Abstract

Background

Sepsis is a life‐threatening condition for which critically important antimicrobials are often indicated. The value of blood culture for sepsis is indisputable, but appropriate guidelines on sampling and interpretation are currently lacking in cattle.

Objective

Compare the diagnostic accuracy of 2 blood culture media (pediatric plus [PP] and plus aerobic [PA]) and hypoglycemia for bacteremia detection. Estimate the contamination risk of blood cultures in critically ill calves.

Animals

One hundred twenty‐six critically ill calves, 0 to 114 days.

Methods

Retrospective cross‐sectional study in which the performance of PP, PA and hypoglycemia to diagnose sepsis was assessed using a Bayesian latent class model. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to compare time to positivity (TTP). Potential contamination was descriptively analyzed. Isolates were considered relevant when they were; member of the Enterobacterales, isolated from both blood cultures vials, or well‐known, significant bovine pathogens.

Results

The sensitivities for PP, PA, and hypoglycemia were higher when excluding assumed contaminants; 68.7% (95% credibility interval = 30.5%‐93.7%), 87.5% (47.0%‐99.5%), and 61.3% (49.7%‐72.4%), respectively. Specificity was estimated at 95.1% (82.2%‐99.7%), 94.2% (80.7%‐99.7%), and 72.4% (64.6%‐79.6%), respectively. Out of 121 interpretable samples, 14.9% grew a presumed contaminant in PA, PP, or both. There was no significant difference in the TTP between PA and PP.

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

PA and PP appear to outperform hypoglycemia as diagnostic tests for sepsis. PA seems most sensitive, but a larger sample size is required to verify this. Accuracy increased greatly after excluding assumed contaminants. The type of culture did not influence TTP or the contamination rate.

Keywords: contamination, hemoculture, rational antimicrobial use, sepsis, volume

Abbreviations

- BC

blood culture

- BLCM

Bayesian latent class model

- CI

credibility interval

- CIA

critically important antimicrobials

- covDn

covariance in disease negative animals

- covDp

covariance in disease positive animals

- NAS

non‐Staphylococcus aureus staphylococci

- PA

plus aerobic blood culture

- PP

pediatric plus blood culture

- TTP

time to positivity

1. INTRODUCTION

Sepsis is a life‐threatening disease in cattle that, similar to other species, requires timely initiation of appropriate antimicrobial therapy to maximize survival. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 In humans, broad‐spectrum, bactericidal, intravenously administrated antimicrobials are recommended. 7 This translates often in the need for fluoroquinolones or 3rd/4th generation cephalosporins. According to the World Health Organization and European Medicines Agency, both classes are classified as critically important antimicrobials (CIA). While the United States prohibits the use of fluoroquinolones and intravenous cephalosporins for this indication, certain European countries still allow their use in cattle, albeit under strict legislation. 8 , 9 , 10 A key aspect of these laws is mandatory bacterial culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing, requiring an appropriate sample. 10 , 11 , 12 To date, blood culture (BC) remains the imperfect gold standard to confirm bacteremia in sepsis‐suspected patients, as it allows isolation of the bacteria involved and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Nevertheless, it lacks accuracy since the bacterial density in bloodstream infections is generally low (affecting sensitivity) and false‐positive BC (contamination) are frequent (affecting specificity). 13 Limited studies on BC from calves and minimal research on optimal sampling techniques force veterinarians to resort to human literature. 4 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 In humans, BC volume proved crucial for more sensitive bacterial detection, even when taking more recent automated BC systems into account. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 Furthermore, an inverse association between volume and contamination rate has been observed. 22 In human hospitals, a contamination rate of 3% is considered acceptable. 23 , 24 Contamination of BC can result in inappropriate/unnecessary antimicrobial treatment, prolonged hospital stay and increased (laboratory) costs. 23 , 25 , 26 Multiple BC sampling techniques have been described in animals, but a standardized methodology has not been established. 27 Human guidelines concerning sample volume vary from 2 to 4 BC sets (20‐30 mL/set) per patient, stating the need for at least 40 mL of blood. 7 , 13 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 Depending on body weight, different types of BC media and volumes are advised (eg, pediatric). In smaller animals, pediatric flasks are often used because low blood volumes are obtained, but also in larger animals since sampling large volumes from nonstationary animals is impractical. 4 , 32 However, the use of these pediatric flasks can be questioned in light of available literature discussing volume and sensitivity as stated above. There is a need for a protocol for postblood draw handling of samples obtained from sepsis‐suspected calves and specific criteria to interpret them. Plus, BC should be compared to other more rapid diagnostic tests detecting sepsis in calves, such as hypoglycemia, easily applicable as cow‐side test and previously associated with sepsis in calves. 33 , 34 , 35 , 36

Therefore, the first objective of this study was to compare 2 commercially available aerobic BC vials and hypoglycemia to detect bacteremia in critically ill calves. The second objective was to estimate the contamination rate of these 2 BC media in calves in a hospital setting.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design, study sample, and sample size

A retrospective cross‐sectional study was conducted to evaluate 2 different culture media to isolate bacteria involved in sepsis‐suspected critically ill calves. Convenience sampling was used to collect blood samples from critically ill calves admitted to the university clinic (2018‐2022), which were placed immediately into either pediatric plus (PP) and plus aerobic (PA) BC vials (BD, Erembodegem, Belgium). Inclusion criteria were an age of <4 months and presence of critical illness. Critical illness was defined as severe respiratory (tachypnea/dyspnea), cardiovascular (tachycardia/bradycardia/prolonged capillary refill time/abnormal jugular vein filling time) or neurological derangement (posture/mental state), apart or in combination. 4 , 37 Description of the methodology used for clinical examination is available elsewhere. 4 Details about prior treatment were obtained from the medical history. Sample size was calculated based on an expected sepsis prevalence of 30%. 4 , 14 , 17 With this assumed prevalence of 30%, a null hypothesis value of 0.70 and alternative hypothesis value of 0.9, a minimum of 103 samples was needed to detect a difference in sensitivity and specificity of 20% with 80% power. 38

2.2. Study parameters

2.2.1. Sampling

Blood samples were collected from the jugular vein in heparin‐coated tubes (Venoject, Terumo, Leuven, Belgium) and immediately analyzed for glycemia (RAPIDPoint 405 Siemens Healthcare, Beersel, Belgium). Subsequently, the other jugular vein and surrounding area were prepared by clipping, scrubbing (chlorhexidine Gluconate 4%, Hibiscrub, Mölnlycke Health Care NV, Berchem, Belgium) and disinfection (iso‐Propanol, 99.8% C3H8O, Chemlab, Zedelgem, Belgium). After letting the skin air dry, blood was aseptically taken with sterile gloves from the jugular vein using a 21G needle and a 20 mL syringe to sample 13 mL (1 venipuncture). A second needle was used to inject the blood in both BC flasks (2‐needle technique) after disinfection of the lid. 23 The maximum recommended blood volumes were added; 3 mL for PP (glass flask) and 10 mL for PA (plastic flask). Information on the composition of the flask media used can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

2.2.2. Blood culture sample processing

Both BC bottles were aerobically incubated at 35°C in an automated BACTEC FX system for microbial growth detection. Blood culture vials were in the detection system <1 hour after collection. When a BC is signaled positive (based on CO2 detection), the time to positivity (TTP) is automatically displayed and manually written down upon evacuation of the sample. In case the system gave no signal after 120 hours, the BC was considered negative. Blood cultures with a positive signal were stored (4°C) and shipped (4°C) the same or next day to an external laboratory (Dierengezondheidszorg Vlaanderen), where bacterial identification was executed using MALDI‐TOF MS after aerobic subculturing (35°C) on Columbia agar with 5% sheep blood, MacConkey agar no. 3 for gram‐negative enteric bacteria, and Columbia agar supplemented with oxolinic acid to isolate mainly streptococci.

