Abstract

N1-methyladenosine (m1A) is a widespread modification in all eukaryotic, many archaeal, and some bacterial tRNAs. m1A is generally located in the T loop of cytosolic tRNA and between the acceptor and D stems of mitochondrial tRNAs; it is involved in the tertiary interaction that stabilizes tRNA. Human tRNA m1A levels are dynamically regulated that fine-tune translation and can also serve as biomarkers for infectious disease. Although many methods have been used to measure m1A, a PCR method to assess m1A levels quantitatively in specific tRNAs has been lacking. Here we develop a templated-ligation followed by a qPCR method (TL-qPCR) that measures m1A levels in target tRNAs. Our method uses the SplintR ligase that efficiently ligates two tRNA complementary DNA oligonucleotides using tRNA as the template, followed by qPCR using the ligation product as the template. m1A interferes with the ligation in specific ways, allowing for the quantitative assessment of m1A levels using subnanogram amounts of total RNA. We identify the features of specificity and quantitation for m1A-modified model RNAs and apply these to total RNA samples from human cells. Our method enables easy access to study the dynamics and function of this pervasive tRNA modification.

Keywords: 1-methyladenosine (m1A), SplintR ligase, real-time PCR (qPCR), tRNA, template ligation

INTRODUCTION

N1-methyladenosine (m1A) is among the most abundant eukaryotic RNA modifications present in tRNA, rRNA, and mRNA. In humans, m1A is present in all cytosolic tRNA at position 58 (m1A58), in 15/22 mitochondrial tRNAs at position 9 (m1A9), and in mRNA (Clark et al. 2016; Dominissini et al. 2016; Li et al. 2016; Oerum et al. 2017; Suzuki et al. 2020; Xiong et al. 2023). In tRNA, m1A plays a role in its stability and in translational fine-tuning (Liu et al. 2016; Zhang and Jia 2018; Xiong et al. 2023) and has other functions (Oerum et al. 2017). As exemplars, m1A58 in cytosolic tRNALys(UUU), the essential RNA primer for HIV replication, can affect the reverse transcription (RT) fidelity and efficacy in HIV-1 infections (Auxilien et al. 1999). m1A58 in yeast tRNAiMet is required for its maturation and stability (Anderson et al. 1998). m1A9 of mitochondrial tRNAs is crucial for the correct folding such as in human mitochondrial tRNALys (Helm et al. 1998, 1999) and binding to elongation factors (Sakurai et al. 2001, 2005). m1A58 can also be reversed by three human eraser enzymes (Liu et al. 2016; Wei et al. 2018; Chen et al. 2019). m1A modification levels in specific tRNAs can be used as biomarkers for clinical prognosis, such as the development of COVID-19 severity (Katanski et al. 2022). Thus, the ability to quantify m1A modification rapidly and quantitatively in individual tRNA would be a valuable tool for mechanistic studies and diagnostic applications.

m1A modifications in RNA are commonly measured using mass spectrometry (MS), thin layer chromatography (TLC), or reverse transcription (RT). LC–MS and TLC methods generally measure the total m1A levels in bulk RNA; an individual tRNA m1A level can be measured after its isolation from bulk RNA (Suzuki and Suzuki 2014; Suzuki et al. 2020), which can be laborious, time consuming, and requires a large amount of material. RT measures m1A in individual tRNA through an m1A-induced stop in primer extension using low processive reverse transcriptases, which can be quantified by gel electrophoresis (Saikia et al. 2010; Clark et al. 2016). The RT method can also be used in high-throughput sequencing by quantifying the “mutated” and/or “stopped” reads at the tRNA m1A site induced by the readthrough of the m1A nucleotide by high processive reverse transcriptases. Mutational profiling with sequencing (MaP-seq) has been widely used to study m1A and multiple other modifications in RNA (Hauenschild et al. 2015; Clark et al. 2016; Zubradt et al. 2017). Although powerful, sequencing of tRNA is still slow to implement, expensive, and requires tens of nanograms of the input RNA.

Here, we describe a templated-ligation and quantitative PCR (qPCR) method to quantify m1A modification at single base resolution. qPCR is a routine and high-sensitivity method to study specific RNA properties. For quantitation, the RNA needs to be converted into cDNA using reverse transcriptase (RT-qPCR), or the RNA is used as the template to ligate two DNA oligonucleotides followed by PCR of the ligation product (Jin et al. 2016; Krzywkowski and Nilsson 2017; Yeakley et al. 2017). Because of the high extent of its modifications and structure, RT of tRNA is generally not sufficiently robust for RT-qPCR measurements. Furthermore, our goal is to target m1A modification at specific sites which may not have cDNA signatures that can be readily distinguished by qPCR. We therefore adapted a templated-ligation (TL-qPCR) approach using the highly efficient SplintR ligase, which was first used for miRNA studies (Jin et al. 2016; Krzywkowski and Nilsson 2017) and m6A modification detection in mRNAs (Xiao et al. 2018). We show that SplintR ligation works well for tRNA with subnanogram amounts of total RNA. More importantly, we develop this method for the new application to quantify the levels of m1A modification in specific tRNA in total RNA samples.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Principles of templated-ligation qPCR (TL-qPCR) assessment of m1A modification

tRNA is the most abundant RNA species in a total RNA sample by molarity. tRNA is also extensively modified with over 100 various modifications in three kingdoms of life. Current methods of detecting tRNAs and tRNA modifications include LC/MS (Suzuki and Suzuki 2014; Zhang et al. 2022), northern blot (Zhang et al. 2020; Khalique et al. 2022), next-generation sequencing (Cozen et al. 2015; Zheng et al. 2015; Clark et al. 2016), and end-ligation-based qPCR (Honda et al. 2015b). A SplintR ligation-based qPCR method has been developed to detect and quantify microRNA (miRNA) (Jin et al. 2016; Krzywkowski and Nilsson 2017). This method relies on splint ligation by the SplintR ligase using miRNA as the template. The ligation efficiency of template splint ligation by SplintR is very high, in contrast to previous methods using T4 RNA ligase 2 or T4 DNA ligase. In addition, the ligation efficiency of SplintR is negligible without the template. Thus, the ligation efficiency is proportional to the abundance of the miRNA.

