Abstract

Transected peripheral nerve injury (PNI) affects the quality of life of patients, which leads to socioeconomic burden. Despite the existence of autografts and commercially available nerve guidance conduits (NGCs), the complexity of peripheral nerve regeneration requires further research in bioengineered NGCs to improve surgical outcomes. In this work, we introduce multidomain peptide (MDP) hydrogels, as intraluminal fillers, into electrospun poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) conduits to bridge 10 mm rat sciatic nerve defects. The efficacy of treatment groups was evaluated by electromyography and gait analysis to determine their electrical and motor recovery. We then studied the samples’ histomorphometry with immunofluorescence staining and automatic axon counting/measurement software. Comparison with negative control group shows that PCL conduits filled with an anionic MDP may improve functional recovery 16 weeks postoperation, displaying higher amplitude of compound muscle action potential, greater gastrocnemius muscle weight retention, and earlier occurrence of flexion contracture. In contrast, PCL conduits filled with a cationic MDP showed the least degree of myelination and poor functional recovery. This phenomenon may be attributed to MDPs’ difference in degradation time. Electrospun PCL conduits filled with an anionic MDP may become an attractive tissue engineering strategy for treating transected PNI when supplemented with other bioactive modifications.

Keywords: self-assembly, peptide, nerve guidance conduit, sciatic nerve transection, peripheral nerve regeneration, electromyography

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

With motor vehicle accidents, unintended lacerations, and gun violence as the most common causes, transected peripheral nerve injury (PNI) may impact the sensory and motor functions of patients, lowering their quality of life.1,2 In the United States, approximately 5% of patients admitted to level I trauma centers suffer from PNI.2 PNI accounts for more than 8.5 million restricted activity days and 5 million bed/disability days annually, inflicting an estimated $150 billion socioeconomic damage.3 Treatments for PNI have long focused on development of nerve guidance conduits (NGCs), dating back to 1880 with the creation of nerve conduits from decalcified bones.4 The current gold standard treatment of PNI is to bridge gap defects with autografts–secondary nerve segments extracted from the same patients. However, this approach has multiple limitations including impaired sensation in secondary surgical sites, autografts’ size mismatch to nerve defects, and painful neuroma formations.5–7 Although there are several FDA-approved NGCs as clinical alternatives to autografts, most of them are hollow and have limited efficacy in regenerating nerve gaps greater than 30 mm.5,8 One such clinically approved NGC is Neurolac, a poly(d,l-lactide-ε-caprolactone) synthetic conduit manufactured by dipcoating.5,9 In a 20-week rat sciatic nerve study, Neurolac showed no significant difference from the autograft in a motor recovery and in the number of myelinated axons.10 But excessive swelling of Neurolac was reported in another study, resulting in lumen blockage and consequently poor nerve recovery.9 As FDA-approved NGCs of biological origin, Axoguard nerve connectors and AxoGen Avance contain decellularized extracellular matrix (ECM) that aids axonal growth by providing structural support and growth factors.11,12 However, due to their xenogeneic and allogeneic origins, the decellularized conduits are susceptible to batch-to-batch variations, potential inflammatory response, high price, and limited supply. Hence, bioengineered, artificial NGCs are highly sought-after to improve upon these challenges.

NGCs have been engineered with surface modifications,13–17 growth factors,18–22 cell encapsulation,23–26 and internal architecture design27–35 to enhance the rate of peripheral nerve regeneration. With regards to NGCs’ intraluminal structures, they consist of solid multichannels,27,28 microporous matrices,29–32 and nanofibrous hydrogels33–38 that promote cellular adhesion and directional guidance. For example, collagen conduits with inner multichannels showed various degrees of nerve regeneration, with 7-channel conduit group performing worse than 2- and 4-channel groups in electrophysiology.28 The presence of solid structures may act as an impenetrable barrier that reduces the cross-sectional areas for axonal outgrowth. Microporous matrices, on the other hand, introduce complex patterns that maximize the available area without sacrificing directional alignment for nerve regeneration.31,32 Nanofibrous hydrogels are of interest because they have material stiffness suitable for neurite adhesion and elongation.39 Because of their large water content and resemblance to ECM, nanofibrous hydrogels recapitulate much of the native microenvironment of nerve tissue.40 In one study, agarose hydrogels, when mixed with interleukins and fractalkine, recruited macrophages with M2 pro-regenerative phenotypes in 15 mm defect size PNIs and led to higher myelinated axon density and myelin thickness after 14 weeks.34 These examples demonstrate the potential use of nanofibrous hydrogels in clinical trials to treat patients with transected PNI.

Self-assembling peptide (SAP) hydrogels belong to a family of biomaterials that depend on noncovalent interactions to form nanofibrous hydrogels.41 RADA-16 and peptide amphiphiles (PAs) are two main SAP hydrogels that have been studied for treating transected PNI in animal models.42,43 Containing functional motifs (RGD and IKVAV) in their amino acid sequences, RADA-16 hydrogels were filled in electrospun poly(l-lactic acid) conduits to connect a 5 mm sciatic nerve gap.42 No statistical difference in nerve histomorphometry, muscle weight, and functional recovery was found between the RADA-16 group and the saline control group. PA hydrogels in poly(lactide-co-glycolide acid) conduits promoted nerve regeneration of a 10 mm defect, with an improved walking track score at 4 weeks and Schwann cell density at 16 weeks.43 However, no data in this sciatic nerve study suggest accelerated electrical recovery from PA treatment.

In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of multidomain peptide (MDP) hydrogels in restoring the motor and electrical function of rats after surgically transected PNI. MDPs are SAPs that contain an alternating sequence of hydrophobic and hydrophilic amino acid residues, with charged amino acids flanking the termini.44,45 When MDPs are dissolved in water with multivalent salts, the side chains of the hydrophilic residues face outward, and those of the hydrophobic residues face inward, leading to the formation of antiparallel beta-sheets and their self-assembly into nanofibers.44,45 Because of their bioactivities and interactions with surrounding tissues, MDP hydrogels have many potential biomedical applications including angiogenesis,46,47 wound healing,48 cancer therapy,49,50 and nerve regeneration.51 Previously, we demonstrated that cationic MDPs, K2(SL)6K2 and its derivatives, outperformed the HBSS control group in treating nerve crush injuries, with statistically higher sciatic functional index and myelination percentages after 15 days.51 Such results were proposed to be caused by higher macrophage recruitment at day 3 in cationic MDP groups. Here, we hypothesize that MDPs and nerve guidance conduits (NGCs) could facilitate the recovery of transected PNI by providing ECM-like structural support and directional guidance.

Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) was selected for this study because of its ease of handling and biocompatibility for in vivo implantation.5,52 The degradation time of PCL surpasses our longest sacrificial time point,53 allowing MDPs to remain within the NGCs without the risk of premature dissipation. This characteristic also facilitates locating the positions of nerve defects for processing cross-sections. The sheer number of rats in this study requires a fabrication method that is scalable and consistent; therefore, electrospinning was employed to produce the NGCs. Electrospun PCL forms a network of microfibers, making the NGCs porous and resistant to crack propagation.54 These properties are crucial for nutrients/oxygen diffusion and surgical manipulation, fulfilling the requirements of an ideal NGC.55–57

In the literature, peripheral nerve regeneration is commonly modeled with the sciatic nerve due to its large size and mixed motor and sensory functions. Crush injury model involves damaging the structure of axons but leaving surrounding structures relatively intact.58 Our previous study demonstrates enhanced nerve regeneration after crush injury,51 which encouraged us to test MDPs in a more severe form of injury: transected nerve model. The recovery of such injury is challenging because axons cannot attach to the missing basal lamina, which is supposed to provide physical and directional guidance.59 For this, 10 mm is considered to be a critical size gap in rat transected nerve models according to a meta-analysis paper that compares the surgical outcome of autografts with different lengths.60 In 167 articles, significant difference in sciatic functional index was found between autograft groups with ≤10 mm and >10 mm nerve defect.60

