Abstract

Spores of Bacillus subtilis with a mutation in spoVF cannot synthesize dipicolinic acid (DPA) and are too unstable to be purified and studied in detail. However, the spores of a strain lacking the three major germinant receptors (termed Δger3), as well as spoVF, can be isolated, although they spontaneously germinate much more readily than Δger3 spores. The Δger3 spoVF spores lack DPA and have higher levels of core water than Δger3 spores, although sporulation with DPA restores close to normal levels of DPA and core water to Δger3 spoVF spores. The DPA-less spores have normal cortical and coat layers, as observed with an electron microscope, but their core region appears to be more hydrated than that of spores with DPA. The Δger3 spoVF spores also contain minimal levels of the processed active form (termed P41) of the germination protease, GPR, a finding consistent with the known requirement for DPA and dehydration for GPR autoprocessing. However, any P41 formed in Δger3 spoVF spores may be at least transiently active on one of this protease's small acid-soluble spore protein (SASP) substrates, SASP-γ. Analysis of the resistance of wild-type, Δger3, and Δger3 spoVF spores to various agents led to the following conclusions: (i) DPA and core water content play no role in spore resistance to dry heat, dessication, or glutaraldehyde; (ii) an elevated core water content is associated with decreased spore resistance to wet heat, hydrogen peroxide, formaldehyde, and the iodine-based disinfectant Betadine; (iii) the absence of DPA increases spore resistance to UV radiation; and (iv) wild-type spores are more resistant than Δger3 spores to Betadine and glutaraldehyde. These results are discussed in view of current models of spore resistance and spore germination.

Spores of Bacillus and Clostridium species normally contain ≥10% of their dry weight as pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid (dipicolinic acid [DPA]) (21, 22, 39). This compound is synthesized late in sporulation in the mother cell compartment of the sporulating cell but accumulates only in the developing forespore (6, 36). The great majority of the spore's DPA is in the spore core, where it is most likely chelated with divalent cations, predominantly Ca2+, although there are also significant amounts of Mg2+ and Mn2+, with smaller amounts of other divalent cations (21, 22, 37, 39). In the first minutes of spore germination the DPA is excreted, along with the associated divalent cations (36, 37).

Since DPA is found only in dormant spores of Bacillus and Clostridium species and since these spores differ in a number of properties from vegetative cells, in particular in their dormancy and heat resistance, it is not surprising that DPA and divalent cations have been suggested to be involved in some of the spore's unique properties. There is some evidence in support of this suggestion, since mutants whose spores do not accumulate DPA have been isolated in several Bacillus species, and often these DPA-less spores are heat sensitive (1, 4, 25, 42, 43). Unfortunately, for some of these latter mutants the specific genetic lesion(s) giving rise to the DPA-less spore phenotype is not known. DPA is synthesized from an intermediate in the lysine pathway, and the enzyme that catalyzes DPA synthesis is termed DPA synthetase (6). In B. subtilis this enzyme is encoded by the two cistrons of the spoVF operon, which is expressed only in the mother cell compartment of the sporulating cell, the site of DPA synthesis. Mutants of B. subtilis likely to be in or known to be in spoVF result in lack of DPA synthesis during sporulation, and the spores produced never attain the wet heat resistance of wild-type spores (1, 4, 6, 25). Unfortunately, it has been impossible to isolate and purify free spores from these spoVF mutants of B. subtilis, since the spores are extremely unstable and germinate and lyse during purification (B. Setlow and P. Setlow, unpublished results). This observation suggests that, at least in B. subtilis, DPA is needed in some fashion to maintain spore dormancy (7, 15), although the specific mechanism whereby this is achieved is not clear.

In addition to its possible roles in spore dormancy and resistance, DPA complexed with a divalent cation, usually Ca2+, is an effective germinant of spores of almost all Bacillus and Clostridium species (15). These and other data have led to the suggestion that DPA may activate, possibly allosterically, some enzyme involved in spore germination (15). To date, this spore enzyme involved in spore germination has not been identified. However, DPA does allosterically modulate the activity of the germination protease (GPR) that initiates the degradation of the spore's depot of small, acid-soluble spore proteins (SASPs) during spore germination (14, 32). GPR is synthesized as an inactive zymogen (termed P46) during sporulation, and P46 autoprocesses to a smaller active form (termed P41) approximately 2 h later in sporulation. This conversion of P46 to P41 is stimulated allosterically by DPA, and only the physiological DPA isomer is effective (14, 32). The activation of this zymogen is also stimulated by the acidification and dehydration of the spore core, and together these conditions ensure that P41 is generated only late in sporulation, when the conditions in the spore core preclude enzyme action (14, 32). As a result, GPR's SASP substrates, which are synthesized in parallel with P46, are stable in the developing and dormant spore. This is important for spore survival, as some major SASP (the α/β-type) are essential for the protection of spore DNA from a variety of types of damage, while degradation of both the α/β-type SASP and the other major SASP (γ) provides amino acids for protein synthesis early in spore germination (38, 39, 40).

We recently described a mutant strain of B. subtilis that lacks the three operons encoding the proteins responsible for sensing and triggering spore germination in response to nutrient germinants (24). This strain sporulates normally but its spores germinate extremely poorly in response to nutrient germinants; however, the spores germinate normally in response to a mixture of Ca2+ and DPA (24). These observations suggested that introduction of a spoVF mutation into this strain lacking nutrient receptors for spore germination might result in the production of DPA-less spores that were stable enough to be isolated and purified, yet which could be recovered by spore germination in Ca2+ and DPA. This was indeed the case, and in this study we describe the properties of these stable DPA-less spores.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains used and production and purification of spores.

