Abstract

Plasmodium falciparum variant antigens named erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) are important targets for developing a protective immunity to malaria caused by P. falciparum. One of the major challenges in P. falciparum proteomics studies is identifying PfEMP1s at the protein level due to antigenic variation. To identify these PfEMP1s using shotgun proteomics, we developed a pipeline that searches high-resolution mass spectrometry spectra against a custom protein sequence database. A local alignment algorithm, LAX, was developed as a part of the pipeline that matches peptide sequences to the most similar PfEMP1 and calculates a weight value based on peptide’s uniqueness used for PfEMP1 protein inference. The pipeline was first validated in the analysis of a laboratory strain with a known PfEMP1, then it was implemented on the analysis of parasite isolates from malaria-infected pregnant women and finally on the analysis of parasite isolates from malaria-infected children where there was an increase of PfEMP1s identified in 27 out of 31 isolates using the expanded database.

Keywords: variant antigens, proteogenomics, Plasmodium falciparum proteomics, PfEMP1

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Among malaria parasites that infect humans, Plasmodium falciparum is the deadliest. In areas of high transmission, young children are most susceptible, while adults develop immunity that controls parasitemia and disease.1 Protective immunity has been associated with the development of antibodies that recognize parasite proteins exported to the surface of infected erythrocytes (IE).2 P. falciparum virulence has been associated with parasite sequestration in the vasculature, where they adhere to endothelial receptors and avoid clearance by the spleen.3 This adhesion is mediated by the P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) variant surface antigen family, encoded by the var gene family.4 Each genome encodes about 60 var genes, characterized by high sequence diversity. However, antibody development against PfEMP1 is ordered: children develop antibodies to some PfEMP1 domains earlier than others,5 consistent with greater IE surface recognition of parasites infecting young children and children with severe malaria (SM).6–8

Because of the role of PfEMP1 in naturally acquired immunity, numerous studies have sought to identify PfEMP1 expressed by P. falciparum parasites collected from children. To date, most var gene expression analysis has relied on qPCR to compare expression levels with limited studies at the protein level.9,10 However, qPCR analysis has focused on identifying specific PfEMP1 domains. The major hurdle in the analysis of PfEMP1s by proteomics is the high degree of sequence variation. Proteomics analysis using liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (MS) depends on gene sequences for alignment of MS spectra, but it is impossible to build a comprehensive var gene sequence database (DB) that includes every possible PfEMP1.

In recent years, multiple studies focused on using proteomics and genomics tools, termed proteogenomics,11 have sought to identify protein variations such as those associated with cancer or sequencing antibodies (reviewed in ref 12). The initial focus of proteogenomics was to improve genome annotation and characterization.11 The current implementation of proteogenomics is to interpret MS/MS spectra by creating a customized DB that contains predicted novel protein sequences and sequence variants. The customized DB is generated using genomic or transcriptomic sequence information. For example, to study cancer tissues and cell lines, Lobas et al. proposed a method by which a SNP-containing DB was created from the HEK293 exome obtained after standard cell biology manipulations to identify variant peptides.13 In another approach, in sequencing monoclonal antibodies,14,15 methods have been developed to use databases or just de novo peptide sequencing to identify the full sequence of the monoclonal antibody. The spectra are acquired from multiple digests with various proteases, and then using a DB containing known V, D, J, and C segments, a template is created. Spectra are aligned against this template sequence and extended to construct a sequence. However, our goal is to identify highly variant antigens in a complex protein sample containing human and P. falciparum proteins that cannot be identified with existing tools. To overcome this obstacle, we developed a new proteogenomic pipeline that searches high-resolution mass spectrometry spectra against a custom protein sequence database and de novo sequencing of peptides.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Study Population and Clinical Definitions

Parasite samples collected from children participating in this study were enrolled between August 2010 and December 2014 into three cohorts conducted as part of the Immuno-Epidemiology (IMEP) project in Ouelessebougou, Mali: 1. A longitudinal birth cohort of pregnant women and their children; 2. A longitudinal study of children aged 0–3 years; 3. Children aged 0–10 years hospitalized with severe malaria. A parent or guardian gave informed consent for their child’s participation in the study, after receiving a study explanation form and an oral explanation from the study clinicians in their native language. The protocol and study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT01168271) and the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy, and Dentistry at the University of Bamako, Mali. All study methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the institutional review boards. Severe malaria was defined as parasitemia together with at least one of the following WHO criteria for severe malaria: ≥2 convulsions in the past 24 h; prostration (inability to sit unaided or in younger infant’s inability to move/feed); hemoglobin <5 g/dL; respiratory distress (hyperventilation with deep breathing, intercostal recessions, and/or irregular breathing); coma (Blantyre score ≤2). The current study included 31 samples from P. falciparum-infected children and 2 samples from P. falciparum-infected pregnant women.

Sample Preparation

Blood samples collected from malaria-infected children matured to the trophozoite/schizont stages in in-vitro culture for 16–20 h. Mature parasite forms were enriched to >90% using percoll gradient. Membrane proteins were extracted by sequential detergent isolation using 1% triton X-100 and 1% SDS.16

Samples fractionated by size in 1D SDS-PAGE gels using a Bio-Rad Criterion Tris HCL 4–20% polyacrylamide gradient gel. The gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (Imperial Protein Stain; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) for 10 min and destained using ddH2O (3 × 5 min, then 1 h). The gel was divided from top to bottom into 20 strips over the entire molecular weight range of the gel. Each strip was diced into small pieces (1 mm3) and placed into labeled Protein LoBind tubes (Eppendorf). The gel pieces were destained by adding 100 μL of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (NH4HCO3)/50% acetonitrile (ACN) for 10 min and 100 μL of 50 mM NH4HCO3 sequentially and repeated twice. The samples were reduced in a solution of 20 mM Dithiothreitol and 50 mM NH4HCO3 for 20 min at 60 °C, alkylated in a solution containing 50 mM Iodoacetamide and 50 mM NH4HCO3 for 20 min in the dark at room temperature. The gel pieces were washed with 50 mM NH4CO3 and dehydrated in a solution containing 50 mM NH4HCO3/50% ACN. The samples were dried using the SpeedVac. The samples were rehydrated and digested with trypsin in the solution and in a ratio of 1:50 (enzyme: total protein) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Digestion was stopped by extraction with 50% ACN/0.1% formic acid (FA), and the extracted peptide samples were dried using the SpeedVac to evaporate ACN and reconstituted with 0.1% FA. All samples were desalted using C18 zip tips (Millipore).