On the basis of these considerations, we followed the experimental plan illustrated in Figure 1. The Sprague–Dawley rats were divided into 3 groups that were sacrificed at 3-, 6-, and 16-week time points. At day 0, we performed gluteus split on anesthetized rats and exposed the sciatic nerves. Ten millimeter nerve segments were removed using surgical scissors and rulers. For reverse autograft groups, we sutured the extracted nerve segments backward to connect the gaps. For MDPs and HBSS groups, we filled electrospun poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) conduits with blinded hydrogel samples and bridged the sciatic nerve defects. This procedure was followed by a secondary sample injection until visible overflowing to replace any hydrogel loss in surgical manipulation. For sham groups, the surgical sites were closed immediately after the sciatic nerves were exposed. For negative control groups, the nerve defects were created as above but left untreated. We monitored the motor recovery of 42 rats over 16 weeks and performed gait analysis every 2 weeks. To observe short-term changes in nerve morphology, we acquired longitudinal sections of nerve tissues at the 3-week time point to measure axonal outgrowths from proximal ends. Before euthanasia at 6 and 16 weeks, gastrocnemius muscle electromyography was performed by stimulating the region proximal to the nerve defect and recording the compound muscle action potentials to evaluate electrical conduction and the degree of reinnervation. Afterward, we assessed the weights of gastrocnemius muscles and the histomorphometry of regenerated peripheral nerves to determine mid- and long-term structural recoveries.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating the overall experimental design. (a) This blinded study includes the autograft, MDP hydrogel, and HBSS treatment groups that are sacrificed at 3-, 6-, and 16-week post operation. (b) Surgical procedure involves exposing sciatic nerves and introducing 10 mm long defects. Prefilled with hydrogels/HBSS, the PCL conduits bridge the nerve gaps. Secondary injection is then performed to replace hydrogels/HBSS lost during the surgery. (c) Two forms of gait analyses, along with the observation of flexion contractures, are done over 16 weeks to assess motor recovery. As the rats reach sacrificial time points, (d) CMAP signals are recorded at the gastrocnemius muscles, followed by (e) immunofluorescence staining of nerve tissues and the weight measurements of gastrocnemius muscles to evaluate electrical and structural recovery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Peptide Synthesis.

Peptides with amino acid sequence K2(SL)6K2 and D2(SL)6D2GIKVAV were manually synthesized using the solid-phase peptide synthesis, as described in previous publications.51 D2(SL)6D2 was synthesized using a Focus XC Automated Peptide Synthesizer (AAPPTec). In brief, respective FMOC-protected amino acids (Novabiochem) were sequentially coupled on low-loading rink amide MBHA resins (0.33–0.37 mmol/g, EMD Millipore) through piperidine (Cat. 104094, Sigma-Aldrich) deprotection and HATU (Cat. 31006, P3bioSystems) activation cycles. N-Termini of each peptide were acetylated with acetic anhydride (Cat. A10–500, Fisher Scientific) in N,N-dimethyl-formamide (Cat. D119–4, Fisher Scientific) before 90% v/v trifluoroacetic acid (Cat. T6508, Sigma-Aldrich) cleavage with 2.5% v/v triisopropylsilane (Cat. 233781, Sigma-Aldrich), 2.5% v/v anisole (Cat. 123226, Sigma-Aldrich), 2.5% v/v Milli-Q water, and 2.5% v/v 1,2-ethanedithiol (AC117852500, Fisher Scientific). The peptides were then triturated in cold diethyl ether (Cat. E138–4, Fisher Scientific). Resulting crude peptides were dissolved in Milli-Q water, dialyzed for 5 days in 100–500 Da MWCO dialysis tubing (Spectra/Por, Spectrum Laboratories Inc. Rancho Dominguez), and pH-adjusted to 7.4 by adding sodium hydroxide. After sterile filtration with a 0.2-μm polystyrene filter (Cat. 28145–477, VWR), the peptide solutions were lyophilized and stored at −20 °C. Mass spectrometry (Autoflex MALDI-TOF MS Sp, Bruker Instruments, Billerica, MA) was performed to confirm peptide mass (Figure S1).

Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy.

The 0.8 wt % peptide solutions were dissolved in 298 mM sucrose in Milli-Q water and mixed with Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) or Milli-Q water at a 1:1 ratio to reach a final peptide concentration of 0.4 wt %. CD spectra were obtained using a CD Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Inc. Easton, MD) after placing solutions in 0.1 and 0.01 mm quartz cuvette at room temperature. The wavelength range was set from 180 to 250 nm with a 50 nm/min scanning speed and a 0.1 nm data pitch. The CD data was averaged over 5 scans and presented in terms of molar residue ellipticity.

Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy.

Powdered peptide samples were placed on a Golden Gate diamond window of an ATR stage and pressed down using a pressure tower. The IR spectra were collected under nitrogen flow using a Nicolet iS20 FT/IR spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) at 4 cm−1 resolution and with 32 scans accumulation. The contribution of water was corrected from IR spectra by purging the chamber with nitrogen flow for 1 h, then collecting a background run prior to data acquisition. OMNIC spectroscopy software was used for background correction and data processing.

Peptide Hydrogelation.

Peptides were weighed and dissolved in 298 mM sucrose/Milli-Q water to make a 20 mg/mL (2 wt %) solution. Peptide solutions were mixed with 1X HBSS supplemented with 22.5 mM magnesium chloride (Cat. M8266, Sigma-Aldrich) at a 1:1 ratio to form 10 mg/mL (1 wt %) hydrogels. The hydrogels were then used in scanning electron microscopy, oscillatory rheology, and in vivo studies.

Scanning Electron Microscopy.

Peptide hydrogels were sequentially submerged in ascending concentrations of ethanol solutions to dehydrate the samples. The samples were critically dried using an EMS 850 critical point dryer (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). Remaining samples were then fragmented, placed on a conductive carbon taped pucks, and coated with a 4 nm gold layer using a Denton desk V Sputter system (Denton Vacuum, Moorestown, NJ). A JEOL 6500 Scanning Electron Microscope (JEOL Inc., Peabody, MA) was used for imaging.

Oscillatory Rheology.

Rheological properties of peptide hydrogels were examined using an AR-G2 rheometer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE). The 200 μL peptide hydrogel samples were placed within BD 3 mL plastic syringes (Cat. 10129–656, VWR) overnight to form gel pucks. The pucks were transferred to the rheometer and pressed between a metallic platform and a 12 mm stainless-steel parallel plate with a 1 mm gap. Strain sweep and frequency sweep tests were performed from 0.01 to 200% strain and from 0.1 to 100 rad/s frequency, followed by a shear recovery test. The hydrogel was subjected to 200% strain for 1 min before measuring the storage and loss moduli at 1% strain. Thirty minute time sweeps were programmed in-between the tests to equilibrate the hydrogels.

Construction of Electrospun Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) Conduits.

Fifteen wt % polycaprolactone (PCL) (Cat. 440744, Sigma-Aldrich), dissolved in 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (TFE) (Cat. T63002, Sigma-Aldrich), was prepared for electrospinning. The polymer solution was loaded into a BD 10 mL plastic syringe (Cat. 75846–756, VWR), which was connected to a 12-in.-long PTFE tubing (Cat. 90616, Hamilton) and a 16-guage blunt tip dispensing needle (Cat. 901–16–150, CML Supply). The syringe was then placed onto the syringe pump (flow rate = 5 mL/h) in the Yflow professional electrospinning lab device V2.0 (Yflow). The dispensing needle was located 13 cm above a 1.6 mm diameter rotating mandrel (Cat. 7131, K&S Precision Metals), with a rotational speed of 200 rotations/min. The voltages of the needle and the mandrel were 9 kV and −2 kV, respectively. With the air fan on, the needle moved back and forth (velocity = 8 mm/s) and ejected PCL microfibers were collected on the mandrel for 15 min. The resulting PCL tubes were cut into 14 mm-long conduits, soaked in ethanol for 2 days, and soaked in HBSS for another 2 days to remove TFE. The conduits were dried and sterilized with ethylene oxide gas for 24 h before material testing or in vivo use.

Suture Retention Test for PCL Conduits.

