Abstract

Cutaneous-type adnexal tumors involving the breast are rare and create a diagnostic dilemma as they are often indistinguishable from primary mammary neoplasms. Tumors showing hair follicular differentiation are particularly challenging due to their rarity and the subtle appreciation of the intricate microanatomy of the hair follicle. We report a triple negative cutaneous-type adnexal carcinoma with follicular differentiation involving the breast to bring attention to the existence of these specialized group of tumors which should be managed differently from conventional triple negative carcinomas of the breast.

Keywords: breast, cutaneous, adnexal tumors, follicular differentiation

Introduction

Cutaneous-type adnexal tumors involving the breast are rare and often indistinguishable from primary mammary neoplasms due to morphological mimicry, a well-described phenomenon in tumor pathology. Similar to ductal carcinomas of the breast, these tumors can show both in situ and invasive components with multilineal differentiation including follicular, sebaceous, apocrine, and eccrine units. 1 Tumors derived from or with hair follicular differentiation are especially challenging due to the complex microanatomy of the hair follicle. 2 An understanding of this microanatomy and salient histological features can facilitate categorization of these tumors based on the follicular anatomic part or component whose morphology they recapitulate. 2

We report a triple negative cutaneous-type adnexal carcinoma with follicular differentiation involving the breast that proved to be diagnostically challenging. The purpose of this case report is to bring attention to the existence of these specialized group of tumors which should be managed differently from conventional triple negative carcinomas of the breast.

Case Report

A 74-year-old female presented with 3 months history of right breast pain. Bilateral diagnostic mammogram showed focal asymmetry measuring 1.5 cm in the right retroareolar region. Additional imaging by ultrasound revealed a hypoechoic mass measuring 1.1 × 1.0 × 1.0 cm in the right retroareolar breast, appearing to be contiguous with the nipple. This was reportedly palpable. No dominant mass, distortion, or suspicious calcifications were identified in the left breast. No adenopathy was seen.

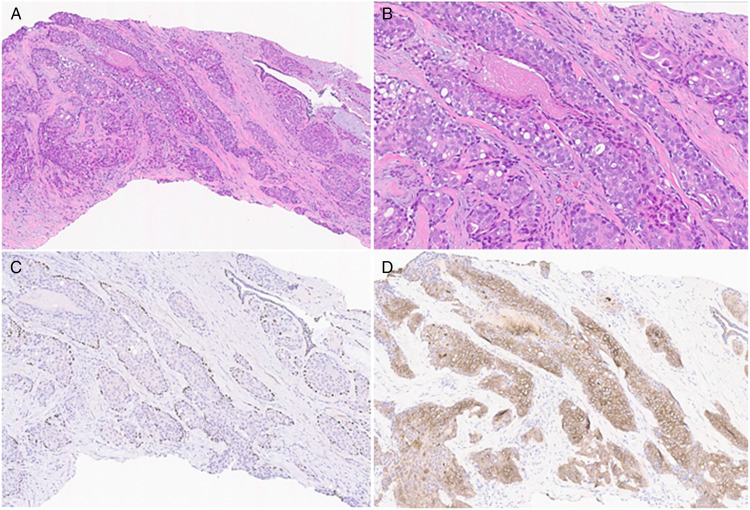

Ultrasound-guided biopsy of the mass showed atypical glandular proliferation (Figure 1A and B). By immunohistochemistry, p63 immunoreactivity highlighted myoepithelial cells surrounding solid nests of atypical cells with a low to intermediate nuclear grade (Figure 1C). Focal and inconspicuous central necrosis was present (Figure 1B). Minute clusters of atypical cells devoid of myoepithelial cells were also identified. However, due to the background dense stroma, definitive characterization was not possible. Smooth muscle myosin (SMMS-1) immunohistochemical stain was negative for myoepithelial cells surrounding these nests, however, the staining pattern was considered to be secondary to attenuation of the myoepithelial cell cytoplasm. In addition, keratin (KRT) 5/6 immunohistochemical stain was diffusely positive throughout the atypical glandular proliferation (Figure 1D). As such, definitive diagnosis was deferred to the excisional specimen.

Figure 1.

Histological examination of the core biopsy showing intraductal proliferation of atypical cells with low to intermediate nuclear grade nuclei and focal necrosis (A and B). A p63 immunohistochemical stain highlighting myoepithelial cells surrounding solid nests of atypical cells (C). KRT5/6 immunohistochemical stain is diffusely positive throughout the glandular epithelium (D).

