Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs that play a fundamental role in enabling miRNA-mediated target repression, a post-transcriptional gene regulatory mechanism preserved across metazoans. Loss of certain animal miRNA genes can lead to developmental abnormalities, disease, and various degrees of embryonic lethality. These short RNAs normally guide Argonaute (AGO) proteins to target RNAs, which are in turn translationally repressed and destabilized, silencing the target to fine-tune gene expression and maintain cellular homeostasis. Delineating miRNA-mediated target decay has been thoroughly examined in thousands of studies, yet despite these exhaustive studies, comparatively less is known about how and why miRNAs are directed for decay. Several key observations over the years have noted instances of rapid miRNA turnover, suggesting endogenous means for animals to induce miRNA degradation. Recently, it was revealed that certain targets, so-called target-directed miRNA degradation (TDMD) triggers, can “trigger” miRNA decay through inducing proteolysis of AGO and thereby the bound miRNA. This process is mediated in animals via the ZSWIM8 ubiquitin ligase complex, which is recruited to AGO during engagement with triggers. Since its discovery, several studies have identified that ZSWIM8 and TDMD are indispensable for proper animal development. Given the rapid expansion of this field of study, here, we summarize the key findings that have led to and followed the discovery of ZSWIM8-dependent TDMD.

Graphical Abstract

A model of the current ZSWIM8-dependent target-directed miRNA degradation (TDMD) mechanism. A trigger RNA (maroon) bearing extensive complementarity to an AGO-loaded miRNA (cyan, black), will direct AGO for turnover via recruitment of the ZSWIM8 ubiquitin ligase complex (green), leading to its proteasomal decay and exposing the miRNA to RNases.

1. INTRODUCTION

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, ~22 nucleotide (nt), non-coding RNAs. While small, these short RNAs are anything but insignificant. Indeed, miRNAs endogenously regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally across animals. There are hundreds of currently annotated animal miRNAs, many of which are broadly conserved across higher eukaryotes (Bartel, 2018). To exert their function, miRNAs associate with the effector protein Argonaute (AGO), which is directed to target messenger RNAs (mRNAs) at sites containing sequence complementarity to the miRNA referred to as “target sites”. Upon association, this complex will induce translational repression and/or mRNA destabilization, downregulating the target mRNA, in a mechanism called miRNA-mediated target repression (Lee et al., 1993; Wightman et al., 1993; Shabalina & Koonin, 2008). Given this, thousands of animal mRNAs contain at least one highly conserved miRNA target site, heavily implying an evolutionary selective advantage to efficient miRNA-mediated silencing (Friedman et al., 2009). In line with this, deletion of animal miRNA genes has been associated with many developmental, disease, and cognitive abnormalities across evolutionary backgrounds (Reinhart et al., 2003; Brennecke et al., 2003; Bartel, 2018). Thus, miRNAs act as “master regulators” of post-transcriptional gene regulation.

While much attention has been given to miRNA targeting and biogenesis, relatively little is known about how and why animal miRNAs are themselves directed for degradation (Treiber et al., 2018). RNAs are typically efficiently degraded if exposed to cellular ribonucleases (RNases), yet despite this, miRNAs are unusually stable compared to other classes of RNAs (Dölken et al., 2008; Kingston & Bartel, 2019; Eisen et al, 2020). This is mostly attributed to tight association with AGO, which normally protects the 3′ and 5′ termini from exposure to RNase (Lingel et al., 2003; Yan et al., 2003; Wang et al, 2008; Frank et al., 2010; Winter & Diederichs, 2011). This association confers exceptional stability to most miRNAs, yet there are several examples of comparatively short-lived miRNAs, indicating endogenous mechanisms regulating their selective decay (Bail et al., 2010; Król et al., 2010; Rissland et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2015; Marzi et al., 2016; Kingston & Bartel, 2019; Reichholf et al., 2019). The main mechanism largely driving this decay in animals is referred to as target-directed miRNA degradation (TDMD) (Cazalla et al., 2010; Ameres et al., 2010; Bitetti et al., 2018; Ghini et al., 2018; Kleaveland et al., 2018). Through this mechanism, certain RNAs will associate with the miRNA/AGO complex to “trigger” the decay of specific miRNAs. Recently, it was revealed that the ZSWIM8-ubiquitin ligase complex is a key contributor to this mechanism, where these TDMD “trigger” RNAs will recruit the complex to induce AGO polyubiquitination and subsequent degradation of AGO (Han et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020). Without AGO, the miRNA is quickly and efficiently degraded, leading to the observed miRNA degradation (Han et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020).

Here, we discuss the major findings related to ZSWIM8-dependent TDMD, a rapidly expanding field of study detailing a mechanism regulating animal miRNA stability. Given the fundamental role of miRNA-mediated target repression in development, this mechanism has revealed many functional insights into control of miRNA degradation in animal development and related molecular processes therein. While a relatively new field of study, this area has great potential for expansion of this mechanism into RNA-based therapeutics that both selectively and potently modulate miRNA abundance during development and disease.

2. MICRORNA BIOGENESIS AND FUNCTION

Maintaining tight control of gene expression is critical to cellular homeostasis, and as such, miRNAs themselves are delicately regulated through a series of stepwise maturation processes. Through these processes, the cell can quickly and efficiently produce miRNAs to regulate general processes, or in response to stimuli indicating developmental progression and/or stress. To do this, miRNAs are loaded into the effector protein AGO to carry out their function in downregulating target mRNAs, miRNA-mediated silencing. Therefore, tight regulation of miRNA maturation and stable association within the AGO are key to efficient silencing, the dysregulation of which can result in many co-associated morbidities (Bartel, 2018).

2.1. Canonical microRNA biogenesis

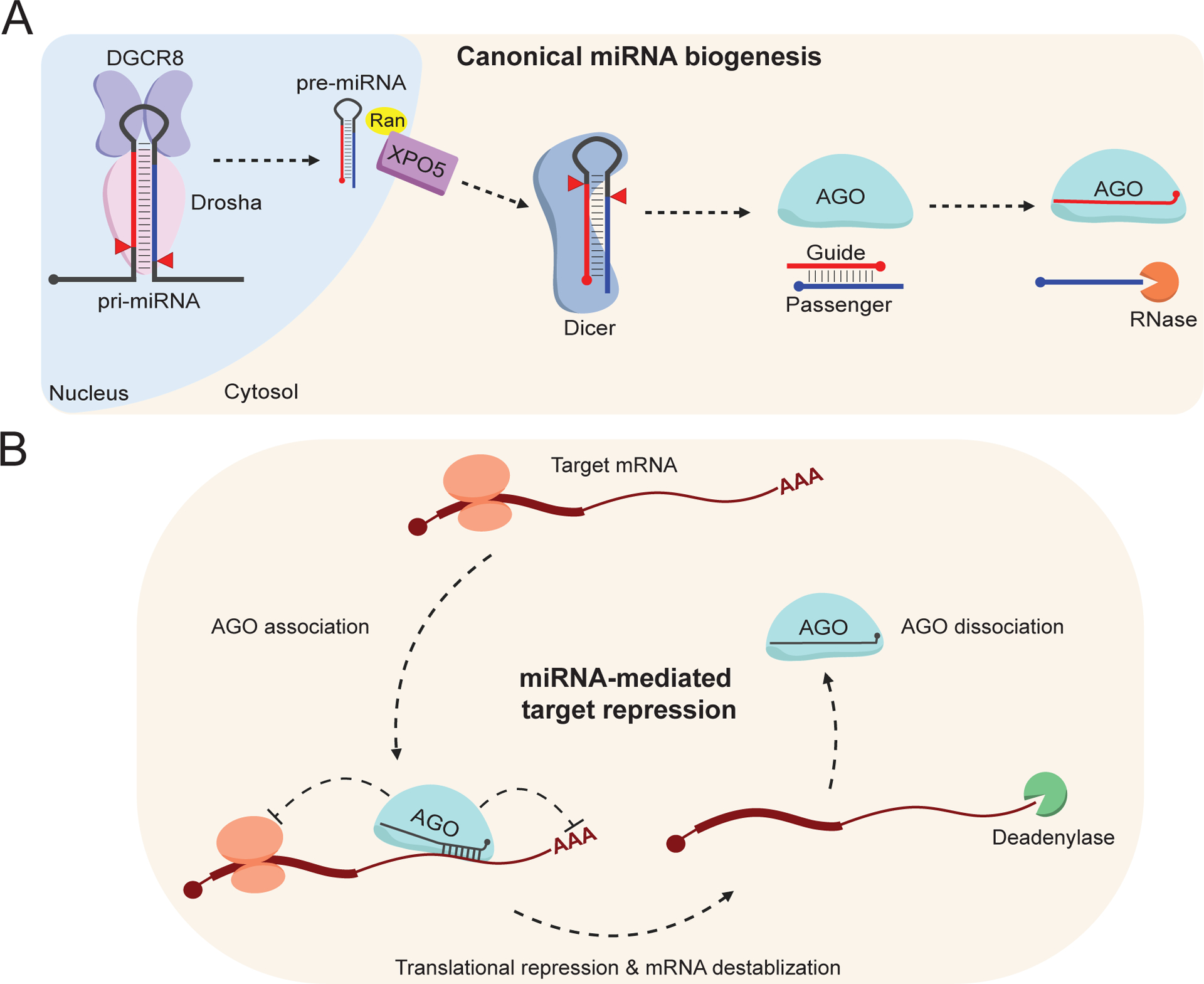

Canonically, miRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II within the nucleus as a long primary transcript referred to as the primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) (Figure 1A; Lee et al, 2002; Cai et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2004). These transcripts can encode a single, or several, miRNA genes in so-called polycistronic pri-miRNA clusters. The pri-miRNA forms a critical stem-loop secondary structure that can be bound by DGCR8 and Drosha, often referred to collectively as the Microprocessor, which will cleave the stem-loop to produce a short-hairpin RNA with a 3′-overhang called the precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) (Figure 1A; Lee et al., 2003). To continue the maturation process, pre-miRNA must be directed to the cytosol, where additional cytosol-localized factors can interact with the now ~60 nt pre-miRNA. To do this, pre-miRNAs interact with Exportin-5 (XPO5) and RAN-GTP to traverse the nuclear membrane and enter the cytosol (Figure 1A; Yi et al., 2003; Lund et al, 2004). Dicer, the next gatekeeper of miRNA biogenesis, will bind the pre-miRNA and cleave the terminal loop to produce a double-stranded miRNA duplex bearing mirrored 3′-overhangs on either strand (Figure 1A; Bernstein et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2004). This ~22 nt small-RNA duplex will interact with one of the Argonaute family (AGO1–4 in mammals) proteins, where a combination of structural, sequence, and thermodynamic properties will dictate the strand that will be preferentially loaded into AGO, the so-called mature miRNA “guide strand” (Figure 1A; Khvorova et al., 2003; Schwarz et al., 2003). The concomitant opposing strand, the “passenger” (or miRNA star) strand, quickly becomes destabilized and is subsequently degraded by cellular RNases (Figure 1A; Ha & Kim, 2014). Therefore, when annotating various miRNA families, the more abundant strand is designated as the guide, and the less abundant strand as the passenger. It is important to note, while outside the scope of this review, for each key step in miRNA biogenesis there are many well studied non-canonical processes that ultimately lead to an AGO-bound miRNA (Ha & Kim, 2014; Bartel, 2018; Shang et al., 2023).

