Summary

Antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) are generated following B cell activation and constitutively secrete antibodies. As such, ASCs are key mediators of humoral immunity whether it be in the context of pathogen exposure, vaccination or even homeostatic clearance of cellular debris. Therefore, understanding basic tenants of ASC biology such as their differentiation kinetics following B cell stimulation is of importance. Towards that aim, we developed a mouse model which expresses simian HBEGF (a.k.a., diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR)) under the control of the endogenous Jchain locus (or J-DTR). ASCs from these mice expressed high levels of cell surface DTR and were acutely depleted following diphtheria toxin treatment. Furthermore, proof-of-principle experiments demonstrated the ability to use these mice to track ASC reconstitution following depletion in 3 distinct organs. Overall, J-DTR mice provide a new and highly effective genetic tool allowing for the study of ASC biology in a wide range of potential applications.

Keywords: Antibody-secreting cells, plasmablasts, plasma cells, B cells, Jchain, HBEGF, diphtheria toxin receptor, diphtheria toxin, depletion

Introduction

Upon stimulation, B cells have the potential to differentiate into antibody-secreting cells (ASCs)1 which are most prominently known for their ability to secrete thousands of antibodies (Abs) per second2–4. In the context of a pathogenic infection or vaccination against a specific pathogen, these Abs provide a multitude of functions (e.g., neutralization)5 which serve to ameliorate a current infection or act as a prophylaxis to prevent a new infection from taking hold. Therefore, it is paramount to develop a better understanding of ASC biology. This includes not only how quickly these cells are produced following B cell stimulation but also how competitive these newly formed ASCs are when confronted with limited survival niches and the presence of pre-existing ASCs. Not surprisingly, both factors have the potential to dictate the durability of the humoral immune response and seemingly are not uniform across different types of B cell subsets and stimulatory cues6–8.

Multiple groups have developed genetic models to fluorescently timestamp ASCs which have led to new insights regarding ASC longevity as well as the developmental relationship between short-lived plasmablasts (PBs) and post-mitotic plasma cells (PCs)7,9–11. Many of these experiments have been performed in the context of a fully replete ASC compartment constraining the ability to assess ASC longevity in competitive versus non-competitive scenarios. While efforts have been made to subvert these issues, these experiments largely focused on the maintenance of pre-existing ASCs. Pre-existing ASCs are critically important as they can represent a decades long record of immunization and humoral protection. However, understanding how newly formed ASCs integrate into a long-lived protective reservoir is essential especially considering the recent COVID-19 pandemic and continual threat of newly emerging viruses. Along these lines, being able to assess ASC generation in the presence or absence of pre-existing ASCs could be extremely informative. Towards this goal, CD138 Abs have been shown to be useful in depleting ASCs in bone marrow (BM) of young and old mice12. CD138-diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) mice have also been generated and utilized in the context of Plasmodium infection13. However, these models have inherent limitations. For example, the CD138 Abs previously utilized to deplete ASCs are mouse anti-mouse Abs which are not commercially available and would require in house production12. Additionally, the differential level of Cd138 expression compared to other selected immune cell types is not particularly high11 suggesting a narrow window allowing for ASC depletion with limited off target effects. Recently, the BICREAD mouse strain was developed which incorporates both a Tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase and DTR within the Prdm1 locus7. While effective regarding ASC depletion, the use of Prdm1 to drive DTR expression presents complications given its role in regulating both CD4 and CD8 memory T cell formation14–16.

To provide a tool which would allow users to modulate the presence of pre-existing ASCs, we have generated a mouse model in which the simian HBEGF (a.k.a. DTR) cDNA from Chlorocebus sabaeus was inserted into the endogenous Jchain locus thus targeting DTR expression to ASCs (referred to here as J-DTR mice). We have shown that these mice are functional, and that ASCs can be acutely depleted following a single dose of diphtheria toxin (DT) in organs such as the spleen (SPL), BM and thymus (THY). Furthermore, due to the short half-life of DT17, we demonstrated the utility of this model in being able to assess ASC differentiation kinetics following depletion. At homeostasis, ASC populations were reconstituted to normal levels 7 days following DT injection supporting the concept that ASCs are continuously produced even in the absence of overt infection. Overall, the J-DTR mouse model is a highly effective tool that can be utilized to study ASC population dynamics.

Results

The generation of J-DTR mice and validation of DTR gene expression in ASCs

DT is derived from Corynebacterium diphtheria and acts as a potent protein synthesis inhibitor leading to cellular apoptosis18. Previous work demonstrated that DT enters the cell via receptor-mediated endocytosis following binding to the membrane bound pro-form of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF protein, encoded by the HBEGF gene)19,20. While species such as humans, simians and mice all express the HB-EGF protein, the mouse version of the protein possesses distinct amino acid differences making this species relatively insensitive to DT21. As such, mouse models have been developed in which human or simian HBEGF (referred to throughout as the DTR) expression is driven by cell type-specific genetic elements thus allowing for targeted ablation of that particular cell type22–24.

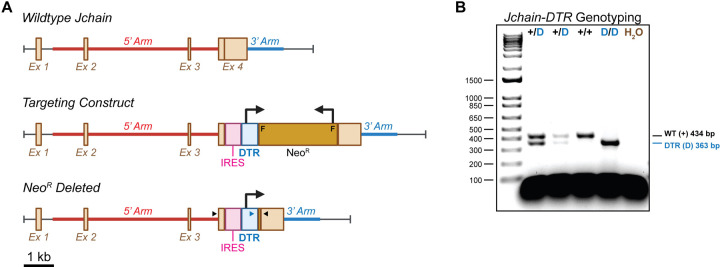

In considering an appropriate driver of DTR in ASCs, we examined the expression of various ASC-associated genes in the Immunological Genome Project database (ImmGen, https://www.immgen.org/) (Figures S1A–S1C). The ASC-associated transcription factor Prdm1 (BLIMP-1) and cell surface marker Sdc1 (CD138) were readily expressed by ASC subsets; however, this was not exclusive as both genes were found to be expressed in other cell types albeit as lower levels (Figure S1A). Recent work utilized the Jchain gene to drive a Tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase cassette in ASCs with a great deal of success11. Jchain expression was increased in ASC populations compared to both Prdm1 and Sdc1 upon examination of the ImmGen data (Figure S1B). Furthermore, Jchain expression appeared highly selective for ASCs when compared to all ImmGen cell types (Figure S1B) as well as those specifically in the B cell lineage (Figure S1C). Therefore, we generated a C57BL/6 mouse strain with the DTR cDNA from Chlorocebus sabaeus (a.k.a. African green monkey) knocked into the endogenous Jchain locus (Figure 1A). In this instance, DTR was inserted into the Jchain 3’ untranslated region (UTR) downstream of an internal ribosomal entry sight (IRES) (Figure 1A). Upon extraction of genomic DNA, both wildtype (WT) and DTR-inserted Jchain alleles were readily identifiable by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1: Construction and genotyping of J-DTR mice. Related to Figure S1.

