Abstract

Cystic fibrosis (CF) has been traditionally viewed as a disease that affects White individuals. However, CF occurs among all races, ethnicities, and geographic ancestries. The disorder results from mutations in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). Varying incidence of CF is reported among Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC), who typically exhibit worse clinical outcomes. These populations are more likely to carry rare CFTR variants omitted from newborn screening panels, leading to disparities in care such as delayed diagnosis and treatment. In this study, we present a case-in-point describing an individual of Gambian descent identified with CF. Patient genotype includes a premature termination codon (PTC) (c.2353C>T) and previously undescribed single nucleotide deletion (c.1970delG), arguing against effectiveness of currently available CFTR modulator-based interventions. Strategies for overcoming these two variants will likely include combinations of PTC suppressors, nonsense mediated decay inhibitors, and/or alternative approaches (e.g. gene therapy). Investigations such as the present study establish a foundation from which therapeutic treatments may be developed. Importantly, c.2353C>T and c.1970delG were not detected in the patient by traditional CFTR screening panels, which include an implicit racial and ethnic diagnostic bias as these tests are comprised of mutations largely observed in people of European ancestry. We suggest that next-generation sequencing of CFTR should be utilized to confirm or exclude a CF diagnosis, in order to equitably serve BIPOC individuals. Additional epidemiologic data, basic science investigations, and translational work are imperative for improving understanding of disease prevalence and progression, CFTR variant frequency, genotype-phenotype correlation, pharmacologic responsiveness, and personalized medicine approaches for patients with African ancestry and other historically understudied geographic lineages.

Keywords: Cystic fibrosis, African, Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes, Diagnosis, Newborn screening, Genetics

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a lethal, autosomal recessive disorder that arises from loss-of-function variants in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). Respiratory failure remains the most prevalent cause of mortality, although people with CF also experience osteopenia [1], intestinal malabsorption [2], exocrine pancreatic insufficiency [3], and cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (CFRD) [4], among other comorbidities. The disease has been historically understudied in individuals with ancestral origins linked to non-European countries [5]. During the first nine years (2010–2018) of CF newborn screening (NBS) in the U.S., infants diagnosed with CF were 6–7% African American/Black, 13% Hispanic/Latin ethnicity (any race), and 4–5% some other race [6]. Prevalence of CF among non-White demographics has remained constant, with more recent data showing the U.S. CF population is approximately 5% African American/Black, 9.1% Hispanic/Latin (any race), and 4.2% other lineages [7]. However, these groups are frequently unrepresented in clinical trials [8], and suffer worse overall outcomes than White counterparts [9], [10], [11], [12], [13].

Furthermore, people with minoritized geographic ancestries often carry CFTR variants excluded from mutation panel(s) employed by CF NBS programs [14], [15], [16]. Examples include “nonsense” variants (categorized as CFTR “class I” defects), which prevent synthesis of full-length CFTR protein through introduction of a premature termination codon (PTC). These mutations are generally insensitive to correction by FDA-approved small molecules designed to restore CFTR function [17], [18], [19], [20], leaving many Black, Indigenous, or People of Color (BIPOC) without effective therapeutic options to address their underlying genetic defects [21]. In the present study, we discuss a case-in-point illustrated by a Gambian individual with CF, who harbors two class I CFTR variants: c.2353C>T and c.1970delG – the latter of which is a novel mutation reported here for the first time. These two variants were not detected by traditional CFTR screening panels, but instead through CFTR next-generation sequencing (NGS). Importantly, both c.2353C>T and c.1970delG are not on-label for currently available CFTR modulators. What follows is a detailed report of the patient’s first 12 years of life, together with a recent health status update at age 15 years.

Patient presentation

Initial screening

In Washington state, an African American/Black female was born via an uncomplicated vaginal delivery at 36 weeks gestation. Meconium passed on post-natal day zero. The patient presented with testing concerning for CF as evidenced by a positive NBS (immunoreactive trypsinogen 180.7 ng/mL). Sweat chloride evaluation occurred at six weeks of age (97 mmol/L). Family history did not include any known relatives with CF. A few months prior to the patient’s birth, the family emigrated from Gambia to Washington state. Both parents reported that all known family lineages trace back to Gambia. One exception was a single set of maternal great-grandparents, who were from Mali.

Diagnosis and genotyping

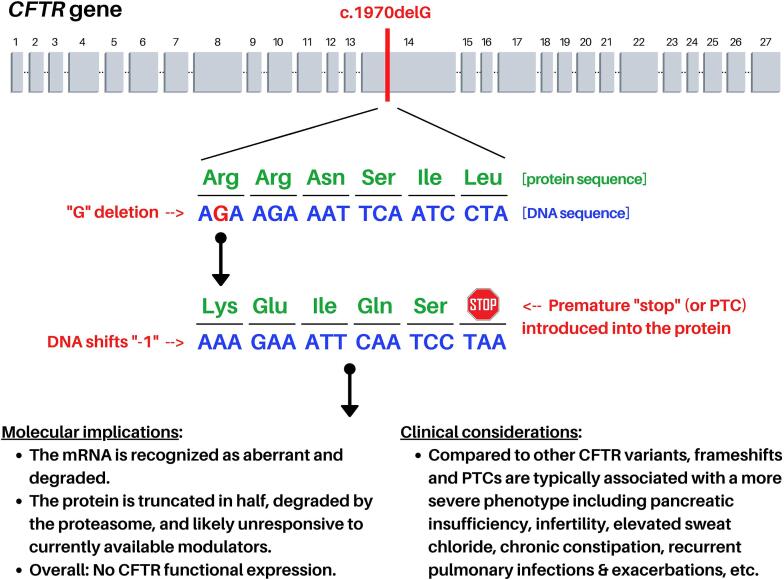

A CF diagnosis was not conferred until age 10 months (m) following multiple tiers of CFTR DNA analysis. Because the Washington NBS program did not incorporate CFTR variant evaluation until 2019, DNA testing was outsourced to Eurofins (Tucker, Georgia, USA). An initial panel screen for 23 “common” CFTR variants recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) [22] was conducted and failed to identify any mutations. Subsequent CFTR exome sequencing of all coding exons and immediate flanking regions was performed by Eurofins, which detected single copies of two protein-coding defects: c.2353C>T and c.1970delG. According to the genetic report, these variants are likely severe/pathogenic as c.2353C>T results in a PTC (p.Arg785Ter or R785X), and c.1970delG elicits a frameshift with downstream PTC (p.Arg657LysfsX5) (Fig. 1). Moreover, both mutations are not included among the 25 CFTR variants classified as non-disease causing [23], [24]. The patient was also identified as heterozygous for a synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism, c.2562T>G (p.Thr854Thr or T854T), and homozygous for two intronic repeat alleles, c.744-33GATT and c.1210–12T. Nucleotide numbering is based on GenBank accession number NM_000492. See Table 1 for a glossary of genetic terms utilized in this report.

Fig. 1.

Consequences of c.1970delG in CFTR. At CFTR chromosomal position 1970 (c.1970), deletion of the G nucleotide (delG) confers a DNA frameshift together with premature termination of the protein. Regions of CFTR DNA that encode protein (i.e. exons) are annotated as grey boxes and numbered. For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.

Table 1.

Genetic terms utilized in the present study.

| Term | Definition | References |

|---|---|---|

| Genotype | An individual's collection of genes. The term can also refer to the two alleles inherited for a particular gene. | [100] |

| Phenotype | An individual's observable traits, which may be determined by environmental factors and/or genetic contributions (i.e. genotype). | [100] |

| Chromosome | An organized package of DNA found in the nucleus of the cell. Humans possess 23 pairs of chromosomes: 22 pairs of numbered chromosomes (autosomes) and one pair of sex chromosomes (X and Y). | [100] |

| Autosomal recessive | Pattern of inheritance characteristic of some genetic diseases. “Autosomal” refers to the gene of interest being located on one of the numbered (non-sex) chromosomes. “Recessive” indicates that two copies of a variant are necessary to cause disease. | [100] |

| Allele | One of two or more versions of a gene. An individual inherits two alleles for each gene, one from each parent. If the two alleles are the same, the individual is homozygous for that gene. If the alleles are different, the individual is heterozygous. | [100] |

| Nucleotide | Basic building block of nucleic acids. A nucleotide consists of a sugar molecule (deoxyribose in DNA or ribose in RNA) attached to a phosphate group and a nitrogen-containing base. The bases present in DNA are adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T). In RNA, uracil (U) replaces thymine. | [100] |

| Base Pair | Two bases bonded to one another in a DNA helix. DNA consists of two strands twisted around each other. The two strands are held together by hydrogen bonds between the bases, with adenine pairing to thymine and cytosine pairing to guanine. | [100] |

| Variant | A permanent change in a gene’s DNA sequence that is different from what is considered the normal or “wild-type” sequence. Variants range in size from a single nucleotide to a large segment of chromosome. Variants can occur in three ways: (1) inheritance from a parent; (2) random emergence during egg or sperm formation; or (3) acquired during a person's lifetime. If a specific non-deleterious DNA change is present in at least 1% of the population, it is called a polymorphism. If the DNA change causes an abnormal protein, then it is referred to as a variant. |