The B. subtilis strains used in this work are all derivatives of strain 168 and are derived from PS832, a trp+ revertant of 168. The strains are: PS533, containing plasmid pUB110 carrying a gene for kanamycin resistance (Kmr); FB72 ΔgerA::spc ΔgerB::cat ΔgerK::erm (24) (this strain will be referred to here as Δger3); and FB108 ΔgerA::spc ΔgerB::cat ΔgerK::erm ΔspoVF::tet (this strain will be termed here Δger3 spoVF [see below]). Unless otherwise noted, the spores of these various strains were prepared on 2×SG medium (23) agar plates without or with DPA (100 μg/ml). The plates were spread with 0.1 ml of a suspension (∼105 cells/ml) of growing cells of the appropriate strain and incubated at 37°C for ∼48 h. Spores and sporulating cells were scraped from the plates, and the spores were purified as described previously (20); all spore preparations used in this work were free (>95%) of growing or sporulating cells or germinated spores and were initially stored in water at 12°C, the temperature of our cold room. Spores stored in this manner were stable for several weeks but are even more stable if stored at 4°C.

Construction of the ΔspoVF strain.

The ΔspoVF::tet plasmid pFE229 was derived from plasmid pECE98 (Bacillus Genetic Stock Center) as follows. The 3′ end of the spoVF operon, spanning nucleotides (nt) 932 to 1278 relative to the first codon of the spoVFA translation start site (defined as +1), was amplified by PCR from PS832 chromosomal DNA with primers ΔspoVFC5 and ΔspoVFC3 (primer sequences will be provided on request) and the PCR fragment cloned in the TA vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen), yielding plasmid pFE226. The insert was excised from pFE226 with HindIII (site present in primer ΔspoVFC5) and EcoRI (site present in primer ΔspoVFC3) and cloned between the HindIII and EcoRI sites in pECE98, yielding plasmid pFE228. The 5′ end of the spoVF operon spanning nt 21 to 386 relative to the spoVFA translation start site was PCR amplified as described above, but with primers ΔspoVFN5 and ΔspoVFN3, and cloned into pCR2.1, yielding plasmid pFE227. The insert in plasmid pFE227 was excised with BamHI and PstI (sites in primers ΔspoVFN5 and ΔspoVFN3, respectively) and cloned between the BamHI and PstI sites in plasmid pFE228, yielding the ΔspoVF::tet plasmid pFE229. The ΔspoVF::tet derivative of strain FB72 was constructed by transforming (5) this strain with plasmid pFE229 and using Southern blot analysis to identify tetracycline-resistant transformants that had arisen by a double-crossover event. One of these transformants was called FB108.

Analyses of spore resistance, spore proteins, and spores.

Resistance of spores to treatment with wet and dry heat, dessication, hydrogen peroxide, glutaraldehyde, formaldehyde, UV radiation, and the iodine-based disinfectant Betadine (Purdue-Frederick Company, Norwalk, Conn.) was tested as described previously (17, 23, 34, 35, 41). However, because Δger3 spores do not germinate in response to nutrient germinants, after spore treatment the spores of all strains were germinated in 60 mM CaDPA as described elsewhere (24) prior to dilution and plating on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium agar plates (41) to determine the number of survivors.

For analysis of GPR, 15 to 25 mg (dry weight) of spores of various strains was dry ruptured with 100 mg of glass beads in 8×1-min bursts in a dental amalgamator (23). The resultant dry powder was extracted with 0.5 ml of cold 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–5 mM EDTA–0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and, after 30 min on ice, the mix was centrifuged in a microcentrifuge. After determination of the protein concentration in the supernatant fluid by the Lowry method (18), aliquots were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 10% polyacrylamide gels, the proteins were transferred to polyvinylidine difluoride paper (Immobilon), and GPR was detected with anti-GPR serum as described earlier (27, 31, 32).

For analysis of SASP, 7 to 12 mg of dry spores or the dry pellet from 10 ml of sporulating cells was disrupted as described above and extracted twice with 0.5 ml of cold 3% acetic acid, and the supernatant fluids were combined, dialyzed overnight in Spectrapor 3 tubing (molecular mass cutoff, 3,500 kDa) against cold 1% acetic acid, and lyophilized (23). The dry residue was dissolved in a small volume of 8 M urea, aliquots were subjected to PAGE at low pH, and the gels were stained with Coomassie blue (23).

DPA was analyzed after extraction of spores with boiling water as described elsewhere (23, 29). For determination of spore core wet densities, spore coats were removed by extraction with SDS, dithiothreitol, and urea, and the decoated spores were centrifuged in Nycodenz or metrizoic acid density gradients as described earlier (16, 28). For the determination of spore germination, spores were diluted in water, and appropriate dilutions were spread onto LB medium plates; colonies were counted after incubation for 24 h at 37°C. Spores were prepared for electron microscopy as described previously (19).

RESULTS

Preparation and characterization of Δger3 spoVF spores.

Initial analyses showed that the Δger3 spoVF strain sporulated to a similar degree as the Δger3 parent. However, liquid cultures of spores produced by the Δger3 spoVF strain had a higher percentage of germinated spores than the Δger3 parent. This was much less evident with spore preparations made on plates, and the spores prepared on plates from both the Δger3 spoVF and Δger3 strains were also easy to purify and readily gave clean spore preparations containing >95% spores which appeared bright in the phase-contrast microscope. Consequently, Δger3 spoVF and Δger3 spores were prepared on plates unless noted otherwise. Wild-type (PS533) and Δger3 spores had similar levels of DPA, while the Δger3 spoVF spores had <5% of this level (Table 1). Sporulation of the Δger3 strains with DPA (100 μg/ml) had no effect on the level of DPA in the Δger3 spores, but raised the DPA level in the Δger3 spoVF spores to 65% of that in Δger3 spores (Table 1 and data not shown).

