Abstract

Introduction:

Neurofibrillary degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) typically involves the entorhinal cortex and CA1 subregion of the hippocampus early in the disease process, whereas in primary age-related tauopathy (PART), there is an early selective vulnerability of the CA2 subregion.

Methods:

Image analysis-based quantitative pixel assessments were used to objectively evaluate amyloid beta (Aβ) burden in the medial temporal lobe in relation to the distribution of hyperphosphorylated-tau (p-tau) in 142 cases of PART and AD.

Results:

Entorhinal, CA1, CA3, and CA4 p-tau deposition levels are significantly correlated with Aβ burden, while CA2 p-tau is not. Furthermore, the CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio is inversely correlated with Aβ burden and distribution. In addition, cognitive impairment is correlated with overall p-tau burden.

Discussion:

These data indicate that the presence and extent of medial temporal lobe Aβ may determine the distribution and spread of neurofibrillary degeneration. The resulting p-tau distribution patterns may discriminate between PART and AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid beta, image analysis, neurodegeneration, neurofibrillary degeneration, primary age-related tauopathy, tau

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common underlying cause of cognitive impairment worldwide. The neuropathologic diagnosis of AD is dependent on the presence of amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and abnormal hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) immunoreactive neurofibrillary degeneration, both of which are thought to progress through the brain in well-characterized patterns. While there is some degree of p-tau present in almost all individuals > 20 years of age, this remains largely of low burden and regionally confined to the brainstem and subcortical nuclei in younger adults.1,2 Neurofibrillary degeneration progresses from the medial temporal region to the neocortex in six successive Braak stages,3 while Aβ progresses from neocortex to limbic structures, brainstem, and cerebellum in five Thal phases.4 These changes are thought to be interrelated, and can be used to assess the overall severity of AD neuropathologic change (ADNC) in post mortem brain tissue.5

Primary age-related tauopathy (PART) is a term describing an Aβ-independent tauopathy characterized by 3R- and 4R-tau positive paired helical filaments (AD-type neurofibrillary tangles) that includes cases previously described as “tangle-only senile dementia,” “tangle-predominant senile dementia,” and “age-related neurofibrillary degeneration,” as well as non-demented individuals harboring tauopathy with a similar neuroanatomical distribution. The neurofibrillary degeneration in PART is largely confined to the medial temporal region, roughly corresponding to Braak stages I–IV. Recent evidence has suggested that this hierarchical progression of neurofibrillary degeneration does not correspond as well to cognitive status in PART as it does in AD.6,7 Two general categories of PART are currently recognized: “definite PART,” which consists of Braak stage I–IV neurofibrillary degeneration in the absence of any Aβ deposition (Thal phase 0 and Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease [CERAD] neuritic plaque [NP] score “absent”), and “possible PART,” which consists of Braak stage I–IV neurofibrillary degeneration with Thal phase 1–2 Aβ deposition and/or CERAD NP score “sparse.”8 Recent studies have demonstrated an early selective vulnerability for neurofibrillary degeneration in the CA2 hippocampal subregion, in contrast to AD, where the neurofibrillary degeneration is most severe in the entorhinal cortex and CA1 subregion initially, with relative sparing of CA2 until later in the disease course.7,9 It has also been suggested that non-demented elderly individuals without senile plaques may be separated into distinct groups: one with prominent CA2 neurofibrillary degeneration and one with a greater burden of disease in the entorhinal and CA1 subregion with relative CA2 sparing.10,11 Other differences between AD and PART have been described, including apolipoprotein E (APOE) allele status and MAPT haplotypes,12,13 although there has long been debate as to whether PART simply represents part of the ADNC spectrum.14,15

In this study, we examine the relationship between medial temporal lobe Aβ deposition and the neuroanatomical distribution of p-tau. Using image analysis–based assessments of whole slide images of immunohistochemically stained tissue sections, we objectively determined the positive pixel counts of Aβ and p-tau to explore how the p-tau burden in individual hippocampal subregions is affected by increasing Aβ burden. Our results suggest that the two processes are linked at the level of the hippocampus, resulting in divergent “PART-like” and “ADNC-like” patterns of hippocampal pathology.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Patient samples

One hundred forty-two autopsy cases from the previously described multi-institutional PART working group (PWG) cohort were used.6,7,16–19 The participants, 46% male, ranged in age from 61 to 108 years (mean age 89.5 ± 0.9 years), Braak stage from I to V, Thal phase from 0 to 4, and CERAD NP score “absent” to “frequent” (Table 1). Fifty individuals had a diagnosis of “definite” PART (Braak stage I–IV, Thal phase 0, and CERAD NP score “absent”), 73 individuals had a diagnosis of “possible” PART (Braak stage I-IV and Thal phase 1–2 and/or CERAD NP score “sparse”), and 19 individuals had a diagnosis of ADNC (Braak stage I-VI, Thal phase 3–5, and/or CERAD NP score “moderate” or “frequent”) to represent the full spectrum of p-tau and Aβ pathology in the entorhinal cortex and hippocampal subregions.5,7,8 Clinical exclusion criteria included patient age < 50 years and presence of frontotemporal dementia, movement disorder, or motor neuron disease.7 Cognitive information, including Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Global Score, was available for 98 subjects.

TABLE 1.

OverView of demographic, clinical, and pathologic features

| Thal phase | n | Age (years) | %Male | Braakstage |

CERAD NP score |

Cognitive status* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-II | III-IV | V-VI | None | Sparse+ | Normal | MCI | Dementia | ||||

| 0 | 53 | 88.3 ± 1.6 | 54% | 7 | 46 | 0 | 50 | 3 | 28 | 9 | 5 |

| 1 | 32 | 87.9 ± 2.0 | 44% | 0 | 32 | 0 | 31 | 1 | 14 | 12 | 5 |

| 2 | 46 | 93.8 ± 0.9 | 46% | 4 | 41 | 1 | 30 | 16 | 11 | 6 | 10 |

| 3 | 8 | 89.2 ± 4.2 | 33% | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 4 | 3 | 91.6 ± 1.3 | 0% | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total | 142 | 89.5 ± 0.9 | 46% | 13 | 126 | 3 | 116 | 26 | 55 | 19 | 24 |

Only a portion of cases had cognitive data available.

Abbreviations: CERAD, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NP, neuritic plaque.

2.2 |. Immunohistochemistry

Histological staining methods have been described previously.7 Briefly, hippocampal sections (level 7)20 and middle frontal gyrus sections were available for each case. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections (5 μm thick) were mounted on charged slides and baked at 70°C. Luxol Fast Blue/hematoxylin & eosin (LFB/H&E), Bielschowsky silver stain, phospho-tau (p-tau) immunohistochemistry (IHC; AT8; MN1020, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and Aβ IHC (6E10; SIG-39320, Covance, Inc.) were performed on all sections on a Leica Bond III automated stainer (Leica Biosystems), according to the manufacturer’s protocols. All slides were imaged to generate whole slide digital images using an Aperio CS2 scanner (Leica Biosystems) at 20x magnification at The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, TX). For each case, Braak stage (0–V)3, Thal phase (0–4)4, and CERAD NP score (“absent”–“frequent”)5 were reassessed in a previous publication using appropriate consensus criteria to ensure consistency in diagnoses.7 The relative density of p-tau and Aβ in each hippocampal subregion (entorhinal cortex, CA1/subiculum, CA2, CA3, and CA4) were assessed by a semi-quantitative scoring system (0–3), as previously described.7