RNA SEQ Assembly of Novel PFEMP1

Twenty-seven samples were analyzed by RNA sequencing, RNA was extracted using QIAGEN kit. Per sample, 200 nanograms was used to prepare cDNA libraries using the Illumina Ribo-Zero GOLD and Poly-A and ran in the paired ended mode in a HiSeq2000 instrument to obtain 20 million reads per sample. Five of 27 samples were analyzed by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Transcriptomic de novo assemblies were built using a previously described method,17 briefly summarized here: (1) Raw sequencing reads were built with ABYSS and SOAP-denovo using various kmer (k) values; (2) Fragments were assembled by an iterative process comprised of BLAST and CAP3.2 Transcripts were translated into protein sequences by searching for ORFs in all six frames and keeping anything without stop codon. Novel protein constructs were down-selected to first retain only parasite proteins, then to retain only PfEMP1 proteins. Domain structures of new PfEMP1 constructs were identified by protein sequence similarity to known PfEMP1s, only new PfEMP1s with at least one domain were retained. Further filtering of PfEMP1 constructs shorter than 650 amino acids (less than 2 identified domains) and highly similar (more than 95% identity) were discarded.

LC–MS/MS

Tryptic-digested peptide mixtures were loaded on to a reverse phase C-18 precolumn in line with an analytical column (Acclaim PepMap, 75 μm × 15 cm, 2 μm, 100 Å). The peptides were separated using a gradient of 5% to 30% of solvent B (0.1% formic acid, acetonitrile) for 75 min and then to 95% of solvent B for additional 50 min at a flow rate of 300 nL/min. The peptides were analyzed in the data-dependent mode in the LTQ Orbitrap Velos, and the top 20 precursors were fragmented using CID in a Ion Trap with a collision energy of 35. The mass window for the precursor ion selection was 2 Da, and a minimum of 5000 counts was needed to trigger the MS/MS. The MS1 was acquired in the Orbitrap at a resolution of 60 000 and MS2 in the ion trap (28 children samples). For 3 children samples, MS2 was acquired in the Orbitrap at a resolution of 15 000.

BIOINFORMATIC ANALYSIS

PEAKS Studio

Acquired spectra were analyzed using the PEAKS Studio 8.5 (Bioinformatics Solutions, Inc, Waterloo, ON Canada) with a precursor tolerance of 10 ppm and tolerance of 0.8 Da (ion trap) and 0.02 for Orbitrap for MS/MS for CID against a combined database composed of Swiss Prot Human database (20,352 sequences), P. falciparum from PlasmoDB version 24 database (5,542 sequences), VSA database (385 VAR gene sequences from 8 strains18), and novel PfEMP1 construct database from RNA seq data (697 sequences). Sequences of known contaminants from the cRAP database were added (115 sequences). Carbamidomethyl (C), deamidation (N,Q), and oxidation (M) were selected as variable modifications, and one nonspecific cleavage at the peptide terminus and two missed cleave sites were allowed. The false discovery rate (FDR) for peptides was set to 1% by applying the target-decoy strategy in the PEAKS Studio. De novo peptides were exported at ALC ≥ 60. The output of PEAKS Studio contains the database peptides and de novo peptides and was the input for the LAX algorithm.

LAX Algorithm Description

The database and de novo peptides were the input for LAX, which is the local peptide assignment tool. This tool employs a relaxed local pairwise alignment strategy, as implemented in the R Biostrings package by function pairwiseAlignment, first described by Smith & Waterman.19 It finds the best matching location among a set of reference protein sequences (Human, P. falciparum, VSA, novel PfEMP1 constructs, and cRAP) to a given query peptide sequence and returns a score and details about the quality and location of the peptide match in the protein sequence. The reference sequence with the best match to a query peptide will get the highest score. Scoring is based on summing up the numeric rewards for matching or penalties for mismatching each amino acid of the query peptide, using a modified PAM70 substitution matrix. The standard PAM70 substitution matrix was chosen, as random DNA mutations are the most likely sources of PfEMP1 hypervariation. Then, the following custom modifications to PAM70 were made to account for three cases where mass accuracy is a limiting factor. Leucine and isoleucine (I, L) are isobaric and are, thus, completely indistinguishable. Two other amino acid pairs have very similar masses: glutamic acid and glutamine (E, Q), aspartic acid and asparagine (D, N). For these three cases, the standard mismatch score has been changed from a negative penalty to a positive reward, which is less than the reward for a perfect match. A perfect match for E is +7, if it is mismatched to Q, the score is +4. A perfect match for D is +6, if it is mismatched to N, the score is +4. LAX returns all reference protein hits that match the query peptide equally well, calculating the weight of each peptide match based on the number of protein (N) hits LAX returned, as 1/N to give unique peptide matches the highest weight and proportionally less weight to peptides matching multiple proteins. In addition to a score, protein assignment, and uniqueness weight for each peptide, LAX also calculates a percent match value that quantifies what percentage of amino acids in the peptide were perfect matches to the assigned protein sequence. Database peptides that are perfect protein matches get the highest percent match value (1.0) and de novo peptides get a lower percent match value that reflects how many mismatch amino acids were needed to find the best protein assignment.

The LAX analysis consists of the following 4 discrete steps: prefiltering of de novo peptides, peptides alignment and scoring, protein detection and FDR estimation, and construction of PfEMP1 matrices, which are the final PfEMP1 results from LAX.

Prefiltering of De Novo Peptides

To maximize the number of de novo peptides that are evaluated by LAX, a two-step filtering of de novo peptides based on the PEAKS ALC and LC scores is implemented. A Local Confidence (LC) score is generated by PEAKS for each amino acid call, and an Average Local Confidence (ALC) score for the peptide (arithmetic mean of the LCs). Extensive manual inspection of spectra matched to de novo peptides from six samples was completed, and this analysis determined that de novo peptides with ALC ≥ 80 are highly confidently matched to its de novo peptide sequence. Sequencing errors are more common at the peptide edges,20 and to maximize the information obtained by de novo sequencing, de novo peptides with an ALC score of 60 and above are then processed as follow:

Step 1: Trimming of low LC edge amino acids: For each de novo peptide, starting at the edges (N- and C- termini) and moving toward the center, LAX trims off any amino acids with LC scores below 60. As soon as an amino acid above that score is found, trimming stops for that peptide terminus. When done, the (possibly shorter) peptide is saved and its ALC is recalculated if it is at least 6 amino acids. Trimmed de novo peptides that are too short (below 6 amino acids) are discarded.