(A) Schematic showing wildtype (WT) Jchain locus, the Targeting Construct and the final Jchain-DTR targeted insertion following Neomycin resistance (NeoR) cassette deletion by flippase (FLP). Schematic is drawn to approximate scale with scale bar indicating 1 kb. F = FRT sites used for FLP-mediated recombination, IRES = internal ribosomal entry site. 5’ and 3’ homology arms used to direct integration are shown. Large 90° bent arrows indicate direction of transcription for DTR and NeoR. Small arrow heads indicate approximate placement for genotyping primers. Black arrow heads bind DNA regions present in the endogenous Jchain gene. Blue arrowhead binds DNA sequence within the DTR coding region. Note that following NeoR deletion, a single FRT site is reconstituted. This site is omitted for clarity. (B) Representative Jchain-DTR genotyping results generated from PCR amplification of genomic DNA. Note that the 434 bp WT product is only observed in animals lacking the IRES-DTR insertion. Animals containing this insertion would generate a product approximating 1664 bp which is not amplified using the current PCR conditions. PCR products were electrophoresed in a 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. A 1 kb+ DNA ladder was utilized as a size standard.

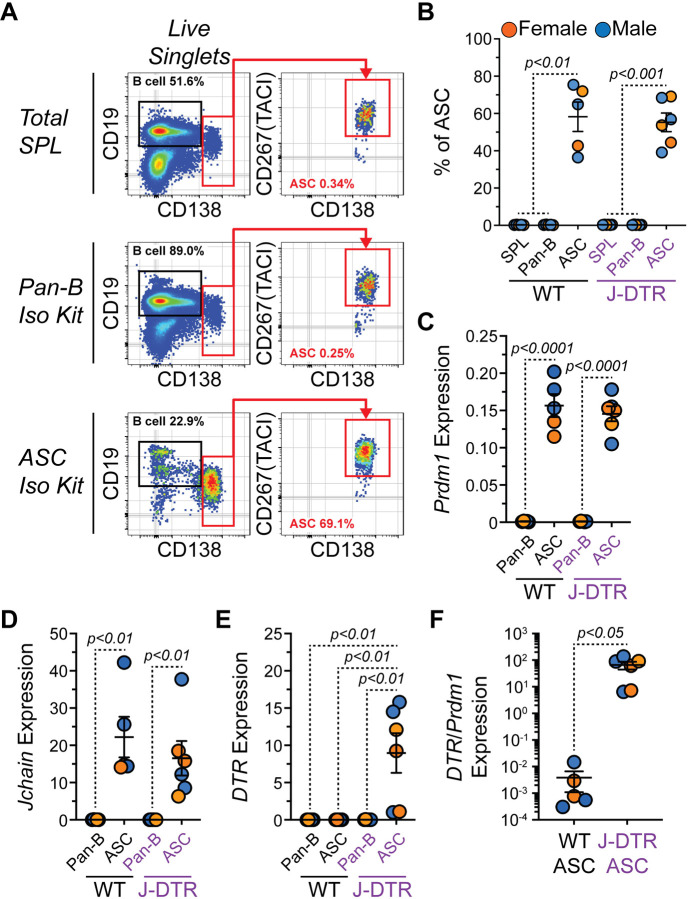

Next, we wanted to validate that DTR was expressed transcriptionally in ASCs. To do so, splenocytes from female and male Jchain+/+ (WT) and Jchain+/DTR (J-DTR) mice (3–7 months old) were harvested. Using Pan-B and CD138 (ASC) selection kits from STEMCELL Technologies, we enriched for splenic B cells (CD19+ CD138−/LO) and ASCs (CD138HI CD267(TACI)+) as confirmed by flow cytometry (Figures 2A–2B). cDNA was subsequently generated from these populations and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis showed that ASC enriched samples possessed significantly higher Prdm1 (Figure 2C) and Jchain (Figure 2D) gene expression. However, only ASCs enriched from the SPLs of J-DTR mice showed high levels of DTR gene expression (Figure 2E). Due to variability in the effectiveness of ASC enrichment, we also examined DTR expression when normalized to that of Prdm1 (Figure 2F). ASCs from J-DTR SPLs again displayed increased levels of DTR transcripts when compared to WT ASCs (Figure 2F).

Figure 2: Validation of DTR gene expression by ASCs from J-DTR mice.

(A) Representative flow cytometry pseudocolor plots showing gating of CD19+ CD138−/LO B cells and CD138HI CD267(TACI)+ ASCs in total SPL or cells purified with STEMCELL Technologies Pan-B and CD138 (ASC) isolation kits. Numbers in plots indicate percentages of gated populations within total live singlets. (B) Quantification of ASC percentages in total SPL or purified cells using Pan-B and ASC isolation kits. (C-E) Relative gene expression of (C) Prdm1, (D) Jchain and (E) DTR (HBEGF) in cells purified using Pan-B and ASC isolation kits. All values are relative to the expression of Actb. (F) DTR expression normalized to Prdm1 expression in WT and J-DTR ASCs. (B-F) Symbols represent individual 3–7 months old female (orange) and male (blue) mice. Horizontal lines represent mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). WT SPL, Pan-B and ASC: female n = 2, male n = 3; J-DTR SPL, Pan-B and ASC: female n = 3, male n = 3. Statistics: (B) One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test with ASCs for each genotype set as the control column. (C-F) Unpaired Student’s t-test.

