Key Points

Question

Is osteosarcopenia that is assessed from clinical computed tomography (CT) scans associated with mortality and disability following transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR)?

Findings

In a cohort study of 605 older patients undergoing TAVR, osteosarcopenia was coprevalent with geriatric syndromes, such as frailty, and was associated with a 3-fold increase in 1-year mortality and a 2-fold increase in incident disability. Isolated findings of low muscle mass or low bone density were not associated with mortality or incident disability.

Meaning

Osteosarcopenia, as assessed by CT, is a novel geriatric risk factor that can be opportunistically measured prior to TAVR to inform decision-making and identify patients who may benefit from rehabilitation interventions.

Abstract

Importance

Osteosarcopenia is an emerging geriatric syndrome characterized by age-related deterioration in muscle and bone. Despite the established relevance of frailty and sarcopenia among older adults undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), osteosarcopenia has yet to be investigated in this setting.

Objective

To determine the association between osteosarcopenia and adverse outcomes following TAVR.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This is a post hoc analysis of the Frailty in Aortic Valve Replacement (FRAILTY-AVR) prospective multicenter cohort study and McGill extension that enrolled patients aged 70 years or older undergoing TAVR from 2012 through 2022. FRAILTY-AVR was conducted at 14 centers in Canada, the United States, and France between 2012 and 2016, and patients at the McGill University–affiliated center in Montreal, Québec, Canada, were enrolled on an ongoing basis up to 2022.

Exposure

Osteosarcopenia as measured on computed tomography (CT) scans prior to TAVR.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Clinically indicated CT scans acquired prior to TAVR were analyzed to quantify psoas muscle area (PMA) and vertebral bone density (VBD). Osteosarcopenia was defined as a combination of low PMA and low VBD according to published cutoffs. The primary outcome was 1-year all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes were 30-day mortality, hospital length of stay, disposition, and worsening disability. Multivariable logistic regression was used to adjust for potential confounders.

Results

Of the 605 patients (271 [45%] female) in this study, 437 (72%) were octogenarian; the mean (SD) age was 82.6 (6.2) years. Mean (SD) PMA was 22.1 (4.5) cm2 in men and 15.4 (3.5) cm2 in women. Mean (SD) VBD was 104.8 (35.5) Hounsfield units (HU) in men and 98.8 (34.1) HU in women. Ninety-one patients (15%) met the criteria for osteosarcopenia and had higher rates of frailty, fractures, and malnutrition at baseline. One-year mortality was highest in patients with osteosarcopenia (29 patients [32%]) followed by those with low PMA alone (18 patients [14%]), low VBD alone (16 patients [11%]), and normal bone and muscle status (21 patients [9%]) (P < .001). Osteosarcopenia, but not low VBD or PMA alone, was independently associated with 1-year mortality (odds ratio [OR], 3.18; 95% CI, 1.54-6.57) and 1-year worsening disability (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.19-3.74). The association persisted in sensitivity analyses adjusting for the Essential Frailty Toolset, Clinical Frailty Scale, and geriatric conditions such as malnutrition and disability.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings suggest that osteosarcopenia detected using clinical CT scans could be used to identify frail patients with a 3-fold increase in 1-year mortality following TAVR. This opportunistic method for osteosarcopenia assessment could be used to improve risk prediction, support decision-making, and trigger rehabilitation interventions in older adults.

This cohort study examines whether there is an association between osteosarcopenia and adverse outcomes, such as increased risk of mortality, in older adults following transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).

Introduction

Osteosarcopenia is the concomitant presence of low bone density (osteopenia or osteoporosis) and low muscle mass and quality (sarcopenia). Osteoporosis results in decreased bone strength, causing increased risk of fractures.1 Sarcopenia results in decreased muscle strength, causing increased risk of falls and sedentariness.2 Together, they predispose patients to accelerated decline in functional status. Both conditions coexist when the balance between synthesis and elimination of bone and muscle tissue is disturbed due to age-related pathophysiological changes and cross talk mediated by paracrine and endocrine signaling molecules.3 These changes include lower levels of sex hormones, higher levels of cortisol, vitamin D deficiency, and insulin resistance with infiltration of fat in bone and muscle. The rate of loss of bone density and muscle mass is potentiated by malnutrition and sedentariness, common in older adults.