2.3 |. Computer-assisted assessments of p-tau and Aβ

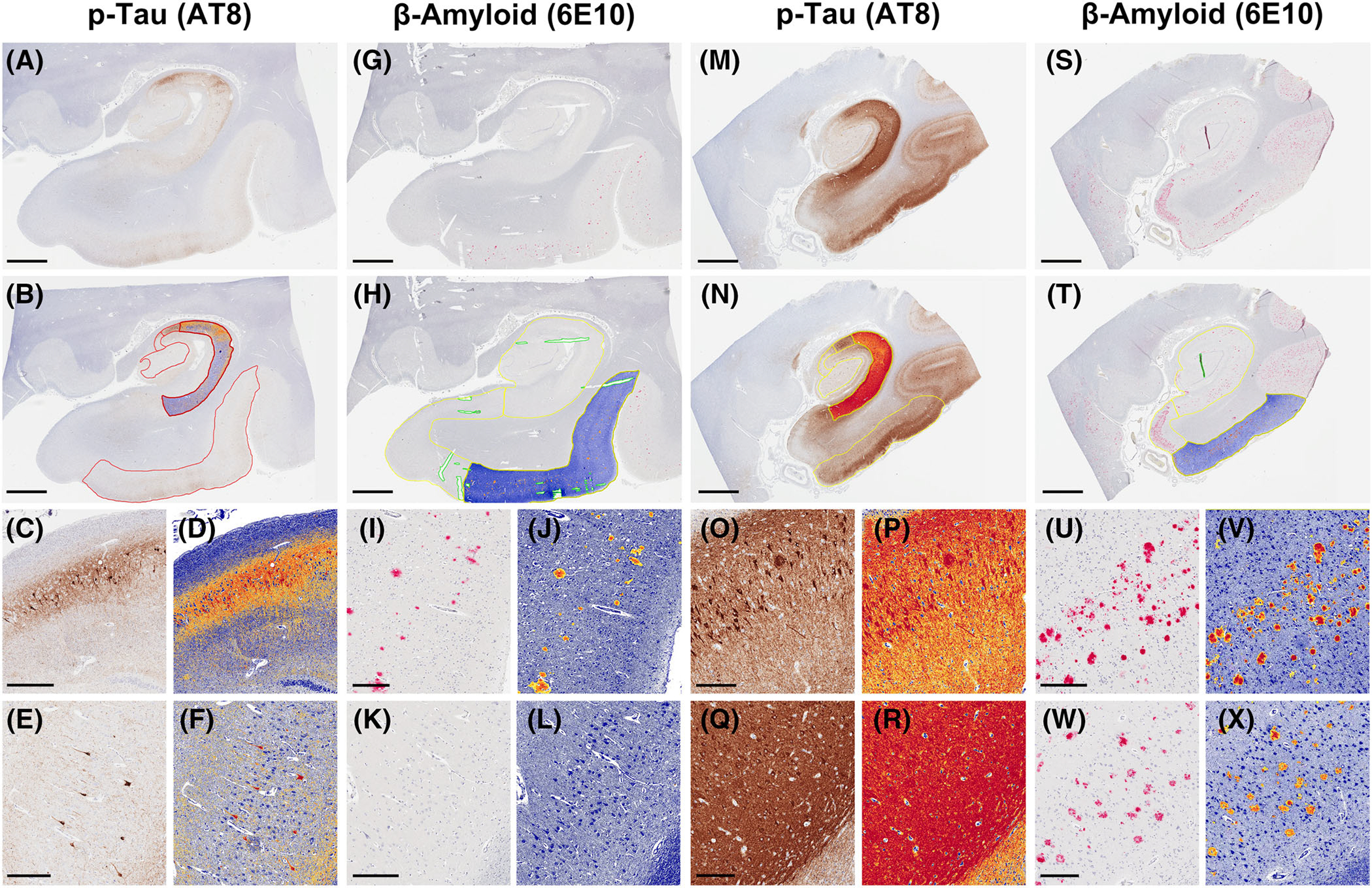

Segmentation of hippocampal subfields (entorhinal cortex, CA1/subiculum–CA4 subregions) was performed on scanned hippocampal sections, using Aperio ImageScope software.6,16 For p-tau analysis, CA2 was defined neuroanatomically with boundaries drawn at the most compact region of cornu ammonis neurons. CA4 was defined as the region enclosed by the dentate gyrus. CA3 was defined as the region between CA2 and CA4. CA1/subiculum was defined as the region between CA2 and the hippocampal fissure, and included stratum oriens to stratum moleculare (Figure 1A–F and M–R). For Aβ analysis, the hippocampus proper (subiculum, CA1–4, dentate gyrus) and adjacent entorhinal region were assessed as separate and combined regions (Figure 1G–L and S–X), as previously described.6 Defects in the sections (including artifacts such as tears and folds) and other features (including perivascular hemosiderin, iron, and calcifications) which may cause false positive or false negative positive pixel counts were excluded where possible using the Aperio ImageScope Negative Pen Tool (Figure 1H and Figure 1T).

FIGURE 1.

Demonstration of neuroanatomical segmentation and quantification of hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) and amyloid beta (Aβ) immunopositive pixels in Aβ negative (primary age-related tauopathy–like) and positive (AD neuropathologic change–like) subjects. A-B, p-tau quantification in the first subject (CA1 subregion segmentation highlighted), showing high-power views of the CA2 (C-D) and CA1 (E-F) hippocampal subfields. G-H, Aβ quantification in the first subject (entorhinal cortex segmentation highlighted), showing high-power fields of the entorhinal cortex (I-J) and CA1 hippocampal subfield (K-L). M-N, p-tau quantification in the second subject (CA1 subregion segmentation highlighted), showing high-power views of the CA2 (O-P) and CA1 (Q-R) hippocampal subfields. S-T, Aβ quantification in the second subject (entorhinal cortex segmentation highlighted), showing high-power fields of the entorhinal cortex (U-V) and CA1 hippocampal subfield (W-X). Scale bars for (A-B), (G-H), (M-N), and (S-T) = 3 mm. Scale bars for (C-F), (O-P), (U-X) = 400 μm. Scale bars for (I-L) = 300 μm. Scale bars for (Q-R) = 500 μm

p-tau and Aβ burdens were determined using Aperio ImageScope positive pixel count (Version 9) using default parameters (intensity threshold for weak positive pixels [upper limit] = 220, intensity threshold for weak positive pixels [lower limit] = 175, intensity threshold for medium positive pixels [lower limit] = 100, intensity threshold for strong positive pixels [lower limit] = 0), and the same thresholds were used for each slide.6,16 In each measured region, the number of medium and strong positive pixels and total pixels were recorded and used to create a ratio from 0 to 1 of positive pixels/total pixels of both p-tau and Aβ, termed the positive pixel percentage (PPP). For validation, we first performed these analyses on the positive control ADNC case run with each staining batch to ensure consistency.6,16 Pairs plotting was performed in R using the ggplot2 and GGally packages.

2.4 |. Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 9 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Correlations among Aβ burden, Thal phase, Braak stage, age, and p-tau levels and ratios were made using linear regression modelling using Pearson correlation coefficient. Comparisons between diagnostic groups (i.e., Aβ burden and CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio in ADNC vs. PART) were performed using Student’s t test. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Interaction between hippocampal Aβ burden and p-tau burden and distribution