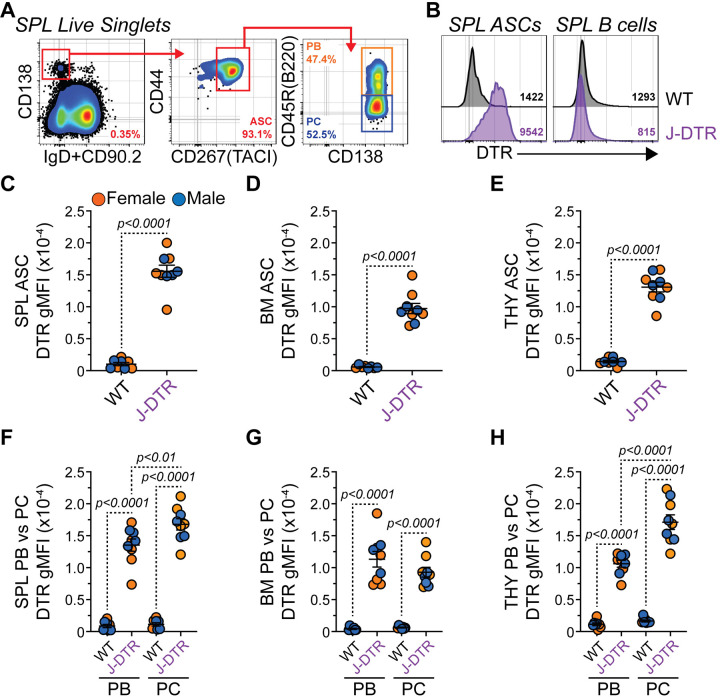

Finally, we confirmed that the DTR protein could be found on the surface of ASCs from J-DTR mice. ASCs from the SPL (Figure 3A), BM and THY were identified as CD138HI IgD−/LO CD90.2−/LO CD267(TACI)+ CD44+ similar to previously published data25. As shown in Figure 3B, DTR expression was readily observable on the surface of ASCs from the J-DTR SPL compared to WT SPL ASCs or B cells from both genotypes. Quantification of the DTR geometric mean fluorescence intensity (gMFI) demonstrated that J-DTR ASCs from the SPL (Figure 3C), BM (Figure 3D) and THY (Figure 3E) had significantly higher DTR expression compared to their WT counterparts. ASCs include 2 major populations: 1) proliferative, relatively immature and short-lived PBs and 2) post-mitotic, mature PCs with long-lived potential. In mice, CD45R(B220) expression can be used to delineate between these 2 populations (Figure 3A)9,10,25,26. In all 3 organs examined, DTR levels were increased in PBs and PCs from J-DTR mice compared to cells from WT animals (Figures 3F–3H). Notably, we observed increased DTR expression in PCs from the J-DTR SPL and THY relative to the PB compartment (Figures 3F, 3H). To determine if DTR was preferentially expressed in ASCs compared to other B cells types, we examined DTR surface expression on total B cells (CD19+ CD90.2− CD138−/LO) as well as germinal center (or germinal center-like) B cells (GCB, CD19+ CD90.2− CD138−/LO CD95(Fas)+ GL7+) from both the SPL (Figures S2A–S2B) and THY (Figures S2C–S2D). As a comparison within the same flow cytometry samples, we also analyzed the CD138HI CD90.2− compartment which would be enriched for ASCs. As expected, total B cells demonstrated minimal DTR expression while ASC-containing CD138HI CD90.2− cells possessed high levels of the protein (Figures S2E–S2F) in J-DTR animals. Within the SPL, J-DTR GCBs possessed an intermediate phenotype while the GCB-like population in the THY seemingly lacked DTR expression (Figures S2E–S2F). Overall, these data suggest that while all ASCs from J-DTR mice preferentially express the DTR, some organ-specific differences may exist based upon maturation status.

Figure 3: Validation of DTR surface protein expression by ASCs from J-DTR mice. Related to Figure S2.

(A) Representative flow cytometry pseudocolor plots showing gating of SPL ASCs as CD138HI IgD−/LO CD90.2−/LO CD267(TACI)+ CD44+. ASC subset gating is shown for PBs (CD45R(B220)+) and PCs (CD45R(B220)−). Numbers in plots indicate percentages of gated populations within the immediate parent population. (B) Representative flow cytometry histogram overlays showing surface expression of DTR by SPL ASCs and B cells from both WT and J-DTR mice. SPL B cells were gated as CD19+ CD138−/LO. Numbers in plots indicate DTR gMFIs. (C-E) gMFIs for WT and J-DTR ASCs from (C) SPL, (D) BM. Horizontal lines represent mean ± SEM. WT: female n = 4, male n = 4; J-DTR: female n = 5, male n = 4. Statistics: (C-E) Unpaired Student’s t-test. (F-H) Unpaired Student’s t-test comparing WT and J-DTR samples. Paired Student’s t-test comparing PBs and PCs within a genotype.