TABLE 1.

DPA, core water content, and colony formation of various sporesa

| Strain | Spore properties

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPA content (μg/OD600) | Core wet density (g/ml) | Germination

|

||

| Colonies formed/OD600 in 24 hb | Phase dark spores in 36 h (%)c | |||

| PS533 (wild type) | 14.8 | 1.365 | 6.5 × 107 | NDd |

| FB72 | 15.5 | 1.370 | 4 × 104 | <0.5 |

| FB108 | <0.7 | 1.297 | 1.3 × 107 | 40 |

| FB108 (sporulated with DPA) | 9.7 | 1.345 | 4.5 × 105 | ND |

Spores were prepared, and the DPA content, core wet densities, and colonies formed/OD600 on LB medium plates were determined as described in Materials and Methods.

Values are averages of data from two determinations on one spore preparation. These values differed by <2-fold between three different spore preparations. After germination with CaDPA prior to spreading onto LB medium plates, the values for all four strains were 108 colonies formed/OD600 in 24 h.

Spores (107/ml) were incubated at 37°C in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) for 36 h, and then 120 to 200 spores were examined in the phase-contrast microscope.

ND, not determined.

While the DPA-less spores did appear bright in the phase-contrast microscope, suggesting at least partial core dehydration, their core wet density was significantly lower than that of the wild-type and Δger3 spores; however, sporulation with DPA raised the core wet density of Δger3 spoVF spores significantly (Table 1). These differences in core wet densities indicate that the core of the Δger3 spoVF spores prepared without DPA contains significantly more water per gram (dry weight) than the core of the Δger3 spores. However, the core wet density of Δger3 spoVF spores is still significantly greater than that of germinated spores (1.228 g/ml) (26).

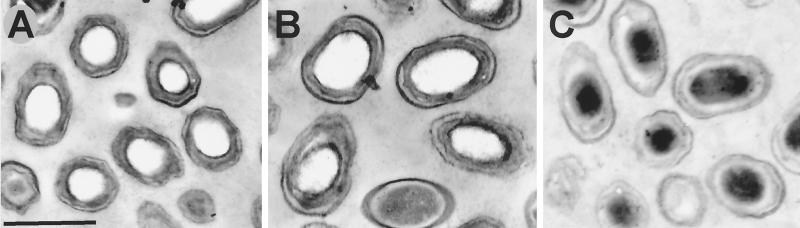

Examination of spores of the Δger3 and Δger3 spoVF strains by electron microscopy indicated that spores of both strains had normal-looking coats and cortex layers (Fig. 1). The core of Δger3 spores showed no evidence of significant structure and appeared white, as is typical of the dehydrated wild-type spore core; in contrast, the core region of Δger3 spoVF spores showed the dark, often punctate staining pattern associated with the presence of ribosomes and a significant amount of water in the spore core (10). This is consistent with the higher level of core hydration in Δger3 spoVF spores noted above, and these results are similar to those obtained previously in one study of spores of a B. subtilis spoVF mutant (1). However, an earlier electron microscopic analysis of sporulating spoVF cells suggested that the cortex of the spores produced was incompletely developed (4). Perhaps this was due to some early germination-like changes in the spores within these spoVF sporangia.

FIG. 1.

Thin-section electron micrographs of spores with or without DPA. Spores were prepared for electron microscopy as described in Materials and Methods. The spores shown are PS832 (wild-type) (A), FB72 (Δger3) (B), and FB108 (Δger3 spoVF) (C). The bar in panel A denotes 1 μm, and the other two panels are at the same magnification as panel A.

Previous work has shown that Δger3 spores exhibit very low levels of colony formation when plated on rich medium plates because of the infrequent, albeit spontaneous, germination of these spores (24). This was also observed here, as three different preparations of Δger3 spores gave <0.1% of the colonies/optical density at 600 nm (OD600), as did the wild-type spores (Table 1). However, these spores can be fully recovered by germination with CaDPA prior to plating on rich medium plates (24). While the colony-forming ability of Δger3 spoVF spores on rich medium plates was not as high as that of wild-type spores, it was 100-fold higher than that of Δger3 spores; as expected, the Δger3 spoVF spores were also fully recovered by prior germination with CaDPA (Table 1). Restoration of significant DPA levels to Δger3 spoVF spores suppressed much of their spontaneous colony-forming ability on rich medium plates, but not their colony-forming ability after CaDPA treatment (Table 1). As found previously (24), the Δger3 spores also did not undergo germination in dilute buffer, when spore germination was measured by the conversion of a bright spore to a dark one as seen in a phase-contrast microscope (Table 1). However, a large fraction of the Δger3 spoVF spores underwent spore germination when dilute spores were incubated at 37°C in dilute buffer (Table 1).

Levels of GPR forms and SASP in spores.

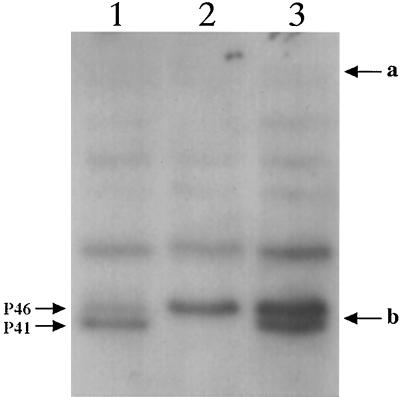

The lack of DPA and the elevated core hydration in Δger3 spoVF spores suggested that the SASP-specific protease, GPR, might be poorly processed in these spores, since both DPA accumulation and core dehydration stimulate conversion of P46 to P41 (14, 32). Analysis of the extent of GPR processing in various spores revealed that ∼75% of the P46 was converted to P41 in Δger3 spores (Fig. 2, lane 1), a value similar to that found previously in wild-type spores (27, 32). However, in Δger3 spoVF spores ≥90% of the GPR was present as P46 (Fig. 2, lane 2), while in the spores of the latter strain prepared with DPA about 40% of the GPR had been processed to P41 (Fig. 2, lane 3).

