Abstract

Steroid receptors regulate gene expression for many important physiologic functions and pathologic processes. Receptors for estrogen, progesterone, and androgen have been extensively studied in breast cancer and their expression provides prognostic information as well as targets for therapy. Noninvasive imaging utilizing positron emission tomography and radiolabeled ligands targeting these receptors can provide valuable insight into predicting treatment efficacy, staging whole-body disease burden, and identifying heterogeneity in receptor expression across different metastatic sites. This review provides an overview of steroid receptor imaging with a focus on breast cancer and radioligands for estrogen, progesterone, and androgen receptors.

Keywords: Estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, androgen receptor, positron emission tomography, breast cancer

Introduction

Steroid hormone receptors are part of a larger group of proteins in the nuclear receptor superfamily.1,2 Nuclear receptors primarily function as transcription factors responsible for cell signaling, differentiation, proliferation, metabolism, and development.1,2 Abnormal receptor expression or function is a hallmark of numerous diseases, including cancer.1,2

Steroid receptors generally act upon binding to a hormone ligand.3 Steroidal ligands diffuse or are transported across the cell membrane and bind to intracellular receptors leading to gene regulation.3 Despite the wide diversity of steroidal ligands, there are 48 known human nuclear receptors which are structurally similar with five functional protein domains.1,2 The DNA-binding and ligand-binding domains are the most highly conserved.3 Steroid receptors in subgroup 3 of the nuclear receptor superfamily include estrogen, progesterone, androgen, mineralocorticoid, and glucocorticoid receptors.1

The understanding of steroid receptor structure and function has grown significantly through research and technological advancements and has laid the groundwork for the development of synthetic ligands, therapeutics, and targeted imaging agents.4 Two members of this subfamily, estrogen and progesterone receptors, are key prognostic and predictive biomarkers used clinically in breast cancer and are the focus of this review.5 More recently, the androgen receptor (AR) has been gaining recognition, particularly in triple-negative breast cancer as another potential therapeutic target with longstanding evidence of the benefit of AR targeting in prostate cancer.5–7 This review highlights the research and clinical advances of molecular imaging for breast cancer with radioligands for estrogen, progesterone, and androgen receptors.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer type in females (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) and is second in cancer-related deaths for females.8 Since 2000, the incidence of breast cancer in females has grown annually by approximately 0.5%.8 Advancements in screening mammography have allowed for earlier detection and treatment of breast cancer.9 In certain subsets of patients with breast cancer, positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT), CT, and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has the potential to improve clinical management.10–13

2-Deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose (FDG) is the most common radiopharmaceutical used for PET imaging in advanced stage breast cancer.12 This modality can be used for staging in patients with known stage IIIA or higher disease, locally advanced disease, or inflammatory breast cancer as well as for monitoring response to therapy and detecting recurrence.14,15 FDG is a glucose analogue that enters the cell via facilitated diffusion and is trapped after phosphorylation by hexokinase.16 Many cancers, including breast, upregulate glucose metabolism which is useful for molecular imaging with FDG.17,18 FDG PET imaging is not without limitations; for example, false positives can be seen in infectious and inflammatory processes and false negatives can be seen with small lesions (less than 1 cm) and slow growing or well differentiated tumors (such as ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive lobular carcinomas).19,20 In addition, FDG PET is unable to identify the hormone receptor status of the tumor.21,22

Estrogen Receptor (ER)-Targeted Imaging

Estrogen receptor (ER) is highly expressed in most breast cancers (~70%), is routinely assessed by tissue immunohistochemistry, and is used to determine whether endocrine therapy targeting ER function is indicated.23–25 There is evidence of a correlation between ER positivity and clinical benefit of endocrine therapy.26,27 Evaluating whole-body ER positivity in breast cancer metastases, especially in cases that are heterogenous, may help clinicians determine the best candidates for endocrine therapy. Patients with disease that is strongly and homogenously ER-positive may respond better to endocrine therapy compared with those who have heterogeneous ER expression.28–31

16α-[18F]fluoro-17β-estradiol (FES) was the first steroid imaging agent approved by the U.S. Food and Drug administration (FDA) in 2020 under the brand name Cerianna (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA).32 FES is an estrogen analogue which binds to the ER.33,34 FES was approved for use with PET imaging for detecting ER-positive lesions in patients with recurrent or metastatic breast cancer.32 Since approval, clinical use of FES has been increasing but is not widespread.35,36

FES is 17β-estradiol radiolabeled with a Fluorine-18 radioisotope and has a high binding affinity for ER.33,37 Of the two receptor subtypes, FES has a 6.3-fold greater affinity for ERα compared to ERβ.38 The ER must have a functional ligand-binding domain for FES uptake, therefore imaging with this radiopharmaceutical demonstrates both ER protein expression level and binding ability.39 FES PET allows for whole body evaluation of ER-positive breast cancer with reported ranges of sensitivity from 78% to 86% and specificity from 85% to 98%.40,41

Appropriate Use Criteria for FES PET Imaging

In January 2023, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) released appropriate use criteria for FES PET imaging.42 The expert working group evaluated the appropriateness of FES PET for patients with ER-positive breast cancer in 14 specific clinical scenarios (Table 1).42 Four of the 14 scenarios were deemed appropriate.42 Two of the 4 appropriate scenarios for clinical use of FES PET are for “problem solving” such as for detecting ER status when other imaging tests are equivocal or when patients have more than one type of primary malignancy and the metastatic origin is unclear.43–46 In the retrospective study by Boers et al, FES PET solved 87% (87/100) of these types of clinical dilemmas with treatment decisions directly based on the FES PET results in 81 of 87 cases.43 FES PET was also deemed appropriate for assessing ER status in lesions that are difficult to biopsy or when biopsy is nondiagnostic.42 Either the lesion is in a location that is difficult to access (Figure 1) or imposes significant risk to the patient for biopsy, thus a noninvasive means of obtaining ER status would be preferred.40,47–49

Table 1:

SNMMI Appropriate Use Criteria for FES PET Imaging

| Appropriate | Maybe Appropriate | Rarely Appropriate |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Adapted from42

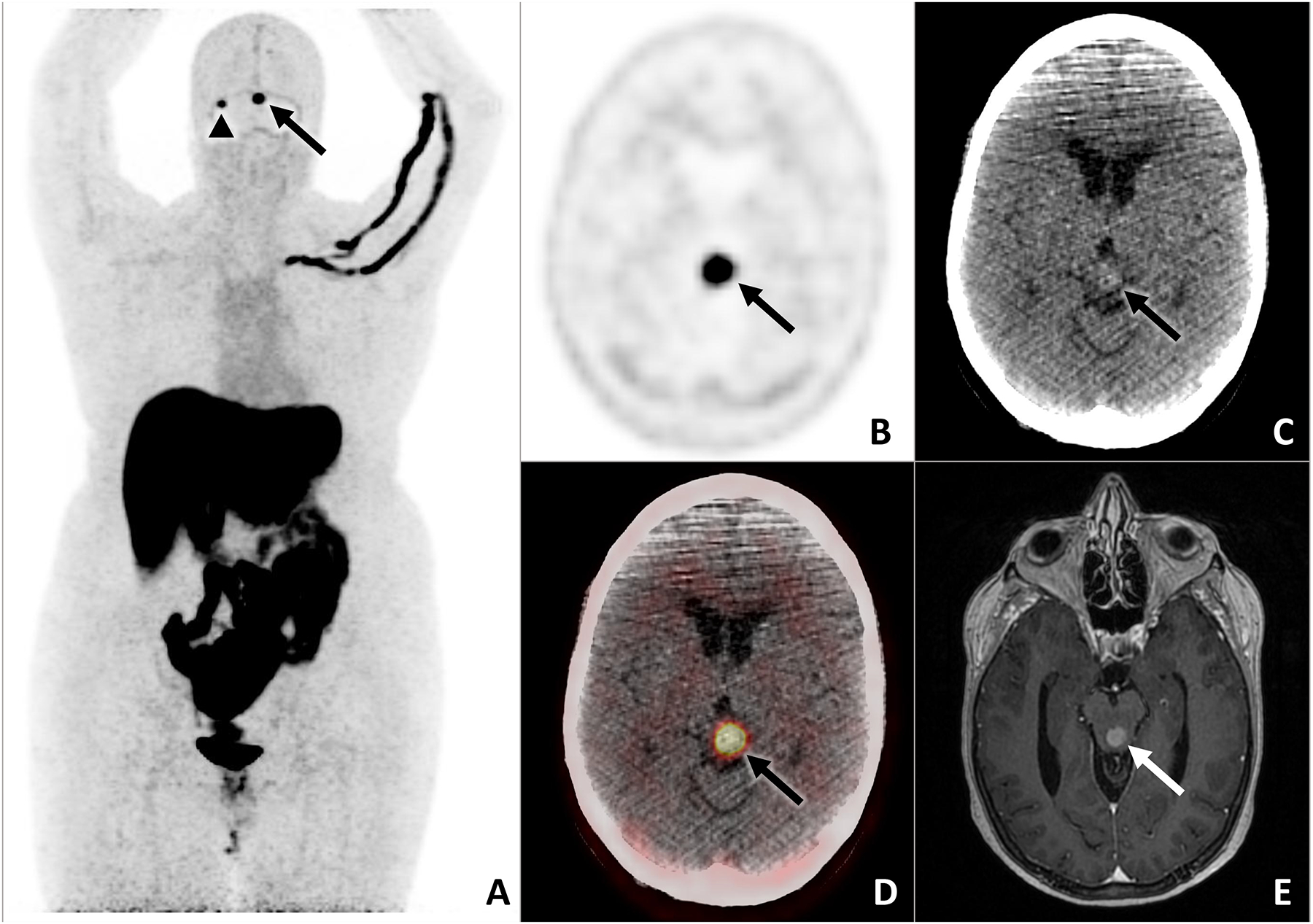

Figure 1:

62-year-old female with history of bilateral invasive breast cancer (ER+/PR+/HER2-) treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, bilateral mastectomy and axillary dissection, adjuvant radiation therapy, and adjuvant endocrine therapy presented with neurologic symptoms and brain MRI lesions suspicious for metastases. Restaging CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and whole-body bone scan were negative for metastases. FES PET/CT was done for problem solving to support the diagnosis of ER-positive intracranial breast cancer metastases given the difficult location for tissue biopsy and also to localize any other potential metastatic sites for biopsy. Left quadrigeminal plate (arrows) and right cerebellum (arrowhead) lesions demonstrate abnormal FES uptake on the maximum intensity projection image (A). The left quadrigeminal plate lesion is also shown on midbrain axial FES PET (B), noncontrast CT (C), fused FES PET/CT (D), and postcontrast T1-weighted MRI (E). Results of the FES PET were used to confirm the treatment plan for first-line endocrine therapy combined with a CDK4/6 inhibitor.