[24] |

| CFTR class I mutation | A category of CFTR variants that exhibit defect(s) in production of RNA and/or full-length protein. These may include premature termination codons (see definition below), insertions/deletions (extra DNA bases are either added or missing, respectively), or splice variants (different portions of the gene are put together incorrectly), among others. | [24], [101], [102] |

| Premature termination codon (PTC; or “nonsense” mutation) | Substitution of a single base pair that leads to appearance of a stop codon where there was a codon previously specifying an amino acid. Presence of this premature termination codon results in the production of a shortened, and likely nonfunctional protein. | [100] |

| Frameshift | A type of mutation involving the insertion or deletion of a nucleotide, whereby the resulting inserted or deleted base pairs are not divisible by three. Genes are decoded in groups of three bases. Each group of three bases corresponds to one of 20 different amino acids used to build a protein. If a mutation disrupts this reading frame, then the entire DNA sequence downstream the mutation will be read incorrectly. | [100] |

| Synonymous (or “silent”) single nucleotide polymorphism | A type of polymorphism in which a single base pair is mutated, but the altered codon corresponds to the same amino acid in the normal or “wild-type” sequence. | [100] |

| Exon | The portion of a gene that encodes amino acids and is therefore expressed in the protein product. In higher eukaryotes, most exons are separated by one or more non-coding DNA sequences termed introns. These segments are not expressed in the protein as they are excised out. | [100] |

| Intron | The portion of a gene that does not encode amino acids. | [100] |

| Targeted (or “traditional”) CFTR screening | Screening performed using a panel of 23 CFTR variants recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics. These variants have been shown to cause CF, both through clinical and laboratory evaluation. The list represents many of the most frequently observed CFTR variants in U.S. populations of European descent. | [22], [24], [78] |

| Next-generation sequencing | A high-throughput method used to determine the exact sequence of bases (A, C, G, T) in a DNA molecule. The technique is capable of processing multiple DNA strands in parallel to sequence an individual’s genome, for example. The two most common approaches include: whole exome sequencing, which only covers protein-coding regions (i.e. exons); and (2) whole genome sequencing, which covers both exons and non-protein coding regions (i.e. introns). | [100] |

| CFTR modulators | Small molecules that correct the underlying genetic defect(s) caused by CFTR variants. These drugs are clinically approved in several countries for specific variants, or groups of variants, that introduce abnormalities in CFTR functional expression. | [18], [24], [101], [103] |

| c.2562T>G (p.Thr854Thror T854T) | A CFTR variant at position 2562 in the gene’s DNA, in which thymine is mutated to guanine. In the corresponding protein sequence at position 854, the encoded “wild-type” amino acid, threonine (Thr) remains unaltered. Therefore, this variant is classified as a synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism. | [24], [104], [105] |

| c.2353C>T (p.Arg785Ter or R785X) | A CFTR variant at position 2353 in the gene’s DNA, in which cytosine is mutated to thymine. In the corresponding protein sequence at position 785, the encoded “wild-type” amino acid, arginine (Arg), is replaced by a premature termination codon (X). Therefore, this variant is classified as a nonsense mutation. | [24], [106] |

| c.1970delG (p.Arg657LysfsX5) | A CFTR variant at position 1970 in the gene’s DNA, in which a single guanine nucleotide is deleted and therefore causes a frameshift (fs). In the corresponding protein sequence at position 657, the encoded “wild-type” amino acid, arginine (Arg), is changed to lysine (Lys). In addition, a premature termination codon is introduced five amino acids downstream (X5). Therefore, this variant is classified as a frameshift mutation. | This study |

Pulmonary phenotype

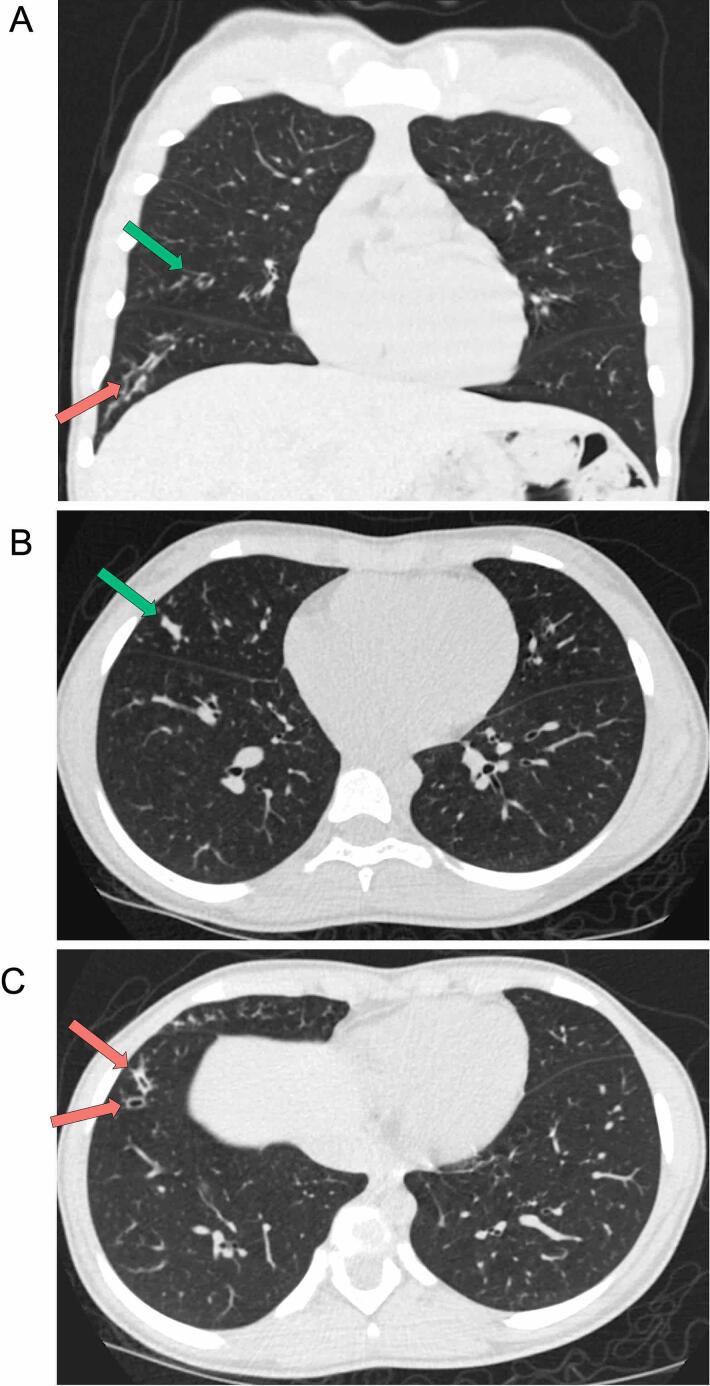

The patient was first hospitalized at age 4m with bronchiolitis and an acute pulmonary exacerbation (APE) compounded by reactive airway disease. This event triggered initiation of pulmonary treatments described in Table 2. Five subsequent APEs requiring hospitalization occurred at ages 3.2 years (y), 5.3y, 9.2y, 9.8y, and 10.7y. During each APE, treatment included antibiotics, chest physiotherapy, and/or oral steroids. A routine chest CT at age 11.8y identified mild cylindrical bronchiectasis and mucus plugging (Fig. 2). Recent measurements of percent predicted forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) exhibited the following decline: 95% (10y), 91% (11y), 92.75% (12y), 86.75% (13y), 83% (14y), 72% (15y).

Table 2.