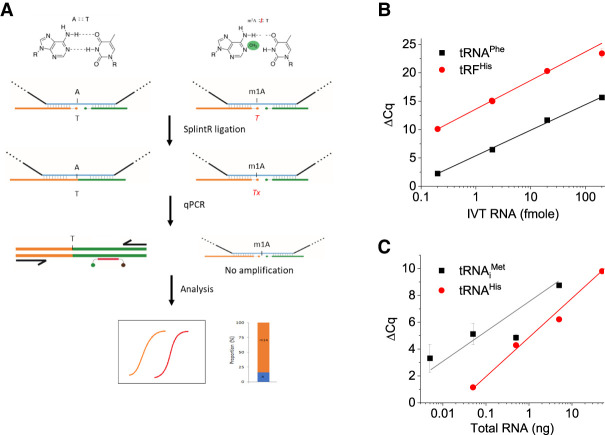

We took advantage of the SplintR ligation selectivity and developed a templated-ligation followed by qPCR assay for the detection and quantitation of m1A modification in tRNA (Fig. 1A). A previous method termed “SELECT” for m6A modification detection relies on the ability of m6A to inhibit both RT and splint ligation (Xiao et al. 2018). We reasoned that the methyl group at the N1 position of m1A affects the base-pairing between A and T, which may block the template splint ligation by SplintR and may be sufficient to distinguish A from m1A without RT. We designed two pairs of linker oligos that bind to the tRNA template near or far away from the m1A site. For the linker oligos near the modification site, the 5′ end of the upstream linker (5′ linker, 5lkr) has a phosphorylated T that binds to the complementary template containing A or m1A and a PCR primer-binding site. The downstream linker (3′ linker, 3lkr) has a fluorescent probe binding site and a PCR primer-binding site. To examine the feasibility of our method at the m1A site, we also included an optional AlkB demethylase treatment (Cozen et al. 2015; Zheng et al. 2015) step for the same sample that converts m1A to A. After SplintR ligation, the amount of ligated product can be detected by qPCR with fluorescent probes. The m1A modification fraction can be calculated using Equation 1 or 2 (see below) based on the qPCR threshold (Cq) values of the two SplintR ligation samples using linker oligos that bind to the tRNA near or away from the m1A site.

FIGURE 1.

TL-qPCR schematics and quantitative and sensitive detection of synthetic and biological tRNAs. (A) The basic design of measuring m1A in tRNA. The 5 linkers (5lkrT) with phosphorylated T at the 5′ end binds to complementary RNA template containing A or m1A at the same position. SplintR ligase ligates the 5lkrT linker and the 3′ linker at the joint position where the T pairs with A, but not with m1A. The ligated 5lkrT product is then used as template in qPCR using fluorescent probes. Comparing the difference of Cq value from A and m1A after normalization to controls, the m1A levels in the RNA sample are obtained. (B) Detection of model tRNA. ΔCq value between RNA sample and water control using 0.2–200 fmol in vitro transcript of yeast tRNAPhe (black) or a synthetic human tRNAHis fragment (red) using the 5lkrT linker in ligation. ΔCq values have a nice linear correlation with the log values of input amounts. (C) Detection of human tRNAiMet and tRNAHis in HEK293T total RNA. ΔCq value between RNA sample and water control. tRNAiMet or tRNAHis is still detectable at 5 or 50 pg total RNA input, respectively.

To test the sensitivity of the TL-qPCR method for the quantification of small RNAs in the absence of m1A modification, we used the in vitro transcript of yeast tRNAPhe, a synthetic RNA oligonucleotide corresponding to the human 5′ tRNAHis fragment (Martinez et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2018), and tRNAiMet in total human RNA. The ΔCq value between the RNA sample and water control of the two unmodified RNAs was proportional to the input amount of 0.2–200 fmol (Fig. 1B). Using the human tRFHis oligos and probes, we obtained a quantitative relationship of tRNAHis and tRNAiMet in total human RNA (Fig. 1C), and detected tRNAiMet in as little as 5 pg HEK293T total RNA input. These results validate the principle of our TL-qPCR design for the quantitative measurements of native tRNA.

TL-qPCR quantitation of m1A in synthetic oligonucleotides: optimization of linker oligo end sequence, position, and SplintR ligation temperature