2.2.3. Interpretation of blood culture results

The sampled volume (13 mL) of each calf was split into 2 flasks. Both flasks combined were considered 1 BC, given that only 1 large volume was sampled. Bacteria isolated from positive BC can either be true sepsis pathogens or contaminants. An attempt was made to distinguish these through the joint effort of a clinical bacteriologist (Diplomate ECVM) and a clinician specialized in ruminants. To differentiate “likely contaminants” from “likely true pathogens,” certain assumptions described in human medicine were applied; bacteria were considered true pathogens when they were members of the Enterobacterales or when they were isolated out of both aerobic BC flasks. 16 , 23 , 24 In addition, when the identified organism was a well‐known significant bovine pathogen in other pathologies (pneumonia, mastitis, peritonitis, …), it was also categorized as likely true pathogen, even if only isolated from 1 culture flask. In case the BACTEC FX system signaled positive, but no microbiological isolate could be detected (negative culture result), it was categorized as a contaminant. When no bacteria could be evidenced because of human errors (eg, sample not sent to the external lab), it was defined as “no identification of a pathogen.” The “assumed contamination risk” was calculated as the number of positive BC with assumed contaminants divided by the total number of positive detected samples. The “overall assumed contamination risk” was calculated in 2 manners; by assessing the ratio of positive BC with assumed contaminants to the total number of sampled BC, and by determining the ratio of flasks with assumed contaminants to the total number of sampled flasks (PP and PA). 23

The relationship between previous antimicrobial therapy (yes/no) before sampling and BC detection was determined with logistic regression in SPSS. The antimicrobial therapy vs BC positivity was tested per BC as well as per vial (PP and PA separately).

2.2.4. Interpretation of glycemia values

Blood glucose concentration was measured with the RAPIDPoint (glucose oxidase method) and categorized binary (<60 mg/dL = 1) using a cut‐off known to increase mortality of critically ill calves. 36 Time to last nursing was not taken into account, as it was assumed that the critical condition of the animals prevented them from recent drinking/suckling.

2.3. Statistical analysis

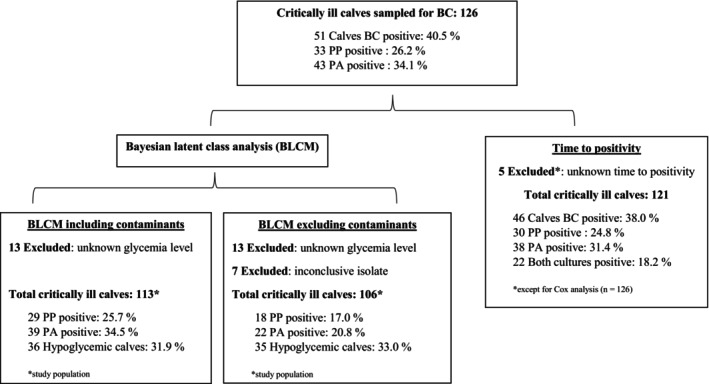

The list of values excluded from each statistical analysis is shown in Figure 1. Significance of P‐values was set at P < .05, and .05 ≤ P ≤ .1 was considered a trend.

FIGURE 1.

Information about critically ill calves included in the study population for both Bayesian latent class analysis to determine the performance of PP and PA media for blood culture vials, and blood glucose, as well as the study population for the time to positivity analysis. BC, blood culture; BLCM, Bayesian latent class modeling; PA, plus aerobic (standard volume 8‐10 mL); PP, pediatric plus (small volume 1‐3 mL)

2.3.1. Diagnostic performance with Bayesian latent class model

To account for the issue that no gold standard test for sepsis is available (ie, sensitivity and specificity not 100%), a Bayesian latent class model (BLCM) approach was chosen to estimate the diagnostic accuracy. This method does not assume prior superiority of 1 method over another by creating its own probabilistic definition of the outcome studied. 39 We selected hypoglycemia as a third test because it has been associated with sepsis in humans and animals before. 33 , 35 , 36 , 40 It is obvious that both BC media detect living bacteria and are therefore conditionally dependent. Although hypoglycemia is assumed to be correlated with bacteremia, it does not directly detect bacteria, but likely detects a metabolite associated with the sepsis pathway and can therefore be regarded as independent compared to the BC media. Normality of distribution of glucose, analyzed with a histogram (SPSS), showed left skewing. For the BLCM, the glucose was binary coded (1 < 60 mg/dL; 0 ≥ 60 mg/dL), thus left skewing should not influence the Bayesian analysis.

Obtained data were transferred from Excel to WINBUGS (v1.4.3.; MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK) to determine sensitivity and specificity with a 1 population 3‐test Bayesian latent class analysis. Current dataset was based on a study sample derived from a single population since the university hospital is the only clinic for calves in this part of the country, meaning the study sample originates from multiple farms throughout the country. Given that animals come in 1 at a time, we consider this independent observations from 1 population, though the same prevalence of sepsis was found in different populations (diarrheic calves, critically ill calves) in previous literature. 4 , 14 , 17 A conditionally dependent BLCM model was made using a WINBUGS code shared by Dr S. Buczinski (University of Montreal) (Supplementary Table 2). To be complete, we also performed the conditionally independent tests. 41 , 42 The unknown parameters were the prevalence of sepsis in the population, the sensitivity, specificity, the covariance in disease positive‐animals (covDp) and covariance in disease‐negative animals (covDn) of the 3 diagnostic tests, being PP, PA and hypoglycemia. Dendukuri and Joseph parametrization was used to help the model converge more rapidly, since it restricts the prior to positive covariance between tests. 43 In BLCM models, prior information on the prevalence or diagnostic test used can be added to narrow parameter uncertainty. These priors are modeled using beta distributions (0 to 1). We constructed 3 different models. In the first (uninformed) model, all priors were parametrized as a beta‐distribution (1). Prior information about sepsis prevalence in calves (mode, 30%; 5th percentile, 90%) was gathered from literature (used in model 3), 14 , 17 while expert opinion (Diplomate ECBHM and multiple bovine clinicians) was used to estimate sensitivity (mode, 60%; 5th percentile, 70%) and specificity (mode, 70%; 5th percentile, 60%) of hypoglycemia as a diagnostic test for sepsis (model 2 and 3). Beta distributions of the corresponding prior distributions were obtained through Epitools (Ausvet). 44 For each model, 100 000 iterations were run, with a burn‐in of 5000 iterations, and thinning set at 1. Density and Gelman‐Rubin plots were inspected to observe the model convergence, whereas the need for thinning of chains was evaluated by reviewing the plots of chain autocorrelation. Subsequently, for each parameter, the median, and 95% credibility intervals (95% CI) values were gathered. 41 A sensitivity analysis for robustness was performed by running alternative models with different (extreme) prior specifications, and median estimates were checked to be in the range of the 95% CI of the final model (model 3). Model fit was compared by means of the deviance information criterion (DIC). The Youden index was calculated (sensitivity [%] + specificity [%] − 100) to compare the diagnostic performance of different models.