Figure 1:

A) An illustration summarizing canonical animal miRNA biogenesis. Briefly, primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) is transcribed within the nucleus and cleaved by Drosha (pink) in complex with DGCR8 (purple). The precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) hairpin is exported out of the nucleus to the cytosol via XPO5 (violet), where the terminal loop is cleaved by Dicer (blue). AGO (cyan) selects a strand from the miRNA duplex, the more abundant species being referred to as the guide strand (red), whereas the less abundant is referred to as the passenger strand (blue line). The passenger strand is quickly degraded without a protein binding-partner.

B) An illustration detailing miRNA-mediated target repression. AGO-bound miRNAs (cyan, black) will associate with target RNAs (maroon) via sequence complementarity. Upon association, the complex will recruit additional factors to mediate translational repression, mRNA deadenylation, and mRNA destabilization. The complex can then disassociate from the target to induce multiple rounds of destabilization. This image was produced using Biorender.com.

2.2. miRNA-mediated target repression

It is only within the context of AGO that miRNAs finally become functional, where together, with additional proteins including GW182 (TNRC6) and others, the pair form the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) (Bartel, 2018). As the name suggests, the guide strand directs AGO to target mRNAs where sequence-complementarity between the guide and the target dictates targeting efficacy (Figure 1B; (Lee et al., 1993; Wightman et al., 1993; Shabalina & Koonin, 2008). Despite sequence-complementarity being key for target identification, miRNA target sites nearly always localize to the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of mRNAs (Jonas & Izaurralde, 2015). Following RISC association with a target mRNA, GW182 (TNRC6) will assist in the engagement of additional factors, such as the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex (Rehwinkel et al., 2005; Behm-Ansmant et al., 2006). These and other protein factors lead to translational repression and/or mRNA destabilization, silencing the target mRNA (Figure 1B). RISC will then dissociate from the target RNA, where it can repeat this cycle of target identification and silencing. Given this quality, a single short RNA loaded into AGO can cast a large shadow by inducing multiple rounds of post-transcriptional repression across a variety of target mRNAs (Figure 1B; Bartel, 2018). This mechanism is most often referred to as miRNA-mediated target repression which represents a key method for cells, organisms, and researchers alike to alter gene expression for a variety of purposes (Figure 1B; Bartel, 2018; Shang et al., 2023).

2.3. RISC alters RNA stability

2.3.1. AGO binding stabilizes miRNAs

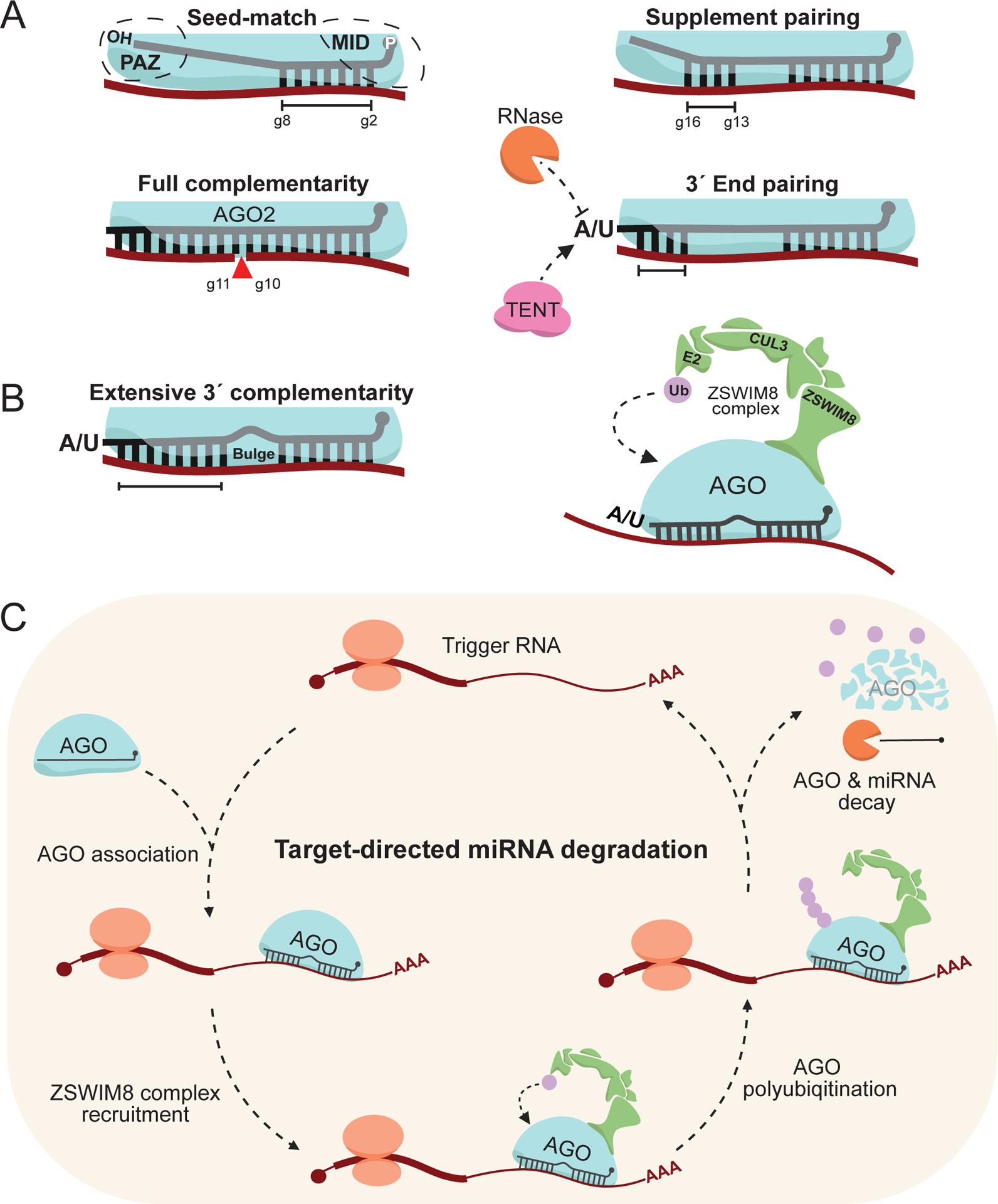

The half-lives of RNAs vary broadly by class (Dölken et al., 2008; Gantier et al., 2011; Kingston & Bartel, 2019; Eisen et al, 2020). Various features of RNAs can enhance stability and/or prevent turnover, such as the 5′ 7-methylguanosine (m7G) cap and poly-adenosine tail of mRNAs which confers enhanced stability by limiting the mRNAs susceptibility to RNases. Similarly, protein factors can act in trans to bind these features to render them inaccessible to the solvent. In comparison to mRNAs, which have an average half-life of several hours, the half-lives of miRNAs can exceed several days (Gantier et al., 2011). This feature is almost exclusively attributed to the tight association of miRNAs with AGO. Within AGO, the miRNA termini are shielded within separate domains, the middle (MID) domain burying the 5′ end, and the Piwi/AGO/Zwille (PAZ) domain shielding the 3′ end (Figure 2A; Lingel et al., 2003; Yan et al., 2003; Wang et al, 2008; Frank et al., 2010; Winter & Diederichs, 2011; Elkayam et al., 2012; Schirle & MacRae, 2012; Schirle et al., 2014). The MID binding pocket interaction with the 5′ nucleotide is quite stable, and therefore this nucleotide does not contribute to target engagement (Figure 2A). Overall, miRNA stability and functionality are reliant on stable association with AGO, conferring these small regulatory RNAs exceptionally long lives.

Figure 2:

A) MiRNA base-pairing modalities with target RNAs. Canonical seed-match (g2-g8), 3′ supplement base pairing (g13-g16, in addition to seed), siRNA-like full complementarity, and non-canonical 3′ end base pairing.

B) Extensive 3′ complementarity, with a central bulge separating seed-matching. This binding modality is charactisitic of and normally sufficient to induce ZSWIM8-dependent TDMD (green).

C) A model of the current ZSWIM8-dependent TDMD mechanism. Expression of a trigger RNA (maroon) bearing extensive complementarity to an AGO-loaded miRNA (cyan, black), upon AGO association, will direct it for turnover via recruitment of the ZSWIM8 ubiquitin ligase complex (green). ZSWIM8 will catalyse polyubiquitination (purple) of AGO, leading to its proteasomal decay, exposing the miRNA to RNases. The trigger RNA is preserved to induce multiple rounds of miRNA destabilization. This image was produced using Biorender.com.

2.3.2. MiRNA base-pairing modalities with target RNAs

While AGO stabilizes the bound miRNA, together, RISC will associate with and destabilize target mRNAs. There are many different experimentally identified binding modalities for RISC engaging with target mRNAs, but the mainstay between most of them is the “seed-match” requirement in animals (Bartel, 2018). The seed sequence is miRNA guide nucleotide 2–8 (g2-g8), the most conserved and functionally significant region, where a target RNA bearing a seed-matching site in the 3′ UTR is normally sufficient to predict regulation (Figure 2A; Friedman et al., 2009; Agarwal et al., 2015). Given this quality, miRNAs are classed into “families” containing identical seed sequences, and as such these family members redundantly regulate targets bearing a seed-match.

Though miRNA seed-matching is normally sufficient to regulate a target, there are additional binding modalities that can assist and/or augment targeting efficacy. The most well characterized is the “supplement” region (g13–16) that can enhance repression (Bartel, 2018), and possibly allow RISC to “unzip” target RNA secondary structure normally limiting seed accessibility (Figure 2A; Bartel, 2018; Kosek et al., 2023). In contrast to canonical miRNA target pairing, small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) bear full complementarity to the target and can achieve even more significant target repression by enabling AGO2 “slicer” activity, which will induce target cleavage between g10 and g11 (Figure 2A; Liu et al., 2004; Meister et al., 2004). Given this quality, synthetic miRNA target sequences can be engineered with full miRNA complementarity to induce greater target repression. In Drosophila melanogaster, siRNAs mainly partition into Ago2, while their miRNAs mostly only associate with Ago1 (Okamura et al., 2004; Förstemann et al., 2007; Ameres et al., 2010).

Another key binding modality is more puzzling, non-canonical targets that engage the miRNA 3′ end. Normally, the 3′ end is shielded within the PAZ domain, but certain targets can out-compete this interaction and expose the 3′ end to the solvent (Figure 2A; Sheu-Gruttadauria et al., 2019; Han & Mendell, 2023). Solvent-exposed ends are accessible to cellular factors, such as terminal nucleotidyltransferases (TENTs) that catalyse “tailing” of the 3′ end with non-templated nucleotides (most commonly adenosine and uridine), and RNases which can shorten or “trim” the 3′ end, mediating a process collectively referred to as target-directed tailing and trimming (TDTT) (Figure 2A; Ameres et al., 2010; Ameres & Zamore, 2013; Yashiro & Tomita, 2018; Ros et al., 2020; Yu & Kim, 2020; Han & Mendell, 2023). Various TENTs have been identified as post-transcriptional modifiers of mature miRNAs, though the extent to which individual classes of miRNAs are modified appears to be context specific (Katoh et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2014; Yashiro & Tomita, 2018; Yang et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2022; Han & Mendell, 2023). 3′ pairing often leads to a minimal contribution to target repression (Bartel, 2018); however, in the case for miR-27a, poor seed-matching can be compensated for by tailing via terminal uridyltransfterases (TUTs) to allow for greater target engagement, a phenomenon dubbed tail-U-mediated repression (TUMR) (Yang et al., 2019).

