Abstract

Sino-nasal respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartomas (REAHs) are rare entity. They are benign tumors with excellent results after complete excision. We report a case of a 57-year-old male with a history of endoscopic surgery for right nasal polyps 20 years ago. The patient presented nasal obstruction that persisted for 10 years without anosmia nor epistaxis. Nasal endoscopy found a tissular mass filling the right nasal cavity extending to the nasopharynx. CT scan and MRI demonstrated soft tissue opacification of the right maxillary sinus and the homolateral anterior ethmoid cells with extension to the nasal cavity. The suspected diagnosis on imaging was an Inverted papilloma with a wide implantation base on the posterior part of the nasal septum. No endocranial or orbital extension was noted. The patient underwent endoscopic sinus surgery with complete extirpation of the tumor and a right ethmoidectomy. Histopathological assessment showed features consistent with REAH. No recurrence was noted at 1 year follow-up.

Keywords: Respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma, sinonasal mass, polyps, neoplasms, rare tumors

Introduction

Hamartomas are a tumor like malformation made up of abnormal mixture of normal tissue and cells from the region in which it grows. They are ubiquitous. Sinonasal epithelial hamartomas are rare. They present various subtypes including respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma (REAH) which is discussed in this paper. REAH was first described in 1995 by Wenig and was included in the OMS classification in 2005. It is a histopathological entity defined as a glandular proliferation of the ciliated respiratory epithelium which invaginate into the submucosa. The glands are surrounded by a thickened eosinophilic basement membrane. 1

The diagnosis of REAH is confirmed by histopathological assessment. Its clinical and radiological presentation is not specific and may mimic an inverted papilloma or adenocarcinoma or olfactory neuroblastoma. 2 Clinicians nowadays are more aware of this entity and pre surgical diagnosis may be discussed especially with better knowledge of certain features. Being well aware of this entity can either prevent overly aggressive resection or, conversely, incomplete resection. Complete endoscopic resection of REAH is the standard treatment guaranteeing very rare recurrence.

The aim of this study is to describe the clinical and radiological characteristics suggestive of REAH diagnosis.

Case report

We report the case of a 57-year-old male with a history of endoscopic surgery for right nasal polyps 20 years ago. The patient presented to our practice with progressive chronic nasal obstruction that persisted for 10 years without anosmia nor epistaxis. Nasal endoscopy found a tissular mass filling the right nasal cavity arriving to the nasopharynx. No cervical lymph nodes were found. Ophthalmic examination was normal. CT scan demonstrated total opacification of the right maxillary sinus and the homolateral anterior ethmoid cells with extension to the nasal cavity, the nasopharynx posteriorly and the homolateral nostril anteriorly (Figure 1). Right maxillary ostium was enlarged. The left maxillary sinus, was also totally opacified, with extension to the nasal cavity through the maxillary ostium that was enlarged. A small left fronto-ethmoidal osteoma of 1 cm was found (Figure 1). The maxillary sinus walls bilaterally were sclerotic demonstrating the chronicity of the inflammation. No bone lysis was found. MRI was performed showing hypointensity on T2 weighted image (WI) and T1 WI of the right maxillary sinus, ethmoid cells and homolateral nasal cavity with a convoluted cerebriform pattern. An heterogenous enhancement on contrast-enhanced T1 WI was found (Figure 2). The suspected diagnosis was an Inverted papilloma with a wide implantation base on the posterior part of the nasal septum. No endocranial or orbital extension was noted. Left maxillary sinusitis with signal voids on T2 WI was also found.

Figure 1.

Axial planes of CT scan demonstrating total opacification of both maxillary sinuses and the nasal cavity (A) with extension to the nasopharynx posteriorly (B) and to the right ethmoid (C) and right olfactory cleft (D) superiorly. Left fronto-ethmoidal osteoma was also noted (C).

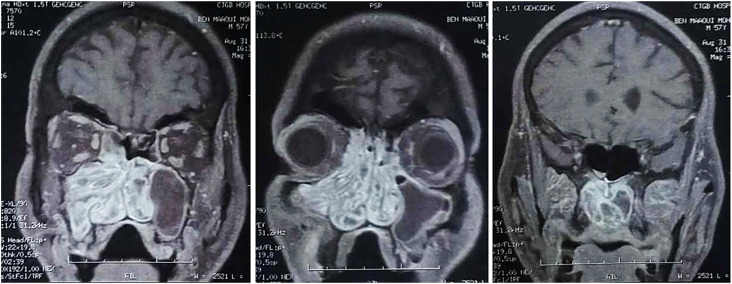

Figure 2.

Coronal planes of contrast-enhanced T1WI MRI showing a convoluted cerebriform aspect of the nasal cavity, the right maxillary sinus, the ethmoid and the nasopharynx.

A per-nasal mass biopsy was performed in the clinic under local anesthesia, and histological analysis revealed acute ulcerated inflammatory reshaping with metaplasia and epithelial regeneration.

