Abstract

Survival in aerobic conditions is critical to the pathogenicity of many bacteria. To investigate the means of aerotolerance and resistance to oxidative stress in the catalase-negative organism Streptococcus pyogenes, we used a genomics-based approach to identify and inactivate homologues of two peroxidase genes, encoding alkyl hydroperoxidase (ahpC) and glutathione peroxidase (gpoA). Single and double mutants survived as well as the wild type under aerobic conditions. However, they were more susceptible than the wild type to growth suppression by paraquat and cumene hydroperoxide. In addition, we show that S. pyogenes demonstrates an inducible peroxide resistance response when treated with sublethal doses of peroxide. This resistance response was intact in ahpC and gpoA mutants but not in mutants lacking PerR, a repressor of several genes including ahpC and catalase (katA) in Bacillus subtilis. Because our data indicate that these peroxidase genes are not essential for aerotolerance or induced resistance to peroxide stress in S. pyogenes, genes for a novel mechanism of managing peroxide stress may be regulated by PerR in streptococci.

Adaptation to an aerobic environment provides organisms with a wider selection of ecological niches for survival. The major cost associated with this evolutionary gain is constant exposure to the deleterious effects of oxygen, particularly the partially reduced forms of oxygen that include peroxide, superoxide, and hydroxyl radicals (23). In response to this toxic exposure, aerobic organisms have evolved powerful strategies to defend themselves against the damaging effects of oxygen.

The group of organisms collectively known as the lactic acid bacteria provides a useful example of adaptation to the aerobic environment. Unlike organisms that have evolved a system of oxidative phosphorylation, these bacteria have an exclusively fermentative metabolism, and they lack many of the well-characterized enzymes thought to be essential for aerobic survival (13). Nevertheless, most lactic acid bacteria are aerotolerant to some degree and thus are considered facultative anaerobes. Surprisingly, growth is unaffected or even enhanced by exposure to oxygen for some species (38).

Recent investigations have suggested that interaction with oxygen plays an important role in the pathogenesis of infections caused by the lactic acid bacterium Streptococcus pyogenes. This bacterium is an important human pathogen that is responsible for various diseases, including soft tissue infections that range from minor and self-limiting (pharyngitis, impetigo) to severely destructive and life-threatening (necrotizing fasciitis). Toxigenic infections (toxic shock syndrome) and several autoimmune diseases (rheumatic fever, acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis) are also associated with infection by S. pyogenes. Adhesion to host tissues is likely to be an early event in pathogenesis for all of these diseases. Expression of a major adhesin, the fibronectin-binding protein known as protein F or Sfb, is environmentally regulated, being preferentially expressed in aerobic environments (51). Regulation occurs at the level of transcription and is apparently linked to a pathway that senses oxidative stress (22). These observations suggest that S. pyogenes encounters and reacts to an aerobic environment during infection.

Consistent with an at least partially aerobic lifestyle, most isolates of S. pyogenes are highly aerotolerant, and growth yields can actually be increased under aerobic conditions when grown on certain substrates (21). To thrive in an aerobic environment, it is likely that S. pyogenes must possess mechanisms for defense against reactive oxygen species. A critical issue concerns defense against hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a highly reactive molecule that can readily diffuse across cellular membranes and oxidatively damage a number of vital cellular components, including membrane lipids, enzymes, and DNA (39, 44). Not only may S. pyogenes encounter peroxide during the infection of tissue but, like many other lactic acid bacteria, S. pyogenes also has the capacity to produce large amounts of peroxide endogenously when it is growing under aerobic conditions (21). A large body of evidence collected from analysis of multiple bacterial species has implicated catalase, a heme-containing peroxidase, as the major factor responsible for defense against peroxide (19). The importance of catalase is further emphasized by the fact that most facultative and aerobic bacteria contain multiple catalases (14). However, as is characteristic of lactic acid bacteria, S. pyogenes does not synthesize heme and lacks catalase (13). The specific mechanisms by which S. pyogenes adapts to peroxide stress are unknown.

In this study, we have examined the adaptive response of S. pyogenes to peroxide stress and the potential contribution of alternative peroxidases to this response. Using a genomics-based approach, we found that S. pyogenes contains homologues of two peroxidases that have been characterized in other species. Construction and analysis of several mutants revealed that these peroxidases contribute to defense against high-level oxidative stress. In contrast, the inactivation of these genes neither impairs growth under aerobic conditions nor hinders the ability of S. pyogenes to mount an adaptive response against peroxide. Interestingly, this adaptive response was constitutively induced in mutants lacking PerR, a negative regulator of several genes, including ahpC and catalase (katA) in Bacillus subtilis. However, because these latter two genes do not appear to be essential to the S. pyogenes adaptive response, PerR may control expression of genes responsible for a potentially novel strategy for adaptation to aerobic growth environments in S. pyogenes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

The host for molecular cloning experiments was Escherichia coli DH5α. For peroxide resistance experiments involving E. coli, strain CH734 was used. For probing of ςB genes by PCR, the following bacterial strains were used: Staphylococcus aureus Newman (16), Listeria monocytogenes 104035 (45), and B. subtilis Marburg 168 (34). Luria-Bertani broth (48) or tryptone agar (137 mM NaCl, 1% tryptone [wt/vol], 0.1% yeast extract [wt/vol], and 1.4% agar) were used to culture E. coli. Strains of S. pyogenes were grown in Todd-Hewitt medium (BBL) supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract (THY medium) at 37°C. To prepare solid medium for S. pyogenes, Bacto Agar (Difco) was added to THY medium to a final concentration of 1.4%. Various atmospheres for cultures of S. pyogenes were created using conditions established in prior investigations (22). Briefly, for aerobic cultures, streptococci were grown on solid medium in ambient air (20% O2, 0.03% CO2) or in liquid medium in a 125-ml Erlenmeyer flask filled to 8% of its total volume on an orbital shaker rotating at 225 rpm. For near-anaerobic cultures, streptococci were grown statically in 10 ml of liquid medium in a sealed 15-ml culture tube. For anaerobic cultures, streptococci were incubated on solid media in a sealed jar with a commercial gas generator (GasPak catalogue no. 70304; BBL), or in a 10-ml volume of liquid media in a sealed 15-ml culture tube with a commercial additive to produce anaerobic conditions (Oxyrase). When appropriate, the following concentrations of antibiotics were used: 50 μg of kanamycin, 750 μg of erythromycin, 3 μg of chloramphenicol, and 100 μg of ampicillin per ml for E. coli cultures and 500 μg of kanamycin, 3 μg of chloramphenicol, and 1 μg of erythromycin per ml for S. pyogenes cultures.

Computational analyses.

Genome sequence databases for S. pyogenes at the University of Oklahoma (http://www.genome.ou.edu/strep.html) and the Sanger Center (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_pyogenes) were searched for homologues to a set of known bacterial peroxidases. The sequences used as queries in TBlastN (1) searches included: thiol peroxidase (GenBank accession no. AAC74406), Mn2+-pseudocatalase (no. BAA13239), the catalase of the heme-scavenging lactic acid bacteria Lactobacillus sake (no. AAC19139), NADH peroxidase (no. 1942624), alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (no. BAA25695), and glutathione peroxidase (no. AJ000109). The S. aureus ςB gene (no. CAA68932) was used to computationally search for a ςB homologue. The PerR gene (no. Z99108, originally named ygaG; see reference 4) was used to identify its homologue in S. pyogenes.