In essence, while there are generalized RISC binding modalities with target RNAs, some of which are not discussed here, each contributes a subtle yet distinct outcome that is ultimately context specific. Given the diverse array of miRNAs and target RNAs, we can expect that additional binding modes, rules, and functional consequences will be revealed in the coming years.

3. TARGET-DIRECTED MICRORNA DEGRADATION

Since the discovery of miRNAs, their regulatory role in mediating post-transcriptional gene silencing has, understandably, been the focus of most research. Dysregulation of miRNA-mediated target repression can lead to a variety of functional consequences, and as such, is often modulated throughout development and disease (Bartel, 2018). The increased, or decreased, expression of individual miRNAs can result in diverse phenotypes both subtle and fundamental (Bartel, 2018). Despite extensive study into miRNA-directed mRNA destabilization, relatively little is understood regarding how and why miRNAs themselves are directed for degradation. Indeed, several independent studies investigating miRNA stability from a variety of genetic backgrounds have found that while most miRNAs are long lived, there are subsets of miRNAs that are comparatively short-lived in various contexts (Król et al., 2010; Rissland et al., 2011; Marzi et al., 2016; Kingston & Bartel, 2019). These observations imply endogenous regulatory pathways that can modulate the stability of specific miRNAs. Here we discuss ZSWIM8-dependent target-directed miRNA degradation (TDMD), a burgeoning field of study detailing an endogenous mechanism that regulates the abundance of miRNAs across animal evolutionary backgrounds.

3.1. Identifying the ZSWIM8 ubiquitin ligase complex

3.1.1. Early insights into TDMD

The earliest fundamental insights into TDMD came nearly simultaneously in 2010, where the Steitz and Zamore groups detailed the same mechanism from distinct model systems (Cazalla et al., 2010; Ameres et al., 2010). The Steitz lab observed that the Herpesvirus saimiri-encoded HSUR1 non-coding RNA could, in addition to a seed-match and central bulge, extensively base-pair with the host-encoded miR-27a 3′ end (Figure 2B; Cazalla et al., 2010). Engagement with this site was sufficient to induce degradation of miR-27a, without destabilizing HSUR1. The Zamore lab similarly observed in both Drosophila and human cells, that extensive base-pairing between miRNAs and artificial targets could “trigger” destabilization of the interacting miRNA (Ameres et al., 2010). In addition, they noted the contributions of the central bulge, which presumably differentiated these non-canonical targets from siRNA-like base pairing which would result in efficient target repression. Hereafter, target RNAs that induce miRNA degradation will simply be referred to as “triggers”. Despite several functional studies identifying other viruses that encode triggers inducing TDMD (Libri et al., 2011; Marcinowski et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2013), mechanistic insights into this field largely stalled for several years.

3.1.2. Decoupling TDMD from tailing

A key piece of information that researchers investigated regarding the TDMD mechanism is the associated tailing of miRNAs during trigger engagement. (Figure 2B; Ameres et al., 2010; Baccarini, et al., 2011; De La Mata et al., 2015; Denzler et al., 2016). A broad tailing-mediated degradation pathway was an attractive model, as there are many examples of RNAs, even some miRNAs and pre-miRNAs, being directed for turnover over via tailing and subsequent degradation by RNases (Heo et al., 2009; Thornton et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2013; Faehnle et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2022). In 2018, the Bartel group reported that a highly conserved region within the long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) OIP5-AS1, renamed CYRANO in 2011, could extensively base-pair with and endogenously trigger degradation of miR-7 in mammals (Ulitsky et al., 2011; Kleaveland et al., 2018). This trigger bears the characteristic seed-match separated from extensive 3′ base-pairing by a short central bulge, which they noted likely inhibited AGO2 slicing (Figure 2B; Kleaveland et al., 2018). While an impressive finding on its own, what turned out to be the most impactful finding from this work was decoupling TDMD from tailing. Through a series of transient and stable loss-of-function experiments, the Bartel group identified that the TENT, Gld2 (the mouse ortholog of PAPD4/TENT2/TUT2), specifically induced tailing of miR-7 during engagement with CYRANO (Katoh et al., 2009; Mansur et al., 2016; Kleaveland et al., 2018). They observed that tailing of miR-7 was dispensable for CYRANO-induced miR-7 degradation, implying that an unknown regulatory mechanism was responsible for the degradation of miRNAs during engagement with triggers.

3.1.3. Screening for TDMD factors

The lessons learned from CYRANO set the stage for identifying the unknown regulatory factor(s) catalysing miR-7 TDMD. Consequently, in 2020, both the Bartel and Mendell groups reported using nearly identical means, an elegant CRISPR-Cas9 screen sensing miR-7 abundance with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter, to find the implied TDMD factors (Han et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020). Both groups identified a novel cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin ligase complex as the key mediator of CYRANO-induced miR-7 decay (Figure 2B; Han et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020). Within this complex they identified ZSWIM8 as the substrate-adapter protein that engages AGO, specifically during TDMD (Figure 2B). Mechanistically, it appears that during trigger engagement, a still poorly understood conformational change in AGO (Sheu-Gruttadauria et al., 2019) recruits the ZSWIM8 complex (Figure 2B). Following ZSWIM8 recognition, AGO is polyubiquitinated (primarily at lysine 493, K493, of human AGO2) (Figure 2C; Han et al., 2020), and subsequently degraded by the proteasome, exposing the now unprotected miRNA to RNases for decay (Figure 2C). Given that TDMD induces little to no trigger repression, this mechanism suggests that a single trigger can efficiently induce multiple rounds of miRNA turnover (Figure 2C; De La Mata et al., 2015; Ghini et al., 2018; Kleaveland et al., 2018; Han et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020). Thus, a key conundrum in regarding TDMD was solved, that to degrade a miRNA, destroy its Argonaute protein (Wu & Zamore, 2021)

3.2. Validated triggers and their functions

The discovery of ZSWIM8 and its regulatory role in mediating miR-7 TDMD has skyrocketed the ability for researchers to identify endogenous triggers. During its discovery, both the Bartel and Mendell groups identified a subset of miRNA guide strands (~30), but not their passengers, that were specifically stabilized following ZSWIM8 knockout in mammalian cells and tissues (Table 1; Han et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020). This observation is critical given TDMD ought to only affect the mature guide strand, not its co-transcribed passenger. Further, the Bartel lab highlighted the ZSWIM8 ortholog in both D. melanogaster S2 cells (Dorado, or simply Dora) and in C. elegans (Ebax1) (Shi et al., 2020). During loss-of-function of these orthologs, a diverse array of guide strands was enriched (~10 each), suggesting that ZSWIM8-dependent TDMD is a widespread phenomenon preserved throughout the evolution of animals (Table 1; Shi et al., 2020). The miRNAs that were sensitive to ZSWIM8 (or its ortholog) knockout were termed “ZSWIM8-sensitive” (Table 1). Each of these sensitive miRNAs is now a part of a short list of known endogenously regulated TDMD substrates, with each miRNA likely requiring a trigger to induce its decay. As such, the stage was set yet again to identify TDMD regulatory factors, with the spotlight now pointed at annotating these unknown triggers and defining their phenotypic consequences.

Table 1:

Currently annotated ZSWIM8 sensitive miRNAs

A list of miRNAs enriched/stabilized following ZSWIM8 (or its ortholog) loss of function (left), with sources demonstrating sensitivity (right). Known endogenous triggers regulating these miRNAs are provided in the middle column. It should be noted that each study listed used slightly different statistical and methodological means for defining ZSWIM8 sensitivity.

While each currently annotated trigger represents a key step in advancing our knowledge of the TDMD mechanism, it is easiest to discuss them based on their genetic origin. Even though the list of triggers has expanded greatly in recent years, the only known function for several triggers is the reduction of miRNA-mediated silencing, in which the canonical targets of these miRNAs are de-repressed following miRNA depletion. Despite this, there are potentially more elusive phenotypic consequences for these triggers that are yet to be identified. Still, unless clearly stated, it can be assumed that the only known functions for the triggers listed below is repression of miRNA-mediated silencing.