We performed the BLCM analysis twice, once including assumed contaminants (1/both flasks positive, BC considered positive regardless of the bacterium), and a second time with recoding of contaminants as negative results. Unknown culture results were excluded in the second model. The STARD‐BLCM guidelines were followed for this study. 45

2.3.2. Time to positivity

Data were entered in SPSS statistics vs 27.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Cohen's Kappa (κ) was calculated as a parameter of test agreement, both before and after excluding contaminants. 46 , 47 TTP was defined as the time (hours) between the start of incubation in the automated system and the detection of microbial growth (based on CO2 concentration). A Cox proportional hazards model was constructed to compare the hazard of a positive BC between PP and PA media. Right censoring was done for each calf with a negative BC (>120 hours). Kaplan‐Meier survival curves were constructed to visualize the difference in TTP. Walds's test was used to assess parameter estimate significance. Model fit was evaluated by inspection of the log cumulative hazard plots.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study sample

The study sample consisted of 126 critically ill calves (Supplementary Table 3), surpassing the calculated required sample size with ±20%. An overview of the number of cases included in each analysis is provided in Figure 1. The mean ± SD and median (range) age of the calves were 13.6 ± 18.9 and 8 (0‐114) days, respectively. In 1 calf, the exact age was not recorded, but it met the criteria <4 months, and was therefore included in further analysis. The study included 67 (53.2%) male calves, 54 (42.9%) female, and 5 (4.0%) calves of unknown sex. Of the animals, 102 were of the Belgian Blue breed (81.0%), 17 Holstein Friesian (13.5%), 3 Blonde d'Aquitaine (2.4%), 2 mixed breeds (1.6%), 1 Maine Anjou (0.8%), and 1 Partenais (0.8%). The mean ± SD and median (range) body weight were 57.9 ± 14.4 and 60 (26‐100) kg, respectively, while in 36.5% (n = 46) of the calves, the body weight was not recorded.

3.2. Parameters

3.2.1. Hypoglycemia

Mean ± SD and median (range) blood glucose concentrations were 82.2 ± 48.9 and 78 (20‐340) mg/dL, respectively. Information about glycemia was missing in 13 cases. Hypoglycemia (<60 mg/dL) was present in 31.9% (36/113) of the cases.

3.2.2. Blood culture results

In total 40.5% (51/126) of the calves had at least 1 positive BC vial, resulting in a total number of 76 positive vials (1 or 2 positive/calf). In 75 calves none of the vials was positive. There were 34.1% (43/126) PA and 26.2% (33/126) PP vials positive (Table 1). The Cohen's Kappa value of 0.514 indicates a moderate agreement between PP and PA results (including contaminants). 46 Recalculation after excluding contaminants resulted in a Cohen's Kappa value of 0.839.

TABLE 1.

3 × 3 cross table including information on blood culture vial positivity of pediatric plus aerobic culture (PP) in comparison to standard plus aerobic (PA) media and information on glycemia for 113 samples.

| Number PA (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | Total | |||

| Number without hypoglycemia (%) | Number PP (%) | Negative | 51 (91.1) | 11 (52.4) | 62 (80.5) |

| Positive | 5 (8.9) | 10 (47.6) | 15 (19.5) | ||

| Total | 56 (72.7) | 21 (27.3) | 77 (100) | ||

| Number with hypoglycemia (%) | Number PP (%) | Negative | 16 (88.9) | 6 (33.3) | 22 (61.1) |

| Positive | 2 (11.1) | 12 (66.7) | 14 (38.9) | ||

| Total | 18 (50.0) | 18 (50.0) | 36 (100) | ||

| Total (%) | Number PP (%) | Negative | 67 (90.5) | 17 (43.6) | 84 (74.3) |

| Positive | 7 (9.5%) | 22 (56.4) | 29 (25.7) | ||

| Total | 74 (65.5) | 39 (34.5) | 113 (100) | ||

Table 2 displays the isolated bacteria and their putative classification as true pathogen or contaminant. The most frequently isolated assumed true pathogens were Escherichia coli (n = 14) and Salmonella sp. (n = 5). In 19.8% (25/126) of the calves, both PP and PA were positive. Only in 1 calf different bacteria were isolated out of PP and PA (Chryseobacterium hominis and Acinetobacter johnsonii, respectively). In 4 cases with both PA and PP positivity, the result of only 1 of both flasks was available (the other 1 was not identified because of human errors for example, not sent to laboratory or results lost in laboratory). The cases where Streptococcus uberis and Salmonella sp. were isolated, were classified as a true pathogen (relevant bovine pathogen, member of the Enterobacterales, or both), whereas in the cases where Lactococcus garvieae and Microbacterium lacticum were isolated, no conclusion was possible (not known relevant bovine pathogen, nor member of the Enterobacterales, and isolate in second vial unknown), and were therefore excluded from the second BLCM taking contamination into account (Table 4).

TABLE 2.

Overview of isolated bacteria out of 76 positive pediatric (PP) and/or aerobic plus (PA) blood culture media in 51 critically ill calves.

| Pathogen | Positive PA + PP | Positive PP | Positive PA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 10 | 1 | 3 |

| Salmonella sp. | 3 | 1 | 1 |

|

Staphylococcus spp. Including S. xylosus (2) S. chromogenes (1), S. sciuri (1), S. sp. (1) |

2 | 1 | 2 |

| Raoultella ornithinolytica | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Trueperella pyogenes | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Campylobacter jejuni | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Polybacterial | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Gram positive cocci | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Aerococcus viridans | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Brevibacillus borstelensis | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Paenibacillus amylolyticus | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Lactococcus garvieae | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Chryseobacterium hominis | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Streptococcus uberis | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Negative culture result a | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Acinetobacter johnsonii | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Bacillus cereus | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Bacillus sp. | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Globicatella sp. | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Microbacterium lacticum | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Not identified b | 0 | 3 | 4 |

Note: Contamination was classified in “likely contamination” (red) and “likely relevant pathogen” (green). Based on type of bacteria and frequency of isolation of the bacterium.