Step 2: Discarding of low ALC peptides: After trimming, all de novo peptides still having a recalculated ALC score below 80 are discarded.

Peptide Alignment and Scoring

All peptides (database and de novo) are submitted to LAX to generate protein assignment score, uniqueness weight, and percent match for all peptides. As implemented, LAX will always find at least one protein as the best match to every peptide (database or de novo) and report a nonzero score. Since de novo peptides never have perfect matches to reference proteins, some amount of mismatching amino acids must be tolerated, especially in the case of highly variant proteins like PfEMP1s. Nevertheless, de novo peptides may contain low-quality noise or other errors that do not represent true peptide sequences. To distinguish real peptides, a LAX score cutoff was used, peptides scoring above the cutoff are kept as real, while peptides scoring below the cutoff are discarded as noise. Since the LAX score is additive over the length of the peptide, longer perfect match peptides will return higher scores than shorter peptides, therefore all LAX scores are normalized by dividing by the peptide length to yield ScorePerAA units that are independent of the peptide length. The optimal score cutoff was then empirically deduced from a combination of: (1) the distribution of scores from database peptides (i.e., perfect matches); (2) correlation analysis of proteome protein abundance versus transcriptome gene expression for the 5 samples analyzed by both mass spectrometry and RNA seq (i.e., finding the LAX score cutoff that maximized agreement for each sample). The final setting of “LAX_SCORE_CUTOFF” was set at 4.3 per amino acid, and then only peptides with the score equal or higher go forward for determining protein detection.

Protein Detection and False Discovery Rate Estimation

All peptides passing the ScorePerAA and a cutoff of weight ≥ 0.1 were used to calculate protein detection for LAX. In addition to counting peptides, metrics that sum up both the peptide uniqueness weight and percent match value were generated. The difficulty in identifying PfEMP1 proteins is the degree of sequence variation in the context of complex protein samples. As described by various publications,21–23 protein-level FDR methods are challenging to establish, despite the consensus that it is widely needed for large-scale shotgun proteomics analysis. Because the main goal of our study is to identify proteins (PfEMP1s), we defined a protein-level FDR and implemented it within the LAX algorithm. FDR was calculated based on percent match because both DB-matched and de novo peptides contributed to the protein identification. To give universal measures of protein detection that can be compared across samples, the following equation was applied to each protein

To calculate FDR, a decoy protein database for LAX was used where the real proteins (Human, P. falciparum, VSA, novel PfEMP1 constructs, and cRAP) have their amino acids randomly shuffled. Every sample is rerun through the LAX algorithm using the decoy proteins DB to create a set of decoy results. The decoy results are filtered using the same ScorePerAA and cutoff for Weight, as described above. Normalized percent match is calculated for the decoy DB results in the same manner as the results obtained with the target DB. By comparing the normalized percent match the real target DB results against the normalized percent match of the decoy proteins, a False Discovery Rate (FDR) can be directly assigned to each real protein by determining the proportion of decoy proteins having a higher normalized percent match level.

PFEMP1 Matrices

The peptides (database and de novo) assigned to PfEMP1 proteins are exported as a matrix, where the rows contain all the peptides sequences and the columns contain the PfEMP1 proteins to show the relation between peptides assigned to PfEMP1 proteins. The output csv file contains three tables: File 1. “Count Matrix”, where the peptide sequence is the value for each row and the value of the column is the PfEMP1 region to which the peptide is aligned, for example, DBLd3. File 2. The “Weight Matrix” table contains the weight of the peptide assignment, for example, peptide matched to 10 proteins; the weight is 0.1. File 3. The “Final List” table contains PfEMP1s with at least 2 peptides with the cutoff of Weight ≥0.1 in two distinct locations, as shown by Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Output as shown by the Final List file containing PfEMP1 with at least 2 peptides. The protein-level FDR in column P and is the same for all peptides assigned to the protein, JOSvar232481_FR5_1-2277, as shown in this example from sample 210057_5Jul2014.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Pipeline Development