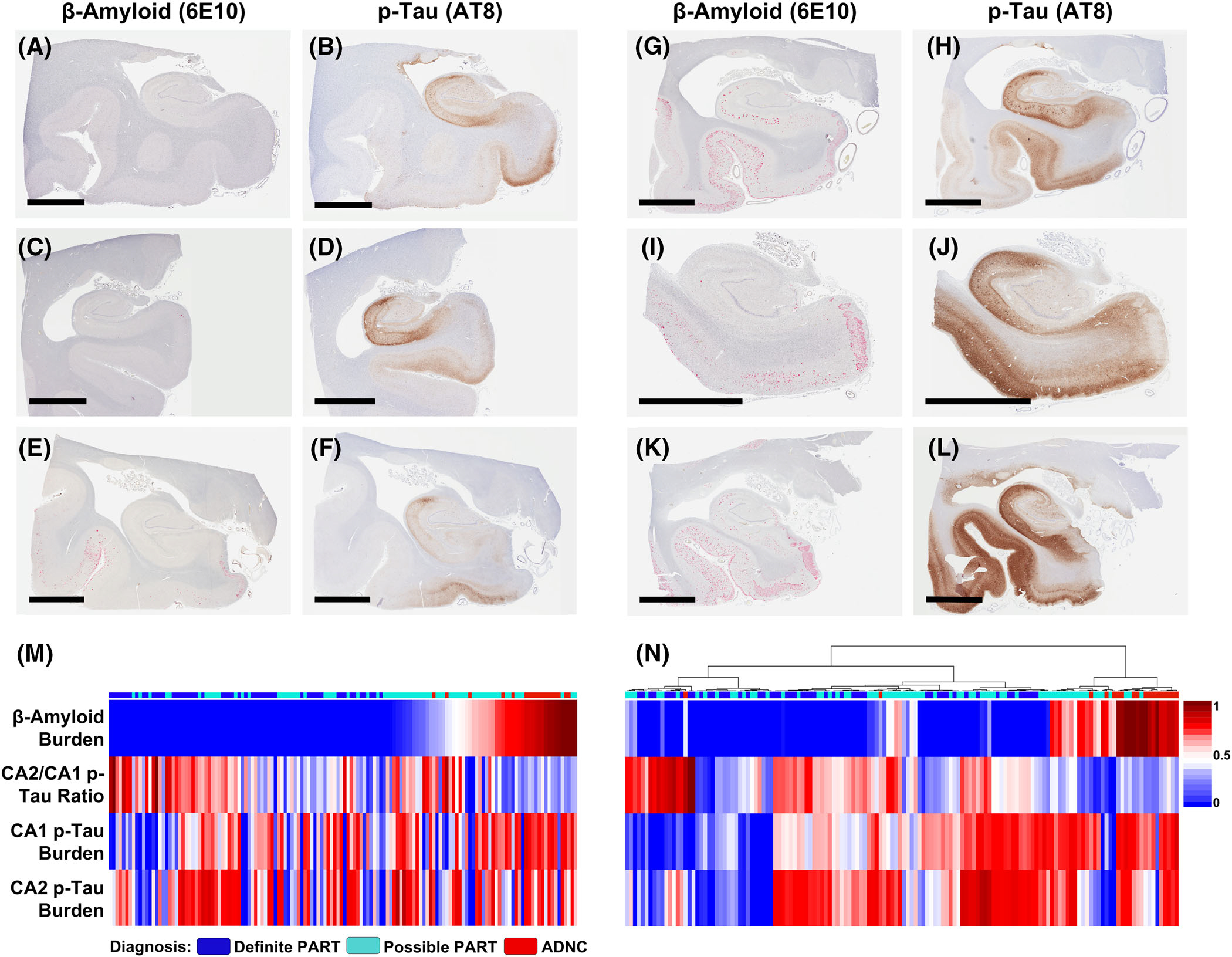

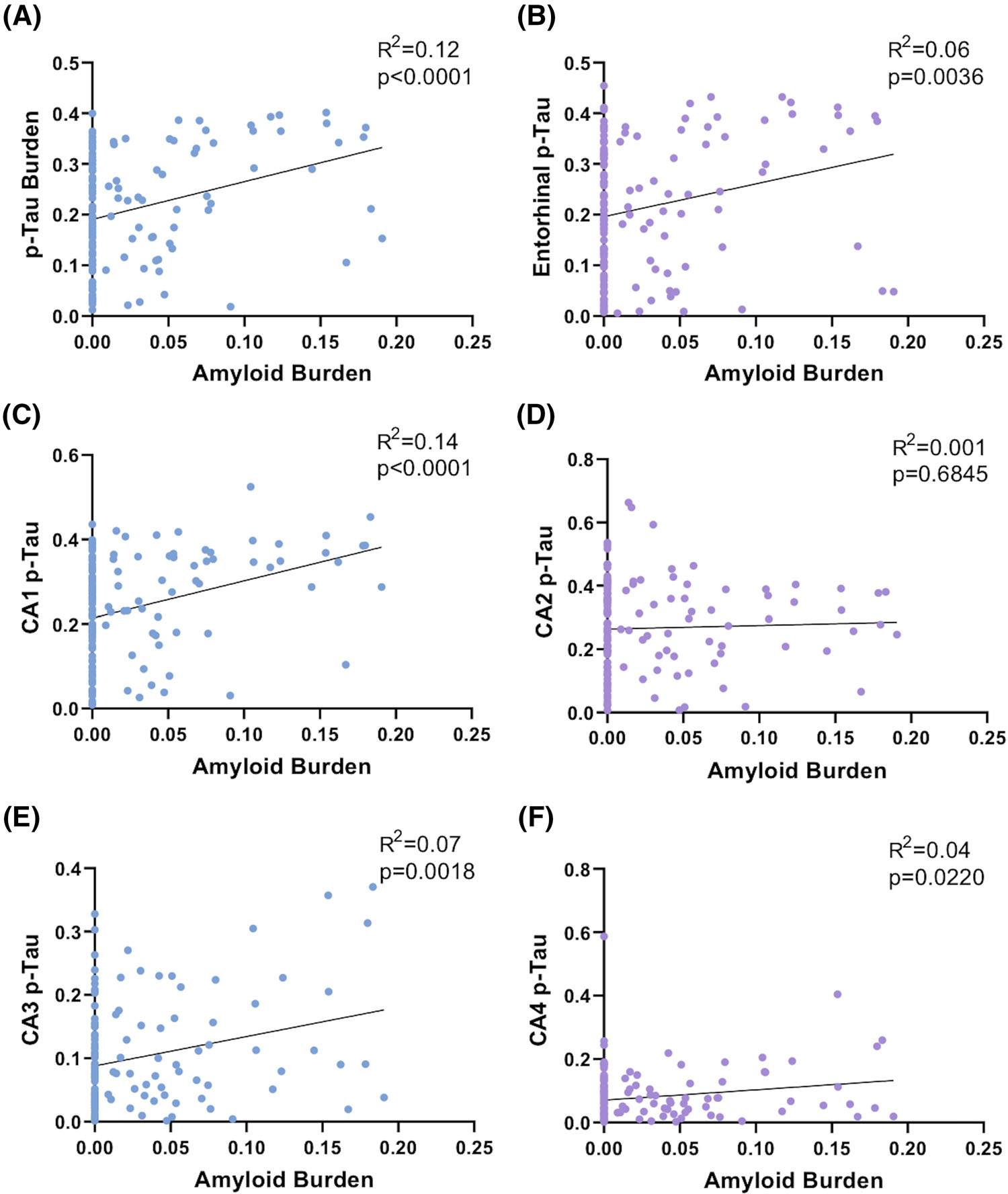

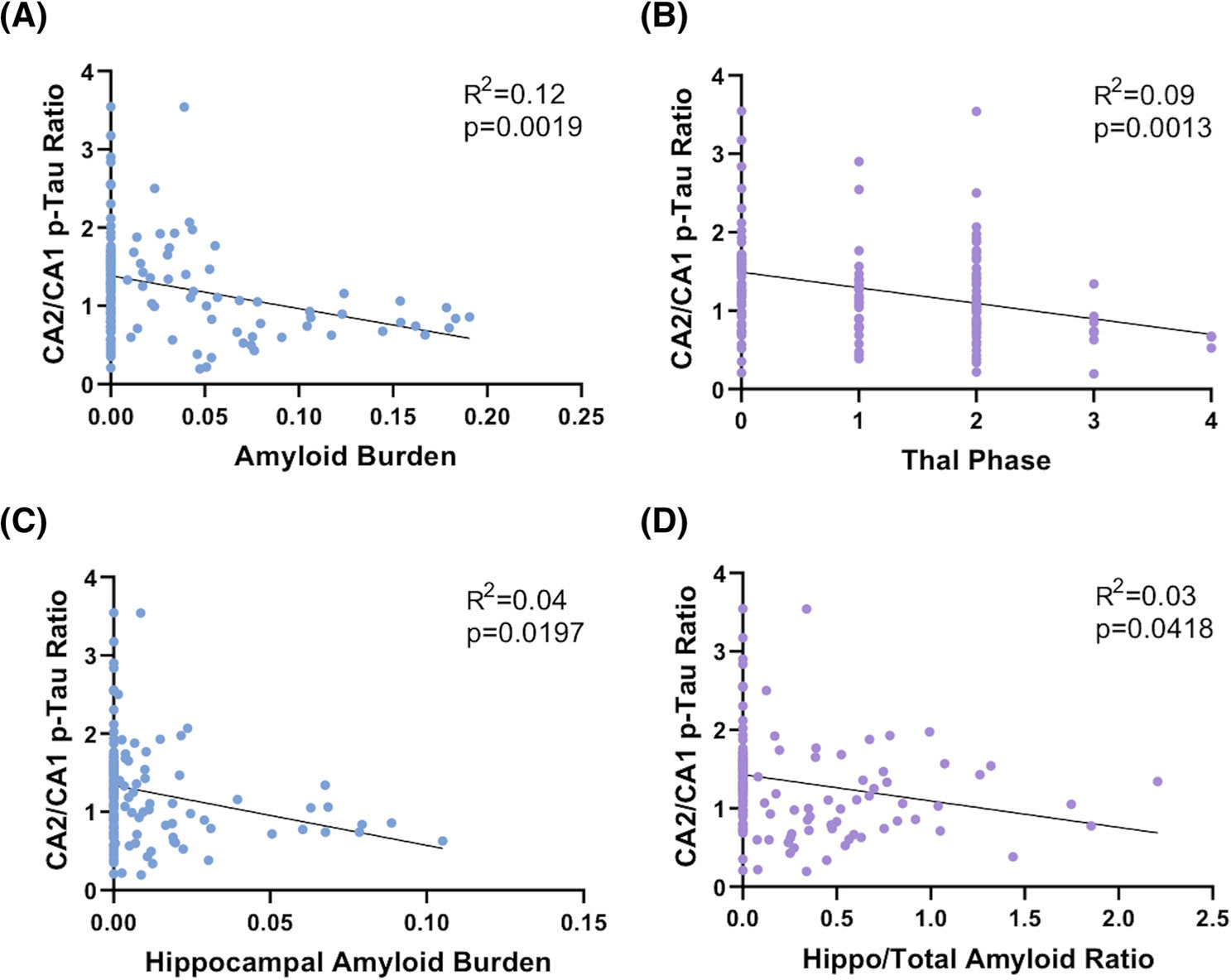

In cases with greater hippocampal Aβ burden (determined by PPP of the combined hippocampus proper and entorhinal region), the overall hippocampal p-tau burden (determined by PPP of the combined hippocampus proper and entorhinal region) was significantly higher (Pearson’s r = 0.35; P < 0.0001; Figure 2A–L and Figure 3A). In addition, the p-tau burden was positively correlated with Aβ burden in the entorhinal region (r = 0.24; P = 0.0036) and the CA1 (r = 0.37; P < 0.0001), CA3 (r = 0.26; P = 0.0018), and CA4 (r = 0.20; P = 0.0220) hippocampal subfields, but not the CA2 hippocampal subfield (r = 0.03; P = 0.6845; Figure 3B–F). The CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio was significantly lower with increasing Aβ burden (r = −0.35; P = 0.0019; Figure 2M–N and Figure 4A) as well as with increasing Thal phase (r = −0.30; P = 0.0013; Figure 4B). The CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio was also inversely correlated with the Aβ burden in the hippocampus proper (r = −0.20; P = 0.0197; Figure 4C), as well as the hippocampus proper/combined hippocampus proper and entorhinal Aβ ratio (r = −0.17; P = 0.0418; Figure 4D). These data suggest that the p-tau burden and the spatial distribution of p-tau within the hippocampus are related to both the overall level of Aβ present, as well as the progression of amyloid from neocortex (Thal phase 1) to entorhinal cortex to hippocampus proper. The overall p-tau burden significantly increased with patient age (r = 0.28; P = 0.0025); however, the CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio was not significantly correlated with age (r = −0.04; P = 0.6767; Figure S1 in supporting information).