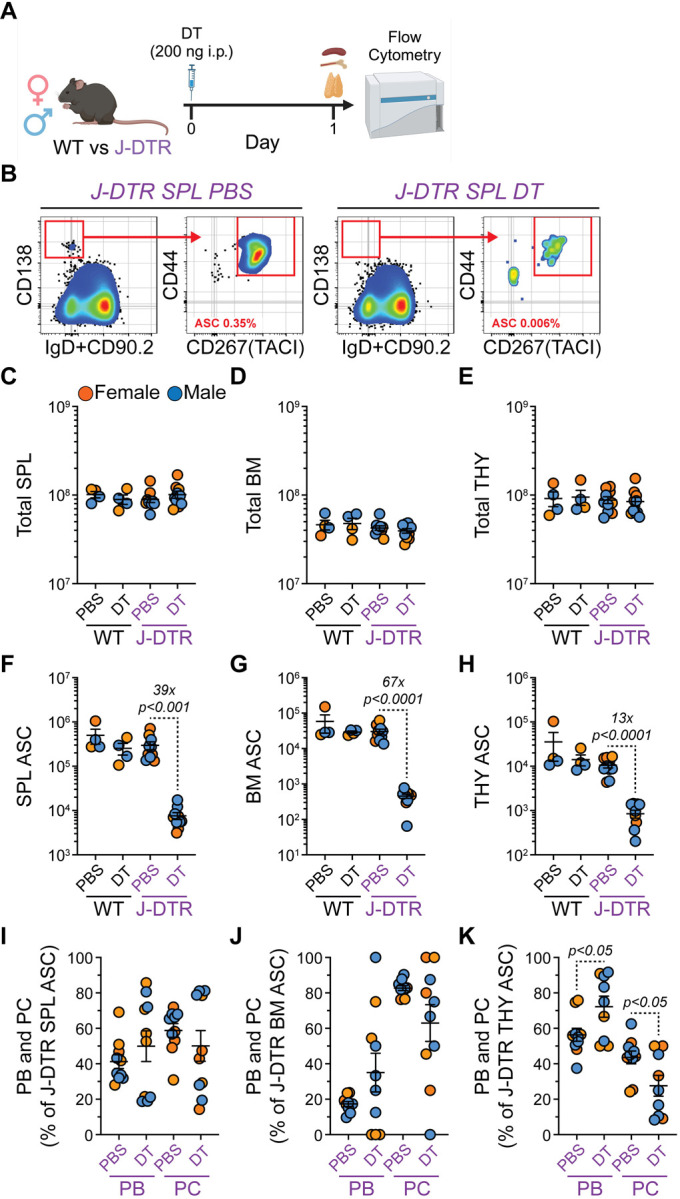

DT treatment leads to acute ASC depletion in J-DTR mice

To test the functionality of our J-DTR mouse model, we administered intraperitoneal (i.p.). injections of either phosphate buffered saline (PBS) or 200 ng DT (100 μL volume) to both female and male, 3–4 months old WT and J-DTR animals (Figure 4A). The next day, mice were euthanized and ASC populations in the SPL, BM and THY were examined by flow cytometry (Figures 4A–4B). DT had no overall impact on cellularity in any organ from either genotype (Figures 4C–4E). In all 3 organs assessed, DT treatment led to significant reductions in ASC numbers only in J-DTR mice (Figures 4F–4H). Notably, there was some variability in this effect as SPL (Figure 4F), BM (Figure 4G) and THY (Figure 4H) ASCs were reduced by ~39x, 67x and 13x, respectively. Our analysis of DTR expression indicated some differences based upon maturation status (Figures 3F, 3H) with PCs having higher expression than PBs in the SPL and THY. As such, we also assessed if DT-mediated ablation differentially impacted PBs versus PCs (Figures 4I–4K). Within the SPL and BM ASC compartments (Figures 4I–4J), DT-treated J-DTR mice displayed large variability in the relative percentages of PBs and PCs with no clear skewing towards either population. In contrast, J-DTR THY ASCs demonstrated a relative increase in PBs upon DT injection suggesting increased sensitivity of the PC compartment to DT (Figure 4K). Upon examination of DTR expression, we observed that residual ASCs present in DT-treated J-DTR mice expressed significantly less DTR compared to PBS-treated J-DTR animals (Figures S3A–S3C) perhaps suggesting that these cells were nascently generated. Until now, we have measured depletion based upon flow cytometry and cellular identification via cell surface markers. Thus, we performed enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot) assays (Figures S3D–S3G) for total IgG from the SPL, BM and THY to provide a secondary confirmation of ASC depletion. In all 3 organs analyzed, administration of DT to J-DTR mice resulted in a significant reduction in the number of IgG spots per 105 cells (Figures S3E–S3G). While not necessarily expected, we observed that WT mice treated with DT displayed increased SPL IgG spots (Figure S3E) possibly indicating a rapid differentiation response following DT exposure.

Figure 4: Single dose administration of DT leads to the acute depletion of ASCs in J-DTR mice. Related to Figure S3.

(A) Schematic showing DT treatment of WT and J-DTR mice. 3–4 months old animals were given a single i.p. dose of 200 ng DT in 100 μL 1x PBS. Control mice received 100 μL of 1x PBS. Mice were euthanized after 1 day and SPL, BM and THY were assessed for ASCs and other B cell populations via flow cytometry. Schematic made with BioRender. (B) Representative flow cytometry pseudocolor plots showing gating of SPL ASCs from J-DTR mice treated with PBS or DT. Cells were initially gated on live singlets and numbers in plots indicate percentages of ASCs within total live singlets. (C-E) Total cell numbers for (C) SPL, (D) BM and (E) THY of WT and J-DTR mice treated with PBS or DT. Data presented on Log10 scale to show full range. (F-H) Total ASC numbers for (F) SPL, (G) BM and (H) THY of WT and J-DTR mice treated with PBS or DT. Data presented on Log10 scale to show full range. (I-K) Percentages of PBs and PCs within ASC populations from (I) SPL, (J) BM and (K) THY of J-DTR mice treated with PBS or DT. (C-K) Symbols represent individual female (orange) and male (blue) mice. Horizontal lines represent mean ± SEM. WT PBS and DT: female n = 2, male n = 2; J-DTR PBS and DT: female n = 5, male n = 5. Statistics: (C-H) Unpaired Student’s t-test with comparisons made between PBS and DT treatments within a genotype. (I-K) Unpaired Student’s t-test with comparisons made between PBS and DT treatments within an ASC subset.

Since we observed low level DTR expression by selected upstream B cell populations, we also evaluated how DT treatment impacted these populations. Overall, SPL and THY B cells were not impacted by DT treatment (Figures S3H–S3I). However, J-DTR mice demonstrated a reduction in their SPL GCB numbers following administration of DT (~8.8x, Figure S3J) supporting the above observation of DTR expression in at least a portion of SPL GCBs. While this level of depletion was significant, it was far less than that observed for SPL ASCs (~39x, Figure 4F) from the same animals. In contrast, DT had no impact on THY GCB-like cells (Figure S3K). Taken together, these data demonstrate that DT can induce acute ASC depletion in J-DTR mice with a limited impact on other mature B cells populations especially in the THY.

DT treatment of J-DTR mice allows for kinetic analysis of ASC production

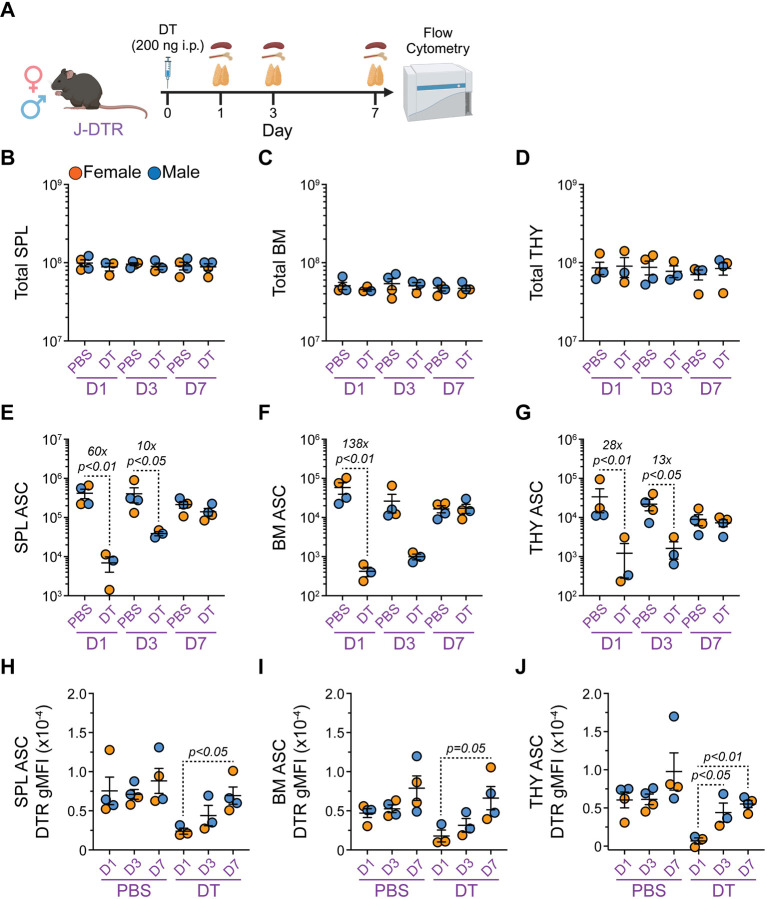

Understanding the kinetics of ASC formation and how newly generated ASCs compete with pre-existing cells for survival niches are important considerations in vaccine development. To determine if our J-DTR mice provide a suitable model to evaluate ASC differentiation kinetics, we treated 3–4 months old female and male J-DTR mice with either PBS or DT (200 ng) (Figure 5A and Figure S4A). Subsequently, animals were euthanized at days 1, 3 and 7 post-treatment with B cell and ASC populations from SPL, BM and THY being analyzed by flow cytometry (Figure 5A and Figure S4A). Similar to above, DT treatment did not alter SPL, BM or THY cellularity in J-DTR mice (Figures 5B–5D)

Figure 5: Single dose DT administration allows for the assessment of ASC reconstitution kinetics in J-DTR mice. Related to Figure S4.