The prevalence of osteosarcopenia has been estimated to be between 5% and 37% in community-dwelling older adults,4 although it remains underdiagnosed in most cases. Compared with osteoporosis or sarcopenia alone, osteosarcopenia amplifies the risks of frailty, disability, hospitalization, and death.5 Osteosarcopenia is increasingly viewed as a key component of frailty, which in turn is associated with vulnerability to stressors and adverse health outcomes in older adults.6 While numerous studies have demonstrated the impact of frailty7,8 and sarcopenia9,10 on mortality and major morbidity following cardiac surgery or transcatheter intervention, the incremental impact of osteosarcopenia has yet to be evaluated. Thus, the present study sought to investigate the radiologic assessment and prognostic impact of osteosarcopenia in a multicenter cohort of patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).

Methods

Study Population and Design

Patients aged 70 years or older who had aortic stenosis treated by TAVR were prospectively enrolled in the Frailty in Aortic Valve Replacement (FRAILTY-AVR)7 cohort study, which was conducted at 14 centers in Canada, the United States, and France between 2012 and 2016 (10 of which contributed to this study but did not necessarily enroll patients throughout the entire study period). Patients at the McGill University–affiliated center in Montreal, Québec, Canada, were enrolled on an ongoing basis up to 2022. A comprehensive assessment of frailty and geriatric domains was performed before the procedure. Follow-up for clinical and functional outcomes was performed 1 year after the procedure. Osteosarcopenia was assessed from computed tomography (CT) scans that were routinely acquired for procedural planning before TAVR. Exclusion criteria were lack of informed consent, emergent procedure, unstable vital signs, CT field of view not including the abdomen, or CT files not retrievable. Research ethics boards at each hospital approved this study, and patients provided written informed consent to participate.

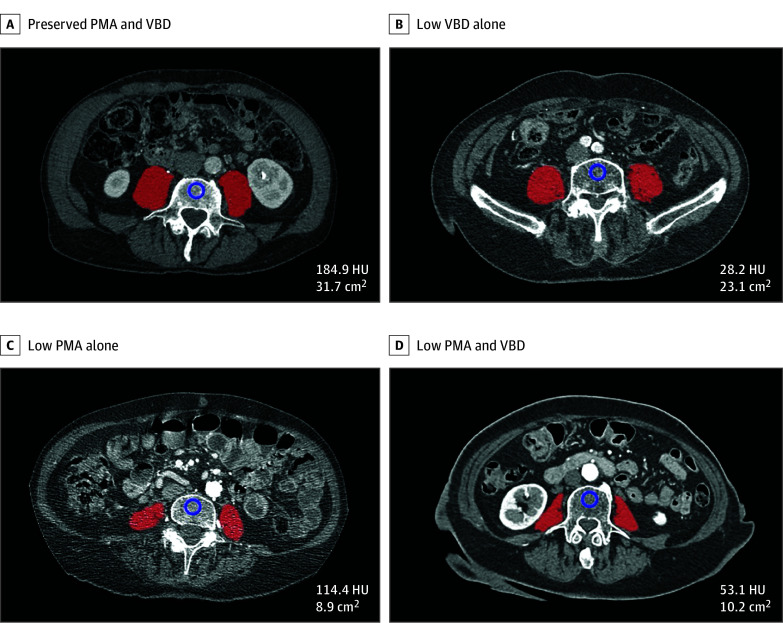

Bone Assessment

Vertebral bone density (VBD) was represented by the trabecular attenuation of the first 4 lumbar vertebrae on axial CT images acquired before TAVR. The L1, L2, L3, and L4 vertebral levels were chosen for trabecular attenuation measurements as they are easily identifiable and have been used in normative reference studies, with low VBD defined as less than 90 Hounsfield units (HU).11 Using OsiriX version 9 software (Pixmeo SARL), 2 trained observers overseen by a senior radiologist manually traced an ovoid region of interest in the center of the vertebral body (Figure 1) to measure the mean attenuation in Hounsfield units, which was averaged across the 4 vertebrae. Bone abnormalities, artifacts, or lesions were avoided. Levels where a reliable trabecular measurement was not feasible were excluded. For vertebral fracture assessment (an explanatory cross-sectional correlate of VBD), the Genant method was used to evaluate all thoracic and lumbar levels. This method is proven to be reproducible and able to differentiate fractures from other deformities.11,12 A Genant grade of 2 or more was considered a vertebral fracture so as not to count mild vertebral deformities such as physiological wedging and short vertebral height.

Figure 1. Bone and Muscle Status by Computed Tomography.

Representative examples from a patient with preserved psoas muscle area (PMA) and vertebral bone density (VBD) (A), a patient with low VBD alone (B), a patient with low PMA alone (C), and a patient with low PMA and VBD (osteosarcopenia) (D). The measurements of VBD (in Hounsfield units [HU]) and PMA (in centimeters squared) are listed. The red mask denotes the segmented psoas muscles at the L4 vertebrae level; blue circle, the region of interest to assess trabecular attenuation.