Abbreviations: PA, plus aerobic (standard volume 8‐10 mL); PP, pediatric plus (small volume 1‐3 mL).

BACTEC FX system signaled positive, but no microbiological isolate could be detected.

No results because of loss of data (laboratory/clinician).

TABLE 4.

BLCM including information on posterior median and 95% credible interval values for conditional dependent BLCMs for the prevalence of sepsis in calves and the sensitivity and specificity for sepsis diagnosis with hypoglycemia (<60 mg/dL) and positive aerobic plus and peds plus blood culture vials, with exclusion of results of blood culture vials assumed to be contaminated.

| Model 1: no priors | Model 2: se/sp hypoglycemia | Model 3: sepsis prevalence + se/sp hypoglycemia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Prior density | Posterior density (median % [95% CI]) | Prior density | Posterior density (median % [95% CI]) | Prior density | Posterior density (median % [95% CI]) |

| Hypoglycemia | ||||||

| Sensitivity | Beta (1,1) | 71.5 (21.4‐98.0) | Beta (34.44, 23.29) | 61.3 (49.3‐72.4) | Beta (34.44, 23.29) | 61.3 (49.7‐72.4) |

| Specificity | Beta (1,1) | 75.1 (20.5‐93.3) | Beta (47.53, 20.94) | 72.3 (64.5‐79.9) | Beta (47.53, 20.94) | 72.4 (64.6‐79.6) |

| Pediatric plus | ||||||

| Sensitivity | Beta (1,1) | 61.3 (11.1‐91.2) | Beta (1,1) | 69.1 (30.8‐93.9) | Beta (1,1) | 68.7 (30.5‐93.7) |

| Specificity | Beta (1,1) | 92.2 (56.6‐99.4) | Beta (1,1) | 95.1 (82.2‐99.7) | Beta (1,1) | 95.1 (82.2‐99.7) |

| Aerobic plus | ||||||

| Sensitivity | Beta (1,1) | 82.6 (12.5‐99.4) | Beta (1,1) | 87.8 (47.7‐99.5) | Beta (1,1) | 87.5 (47.0‐99.5) |

| Specificity | Beta (1,1) | 91.2 (36.4‐99.5) | Beta (1,1) | 94.2 (80.6‐99.7) | Beta (1,1) | 94.2 (80.7‐99.7) |

| Prevalence | Beta (1,1) | 18.7 (4.8‐84.9) | Beta (1,1) | 19.0 (5.2‐34.4) | Beta (1.16, 1.38) | 19.2 (5.8‐34.8) |

| covDp | U (0, a) | 0.05 (−0.03 to 0.19) | U (0, a) | 0.03 (−0.03 to 0.18) | U (0, a) | 0.03 (−0.03 to 0.18) |

| covDn | U (0, b) | 0.05 (0.00015‐0.15) | U (0, b) | 0.03 (0.00016‐0.13) | U (0, b) | 0.03 (−0.00017 to 0.13) |

| DIC | 28.0 | 30.7 | 30.7 | |||

Abbreviations: CI, credibility interval; covDn, covariance for negatives; covDp, covariance for positives; DIC, deviance information criterion; Se, sensitivity; Sp, specificity.

In 40.5% (51/126) of the cases the BC was positive, but in 5 calves no conclusion concerning contamination was possible because of missing laboratory results. Of the remaining 46 positive BC samples, 39.1% (n = 18) were considered contaminated (=assumed contamination risk). In 60.9% (28/46) samples a true pathogen was isolated.

The overall assumed contamination (contamination/all BC) for the 121 interpretable cultures was 14.9% (18/121) and for all flasks (contamination/all flasks) was 7.9% (19/242) (10 flasks inconclusive). In 23.1% (28/121) of all interpretable cases, it was assumed that a true pathogen was identified.

When antimicrobials were given before sampling, the odds of detecting bacteremia were significantly lower when all BC were included (OR = 0.42; 95% CI = 0.18‐0.94; P = .04). When calculating the same after excluding likely contaminants for BC positivity, these results were not significant (OR = 0.60; 95% CI = 0.24‐1.5; P = .28). The bacterial detection in the PP culture was significantly lower when antimicrobials were given (OR = 0.38; 95% CI = 0.16‐0.90; P = .03), while a trend was seen for PA (OR = 0.47; 95% CI = 0.21‐1.1; P = .08) (all positive flasks included).

3.3. Diagnostic performance

3.3.1. Bayesian latent class model

Prior and posterior densities of the different dependent models for positive BC are provided in Table 3. As expected, the DIC showed a better fit for the dependent model (Table 3) in comparison to the independent model (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). The first model did not converge, but when prior information was added (models 2 and 3) only a small difference between these 2 models was observed. The final model's sensitivities (3rd model) were 58.6% (CI = 46.6%‐70.3%) for hypoglycemia, 68.7% (30.8%‐97.7%) for PP, and 80.2% (42.2%‐98.8%) for PA. Specificities were 73.0% (65.0%‐80.3%) for hypoglycemia, 87.6% (72.4%‐98.4%) for PP, and 78.9% (63.6%‐95.7%) for PA. The Youden index was 0.32 for hypoglycemia, 0.56 for PP, and 0.59 for PA. Sepsis prevalence was estimated at 23.9% (5.9%‐44.2%) in this model.

TABLE 3.

BLCM including information on posterior median and 95% credible interval values for conditional dependent BLCMs for the prevalence of sepsis in calves and the sensitivity and specificity for sepsis diagnosis with hypoglycemia (<60 mg/dL) and positive aerobic plus and peds plus blood culture vials.

| Model 1: no priors a | Model 2: se/sp hypoglycemia | Model 3: sepsis prevalence + se/sp hypoglycemia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Prior density | Posterior density (median % [95% CI]) | Prior density | Posterior density (median % [95% CI]) | Prior density | Posterior density (median % [95% CI]) |

| Hypoglycemia | ||||||

| Sensitivity | Beta (1,1) | 54.4 (12.6‐94.6) | Beta (34.44, 23.29) | 58.7 (46.7‐70.5) | Beta (34.44, 23.29) | 58.6 (46.8‐70.3) |

| Specificity | Beta (1,1) | 75.8 (27.1‐94.5) | Beta (47.53, 20.94) | 72.9 (64.9‐80.3) | Beta (47.53, 20.94) | 73.0 (65.0‐80.3) |

| Pediatric plus | ||||||

| Sensitivity | Beta (1,1) | 57.6 (9.5‐95.9) | Beta (1,1) | 68.9 (30.0‐97.9) | Beta (1,1) | 68.7 (30.8‐97.7) |

| Specificity | Beta (1,1) | 85.2 (33.7‐98.4) | Beta (1,1) | 87.3 (72.1‐98.3) | Beta (1,1) | 87.6 (72.4‐98.4) |

