Abstract

As the average life expectancy increases, neurosurgeons are likely to encounter patients aged 80 years and above with carotid stenosis; however, whether old age affects clinical post-treatment outcomes of carotid endarterectomy (CEA) or carotid artery stenting (CAS) remains inconclusive. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the outcomes following CEA or CAS in patients aged 80 years and above. This study included older over 80 years (n = 34) and younger patients (<80 years; n = 222) who underwent CEA or CAS between 2012 and 2022. All of them were followed up for a mean of 55 months. All-cause mortality, the incidence of vascular events, ability to perform daily activities, and nursing home admission rates were assessed. During follow-up periods, 34 patients (13.3%) died due to coronary artery disease, malignancy, and pneumonia, and the incidence was significantly higher in the elderly group than in the younger group (P = 0.03; HR, 3.01; 95% CI, 1.53-5.56). The incidence of vascular events did not differ between the older group (29.5%) and the younger group (26.9%, P = 0.58); however, the incidence was significantly higher in patients with high-intensity plaques than in those without that (P = 0.008; HR, 2.83, 95%CI, 1.27-4.87). The decline in the ability to perform daily activities and increased nursing home admission rates were high in elderly patients (P < 0.01). Although the mortality rate was higher in the elderly group, subsequent vascular events were comparable to that in the younger group. The results suggest that CEA and CAS are safe and useful treatments for carotid stenosis in older patients, especially to prevent ipsilateral ischemic stroke.

Keywords: carotid stenosis, carotid artery stenting, carotid endarterectomy, older patients, long-term follow-up

Introduction

Carotid stenosis is a major public health problem worldwide1-3) and one of the leading causes of disability in Japan.4,5) As the average life expectancy increases globally, especially in Japan, the likelihood that neurosurgeons will encounter older patients (aged ≥80 years) with carotid stenosis will increase accordingly. The extensive use of ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography (MRI/MRA) as imaging techniques has improved the early detection rate of carotid stenosis, and the effectiveness and safety of carotid endarterectomy (CEA) and carotid artery stenting (CAS) to treat carotid stenosis have been widely reported.6-8) According to the current European Society of Cardiology guidelines, CEA and CAS for carotid revascularization are the treatments of choice for preventing stroke in asymptomatic patients with a degree of internal carotid artery stenosis of 60%-99% and in symptomatic patients with a degree of stenosis of 50%-99%.9) There is also increasing evidence that CEA/CAS can prevent ischemic stroke while improving the quality of life in certain patient populations;10,11) however, whether CEA/CAS can provide such benefits in elderly individuals remains inconclusive.12) A previous study conducted by Reichmann et al. suggested that octogenarians who underwent carotid revascularization surgery exhibited a 30-day stroke/death rate of 12.1%, which was much higher than the rate of 3.2% observed in younger patients.13) This suggests that optimal surgical management is mandatory when performing CEA/CAS in older patients. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the long-term clinical outcomes following CEA and CAS to treat carotid stenosis in older patients (≥80 years) or younger (<80 years) patients.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our University Hospital and involved data analysis from a prospective cohort of patients with carotid stenosis who underwent treatment at our institution. Following the ethical standards of the institutional research committees, formal consent was not required due to the noninvasive nature of the study. Instead, the study outline was made publicly available on our institutional homepage, and patients or their guardians were provided an opt-out option if they did not wish to be included in the study.