DNA techniques.

Plasmid DNA was isolated by standard techniques and transformed in E. coli as described by Kushner (37). Transformation of S. pyogenes was performed by electroporation as previously described (6). Restriction endonucleases, ligases, and polymerases were used according to the manufacturers' recommendations. Chromosomal DNA was purified from S. pyogenes as previously described (6). Hybridization analysis was done according to the method of Southern (50), and probes of appropriate sequences were labeled with 32P by a random priming method (Rediprime; Amersham). For amplification of ςB from purified chromosome of various bacteria, primers based on highly conserved regions of ςB were used: sigb5 (CTCCG TGATA AAACA TGGAG CGTTC ATG) and sigb3 (CGAGA GACAT GCATT TGTGA TATAC CGAG).

Deletion of ahpC.

An in-frame deletion in the gene encoding the peroxidase subunit (ahpC) of alkyl hydroperoxide reductase was constructed as follows. Primers ahp5′ (AAAAG GGGTA CCACT ATATG TCTC) and ahp3′ (GCCAT AGCTT GGATC CTAAA ATTTA) were used to amplify a 604-bp fragment containing the entire ahpC open reading frame (see Results) from S. pyogenes strain JRS4. The PCR product was digested with the restriction enzymes KpnI and BamHI (sites in primers as underlined above) and inserted between the corresponding restriction sites of pUC18 (Boehringer Mannheim) to create pJH2. Digestion of pJH2 with BstEII, followed by treatment with ligase, deleted a region internal to ahpC between nucleotides 155 and 292 while conserving the correct reading frame (see Fig. 1). The resulting allele (ahpCΔ155–292) was inserted between the SmaI and PstI sites of the E. coli-streptococcal shuttle vector pJRS233 (42) to create pJH4. This plasmid was used to replace the wild-type ahpC allele in several S. pyogenes strains using a previously described method (47). The chromosomal structure of mutant alleles was confirmed by PCR and hybridization analysis (50).

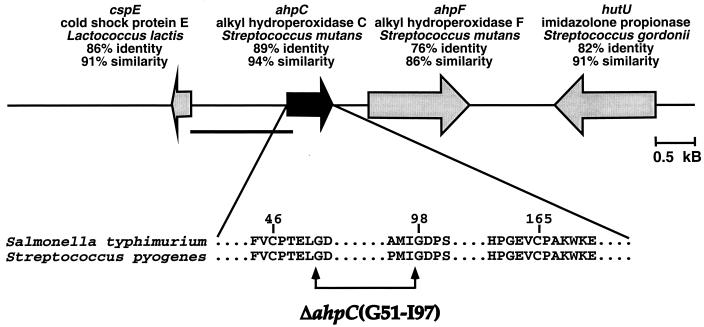

FIG. 1.

Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase gene in S. pyogenes. The position and direction of the ahpC gene is depicted relative to its neighbors in the genome. The percent amino acid identity and similarity to the closest match found by a TBlastN search are shown. The region inserted into the reporter plasmid for expression studies is underlined. Below is a partial alignment of the S. pyogenes ahpC gene with the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium homologue. Regions around the conserved cysteines (C46 and C165) are shown. The 45-amino-acid region removed by deletion is indicated by the arrows.

Deletion of gpoA.

An in-frame deletion in the gene encoding GpoA was constructed using an approach similar to one that has been previously described (47). A 579-bp region corresponding to the entire gpoA coding region was amplified from HSC5 chromosomal DNA by PCR using primers: glu5′ (CCGTT GACCA AATTA TCAGT TACAC CGAGG ATCCG TCACA TGCC) and glu3′ (GAAGT TTTTA ATTAG TAACT ATAAT ATAAA ATAGA ATTCG CACGC C). This PCR product was inserted into a commercial vector (pCR2.1; Invitrogen) by a TA-tail technique to make pJH5 (31). Inside-out PCR was performed on pJH5 using primers gluIFD5′ (GTCAA CTAGT GAGAT GTGTC GACCG TCCTG AGCCT TAACC G) and gluIFD3′ (CCTTG CAACC AATTT TTAAA TCAAG GTCGA CGAGA TGCTG AGGAG). The PCR product was digested with SalI (sites in each primer are underlined) and subjected to ligation. The resulting gpoA allele contains an in-frame deletion spanning residues 42 to 212 (gpoAΔ42–212). This allele was then inserted between the XhoI and HindIII sites of the E. coli-streptococcal shuttle vector pJRS233, which was used to replace the mutant allele with the wild-type allele in two streptococcal strains as described above. The mutant alleles and chromosomal structures were confirmed by PCR and hybridization analysis.

For construction of an ahpC-gpoA double mutant, an internal region of the gpoA gene was amplified by PCR using the primers 5Gpo (GTCAC ATGCC GAATT CCTAT GATTT TACGG) and 3Gpo (CCATT CACTT TGAAT TCTGC AAAGC GAGGG). This product was digested with the restriction enzyme EcoRI (sites in each primer are underlined) and inserted into the EcoRI site of the integrational vector pCIV2 (41) to produce pKK15. Introduction of pKK15 into ahpC mutant HAHP resulted in the insertional inactivation of gpoA and generated the double mutant HAG. An ahpC-gpoA double mutant was constructed in a JRS4 background by sequential replacement of the ahpC and gpoA alleles with their mutant counterparts as described above (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

S. pyogenes strains

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Characteristic | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSC5 | Wild type | 26 | |

| HAHP | ahpCΔ133–292 | ahpC inactivated in HSC5 | This work |

| HGLT | gpoAΔ42–212 | gpoA inactivated in HSC5 | This work |

| HAGa | ahpCΔ133–292gpoAΩpKK15 | gpoA inactivated in HAHP | This work |

| JRS4 | Wild type | 49 | |

| JAHP | ahpCΔ133–292 | ahpC inactivated in JRS4 | This work |

| JAG | ahpCΔ133–292gpoAΔ42–212 | ahpC and gpoA inactivated in JRS4 | This work |

| HΔPer | perRΔ1–198 | perR inactivated in HSC5 | This work |

Strained derived by integration of the given plasmid into the indicated strain.

Disruption of perR.

An in-frame deletion in the gene encoding PerR was constructed using an approach similar to that used to disrupt gpoA. An 880-bp region corresponding to the entire perR coding region was amplified from HSC5 chromosomal DNA by PCR using primers: 5PerIXhoI′ (CGTTT CAAAA TCCCT CGAGG ATGTC CTAAA AGC) and 3PerSacI′ (GGGAT ACGCG TGAGC TCATA ACCTG TTTG). This PCR product was digested using the restriction enzymes XhoI and SacI (sites in primers underlined) and inserted into the corresponding restriction sites in a commercial vector (pCR2.1; Invitrogen) to produce pKK12. Inside-out PCR was performed on pKK12 using primers 5Per2SalI′ (GAGCC TTTGC CACAG TCGAC AATAA TTTG) and 3Per2SalI′ (GTGAA TGAAT GTCGA CAAGC TGCTA CTCC), and the product was digested with SalI (sites in each primer are underlined) and subjected to ligation. The resulting perR allele contains an in-frame deletion spanning residues 1 to 66 (perRΔ1–198), including the initial methionine residue and most of the putative DNA-binding region of the protein. This allele was then inserted into the HindIII site of the E. coli-streptococcal shuttle vector pJRS233, which was used to replace the mutant allele with the wild-type allele in two streptococcal strains as described above. The mutant alleles and chromosomal structures were confirmed by PCR.