| Aerobic plus | ||||||

| Sensitivity | Beta (1,1) | 71.0 (15.1‐98.3) | Beta (1,1) | 80.3 (40.6‐98.9) | Beta (1,1) | 80.2 (42.2‐98.9) |

| Specificity | Beta (1,1) | 77.1 (22.1‐97.0) | Beta (1,1) | 78.6 (63.2‐95.5) | Beta (1,1) | 78.9 (63.6‐95.7) |

| Prevalence | Beta (1,1) | 28.0 (4.7‐88.3) | Beta (1,1) | 23.4 (4.8‐44.3) | Beta (1.16, 1.38) | 23.9 (5.9‐44.2) |

| covDp | U (0, a) | 0.05 (−0.08 to 0.17) | U (0, a) | 0.02 (−0.06 to 0.17) | U (0, a) | 0.02 (−0.06 to 0.17) |

| covDn | U (0, b) | 0.04 (−0.02 to 0.15) | U (0, b) | 0.04 (−0.008 to 0.13) | U (0, b) | 0.04 (−0.008 to 0.12) |

| DIC | 32.6 | 36.9 | 36.9 | |||

Abbreviations: CI, credibility interval; covDn, covariance for negatives; covDp, covariance for positives; DIC, deviance information criterion; Se, sensitivity; Sp, specificity.

Model did not converge.

The second BLCM model (Table 4) was made after the classification of contaminants. This resulted in sensitivities of 61.3% (49.7‐72.4) for hypoglycemia, 68.7% (30.5%‐93.7%) for PP and 87.5% (47.0%‐99.5%) for PA. Specificities were 72.4% (64.6%‐79.6%) for hypoglycemia, 95.1% (82.2%‐99.7%) for PP, and 94.2% (80.7%‐99.7%) for PA. The Youden index for the BLCM after reclassifying contaminants was 0.34 for hypoglycemia, 0.64 for PP and 0.82 for PA. Sepsis prevalence was estimated at 19.2% (5.8‐34.8) for this model.

Sensitivity analysis showed that both final models were highly robust to changes in the prior distribution. Only slight deviations from the 95% credible interval of model 3 were observed when extremely unrealistic high prevalence (90%) or extremely low specificity (20%) for both culture media were used.

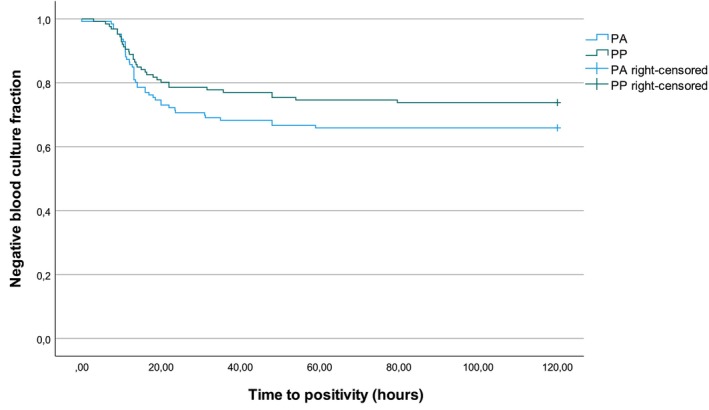

3.3.2. Time to positivity

Time to positivity was known in 32 and 38 cases for PP and PA media, respectively. Purely based on BC vial positivity, thus disregarding the effect of assumed contaminants, the mean ± SD and median (range) TTP of the PP flasks were 19.55 ± 16.71 and 13.34 (3‐79.63) hours, respectively. For the PA flasks mean and median (range) TTP were 17.75 ± 12.38 and 13.15 (0‐59.00) hours, respectively.

When taking the classification for contamination into account, TTP for PP was 20.4 ± 9.06 and 18.19 (9.98‐35.72) hours for assumed contaminants and 19.27 ± 18.73 and 11.94 (3.00‐79.63) hours for assumed true PP pathogens. Time to positivity for PA was 25.41 ± 15.38 and 20.29 (8‐59.00) hours for assumed contaminants, while 14.22 ± 9.04 and 11.19 (0‐48.00) hours for assumed true pathogens. Time to positivity was not significantly different between PP and PA (P = .18; Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan‐Meier curve of the negative blood culture fraction (y‐axis) of the aerobic (PA) and pediatric aerobic (PP) blood culture vials plotted against the time to positivity (x‐axis; 126 cases; 2018‐2022; Log Rank test: χ 2 1.83; df = 1; P = .18).

4. DISCUSSION

Diagnosing sepsis in cattle remains a challenge. The detection of bacteremia using BC has been linked with an increased risk of death in critically ill calves, but there are few guidelines on using and interpreting BC in calves. 4 Therefore, the first objective of this study was to compare performance of 2 types of aerobic BC flasks and hypoglycemia as diagnostic tests for sepsis. The second objective was to estimate the prevalence of contamination in these BC.

To evaluate the performance of the PP, PA, and hypoglycemia as diagnostic tests for sepsis, we determined sensitivity, specificity, and the Youden Index (measurement of overall diagnostic accuracy). Depending on the intended purpose of the BC, a high sensitivity, specificity, or both can be desired. Because of the high risk of death without antibiotic therapy in calves with septicemia, high sensitivity is desired to detect as many truly septicemic animals as possible that would benefit from antibiotic administration. 1 , 4 In contrast, a high specificity would increase the confidence level in a negative result to identify calves that are not septicemic. This way, clinicians can avoid unnecessary (long) antimicrobial use (quicker de‐escalation/termination of antimicrobial treatment in critically ill calves with negative blood culture), as well as related side effects, such as prolonged hospital stay, and increased antimicrobial resistance selection. 23 , 24 , 48 The highest estimated sensitivity, without excluding contaminants, was seen for PA (80.2%), followed by PP (68.7%), and hypoglycemia (58.6%). As the sensitivity of PA (largest inoculated blood volume) was the highest, this could indicate that we can extrapolate the human hypothesis: “a larger volume increases sensitivity” to cattle. 13 , 19 , 20 However, taking into account the wide credibility intervals, a definite conclusion based on current data is impossible, and a larger study population is required to determine if 1 test medium really outperforms the other. Next to the blood sample volume, other differences between PP and PA, such as slightly different culture medium composition, volume of medium present in the flasks (33 mL PA and 42 mL PP), glass vs plastic flasks or differences in negative pressure in the flasks, might have influenced their performance. Plus, in both vials different concentrations of resins are added to reduce antimicrobial concentrations of previous treatments (Supplementary Table 1), possibly affecting their performance.

