Abstract

A search by subtractive hybridization for sequences present in only certain strains of Helicobacter pylori led to the discovery of a 2-kb transposable element to be called IS607, which further PCR and hybridization tests indicated was present in about one-fifth of H. pylori strains worldwide. IS607 contained two open reading frames (ORFs) of possibly different phylogenetic origin. One ORF (orfB) exhibited protein-level homology to one of two putative transposase genes found in several other chimeric elements including IS605 (also of H. pylori) and IS1535 (of Mycobacterium tuberculosis). The second IS607 gene (orfA) was unrelated to the second gene of IS605 and might possibly be chimeric itself: it exhibited protein-level homology to merR bacterial regulatory genes in the first ∼50 codons and homology to the second gene of IS1535 (annotated as “resolvase,” apparently due to a weak short recombinase motif) in the remaining three-fourths of its length. IS607 was found to transpose in Escherichia coli, and analyses of sequences of IS607-target DNA junctions in H. pylori and E. coli indicated that it inserted either next to or between adjacent GG nucleotides, and generated either a 2-bp or a 0-bp target sequence duplication, respectively. Mutational tests showed that its transposition in E. coli required orfA but not orfB, suggesting that OrfA protein may represent a new, previously unrecognized, family of bacterial transposases.

Insertion sequence (IS) elements are a diverse set of specialized DNA segments that can move to new sites in procaryotic and eucaryotic genomes without need for extensive sequence homology (for reviews, see references 6, 12, 16, and 21). They are diverse in sequence and probably phylogenetic origin, and in mechanism and control of transposition. One group of elements, which includes IS10 and IS50, specify just one transposase protein that acts on matched sequences at each IS element end (inverted repeats) to mediate transposition to new genomic locations. Other elements, such as Tn7, specify two different proteins that act together as the transposase, each performing an essential but distinct role in transposition. Additional Tn7-encoded proteins help select insertion sites and affect the efficiency of transposition, in part through interactions with host proteins (8, 25).

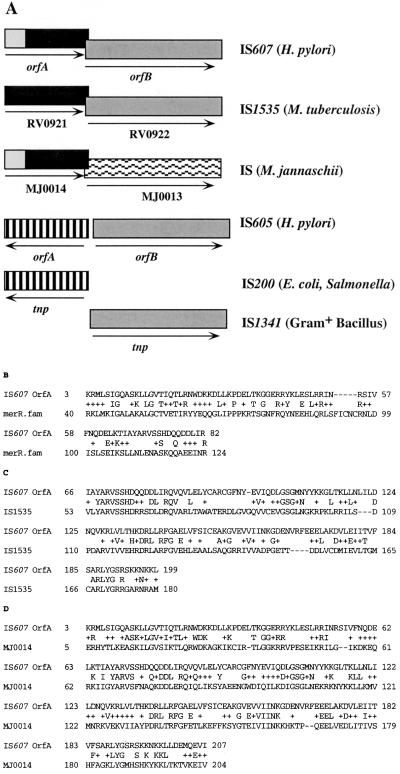

A third type of element is illustrated by IS605 (Fig. 1A), which contains two transposition-related genes that seem to be of different phylogenetic origin (14), in the sense that each has protein-level homology to the single putative transposase genes of other simpler IS elements. IS605 sequences were found in some one-third of Helicobacter pylori strains worldwide, and the two open reading frames (ORFs) were always associated as in Fig. 1A: no case of just one IS605 ORF without the other has been found (14). Formal models to explain such association included (i) OrfA and OrfB proteins serving together as the functional transposase; (ii) transposition mediated by just one of these proteins, but regulated (in terms of efficiency or specificity) by the other; or (iii) each protein mediating transposition in a different set of bacterial species (host range).

FIG. 1.

IS607 and related IS elements, including possibly chimeric origin of orfA. (A) Overview of structures. Boxes represent ORFs. These ORFs and portions of ORFs from different elements represent protein-level homologies (in range of 25% to 37% protein level identity in BLASTP [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/blast.cgi]). Of particular note are protein-level homologies between 5′ 60 amino acids of IS607 OrfA (accession no. AF189015) and entries annotated as MerR-type bacterial regulatory proteins (33% match, first 51 amino acids in the case of HI1623 [B]) and remainder of OrfA with putative resolvase of IS1535 of M. tuberculosis (C). The ORFs of MJ0014 and MJ0013 depicted here were annotated as function unknown (accession no. U67460). MJ0014 shares 37% identity with IS607 orfA overall (D), whereas MJ0013 is not related to IS607 orfB. (B) BLASTP alignment of N terminus of IS607 OrfA protein with MerR-type bacterial regulatory protein HI1623 from Haemophilus influenzae (accession no. C64133; 33% identity; best current match to this domain of IS607 OrfA). Motif searches using the pfam 5.3 program identified a match of IS607 OrfA to MerR regulatory protein family motifs in positions 9 to 44 with an E value of 3 e−10 (highly significant match). (C) BLASTP alignment of remainder of IS607 OrfA with corresponding region of the IS1535 resolvase (accession no. A70583; 34% identity). Also among entries with close homology to IS607 OrfA are proteins annotated as resolvase or resolvase-related from other species (e.g., an Acidianus ambivalens protein, accession no. CAB58176, 33% identity throughout; PAB2076 of Pyrococcus abyssi, accession no. B75156, 35% identity throughout). Motif searches using the pfam 5.3 program identified a match of IS607 OrfA to site-specific recombination protein at positions 66 to 76 with an E value of 0.0011, which, although better than that obtained using the IS1535 resolvase (E value of 0.22), is rather weak. (By contrast, IS607 OrfB was matched through much of its sequence to that of a canonical transposase family [positions 23 to 300; pfam E value of 7 e−50].) (D) BLASTP alignment of IS607 OrfA with M. jannaschii MJ0014, an ORF annotated as function unknown in the genome sequence (best current match to IS607 OrfA) (http://www.tigr.org/tdb/CMR/arg/htmls/SplashPage.html). It is noteworthy that the product of the adjacent gene (MJ0013), although related to putative transposases in BLASTP searches, is not detectably related to IS607 OrfB protein.

Interesting in this context is a cluster of IS elements represented by IS1535 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (11) (Fig. 1A). One IS1535 ORF (putative transposase) is a protein-level homolog of orfB of IS605 (22% identity), whereas the second ORF is not related to any suspected or known transposase; rather, this second ORF contains short weak matches to proteins known to function as site-specific recombinases and was annotated as “resolvase” in the M. tuberculosis genome sequencing project (11). Homologs of this putative resolvase are found in the genomes of diverse microbial species, often next to putative transposase genes that are not related (by BLAST homology search criteria) to orfB of IS605. It is important for the present report that “resolvase” in a transposable element context implies a protein that mediates site-specific recombination between direct repeats of its cognate recognition sequences—typically the breakdown into two separate complementary DNA molecules of cointegrates that are formed when transposition is replicative (26). Resolution is distinct from transposition, which involves movement of an element to new genomic sites.