Construction of reporter plasmids.

A 1.1-kb genomic fragment upstream and including the first 10 codons of ahpC were amplified by PCR using the primers 5AhpPro (CCTTG TGCCA TATGG ATCCA CTTCC TTTC) and 3AhpPro (GCTTG AGCTG AGAAT TCAGC AATTT CTTAT CC) (see Fig. 1). This region included all of the intervening sequence between ahpC and the next upstream and divergently transcribed open reading frame that showed homology to a cold shock protein E gene. Similarly, the 335-bp genomic fragment upstream and including the first 35 codons of the oligoendopeptidase F gene that immediately precedes gpoA in an apparent operon were amplified using the primers 5GpxPro (CCTAA ATAAT CAGGA TCCGT ATTAT TTTGA) and 3GpxPro2 (GAACG TTTTT TGAAT TCCAT AGTTG TCTCC TAAAC) (see Fig. 2). This region includes the intervening region between the oligoendopeptidase gene and the upstream and divergently transcribed phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase gene. The 411-bp genomic fragment upstream of and including the first 36 codons of mrgA was amplified using the primers 5MrgPro (CTCTT GACCA TTATC AGGAT CCTAA AGTAG) and 3MrgPro (GCCAC AGAGA ATTCA GCGAC AGCTT AGTTT AAAAC). This fragment encompasses the entire region between MrgA and a divergent upstream open reading frame with homology to a type 4 prepilin-like peptidase gene. Each primer contained either a BamHI or EcoRI restriction site (underlined). In addition, the 3′ primers contained a stop codon in the relevant reading frame to prevent translational fusions with the reporter (boldface). These PCR products were inserted between the EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites of pABG5 (24) to place the fragment upstream of phoZF, which encodes a secreted reporter with alkaline phosphatase activity (24). These plasmids were confirmed by determination of the insert DNA sequence and are hereafter referred to as pAhpPho, pGpoPho, and pMrgPho, respectively.

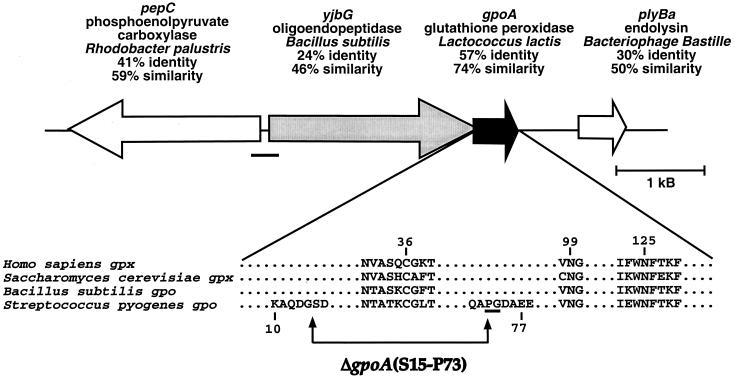

FIG. 2.

Glutathione peroxidase gene in S. pyogenes. The position and direction of gpoA is shown relative to its upstream neighbor. The percent amino acid identity and similarity for the closest match found in a TBlastN search are shown. The region inserted into the reporter plasmid for expression studies is underlined. Below is a partial alignment of four glutathione peroxidase genes, showing the conserved cysteine (C36), asparagine (N99), and C-terminal region (including N125). The region of the in-frame deletion is indicated by arrows. In the process of making the deletion, a proline and a glycine (underlined) were replaced by arginines.

Expression of ahpC and gpoA.

The ahpC, gpoA, and mrgA reporter plasmids constructed in the previous section were introduced into various S. pyogenes hosts and used to assess expression in the presence or absence of inducing concentrations of H2O2 (50 μM), ethanol (5%), cumene hydroperoxide (0.025%), or methyl viologen (10 mM). Activities of the various reporters were also compared between the wild type and perR mutants. The plasmids pABG5, in which a rofA promoter controls phoZF, and pABG6, a derivative of pABG5 in which the rofA promoter has been inactivated, were used in parallel experiments as positive and negative controls, respectively (24). Expression was monitored by determination of alkaline phosphatase activity in cell-free culture supernatants as described previously (24).

Analysis of methyl viologen sensitivity.

Sensitivity to the oxidative-stress-promoting compound methyl viologen (paraquat) was evaluated as follows. Methyl viologen (Sigma) was added to liquid THY medium up to a final concentration of 10 mM. This medium was then inoculated with 5 μl of an overnight culture grown in near-anaerobic conditions. The culture density was determined by measuring the absorbance (optical density at 600 nm [OD600]) after static incubation for 18 h at 37°C. The same analysis was conducted in the presence of catalase (1 mg/ml; Sigma) or in the presence of hemoglobin (1 mg/ml; Sigma). The activity of superoxide dismutase in S. pyogenes was assayed as previously described (22).

Sensitivity to peroxides.

The strain of interest was cultured under near-anaerobic conditions to mid-log phase and a 50-μl aliquot was spread evenly over the surface of a THY agar plate. A 10-μl aliquot of various concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (Sigma) diluted in water or cumene hydroperoxide (Sigma) at a concentration of 20% (vol/vol [in ethanol]) was then added to a sterile 10-mm-diameter filter disk placed at the center of each plate. After incubation at 37°C for 16 h under aerobic conditions, the area of the zone of inhibition was calculated for each mutant and compared to that of the respective wild-type strain.

Characterization of resistance to hydrogen peroxide challenge.

The ability of various strains to survive a lethal challenge by H2O2, with or without prior H2O2 exposure, was determined as follows: a 10-μl aliquot of an anaerobic overnight liquid culture was used to inoculate 10 ml of medium which was then incubated under near-anaerobic conditions at 37°C. When the absorbance (OD600) of this culture reached 0.040, H2O2 was added to a sublethal concentration (50 μM), and the incubation continued until the OD600 reached 0.070. At this time, H2O2 was added to a final concentration of 4 mM. After an additional 3 h of incubation, the number of CFU was determined under anaerobic conditions. The relative survival was calculated by the method of Rallu et al. (46) as the percentage of bacteria surviving 3 h after lethal challenge divided by the percentage of wild-type nonpretreated bacteria surviving 3 h after challenge. The ability of other agents to induce resistance to H2O2 was assessed by substitution of the initial inducing dose of peroxide with either ethanol (5% [vol/vol]), nalidixic acid (250 μM; Sigma), or mitomycin C (200 nM; Sigma). The inducing dose used for each agent represents the highest concentration of that agent which did not inhibit bacterial growth during an overnight incubation under near-anaerobic conditions. For comparison, the sensitivity of E. coli CH734 to H2O2 was determined using the same assay except that Luria-Bertani medium was substituted for THYB. The data reported represent the mean and standard error of the mean derived from at least two independent experiments, each of which was conducted in triplicate.