(A) Schematic showing DT treatment of J-DTR mice. 3–4 months old animals were given a single i.p. dose of 200 ng DT in 100 μL 1x PBS. Control mice received 100 μL of 1x PBS. Mice were euthanized at days 1, 3 and 7 post-injection. SPL, BM and THY were assessed for ASCs via flow cytometry. Schematic made with BioRender. (B-D) Total cell numbers for (B) SPL, (C) BM and (D) THY of J-DTR mice treated with PBS or DT. Data presented on Log10 scale to show full range. (E-G) Total ASC numbers for (E) SPL, (F) BM and (G) THY of J-DTR mice treated with PBS or DT. Data presented on Log10 scale to show full range. (H-J) DTR gMFIs for ASCs from (H) SPL, (I) BM and (J) THY of J-DTR mice treated with PBS or DT. (B-J) Symbols represent individual female (orange) and male (blue) mice. Horizontal lines represent mean ± SEM. J-DTR day 1 PBS: female n = 2, male n = 2; J-DTR day 1 DT: female n = 2, male n = 1; J-DTR day 3 PBS: female n = 2, male n = 2; J-DTR day 3 DT: female n = 1, male n = 2; J-DTR day 7 PBS: female n = 2, male n = 2; J-DTR day 7 DT: female n = 2, male n = 2. (B-G) Statistics: Kruskal-Wallis test (nonparametric) with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. Comparisons made between PBS and DT treatments for a given day. (H-J) Statistics: One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Comparisons made between D1, D3 and D7 for a given treatment.

Consistent with previous data (Figure 4), DT significantly reduced SPL ASCs in J-DTR mice at 1-day post-injection (~60x, Figure 5E) with ASCs still being depleted ~10x at day 3 (Figure 5E). By day 7, SPL ASC numbers resembled those in PBS-treated animals (Figure 5E). Within the BM, ASCs were acutely depleted ~138x at day 1 and ultimately reached levels observed in control mice by day 7 (Figure 5F). At day 3, BM ASCs appeared to still be reduced in DT-treated animals although this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 5F). Finally, administration of DT resulted in reduced THY ASC numbers at both day 1 (~28x, Figure 5G) and day 3 (~13x, Figure 5G). Similar to the SPL and BM, THY ASCs returned to normal levels by day 7 post-DT (Figure 5G). Interestingly enough, ASCs from DT-treated J-DTR mice expressed lower DTR at day 1 compared to day 7 post-treatment in all 3 organs assessed (Figures 5H–5J). As with the acute depletion studies (Figure S3), we also assessed the effects of DT-treatment on total B cell and GCB (or GCB-like) populations in the SPL and THY of J-DTR animals (Figures S4B–S4E). The only notable change was reflected in a reduction in J-DTR SPL GCBs at 1 day following DT administration (Figure S4D). SPL GCBs were nearly recovered by day 3 and were at normal levels at day 7 post-DT treatment (Figure S4D). Collectively, these data demonstrate that ASCs are continuously replenished in the SPL, BM and THY of young mice and that our J-DTR mouse model provides a suitable platform to study ASC reconstitution kinetics.

Discussion

The data presented here outline the creation and validation of a mouse model in which the endogenous Jchain locus drives DTR gene expression (J-DTR mice). As shown, ASCs from J-DTR mice express high amounts of DTR protein on the cell surface and can be acutely depleted following a single dose of DT. Furthermore, due to the short half-life of DT, we were able to demonstrate that these mice provide a platform to assay ASC differentiation kinetics following their initial ablation. Finally, we performed all experiments using both sexes showing that this model could be utilized to study ASCs in both females and males.

It is difficult to compare models without testing them side-by-side. However, our J-DTR mice appear to be at least as effective as the recently published BICREAD7 and CD138-DTR13 mouse strains. This was demonstrated by the ability to deplete ASCs within 1 day following a single injection of DT. In this report, we presented our data using a Log10 scale for the purpose of showing the full range of ASC depletion. We did not reach 100% depletion following a single dose of DT which may be a result of the previously reported limited DT half-life17 combined with the time between DT treatment and terminal harvest which was ~15–18 hours for our 1 day depletion studies. It is possible that repetitive DT injections would have better “saturated the system” allowing for more complete depletion. Regardless, ASC depletion was still highly significant and clearly surpassed in magnitude what was previously achieved with antibody-mediated targeting of ASCs12.

While no single model is perfect, the J-DTR model provides an alternative platform to deplete ASCs acutely. This is particularly relevant as DT treatment of BICREAD mice would presumably also target Prdm1 expressing tissue resident and/or memory T cell subsets14–16 while CD138-DTR mice may possess experimental caveats due to potentially targeting a subset of IL-10 producing CD138+ macrophages27. Administration of DT to J-DTR mice did not result in alterations in organ cellularity of the SPL, BM and THY or even total B cell populations in the SPL and THY. This was an important result and indicated that widespread leaky expression of DTR was not present. However, we did see a reduction in J-DTR SPL GCBs upon DT treatment which may have been a direct effect as we were able to detect low levels of surface DTR expression on these cells. This observation is consistent with recent data using a Jchain-driven Tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase in combination with a tdTomato reporter which labelled GCBs following West Nile virus vaccination28. Markedly, GCB-like cells in the THY did not share this phenotype. In this study, we defined THY GCB-like cells as expressing both CD95(Fas) and GL7. These cells possess similarities to the GL7+ CD38+ B cell subset previously identified in the THY29 and may be more akin to an activated memory B cell phenotype30.

An interesting observation was that J-DTR ASCs remaining 1 day following DT treatment expressed low to intermediate levels of surface DTR compared to ASCs from PBS-treated J-DTR mice. While it is possible that these cells would never express high DTR levels, we suspect that their low expression may have been a sign of overall immaturity and their most likely recent differentiation. In alignment with this, we observed the lowest DTR levels by ASCs from J-DTR mice immediately following DT treatment when compared to those present 7 days post-DT. Furthermore, our ELISpot experiments demonstrated a functional lack of ASCs at a larger magnitude than what was shown purely based upon flow cytometric assessments. In total, these data are consistent with previous observations demonstrating the highest level of IgG secretion in the most mature ASC subsets31.

To demonstrate the feasibility of this model in terms of studying ASC differentiation kinetics, we administered a single dose of DT to J-DTR mice and assayed ASC numbers 1-, 3- and 7-days post-treatment. While these experiments were limited in power, they clearly showed the ability to observe ASC reconstitution partially in the SPL at 3 days post-DT with ASC numbers returning to normal by 7 days. Reconstitution in the BM and THY was also complete by 7 days. As B cell activation and ASC production in the THY is particularly relevant to myasthenia gravis (MG)32,33, the ability to deplete THY ASCs in J-DTR mice and study their generation within the organ may provide a critical tool that can be used to understand MG etiology34. Furthermore, we previously demonstrated that THY ASCs possessed major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II) on their cell surface and transcriptionally expressed machinery required for antigen presentation25. Hence, using this model to deplete THY ASCs long-term or over discrete developmental windows may prove informative regarding their potential to regulate T cell development and selection in the THY. In summary, the J-DTR mouse model represents a new genetic platform that can be leveraged to study ASC production, and potentially even function, in a variety of experimental contexts.