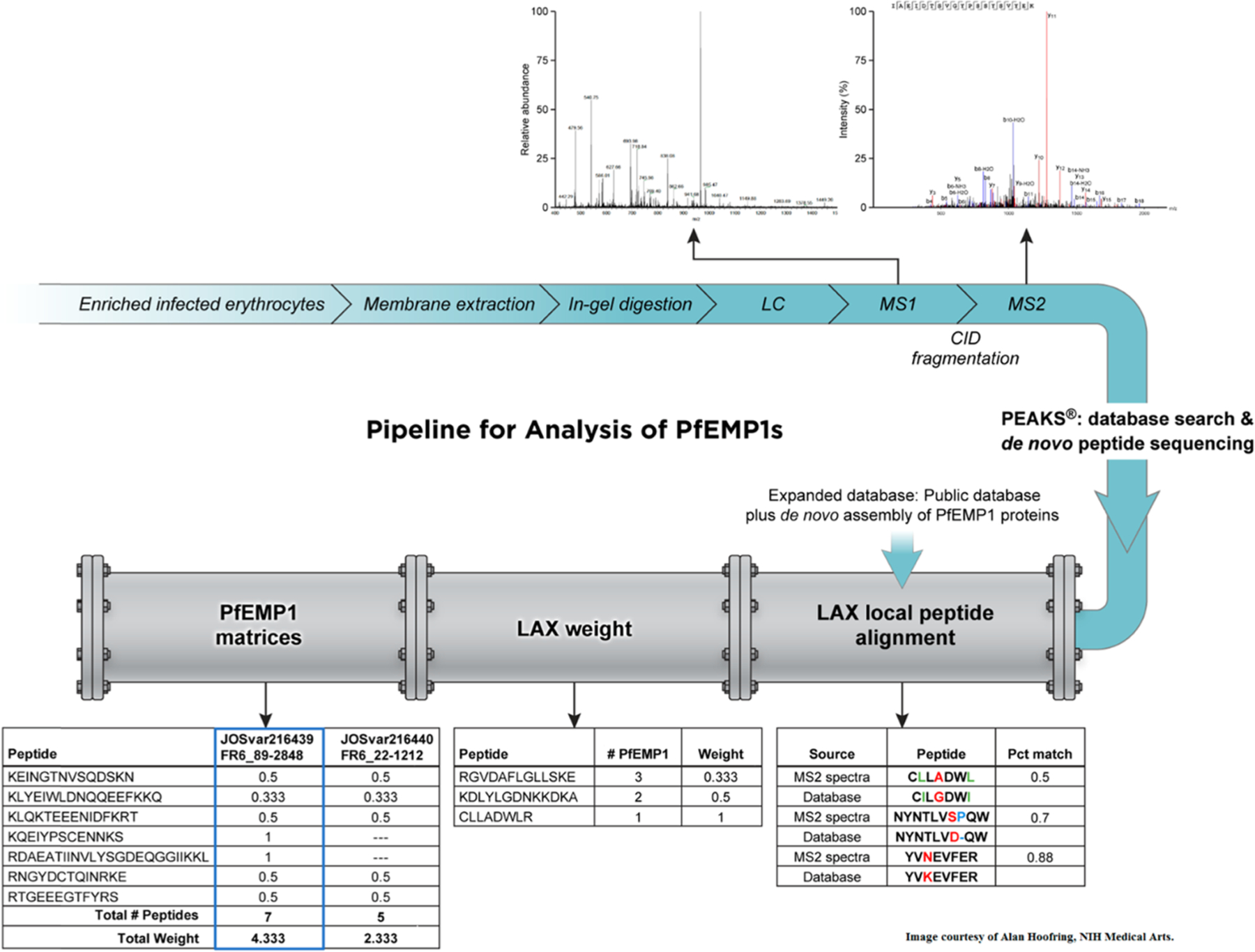

The two main components in the pipeline (Figure 2) developed for the identification of PfEMP1 in clinical parasite samples consist of the following: (1) Expanded DB containing public DB of human, P. falciparum sequences (including PfEMP1 sequences from 8 genomes: plasmodDB and varDOM18) and a DB that includes PfEMP1s obtained by RNA seq of clinical isolates that were assembled de novo (Sequences deposited to NCBI’s GenBank); (2) Development of a suitable algorithm for peptide alignment, LAX Local Peptide Alignment. LAX serves two purposes: (1) to match sequences to peptides identified by de novo sequencing to the most similar PfEMP1 in the DB, based on the pairwise alignment while allowing insertions/deletions, substitutions, and matching with a substring peptide; (2) to calculate the weight of each peptide best-matched to PfEMP1s. Commercial software assigns peptides as unique or nonunique, while proteins that are part of a family like PfEMP1 contain peptides conserved among several family members. A commercial software will randomly assign these peptides to one of the proteins resulting in many PfEMP1s with single unique and nonunique peptides and thus, low confidence identification. To resolve this, a cutoff for weight was introduced to LAX, to limit the results of PfEMP1 identification to those peptides that match 10 or less PfEMP1s in the DB. The weight value is calculated based on the number of proteins to which a peptide is matched, for example, a singleton match that only maps to a single protein is weighted 1, while peptides with equally high scoring matches to N PfEMP1s are weighted 1/N assigned to each protein. In theory, a conserved peptide can match up to the total number of PfEMP1s included in the database, as shown in Table S1. These “conserved” PfEMP1 peptides are not used to identify any single PfEMP1.

Figure 2.

Pipeline for the analysis of PfEMP1s consists of two components: (1) Expanded Database, which contains a public database and a de novo assembly of PfEMP1 proteins. (2) The Local Peptide Alignment (LAX) algorithm, which calculates peptide weight (LAX weight) and output PfEMP1 matrices to remove redundancies. The upstream part of the figure, in blue, shows the sample preparation steps prior to analysis with the pipeline. PEAKS database search and de novo peptide sequencing results are the input for the pipeline (Image courtesy of Alan Hoofring, NIH Medical Arts).

We first used this pipeline with a laboratory parasite line expressing a known PfEMP1. Placental malaria is characterized by IE adhesion to the receptor chondroitin sulfate A (CSA) that is mediated by a PfEMP1 named VAR2CSA.24,25 The analysis of CSA-selected FCR3 IE membranes (a parasite line isogenic with IT4 line26) with the public DB using PEAKS identified VAR2CSA-IT4var04 with 96 peptides, of which 26 are unique peptides, while 70 peptides were shared between multiple VAR2CSA sequences described as nonunique by PEAKS. The analysis with the expanded DB using PEAKS identified VAR2CSA-IT4var04 with 97 peptides, of which 17 are unique peptides, while 80 peptides were nonunique (Table 1). This was the first indication that using the expanded DB did not result in erroneous identification of non-VAR2CSA PfEMP1s. The analysis of the output from PEAKS (DB peptides and de novo peptides) with LAX using the expanded DB identified VAR2CSA-IT4var04 with 68 peptides, of which 17 have weights equal to 1 and 51 peptides have weights between 0.1 and 0.5 (Table 1). Twenty-nine peptides, which are identified by PEAKS but not in the final list of peptides from LAX, had weights below 0.1 and still matched VAR2CSA.

Table 1.

Samples Analyzed by PEAKS and LAX Using Expanded DBa

| isolate | FCR3 | PW201596 | PW211251 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PfEMP1 | IT4var04 | JOSvar221091 | JOSvar219095 FR4_1991-4789 | |

| PEAKS-expanded DB | total # peptides identified | 97 | 44 | 5 |

| # unique peptides | 17 | 0 | 1 | |

| # nonunique peptides | 80 | 44 | 4 | |

| LAX expanded DB | total # peptides identified (weight ≥ 0.1) | 68 | 20 | 5 |

| # peptides with weight = 1 | 17 | 0 | 1 | |

| # peptides with weight ≥ 0.1–0.5 | 51 | 20 | 4 |

VAR2CSA (IT4var04) is expressed by this laboratory parasite line (FCR3). PW201596 expresses VAR2CSA (JOSvar220191) and PW211251 expresses VAR2CSA (JOSvar219095_FR4_1991-4789).

To evaluate the error rate in detecting a known PfEMP1, VAR2CSA-IT4var04, with LAX we approached it in two ways. First, we analyzed the 17 unique peptide sequences identified by PEAKS and analyzed them with LAX. We used the expanded DB in which the IT4var04 sequence was removed. This DB still contained about 20 other variant forms of VAR2CSA and more than 1000 non-VAR2CSA PfEMP1s. Yet, the 17 peptides were assigned by LAX to VAR2CSA with a mean percent match (range) of 88% (65–96%). This analysis demonstrates that in the absence of the exact sequence, LAX still assigned the peptides to VAR2CSA, providing a correct identification of the PfEMP1 expressed by this parasite. Second, we implemented a protein-level FDR following LAX peptides assignment to proteins. In the current study, an FDR of <1% was applied at the peptide level to DB-matched spectra, and de novo peptides were filtered based on the ALC score described above. FDR for the assignment of proteins by LAX was applied using the target-decoy method by first generating a decoy database from the randomly shuffled real protein database (Human, P. Falciparum, VSA, novel PfEMP1 constructs and cRAP). Then every sample is analyzed with this target-decoy strategy generating target and decoy results from which the protein-level FDR is calculated. The protein-level FDR for VAR2CSA-IT4var04 is 0%.