The other two appropriate clinical scenarios for FES PET involve treatment selection for patients with metastatic ER-positive breast cancer. There are multiple therapy options available with differing mechanisms of action; however, resistance to endocrine therapy remains problematic.15,26,50 FES PET was deemed appropriate when selecting first-line endocrine therapy at the initial diagnosis of metastatic disease and when considering second-line endocrine therapy after progression of metastatic disease (Figure 2).42 Multiple studies have shown that FES PET may be a superior biomarker than ER immunohistochemistry for predicting response to endocrine therapies.51–65 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of these studies have reported 78% to 88% negative predictive value of FES PET for treatment response and 45% to 65% positive predictive value based on a threshold SUVmax of 1.5 or 2.0.48,66,67 The majority of these studies included patients previously treated with multiple lines of therapy. The negative predictive value of FES PET for clinical benefit of first-line endocrine therapy for metastatic ER-positive breast cancer was the focus of the recently completed multi-center phase 2 study (NCT 02398773) which will lend further evidence for this clinical scenario.

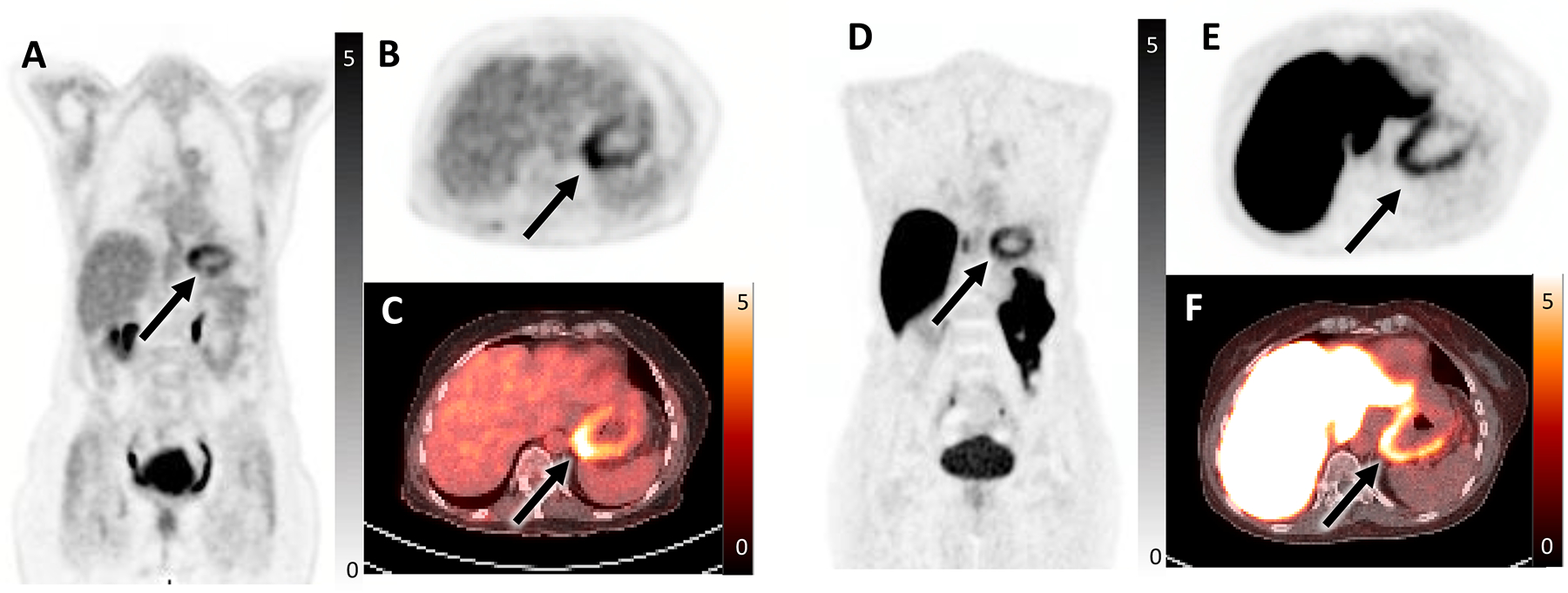

Figure 2:

60-year-old female with history of ER/PR-positive invasive ductal carcinoma of the right breast post lumpectomy, radiation, and endocrine therapy. She developed liver recurrence, initiated therapy with palbociclib and letrozole, and demonstrated partial treatment response on imaging. She then developed nausea and early satiety, underwent endoscopic ultrasound with biopsies, and was found to have metastatic disease to the gastric fundus. FDG PET/CT was performed for re-staging and demonstrated FDG-avid diffuse gastric fundal thickening reflecting biopsy-proven metastasis (SUVmax 5.8, arrow) seen on coronal FDG PET (A), axial FDG PET (B), and axial fused FDG PET/CT (C). Additionally, there was mild uptake in a hepatic metastasis (SUVmax 4, not shown) reflecting partially treated disease. In the setting of metastatic ER-positive breast cancer with progression on first-line endocrine therapy, FES PET/CT was performed. Of note, FES PET/CT can be performed in patients on aromatase inhibitors (such as this patient) without a washout period which is required for patients on SERMs and SERDs. The FES PET/CT demonstrated abnormal FES uptake in the thickened gastric fundus (SUVmax 5.9, arrow) seen on coronal FES PET (D), axial FES PET (E), and axial fused FES PET/CT (F). FES positivity indicated that the patient was a good candidate for second-line endocrine therapy and she was switched to fulvestrant and ribociclib. The hepatic metastasis could not be evaluated on FES PET due to significant liver metabolism of FES, a known limitation of FES PET/CT.

FES PET was categorized as “may be appropriate” for staging invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) and low-grade invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC).42 ILC is a distinct disease process from IDC and makes up approximately 15% of breast malignancies.35 Compared to the more common IDC, ILC has differing genetic, molecular, and pathologic features.68 Due to lack of E-cadherin, ILC grows in a noncohesive single-file linear pattern, which can be difficult to image with mammography, ultrasound, MRI, or FDG PET.69 Both ILC and low-grade IDC are less likely to show distant disease sites with FDG avidity (Figure 3)24,69,70; however, ILC is almost always ER-positive.68,71 Data from small studies support potential utility of FES PET imaging for invasive lobular breast cancer, but more research is needed.36,72,73

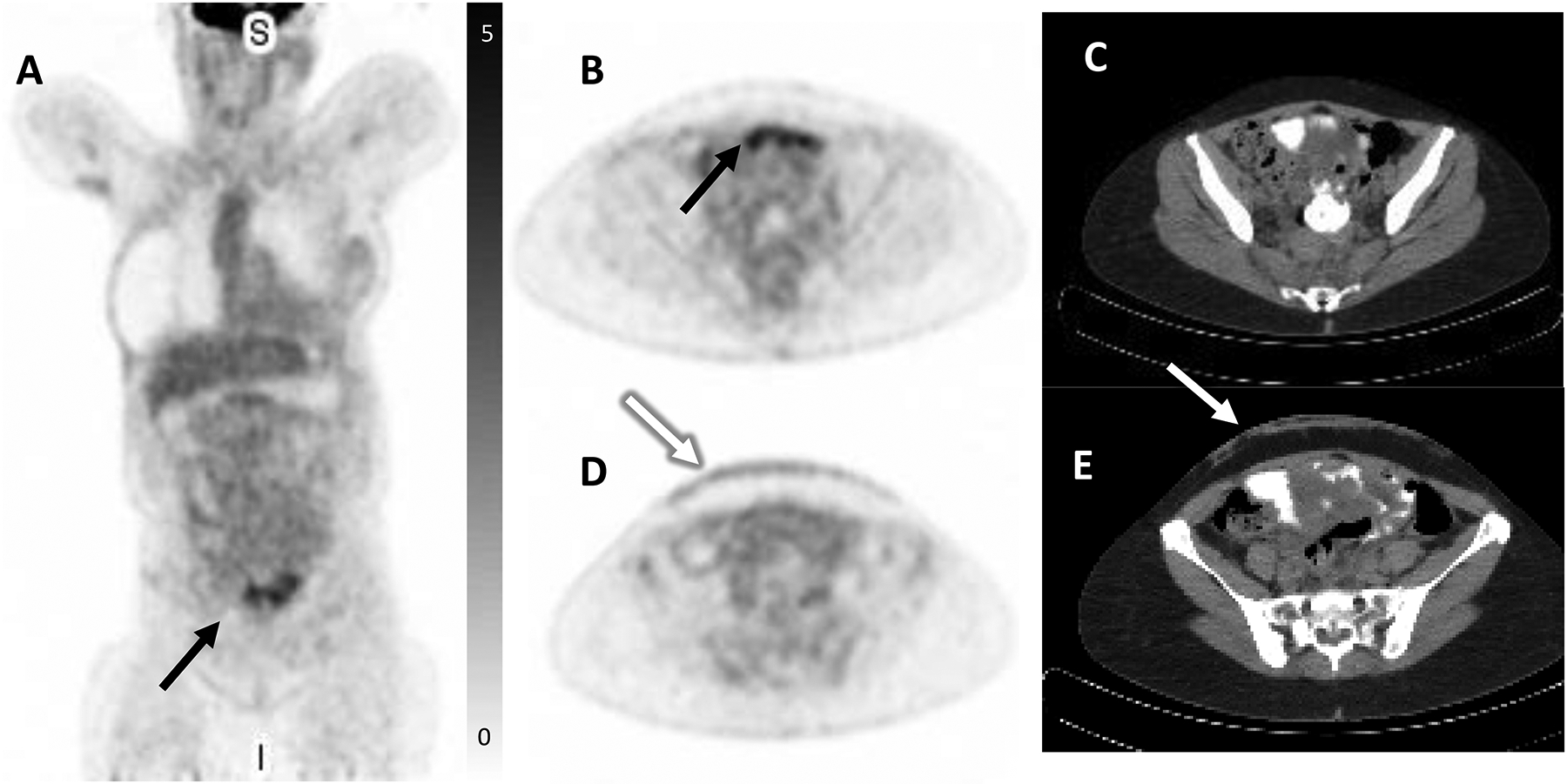

Figure 3:

65-year-old female with history of ER-positive invasive lobular carcinoma of the right breast status post modified mastectomy and axillary dissection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation, and anastrozole endocrine therapy. A skin punch biopsy was performed for diffuse rash which developed while on endocrine therapy and which did not respond to topical therapy, revealing metastatic lobular breast cancer. Restaging FDG PET/CT demonstrated peritoneal thickening with minimal diffuse FDG uptake with one region demonstrating mild focal FDG uptake (SUVmax 4.9, black arrow, A, FDG PET MIP, B, axial PET with corresponding, C, axial CT), suspicious for carcinomatosis. There was also mild radiotracer uptake in the anterior abdominal wall reflecting biopsy-proven metastases (white arrow, SUVmax 1.9, D, axial FDG PET with corresponding, E, axial CT). FES PET/CT was subsequently performed to clarify the extent of disease and demonstrated marked FES-positive diffuse peritoneal carcinomatosis throughout the abdomen and pelvis (SUVmax 14, black arrow, F, coronal FES PET, G, axial FES PET, and corresponding, H, axial CT). Mild radiotracer uptake was again seen in the anterior abdominal wall (white arrow, I, axial FES PET with corresponding, J, axial CT). Additionally, mild FES-avid disease was seen in the bilateral orbits (not shown, initially seen on interval MRI). In the setting of widespread ER-positive metastatic disease which progressed on endocrine therapy, the patient was transitioned to chemotherapy. She unfortunately continued to progress and expired five months later.