Patients

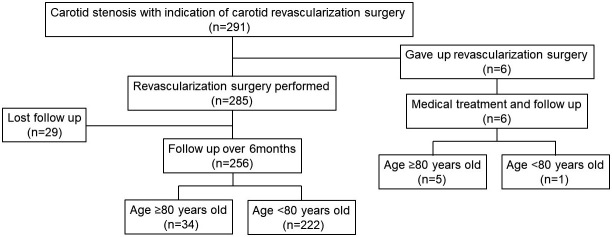

A total of 291 patients exhibited indications for carotid revascularization from April 2012 to March 2022; six of these patients (2.1%) declined to undergo revascularization surgery due to their health condition even though they were admitted to our hospital for CEA/CAS. The reasons for the decline were exacerbation of aspiration pneumonia in four cases and heart failure in two cases. Thus, 285 carotid revascularization surgeries were performed, with 140 patients (49.1%) undergoing CEA and 145 patients (50.9%) undergoing CAS. All CEA/CAS were performed in our institution. This study analyzed the data of the 256 patients (89.8%) whose follow-up period exceeded 6 months. A flowchart of patient selection is presented in Fig. 1. The mean age of the patients was 72.5 ± 6.9 years (range: 55-88 years), comprising 238 males (93.0%) and 18 females (7.0%). In this study, the patients were classified into two groups according to age: a younger patient (<80 years) and an older patient (≥80 years). Data related to demographic variables and perioperative complications were collected, including data on all-cause mortality and the incidence of vascular events, such as stroke, coronary disease, and peripheral arterial disease. We also collected data on the ability to perform daily activities, which included walking and getting dressed or bathing independently, as well as the rate of nursing home admissions during the follow-up period.

Fig. 1.

This chart suggested this study's patient selection flow. Finally, 256 patients who underwent CEA/CAS with over 6 months of follow-up were included in this study.

Evaluation of plaque composition by MRI/MRA

Plaque composition in each patient was evaluated using a 1.5-T MRI scanner (Magnetom Vision; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). To characterize the plaque, long-axis and axial images of the carotid artery were obtained from the T1 Sampling Perfection with Application-optimized Contrast using different flip angle Evolution sequences and time-of-flight (TOF) MRA by targeting the area with the highest degree of stenosis. 3D TOF MRA was also performed through both carotid bifurcations in the axial plane. A signal intensity >150% of that of the muscle adjacent to the plaque indicated a hyperintense signal; hyperintense signals on T1-weighted and TOF images indicated intraplaque hemorrhage (IPH). The MRI parameters used in this study have been previously described.14)

Treatment strategy

Our treatment strategy primarily employed using CEA and CAS for symptomatic and asymptomatic lesions, respectively. However, a crossover of therapeutic options was considered for patients exhibiting an elevated risk of surgical complications associated with CEA or CAS. In this study, 25 patients had a crossover of therapeutic options. In detail, CAS was performed for 15 patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis due to chronic heart failure and lung disease. In contrast, 13 patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis were treated using CEA due to vulnerable plaque. Age was factored out in the selection of the surgical interventions. CEA/CAS was performed for patients with independence in activities of daily living.

CEA procedure

CEA was performed by experienced and certified neurosurgeons, as previously described.15) All surgical procedures were performed under general anesthesia using routine intraoperative near-infrared spectroscopy to continuously measure the cerebral oxygenation status of patients to detect critical cerebral ischemia.16) Antiplatelet therapy continued during the perioperative period. The carotid artery was sutured using a primary closure technique. Routine internal shunting was performed in all patients regardless of the near-infrared spectroscopy findings. The plaque was carefully removed under a surgical microscope.

CAS procedure

CAS was performed under local anesthesia by a team of experienced neurosurgeons, as previously described.17) During the 14-day period before the procedure, the patients were administered an oral antiplatelet regimen comprising 75 mg of clopidogrel and 100 mg of acetylsalicylic acid daily. Vascular access was achieved under local anesthesia using either a femoral or radial artery approach. The procedure was performed with complete systemic heparinization to maintain an activated clotting time approximately twice that of the baseline value. For approaches involving the femoral artery, 8-French introducers and catheters were inserted, and filter-based embolic capture guidewires were used to prevent embolisms. Predilatation was followed by stent deployment, if required. We used a precise stent (Cordis Neurovascular, Miami Lakes, FL) for patients with a stable plaque and a carotid WALLSTENT (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) or CASPER Rx stent (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) for those with unstable plaque. In cases in which stent expansion was insufficient, post-dilatation was performed.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using EZR software, version 1.61 (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan). Data were compared between subgroups using the Mann-Whitney U test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated to estimate the probability of survival at specific time points and to assess clinical outcomes related to death and vascular events. The log-rank test was used to compare the significance of intergroup differences. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Cox proportional hazard modeling was performed to evaluate the associations between potential risk factors and the odds of death or vascular events by estimating the hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We performed unadjusted analyses (model 1), age- and sex-adjusted analyses (model 2), and surgical methods (CEA/CAS) (model 3).