Summary of clinical findings and interventions. Occurrence of an individual treatment is annotated as acute (a), daily (d), or weekly (w). Administration frequency is indicated as (x).

| Organ system | Manifestation | Age(s) of occurrence | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary | Bronchiolitis | 4m | − Albuterol (d; 2x) − 7% hypertonic saline (d; 2x) − Dornase alfa (d; 1x) − Chest physiotherapy (d; 2x) |

| APE | 4m, 3.2y, 5.3y, 9.2y, 9.8y, 10.7y | − Antibiotics (a) − Oral steroids (a) − All interventions listed above for Bronchiolitis |

|

| Cylindrical bronchiectasis | 11y | − Azithromycin (w; 3x) | |

| Endocrine | Abnormal HbA1C | 4y | − None |

| CFRD | 6y | − Insulin (d; 4x or more) | |

| Vitamin D deficiency | 7y | − Vitamin D3 (w; 1x) | |

| Gastrointestinal | Pancreatic insufficiency | 2m | − Enzyme replacement (d; with food) − Multivitamins (d) |

| Chronic constipation | 2m | − Osmotic laxatives (d; 1x) | |

| Transaminitis | 3y | − Resolved without intervention | |

| Appendicitis | 6y | − Appendectomy (a) | |

| Musculoskeletal | Scoliosis | 9y | − Monitored without intervention |

| Cardiovascular | Deep vein thrombosis | 9.8y | − Subcutaneous enoxaparin (a) |

| Sinus | Chronic sinusitis with polyps | 11y | − Polypectomy (a) − Intranasal steroid (d; 1x) − Sinus rinse (d; 1x) − Oral antihistamine (d; 1x) |

| Neurological | Restless leg syndrome | 12y | − Iron (d; 1x) |

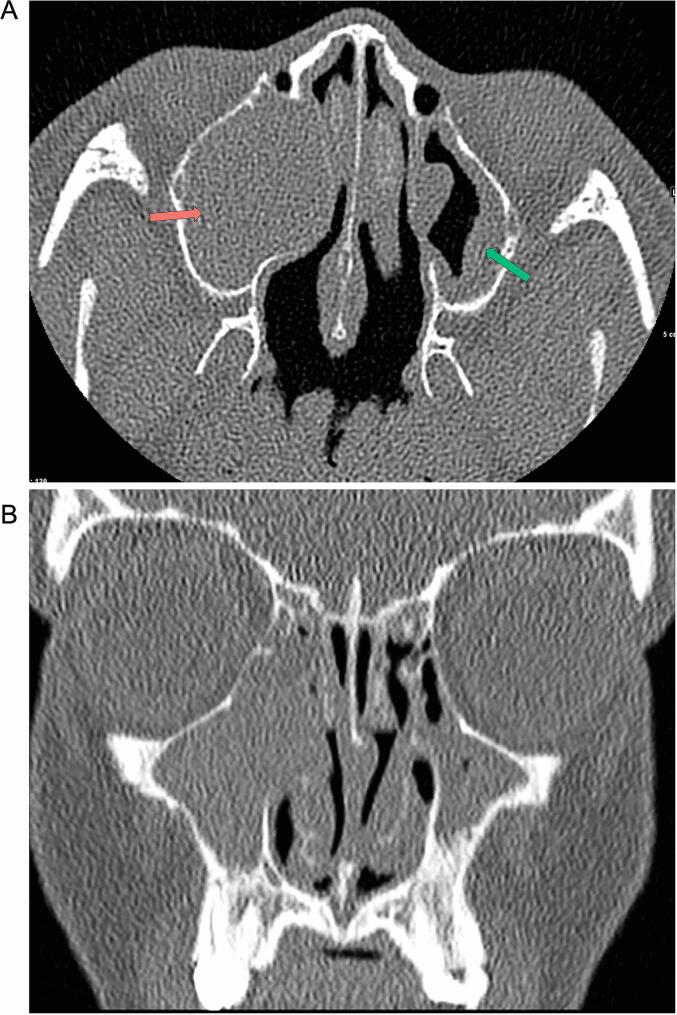

Fig. 2.

Chest CT at 11.8y identifies pathological respiratory features. Mild bronchiectasis (right lower lobe, red arrows) and mucus plugging (right middle lobe, green arrows) are demonstrated on coronal (A) and axial (B-C) views. For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.

Microbiology

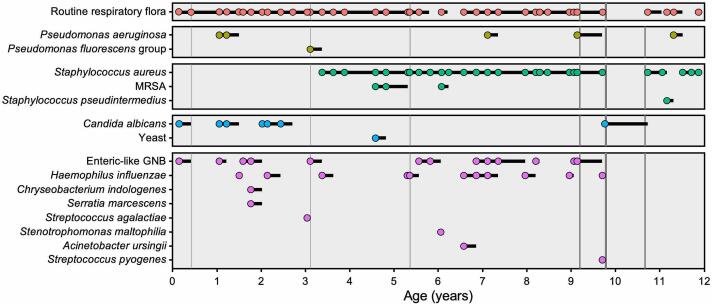

Repetitive Pseudomonas aeruginosa, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and Candida albicans infections have been noted (Fig. 3). Infections of P. aeruginosa initiated at age 12m and recurred at ages 7.1y, 9.2y, and 11.3y – all of which were cleared with nebulized tobramycin. Intermittent cultures have been positive for other flora including Haemophilus influenzae, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus agalactiae, Serratia marcescens, Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, Acinetobacter ursingii, Chryseobacterium indologenes, Pseudomonas fluorescens group, enteric-like gram-negative bacteria, and yeast (Fig. 3). At age 13.8y, Burkholderia cepacia complex was detected when the patient was admitted to the emergency room for hyperglycemia. She received treatment with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and levofloxacin. At age 14.1y, the patient was hospitalized with an APE and cultured B. cepacia complex. Meropenem and levofloxacin were administered, and the patient has remained culture-negative for B. cepacia complex since then.

Fig. 3.

Microbial and related pulmonary manifestations over time. Pathogenic cultures show varying microbial taxa since birth. Solid black horizontal lines indicate inferred microbial presence. Vertical grey bars denote APEs (six in total), with line thickness representing length of hospitalization. MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; GNB, Gram-negative bacillus. For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.

Endocrine manifestations

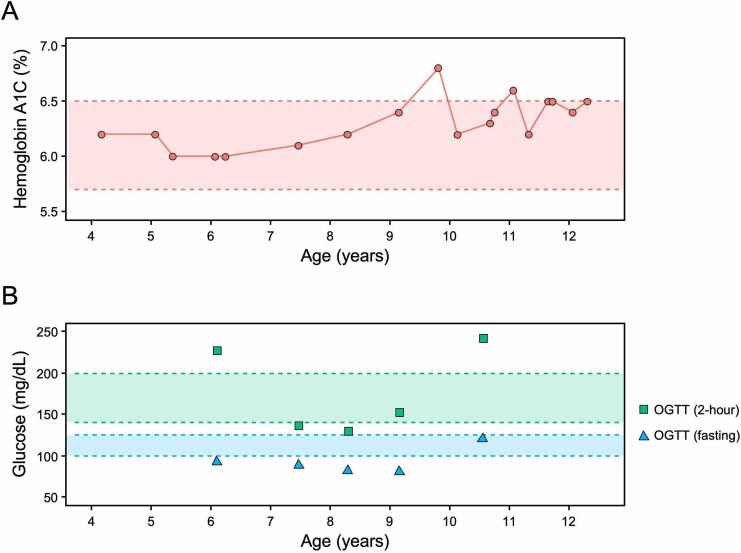

Dysglycemia was first noted at age 4.2y as evidenced by an abnormal hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) of 6.2% (Fig. 4A). The patient was diagnosed with CFRD at age 6.1y, with an elevated screening oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) of 228 mg/dL (2-hour glucose) (Fig. 4B). At diagnosis, blood glucose levels were largely within target range (Supplementary Fig. 1), coupled with excellent weight gain and linear growth. Thus, insulin therapy was not needed. Subsequent OGTTs were normal despite pre-diabetic HbA1C levels (Fig. 4). During hospitalization for an APE at age 9.8y, hyperglycemia occurred and required temporary insulin therapy. Following hospital admission for an ensuing APE (age 10.6y), daily insulin injections were initiated. Until B. cepacia complex was initially cultured (age 13.8y), CFRD was well-controlled using an insulin pump with hybrid closed-loop system (average HbA1c 6.5%). Since that time, the patient’s endocrine health has steadily declined, with her most recent HbA1c measured at 13.4% (15y). Notably, many family members have type two diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Fig. 4.

HbA1C and OGTT results show persistent dysglycemia beginning at 4.2y. (A) Pre-diabetic ranges are highlighted for HbA1C (5.7–6.5%; red). (B) Impaired glucose tolerance (140–200 mg/dL; green) and fasting glucose (100–126 mg/dL; blue) are indicated. From the time of CFRD diagnosis (age 6.1y) until B. cepacia was first detected (age 13.8y), HbA1c remained within target (<7%). For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.