Four additional clinical scenarios were assessed as “may be appropriate” for FES PET imaging.42 These include diagnosing malignancy of unknown primary when biopsy is not feasible or is nondiagnostic, assessing ER status in lieu of biopsy in lesions that are easily accessible for biopsy, detecting lesions in patients with suspected or known recurrent or metastatic breast cancer, and routine staging of extraaxillary nodes and distant metastases,.42 Regarding staging, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis consisting of 7 studies and 171 patients was performed to compare the sensitivity of FES and FDG PET/CT for detecting ER-positive breast cancer metastases.74 The authors found similar high pooled sensitivity at the patient level (97% for FDG; 94% for FES).74 FES had slightly better sensitivity at the lesion level (95% for FES; 85% for FDG) and in the subset of studies performed for restaging (98% for FES; 81% for FDG). In a subsequently published study of FDG and FES PET/CT for initial staging of 28 patients with ER-positive breast cancer, overall diagnostic performance was similar with the exception of higher specificity and negative predictive value observed with FES.75 In a subset analysis of strongly ER-positive breast cancer, the accuracy of FES increased from 88% to 95% while the accuracy of FDG decreased from 81% to 70%.75 The authors propose that more accurate staging could be achieved through combined imaging by overcoming the limitations of each tracer.75

Recognizing clinical scenarios for which FES PET was rated “rarely appropriate” is also important as these questions may arise during multidisciplinary care conferences. FES PET is not recommended for diagnosing and routine staging of primary breast cancer (T staging), or routine staging of axillary lymph nodes.42 These situations are best addressed using conventional breast imaging (i.e., mammography, ultrasound, MRI) and tissue biopsy (i.e., percutaneous breast or axillary lymph node biopsy, sentinel lymph node biopsy).

FES PET imaging was also categorized as “rarely appropriate” in two scenarios related to therapy.42 FES PET is appropriate to assess ER binding activity of metastatic lesions but should not be used to assess therapy response as a replacement for FDG or conventional anatomic imaging. This is particularly relevant when patients are being treated with ER-blocking medications since ER-positive lesions may still be present and viable but may not be detectable due to competition between the therapy agent and FES for binding ER. Lastly, there is insufficient evidence to recommend using FES PET to predict response to neoadjuvant therapy, unlike in the situation of metastatic or recurrent ER-positive breast cancer. While small studies have suggested that FES uptake may be a potential biomarker for response to neoadjuvant therapy, more research is needed.76,77

Procedure Standard/Practice Guideline for FES PET Imaging

In June 2023, SNNMI and the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) published a joint procedure standard/practice guideline to promote standardization in FES PET imaging procedures for patients with breast cancer.78 FES is administered intravenously by slow infusion, preferably on the side contralateral to the primary breast cancer, due to its propensity for venous uptake. The recommended injected activity ranges from 3 to 7.6 mCi.79 The typical uptake time is 60 minutes after injection (range 20 to 80 minutes), with no restrictive activities for the patient during this time.79 FES demonstrates rapid uptake in the liver in keeping with usual steroid metabolism.80,81 Hepatic uptake significantly limits evaluation of ER-positive metastases in the liver.40,81,82 FES is then excreted into the biliary system and enters into the small bowel with little activity observed in the colon due to reabsorption and renal excretion.80,81 The patient receives approximately 0.022 mSv/MBq (80 mrem/mCi) effective dose equivalent with the liver receiving the highest dose (0.13 mGy/MBq, 380 mrad/mCi) followed by the gallbladder and urinary bladder.81 These dose levels are considered safe and comparable to other PET imaging agents.81 Unlike with FDG, fasting, dietary restrictions, avoidance of strenuous exercise, and blood glucose measurements are not required prior to FES PET.83

The SNMMI/EANM Procedure Standard/Practice Guideline Interpretation also provides key details on how to appropriately interpret and report the results of FES PET.78 A qualitative visual analysis is typically sufficient for defining FES-positive lesions by identifying increased focal uptake greater than local background that is not related to physiologic uptake or clearance. Thus, it is important to be familiar with the normal biodistribution of FES and recognize expected sites of normal tissue ER expression such as the uterus, ovaries, and pituitary gland.81,84,85 Quantitative analysis of suspected or known sites of disease based on correlative imaging can be performed when visual inspection does not show uptake above local background. A commonly used threshold for defining FES positivity based on correlation with ER immunohistochemistry is an SUVmax greater than or equal to 1.5 for lesions measuring at least 10 mm in size.29,47,86 Thresholds between 1.5 and 2.0 have been used to define FES positivity for predicting response to endocrine therapy.66 Results from the recently completed multi-center phase 2 study (NCT 02398773) will provide further evidence for defining this threshold. Lastly, the guidelines emphasize that correlative imaging with FDG PET, CT, MRI, or bone scintigraphy for defining active sites of disease is critical for interpretation of FES PET to identify ER-negative lesions and evaluate ER heterogeneity that impact prognosis and therapy response.30,59,60,62,87

There are some limitations to be aware of when considering FES PET imaging. Normal circulating estrogens in premenopausal nonpregnant and postmenopausal females do not impact FES distribution; however, medications that interact with the ER binding site may cause a false-negative scan.57,88 For example, tamoxifen, a selective ER modulator (SERM), and fulvestrant, an injectable selective ER degrader (SERD), compete with FES for binding ER, and a washout period of 8 weeks for tamoxifen or 28 weeks for fulvestrant is indicated by FDA guidelines prior to imaging with FES which significantly limits feasibility in clinical practice.79 Oral SERDs, such as elacestrant and rintodestrant, have a much shorter half-life than fulvestrant but more research is needed to establish an appropriate washout period.65,89 Aromatase inhibitors, CDK 4/6 inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors, and oral contraceptives do not impact FES studies.57,78

While FES PET cannot be used clinically in the setting of ER blockers such as SERMs and SERDs, the ability for FES PET to assess ER binding blockade has been used successfully in research.57,65,88,90–94 FES PET before and during fulvestrant determined that standard dosing led to incomplete ER blockade in 38% of patients and that this incomplete blockade was associated with early progression.88 Building on this approach to assess ER availability, FES PET has been used in phase I dose escalation trials to identify the optimal dose of novel SERMs and oral SERDs.

Another limitation is the potential for false-negative and false-positive results which are important to consider during FES PET interpretation. False-negatives can occur in lesions with low-levels of ER expression, lesions in the liver, small bowel, or peritoneal carcinomatosis due to high physiologic clearance, with pleural effusions and ascites, with lesions that are small size (typically less than 1 cm) due to partial volume effects, and with pharmacological treatment with ER-binding medications as discussed above.40,57,82,83,95,96 False-positive findings have been reported with radiation fibrosis/pneumonitis, fibrous dysplasia, insufficiency fractures, meningiomas, and uterine leiomyomas.29,96–103 Despite these limitations, FES PET is a powerful new tool for patients with advanced ER-positive breast cancer.

FES PET has also been used to characterize endometrial carcinoma.104–106 Combined evaluation with both FES and FDG PET has proven the most useful in this patient population – with high glucose metabolism (high FDG uptake) and low ER expression (low FES uptake) seen in aggressive endometrial malignancies and the opposite pattern seen in less aggressive or benign disease.106 In a subsequent study, low FES uptake was an independent prognostic factor associated with poor progression-free and overall survival in patients with endometrial carcinoma.105

PR-Targeted Imaging

The progesterone receptor (PR) is a steroid receptor and tumor biomarker that is routinely assessed in breast cancer using immunohistochemistry.25 PR positivity is observed in about two-thirds of breast cancers, the majority of which are also ER positive.107 Together, ER and PR positivity are predictors of favorable response to endocrine therapy.108–110 ER controls transcription of the gene encoding PR, PGR, as evidenced by increased expression of PR in response to estrogen stimulation and thus, implies a functionally intact ER response.111–113 Loss of PR may predict resistance to therapy with tamoxifen; however, it may not predict resistance to aromatase inhibitors.114 Mounting research suggests a further bi-directional link between ER and PR in cell signaling (i.e., crosstalk)115–117 and PR-targeted therapies have had renewed interest in clinical trials.118,119 Therefore, accurate determination of PR status is clinically significant and may help when selecting an optimal treatment regimen for patients with breast cancer.114,120,121

Multiple PR-targeted positron-emitting radiopharmaceuticals have been developed for imaging since the late 1980s, but translation to clinical use has proved challenging.5,122–130 For example, 21-[18F]fluoro-16α-ethyl-19-norprogesterone (FENP) had promising in vitro and in vivo results during initial preclinical trials.5,122,127 Despite early success, FENP imaging characteristics in patients with breast cancer were problematic due to high levels of nonspecific uptake, noncorrelative tumor uptake compared to tissue PR expression, suboptimal target-to-background uptake ratio, and rapid metabolism.5,124,125 21-[18F]Fluorofuranylnorprogesterone (FFNP) has emerged as the most suitable PR-targeted radiopharmaceutical with high affinity and high selectivity for the receptor in both preclinical and clinical research.5,128,129,131–138

Preclinical studies with FFNP have demonstrated real-time changes in PR expression as a function of ER signaling and predictor of endocrine sensitivity.133,134,136,137 For example, PR expression increased in endocrine-sensitive ER-positive, PR-positive T47D human breast cancer cells and tumor xenografts after estradiol stimulation for a few days.136 Conversely when estrogen was decreased in mice after ovariectomy or with fulvestrant treatment, PR expression quickly decreased as demonstrated by less FFNP uptake in STAT1-deficient mouse mammary tumors.133,137 These dynamic changes in FFNP uptake occurred in endocrine-sensitive ER-positive, PR-positive STAT1-deficient tumors, but not in endocrine-resistant tumors, and occurred prior to changes in tumor size, supporting a role for FFNP PET as an approach for assessing early tumor responsiveness to endocrine therapy.133,137 Another study demonstrated the ability of FFNP PET to predict endocrine resistance in tumor xenografts with activating mutations in the ESR1 gene. Overall, these preclinical studies have demonstrated that imaging early molecular changes in PR expression using FFNP PET can predict endocrine sensitivity.