Results

Thirty-four patients comprised the older patients (≥80 years), including 20 (58.8%) and 14 patients (41.2%) who underwent CEA and CAS, respectively. The remaining 222 patients comprised the younger patients (<80 years), including 110 (49.5%) and 122 (50.5%) patients who underwent CEA and CAS, respectively. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the participants. The prevalence rates of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and coronary artery disease did not differ between the two age groups (P = 0.15, 0.72, 0.83, and 0.85, respectively). There were 20 symptomatic (58.8%) and 14 asymptomatic (41.2%) patients in the elderly patients and 108 symptomatic (48.6%) and 114 asymptomatic (51.4%) patients in the younger patients; the number of symptomatic patients did not significantly differ between the two age groups (P = 0.27). Regarding plaque characterization, the Magnetic resonance techniques revealed 10 patients (29.4%) with fibrous plaques, 5 patients (14.7%) with lipid-rich plaques, and 19 patients (55.9%) with IPH in the elderly patients; the younger group had 98 patients (44.1%) with fibrous plaques, 30 (13.5%) with lipid-rich plaques, and 94 (42.4%) with IPH. The degree of stenosis was 72.5% ± 19.5% and 69.4% ± 22.0% in the elderly and younger patients, respectively, with no statistically significant differences between the two groups concerning plaque composition or the degree of stenosis (P = 0.33 and P = 0.24, respectively). Three and two patients exhibited 30-day morbidity following CEA and CAS, respectively. Specifically, one patient developed cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome following CEA and exhibited signs of memory disturbance and concentration deficits. Two patients developed dysphagia following CEA. One patient experienced hypoxic encephalopathy secondary to anaphylactic shock, and one experienced acute myocardial infarction. Therefore, the 30-day morbidity rates were 2.3% and 1.5% for those who underwent CEA and CAS, respectively. One patient with dysphagia was from the elderly patients. There was no statistical difference in the prevalence of morbidity events between the elderly and younger patients.

Table 1.

Demographic and radiological feature of old and moderate age groups

| Older patients n = 34 |

Younger patients n = 222 |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 82.6 ± 2.5 | 65.8 ± 8.1 | <0.01 |

| Gender | |||

| male | 30 | 208 | 0.27 |

| female | 4 | 14 | |

| Past history | |||

| Hypertension | 29 | 201 | 0.15 |

| Diabetic mellitus | 19 | 116 | 0.72 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 25 | 169 | 0.83 |

| Coronary artery disease | 11 | 77 | 0.85 |

| Symptom | |||

| symptomatic | 20 | 108 | 0.27 |

| asymptomatic | 14 | 114 | |

| Plaque composition | |||

| fibrous | 10 | 98 | 0.33 |

| lipid rich | 5 | 30 | |

| IPH | 19 | 94 | |

| Degree of stenosis (%) | 72.5 ± 19.5 | 69.4 ± 22.0 | 0.24 |

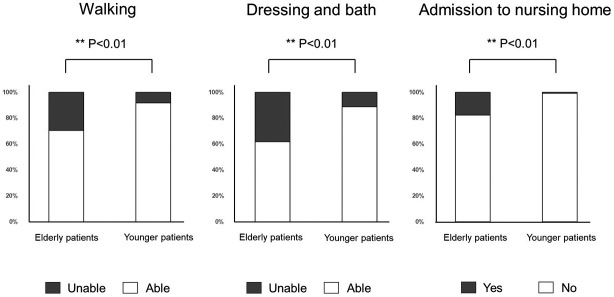

The mean follow-up period was 54.5 ± 29.2 months (range: 7-124 months), during which 34 patients (13.3%) died. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves show the probability of death with respect to time according to age group (Fig. 2A). Death occurred more frequently in the elderly patients than in the younger patients (log-rank test, P = 0.03; Cox proportional hazards model for the elderly patient: model 1, HR, 3.01, 95% CI, 1.53-5.56, P = 0.03; model 2, HR, 2.98, 95% CI, 1.33-5.21, P = 0.03; and model 3, HR 2.88, 95% CI 2.88-5.10, P = 0.03). The most frequent cause of death was acute coronary syndrome (26.5% of cases), followed by malignant neoplasm (23.5%), pneumonia (14.7%), and renal failure (8.8%) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

A: Kaplan-Meier survival plot for both age patients following CEA/CAS. The outcomes significantly differed between the younger and older patients (log-rank test, P = 0.03).

B: Pie chart depicting the causes of death during the follow-up period. The most frequent cause of death was acute coronary syndrome (26.5%), followed by malignant neoplasm (23.5%), pneumonia (14.7%), and renal failure (8.8%).

