Abstract

Background and Objectives

Although the vulnerabilities stemming from the intersection of aging and migration are widely recognized, the migration contexts and the factors influencing the mental health of older unforced migrants have received scant attention. This review explores the drivers of unforced migrations in later life and the individual, relational, and structural factors influencing their mental health and well-being.

Research Design and Methods

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, a systematic search of 7 databases for English peer-reviewed journal articles was conducted. A total of 21 studies were identified and analyzed inductively.

Results

The review classified motivations for migration as push factors and pull factors: push factors such as escaping structural inequities in the homeland and pull factors included seeking better lifestyle opportunities and reuniting with family. The positive determinants of mental health included cordial family relationships, paid employment, the presence of a partner, and strong support networks. Advanced age, absence of a partner, lifestyle changes, lack of intergenerational support, poor language proficiency, unfavorable policies, lack of access to resources, and systemic biases negatively affected the mental health of older unforced migrants.

Discussion and Implications

The review highlights the need to recognize the diversity among older migrants to develop policies and programs that address their specific circumstances. Recognizing their strengths, rather than focusing solely on their vulnerabilities will help create a more positive and supportive environment, enabling them to thrive in their new communities.

Keywords: Caring, Family, Grandparent, Intergenerational, Reunification

The mental health and well-being of older migrants can be significantly influenced by their migration experiences, which are shaped by various social determinants of health (SDH). However, the understanding of the relationship between migration contexts and the factors influencing the mental health of older migrants is limited. One of the reasons for this gap is the lack of research that distinguishes between older migrants and those who migrated young and age in the destination country. Second, the academic discourse on migration is marred by ageism giving most attention to the working-age group (Bastia et al., 2022) due to the prevalent perception that older migrants are merely care recipients who are economic liabilities for the destination country, disregarding the work of those who work or provide primary care to others.

Furthermore, older unforced migrants often receive less attention, as their concerns are considered less urgent when compared to forced migrants who migrate under dire circumstances such as war or persecution. The unforced migrations are perceived to be completely voluntary for social or economic reasons and thus undeserving of state support (Ottonelli & Torresi, 2013).

Neglecting the diversity of migration experiences among older populations could hinder our understanding of their health and well-being needs. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the underlying motivations for migration, their experiences as migrants, and their associations with mental health to ensure the well-being of older unforced migrants.

Such a review is also essential in the context of global population trends as the interconnectedness of the world, driven by globalization, economic policies, and advancements in communication technology, has led to a significant increase in global migration (Czaika & de Haas, 2014; Ji et al., 2022). The number of people residing in a country other than their country of birth has reached 281 million (International Organization for Migration, 2021) out of which about 12.2% (34.3 million) are aged 60 and above, as reported by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs in 2020. Additionally, two thirds of the world’s migrants migrate for reasons other than force (International Organization for Migration, 2021).

The existing data on migration directions, scale, and reasons among older adults are constrained because their migrations are not uniform in structure (Holecki et al., 2020) and are often collated along with data on younger migrants. Typically, most such migrations are from economically disadvantaged to more prosperous nations (Czaika & de Haas, 2014) with Asia being the primary source of long-distance migrants. The volume of such migrations is inversely proportional to periods of economic growth in visa-free corridors, whereas in visa-constrained corridors migration flows are not affected by economic growth cycles (Czaika & de Haas, 2017).

Issues Concerning Older Migrants

Although migration can affect mental health and overall well-being regardless of age (Carney, 2015), older migrants may experience heightened stress when adapting to unfamiliar environments (Jang & Tang, 2021). Difficulties associated with cognitive impairment, frailty, morbidity, social isolation, and dependency add to their adaptation challenges (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2018). Aging also results in decreased adaptive capacities (Slade & Borovnik, 2018), making it more challenging for older adults to learn a new language, and navigate new cultures, places, or environments.

Language barriers are directly linked with limited job opportunities, financial instability, and ineligibility for social security further leading to older migrants becoming dependent on their families (Hadfield, 2014; Treas, 2008; Wu & Penning, 2015). Consequently, they may encounter increased levels of acculturative stress, loneliness, and depression (Guo et al., 2019; Wrobel et al., 2009; Wu & Penning, 2015).

Their skills may not align with those in demand in host nations (Brell et al., 2020) forcing their ongoing poverty, disadvantage, and adaptation challenges. Deteriorating physical health, limited social networks (Brandenberger et al., 2019), and cultural stress (Salas-Wright & Schwartz, 2019) further exacerbate their challenges. Thus, a multitude of factors influence the mental health of older migrants.