FIGURE 2.

Paired images of hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) and amyloid beta (Aβ) immunohistochemical stains from six representative cases: 3 primary age-related tauopathy–like with minimal Aβ deposition (A-F) and 3 AD neuropathologic change–like with greater Aβ deposition (G-L), illustrating a trend toward higher overall hippocampal p-tau burden and lower CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio with higher Aβ burden. Scale bar in all panels = 6 mm. Heatmaps demonstrating the CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio, as well as CA1 and CA2 p-tau burdens in relation to Aβ burden in individual cases (M) ranked by Aβ burden and (N) ranked by hierarchical clustering using a Euclidian distance metric. Note: all measured values were normalized to fit a 0–1 scale by dividing each value by the highest value to allow for heatmap comparison

FIGURE 3.

Hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) burden in each hippocampal subregion except CA2 correlates with hippocampal amyloid beta (Aβ) burden. Linear correlation between hippocampal Aβ burden and (A) overall hippocampal p-tau burden, (B) entorhinal p-tau burden, (C) CA1 p-tau burden, (D) CA2 p-tau burden, (E) CA3 p-tau burden, and (F) CA4 p-tau burden

FIGURE 4.

The CA2/CA1 hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) ratio is inversely correlated with amyloid beta (Aβ) deposition. Correlation of CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio with (A) Aβ burden in the overall combined hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, (B) Thal phase, (C) Aβ burden in the hippocampus proper only (excluding entorhinal cortex), and (D) hippocampal/total Aβ ratio