FIG. 2.

Levels of the P46 and P41 forms of GPR in spores. Soluble proteins from spores of various strains were isolated and 10 μg of soluble protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using anti-GPR antiserum as described in Materials and Methods. The samples run on the various lanes are as follows: lane 1, Δger3 spores; lane 2, Δger3 spoVF spores; and lane 3, Δger3 spoVF spores sporulated with DPA. The migration positions of the P46 and P41 forms of GPR are given on the left of the figure. The migration positions of molecular mass markers of 84 and 41 kDa are denoted by arrows a and b, respectively. The bands above P46 and P41 reacted nonspecifically with the antiserum used in this experiment.

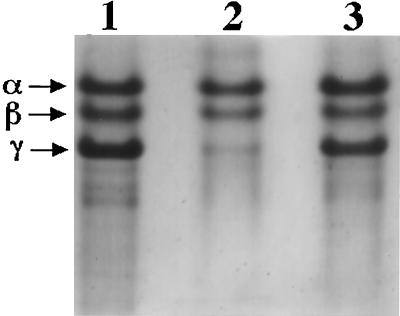

Although very little P46 is processed to P41 in Δger3 spoVF spores, any P41 produced in these spores might be expected to be able to act on its SASP substrates because of the greater spore core hydration at the time of P41 generation (27, 39). This P41 action would most likely be on SASP-γ since this protein is not protected from proteolysis by binding to some spore macromolecule, unlike SASP-α and -β which are bound to spore DNA (39, 40). Indeed, previous work has shown that increased spore core hydration during the period of P41 production does lead to significantly reduced levels of SASP-γ in spores (27). Consequently, it was not surprising to find that SASP-γ was almost completely absent in Δger3 spoVF spores, while levels of SASP-α and -β were similar to those in Δger3 spores (Fig. 3, compare lanes 1 and 2, and note that more protein was run on lane 1). As expected, Δger3 spoVF spores prepared with DPA did contain a significant level of SASP-γ, although this level was a bit lower than in Δger3 spores (Fig. 3, lanes 1 and 3).

FIG. 3.

Levels of SASP-α, -β, and -γ in spores. SASPs were extracted from purified spores of various strains, dialyzed, and lyophilized; aliquots were subjected to PAGE at low pH, and the gels were stained as described in Materials and Methods. The samples run on the various lanes (and the dry weight of the spores in the samples run) were as follows: lane 1, Δger3 spores (1 mg); lane 2, Δger3 spoVF (0.6 mg); and lane 3, Δger3 spoVF spores prepared with DPA (1 mg).

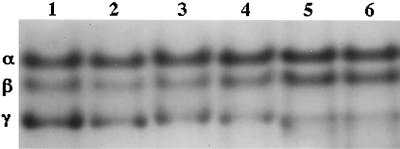

Since the spores analyzed for SASP levels as described above remained for ∼2 weeks at 12°C during preparation, it was of obvious interest to determine if developing spores of the Δger3 spoVF strain had never contained SASP-γ or had accumulated and then degraded this protein and, if the latter was the case, when the protein was degraded. Consequently, we analyzed SASP levels in sporulating cells during incubation at 37°C or subsequent incubation at 12°C (Fig. 4). Levels of SASP-α and -β were relatively constant once these proteins had accumulated in developing Δger3 spoVF spores, and SASP-γ was also present at high levels shortly after completion of SASP synthesis (Fig. 4, lane 1). However, levels of SASP-γ then began to decrease, and ∼9 h later levels of this protein had fallen significantly and possibly fell even more after the culture had been harvested, washed with cold water, and incubated at 12°C. These data indicate that relatively normal levels of SASP-γ are accumulated by developing Δger3 spoVF spores but that the SASP-γ then disappears, presumably by degradation as sporulation and spore incubation proceeds.

FIG. 4.

Levels of SASP-α, -β, and -γ in sporulating cultures. Samples (10 ml) of strain FB108 (Δger3 spoVF) sporulating in liquid 2×SG medium at 37°C were harvested, frozen, and lyophilized. After 36 h of growth, the remaining culture was harvested, washed several times with cold water, and resuspended in cold water. Again, aliquots equal to 10 ml of original culture were harvested, frozen, and lyophilized. Dry samples were disrupted; SASP was extracted; extracts were dialyzed, lyophilized, and redissolved; equal aliquots were subjected to PAGE at low pH, and the gel stained as described in Materials and Methods. The times (t) (in hours) in sporulation that the samples run in the various lanes were harvested were as follows: lane 1, t4; lane 2, t6; lane 3, t7.5; lane 4, t13.5; lane 5, t28; and lane 6, t160. Note that the last sample was incubated at 12°C for ∼145 h. The migration positions of SASP-α, -β, and -γ are given on the left of the figure.

Resistance of Δger3 and Δger3 spoVF spores.