A Bose Electroforce 3200 Series III mechanical tester was used to measure the suture retention strength and ultimate tensile strain of PCL conduits. The conduits moist with HBSS were anchored to the bottom clamp, and a 5–0 suture knot (cat. J303H, Ethicon) was tied 2.5 mm from each edge. The distance between the knot and the bottom clamp (dl) was measured. As the suture attached to the top clamp, the bottom clamp traveled downward at a rate of 1 mm/s until the knot left the conduits. In the resulting stress–strain curve, the suture retention strength is defined as the maximum strength (gram-force), and the ultimate tensile strain (distance traveled/dl × 100%) is identified when the suture knot fails to hold the conduits.

In Vivo Rat Sciatic Nerve Transection Model.

All experimental procedures were approved by the Rice University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and performed according to the Animal Welfare Act and NIH guidelines for the care and use of animals. One-hundred fifteen female Sprague–Dawley SASCO rats (6 to 8 weeks) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). The identities of the peptide hydrogels and HBSS were blinded to the experimentalist. Rats first underwent 2% isoflurane anesthetization within an induction chamber. The animals were transferred to a nose cone and confirmed unconscious via foot pinch test. They were injected with 2 mg/kg Meloxicam (Cat. 21294589, Pivetal Alloxate) and 0.65 mg/kg Ethiqa XR extended-release buprenorphine (Fidelis Pharmaceuticals, North Brunswick, NJ) to reduce postsurgical inflammation and pain. Fur from the lower back was removed, and the region was sterilized with 70% isopropyl alcohol swabs and betadine solutions. A ~4–5 cm subcutaneous incision was made along the right femur to locate the gluteus maximus and biceps femoris, and the sciatic nerve was exposed via a gluteus split. A 10 mm section of the sciatic nerve was removed using surgical scissors. For experimental treatments, a PCL conduit prefilled with peptide hydrogel was used to bridge the gap by suturing 2 mm nerve segments into both proximal and distal ends of the conduit with an 8–0 polyglycolic acid suture (Cat. #XXS-G812S6D, AD Surgical). The conduit was refilled with hydrogel using a 29G insulin syringe (Cat. E61452800 ML, medonthego.com) to replace any hydrogel lost during manipulation and ensure completely filled conduits. For the reverse autograft group, the extracted nerve was used to bridge the gap in reverse and sutured into place with the 8–0 suture. The muscles and skins were closed with a 5–0 Vicryl suture (Cat. J303H, Ethicon). The rats were dosed with Meloxicam for two additional days and monitored with free access to food and water. At 3-, 6-, and 16-week time points, the rats were euthanized by carbon dioxide asphyxiation and thoracotomy after isoflurane anesthetization in an induction chamber. The nerves were extracted for sample processing.

Static Sciatic Index Measurement and Gait Analysis.

Prior to the surgery and every 2 weeks afterward until the 16-week end point, the motor functions were evaluated using static sciatic index measurement and gait analysis. The rats were first placed on a transparent acrylic chamber. When the rats were stationary, their hind feet were photographed with a webcam placed beneath the chamber. To perform the gait analysis, the rats with stained hind feet were allowed to walk on 5 × 32-in.2 paper inside the chamber, as described in our previous publication.51 Both imaged and ink footprints were manually analyzed using the Static Sciatic Index (SSI) and Sciatic Functional Index (SFI) equations, respectively:61,62

where toe spread factor (TSF) = (operated–normal TS)/normal TS, intermediate toe spread factor (ITSF) = (operated–normal ITS)/normal ITS, and print length factor (PLF) = (operated–normal PL)/normal PL.61,62 The analysis was performed before unblinding the experimental groups.

Gastrocnemius Muscle Electromyography.

At 6- and 16-week time points, before euthanasia, the rats were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane in an induction chamber. The animals were transferred to a nose cone with their lower backs clipped. The surgical sites were reopened by cutting the scars and performing the gluteus split. Incisions were also made across the right calves, from the knee joint to the Achilles tendon. Parts of the biceps femoris were removed to expose the gastrocnemius muscle. Two 29G needle electrodes, connected to a PowerLab 4/26 4-channel recorder (Cat. PL2604, AD Instruments) via a Dual Bio Amp (Cat. FE232, AD Instruments), were implanted into the muscle bellies. Two other needle electrodes, attached to a stimulus isolator (Cat. MLA 1610, AD Instruments), were placed 5–10 mm proximal to the conduit. One ground electrode was inserted midway between the stimulating and recording electrodes. Then 5 mA, 0.1 ms square-wave pulses were delivered to the sciatic nerve, and the compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) were recorded by the LabChart 8 software (AD Instruments). The same procedure/setup was repeated on the left side before the rats were sacrificed. The data files were processed by an in-house MATLAB script that measured the peak amplitudes and pinpointed 10% peak threshold to indicate the onset latencies of CMAPs. The analysis was performed before unblinding the experimental groups.

Gastrocnemius Muscle Weight Measurement.

After euthanasia, the gastrocnemius muscles were isolated after removing the skin and the attached extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles. Excessive connective or adipose tissues were trimmed before the weights of the muscles were measured by a balance (Cat. PG403-S, Mettler Toledo). The analysis was performed before unblinding the experimental groups.

Tissue Processing and Immunofluorescence Staining.

Tissue samples were fixed in 4% PFA solution for 2 days at 4 °C, followed by 2 days of cryopreservation with 20 wt % sucrose solutions. They were then cryo-embedded in Tissue-Plus Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (Cat. 23–730–571, Fisher Scientific) and frozen before storing at −80 °C. Nerves were cut in 20 μm longitudinal or 5 μm cross-sections using a cryostat (Model. CM1850, Leica) and processed for immunofluorescence staining. The sections were treated with 1 wt % Triton-X 100 overnight at room temperature before being blocked with 1 wt % Bovine Serum Albumin for 30 min. Primary antibodies were added and incubated overnight at 4 °C (Table S1). The sections were washed three times with PBS, incubated with secondary antibodies (Table S2) for 1 h, and mounted with ProLong gold antifade mountant with DAPI (Cat. P36935, Fisher Scientific). Longitudinal sections were imaged using a Nikon A1 confocal laser microscope (Nikon, Melville, New York) using a 10× objective. Cross-sections were imaged using both Nikon A1 microscope and Zeiss Elyra 7 with lattice SIM2 microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) using 10× and 40× objectives.

Automatic Axon Counting/Measurement.

The 40× nerve cross-sections (3 random regions selected per location and n = 6 per treatment group) from 16-week end point were first converted into greyscale images. According to the instructions listed in the Axondeepseg software (NeuroPoly, École Polytechnique, Canada) Web site, a subset of representative images was selected to create truth masks.63 The masks and original images were then segmented and used to train the deep learning model. The resulting software parameters are specific for processing images in this work. All images were analyzed by the Axondeepseg software to generate excel sheets that contain the number of myelinated axons, myelin thickness, and g-ratios. A Matlab script was run to remove small/nonmyelinated axons, and the total number of axons were determined using the “particle analyzer” tool in ImageJ. The percentage of myelination was calculated by dividing the number of myelinated axons by the number of total axons.

Statistical Analyses.

The measured or calculated values were averaged, and error bars were displayed as standard error of the mean (S.E.M.) unless otherwise stated. Differences between groups were determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test in GraphPad Prism v. 9.2.0. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

MDPs Display β-Sheet, Shear-Recovery, and Nanofibrous Properties.

In addition to cationic K2(SL)6K2 (K2) from previous work in a nerve crush injury model,51 anionic D2(SL)6D2 (D2) and its laminin derivative, D2(SL)6D2GIKVAV (D2-V), were synthesized to evaluate the efficacy of multidomain peptides (MDPs) in regenerating transected rat sciatic nerves. The molecular weights of synthesized MDPs were confirmed with MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Figure S1). Attenuated total reflectance Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) and circular dichroism (CD) were used to characterize the peptides’ secondary structures (Figure 2a,b). In ATR-FTIR, Amide I∥, Amide I⊥, and Amide II peaks were observed at ~1630 and ~1695, and ~1530 cm−1, respectively, indicating the presence of β-sheet conformation in MDPs.44,45 This property was further supported by maximum/minimum peaks at 197 and 218 nm in CD spectra, in agreement with the characterizations of previously published MDPs.44,45 In oscillatory rheology, the storage moduli of K2, D2, and D2-V (1% oscillation strain and 1 Hz oscillatory frequency) were 204 ± 17, 90 ± 9, and 211 ± 32 Pa, respectively, within the same order of magnitude (Figure 2c). The MDPs’ storage moduli decrease as the oscillation strain increases. After being subjected to 200% oscillatory strain for 1 min, K2, D2, and D2-V’s storage moduli recover to 81 ± 4, 88 ± 12, and 80 ± 17% of their presheared values after 5 min (Figure 2d). These results reveal that MDPs have shear-yielding/shear-recovery properties as expected, which are suitable for in vivo injection. Using scanning electron microscopy, we show that MDPs in aqueous condition form networks of nanofibers, resembling the structure of extracellular matrix (Figure 2e–g).