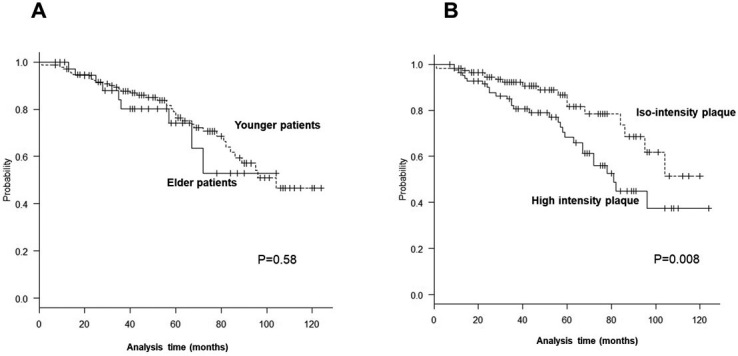

Vascular events did not differ between elderly patients (29.5%) and younger patients (26.9%) (Fig. 3A), and there were no significant intergroup differences with respect to age (log-rank test, P = 0.58). Vascular events occurred more frequently in those with high-intensity plaque than in those with iso-intensity plaque (log-rank test, P = 0.008; Cox proportional hazards model for high-intensity plaque: model 1, HR, 2.83, 95% CI, 1.27-4.87, P = 0.008; model 2, HR, 2.77, 95% CI, 1.23-4.68, P = 0.01; model 3, HR, 2.81, 95% CI, 1.29-4.92, P = 0.006) (Fig. 3B). During the follow-up period, stroke occurred in 11 patients (4.3%), including 8 cases of contralateral ischemic stroke, 1 case of ipsilateral ischemic stroke, and 1 case of contralateral intracerebral hemorrhage. Among those who experienced stroke, two (5.9%) and nine (4.1%) were from the elderly and younger patients, respectively. Treatment for restenosis was required in two patients who underwent CEA and the other two patients who underwent CAS.

Fig. 3.

A: The Kaplan-Meier plot of the probability of vascular events in both patient groups following CEA/CAS. There were no significant differences between the younger and elderly patients (log-rank test, P = 0.58).

B: The Kaplan-Meier plot of the probability of vascular events in those with high-intensity and iso-intensity plaques. There were significant differences between the patients with iso-intensity and high-intensity plaques (log-rank test, P = 0.008).

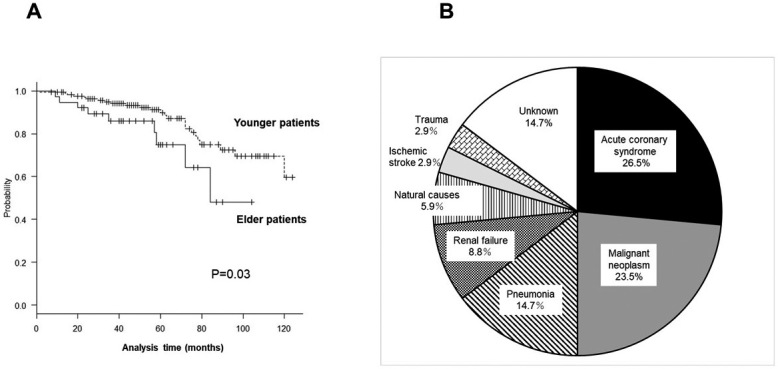

During the follow-up period, 28 patients (10.7%) could not walk, 38 (14.8%) could neither get dressed nor bath independently, and 8 (3.2%) were admitted to a nursing home. Specifically, 10 patients (29.4%) in the elderly group and 18 (8.1%) in the younger group could not walk; 13 patients (38.2%) in the older group and 25 (11.3%) in the younger group could neither get dressed nor bath independently; and 6 of the 8 patients admitted to nursing homes were from the elderly group. Dementia was primarily the cause of the nursing home admissions (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Bar graphs showing the proportions of patients who could not perform activities of daily living and nursing home admissions in both age groups. Twenty-eight patients (10.7%) could not walk, 38 patients (14.8%) could neither get dressed nor bath independently, and 8 patients (3.2%) were admitted to a nursing home. The proportions of patients who could neither walk nor get dressed and bath independently were significantly higher in the older patients than in the younger patients, including the proportion of patients admitted to a nursing home.