The IS607 element of H. pylori described here contains two genes with protein-level homology to the two genes of IS1535. We found that IS607 can transpose in Escherichia coli, that it has a unique dinucleotide insertion specificity, and that its transposition in E. coli depends on orfA, not orfB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General methods.

Standard procedures were used for E. coli growth and for plasmid DNA isolation, DNA electrophoresis, and transformation of competent cells. E. coli was grown in L broth or on L agar (22), using antibiotics at the following concentrations (micrograms/milliliter) when needed: ampicillin (Amp), 100; chloramphenicol (Cam), 25; and streptomycin (Str), 150. Plasmid DNAs were isolated from E. coli using a Qiagen (Chatsworth, Calif.) prep spin miniprep kit. Standard methods were used for H. pylori growth on blood agar plates in a microaerobic atmosphere (5).

High-molecular-weight H. pylori and E. coli DNA was isolated by a hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide method (3). Restriction digestion and ligation were carried out as recommended by manufacturers (generally New England BioLabs, Beverly, Mass.). DNA fragments used for cloning and hybridization were purified from 1% agarose gels using a Geneclean II kit (Bio 101, Vista City, Calif.). Subtractive DNA libraries were made using a PCR-Select bacterial genome subtraction kit (Clontech) (1), using genomic DNAs from strains recovered from gastric cancer patients in one pool and DNAs from strains from gastritis-only patients in a second pool. Southern blotting and hybridization were performed using Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. DNA was labeled using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Amersham).

Specific PCR was carried out in 25-μl volumes, containing 5 to 10 ng of DNA, 1 U of Taq polymerase (Promega, Madison, Wis.), or Expand High Fidelity Taq-Pwo polymerase mixture (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.), 5 pmol of each primer (Table 1), and 0.25 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, in a standard buffer for 30 cycles with the following cycling parameters: denaturation at 94°C for 30 s; annealing as appropriate for the primer sequence (generally 55°C) for 30 s; and DNA synthesis at 72°C, as needed (1 min/kb). PCR primers used in these experiments are listed in Table 1. Unless otherwise specified, PCR products were cloned into EcoRV-cleaved pBluescript plasmid DNA to which dTTP had been added, as recommended (17). DNA sequencing was carried out using a Big Dye Terminator DNA sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer) and ABI automated sequencers. DNA sequence editing and analysis were performed with programs in the Wisconsin Package (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.), and data in H. pylori genome sequence databases (2, 27), along with BLAST and pfam (version 5.3) homology search programs (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/blast.cgi; http://pfam.wustl.edu/hmmsearch.shtml).

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Sequence | Location or comments |

|---|---|---|

| Primers specific for JHP1409 (ORF in strain J99) | ||

| R5 | 5′-TAGAAGTGTGCCGTTATGG | Left of IS607 in CPY0041 (clone 2a) |

| F7 | 5′-GGATTTGTGGGTTATTAACAC | Right of IS607 in CPY0041 (clone 2a) |

| Primers specific for IS607 | ||

| Pointing toward left end | ||

| F1 | 5′-TAGCGTTATGGATTTTGCCT | 1,188 bp from left end of IS607a |

| F2 | 5′-GCATAGATATTTAAGCCATTAGA | 1,351 bp from left end of IS607a |

| F3 | 5′-ATGCGTGATTGAGATAGCTG | 740 bp from left end of IS607a |

| F4 | 5′-GCTTGACCGATTGATAGCA | 120 bp from left end of IS607a |

| F6 | 5′-TGGCGTATTTGGTTACTTCA | 948 bp from left end of IS607a |

| F8 | 5′-GTTACACCCAAAAGCTTACTC | 141 bp from left end of IS607a |

| F9 | 5′-CACTTCATAGTTAAAGCCAC | 388 bp from left end of IS607a |

| F10 | 5′-CTCTTAATTTAGGATTTTTGTTG | 1,984 bp from left end of IS607a |

| Pointing toward right end | ||

| R1 | 5′-ACTAGGGATTGATATAGGGA | 739 bp from right end of IS607a |

| R2 | 5′-TGATTATTTAAAAATACCTAACTTACC | 919 bp from right end of IS607a |

| R3 | 5′-AGACCTGCTCTAATTGTCAA | 296 bp from right end of IS607a |

| R4 | 5′-TGCTATCAATCGGTCAAGC | 1,926 bp from right end of IS607a |

| R6 | 5′-GCGCTAGATTGTATGGCTCT | 1,386 bp from right end of IS607a |

| R7 | 5′-TCAATGCCTAGAGTGTGGC | 238 bp from right end of IS607a |

| R8 | 5′-CCTAAATTAAGAGAATTTTATAGC | 56 bp from right end of IS607a |

| Universal primers for adapter PCR | ||

| C1 | 5′-GTACATATTGTCGTTAGAACGCG | Adapter-specific primer (TaKaRa) |

| C2 | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGA | Adapter-specific primer (TaKaRa) |

| Primers specific for F factor of E. colib | ||

| 2-4 | 5′-CATTCGTGGCGATAGCCCAC | |

| 3-3 | 5′-CACTGACGGATGCCACCTGC | |

| 3-7 | 5′-TTACCCGGCACAGAGAGGAC | |

| 5-2 | 5′-CAGTGCCGGTACAGTGCGA | |

| 15-1 | 5′-TGGCGGAACTGCGTATCCAC | |

| 15-3 | 5′-GTGAAATGAAGCGCCTGTATG | |

| Primers for mutagenesis | ||

| Sel-SacI | 5′-ACAAAAGCTGtAGCTCCACC | “t” eliminates vector SacI site |

| Mut1 | 5′-AAAGCGATTTT.cTGCGTGATTGAG | Eliminated A in TTTAT (9th codon of overlap) |

| Mut2 | 5′-GATAGCTGACAT.cGTTAGTTATTAC | Eliminated T in CATTG (1st codon of overlap) |

| Vector (pBS), flanking cloning site | ||

| M13F | 5′-TGTAAAACGACGGCCAG | |

| M13R | 5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGACC |

Distances determined from 5′ end of primer.

Individual primers specific for F factor sequences were generated to complete determination of sites of IS607 insertion, partially identified by adapter PCR as detailed in Materials and Methods. Primer names designate insertions that are listed in Fig. 3.

Sites of 1-bp deletion used to generate −1 frameshift.

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

CPY0041, the H. pylori strain in which IS607 was found, was from a Japanese patient with gastritis. The pools of Japanese H. pylori strains used in subtractive hybridization (see above) consisted of CPY0041, CPY2362, CPY6021, HU29, HU38, HU56, and HU78 from gastritis patients and CPY6081, CPY6271, HU54, HU71, HU118, HU157, and HU176 from cancer patients. HU strains (kindly provided by M. Asaka) were from Hokkaido, and CPY strains (Shirai and Nakazawa collection) were from Yamaguchi prefecture. Other strains screened for the presence or absence of IS607 were from the Berg laboratory collection, most of which has been described elsewhere (5, 9, 15, 19).