Figure 2.

Structural characterizations of MDPs. (a) ATR-FTIR spectra and (b) CD spectra of K2, D2, and D2-V peptides. Oscillatory rheology results of K2, D2, and D2-V peptides in (c) amplitude sweep mode and (d) time sweep mode where 200% oscillation strain occurs at t = −1 to 0 min. SEM images of (e) K2, (f) D2, and (g) D2-V peptides taken at 50 000× magnification. Scale bar = 500 nm.

Electrospun Poly(ε-caprolactone) Conduits Are Consistent and Able to Withstand Surgical Manipulation.

To guide nerve regeneration and contain MDPs at the injured site, we fabricated poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) conduits via electrospinning on a rotating mandrel with 1.6 mm diameter (Figure 3a). Made of intertwined microfibers, the conduits are porous and could facilitate oxygen and nutrients diffusion (Figure 3b).55,56 The conduits were cut to 14 mm long and soaked in ethanol and HBSS to remove leftover trifluoroethanol and any other leachables. The dimensions of PCL conduits, confirmed with a caliper, remain the same after soaking and match our target dimensions (Figure 3c–e). A suture pull-out test was also performed on the conduits by tying suture knots and pulling them on a mechanical tester until failure. The suture retention strength of PCL conduits was found to be 1830 ± 50 g m/s2 and higher than the literature-suggested minimum value 50 g m/s2, showing that our conduits can withstand surgical manipulation (Figure 3f).64,65

Figure 3.

(a) 14 mm PCL conduit with its (b) SEM image at 1000× magnification. (c) Inner diameter, (d) length, and (e) thickness of the conduits are consistent before treatment (green) and after 2 days of ethanol and 1 (red) or 2 (blue) days of HBSS. Target inner diameter and length are 2 mm and 10 mm, respectively (n = 12 among 3 batches). (f) Gram force vs strain plot from suture pull-out test (suture retention strength = 1830 ± 50 g m/s2, ultimate tensile strain = 400 ± 20%).

D2(SL)6D2-Loaded Electrospun PCL Conduits Improve Functional Recovery 16 Weeks after Nerve Transection.

We used an in vivo rat sciatic nerve injury model to study the efficacy of MDPs and PCL conduits in promoting nerve regeneration. After exposing the sciatic nerves via gluteus split, we introduced 10 mm defect gaps and repaired them with PCL conduits filled with different MDPs or HBSS (Figure 4a–c). After conduit placement at the injury site, a secondary injection was performed before closing to ensure the conduits were completely filled. Some nerve defects were treated with reverse autografts, the current gold standard of treatment (Figure 4d). We also included sham and no treatment groups in this experiment as positive and negative control groups, respectively. At 6- and 16-weeks postoperation, we performed gastrocnemius muscles electromyography, along with muscle weight measurements, to assess the electrical conduction of regenerated nerve fibers and the extent of muscle atrophy (Figures 5a,b and 6a,b). The acquired compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) from injured legs were normalized with the contralateral CMAPs and expressed in percentages. At the 6-week time point, the percentages of CMAPs in reverse autograft and electrospun PCL conduits with MDPs/HBSS (MDPs + PCL/HBSS + PCL) groups range from 6 to 21%, with no statistical difference among experimental groups (Figure 5c). The right gastrocnemius muscle weight of reverse autograft group is 0.68 ± 0.05 g, which is greater than those of other experimental groups from 0.46 to 0.5 g (Figure 6c).

Figure 4.

(a) Sciatic nerve is exposed with the defect size measured using a ruler. (b) Nerve is cut to create a 10 mm gap. (c) Image of PCL conduits with MDPs or HBSS bridging the gap after 16-week implantation. (d) Image of reverse autograft at day 0 before wound closing.

Figure 5.

Electromyography (EMG). (a) Electrodes’ placement during EMG recording. (b) An example of CMAP amplitude measured in Labchart software. % CMAP amplitude data normalized with left, uninjured CMAP at (c) 6- and (d) 16-week time points. (One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Gastrocnemius muscle measurements. Representative images of left (uninjured) and right (injured) gastrocnemius muscles at (a) 6- and (b) 16-week time points. Gastrocnemius muscle weight data at (c) 6- and (d) 16-week time points (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD. * = with respect to neg control and a = with respect to reverse autograft. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

At the 16-week time point, the percentages of CMAPs in reverse autograft, D2, K2, and D2-V, and HBSS (+ PCL) groups are 57 ± 5, 40 ± 6, 26 ± 6, 23 ± 5, and 33 ± 7%, with negative control group being the lowest at 8 ± 2% (Figure 5d). The reverse autograft and D2 + PCL groups have statistically higher % CMAPs than the negative control. Moreover, the reverse autograft and D2 + PCL groups have comparable % CMAPs. Comparisons between MDPs and HBSS in PCL conduits do not reveal statistically significant differences.

The right gastrocnemius muscles in reverse autograft, D2, K2, D2-V, HBSS (+ PCL), and negative control groups weigh 1.00 ± 0.03, 0.80 ± 0.08, 0.58 ± 0.09, 0.58 ± 0.07, 0.65 ± 0.07, and 0.31 ± 0.02 g, respectively (Figure 6d). The increased weight of muscle in the D2 filled PCL conduits compared to the negative control is very significant (p < 0.001), while the difference between HBSS + PCL and negative control group is statistically significant (p < 0.03). Additionally, the weights of right muscles in reverse autograft and D2 filled PCL groups are not statistically different from one another. Thus, D2 filled in poly(ε-caprolactone) conduits may provide improvement in recovering electrical function and attenuating muscle atrophy over K2, D2-V, and HBSS (+PCL) at 16 weeks postoperation.

We monitored the 16-week group (6 rats from each treatment group) and performed gait analysis to acquire sciatic functional index (SFI) and static sciatic index (SSI) scores, commonly used metrics to evaluate motor function recovery due to nerve regeneration. No conclusive results were seen because of the onset of flexion contracture and autophagia, which severely affect the quality of rat footprints (Figure S2a,b). In related studies, the occurrence of flexion contracture after sciatic nerve transection is correlated to larger numbers of regenerated axons, showing early signs of nerve regeneration.66,67 Hence, we recorded the number of rats developing flexion contracture every 2 weeks (Figure 7a,b). Throughout this study, no rats in the negative control group develop contracture (Figure 7c), which suggested no regeneration. On the other hand, rats in other treatment groups subsequently developed flexion contracture. At the 6-week time point, 33% of the rats in the reverse autograft group developed contracture. At the 8-week time point, 67% of the rats in the autograft and D2 + PCL groups developed contracture, while 33% of the rats in the HBSS + PCL group developed contracture. The percentage of contracture in the autograft and D2 + PCL groups increased to 83% at the 10-week time point, while the percentage of contracture stayed the same for the other groups. As 100% of the rats in the autograft group develop contracture after 14 weeks, the percentage of contracture in the D2 + PCL group remains at 83% for the rest of the study. At 12 weeks, 67% rats developed contracture in the HBSS + PCL group and remained the same afterward. The percentage of contracture in the D2-V + PCL and K2 + PCL groups reached 33% at 14 weeks. The earlier onset of flexion contracture in the D2 + PCL group, compared with other MDPs + PCL and HBSS + PCL groups, may be caused by imbalanced muscle contractions and incomplete motor recovery that indicate faster muscle reinnervation.66,67

Figure 7.

Onset of flexion contractures. Example images of injured rat’s feet (a) without and (b) with flexion contracture, marked by yellow dotted lines. (c) % rats with flexion contracture for 16 weeks after sciatic nerve injury/repair.