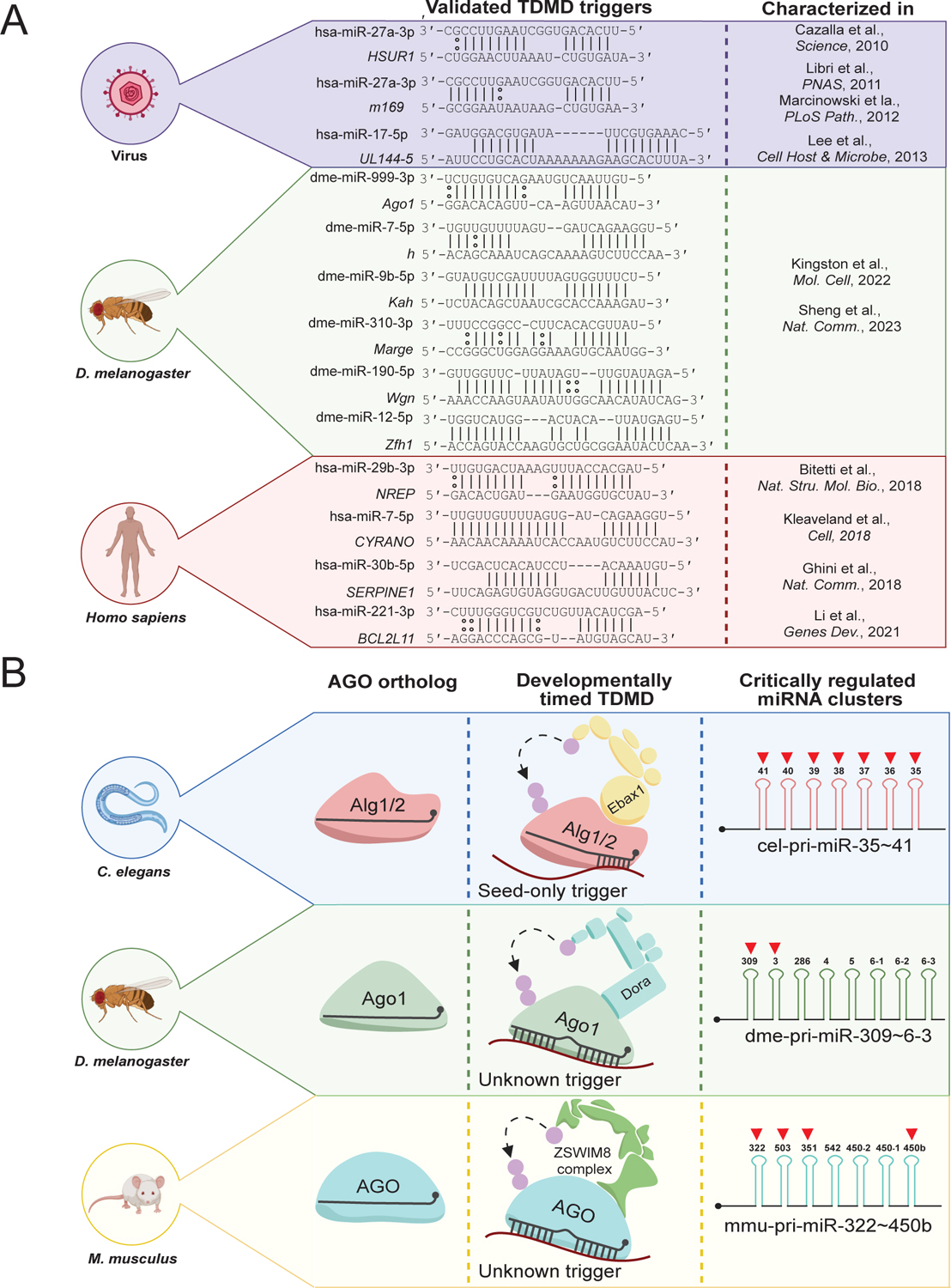

3.2.1. Virus-encoded triggers

The first foray into identifying naturally occurring triggers was in Herpesvirus saimiri, in which the H. saimiri U-rich RNA 1 (HSUR1) was found to induce decay of the host-encoded miR-27a (Figure 3A; Cazalla et al., 2010). Utilizing this case study, further investigations into virus-encoded triggers continued, this time in Murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV). Two independent groups identified the MCMV-encoded transcript m169 was sufficient to, again, degrade miR-27a (Libri et al., 2011; Marcinowski et al., 2012) and its family member miR-27b (Figure 3A; Marcinowski et al., 2012). This trigger appears to improve the virus life cycle, promoting viral replication. Shortly thereafter, a similar story was reported in Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), where the virus-encoded transcript UL144–5 triggered decay of the miR-17 family to enhance viral production (Figure 3A; Lee et al., 2013).

Figure 3:

A) A list of validated naturally occurring TDMD triggers, their genetic origins, affected miRNAs, trigger-miRNA base pairing, and the publications initially characterizing them.

B) A summary of developmentally timed TDMD in various animal models. C. elegans uses the AGO orthologs Alg1/2 and is directed for degradation via Ebax1. Most of the cel-miR-35 family (cel-miR-35–42) is derived from the same clustered transcript (cel-pri-miR-35~41) and is sharply degraded during worm development. D. melanogaster uses the Ago1 ortholog to bind most miRNAs and is directed for turnover via Dora. A portion of the dme-miR-3 family is derived from the dme-pri-miR-309~6–3 cluster, and their degradation by an unknown trigger is critical to fly embryo viability. Mus musculus uses Ago1-4 and is directed for turnover via ZSWIM8. Mmu-miR-322/503, derived from the mmu-pri-miR-322~450b transcript, degradation via an unknown trigger is critical to mouse growth. The ZSWIM8 (or its ortholog) sensitive miRNAs within these clusters are marked with red arrows. This image was produced using Biorender.com.

3.2.2. Drosophila melanogaster triggers

Very recently, the Bartel and Xie groups utilized independent means (discussed below in 3.2.4 Key methods for identification and validation) to identify several triggers regulating Dora-sensitive miRNAs in D. melanogaster-derived S2 cells (Kingston et al., 2022; Sheng et al., 2023). They each identified that the Ago1, h, Kah, Wgn, and Zfh1 mRNAs harboured triggers in their 3′ UTRs sufficient to induce decay of miR-999, miR-7, miR-9b, miR-190, and miR-12, respectively (Figure 3A; Kingston et al., 2022; Sheng et al., 2023). The Bartel group identified an additional trigger within the Marge lncRNA that induces decay of the miR-310 family in vivo, the loss of which results in disrupted embryonic cuticle development (Kingston et al., 2022). The Xie group focused on Ago1-induced degradation of miR-999 in vivo, in which deletion of this trigger resulted increased adult fly susceptibility to oxidative stress (Sheng et al., 2023).

3.2.3. Vertebrate triggers

The remaining annotated triggers are largely conserved in humans, mice, and other vertebrates alike. The first identified endogenously expressed trigger, the Nrep mRNA (the libra lncRNA in zebrafish), was found to coordinate TDMD in vertebrate neurons by triggering degradation of miR-29b (Figure 3A; Bitetti et al., 2018). Deletions of this trigger in both mouse and zebrafish models resulted in behavioural deficits, implicating TDMD broadly in animal cognition (Bitetti et al., 2018). CYRANO, the lncRNA that efficiently induces degradation of miR-7, is the most potent and well-studied example of a trigger to date (Figure 3A; Kleaveland et al., 2018). Probing of its physiological function identified its role in regulating the abundance of Cdr1as, a known neuronal circRNA, in the brain by limiting the ability of miR-7 to induce its degradation (Kleaveland et al., 2018). Despite this, knockout of the CYRANO trigger in mice yielded no clear phenotypic consequences, as the mice appeared otherwise normal (Kleaveland et al., 2018). Another study screened for endogenous transcripts that might induce TDMD and found that the Serpine1 mRNA could trigger degradation of miR-30b/c (Ghini et al., 2018). Finally, a highly conserved region within the 3′ UTR of BCL2L11, an mRNA encoding the potent tumor suppressor BIM, could efficiently trigger miR-221/222 decay (Figure 3A; Li et al., 2021). Interestingly, this study identified a trigger RNA cooperativity model, where encoded protein BIM and its transcript acting as a trigger could functionally cooperate to increase apoptosis in human cells (Li et al., 2021).

3.2.4. Key methods for identification and validation

Collectively, the above-mentioned triggers represent the first examples of naturally occurring transcripts that efficiently induce decay of specific miRNAs (Figure 3A). While the list grew slowly, the discovery of ZSWIM8 and its role in TDMD has propelled researchers’ ability to identify endogenous examples of potent triggers. Equally thorough and elegant experimentation was key to identifying these triggers and TDMD factors, and therefore highlighting some of the key molecular methods used to reach these conclusions is worth discussion.

Possibly the most fundamental method used in this field, and molecular biology as whole, is the utilization of CRISPR-Cas9 systems to quickly interrogate loss-of-function studies (Doudna & Charpentier, 2014; Manghwar et al., 2019). Indeed, one of the most straight-forward methods for observing the potency of a potential trigger is to simply knock out the trigger site and observe if there is specific elevation of the miRNA of interest. As discussed earlier, these systems can also be used in a naïve fashion, such as the CRISPR-Cas9 screen used to identify ZSWIM8, to identify unknown regulatory factors related to trigger efficacy (Han et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020). These systems have been utilized in cells and organisms alike to greatly assist in the identification of triggers.

In any case, the key readout when investigating triggers is quantitating a change in miRNA abundance. For this, the “old but gold” method of northern blotting has allowed for direct observation of miRNA change in abundance (Khandjia, 1986; Pall et al., 2007; Miller et al., 2018; Ye et al., 2019). This method provides a couple key benefits, a relatively quick experimental turnaround time, and a semi-quantitative means for observing RNA abundance (Ye et al., 2019). While a powerful tool, northern blotting is limited by its sensitivity in that only relatively abundant miRNAs are observable. To address this issue, small RNA sequencing (sRNA-seq) methods have been critical to probe the change in abundance of more lowly expressed miRNAs. While there are many methods, kits, and services available to generate “minimally biased” sRNA-seq libraries, most are still fraught with sequence or size biases (Hafner et al., 2011; Jayaprakash et al., 2011; Zhuang et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2019). The accurate quantification sequencing (AQ-seq) method has been a boon on the small RNA field, allowing for a truly minimally biased and highly quantitative means to observe a change in miRNA abundance (Kim et al., 2019). Using this method, researchers have been able to quantitate both the guide and passenger strands through sRNA-seq, to observe a specific alteration in guide strand abundance following loss of TDMD (Han et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2023). In this way, AQ-seq and its derivatives are arguably the gold standard for generating highly reliable and reproducible sRNA-seq libraries.

Aside from sequencing methods, a more classical combination of ectopic expression and mutational analyses have been key to validating trigger efficacy. Using these methods, investigators have been able to probe trigger potency and base pairing requirements of both naturally occurring and synthetic triggers (De La Mata et al., 2015; Ghini et al., 2018; Kleaveland et al., 2018; Li et al., 2021). However, it should be noted that one of the major determinants of trigger effectiveness is its abundance, and therefore overexpression may induce destabilization that is not reflective of endogenous regulation (Kingston et al., 2022).

Finally, we wish to highlight a few interesting tools that have been adapted recently to successfully identify endogenous triggers. There are several tools that utilize algorithmic prediction of triggers based on qualities of validated triggers (Ghini et al., 2018; Simeone et al., 2022; Kingston et al., 2022). A key example of this is the pipeline developed by the Bartel group to identify several Drosophila triggers, in which they screened for potential triggers within 3′ UTRs of mRNAs or in lncRNAs that could extensively base pair with known Dora-sensitive miRNAs (Kingston et al., 2022). This pipeline was quite successful but may be limited in its ability to identify triggers with non-canonical base pairing or localization, as it can only identify new triggers that bear similarity to previously validated examples. A compelling methods-based tool successfully used to find triggers is referred to as AGO crosslinking, ligation, and sequencing of hybrids (AGO-CLASH) (Helwak & Tollervey, 2014; Li et al., 2021). AGO-CLASH is a modified crosslinking immunoprecipitation method that UV crosslinks AGO during association with target RNAs, where an intermolecular ligation between the target RNA and miRNA is performed to generate a single chimeric (or hybrid) RNA. Following sequencing, the hybrid can be bioinformatically deconvoluted to identify AGO-bound sites and the associated miRNAs directing the AGO to that location (Helwak & Tollervey, 2014). Base-pairing predictions of the miRNA-target hybrid are performed to distinguish canonical miRNA targets from trigger-like base-pairing. Given this information, the Xie group has been utilizing this method to screen for potential triggers, having much success in significantly expanding the list of known endogenous triggers (Li et al., 2021; Sheng et al., 2023). While AGO-CLASH appears to be a powerful tool for identifying endogenous triggers, it is a laborious method with several limitations. Some limitations include low crosslinking efficiency of AGO to target RNAs, high sample input requirements, low miRNA-target intermolecular ligation efficiency, and spurious/transient hybrid formation (Helwak & Tollervey, 2014; Agarwal et al., 2015). In effect, while there are several ways to improve screening of endogenous triggers, each may be limited in its application and could be used in combination depending on the context.

3.3. Developmentally timed TDMD in animals

Subsets of animal miRNAs appear to be crucial for proper transition through developmental stages and overall viability (Bartel, 2018). Though the mechanism(s) behind these independent observations is largely unknown, and has often been attributed transcriptional changes, several studies have identified the sudden sequence-specific attenuation of certain miRNAs during development now known to be TDMD sensitive (Pek et al., 2009; Stoeckius et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2010; Bartel, 2018). Given the recent advances in defining the ZSWIM8-dependent TDMD pathway, various groups have been probing its contribution to these observations in several model organisms.