The normal levels of SASP-α and -β in Δger3 spoVF spores suggested that the protection of spore DNA from damage by these proteins should be normal in Δger3 spoVF spores, and thus some aspects of spore resistance should be normal in these spores (39, 40). Indeed, previous work has shown that the spores formed by a B. subtilis strain with a mutation that is probably in spoVF are fully resistant to some chemical agents, including octanol and chloroform (1). However, these same spores were sensitive to a number of other chemicals and were also sensitive to wet heat (1). Given the known relationships between spore resistance and spore core hydration and mineral levels (11, 20, 40), it was of obvious interest to test the resistance of Δger3 and Δger3 spoVF spores to a variety of agents. As seen previously and as expected based on the elevated level of core water in Δger3 spores (1, 11, 28), the Δger3 spoVF spores were much less resistant to wet heat than were Δger3 spores, while the latter spores had identical wet heat resistance to wild-type spores (Fig. 5A and data not shown). Spores of the Δger3 spoVF strain prepared with DPA exhibited an intermediate level of wet heat resistance (Fig. 5A). Although the Δger3 spoVF spores were significantly more sensitive to wet heat than were the wild-type spores, they were much more resistant than germinated spores or growing cells (<0.01% survival after 5 min at 70°C; data not shown). In contrast to the differences observed in the wet heat resistance of Δger3 spoVF and Δger3 spores, both of these spores exhibited identical resistance to dry heat and were fully resistant to dessication (Table 2 and data not shown). The resistance of these spores to dry heat and dessication was identical to that of wild-type spores (data not shown) and much greater than that of growing cells (9, 35).

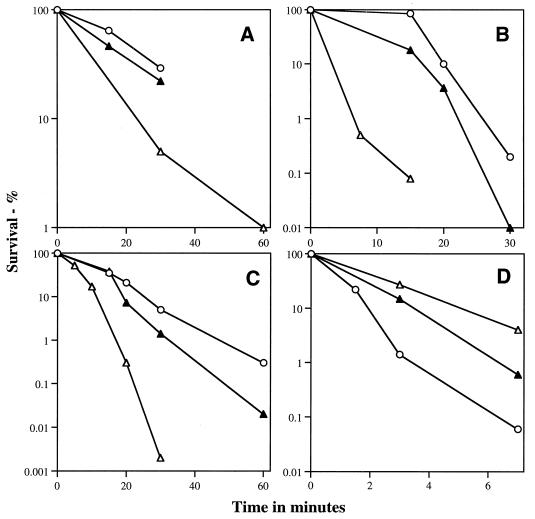

FIG. 5.

Resistance of spores with or without DPA to heat (A), hydrogen peroxide (B), formaldehyde (C), or UV radiation (D). Spores were either heated at 85°C (○ and ▴) or 70°C (▵) (A), incubated with 0.7 M hydrogen peroxide at room temperature (B), incubated with 0.3 M formaldehyde at room temperature (C), or UV irradiated at 150 J/m2 · min (D), and the survival was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Symbols: ○, Δger3 spores; ▵, Δger3 spoVF spores; ▴, Δger3 spoVF spores prepared with DPA. All experiments were repeated at least twice with essentially identical results.

TABLE 2.

Spore resistance to dry heat and dessicationa

| Treatment | % Survival

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| FB72 (Δger3) | FB108 (Δger3 spoVF) sporulated without DPA | FB108 (Δger3 spoVF) sporulated with DPA | |

| Dessicationb | 96 | 92 | 98 |

| Dry heat (120°C) for 30 min | 26 | 23 | 24 |

Spores were produced and analyzed for dessication and dry-heat resistance as described in Materials and Methods.

Spores were freeze-dried once, and the viability was measured after rehydration.

Analysis of resistance to hydrogen peroxide and formaldehyde gave results which were qualitatively similar to those with wet heat. The Δger3 and wild-type spores exhibited identical resistance to formaldehyde and hydrogen peroxide (data not shown), while Δger3 spoVF spores were more sensitive and Δger3 spoVF spores prepared with DPA had intermediate levels of resistance (Fig. 5B and C). The UV resistance of Δger3 spores was also identical to that of wild-type spores (data not shown), but Δger3 spoVF spores were more UV resistant than were Δger3 spores, while Δger3 spoVF spores prepared with DPA had an intermediate level of resistance (Fig. 5D).

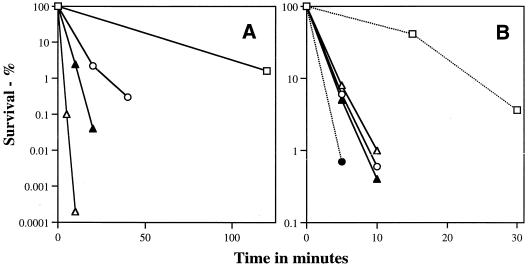

In contrast to wet heat, dry heat, UV, hydrogen peroxide, and formaldehyde, which had essentially identical efficiencies of killing of wild-type and Δger3 spores, Δger3 spores were significantly more sensitive to both the iodine-based disinfectant Betadine and to glutaraldehyde than were the wild-type spores (Fig. 6). The Δger3 spoVF spores exhibited decreased resistance to Betadine compared to that of Δger3 spores, with Δger3 spoVF spores prepared with DPA exhibiting intermediate resistance (Fig. 6A). However, Δger3 and Δger3 spoVF spores (with or without DPA) had identical resistance to glutaraldehyde (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Betadine and glutaraldehyde resistance of spores with or without DPA. Spores were incubated either with 85% Betadine at 37°C (A) or with 1.8% glutaraldehyde (□ and ●) or 0.5% glutaraldehyde (○, ▵, and ▴) at room temperature (B), and the survival was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Symbols: □, PS533 (wild-type) spores; ○ and ●, Δger3 spores; ▵, Δger3 spoVF spores; ▴, Δger3 spoVF spores prepared with DPA. All experiments were repeated at least twice with essentially identical results.