Gastrointestinal findings

At age 2m, the patient exhibited weight loss and chronic constipation. She was diagnosed with pancreatic insufficiency, at which point pancreatic enzyme replacement and multivitamin therapies commenced. Signs of salt wasting were not detected. During hospitalization for an APE (age 3.2y), elevated liver enzymes were noted (aspartate transaminase, 77 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 73 U/L). However, hepatic ultrasound was normal, and liver enzymes normalized within months.

Other comorbidities

Chest radiographs obtained for pulmonary care (age 9y) showed mild scoliosis (Fig. 5). At age 11.3y, sinus CTs revealed chronic sinusitis with nasal polyps (Fig. 6).

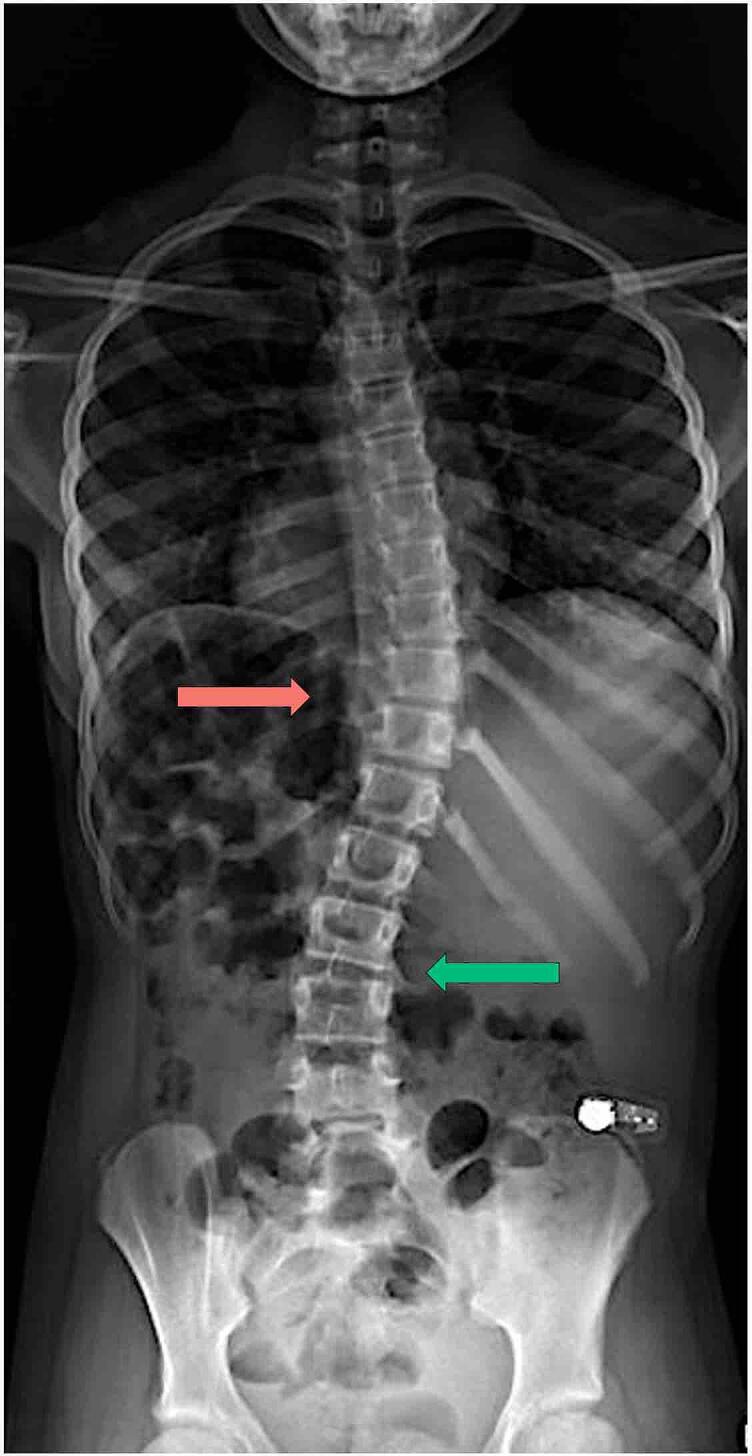

Fig. 5.

Standing radiograph depicts mild scoliosis (age 11.9y). Findings include dextrocurvature of the thoracic spine (19°) (red) and levocurvature of the thoracolumbar spine (21°) (green). Scoliosis was first incidentally noted from chest radiographs conducted for routine pulmonary care at age 9.2y. For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.

Fig. 6.

Sinus CT at 11.3y reveals pansinusitis disease most pronounced in the maxillary sinus. (A) Axial view is notable for mucocele causing complete opacification of the right maxillary sinus (red arrow) and mucosal thickening (green arrow). (B) Coronal view demonstrates patchy mucosal thickening throughout the ethmoid sinuses. For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.

Treatments and outcomes

The patient is currently 15 years of age. Daily interventions include laxatives, intranasal steroids, sinus rinses, antihistamines, iron, pancreatic enzyme replacement, insulin, and chest physiotherapy with nebulized albuterol, 7% hypertonic saline, and dornase alfa (Table 2). Azithromycin is administered three times per week, and vitamin D3 is given once weekly. Pulmonary function decline is accelerated for an individual of the patient’s age, with FEV1 presently at 72% predicted. No digital clubbing has been observed to date. Although the patient has an automated insulin delivery device, CFRD is not well-managed (HbA1C 13.4%). It has been difficult for her to maintain therapy as prescribed due to barriers. Vitamin D deficiency persists, with 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels at 18.4 ng/mL. Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry shows normal bone mineral density (age 15y). Since age 12y, body mass index has been consistently above the 50th percentile. The patient runs track to maintain high exercise activity. She remains ineligible for CFTR modulators, since the c.2353C>T and c.1970delG variants are not on-label for these FDA-approved small molecules.

Discussion

Highlighting the importance of CF endocrine, pulmonary, and genetic interactions

Incidence of CF among African Americans is ∼1:15,000 [14], [25], [26]. In Africa, lack of epidemiological data has prevented estimation of CF disease prevalence within specific countries and/or across the continent [5], [27], [28]. Sporadic reports of CF have occurred in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Sudan, Rwanda, Senegal, Cameroon, Namibia, Zimbabwe, and South Africa [27]. Although health professionals may have recognized the pathology in other countries, insufficient support for CF diagnosis, evaluation, treatment, and/or scientific publication likely contributes to under-reporting. Here, we describe a novel case of CF documented in a patient with established Gambian ancestry who encodes a new CFTR variant, c.1970delG. This finding is substantial, since the individual is a first-generation American citizen, whose parents emigrated from Gambia to the U.S. shortly before the patient’s birth. Therefore, it is likely that c.1970delG is indigenous to the African diaspora and represents a unique CFTR variant associated with the Gambian population.

The patient exhibits both common and unique features of CF disease. Atypical aspects of clinical course include appendicitis and scoliosis, which among CF populations, demonstrate frequencies of ∼1.5% [29] and 9.9–15.5% [30], respectively. Of higher concern is the patient’s unusually rapid speed of pulmonary health decline. Between the ages of 10y to 15y, her FEV1 deteriorated by 23% predicted, i.e. a rate of –3.83 percentage points per year. This change is considerably worse than a recent report showing patients 12y and older, who are served at the same CF Care Center and also not receiving modulators, exhibit a mean annualized rate of –1.92 percentage points in FEV1% predicted [31]. At age 15y, the patient’s FEV1 of 72% predicted is well below the national average of ∼99% predicted for adolescents from the same birth cohort (2008–2012) and children ages 6-18y with a similar BMI (50th percentile) [7].

Additionally, the patient’s respiratory cultures have shown comparatively rare, and significant, pathogens atypical for her age. In the 2022 U.S. CF Foundation Patient Registry, infection rates are described for CF-associated bacteria such as P. aeruginosa (26%), MRSA (15.6%), S. maltophilia (5%), and B. cepacia complex (1.3%) [7]. The patient in this report has cultured all of these pathogens, with B. cepacia complex the most surprising, as this family of bacteria is detected in less than 1% of CF adolescents aged 11-17y [7]. It has been well-established that infection with P. aeruginosa or B. cepacia complex is associated with accelerated pulmonary decline and higher mortality rate among people with CF [32], [33], [34]. Thus, these two pathogens have likely contributed to the patient’s increased frequency of APEs – i.e. six before the age of 12y. National data indicate that only ∼3% of 12-year-olds with CF have experienced two or more APEs [7].