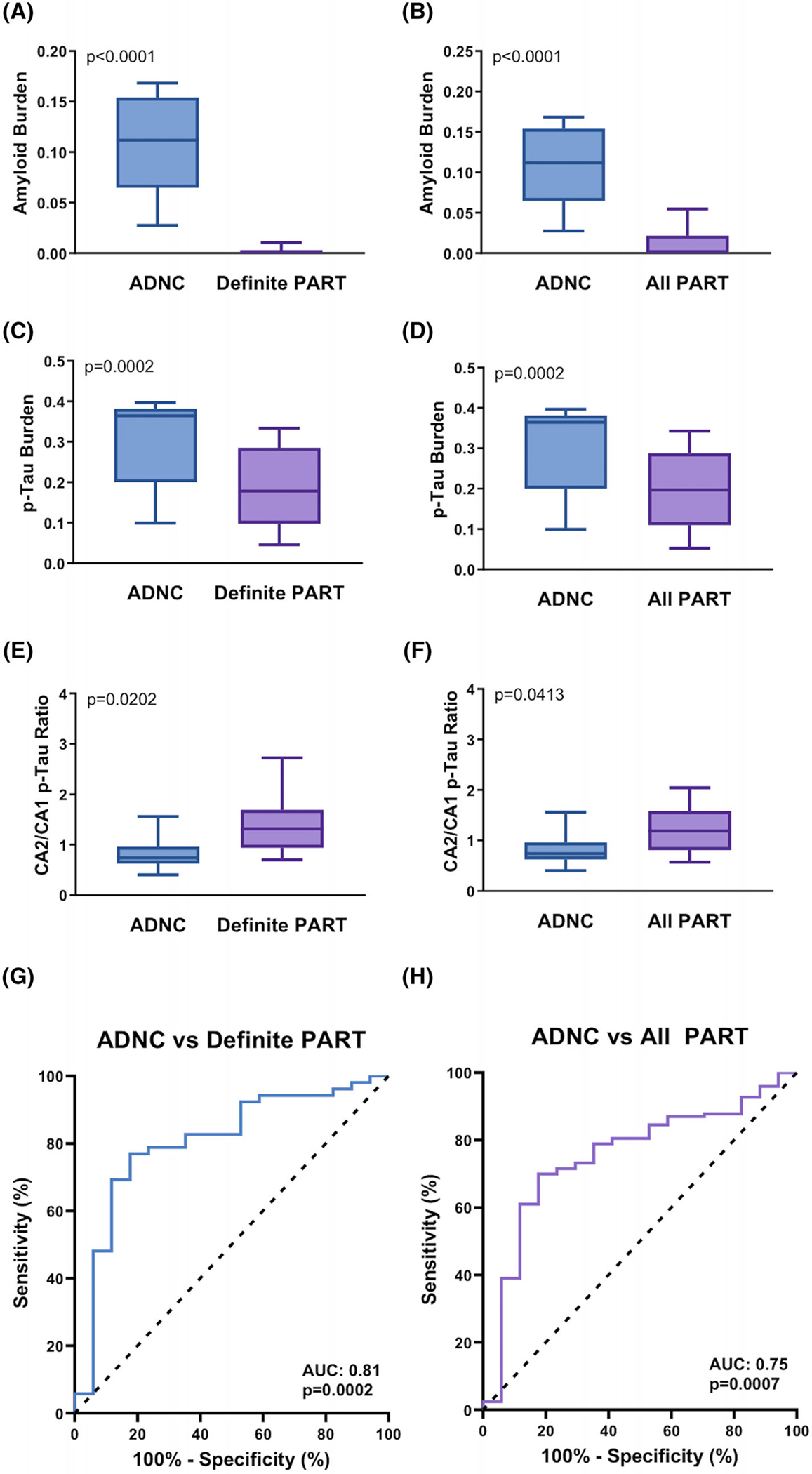

Cases that qualified as ADNC based on a combination of Braak stage, Thal phase, and CERAD NP score5 had no significant difference in age compared to definite PART (90.3 ± 2.0 vs. 88.3 ± 1.5; P = 0.4523) and combined definite and possible PART (89.5 ± 1.0; P = 0.7620). ADNC cases had significantly higher Aβ burden compared to cases that qualified as definite PART (0.11 ± 0.01 vs. 0.004 ± 0.001 PPP; P < 0.0001) and combined definite and possible PART (0.02 ± 0.003 PPP; P < 0.0001; Figure 5A–B), as well as significantly higher overall p-tau burden compared to definite PART (0.30 ± 0.03 vs. 0.19 ± 0.01 PPP; P = 0.0002) and combined definite and possible PART (0.20 ± 0.01 PPP; P = 0.0002; Figure 5C–D). ADNC cases had a significantly higher CA1 p-tau burden compared to definite PART (0.30 ± 0.03 vs. 0.19 ± 0.02 PPP; P = 0.0024) and combined definite and possible PART (0.23 ± 0.01 PPP; P = 0.0251), but did not differ in terms of CA2 p-tau burden compared to definite PART (0.25 ± 0.03 vs. 0.26 ± 0.02 PPP; P = 0.8721) or combined definite and possible PART (0.27 ± 0.01 PPP; P = 0.6046). ADNC cases had a significantly lower CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio compared to definite PART (0.92 ± 0.16 vs. 1.45 ± 0.12 PPP; P = 0.0202) and combined definite and possible PART (1.33 ± 0.07 PPP; P = 0.0413; Figure 5E–F). In addition, ADNC cases had a significantly lower CA2/entorhinal p-tau ratio compared to definite PART (0.84 ± 0.15 vs. 1.87 ± 0.26 PPP; P = 0.0288), although there was only a non-significant trend toward this compared to combined definite and possible PART (P = 0.1433).

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of amyloid beta (Aβ) and hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) burden in Alzheimer’s disease neuropathologic change (ADNC) and primary age-related tauopathy (PART) cases. ADNC versus definite PART and all PART cases in terms of (A-B) overall Aβ burden, (C-D) overall p-tau burden, and (E-F) CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio. Receiver operating characteristic curves demonstrating the predictive value of CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio in discriminating between (G) ADNC and definite PART and (H) ADNC and combined definite and possible PART (all PART)

Only 3 cases that met criteria for ADNC had a CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio greater than 1 (16%), compared to 37 cases of definite PART (69%; P = 0.0002) and 80 cases of combined definite and possible PART (65%; P < 0.0001). In addition, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves demonstrated that the CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio discriminates between ADNC and definite PART (area under the curve [AUC] = 0.81; P = 0.0002; Figure 5G) and combined definite and possible PART (all PART; AUC = 0.75; P = 0.0007; Figure 5H). Pairs plot of Aβ and subregional p-tau burdens demonstrated separate peaks between ADNC and definite/possible PART cases in terms of Aβ burden, overall p-tau burden, entorhinal p-tau burden, and CA1 p-tau burden, while CA2 p-tau burden has overlapping peaks, suggesting two separate histomorphologic entities within this overall cohort. Similar findings were observed between Aβ-positive and Aβ-negative cases (Figure S2 in supporting information).

3.2 |. Comparison of semiquantitative and quantitative methods

To compare the Aperio ImageScope-generated quantitative measurements against previously established semiquantitative measurements, we established a direct correlation between Thal phase and overall Aβ burden PPP (r = 0.69; P < 0.0001; Figure S3A in supporting information), Braak stage and overall p-tau burden PPP (r = 0.57; P < 0.0001; Figure S3B), and CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio (determined by previous semiquantitative scoring systems7,21) and quantitative CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio (r = 0.64; P < 0.0001; Figure S3C), confirming the validity of both techniques. These data also suggest, however, that there is a great deal of variation in hippocampal Aβ burden in Thal phase 2 and p-tau burden in Braak stages III and IV, suggesting that the quantitative measures may be better at capturing the full extent of hippocampal pathology than more topographical measurements such as Thal phase and Braak stage (Figure S3A–B).