DISCUSSION

Although DPA was discovered in spores of Bacillus species over 40 years ago, its specific function in spores has remained somewhat obscure. Correlations have been noted between spore wet heat resistance and DPA content (11, 22), but there are a number of observations indicating that DPA need not be essential for spore heat resistance. Thus, DPA plus associated divalent cations can be removed from the mature spores of several species by appropriate treatments, yielding spores with <1% of untreated spore DPA levels; these DPA-less spores retain a high level of wet heat resistance which is often similar to that of untreated spores (2, 11). Strikingly, these DPA-less spores of Bacillus stearothermophilus appeared to have more highly hydrated core regions than untreated spores yet still retained high wet heat resistance. The reasons for the wet heat resistance of these DPA-less and relatively demineralized spores are not clear, but these data indicate that DPA is not necessarily essential for spore wet heat resistance. However, it is possible that DPA accumulation during sporulation is required for the attainment of some state that is essential for full spore wet heat resistance. In support of this possibility, several studies, including the current one, have found that in B. subtilis the loss of the ability to synthesize DPA results in the production of wet heat-sensitive spores which exhibit increased core dehydration (1, 4, 6, 8). However, it is not clear if this effect is due only to a change in spore core hydration or also to the reduction in core mineralization which accompanies the loss of DPA from spores (12). Since spore core mineralization also plays a role in wet heat resistance (11, 20), it is certainly possible that changes in both core hydration and mineral levels contribute to the loss of wet heat resistance of DPA-less spores.

Strains of Bacillus cereus and Bacillus megaterium with uncharacterized mutations that abolish DPA accumulation in spores also produce heat-sensitive spores, and in at least one case these spores appeared to have increased core hydration (42, 43). While the existence of these latter mutants would seem to support a role for DPA in spore heat resistance, there are several reports (11, 12) that the heat-sensitive DPA-less spores of B. cereus can be further mutated to give a strain that produces DPA-less but heat-resistant spores. Unfortunately, the genes responsible for these phenotypes are not known, and the heat-resistant phenotype of the DPA-less spores was extremely unstable (12). There is also an old report that heat-resistant DPA-less spores of B. subtilis had been isolated (42); unfortunately, there are almost no details available about this strain and the mutations which gave rise to this phenotype. Since addition of only very small amounts of DPA to spoVF cultures can result in production of at least some heat-resistant spores (1), possibly the mutants producing DPA-less, heat-resistant spores are actually oligosporogenous, and the heat-resistant spores arise from the acquisition of sufficient DPA by a fraction of spores, either through synthesis in the surrounding mother cell or from the culture medium (8). If only a fraction of the spore population in a culture acquired only a small amount of DPA, then analysis might well not detect significant DPA in the population as a whole.

The precise role of DPA in spores is still not clear; however, in B. subtilis specifically blocking DPA synthesis results in DPA-less spores with significantly less wet heat resistance than wild-type spores. The lack of DPA in these B. subtilis spores is accompanied by increased core hydration, and there are abundant data that this increase in core hydration should reduce spore wet heat resistance (11, 27) and, as shown here, it does. However, the DPA-less spores of B. subtilis are still significantly more wet heat resistant (and less hydrated) than are growing cells or germinated spores of this organism (26, 27, 40).

In addition to a role for DPA in spore wet heat resistance, two other roles have been proposed. One is to stabilize the dormant spore such that it does not germinate spontaneously (7, 16, 40). This appears to be the case for the B. subtilis spores studied in this work, since the Δger3 spoVF spores germinate spontaneously much more readily than the Δger3 spores. Unfortunately, it is not clear at present either what is involved in “spontaneous” spore germination or how spore DPA could suppress this event. Surprisingly, it has also been reported that some DPA-less spores of B. cereus, B. megaterium, and B. subtilis germinate extremely poorly (12, 42). However, the mutation or mutations giving rise to the DPA-less spores of these strains are not known, and it is certainly possible that, in addition to a mutation blocking DPA synthesis or uptake, these strains have an additional mutation(s) suppressing spore germination, thus allowing the DPA-less spores of these strains to be isolated.

A second specific role for DPA is in allosterically stimulating the processing of GPR from P46 to P41 such that this processing only takes place very late in spore core maturation, when the core dehydrates; this dehydration also stimulates conversion of P46 to P41 (14, 32). The coupling of DPA accumulation and core dehydration with generation of active GPR ensures that minimal if any SASP degradation takes place in sporulation, maximizing the levels of these proteins, in particular the α/β-type SASPs which are essential for full spore DNA resistance and long-term spore survival (15, 40). This role of DPA and core dehydration in regulation of P46 processing is certainly consistent with the results presented here, since very little P46 is processed to P41 in spores of the Δger3 spoVF strain, and this processing is largely restored if these spores are prepared with DPA.

One result which seems to be at odds with the significantly reduced P41 generated in Δger3 spoVF spores is the degradation of the SASP-γ that is accumulated midway in sporulation. Previous work has shown that SASP are normally not degraded during sporulation (38), although this will take place, primarily with SASP-γ, if P41 is activated too early or in too high amounts or under conditions of too little core dehydration (12, 27, 32). Although very little P41 appears to be present in Δger3 spoVF spores, there could easily be ∼5% of wild-type spore levels, and this would be more than enough to catalyze significant SASP-γ breakdown until sufficient core dehydration precludes further enzyme action. Alternatively, the degradation of SASP-γ in Δger3 spoVF spores might be catalyzed by proteases other than GPR, which slowly act on SASP-γ in the more hydrated core of these spores. One other possibility that deserves mention is that SASP-γ degradation may actually continue in the mature dormant spore. It is thought that enzyme action in the spore core is precluded by the low level of water in this region of the spore (39). However, the increased hydration of the Δger3 spoVF spore core may allow some low level of enzyme action. The fact that SASP-γ levels fall only somewhat slowly upon extended incubation of sporulating cells is suggestive of this possibility, but further detailed work on this and other enzyme-substrate pairs (39) in the core of DPA-less spores is needed.