3.3.1. Caenorhabditis elegans

The first identified miRNAs were initially uncovered in the classic invertebrate model organism C. elegans, where lin-4 and let-7 were identified as small non-coding RNAs regulating proper worm development (Lee et al., 1993; Wightman et al., 1993). In C. elegans, miRNAs associate with the “Argonaute-like genes” (Alg) family proteins, primarily Alg1/2, to form the RISC and subsequently mediate silencing (Figure 3B; Grishok et al., 2001). During worm development it has been noted that during the embryo to larval stage 1 (EtoL1) transition, the miR-35 family members (miR-35–42, of which miR-35–41 are clustered within the same pri-miRNA transcript) quickly become attenuated (Stoeckius et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2010). Due to seed redundancy, deletion of each individual gene does not alter worm development, however deletion of all these miRNAs results in embryonic lethality (Alvarez-Saavedra & Horvitz, 2010). Interestingly, in 2020, the Bartel group reported that knockout of the C. Elegans ZSWIM8 ortholog (Ebax1) resulted in stabilization of several miR-35 family members (Shi et al., 2020). Shortly thereafter, the McJunkin group confirmed that the reduction of the miR-35 family during EtoL1 was through Ebax1-dependent decay (Donnelly et al., 2022). Puzzlingly, the miR-35 family have divergent 3′ ends, prompting these investigators to probe whether this decay mechanism required the extensive 3′ complementarity defined in other organisms. Introduction of miR-35 3′ end mutants did not alter their decay during EtoL1, suggesting that the miR-35 family is subjected to a seed-only TDMD mechanism, likely catalysed by a yet to be discovered seed-only trigger (Figure 3B; Donnelly et al., 2022).

3.3.2. Drosophila melanogaster

In D. melanogaster it has been noted that, unlike C. elegans, knockout of its ZSWIM8 ortholog (Dora) leads to embryonic lethality (Wang et al., 2013; Yamamoto et al., 2014). Given their previous findings detailing the stabilized miRNAs following loss of Dora, the Bartel group sought to delineate how Dora loss-of-function might induce this lethality via TDMD. By quantitating the change in miRNA abundance during various stages of embryogenesis, with or without Dora, the Bartel group identified that embryos without functional Dora specifically stabilized the miR-3 and miR-310 family (Kingston et al., 2022). They identified that deletion of a portion of the miR-3 locus (the clustered transcript for pri-miR-309~6–3, Figure 3B) partially rescued viability following Dora loss, linking TDMD to the embryonic viability of invertebrates (Kingston et al., 2022). Like in C. elegans, these miRNAs are derived from pri-miRNA clusters, suggesting that TDMD may aid in post-transcriptional regulation of clustered miRNAs (see section 3.4.1) that are otherwise expressed in tandem. A small detail not discussed also linking these studies are the seed sequence similarities of cel-miR-35 (CACCGGG) and dme-miR-3 (CACUGGG), raising the possibility that these miRNAs may be directed for turnover via similar seed-dependent regulatory mechanisms.

3.3.3. Mus musculus

Similar studies were conducted back-to-back, again by the Bartel and Mendell groups, detailing ZSWIM8 loss-of-function during mouse development (Jones et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2023). Each group independently reached the same conclusion, that ZSWIM8 loss-of-function mice displayed low birth weight, cyanosis, and significantly underdeveloped cardiopulmonary systems, resulting in perinatal lethality (Jones et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2023). Given the tissue-specific alterations observed, and the potential for tissue-specific expression of miRNAs and triggers alike, detailed examination of altered miRNA abundance was conducted in a variety of mouse tissues. Collectively, it was found that an additional ~30 miRNAs were sensitive to ZSWIM8 knockout, bringing the total number of known sensitive mammalian miRNAs to ~60 (Table 1; Jones et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2023). Still, despite AGO being the most well-characterized substrate of ZSWIM8, there still exists the likelihood that several of the observed phenotypes were due to disruptions in regulation of less well characterized targets of ZSWIM8. Indeed, a prior study in mice utilizing a conditional ZSWIM8 knockout found disrupted neuronal development and impaired cognition through a miRNA-independent mechanism (Wang et al., 2022). To address this possibility, the Mendell group rescued the low birthweight phenotype via deletion of miR-322/503 (derived from the pri-miR-322~450b cluster, Figure 3B), two ZSWIM8-sensitive miRNAs known to regulate mammalian growth (Jones et al., 2023). This observation demonstrated a key causal link between TDMD and mammalian development, likely marking the first of many investigations into this and other associated developmental abnormalities.

3.4. Emerging mechanisms regulated by TDMD

Given the exhaustive efforts of the many independent investigations discussed here, several obscure mechanisms regulated via TDMD have become clearer. Although TDMD ultimately resulting in limiting miRNA-mediated target repression, there exist several biochemical processes that appear to also depend on efficient TDMD. While far from all encompassing, we detail some of these emerging mechanisms below to inspire further investigation into other novel molecular processes dependent on TDMD.

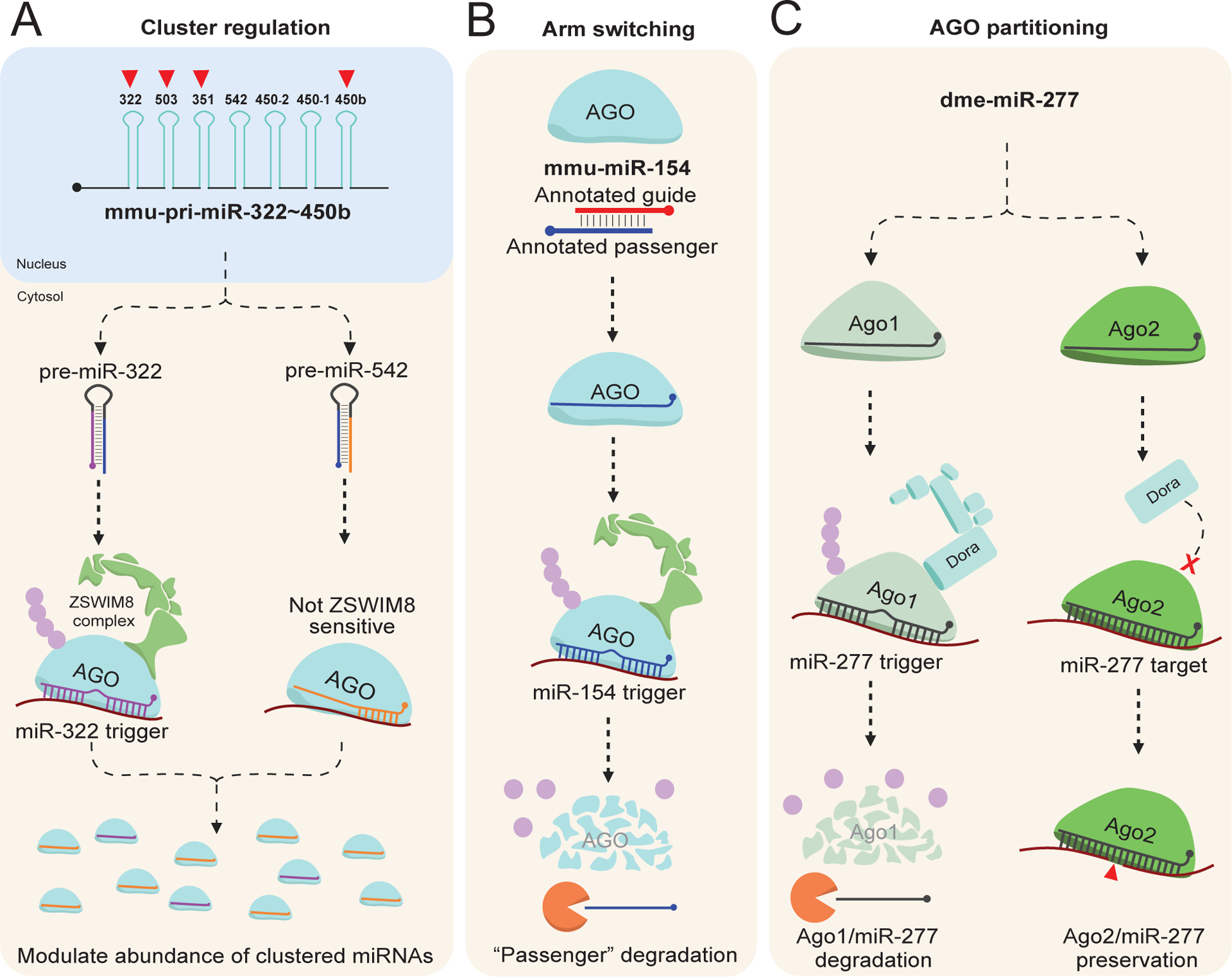

3.4.1. miRNA cluster regulation

As mentioned prior, miRNAs are initially transcribed into pri-miRNA which can contain a single or several distinct miRNA genes. As the list of ZSWIM8-sensitive miRNAs has grown in recent years it has become clear that, while only around 25% of all miRNAs are derived from clustered transcripts (Kabekkodu et al., 2018), around 63–72% of the mammalian ZSWIM8-sensitive miRNAs organize into clusters (Jones et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2023). Additionally, each of the known critically regulated miRNAs during animal development (the cel-miR-35 family, the dme-miR-3 family, and mmu-miR-322/503) localize within clusters (Figure 3B). In C. elegans the miR-35~41 cluster contains 7 of the 8 miR-35 family members, with miR-42 residing outside this transcript. Therefore, in this example, miR-35~41 cluster is directed for decay in tandem, essentially negating or limiting the impact of its transcription. In both D, melanogaster (the miR-3 family) and M. musculus (miR-322/503) the critically regulated miRNAs co-localize in the same cluster with non-ZSWIM8-sensitive miRNAs (Figure 3B). In this way, TDMD can be used post-transcriptionally alter the abundance of miRNAs derived from the same cluster, depressing the abundance of the sensitive while enriching the non-sensitive (Figure 4A; Jones et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2023). Considering the predominance of ZSWIM8-sensitive miRNAs in clusters, it is possible that one of the main regulatory mechanisms for TDMD is to simply alter the abundance of co-transcribed miRNAs (Figure 4A). Indeed, organisms could utilize this mechanism to tissue-specifically modulate miRNAs by instead regulating trigger expression instead of the pri-miRNA. However, until the triggers that regulate these and other clustered ZSWIM8-sensitive miRNAs are identified, further insight into this possibility is limited.

Figure 4:

Emerging mechanism regulated by TDMD. A) Clustered miRNAs. Many known ZSWIM8 sensitive miRNAs are derived from clustered transcripts. In some cases, only a few of the miRNAs within the transcript are ZSWIM8 sensitive, such as mmu-pri-miR-322~450b. Therefore, despite co-transcription, the relative abundance of each mature miRNA can be modulated via TDMD.

B) Arm switching. The annotated guide strand of miRNA is normally defined based on the more abundant isoform between the two co-transcribed strands. In the case of miR-154, the annotated passenger is normally efficiently loaded into AGO but is subsequently degraded via TDMD through a currently unknown trigger. Therefore, the tissue-specific examples detailing increases in miR-154 “passenger” strand abundance are likely due to repression of miR-154 TDMD.