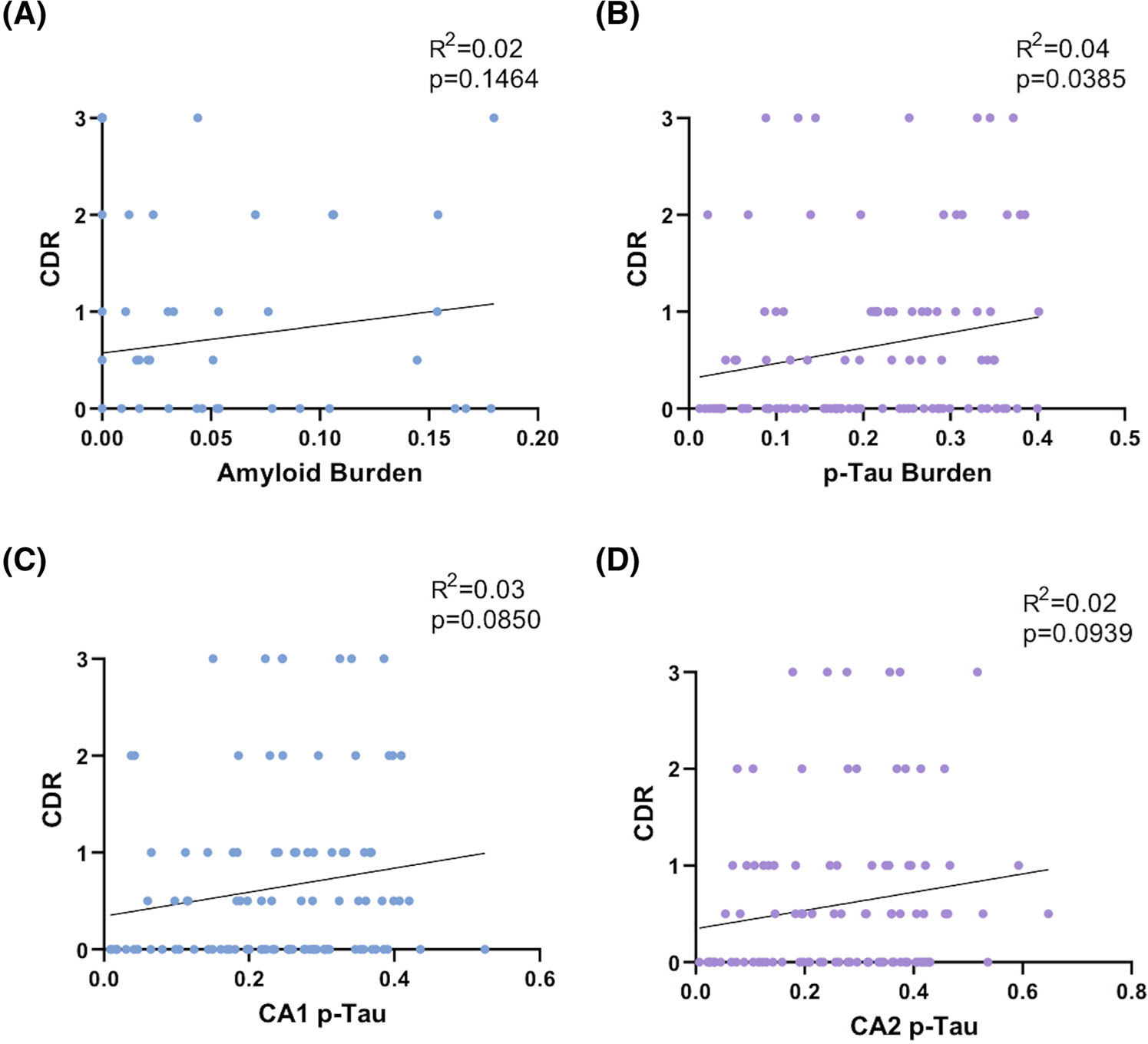

3.3 |. Clinical correlations

Clinical data in the form of CDR Global Scores were available for 98 of the subjects included in this study. There was a non-specific trend toward increasing CDR with increasing hippocampus proper/entorhinal cortex Aβ ratio and overall Aβ burden (r = 0.14; P = 0.1464; Figure 6A). CDR was significantly correlated with the overall p-tau burden (r = 0.20; P = 0.0385) (Figure 6B), but not CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio (r = 0.14; P = 0.3082), CA1 p-tau burden (r = 0.17; P = 0.0850; Figure 6C), or CA2 p-tau burden (r = 0.14; P = 0.0939; Figure 6D). There was also a significant direct correlation between patient age at death and CDR (r = 0.26; P = 0.0060), although this may be related to the direct correlation between age and overall p-tau burden (Figure S1) or the tendency to accumulate additional comorbidities with increasing age.22,23 No significant correlations were found among p-tau, Aβ, or CDR in terms of APOE allele status or MAPT haplotype within this dataset.

FIGURE 6.

Clinical and quantitative pathology comparisons. A, Amyloid burden and Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR), (B) overall hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) burden and CDR, (C) CA1 p-tau burden and CDR, and (D) CA2 p-tau burden and CDR, demonstrating a significant correlation only between CDR and overall p-tau burden

4 |. DISCUSSION

PART is a Aβ-independent tauopathy with different clinical,24–27 radiographic,28,29 morphologic,7–9 and genetic12,13,17,27 profiles compared to ADNC, although there remains controversy over the exact relationship between these two processes.14,15 Neurofibrillary degeneration in ADNC progresses almost invariably from the medial temporal lobe to the neocortex in stereotypical Braak stages,3 while the Aβ deposition begins in the neocortex and progresses through the limbic system and into the brainstem and cerebellum,4 often initially coexisting in the same space at the level of the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus, although recent imaging data suggests that there may be multiple distinct potential patterns of p-tau progression through the brain, complicating our understanding of this process.30 In contrast, while PART may exist in the presence of minimal Aβ deposition,7,8 the neurofibrillary degeneration is thought to be a Aβ-independent process, and generally does not progress past the medial temporal lobe (Braak I–IV).7,8,31 Within the hippocampus, morphological differences have been noted between the two processes as well. ADNC tends to affect the entorhinal cortex and CA1 hippocampal subfields initially, while PART frequently displays early neurofibrillary degeneration in the CA2 subfield with less severe entorhinal and CA1 p-tau deposition.7,9,21 Clinically, it is unclear if PART pathology alone correlates with significant cognitive symptoms. In PART cohorts, cognitive impairment does not appear to be related to Braak stage (as it is in AD), but appears to be affected primarily by the overall p-tau burden in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex (Figure 6) as well as other comorbidities, including hippocampal atrophy, cerebrovascular disease, white matter abnormalities, the presence of aging-related tau astrogliopathy, and the degree of limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy neuropathologic change.6,7,18,32 Furthermore, there is evidence that the hippocampal pathology in PART and early AD may develop asymmetrically in some individuals, which may provide a source of cognitive reserve.21 In addition, anterior temporal lobe atrophy in neuropathologically confirmed PART cases negatively correlated with performance on the Boston Naming Test, suggesting there may be clinical deficits in PART related to confrontational word retrieval.28 Although the exact function of the hippocampal CA2 subregion is not known, it has been proposed to be involved in social memory33 and encoding face–name pairs.34

In addition to the early involvement of the CA2 hippocampal subregion and the general absence of Aβ deposition in PART, we previously noted that there was an inverse relationship between the semiquantitatively measured CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio and Thal phase, and that Thal phase 3 cases with CERAD NP scores of “absent” had significantly higher CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio than subjects with CERAD NP scores of “sparse” to “frequent,”7 suggesting that there is a relationship between the Aβ burden and the hippocampal distribution pattern of p-tau. Here, we used image analysis to quantitatively measure the level of Aβ and p-tau in the entorhinal cortex and hippocampal subfields to further explore the interaction between the two aggregated proteins at the level of the hippocampus. These data indicate that the level of Aβ is significantly correlated to the level of p-tau in the entorhinal cortex and all of the individual hippocampal subfields except CA2 (Figure 3), and the CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio is inversely correlated with the Aβ burden (Figure 4A). The quantitatively assessed CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio is also inversely correlated with Thal phase, Aβ burden in the hippocampus proper (excluding the entorhinal cortex), and the Aβ hippocampus proper/combined hippocampus proper and entorhinal cortex ratio (Figure 4B–D). This suggests that the presence of Aβ at the level of the hippocampus may in part be responsible for the distribution pattern of p-tau, and that the amount and location of Aβ influences the deposition of p-tau. Subjects with greater Aβ burden and Aβ progression from the entorhinal cortex into the hippocampal proper (AD-like) are more likely to have higher entorhinal and CA1 p-tau deposition compared to CA2 (in an AD-type distribution), whereas subjects with absent or more restricted Aβ burden (PART-like) are more likely to have a higher CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio (Figure 2). Further evidence for Aβ burden influencing the vulnerability of CA2 comes from the fact that Aβ-independent 4R-tauopathies, such as progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration, tend to preferentially affect CA2.35

An alternative explanation to the concept that Aβ burden in the medial temporal lobe dictates the regional spread of neurofibrillary degeneration in the hippocampus is that the specific spatial deposition of p-tau may dictate the amount and location of Aβ plaques (i.e., early deposition of CA2 p-tau is somehow “protective” against Aβ deposition). In either scenario, there is a strong correlation between the Aβ plaque burden and the neurofibrillary degeneration burden and pattern, suggesting that these two proteins may initially interact with one another within the medial temporal lobe. Interestingly, we have shown previously that proteins specifically related to Aβ processing are upregulated in neurofibrillary tangle (NFT)-bearing neurons of symptomatic AD patients, but not in normal non–NFT-bearing neurons in the same patients, or NFT-bearing neurons of resilient, cognitively intact individuals, and the microenvironments surrounding NFT-bearing neurons in subjects with dementia have higher levels of proteins related to inflammation and lower levels of proteins associated with healthy synapses.36 This suggests that the interaction between Aβ and p-tau may play some role in the development of overall hippocampal pathology as well as cognitive symptoms,37 although only overall p-tau burden was found to have a significant effect on cognition in the study cohort (Figure 6).