The patient underwent endonasal surgery. Per operatively, a tissular polypoid tumor filling the right nasal cavity was found as well as, translucid polyps coming from the maxillary ostia and extending to the nasopharynx and the anterior ethmoidal cells. A complete excision of the tumor and the polyps was performed as well as, a right ethmoidectomy. Left middle meatotomy was also performed. The osteoma was respected in absence of complications and considering its size. The conclusive histology report indicated features consistent with Respiratory Epithelial Adenomatoid Hamartoma (Figure 3). No recurrence was noted at 1 year follow-up.

Figure 3.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) ×20 magnification showed a proliferation of invaginated benign glands (yellow arrows). (B) Glands varied in size from small to large with a dilated appearance (HE ×40 magnification) (red arrows). (C) The stroma surrounding glands was edematous and contained a mixed inflammatory infiltrate (HE ×100 magnification) (green arrows). (D) Glands were lined with ciliated columnar epithelium (HE ×400 magnification) (white arrow).

Discussion

REAH pathogenesis is not yet clear. REAH was classified as hamartomas based on morphological criteria. The precise mechanisms underlying the onset of REAH remain unknown, and its nature as a benign tumor, hamartoma, or reactive inflammatory process remains a topic of ongoing debate. REAH can be represented in two forms: as an isolated lesion (less frequent) or in association with an inflammatory process (especially nasal polyposis).3,4

Joseph S. Schertzer and al suggested that associated REAH may be developed from a chronically inflamed mucosa. The factors that support this theory are the association to a proinflammatory environment. REAH was discovered incidentally in 31.4% of patients treated for associated inflammatory rhinosinusal disease. 5 Vira found on a period of 11 years, 51 incidental REAH on final pathology of patients operated for chronic rhinosinusitis. 3 REAH was associated to allergic rhinitis in 73% of cases and to concurrent sinonasal inflammatory disorders in 69.2% of cases. 6 Associated REAH were more associated with asthma (78 % vs 22.2 % for isolated REAH). 6 Another identified factor supporting this theory, was anterior endoscopic sinus surgery. This may be due to the initial sinus pathology (chronic sinusitis) but also to the anatomic changes resulting from the surgery. The deterioration of the mucosa would induce a reactive inflammatory process. 6 Our patient underwent endoscopic sinus surgery 20 years before developing REAH demonstrating the chronicity of the process.

Molecular analysis of REAH suggests that it may be a benign neoplasm. John Ozolek found that the loss of heterozygosity was infrequent in chronic sinusitis but was in increasing frequency in REAH and sinonasal adenocarcinoma (SNAC) with a fractional allelic loss of 2%, 31% and 64% respectively. 7 Loss of heterozygosity for REAH was found at more than 1 locus (30% of REAHs) but the most concerned gene locus included 18q21.2. 7 Moreover, REAH revealed some similarities to SNAC in its mutational profile. 7

Male predominance was noted.3,5,8 REAH has been reported in patients from the third to ninth decade of life, with predominance in the fifth decade.1,3,4,8 The most frequent symptoms were nonspecific to REAH and comprised nasal obstruction, congestion, hyposmia, headaches, facial pain, rhinorrhea, and postnasal drip.3,5,9

Hawley found no statistical difference in age, gender, or smoking history between isolated REAH and NP-associated REAH. 9 However, patients with associated REAH presented more frequently with nasal obstruction and had longer duration of symptoms before diagnosis. 9 All symptoms other than epistaxis were more frequently found with associated REAH. 9

Endoscopic examination usually reveals nasal fleshy mass with a polypoid aspect.4,5 In that case endoscopic biopsy may reveal the diagnosis. 5 However, REAH is mostly found incidentally on final histopathology examination of patients operated on for chronic rhinosinusitis whose nasal endoscopy usually reveals unilateral or bilateral polyps.3,5,9,10

Unilaterality was predominant in most series (62.7% unilateral vs 37.3% bilateral). 5 However, the biopsy of contralateral olfactory cleft (OC) of patients having unilateral polyps revealed the presence of REAH. 10

For isolated REAH, The OC was the predominant primer location in most cases (56.2% for Jivianne, 75% for Hawley)5,9 Other locations were the posterior nasal septum, the middle turbinate, the inferior turbinate and the sphenoid face.3,5,9

For associated REAH, identifying the exact primer site is difficult due to the concurrent pathology. 5 Most of these cases are treated with functional endoscopic sinus surgery and commonly we do not specify the exact site of the specimens for pathology examination. Lorentz noted an increase in the frequency of the association of REAH of the OC with nasal polyposis (48%) with separating specimens of the OC from other locations. 10 Conversely, Vira found on a serie of 54 patients operated on for chronic rhinosinusitis, that the predominant site of incidental REAH was the sinuses and not the nasal cavity. 3

REAH was mainly associated to chronic rhinosinusitis with sinonasal polyps (57.1% for Jivianne, 79% for Hawley, 19.5% for Vira and 23% for Joseph).3,5,6,9 Chronic rhinosinusitis without sinonasal polyps, fungal rhinosinusitis, central compartment atopic disease and IgG4-related sclerosing disease were also noted.3,5,6