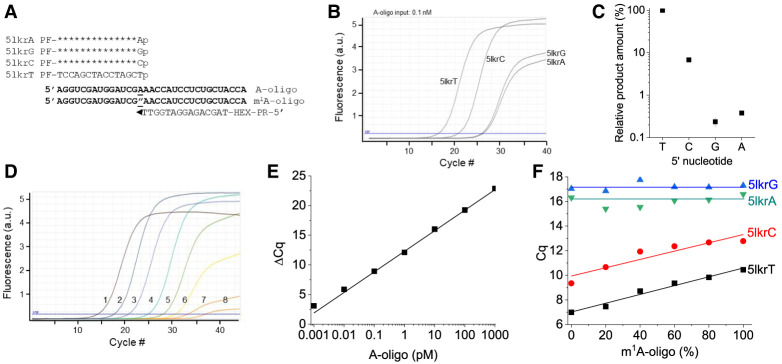

To examine the quantitative nature of our TL-qPCR method for m1A, we applied it to synthetic RNA oligos that have identical sequences of the m1A58 surrounding region of human tRNAiMet. First, we tested whether 1 nt mismatch at the ligation site affected the TL-qPCR product amount, and by inference, template splint ligation efficiency using unmodified RNA oligo. We designed four different 5′ linker oligos with T, C, G, or A at the 5′ end (Fig. 2A). The TL-qPCR profile showed that a 1 nt mismatch was sufficient to very significantly suppress the template splint ligation by SplintR (Fig. 2B). The relative amounts of PCR product for C, G and A-ending 5′ linker oligos were <10% compared to the T-ending 5′ linker, with C, G, and A-ending mismatched linker oligos at the level of 6.9%, 0.2%, 0.3% of the T-ending linker, respectively (Fig. 2C). This result demonstrates that a 1 nt mismatch can reduce the template splint ligation significantly, as expected. These results are crucial for our TL-qPCR strategy since it is based on the impaired base-pairing between m1A and T at the modification site. Next, we tested whether our method could quantify the abundance of the templated ligated product by varying the input amount of the RNA oligo. The qPCR amplification profile of the serial dilution of the unmodified oligo showed that the Cq values increased proportionally as the input amount was reduced (Fig. 2D). The standard curve of the serial diluted samples showed an excellent linear correlation between the Cq value and the RNA oligo input (R2= 0.974, Fig. 2E). This result demonstrates that our method can quantitatively measure the template splint ligated product.

FIGURE 2.

TL-qPCR on human tRNAiMet mimicking RNA oligonucleotides. (A) The oligos and linkers used in SplintR ligation for tRNAiMet-m1A58. A oligo and m1A oligo: two RNA oligos containing A or m1A-modified nucleotide (indicated with ″ according to conventional RNA modification nomenclature) as underlined. PF and PR: primer-binding site for PCR. HEX: qPCR fluorescent probe binding site. (B) qPCR curves and (C) relative PCR product amounts of the four linkers 5lkrT/C/G/A in the templated SplintR ligation using 0.1 nM A oligo as input. (D) Amplification curves and (E) standard ΔCq curve of the dilution series of the A oligo input (#1 to #7 for 10× serial dilution from 1 nM to 1 fM) with H2O as a negative control (#8), generated with the linker 5lkrT in the SplintR ligation. (F) Standard Cq curves of 1 nM total m1A/A oligo mixture inputs in the SplintR ligation using the linker 5lkrT.

To investigate the quantitative nature of TL-qPCR for m1A levels, we varied the ratio of the synthetic m1A-modified oligo and unmodified oligo in the input and performed TL-qPCR with 5′ linker oligos that have T, C, G, or A at the 5′ end. Cq values obtained using T-ending 5′ linker oligo showed the best linear correlation (R2= 0.977, ΔCq of one- to twofold) with the ratio of m1A RNA oligo compared to other 5′ linker oligos (Fig. 2F). However, our sample with supposedly 100% m1A oligo still showed a low amount of TL-qPCR product, and a low level of ligation product was detectable using this oligo alone (Supplemental Fig. S1A). This result may be derived either from incomplete suppression of ligation by m1A modification, the residual presence of unmodified oligo, or a m1A-to-m6A migration during oligo synthesis (Engel 1975; Liu et al. 2022). ESI-MS showed that the commercial m1A oligo did not contain unmodified oligo but was consistent with the presence of m6A (Supplemental Fig. S1B). From our TL-qPCR results, we estimate ∼10% m1A-to-m6A conversion during the commercial m1A-oligo synthesis, whereas this conversion was negligible during our TL-qPCR procedure (see Fig. 3 result below). Nevertheless, these results demonstrate that our TL-qPCR method can quantify the m1A modification fraction in model oligos.

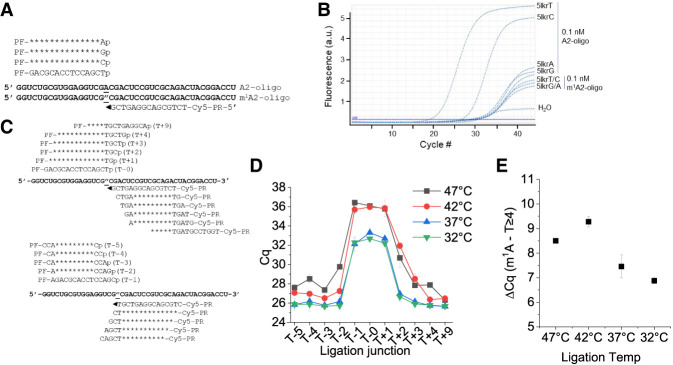

FIGURE 3.

Optimization of TL-qPCR efficiency regarding m1A proximity and ligation temperature. (A) Oligonucleotides used and ligation oligo design. (B) Amplification curves of linker 5lkrT/C/G/A in A and m1A oligo in ligation. (C) Ligation oligo design at varying ligation sites away from the m1A site. (D) Cq plots as a function of ligation oligos with ligation sites at m1A (T + 0) or progressively away from the m1A site. (E) ΔCq values between the m1A site and control site (using average Cq values of sites ≥4 nt away from the m1A site) under different template splint ligation temperatures.