In selected experiments, the viability of cultures was assessed by using a vital stain (Live/Dead Cell Viability Kit; Molecular Probes) and microscopic observation or by determining numbers of CFU following brief sonication (Branson model W-185, 22°C, microprobe at setting of 6, five bursts of 5 s each) to disrupt the streptococcal chains. However, since the differences between viable cells counted before or after challenge were similar to that derived by the direct determination of CFU, neither procedure was routinely performed.

RESULTS

Identification of peroxidases in the S. pyogenes genome.

Since S. pyogenes lacks catalase, we hypothesized that it contains an alternative peroxidase. The available S. pyogenes genome information was evaluated for the presence of potential homologues to other known bacterial peroxidases (see Materials and Methods). Only three sequences in the S. pyogenes genome database showed significant homology to the peroxidase genes used in the searches (P < 0.05). The first sequence appeared homologous to NADH peroxidase (GenBank accession no. 1942624) of B. subtilis; however, genetic and biochemical studies have identified this gene as NADH oxidase (21). Of the other two open reading frames identified, the first showed homology to the peroxidase subunit of alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (ahpC) (17) (see Fig. 1). Subsequently, the reading frame downstream of this ahpC homologue was found to be similar to ahpF. In B. subtilis, these two genes encode a two-subunit protein complex and are known to form an operon (3). The other open reading frame identified showed homology to the glutathione peroxidase (gpoA) of Lactococcus lactis (see also Fig. 2). In addition to a high overall level of homology, each of these two putative peroxidases contained highly conserved residues located in the active sites of these enzymes known to be essential for their respective peroxidase activities (Fig. 1 and 2).

Construction of mutants.

In order to analyze the contribution of these putative peroxidases to the aerobic growth of S. pyogenes, we constructed mutants in which these genes were inactivated. Since it was anticipated that these mutants may have growth defects and since the transcriptional organization of these loci has not been characterized, in-frame deletions were constructed to create stable nonpolar mutations. For alkyl hydroperoxide reductase, a deletion was introduced into ahpC which removed 45 amino acids from the central region of the polypeptide that was anchored amino terminally in a highly conserved domain immediately adjacent to the putative active site residue C46 (Fig. 1). For gpoA, a region encompassing 57 amino acid residues was removed, including a cysteine (C36) and the highly conserved residues surrounding it that are constituents of the active site (Fig. 2) (17). These mutations were introduced into two unrelated strains of S. pyogenes (JRS4 and HSC5) to construct mutants defective in one or both of these peroxidases (Table 1).

Characterization of stress phenotypes.

Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase catalyzes the pyridine nucleotide-dependent reduction of organic hydroperoxides and H2O2 (43). Recent evidence also implicates these proteins in enzymatic defense against reactive nitrogen species (9). Mutants lacking functional AhpC or AhpF in some other organisms are hypersensitive to organic hydroperoxides such as cumene hydroperoxide (3). The S. pyogenes ahpC mutants were examined for a similar phenotype in a disk diffusion assay which revealed an enhanced sensitivity to cumene hydroperoxide, with zones of growth inhibition approximately 130% larger than those of the wild type when tested over a broad range of concentrations (5 to 20% cumene hydroperoxide). Glutathione peroxidases have been best characterized from mammalian cells and are also thought to provide protection from both H2O2 and organic hydroperoxides (18, 49). Their function in prokaryotic cells has been less well studied; however, glutathione peroxidase-defective mutants of Neisseria meningitidis are hypersensitive to oxidative stress induced by methyl viologen (40). Similarly, gpoA mutants of S. pyogenes demonstrated an enhanced sensitivity to methyl viologen which was apparent as the inability to grow in the presence of a concentration of methyl viologen that did not affect the growth of the wild-type strain (see below). Strains with mutations in ahpC also demonstrated this sensitivity (see below).

Growth phenotypes of peroxidase mutants.

The gram-positive bacterium B. subtilis contains both a catalase and an alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (5). Mutations in the genes encoding either peroxidase have no effect on the ability of the organism to grow under aerobic conditions (5). However, a mutant that is simultaneously defective for both grows very poorly aerobically (5). Since S. pyogenes is naturally catalase deficient, it was expected that an ahpC mutant would be equivalent to the B. subtilis peroxidase double mutant and would demonstrate poor aerobic growth characteristics. However, the S. pyogenes ahpC mutants did not demonstrate any observable growth restrictions when examined under several types of aerobic culture, including culture on solid medium in ambient air and culture in liquid medium in a shaking flask (data not shown). In addition, the ahpC mutants did not demonstrate any increased sensitivity to H2O2 when analyzed both by a disk diffusion assay and by determination of MICs (data not shown). Identical results were obtained for gpoA-deficient mutants.

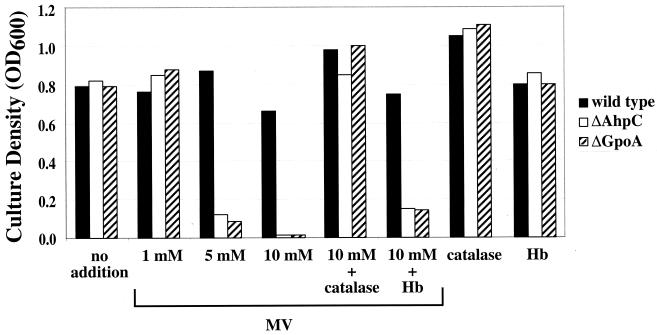

Peroxidase mutants are sensitive to methyl viologen.

Although the various peroxidase mutants were proficient for growth under aerobic conditions, they did demonstrate sensitivity to certain forms of extreme oxidative stress. Specifically, when cultured in the presence of a concentration of methyl viologen that has minimal impact on the growth of the wild-type strains (10 mM) neither the ahpC- nor the gpoA-deficient mutants demonstrated any detectable growth (Fig. 3). The ahpC gpoA double mutant was even more sensitive to methyl viologen than the single mutants, with no growth at a concentration of 1 mM (data not shown). Methyl viologen acts to increase intracellular levels of superoxide (27). Since mutants expressed superoxide dismutase at levels equivalent to those for the wild-type cells (data not shown), it is unlikely that superoxide is the source of lethal stress to the mutants. Rather, since H2O2 is a product of the dismutation of superoxide, high levels of superoxide could also result in increased concentrations of H2O2 and, in turn, other reactive species generated from the reaction of H2O2 with a variety of substrates. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that the addition of catalase could rescue the growth of the peroxidase mutants in the presence of methyl viologen, but the same effect was not seen with the addition of hemoglobin (Fig. 3). A small stimulation of growth above background values in the presence of methyl viologen was observed when hemoglobin was added (Fig. 3), which may be due to the weak peroxidase activity of hemoglobin (20). These data indicate that AhpC and GpoA contribute to defense under conditions of extreme and continuous oxidative stress and that both peroxidase gene products are required for optimal resistance.

FIG. 3.