Muscle Assessment

Muscle mass was represented by the cross-sectional psoas muscle area (PMA) on axial CT images acquired before TAVR. The L4 vertebral level was chosen for PMA measurements given the extensive prognostic data and published normative reference values at this level, with low PMA defined as less than 22 cm2 for men and less than 12 cm2 for women.13 This level was specified as the axial image immediately below the anterior-superior aspect of the bright vertebral end plate of L4, corroborated by a multiplanar reconstruction of the sagittal view. Using CoreSlicer version 1 web-based software (CoreSlicer.com),14 2 trained observers segmented the left and right psoas muscles with a smart paintbrush tool that had a programmed threshold range of 30 to 150 HU (Figure 1) designed to isolate muscle-density tissue.

Covariates

Covariates of interest were age, sex, height, weight, body mass index, individual comorbidities, and Charlson Comorbidity Index score. The TAVI2-SCORe,15 a TAVR-specific risk score, encompasses age of 85 years or older, female sex, recent myocardial infarction, reduced ejection fraction less than 35%, critical mean aortic gradient, porcelain aorta, anemia, and severe chronic kidney disease. Physical performance was measured with the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), with a score of 8 or lower out of 12 defined as abnormal. Additional geriatric domains included handgrip strength, Clinical Frailty Scale score, Essential Frailty Toolset (EFT) score, basic and instrumental activities of daily living, Mini-Mental State Examination score, Geriatric Depression Scale–Short Form score, and Mini Nutritional Assessment–Short Form score.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was 1-year all-cause mortality ascertained by a combination of the participating hospitals’ electronic health records, linked databases, and telephone follow-up with patients or their next of kin. The main secondary outcome was 1-year worsening disability (or death), defined as 2 or more basic and instrumental activities of daily living for which the patient newly required help or was completely unable to perform independently, ascertained by the interviewer-administered Older Americans Resources and Services questionnaire. Additional outcomes were 1-year poor outcome, defined as very low or worsening health-related quality of life, 1-month all-cause mortality, post-TAVR length of stay, and discharge to locations other than home (inpatient rehabilitation facilities, nursing homes, or other hospital facilities).

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean (SD) for continuous variables and as the number (percentage) of individuals for categorical variables. Patients were subdivided into 4 groups: (1) normal VBD and PMA, (2) low VBD and normal PMA, (3) normal VBD and low PMA, and (4) low VBD and PMA (indicating osteosarcopenia). Analysis of variance was used to detect differences in baseline characteristics and outcomes across groups. Logistic regression was used to detect differences in primary and secondary outcomes across groups, adjusting for the following confounders: age, sex, height, weight, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, TAVI2-SCORe, fracture(s), and baseline SPPB score. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to construct survival curves. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were used to confirm the optimal cutoff for VBD (in Hounsfield units) to discriminate vertebral fractures and to assess the area under the ROC curve (AUROC) for risk models with and without CT bone and muscle status. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata version 18 software (StataCorp LLC). Two-tailed P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 605 patients (271 [45%] female) with pre-TAVR CT scans were included in this analysis. Among them, 437 (72%) were octogenarian; the mean (SD) age was 82.6 (6.2) years. Those excluded due to lack of analyzable CT scans were otherwise similar in terms of age, sex, comorbidities, and outcomes. Mean (SD) VBD was 104.8 (35.5) HU in men and 98.8 (34.1) HU in women. Mean (SD) PMA was 22.1 (4.5) cm2 in men and 15.4 (3.5) cm2 in women. Accordingly, 238 patients (39%) were classified as having normal bone and muscle status, 150 (25%) as having low VBD alone, 126 (21%) as having low PMA alone, and 91 (15%) as having osteosarcopenia. eFigures 1 and 2 in Supplement 1 show the distributions of VBD and PMA stratified by sex. Figure 1 shows representative CT scan segmentations for each group.