C) AGO partitioning. Dme-miR-277 can efficiently load into both Ago1 and Ago2. However, the ZSWIM8 ortholog Dora can only direct degradation of Ago1. Therefore, TDMD of miR-277 via a currently unknown trigger increases its partitioning into Ago2, explaining earlier observations of this phenomenon. In this way, TDMD can regulate AGO ortholog partitioning in D. melanogaster. This image was produced using Biorender.com.

3.4.2. Arm switching

There is normally a steady-state abundance reached between miRNA guide and passenger strand that remains more-or-less constant, but this ratio can be altered in tissue-specific cases (Marco et al., 2010; Cloonan et al., 2011; Griffiths-Jones et al., 2011; Li et al., 2011). An interesting example of this rule is miR-154, in which it was found that, under certain conditions, the annotated guide strand would become less abundant in favor of the annotated passenger (Chiang et al., 2010; Cheng et al., 2012). This mechanism was termed “arm switching” and was largely assumed to take place during AGO strand selection, where certain conditions may prime AGO to select the passenger over the guide. Interestingly, the annotated passenger strand for miR-154 (as well as a handful of other miRNAs) is ZSWIM8-sensitive in mice (Jones et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2023). Mechanistically, it seems AGO normally efficiently loads the miR-154 passenger strand, but this complex is subject to TDMD by a currently unknown trigger, normally preventing its accumulation in cells (Figure 4B; Jones et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2023). Due to abundance being the main method for investigators to annotate guide and passenger strands, this would lead them to call the “real” guide the passenger and the “real” passenger the guide, leading to the puzzling observations mentioned prior. These findings implicate TDMD as one of the main drivers of arm switching, highlighting yet another more nuanced mechanism controlled via TDMD.

3.4.3. AGO partitioning

Early investigations into D. melanogaster miRNAs identified that, while generally miRNAs partition into Ago1 and siRNAs into Ago2, there are certain small RNAs that efficiently load into both Ago1 and Ago2 (Okamura et al., 2004; Förstemann et al., 2007; Ameres et al., 2010). In fact, one of the clearest examples of this phenomenon was detailed by Zamore’s group in 2007, where miR-277 was found to partition into either Ago1 or 2 but was primarily loaded into Ago2 (Figure 4C; Förstemann et al., 2007). The enrichment in Ago2 was, like arm switching, primarily attributed to Ago2 strand selection of miR-277 compared to Ago1. In 2020, Bartel’s group identified miR-277 as one of the miRNAs stabilized following loss of Dora (Shi et al., 2020), leading them to further investigate how Ago partitioning may contribute to TDMD or vice versa. In 2021, they found that the small RNAs loaded into Ago2 are insensitive to loss of Dora, suggesting that Dora is unable to recognize these complexes during target engagement (Kingston & Bartel, 2021). This makes mechanistic sense given that extensive target complementarity is normally sufficient to induce TDMD, and the Ago2 loaded siRNAs would primarily extensively (or completely) base pair with their targets. By only allowing Ago1 to be turned over via TDMD, cells can modulate the abundance of miRNAs while not affecting the siRNAs. Moreover, these observations explain the enrichment of miR-277 in Ago2, given that the Ago1 loaded miR-277 ought to be efficiently directed for degradation (Figure 4C; Kingston & Bartel, 2021). Therefore, in Drosophila there is additional layer of complexity to TDMD, in which TDMD can alter the Ago ortholog in which miRNAs are loaded. In mammals, it should be noted that AGO1–4 can be efficiently directed for turnover (Han et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020), but the efficiency in which each is degraded has not been thoroughly investigated.

Conclusion

Here, we have discussed many of the major findings related to ZSWIM8-dependent TDMD. This mechanism turns the generally accepted rules regarding miRNA-mediated target repression on its head, allowing certain targets, so-called TDMD triggers, to “strike back” and induce degradation of the associated miRNA (Wightman et al., 2018; Wu & Zamore, 2021; Han & Mendell, 2023). Currently, it appears that seed-matching in addition to extensive miRNA 3′ complementarity with a trigger will recruit the ZSWIM8 ubiquitin ligase complex, which will polyubiquitinate AGO, marking it and the loaded miRNA for degradation (Han et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020). Many such triggers have been identified, with several known and unknown triggers inducing a variety of phenotypes. Additionally, these findings have clarified many puzzling observations from past investigations (e.g. developmentally timed miRNA degradation, arm switching, AGO partitioning) while raising many new mechanistic questions related to TDMD (Donnelly et al., 2022; Kingston & Bartel, 2021; Kingston et al., 2022; Jones et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2023). Despite these promising findings, there is still much work to be done. Indeed, without identifying the triggers for the growing list of sensitive miRNAs, there exists little other way to probe TDMD specific phenotypic consequences and mechanisms therein. Consequently, the next frontier in TDMD will be the identification of the complete list of the trigger interactome across evolutionary backgrounds, requiring deep coordination and cooperative studies across many groups. To close this summation of ZSWIM8-dependent TDMD, we wish to discuss several possible directions for study that might prove fruitful in the coming years (Figure 5).

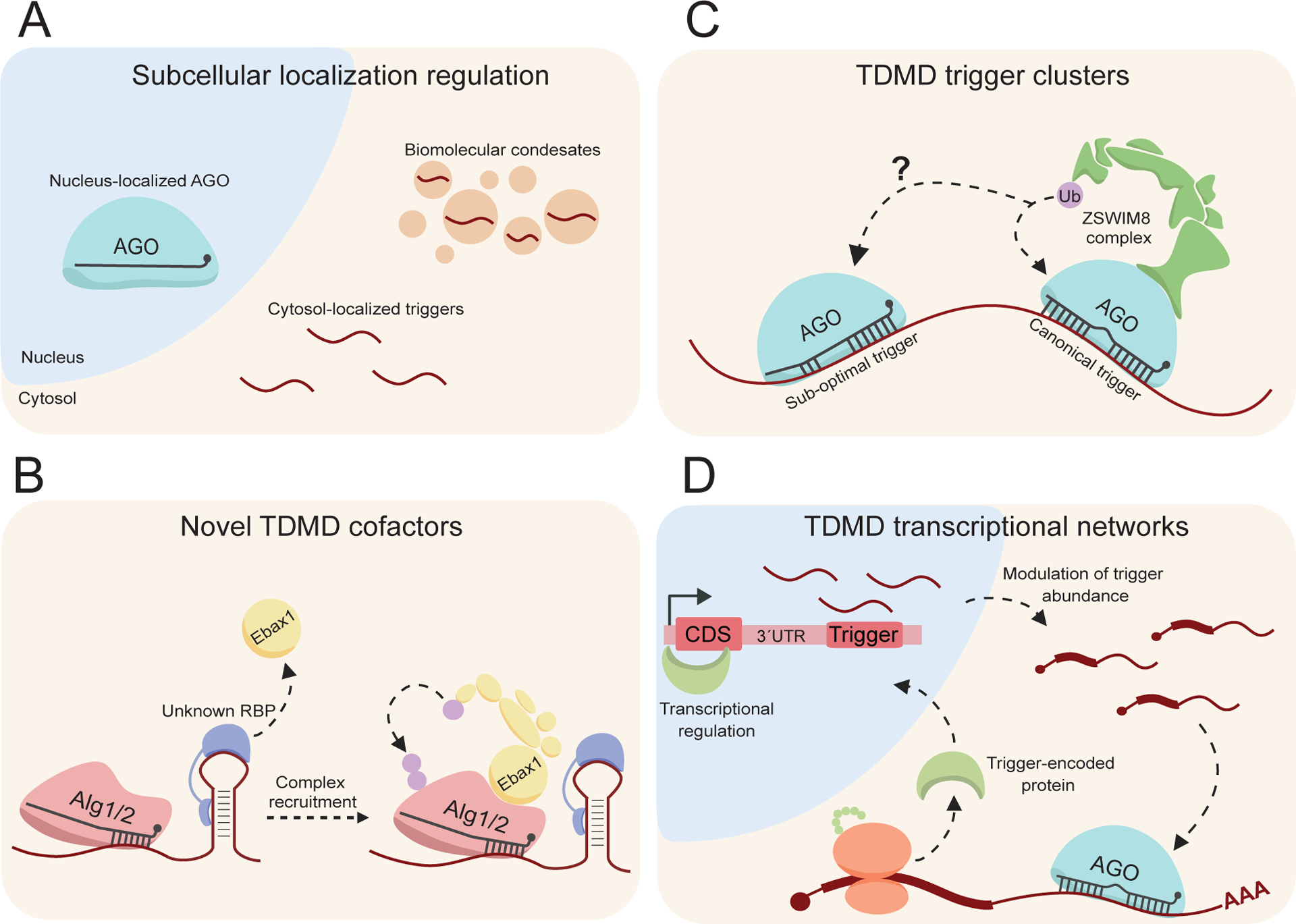

Figure 5:

Potential mechanisms that may reglate/be regulated by TDMD. A) Subcellular localization: canonical miRNA and/or TDMD factors preferentially localizing into organelles, or biomolecular condensates may alter TDMD efficacy and may explain some observations of altered TDMD efficiency. B) Novel TDMD cofactors: a mechanism in C. elegans differentiates the proposed seed-dependent trigger from targets. It is possible that a novel protein partner primes the seed-trigger by recruiting Ebax1, directing co-localized Alg1/2 for turnover. C) TDMD trigger clusters: as many ZSWIM8-sensitive miRNAs are derived from clusters, they may also be degraded in clusters. “Canonical” triggers may prime triggers to induce degradation of co-localized “sub-optimal” triggers, normally insufficient to induce degradation. D) TDMD trancriptional networks: trigger encoded proteins have been shown to cooperate prior, but whether any transcription factor encoded triggers regulate trigger transcription is yet to be determined. These transcription factors may modulate the abundance of the same trigger, or a completely unrelated trigger in a sort of transcriptional network. This image was produced using Biorender.com.

A key observation of the CYRANO trigger was that its endogenous efficacy of the full-length transcript was much greater than overexpression of just the trigger and its flanking regions (Kleaveland et al., 2018). This change in efficacy was quite dramatic, given the endogenous CYRANO knockout resulted in a ~40-fold increase in miR-7, but overexpression of the trigger and flanking region only resulted in a ~3-fold decrease in miR-7 (Kleaveland et al., 2018). In line with these observations, probing of the BCL2L11 trigger mechanism revealed that the highly conserved flanking regions bordering the trigger were necessary to induce miR-221/222 decay (Li et al., 2021). These findings suggest that there are additional elements within triggers that regulate their efficacy. A mechanism that may be related to this is subcellular localization of related TDMD and/or miRNA machinery into organelles (such as nucleus localized AGO) or into phase-separated biomolecular condensates (Figure 5A). In this way, efficacious localization of AGO, triggers, ZSWIM8, or still yet to be identified TDMD factors may prime endogenous triggers for enhanced TDMD (Figure 5A). Through a phase separated “TDMD body” mechanism, elements within triggers such as CYRANO might induce the formation of condensates in cis or in trans via novel protein partners. Such condensates may have a high concentration of TDMD related factors, allowing for the increased effectiveness of endogenous CYRANO compared to just an overexpressed portion (Figure 5A). Some of the major drivers for condensate formation are protein-protein interactions via intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) that can be nucleated via RNA scaffolds (Unfried & Ulitsky, 2022; Mattick et al., 2023). In agreement with this, ZSWIM8 is known to contain IDRs which may contribute to its regulation of certain proteins during brain development (Wang et al., 2022). In addition, it has been noted that a single trigger transcript can induce multiple rounds of turnover, suggesting that sub-stoichiometric mechanisms may underlie efficacy (De La Mata et al., 2015; Kleaveland et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2020). Further probing of the effects subcellular localization has on TDMD efficiency might provide clarity regarding where and how miRNAs are directed for turnover in cells.