Methyl viologen sensitivity of ahpC and gpoA mutants. Methyl viologen (MV) sensitivity of ahpC and gpoA mutants. The growth of HSC5 (wild type), HAHP (ΔAhpC), and HGLT (ΔGpoA) in the absence (no treatment) or presence of the indicated concentrations of methyl viologen are shown. Where indicated, cultures were supplemented with catalase or hemoglobin (see Materials and Methods). Growth was measured by determining the OD600 after 18 h of incubation. A representative experiment is shown. Similar experiments were done with HAG, JRS4, and mutants derived from JRS4 (JAHP, JGLT, and JAG, see Table 1), with similar results.

AhpC and GpoA are not required for an induced resistance to peroxide.

The observation that neither AhpC nor GpoA were required for normal growth under aerobic conditions suggested that S. pyogenes may have alternative strategies for resistance to peroxide. To examine this question, the kinetics of interaction with peroxide were examined in greater detail. When a culture of a wild-type strain was challenged at mid-log phase (approximately 106 CFU) with 4 mM H2O2 and the number of CFU was examined after 2 h, it was observed that the number of viable CFU decreased ca. 0.4 log. When examined at 3 h, the number of viable CFU had decreased by >3.0 log (data not shown). These values were actually less than those obtained for a culture of E. coli CH734 under these same conditions, for which the number of CFU decreased by about 2.0 log after 2 h and >4 log after 3 h (data not shown). These data suggest that, under these conditions, S. pyogenes is not hypersensitive to peroxide compared to E. coli, a catalase-containing bacterium. Furthermore, when ahpC and gpoA mutants were examined, instead of demonstrating an enhanced sensitivity, they were in fact more resistant to peroxide challenge, with viability decreasing by only about 1.5 log 3 h after challenge (data not shown). A similar phenomenon has been reported for alkyl hydroperoxide reductase-deficient mutants of B. subtilis, where it appears that inactivation of the ahpC results in low-level oxidative stress sufficient to induce an adaptive resistance response to peroxide (3).

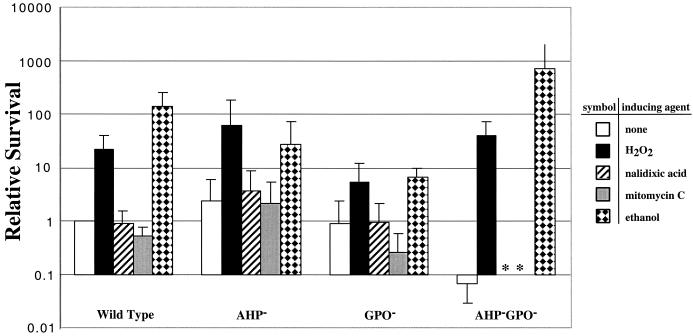

These data suggest that S. pyogenes may also possess an adaptive resistance response to peroxide. To test this, growing cultures were treated with a sublethal dose of H2O2 (50 μM) 1 h prior to challenge with a lethal dose (4 mM). As before, viability was examined after an additional 3 h of incubation. When treated in this fashion, wild-type strains were >100-fold more resistant to lethal peroxide challenge (Fig. 4; wild type, H2O2 induction). Similar to the wild type, both ahpC and gpoA mutants were protected by pre-exposure to a sublethal concentration of H2O2 (Fig. 4; AHP−, H2O2 induced; GPO−, H2O2 induced). Bacteria containing mutations in both ahpC and gpoA were approximately 10 times more sensitive to peroxide challenge than wild-type bacteria (Fig. 4; AHP−GPO−, no induction). Nonetheless, the double mutants demonstrated a striking resistance response; when pretreated with sublethal peroxide, they were up to 1,000 times more resistant to lethal peroxide challenge than without pretreatment (Fig. 4; AHP−GPO−, H2O2 induced). Taken together, these data indicate that S. pyogenes can mount a vigorous adaptive response to peroxide stress and that this response does not require the contributions of AhpC or GpoA.

FIG. 4.

Induction of resistance response by hydrogen peroxide and ethanol. Bacterial cultures were induced with a sublethal dose of hydrogen peroxide before challenge with a lethal dose. The relative survival was calculated as the percentage of CFU after lethal peroxide challenge divided by the percentage of wild-type cells surviving the same challenge (black bars). Some cultures were not induced before challenge. Other cultures were induced with agents other than hydrogen peroxide (as indicated) before lethal challenge with H2O2. Each bar represents the average of at least two independent experiments, each done in triplicate. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

As an additional test for involvement of AhpC and GpoA in inducible peroxide resistance, we studied expression of the peroxidase genes. Reporter plasmids were constructed by inserting the genomic regions upstream of ahpC and gpoA before a promoterless alkaline phosphatase reporter. Expression of the two reporter alleles in S. pyogenes was comparable with that of the well-characterized rofA promoter in this vector, indicating that functional promoters were identified by this analysis. However, expression of the ahpC and gpoA reporters did not increase in wild-type cells in the presence of inducing levels of H2O2 or ethanol (data not shown). In addition, alkaline phosphatase activity from both reporters was not higher in wild-type cells that were incubated in the presence of 10 mM methyl viologen or 0.025% cumene hydroperoxide (data not shown). These findings lend further support to the observation that AhpC and GpoA are not part of the adaptive response to peroxide stress.

Peroxide resistance can be induced by ethanol.

Insight into the pathway which controls an adaptive response can often be gained from an examination of whether the response is induced by a specific stress or whether other stress-promoting agents can induce the protective response against the agent of interest (19). The SOS response is a highly regulated response involved in resistance to agents which damage DNA, including H2O2 (56). However, treatment with two different agents known to induce the SOS response (mitomycin C and nalidixic acid) (56) resulted in a level of killing by H2O2 that did not differ from untreated cultures (Fig. 4; compare wild type uninduced to treatment with nalidixic acid or mitomycin C). Similar results were obtained in parallel experiments with the ahpC and gpoA mutants (Fig. 4). In contrast, treatment with a sublethal concentration of ethanol (5% [vol/vol]) was highly effective at inducing a protective response to subsequent challenge with a lethal dose of peroxide in wild-type bacteria and in both peroxidase mutants (Fig. 4). In fact, under these conditions, ethanol was a more effective inducing agent than H2O2 itself (Fig. 4, wild type).

S. pyogenes may lack ςB.

In gram-positive bacteria, a large number of stress-induced genes are regulated by a pathway known as the general stress response (53). Since induction by ethanol is a signature of the general stress response (52), the possibility existed that the observed adaptive response to H2O2 was a manifestation of this pathway. A key element in the regulation of the general stress response is the alternative sigma factor ςB and its interaction with the anti-sigma factor RbsW (25, 53). This sigma factor is highly conserved among gram-positive organisms, including S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, and B. subtilis (36, 53, 54). The genes encoding ςB in each of these three species are between 59 and 66% identical at the amino acid level. However, when the available S. pyogenes genome information was examined, there were no sequences with significant (P < 0.33) similarity to the S. aureus ςB gene other than the housekeeping sigma factor ςA. Similarly, no clear homologues to other elements of the ςB pathway were apparent, including RsbU and RsbW. As an alternative approach, primers for PCR amplification were designed based on an examination of highly conserved elements of the ςB gene sequence. While a PCR product of the expected size was amplified using these primers from several different gram-positive organisms, no product was amplified when the chromosome of S. pyogenes strains that display the adaptive response was used as a template (data not shown). These data indicate that while the adaptive response of S. pyogenes to peroxide shares many phenotypic characteristics of the general stress response, the ςB pathway is either highly divergent or may be missing altogether.