K2(SL)6K2 in PCL Conduit Has Lowest Percentage of Cross-Sectional Axon Area at 6 Weeks.

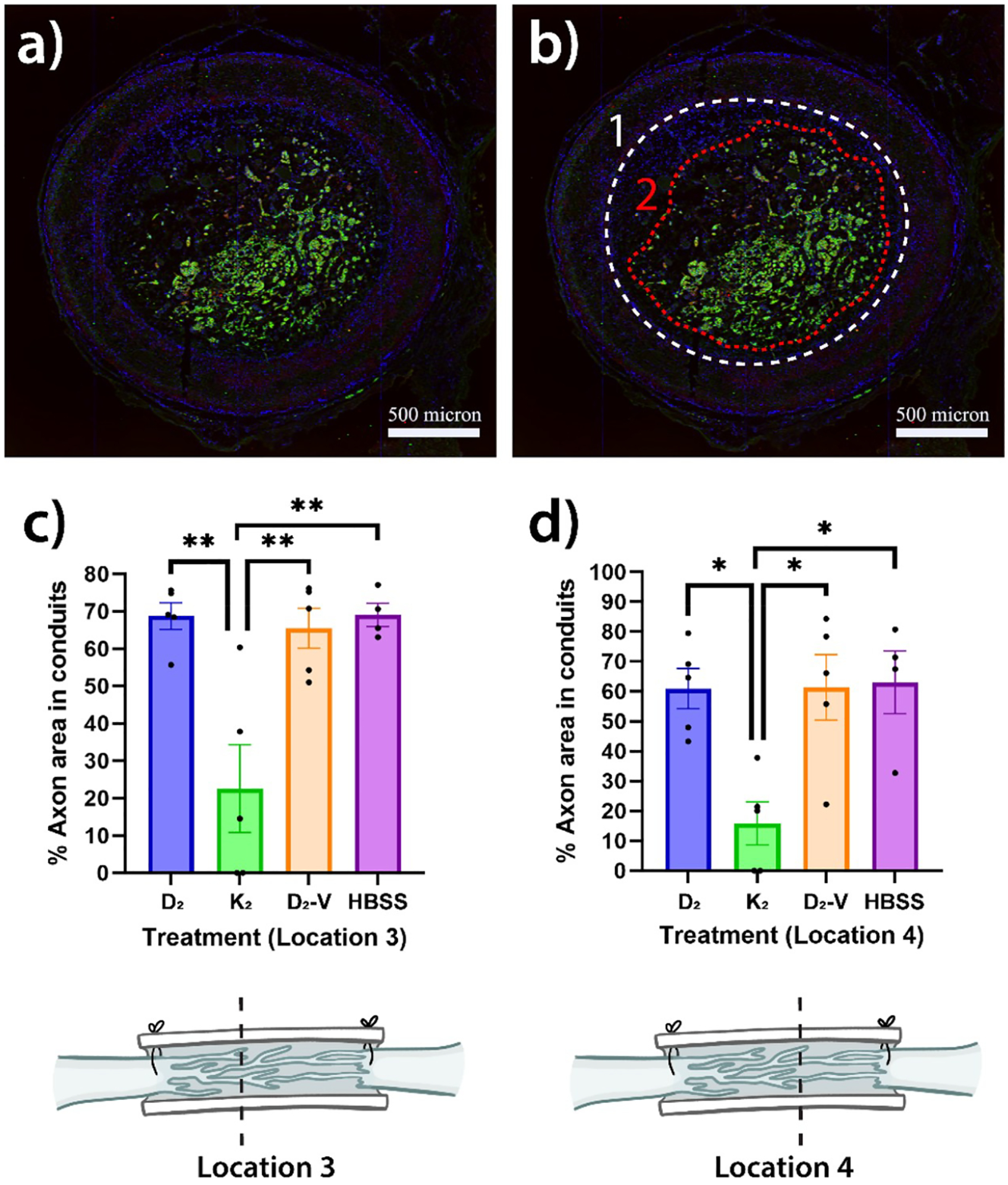

We immunostained the cross-sections of extracted nerve tissues with conduits to visualize the population of regenerated axons and myelin sheaths at 10× magnification. Data on the percentage of axon area within conduits were obtained at six locations (Figure 8) to quantify and compare overall nerve regeneration among MDPs + PCL and HBSS + PCL groups (Figure 9a,b). At 6 weeks, the % axon areas in K2 + PCL group are 23 ± 12 and 16 ± 7% at locations 3 and 4, statistically lower than those in other experimental groups with values ranging from 61 ± 7 to 69 ± 3% (Figure 9c,d). At location 5, the percentage in K2 + PCL group is statistically lower than HBSS + PCL group (Figure S3c). At 16 weeks, no difference is observed among experimental groups (Figure S4a–d).

Figure 8.

Locations of nerve cross-sections processed throughout the extracted nerve tissue and conduit. The dotted blue lines at the proximal and distal ends show the initial positions of transected nerve, while the black dotted lines denote locations 1–6.

Figure 9.

Percent cross-sectional axon area in conduits measurements. (a) Sample nerve and PCL conduit cross-sectional image. (b) Sample area measurement of conduit (1) and axon (2) using ImageJ. Percent axon area in conduit data of treatment groups after 6 weeks at location (c) 3 and (d) 4 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

K2(SL)6K2 in PCL Conduit Has Lowest Percentage of Myelination at 16-Weeks; Reverse Autograft Outperforms in Total Number of Myelinated Axons.

We analyzed the nerve morphometry of 16-week, cross-sectional tissue samples at 40× magnification using Axondeepseg software. A trained model specific to our data set was used to automatically calculate parameters such as the number of myelinated axons and the mean of myelin thickness.63,68 The total number of axons was determined using ImageJ’s particle analysis tool. As myelination occurs at a later stage of nerve regeneration, the percentage of myelination is useful in assessing the long-term progress of nerve regeneration.51,69 In locations 3 to 5, the K2 + PCL group has the lowest percentage of myelination (Figure 10a). This result indicates delayed nerve regenerations of the K2 + PCL group when compared with other experimental groups. At location 5, the % myelination of reverse autograft group is 47 ± 3%, which is statistically better than those of other treatment groups ranging from 22 ± 1% to 33 ± 1%. In terms of the total number of myelinated axons, reverse autograft group outperforms other experimental groups at location 3 (Figure 10b). Also, it has a statistically higher number of myelinated axons than D2, K2, and D2-V (+ PCL) groups at location 5; K2 and D2-V (+ PCL) groups at location 6 (Figures 10b and S6b). The morphometric analysis demonstrates that reverse autograft group elicits the best myelination as K2 + PCL group induces the worst structural recovery of sciatic nerves.

Figure 10.

Automatic axon counting of 16-week cross-sectional images using Axondeepseg software. (a) Percent myelination and (b) number of myelinated axon at location 3–5 in treatment groups (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Because of their nanofibrous and bioactive properties, cationic MDPs have been used to accelerate rat nerve regeneration after crush injuries.51 Cationic MDPs elicit inflammatory responses and promote early macrophage infiltration, which is essential to induce Wallerian degeneration.51,70 Yet, some previous studies in cationic MDPs and other peptides reported their cytotoxicity.71,72 This effect may limit the number of axons growing into the hydrogels, offsetting the short-term benefits of Wallerian degeneration. Therefore, anionic MDPs can be suitable alternatives to cationic MDPs in regenerating transected nerve injuries. To evaluate MDP’s capacity in restoring more challenging defects and explore how their chemical functionalities affect nerve regeneration, we introduce K2(SL)6K2 (cationic), D2(SL)6D2 (anionic), and D2(SL)6D2GIKVAV (anionic with laminin mimic sequence) peptides into poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) conduits to bridge 10 mm sciatic nerve gaps. We hypothesize that the use of MDPs, as intraluminal fillers in PCL conduits, would result in better functional and structural regeneration than HBSS in PCL conduits. D2 + PCL has statistically higher % CMAPs than negative control group (no surgical repair). In terms of right gastrocnemius muscle weights, the difference between D2 + PCL and negative control groups is more statistically significant than that between HBSS + PCL and negative control groups. These results may suggest slight functional improvement of D2 + PCL over HBSS + PCL, which is further supported by earlier occurrence of flexion contractures in D2 + PCL than in HBSS + PCL.