Imaging studies have found an association between regional Aβ accumulation and p-tau aggregation.38,39 The working model is that extracellular Aβ plaques increase neuronal excitability, triggering tau hyperphosphorylation and dissociation from microtubules, secreted as soluble p-tau, which is thought to “seed” other neurons leading to NFT accumulation. It is unclear how definite PART would fit within this model as it does not display Aβ accumulation, yet still harbors NFTs, unless PART and AD have different mechanisms for p-tau accumulation.

It has also been suggested that PART may simply represent an early step in the spectrum of AD with p-tau–predominant features, or a stage of AD before significant Aβ has yet been deposited, and with time these individuals would develop Aβ plaques and have a decreasing CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio.14 This is unlikely, given that PART patients have numerous diverging patterns from AD,7,8,15 there is no age difference between subjects diagnosed as definite or possible PART and ADNC in this cohort, and the CA2/CA1 ratio does not decrease (become more “ADNC-like”) with increasing patient age. Moreover, PART subjects are often older than subjects with clinical and pathological evidence of AD (representing the “oldest old”),suggesting that these individuals will likely never develop into ADNC.15,40 PART patients in this study with relatively high CA1 p-tau burden (or overall p-tau burden) and/or higher Global CDR often still maintain a CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio > 1 and lack significant hippocampal Aβ deposition, arguing for the existence of a discrete neuropathologic pattern associated with PART and against the idea that these individuals are simply in the process of developing ADNC. In addition, patients with relatively high hippocampal Aβ burden compared to their p-tau burden (“early AD” or pre-clinical AD patients) also have preferential entorhinal and CA1 neurofibrillary degeneration instead of early CA2 p-tau deposition, again suggesting two distinct patterns between PART and AD populations.

In summary, these data demonstrate that there is a significant relationship between hippocampal Aβ and p-tau deposition, where both the amount of Aβ pathology and the location of Aβ plaques appear to affect the overall severity and distribution of neurofibrillary degeneration within individual hippocampal subregions. These patterns differ between cases with ADNC and cases with definite or possible PART. Within the context of previous data, these findings suggest that there may be an interaction between Aβ and p-tau that could ultimately influence cognitive outcome.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Subregional hyperphosphorylated-tau (p-tau) distribution is influenced by hippocampal amyloid beta burden.

Higher CA2/CA1 p-tau ratio is predictive of primary age-related tauopathy–like neuropathology.

Cognitive function is correlated with the overall hippocampal p-tau burden.

RESEARCHINCONTEXT.

1. Systematic Review:

The authors reviewed the literature using online journal sources. The distribution of neurofibrillary degeneration and amyloid beta (Aβ) deposition in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have been studied thoroughly (Braak stages and Thal phases). However, how hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) distribution differs in relation to Aβ deposition has not. Relevant literature is appropriately cited.

2. Interpretation:

Although it is known that Aβ and tau interact and work synergistically in AD, it is unclear how or why. By studying primary age-related tauopathy and AD cases with varying degrees of Aβ burden, we have demonstrated that the amount of hippocampal Aβ deposition may dictate regional neurofibrillary degeneration distribution.

3. Future Directions:

This article describes the development of AD-type pathologic changes, as well as what normal aging may look like in comparison, which could be translated to imaging studies and used for diagnostic purposes, in addition to histopathologic analysis of Aβ and tau in additional brain regions and spatial multiomic studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express our deepest gratitude to the patients and staff of the contributing centers and institutes. Additionally, the authors would like to thank The Neuropathology Brain Bank & Research CoRE at Mount Sinai, as well as Ping Shang, Jeff Harris, and Chan Foong of the UT Southwestern Neuropathology Laboratories.

The PART working group: Ann C. McKee (Department of Pathology, Alzheimer’s Disease and CTE Center, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA), Victor E. Alvarez (Department of Pathology, Alzheimer’s Disease and CTE Center, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA), Thor D. Stein (Department of Pathology, Alzheimer’s Disease and CTE Center, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA), Jean-Paul Vonsattel (Department of Pathology and Cell Biology, Department of Neurology, and the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s Disease and the Aging Brain, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY), Andrew F. Teich (Department of Pathology and Cell Biology, Department of Neurology, and the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s Disease and the Aging Brain, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY), Marla Gearing (Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine [Neuropathology] and Neurology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA), Jonathan Glass (Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine [Neuropathology] and Neurology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA), Juan C. Troncoso (Department of Pathology, Division of Neuropathology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD), Matthew P. Frosch (Department of Neurology and Pathology, Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA), Bradley T. Hyman (Department of Neurology and Pathology, Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA), Dennis W. Dickson (Departments of Pathology and Neuroscience, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL), Melissa E. Murray (Department of Neuroscience, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL), Johannes Attems (Translational and Clinical Research Institute, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK), Margaret E. Flanagan (Department of Pathology [Neuropathology], Northwestern Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer Disease Center, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL), Qinwen Mao (Department of Pathology [Neuropathology], Northwestern Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer Disease Center, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL), M-Marsel Mesulam (Department of Pathology [Neuropathology], Northwestern Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer Disease Center, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL), Sandra Weintraub (Department of Pathology [Neuropathology], Northwestern Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer Disease Center, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL), Randy L. Woltjer (Department of Pathology, Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland, OR), Thao Pham (Department of Pathology, Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland, OR), Julia Kofler (Department of Pathology [Neuropathology], University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA), Julie A. Schneider (Departments of Pathology [Neuropathology] and Neurological Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL), Lei Yu (Departments of Pathology [Neuropathology] and Neurological Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL), Dushyant P. Purohit (Department of Pathology, Neuropathology Brain Bank and Research CoRE, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, James J. Peters VA Medical Center, New York, NY), Vahram Haroutunian (Department of Psychiatry, Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, James J. Peters VA Medical Center, Nash Family Department of Neuroscience, Ronald M. Loeb Center for Alzheimer’s Disease, Friedman Brain Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY), Patrick R. Hof (Nash Family Department of Neuroscience, Ronald M. Loeb Center for Alzheimer’s Disease, Friedman Brain Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY), Sam Gandy (Department of Psychiatry, Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, and Department of Neurology, Mount Sinai Center for Cognitive Health, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and James J. Peters VA Medical Center, New York, NY), Mary Sano (Department of Psychiatry, Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, James J. Peters VA Medical Center, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY), Thomas G. Beach (Department of Neuropathology, Banner Sun Health Research Institute, Sun City, AZ), Wayne W. Poon (Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders, UC Irvine, Irvine, CA), Claudia H. Kawas (Department of Neurology, Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders, UC Irvine, Irvine, CA), Marıa M. Corrada (Department of Neurology, Department of Epidemiology, Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders, UC Irvine, Irvine, CA), Robert A. Rissman (Department of Neurosciences University of California and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, La Jolla, San Diego, CA), Jeff Metcalf (Department of Neurosciences University of California and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, La Jolla, San Diego, CA), Sara Shuldberg (Department of Neurosciences University of California and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, La Jolla, San Diego, CA), Bahar Salehi (Department of Neurosciences University of California and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, La Jolla, San Diego, CA), Peter T. Nelson (Department of Pathology [Neuropathology] and Sanders-Brown Center on Aging, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY), John Q. Trojanowski (Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA), Edward B. Lee (Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA), David A. Wolk (Department of Neurology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA), Corey T. McMillan (Department of Neurology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA), C. Dirk Keene (Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Medicine, Seattle, WA), Caitlin S. Latimer (Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Medicine, Seattle, WA), Thomas J. Montine (Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Medicine, Seattle, WA and Department of Pathology, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA), Gabor G. Kovacs (Laboratory Medicine Program, Krembil Brain Institute, University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada; Tanz Centre for Research in Neurodegenerative Disease and Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; and Institute of Neurology, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria), Mirjam I. Lutz (Institute of Neurology, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria), Peter Fischer (Department of Psychiatry, Danube Hospital, Vienna, Austria), Richard J. Perrin (Department of Pathology and Immunology, Department of Neurology, Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO), Nigel J. Cairns (Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, University of Exeter, Devon, UK), Ping Shang (Department of Pathology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center), Jeff Harris (Department of Pathology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center), and Chan Foong (Department of Pathology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center).