The available review studies focusing on the intersection of aging and migration have mainly focused on specific migration patterns or overall aging experiences. There is a need to recognize the diversity among older migrants in terms of their mental health outcomes associated with their migration context and experiences. These outcomes may vary depending on individual factors, such as motivation for migration, country of origin, whether they are reunifying with family, their socioeconomic status, education, and access to resources (Georgeou et al., 2021; Ma & Joshi, 2021; Tang & Zolnikov, 2021; Wang & Lai, 2020). Despite the challenges faced by older migrants, there is relatively little academic research that specifically examines the factors influencing their mental health, unless they form part of larger study populations or are focused on politically exiled populations, people displaced by war, refugees, or asylum seekers.

Thus, this review seeks to understand the contexts in which people 50 years and above migrate for reasons other than life-threatening circumstances such as war, conflict, and the individual, relational, and structural determinants that influence their mental health.

The review is guided by the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition of mental health, which describes it as “a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community. Mental health is an integral component of health and is more than the absence of mental disorder” (WHO, 2022). Mental health encompasses the broad concept of positive affect, which includes positive emotions such as happiness, optimism, gratitude, resilience, and a sense of purpose (Levine et al., 2021). Alternatively, poor mental health manifests through symptoms of emotional distress like depression and anxiety (Drapeau et al., 2012), as opposed to mental illness diagnosed through clinical assessment (Cromby et al., 2013). It is also essential to recognize that experiences are shaped by SDH, which include conditions where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.). The contextual interactions with power at local, national, and global levels play a significant role. Therefore, understanding the mental health of older migrants requires examining the SDH influencing mental health.

Method

The review was conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2015). The process involved developing a research question, devising a search strategy, screening articles, assessing the quality of studies, extracting, and analyzing data, and generating themes for reporting the results. We registered the protocol for this study with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), with the registration number CRD42022359881, to ensure transparency and adherence to best practices in systematic reviews. The protocol has been published (Bhatia et al., 2023).

Eligibility Criteria

We systematically searched for academic peer-reviewed journal articles reporting on quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods research. We included cross-sectional, semi-experimental, or other comparative studies. Our focus was on populations of older adults, or subsamples thereof, who had engaged in unforced migration. To ensure consistency across cultures, we set the age criteria of 50 years and above, following the rationale of Zittoun and Baucal (2021), which acknowledges differences in sociocultural definitions of “older age” across contexts. To ensure the relevance of the studies, we only included articles that reported on the mental health of a relevant population where the migration experience was within 5 years at the time of the study. This was in consideration that negative mental health consequences can be mitigated over time through enhanced cultural adaptation (Xiao et al., 2019).

We specifically focused on studies reporting on the emotional or psychological health of older unforced migrants including concepts such as happiness, optimism, gratitude, resilience, or sense of purpose (Levine et al., 2021), as well as loneliness and life satisfaction. We also considered concepts such as well-being or quality of life because these are inclusive of mental health aspects. Studies focusing on forced migration, due to political exile, war displacement, refugees, or asylum seeking, were excluded.

Search Strategy

To identify potentially relevant journal articles, we used the PICo framework (Lockwood et al., 2015). The components of the PICo framework—population, the phenomenon of interest, and context—enable a comprehensive understanding of the factors that shape human experiences and their contextual influences (Stern et al., 2014). We piloted the search strategy with the CINAHL database, refined it, and adjusted it to meet the search requirements of each database (see Supplementary Material 1).

Systematic searching was conducted in seven electronic databases, including AgeLine, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, CINAHL, Informit, PsycINFO, PubMed, and Web of Science. To ensure relevance, we restricted each search to academic peer-reviewed journal articles reporting on research outcomes rather than academic theorizing. No language, publication date, or country restrictions were applied during the database search.

Potentially eligible journal articles were screened in Covidence (2015) for inclusion. We also conducted citation mining by hand searching the reference lists of studies included and checking Google Scholar for citing authors not captured via the original database searches (Schlosser et al., 2006). The search was completed in November 2022.

Screening

Database searching identified 17,334 potentially eligible items, upon which 2658 were automatically removed when exported to Covidence. The title and abstract screening of 14,676 items was completed by the first and second authors and conflicts were resolved through discussion and agreement. Following the removal of 14,061 items, the remaining 615 items were screened by the first author but with iterative consultation and discussion with the second author. This resulted in a further 595 items being excluded. Citation mining identified one further item, resulting in 21 eligible articles (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Quality Appraisal, Data Extraction, and Analysis

To ensure the quality of the included studies, and the accuracy and reliability of our findings, a rigorous appraisal process was conducted concurrently with data extraction by the first author with subsequent checking and confirmation by the second author. The Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (Hong et al., 2018) was used to assess the clarity of research questions, the rationale behind each study, the quality of methodological design, and the strength of analyses used (Supplementary Tables S2a and S2b). All articles contained a well-defined research question and the data collected were appropriate to answer them. The mixed-method study did not provide justification for the research design. The risk of nonresponse bias was found to be high in three quantitative descriptive studies although one of them did not provide any relevant information to ascertain it. The use of secondary data in two cross-sectional quantitative studies might have compromised outcomes due to potentially unmeasured confounding variables.