We further investigated the context dependence of m1A effects using another pair of unmodified and m1A-modified oligos that were synthesized using a method that minimized m1A-to-m6A conversion (Zhou et al. 2019). We found very little ligated product using only the m1A-modified oligo (Supplemental Fig. S2A), indicating that m1A can indeed block templated splint ligation. Furthermore, the ligated product was proportional to the ratio of unmodified oligo in total RNA mixtures. We again performed TL-qPCR with 5′ linker oligos with a different 5′ end using m1A-modified or unmodified oligos (Fig. 3A). The Cq values with this m1A-modified oligo were >10 higher than those with the corresponding unmodified oligo under this condition (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Fig. S2B). Using this fully m1A-modified oligo, we also examined how many residues away from the m1A site the ligation site can be before m1A no longer has an effect on TL-qPCR. This enables us to choose a site for on-target control of TL-qPCR. We shifted the ligation site up to 5 or 9 nt upstream (T − N) or downstream (T + N), respectively, of the target m1A site (Fig. 3C). At the same time, we also tested how splint ligation reaction temperature affected the specificity and sensitivity of our method. Temperature optimization can be important for quantifying m1A modification in tRNA, a higher temperature could more readily disrupt the tRNA structure, but may decrease SplintR ligase reactivity. When the ligation site was 3–5 nt away either upstream or downstream from the m1A site, the Cq value differences reached a plateau, and this result was maintained at temperatures between 32°C and 47°C (Fig. 3D). Increasing the ligation reaction temperature above 42°C decreased the TL-qPCR product amounts (Fig. 3D), but also slightly increased the difference between A and m1A RNA oligos (Fig. 3E). Based on these results, we generally used 37°C for template splint ligation and the on-target control site ≥4 nt away from the m1A site for the biological RNA studies below.

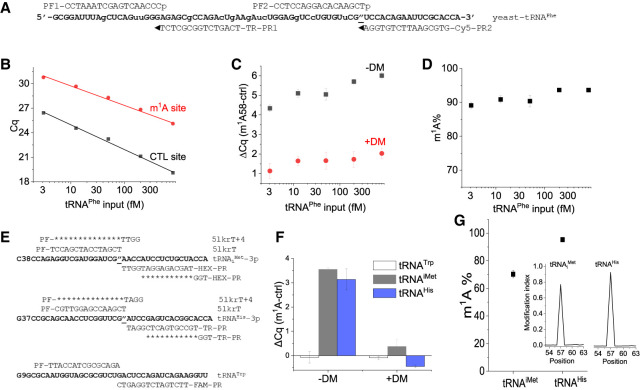

m1A modification in biological tRNAs and rRNA by TL-qPCR

Next, we applied our method to detect and quantify m1A58 modification in yeast tRNAPhe. We designed one pair of linker oligos at the m1A site and another pair at an on-target site away from the m1A site, which served as a m1A independent control for that tRNA; these oligos have different fluorescent probe binding sites for multiplex qPCR (Fig. 4A). We performed TL-qPCR on serial diluted yeast tRNAPhe samples. The Cq values of both the control and m1A ligation sites increased as the input RNA amount decreased (Fig. 4B). To validate that the m1A58 targeting oligos were indeed responsive to m1A, we partially removed the m1A modification using the Escherichia coli AlkB demethylase (Zheng et al. 2015) and used the demethylase-treated sample as a template for TL-qPCR. Changes in differential Cq values (ΔCq) of the control versus m1A site were much smaller in the demethylase-treated sample, confirming that our m1A58 targeting oligos indeed reports this modification in yeast tRNAPhe (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, the difference of ΔCq (the control vs. m1A site) between the untreated and the demethylase treated (i.e., less m1A) (ΔΔCq) remained approximately the same when varying the input RNA from 800 to 3.1 fM, indicating the robustness of our method for a natural tRNA (Fig. 4C). Assuming the removal of m1A by demethylase is complete, we can use the above defined ΔΔCq values and Equation 1 to calculate the m1A modification fraction as follows:

| (1) |

FIGURE 4.

Measuring m1A58 modification in biological RNA. (A) The sequence of yeast tRNAPhe and oligos used in TL-qPCR for m1A58 modification (″: bold and underlined). The two pairs of linkers for yeast tRNAPhe-58m1A and for -5p (control) contain sequences for Cy5 and TR (Texas Red) probe binding sites for qPCR. (B) Cq values of m1A (red) or control (black) ligation oligos of serial diluted inputs of yeast tRNAPhe from 3.1 to 800 fM without AlkB treatment. (C) Differential Cq values between m1A and control ligation oligos of serial diluted yeast tRNAPhe samples without (black) and with (red) AlkB demethylase (DM) treatment. (D) Fraction of m1A58 in yeast tRNAPhe as measured by TL-qPCR using varying amounts of input RNA. (E) Oligonucleotides and linkers used in SplintR ligation for the m1A58 site of human tRNAiMet and tRNAHis, tRNATrp is used as an internal control. Three-color qPCR is run using either HEX(m1A-iMet) + TR(m1A-His) + FAM(Trp) or HEX(CTRL-iMet) + TR(CTRL-His) + FAM(Trp) combination. (F) ΔCq values of 5lkrT (m1A) and 5lkrT + 4 (CTRL) on tRNAiMet (HEX probe), tRNAHis (TR probe), and tRNATrp (FAM probe) without (DM−) and with AlkB treatment (DM+). (G) m1A58 fraction measured by TL-qPCR for tRNAiMet and for tRNAHis. Average of n = 3 biological replicates. Inset: modification index (MI) around the m1A58 (±5 nt) site measured by DM-tRNA-seq for tRNAiMet and tRNAHis (sequencing data from NCBI GEO GSE66550).

We obtained the yeast tRNAPhe m1A58 modification fraction at a 90%–93% level (Fig. 4D), which is close to the ∼97% measured by primer extension using AMV RT stop and gel electrophoresis (Saikia et al. 2010).