We further evaluated this pipeline by analyzing IEs from two malaria-infected pregnant women. In the two isolates, the same PfEMP1s were identified using PEAKS and LAX (Table 1). Previous studies described VAR2CSA as the major PfEMP1 expressed by this parasite subpopulation.27 Similarly, to the results with FCR3, the differences in the total number of peptides in the two analyses are due to peptides with weights of <0.1. Protein-level FDRs for VAR2CSA expressed in pregnant women isolates were 3.2% for var in isolate PW201596 and 15% for isolate PW211251.

The expanded DB includes an additional 697 PfEMP1s from 27 clinical isolates with an unknown number of genomes, as malaria infections are commonly polyclonal. Having additional PfEMP1 sequences did not result in random PfEMP1 identification, as was demonstrated with FCR3. The analysis of FCR3 showed that when using the public DB, the PfEMP1 with most peptides is VAR2CSA, as expected. When using the expanded DB, peptides were still assigned to VAR2CSA, while unique peptides to the IT4var04 remained as such.

PFEMP1 in Children’s Clinical Isolates

After establishing the pipeline, 31 parasite isolates collected from children enrolled in a longitudinal study in Mali (Table S2) were analyzed. As defined by the WHO, 6 isolates were from children with severe malaria, and the remaining 25 samples were from cases classified as nonsevere malaria. The average age was 34.7 months (range 3.4–62.0), and the mean parasite density was 240, 709/μl (range 48 274–995 029). There were no differences in the age or parasite density between children with and without severe malaria.

The annotated peptides and de novo peptides resulting from the analysis with PEAKS were analyzed by LAX to find the best match among a set of protein sequences. Because peptides with weights between 0.1 and 0.5 can be assigned to more than one PfEMP1, PfEMP1s identified by peptides that were already included in other PfEMP1s with the higher total number of peptides were not included in further analysis. For example, 3 PfEMP1s (JOSvar216439_FR6_89-2848, JOSvar232481_FR5_1-2277, and PFCLINvar59) identified in isolate 210057_5Jul2014 with 6–7 peptides using LAX, including 2 unique peptides and 4–5 peptides with a weight of 0.25–0.5 indicating that these peptides were shared between 2 and 4 PfEMP1s in each of the PfEMP1s (Table S3). However, the PfEMP1 containing the nonunique peptides did not have any additional information and represents a redundancy that resulted from the presence of similar sequences in multiple genomes in the DB.

After analyzing 31 children’s isolates with LAX, the number of PfEMP1s identified at 20% FDR protein level was compared between public and expanded DBs as well as with the PEAKS software (Table 2). The number of PfEMP1s with unique peptides identified by PEAKS using the expanded DB is low with a third of the samples having no PfEMP1 identified with ≥3 peptides. Using LAX with the expanded DB, the number of PfEMP1s at 20% FDR with 3–4 and 5–9 peptides increased in 25 and 20 isolates, respectively. The proportion of isolates with PfEMP1s identified with 10 or more peptides was similar when public and expanded DBs were used. The complete list of PfEMP1s identified with LAX using the Expanded DB is shown in Table S4. Based on the results shown in Table 2, isolates are grouped into three categories: decrease, no change, and increase. A decrease in the number of PfEMP1s with the expanded DB is due to (1) the reduction of the peptide weight (<0.1), which is a result of the increased PfEMP1 sequences in the DB; (2) the assignment of peptides to a PfEMP1 with a higher percent match (Table S5). Although this may appear to be a loss of information, for the identification of unique PfEMP1s expressed by clinical parasites with high confidence, we maintained a stringent weight cutoff of 0.1. Isolates with no change in the number of PfEMP1s identified with the expanded DB versus the public DB suggest that the use of the latter may be sufficient to identify PfEMP1s in that isolate. An increase in the number of PfEMP1s shows that the added sequences in the extended DB are necessary to identify PfEMP1s in that isolate (Table S6).

Table 2.

Number of PfEMP1s Identified by PEAKS with Expanded DB, LAX with Expanded DB, and LAX with Public DB at 20% FDRa

| isolate ID | PEAKS-expanded DB |

LAX-expanded DB |

LAX public DB |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–4 unique peptides | 5–9 unique peptides | 10+ unique peptides | 3–4 peptides | 5–9 peptides | 10+ peptides | 3–4 peptides | 5–9 peptides | 10+ peptides | |

| 210057_5Jul2014 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 210737_15Aug2014 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 220039_19Aug2011 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 230055_19Oct2011 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 220202_22Jul2012 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| 210213_30Jun2014 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 210356_23Oct2014 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 210385_1Nov2014 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 210487_27Aug2013 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 210487_19Aug2014 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 210488_30Jul2013 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 210538_29Sep2014 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 211015_30Jul2013 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 211890_10Aug2015 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 212060_5Oct2015 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 220024_19Oct2012 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 220053_4Aug2014 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| 220166_17Sep2012 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 20 | 12 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 1 |

| 220170_19Sep2011 | 25 | 2 | 2 | 32 | 30 | 4 | 5 | 25 | 4 |

| 220202_13Aug2012 | 14 | 4 | 0 | 37 | 18 | 1 | 9 | 15 | 3 |

| 220254_26Sep2011 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 5 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 0 |

| 220258_11Jul2012 | 26 | 3 | 1 | 12 | 23 | 3 | 3 | 22 | 2 |

| 220258_26Aug2011 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 28 | 23 | 1 | 8 | 12 | 1 |

| 220286_11Jul2012 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 0 |

| 220306_9Sep2012 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| 220419_27Aug2014 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| 220528_22Aug2014 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 |

| 220538_2Nov2011 | 14 | 5 | 0 | 13 | 11 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| 230116_13Aug2011 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 230124_21Aug2012 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 0 |

| 230133_28Aug2012 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

PEAKS results are PfEMP1s identified with unique peptides. LAX results are PfEMP1s identified with peptides with a weight ≥ 0.1. A complete list of PfPEMP1s identified by LAX-Expanded DB is shown in Table S4.