Regulation of the inducible peroxide resistance response involves PerR.

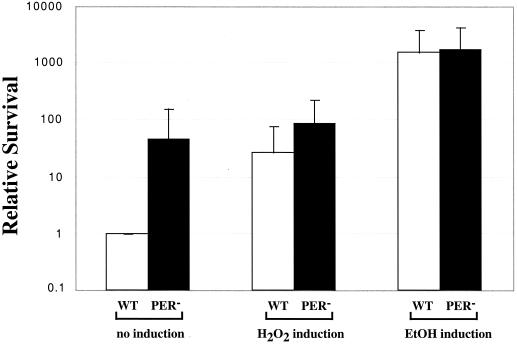

In addition to the ςB general stress pathway, B. subtilis also harbors a specific response to hydrogen peroxide stress. The peroxide-sensitive PerR regulon in that species is known to take part in the transcriptional regulation of peroxidases such as catalase and alkyl hydroperoxidase and of protective proteins such as MrgA, a DNA-binding protein (4, 10). Mutational analyses have indicated that PerR is a negative regulator of katA, ahpC, and mrgA expression in B. subtilis. Notably, mutants lacking PerR were found to be hyper-resistant to hydrogen peroxide in a disk diffusion assay. Examination of the genome information and other published work suggests that S. pyogenes contains homologues for perR and mrgA in addition to ahpC (4). To analyze the role of PerR, we constructed an in-frame deletion that removes the N-terminal one-third of perR, including a region that encodes most of the putative DNA-binding region of the protein (Fig. 5). The resulting mutant HΔPer proliferated as well as the wild type in aerobic growth conditions; however, no significant derepression of the ahpC, gpoA, and mrgA reporter constructs were observed in HΔPer compared to the wild type (data not shown). These findings indicate that, in contrast to what has been shown in B. subtilis, PerR does not appear to repress transcription of ahpC, gpoA, and mrgA in S. pyogenes. However, the PerR mutant was derepressed for the inducible peroxide resistance response and survived lethal hydrogen peroxide challenge approximately 100 times better than the wild-type cells, even without preinduction with a sublethal dose of hydrogen peroxide or ethanol (Fig. 6). Interestingly, while the high level of resistance in the PerR mutant was not affected by pretreatment with peroxide, an additional level of resistance to lethal peroxide challenge could be induced by ethanol (Fig. 6). This observation is consistent with the observation that ethanol consistently induced higher levels of resistance to peroxide than did peroxide itself (see above) and suggests that the response induced by ethanol includes an additional regulatory component independent of PerR.

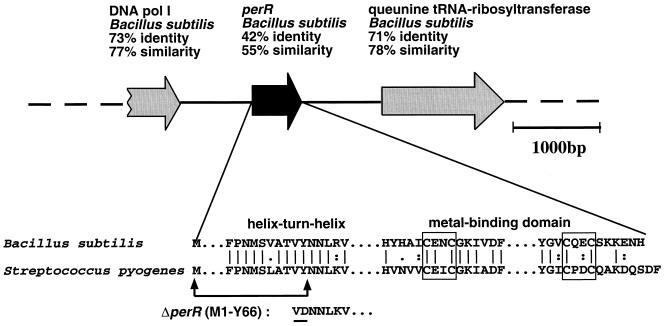

FIG. 5.

Gene encoding PerR in S. pyogenes. The position and direction of perR are depicted relative to its neighbors in the genome as published by the Sanger Centre. This chromosomal structure is similar to that of the strains used in this study but is different from that of the M1 strain published by the University of Oklahoma. The percent amino acid identity and similarity to the closest match found by a TBlastN search are shown. Below is a partial alignment of the S. pyogenes perR gene with the B. subtilis homologue. Regions around the conserved putative helix-turn-helix DNA binding site and the putative metal-binding domain are shown. Two conserved CXXC putative metal-binding site motifs are shown in boxes. The 66-amino-acid region removed by deletion is indicated by the arrows. In the process of making the deletion, a valine and a tyrosine were replaced by a valine and an aspartic acid (underlined).

FIG. 6.

PerR is important for the inducible peroxide resistance response. The HΔPer mutant was compared to wild-type cells for the inducible peroxide resistance response. The relative survival was calculated as described in Fig. 4. Data for the wild type are shown in white; data for the HΔPer mutant are shown in black. The data represent the average of eight independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

DISCUSSION

We employed functional genomics to investigate the mechanisms of defense against toxic oxygen species in the lactic acid bacterium S. pyogenes. Using this approach, we have shown that while alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpC) and glutathione peroxidase (GpoA) contribute to resistance against methyl viologen and cumene hydroperoxide, neither enzyme is required for growth under aerobic conditions or for the ability of S. pyogenes to mount an induced response to peroxide stress. We have also found that the induced response shares many characteristics with the ςB general stress response pathway but that S. pyogenes may lack ςB. On the other hand, we have discovered that PerR is a negative regulator of the inducible peroxide resistance response. However, studies of ahpC and gpoA expression indicate that these genes are not induced under the conditions that lead to peroxide resistance, nor are they repressed by PerR. Collectively, these observations suggest that in S. pyogenes PerR may repress genes encoding novel mechanisms of peroxide resistance.

Further support for the involvement of a novel mechanism comes from comparison of these data to similar studies conducted in the gram-positive bacterium B. subtilis. For example, B. subtilis mutants deficient in either the catalase encoded by katA or the oxidoreductase encoded by ahpC grow normally under aerobic conditions (5). However, a katA ahpC double mutant exhibits a number of striking phenotypes, including slow growth in liquid media and accelerated lysis on certain solid media (5). Significantly, while the Bacillus double mutant can grow as well as the wild type under microaerobic conditions on rich medium, it grows very poorly under these conditions on minimal medium and fails to grow at all under normal aerobic conditions (5). Since S. pyogenes is naturally catalase deficient, the observation that the ahpC mutant is not defective for growth suggests that S. pyogenes has alternative strategies for management of peroxide stress.

This possibility is also supported by the recent observation that S. mutans mutants lacking AhpC activity grow well aerobically (30). Furthermore, the fact that neither the gpoA mutant nor the ahpC gpoA double mutant were defective for aerobic growth suggests that glutathione peroxidase is not essential for this phenotype. A recent report also showed that S. mutans mutants lacking AhpC or AhpF were not hypersensitive to cumene hydroperoxide (30). These data contrast with data showing that B. subtilis ahpC mutants are 20 to 50 times more sensitive than the wild type to cumene hydroperoxide (3). As mentioned above, our data indicate that S. pyogenes ahpC gpoA mutants are only slightly more sensitive to cumene hydroperoxide than is the wild type, again suggesting a possible alternate mechanism for peroxide resistance in streptococci.