The E. coli K-12 strains used in this study were DH5α, the routine host for recombinant DNA plasmid cloning and DNA preparation; DB1683, a Strs strain that contains pOX38, a deletion derivative of the F (fertility) factor that lacks known IS elements, and MC4100, an F− Strr strain, used as donor and recipient strains in bacterial conjugation (4); and BMH71-18 mutS, used for transformation after generating point mutations in cloned DNAs (Clontech). Plasmids pBluescript SK+/− (pBS; Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and pUC18 (Stratagene) were used as vectors for routine cloning procedures. A chloramphenicol resistance gene (cam) was inserted into IS607, to allow its transposition to be selected (as in reference 14).

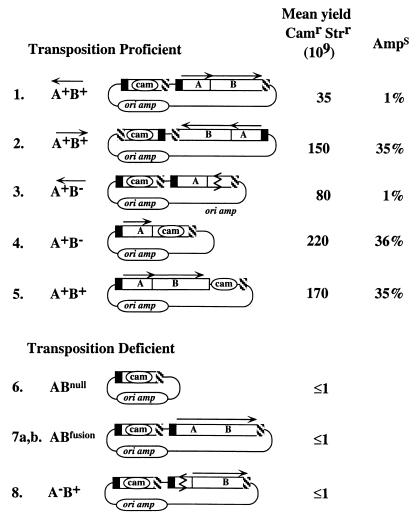

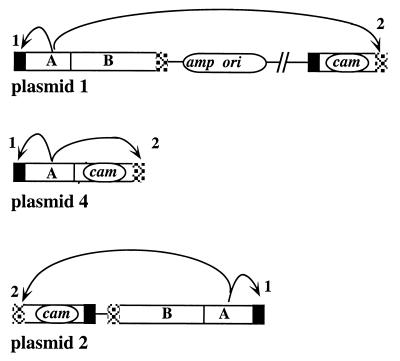

The recombinant plasmids used to detect IS607 transposition in E. coli, diagrammed in Fig. 2, were constructed in pBS or pUC18 vectors, using PCR and restriction endonuclease cleavage-based methods. PCR amplification used in these plasmid constructions was carried out using the Expand High Fidelity Taq-Pwo DNA polymerase mixture (Boehringer Mannheim), in place of standard Taq DNA polymerase, to minimize the risk of unwanted mutation during PCR.

FIG. 2.

Diagram of plasmids containing IS607 and related elements generated for this study, as detailed in Materials and Methods. A and B refer to orfA and orfB, respectively. The left (orfA) and right (orfB) ends of these elements are represented by the filled and patterned boxes, respectively. The average frequencies of Camr Strr exconjugants and yield of Amps isolates among Camr Strr exconjugants listed were based on a number of conjugation assays, typically using several different constructs of the depicted plasmids, to avoid being misled by mutation during PCR or gene cloning, as follows: plasmid 1, 24 assays, two different constructs; plasmid 2, 6 assays, three different constructs; plasmid 3, 24 assays, five different constructs; plasmid 4, 15 assays, five different constructs; plasmid 5, 10 assays, five different constructs; plasmid 6, 8 assays, one construct; plasmids 7a and 7b, 12 assays, four different constructs (two constructs with each frameshift [7a,b]); plasmid 8, 20 assays, six different constructs.

To begin making these plasmids, the complete IS607 element was PCR amplified from a cloned restriction fragment of H. pylori genomic DNA that was derived originally from strain CPY0041 (clone 2a; see below) using primers F7 and R5, specific to sequences flanking the site of IS607 insertion (Table 1). This PCR-amplified DNA was cloned into SmaI-cleaved pBS to generate pBS:IS607wt.

Plasmids 6 and 1.

IS607 containing the cam gene in place of most of orfA and orfB was made by linearizing pBS:IS607wt DNA by PCR with outward-facing IS607 primers R3 and F4 and then ligating the cam cassette (generated by SmaI-EcoRV digestion of plasmid pBSC103) between the remnants of IS607 (120 bp of left [orfA] and 296 bp of right [orfB] ends) to generate plasmid 6. A segment containing this IS607cam element was PCR amplified with primers F7 and R5 and ligated into the EcoRV site in the pBS polylinker of pBS:IS607wt to generate plasmid 1 (Fig. 2).

Plasmid 2.

A plasmid with IS607wt and IS607cam components reversed, relative to their positions in plasmid 1, was made in pUC18 (because of its convenient distribution of restriction sites). First the IS607 element was excised from plasmid pBS:IS607wt with BamHI and EcoRI and then recloned between EcoRI and BamHI sites of pUC18. The IS607cam-containing PCR fragment (used in construction of plasmid 6, above) was then cloned into the SalI site of pUC18:IS607wt after filling in overhanging ends with Klenow DNA polymerase.

Plasmid 3.

A derivative of plasmid 1 containing a 340-bp deletion in the 1,257-bp IS607 orfB gene was constructed by PCR with outward-facing primers R1 and F6 and intramolecular ligation.

Plasmid 4.

A plasmid containing just one IS607 element, in which a 784-bp deletion in orfB was marked with cam, was generated from pBS:IS607wt DNA by PCR with outward-facing primers R3 and F6 and ligation of the product with the cam cassette.

Plasmid 5.

A plasmid with an IS607 derivative containing cam inserted just after the 3′ end of orfB was generated from pBS:IS607wt DNA by PCR with outward-facing primers F10 and R8 and ligation of the product with the cam cassette. These primers contain a 13-bp overlap at their 5′ ends to ensure that insertion of the cam cassette could leave intact both orfB and the segment containing inverted repeats (possible sites of transposition protein action) in IS607's termini).

Plasmids 7a and 7b.

Two plasmids whose IS607 elements contained in-frame fusions of orfA and orfB were generated from plasmid 1 by creating −1 frameshift mutations in the first and last codons of the nine-codon orfA-orfB overlap (constructs 7a and 7b, respectively [see Fig. 4]), using a Transformer site-directed mutagenesis kit (Clontech) as recommended by the manufacturer. In brief, (i) DNA of the target plasmid was denatured; (ii) two mutant primers were added, one to generate the desired frameshift mutation and one to inactivate a restriction (SacI) site (which would allow later selection of mutant DNAs); (iii) DNA synthesis was carried out with T4 DNA polymerase, and products were ligated with T4 DNA ligase; (iv) DNAs likely to have mutant strands were selected by SacI digestion; (v) surviving circular plasmid DNA was transformed into mutS (mismatch correction-deficient) E. coli; (vi) recovered plasmid DNA was digested again with SacI, and surviving plasmid DNAs were recovered by transformation in E. coli DH5α; and (vii) mutant clones were verified by DNA sequencing. Plasmid 7a was constructed using primer Mut1 (ninth codon of overlap), and plasmid 7b was constructed using primer Mut2 (first codon of overlap), coupled with primer Sel-SacI (SacI site GAGCTC changed to tAGCTC) in each case (see Fig. 4).