We next tested our method for the m1A58 modifications in human tRNAs using HEK293T total RNA as input. Unlike the purified yeast tRNAPhe sample, this experiment tested our ability to directly measure m1A in a complex biological mixture. We chose three target tRNAs for our linker oligo design with different fluorescent probe binding regions for the m1A sites and an on-target control site (Fig. 4E), which enabled three-color qPCR to measure them simultaneously. For m1A sites, we chose to study human tRNAiMet and tRNAHis, which were of biological interest in previous studies (Honda et al. 2015a; Wang et al. 2018); also, tRNAiMet m1A is a biomarker for COVID symptom severity (Katanski et al. 2022). We also designed the ligation oligos for tRNATrp at a region with no known m1A modification, thus using tRNATrp in the same sample as an internal sample quality and quantity control. We performed TL-qPCR using 26 ng total RNA with and without demethylase treatment as template. For the control tRNATrp site, demethylase treatment did not change the ΔCq value, as expected. However, the Cq values of the tRNAiMet and tRNAHis m1A sites were significantly reduced after demethylase treatment, demonstrating the presence of m1A at these locations (Fig. 4F). Thus, with the help of the internal control (tRNATrp), we can use the simplified equation (Equation 2) below to calculate the fraction of m1A modification.

| (2) |

With this method, we determined the m1A58 fraction for tRNAiMet and tRNAHis in the samples without demethylase treatment to be 70 ± 3% and 95 ± 1%, respectively (Fig. 4G). We have shown previously that the DM-tRNA-seq method could quantitatively report m1A58 fractions in HEK293T cells, which was 76% and 95% for tRNAiMet and tRNAHis, respectively (Fig. 4G, inset; Clark et al. 2016). The excellent correlation between TL-qPCR and high-throughput tRNA sequencing demonstrates the effectiveness and accuracy of our TL-qPCR method in detecting and quantifying the m1A fraction in tRNA.

We also observed near zero ΔCq values for the m1A site and the control site for all three tRNAs studied here when m1A was removed by the demethylase treatment (Fig. 4B,C,F), suggesting a similar hybridization efficiency for these oligos to tRNA despite their hybridization to distinct locations in the tRNA structure.

To further test the robustness of TL-qPCR, we applied it to the quantification of m1A9 modification in human mitochondrial tRNAVal and m1A1322 in human 28S rRNA, using 24 ng of HEK293T total RNA with or without demethylase treatment as input. Mitochondrial tRNAVal also has an m2G10 modification next to m1A9 (Cappannini et al. 2024), and 28S rRNA has an Am modification 4 nt downstream from m1A1322 (Taoka et al. 2018). We designed a pair of linker oligos targeting the m1A site, along with another set targeting an on-target site for respective RNA away from the m1A site, acting as an independent control for each m1A site (Supplemental Fig. S3A). We determined the m1A fractions for human mitochondrial tRNAVal m1A9 to be 77 ± 2% and for human 28S rRNA m1A1322 to be 92 ± 1% (Supplemental Fig. S3B). Previous sequencing results showed 94% m1A9 for mt-tRNAVal and over 98% m1A1322 for 28S rRNA (Zheng et al. 2015; Clark et al. 2016; Taoka et al. 2018). The consecutive m1A9m2G10 in mt-tRNAVal may result in a 1.2× under-estimated m1A level by TL-qPCR or an over-estimated m1A9 level by sequencing.

Concluding remarks

In summary, we developed a templated splint ligation-based qPCR method for the detection and quantification of m1A modifications in tRNA and rRNA. With on-target control and internal control, we can obtain the fraction of m1A modifications at a given site. In addition, by including an optional demethylase treatment step, we can also probe the effect of tRNA structure and differential hybridization efficiencies on the quantification of m1A modification in highly structured RNA regions. Our method relies on the specificity and sensitivity of the SplintR ligase. A single base mismatch or inefficient binding of the ligation oligos caused by Watson–Crick face modifications is sufficient to vastly reduce or block the template splint ligation by SplintR ligase. Thus, in principle, our method can be adapted to the studies of other Watson–Crick face modifications in RNA such as N1-methylguanosine (m1G), N3-methylcytosine (m3C), or N2,2-dimethylguanosine (m22G) that are also abundant in eukaryotic tRNAs. Other RNA modifications such as pseudouridine (Ψ) may also be studied using TL-qPCR after chemical treatments that generate Ψ adducts interfering with Watson–Crick base-pairing. Our method can quantitatively access m1A modification in as low as 3 fmol tRNA or ∼75 pg total RNA. In addition to RNA modification detection, our method can be used to detect the abundance of tRNAs or other small RNA biomarkers using a 10–100 pg range of input total RNA. Our method can be performed in a matter of hours (∼3–4 h), is easy to operate, and requires less hands-on time compared to sequencing or primer extension followed by gel electrophoresis. The ease of using the half-day protocol for target RNA modification or abundance detection should enable widespread application of the TL-qPCR method for tRNA and tRNA modification studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotide design

The RNA (A/m1A) and DNA oligonucleotides used in the study were purchased from IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies) using standard desalting purification. RNA oligo synthesis that retains m1A modification for m1A or A containing oligos (A2/m1A2) was described in Zhou et al. (2019). Briefly, RNA oligonucleotides were synthesized in-house using an Expedite DNA synthesizer, followed by normal deprotection for regular oligonucleotides and vendor-suggested deprotection for RNA oligonucleotides containing m1A modifications to avoid Dimroth rearrangement. After deprotection, the RNA oligonucleotides were purified through HPLC with a C18 column and were eluted with 0%–20% acetonitrile in 0.1 M triethylammonium acetate. The desired peak was collected and dried by lyophilization.

Two sets of SplintR ligation linkers (5′ linkers and 3′ linkers) were designed for each m1A site with one set of linker oligos targeting the m1A site and the other set targeting an upstream or downstream control region. The 5′ linker oligos were phosphorylated at the 5′ end to enable ligation. A primer-binding sequence for forward or reverse primers during PCR, and a synthetic Taqman probe binding sequence were designed just downstream from the reverse primer-binding site in the 3′ linker oligo.