The contribution of additional PfEMP1 sequences in the expanded DB is exemplified in three isolates that had an increased number of PfEMP1s that were confidently identified with more than 10 peptides. For example, isolate 220258_11Jul2012 has 2 additional PfEMP1s identified with 16 peptides. Previously, these 16 peptides were distributed among 10 different PfEMP1s in the public DB each with 3–10 peptides and with percent matches between 0.77 and 1. This demonstrates that with the expanded DB, one PfEMP1 was confidently identified with 16 peptides (Table 3).

Table 3.

Major PfEMP1, JOSVar266589_FR1_204-3234, Identified in Isolate 220258_11Jul2012a

| peptide | JOSVar266589 FR1_204-3234 weight | percent match | public DB Match 1 (percent match) | public DB match 2 (percent match) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R.NVFEYIAEIISNEVK.K | 0.33 | 1 | HB3var01 (0.88) | |

| R.IQLCDYNLEHINDSNINSTDDLLGNLLVMAK.S | 0.25 | 1 | HB3var01 (1) | |

| ALLDNLEKLM | 0.25 | 0.8 | PFB0935w (0.8) | |

| K.KNEIFMDLDCPR.C | 0.33 | 1 | IT4var02 (0.93) | |

| K.ITSVTDVAER.M | 0.33 | 1 | DD2var04 (0.92) | |

| R.FILPPLLRR | 0.33 | 1 | PFB0245c (0.45) | HUMAN_C12orf71(0.7) |

| K.LNVGDVTNNGNVNNK.F | 0.1667 | 1 | IGHvar07 (1) | |

| K.FLVQVLLSANK.Q | 0.1111 | 1 | IT4var14 (1) | |

| K.YNEPNGQIDNK.G | 1 | 1 | IT4var14 (0.77) | |

| K.GTDLWDQNKGENDTQR.K | 0.33 | 1 | DD2var04 (0.83) | |

| K.IKENIDDDEIKGK.Y | 0.33 | 1 | PFCLINvar49 (0.93) | |

| K.TTPHEDYIPQR.L | 0.1 | 1 | PFCLINvar05 (1) | |

| KNKNGVKPSNGRE | 0.33 | 1 | IGHvar32 (0.77) | |

| R.QKLCIYYFGNEAQIPIINSQDVLR.D | 0.25 | 1 | IGHvar32 (0.58) | |

| K.GVVNDSNGIIVK.D | 0.25 | 1 | IGHvar32 (0.86) | PFE1640w (0.86) |

| K.LLTRLMQVAATEGYNLGQYYK.N | 0.25 | 1 | DD2var25 (0.78) | HB3var1csa (0.78) |

| total # peptides | 16 | |||

| total weight | 4.9558 |

Shows peptides assigned to this PfEMP1, with weight = 1 or 0.5 and Percent Match = 1 when using the Expanded DB. All peptides except for the third are database matches. When using the Public DB, the peptide was matched to either Match 1 or 2 as shown in the table, percent matches for those matches are in parentheses.

A 20% FDR at the protein level was applied for the analysis of children isolates expressing PfEMP1 with higher sequence variation. At this cutoff, 40% of the proteins identified with 5–9 peptides and all proteins identified with ≥10 peptides were retained compared to results prior to protein-level FDR implementation (Table S7).