Results in clinical trials have aligned with the preclinical studies, and FFNP has been shown to be safe for use in humans.131,132,138 In 2012, the “first-in-human” trial of FFNP PET/CT with 20 patients with breast cancer reported no adverse events and a radiation exposure comparable to current PET radiopharmaceuticals being used in clinical practice.131 The study showed peak FFNP uptake in the tumor within a few minutes after injection that was sustained through 60 minutes without significant washout.131 Higher FFNP uptake was observed in PR-positive tumors compared to PR-negative tumors when uptake was corrected for normal breast tissue.131 Preliminary results from a separate ongoing research study also indicate correlation of FFNP uptake measured using breast PET/MRI and PR expression by immunohistochemistry in newly diagnosed primary invasive ductal carcinoma.138 Investigation of FFNP PET/CT as an early biomarker for endocrine therapy response was performed as a single-center, phase 2 study of 43 postmenopausal women with advanced and metastatic ER-positive breast cancer.132 This study found that an increase in tumor FFNP uptake by at least 7% after one day administration of 6 mg oral estradiol predicted clinical benefit from endocrine therapy for at least 6 months with 100% specificity and sensitivity (Figures 4 and 5).132 With a median follow-up of 27 months, subjects who experienced an increase in tumor FFNP uptake by at least 7% after the estradiol-challenge had longer overall survival compared to those with tumor SUV change less than 7%.132 Thus, FFNP PET has been demonstrated to be a safe, noninvasive method for determining tumor PR expression and that dynamic quantitative changes in FFNP uptake can predict endocrine therapy benefit and survival in patients with advanced ER-positive breast cancer.