Synthetic primers and probes were used in qPCR for m1A quantification, which were all designed as artificial sequences without complementary matching to any human genomic DNA or RNA sequences. A set of primers and a fluorescence-labeled probe were designed for each m1A site to enable multiplex qPCR (Cy5, Texas Red, and FAM).

All DNA and RNA oligo and probe sequences are provided in Supplemental Tables S1–S5.

HEK293 cell total RNA and demethylase treatment

HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Cytiva, SH30022.01) with 10% FBS and 1% Pen–Strep (Penicillin–Streptomycin) to 80% confluency (Zhang et al. 2019). Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer's manual. Demethylase treatment was performed as reported previously (Zheng et al. 2015).

TL-qPCR procedure

TL-qPCR consists of two major steps, template ligation and qPCR. To quantify m1A modification, a pair of template ligation reactions targeting the m1A site and control site were performed. Briefly, ligation linker oligos for the m1A site or control site were mixed at a final concentration of 100 nM as 10× stock solution separately. The amount of the ligation oligos was in large molar excess to the template RNA, so that every template RNA should have both oligos hybridized to it at most of all times. For each template ligation reaction, 1 µL total RNA (typically 10–50 ng) and 1 µL 10× ligation linker oligos solution were added to the PCR tube followed by the addition of 6.8 µL H2O. The ligation mixture was briefly vortexed and spun down. The ligation mixture was then incubated in a thermocycler at 90°C for 2 min followed by gradual decreasing to 40°C. One microliter 10×SplintR ligase buffer and 0.2 µL SplintR ligase (NEB, M0375L) were then added to each ligation mixture and mixed (10 µL final ligation mixture). The ligation mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min followed by incubation at 68°C for 5 min to deactivate the SplintR ligase. qPCR reactions were performed in 20 µL on a Cielo 6 qPCR machine (Azure Biosystems) with specific primers and probes (Supplemental Tables S1–S5). Briefly, PCR primers and fluorescent probes were premixed as a 10× solution containing 2 µM PCR primers and 1 µM fluorescent probes. For each qPCR reaction, 10 µL 2× PrimeTime Gene Expression Master Mix (IDT, 1055772), 2 µL 10× primer/probe mix, 7 µL H2O, and 1 µL ligation mixture were added to the PCR tube and mixed. qPCR reactions were performed on a 96-well qPCR machine (Azure Biosystems, Cielo 6) using the conditions below: initial denaturation, 95°C, 2 min; subsequent denaturation, 95°C, 20 sec; annealing and extension, 56°C, 20 sec, 40 cycles.

Cq values were obtained using the qPCR machine software (Azure Biosystems). Cq values were then analyzed using the ΔCq and ΔΔCq method after normalizing to endogenous control, and m1A modification fractions were then calculated using either Equation 1 or Equation 2. When data from both with or without demethylase treatment were obtained, we used Equation 1 to calculate the m1A modification fraction as follows: (i) Calculate the ΔCq values between the m1A site and control site for both untreated (−DM) and demethylase treated (+DM) samples using value for +DM sample served as control to exclude the differential hybridization efficiencies between the m1A site and control site, assuming the removal of m1A by demethylase was complete. (ii) Calculate the ΔΔCq values between −DM and +DM samples using ΔΔCq = ΔCq−DM − ΔCq+DM. (iii) Calculate the fraction of A using A% = 100% × 2−ΔΔCq. (iv) Finally, the m1A fraction can be obtained using m1A% = 100% − A%.

Without the demethylase-treated sample, the simplified Equation 2 and ΔCq value can be used to calculate the m1A modification fraction as follows: (i) Calculate the ΔCq value between the m1A site and control site using . (ii) Calculate the fraction of A first using A% = 100% × 2−ΔCq. (iii) The m1A fraction can be obtained using m1A% = 100% − A%.

The entire TL-qPCR procedure without demethylase treatment takes about 3–4 h depending on the number of samples processed.

TL-qPCR optimization and validation

To check the sensitivity of TL-qPCR, we tested serial diluted synthetic oligos samples. Briefly, 2 µL 10× serial diluted synthetic oligos samples with concentrations ranging from 1 nM to 0.1 pM were mixed with 2 µL 10× ligation linker oligos solution. TL-qPCR was then performed as described above. To test the effect of temperature and RNA modifications on SplintR ligation efficiency, template ligation reactions were performed at different temperatures (32°C, 37°C, 42°C, or 47°C) using ligation linker oligos targeting the m1A modification site or sites away from the m1A site. TL-qPCR was then performed as described above.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from NIAID (R21 AI169280 to T.P.).

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.079895.123.

Freely available online through the RNA Open Access option.

MEET THE FIRST AUTHOR

Wen Zhang.

Meet the First Author(s) is an editorial feature within RNA, in which the first author(s) of research-based papers in each issue have the opportunity to introduce themselves and their work to readers of RNA and the RNA research community. Wen Zhang is the co-first author of this paper, “Quantification of tRNA m1A modification by templated-ligation qPCR,” along with Hankui Chen. Wen is a postdoc student in Dr. Tao Pan's laboratory at the University of Chicago. His research focus is RNA modification and microbiome metabolites.

What are the major results described in your paper and how do they impact this branch of the field?

We developed a template ligation and qPCR-based quantification method for tRNA m1A modification and tRNA abundance. Our method requires a small amount of input RNA and can be done in a matter of hours. It will be useful for the quantification of tRNA abundance and m1A modification when input samples and time are limited, such as when testing clinical samples.

What led you to study RNA or this aspect of RNA science?

Previous studies of our lab showed that m1A modification levels in specific tRNAs can be used as biomarkers for clinical prognosis such as the development of COVID-19 severity. Since clinical samples are often limited by the amount, and the tested results should be available as soon as possible, we wanted to develop a sensitive and fast method for the quantification of m1A modification.