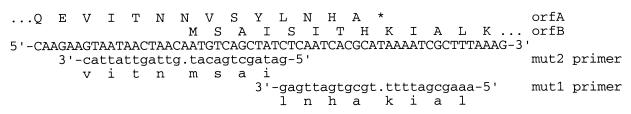

FIG. 4.

Nine-codon overlap between IS607 orfA and orfB, and strategies that generate fusions. Line 1, carboxy-terminal amino acid sequence of OrfA protein; line 2, amino-terminal amino acid sequence of OrfB protein; line 3, corresponding DNA sequence (sense strand); line 4, mutagenic primer Mut2 (−1 frameshift in first codon of overlap; antisense DNA strand); line 5, fusion protein sequence resulting from −1 frameshift in first codon of overlap; line 6, mutagenic primer Mut1 (−1 frameshift in ninth codon of overlap; antisense DNA strand); line 7, fusion protein sequence resulting from −1 frameshift in ninth codon of overlap.

Plasmid 8.

A derivative of plasmid 1 containing a 500-bp deletion in the 651-bp orfA gene was constructed by PCR with outward facing primers R6 and F8 and self-ligation.

IS607 transposition in E. coli.

Strain DB1683 was transformed with plasmids 1 through 8 (Fig. 2), as appropriate. Transposition of the marked IS607 element (IS607cam) to an F factor was then selected in a mating-out assay. Single transformant colonies were grown overnight with aeration, diluted 100-fold into 4 ml of L broth plus 0.5% glucose in a petri dish, incubated for another 2 to 3 h at 37°C without shaking, then mixed with 4 ml of an exponentially growing MC4100 F− recipient culture at equal cell density in a total volume of 8 ml, and incubated for 3 h at 37°C without shaking. One milliliter of mating mix was concentrated by centrifugation, and the pellet was spread on L agar containing Str and Cam. This selected for IS607cam transposition to pOX38 and then transfer of pOX38::IS607cam to MC4100 (4, 14). The values reported here are Camr Strr exconjugants per initial donor cell in matings that were carried out under the same conditions in each trial. The F-factor plasmid was not marked with a separate drug resistance determinant, and thus the absolute efficiency of F-factor transfer was not determined. The selected Camr Strr exconjugants were scored for the presence or absence of the plasmid vector (Amps or Ampr phenotype, respectively).

Definition of sites of IS607 insertion in pOX38.

An adapter PCR method, the TaKaRa PCR in vitro single-site amplification and cloning kit (PanVera, Madison, Wis.), was used to identify sites of IS607cam insertion in pOX38. Total genomic DNAs of Camr Strr exconjugants were digested with restriction enzyme Sau3A and ligated with adapter cassettes supplied with the kit. PCR was carried out with cassette primer C1 and the IS607 right-end-specific primer R3 (primer sequences in Table 1). A second nested PCR was then carried out using cassette primer C2 and a second IS607 right-end-specific primer, R7. Gel-purified fragments were sequenced directly or after cloning into an EcoRV-cleaved pBS vector. Once each right-end junction was determined, the sequence was used to design an F-factor-specific primer that should allow amplification of the IS607-F DNA left junction when used in combination with outward-facing IS607 primer F4. The resultant amplification products were also sequenced directly without cloning. In the case of transpositions from plasmid construct 4 (Fig. 2), adapter PCR was also carried out using left-end-specific primers F4 and then F8, and these products were sequenced directly, without ordering additional F-factor-specific primers.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The IS607 element depicted in Fig. 1 corresponds to nucleotide 238 through 2274 of the 2,544-nucleotide sequence in GenBank accession no. AF189015.

RESULTS

Discovery of IS607.

Two subtractive hybridizations were carried out using genomic DNAs from two pools of H. pylori strains, one from gastric cancer patients and one from patients with more benign infections, with selection for sequences that might be unique to one or the other pool. Although no sequences implicated in virulence were recovered, one cloned DNA (F10), a 273-bp segment from pooled of DNAs from gastritis strains, exhibited protein-level homology to a family of putative transposase genes in diverse bacterial species that includes orfB of the 2-kb IS605 element (Fig. 1). This observation suggested that this clone might be from a previously unknown IS element, provisionally designated IS607. PCR tests using primers based on the sequence of this clone (primers F2 and R2 [Table 1]) and hybridization tests using F10 DNA as a probe showed that this sequence was present in about one-fifth of H. pylori strains from various parts of the world (Table 2). Such distributions are quite typical of IS elements in H. pylori and in other bacterial species (14, 16, 23).

TABLE 2.

Distribution of IS607 in different H. pylori populations

| Region | No. of strains | IS607-positive strains

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | ||

| South America | 141 | 31 | 22 |

| Guatemala | 27 | 10 | 37 |

| Peru (native) | 77 | 12 | 16 |

| Peru (Japanese) | 37 | 9 | 24 |

| United Statesa | 120 | 34 | 28 |

| Africa | 49 | 13 | 27 |

| S. Africa | 42 | 11 | 26 |

| Gambia | 7 | 2 | 29 |

| Europe | 96 | 13 | 14 |

| Spain | 68 | 12 | 18 |

| Lithuania | 12 | 1 | 8 |

| Sweden | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| Asia | 262 | 38 | 15 |

| Hong Kong | 50 | 9 | 18 |

| Japan | 136 | 19 | 14 |

| India | 76 | 10 | 13 |

The 34 IS607-positive U.S. strains consist of 28 (of 88) strains from 5 states within the contiguous 48 states (15) and 6 (of 32) strains from Alaska Natives.

Sequence characterization of IS607.

Southern blotting was used in a first characterization of IS607 in the genome of CPY0041, the strain from which clone F10 had been isolated. Seven F10-hybridizing bands, each more than 2 kb long, were found in SspI, StyI, EcoRI, and BglII digests of this DNA (data not shown), indicating that CPY0041 contains about seven copies of IS607. Just one F10-hybridizing band, 0.6 kb long, was found in HindIII digests of CPY0041 genomic DNA, indicating at least two internal HindIII sites. SspI digest fragments containing F10-hybridizing sequences were cloned into the SmaI site of the pBS plasmid after size fractionation (2.9- to 5.2-kb size range), and three different cloned DNA fragments (2.9, 3.1, and 4.0 kb, in clones 8-3, 22-4, and 2a, respectively) were identified by PCR using vector-specific primers (M13F and M13R).