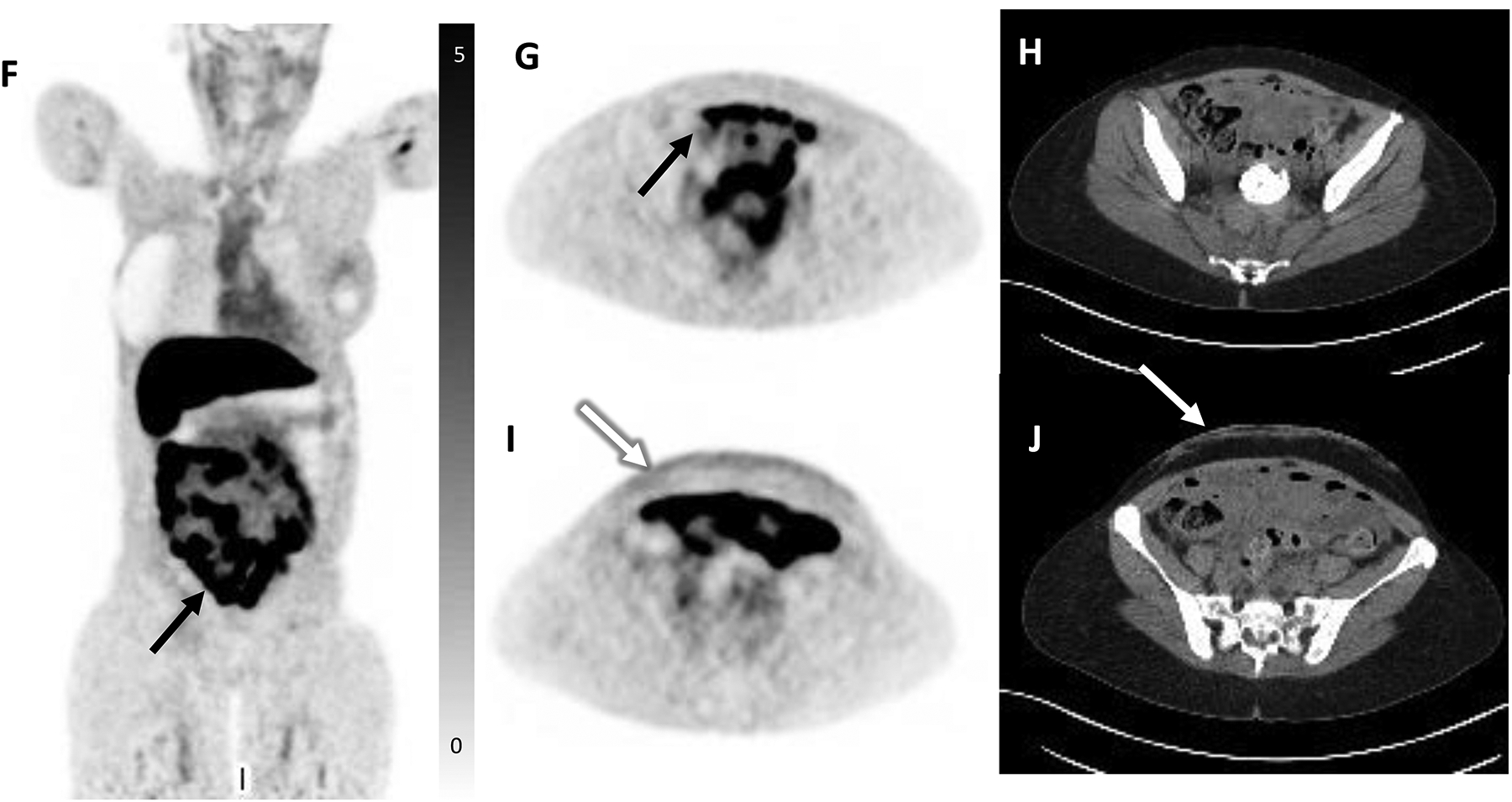

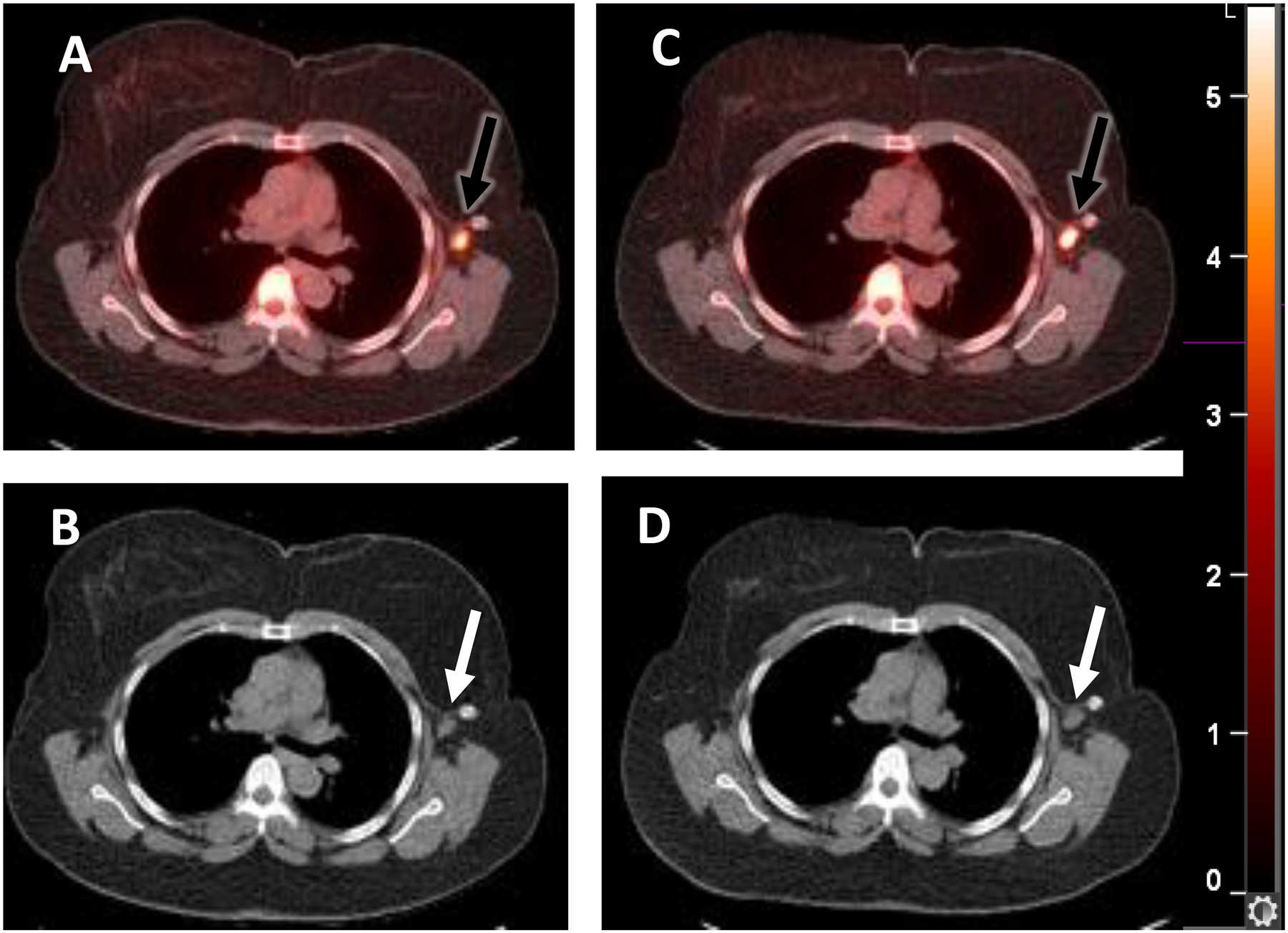

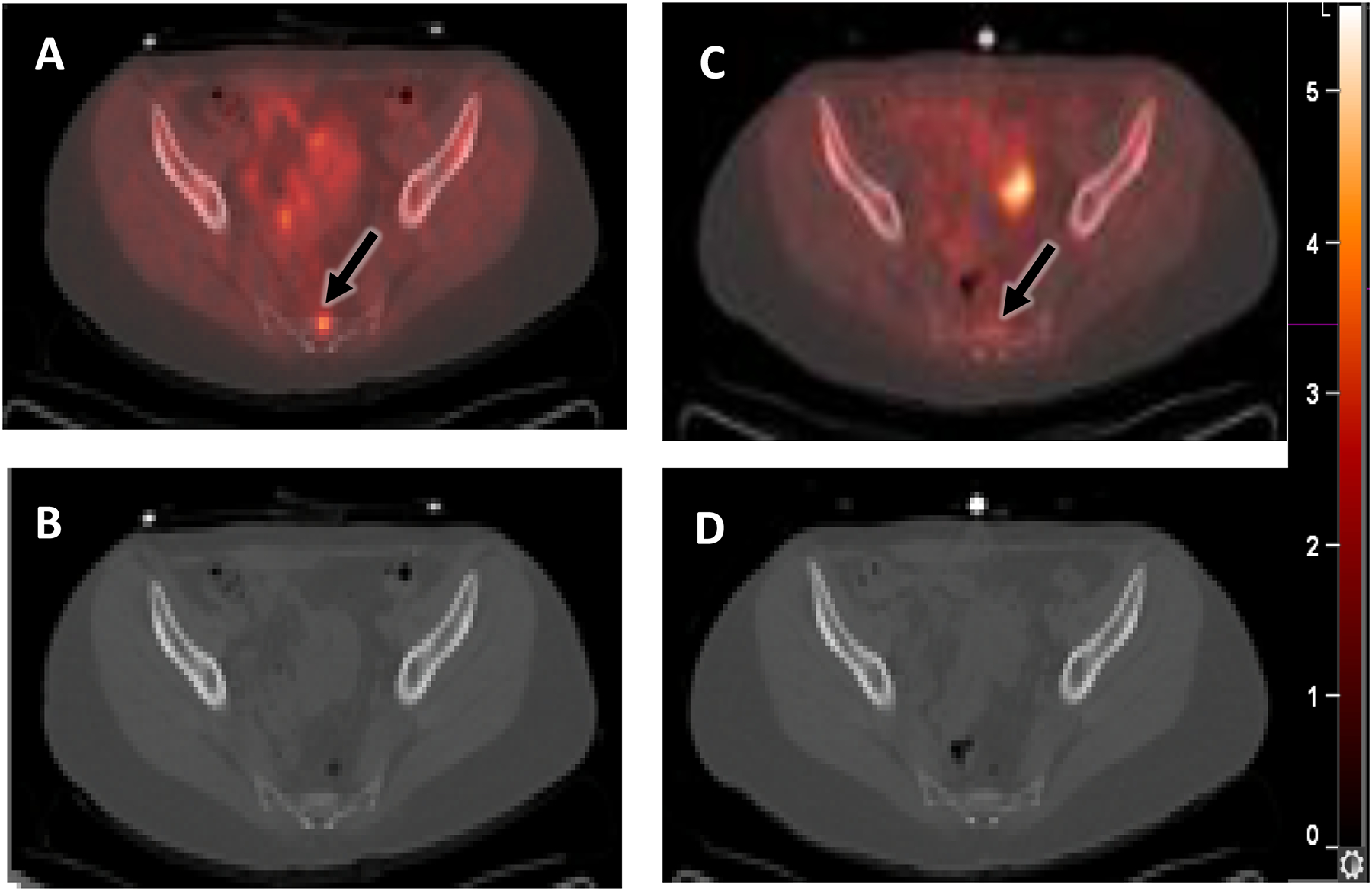

Figure 4:

A woman with newly diagnosed ER+/PR+/HER2- invasive ductal carcinoma with metastatic disease at diagnosis in left axillary lymph nodes. She was treated with an aromatase inhibitor and palbociclib after an estradiol challenge test132 and had marked improvement of all lesions. Selected fused transaxial 21-[18F]fluorofuranylnorprogesterone [FFNP]-PET/CT (A) and CT (B) images at baseline show moderate FFNP uptake (SUVmax 6.8) in a left axillary lymph node metastasis (arrows). (C, D) One day after estradiol, the tumor FFNP uptake (SUVmax 8.8) (arrows) was increased by 29% from baseline. Clinical response was observed at six months.

Figure 5:

A woman with ER+/PR-/HER2- invasive ductal carcinoma status post neoadjuvant endocrine therapy and breast conserving surgery, who developed progression of osseous metastatic disease. She had been previously treated with an aromatase inhibitor, tamoxifen, palbociclib, and mTOR kinase inhibitors. She was treated with an aromatase inhibitor and palbociclib after the estradiol challenge test132 but developed progressive disease. Selected fused transaxial FFNP-PET/CT (A) and CT (B) images at baseline show mild FFNP uptake (SUVmax 4.2) in the sacral metastasis (arrow). (C, D) There was no increase in tumor FFNP uptake (SUVmax 2.3) (arrow) one day after estradiol. Clinical non-response was observed at six months.

Further research is needed before FFNP is ready for clinical practice. FFNP is not yet approved by the FDA and is not commercially available, thus must be produced locally.139,140 Like FES, FFNP undergoes normal hepatic metabolism that results in intense background activity making identification and evaluation of liver metastases challenging. Non-steroidal PR-targeted radiopharmaceuticals may help address this issue, however no “first-in-human” data is available.141 Other 18F-radiolabeled progestins have been developed and tested in preclinical models with variable success but these agents have not yet been evaluated in human subjects.141–145

AR-Targeted Imaging

The androgen receptor (AR) is a steroid receptor expressed in various tissues in males and females, including the breasts, and has important implications in prostate and breast cancer.146–148 AR is abundantly expressed in breast cancer -- approximately 70% of all primary breast cancers, 75% to 95% in ER-positive disease, and 10% to 35% in triple-negative (ER-negative, PR-negative, and HER2-neagative) disease demonstrate AR positivity.146,149–152 Patients with AR-positive breast cancer have a better prognosis compared to AR-negative breast cancer.151 However, AR status is not a helpful biomarker for selection of conventional endocrine therapy targeting ER.153 AR expression is heterogenous and can change over time especially if on hormone therapy, much like ER.154 Immunohistochemical testing for AR expression in breast cancer is not routinely performed in clinical practice and there are currently no standardized guidelines from the College of American Pathologists. Furthermore, a cut-off value for AR positivity by immunohistochemistry has not been standardized.6,151,155 Unlike prostate cancer, the clinical utility of AR as a therapeutic biomarker for breast cancer is less clear with AR antagonists remaining in clinical trials.

Noninvasive PET imaging of AR expression has shown some utility in identifying breast cancer subtype, disease extent, tumor heterogeneity, and potential for patient benefit from AR-targeted therapy, but this approach remains investigational.154,156 Testosterone, an androgen, is converted to 17β-estradiol or dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in breast tissue.151 For AR imaging, 16β−18F-fluoro-5α-dihydrotestosterone (FDHT), a radiolabeled analogue of 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT), has shown some encouraging results with a few drawbacks.5,120,148 FDHT has been more widely studied in prostate cancer focusing on metastatic staging and response to antiandrogen therapy in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).157–159 This research demonstrated that FDHT detected 78% to 86% of known prostate cancer metastases.158,159 FDHT is rapidly metabolized, and its metabolites persist due to an affinity for blood proteins, resulting in high background uptake.5,160 Despite this limitation, some studies have shown high repeatability and interobserver reproducibility of FDHT PET imaging for patients with mCRPC.161

In breast tissue, 17β-estradiol activates cell proliferation while DHT inhibits it. AR stimulation can inhibit ER-positive breast cancer tumor growth but can stimulate ER-negative tumor growth.151,156,162,163 Therefore, it was anticipated that FDHT would be able to identify patients with metastatic breast cancer who would respond to AR-targeted therapy; however, clinical trial results have been variable thus far.164,165 A pilot study of 11 women with ER-positive metastatic breast cancer showed that FDHT PET may be a potential biomarker for response to GTx-024, a novel oral nonsteroidal selective AR modulator.165 In contrast, a feasibility study evaluating 21 patients with AR-positive metastatic breast cancer imaged with serial FDHT PET failed to predict responders from nonresponders on antiandrogen bicalutamide therapy.164 This shortcoming is likely due to a similar issue found in FDHT imaging of prostate cancer; it is hypothesized that AR therapy is blocking bioavailable AR and a decrease on imaging does not necessarily correlate with treatment response.120,158

Additional FDHT studies in patients with breast cancer have failed to show strong reader agreement. A prospective study with ten patients with ER-positive metastatic breast cancer imaged with both FES PET/CT and FDHT PET/CT showed high interobserver agreement for visual evaluation of FES and relatively low interobserver agreement for FDHT based on visual analysis due to low tumor-to-background ratios.162 However, both radiopharmaceuticals showed good quantitative agreement between readers.162

Other ligands, such as enzalutamide, an AR antagonist used in prostate cancer hormone therapy, are being considered for radiolabeling to improve metabolic stability and binding affinity.166 There may be potential for 18F-enzalutamide to enhance signal-to-noise on imaging, but more data is needed.

Summary

Through diligent research and advancements in technology, knowledge has substantially increased regarding breast cancer-related steroid receptor structure and function, pathophysiology, targeting with endocrine therapy, and molecular imaging with radiopharmaceuticals. FES is currently the most clinically validated ER-targeted radioligand and is FDA approved for imaging patients with ER-positive breast cancer. The SNNMI recently released appropriate use criteria and practice guidelines for recommending, ordering, and interpreting FES PET. Significant progress has also been made for imaging PR expression with FFNP in the last decade and clinical trial results have been encouraging. FFNP is considered clinically safe and changes in PR dynamics, as detected on imaging, are highly predictive of endocrine therapy success and overall survival in patients with advanced ER-positive breast cancer. FFNP is not currently FDA approved for clinical use. There is limited data on FDHT for AR imaging in breast cancer. FDHT is also not currently FDA approved and availability of both FFNP and FDHT is limited. Finally, there currently are no companion targeted radioligand therapies available for ER, PR, or AR. Continued innovations in steroid receptor imaging could lead to therapy breakthroughs via development of novel targeted endocrine therapeutics and theranostics to improve clinical care for patients with breast cancer.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Kelley Salem, PhD for assistance with figures. We also acknowledge the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA014520 and the Department of Radiology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health for support.

Funding information:

University of Wisconsin: R01 CA272571 and the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA014520. Washington University School of Medicine: R01 CA195450 and by a grant from the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center/Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation (supported in part by NCI Grant P30 CA91842).

Disclosure summary:

QK has no disclosures. AMF receives book chapter royalty from Elsevier, Inc and has served on an advisory board for GE Healthcare. The Department of Radiology at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health receives research support from GE Healthcare. SRO is a consultant for GE Healthcare. FD has served on an advisory board for GE Healthcare and Trevarx Biomedical, Inc.