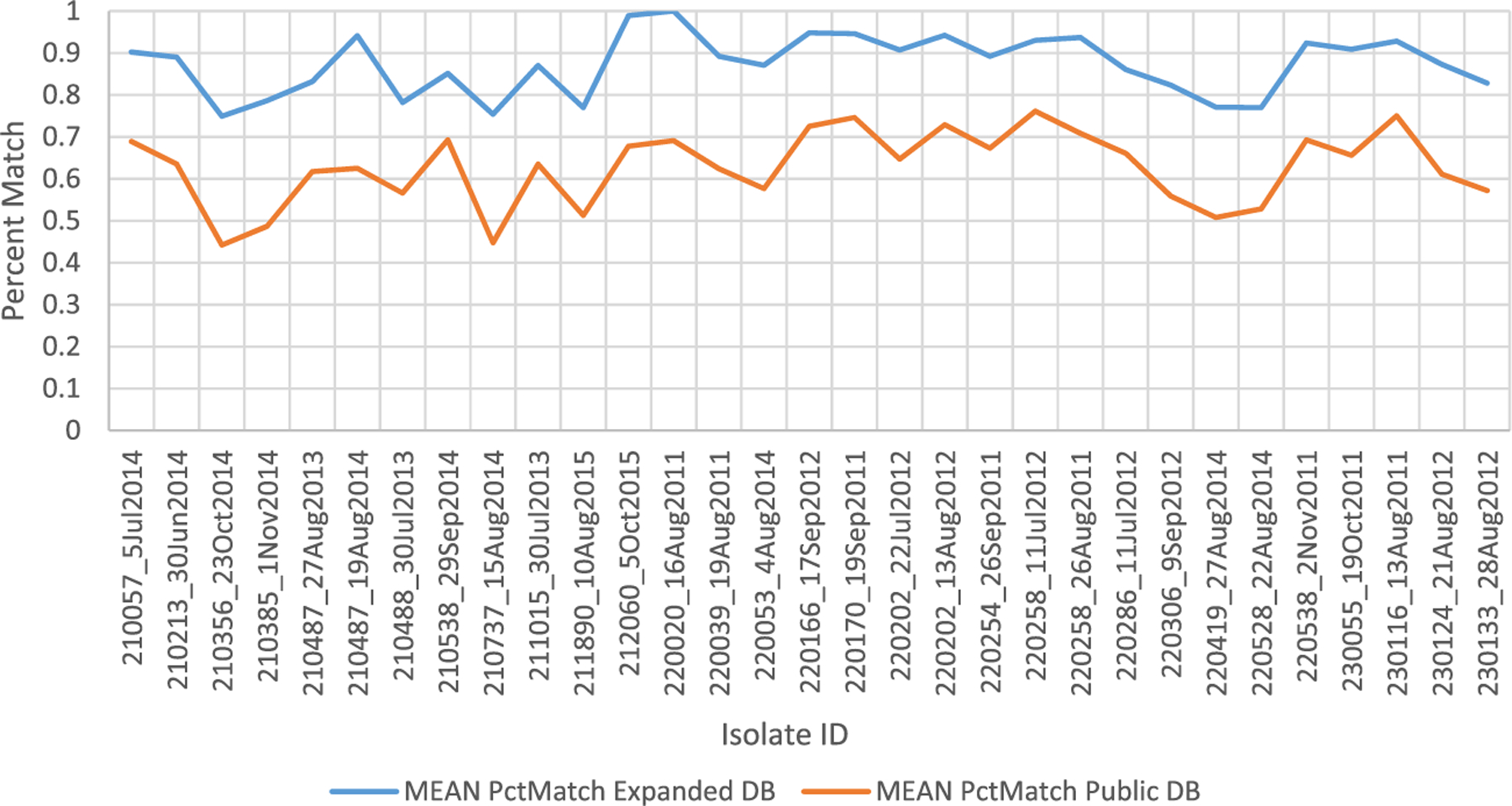

In addition to calculating the weight of a peptide matching to a protein, LAX also calculates the percent match of a peptide sequence to the database sequence, which is a numerical estimate of the number of amino acids that perfectly match. When using the expanded DB compared to the public DB, there is an increase of 24% in the percent match (Figure 3) across the samples. These results suggest that sequences derived from clinical isolates better match PfEMP1s expressed by other clinical isolates than PfEMP1s derived from laboratory-adapted parasite lines.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Mean Percent Match of PfEMP1. Unique Scans identified using Expanded DB versus Public DB for all 31 isolates.

PfEMP1 variants are encoded by approximately 60 var genes per haploid genome of P. falciparum and display extensive variation within and between genomes that include both amino acids substitutions and deletions/insertions, which pose a major challenge identifying PfEMP1s expressed by clinical isolates at the protein level. Although PfEMP1 expressed on IE surface plays a major role in the acquisition of immunity to malaria,9,28 there is a limited analysis of PfEMP1 repertoire in clinical isolates at the protein level. Our novel pipeline identified PfEMP1s in almost all samples compared to a commercial software like PEAKS. For the purpose of identifying a PfEMP1, a weight score of 0.1 was used to discriminate between common peptides and peptides shared between a few PfEMP1s that may be of greater interest in relating PfEMP1 expression with disease and protective immunity. An earlier study that related antibody response to a highly conserved and variant epitopes of PfEMP1 with protection from clinical malaria described that antibody levels to the conserved peptide were not associated with protection.29 The main goal of the current study is to identify members of the PfEMP1 variant antigens; therefore, a nonstringent FDR cutoff of 20% was implemented at the LAX protein identification level. Redundant PfEMP1s resulting from the presence of identical peptides corresponding to multiple PfEMP1s in the DB were removed from the final list maintaining PfEMP1s with the highest peptide counts. This approach provided a list of protein candidates expressed by clinical isolates. PfEMP1s are large proteins composed of unique and nonunique sequences, future functional and immunological studies of these proteins will further validate their expression in parasites collected from malaria-infected children.

CONCLUSIONS

In the present study, we described a new pipeline to analyze members of the variant gene family in P. falciparum, PfEMP1, at the protein level. Using a model parasite, our results demonstrated that the same PfEMP1 identified with expanded DB as public DB, thus the presence of additional sequences did not result in random PfEMP1 assignments. The implementation of the LAX algorithm for the peptide alignment together with expanded DB enabled identifying PfEMP1 expressed in clinical samples from children infected with P. falciparum. Although only 5 out of 31 clinical samples contributed sequences to the expanded DB, the total number of PfEMP1 proteins identified in 27 out of 31 samples increased suggesting that this pipeline works equally well on samples with and without RNA seq data. Because members of the PfEMP1 proteins have been associated with naturally acquired immunity to malaria, this new approach to identify PfEMP1 at the protein level in clinical samples will assist in identifying new targets for developing a malaria vaccine.

In addition, this pipeline can be implemented to study other variable protein families and we are currently expanding its usage to study antibody repertoire following vaccination.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank Yaselly V. Sanchez for completing the manual inspection of spectra and Alan Hoofring from NIH Medical Arts for illustrating Figure 1.

Funding

All funds were received from NIH DIR.

ABBREVIATIONS

- IE

infected erythrocyte

- CSA

chondroitin sulfate A

- PfEMP1

Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1

- DB

database

- SM

severe malaria

- FCR3

laboratory strain of P. falciparum

- LAX

LAX Local Peptide Assignment

- MS

mass spectrometry

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.9b00169.

Conserved PfEMP1 peptides (Table S1); clinical data of 31 parasite isolates (Table S2); PfEMP1 matrices for top 3 PfEMP1s identified in isolate 210057_5Jul2014 (Table S3); a complete list of PfEMP1s identified with LAX-Expanded DB at 20% FDR (Table S4); decrease in the number of PfEMP1s with 10–15 peptides (Table S5); increase in the number of PfEMP1s (Table S6); number of PfEMP1s identified without FDR implementation (Table S7) (PDF)

Protein–peptide results from PEAKS for 31 samples (XMSX)

Accession Codes

All sequencing datasets will be deposited to GenBank.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the PRIDE Archive (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/) via the PRIDE partner repository with the data set identifier PXD012958.