Furthermore, there are other more obscure mechanisms that may regulate triggers. One such mechanism, highlighted in C. elegans, is the conundrum regarding the seed-dependent trigger for the miR-35 family (Donnelly et al., 2022). Given the seed-sufficiency of this trigger, there exists the need for some way for worms to differentiate miR-35 targets from the miR-35 trigger. Thus, a possible explanation for this trigger is a novel protein partner that primes the miR-35 trigger, potentially recruiting Ebax1 to co-localized Alg1/2 (Figure 5B). Alternatively, triggers may localize into “trigger clusters” in which canonical triggers may prime sub-optimal/seed triggers for degradation (Figure 5C), not dissimilar to cluster assistance observed in pri-miRNA biogenesis (Fang & Bartel, 2020). It should be noted that a study pre-dating discovery of ZSWIM8 utilized synthetic trigger clusters, in which several triggers in tandem reduced TDMD efficacy and induced target repression, though the extent to which these results would translate to endogenous triggers remains to be investigated (De La Mata et al., 2015).

Finally, many of the identified triggers localize to mRNAs. In BCL2L11, the encoded protein cooperates with the trigger within its transcript to enhance apoptosis (Figure 3A; Li et al., 2021). This cooperativity mechanism might extend to triggers and their expression levels as well, where the encoded proteins of triggers may induce transcription of the same or another trigger (Figure 5D). There exist two examples of transcription factor encoded triggers in Drosophila, Kah and Zfh1 (Figure 3A; Kingston et al., 2022; Sheng et al., 2023). To what extent these or other trigger-encoded proteins might regulate trigger expression remains to be determined.

Overall, ZSWIM8-dependent TDMD is a rapidly expanding field of study with implications in animal development, disease, and therapeutics alike.

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely thank our lab members for their encouraging discussions and thoughtful conversations during production of this review.

Funding Information

This work is supported by the funding from NIH (R35GM128753 and R01CA282812), American Cancer Society (RSG-21-118-01-RMC) and Florida Department of Health (21L03).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Nicholas M. Hiers, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, College of Medicine, UF Health Cancer Center

Tianqi Li, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, College of Medicine, UF Health Cancer Center.

Conner M. Traugot, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, College of Medicine, UF Health Cancer Center, UF Genetics Institute

Mingyi Xie, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, College of Medicine, UF Health Cancer Center, UF Genetics Institute.