References

- 1.Weikum ER, Liu X, Ortlund EA. The nuclear receptor superfamily: A structural perspective. Protein Sci 2018;27:1876–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frigo DE, Bondesson M, Williams C. Nuclear receptors: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutics. Essays Biochem 2021;65:847–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bain DL, Heneghan AF, Connaghan-Jones KD, Miura MT. Nuclear receptor structure: implications for function. Annu Rev Physiol 2007;69:201–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao L, Zhou S, Gustafsson J. Nuclear receptors: recent drug discovery for cancer therapies. Endocr Rev 2019;40:1207–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katzenellenbogen JA. PET imaging agents (FES, FFNP, and FDHT) for estrogen, androgen, and progesterone receptors to improve management of breast and prostate cancers by functional imaging. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safarpour D, Tavassoli FA. A targetable androgen receptor-positive breast cancer subtype hidden among the triple-negative cancers. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2015;139:612–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leo J, Dondossola E, Basham KJ, et al. Stranger Things: New Roles and Opportunities for Androgen Receptor in Oncology Beyond Prostate Cancer. Endocrinology 2023;164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin 2023;73:17–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gegios AR, Peterson MS, Fowler AM. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis: Recent Advances in Imaging and Current Limitations. PET Clin 2023;18:459–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groheux D Breast Cancer Systemic Staging (Comparison of Computed Tomography, Bone Scan, and 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose PET/Computed Tomography). PET Clin 2023;18:503–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cecil K, Huppert L, Mukhtar R, et al. Metabolic Positron Emission Tomography in Breast Cancer. PET Clin 2023;18:473–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fowler AM, Cho SY. PET imaging for breast cancer. Radiol Clin North Am 2021;59:725–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fowler AM, Strigel RM. Clinical advances in PET-MRI for breast cancer. Lancet Oncol 2022;23:e32–e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ulaner GA. PET/CT for patients with breast cancer: where is the clinical impact? AJR Am J Roentgenol 2019;213:254–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gradishar WJ, Moran MS, Abraham J, et al. Breast Cancer, Version 3.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2022;20:691–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salas JR, Clark PM. Signaling pathways that drive (18)F-FDG accumulation in cancer. J Nucl Med 2022;63:659–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Upadhyay M, Samal J, Kandpal M, Singh OV, Vivekanandan P. The Warburg effect: insights from the past decade. Pharmacol Ther 2013;137:318–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wahl RL, Cody RL, Hutchins GD, Mudgett EE. Primary and metastatic breast carcinoma: initial clinical evaluation with PET with the radiolabeled glucose analogue 2-[F-18]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose. Radiology 1991;179:765–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groheux D, Giacchetti S, Moretti JL, et al. Correlation of high 18F-FDG uptake to clinical, pathological and biological prognostic factors in breast cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011;38:426–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen DL, Greenwood HI, Rahbar H, Grimm LJ. Evolving Treatment Paradigms for Low-Risk Ductal Carcinoma In Situ: Imaging Needs. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iqbal R, Mammatas LH, Aras T, et al. Diagnostic performance of [(18)F]FDG PET in staging grade 1–2, estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11:1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dehdashti F, Mortimer JE, Siegel BA, et al. Positron tomographic assessment of estrogen receptors in breast cancer: comparison with FDG-PET and in vitro receptor assays. J Nucl Med 1995;36:1766–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang KT, Kim J, Jung J, et al. Impact of breast cancer subtypes on prognosis of women with operable invasive breast cancer: a population-based study using SEER database. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:1970–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roy M, Fowler AM, Ulaner GA, Mahajan A. Molecular Classification of Breast Cancer. PET Clin 2023;18:441–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allison KH, Hammond MEH, Dowsett M, et al. Estrogen and progesterone receptor testing in breast cancer: ASCO/CAP guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:1346–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tryfonidis K, Zardavas D, Katzenellenbogen BS, Piccart M. Endocrine treatment in breast cancer: cure, resistance and beyond. Cancer Treat Rev 2016;50:68–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harvey JM, Clark GM, Osborne CK, Allred DC. Estrogen receptor status by immunohistochemistry is superior to the ligand-binding assay for predicting response to adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer J Clin Oncol 1999;17 1474–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boers J, de Vries EFJ, Glaudemans A, Hospers GAP, Schröder CP. Application of PET Tracers in Molecular Imaging for Breast Cancer. Curr Oncol Rep 2020;22:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nienhuis HH, van Kruchten M, Elias SG, et al. (18)F-fluoroestradiol tumor uptake is heterogeneous and influenced by site of metastasis in breast cancer patients. J Nucl Med 2018;59:1212–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu C, Hu S, Xu X, et al. Evaluation of tumour heterogeneity by (18)F-fluoroestradiol PET as a predictive measure in breast cancer patients receiving palbociclib combined with endocrine treatment. Breast Cancer Res 2022;24:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ulaner GA. 16α−18F-fluoro-17β-Fluoroestradiol (FES): clinical applications for patients with breast cancer. Semin Nucl Med 2022;52:574–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.US Food and Drug Administration. Drug Trial Snapshot: CERIANNA. (Accessed Accessed December 1, 2023, at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/drug-trial-snapshot-cerianna.)