Specificity for detecting sepsis was 78.9%, 87.6%, and 73% for PA, PP, and hypoglycemia, respectively. After reclassification of contaminants, using aforementioned criteria, there was practically no difference in specificity between PP and PA anymore. 24 The Youden index displayed only a small difference between PA and PP (0.59 vs 0.56) in the first BLCM (Table 3), while this difference was more pronounced after excluding assumed contaminants (2nd BLCM, Table 4) with 0.64 for PP and 0.82 for PA. Even though in our study glycemia seemed to lack accuracy as a diagnostic tool for sepsis in calves, it is still worth further exploration. It could support rapid in‐field decision‐making for sepsis as a cow‐side test, for example, as part of a score system or decision tree, in contrast to BC which usually take >24 hours before results are available. Further efforts to increase reliability of the interpretation of this test are therefore warranted.

The second aspect in which we compared the BC vials' performance, was their speed at which they turned positive. In this study, no significant difference in TTP was observed. Mean TTP of PP was longer (19.6 hours) in comparison with previous human studies (14.3 hours), but was comparable for the PA culture in calves (17.75 hours) and human literature (17.2 hours). 49 , 50 In relation to our second objective, estimating contamination rates in BC, it has been suggested in human medicine that prolonged TTP (>3 to 5 days) is indicative for contamination. 24 As only 1 flask containing a pathogen had a TTP > 3 days, current dataset did not allow investigating this aspect. The TTP of assumed contaminants compared to true pathogens was slightly longer, although this effect was mainly present in the PA (TTP assumed true pathogens 14.2 hours vs assumed contaminants 25.4 hours). The authors do not encourage using TTP as indicator for the cultured organism's relevance in calves, as bacterial species‐specific growth characteristics should be taken into account (eg, fastidiously growing organisms such as Trueperella pyogenes) and the TTP is influenced by the initial bacterial load in the blood sample.

Estimating the level of contamination in BC flasks (second objective) did not only suggest important levels of contamination in BC obtained from critically ill calves, it also showed that proper interpretation of BC results can help to increase the performance of these tests.

We established an assumed overall contamination rate of 14.9%, well above the acceptable threshold of 3% in human hospitals. 23 The overall contamination risk was high (39.1%) in comparison with the report of Story‐Roller and Weinstein (26.6%), but similar to numbers assessed by other infectious disease physicians (33%‐50%). 23 , 51 No significant difference was seen in the contamination rate between PP and PA, making the type of aerobic culture media appear irrelevant for the contamination risk. In the present study, multiple bacteria were isolated that were likely contaminants (eg, Bacillus spp. and Staphylococcus spp.). Even though non‐Staphylococcus aureus staphylococci (NAS) are usually (70%‐80%) regarded as contaminants, they appear to be of concern in people with prostheses and central venous catheters. 24 The relevance in calves sampled upon arrival in the clinic might be little. However, sampling large numbers of healthy calves could be useful to get insight into which bacteria are often detected in BC as contaminants.

In this study, 1 large blood sample was divided into 2 vials, to compare the different media. As discussed above and described in literature, double sampling facilitates contaminant exclusion. 52 Contrary to this study, we would advise taking 2 independent samples (separate venipunctures) to allow a meaningful interpretation on contamination. 13 However, given that collecting BC is already challenging and costly in practice, 2 independent sterile venipunctures (double sampling) might be an unattainable goal for the field veterinarian. In cases where double sampling is possible, the diagnostic reliability of the obtained BC results will nevertheless increase drastically. In addition, double sampling will likely reduce treatment costs, since treatment can be switched to appropriate less critical antimicrobials and prolonged unnecessary antimicrobials can be avoided. Next to double sampling, a good collaboration between microbiologists and clinicians is essential in interpreting the isolates as contaminants, since it requires both bacteriological knowledge and appropriate evaluation of the clinical condition of the animal to come to the most relevant interpretation of the BC results.

A last prominent finding after excluding presumed contaminants in BC was the substantial reduction in sepsis prevalence (40.5%‐22.2%), which was more similar to the prevalence determined with the final BLCM (19.2%) (Table 4), but lower compared to previous literature (±30%). 4 , 14 , 15 , 17 The lower prevalence in current study could be ascribed to contaminants being overlooked in prior publications or because the majority of the calves in this study were previously treated with antimicrobials. Previous treatment did decrease the odds of detecting bacteria (OR = 0.42; P = .04), however, this effect disappeared when only focusing on the likely true pathogens (P = .28). Despite this counterintuitive finding of previous treatment not lowering the chance of bacterial detection of true pathogens in BC, various hypotheses might offer an explanation. Animals previously treated with antibiotics, still presenting as critically ill, might harbor bacteria resistant to the administered product following selection pressure, while contaminants have been exposed to less selective pressure and thus might exhibit less antimicrobial resistance than true pathogens or occur in a lower bacterial load in BC, impairing their growth in the presence of antibiotics. In conclusion, current data set suggests that sampling animals, presenting as critically ill after previous antimicrobial treatment, for BC could still be valuable, as no significant reduction in the chance of isolation of true pathogens was observed.

A first limitation of this study is our Bayesian statistical method. Calculations are done based on a latent class, meaning that the analysis calculates the common ground between 3 tests in the absence of a gold standard, of which we assume is “bacteremia,” but for which there is no guarantee. Another important limitation is the number of missing data.

Conclusions regarding contaminants also entail risk; it is possible that certain bacterial isolates were missed in the flasks or during identification because culture conditions did not allow growth. Plus, both were tailored to aerobic bacteria, potentially missing significant anaerobic organisms. Additionally, considering contamination classification, it is not clear whether our criteria, based on human literature and expert opinion, lead to a correct estimation of contamination. For example, assuming all isolates of Enterobacterales as true pathogens might be questionable under veterinary conditions, such as difficult immobilization and asepsis (higher infection pressure of feces‐associated bacteria). For the second criterium, an important limitation is that both vials are inoculated with the same blood sample, meaning if a skin contaminant is involved, it is possible to be present in both flasks. For this study, we wanted to keep the number of variables between the vials as small as possible to properly compare them. However, for future research/sampling, it is crucial to perform 2 separate punctures for the second guideline to be fully applicable. Also, in current protocol, the same needle was used to inject both vials, resulting in the risk of transporting a bacterium from the first lid to the next. However, this was counteracted by disinfecting both lids. In addition, the third criterium of “highly relevant pathogens” is prone to interpretation. Furthermore, we classified flasks signaling positive with Bactec FX, without a microbe isolated, as contaminated. However, this could also be the result of an error of the automatic detection system, since for similar systems both false positive and negative results have been reported. 53 , 54 Another explanation for a negative culture result after positive signaling with Bactec FX could be the type of bacterium requiring specific growth conditions (eg, fastidiously growing organisms). The culturing was outsourced to an external lab, preventing us from reaching any definitive conclusions on negative culture results.

A limitation concerning the blood glucose measurements is that the device used was not validated specifically for cattle and that the glucose oxidase method was used instead of the reference method (hexokinase/glucose‐6‐phosphate dehydrogenase). However, Siemens blood gas systems software uses equations to correlate the glucose oxidase results with the reference method. Because of the fact that the results were interpreted qualitatively, we assume that the used method was of sufficient accuracy for the goals of the current study, which was determining the diagnostic performance of this (imperfect) test to detect sepsis.