J.M.W. and T.E.R. are supported in part by National Institute on Aging (NIA) R21 AG078505 and Texas Alzheimer’s Research and Care Consortium (TARCC) grants 957581 and 957607. K.F. is supported in part by K01 AG070326. C.H.K., M.M.C., and W.W.P. (University of California, Irvine) are supported in part by R01 AG021055 and P30 AG066519. D.A.W., E.B.L., and C.T.M. (University of Pennsylvania) are supported by P30 AG072979. J.K. (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center) is supported by P30 AG066468. R.J.P. and the Knight ADRC (Washington University School of Medicine) are supported by P01 AG003991 (Healthy Aging and Senile Dementia), P30 AG066444 (Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center), and P01 AG026276 (Adult Children Study). We are grateful to the Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program of Sun City, Arizona for the provision of human biological materials. The Brain and Body Donation Program has been supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS072026 National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders), the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610 and P30 AG072980, Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimer’s Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05–901, and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium), and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Funding information

National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Number: R21 AG078505; Texas Alzheimer’s Research and Care Consortium, Grant/Award Numbers: 957581, 957607

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part. The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Author disclosures are available in the supporting information.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

SUPPORTIN GINFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Braak H, Del Tredici K. The pathological process underlying alzheimer’s disease in individuals under thirty. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braak H, Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Del Tredici K. Stages of the pathologic process in alzheimer disease: age categories from 1 to 100 years. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011;70:960–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thal DR, Rub U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology. 2002;58:1791–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National institute on aging-alzheimer’s association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iida MA, Farrell K, Walker JM, et al. Predictors of cognitive impairment in primary age-related tauopathy: an autopsy study. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2021;9:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker JM, Richardson TE, Farrell K, et al. Early Selective Vulnerability of the CA2 hippocampal subfield in primary age-related tauopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2021;80:102–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crary JF, Trojanowski JQ, Schneider JA, et al. Primary age-related tauopathy (PART): a common pathology associated with human aging. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128:755–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jellinger KA. Different patterns of hippocampal tau pathology in alzheimer’s disease and PART. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136:811–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iseki E, Tsunoda S, Suzuki K, et al. Regional quantitative analysis of NFT in brains of non-demented elderly persons: comparisons with findings in brains of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease and limbic NFT dementia. Neuropathology. 2002;22:34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takayama N, Iseki E, Yamamoto T, Kosaka K. Regional quantitative study of formation process of neurofibrillary tangles in the hippocampus of non-demented elderly brains: comparison with late-onset alzheimer’s disease brains. Neuropathology. 2002;22:147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson AC, Davidson YS, Roncaroli F, et al. Influence of APOE genotype in primary age-related tauopathy. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2020;8:215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santa-Maria I, Haggiagi A, Liu X, et al. The MAPT H1 haplotype is associated with tangle-predominant dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:693–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duyckaerts C, Braak H, Brion JP, et al. PART is part of Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:749–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jellinger KA, Alafuzoff I, Attems J, et al. PART, a distinct tauopathy, different from classical sporadic Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:757–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farrell K, Iida MA, Cherry JD, et al. Differential vulnerability of hippocampal subfields in primary age-related tauopathy and chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farrell K, Kim S, Han N, et al. Genome-wide association study and functional validation implicates JADE1 in tauopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2022;143:33–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKenzie AT, Marx GA, Koenigsberg D, et al. Interpretable deep learning of myelin histopathology in age-related cognitive impairment. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2022;10:131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marx GA, Koenigsberg DG, McKenzie AT, et al. Artificial intelligence-derived neurofibrillary tangle burden is associated with antemortem cognitive impairment. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2022;10:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duvernoy H, Cattin F, Risold PY. Sectional anatomy and magnetic resonance imaging. In: Duvernoy H, Cattin F, Risold PY, eds. The Human Hippocampus: Functional Anatomy, Vascularization and Serial Sections with MRI. Springer-Verlag; 2013:129. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker JM, Fudym Y, Farrell K, et al. Asymmetry of hippocampal tau pathology in primary age-related tauopathy and alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2021;80:436–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karanth S, Nelson PT, Katsumata Y, et al. Prevalence and clinical phenotype of quadruple misfolded proteins in older adults. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:1299–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rabinovici GD, Carrillo MC, Forman M, et al. Multiple comorbid neuropathologies in the setting of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology and implications for drug development. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2016;3:83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savola S, Kaivola K, Raunio A, et al. Primary age-related tauopathy in a Finnish population-based study of the oldest old (Vantaa 85+). Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2022;48:e12788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teylan M, Besser LM, Crary JF, et al. Clinical diagnoses among individuals with primary age-related tauopathy versus Alzheimer’s neuropathology. Lab Invest. 2019;99:1049–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teylan M, Mock C, Gauthreaux K, et al. Cognitive trajectory in mild cognitive impairment due to primary age-related tauopathy. Brain. 2020;143:611–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell WR, An Y, Kageyama Y, et al. Neuropathologic, genetic, and longitudinal cognitive profiles in primary age-related tauopathy (PART) and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15:8–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quintas-Neves M, Teylan MA, Morais-Ribeiro R, et al. Divergent magnetic resonance imaging atrophy patterns in Alzheimer’s disease and primary age-related tauopathy. Neurobiol Aging. 2022;117:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quintas-Neves M, Teylan MA, Besser L, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging brain atrophy assessment in primary age-related tauopathy (PART). Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019;7:204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vogel JW, Young AL, Oxtoby NP, et al. Four distinct trajectories of tau deposition identified in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2021;27:871–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker JM, White CL, Farrell K, Crary JF, Richardson TE. Neocortical Neurofibrillary Degeneration in Primary Age-Related Tauopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2022;81:146–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smirnov DS, Salmon DP, Galasko D, et al. TDP-43 Pathology Exacerbates Cognitive Decline in Primary Age-Related Tauopathy. Ann Neurol. 2022;92:425–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chevaleyre V, Piskorowski RA. Hippocampal Area CA2: an Overlooked but Promising Therapeutic Target. Trends Mol Med. 2016;22:645–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeineh MM, Engel SA, Thompson PM, Bookheimer SY. Dynamics of the hippocampus during encoding and retrieval of face-name pairs. Science. 2003;299:577–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishizawa T, Ko LW, Cookson N, Davias P, Espinoza M, Dickson DW. Selective neurofibrillary degeneration of the hippocampal CA2 sector is associated with four-repeat tauopathies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:1040–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker JM, Kazempour Dehkordi S, Fracassi A, et al. Differential protein expression in the hippocampi of resilient individuals identified by digital spatial profiling. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2022;10:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walker JM, Dehkordi SK, Schaffert J, et al. The Spectrum of Alzheimer-Type Pathology in Cognitively Normal Individuals. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leuzy A, Smith R, Cullen NC, et al. Biomarker-Based Prediction of Longitudinal Tau Positron Emission Tomography in Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79:149–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pichet Binette A, Franzmeier N, Spotorno N, et al. Amyloid-associated increases in soluble tau relate to tau aggregation rates and cognitive decline in early Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Commun. 2022;13:6635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crary JF. Primary age-related tauopathy and the amyloid cascade hypothesis: the exception that proves the rule. J Neurol Neuromedicine. 2016;1:53–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.