The patient’s early-onset CFRD is also relatively unusual, as this comorbidity affects only 4.5% of the U.S. CF pediatric population [7]. Factors associated with increased risk for CFRD include female sex, pancreatic insufficiency, class I CFTR variants, frequent APEs, and CF liver disease [35], [36], [37]. The patient displays all of these traits with the exception of CF liver disease. Furthermore, the patient possesses a family history of T2DM. Growing evidence indicates the latter finding is a significant risk factor for CFRD, as reports have linked susceptibility genes for T2DM to CFRD [38], [39]. Prevalence of T2DM among adolescents has increased substantially in recent years, particularly within African Americans/Blacks and Hispanics/Latinos [40]. These CF populations may be subject to enhanced risk for CFRD, although robust clinical studies would be required to investigate the hypothesis.

Taken together, the patient in the current study exhibits advanced endocrine and pulmonary disease progression that is likely influenced by the afore-mentioned airway pathogens, challenges with adherence to the prescribed insulin pump-based therapy, and other factors discussed below. Numerous chronic respiratory conditions are associated with worsened lung function when diabetes is present as a comorbidity [41], [42], [43], [44]. In the context of CF, CFRD leads to increased occurrences of APEs, together with a six-fold higher risk of mortality [45], [46], [47], [48]. While a direct link between CFRD and pulmonary dysfunction has not been fully elucidated, evidence indicates that sustained elevation of blood glucose may contribute to impaired respiratory immunity [49], increased luminal bacterial growth [50], [51], and structural changes to the lungs [50], [52]. Many of these features were observed for the patient, including pulmonary bronchiectasis, frequent APEs, steadily declining FEV1, and repetitive microbial infections.

The patient’s poor clinical status is also impacted by the two severe CFTR variants encoded, c.1970delG and c.2353C>T (R785X). Both variants ultimately confer PTCs that lead to prematurely degraded CFTR mRNA and protein, resulting in no anticipated CFTR function. Although c.1970delG is a newly described variant, R785X has been established as CF-causing since 2013 [24]. R785X occurs among diverse geographic populations identified in Tunisia, Russia, China, Europe, and Ecuador [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], and is presently reported among 31 individuals in the U.S. CFTR2 database [24]. Among the U.S. patients who possess R785X and a second CF-causing variant, clinical data show the following averages: (1) 100% pancreatic insufficient; (2) sweat chloride 98 mmol/L; (3) FEV1 ∼80% predicted (age 10-20y) or ∼60% predicted (older than 20y); and (4) P. aeruginosa infection rate of 48%. These characteristics are nearly identical to those exhibited by the patient described herein.

Compounded with the issues noted above, the patient’s CFTR genotype renders her ineligible for modulators. Both c.1970delG and R785X are off-label for these clinically approved small molecules, thus omitting any potential benefits of the drugs that could be enacted upon disease progression. Patients receiving CFTR modulators have experienced improvement in clinical endpoints such as weight gain and augmented lung function, although outcomes with regard to CFRD pathogenesis have not been well-delineated [58]. Improved understanding of genetic factors and molecular mechanisms that contribute to CFRD pathogenesis, as well as impact of CFTR modulators on the pathways involved, represent important understudied areas of research.

Addressing racial and ethnic inequities during CF diagnosis

Despite an out-of-range NBS, the patient in this study experienced several delays in the journey to diagnosis. An initial referral for sweat chloride evaluation was provided, although this test was not performed until six weeks of age. Long-standing practice guidelines from the U.S. CF Foundation and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that sweat chloride analysis occur at 10 days of age or shortly thereafter [59], [60], [61]. At six weeks, the patient’s sweat chloride levels were well above the diagnostic threshold of 60 mmol/L, which should have resulted in a presumptive CF diagnosis but did not. The family was instead referred for a second sweat test and genetic testing, and this process encompassed approximately eight months. The extended duration was attributable to the following: (1) CFTR mutation analysis was not offered in Washington state at the time of the patient’s evaluation, requiring outsourcing to a laboratory on the other side of the country (Georgia); and (2) initial CFTR panel screening did not detect the c.1970delG and c.2353C>T variants, necessitating collection, shipping, processing, and analysis of a second blood specimen.

Notwithstanding elevated immunoreactive trypsinogen and sweat chloride concentrations, the patient did not receive a confirmed CF diagnosis until detection of two CFTR variants. This occurred at 10 months of age, representing a clinically significant delay [62]. The guideline for Diagnosis of CF in Screened Populations [63] states that a positive NBS and sweat chloride value of 60 mmol/L or greater confirms a CF diagnosis. Identification of CFTR genotype is not listed as a requirement for diagnosis but appears to have been utilized in this manner by clinicians involved in the present case. This approach is inappropriate and causes unnecessary diagnostic delays as illustrated by the patient’s experience. Prior work has established that CF diagnosis after six weeks of age significantly increases risk of irreparable damage to lung tissues [61], [64], i.e. the leading cause of mortality among CF populations. The patient’s progressive pulmonary decline likely would have been improved by standard-of-care CF therapies introduced earlier in life.

Lack of urgency was apparent during the patient’s CF diagnostic testing, which was likely impacted, at least in part, by multiple factors rooted in racial bias. Numerous reports indicate that clinical care teams incorrectly ascribe CF as a “White disease” and suggest that the diagnosis is unlikely for BIPOC individuals, even those with a positive CF NBS [65], [66], [67], [68]. This type of rhetoric is extremely harmful to patient outcomes. CF occurs in all races, ethnicities, and geographic ancestries. Regardless of demographic, aggressive “CF” management should be pursued once clinical presentation raises suspicion for the condition.

For African American/Black patients in particular, racial biases during CF NBS are influenced by a single study – cited in many CF clinical education programs – that suggests individuals with African ancestry frequently exhibit high immunoreactive trypsinogen levels without the presence of CF [69]. However, the algorithm employed in this work included second-tier testing with a repeat measurement of immunoreactive trypsinogen and genetic screening of just 32 CFTR variants [70]. Third-tier sweat testing was only conducted for infants who screened positive in the second-tier with consistently elevated immunoreactive trypsinogen levels (e.g. above 170 ng/mL or an ultrahigh reading in the top 0.2%) and one or two identified CFTR variants. The genetic panel utilized did not include numerous variants that exhibit increased prevalence among the African diaspora, such as 2307insA, A559T, D1270N, G330X, S466X, or 1812-1G>A [14]. It is therefore possible that a CF diagnosis was missed for many of the African American/Black patients without a CFTR variant detected during second-tier screening.

Although CF NBS has been implemented across the U.S. since 2010, states’ algorithms have differed and not always incorporated CFTR variant analysis. Among programs that do employ DNA testing, utilization of panels with specific CFTR mutations – predominantly encoded by individuals of European ancestry [22] – are known to contribute to missed and/or late CF diagnoses among BIPOC populations [10], [25], [67], [71], [72]. Recent analysis of the U.S. CF Foundation Patient Registry revealed that targeted CFTR screening using the ACMG 23-variant panel would not identify the full CFTR genotype for 56.3% of Hispanics/Latinos, 68.4% of African Americans/Blacks, 34.7% of Alaskan Natives/Indians, 74.7% of Asians, 28.6% of Hawaiian Pacific Islanders, and 49.2% of mixed races [73]. Combined with the issue that non-White individuals largely possess CFTR variants excluded from modulator labels [10], [14], [16], [21], [25], [74], [75], [76], [77], either due to confirmation of unresponsiveness or absence of testing, these CF communities experience distinctly elevated risk.

The ACMG has formally recognized the need for expansion of CFTR variant testing in NBS programs [78], which can be achieved through NGS techniques that capture mutations in agnostic fashion. Simply incorporating additional subset(s) of CFTR variants into panels based on predicted racial/ethnic composition among local populations would be inappropriate, as race and ethnicity are not biological variables but social constructs. Such approaches also assume accurate self-described ancestral origins provided by test subjects, which are not always known (e.g. due to genomic admixture, including consequences of historical slave trades). In addition, 2,119 CFTR variants have been reported [17], [23], a fraction of which have been established as disease-causing (719), varying clinical consequence (49), or unknown significance (11). Therefore, determining which CFTR variants are essential for inclusion presents a substantial challenge.

To reduce racial and ethnic health disparities predicated upon delays in diagnosis and treatment, we recommend that a sweat test is performed for any infant displaying high immunoreactive trypsinogen levels, even if zero CFTR variants are identified on a limited genetic panel. This is particularly important in the setting of individuals with non-European ancestry, which contributed to the detection of CF in the patient described in the present study. We also suggest CF NBS algorithms utilize first-tier immunoreactive trypsinogen measurement, followed by second-tier sweat chloride evaluation together with CFTR variant identification by NGS. CFTR sequencing would remove the racial/ethnic diagnostic biases intrinsic to limited CFTR variant panels, as these tests are comprised of mutations largely observed in people of European ancestry [14], [15], [16].