Limitations of the study

The work presented here focused on validating and establishing the J-DTR mouse model as a tool to study ASC differentiation. While our experiments evaluated the functionality of these mice at homeostasis, it is expected that DTR-expressing ASCs would continue to be sensitive to DT treatment even in the context of infection-based mouse models, although this remains to be tested. Furthermore, additional experiments will be required to demonstrate the efficacy of long-term ASC depletion using repetitive DT administration.

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Peter Dion Pioli (peter.pioli@usask.ca).

Materials availability

Materials underlying this article will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

Data and code availability

Flow cytometry data reported in this study will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

Any information required for data reanalysis is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Experimental Animals

J-DTR were originally generated fee-for-service by InGenious Targeting Laboratory. Upon receipt, animals were quarantined and verified pathogen and parasite free before being released for use. Animals were subsequently bred and maintained at the USask Lab Animals Services Unit. WT and Jchain+/DTR heterozygote female and male mice were utilized for all experiments. Animals ranged in age from 3–7 months when used for experiments. Animal care and use were conducted according to the guidelines of the USask University Animal Care Committee Animal Research Ethics Board.

METHOD DETAILS

Creation of J-DTR mice

This mouse model was created using a genetically engineered mouse embryonic stem cell line, in which a custom targeting vector was designed so that the IRES-DTR cassette was inserted after the TAG stop codon of the Jchain gene. The knock-in cassette was followed by an FRT-flanked Neo selection cassette. The long homology arm (LA) of the vector is ~6 kb in length and the short homology arm (SA) is ~2.1 kb in length. The region used to construct the targeting vector was subcloned from a positively identified C57BL/6 BAC clone using homologous recombination-based techniques. The targeting vector was confirmed by restriction analysis and sequencing after each modification step.

The targeting vector was then linearized and electroporated into a FLP C57BL6 (BF1) embryonic stem cell line. After selection with G418, antibiotic-resistant colonies were picked, expanded and screened via PCR analysis and sequenced for homologous recombinant ES clones. The Neo resistance cassette was removed via FLP recombinase in the ES cells during expansion. Positively targeted ES clones were then microinjected into BALB/c blastocysts and transferred into pseudo-pregnant females. Resulting chimeras with a high percentage black coat color were mated to C57BL/6N WT mice, after which the offspring were tail-tipped and genotyped for germline transmission of the targeted allele sequence. Germline mice were identified as heterozygous for the co-expression of the DTR cassette in the mouse Jchain gene locus. Upon receipt, mice were bred to eliminate the gene encoding the flippase (i.e., FLP) recombinase.

Genomic DNA Isolation and Genotyping

Ear biopsies were incubated at 100 °C in 400 μL of 50 mM sodium hydroxide (NaOH) until tissue was fully dissolved. NaOH was neutralized by the addition of 1 M Tris-hydrochloric acid (HCl), pH 8.0 (50 μL). Samples were vortexed and then centrifuged at 25 °C and 12,000g for 2 minutes. Supernatant (200 μL) was transferred to a new 1.5-mL tube. After the addition of 3 M sodium acetate (NaOAc), pH 5.2 (20 μL) and 95% ethanol (EtOH) (660 μL), samples were vortexed and DNA was precipitated overnight (O/N) at −20 °C. The next day, samples were centrifuged at 4 °C and 12,000g for 5 minutes. Supernatant was aspirated and DNA pellets were resuspended in 100 μL of 0.1x Tris-EDTA buffer.

For genotyping PCR, each reaction consisted of 10 μL Platinum II Host-Start PCR 2x Master Mix Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 14000012), 1 μL forward primer, 1 μL reverse primer, 2 μL DNA and 6 μL H2O. All primers were resuspended at a concentration of 1 μg/mL in 01.x TE. Reactions were amplified using a Veriti 96-well thermal cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reactions products were electrophoresed in 2% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide and products were visualized under ultraviolet light using a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc Imaging System. All genotyping primer sequences are listed in the Key Resources Table and PCR amplification protocols are available upon request.

In Vivo DT Treatment

1 mg of lyophilized DT from Corynebacterium diphtheriae (Millipore Sigma, Cat# D0564) was resuspended in 0.5 mL sterile H2O yielding a 2 mg/mL DT concentration in a 10 mM Tris-1mM EDTA, pH 7.5 solution. For injection, DT was subsequently diluted to 2 μg/mL in 1x PBS (Gibco, Cat# 21600–069). Mice received 100 μL i.p. injections of either PBS or DT (200 ng total).

Isolation of Bone Marrow, Spleen and Thymus Tissue

All tissues were processed and collected in calcium and magnesium-free 1x PBS. SPL and THY were dissected and crushed between the frosted ends of two slides. BM was isolated from both femurs and tibias by cutting off the end of bones and flushing the marrow from the shafts and ends using a 23-gauge needle. Cell suspensions were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 4 °C and 600g. Red blood cells were lysed by resuspending cells in 3 mL of 1x red blood cell lysis buffer on ice for ~3 minutes. Lysis was stopped with the addition of 7 mL of 1x PBS. Cell suspensions were strained through 40 μm filters and counted on a Countess 3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using Trypan Blue to exclude dead cells. Cell suspensions were centrifuged as before (5 minutes at 4 °C and 600g) and resuspended at 2×107 cells/mL in 1x PBS + 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Fisher BioReagents, Cat# BP9706–100) before use.

B cell and ASC enrichment

EasySep Mouse Pan-B cell Isolation and EasySep Release Mouse CD138 Positive Selection kits from STEMCELL Technologies were used to enrich B cells and ASCs from ~5×107 SPL cells following manufacture guidelines. Isolated cells were collected in a final volume of 1.5 mL of 1x PBS + 2% fetal bovine serum + 1mM EDTA and counted using a Countess 3 with Trypan Blue to exclude dead cells and calculate final yield.

QPCR

RNA was extracted from isolated B cells and ASCs using the PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 12183025). RNA was quantified using a NanoDrop Onec (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and verified to have a A260/280 ratio of ~2.0. The Maxima H-Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit with dsDNAse (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# K1682) was used to generate cDNA. Each cDNA synthesis reaction included ≥10 ng RNA mixed with 1 μL random hexamers primers, 1 μL 10mM dNTP mix, 4 μL RT buffer, 1 μL Maxima H-minus enzyme mix and the appropriate volume of water required to obtain a 20 μL reaction. The reaction mixtures were incubated in a Veriti 96-well thermal cycler using the manufacturer recommended amplification program. QPCR was performed using a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Each 20 μL reaction contained 2x TAQMAN Fast Advanced Master Mix (10 μL), 20x TaqMan primer (1 μL), cDNA (2 μL) and water (7 μL). Triplicate reactions were run 96-well plates using standard TAQMAN amplification conditions. All primers are listed in the Key Resources Table. Expression for target genes was calculated as 2(ActbCT – TargetCT) and represents the average derived from triplicate technical replicates.

