo in vitro genetic alterations to express a chimeric receptor for a cancer antigen. Cells expressing the receptor are then infused back into the patient to kill tumor cells

- CpG islands and shores

Regions of the genome with a high density of C preceding G (CpG) dinucleotides, often sites of methylation involved in transcriptional regulation. Islands have dense CpGs and are flanked by less CpG-dense shores

- Expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL)

Variants in the genome associated with altered RNA expression of nearby genes based on comparison of genotype and RNA sequencing data. Data and effects are often tissue-specific

- Fine mapping

A statistical method of identifying which genetic variant(s) are likely causative for an inherited GWAS trait among other variants that are in linkage disequilibrium

- Genome-wide association studies (GWAS)

A method to identify which inherited genetic variants across the genome are associated with a heritable trait in cases and controls

- Massively parallel reporter assay (MPRA)

A high-throughput in vitro method to study DNA regulatory elements. Unique DNA barcodes are paired to predicted regulatory element sequences, cloned into a vector with a reporter gene, and transfected into a cell type of interest. Regulatory activity is determined by comparative DNA and RNA sequencing

- Methylome-wide association studies (MWAS)

Method to identify which methylation sites in the genome are associated with a heritable trait. Data and effects are often tissue-specific

- Microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H)

State of hypermutation characterized by changes in length of repetitive DNA sequences called microsatellites. MSI is often caused by deficient DNA mismatch repair

- Mismatch repair (MMR)

Capacity to edit incorrectly paired DNA bases caused by replication errors or damage before the DNA changes are replicated and become permanent

- Neoantigen load

Categorization of the amount of tumor-specific polypeptides in antigen presentation by MHC class I molecules. Neoantigens are new polypeptides generated by somatic mutations that change amino acids

- Pharmacogenomics

Study of individual variability of drug response and toxicity due to genetic variation. In cancer, this includes germline or tumor genome variability

- Phenome-wide association study (PheWAS)

Method to identify which patient phenotypes are most strongly associated with an inherited genetic variant. It requires a limited number of candidate variants and extensive phenotyping data from many individuals. It can be used to validate GWAS findings or identify new associations

- Transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS)

Method to identify associations between genomic variants, RNA transcription, and an inherited trait. Inherited variants across the genome are compared to eQTL data and used to predict individual gene expression in a large sample, and then predicted expression is associated with the trait of interest. Data and effects are often tissue-specific

- Tumor mutation burden (TMB)

An index to categorize the frequency of mutations in a tumor, often as a biomarker to predict clinical response