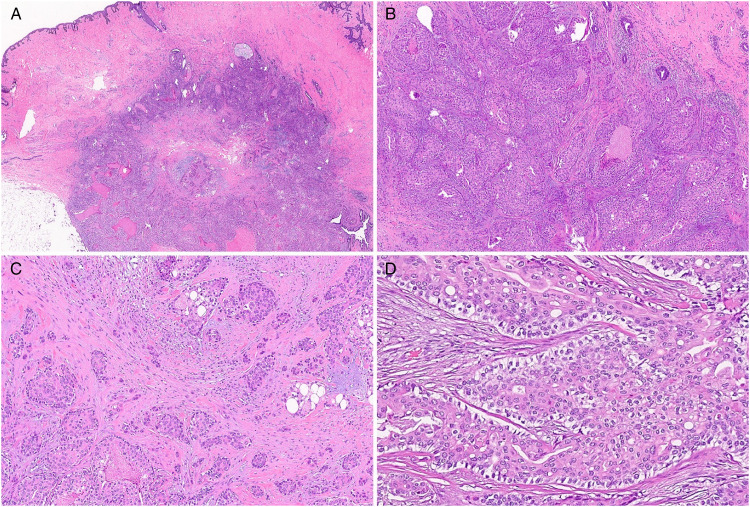

The patient subsequently had excisional biopsy of the right breast lesion with nipple-areolar complex removal. On gross examination, the nipple was everted and the areola was unremarkable. Serial sections revealed a tan-yellow to white densely fibrotic cut surface with the fibrotic area spanning 6 cm underlying the nipple. No distinct lesion was readily identified. Microscopic examination showed a well-circumscribed intermediate grade nodular tumor with pushing borders involving the base of the nipple and arrector pili muscle (Figure 2A). Expanded lobules of carcinoma in situ were seen with solid nests of polygonal cells that infiltrated the dermis and the breast emanating from the in situ component (Figure 2B-C). Though inconspicuous, the invasive component which consisted of both squamoid and ductal cell differentiation measured at least 10 mm. Upon further review, trichilemmal differentiation was identified by the presence of cells with pale to clear cytoplasm surrounded by a palisaded cell layer situated on top of a brightly eosinophilic basement membrane confirming the presence of an in situ adnexal component (Figure 2D). Foci of trichilemmal keratinization were also identified. Lymphovascular space invasion was absent. The tumor approached 2 of the resection margins.

Figure 2.

Histological examination of the excision showing the tumor at the base of the nipple (A). Expanded lobules of carcinoma in situ are seen infiltrating the dermis (B). Invasive component (C). Trichilemmal differentiation in which cells with pale to clear cytoplasm are surrounded by a palisaded cell layer situated on top of a brightly eosinophilic basement membrane (D).

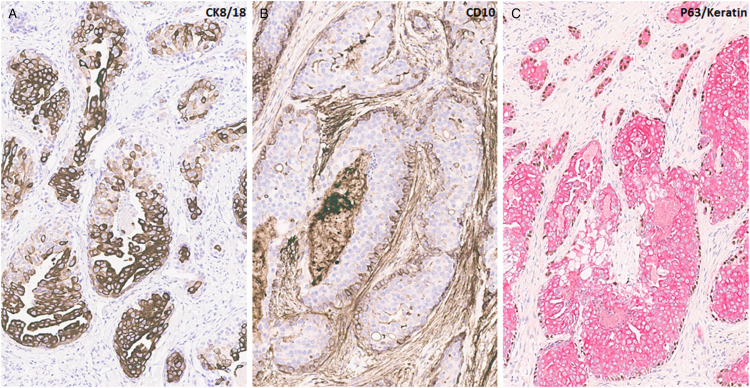

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed, and a summary of the results is shown in Table 1. The tumor was positive for markers of basal differentiation including KRT5/6, KRT17, and KRT14. KRT8/18 stained most luminal cells in the in situ component and the central tumor cells in the infiltrating component of the tumor (Figure 3A). CD10 showed focal retained myoepithelial cells in the in situ component (Figure 3B). p63/keratin duo stain highlighted the basal and myoepithelial dual differentiation of tumor cells (Figure 3C). The tumor cells had absent staining for SMMS and calponin. Adipophilin staining pattern was nonspecific. Trichorhinophalangeal syndrome type 1 (TRPS1), mammaglobin, and GATA binding protein 3 (GATA3) were positive while gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 (GCDFP-15) was negative. The tumor was essentially negative for estrogen receptor (>1%), negative for progesterone receptor (0) and negative for Her 2 with a score of 0. Androgen receptor was also negative (0). High-risk and low-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) evaluation by in situ hybridization was negative in the tumor. Molecular testing by next-generation sequencing (Boston Gene tumor portrait) was notable for PTEN gene loss, PIK3CA R1 Q705HfS37 loss of function variant allele frequency (VAF 18.7%), CDKN2A/B loss, and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I loss of heterozygosity with a tumor mutation burden of 0.59mut/Mb. Tumor origin was reported as most likely breast cancer with a prediction probability of 100%. The prediction probability was 93.2% for basal breast cancer and 63.5% for nonbasal breast cancer. However, the gene portrait could not differentiate basal breast cancer from cutaneous adnexal carcinoma.