Patients with normal bone and muscle status were younger and had better self-perceived general health and lower procedural risk (TAVI2-SCORe). Patients with osteosarcopenia and low PMA alone exhibited higher rates of frailty (according to various scales), cognitive impairment, malnutrition, low body weight, and slow gait speed. Patients with low VBD alone exhibited higher rates of fractures and diagnosed osteoporosis and were more likely to be female. Comorbidities were otherwise evenly distributed across groups. Table 1 shows summary statistics for baseline characteristics stratified by CT bone and muscle status. No patients were lost to follow-up for vital status up to 1 year (primary outcome).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics by Bone and Muscle Status.

| Characteristic | Normal (n = 238) | Low VBD (n = 150) | Low PMA (n = 126) | Osteosarcopenia (n = 91) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 81.0 (6.6) | 83.9 (5.5) | 82.7 (5.9) | 84.8 (5.3) | <.001 |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||||

| Female | 124 (52) | 98 (65) | 27 (21) | 22 (24) | <.001 |

| Male | 114 (48) | 52 (35) | 99 (79) | 69 (76) | |

| Height, mean (SD), m | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.6 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 78.3 (18.0) | 73.6 (17.4) | 70.0 (13.0) | 69.8 (12.4) | <.001 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28.6 (5.8) | 27.6 (5.7) | 25.0 (4.7) | 24.5 (3.5) | <.001 |

| TAVI2-SCORe, mean (SD) | 2.0 (0.9) | 2.1 (1.1) | 2.7 (1.0) | 2.7 (1.1) | <.001 |

| LVEF, mean (SD), % | 56.6 (12.3) | 57.5 (12.6) | 53.3 (14.6) | 54.3 (12.4) | .02 |

| NYHA class, mean (SD)a | 2.6 (0.6) | 2.6 (0.7) | 2.6 (0.7) | 2.7 (0.8) | .20 |

| Comorbidities, No. (%) | |||||

| Congestive heart failure | 76 (32) | 55 (37) | 57 (45) | 42 (46) | .03 |

| Coronary artery disease | 129 (54) | 85 (57) | 88 (70) | 61 (67) | .01 |

| Diabetes | 68 (29) | 35 (23) | 39 (31) | 25 (27) | .53 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 134 (56) | 83 (55) | 67 (53) | 54 (59) | .84 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 40 (17) | 26 (17) | 22 (17) | 21 (23) | .60 |

| Osteoporosis | 27 (11) | 37 (25) | 13 (10) | 11 (12) | <.001 |

| ≥1 Vertebral fracture | 49 (21) | 60 (40) | 30 (24) | 31 (34) | <.001 |

| Falls | 30 (13) | 24 (16) | 27 (21) | 15 (16) | .18 |

| Chronic lung disease | 47 (20) | 24 (16) | 28 (22) | 16 (18) | .59 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 3.5 (2.4) | 3.4 (2.3) | 4.1 (2.5) | 4.0 (2.6) | .05 |

| Frailty indices, mean (SD) | |||||

| Grip strength, kg | 24.9 (10.3) | 21.9 (8.5) | 24.1 (9.1) | 25.0 (8.9) | .01 |

| Gait speed, cm/s | 77.5 (36.3) | 70.7 (34.5) | 67.0 (30.9) | 73.4 (33.0) | .03 |

| Scorea | |||||

| SPPB | 7.2 (3.2) | 6.3 (3.0) | 6.5 (3.1) | 6.2 (3.1) | .005 |

| Fried | 1.9 (1.4) | 2.0 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.4) | 2.2 (1.3) | .02 |

| CFS | 3.6 (1.3) | 3.9 (1.1) | 3.9 (1.2) | 4.1 (1.2) | .004 |

| EFT | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.1) | 2.0 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.2) | <.001 |

| Disability | 1.5 (2.1) | 1.7 (2.1) | 1.7 (2.4) | 2.0 (2.8) | .40 |

| MMSE | 27.2 (2.9) | 27.0 (2.8) | 26.3 (3.3) | 26.3 (3.1) | .01 |

| MNA-SF | 11.9 (2.2) | 11.8 (2.2) | 10.8 (2.7) | 10.9 (2.6) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CFS, Clinical Frailty Scale; EFT, Essential Frailty Toolset; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MNA-SF, Mini Nutritional Assessment–Short Form; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PMA, psoas muscle area; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery; TAVI2-SCORe, porcelain thoracic aorta, anemia, left ventricular dysfunction, recent myocardial infarction, male sex, critical aortic valve stenosis, old age, and renal dysfunction; VBD, vertebral bone density.

Maximal possible values are as follows: NYHA class, 4; SPPB score, 12; Fried score, 5; CFS score, 9; EFT score, 5; disability score, 14; MMSE score, 30; and MNA-SF score, 14.