As a final limitation, the practical feasibility for equivalent asepsis in field conditions can be questioned. The sampling methods used in this study are in line with the most important sampling recommendations. 23 Further decreasing the risk for contamination using BC kits, sterile drapes, a phlebotomy team and larger sampling volumes is possible, but likely the economic aspect outweighs the benefits. Taking this economic aspect and possibly higher levels of contamination risk in the field into account, it raises the question of whether BC in cattle should only be considered in veterinary hospital settings. However, given the emerging legislation worldwide to rationalize antimicrobial use and the increased concern of the public on antimicrobial use in livestock, the importance of determining the most appropriate sampling method for BC, and whether cow‐side alternatives are possible, is vital.

In conclusion, both culture media, PA and PP, appear to perform better compared to hypoglycemia as diagnostic tests for sepsis. Of both media, PA seems to have the highest sensitivity, but a larger sample size is required to validate this statement. However, the type of culture did not influence TTP or the contamination rate. With the help of basic guidelines, it appears possible to estimate the clinical relevance of most isolates. The importance of estimating contamination, in addition to avoiding unnecessary lab tests and unnecessary (lengthy) therapy, was evidenced in the improved performance of blood culture media when suspected contaminants were excluded.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DECLARATION

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

OFF‐LABEL ANTIMICROBIAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE (IACUC) OR OTHER APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no IACUC or other approval was needed.

HUMAN ETHICS APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare human ethics approval was not needed for this study.

Supporting information

Supplementary Table 1. Composition of BACTEC Plus Aerobic medium (plastic flask) BACTEC (PA) and Peds Plus medium (glass flask) (PP) (BD, Erembodegem, Belgium).

Supplementary Table 2. WINBUGS for both the independent and dependent BLCM model. Code shared by Dr S. Buczinski (University of Montreal).

Supplementary Table 3. Information of the included 126 critically ill calves on blood culture positivity, cardiovascular, respiratory or neurological derangement, mortality, clinical diagnosis and previous antimicrobial treatments.

Supplementary Table 4. BLCM including information on posterior median and 95% credible interval values for conditional independent BLCMs for the prevalence of sepsis in calves and the sensitivity and specificity for sepsis diagnosis with hypoglycemia (<60 mg/dL) and positive aerobic plus and peds plus blood cultures.

Supplementary Table 5. BLCM including information on posterior median and 95% credible interval values for conditional independent BLCMs for the prevalence of sepsis in calves and the sensitivity and specificity for sepsis diagnosis with hypoglycemia (<60 mg/dL) and positive aerobic plus and peds plus blood cultures, with exclusion of results of blood culture flasks assumed to be contaminated.

Supplementary Table 6. Information on time to positivity of the PP and PA culture of the isolated organism, as well as their information on gram‐positivity or ‐negativity and the assumed classification as pathogen or contaminant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Funding provided by the Belgian Federal Public Service Health, Food Chain Safety and Environment through the contract RF 21/6351 RATIOSEP, and by internal funding of the Large Animal Clinic of Ghent University. The authors thank all clinical investigators at internal medicine who aided in the data collection.

Pas ML, Boyen F, Castelain D, et al. Bayesian evaluation of sensitivity and specificity of blood culture media and hypoglycemia in sepsis‐suspected calves. J Vet Intern Med. 2024;38(3):1906‐1916. doi: 10.1111/jvim.17040

REFERENCES

- 1. Kumar A, Ellis P, Arabi Y, et al. Initiation of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy results in a fivefold reduction of survival in human septic shock. Chest. 2009;136:1237‐1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Montealegre F, Lyons BM. Fluid therapy in dogs and cats with sepsis. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:622127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pardon B, Deprez P. Rational antimicrobial therapy for sepsis in cattle in face of the new legislation on critically important antimicrobials. Vlaams Diergenskund Tijds. 2018;87:37‐46. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pas ML, Bokma J, Lowie T, Boyen F, Pardon B. Sepsis and survival in critically ill calves: risk factors and antimicrobial use. J Vet Intern Med. 2023;37:374‐389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roy MF. Sepsis in adults and foals. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2004;20:41‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vincent JL, Marshall JC, Namendys‐Silva SA, et al. Assessment of the worldwide burden of critical illness: the intensive care over nations (ICON) audit. Lancet Resp Med. 2014;2:380‐386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:304‐377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. European Medicines Agency . Categorisation of Antibiotics for Use in Animals for Prudent and Responsible Use. 2019. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/categorisation‐antibiotics‐used‐animals‐promotes‐responsible‐use‐protect‐public‐and‐animal‐health [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization . Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine: Ranking of Antimicrobial Agents for Risk Management of Antimicrobial Resistance Due to Non‐human Use. 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241515528 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Staatsblad B. Koninklijk besluit 21/07/2016 Koninklijk besluit betreffende de voorwaarden voor het gebruik van geneesmiddelen door de dierenartsen en door de verantwoordelijken van de dieren; 2016:46569‐46586. [Google Scholar]