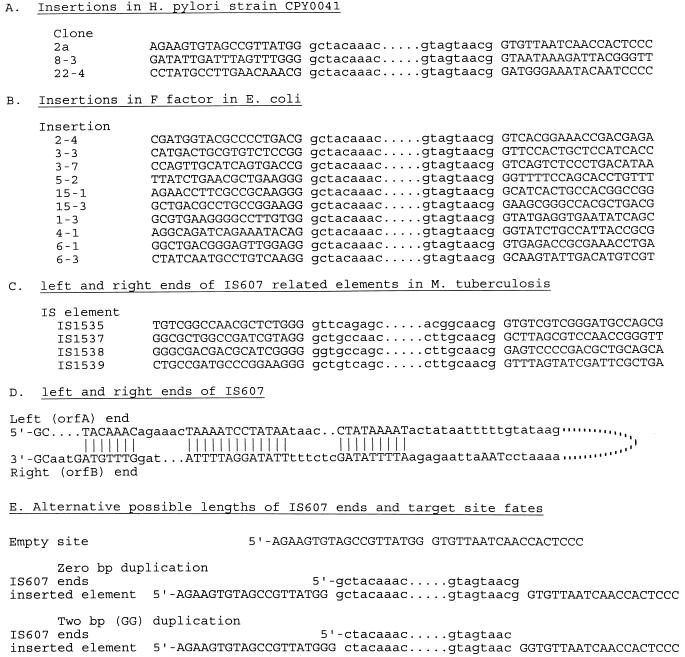

The portion of one clone (2a) likely to contain a complete IS607 element was sequenced in its entirety. IS607 was identified as a 2,027-bp DNA segment (Fig. 1A) that is not present in either fully sequenced H. pylori genome (J99 or 26695 [2, 27]). It was inserted into a DNA methylase gene that is found intact in strain J99 (jhp1409). Sequences from the two other clones, determined using outward-facing primers, revealed the same IS607 element inserted into other genes that were also known from the sequenced H. pylori genomes; one is a putative transcription regulator, and the other is a gene of unknown function (Fig. 3A, legend). The terminal regions contained three short inverted repeats (8, 13, and 9 bp) within ∼45 bp of each IS607 end (Fig. 3D); these may be candidates for sites of transposition protein action. The IS607-target junction sequences were equally compatible with two alternative views of IS607 terminal structure and rules for insertion: (i) a 2-bp terminal inverted repeat (5′-GC and CG-3′) (Fig. 3A), insertion between adjacent G residues, and no target sequence duplication; or (ii) IS607 ends that are 1 bp shorter, with insertion next to two GG residues, and 2-bp target sequence duplication.

FIG. 3.

Terminal sequences of IS607 and related elements and sites of insertion. (A) Termini and sites of IS607 insertion in H. pylori strain CPY0041. IS607 ends are in lowercase letters, and flanking sequences are in capital letters. This presentation assumes 0-bp target sequence duplication (see panel E). Insertion sites are defined relative to corresponding genes in fully sequenced genomes of strains 26695 (HP numbers [27]) and J99 (jhp numbers [2]). The following insertions were identified by sequencing in H. pylori strain CPY0041: clone 2a, insertion at position 3158/9 bp in a gene designated jhp1409, a type II DNA modification enzyme (methyltransferase) in strain J99; clone 22-4, insertion at 64/5 bp in a gene designated jhp1207 in J99 and HP1287 in 26695, a putative transcription regulator; and clone 8-3, insertion at position 2509/10 bp in a gene designated jhp1044 in J99, which has 70.8% homology with the shorter HP1116 gene of 26695 (1,154 codons versus 957 codons), which are each considered hypothetical function-unknown genes. (B) Termini and sites of IS607cam insertions in the F factor. The transposition donor plasmids (Fig. 2) from which the transposed IS607cam elements derived and nucleotide positions of insertions are as follows. Three insertions were derived from plasmid 1: 2-4, position 62046/5 bp, accession no. AF074613; 3-3, position 28627/6 bp, accession no. U01159; and 3-7, position 5996/5 bp, accession no. U01159. Three insertions were derived from plasmid 3: 5-2, position 12552/1 bp, accession no. U01159; 15-1, position 11046/5 bp, accession no. AF074613; and 15-3, position 65685/6 bp, accession no. AF074613. Four insertions were derived from plasmid 4: 1-3, position 633/4 bp, accession no. AF106329; 4-1, position 5941/2 bp, accession no. U01159; 6-1, position 3771/70 bp, accession no. AF106329; and 6-3, position 57885/6 bp, accession no. AF074613. (C) Insertions of four IS607-related elements in the genome of M. tuberculosis, to illustrate a possible insertion preference for GG dinucleotide targets (taken from http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/M_tuberculosis/). (D) Left and right ends of IS607 (same strand), aligned to highlight inverted repeat motifs (capital letters). (E) Alternative models for IS607 termini and target site fates: (i) 0-bp target duplication model implies that ends of IS607 are 5′-gcta… and …aacg-3′; or (ii) 2-bp target duplication model implies that IS607 is 1 bp shorter at each end. The sequence used in this illustration is that of insertion 2a in panel A.

The complete IS607 element contained two ORFs of 218 and 420 codons that are transcribed and translated in the same direction (Fig. 1A), that overlap by nine codons, and that are related to genes found in a diverse and extended family of IS elements, some of which are diagrammed in Fig. 1A. In particular, IS607 orfB is a protein-level homolog of the orfB gene of IS605, another chimeric element of H. pylori, whereas the orfA genes of IS607 and IS605 are not related to one another. In contrast, homologs of IS607 orfA and orfB are each in IS1535 and related elements of M. tuberculosis, where they had been annotated as resolvase and transposase, respectively (11). Homologs of IS607 orfA were also found in putative IS elements from Methanococcus jannaschii and other archaeal and eubacterial species, but in many cases the adjacent gene, although possibly encoding a transposase, seemed not to be related to orfB of IS607. The 5′ end of IS607 orfA was related to corresponding regions from the merR family of bacterial regulatory genes, not to the 5′ end of the putative resolvase gene of IS1535 (Fig. 1B and C), suggesting that IS607 orfA might stem from an ancient gene fusion event. It is also noteworthy that the matches between the putative resolvase of IS1535 and proteins with empirically demonstrated site-specific recombinase activity are weak and short, since mutational tests described below suggest that IS607 OrfA protein is actually a transposase.

Additional tests indicated that the IS607 orfA-orfB structure found in strain CPY0041, including the overlap of ORFs, was typical of this element in diverse H. pylori clinical isolates. First, each of 50 strains that yielded PCR amplification products with orfB-specific primers (F2 and R2) also yielded products with orfA-specific primers (F9 and R4). Second, PCR tests with primers in orfA and orfB (F1 and R4) yielded the expected 1.1-kb product in each of the 50 cases tested (data not shown), thus indicating conservation of the orientation and spacing between these two ORFs. Third, sequence analysis of about 500 bp of IS607 overlap region DNA from four strains, each from a different region (Hong Kong, United States, Guatemala, and Gambia), using primer F6 (Table 1) revealed a close (96 to 99%) DNA match with that of the fully sequenced IS607 element and DNA sequence identity among all strains in the nine-codon overlap of the two ORFs. Such overlaps are common in IS607-related elements in the public database.