Association of Osteosarcopenia With Prevalent Fractures and Physical Performance

Vertebral fractures ascertained on the pre-TAVR CT scan ranged in prevalence from 49 patients (21%) with normal bone and muscle status up to 60 patients (40%) with low VBD (P < .001) (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1). Fractures were not significantly associated with a medical record–based diagnosis of osteoporosis, which was clinically documented in 88 patients. Multiple fractures were more commonly observed in those with osteosarcopenia or low VBD alone. ROC analysis showed that the optimal cutoff for VBD to predict fractures was less than 90 HU (identical to the published cutoff chosen to define osteosarcopenia), yielding the highest Youden index of 0.21 (AUROC of 0.65). Mean (SD) SPPB scores, lower being worse, ranged from 7.2 (3.2) in patients with normal bone and muscle status to 6.2 (3.1) in patients with osteosarcopenia (P = .005) (eFigure 4 in Supplement 1). SPPB scores were further reduced in patients with lower psoas muscle density, suggestive of intramuscular adipose tissue infiltration, and the PMA and psoas muscle density were independently contributive with no observed direct correlation between them.

Association of Osteosarcopenia With Clinical Outcomes

Table 2 shows clinical outcomes stratified by bone and muscle status. One-year mortality was highest in patients with osteosarcopenia (29 patients [32%]), followed by those with low PMA alone (18 patients [14%]), low VBD alone (16 patients [11%]), and normal bone and muscle status (21 patients [9%]) (P < .001) (Figure 2). Osteosarcopenia, but not low VBD or PMA alone, was independently associated with 1-year mortality (odds ratio [OR], 3.18; 95% CI, 1.54-6.57) after adjusting for confounders and scores on frailty scales such as the SPPB, EFT, and Clinical Frailty Scale (Table 3; eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Osteosarcopenia was also independently associated with 1-year worsening disability (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.19-3.74) (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). The ancillary domain of physical performance, as measured by the SPPB, was associated with mortality, whereas vertebral fracture was not. The mortality rate was incrementally higher when low PMA was observed in combination with low SPPB score or low VBD (eFigures 5, 6, and 7 in Supplement 1). Given a baseline AUROC of 0.63 (95% CI, 0.57-0.69) observed for the TAVI2-SCORe, addition of CT-based osteosarcopenia or SPPB each improved the AUROC to 0.68 (95% CI, 0.62-0.75), and together they improved it to 0.72 (95% CI, 0.66-0.78) (P = .004) or 0.77 (95% CI, 0.72-0.89) with all covariates considered (eTable 3 in Supplement 1).

Table 2. Outcomes by Bone and Muscle Status.

| Outcome | Normal (n = 238) | Low VBD (n = 150) | Low PMA (n = 126) | Osteosarcopenia (n = 91) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 y, No. (%) | |||||

| All-cause mortality | 21 (9) | 16 (11) | 18 (14) | 29 (32) | <.001 |

| Worsening disability | 74 (35) | 50 (38) | 38 (35) | 53 (60) | <.001 |

| Poor outcome | 44 (18) | 30 (20) | 30 (24) | 43 (47) | <.001 |

| 1 mo | |||||

| All-cause mortality, No. (%) | 6 (3) | 2 (1) | 4 (3) | 9 (10) | .003 |

| Length of stay, mean (SD), d | 5.6 (6.3) | 6.8 (8.8) | 6.5 (8.2) | 8.0 (10.1) | .09 |

| Discharge not home, No. (%) | 41 (18) | 31 (21) | 26 (21) | 23 (27) | .33 |

Abbreviations: PMA, psoas muscle area; VBD, vertebral bone density.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Plot of Survival by Bone and Muscle Status.

Normal indicates preserved psoas muscle area (PMA) and vertebral bone density (VBD). Osteosarcopenia indicates low PMA and VBD.

Table 3. Multivariable Model for All-Cause Mortality at 1 Year.

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, per y | 0.98 (0.93-1.03) | .37 |

| Female | 2.18 (0.85-5.56) | .10 |

| Height, per cm | 1.06 (1.02-1.10) | .01 |

| Weight, per kg | 0.96 (0.94-0.98) | .001 |

| TAVI2-SCORe, per point | 1.43 (1.06-1.93) | .02 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, per point | 1.15 (1.03-1.27) | .01 |

| SPPB score, per point | 0.89 (0.81-0.96) | .01 |

| Fracture | 1.02 (0.59-1.78) | .94 |

| CT bone and muscle status | ||

| Normal | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Low VBD alone | 0.98 (0.47-2.05) | .96 |