Table 1.

Summary of Immunohistochemical Analysis of Tumor.

| Immunohistochemical Markers | Staining in Central/Luminal Epithelial Cells | Staining in Outer Layer/myoepithelial Cells |

|---|---|---|

| KRT5/6 | + | − |

| KRT7 | + | − |

| KRT17 | + | + |

| KRT14 | + | + |

| KRT8/18 | + | − |

| p63/keratin | + (keratin) | + (p63) |

| Adipohilin | − | − |

| CEA | + (patchy) | + (focal) |

| CD10 | − | + |

| SMMS | − | − |

| Calponin | − | − |

| DOG1 | − | − |

| EMA | + | − |

| Ber-EP4 | + (patchy) | − |

| TRPS1 | + | + |

| GATA3 | + | + |

| Mammaglobin | + (focal) | − |

Abbreviations: CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; DOG1, discovered on gastrointestinal stromal tumours 1; EMA, epithelial membrane antigen; KRT, keratin; SMMS, smooth muscle myosin.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical studies show KRT8/18 staining in most luminal cells in the in situ component and the central tumor cells in the infiltrating component of the tumor (A). CD10 highlighting retained myoepithelial cells in the in situ component (B). A p63/keratin duo stain highlighting the basal and myoepithelial dual differentiation of tumor cells (C).

As the tumor was likely to behave like specialized triple negative adnexal/salivary gland type carcinomas in the breast, a re-excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy was performed. Additional excision showed residual in situ and invasive carcinoma with histological features identical to the infiltrating component of the primary tumor. The invasive carcinoma was >2 mm from the new margin. Rare isolated tumor cells, which may have been introduced by the prior biopsy procedure, were identified in the right axillary sentinel lymph node. The patient subsequently received adjuvant radiation therapy and is currently doing well.

Discussion

Cutaneous-type adnexal tumors are a complex group of neoplasms reported to show one or several features of differentiation along follicular, sebaceous, apocrine, and eccrine lines. 3 When involving the breast, they are often indistinguishable from primary mammary neoplasms thus creating a diagnostic dilemma. Tumors showing hair follicular differentiation are particularly challenging due to their rarity and the subtle appreciation of the intricate microanatomy of the hair follicle. An understanding of this microanatomy and salient histological features can facilitate categorization of these tumors based on the follicular anatomic part or component whose morphology they recapitulate. 2

As an overview, hair follicular microanatomy is divided into the inferior follicle (bulb and suprabulbar regions), isthmus, and infundibulum, each with distinct histological features that provides helpful clues in the recognition of tumors demonstrating hair follicular differentiation. 4 For instance, tumors arising from the hair matrix in the bulbar region show matrical morphology with scant basophilic cytoplasm, voluminous round nuclei with prominent nucleolus, and a high mitotic rate. Tumors with differentiation recapitulating the outer root sheath, one of two sheath layers best appreciated on horizontal sections of the hair follicle with extension from the bulb to the base of the infundibulum, are characterized by cells with pale to clear glycogenated cytoplasm surrounded by a palisaded cell layer with nuclei oriented opposite to a brightly eosinophilic basement membrane.2,5