REFERENCES

- (1).Carneiro I; Roca-Feltrer A; Griffin JT; Smith L; Tanner M; Schellenberg JA; Greenwood B; Schellenberg D Age-patterns of malaria vary with severity, transmission intensity and seasonality in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and pooled analysis. PLoS One 2010, 5, No. e8988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Chan JA; Howell KB; Reiling L; Ataide R; Mackintosh CL; Fowkes FJ; Petter M; Chesson JM; Langer C; Warimwe GM; Duffy MF; Rogerson SJ; Bull PC; Cowman AF; Marsh K; Beeson JG Targets of antibodies against Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes in malaria immunity. J. Clin. Invest 2012, 122, 3227–3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Riganti M; Pongponratn E; Tegoshi T; Looareesuwan S; Punpoowong B; Aikawa M Human cerebral malaria in Thailand: a clinico-pathological correlation. Immunol. Lett 1990, 25, 199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Smith JD The role of PfEMP1 adhesion domain classification in Plasmodium falciparum pathogenesis research. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol 2014, 195, 82–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Cham GK; Turner L; Kurtis JD; Mutabingwa T; Fried M; Jensen AT; Lavstsen T; Hviid L; Duffy PE; Theander TG Hierarchical, domain type-specific acquisition of antibodies to Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 in Tanzanian children. Infect. Immun 2010, 78, 4653–4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Bull PC; Kortok M; Kai O; Ndungu F; Ross A; Lowe BS; Newbold CI; Marsh K Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes: agglutination by diverse Kenyan plasma is associated with severe disease and young host age. J. Infect. Dis 2000, 182, 252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Nielsen MA; Staalsoe T; Kurtzhals JA; Goka BQ; Dodoo D; Alifrangis M; Theander TG; Akanmori BD; Hviid L Plasmodium falciparum variant surface antigen expression varies between isolates causing severe and nonsevere malaria and is modified by acquired immunity. J. Immunol 2002, 168, 3444–3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Warimwe GM; Abdi AI; Muthui M; Fegan G; Musyoki JN; Marsh K; Bull PC Serological Conservation of Parasite-Infected Erythrocytes Predicts Plasmodium falciparum Erythrocyte Membrane Protein 1 Gene Expression but Not Severity of Childhood Malaria. Infect. Immun 2016, 84, 1331–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Bull PC; Abdi AI The role of PfEMP1 as targets of naturally acquired immunity to childhood malaria: prospects for a vaccine. Parasitology 2016, 143, 171–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Bertin GI; Sabbagh A; Guillonneau F; Jafari-Guemouri S; Ezinmegnon S; Federici C; Hounkpatin B; Fievet N; Deloron P Differential protein expression profiles between Plasmodium falciparum parasites isolated from subjects presenting with pregnancy-associated malaria and uncomplicated malaria in Benin. J. Infect. Dis 2013, 208, 1987–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Nesvizhskii AI Proteogenomics: concepts, applications and computational strategies. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 1114–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Sheynkman GM; Shortreed MR; Cesnik AJ; Smith LM Proteogenomics: Integrating Next-Generation Sequencing and Mass Spectrometry to Characterize Human Proteomic Variation. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem 2016, 9, 521–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lobas AA; Karpov DS; Kopylov AT; Solovyeva EM; Ivanov MV; Ilina IY; Lazarev VN; Kuznetsova KG; Ilgisonis EV; Zgoda VG; Gorshkov MV; Moshkovskii SA Exome-based proteogenomics of HEK-293 human cell line: Coding genomic variants identified at the level of shotgun proteome. Proteomics 2016, 16, 1980–1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Castellana NE; McCutcheon K; Pham VC; Harden K; Nguyen A; Young J; Adams C; Schroeder K; Arnott D; Bafna V; Grogan JL; Lill JR Resurrection of a clinical antibody: template proteogenomic de novo proteomic sequencing and reverse engineering of an anti-lymphotoxin-alpha antibody. Proteomics 2011, 11, 395–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Savidor A; Barzilay R; Elinger D; Yarden Y; Lindzen M; Gabashvili A; Adiv Tal O; Levin Y Database-independent Protein Sequencing (DiPS) Enables Full-length de Novo Protein and Antibody Sequence Determination. Mol. Cell Proteomics 2017, 16, 1151–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Fried M; Hixson KK; Anderson L; Ogata Y; Mutabingwa TK; Duffy PE The distinct proteome of placental malaria parasites. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol 2007, 155, 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ribeiro JM; Schwarz A; Francischetti IM; Deep A Insight Into the Sialotranscriptome of the Chagas Disease Vector, Panstrongylus megistus (Hemiptera: Heteroptera). J. Med. Entomol 2015, 52, 351–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Rask TS; Hansen DA; Theander TG; Gorm Pedersen A; Lavstsen T Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 diversity in seven genomes–divide and conquer. PLoS Comput. Biol 2010, 6, No. 933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Smith TF; Waterman MS Identification of common molecular subsequences. J. Mol. Biol 1981, 147, 195–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Blank-Landeshammer B; Kollipara L; Biss K; Pfenninger M; Malchow S; Shuvaev K; Zahedi RP; Sickmann A Combining De Novo Peptide Sequencing Algorithms, A Synergistic Approach to Boost Both Identifications and Confidence in Bottom-up Proteomics. J. Proteome Res 2017, 16, 3209–3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).The M; Tasnim A; Kall L How to talk about protein-level false discovery rates in shotgun proteomics. Proteomics 2016, 16, 2461–2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Reiter LC; Claassen M; Schrimpf S; Jovanovic M; Schmidt A; Buhmann J; Hengartner M; Aebersold R Protein Identification False Discovery Rates for Very Large Proteomics Data Sets Generated by Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2009, 8, No. 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Savitski MMW; Mathias S; Hahne H; Kuster B; Bantscheff M A Scalable Approach for Protein False Discovery Rate Estimation in Large Proteomic Data Sets. Mol. Cell. Proteom 2015, 14, 2394–2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Fried M; Duffy PE Adherence of Plasmodium falciparum to chondroitin sulfate A in the human placenta. Science 1996, 272, 1502–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Salanti A; Dahlback M; Turner L; Nielsen MA; Barfod L; Magistrado P; Jensen AT; Lavstsen T; Ofori MF; Marsh K; Hviid L; Theander TG Evidence for the involvement of VAR2CSA in pregnancy-associated malaria. J. Exp. Med 2004, 200, 1197–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Avril M; Kulasekara BR; Gose SO; Rowe C; Dahlback M; Duffy PE; Fried M; Salanti A; Misher L; Narum DL; Smith JD Evidence for globally shared, cross-reacting polymorphic epitopes in the pregnancy-associated malaria vaccine candidate VAR2CSA. Infect. Immun 2008, 76, 1791–1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Tuikue Ndam NG; Salanti A; Bertin G; Dahlback M; Fievet N; Turner L; Gaye A; Theander T; Deloron P High level of var2csa transcription by Plasmodium falciparum isolated from the placenta. J. Infect. Dis 2005, 192, 331–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Duffy MF; Noviyanti R; Tsuboi T; Feng ZP; Trianty L; Sebayang BF; Takashima E; Sumardy F; Lampah DA; Turner L; Lavstsen T; Fowkes FJ; Siba P; Rogerson SJ; Theander TG; Marfurt J; Price RN; Anstey NM; Brown GV; Papenfuss AT Differences in PfEMP1s recognized by antibodies from patients with uncomplicated or severe malaria. Malar.. J 2016, 15, No. 258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Dodoo D; Staalsoe T; Giha H; Kurtzhals JA; Akanmori BD; Koram K; Dunyo S; Nkrumah FK; Hviid L; Theander TG Antibodies to variant antigens on the surfaces of infected erythrocytes are associated with protection from malaria in Ghanaian children. Infect. Immun 2001, 69, 3713–3718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.