During the course of these experiments, were there any surprising results or particular difficulties that altered your thinking and subsequent focus?

The Dimroth rearrangement of m1A modification in control samples caused some problems at the beginning. However, when we applied a new synthesis method to avoid Dimroth rearrangement, we saw nearly no ligated product when we used 100% m1A-modified oligo as input. This means that the problem of base-pairing at even one nucleotide caused by m1A modification is efficient in blocking SplintR template ligation.

What are some of the landmark moments that provoked your interest in science or your development as a scientist?

It was during high school orientation, when the principal of a local university gave a talk about “quantum chemistry.” Although it was hard to understand the talk as a first-year high school student, the talk did make me think more about the materials that make up the world.

What are your subsequent near- or long-term career plans?

My short-term goal is to finish the project I have been working on for a few years and probably find a second postdoc position if it is necessary. My long-term career plan is to find an academic job.

How did you decide to work together as co-first authors?

Hankui was the research scientist in the lab and was very good at qPCR. I was the postdoc in the lab and had studied tRNA modifications for a long time. We both agreed that combining our strengths would make this project move forward smoothly.

REFERENCES

- Anderson J, Phan L, Cuesta R, Carlson BA, Pak M, Asano K, Björk GR, Tamame M, Hinnebusch AG. 1998. The essential Gcd10p-Gcd14p nuclear complex is required for 1-methyladenosine modification and maturation of initiator methionyl-tRNA. Genes Dev 12: 3650–3662. 10.1101/gad.12.23.3650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auxilien S, Keith G, Le Grice SF, Darlix JL. 1999. Role of post-transcriptional modifications of primer tRNALys,3 in the fidelity and efficacy of plus strand DNA transfer during HIV-1 reverse transcription. J Biol Chem 274: 4412–4420. 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappannini A, Ray A, Purta E, Mukherjee S, Boccaletto P, Moafinejad SN, Lechner A, Barchet C, Klaholz BP, Stefaniak F, et al. 2024. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modifications and related information. 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res 52: D239–D244. 10.1093/nar/gkad1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Qi M, Shen B, Luo G, Wu Y, Li J, Lu Z, Zheng Z, Dai Q, Wang H. 2019. Transfer RNA demethylase ALKBH3 promotes cancer progression via induction of tRNA-derived small RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 47: 2533–2545. 10.1093/nar/gky1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark WC, Evans ME, Dominissini D, Zheng G, Pan T. 2016. tRNA base methylation identification and quantification via high-throughput sequencing. RNA 22: 1771–1784. 10.1261/rna.056531.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozen AE, Quartley E, Holmes AD, Hrabeta-Robinson E, Phizicky EM, Lowe TM. 2015. ARM-seq: AlkB-facilitated RNA methylation sequencing reveals a complex landscape of modified tRNA fragments. Nat Methods 12: 879–884. 10.1038/nmeth.3508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominissini D, Nachtergaele S, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Peer E, Kol N, Ben-Haim MS, Dai Q, Di Segni A, Salmon-Divon M, Clark WC, et al. 2016. The dynamic N1-methyladenosine methylome in eukaryotic messenger RNA. Nature 530: 441–446. 10.1038/nature16998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel JD. 1975. Mechanism of the Dimroth rearrangement in adenosine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 64: 581–586. 10.1016/0006-291X(75)90361-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauenschild R, Tserovski L, Schmid K, Thüring K, Winz ML, Sharma S, Entian KD, Wacheul L, Lafontaine DL, Anderson J, et al. 2015. The reverse transcription signature of N-1-methyladenosine in RNA-Seq is sequence dependent. Nucleic Acids Res 43: 9950–9964. 10.1093/nar/gkv895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm M, Brule H, Degoul F, Cepanec C, Leroux JP, Giege R, Florentz C. 1998. The presence of modified nucleotides is required for cloverleaf folding of a human mitochondrial tRNA. Nucleic Acids Res 26: 1636–1643. 10.1093/nar/26.7.1636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm M, Giegé R, Florentz C. 1999. A Watson-Crick base-pair-disrupting methyl group (m1A9) is sufficient for cloverleaf folding of human mitochondrial tRNALys. Biochemistry 38: 13338–13346. 10.1021/bi991061g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda S, Loher P, Shigematsu M, Palazzo JP, Suzuki R, Imoto I, Rigoutsos I, Kirino Y. 2015a. Sex hormone-dependent tRNA halves enhance cell proliferation in breast and prostate cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112: E3816–E3825. 10.1073/pnas.1510077112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda S, Shigematsu M, Morichika K, Telonis AG, Kirino Y. 2015b. Four-leaf clover qRT-PCR: a convenient method for selective quantification of mature tRNA. RNA Biol 12: 501–508. 10.1080/15476286.2015.1031951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J, Vaud S, Zhelkovsky AM, Posfai J, McReynolds LA. 2016. Sensitive and specific miRNA detection method using SplintR Ligase. Nucleic Acids Res 44: e116. 10.1093/nar/gkw399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katanski CD, Alshammary H, Watkins CP, Huang S, Gonzales-Reiche A, Sordillo EM, van Bakel H, Mount Sinai P, Lolans K, Simon V, et al. 2022. tRNA abundance, modification and fragmentation in nasopharyngeal swabs as biomarkers for COVID-19 severity. Front Cell Dev Biol 10: 999351. 10.3389/fcell.2022.999351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalique A, Mattijssen S, Maraia RJ. 2022. A versatile tRNA modification-sensitive northern blot method with enhanced performance. RNA 28: 418–432. 