- 11. (SDa) AD . Het gebruik van fluorochinolonen en derde en vierde generatie cefalosporines in landbouwhuisdieren. RvhSe; 2013:1‐24. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Köper LM, Bode C, Bender A, Reimer I, Heberer T, Wallmann J. Eight years of sales surveillance of antimicrobials for veterinary use in Germany—what are the perceptions? PloS One. 2020;15:e0237459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lamy B, Dargère S, Arendrup MC, Parienti JJ, Tattevin P. How to optimize the use of Blood cultures for the diagnosis of bloodstream infections? A state‐of‐the art. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fecteau G, Paré J, Van Metre DC, et al. Use of a clinical sepsis score for predicting bacteremia in neonatal dairy calves on a calf rearing farm. Can Vet J. 1997;38:101‐104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fecteau G, Smith BP, George LW. Septicemia and meningitis in the newborn calf. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2009;25:195‐208, vii‐viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Garcia J, Pempek J, Hengy M, Hinds A, Diaz‐Campos D, Habing G. Prevalence and predictors of bacteremia in dairy calves with diarrhea. J Dairy Sci. 2022;105:807‐817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lofstedt J, Dohoo IR, Duizer G. Model to predict septicemia in diarrheic calves. J Vet Intern Med. 1999;13:81‐88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Washington JA 2nd, Ilstrup DM. Blood cultures: issues and controversies. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8:792‐802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jonsson B, Nyberg A, Henning C. Theoretical aspects of detection of bacteraemia as a function of the volume of blood cultured. Apmis. 1993;101:595‐601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mermel LA, Maki DG. Detection of bacteremia in adults: consequences of culturing an inadequate volume of blood. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:270‐272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bouza E, Sousa D, Rodríguez‐Créixems M, et al. Is the volume of blood cultured still a significant factor in the diagnosis of bloodstream infections? J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:2765‐2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bekeris LG, Tworek JA, Walsh MK, Valenstein PN. Trends in blood culture contamination: a College of American Pathologists Q‐Tracks study of 356 institutions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:1222‐1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Doern GV, Carroll KC, Diekema DJ, et al. Practical guidance for clinical microbiology laboratories: a comprehensive update on the problem of blood culture contamination and a discussion of methods for addressing the problem. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;33:e00009‐e00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hall KK, Lyman JA. Updated review of blood culture contamination. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:788‐802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bates DW, Goldman L, Lee TH. Contaminant blood cultures and resource utilization. The true consequences of false‐positive results. Jama. 1991;265:365‐369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Burnham C‐AD, Yarbrough ML. Best practices for detection of bloodstream infection. J Appl Lab Med. 2019;3:740‐742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Giancola S, Hart KA. Equine blood cultures: can we do better? Equine Vet J. 2023;55:584‐592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Baron EJ, Scott JD, Tompkins LS. Prolonged incubation and extensive subculturing do not increase recovery of clinically significant microorganisms from standard automated blood cultures. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1677‐1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. O'Grady NP, Barie PS, Bartlett JG, et al. Guidelines for evaluation of new fever in critically ill adult patients: 2008 update from the American College of Critical Care Medicine and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1330‐1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Public Health England . UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations B 37: Investigation of Blood Cultures (for Organisms Other than Mycobacterium Species). UK Health Security Agency. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Accoceberry I, Cornet M, Lamy B. Hémoculture. REMIC, Référentiel en Microbiologie Médicale. 5th ed. Paris: Société française de Microbiologie; 2015:125‐137. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dumoulin M, Pille F, Van den Abeele A‐M, et al. Evaluation of an automated blood culture system for the isolation of bacteria from equine synovial fluid. Vet J. 2010;184:83‐87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Constable PD, Trefz FM, Sen I, et al. Intravenous and oral fluid therapy in neonatal calves with diarrhea or sepsis and in adult cattle. Front Vet Sci. 2020;7:603358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Radostits OM, Gay CC, Blood DC, Hinchcliff KW. Veterinary Medicine: A Textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Pigs, Goats and Horses. 10th ed. London: Saunders; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Trefz FM, Feist M, Lorenz I. Hypoglycaemia in hospitalised neonatal calves: prevalence, associated conditions and impact on prognosis. Vet J. 2016;217:103‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Trefz FM, Lorenz I, Lorch A, Constable PD. Clinical signs, profound acidemia, hypoglycemia, and hypernatremia are predictive of mortality in 1,400 critically ill neonatal calves with diarrhea. PloS One. 2017;12:e0182938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ostermann M, Sprigings D. The critically ill patient. In: Springings D, Chambers JB , eds. Acute Medicine. 5th ed. U.S: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2017:1‐8. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bujang MA, Adnan TH. Requirements for minimum sample size for sensitivity and specificity analysis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:YE01‐YE06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cheung A, Dufour S, Jones G, et al. Bayesian latent class analysis when the reference test is imperfect. Rev Sci Tech. 2021;40:271‐286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hollis AR, Furr MO, Magdesian KG, et al. Blood glucose concentrations in critically ill neonatal foals. J Vet Intern Med. 2008;22:1223‐1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bokma J, Vereecke N, Pas ML, et al. Evaluation of nanopore sequencing as a diagnostic tool for the rapid identification of mycoplasma bovis from individual and pooled respiratory tract samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;59:e0111021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rijckaert J, Raes E, Buczinski S, et al. Accuracy of transcranial magnetic stimulation and a Bayesian latent class model for diagnosis of spinal cord dysfunction in horses. J Vet Intern Med. 2020;34:964‐971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Branscum AJ, Gardner IA, Johnson WO. Estimation of diagnostic‐test sensitivity and specificity through Bayesian modeling. Prev Vet Med. 2005;68:145‐163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sergeant E. Epitools Epidemiological Calculators. Ausvet. Accessed December 2022. http://epitools.ausvet.com.au2018

- 45. Kostoulas P, Nielsen SS, Branscum AJ, et al. STARD‐BLCM: standards for the reporting of diagnostic accuracy studies that use Bayesian latent class models. Prev Vet Med. 2017;138:37‐47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22:276‐282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. WinEpi . Working in Epidemiology—Test Agreement . 2022. Accessed February 2023. http://www.winepi.net/

- 48. Lee CC, Lin WJ, Shih HI, et al. Clinical significance of potential contaminants in blood cultures among patients in a medical center. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2007;40:438‐444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Roh KH, Kim JY, Kim HN, et al. Evaluation of BACTEC Plus aerobic and anaerobic blood culture bottles and BacT/Alert FAN aerobic and anaerobic blood culture bottles for the detection of bacteremia in ICU patients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;73:239‐242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sullivan KV, Turner NN, Lancaster DP, et al. Superior sensitivity and decreased time to detection with the Bactec Peds Plus/F system compared to the BacT/Alert Pediatric FAN blood culture system. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:4083‐4086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Story‐Roller E, Weinstein MP. Chlorhexidine versus tincture of iodine for reduction of blood culture contamination rates: a prospective randomized crossover study. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:3007‐3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Weinstein MP. Blood culture contamination: persisting problems and partial progress. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2275‐2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Liu L, Du L, He S, et al. Subculturing and gram staining of blood cultures flagged negative by the BACTEC™ FX system: optimizing the workflow for detection of Cryptococcus neoformans in clinical specimens. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1113817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Qian Q, Tang YW, Kolbert CP, et al. Direct identification of bacteria from positive blood cultures by amplification and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene: evaluation of BACTEC 9240 instrument true‐positive and false‐positive results. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3578‐3582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. Composition of BACTEC Plus Aerobic medium (plastic flask) BACTEC (PA) and Peds Plus medium (glass flask) (PP) (BD, Erembodegem, Belgium).

Supplementary Table 2. WINBUGS for both the independent and dependent BLCM model. Code shared by Dr S. Buczinski (University of Montreal).

Supplementary Table 3. Information of the included 126 critically ill calves on blood culture positivity, cardiovascular, respiratory or neurological derangement, mortality, clinical diagnosis and previous antimicrobial treatments.

Supplementary Table 4. BLCM including information on posterior median and 95% credible interval values for conditional independent BLCMs for the prevalence of sepsis in calves and the sensitivity and specificity for sepsis diagnosis with hypoglycemia (<60 mg/dL) and positive aerobic plus and peds plus blood cultures.

Supplementary Table 5. BLCM including information on posterior median and 95% credible interval values for conditional independent BLCMs for the prevalence of sepsis in calves and the sensitivity and specificity for sepsis diagnosis with hypoglycemia (<60 mg/dL) and positive aerobic plus and peds plus blood cultures, with exclusion of results of blood culture flasks assumed to be contaminated.

Supplementary Table 6. Information on time to positivity of the PP and PA culture of the isolated organism, as well as their information on gram‐positivity or ‐negativity and the assumed classification as pathogen or contaminant.