Immunostaining

All staining procedures were performed in 1x PBS + 0.1% BSA. Samples were labeled with a CD16/32 Ab to eliminate non-specific binding of Abs to cells via Fc receptors. All Abs utilized are listed in the Key Resources Table. Cells were incubated on ice for 30 minutes in the dark with the appropriate Abs. Unbound Abs were washed from cells with 1x PBS + 0.1% BSA followed by centrifugation for 5 minutes at 4 °C and 600g. Supernatants were decanted, and cell pellets were resuspended in an appropriate volume of 1x PBS + 0.4% BSA + 2 mM EDTA for flow cytometric analysis. Before analysis, cells were strained through a 40 μm filter mesh and kept on ice in the dark. eBioscience Fixable Viability (Live-Dead) Dye eFluor 780 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 65-0865-14) was added to samples to assess dead cell content. The stock solution was diluted 1:250 in 1x PBS and 10 μL was added to ~5 × 106 cells per stain. Live-Dead stain was added concurrent with surface staining Abs.

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed on a CytoFLEX (Beckman Coulter) located in the Cancer Cluster at USask. Total cells were gated using side scatter area (SSC-A) versus forward scatter (FSC-A) area. Singlets were identified using sequential gating of FSC-height (H) versus FSC-A and SSC-H versus SSC-A. All data were analyzed using FlowJo (v10) software.

ELISpot

ELISpot plates (Millipore Sigma, Cat# MSIPS4W10) were briefly incubated at RT for 1 minute with 15 μL of 35% EtOH. EtOH was removed and wells were washed 3 times with 150 μL of 1x PBS. Subsequently, wells were coated O/N at 4 °C with 100 μL of capture Ab. The capture Ab (Millipore Sigma, Cat# SAB3701043–2MG) recognized mouse total IgG+IgM+IgA isotypes and was pre-diluted in 1x PBS to a final concentration of 5 μg/mL before use. The next day, coating Abs were removed and wells were washed 3 times with 150 μL RPMI 1640. Plates were subsequently blocked with 150 μL RPMI for a minimum of 2 hours at 37 °C in a 5% CO2/20% O2 tissue culture incubator. Blocking solution was removed and total cells from BM, SPL and THY were deposited into wells with a target number of 105 cells per well in a 100 μL volume (2–3 wells per sample). Cells had previously been resuspended at 1×106 cells/mL in RPMI supplemented with a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL) (10 ng/mL), interleukin (IL)-6 (10 ng/mL), heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (10%), Penicillin-Streptomycin (100 U/mL), L-glutamine (2 mM), Gentamicin (50 μg/mL), sodium pyruvate (1 mM), non-essential amino acids (1x), non-essential vitamins (1x) and 2-mercaptoethanol (10−05 M). Cells were then incubated O/N (>12 hours) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2/20% O2 tissue culture incubator. The next day, culture supernatants and cells were removed. Wells were washed 3 times with 150 μL of 1x PBS then an additional 3 times with 150 μL of 1x PBS + 0.1% Tween-20 + 1% BSA. Secondary Ab conjugated to horse radish peroxidase (HRP) was added at a volume of 100 μL per well and plates were incubated for 2 hours at RT. Anti-IgG-HRP (SouthernBiotech, Cat# 1015–05) was diluted 1:50,000 in 1x PBS + 0.1% Tween-20 + 1% BSA before use. Following incubation, Abs were removed and plates were washed 3 times with 150 μL of 1x PBS + 0.1% Tween-20 + 1% BSA. An additional 3 washes with 150 μL of 1x PBS were performed. To reveal “spots”, 100 μL of Developing Solution from the AEC Substrate Set (BD Biosciences, Cat# 551951) was added to each well. Plates were shaken at 200 rpm for 30 minutes at RT. Developing Solution was removed and plates were washed 5 times with 150 μL of H2O. Well backings were removed, and plates dried at RT after which “spots” were visualized with a Mabtech ASTOR ELISPOT reader. Additional wells lacking capture Abs were developed to gauge background. For spot quantification, counting was restricted to a 1200-pixel area of interest to avoid edge artifacts. For each genotype and treatment combination, 2–3 background wells were counted, averaged and then subtracted to obtain the reported spot numbers.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The numbers of mice used (n =) per experiment are listed in the Figure Legends. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (v8.4.2) software. Quantification of cell numbers and various flow cytometry data are graphically represented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses are described within each Figure Legend and statistically significant p-values are shown within each Figure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the University of Saskatchewan College of Medicine via intramural startup funds and the Office of the Vice Dean Research College of Medicine Research Award (CoMRAD). This work was further supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R03AG071955, Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation (Establishment Grant, Award Number 6230) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Discovery Grant, Award Number 2024-06646). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any funding sources.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

A United States Provisional Patent Application No. 63/568,498 has been filed as a result of the generation of the J-DTR mouse strain. The authors declare no other competing interests.

Inclusion and Diversity

We support inclusive, diverse and equitable conduct of research.