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Lei Q et al. (2020) Resistance Mechanisms of Anti-PD1/PDL1 Therapy in Solid Tumors. Front. cell Dev. Biol 8, 672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zou C et al. (2018) CTLA4 tagging polymorphisms and risk of colorectal cancer: a case-control study involving 2,306 subjects. Onco. Targets. Ther 11, 4609–4619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalabi M et al. (2020) Neoadjuvant immunotherapy leads to pathological responses in MMR-proficient and MMR-deficient early-stage colon cancers. Nat. Med 26, 566–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Overman MJ et al. (2018) Durable Clinical Benefit With Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in DNA Mismatch Repair-Deficient/Microsatellite Instability-High Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol 36, 773–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gutierrez C et al. (2023) The Prevalence and Prognosis of Microsatellite Instability-High/Mismatch Repair-Deficient Colorectal Adenocarcinomas in the United States. JCO Precis. Oncol 7, e2200179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keshinro A et al. (2021) Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes, Tumor Mutational Burden, and Genetic Alterations in Microsatellite Unstable, Microsatellite Stable, or Mutant POLE/POLD1 Colon Cancer. JCO Precis. Oncol 5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le DT et al. (2015) PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med 372, 2509–2520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sui Q et al. (2022) Inflammation promotes resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors in high microsatellite instability colorectal cancer. Nat. Commun 13, 7316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiao S et al. (2014) Estimating the heritability of colorectal cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet 23, 3898–3905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valle L et al. (2019) Genetic predisposition to colorectal cancer: syndromes, genes, classification of genetic variants and implications for precision medicine. J. Pathol 247, 574–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez-Rozadilla C et al. (2023) Deciphering colorectal cancer genetics through multi-omic analysis of 100,204 cases and 154,587 controls of European and east Asian ancestries. Nat. Genet 55, 89–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Law PJ et al. (2019) Association analyses identify 31 new risk loci for colorectal cancer susceptibility. Nat. Commun 10, 2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Refae S et al. (2020) Germinal Immunogenetics predict treatment outcome for PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors. Invest. New Drugs 38, 160–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chin IS et al. (2022) Germline genetic variation and predicting immune checkpoint inhibitor induced toxicity. NPJ Genom. Med 7, 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee YH et al. (2015) Meta-analysis of genetic polymorphisms in programmed cell death 1. Associations with rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and type 1 diabetes susceptibility. Z. Rheumatol 74, 230–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon S et al. (2016) Prognostic relevance of genetic variants involved in immune checkpoints in patients with colorectal cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol 142, 1775–1780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin J et al. (2022) Lack of Association Between PDCD-1 Polymorphisms and Colorectal Cancer Risk: A Case-Control Study. Immunol. Invest 51, 1867–1882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ge J et al. (2015) Association between co-inhibitory molecule gene tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms and the risk of colorectal cancer in Chinese. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol 141, 1533–1544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volz NB et al. (2020) Polymorphisms within Immune Regulatory Pathways Predict Cetuximab Efficacy and Survival in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients. Cancers (Basel) 12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashemi M et al. (2019) Association between PD-1 and PD-L1 Polymorphisms and the Risk of Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Case-Control Studies. Cancers (Basel) 11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wan H et al. (2022) Comprehensive Analysis of 29,464 Cancer Cases and 35,858 Controls to Investigate the Effect of the Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4 Gene rs231775 A/G Polymorphism on Cancer Risk. Front. Oncol 12, 878507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J et al. (2020) CTLA-4 polymorphisms and predisposition to digestive system malignancies: a meta-analysis of 31 published studies. World J. Surg. Oncol 18, 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner M et al. (2020) Immune Checkpoint Molecules-Inherited Variations as Markers for Cancer Risk. Front. Immunol 11, 606721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.VAN Nguyen S et al. (2021) Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte Antigen-4 (CTLA-4) Gene Polymorphism (rs3087243) Is Related to Risk and Survival in Patients With Colorectal Cancer. In Vivo 35, 969–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Djaoud Z and Parham P (2020) HLAs, TCRs, and KIRs, a Triumvirate of Human Cell-Mediated Immunity. Annu. Rev. Biochem 89, 717–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huyghe JR et al. (2019) Discovery of common and rare genetic risk variants for colorectal cancer. Nat. Genet 51, 76–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D’Antonio M et al. (2019) Systematic genetic analysis of the MHC region reveals mechanistic underpinnings of HLA type associations with disease. Elife 8, e48476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grasso CS et al. (2018) Genetic Mechanisms of Immune Evasion in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Discov 8, 730–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawazu M et al. (2022) HLA