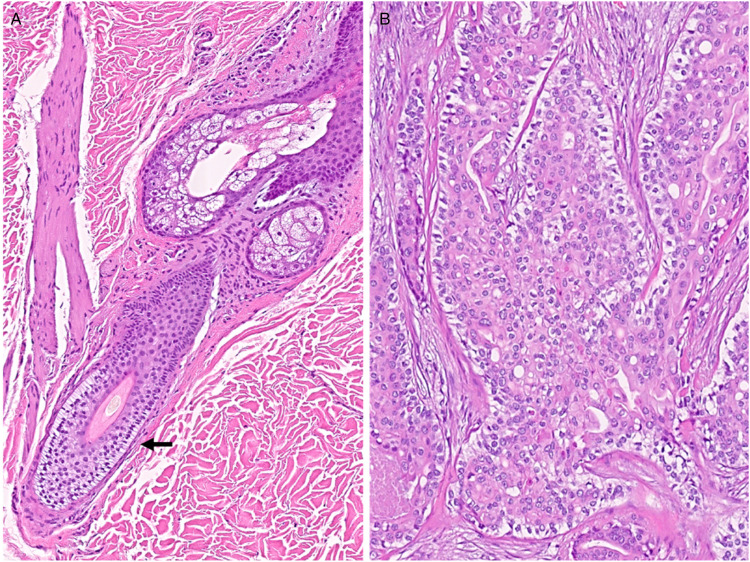

Involvement of the breast by cutaneous-type adnexal tumors have been reported in the literature.3,6-17 However, only a few of these exhibit follicular differentiation. In some of the cases, the tumor seemed to have arisen from the overlying skin and adnexa and in other cases, the tumor appeared to have originated de novo from the breast with no connection to the overlying skin.7,17 In one of the reported cases, the tumor which appeared benign, showed composite features of trichoblastic germinative differentiation with pilar-type keratinization and focal clear cell morphology similar to follicular outer root sheath while the second reported case was an invasive mammary carcinoma with adnexal differentiation of trichoblastic type infiltrating the dermis. Histologically, this tumor showed solid sheets and nests of basaloid cells exhibiting moderately pleomorphic nuclei, small nucleoli, and nuclear grooves with pseudo cystic spaces. 17 In our patient, the tumor also showed follicular differentiation but with features that mostly resemble outer root sheet morphology (Figure 4A and B) and appeared to have originated from the hair follicular adnexae adjacent to the nipple-areolar complex, not too unlike the 2 cases mentioned previously. Sebocytes were also identified within the current tumor which is not unusual, given the shared embryological origin and proximity to the hair follicle.

Figure 4.

The outer root sheath (arrow) showing cells with pale to clear glycogenated cytoplasm surrounded by a palisaded cell layer with nuclei oriented opposite to a brightly eosinophilic basement membrane (A). Tumor showing features similar to that of the outer root sheet (B).

In our patient, the invasive component consisted of both squamoid and ductal cell differentiation similar to the infiltrating process in low-grade adenosquamous carcinoma, a rare variant of metaplastic breast carcinoma. This overlapping feature, viewed in the absence of an intraductal follicular differentiation, could result in misdiagnosis and improper management. Included in the differential diagnosis is malignant adenomyoepithelioma (mAME). Adenomyoepitheliomas also have a dual biphasic epithelial and myoepithelial cell population, which is classically arranged with compactly situated well-differentiated tubular structures lined by plump abluminal myoepithelial cells. Intraductal papillary growth merging with architectural features of papilloma are helpful in establishing the diagnosis of adenomyoepithelioma. These findings are in contradistinction with our case, where a distinctive palisading layer of cells showing specialized trichilemmal hair follicular differentiation are situated on top of an eosinophilic basement membrane, present in both the invasive and in situ component. With few exceptions, surgical excision with adequate margins is often sufficient for locoregional control in primary cutaneous adnexal neoplasms. 18 However, primary breast carcinomas require a different approach that may include extensive surgery, sampling of the sentinel lymph nodes and consideration of neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant therapy. A combination of the clinical history, imaging, and identification of the anatomic relation of the lesion such as the presence of adjacent adnexal structure or development from surrounding breast parenchyma is necessary for proper characterization.

Immunohistochemistry, though nonspecific, can be helpful in differentiating primary cutaneous adnexal carcinoma from primary breast carcinoma when multiple markers are used in combination with tumor morphology.19,20 Most cutaneous folliculosebaceous tumors will show dual positivity with strong nuclear and cytoplasmic positivity for p63 and KRT5/6, respectively, as seen in our case. The p63 staining of the basal layer should not be confused with a ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) where the myoepithelial cells are positive for p63. KRT5/6 should be negative in the neoplastic cells in the setting of luminal-type DCIS but can be positive in basal-like in situ carcinoma. 21 Furthermore, the pattern of p63 expression in tumor cells can vary. Many solid primary cutaneous tumors such as squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, porocarcinoma, hidradenocarcinoma, will show a diffuse pattern of staining for p63. 18 In the rare cases of basal-like and metaplastic invasive mammary carcinomas showing diffuse p63 and KRT5/6 expression, care should be taken when interpreting the stains and discriminating which cell component is immunoreactive as well as correlation with histology. Foci of clear cells, peripheral palisading and pilar-type keratinization are features not typically seen in invasive mammary carcinoma and if identified can aid in rendering the correct diagnosis. Markers expressed in follicular epithelium and those reported in tumors showing follicular differentiation including KRT7, 8, 18, and 19 can be helpful when evaluating these cases.1,22,23 CD34 expression also supports outer root sheath differentiation. 1