| Low PMA alone | 1.03 (0.48-2.24) | .93 |

| Osteosarcopenia | 3.18 (1.54-6.57) | .002 |

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; NA, not applicable; PMA, psoas muscle area; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery; TAVI2-SCORe, porcelain thoracic aorta, anemia, left ventricular dysfunction, recent myocardial infarction, male sex, critical aortic valve stenosis, old age, and renal dysfunction; VBD, vertebral bone density.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is first study to examine the prognostic impact of osteosarcopenia in older cardiovascular patients, specifically those with severe aortic stenosis undergoing TAVR. Radiographic assessment of osteosarcopenia proved to be a valid and efficient approach to screen patients and identify a subpopulation with high rates of frailty, fractures, disability, and malnutrition. After adjusting for clinical risk factors and frailty scores, osteosarcopenia—but not low PMA or VBD alone—was associated with a 3-fold increase in risk of fatal adverse events and a 2-fold increase in worsening disability at 1 year. Importantly, relying on measures of low muscle mass alone, without considering bone health or physical performance, is likely to misclassify many patients as frail. Our findings support CT-based osteosarcopenia as a novel indicator of frailty and mortality risk in older adults undergoing TAVR.

This study builds on our prior research highlighting the prevalence and prognostic impact of frailty markers in patients undergoing TAVR. First, clinical markers of frailty, such as weakness, malnutrition, anemia, and cognitive impairment, were found to be associated with 1-year mortality and worsening disability and were used to construct the EFT.7 Next, a radiographic marker of muscle mass (PMA) was found to be associated with outcomes and was used to construct an index of sarcopenia in combination with a clinical marker of muscle strength (chair rise time).9 Now, the same radiographic marker of muscle mass (PMA) was used to construct an index of osteosarcopenia in combination with a radiographic marker of bone density (vertebral trabecular attenuation) and was found to be incrementally associated with 1-year mortality and worsening disability. Our preference is to integrate bedside and radiographic markers of frailty, but if personnel or time is not available for the former or if the patient is unable to mobilize due to illness or deficits, the latter can conveniently be assessed from the clinically available CT scan.

Many prior research groups have taken advantage of pre-TAVR CT datasets to demonstrate an association between low muscle mass and postprocedural outcomes16; however, the prognostic value has been somewhat inconsistent in the absence of functional measures. One of the reasons for this is because patients with isolated low muscle mass may manifest good muscle quality and, consequently, preserved muscle strength and favorable prognosis. This subset of patients with low muscle mass and preserved strength is more likely to have preserved bone density. Thus, if functional measurements of muscle strength are not available, bone density serves as a proxy indicator and supporting criterion for the diagnosis of sarcopenia. Another reason is that bone density carries prognostic value for potentially fatal adverse events such as falls and fragility fractures11,17,18,19,20,21 and serves as a direct indicator for the diagnosis of osteoporosis. Establishing the diagnosis of osteosarcopenia also opens the door for therapeutic interventions that have shown promising effects, especially exercise programs combining aerobic and resistance training, ideally initiated in cardiac rehabilitation.22,23,24 Further research is needed to pinpoint the effective mode, intensity, and duration of these interventions.

Although our study focuses on the prognostic value of osteosarcopenia in patients undergoing TAVR, the implications extend far beyond this group of patients. Identifying patients with prognostically relevant phenotypes of frailty, as signified by osteosarcopenia, is crucial in a wide range of clinical scenarios. Osteosarcopenia as a marker of frailty could significantly influence the shared decision-making and management of older patients with ischemic heart disease being considered for revascularization, those with advanced heart failure being considered for mechanical circulatory support, and those with mitral and tricuspid valve regurgitation being considered for surgical or transcatheter repair. The latter is particularly relevant given the expansion of transcatheter heart valve technologies that are increasingly used in patients who are not candidates for open heart surgery. By adding radiologic biomarkers to the clinical evaluation, the heart team acquires a more comprehensive understanding of the patient’s health status. This, in turn, enables more personalized care strategies and potentially improves outcomes in alignment with the patient’s preferences and goals.

Low bone density has been shown to be an independent risk factor for aortic valve calcification25 with shared mechanistic connections between osteoporosis and calcific aortic stenosis.26,27 Furthermore, shared mechanistic connections exist between osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and heart failure. The age-related deterioration of muscle and bone is interconnected by cross talk of myokines, osteokines, and adipokines,28 which in turn can cause secretion of natriuretic peptides and predispose to the development of heart failure.29 Thus, simultaneous deterioration of muscle and bone (known as osteosarcopenia) not only is associated with falls, fractures, and mortality in community-dwelling older adults30 but can also be associated with valvular-vascular calcification and incident heart failure. This amplifies the association with mortality, particularly in high-risk populations, such as the older adults with severe aortic stenosis and multimorbidity in this study.