- 33.Kiesewetter DO, Kilbourn MR, Landvatter SW, Heiman DF, Katzenellenbogen JA, Welch MJ. Preparation of four fluorine- 18-labeled estrogens and their selective uptakes in target tissues of immature rats. J Nucl Med 1984;25:1212–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katzenellenbogen JA. The quest for improving the management of breast cancer by functional imaging: The discovery and development of 16alpha-[(18)F]fluoroestradiol (FES), a PET radiotracer for the estrogen receptor, a historical review. Nucl Med Biol 2021;92:24–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ulaner GA, Fowler AM, Clark AS, Linden H. Estrogen Receptor-Targeted and Progesterone Receptor-Targeted PET for Patients with Breast Cancer. PET Clin 2023;18:531–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Covington MF, O’Brien SR, Lawhn-Heath C, et al. Fluorine-18-Labeled Fluoroestradiol PET/CT: Current Status, Gaps in Knowledge, and Controversies-AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tewson TJ, Mankoff DA, Peterson LM, Woo I, Petra P. Interactions of 16alpha-[18F]-fluoroestradiol (FES) with sex steroid binding protein (SBP). Nucl Med Biol 1999;26:905–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoo J, Dence CS, Sharp TL, Katzenellenbogen JA, Welch MJ. Synthesis of an estrogen receptor beta-selective radioligand: 5-[18F]fluoro-(2R,3S)-2,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)pentanenitrile and comparison of in vivo distribution with 16alpha-[18F]fluoro-17beta-estradiol. J Med Chem 2005;48:6366–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salem K, Kumar M, Powers GL, et al. (18)F-16alpha-17beta-fluoroestradiol binding specificity in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Radiology 2018;286:856–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kurland BF, Wiggins JR, Coche A, et al. Whole-body characterization of estrogen receptor status in metastatic breast cancer with 16alpha-18F-fluoro-17beta-estradiol positron emission tomography: meta-analysis and recommendations for integration into clinical applications. Oncologist 2020;25:835–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mo JA. Safety and Effectiveness of F-18 Fluoroestradiol Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Korean Med Sci 2021;36:e271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ulaner GA, Mankoff DA, Clark AS, et al. Summary: Appropriate Use Criteria for Estrogen Receptor-Targeted PET Imaging with 16α-(18)F-Fluoro-17β-Fluoroestradiol. J Nucl Med 2023;64:351–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boers J, Loudini N, Brunsch CL, et al. Value of (18)F-FES PET in solving clinical dilemmas in breast cancer patients: a retrospective study. J Nucl Med 2021;62:1214–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Kruchten M, Glaudemans AW, de Vries EF, et al. PET imaging of estrogen receptors as a diagnostic tool for breast cancer patients presenting with a clinical dilemma. J Nucl Med 2012;53:182–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Z, Xie Y, Liu C, et al. The clinical value of (18)F-fluoroestradiol in assisting individualized treatment decision in dual primary malignancies. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2021;11:3956–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu C, Gong C, Liu S, et al. (18)F-FES PET/CT Influences the Staging and Management of Patients with Newly Diagnosed Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: A Retrospective Comparative Study with (18)F-FDG PET/CT. Oncologist 2019;24:e1277–e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chae SY, Ahn SH, Kim SB, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and safety of 16alpha-[(18)F]fluoro-17beta-oestradiol PET-CT for the assessment of oestrogen receptor status in recurrent or metastatic lesions in patients with breast cancer: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:546–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Kruchten M, de Vries EG, Brown M, et al. PET imaging of oestrogen receptors in patients with breast cancer. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:e465–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Geel JJL, Boers J, Elias SG, et al. Clinical Validity of 16α-[(18)F]Fluoro-17β-Estradiol Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography to Assess Estrogen Receptor Status in Newly Diagnosed Metastatic Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2022;40:3642–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haines CN, Wardell SE, McDonnell DP. Current and emerging estrogen receptor-targeted therapies for the treatment of breast cancer. Essays Biochem 2021;65:985–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dehdashti F, Mortimer JE, Trinkaus K, et al. PET-based estradiol challenge as a predictive biomarker of response to endocrine therapy in women with estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;113:509–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dehdashti F, Flanagan FL, Mortimer JE, Katzenellenbogen JA, Welch MJ, Siegel BA. Positron emission tomographic assessment of “metabolic flare” to predict response of metastatic breast cancer to antiestrogen therapy. Eur J Nucl Med 1999;26:51–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mortimer JE, Dehdashti F, Siegel BA, Trinkaus K, Katzenellenbogen JA, Welch MJ. Metabolic flare: indicator of hormone responsiveness in advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:2797–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mortimer JE, Dehdashti F, Siegel BA, Katzenellenbogen JA, Fracasso P, Welch MJ. Positron emission tomography with 2-[18F]Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose and 16alpha-[18F]fluoro-17beta-estradiol in breast cancer: correlation with estrogen receptor status and response to systemic therapy. Clin Cancer Res 1996;2:933–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Kruchten M, Glaudemans A, de Vries EFJ, Schroder CP, de Vries EGE, Hospers GAP. Positron emission tomography of tumour [(18)F]fluoroestradiol uptake in patients with acquired hormone-resistant metastatic breast cancer prior to oestradiol therapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2015;42:1674–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Linden HM, Stekhova SA, Link JM, et al. Quantitative fluoroestradiol positron emission tomography imaging predicts response to endocrine treatment in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2793–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Linden HM, Kurland BF, Peterson LM, et al. Fluoroestradiol positron emission tomography reveals differences in pharmacodynamics of aromatase inhibitors, tamoxifen, and fulvestrant in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:4799–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peterson LM, Kurland BF, Schubert EK, et al. A phase 2 study of 16alpha-[18F]-fluoro-17beta-estradiol positron emission tomography (FES-PET) as a marker of hormone sensitivity in metastatic breast cancer (MBC). Mol Imaging Biol 2014;16:431–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kurland BF, Peterson LM, Lee JH, et al. Estrogen receptor binding (18F-FES PET) and glycolytic activity (18F-FDG PET) predict progression-free survival on endocrine therapy in patients with ER+ breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:407–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boers J, Venema CM, de Vries EFJ, et al. Molecular imaging to identify patients with metastatic breast cancer who benefit from endocrine treatment combined with cyclin-dependent kinase inhibition. Eur J Cancer 2020;126:11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.He M, Liu C, Shi Q, et al. The Predictive Value of Early Changes in (18) F-Fluoroestradiol Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography During Fulvestrant 500 mg Therapy in Patients with Estrogen Receptor-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. Oncologist 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu C, Xu X, Yuan H, et al. Dual Tracers of 16α-[18F]fluoro-17β-Estradiol and [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose for Prediction of Progression-Free Survival After Fulvestrant Therapy in Patients With HR+/HER2- Metastatic Breast Cancer. Front Oncol 2020;10:580277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peterson LM, Kurland BF, Yan F, et al. (18)F-Fluoroestradiol PET Imaging in a Phase II Trial of Vorinostat to Restore Endocrine Sensitivity in ER+/HER2- Metastatic Breast Cancer. J Nucl Med 2021;62:184–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Su Y, Zhang Y, Hua X, et al. High-dose tamoxifen in high-hormone-receptor-expressing advanced breast cancer patients: a phase II pilot study. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2021;13:1758835921993436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Iqbal R, Yaqub M, Bektas HO, et al. [18F]FDG and [18F]FES PET/CT Imaging as a Biomarker for Therapy Effect in Patients with Metastatic ER+ Breast Cancer Undergoing Treatment with Rintodestrant. Clin Cancer Res 2023;29:2075–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Evangelista L, Guarneri V, Conte PF. 18F-Fluoroestradiol positron emission tomography in breast cancer patients: systematic review of the literature & meta-analysis. Curr Radiopharm 2016;9:244–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huang YT, Chen TW, Chen LY, Huang YY, Lu YS. The Application of 18 F-FES PET in Clinical Cancer Care : A Systematic Review. Clin Nucl Med 2023;48:785–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ciriello G, Gatza ML, Beck AH, et al. Comprehensive Molecular Portraits of Invasive Lobular Breast Cancer. Cell 2015;163:506–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pereslucha AM, Wenger DM, Morris MF, Aydi ZB. Invasive Lobular Carcinoma: A Review of Imaging Modalities with Special Focus on Pathology Concordance. Healthcare (Basel) 2023;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hogan MP, Goldman DA, Dashevsky B, et al. Comparison of 18F-FDG PET/CT for Systemic Staging of Newly Diagnosed Invasive Lobular Carcinoma Versus Invasive Ductal Carcinoma. J Nucl Med 2015;56:1674–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2000;406:747–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ulaner GA, Jhaveri K, Chandarlapaty S, et al. Head-to-Head Evaluation of (18)F-FES and (18)F-FDG PET/CT in Metastatic Invasive Lobular Breast Cancer. J Nucl Med 2021;62:326–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Covington MF, Hoffman JM, Morton KA, et al. Prospective Pilot Study of (18)F-Fluoroestradiol PET/CT in Patients With Invasive Lobular Carcinomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2023;221:228–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Piccardo A, Fiz F, Treglia G, Bottoni G, Trimboli P. Head-to-head comparison between (18)F-FES PET/CT and (18)F-FDG PET/CT in oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med 2022;11:1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kiatkittikul P, Mayurasakorn S, Promteangtrong C, et al. Head-to-head comparison of (18)F-FDG and (18)F-FES PET/CT for initial staging of ER-positive breast cancer patients. Eur J Hybrid Imaging 2023;7:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Park JH, Kang MJ, Ahn JH, et al. Phase II trial of neoadjuvant letrozole and lapatinib in Asian postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor (ER) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive breast cancer [Neo-ALL-IN]: Highlighting the TILs, ER expressional change after neoadjuvant treatment, and FES-PET as potential significant biomarkers. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2016;78:685–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chae SY, Kim SB, Ahn SH, et al. A randomized feasibility study of (18)F-fluoroestradiol PET to predict pathologic response to neoadjuvant therapy in estrogen receptor-rich postmenopausal breast cancer. J Nucl Med 2017;58:563–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mankoff D, Balogová S, Dunnwald L, et al. Summary: SNMMI Procedure Standard/EANM Practice Guideline for Estrogen Receptor Imaging of Patients with Breast Cancer Using 16α-[(18)F]Fluoro-17β-Estradiol PET. J Nucl Med 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cerianna (fluoroestradiol F 18) injection. Prescribing information. Zionexa US Corp. 2020. (Accessed Accessed December 5, 2023, at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2020/212155Orig1s000lbl.pdf.) [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mankoff DA, Tewson TJ, Eary JF. Analysis of blood clearance and labeled metabolites for the estrogen receptor tracer [F-18]-16 alpha-fluoroestradiol (FES). Nucl Med Biol 1997;24:341–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mankoff DA, Peterson LM, Tewson TJ, et al. [18F]fluoroestradiol radiation dosimetry in human PET studies. J Nucl Med 2001;42:679–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Boers J, Loudini N, de Haas RJ, et al. Analyzing the Estrogen Receptor Status of Liver Metastases with [(18)F]-FES-PET in Patients with Breast Cancer. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Boers J, Giatagana K, Schröder CP, Hospers GAP, de Vries EFJ, Glaudemans A. Image Quality and Interpretation of [(18)F]-FES-PET: Is There any Effect of Food Intake? Diagnostics (Basel) 2020;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Iqbal R, Menke-van der Houven van Oordt CW, Oprea-Lager DE, Booij J. [(18)F]FES uptake in the pituitary gland and white matter of the brain. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2021;48:3009–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tsuchida T, Okazawa H, Mori T, et al. In vivo imaging of estrogen receptor concentration in the endometrium and myometrium using FES PET--influence of menstrual cycle and endogenous estrogen level. Nucl Med Biol 2007;34:205–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.van Geel JJL, Boers J, Elias SG, et al. Clinical validity of 16alpha-[(18)F]fluoro-17beta-estradiol positron emission tomography/computed tomography to assess estrogen receptor status in newly diagnosed metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2022;40:3642–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liu C, Ma G, Zhang J, Cheng J, Yang Z, Song S. (18)F-FES and (18)F-FDG PET/CT imaging as a predictive biomarkers for metastatic breast cancer patients undergoing cyclin-dependent 4/6 kinase inhibitors with endocrine treatment. Ann Nucl Med 2023;37:675–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.van Kruchten M, de Vries EG, Glaudemans AW, et al. Measuring residual estrogen receptor availability during fulvestrant therapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Discov 2015;5:72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Conlan MG, de Vries EFJ, Glaudemans A, Wang Y, Troy S. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Studies of Elacestrant, A Novel Oral Selective Estrogen Receptor Degrader, in Healthy Post-Menopausal Women. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 2020;45:675–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lin FI, Gonzalez EM, Kummar S, et al. Utility of 18F-fluoroestradiol (18F-FES) PET/CT imaging as a pharmacodynamic marker in patients with refractory estrogen receptor-positive solid tumors receiving Z-endoxifen therapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2017;44:500–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang Y, Ayres KL, Goldman DA, et al. 18F-Fluoroestradiol PET/CT measurement of estrogen receptor suppression during a phase I trial of the novel estrogen receptor-targeted therapeutic GDC-0810: using an imaging biomarker to guide drug dosage in subsequent trials. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:3053–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jager A, de Vries EGE, der Houven van Oordt CWM, et al. A phase 1b study evaluating the effect of elacestrant treatment on estrogen receptor availability and estradiol binding to the estrogen receptor in metastatic breast cancer lesions using (18)F-FES PET/CT imaging. Breast Cancer Res 2020;22:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chandarlapaty S, Dickler MN, Perez Fidalgo JA, et al. An Open-label Phase I Study of GDC-0927 in Postmenopausal Women with Locally Advanced or Metastatic Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2023;29:2781–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bardia A, Mayer I, Winer E, et al. The oral selective estrogen receptor degrader GDC-0810 (ARN-810) in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive HER2-negative (HR + /HER2 −) advanced/metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2023;197:319–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chae SY, Son HJ, Lee DY, et al. Comparison of diagnostic sensitivity of [(18)F]fluoroestradiol and [(18)F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography for breast cancer recurrence in patients with a history of estrogen receptor-positive primary breast cancer. EJNMMI Res 2020;10:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McGuire AH, Dehdashti F, Siegel BA, et al. Positron tomographic assessment of 16 alpha-[18F] fluoro-17 beta-estradiol uptake in metastatic breast carcinoma. J Nucl Med 1991;32:1526–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gemignani ML, Patil S, Seshan VE, et al. Feasibility and predictability of perioperative PET and estrogen receptor ligand in patients with invasive breast cancer. J Nucl Med 2013;54:1697–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Moresco RM, Scheithauer BW, Lucignani G, et al. Oestrogen receptors in meningiomas: a correlative PET and immunohistochemical study. Nucl Med Commun 1997;18:606–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yoshida Y, Kiyono Y, Tsujikawa T, Kurokawa T, Okazawa H, Kotsuji F. Additional value of 16α-[18F]fluoro-17β-oestradiol PET for differential diagnosis between uterine sarcoma and leiomyoma in patients with positive or equivocal findings on [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011;38:1824–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pan B, Hao Z, Zhou Y, Sun Q, Huo L. Increased 18 F-Fluoroestradiol Uptake of Radiation Pneumonitis in a Patient With Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin Nucl Med 2023;48:437–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Morel A, Maucherat B, Chiavassa S, Kraeber-Bodéré F, Rousseau C. Long-term Trace of Radiation Pneumonitis With 18F-Fluoroestradiol. Clin Nucl Med 2020;45:e403–e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yang Z, Sun Y, Yao Z, Xue J, Zhang Y, Zhang Y. Increased (18)F-fluoroestradiol uptake in radiation pneumonia. Ann Nucl Med 2013;27:931–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Venema CM, de Vries EFJ, van der Veen SJ, et al. Enhanced pulmonary uptake on (18)F-FES-PET/CT scans after irradiation of the thoracic area: related to fibrosis? EJNMMI Res 2019;9:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tsujikawa T, Makino A, Mori T, et al. PET imaging of estrogen receptors for gynecological tumors. Clin Nucl Med 2022;47:e481–e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yamada S, Tsuyoshi H, Yamamoto M, et al. Prognostic Value of 16alpha-(18)F-Fluoro-17beta-Estradiol PET as a Predictor of Disease Outcome in Endometrial Cancer: A Prospective Study. J Nucl Med 2021;62:636–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tsujikawa T, Yoshida Y, Kudo T, et al. Functional images reflect aggressiveness of endometrial carcinoma: estrogen receptor expression combined with 18F-FDG PET. J Nucl Med 2009;50:1598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Li CI, Daling JR, Malone KE. Incidence of invasive breast cancer by hormone receptor status from 1992 to 1998. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Elledge RM, Green S, Pugh R, et al. Estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PgR), by ligand-binding assay compared with ER, PgR and pS2, by immuno-histochemistry in predicting response to tamoxifen in metastatic breast cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group Study. Int J Cancer 2000;89:111–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sledge GW Jr., McGuire WL. Steroid hormone receptors in human breast cancer. Adv Cancer Res 1983;38:61–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Vollenweider-Zerargui L, Barrelet L, Wong Y, Lemarchand-Beraud T, Gomez F. The predictive value of estrogen and progesterone receptors’ concentrations on the clinical behavior of breast cancer in women. Clinical correlation on 547 patients. Cancer 1986;57:1171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Savouret JF, Bailly A, Misrahi M, et al. Characterization of the hormone responsive element involved in the regulation of the progesterone receptor gene. EMBO J 1991;10:1875–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Read LD, Snider CE, Miller JS, Greene GL, Katzenellenbogen BS. Ligand-modulated regulation of progesterone receptor messenger ribonucleic acid and protein in human breast cancer cell lines. Mol Endocrinol 1988;2:263–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Horwitz KB, Koseki Y, McGuire WL. Estrogen control of progesterone receptor in human breast cancer: role of estradiol and antiestrogen. Endocrinology 1978;103:1742–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Osborne CK, Schiff R, Arpino G, Lee AS, Hilsenbeck VG. Endocrine responsiveness: understanding how progesterone receptor can be used to select endocrine therapy. Breast 2005;14:458–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Daniel AR, Gaviglio AL, Knutson TP, et al. Progesterone receptor-B enhances estrogen responsiveness of breast cancer cells via scaffolding PELP1- and estrogen receptor-containing transcription complexes. Oncogene 2015;34:506–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Singhal H, Greene ME, Tarulli G, et al. Genomic agonism and phenotypic antagonism between estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. Sci Adv 2016;2:e1501924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Mohammed H, Russell IA, Stark R, et al. Progesterone receptor modulates ERalpha action in breast cancer. Nature 2015;523:313–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kamaraju S, Fowler AM, Weil E, et al. Leveraging antiprogestins in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Endocrinology 2021;162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lee O, Sullivan ME, Xu Y, et al. Selective progesterone receptor modulators in early-stage breast cancer: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase II window-of-opportunity trial using telapristone acetate. Clin Cancer Res 2020;26:25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Parent EE, Fowler AM. Nuclear Receptor Imaging In Vivo-Clinical and Research Advances. J Endocr Soc 2023;7:bvac197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Edmonds CE, O’Brien SR, Mankoff DA, Pantel AR. Novel applications of molecular imaging to guide breast cancer therapy. Cancer Imaging 2022;22:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Pomper MG, Katzenellenbogen JA, Welch MJ, Brodack JW, Mathias CJ. 21-[18F]fluoro-16 alpha-ethyl-19-norprogesterone: synthesis and target tissue selective uptake of a progestin receptor based radiotracer for positron emission tomography. J Med Chem 1988;31:1360–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Katzenellenbogen JA, Welch MJ, Dehdashti F. The development of estrogen and progestin radiopharmaceuticals for imaging breast cancer. Anticancer Res 1997;17:1573–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Verhagen A, Studeny M, Luurtsema G, et al. Metabolism of a [18F]fluorine labeled progestin (21-[18F]fluoro-16 alpha-ethyl-19-norprogesterone) in humans: a clue for future investigations. Nucl Med Biol 1994;21:941–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Dehdashti F, McGuire AH, Van Brocklin HF, et al. Assessment of 21-[18F]fluoro-16 alpha-ethyl-19-norprogesterone as a positron-emitting radiopharmaceutical for the detection of progestin receptors in human breast carcinomas. J Nucl Med 1991;32:1532–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Verhagen A, Luurtsema G, Pesser JW, et al. Preclinical evaluation of a positron emitting progestin ([18F]fluoro-16 alpha-methyl-19-norprogesterone) for imaging progesterone receptor positive tumours with positron emission tomography. Cancer Lett 1991;59:125–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Verhagen A, Elsinga PH, de Groot TJ, et al. A fluorine-18 labeled progestin as an imaging agent for progestin receptor positive tumors with positron emission tomography. Cancer Res 1991;51:1930–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Buckman BO, Bonasera TA, Kirschbaum KS, Welch MJ, Katzenellenbogen JA. Fluorine-18-labeled progestin 16 alpha, 17 alpha-dioxolanes: development of high-affinity ligands for the progesterone receptor with high in vivo target site selectivity. J Med Chem 1995;38:328–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Vijaykumar D, Mao W, Kirschbaum KS, Katzenellenbogen JA. An efficient route for the preparation of a 21-fluoro progestin-16 alpha,17 alpha-dioxolane, a high-affinity ligand for PET imaging of the progesterone receptor. J Org Chem 2002;67:4904–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Allott L, Smith G, Aboagye EO, Carroll L. PET imaging of steroid hormone receptor expression. Mol Imaging 2015;14:534–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Dehdashti F, Laforest R, Gao F, et al. Assessment of progesterone receptors in breast carcinoma by PET with 21–18F-fluoro-16alpha,17alpha-[(R)-(1’-alpha-furylmethylidene)dioxy]-19-norpregn- 4-ene-3,20-dione. J Nucl Med 2012;53:363–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Dehdashti F, Wu N, Ma CX, Naughton MJ, Katzenellenbogen JA, Siegel BA. Association of PET-based estradiol-challenge test for breast cancer progesterone receptors with response to endocrine therapy. Nat Commun 2021;12:733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Fowler AM, Chan SR, Sharp TL, et al. Small-animal PET of steroid hormone receptors predicts tumor response to endocrine therapy using a preclinical model of breast cancer. J Nucl Med 2012;53:1119–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kumar M, Salem K, Jeffery JJ, Yan Y, Mahajan AM, Fowler AM. Longitudinal molecular imaging of progesterone receptor reveals early differential response to endocrine therapy in breast cancer with an activating ESR1 mutation. J Nucl Med 2021;62:500–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Salem K, Kumar M, Kloepping KC, Michel CJ, Yan Y, Fowler AM. Determination of binding affinity of molecular imaging agents for steroid hormone receptors in breast cancer. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2018;8:119–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Salem K, Kumar M, Yan Y, et al. Sensitivity and isoform specificity of (18)F-fluorofuranylnorprogesterone for measuring progesterone receptor protein response to estradiol challenge in breast cancer. J Nucl Med 2019;60:220–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Chan SR, Fowler AM, Allen JA, et al. Longitudinal noninvasive imaging of progesterone receptor as a predictive biomarker of tumor responsiveness to estrogen deprivation therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:1063–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Fowler A, Salem K, Henze Bancroft L, et al. Targeting the progesterone receptor in breast cancer using simultaneous FFNP breast PET/MRI: a pilot study. J Nucl Med 2022;63:2589-. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Zhou D, Lin M, Yasui N, et al. Optimization of the preparation of fluorine-18-labeled steroid receptor ligands 16alpha-[18F]fluoroestradiol (FES), [18F]fluoro furanyl norprogesterone (FFNP), and 16beta-[18F]fluoro-5alpha-dihydrotestosterone (FDHT) as radiopharmaceuticals. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm 2014;57:371–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Basuli F, Zhang X, Blackman B, et al. Fluorine-18 labeled fluorofuranylnorprogesterone ([18F]FFNP) and dihydrotestosterone ([18F]FDHT) prepared by “Fluorination on Sep-Pak” method. Molecules 2019;24:2389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Lee JH, Zhou HB, Dence CS, Carlson KE, Welch MJ, Katzenellenbogen JA. Development of [F-18]fluorine-substituted Tanaproget as a progesterone receptor imaging agent for positron emission tomography. Bioconjug Chem 2010;21:1096–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Wu X, You L, Zhang D, et al. Synthesis and preliminary evaluation of a (18) F-labeled ethisterone derivative [(18) F]EAEF for progesterone receptor targeting. Chem Biol Drug Des 2017;89:559–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Gao F, Peng C, Zhuang R, et al. (18)F-labeled ethisterone derivative for progesterone receptor targeted PET imaging of breast cancer. Nucl Med Biol 2019;72–73:62–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Allott L, Miranda C, Hayes A, Raynaud F, Cawthorne C, Smith G. Synthesis of a benzoxazinthione derivative of tanaproget and pharmacological evaluation for PET imaging of PR expression. EJNMMI Radiopharm Chem 2019;4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Merchant S, Allott L, Carroll L, et al. Synthesis and pre-clinical evaluation of a [18F]fluoromethyl-tanaproget derivative for imaging of progesterone receptor expression. RSC Advances 2016;6:57569–79. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Collins LC, Cole KS, Marotti JD, Hu R, Schnitt SJ, Tamimi RM. Androgen receptor expression in breast cancer in relation to molecular phenotype: results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Mod Pathol 2011;24:924–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Filippi L, Urso L, Schillaci O, Evangelista L. [(18)F]-FDHT PET for the Imaging of Androgen Receptor in Prostate and Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Sarikaya I PET receptor imaging in breast cancer. Clinical and Translational Imaging 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 149.Kensler KH, Regan MM, Heng YJ, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of androgen receptor expression in postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: results from the Breast International Group Trial 1–98. Breast Cancer Res 2019;21:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Kraby MR, Valla M, Opdahl S, et al. The prognostic value of androgen receptors in breast cancer subtypes. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018;172:283–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Anestis A, Zoi I, Papavassiliou AG, Karamouzis MV. Androgen Receptor in Breast Cancer-Clinical and Preclinical Research Insights. Molecules 2020;25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Vera-Badillo FE, Templeton AJ, de Gouveia P, et al. Androgen receptor expression and outcomes in early breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106:djt319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Bronte G, Rocca A, Ravaioli S, et al. Androgen receptor in advanced breast cancer: is it useful to predict the efficacy of anti-estrogen therapy? BMC Cancer 2018;18:348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Venema CM, Mammatas LH, Schroder CP, et al. Androgen and estrogen receptor imaging in metastatic breast cancer patients as a surrogate for tissue biopsies. J Nucl Med 2017;58:1906–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Kumar V, Yu J, Phan V, Tudor IC, Peterson A, Uppal H. Androgen Receptor Immunohistochemistry as a Companion Diagnostic Approach to Predict Clinical Response to Enzalutamide in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol 2017;1:1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Venema CM, Bense RD, Steenbruggen TG, et al. Consideration of breast cancer subtype in targeting the androgen receptor. Pharmacol Ther 2019;200:135–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Kairemo K, Hodolic M. Androgen Receptor Imaging in the Management of Hormone-Dependent Cancers with Emphasis on Prostate Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Dehdashti F, Picus J, Michalski JM, et al. Positron tomographic assessment of androgen receptors in prostatic carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2005;32:344–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Larson SM, Morris M, Gunther I, et al. Tumor localization of 16beta-18F-fluoro-5alpha-dihydrotestosterone versus 18F-FDG in patients with progressive, metastatic prostate cancer. J Nucl Med 2004;45:366–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Beattie BJ, Smith-Jones PM, Jhanwar YS, et al. Pharmacokinetic assessment of the uptake of 16beta-18F-fluoro-5alpha-dihydrotestosterone (FDHT) in prostate tumors as measured by PET. J Nucl Med 2010;51:183–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Vargas HA, Kramer GM, Scott AM, et al. Reproducibility and repeatability of semiquantitative (18)F-fluorodihydrotestosterone uptake metrics in castration-resistant prostate cancer metastases: a prospective multicenter study. J Nucl Med 2018;59:1516–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Mammatas LH, Venema CM, Schröder CP, et al. Visual and quantitative evaluation of [(18)F]FES and [(18)F]FDHT PET in patients with metastatic breast cancer: an interobserver variability study. EJNMMI Res 2020;10:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Narayanan R, Dalton JT. Androgen receptor: a complex therapeutic target for breast cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2016;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Boers J, Venema CM, de Vries EFJ, et al. Serial [(18)F]-FDHT-PET to predict bicalutamide efficacy in patients with androgen receptor positive metastatic breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2021;144:151–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Jacene H, Liu M, Cheng SC, et al. Imaging Androgen Receptors in Breast Cancer with (18)F-Fluoro-5alpha-Dihydrotestosterone PET: A Pilot Study. J Nucl Med 2022;63:22–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Antunes IF, Dost RJ, Hoving HD, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of (18)F-enzalutamide, a new radioligand for PET imaging of androgen receptors: a comparison with 16beta-(18)F-fluoro-5alpha-dihydrotestosterone. J Nucl Med 2021;62:1140–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]