Other associations have been described with a malignant process (squamous cell carcinoma (1), low-grade intestinal type adenocarcinoma (1), and adenoid cystic carcinoma (1)), as well as other non-malignant conditions such as inverted papilloma (2), adenoiditis (1) and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (1). 9

On CT scan REAH is presented as a well limited opacity that can mimic a benign or malignant pathology. However, the widening of the olfactory cleft in axial and coronal planes, without bone lysis of the cribriform plate, nasal septum, conchal lamina, and turbinate wall of the ethmoidal labyrinth should increase suspicion of REAH. 4 REAH has a mean maximum olfactory cleft width of 8.6 and 9.4 mm in the coronal and axial planes, respectively. 5 Comparative analysis of isolated versus associated REAH showed no statistically significant differences between the two groups in either the coronal or the axial planes in maximum olfactory cleft width and maximum olfactory cleft/total nasal width ratios. 5

For isolated REAH, there is usually opacity of the olfactory cleft that is enlarged without the involvement of the sinuses.4,10 Sometimes REAH induces secretion retention and the sinuses appear more or less opacified. These opacities should disappear after a short systemic corticosteroid treatment. 10

For NP-associated REAH, there is an opacified and enlarged olfactory cleft associated to bilateral opacification of the ethmoidal labyrinths. 4

Identified MRI findings are not specific for REAH but may be useful to eliminate differential diagnosis as inverted papilloma, malignant tumor or meningoencephalocele. 4 MRI allows to distinguish liquid retention from a tissue opacity of the sinuses.

Conclusion

REAH is a rare pathology reported in single cases or small series in the literature. It is a slowly progressive benign lesion. Its diagnosis is suspected especially with the presence of a polypoid mass of the OC, or of the posterior nasal septum. It may be associated to rhinosinus inflammation or polyposis. The diagnosis is reinforced with the presence of an enlarged OC on the CT scan, if present, and the absence of signs of aggressivity. Being aware of this entity allows adequate treatment with excellent results.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Safa Nefzaoui: Conception and design, Acquisition of the data, Analysis and interpretation of the data, Drafting of the article. Imen Zoghlami: Conception and design, Acquisition of the data, Analysis and interpretation of the data, Drafting of the article. Jihene Gharsalli: Conception and design, Acquisition of the data, Analysis and interpretation of the data, Drafting of the article. Emna Sabehi: Conception and design, Acquisition of the data, Analysis and interpretation of the data, Drafting of the article. Nadia Romdhane: Conception and design, Acquisition of the data, Analysis and interpretation of the data, critical revision. Imen Helal: Acquisition of the data, Analysis and interpretation of the data, Drafting of the article. Dorra Chiboub: Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the article. Ines Hariga: Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the article. Chiraz Mbarek: Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the article.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval

This research was approved by the local medical ethics committee and aligned to the Helsinki ethical principles

Informed consent

The patient agreed to participate after given an informed consent

ORCID iD

Jihene Gharsalli https://orcid.org/0009-0008-8733-9707

References

- 1.Wenig BM, Heffner CDK. Respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartomas of the sinonasal tract and nasopharynx: a clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1995; 104: 639–645. DOI: 10.1177/000348949510400809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin Y-W, Lai K-J, Shen K-H. A case report of adolescent respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma. Ear Nose Throat J 2022; 9: 014556132211019 DOI: 10.1177/01455613221101936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vira D, Bhuta S, Wang MB. Respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartomas. Laryngoscope 2011; 121: 2706–2709. DOI: 10.1002/lary.22399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen DT, Gauchotte G, Arous F, et al. Respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma of the nose: an updated review. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2014; 28: e187–e192. DOI: 10.2500/ajra.2014.28.4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JT, Garg R, Brunworth J, et al. Sinonasal respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartomas: series of 51 cases and literature review. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2013; 27: 322–328. DOI: 10.2500/ajra.2013.27.3905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schertzer JS, Levy JM, Wise SK, et al. Is respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma related to central compartment atopic disease? Am J Rhinol Allergy 2020; 34: 610–617. DOI: 10.1177/1945892420914212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozolek JA, Hunt JL. Tumor suppressor gene alterations in respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma (REAH): comparison to sinonasal adenocarcinoma and inflamed sinonasal mucosa. Am J Surg Pathol 2006; 30: 1576–1580. DOI: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213344.55605.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rom D, Lee M, Chandraratnam E, et al. Respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma: an important differential of sinonasal masses. Cureus 2018; 10: e2495. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawley KA, Pabon S, Hoschar AP, et al. The presentation and clinical significance of sinonasal respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma (REAH): sinonasal REAH. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2013; 3: 248–253. DOI: 10.1002/alr.21083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lorentz C, Marie B, Vignaud JM, et al. Respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartomas of the olfactory clefts. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol 2012; 269: 847–852. DOI: 10.1007/s00405-011-1713-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]