Limitations

A few limitations should be acknowledged. The potential for residual confounding cannot be excluded since socioeconomic, lifestyle, and genetic covariates were not captured and comorbidities were represented with limited levels of granularity. That said, the association between osteosarcopenia and mortality was not materially attenuated after adjusting for an expanded list of more than 20 potential confounders. While normative reference values for PMA and VBD have been proposed and were used for this study, these have yet to be validated in multicenter cross-platform studies. PMA and VBD are measures of sentinel muscle and bone groups, which usually correlate closely with whole-body measurements. However, preferential atrophy of the psoas muscle may be observed in patients with lumbar spine radiculopathy or hip joint osteoarthritis. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry is the testing modality commonly used to diagnose osteopenia.1 CT-based VBD, with or without intravenous contrast, correlates well with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry results31 and has high interobserver agreement.32 Implementation of CT-based VBD and PMA measurement in clinical workflows is not yet mainstream, but it is fairly simple for a (nonradiologist) clinician to measure in less than 5 minutes and can now be automated using deep learning algorithms to overcome implementation barriers.

Conclusions

Opportunistic assessment of muscle mass and bone density is readily feasible from CT scans acquired for routine TAVR planning. The combined phenotype of osteosarcopenia was found to be associated with a 3-fold increase in post-TAVR mortality and a 2-fold increase in incident disability. The prognostic value of osteosarcopenia was superior to muscle mass alone, which may misclassify patients as frail when used in isolation, and was incremental to traditional risk factors and physical performance measures. Beyond its clinical applicability for risk prediction and shared decision-making, osteosarcopenia is an actionable finding for referral to cardiac rehabilitation or programs in which exercise and nutritional interventions can be initiated with the goal of improving musculoskeletal health and physical functioning following TAVR.