While resistance to peroxide has not been well studied in most lactic acid species, mechanisms of aerotolerance appear to be diverse among this family, and novel mechanisms of defense against peroxide are not unprecedented. For example, one species of lactobacilli (Lactobacillus sake) produces a catalase that utilizes heme scavenged from the organism's environment (35). A second lactobacillus species, Lactobacillus plantarum, harbors a pseudocatalase that uses two manganese atoms in place of heme at its active site (32). In Enterococcus faecalis, a cystinyl redox center-containing NADH peroxidase has been well characterized (55), and several oral streptococcal species, including Streptococcus gordonii, contain a gene with homology to the periplasmic thiol peroxidase of E. coli (7). As noted above, examination of the available genome information failed to reveal any clear homologues of these other classes of peroxidases in S. pyogenes. However, given this diversity in mechanisms of achieving aerotolerance among lactic acid bacteria, it is not unreasonable to expect that S. pyogenes may have evolved other unique and as-yet-uncharacterized pathways for dealing with oxidative stress.

Identification of such alternative strategies will be facilitated by our studies of the PerR homologue in S. pyogenes. Even though the peroxidases known to be repressed by PerR in B. subtilis, namely, katA and ahpC, are not involved in the inducible response to hydrogen peroxide in S. pyogenes, mutants lacking the PerR homologue are constitutively resistant to hydrogen peroxide challenge. This finding suggests that PerR represses alternate genes important for the inducible response. MrgA has been shown to be essential for ςB-dependent resistance to oxidative stress in that species (2). However, our in vivo expression studies suggest that PerR is not an important regulator for MrgA in S. pyogenes. PerR itself is a transcription repressor with homology to the iron-sensitive Fur protein of E. coli (4) and binds to a well-conserved operator sequence in its target promoters (“Per box”) in B. subtilis (4, 11). This sequence can be found in the promoter regions of genes repressed by PerR in that species, including katA, ahpC, and mrgA. However, a search for Per boxes in ahpC and mrgA of S. pyogenes did not reveal any such sequences, which is likely a significant observation given that the putative DNA binding regions of PerR in S. pyogenes and B. subtilis are identical at 12 of 13 positions (4). Thus, the targets of PerR-dependent gene repression have not yet been determined. Identification of such targets in S. pyogenes will provide further insight about potentially novel effectors of protection against hydrogen peroxide.

The ability of ethanol to induce resistance to peroxide provides some insight into the regulation of this response. Stress responses in prokaryotes are known to involve redundant and overlapping functions. For example, in E. coli, hydrogen peroxide exposure leads to the expression of a number of proteins, some of which are also induced as part of the heat shock response. However, the peroxide response regulon also includes several proteins not regulated by the heat shock regulon (12, 19). In gram-positive bacteria, induction by ethanol is commonly used as a probe for regulation by the ςB-dependent general stress response (25, 53). This regulon is widely distributed among pathogenic gram-positive bacteria, including Staphylococcus and Listeria spp. (8, 54). However, our examinations using several different criteria, including examination of the database for the ςB gene, ςB promoters, and genes which regulate ςB and PCR analyses, suggest that S. pyogenes may lack a clear homologue of ςB. In B. subtilis, a few stress response genes that are induced by multiple stresses are regulated independently of ςB (29). These include the heat shock genes regulated by the CIRCE element (29) and the genes for the various Clp-family proteases that are regulated by the recently described transcription repressor CtsR (15). However, there is no evidence that the genes regulated by these responses specifically play major roles in resistance to peroxide.

The ahpC and gpoA mutants are sensitive to high-level oxidative stress in the form of challenge with methyl viologen but are not more sensitive to hydrogen peroxide in a disk diffusion or MIC assay. This apparent contradiction may be due to the fact that methyl viologen catalyzes the continuous production of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in the culture medium, whereas exogenously added hydrogen peroxide is reduced over time. In addition, our findings suggest that different mechanisms of resistance may be involved in protection from different levels of stress. The notion of a response tailored to the degree of stress is consistent with studies suggesting that different levels of peroxide generate different types of cellular damage in E. coli (28, 33). Peroxide killing is bimodal with respect to peroxide concentration in E. coli, where it appears that low-level hydrogen peroxide exposure leads to DNA damage, whereas high levels of hydrogen peroxide may directly oxidize some other cellular target (28, 33). Damage to different constituents would likely require different types of repair and/or resistance mechanisms. The existence of multiple pathways in S. pyogenes is suggested by the observation that ethanol can induce an additional degree of resistance in PerR mutants.