CF NBS algorithms that employ NGS have been successfully demonstrated by various programs since 2016 [79], [80], [81], [82], [83]. Blood samples undergo NGS analysis using an Illumina MiSeqDx CF Assay, for example, with accompanying software that identifies 139 CF-causing mutations. A variant-call pipeline also incorporates hundreds of additional variants classified as disease-causing [23], [24]. In cases with one CF-causing variant detected and a sweat chloride value greater than 30 mmol/L, NGS data may be re-analyzed by removing preset limitations to allow viewing of all CFTR variants. Thus, demonstrated feasibility of the approach supports broad utilization of NGS as a confirmatory test in CF NBS programs.

As illustrated by current findings, overcoming racial/ethnic inequities intrinsic to CF screening, diagnosis, and treatment remains a significant unmet medical need. It must be acknowledged that these processes are affected by systemic racism, which is embedded in nearly every thread of U.S. society. Meta-analysis of 293 studies conducted predominantly in the U.S. over a 30-year span (1983–2013) shows that racism is associated with poor physical and psychological health outcomes [84]. Adolescents with CF are two-to-three times more likely to develop anxiety and depression compared to the general population [85], [86], which adversely affect clinical endpoints such as quality of life, disease self-management, and survival [87], [88], [89], [90]. Mental health outcomes among youth are also negatively influenced by generational poverty, violence, and trauma, which are more prevalent among BIPOC populations due to historical and present-day structural racism [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98]. Such inequities, together with other racial/ethnic biases discussed earlier, undoubtedly shaped the patient experience described herein.

Improving equitable CF care delivery will require a sustained, multifaceted approach informed by community engaged research. Recent efforts in this arena have produced mutually reinforcing feedback from different African American/Black patient groups [68], [99], in which calls to action for CF care teams, researchers, and community organizations have been formalized. Recommended initiatives include but are not limited to the following:

-

(1)

provide education on, and advocate for, best practices regarding unbiased CF NBS and diagnosis;

-

(2)

make available information and resources to minoritized patients struggling to receive a CF diagnosis and/or access to care;

-

(3)

deliver training to care teams for better understanding of racial/ethnic CF health disparities;

-

(4)

promote culturally competent care practices that augment health equity and are personalized to the unique experiences of distinct BIPOC populations with CF;

-

(5)

support pipelines that diversify the CF workforce, as a means to enhance the number of BIPOC physicians and other clinical staff serving minoritized patients;

-

(6)

facilitate reoccurring community listening sessions composed of BIPOC with CF;

-

(7)

increase BIPOC representation on committees developing CF clinical care guidelines; and

-

(8)

feature BIPOC patients in pamphlets and other materials utilized for CF education of care providers and families.

In the future, larger-scale studies will be required to garner a comprehensive understanding of unique challenges faced by distinct groups of minoritized races and ethnicities with CF. This work will be necessary to develop interventions tailored to each population, in order to equitably improve outcomes for all people living with CF.

Funding

This study was supported by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF; WU20D0, WU21Q0, WU23GE0, OLIVER22A0-KB, LINNEM22QI0) and National Institutes of Health (NIH; R00HL151965, R21DK128731, UL1TR002378). CFF and NIH did not play a role in the design or conduct of the study.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Malinda Wu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. Jacob D. Davis: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Data curation. Conan Zhao: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Tanicia Daley: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Data curation, Funding acquisition. Kathryn E. Oliver: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Data curation, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express sincere gratitude to the patient and her family for providing written consent for this case report, as well as Dr. Ajay Kasi and other CF care team members for technical assistance. We would also like to thank Drs. Rachel Linnemann, Eric Sorscher, Joanna Goldberg, Arlene Stecenko, Nael McCarty, and the CF Scholars Program (affiliate of the Emory-Children’s CF Center of Excellence) for thoughtful discussions.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcte.2024.100344.

Contributor Information

Malinda Wu, Email: mwu86@jhmi.edu.

Jacob D. Davis, Email: jacob.davis@nih.gov.

Conan Zhao, Email: zhao.conan@mayo.edu.

Tanicia Daley, Email: tanicia.daley@emory.edu.

Kathryn E. Oliver, Email: kolive3@emory.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Stalvey M.S., Clines G.A. Cystic fibrosis-related bone disease: insights into a growing problem. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20:547–552. doi: 10.1097/01.med.0000436191.87727.ec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li L., Somerset S. Digestive system dysfunction in cystic fibrosis: challenges for nutrition therapy. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:865–874. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walkowiak J., Herzig K.H., Witt M., Pogorzelski A., Piotrowski R., Barra E., et al. Analysis of exocrine pancreatic function in cystic fibrosis: one mild CFTR mutation does not exclude pancreatic insufficiency. Eur J Clin Invest. 2001;31:796–801. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moran A., Brunzell C., Cohen R.C., Katz M., Marshall B.C., Onady G., et al. Clinical care guidelines for cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and a clinical practice guideline of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, endorsed by the Pediatric Endocrine Society. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2697–2708. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padoa C, Goldman A, Jenkins T, Ramsay M. Cystic fibrosis carrier frequencies in populations of African origin. J Med Genet 1999;36:41-4. No DOI available. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Martiniano S.L., Elbert A.A., Farrell P.M., Ren C.L., Sontag M.K., Wu R., et al. Outcomes of infants born during the first 9 years of CF newborn screening in the United States: a retrospective Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry cohort study. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56:3758–3767. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry Annual Data Report. 2022. https://www.cff.org/medical-professionals/patient-registry accessed 20 November 2023.

- 8.McGarry M.E., McColley S.A. Minorities are underrepresented in clinical trials of pharmaceutical agents for cystic fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:1721–1725. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201603-192BC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buu M.C., Sanders L.M., Mayo J.A., Milla C.E., Wise P.H. Assessing differences in mortality rates and risk factors between hispanic and non-hispanic patients with cystic fibrosis in California. Chest. 2016;149:380–389. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart C., Pepper M.S. Cystic fibrosis in the african diaspora. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:1–7. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201606-481FR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rho J., Ahn C., Gao A., Sawicki G.S., Keller A., Jain R. Disparities in mortality of hispanic patients with cystic fibrosis in the United States. A national and regional cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:1055–1063. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201711-2357OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGarry M.E., Neuhaus J.M., Nielson D.W., Burchard E., Ly N.P. Pulmonary function disparities exist and persist in Hispanic patients with cystic fibrosis: a longitudinal analysis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52:1550–1557. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGarry M.E., Williams W.A., 2nd, McColley S.A. The demographics of adverse outcomes in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019;54(Suppl 3):S74–S83. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schrijver I., Pique L., Graham S., Pearl M., Cherry A., Kharrazi M. The spectrum of CFTR variants in nonwhite cystic fibrosis patients: implications for molecular diagnostic testing. J Mol Diagn. 2016;18:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zampoli On Behalf Of The Msac M. Cystic fibrosis: What's new in South Africa in 2019. S Afr Med J 2018;109:16-9. 10.7196/SAMJ.2018.v109i1.13415. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Januska M.N., Marx L., Walker P.A., Berdella M.N., Langfelder-Schwind E. The CFTR variant profile of Hispanic patients with cystic fibrosis: Impact on access to effective screening, diagnosis, and personalized medicine. J Genet Couns. 2020;29:607–615. doi: 10.1002/jgc4.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCague A.F., Raraigh K.S., Pellicore M.J., Davis-Marcisak E.F., Evans T.A., Han S.T., et al. Correlating cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator function with clinical features to inform precision treatment of cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:1116–1126. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201901-0145OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliver K.E., Han S.T., Sorscher E.J., Cutting G.R. Transformative therapies for rare CFTR missense alleles. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2017;34:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2017.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aksit M.A., Bowling A.D., Evans T.A., Joynt A.T., Osorio D., Patel S., et al. Decreased mRNA and protein stability of W1282X limits response to modulator therapy. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18:606–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michaels W.E., Bridges R.J., Hastings M.L. Antisense oligonucleotide-mediated correction of CFTR splicing improves chloride secretion in cystic fibrosis patient-derived bronchial epithelial cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:7454–7467. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGarry M.E., McColley S.A. Cystic fibrosis patients of minority race and ethnicity less likely eligible for CFTR modulators based on CFTR genotype. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56:1496–1503. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grody W.W., Cutting G.R., Klinger K.W., Richards C.S., Watson M.S., Desnick R.J. Laboratory standards and guidelines for population-based cystic fibrosis carrier screening. Genet Med. 2001;3:149–154. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200103000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sosnay P.R., Siklosi K.R., Van Goor F., Kaniecki K., Yu H., Sharma N., et al. Defining the disease liability of variants in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1160–1167. doi: 10.1038/ng.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Clinical and Functional TRanslation of CFTR (CFTR2). https://cftr2.org/ [accessed 20 November 2023].