eTable 1. Expanded Multivariable Model for Mortality at 1 Year

eTable 2. Multivariable Model for Worsening Disability at 1 Year

eTable 3. Discrimination of Models for Mortality at 1 Year

eFigure 1. Distribution of Vertebral Bone Density in Males and Females

eFigure 2. Distribution of Psoas Muscle Area in Males and Females

eFigure 3. Vertebral Fractures by Bone-Muscle Status

eFigure 4. Physical Performance by Bone-Muscle Status

eFigure 5. Mortality Rate by Bone-Muscle Status

eFigure 6. Mortality Rate by Bone Density & Fracture

eFigure 7. Mortality Rate by Muscle Mass & Performance

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Siris ES, Adler R, Bilezikian J, et al. The clinical diagnosis of osteoporosis: a position statement from the National Bone Health Alliance Working Group. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(5):1439-1443. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2655-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. ; Writing Group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2); Extended Group for EWGSOP2 . Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16-31. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He C, He W, Hou J, et al. Bone and muscle crosstalk in aging. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:585644. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.585644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nielsen BR, Abdulla J, Andersen HE, Schwarz P, Suetta C. Sarcopenia and osteoporosis in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Geriatr Med. 2018;9(4):419-434. doi: 10.1007/s41999-018-0079-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirk B, Zanker J, Duque G. Osteosarcopenia: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment—facts and numbers. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020;11(3):609-618. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoogendijk EO, Romero L, Sánchez-Jurado PM, et al. A new functional classification based on frailty and disability stratifies the risk for mortality among older adults: the FRADEA study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(9):1105-1110. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.01.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Afilalo J, Lauck S, Kim DH, et al. Frailty in older adults undergoing aortic valve replacement: the FRAILTY-AVR study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(6):689-700. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anand A, Harley C, Visvanathan A, et al. The relationship between preoperative frailty and outcomes following transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2017;3(2):123-132. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcw030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mamane S, Mullie L, Lok Ok Choo W, et al. ; FRAILTY-AVR Investigators . Sarcopenia in older adults undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(25):3178-3180. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang YW, Pan P, Xia X, Zhou YW, Ge ML. Prognostic value of sarcopenia in older adults with transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2023;115:105125. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2023.105125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graffy PM, Lee SJ, Ziemlewicz TJ, Pickhardt PJ. Prevalence of vertebral compression fractures on routine CT scans according to L1 trabecular attenuation: determining relevant thresholds for opportunistic osteoporosis screening. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;209(3):491-496. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.17853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Genant HK, Wu CY, van Kuijk C, Nevitt MC. Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8(9):1137-1148. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Marco D, Mamane S, Choo W, et al. Muscle area and density assessed by abdominal computed tomography in healthy adults: effect of normal aging and derivation of reference values. J Nutr Health Aging. 2022;26(2):243-246. doi: 10.1007/s12603-022-1746-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mullie L, Afilalo J. CoreSlicer: a web toolkit for analytic morphomics. BMC Med Imaging. 2019;19(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12880-019-0316-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Debonnaire P, Fusini L, Wolterbeek R, et al. Value of the “TAVI2-SCORe” versus surgical risk scores for prediction of one year mortality in 511 patients who underwent transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(2):234-242. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertschi D, Kiss CM, Schoenenberger AW, Stuck AE, Kressig RW. Sarcopenia in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI): a systematic review of the literature. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(1):64-70. doi: 10.1007/s12603-020-1448-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pickhardt PJ, Pooler BD, Lauder T, del Rio AM, Bruce RJ, Binkley N. Opportunistic screening for osteoporosis using abdominal computed tomography scans obtained for other indications. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(8):588-595. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim YW, Kim JH, Yoon SH, et al. Vertebral bone attenuation on low-dose chest CT: quantitative volumetric analysis for bone fragility assessment. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(1):329-338. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3724-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel N, Dahl K, O’Rourke R, et al. Vertebral CT attenuation outperforms standard clinical fracture risk prediction tools in detecting osteoporotic disease in lung cancer screening participants. Br J Radiol. 2023;96(1151):20220992. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20220992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li YL, Wong KH, Law MW, et al. Opportunistic screening for osteoporosis in abdominal computed tomography for Chinese population. Arch Osteoporos. 2018;13(1):76. doi: 10.1007/s11657-018-0492-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berger-Groch J, Thiesen DM, Ntalos D, Hennes F, Hartel MJ. Assessment of bone quality at the lumbar and sacral spine using CT scans: a retrospective feasibility study in 50 comparing CT and DXA data. Eur Spine J. 2020;29(5):1098-1104. doi: 10.1007/s00586-020-06292-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fatima M, Brennan-Olsen SL, Duque G. Therapeutic approaches to osteosarcopenia: insights for the clinician. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2019;11:X19867009. doi: 10.1177/1759720X19867009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atlihan R, Kirk B, Duque G. Non-pharmacological interventions in osteosarcopenia: a systematic review. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(1):25-32. doi: 10.1007/s12603-020-1537-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Afilalo J. Evaluating and treating frailty in cardiac rehabilitation. Clin Geriatr Med. 2019;35(4):445-457. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2019.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carrai P, Camarri S, Pondrelli CR, Gonnelli S, Caffarelli C. Calcification of cardiac valves in metabolic bone disease: an updated review of clinical studies. Clin Interv Aging. 2020;15:1085-1095. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S244063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hekimian G, Boutten A, Flamant M, et al. Progression of aortic valve stenosis is associated with bone remodelling and secondary hyperparathyroidism in elderly patients—the COFRASA study. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(25):1915-1922. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goody PR, Hosen MR, Christmann D, et al. Aortic valve stenosis: from basic mechanisms to novel therapeutic targets. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40(4):885-900. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.313067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirk B, Feehan J, Lombardi G, Duque G. Muscle, bone, and fat crosstalk: the biological role of myokines, osteokines, and adipokines. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2020;18(4):388-400. doi: 10.1007/s11914-020-00599-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loncar G, Fülster S, von Haehling S, Popovic V. Metabolism and the heart: an overview of muscle, fat, and bone metabolism in heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2013;162(2):77-85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.09.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teng Z, Zhu Y, Teng Y, et al. The analysis of osteosarcopenia as a risk factor for fractures, mortality, and falls. Osteoporos Int. 2021;32(11):2173-2183. doi: 10.1007/s00198-021-05963-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jang S, Graffy PM, Ziemlewicz TJ, Lee SJ, Summers RM, Pickhardt PJ. Opportunistic osteoporosis screening at routine abdominal and thoracic CT: normative L1 trabecular attenuation values in more than 20 000 adults. Radiology. 2019;291(2):360-367. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019181648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pickhardt PJ, Lee LJ, del Rio AM, et al. Simultaneous screening for osteoporosis at CT colonography: bone mineral density assessment using MDCT attenuation techniques compared with the DXA reference standard. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(9):2194-2203. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Expanded Multivariable Model for Mortality at 1 Year

eTable 2. Multivariable Model for Worsening Disability at 1 Year

eTable 3. Discrimination of Models for Mortality at 1 Year

eFigure 1. Distribution of Vertebral Bone Density in Males and Females

eFigure 2. Distribution of Psoas Muscle Area in Males and Females

eFigure 3. Vertebral Fractures by Bone-Muscle Status

eFigure 4. Physical Performance by Bone-Muscle Status

eFigure 5. Mortality Rate by Bone-Muscle Status

eFigure 6. Mortality Rate by Bone Density & Fracture

eFigure 7. Mortality Rate by Muscle Mass & Performance

Data Sharing Statement