The use of immunostains to identify site of origin is also helpful when working up cutaneous-type adnexal tumors involving the breast. GATA3, mammaglobin, GCDFP-15, and estrogen receptor immunoreactivity are useful in identifying breast as the site of origin. However, cutaneous epithelial neoplasms can also show varied expression of given the shared embryogenesis between these 2 groups of tumors. GCDFP-15 is a marker of apocrine differentiation and is more sensitive in apocrine carcinoma and breast carcinomas with apocrine differentiation.24,25 TRPS1 is less helpful in discriminating mammary origin from cutaneous tumors as immunoreactivity has been reported in some cutaneous tumors.26,27

Unfortunately, to date, molecular comparison is not helpful in discriminating this carcinoma of trichilemmal hair follicular differentiation from other triple negative biphasic carcinomas occurring in the breast as limited genetic data on these tumors exist. PTEN and PIK3CA loss of function was the most notable features in the molecular analysis of this tumor. Neither TP53 mutation nor HRAS mutation were identified. Importantly, tumors harboring both HRAS and PIK3CA mutations have been reported in other carcinomas with biphasic patterns of growth, including breast epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma and adenomyoepitheliomas.28-30 Once this tumor of trichofollucilar derivation is more broadly recognized, more cases will be identified and studied to determine its distinct molecular signature.

In conclusion, we report a case of nonconventional invasive triple negative adnexal carcinoma involving the breast and showing follicular differentiation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the third such case reported in the literature and the first with detailed molecular analysis. These tumors are rare and pose diagnostic difficulty when involving the breast as they may mimic primary ductal carcinomas. It is important to make the distinction as the wrong diagnosis and improper management can have untoward consequences for the patient as cutaneous adnexal carcinomas are low-grade tumors. Cursory review of a biopsy from the breast showing in situ carcinoma may result in the diagnosis of ductal carcinoma, not otherwise specified. The awareness of a KRT5/6-positive ductal carcinoma with distinct clear cell change, nuclear palisading and a prominent eosinophilic basement layer will direct the pathologist to the correct diagnosis of carcinoma arising from a cutaneous adnexal structure, once the superficial location of the tumor is noted. The findings of negative hormone immunoreactivity support this diagnosis and should not lead to the erroneous diagnosis of conventional triple negative breast carcinoma.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

ORCID iD: Oluwaseyi Olayinka https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2873-4711