The regulation and manifestation of resistance to oxidative stress in S. pyogenes appear to involve several novel features. Since streptococcal lesions in tissue are highly inflammatory and since the production of toxic oxygen species is an important component of the inflammatory response, the inducible response may serve as a virulence determinant that specifically allows the bacterium to survive oxidative stresses encountered in the host environment. Further work is being undertaken to characterize the components of this system and to understand its importance in bacterial survival and virulence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Emil Unanue and Brian Edelson for the Listeria strains and Tim Foster for the Staphylococcus strains. We also thank Bernard Beall for his interest in these studies.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI38273 (M.G.C.) and NIH grant 5-T32-GM7200 (K.Y.K.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antelmann H, Engelmann S, Schmid R, Sorokin A, Lapidus A, Hecker M. Expression of a stress- and starvation-induced dps/pexB-homologous gene is controlled by the alternative sigma factor sigmaB in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7251–7256. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7251-7256.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antelmann H, Engelmann S, Schmid R, Hecker M. General and oxidative stress responses in Bacillus subtilis: cloning, expression, and mutation of the alkyl hydroperoxide reductase operon. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6571–6578. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6571-6578.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bsat N, Herbig A, Casillas-Martinez L, Setlow P, Helmann J D. Bacillus subtiliscontains multiple Fur homologues: identification of the iron uptake (Fur) and peroxide regulon (PerR) repressors. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:189–198. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bsat N, Chen L, Helmann J D. Mutation of the Bacillus subtilisalkyl hydroperoxide reductase (ahpCF) operon reveals compensatory interactions among hydrogen peroxide stress genes. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6579–6586. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6579-6586.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caparon M G, Scott J R. Genetic manipulation of the pathogenic streptococci. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:556–586. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04028-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cha M K, Kim H K, Kim I H. Mutation and mutagenesis of thiol peroxidase of Escherichia coliand a new type of thiol peroxidase family. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5610–5614. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5610-5614.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan P F, Foster S J, Ingham E, Clements M O. The Staphylococcus aureusalternative sigma factor ςB controls the environmental stress response but not starvation survival or pathogenicity in a mouse abscess model. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6082–6089. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6082-6089.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, Xie Q W, Nathan C. Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C (AhpC) protects bacterial and human cells against reactive nitrogen intermediates. Mol Cell. 1998;1:795–805. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen L, Helmann J D. Bacillus subtilisMrgA is a Dps(PexB) homologue: evidence for metalloregulation of an oxidative-stress gene. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:295–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18020295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen L, Keramati L, Helmann J D. Coordinate regulation of Bacillus subtilisperoxide stress genes by hydrogen peroxide and metal ions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8190–8194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christman M F, Morgan R W, Jacobson F S, Ames B N. Positive control of a regulon for defenses against oxidative stress and some heat-shock proteins in Salmonella typhimurium. Cell. 1985;41:753–762. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Condon S. Responses of lactic acid bacteria to oxygen. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1987;46:269–280. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deisseroth A, Dounce A L. Catalase: physical and chemical properties, mechanism of catalysis, and physiological role. Phys Rev. 1970;50:319–375. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1970.50.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Derré I, Rapoport G, Msadek T. CtsR, a novel regulator of stress and heat shock response, controls clpand molecular chaperone gene expression in gram-positive bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:117–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duthie S, Lorenz L L. Staphylococcal coagulase: mode of action and antigenicity. J Gen Microbiol. 1952;6:95–107. doi: 10.1099/00221287-6-1-2-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellis H R, Poole L B. Roles for the two cysteine residues of AhpC in catalysis of peroxide reduction by alkyl hydroperoxide reductase from Salmonella typhimurium. Biochemistry. 1997;36:13349–13356. doi: 10.1021/bi9713658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans M V, Turton H E, Grant C M, Dawes I W. Toxicity of linoleic acid hydroperoxide to Saccharomyces cerevisiae: involvement of a respiration-related process for maximal sensitivity and adaptive response. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:483–490. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.483-490.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farr S B, Kogoma T. Oxidative stress responses in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:561–585. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.4.561-585.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabbianelli R A M S, Fedeli D, Kantar A, Falconi G. Antioxidant activities of different hemoglobin derivatives. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;242:560–564. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson C M, Mallett T C, Claiborne A, Caparon M G. Contribution of NADH oxidase to aerobic metabolism of Streptococcus pyogenes. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:448–455. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.2.448-455.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibson C M, Caparon M G. Insertional inactivation of Streptococcus pyogenes sod suggests that prtFis regulated in response to a superoxide signal. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4688–4695. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4688-4695.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonzalez-Flecha B, Demple B. Metabolic sources of hydrogen peroxide in aerobically growing Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13681–13687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.23.13681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Granok A B, Parsonage D, Ross R P, Caparon M G. The RofA binding site in Streptococcus pyogenesis utilized in multiple transcriptional pathways. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1529–1540. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1529-1540.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haldenwang W G. The sigma factors of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:1–30. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.1-30.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanski E, Horwitz P A, Caparon M G. Expression of protein F, the fibronectin-binding protein of Streptococcus pyogenes, JRS4, in heterologous streptococcal and enterococcal strains promotes their adherence to respiratory epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1992;60:5119–5125. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.12.5119-5125.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassan H M, Fridovich I. Intracellular production of superoxide radical and of hydrogen peroxide by redox active compounds. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1979;196:385–395. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(79)90289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hassett D J, Cohen M S. Bacterial adaptation to oxidative stress: implications for pathogenesis and interaction with phagocytic cells. FASEB J. 1989;3:2574–2582. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.14.2556311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hecker M, Schumann W, Völker U. Heat-shock and general stress response in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:417–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.396932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higuchi M, Yamamoto Y, Poole L B, Shimada M, Sato Y, Takahashi N, Kamio Y. Functions of two types of NADH oxidases in energy metabolism and oxidative stress of Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5940–5947. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.5940-5947.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ido E A M H. Construction of T-tailed vectors derived from a pUC plasmid: a rapid system for direct cloning of unmodified PCR products. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 1997;61:1766–1767. doi: 10.1271/bbb.61.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Igarashi T, Kono Y, Tanaka K. Molecular cloning of manganese catalase from Lactobacillus plantarum. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29521–29524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Imlay J A, Linn S. Bimodal pattern of killing of DNA-repair-defective of anoxically grown Escherichia coliby hydrogen peroxide. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:519–527. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.2.519-527.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ionesco H, Michel J, Cami B, Schaeffer P. Symposium on bacterial spores. II. Genetics of sporulation in Bacillus subtilisMarburg. J Appl Bacteriol. 1970;33:13–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1970.tb05230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knauf H J, Vogel R F, Hammes W P. Cloning, sequence and phenotypic expression of katA, which encodes the catalase of Lactobacillus sakeLTH677. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:832–839. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.3.832-839.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kullik I, Giachino P, Fuchs T. Deletion of the alternative sigma factor ςB in Staphylococcus aureusreveals its function as a global regulator of virulence genes. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4814–4820. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.18.4814-4820.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kushner S R. An improved method for transformation of Escherichia coli with ColE1-derived plasmids. In: Micosia H W B A S, editor. Genetic engineering. New York, N.Y: Elsevier-North Holland Biomedical Press; 1978. pp. 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lucey C A A S C. Active role of oxygen and NADH oxidase in growth and energy metabolism of Leuconostoc. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:1789–1796. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller R A, Britigan B E. Role of oxidants in microbial physiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:1–18. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore T D E, Sparling P F. Interruption of the gpxA gene increases the sensitivity of Neisseria meningitidisto paraquat. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4301–4305. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4301-4305.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okada N, Geist R T, Caparon M G. Positive transcriptional control of mryregulates virulence in the group A streptococcus. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:893–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perez-Casal J, Price J A, Maguin E, Scott J R. An M protein with a single C repeat prevents phagocytosis of Streptococcus pyogenes: use of a temperature-sensitive shuttle vector to deliver homologous sequences to the chromosome of S. pyogenes. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:809–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poole L B, Ellis H R. Flavin-dependent alkyl hydroperoxide reductase from Salmonella typhimurium. 1. Purification and enzymatic activities of overexpressed AhpF and AhpC proteins. Biochemistry. 1996;35:56–64. doi: 10.1021/bi951887s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Porter N A. Chemistry of lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:273–282. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Portnoy D A, Jacks P S, Hinrichs D J. Role of hemolysin for the intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenes. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1459–1471. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.4.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rallu F, Gruss A, Ehrlich S D, Maguin E. Acid- and multistress-resistant mutants of Lactococcus lactis: identification of intracellular stress signals. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:517–528. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruiz N, Wang B, Pentland A, Caparon M. Streptolysin O and adherence synergistically modulate proinflammatory responses of keratinocytes to group A streptoccci. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:337–346. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scott J R. A turbid plaque-forming mutant of phage P1 that cannot lysogenize Escherichia coli. Virology. 1972;62:344–349. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(74)90397-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sies H, Sharov V S, Klotz L, Briviba K. Glutathione peroxidase protects against peroxynitrite-mediated oxidations. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27812–27817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.VanHeyningen T, Fogg G, Yates D, Hanski E, Caparon M. Adherence and fibronectin binding are environmentally regulated in the group A streptococci. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:1213–1222. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Voelker U, Voelker A, Maul B, Dufour A, Haldenwang W G. Separate mechanisms activate ςB of Bacillus subtilisin response to environmental and metabolic stresses. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3771–3780. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.13.3771-3780.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Völker U, Engelmann S, Maul B, Riethdorf S, Völker A, Schmid R, Mach H, Hecker M. Analysis of the induction of general stress proteins of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 1994;140:741–752. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-4-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wiedmann M, Arvik T J, Hurley R J, Boor K J. General stress transcription factor ςB and its role in acid tolerance and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3650–3656. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3650-3656.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yeh J I, Claiborne A, Hol W G J. Structure of the native cysteine-sulfenic acid redox center of enterococcal NADH peroxidase refines at 2.8 Å resolution. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9951–9957. doi: 10.1021/bi961037s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ysern P, Clerch B, Castaño M, Gibert I, Barbé J, Llagostera M. Induction of SOS genes in Escherichia coli and mutagenesis in Salmonella typhimuriumby fluoroquinolones. Mutagenesis. 1990;5:63–66. doi: 10.1093/mutage/5.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]