Even though immunofluorescence staining of nerve tissues does not show any morphological difference between D2 + PCL and HBSS + PCL, it explains the poor performance of K2 in sciatic nerve regeneration. In 3-week longitudinal sections, undegraded K2 hydrogel can be found within the conduits, which prevent the axons from connecting to the distal ends (Figure S8). Axonal outgrowth in K2 + PCL is statistically lower than that in HBSS + PCL. No gel-like substance was observed in other experimental groups, indicating complete degradation within 3 weeks. Some K2 hydrogel remains nondegraded 6 weeks postoperation, contributing to lower percentage of axon area in the middle and distal regions of conduits (Figure 11). The delayed nerve regeneration leads to lower percentage of myelination at 16 weeks (Figures 10a and S6a). As D2 and D2-V share similar rheological properties with K2 and degrade before 3 weeks (Figures 2c,d, S8, and 11), the electrostatic charge of MDPs has major influence in the degradation rate of hydrogels, in agreement with the previous in vivo mouse study.71 When injected into mice subcutaneously, K2 remained after 10 days, while most D2 was degraded after 7 days.71 Unlike crush injuries, nerve transections require a higher volume of hydrogels to fill the defect gaps, making timely degradation of cationic peptide more difficult. As cationic peptide impedes axon extension, it is not suitable for repairing large nerve defects.

Figure 11.

Representative confocal images of 6-week nerve cross-sections. A yellow arrow indicates the undegraded K2 hydrogel (green = β-Tubulin III, red = Myelin basic protein, Blue = DAPI; Scale bar = 500 μm).

While D2 filled electrospun PCL conduits appear to result in improvements over no-treatment negative control and in some cases are statistically equivalent to the reverse autograft group, more detailed comparisons were made difficult by a combination of relatively small effect size and large standard deviations. This prevented us from observing statistical difference among the PCL conduit groups. Additionally, the sacrificial time points do not coincide with the actual recovery as demonstrated by flexion contracture data where differences in motor recovery were the largest between 8–12 weeks. As muscle weight measurements, electromyography data, and histomorphology results follow a similar pattern, large standard deviations are mainly caused by uncertainty from in vivo studies, not instrument variance. The individual data points obtained from electromyography correlate well with those from muscle weight and flexion contracture measurements. Despite our best efforts in mitigating research uncertainty, human factors during surgery and sample processing could reduce the precision of our results. To generate more conclusive results, future experimental designs may include more animals to lower the effects of outliers. Changing sacrificial time points to 8–12 weeks may capture differences when significant regeneration occurs. Furthermore, the neuroregenerative properties of D2 may be enhanced by adding neurotrophic factors, encapsulating stem cells, or optimizing the peptide sequence.

CONCLUSION

MDPs are self-assembling peptides that can facilitate nerve regeneration by providing extracellular matrix-like support. To evaluate their effectiveness in treating transected nerve injuries, MDPs were filled into PCL conduits to bridge 10 mm rat sciatic nerve gaps in vivo. Anionic D2(SL)6D2 in PCL conduits provide more functional recovery than untreated, negative control group 16 weeks postoperation, as shown in electromyography, gastrocnemius muscle weight, and flexion contracture data. Conversely, cationic K2(SL)6K2 in PCL conduits exhibit the smallest axon area at 6-week and degree of myelination at 16-weeks compared with other MDPs and HBSS in conduits groups. This phenomenon can be explained by the poor degradation of K2, which impacts the growth of newly regenerated nerve fibers. As the chemical functionality and rheological properties of MDPs dictate the degradation time, they play important roles in determining MDPs’ neuroregenerative capability. D2 in PCL conduits may not lead to a significantly better outcomes in treating transected peripheral nerve injuries (PNI) due to the complex and coordinated nature of peripheral nerve regeneration. Therefore, future efforts will involve the addition of neurotrophic elements or the optimization of peptide sequences to potentially make anionic MDP a viable tissue engineering strategy for treating transected PNI.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by funding from National Institute of Health (NIH) (R01 DE021798). We gratefully acknowledge additional funding from the following institutions: The National Multiple Sclerosis Society (RG-1907-34551), NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS110859), and The Cynthia and Anthony G. Petrello Endowment. C.S.E.L. and A.C.F. were supported by the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program (1842494 and 2021312035). V.L.-A. and T.L.L.-S. were supported by the Mexican National Council for Science and Technology (CONACyT) Ph.D. Scholarship Program (862901 and 678341). The authors thank Brett H. Pogostin for the assistance in sciatic nerve surgeries, Alloysius J. Budi Utama for the assistance in microscopy imaging, and Christine W. Y. Luk for the assistance with Axondeepseg.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsabm.2c00132.

Additional characterization of peptides, additional in vivo characterization (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acsabm.2c00132

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Cheuk Sun Edwin Lai, Department of Bioengineering, Rice University, Houston, Texas 77005, United States.

Viridiana Leyva-Aranda, Department of Chemistry, Rice University, Houston, Texas 77005, United States.

Victoria H. Kong, Department of Bioengineering, Rice University, Houston, Texas 77005, United States

Tania L. Lopez-Silva, Department of Chemistry, Rice University, Houston, Texas 77005, United States; Present Address: Chemical Biology Laboratory, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. Frederick, Maryland 21702, United States

Adam C. Farsheed, Department of Bioengineering, Rice University, Houston, Texas 77005, United States

Carlo D. Cristobal, Integrative Program in Molecular and Biomedical Sciences, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas 77030, United States

Joseph W. R. Swain, Department of Chemistry, Rice University, Houston, Texas 77005, United States

Hyun Kyoung Lee, Integrative Program in Molecular and Biomedical Sciences, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas 77030, United States;; Department of Pediatrics, Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, Texas 77030, United States