References

- 1.Nutt S.L., Hodgkin P.D., Tarlinton D.M., and Corcoran L.M. (2015). The generation of antibody-secreting plasma cells. Nature reviews. Immunology 15, 160–171. 10.1038/nri3795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helmreich E., Kern M., and Eisen H.N. (1961). The secretion of antibody by isolated lymph node cells. The Journal of biological chemistry 236, 464–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hibi T., and Dosch H.M. (1986). Limiting dilution analysis of the B cell compartment in human bone marrow. European journal of immunology 16, 139–145. 10.1002/eji.1830160206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiest D.L., Burkhardt J.K., Hester S., Hortsch M., Meyer D.I., and Argon Y. (1990). Membrane biogenesis during B cell differentiation: most endoplasmic reticulum proteins are expressed coordinately. The Journal of cell biology 110, 1501–1511. 10.1083/jcb.110.5.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forthal D.N. (2014). Functions of Antibodies. Microbiol Spectr 2, AID-0019–2014. 10.1128/microbiolspec.AID-0019-2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaudette B.T., Jones D.D., Bortnick A., Argon Y., and Allman D. (2020). mTORC1 coordinates an immediate unfolded protein response-related transcriptome in activated B cells preceding antibody secretion. Nature communications 11, 723. 10.1038/s41467-019-14032-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu X., Yao J., Zhao Y., Wang J., and Qi H. (2022). Heterogeneous plasma cells and long-lived subsets in response to immunization, autoantigen and microbiota. Nature immunology 23, 1564–1576. 10.1038/s41590-022-01345-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scharer C.D., Patterson D.G., Mi T., Price M.J., Hicks S.L., and Boss J.M. (2020). Antibody-secreting cell destiny emerges during the initial stages of B-cell activation. Nature communications 11, 3989. 10.1038/s41467-020-17798-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koike T., Fujii K., Kometani K., Butler N.S., Funakoshi K., Yari S., Kikuta J., Ishii M., Kurosaki T., and Ise W. (2023). Progressive differentiation toward the long-lived plasma cell compartment in the bone marrow. The Journal of experimental medicine 220. 10.1084/jem.20221717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson M.J., Ding Z., Dowling M.R., Hill D.L., Webster R.H., McKenzie C., Pitt C., O’Donnell K., Mulder J., Brodie E., et al. (2023). Intrinsically determined turnover underlies broad heterogeneity in plasma-cell lifespan. Immunity 56, 1596–1612 e1594. 10.1016/j.immuni.2023.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu A.Q., Barbosa R.R., and Calado D.P. (2020). Genetic timestamping of plasma cells in vivo reveals tissue-specific homeostatic population turnover. eLife 9. 10.7554/eLife.59850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pioli P.D., Casero D., Montecino-Rodriguez E., Morrison S.L., and Dorshkind K. (2019). Plasma Cells Are Obligate Effectors of Enhanced Myelopoiesis in Aging Bone Marrow. Immunity 51, 351–366 e356. 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vijay R., Guthmiller J.J., Sturtz A.J., Surette F.A., Rogers K.J., Sompallae R.R., Li F., Pope R.L., Chan J.A., de Labastida Rivera F., et al. (2020). Infection-induced plasmablasts are a nutrient sink that impairs humoral immunity to malaria. Nature immunology 21, 790–801. 10.1038/s41590-020-0678-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milner J.J., Toma C., He Z., Kurd N.S., Nguyen Q.P., McDonald B., Quezada L., Widjaja C.E., Witherden D.A., Crowl J.T., et al. (2020). Heterogenous Populations of Tissue-Resident CD8(+) T Cells Are Generated in Response to Infection and Malignancy. Immunity 52, 808–824 e807. 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rutishauser R.L., Martins G.A., Kalachikov S., Chandele A., Parish I.A., Meffre E., Jacob J., Calame K., and Kaech S.M. (2009). Transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 promotes CD8(+) T cell terminal differentiation and represses the acquisition of central memory T cell properties. Immunity 31, 296–308. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zundler S., Becker E., Spocinska M., Slawik M., Parga-Vidal L., Stark R., Wiendl M., Atreya R., Rath T., Leppkes M., et al. (2019). Hobit- and Blimp-1-driven CD4(+) tissue-resident memory T cells control chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature immunology 20, 288–300. 10.1038/s41590-018-0298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamaizumi M., Uchida T., Takamatsu K., and Okada Y. (1982). Intracellular stability of diphtheria toxin fragment A in the presence and absence of anti-fragment A antibody. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 79, 461–465. 10.1073/pnas.79.2.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmes R.K. (2000). Biology and molecular epidemiology of diphtheria toxin and the tox gene. The Journal of infectious diseases 181 Suppl 1, S156–167. 10.1086/315554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwamoto R., Higashiyama S., Mitamura T., Taniguchi N., Klagsbrun M., and Mekada E. (1994). Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor, which acts as the diphtheria toxin receptor, forms a complex with membrane protein DRAP27/CD9, which up-regulates functional receptors and diphtheria toxin sensitivity. The EMBO journal 13, 2322–2330. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06516.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keen J.H., Maxfield F.R., Hardegree M.C., and Habig W.H. (1982). Receptor-mediated endocytosis of diphtheria toxin by cells in culture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 79, 2912–2916. 10.1073/pnas.79.9.2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitamura T., Umata T., Nakano F., Shishido Y., Toyoda T., Itai A., Kimura H., and Mekada E. (1997). Structure-function analysis of the diphtheria toxin receptor toxin binding site by site-directed mutagenesis. The Journal of biological chemistry 272, 27084–27090. 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lahl K., Loddenkemper C., Drouin C., Freyer J., Arnason J., Eberl G., Hamann A., Wagner H., Huehn J., and Sparwasser T. (2007). Selective depletion of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induces a scurfy-like disease. The Journal of experimental medicine 204, 57–63. 10.1084/jem.20061852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez Y.B.A., Rajendiran S., Manso B.A., Krietsch J., Boyer S.W., Kirschmann J., and Forsberg E.C. (2022). New transgenic mouse models enabling pan-hematopoietic or selective hematopoietic stem cell depletion in vivo. Scientific reports 12, 3156. 10.1038/s41598-022-07041-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saito M., Iwawaki T., Taya C., Yonekawa H., Noda M., Inui Y., Mekada E., Kimata Y., Tsuru A., and Kohno K. (2001). Diphtheria toxin receptor-mediated conditional and targeted cell ablation in transgenic mice. Nat Biotechnol 19, 746–750. 10.1038/90795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pioli K.T., Lau K.H., and Pioli P.D. (2023). Thymus antibody-secreting cells possess an interferon gene signature and are preferentially expanded in young female mice. iScience 26, 106223. 10.1016/j.isci.2023.106223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chernova I., Jones D.D., Wilmore J.R., Bortnick A., Yucel M., Hershberg U., and Allman D. (2014). Lasting antibody responses are mediated by a combination of newly formed and established bone marrow plasma cells drawn from clonally distinct precursors. Journal of immunology 193, 4971–4979. 10.4049/jimmunol.1401264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han S., Zhuang H., Shumyak S., Wu J., Li H., Yang L.J., and Reeves W.H. (2017). A Novel Subset of Anti-Inflammatory CD138(+) Macrophages Is Deficient in Mice with Experimental Lupus. Journal of immunology 199, 1261–1274. 10.4049/jimmunol.1700099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong R., Belk J.A., Govero J., Uhrlaub J.L., Reinartz D., Zhao H., Errico J.M., D’Souza L., Ripperger T.J., Nikolich-Zugich J., et al. (2020). Affinity-Restricted Memory B Cells Dominate Recall Responses to Heterologous Flaviviruses. Immunity 53, 1078–1094 e1077. 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez R.J., Breed E.R., Worota Y., Ashby K.M., Voboril M., Mathes T., Salgado O.C., O’Connor C.H., Kotenko S.V., and Hogquist K.A. (2023). Type III interferon drives thymic B cell activation and regulatory T cell generation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 120, e2220120120. 10.1073/pnas.2220120120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pape K.A., Taylor J.J., Maul R.W., Gearhart P.J., and Jenkins M.K. (2011). Different B cell populations mediate early and late memory during an endogenous immune response. Science 331, 1203–1207. 10.1126/science.1201730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halliley J.L., Tipton C.M., Liesveld J., Rosenberg A.F., Darce J., Gregoretti I.V., Popova L., Kaminiski D., Fucile C.F., Albizua I., et al. (2015). Long-Lived Plasma Cells Are Contained within the CD19(−)CD38(hi)CD138(+) Subset in Human Bone Marrow. Immunity 43, 132–145. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hill M.E., Shiono H., Newsom-Davis J., and Willcox N. (2008). The myasthenia gravis thymus: a rare source of human autoantibody-secreting plasma cells for testing potential therapeutics. J Neuroimmunol 201–202, 50–56. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Willcox H.N., Newsom-Davis J., and Calder L.R. (1984). Cell types required for anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody synthesis by cultured thymocytes and blood lymphocytes in myasthenia gravis. Clin Exp Immunol 58, 97–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pioli K.T., and Pioli P.D. (2023). Thymus antibody-secreting cells: once forgotten but not lost. Frontiers in immunology 14, 1170438. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1170438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Flow cytometry data reported in this study will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

Any information required for data reanalysis is available from the lead contact upon request.