Discussion

This study's results suggest that CEA and CAS are relatively safe treatment options in older patients, preventing impending ipsilateral ischemic stroke. Vascular events after these procedures did not differ between the elderly and younger patients; however, the all-cause mortality rate was significantly higher in the elderly patients than in younger patients. Furthermore, a decline in the ability to perform daily activities and increased nursing home admissions were significantly more prevalent in older patients.

Other factors should also be considered to optimize the benefits of CEA/CAS among elderly patients, such as the relatively short life expectancy and period of time without disability postprocedure. A study conducted by Rango et al. suggested that the proportion of older adults with frailty continues to increase in developed countries as a result of continual improvements in healthcare, nutrition, and disease prevention.18) Several studies have provided evidence supporting the safety of CEA/CAS in older populations.7,19,20) Similarly, the present study revealed that perioperative morbidity did not differ between patients in the elderly and younger age groups, suggesting that elderly patients are at low risk of experiencing periprocedural adverse events after undergoing CEA/CAS. However, no study has yet compared the long-term outcomes among elderly patients undergoing CEA/CAS with those of the same age undergoing other modern medical treatments, including differences in life expectancy and the decline in ability to perform activities of daily living. Future prospective studies must be based on detailed and accurate patient selection criteria to identify specific subgroups of older patients with high stroke and low late mortality risks who can benefit from CEA/CAS.

This study found that high-intensity plaque on T1WI leads to a high prevalence of future vascular disease. Previously, we reported that inflammation in unstable carotid plaque is one of the phenotypes in chronic and systemic inflammation.21) Considering these results, plaque composition is important in predicting ischemic complications of CEA/CAS and as a surrogate marker of systemic inflammation related to future vascular events.

Increasing evidence suggests that CEA/CAS can lead to neurocognitive improvements.22-24) In patients with severe carotid stenosis, baseline measures of cognitive function may be below the normal levels observed in the general population;25) however, whether elderly patients experience neurocognitive improvements following CEA/CAS remains controversial. For example, a study by Succar et al. suggested that carotid interventions improved cognitive function in younger patients with carotid occlusive atherosclerosis, whereas no cognitive benefits were observed in males above 80 years old.26) Regardless, judicious intervention to treat carotid stenosis could reduce the growing burden of stroke and dementia in aging populations.27) In this study, 3.2% of all patients were admitted to nursing homes due to the progression of dementia during the follow-up period. Unfortunately, we could not compare our results with those of other populations due to the small sample size. Therefore, further investigations are warranted to excellently understand the postsurgical cognitive changes occurring in older patients.

Although vascular events, such as acute coronary syndrome, did not differ between the older and younger age patients after CEA/CAS, the rate of all-cause mortality was significantly higher in the elderly age patients, including the prevalence of the decline in ability to perform daily activities and increased nursing home admissions. However, the findings of this study suggest that CEA/CAS is comparatively safe to perform in elderly patients, preventing impending ipsilateral ischemic stroke.

Abbreviations

CAS, carotid artery stenting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; ICA, internal carotid artery; IPH, intraplaque hemorrhage; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SPACE, sampling perfection with application-optimized contrast using different flip angle evolutions; TOF, time of flight