IS607 transposition in E. coli.

Transposition of IS607 derivatives that had been marked genetically with a cam gene was detected in E. coli using a mating-out assay, in which the element transposes from a pBS plasmid vector to the F factor pOX38. Exconjugants carrying transposition products were selected by conjugation with the E. coli Strr recipient strain MC4100 and plating on medium containing Cam and Str. The natural and various engineered IS607 elements used in these experiments are diagrammed in Fig. 2. To help guard against false leads caused by inadvertent mutation, each assay was carried out multiple times, with several independent plasmid constructs (Fig. 2, legend).

The first donor plasmid constructed (plasmid 1 in Fig. 2) contained (i) IS607 with cam in place of orfA and orfB and (ii) an adjacent intact IS607 element to supply transposase. Camr Strr (putative transposition product)-containing exconjugants were obtained at a low frequency, on average ∼3.5 × 10−8 per starting donor cell. This was considered indicative of transposition (albeit inefficient) because the yield of Camr Strr exconjugants starting with a related plasmid containing only the marked IS607 element (plasmid 6; no intact orfA or orfB genes) was reproducibly ≤10−9 per donor cell. However, only about 1% of the Camr Strr exconjugants obtained with plasmid 1 were Amps, the phenotype expected of simple transposition of one or both IS607 elements away from vector sequences. The other ∼99% were Ampr, and 8 of 11 screened by DNA extraction and gel electrophoresis contained free donor plasmid; the other three also contained vector sequences, but perhaps integrated into the F factor.

Probing of Southern blots of EcoRI-digested genomic DNAs from seven of the Camr Strr exconjugants that were Amps indicated that five of them contained simple insertions of just the IS607cam segment. The other two seemed to contain insertions of much or all of the plasmid, but apparently coupled with inactivation of the amp gene (since they were Amps); they may have resulted from illegitimate recombination (which would not involve IS607) and were not studied further.

The ends of IS607 and sites of insertion were defined further as described in Materials and Methods, using three different insertions of the IS607cam element into the F-factor target. The results obtained were in accord with those from studies of preexisting IS607 insertions in H. pylori (above): the sequences of termini of IS607 that had transposed in E. coli were identical to those found in H. pylori; and the IS607 elements were inserted between (or next to) adjacent G nucleotides without deletion, and perhaps without duplication (or with GG duplication; see above), of target DNAs in each case (Fig. 3B). This outcome established that IS607 can indeed transpose as a discrete unit in E. coli.

Mutational analysis of IS607 gene function.

The arrangement of two ORFs, one overlapping the other, in IS607 and some of its relatives was reminiscent of several unrelated mobile elements including IS1, in which the functional transposase consists of a protein generated by translational slippage between two overlapping ORFs (insA and insB) (10, 24). The possibility that the active IS607 transposase also consisted of a single tethered OrfA-OrfB protein was tested by generating two in-frame gene fusions, one at each end of the nine-codon overlap (Fig. 4), to generate plasmids 7a and 7b. Each mutant was found to be inactive in transposition (≤10−9). This suggested that OrfA and/or OrfB proteins could be active in IS607 transposition only if they were separate, not tethered to one another.

The possibility that IS607 orfA encodes a resolvase, not a transposase, was suggested by consideration of the annotations of several of its homologs in the genomes of various other bacterial species, even though the matches of these homologs to proven resolvases are weak and IS607 OrfA and IS1535 resolvase differ markedly in their amino-terminal domains (Fig. 1B and C). If, nevertheless, OrfA were to function as a resolvase for IS607 transposition, one would expect either that inactivation of orfA would not affect IS607 transposition efficiency or (if the putative resolvase also functioned as repressor, as in Tn3 [26]) that orfA inactivation might increase the transposition frequency. Accordingly, an IS607 element with a 500-bp deletion in orfA (plasmid 8) was constructed and used in mating-out transposition assays. The yield of Camr Strr exconjugants was ≤10−9 in parallel matings with each of six separate plasmid constructs that contained this orfA deletion. This outcome indicated that orfA is needed for IS607 transposition in E. coli—that is, that OrfA protein may be a transposase.

The role of the IS607 OrfB protein was investigated similarly, using plasmids containing a 340-bp deletion in orfB (plasmid 3). The yield of Camr Strr exconjugants with this plasmid was about 8 × 10−8, which is a fewfold higher than the yield with the related orfB+ plasmid (plasmid 1). Thus, orfB, whose homologs are present in the two other known IS elements of H. pylori (IS605 and IS606), is not needed for IS607 transposition. Only about 1% of the Camr Strr exconjugants generated with the orfB-defective element were Amps, as had been seen with orfB+ elements. PCR and Southern blots of EcoRI-digested genomic DNAs from 20 selected Camr Strr but Amps exconjugants from five different matings indicated that 15 of these 20 contained simple insertions of just the IS607cam element (Fig. 5); four contained an insertion of a segment consisting of IS607 and IS607cam, but not vector sequences (Fig. 5); and one contained most of the plasmid, although it was Amps. The sites of insertion in three of the exconjugants that contained just a single IS607cam element were analyzed by adapter PCR and sequencing. The results revealed insertion of the engineered IS607 element as a discrete unit, apparently between GG pairs (or next to such pairs; see above), as with orfB+ elements (Fig. 3). More generally, they further indicated that IS607 transposition in E. coli is orfB independent.

FIG. 5.

Structures of products of transposition, with diagram of inferred sequential action of OrfA protein on site nearest its site of synthesis, followed by action on a second appropriate site. Donor plasmid numbers (1, 2, and 4) refer to designations used in Fig. 2.

The apparent orfB independence of IS607 transposition was investigated further with two additional plasmids (4 and 5). Each contained just one marked IS607 element, with the cam gene either replacing 784 bp of orfB (plasmid 4) or inserted just downstream of orfB (plasmid 5). The Camr Strr exconjugant yields with the orfB mutant plasmid (plasmid 4) was about 2 × 10−7 (some fivefold higher than with compound two-element constructs [plasmids 1 and 3]), and 36% of products were Amps. Four transposition products were analyzed as above and found to contain insertions of the marked IS607 element between GG pairs in target DNAs (Fig. 3B). Camr Strr exconjugants were also selected starting with plasmid 5, whose IS607 element was orfB+ (cam inserted in noncoding sequence just downstream of orfB). Exconjugants were obtained at a frequency of about 1.7 × 10−7. About 35% of transposition products from this plasmid were also Amps.