As noted above, the increased hydration and the decreased mineralization of the core of Δger3 spoVF spores is consistent with their decreased resistance to wet heat (11). The decreased resistance of Δger3 spoVF spores to formaldehyde was also expected, since this agent kills spores by causing DNA damage in the spore core (17), and the rate of accumulation of this damage would be expected to be more rapid in a more hydrated spore core. Similarly, there are previous data indicating that within a species increasing core hydration is correlated with decreasing spore resistance to hydrogen peroxide (28), and this is consistent with the decreased hydrogen peroxide resistance of Δger3 spoVF spores. However, the precise target for hydrogen peroxide in spores is not known. It is also possible that the decreased mineralization of DPA-less spores plays some role in their decreased resistance to formaldehyde and hydrogen peroxide, but there are no data available on this point.

The normal resistance of Δger3 spoVF spores to dry heat and dessication was also not unexpected, since these resistance properties are independent of core water content in B. subtilis spores and depend largely on the presence of α/β-type SASP (9, 35), and levels of these DNA protective proteins are normal in Δger3 spoVF spores. The presence of normal levels of α/β-type SASP in Δger3 spoVF spores also explains the UV resistance of these spores, since α/β-type SASPs are the major determinant of spore UV resistance (38, 40). The specific level of core dehydration plays very little if any role in spore resistance to UV radiation at 254 nm as shown previously (28), while DPA actually decreases spore UV resistance by acting as a photosensitizer (33); this latter point explains the increased UV resistance of Δger3 spoVF spores compared to that of Δger3 spores.

All of the agents discussed above had identical efficiencies in killing wild-type and Δger3 spores. In contrast, glutaraldehyde and the iodine-based disinfectant, Betadine, were much more effective in killing Δger3 spores than wild-type spores. Both of these agents have been shown to kill spores in part by damaging the spore germination apparatus (3, 30, 41). The increased sensitivity of the Δger3 spores to these agents may thus be due to the fact that CaDPA-triggered spore germination requires at least one protein which is in the spore's exterior layers (24) and thus is extremely sensitive to exogenous chemical agents (3, 24, 41). In contrast, wild-type spores appear to have at least one other pathway for triggering spore germination that does not require this sensitive protein (24). In support of this reasoning, the presence of DPA and various levels of core dehydration had no effect on spore resistance to glutaraldehyde, which is thought to block a very early step in spore germination. However, spore Betadine resistance was increased by DPA and increased core dehydration, suggesting that Betadine may also kill spores by inactivating some more interior protein(s).