Jeffrey D. Hartgerink, Department of Bioengineering, Rice University, Houston, Texas 77005, United States; Department of Chemistry, Rice University, Houston, Texas 77005, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Eser F; Aktekin L; Bodur H; Atan Ç Etiological Factors of Traumatic Peripheral Nerve Injuries. Neurol. India 2009, 57 (4), 434–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Taylor CA; Braza D; Rice JB; Dillingham T The Incidence of Peripheral Nerve Injury in Extremity Trauma. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil 2008, 87 (5), 381–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Raza C; Riaz HA; Anjum R; Shakeel NUA Repair Strategies for Injured Peripheral Nerve: Review. Life Sci. 2020, 243, 117308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Gaudin R; Knipfer C; Henningsen A; Smeets R; Heiland M; Hadlock T Approaches to Peripheral Nerve Repair: Generations of Biomaterial Conduits Yielding to Replacing Autologous Nerve Grafts in Craniomaxillofacial Surgery. Biomed Res. Int 2016, 2016, 3856262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kehoe S; Zhang XF; Boyd D FDA Approved Guidance Conduits and Wraps for Peripheral Nerve Injury: A Review of Materials and Efficacy. Injury 2012, 43 (5), 553–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).López-Cebral R; Silva-Correia J; Reis RL; Silva TH; Oliveira JM Peripheral Nerve Injury: Current Challenges, Conventional Treatment Approaches, and New Trends in Biomaterials-Based Regenerative Strategies. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2017, 3 (12), 3098–3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Gu X; Ding F; Williams DF Biomaterials Neural Tissue Engineering Options for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Biomaterials 2014, 35 (24), 6143–6156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Kornfeld T; Vogt PM; Radtke C Nerve Grafting for Peripheral Nerve Injuries with Extended Defect Sizes. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift 2019, 169, 240–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Meek MF; Den Dunnen WF Porosity of The Wall of A Neurolac Nerve Conduit Hampers Nerve Regeneration. Microsurgery 2009, 29 (6), 473–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Luis AL; Rodrigues JM; Amado S; Veloso AP; Armada-Da-silva PA; Raimondo S; Fregnan F; Ferreira AJ; Lopes MA; Santos JD; Geuna S; et al. PLGA 90/10 and Caprolactone Biodegradable Nerve Guides for the Reconstruction of the Rat Sciatic Nerve. Microsurgery 2007, 27 (2), 125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zuniga JR; Williams F; Petrisor D A Case-and-Control, Multisite, Positive Controlled, Prospective Study of the Safety and Effectiveness of Immediate Inferior Alveolar Nerve Processed Nerve Allograft Reconstruction With Ablation of the Mandible for Benign Pathology. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg 2017, 75 (12), 2669–2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Moore AM; MacEwan M; Santosa KB; Chenard KE; Ray WZ; Hunter DA; Mackinnon SE; Johnson PJ Acellular Nerve Allografts in Peripheral Nerve Regeneration: A Comparative Study. Muscle and Nerve 2011, 44 (2), 221–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Pateman CJ; Harding AJ; Glen A; Taylor CS; Christmas CR; Robinson PP; Rimmer S; Boissonade FM; Claeyssens F; Haycock JW Nerve Guides Manufactured from Photocurable Polymers to Aid Peripheral Nerve Repair. Biomaterials 2015, 49, 77–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hu Y; Wu Y; Gou Z; Tao J; Zhang J; Liu Q; Kang T; Jiang S; Huang S; He J; Chen S; Du Y; Gou M 3D-Engineering of Cellularized Conduits for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Qian Y; Zhao X; Han Q; Chen W; Li H; Yuan W An Integrated Multi-Layer 3D-Fabrication of PDA/RGD Coated Graphene Loaded PCL Nanoscaffold for Peripheral Nerve Restoration. Nat. Commun 2018, 9 (1), 323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Yao L; O’Brien N; Windebank A; Pandit A Orienting Neurite Growth in Electrospun Fibrous Neural Conduits. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. - Part B Appl. Biomater 2009, 90B (2), 483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Niu Y; Chen KC; He T; Yu W; Huang S; Xu K Scaffolds from Block Polyurethanes Based on Poly(Epsilon-Caprolactone) (PCL) and Poly(Ethylene Glycol) (PEG) for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Biomaterials. 2014, 35, 4266–4277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Sarker MD; Naghieh S; McInnes AD; Schreyer DJ; Chen X Regeneration of Peripheral Nerves by Nerve Guidance Conduits: Influence of Design, Biopolymers, Cells, Growth Factors, and Physical Stimuli. Progress in Neurobiology. 2018, 171, 125–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Madduri S; di Summa P; Papaloïzos M; Kalbermatten D; Gander B Effect of Controlled Co-Delivery of Synergistic Neurotrophic Factors on Early Nerve Regeneration in Rats. Biomaterials 2010, 31 (32), 8402–8409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Madduri S; Feldman K; Tervoort T; Papaloïzos M; Gander B Collagen Nerve Conduits Releasing the Neurotrophic Factors GDNF and NGF. J. Controlled Release 2010, 143 (2), 168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Karagoz H; Ulkur E; Kerimoglu O; Alarcin E; Sahin C; Akakin D; Dortunc B Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-Loaded Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) Microspheres-Induced Lateral Axonal Sprouting Into the Vein Graft Bridging Two Healthy Nerves: Nerve Graft Prefabrication Using Controlled Release System. Microsurgery 2012, 32 (8), 635–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Roam JL; Yan Y; Nguyen PK; Kinstlinger IS; Leuchter MK; Hunter DA; Wood MD; Elbert DL A Modular, Plasmin-Sensitive, Clickable Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Heparin-Laminin Microsphere System for Establishing Growth Factor Gradients in Nerve Guidance Conduits. Biomaterials 2015, 72, 112–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Ansselin AD; Fink T; Davey DF Peripheral Nerve Regeneration through Nerve Guides Seeded with Adult Schwann Cells. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol 1997, 23 (5), 387–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Widgerow AD; Salibian AA; Lalezari S; Evans GRD Neuromodulatory Nerve Regeneration: Adipose Tissue-Derived Stem Cells and Neurotrophic Mediation in Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. J. Neurosci. Res 2013, 91 (12), 1517–1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Sun AX; Prest TA; Fowler JR; Brick RM; Gloss KM; Li X; DeHart M; Shen H; Yang G; Brown BN; Alexander PG; Tuan RS Conduits Harnessing Spatially Controlled Cell-Secreted Neurotrophic Factors Improve Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Biomaterials 2019, 203, 86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Kimura H; Ouchi T; Shibata S; Amemiya T; Nagoshi N; Nakagawa T; Matsumoto M; Okano H; Nakamura M; Sato K Stem Cells Purified from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Neural Crest-like Cells Promote Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Sci. Rep 2018, 8 (1), 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Arcaute K; Mann BK; Wicker RB Fabrication of Off-the-Shelf Multilumen Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Nerve Guidance Conduits Using Stereolithographyxs. Tissue Eng. - Part C Methods 2011, 17 (1), 27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Yao L; de Ruiter GCW; Wang H; Knight AM; Spinner RJ; Yaszemski MJ; Windebank AJ; Pandit A Controlling Dispersion of Axonal Regeneration Using a Multichannel Collagen Nerve Conduit. Biomaterials 2010, 31 (22), 5789–5797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Hou Y; Wang X; Zhang Z; Luo J; Cai Z; Wang Y; Li Y Repairing Transected Peripheral Nerve Using a Biomimetic Nerve Guidance Conduit Containing Intraluminal Sponge Fillers. Adv. Healthc. Mater 2019, 8 (21), 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Rao F; Yuan Z; Li M; Yu F; Fang X; Jiang B; Wen Y; Zhang P Expanded 3D Nanofibre Sponge Scaffolds by Gas-Foaming Technique Enhance Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Artif. Cells, Nanomedicine Biotechnol 2019, 47 (1), 491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Singh A; Asikainen S; Teotia AK; Shiekh PA; Huotilainen E; Qayoom I; Partanen J; Seppälä J; Kumar A Biomimetic Photocurable Three-Dimensional Printed Nerve Guidance Channels with Aligned Cryomatrix Lumen for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10 (50), 43327–43342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Huang L; Zhu L; Shi X; Xia B; Liu Z; Zhu S; Yang Y; Ma T; Cheng P; Luo K; Huang J; Luo Z A Compound Scaffold with Uniform Longitudinally Oriented Guidance Cues and a Porous Sheath Promotes Peripheral Nerve Regeneration in Vivo. Acta Biomater. 2018, 68, 223–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Du J; Liu J; Yao S; Mao H; Peng J; Sun X; Cao Z; Yang Y; Xiao B; Wang Y; Tang P; Wang X Prompt Peripheral Nerve Regeneration Induced by a Hierarchically Aligned Fibrin Nanofiber Hydrogel. Acta Biomater. 2017, 55, 296–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Mokarram N; Dymanus K; Srinivasan A; Lyon JG; Tipton J; Chu J; English AW; Bellamkonda RV Immunoengineering Nerve Repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2017, 114 (26), E5077–E5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Magaz A; Faroni A; Gough JE; Reid AJ; Li X; Blaker JJ Bioactive Silk-Based Nerve Guidance Conduits for Augmenting Peripheral Nerve Repair. Adv. Healthc. Mater 2018, 7 (23), 1800308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Hamsici S; Cinar G; Celebioglu A; Uyar T; Tekinay AB; Guler MO Bioactive Peptide Functionalized Aligned Cyclodextrin Nanofibers for Neurite Outgrowth. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5 (3), 517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Mammadov B; Sever M; Gecer M; Zor F; Ozturk S; Akgun H; Ulas UH; Orhan Z; Guler MO; Tekinay AB Sciatic Nerve Regeneration Induced by Glycosaminoglycan and Laminin Mimetic Peptide Nanofiber Gels. RSC Adv. 2016, 6 (112), 110535–110547. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Lu J; Sun X; Yin H; Shen X; Yang S; Wang Y; Jiang W; Sun Y; Zhao L; Sun X; Lu S; Mikos AG; Peng J; Wang X A Neurotrophic Peptide-Functionalized Self-Assembling Peptide Nanofiber Hydrogel Enhances Rat Sciatic Nerve Regeneration. Nano Res. 2018, 11 (9), 4599–4613. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Leach JB; Brown XQ; Jacot JG; Dimilla PA; Wong JY Neurite Outgrowth and Branching of PC12 Cells on Very Soft Substrates Sharply Decreases below a Threshold of Substrate Rigidity. J. Neural Eng 2007, 4 (2), 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Wheeldon I; Farhadi A; Bick AG; Jabbari E; Khademhosseini A Nanoscale Tissue Engineering: Spatial Control over Cell-Materials Interactions. Nanotechnology 2011, 22 (21), 212001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Levin A; Hakala TA; Schnaider L; Bernardes GJL; Gazit E; Knowles TPJ Biomimetic Peptide Self-Assembly for Functional Materials. Nat. Rev. Chem 2020, 4 (11), 615–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Wu X; He L; Li W; Li H; Wong W-M; Ramakrishna S; Wu W Functional Self-Assembling Peptide Nanofiber Hydrogel for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Regen. Biomater 2017, 4 (1), 21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Li A; Hokugo A; Yalom A; Berns EJ; Stephanopoulos N; McClendon MT; Segovia LA; Spigelman I; Stupp SI; Jarrahy R A Bioengineered Peripheral Nerve Construct Using Aligned Peptide Amphiphile Nanofibers. Biomaterials 2014, 35 (31), 8780–8790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Dong H; Paramonov SE; Aulisa L; Bakota EL; Hartgerink JD Self-Assembly of Multidomain Peptides: Balancing Molecular Frustration Controls Conformation and Nanostructure. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129 (41), 12468–12472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Aulisa L; Dong H; Hartgerink JD Self-Assembly of Multidomain Peptides: Sequence Variation Allows Control over Cross-Linking and Viscoelasticity. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10 (9), 2694–2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Kumar VA; Taylor NL; Shi S; Wang BK; Jalan AA; Kang MK; Wickremasinghe NC; Hartgerink JD Highly Angiogenic Peptide Nanofibers. ACS Nano 2015, 9 (1), 860–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Kumar VA; Liu Q; Wickremasinghe NC; Shi S; Cornwright TT; Deng Y; Azares A; Moore AN; Acevedo-Jake AM; Agudo NR; Pan S; Woodside DG; Vanderslice P; Willerson JT; Dixon RA; Hartgerink JD Treatment of Hind Limb Ischemia Using Angiogenic Peptide Nanofibers. Biomaterials 2016, 98, 113–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Carrejo NC; Moore AN; Lopez Silva TL; Leach DG; Li I-C; Walker DR; Hartgerink JD Multidomain Peptide Hydrogel Accelerates Healing of Full-Thickness Wounds in Diabetic Mice. ACS Biomater Sci. Eng 2018, 4 (4), 1386–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Leach DG; Dharmaraj N; Piotrowski SL; Lopez-Silva TL; Lei YL; Sikora AG; Young S; Hartgerink JD STINGel: Controlled Release of a Cyclic Dinucleotide for Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2018, 163, 67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Leach DG; Newton JM; Florez MA; Lopez-Silva TL; Jones AA; Young S; Sikora AG; Hartgerink JD Drug-Mimicking Nanofibrous Peptide Hydrogel for Inhibition of Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2019, 5, 6755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Lopez-Silva TL; Cristobal CD; Lai CSE; Leyva-Aranda V; Lee HK; Hartgerink JD Self-Assembling Multidomain Peptide Hydrogels Accelerate Peripheral Nerve Regeneration after Crush Injury. Biomaterials 2021, 265, 120401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Hazer Rosberg DB; Hazer B; Stenberg L; Dahlin LB Gold and Cobalt Oxide Nanoparticles Modified Poly-propylene Polyethylene Glycol Membranes in Poly (E-caprolactone) Conduits Enhance Nerve Regeneration in the Sciatic Nerve of Healthy Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2021, 22 (13), 7146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Miller K; Hsu JE; Soslowsky LJ Materials in Tendon and Ligament Repair; Elsevier Ltd., 2011, 6, 257–279. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Koh CT; Strange DGT; Tonsomboon K; Oyen ML Failure Mechanisms in Fibrous Scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9 (7), 7326–7334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Rutkowski GE; Heath CA Development of a Bioartificial Nerve Graft. I. Design Based on a Reaction-Diffusion Model. Biotechnol. Prog 2002, 18 (2), 362–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Rutkowski GE; Heath CA Development of a Bioartificial Nerve Graft. II. Nerve Regeneration in Vitro. Biotechnol. Prog 2002, 18 (2), 373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).de Ruiter GCW; Malessy MJA; Yaszemski MJ; Windebank AJ; Spinner RJ Designing Ideal Conduits for Peripheral Nerve Repair. Neurosurg. Focus 2009, 26 (2), E5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Sunderland S A Classification of Peripheral Nerve Injuries Producing Loss of Function. Brain 1951, 74 (4), 491–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Osawa T; Tohyama K; Ide C Allogeneic Nerve Grafts in the Rat, with Special Reference to the Role of Schwann Cell Basal Laminae in Nerve Regeneration. J. Neurocytol 1990, 19 (6), 833–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).DeLeonibus A; Rezaei M; Fahradyan V; Silver J; Rampazzo A; Bassiri Gharb B A Meta-Analysis of Functional Outcomes in Rat Sciatic Nerve Injury Models. Microsurgery 2021, 41 (3), 286–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Smit X; Van Neck JW; Ebeli MJ; Hovius SER Static Footprint Analysis: A Time-Saving Functional Evaluation of Nerve Repair in Rats. Scand. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Hand Surg 2004, 38 (6), 321–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Sarikcioglu L; Demirel BM; Utuk A Walking Track Analysis: An Assessment Method for Functional Recovery after Sciatic Nerve Injury in the Rat. Folia Morphol. (Warsz) 2009, 68 (1), 1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Zaimi A; Wabartha M; Herman V; Antonsanti PL; Perone CS; Cohen-Adad J AxonDeepSeg: Automatic Axon and Myelin Segmentation from Microscopy Data Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Sci. Rep 2018, 8 (1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Konig G; Mcallister TN; Ph D; Dusserre N; Garrido S. a; Iyican C; Marini A; Fiorillo A; Avila H; Zagalski K; Maruszewski M; et al. Mechanical Properties of Completely Autologous Human Tissue Engineered Blood Vessels Compared to Human Saphenous Vein and Mammary Artery. Biomaterials 2009, 30 (8), 1542–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Lu Q; Zhang F; Cheng W; Gao X; Ding Z; Zhang X; Lu Q; Kaplan DL Nerve Guidance Conduits with Hierarchical Anisotropic Architecture for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Adv. Healthc. Mater 2021, 10 (14), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Chamberlain LJ; Yannas IV; Hsu HP; Strichartz GR; Spector M Near-Terminus Axonal Structure and Function Following Rat Sciatic Nerve Regeneration through a Collagen-GAG Matrix in a Ten-Millimeter Gap. J. Neurosci. Res 2000, 60 (5), 666–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Lee JY; Giusti G; Wang H; Friedrich PF; Bishop AT; Shin AY Functional Evaluation in the Rat Sciatic Nerve Defect Model: A Comparison of the Sciatic Functional Index, Ankle Angles, and Isometric Tetanic Force. Plast. Reconstr. Surg 2013, 132 (5), 1173–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Wong AL; Hricz N; Malapati H; Von Guionneau N; Wong M; Harris T; Boudreau M; Cohen-Adad J; Tuffaha S A Simple and Robust Method for Automating Analysis of Naïve and Regenerating Peripheral Nerves. PLoS One 2021, 16, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Liu B; Xin W; Tan JR; Zhu RP; Li T; Wang D; Kan SS; Xiong DK; Li HH; Zhang MM; Sun HH; Wagstaff W; Zhou C; Wang ZJ; Zhang YG; He TC Myelin Sheath Structure and Regeneration in Peripheral Nerve Injury Repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2019, 116 (44), 22347–22352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Rotshenker S Wallerian Degeneration: The Innate-Immune Response to Traumatic Nerve Injury. J. Neuroinflammation 2011, 8, 209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Lopez-Silva TL; Leach DG; Azares A; Li IC; Woodside DG; Hartgerink JD Chemical Functionality of Multidomain Peptide Hydrogels Governs Early Host Immune Response. Biomaterials 2020, 231, 119667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Bacalum M; Radu M Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides Cytotoxicity on Mammalian Cells: An Analysis Using Therapeutic Index Integrative Concept. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther 2015, 21 (1), 47–55. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.