The importance of orfA, but not orfB, for IS607 transposition, and the higher yield of simple (Amps) products of IS607 transposition from plasmids with single IS607cam elements (4 and 5), compared with the lower yield with composite two element plasmids (1 and 3), suggested a model in which transposase might act preferentially on sites closest to the gene encoding it (as in references 7 and 21), and then only secondarily on more distant sites, as diagrammed in Fig. 5. This model predicted that many of the transposition products generated from plasmids in which the two IS607 components were reversed relative to one another (compare plasmid 2 with plasmid 1 in Fig. 2) would be Amps (Fig. 5). Plasmid 2 was generated to test this prediction, and Camr Strr exconjugants were obtained using it at a frequency of about 1.5 × 10−7 (some fivefold higher than with the related plasmid 1). In agreement with predictions (Fig. 5), 35% of Camr Strr exconjugants were Amps, and each of the 18 such Amps exconjugants tested contained intact IS607 along with the selected IS607cam element.

DISCUSSION

The IS607 element described here was found in one-fifth of H. pylori strains worldwide. It contains two ORFs that overlap by nine codons and that may be of different phylogenetic origins, based on the distributions of their homologs in different bacterial species (Fig. 1A). Our hybridization and PCR tests and limited sequence analyses indicated that any H. pylori strain containing one IS607 ORF generally contained the other in the same relative position and orientation as that depicted in Fig. 1A. These results are reminiscent of the outcome of studies of the only other known transposable elements of H. pylori, IS605 and IS606, which are also chimeric (two-gene) elements (14). Of particular interest, orfB of IS607 is a protein-level homolog of orfB genes of IS605 and IS606, whereas orfA of IS607 is not related to the orfA genes of these other H. pylori IS elements.

The constant association of orfA and orfB in IS607-related sequences in diverse H. pylori strains, like the equivalent associations of cognate orfA and orfB sequences in IS605 and IS606, had encouraged the idea that the proteins encoded by these adjacent genes might each be essential for transposition. One precedent for this idea was provided by Tn7: two of the proteins it encodes (TnsA and TnsB) act together in a complex to mediate Tn7 transposition (8). Our mutational tests showed, however, that IS607 transposition in E. coli depended only on orfA, not on orfB. This orfB independence is not attributable to complementation, however, since no orfB-related sequences are found in the genome of E. coli K12 (http://www.genetics.wisc.edu:80/), a subline of which was used here (databases listings of IS607 orfB homologs in E. coli refer to plasmids in clinical isolates, not to the E. coli K12 genome).

IS607 OrfA exhibits considerable homology to members of the MerR bacterial regulatory protein family in its first 50 amino acids and then homology to a protein of IS1535 of M. tuberculosis and related putative IS elements in other bacterial species. These had been annotated variously as probable resolvase, based on weak short patch match to proteins known empirically to cause site-specific recombination (IS1535; accession no. A70583), or hypothetical function unknown, perhaps because of weakness of the homologies that were seen (MJ0014 of M. jannaschii; accession no. F64301). There were no other indications from protein database searches as to what function IS607 OrfA protein might possess, beyond these short matches with recombinase and MerR family motifs. Thus, OrfA protein may represent a new type of transposase, quite distinct from any studied heretofore.

All insertions of IS607 that were scored were associated with adjacent G nucleotides. It is not yet clear whether insertion occurs between them, without target sequence duplication (the case if IS607 termini consist of 5′GC and CG-3′) or next two them, duplicating 2 bp of target sequence (if IS607 is 1 bp shorter at each end) (Fig. 3E). Indications that IS605 inserts without duplication (14) might be considered to support the 0-bp option. However, the homologies between IS605 and IS607 are in orfB, which is not needed for IS607 transposition, at least in E. coli. It is also noteworthy that IS607 was quite different from IS605 in its detailed insertion specificity, in that IS605 inserted just downstream of TTTAA and possibly also TTTAAC (adjacent to its left end), without obvious preference for target sequences adjacent to its right end (14). Interesting in this context, the IS607-related elements in M. tuberculosis (IS1535 and siblings) also seemed to be inserted between or next to adjacent G residues (Fig. 3C). If IS605 is like IS607 in depending only on its cognate OrfA protein for transposition in E. coli, the apparent differences in target choice by these two elements may reflect differences between their OrfA proteins in amino acid sequence and in DNA recognition.

The significance of the 2-bp (or possibly just 1-bp) terminal inverted repeat of IS607 elements characterized to date is not known, since each is from the same H. pylori strain. Based on findings that the leftmost 8 bp of IS605-related elements are quite variable (15), it is possible that this miniscule repeat is fortuitous. Given the requirement for just one IS607-encoded protein for movement in E. coli, it is appealing to imagine that the several short subterminal inverted repeats (within the first 45 bp of each IS607 end; Fig. 3D) serve as sites for transposition protein action.

The relative positions of the orfAB-defective IS607cam element and IS607wt that supplied transposase strongly affected the distribution of types of Camr transposition products obtained (Fig. 5): simple transposition products, lacking the vector plasmid sequence, were much less common with one donor plasmid configuration than the other (1% versus ∼35% using plasmid 1 versus plasmid 2, respectively [Fig. 2]). Perhaps these patterns reflect a preferential action of transposase on sequences nearest its site of synthesis, and then only secondarily on more distant sites (Fig. 5). Such highly localized transposase action is rather common in bacterial IS elements (16, 20, 28) and might even have been selected if they evolved as selfish DNAs. Why so many transposition products contained the entire vector sequence, however, needs further study. One possible model envisions a transposition mechanism that is frequently but not always replicative (see references 7 and 18).

If orfB is not needed for IS607 transposition, at least in E. coli, why are orfA-orfB combinations so widespread in microbes? One possibility invokes a role in modulation (down regulation) of transposition activity, an inference in accord with the apparently slightly higher yield of transposition products with orfB-deficient elements. Alternatively, orfB might contribute to bacterial fitness directly, independent of transposition, as is the case with the IS50 component of Tn5 (13). In a third model, each gene might be needed for transposition in a different set of bacterial species. In one version, the use of OrfA or OrfB as transposase would depend on their interactions with particular host factors. Studies with Tn7 illustrate the exploitation of quite improbable host proteins as transposition cofactors (ribosomal protein L29 and acyl carrier protein in the case of Tn7 [25]). In this scenario, the IS607 host range would be affected by the species distribution of host factors with which OrfA or OrfB could interact. Having two different transposition systems, each active in a different constellation of bacterial species, would be adaptive and do much to explain the current broad distribution of IS607 and related elements among diverse eubacterial and archaebacterial lineages.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Masahiro Asaka (Hokkaido University Medical School) for providing some of the H. pylori strains used in subtractive hybridization, many other collaborators for providing H. pylori strains used to assess the distribution of IS607 worldwide, and Tom Blackwell (Institute of Biomedical Computing, Washington University), Luda Diatchenko (Clontech), and an anonymous reviewer for stimulating and constructive discussions and suggestions.