References

- 1.Crowson AN, Magro CM, Mihm MC. Malignant adnexal neoplasms. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(Suppl 2):S93‐126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marušić Z, Calonje E. An overview of hair follicle tumours. Diagn Histopathol. 2020;26(3):128‐134. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kazakov DV, Spagnolo DV, Kacerovska D, Rychly B, Michal M. Cutaneous type adnexal tumors outside the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33(3):303‐315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho J, Bhawan J. Folliculosebaceous neoplasms: a review of clinical and histological features. J Dermatopathol. 2017;44(3):2359–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tellechea O, Cardoso JC, Reis JPet al. et al. Benign follicular tumors. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(6):780‐796. quiz 797-798. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20154114. PMID: 26734858; PMCID: PMC4689065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taghipour S, Shiryazdi SM, Sharahjin NS. Cylindroma of the breast in a 72-year-old woman with fibrocystic disease first misdiagnosed as a malignant lesion in imaging studies. Case Reports. 2013;2013:bcr2013010266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gököz Ö, Presenti L, Gambacorta Get al. Skin-type adnexal tumor with trichoblastic germinative differentiation in the breast: a case report. Int J Surg Pathol. 2011;19(4):527‐533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kazakov DV, Vanecek T, Belousova IE, Mukensnabl P, Kollertova D, Michal M. Skin-type hidradenoma of the breast parenchyma with t(11;19) translocation: hidradenoma of the breast. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29(5):457‐461. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e318156d76f. PMID: 17890914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finck FM, Schwinn CP, Keasbey LE. Clear cell hidradenoma of the breast. Cancer. 1968;22(1):125‐135. doi: . PMID: 4298177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albores-Saavedra J, Heard SC, McLaren B, Kamino H, Witkiewicz AK. Cylindroma (dermal analog tumor) of the breast: a comparison with cylindroma of the skin and adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123(6):866‐873. doi: 10.1309/CRWU-A3K0-MPQH-QC4 W. PMID: 15899777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gokaslan ST, Carlile B, Dudak M, Albores-Saavedra J. Solitary cylindroma (dermal analog tumor) of the breast: a previously undescribed neoplasm at this site. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(6):823‐826. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200106000-00017. PMID: 11395563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nonaka D, Rosai J, Spagnolo D, Fiaccavento S, Bisceglia M. Cylindroma of the breast of skin adnexal type: a study of 4 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004 Aug;28(8):1070‐1075. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000126774.27698.27. PMID: 15252315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Domoto H, Terahata S, Sato K, Tamai S. Nodular hidradenoma of the breast: report of two cases with literature review. Pathol Int. 1998;48(11):907‐911. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1998.tb03860.x. PMID: 9832062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murakami A, Kawachi K, Sasaki T, Ishikawa T, Nagashima Y, Nozawa A. Sebaceous carcinoma of the breast. Pathol Int. 2009;59(3):188‐192. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02349.x. PMID: 19261098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Švajdler M, Baník P, Poliaková Ket al. Sebaceous carcinoma of the breast: report of four cases and review of the literature. Pol J Pathol. 2015;66(2):142‐148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alencar NN, Souza DA, Lourenço AA, Silva RR. Sebaceous breast carcinoma. Autopsy Case Rep. 2022;12:e2021365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ravindran S, Rajadurai P, Daniel JM, Har YC. Invasive carcinoma of breast with adnexal differentiation of trichoblastic type. J Interdiscip Histopathol. 2016;4(2):48‐51. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shin SJ. A comprehensive guide to core needle biopsies of the breast. Springer Nature; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahalingam M, Nguyen LP, Richards JE, Muzikansky A, Hoang MP. The diagnostic utility of immunohistochemistry in distinguishing primary skin adnexal carcinomas from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin: an immunohistochemical reappraisal using cytokeratin 15, nestin, p63, D2-40, and calretinin. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(5):713‐719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valencia-Guerrero A, Dresser K, Cornejo KM. Utility of immunohistochemistry in distinguishing primary adnexal carcinoma from metastatic breast carcinoma to skin and squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40(6):389‐396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Middleton LP, Wang J. Basal-like atypical ductal hyperplasia and basal-like ductal carcinoma in situ: evidence for precursor of basal-like breast cancer. Int J Path Res. 2022;8(2):132. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohnishi T, Watanabe S. Immunohistochemical analysis of cytokeratin expression in various trichogenic tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21(4):337‐343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haas N, Audring H, Sterry W. Carcinoma arising in a proliferating trichilemmal cyst expresses fetal and trichilemmal hair phenotype. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24(4):340‐344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viacava P, Naccarato AG, Bevilacqua G. Spectrum of GCDFP-15 expression in human fetal and adult normal tissues. Virchows Arch. 1998;432(3):255‐260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazoujian G, Pinkus GS, Davis S, Haagensen DE, Jr. Immunohistochemistry of a gross cystic disease fluid protein (GCDFP-15) of the breast. A marker of apocrine epithelium and breast carcinomas with apocrine features. Am J Pathol. 1983;110(2):105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho WC, Ding Q, Wang WLet al. Immunohistochemical expression of TRPS1 in mammary Paget disease, extramammary Paget disease, and their close histopathologic mimics. J Cutan Pathol. 2023;50(5):434-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zengin HB, Bui CM, Rybski K, Pukhalskaya T, Yildiz B, Smoller BR. TRPS1 is differentially expressed in a variety of malignant and benign cutaneous sweat gland neoplasms. Dermatopathology. 2023;10(1):75‐85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krings G, Chen YY. Genomic profiling of metaplastic breast carcinomas reveals genetic heterogeneity and relationship to ductal carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2018;31(11):1661‐1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geyer FC, Li A, Papanastasiou ADet al. Recurrent hotspot mutations in HRAS Q61 and PI3K-AKT pathway genes as drivers of breast adenomyoepitheliomas. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baum JE, Sung KJ, Tran H, Song W, Ginter PS. Mammary epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma: report of a case with HRAS and PIK3CA mutations by next-generation sequencing. Int J Surg Pathol. 2019;27(4):441‐445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]