- 25.Sugarman E.A., Rohlfs E.M., Silverman L.M., Allitto B.A. CFTR mutation distribution among U.S. Hispanic and African American individuals: evaluation in cystic fibrosis patient and carrier screening populations. Genet Med. 2004;6:392–399. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000139503.22088.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nappo S., Mannucci L., Novelli G., Sangiuolo F., D'Apice M.R., Botta A. Carrier frequency of CFTR variants in the non-Caucasian populations by genome aggregation database (gnomAD)-based analysis. Ann Hum Genet. 2020;84:463–468. doi: 10.1111/ahg.12396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart C., Pepper M.S. Cystic fibrosis on the African continent. Genet Med. 2016;18:653–662. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Owusu S.K., Morrow B.M., White D., Klugman S., Vanker A., Gray D., et al. Cystic fibrosis in black African children in South Africa: a case control study. J Cyst Fibros. 2020;19:540–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2019.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shields M.D., Levison H., Reisman J.J., Durie P.R., Canny G.J. Appendicitis in cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66:307–310. doi: 10.1136/adc.66.3.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mataliotakis G.I., Tsirikos A.I., Pearson K., Urquhart D.S., Smith C., Fall A. Scoliosis surgery in cystic fibrosis: surgical considerations and the multidisciplinary approach of a rare case. Case Rep Orthop. 2016;2016:7186258. doi: 10.1155/2016/7186258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee T., Sawicki G.S., Altenburg J., Millar S.J., Geiger J.M., Jennings M.T., et al. Effect of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor on annual rate of lung function decline in people with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2023;22:402–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2022.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muhdi K., Edenborough F.P., Gumery L., O'Hickey S., Smith E.G., Smith D.L., et al. Outcome for patients colonised with Burkholderia cepacia in a Birmingham adult cystic fibrosis clinic and the end of an epidemic. Thorax. 1996;51:374–377. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.4.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LiPuma J.J., Spilker T., Gill L.H., Campbell P.W., 3rd, Liu L., Mahenthiralingam E. Disproportionate distribution of Burkholderia cepacia complex species and transmissibility markers in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:92–96. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.1.2011153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Courtney J.M., Bradley J., McCaughan J., O'Connor T.M., Shortt C., Bredin C.P., et al. Predictors of mortality in adults with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42:525–532. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marshall B.C., Butler S.M., Stoddard M., Moran A.M., Liou T.G., Morgan W.J. Epidemiology of cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. J Pediatr. 2005;146:681–687. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adler A.I., Shine B.S., Chamnan P., Haworth C.S., Bilton D. Genetic determinants and epidemiology of cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: results from a British cohort of children and adults. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1789–1794. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perrem L., Stanojevic S., Solomon M., Carpenter S., Ratjen F. Incidence and risk factors of paediatric cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18:874–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2019.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blackman S.M., Hsu S., Ritter S.E., Naughton K.M., Wright F.A., Drumm M.L., et al. A susceptibility gene for type 2 diabetes confers substantial risk for diabetes complicating cystic fibrosis. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1858–1865. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1436-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aksit M.A., Pace R.G., Vecchio-Pagán B., Ling H., Rommens J.M., Boelle P.Y., et al. Genetic modifiers of cystic fibrosis-related diabetes have extensive overlap with type 2 diabetes and related traits. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:1401–1415. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgz102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dabelea D., Mayer-Davis E.J., Saydah S., Imperatore G., Linder B., Divers J., et al. Prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among children and adolescents from 2001 to 2009. J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311:1778–1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baker E.H., Janaway C.H., Philips B.J., Brennan A.L., Baines D.L., Wood D.M., et al. Hyperglycaemia is associated with poor outcomes in patients admitted to hospital with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2006;61:284–289. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.051029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greulich T., Nell C., Hohmann D., Grebe M., Janciauskiene S., Koczulla A.R., et al. The prevalence of diagnosed α1-antitrypsin deficiency and its comorbidities: results from a large population-based database. Eur Respir J. 2017;49 doi: 10.1183/13993003.00154-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peters M.C., Mauger D., Ross K.R., Phillips B., Gaston B., Cardet J.C., et al. Evidence for exacerbation-prone asthma and predictive biomarkers of exacerbation frequency. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:973–982. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201909-1813OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kruglikov I.L., Shah M., Scherer P.E. Obesity and diabetes as comorbidities for COVID-19: underlying mechanisms and the role of viral-bacterial interactions. Elife. 2020;9 doi: 10.7554/eLife.61330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khare S., Desimone M., Kasim N., Chan C.L. Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: prevalence, screening, and diagnosis. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2022;27 doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2021.100290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moran A., Hardin D., Rodman D., Allen H.F., Beall R.J., Borowitz D., et al. Diagnosis, screening and management of cystic fibrosis related diabetes mellitus: a consensus conference report. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1999;45:61–73. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(99)00058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lewis C., Blackman S.M., Nelson A., Oberdorfer E., Wells D., Dunitz J., et al. Diabetes-related mortality in adults with cystic fibrosis. role of genotype and sex. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:194–200. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0576OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sandouk Z., Khan F., Khare S., Moran A. Cystic fibrosis related diabetes (CFRD) prognosis. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2021;26 doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2021.100278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brennan A.L., Beynon J. Clinical updates in cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36:236–250. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1547319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brennan A.L., Gyi K.M., Wood D.M., Johnson J., Holliman R., Baines D.L., et al. Airway glucose concentrations and effect on growth of respiratory pathogens in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2007;6:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garnett J.P., Gray M.A., Tarran R., Brodlie M., Ward C., Baker E.H., et al. Elevated paracellular glucose flux across cystic fibrosis airway epithelial monolayers is an important factor for Pseudomonas aeruginosa growth. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Widger J., Ranganathan S., Robinson P.J. Progression of structural lung disease on CT scans in children with cystic fibrosis related diabetes. J Cyst Fibros. 2013;12:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fredj S.H., Messaoud T., Templin C. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator mutation spectrum in patients with cystic fibrosis in Tunisia. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2009;13:577–581. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2009.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petrova NV, Kashirskaya NY, Vasilyeva TA, Kondratyeva EI, Zhekaite EK, Voronkova AY, et al. Analysis of CFTR mutation spectrum in ethnic russian cystic fibrosis patients. Genes (Basel) 2020;11. 10.3390/genes11050554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Liu K., Xu W., Xiao M., Zhao X., Bian C., Zhang Q., et al. Characterization of clinical and genetic spectrum of Chinese patients with cystic fibrosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15:150. doi: 10.1186/s13023-020-01393-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Claustres M., Thèze C., et al. CFTR-France, a national relational patient database for sharing genetic and phenotypic data associated with rare CFTR variants. Hum Mutat. 2017;38:1297–1315. doi: 10.1002/humu.23276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruiz-Cabezas J.C., Barros F., Sobrino B., García G., Burgos R., Farhat C., et al. Mutational analysis of CFTR in the Ecuadorian population using next-generation sequencing. Gene. 2019;696:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Merjaneh L., Hasan S., Kasim N., Ode K.L. The role of modulators in cystic fibrosis related diabetes. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2022;27 doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2021.100286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Farrell PM, White TB, Ren CL, Hempstead SE, Accurso F, Derichs N, et al. Diagnosis of cystic fibrosis: consensus guidelines from the cystic fibrosis foundation. J Pediatr 2017;181s:S4-S15.e1. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Farrell P.M., Rosenstein B.J., White T.B., Accurso F.J., Castellani C., Cutting G.R., et al. Guidelines for diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in newborns through older adults: cystic fibrosis foundation consensus report. J Pediatr. 2008;153:S4–s14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grosse S.D., Boyle C.A., Botkin J.R., Comeau A.M., Kharrazi M., Rosenfeld M., et al. Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis: evaluation of benefits and risks and recommendations for state newborn screening programs. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004;53:1–36. No DOI available. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martiniano S.L., Wu R., Farrell P.M., Ren C.L., Sontag M.K., Elbert A., et al. Late diagnosis in the era of universal newborn screening negatively affects short- and long-term growth and health outcomes in infants with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 2023;262 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2023.113595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Farrell PM, White TB, Howenstine MS, Munck A, Parad RB, Rosenfeld M, et al. Diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in screened populations. J Pediatr 2017;181s:S33-S44.e2. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Wang S.S., O'Leary L.A., Fitzsimmons S.C., Khoury M.J. The impact of early cystic fibrosis diagnosis on pulmonary function in children. J Pediatr. 2002;141:804–810. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.129845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rubin R. Tackling the misconception that cystic fibrosis is a “white people's disease”. J Am Med Assoc. 2021;325:2330–2332. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.5086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hutchins K., Barr E., Bellcross C., Ali N., Hunt W.R. Evaluating differences in the disease experiences of minority adults with cystic fibrosis. J Patient Exp. 2022;9 doi: 10.1177/23743735221112629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McColley S.A., Martiniano S.L., Ren C.L., Sontag M.K., Rychlik K., Balmert L., et al. Disparities in first evaluation of infants with cystic fibrosis since implementation of newborn screening. J Cyst Fibros. 2023;22:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2022.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ladores S., Woods B.M., Pitts L.N., Belay D., Washington L., Bray L.A. The lived experience of african american persons with cystic fibrosis. Creat Nurs. 2023;29:374–382. doi: 10.1177/10784535231216461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Giusti R. Elevated IRT levels in African-American infants: implications for newborn screening in an ethnically diverse population. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2008;43:638–641. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Giusti R., Badgwell A., Iglesias A.D. New York State cystic fibrosis consortium: the first 2.5 years of experience with cystic fibrosis newborn screening in an ethnically diverse population. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e460–e467. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li W., Sun L., Corey M., Zou F., Lee S., Cojocaru A.L., et al. Understanding the population structure of North American patients with cystic fibrosis. Clin Genet. 2011;79:136–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01502.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pique L., Graham S., Pearl M., Kharrazi M., Schrijver I. Cystic fibrosis newborn screening programs: implications of the CFTR variant spectrum in nonwhite patients. Genet Med. 2017;19:36–44. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McGarry M.E., Ren C.L., Wu R., Farrell P.M., McColley S.A. Detection of disease-causing CFTR variants in state newborn screening programs. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2023;58:465–474. doi: 10.1002/ppul.26209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.TRIKAFTA prescribing information. https://www.trikaftahcp.com/ [accessed 20 November 2023].