Class I Analysis Provides Insight Into the Genetic and Epigenetic Background of Immune Evasion in Colorectal Cancer With High Microsatellite Instability. Gastroenterology 162, 799–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anna F et al. (2021) First immunotherapeutic CAR-T cells against the immune checkpoint protein HLA-G. J. Immunother. cancer 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garziera M et al. (2016) Association of the HLA-G 3’UTR polymorphisms with colorectal cancer in Italy: a first insight. Int. J. Immunogenet 43, 32–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scarabel L et al. (2022) Association of HLA-G 3’UTR Polymorphisms with Response to First-Line FOLFIRI Treatment in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Pharmaceutics 14, 2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu Y et al. (2019) Large-Scale Genome-Wide Association Study of East Asians Identifies Loci Associated With Risk for Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 156, 1455–1466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferrari de Andrade L et al. (2018) Antibody-mediated inhibition of MICA and MICB shedding promotes NK cell-driven tumor immunity. Science 359, 1537–1542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feng Q et al. (2020) High MICB expression as a biomarker for good prognosis of colorectal cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol 146, 1405–1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arai J et al. (2022) Baseline soluble MICA levels act as a predictive biomarker for the efficacy of regorafenib treatment in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 22, 428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang S et al. (2023) Associations between MICA and MICB Genetic Variants, Protein Levels, and Colorectal Cancer: Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC). Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev 32, 784–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding W et al. (2020) MICA *012:01 Allele Facilitates the Metastasis of KRAS-Mutant Colorectal Cancer. Front. Genet 11, 511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akin Telli T et al. (2022) Regorafenib in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors for mismatch repair proficient (pMMR)/microsatellite stable (MSS) colorectal cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev 110, 102460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Courau T et al. (2019) Cocultures of human colorectal tumor spheroids with immune cells reveal the therapeutic potential of MICA/B and NKG2A targeting for cancer treatment. J. Immunother. Cancer 7, 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diaz-Peña R et al. (2020) Analysis of Killer Immunoglobulin-Like Receptor Genes in Colorectal Cancer. Cells 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghanadi K et al. (2016) Colorectal cancer and the KIR genes in the human genome: A meta-analysis. Genomics Data 10, 118–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borrero-Palacios A et al. (2019) Combination of KIR2DS4 and FcγRIIa polymorphisms predicts the response to cetuximab in KRAS mutant metastatic colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep 9, 2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manzanares-Martin B et al. (2021) Improving selection of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer to benefit from cetuximab based on KIR genotypes. J. Immunother. cancer 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qiu Y et al. (2021) Clinical Application of Cytokines in Cancer Immunotherapy. Drug Des. Devel. Ther 15, 2269–2287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khalili H et al. (2015) Identification of a common variant with potential pleiotropic effect on risk of inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis 36, 999–1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perez-Ruiz E et al. (2019) Prophylactic TNF blockade uncouples efficacy and toxicity in dual CTLA-4 and PD-1 immunotherapy. Nature 569, 428–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Z-H et al. (2019) A functional polymorphism in the promoter region of IL-33 is associated with the reduced risk of colorectal cancer. Biomark. Med 13, 567–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qian H et al. (2018) Two variants of Interleukin-1B gene are associated with the decreased risk, clinical features, and better overall survival of colorectal cancer: a two-center case-control study. Aging (Albany. NY) 10, 4084–4092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Y et al. (2020) A Functional Polymorphism in the Promoter Region of Interleukin-12B Increases the Risk of Colorectal Cancer. Biomed Res. Int 2020, 2091781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muhammad S et al. (2023) Reigniting hope in cancer treatment: the promise and pitfalls of IL-2 and IL-2R targeting strategies. Mol. Cancer 22, 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Devallière J and Charreau B (2011) The adaptor Lnk (SH2B3): an emerging regulator in vascular cells and a link between immune and inflammatory signaling. Biochem. Pharmacol 82, 1391–1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuo C-L et al. (2020) The Longevity-Associated SH2B3 (LNK) Genetic Variant: Selected Aging Phenotypes in 379,758 Subjects. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci 75, 1656–1662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen S et al. (2022) A genome-wide mutational constraint map quantified from variation in 76,156 human genomes. bioRxiv DOI: 10.1101/2022.03.20.485034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maurice NJ et al. (2021) Inflammatory signals are sufficient to elicit TOX expression in mouse and human CD8+ T cells. JCI insight 6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Borroni EM and Grizzi F (2021) Cancer Immunoediting and beyond in 2021. Int. J. Mol. Sci 22, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ivanova M and Shivarov V (2021) HLA genotyping meets response to immune checkpoint inhibitors prediction: A story just started. Int. J. Immunogenet 48, 193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ahadova A et al. (2023) Is HLA type a possible cancer risk modifier in Lynch syndrome? Int. J. Cancer 152, 2024–2031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qin W et al. (2022) A Genetic Variant in CD274 Is Associated With Prognosis in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients Treated With Bevacizumab-Based Chemotherapy. Front. Oncol 12, 922342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun J et al. (2023) Cross-cancer pleiotropic analysis identifies three novel genetic risk loci for colorectal cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet 32, 2093–2102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu L et al. (2021) The association between IL-1 family gene polymorphisms and colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis. Gene 769, 145187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dinarello CA (2018) Overview of the IL-1 family in innate inflammation and acquired immunity. Immunol. Rev 281, 8–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kurzrock R et al. (2019) Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist levels predict favorable outcome after bermekimab, a first-in-class true human interleukin-1α antibody, in a phase III randomized study of advanced colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology 8, 1551651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Isambert N et al. (2018) Fluorouracil and bevacizumab plus anakinra for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer refractory to standard therapies (IRAFU): a single-arm phase 2 study. Oncoimmunology 7, e1474319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van der Jeught K et al. (2020) ST2 as checkpoint target for colorectal cancer immunotherapy. JCI Insight 5, e136073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li S et al. (2022) Targeting interleukin-17 enhances tumor response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in colorectal cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Rev. Cancer 1877, 188758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brevi A et al. (2020) Much More Than IL-17A: Cytokines of the IL-17 Family Between Microbiota and Cancer. Front. Immunol 11, 565470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li G et al. (2022) The associations between interleukin-17 single-nucleotide polymorphism and colorectal cancer susceptibility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol 20, 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li J et al. (2018) Targeting Interleukin-6 (IL-6) Sensitizes Anti-PD-L1 Treatment in a Colorectal Cancer Preclinical Model. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res 24, 5501–5508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peng X et al. (2018) Genetic polymorphisms of IL-6 promoter in cancer susceptibility and prognosis: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget 9, 12351–12364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bondurant KL et al. (2013) Interleukin genes and associations with colon and rectal cancer risk and overall survival. Int. J. cancer 132, 905–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shao Y et al. (2023) CXCL8 induces M2 macrophage polarization and inhibits CD8(+) T cell infiltration to generate an immunosuppressive microenvironment in colorectal cancer. FASEB J 37, e23173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fousek K et al. (2021) Interleukin-8: A chemokine at the intersection of cancer plasticity, angiogenesis, and immune suppression. Pharmacol. Ther 219, 107692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dimberg J et al. (2019) Genetic Variants of the IL2 Gene Related to Risk and Survival in Patients With Colorectal Cancer. Anticancer Res 39, 4933–4940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shi W et al. (2023) A novel anti-PD-L1/IL-15 immunocytokine overcomes resistance to PD-L1 blockade and elicits potent antitumor immunity. Mol. Ther 31, 66–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nguyen KG et al. (2020) Localized Interleukin-12 for Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol 11, 575597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moazeni-Roodi A et al. (2020) Association between IL-27 Gene Polymorphisms and Cancer Susceptibility in Asian Population: A Meta-Analysis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev 21, 2507–2515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ding M et al. (2022) IL-27 improves adoptive CD8(+) T cells’ antitumor activity via enhancing cell survival and memory T cell differentiation. Cancer Sci 113, 2258–2271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zare M et al. (2022) Association of Interleukin-10 Polymorphisms with Susceptibility to Colorectal Cancer and Gastric Cancer: an Updated Meta-analysis Based on 106 Studies. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 53, 1066–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sullivan KM et al. (2023) Blockade of interleukin 10 potentiates antitumour immune function in human colorectal cancer liver metastases. Gut 72, 325–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang JM et al. (2012) Correlation between TGF-β1–509 C>T polymorphism and risk of digestive tract cancer in a meta-analysis for 21,196 participants. Gene 505, 66–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li T et al. (2023) Bispecific antibody targeting TGF-β and PD-L1 for synergistic cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol 14, 1196970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jamialahmadi H et al. (2023) Targeting transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) using Pirfenidone, a potential repurposing therapeutic strategy in colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep 13, 14357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 84.Huang X et al. (2019) Associations of tumor necrosis factor-α polymorphisms with the risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Biosci. Rep 39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen AY et al. (2021) TNF in the era of immune checkpoint inhibitors: friend or foe? Nat. Rev. Rheumatol 17, 213–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]