Conflicts of Interest Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1). Saba L, Saam T, Jäger HR, et al. : Imaging biomarkers of vulnerable carotid plaques for stroke risk prediction and their potential clinical implications. Lancet Neurol 18: 559-572, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Song P, Fang Z, Wang H, et al. : Global and regional prevalence, burden, and risk factors for carotid atherosclerosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 8: e721-e729, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). van Dam-Nolen DHK, Truijman MTB, van der Kolk AG, et al. : Carotid plaque characteristics predict recurrent ischemic stroke and TIA: the PARISK (plaque at RISK) study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 15: 1715-1726, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Arimura K, Iihara K, Satow T, et al. : Safety and feasibility of neuroendovascular therapy for elderly patients: analysis of Japanese registry of neuroendovascular Therapy 3. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 59: 305-312, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Yamao Y, Ishii A, Satow T, Iihara K, Sakai N, Japanese Registry of Neuroendovascular Therapy investigators : The current status of endovascular treatment for extracranial steno-occlusive diseases in Japan: analysis using the Japanese registry of neuroendovascular Therapy 3 (JR-NET3). Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 60: 1-9, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Fisher ES, Malenka DJ, Solomon NA, Bubolz TA, Whaley FS, Wennberg JE: Risk of carotid endarterectomy in the elderly. Am J Public Health 79: 1617-1620, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Grant A, White C, Ansel G, Bacharach M, Metzger C, Velez C: Safety and efficacy of carotid stenting in the very elderly. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 75: 651-655, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Sadideen H, Thomson DR, Lewis RR, Padayachee TS, Taylor PR: Carotid endarterectomy in the elderly: risk factors, intraoperative carotid hemodynamics and short-term complications: a UK tertiary center retrospective analysis. Vascular 21: 273-277, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Aboyans V, Ricco JB, Bartelink MEL, et al. : ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS): document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteries Endorsed by: the European Stroke Organization (ESO) The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur Heart J 39: 763-816, 2018, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Chabowski M, Grzebien A, Ziomek A, Dorobisz K, Leśniak M, Janczak D: Quality of life after carotid endarterectomy: a review of the literature. Acta Neurol Belg 117: 829-835, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Meguro K, Suzuki R, Nakata E, Ishii H, Yamaguchi S: Cognitive impairment affects mortality in older people in Japan. The Tajiri project 1991-2005. J Am Geriatr Società 62: 1793-1795, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Uno M: History of carotid artery reconstruction around the world and in Japan. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 63: 283-294, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Reichmann BL, van Lammeren GW, Moll FL, de Borst GJ: Is age of 80 years a threshold for carotid revascularization? Curr Cardiol Rev 7: 15-21, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Kashiwazaki D, Yamamoto S, Hori E, Akioka N, Noguchi K, Kuroda S: Thin calcification (< 2 mm) can highly predict intraplaque hemorrhage in carotid plaque: the clinical significance of calcification types. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 164: 1635-1643, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Kashiwazaki D, Shiraishi K, Yamamoto S, et al. : Efficacy of carotid endarterectomy for mild (<50%) symptomatic carotid stenosis with unstable plaque. World Neurosurg 121: e60-e69, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Iwasaki M, Kuroda S, Nakayama N, et al. : Clinical characteristics and outcomes in carotid endarterectomy for internal carotid artery stenosis in a Japanese population: 10-year microsurgical experience. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 20: 55-61, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Kashiwazaki D, Kuwayama N, Akioka N, Noguchi K, Kuroda S: Carotid plaque with expansive arterial remodeling is a risk factor for ischemic complication following carotid artery stenting. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 159: 1299-1304, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). De Rango P, Lenti M, Simonte G, et al. : No benefit from carotid intervention in fatal stroke prevention for >80-year-old patients. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 44: 252-259, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Mantese VA, Timaran CH, Chiu D, Begg RJ, Brott TG, CREST Investigators: The Carotid revascularization endarterectomy versus stenting Trial (CREST): stenting versus carotid endarterectomy for carotid disease. Stroke 41: S31-S34, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Rockman CB, Jacobowitz GR, Adelman MA, et al. : The benefits of carotid endarterectomy in the octogenarian: a challenge to the results of carotid angioplasty and stenting. Ann Vasc Surg 17: 9-14, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Kashiwazaki D, Yamamoto S, Akioka N, Kuwayama N, Noguchi K, Kuroda S: Inflammation coupling between unstable carotid plaque and spleen-A 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucos positron emission tomography study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 27: 3212-3217, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Kohta M, Oshiro Y, Yamaguchi Y, et al. : Effects of carotid revascularization on cognitive function and brain functional connectivity in carotid stenosis patients with cognitive impairment: a pilot study. J Neurosurg 139: 1010-1017, 2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Ning Y, Dardik A, Song L, et al. : Carotid revascularization improves cognitive function in patients with asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Ann Vasc Surg 85: 49-56, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Wasser K, Hildebrandt H, Gröschel S, et al. : Age-dependent effects of carotid endarterectomy or stenting on cognitive performance. J Neurol 259: 2309-2318, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Lazar RM, Wadley VG, Myers T, et al. : Baseline cognitive impairment in patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis in the CREST-2 trial. Stroke 52: 3855-3863, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Succar B, Chou YH, Hsu CH, Rapcsak S, Trouard T, Zhou W: Cognitive effects of carotid revascularization in octogenarians. Surgery 174: 1078-1082, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Spence JD, Azarpazhooh MR, Larsson SC, Bogiatzi C, Hankey GJ: Stroke prevention in older adults: recent advances. Stroke 51: 3770-3777, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]