- 75.SYMDEKO prescribing information. https://www.symdekohcp.com/ [accessed 20 November 2023].

- 76.ORKAMBI prescribing information. https://www.orkambi.com/ [accessed 20 November 2023].

- 77.KALYDECO prescribing information. https://www.kalydeco.com/ [accessed 20 November 2023].

- 78.Deignan J.L., Astbury C., Cutting G.R., Del Gaudio D., Gregg A.R., Grody W.W., et al. CFTR variant testing: a technical standard of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) Genet Med. 2020;22:1288–1295. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-0822-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Baker M.W., Atkins A.E., Cordovado S.K., Hendrix M., Earley M.C., Farrell P.M. Improving newborn screening for cystic fibrosis using next-generation sequencing technology: a technical feasibility study. Genet Med. 2016;18:231–238. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Furnier S.M., Durkin M.S., Baker M.W. Translating molecular technologies into routine newborn screening practice. Int J Neonatal Screen. 2020:6. doi: 10.3390/ijns6040080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sicko R.J., Stevens C.F., Hughes E.E., Leisner M., Ling H., Saavedra-Matiz C.A., et al. Validation of a custom next-generation sequencing assay for cystic fibrosis newborn screening. Int J Neonatal Screen. 2021:7. doi: 10.3390/ijns7040073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Currier R.J., Sciortino S., Liu R., Bishop T., Alikhani Koupaei R., Feuchtbaum L. Genomic sequencing in cystic fibrosis newborn screening: what works best, two-tier predefined CFTR mutation panels or second-tier CFTR panel followed by third-tier sequencing? Genet Med. 2017;19:1159–1163. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hendrix M.M., Foster S.L., Cordovado S.K. Newborn screening quality assurance program for CFTR mutation detection and gene sequencing to identify cystic fibrosis. J Inborn Errors Metab Screen. 2016:4. doi: 10.1177/2326409816661358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Paradies Y., Ben J., Denson N., Elias A., Priest N., Pieterse A., et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Quittner A.L., Goldbeck L., Abbott J., Duff A., Lambrecht P., Solé A., et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with cystic fibrosis and parent caregivers: results of The International Depression Epidemiological Study across nine countries. Thorax. 2014;69:1090–1097. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lord L., McKernon D., Grzeskowiak L., Kirsa S., Ilomaki J. Depression and anxiety prevalence in people with cystic fibrosis and their caregivers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2023;58:287–298. doi: 10.1007/s00127-022-02307-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Riekert K.A., Bartlett S.J., Boyle M.P., Krishnan J.A., Rand C.S. The association between depression, lung function, and health-related quality of life among adults with cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2007;132:231–237. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cronly J.A., Duff A.J., Riekert K.A., Fitzgerald A.P., Perry I.J., Lehane E.A., et al. Health-related quality of life in adolescents and adults with cystic fibrosis: physical and mental health predictors. Respir Care. 2019;64:406–415. doi: 10.4187/respcare.06356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Knudsen K.B., Pressler T., Mortensen L.H., Jarden M., Skov M., Quittner A.L., et al. Associations between adherence, depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life in young adults with cystic fibrosis. Springerplus. 2016;5:1216. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2862-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schechter M.S., Ostrenga J.S., Fink A.K., Barker D.H., Sawicki G.S., Quittner A.L. Decreased survival in cystic fibrosis patients with a positive screen for depression. J Cyst Fibros. 2021;20:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2020.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Roberts A.L., Gilman S.E., Breslau J., Breslau N., Koenen K.C. Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychol Med. 2011;41:71–83. doi: 10.1017/s0033291710000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Roberts B.K., Nofi C.P., Cornell E., Kapoor S., Harrison L., Sathya C. Trends and disparities in firearm deaths among children. Pediatrics. 2023:152. doi: 10.1542/peds.2023-061296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Houghton A., Jackson-Weaver O., Toraih E., Burley N., Byrne T., McGrew P., et al. Firearm homicide mortality is influenced by structural racism in US metropolitan areas. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;91:64–71. doi: 10.1097/ta.0000000000003167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gershon A., Hayward L., Donenberg G.R., Wilson H. Victimization and traumatic stress: Pathways to depressive symptoms among low-income African-American girls. Child Abuse Negl. 2018;86:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Acker J., Aghaee S., Mujahid M., Deardorff J., Kubo A. Structural racism and adolescent mental health disparities in Northern California. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2329825. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.29825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Heard-Garris N., Boyd R., Kan K., Perez-Cardona L., Heard N.J., Johnson T.J. Structuring poverty: how racism shapes child poverty and child and adolescent health. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21:S108–S116. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hankerson S.H., Moise N., Wilson D., Waller B.Y., Arnold K.T., Duarte C., et al. The intergenerational impact of structural racism and cumulative trauma on depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179:434–440. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.21101000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Anderson N.W., Eisenberg D., Zimmerman F.J. Structural racism and well-being among young people in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2023;65:1078–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2023.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. External Racial Justice Working Group: Final Recommendations. https://www.cff.org/news/2023-10/foundation-formalizes-final-recommendations-ERJWG [accessed 18 February 2024].

- 100.Institute NHGR. Talking glossary of genetic terms. https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary [accessed 20 November 2023].

- 101.Lopes-Pacheco M. CFTR modulators: the changing face of cystic fibrosis in the era of precision medicine. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1662. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fajac I., Sermet I. Therapeutic approaches for patients with cystic fibrosis not eligible for current CFTR modulators. Cells. 2021:10. doi: 10.3390/cells10102793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Meoli A., Fainardi V., Deolmi M., Chiopris G., Marinelli F., Caminiti C., et al. State of the art on approved cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) modulators and triple-combination therapy. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021:14. doi: 10.3390/ph14090928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kerem B.S., Zielenski J., Markiewicz D., Bozon D., Gazit E., Yahav J., et al. Identification of mutations in regions corresponding to the two putative nucleotide (ATP)-binding folds of the cystic fibrosis gene. PNAS. 1990;87:8447–8451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rauscher R., Bampi G.B., Guevara-Ferrer M., Santos L.A., Joshi D., Mark D., et al. Positive epistasis between disease-causing missense mutations and silent polymorphism with effect on mRNA translation velocity. PNAS. 2021:118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010612118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.McGinniss M.J., Chen C., Redman J.B., Buller A., Quan F., Peng M., et al. Extensive sequencing of the CFTR gene: lessons learned from the first 157 patient samples. Hum Genet. 2005;118:331–338. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-0065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.