References

- 1.Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW, & Bartel DP (2015). Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. eLife, 4. 10.7554/elife.05005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez-Saavedra E, & Horvitz HR (2010). Many Families of C. elegans MicroRNAs Are Not Essential for Development or Viability. Current Biology, 20(4), 367–373. 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ameres SL, Horwich MD, Hung J, Xu J, Ghildiyal M, Weng Z, & Zamore PD (2010). Target RNA–Directed trimming and tailing of small silencing RNAs. Science, 328(5985), 1534–1539. 10.1126/science.1187058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ameres SL, & Zamore PD (2013). Diversifying microRNA sequence and function. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 14(8), 475–488. 10.1038/nrm3611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baccarini A, Chauhan H, Gardner TJ, Jayaprakash A, Sachidanandam R, & Brown BD (2011). Kinetic Analysis Reveals the Fate of a MicroRNA following Target Regulation in Mammalian Cells. Current Biology, 21(5), 369–376. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.01.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bail S, Swerdel MR, Liu H, Jiao X, Goff LA, Hart RP, & Kiledjian M (2010). Differential regulation of microRNA stability. RNA, 16(5), 1032–1039. 10.1261/rna.1851510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartel DP (2018). Metazoan MicroRNAs. Cell, 173(1), 20–51. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behm‐Ansmant I, Rehwinkel J, Doerks T, Stark A, Bork P, & Izaurralde E (2006). mRNA degradation by miRNAs and GW182 requires both CCR4:NOT deadenylase and DCP1:DCP2 decapping complexes. Genes & Development, 20(14), 1885–1898. 10.1101/gad.1424106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, & Hannon GJ (2001). Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature, 409(6818), 363–366. 10.1038/35053110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bitetti A, Mallory AC, Golini E, Carrieri C, Gutiérrez HC, Perlas E, Pérez-Rico YA, Tocchini‐Valentini GP, Enright AJ, Norton W, Mandillo S, O’Carroll D, & Shkumatava A (2018). MicroRNA degradation by a conserved target RNA regulates animal behavior. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 25(3), 244–251. 10.1038/s41594-018-0032-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brennecke J, Hipfner DR, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. (2003) bantam encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell. 113(1), 25–36. Doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00231-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai X, Hagedorn CH, & Cullen BR (2004). Human microRNAs are processed from capped, polyadenylated transcripts that can also function as mRNAs. RNA, 10(12), 1957–1966. 10.1261/rna.7135204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cazalla D, Yario TA, & Steitz JA (2010). Down-Regulation of a Host MicroRNA by a Herpesvirus saimiri Noncoding RNA. Science, 328(5985), 1563–1566. 10.1126/science.1187197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang HC, Triboulet R, Thornton JE, & Gregory RI (2013). A role for the Perlman syndrome exonuclease Dis3l2 in the Lin28–let-7 pathway. Nature, 497(7448), 244–248. 10.1038/nature12119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng W, Chung I, Huang T, Chang S, Sun H, Tsai C, Liang M, Wong T, & Wang H (2012). YM500: a small RNA sequencing (smRNA-seq) database for microRNA research. Nucleic Acids Research, 41(D1), D285–D294. 10.1093/nar/gks1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiang H, Schoenfeld LW, Ruby JG, Auyeung VC, Spies N, Baek D, Johnston WK, Russ C, Luo S, Babiarz JE, Blelloch R, Schroth GP, Nusbaum C, & Bartel DP (2010). Mammalian microRNAs: experimental evaluation of novel and previously annotated genes. Genes & Development, 24(10), 992–1009. 10.1101/gad.1884710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cloonan N, Wani S, Xu Q, Gu J, Lea K, Heater SJ, Bárbácioru C, Steptoe AL, Martin HC, Nourbakhsh E, Krishnan KV, Gardiner B, Wang X, Nones K, Steen JA, Matigian N, Wood D, Kassahn KS, Waddell N, … Grimmond SM (2011). MicroRNAs and their isomiRs function cooperatively to target common biological pathways. Genome Biology, 12(12), R126. 10.1186/gb-2011-12-12-r126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De La Mata M, Gaidatzis D, Vitanescu M, Stadler M, Wentzel C, Scheiffele P, Filipowicz W, & Großhans H (2015). Potent degradation of neuronal mi RNA s induced by highly complementary targets. EMBO Reports, 16(4), 500–511. 10.15252/embr.201540078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denzler R, McGeary SE, Title AC, Agarwal V, Bartel DP, & Stoffel M (2016). Impact of MicroRNA levels, Target-Site complementarity, and cooperativity on competing endogenous RNA-Regulated gene expression. Molecular Cell, 64(3), 565–579. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.09.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dölken L, Ruzsics Z, Rädle B, Friedel CC, Zimmer R, Mages J, Hoffmann R, Dickinson P, Forster T, Ghazal P, & Koszinowski UH (2008). High-resolution gene expression profiling for simultaneous kinetic parameter analysis of RNA synthesis and decay. RNA, 14(9), 1959–1972. 10.1261/rna.1136108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donnelly BF, Yang B, Grimme AL, Vieux K, Liu C, Zhou L, & McJunkin K (2022). The developmentally timed decay of an essential microRNA family is seed-sequence dependent. Cell Reports, 40(6), 111154. 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doudna JA, & Charpentier E (2014). The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science, 346(6213). 10.1126/science.1258096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elkayam E, Kuhn C, Tocilj A, Haase AD, Greene EM, Hannon GJ, & Joshua‐Tor L (2012). The Structure of Human Argonaute-2 in Complex with miR-20a. Cell, 150(1), 100–110. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eisen TJ, Eichhorn SW, Subtelny AO, Lin KY, McGeary SE, Gupta S, & Bartel DP (2020). The dynamics of cytoplasmic mRNA metabolism. Molecular Cell, 77(4), 786–799.e10. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faehnle C, Walleshauser J, & Joshua‐Tor L (2014). Mechanism of Dis3l2 substrate recognition in the Lin28–let-7 pathway. Nature, 514(7521), 252–256. 10.1038/nature13553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fang W, & Bartel DP (2020). MicroRNA Clustering Assists Processing of Suboptimal MicroRNA Hairpins through the Action of the ERH Protein. Molecular Cell, 78(2), 289–302.e6. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Förstemann K, Horwich MD, Wee LM, Tomari Y, & Zamore PD (2007). Drosophila microRNAs Are Sorted into Functionally Distinct Argonaute Complexes after Production by Dicer-1. Cell, 130(2), 287–297. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frank F, Sonenberg N, & Nagar B (2010). Structural basis for 5′-nucleotide base-specific recognition of guide RNA by human AGO2. Nature, 465(7299), 818–822. 10.1038/nature09039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friedman RC, Farh KKH, Burge CB, & Bartel DP (2009). Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Research, 19(1), 92–105. 10.1101/gr.082701.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gantier MP, McCoy CE, Rusinova I, Saulep D, Wang D, Xu D, Irving AT, Behlke MA, Hertzog PJ, Mackay F, & Williams BR (2011). Analysis of microRNA turnover in mammalian cells following Dicer1 ablation. Nucleic Acids Research, 39(13), 5692–5703. 10.1093/nar/gkr148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghini F, Rubolino C, Climent M, Simeone I, Marzi MJ, & Nicassio F (2018). Endogenous transcripts control miRNA levels and activity in mammalian cells by target-directed miRNA degradation. Nature Communications, 9(1). 10.1038/s41467-018-05182-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffiths-Jones S, Hui JHL, De Marco A, & Ronshaugen M (2011). MicroRNA evolution by arm switching. EMBO Reports, 12(2), 172–177. 10.1038/embor.2010.191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grishok A, Pasquinelli AE, Conte D, Li N, Parrish S, Ha I, Baillie DL, Fire A, Ruvkun G, & Mello CC (2001). Genes and Mechanisms Related to RNA Interference Regulate Expression of the Small Temporal RNAs that Control C. elegans Developmental Timing. Cell, 106(1), 23–34. 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00431-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo Y, Li J, Elfenbein S, Ma Y, Zhong M, Qiu C, Ding Y, & Lü J (2015). Characterization of the mammalian miRNA turnover landscape. Nucleic Acids Research, 43(4), 2326–2341. 10.1093/nar/gkv057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ha M, & Kim VN (2014). Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 15(8), 509–524. 10.1038/nrm3838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hafner M, Renwick N, Brown M, Mihailović A, Holoch D, Lin C, Pena J, Nusbaum JD, Morozov P, Ludwig J, Ojo T, Luo S, Schroth GP, & Tuschl T (2011). RNA-ligase-dependent biases in miRNA representation in deep-sequenced small RNA cDNA libraries. RNA, 17(9), 1697–1712. 10.1261/rna.2799511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han J, & Mendell JT (2023). MicroRNA turnover: a tale of tailing, trimming, and targets. Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 48(1), 26–39. 10.1016/j.tibs.2022.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han J, LaVigne CA, Jones BT, Zhang H, Gillett FA, & Mendell JT (2020). A ubiquitin ligase mediates target-directed microRNA decay independently of tailing and trimming. Science, 370(6523). 10.1126/science.abc9546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Helwak A, & Tollervey D (2014). Mapping the miRNA interactome by cross-linking ligation and sequencing of hybrids (CLASH). Nature Protocols, 9(3), 711–728. 10.1038/nprot.2014.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heo I, Joo C, Kim Y, Ha M, Yoon M, Cho J, Yeom K, Han J, & Kim VN (2009). TUT4 in Concert with Lin28 Suppresses MicroRNA Biogenesis through Pre-MicroRNA Uridylation. Cell, 138(4), 696–708. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jayaprakash A, Jabado O, Brown BD, & Sachidanandam R (2011). Identification and remediation of biases in the activity of RNA ligases in small-RNA deep sequencing. Nucleic Acids Research, 39(21), e141. 10.1093/nar/gkr693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jonas S, & Izaurralde E (2015). Towards a molecular understanding of microRNA-mediated gene silencing. Nature Reviews Genetics, 16(7), 421–433. 10.1038/nrg3965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones BT, Han J, Zhang H, Hammer RE, Evers BM, Rakheja D, Acharya A, & Mendell JT (2023). Target-directed microRNA degradation regulates developmental microRNA expression and embryonic growth in mammals. Genes & Development, 37(13–14), 661–674. 10.1101/gad.350906.123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kabekkodu SP, Shukla V, Varghese VK, Souza JD, Chakrabarty S, & Satyamoorthy K (2018). Clustered miRNAs and their role in biological functions and diseases. Biological Reviews, 93(4), 1955–1986. 10.1111/brv.12428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katoh T, Sakaguchi Y, Miyauchi K, Suzuki T, Kashiwabara S, Baba T, & Suzuki T (2009). Selective stabilization of mammalian microRNAs by 3′ adenylation mediated by the cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase GLD-2. Genes & Development, 23(4), 433–438. 10.1101/gad.1761509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khandjian ÉW (1986). UV crosslinking of RNA to nylon membrane enhances hybridization signals. Molecular Biology Reports, 11(2), 107–115. 10.1007/bf00364822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khvorova A, Reynolds A, & Jayasena SD (2003). Functional sIRNAs and miRNAs exhibit strand bias. Cell, 115(2), 209–216. 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00801-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim H, Kim J, Kim KJ, Chang H, You K, & Kim VN (2019). Bias-minimized quantification of microRNA reveals widespread alternative processing and 3′ end modification. Nucleic Acids Research, 47(5), 2630–2640. 10.1093/nar/gky1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kingston ER, & Bartel DP (2019). Global analyses of the dynamics of mammalian microRNA metabolism. Genome Research, 29(11), 1777–1790. 10.1101/gr.251421.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kingston ER, & Bartel DP (2021). Ago2 protects Drosophila siRNAs and microRNAs from target-directed degradation, even in the absence of 2′-O-methylation. RNA, 27(6), 710–724. 10.1261/rna.078746.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kingston ER, Blodgett LW, & Bartel DP (2022). Endogenous transcripts direct microRNA degradation in Drosophila, and this targeted degradation is required for proper embryonic development. Molecular Cell, 82(20), 3872–3884.e9. 10.1016/j.molcel.2022.08.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kleaveland B, Shi CY, Stefano J, & Bartel DP (2018). A network of noncoding regulatory RNAs acts in the mammalian brain. Cell, 174(2), 350–362.e17. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kosek DJ, Banijamali E, Becker WF, Petzold K, & Andersson ER (2023). Efficient 3′-pairing renders microRNA targeting less sensitive to mRNA seed accessibility. Nucleic Acids Research, 51(20), 11162–11177. 10.1093/nar/gkad795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Król J, Busskamp V, Markiewicz I, Stadler M, Ribi S, Richter J, Duebel J, Bicker S, Fehling HJ, Schübeler D, Oertner TG, Schratt G, Bibel M, Roska B, & Filipowicz W (2010). Characterizing Light-Regulated retinal MicroRNAs reveals rapid turnover as a common property of neuronal MicroRNAs. Cell, 141(4), 618–631. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee M, Choi Y, Kim KJ, Jin H, Lim JY, Nguyen TA, Yang J, Jeong M, Giráldez AJ, Ye H, Patel DJ, & Kim VN (2014). Adenylation of maternally inherited MicroRNAs by Wispy. Molecular Cell, 56(5), 696–707. 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. (1993) The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 75(5), 843–54. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee S, Song J, Kim S, Kim J, Hong Y, Kim Y, Kim D, Baek D, & Ahn K (2013). Selective degradation of host MicroRNAs by an intergenic HCMV noncoding RNA accelerates virus production. Cell Host & Microbe, 13(6), 678–690. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi HI, Kim JK, Yim J, Lee J, Provost P, Rådmark O, Kim S, & Kim VN (2003). The nuclear Rnase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature, 425(6956), 415–419. 10.1038/nature01957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee Y, Jeon K, Lee J, Kim S, & Kim VN (2002). MicroRNA maturation: stepwise processing and subcellular localization. The EMBO Journal, 21(17), 4663–4670. 10.1093/emboj/cdf476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, Yeom KH, Lee S, Baek SH, & Kim VN (2004). MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. The EMBO Journal, 23(20), 4051–4060. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li L, Sheng P, Li T, Fields CJ, Hiers NM, Wang Y, Li J, Guardia CM, Licht JD, & Xie M (2021). Widespread microRNA degradation elements in target mRNAs can assist the encoded proteins. Genes & Development, 35(23–24), 1595–1609. 10.1101/gad.348874.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li S, Liao Y, Chan W, Ho M, Tsai K, Hu L, Lai C, Hsu C, & Lin W (2011). Interrogation of rabbit miRNAs and their isomiRs. Genomics, 98(6), 453–459. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Libri V, Helwak A, Miesen P, Santhakumar D, Borger JG, Kudla G, Grey F, Tollervey D, & Buck AH (2011). Murine cytomegalovirus encodes a miR-27 inhibitor disguised as a target. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(1), 279–284. 10.1073/pnas.1114204109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lingel A, Simon B, Izaurralde E, & Sattler M (2003). Structure and nucleic-acid binding of the Drosophila Argonaute 2 PAZ domain. Nature, 426(6965), 465–469. 10.1038/nature02123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lund E, Güttinger S, Calado Â, Dahlberg JE, & Kutay U (2004). Nuclear export of MicroRNA precursors. Science, 303(5654), 95–98. 10.1126/science.1090599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Manghwar H, Lindsey K, Zhang X, & Jin S (2019). CRISPR/CAS System: recent advances and future prospects for genome editing. Trends in Plant Science, 24(12), 1102–1125. 10.1016/j.tplants.2019.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mansur F, Ivshina M, Gu W, Schaevitz L, Stackpole EE, Gujja S, Edwards YJK, & Richter JD (2016). Gld2-catalyzed 3′ monoadenylation of miRNAs in the hippocampus has no detectable effect on their stability or on animal behavior. RNA, 22(10), 1492–1499. 10.1261/rna.056937.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marcinowski L, Tanguy M, Krmpotić A, Rädle B, Lisnić VJ, Tuddenham L, Chane-Woon-Ming B, Ruzsics Z, Erhard F, Benkartek C, Babić M, Zimmer R, Trgovcich J, Koszinowski UH, Jonjić S, Pfeffer S, & Dölken L (2012). Degradation of cellular MIR-27 by a novel, highly abundant viral transcript is important for efficient virus replication in vivo. PLOS Pathogens, 8(2), e1002510. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marco A, Hui JHL, Ronshaugen M, & Griffiths-Jones S (2010). Functional shifts in insect microRNA evolution. Genome Biology and Evolution, 2, 686–696. 10.1093/gbe/evq053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marzi MJ, Ghini F, Cerruti B, De Pretis S, Bonetti P, Giacomelli C, Gorski MM, Kress TR, Pelizzola M, Müller H, Amati B, & Nicassio F (2016). Degradation dynamics of microRNAs revealed by a novel pulse-chase approach. Genome Research, 26(4), 554–565. 10.1101/gr.198788.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mattick JS, Amaral P, Carninci P, Carpenter S, Chang HY, Chen L, Chen R, Dean C, Dinger ME, Fitzgerald KA, Gingeras T, Guttman M, Hirose T, Huarte M, Johnson R, Kanduri C, Kapranov P, Lawrence JB, Lee JT, … Wu M (2023). Long non-coding RNAs: definitions, functions, challenges and recommendations. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 24(6), 430–447. 10.1038/s41580-022-00566-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meister G, Landthaler M, Patkaniowska A, Dorsett Y, Teng G, & Tuschl T (2004). Human argonaute2 mediates RNA cleavage targeted by miRNAs and SIRNAs. Molecular Cell, 15(2), 185–197. 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Miller B, Wei T, Fields CJ, Sheng P, & Xie M (2018). Near-infrared fluorescent northern blot. RNA, 24(12), 1871–1877. 10.1261/rna.068213.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Okamura K, Ishizuka A, Siomi H, & Siomi MC (2004). Distinct roles for Argonaute proteins in small RNA-directed RNA cleavage pathways. Genes & Development, 18(14), 1655–1666. 10.1101/gad.1210204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pall GS, Codony-Servat C, Byrne J, Ritchie L, & Hamilton AJ (2007). Carbodiimide-mediated cross-linking of RNA to nylon membranes improves the detection of siRNA, miRNA and piRNA by northern blot. Nucleic Acids Research, 35(8), e60. 10.1093/nar/gkm112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pek JW, Lim AK, & Kai T (2009). Drosophila Maelstrom ensures proper germline stem cell lineage differentiation by repressing microRNA-7. Developmental Cell, 17(3), 417–424. 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rehwinkel J, Behm‐Ansmant I, Gatfield D, & Izaurralde E (2005). A crucial role for GW182 and the DCP1:DCP2 decapping complex in miRNA-mediated gene silencing. RNA, 11(11), 1640–1647. 10.1261/rna.2191905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Reichholf B, Herzog VA, Fasching N, Manzenreither RA, Sowemimo I, & Ameres SL (2019). Time-Resolved Small RNA Sequencing Unravels the Molecular Principles of MicroRNA Homeostasis. Molecular Cell, 75(4), 756–768.e7. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reinhart B, Slack F, Basson M (2000) The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature, 403, 901–906. 10.1038/35002607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rissland OS, Hong S, & Bartel DP (2011). MicroRNA destabilization enables dynamic regulation of the MIR-16 family in response to Cell-Cycle changes. Molecular Cell, 43(6), 993–1004. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ros XB, Yang A, & Gu S (2020). IsomiRs: Expanding the miRNA repression toolbox beyond the seed. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Gene Regulatory Mechanisms, 1863(4), 194373. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2019.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]