10.1261/rna.078929.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzywkowski T, Nilsson M. 2017. Fidelity of RNA templated end-joining by chlorella virus DNA ligase and a novel iLock assay with improved direct RNA detection accuracy. Nucleic Acids Res 45: e161. 10.1093/nar/gkx708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Xiong X, Wang K, Wang L, Shu X, Ma S, Yi C. 2016. Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals reversible and dynamic N1-methyladenosine methylome. Nat Chem Biol 12: 311–316. 10.1038/nchembio.2040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Clark W, Luo G, Wang X, Fu Y, Wei J, Wang X, Hao Z, Dai Q, Zheng G, et al. 2016. ALKBH1-mediated tRNA demethylation regulates translation. Cell 167: 816–828.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Zeng T, He C, Rawal VH, Zhou H, Dickinson BC. 2022. Development of mild chemical catalysis conditions for m1A-to-m6A rearrangement on RNA. ACS Chem Biol 17: 1334–1342. 10.1021/acschembio.2c00178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez A, Yamashita S, Nagaike T, Sakaguchi Y, Suzuki T, Tomita K. 2017. Human BCDIN3D monomethylates cytoplasmic histidine transfer RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 45: 5423–5436. 10.1093/nar/gkx051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oerum S, Dégut C, Barraud P, Tisne C. 2017. m1A post-transcriptional modification in tRNAs. Biomolecules 7: 20. 10.3390/biom7010020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saikia M, Fu Y, Pavon-Eternod M, He C, Pan T. 2010. Genome-wide analysis of N1-methyl-adenosine modification in human tRNAs. RNA 16: 1317–1327. 10.1261/rna.2057810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai M, Ohtsuki T, Watanabe Y, Watanabe K. 2001. Requirement of modified residue m1A9 for EF-Tu binding to nematode mitochondrial tRNA lacking the T arm. Nucleic Acids Res Suppl 1: 237–238. 10.1093/nass/1.1.237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai M, Ohtsuki T, Watanabe K. 2005. Modification at position 9 with 1-methyladenosine is crucial for structure and function of nematode mitochondrial tRNAs lacking the entire T-arm. Nucleic Acids Res 33: 1653–1661. 10.1093/nar/gki309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Suzuki T. 2014. A complete landscape of post-transcriptional modifications in mammalian mitochondrial tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 42: 7346–7357. 10.1093/nar/gku390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Yashiro Y, Kikuchi I, Ishigami Y, Saito H, Matsuzawa I, Okada S, Mito M, Iwasaki S, Ma D, et al. 2020. Complete chemical structures of human mitochondrial tRNAs. Nat Commun 11: 4269. 10.1038/s41467-020-18068-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taoka M, Nobe Y, Yamaki Y, Sato K, Ishikawa H, Izumikawa K, Yamauchi Y, Hirota K, Nakayama H, Takahashi N, et al. 2018. Landscape of the complete RNA chemical modifications in the human 80S ribosome. Nucleic Acids Res 46: 9289–9298. 10.1093/nar/gky811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Matuszek Z, Huang Y, Parisien M, Dai Q, Clark W, Schwartz MH, Pan T. 2018. Queuosine modification protects cognate tRNAs against ribonuclease cleavage. RNA 24: 1305–1313. 10.1261/rna.067033.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J, Liu F, Lu Z, Fei Q, Ai Y, He PC, Shi H, Cui X, Su R, Klungland A, et al. 2018. Differential m6A, m6Am, and m1A demethylation mediated by FTO in the cell nucleus and cytoplasm. Mol Cell 71: 973–985.e5. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Wang Y, Tang Q, Wei L, Zhang X, Jia G. 2018. An elongation- and ligation-based qPCR amplification method for the radiolabeling-free detection of locus-specific N6-methyladenosine modification. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 57: 15995–16000. 10.1002/anie.201807942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong WD, Zhao YC, Wei ZL, Li CF, Zhao RZ, Ge JB, Shi B. 2023. N1-methyladenosine formation, gene regulation, biological functions, and clinical relevance. Mol Ther 31: 308–330. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.10.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeakley JM, Shepard PJ, Goyena DE, VanSteenhouse HC, McComb JD, Seligmann BE. 2017. A trichostatin A expression signature identified by TempO-Seq targeted whole transcriptome profiling. PLoS ONE 12: e0178302. 10.1371/journal.pone.0178302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Jia G. 2018. Reversible RNA modification N1-methyladenosine (m1A) in mRNA and tRNA. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 16: 155–161. 10.1016/j.gpb.2018.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Eckwahl MJ, Zhou KI, Pan T. 2019. Sensitive and quantitative probing of pseudouridine modification in mRNA and long noncoding RNA. RNA 25: 1218–1225. 10.1261/rna.072124.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Xu R, Matuszek Z, Cai Z, Pan T. 2020. Detection and quantification of glycosylated queuosine modified tRNAs by acid denaturing and APB gels. RNA 26: 1291–1298. 10.1261/rna.075556.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Lu L, Li X. 2022. Detection technologies for RNA modifications. Exp Mol Med 54: 1601–1616. 10.1038/s12276-022-00821-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G, Qin Y, Clark WC, Dai Q, Yi C, He C, Lambowitz AM, Pan T. 2015. Efficient and quantitative high-throughput tRNA sequencing. Nat Methods 12: 835–837. 10.1038/nmeth.3478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Rauch S, Dai Q, Cui X, Zhang Z, Nachtergaele S, Sepich C, He C, Dickinson BC. 2019. Evolution of a reverse transcriptase to map N1-methyladenosine in human messenger RNA. Nat Methods 16: 1281–1288. 10.1038/s41592-019-0550-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubradt M, Gupta P, Persad S, Lambowitz AM, Weissman JS, Rouskin S. 2017. DMS-MaPseq for genome-wide or targeted RNA structure probing in vivo. Nat Methods 14: 75–82. 10.1038/nmeth.4057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]