This research was supported in part by grants AI38166 and DK53727 from the Public Health Service to D.E.B. and P30 DK52574 to Washington University and by grants-in-aid 11470133 and 11877242 to M.S. from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports of Japan.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

It has just been reported that the gipA gene, a homolog of IS607 orfB that is carried by a prophage of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, is needed for Salmonella growth or survival in Peyer's patches (T. L. Stanley, C. D. Ellermeier, and J. M. Slauch, J. Bacteriol. 182:4406–4413, 2000). This is in accord with our finding that IS607 orfB is not needed for transposition in E. coli and suggests the interesting possibility that orfB and its homologs in related IS elements, although present in only a subset of strains, also affect H. pylori-human host interactions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akopyants N S, Fradkov A, Diatchenko L, Siebert P D, Lukyanov S, Sverdlov E D, Berg D E. PCR-based subtractive hybridization and differences in gene content among strains of Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13108–13113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alm R A, Ling L S, Moir D T, King B L, Brown E D, Doig P C, Smith D R, Noonan B, Guild B C, deJonge B L, Carmel G, Tummino P J, Caruso A, Uria-Nickelsen M, Mills D M, Ives C, Gibson R, Merberg D, Mills S D, Jiang Q, Taylor D E, Vovis G F, Trust T J. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1999;397:176–180. doi: 10.1038/16495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K A, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology, suppl. 27 CPMB. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing and Wiley Interscience; 1994. p. 2.4.1. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg D E. Structural requirement for IS50-mediated gene transposition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;79:792–796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.3.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg D E, Gilman R H, Lelwala-Guruge J, Srivastava K, Valdez Y, Watanabe J, Miyagi J, Akopyants N S, Ramirez-Ramos A, Yoshiwara T H, Recavarren S, Leon-Barua R. Helicobacter pyloripopulations in individual Peruvian patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:996–1002. doi: 10.1086/516081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berg D E, Howe M M, editors. Mobile DNA. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biel S W, Berg D E. Mechanism of IS1 transposition in E. coli: choice between simple insertion and cointegration. Genetics. 1984;108:319–330. doi: 10.1093/genetics/108.2.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biery M C, Lopata M, Craig N L. A minimal system for Tn7 transposition: the transposon-encoded proteins TnsA and TnsB can execute DNA breakage and joining reactions that generate circularized Tn7species. J Mol Biol. 2000;297:25–37. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalkauskas H, Kersulyte D, Cepuliene I, Urbonas V, Ruzeviciene D, Barakauskiene A, Raudonikiene A, Berg D E. Genotypes of Helicobacter pyloriin Lithuanian families. Helicobacter. 1998;3:296–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandler M, Fayet O. Translational frameshifting in the control of transposition in bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:497–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry III C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver S, Osborne J, Quail M A, Rajandream M A, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton S, Squares S, Squares R, Sulston J E, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell B G. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosisfrom the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Craig N L. Target site selection in transposition. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:437–474. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartl D L, Dykhuizen D E, Miller R D, Green L, de Framond J. Transposable element IS50 improves growth rate of E. colicells without transposition. Cell. 1983;35:503–510. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kersulyte D, Akopyants N S, Clifton S W, Roe B A, Berg D E. Novel sequence organization and insertion specificity of IS605 and IS606: chimaeric transposable elements of Helicobacter pylori. Gene. 1998;223:175–186. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kersulyte D, Mukhopadhyay A K, Velapatino B, Su W W, Pan Z J, Garcia C, Hernandez V, Valdez Y, Mistry R S, Gilman R H, Yuan Y, Gao H, Alarcon T, Lopez-Brea M, Balakrish Nair G, Chowdhury A, Datta S, Shirai M, Nakazawa T, Ally R, Segal I, Wong B C, Lam S K, Olfat F O, Boren T, Engstrand L, Torres O, Schneider R, Thomas J E, Czinn S, Berg D E. Differences in genotypes of Helicobacter pylorifrom different human populations. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3210–3218. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.11.3210-3218.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahillon J, Chandler M. Insertion sequences. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:725–774. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.725-774.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchuk D, Drumm M, Saulino A, Collins F S. Construction of T vectors, a rapid system for cloning unmodified PCR products. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;19:1154. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.5.1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.May E W, Craig N L. Switching from cut-and-paste to replicative Tn7transposition. Science. 1996;272:401–404. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mukhopadhyay A K, Kersulyte D, Jeong J Y, Datta S, Ito Y, Chowdhury A, Chowdhury S, Santra A, Bhattacharya S K, Azuma T, Nair G B, Berg D E. Distinctiveness of genotypes of Helicobacter pyloriin Calcutta, India. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3219–3227. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.11.3219-3227.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phadnis S H, Sasakawa C, Berg D E. Localization of action of the IS50-encoded transposase protein. Genetics. 1986;112:421–427. doi: 10.1093/genetics/112.3.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reznikoff W S, Bhasin A, Davies D R, Goryshin I Y, Mahnke L A, Naumann T, Rayment I, Steiniger-White M, Twining S S. Tn5: a molecular window on transposition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;266:729–734. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawyer S A, Dykhuizen D E, DuBose R F, Green L, Mutangadura-Mhlanga T, Wolczyk D F, Hartl D L. Distribution and abundance of insertion sequences among natural isolates of Escherichia coli. Genetics. 1987;115:51–63. doi: 10.1093/genetics/115.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sekine Y, Ohtsubo E. Frameshifting is required for production of the transposase encoded by insertion sequence 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:4609–4613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharpe P L, Craig N L. Host proteins can stimulate Tn7transposition: a novel role for the ribosomal protein L29 and the acyl carrier protein. EMBO J. 1998;17:5822–5831. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sherratt D. Tn3 and related transposable elements: site specific recombination and transposition. In: Berg D E, Howe M M, editors. Mobile DNA. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomb J F, White O, Kerlavage A R, Clayton R A, Sutton G G, Fleischmann R D, Ketchum K A, Klenk H P, Gill S, Dougherty B A, Nelson K, Quackenbush J, Zhou L, Kirkness E F, Peterson S, Loftus B, Richardson D, Dodson R, Khalak H G, Glodek A, McKenney K, Fitzegerald L M, Lee N, Adams M D, Hickey E K, Berg D E, Gocayne J D, Utterback T R, Peterson J D, Kelley J M, Cotton M D, Weidman J M, Fujii C, Bowman C, Watthey L, Wallin E, Hayes W S, Borodovsky M, Karp P D, Smith H O, Fraser C M, Venter J C. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinreich M D, Gasch A, Reznikoff W S. Evidence that the cis preference of the Tn5transposase is caused by nonproductive multimerization. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2363–2374. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.19.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]