While the analysis of the properties of the Δger3 spoVF spores has given us some insight into the role of DPA and core hydration in various aspects of spore resistance and biochemistry, the isolation of moderately stable spores of the Δger3 spoVF strain of B. subtilis also may prove useful in opening up other avenues of research. For example, DPA-less heat-sensitive spores of B. cereus have been used as a parent to isolate DPA-less heat-resistant spores (12). However, because of the relative paucity of genetics and techniques for genetic manipulation in B. cereus, the nature of the second mutation or mutations restoring heat resistance to these spores is not known. However, given the ease of genetic manipulation with B. subtilis, if the Δger3 spoVF strain can generate DPA-less but now heat-resistant spores, the analysis of the mutation giving this new phenotype should be straightforward and may give us much new insight into the mechanism of spore resistance to wet heat. This work is currently in progress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for a suggestion from one of the reviewers of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM19698 [P.S.] and GM39898 [A.D.]) and the Army Research Office.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balassa G, Milhaud P, Raulet E, Silva M T, Sousa J C F. A Bacillus subtilis mutant requiring dipicolinic acid for the development of heat-resistant spores. J Gen Microbiol. 1979;110:365–379. doi: 10.1099/00221287-110-2-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaman T C, Pankratz H S, Gerhardt P. Heat shock affects permeability and resistance of Bacillus stearothermophilus spores. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:2515–2520. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.10.2515-2520.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloomfield S F, Arthur M. Mechanisms of inactivation and resistance of spores to chemical biocides. J Appl Bacteriol. 1994;76:91S–104S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1994.tb04361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coote J G. Characterization of oligosporogenous mutants and comparison of their phenotypes with those of asporogenous mutants. J Gen Microbiol. 1972;71:1–15. doi: 10.1099/00221287-71-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cutting S M, Vander Horn P B. Genetic analysis. In: Harwood C R, Cutting S M, editors. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 1990. pp. 27–74. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniel R A, Errington J. Cloning, DNA sequence, functional analysis and transcriptional regulation of the genes encoding dipicolinic acid synthetase required for sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:468–483. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Errington J. Bacillus subtilis sporulation: regulation of gene expression and control of morphogenesis. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:1–33. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.1-33.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Errington J, Cutting S M, Mandelstam J. Branched pattern of regulatory interactions between late sporulation genes in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:796–801. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.2.796-801.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fairhead H, Setlow B, Waites W M, Setlow P. Small, acid-soluble proteins bound to DNA protect Bacillus subtilis spores from killing by freeze-drying. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2647–2649. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2647-2649.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitz-James P, Young E. Morphology of sporulation. In: Gould G W, Hurst A, editors. The bacterial spore. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 39–72. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerhardt P, Marquis R E. Spore thermoresistance mechanisms. In: Smith I, Slepecky R A, Setlow P, editors. Regulation of prokaryotic development. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanson R S, Curry M V, Garner J V, Halvorson H O. Mutants of Bacillus cereus strain T that produce thermoresistant spores lacking dipicolinic acid have low levels of calcium. Can J Microbiol. 1972;18:1139–1143. doi: 10.1139/m72-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Illades-Aguiar B, Setlow P. Studies of the processing of the protease which initiates degradation of small, acid-soluble proteins during germination of spores of Bacillus species. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2788–2795. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2788-2795.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Illades-Aguiar B, Setlow P. Autoprocessing of the protease that degrades small, acid-soluble proteins of spores of Bacillus species is triggered by low pH, dehydration and dipicolinic acid. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7032–7037. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.7032-7037.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis J C. Dormancy. In: Gould G W, Hurst A, editors. The bacterial spore. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 301–358. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindsay J A, Beaman T C, Gerhardt P. Protoplast water content of bacterial spores determined by buoyant density gradient sedimentation. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:735–737. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.2.735-737.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loshon C A, Genest P C, Setlow B, Setlow P. Formaldehyde kills spores of Bacillus subtilis by DNA damage, and small, acid-soluble spore proteins of the α/β-type protect spores against this DNA damage. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;87:8–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margolis P S, Driks A, Losick R. Sporulation gene spoIIB from Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1993;174:528–540. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.2.528-540.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marquis R E, Bender G R. Mineralization and heat resistance of bacterial spores. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:789–791. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.2.789-791.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murrell W G. The biochemistry of the bacterial endospore. Adv Microbiol Physiol. 1967;1:133–251. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murrell W G, Warth A D. Composition and heat resistance of bacterial spores. In: Campbell L L, Halvorson H O, editors. Spores III. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1965. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicholson W L, Setlow P. Sporulation, germination and outgrowth. In: Harwood C R, Cutting S M, editors. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. pp. 391–450. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paidhungat M, Setlow P. Role of Ger proteins in nutrient and non-nutrient triggering of spore germination in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2513–2519. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.9.2513-2519.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piggot P J, Moir A, Smith D A. Advances in the genetics of Bacillus subtilis differentiation. In: Levinson H S, Sonenshein A L, Tipper D J, editors. Sporulation and germination. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1980. pp. 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Popham D L, Helin J, Costello C E, Setlow P. Muramic lactam in peptidoglycan of Bacillus subtilis spores is required for spore outgrowth but not for spore dehydration or heat resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15405–15410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Popham D L, Illades-Aguiar B, Setlow P. The Bacillus subtilis dacB gene, encoding penicillin-binding protein 5*, is part of a three gene operon required for proper spore cortex synthesis and spore core dehydration. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4721–4729. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4721-4729.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Popham D L, Sengupta S, Setlow P. Heat, hydrogen peroxide, and UV resistance of Bacillus subtilis spores with increased core water content and with or without major DNA binding proteins. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3633–3638. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.10.3633-3638.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rotman Y, Fields M L. A modified reagent for dipicolinic acid analysis. Anal Biochem. 1967;22:168. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(68)90272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell A D. Bacterial spores and chemical sporicidal agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:99–119. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanchez-Salas J-L, Santiago-Lara M L, Setlow B, Sussman M D, Setlow P. Properties of mutants of Bacillus megaterium and Bacillus subtilis which lack the protease that degrades small, acid-soluble proteins during spore germination. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:807–814. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.807-814.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanchez-Salas J-L, Setlow P. Proteolytic processing of the protease which initiates degradation of small, acid-soluble, proteins during germination of Bacillus subtilis spores. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2568–2577. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.9.2568-2577.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Setlow B, Setlow P. Dipicolinic acid greatly enhances the production of spore photoproduct in bacterial spores upon ultraviolet irradiation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:640–643. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.2.640-643.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Setlow B, Setlow P. Binding of small, acid-soluble spore proteins to DNA plays a significant role in the resistance of Bacillus subtilis spores to hydrogen peroxide. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3418–3423. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.10.3418-3423.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Setlow B, Setlow P. Small, acid-soluble proteins bound to DNA protect Bacillus subtilis spores from killing by dry heat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2787–2790. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2787-2790.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Setlow P. Biochemistry of bacterial forespore development and spore germination. In: Levinson H S, Tipper D J, Sonenshein A L, editors. Sporulation and germination. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1981. pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Setlow P. Germination and outgrowth. In: Hurst A, Gould G W, editors. The bacterial spore. II. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 211–254. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Setlow P. Small acid-soluble, spore proteins of Bacillus species: structure, synthesis, genetics, function and degradation. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1988;42:319–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.42.100188.001535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Setlow P. Mechanisms which contribute to the long-term survival of spores of Bacillus species. J Appl Bacteriol. 1994;76:49S–60S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1994.tb04357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Setlow P. Resistance of bacterial spores. In: Storz G, Hengge-Aronis R, editors. Bacterial stress responses. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 2000. pp. 217–230. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tennen R, Setlow B, Davis K L, Loshon C A, Setlow P. Mechanisms of killing of spores of Bacillus subtilis by iodine, glutaraldehyde and nitrous acid. J Appl Microbiol. 2000;89:1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wise J, Swanson A, Halvorson H O. Dipicolinic acid-less mutants of Bacillus cereus. J Bacteriol. 1967;94:2075–2076. doi: 10.1128/jb.94.6.2075-2076.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zytkovicz T H, Halvorson H O. Some characteristics of dipicolinic acid-less mutant spores of Bacillus cereus, Bacillus megaterium, and Bacillus subtilis. In: Halvorson H O, Hanson R, Campbell L L, editors. Spores V. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1972. pp. 49–52. [Google Scholar]