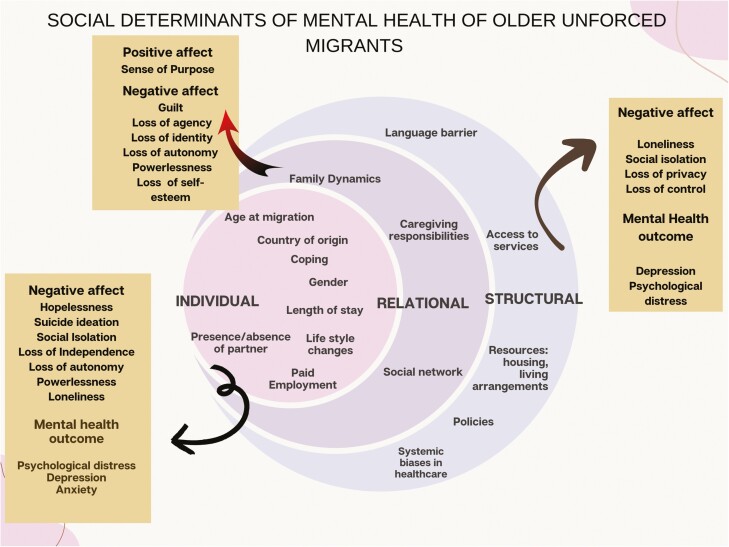

The first author extracted relevant data related to study characteristics such as authors, publication year, aims, research design, and methods, with subsequent checking and confirmation by the second and third authors. In addition, sample characteristics such as country of origin, contexts of migration, and results related to mental health from each study were also extracted. The extracted results from each study were entered into NVivo QSR to facilitate coding and analysis. The initial coding was done inductively by the first author and subsequently checked and confirmed by the second and third authors. The initial coding was entirely driven by the data with the aim of developing a comprehensive understanding of the data without being influenced by any framework. The process involved immersion in the data through multiple rounds of readings, and a line-by-line coding of the data which helped in comparing the concepts identified in different studies and determining their similarities or differences. By focusing on shared concepts rather than specific methodologies, the thematic analysis allowed for the integration of diverse research approaches into a coherent synthesis. The analysis revealed a range of social determinants interacting at multiple levels and influencing the mental health of older migrants. To facilitate discussions, we situated the themes within a customized socioecological framework that allowed the assessment of SDH both independently and collectively (Stokols, 1996). This customized framework draws upon elements from previous frameworks utilized in review studies focusing on the mental health of migrants (Hawkins et al., 2021; Mengesha et al., 2017) and categorizes the findings into three main categories of determinants: individual, relational, and structural (Figures 1 and 2). Within each of these categories, we organized a diverse range of factors that reportedly influence mental health. The individual factors in this review refer to the factors that are specific to an individual including demographic characteristics like age, gender, marital status, occupation, etc., or the individual behaviors that affect mental health. The relational factors are related to the interpersonal relationships of the migrants, the associated roles and responsibilities, and the expectation of support. The structural determinants encompass factors emanating from the broader social and political structures.

Figure 2.

Social determinants of mental health of older unforced migrants.

Results

The review included a total of 21 studies, comprising 14 qualitative, 6 quantitative, and 1 mixed-methods study. The samples in these studies were diverse in terms of ethnicity, nationality, gender, and migration contexts. Most of the studies (n = 15) were conducted in the United States, Canada, and Australia, whereas the remaining studies focused on migration destinations such as the United Kingdom, Israel, New Zealand, Turkey, and Singapore. Two comparative studies were identified, one comparing English and French Canadians who undertook seasonal migration to the United States (Mullins & Tucker, 1992), and the other comparing older veterans and new arrivals migrating to Israel (Ron, 2007).

The qualitative studies employed various methodologies, such as phenomenology, narrative, and ethnography. Data were collected through individual or group interviews, focus group discussions, forums, or a combination of these methods. To explore the mental health of older migrants, study samples comprised older migrants, family members, and service providers, either individually or in combination. The quantitative studies utilized structured interviews and scales, such as the General Health Questionnaire and Public Health Questionnaire to measure migrants’ mental health and generate data for statistical analyses. Table 1 presents an overview of the included studies.

Table 1.

Summary of Reviewed Studies

| Authors, year | Study aims | Design, methods, and analysis | Relevant sample characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alvi and Zaidi, 2017 | To understand the quality of life and well-being as well as their associated factors among South Asian older immigrant women in Canada. | Qualitative Primary data: Semistructured interviews Analysis: Thematic |

n = 10 Age range (55–81) Sampling: Purposive |

| Caidi et al., 2020 | To examine older Chinese migrants’ information practices and the transnational dimension of their settlement process in Canada and Australia. | Qualitative Primary data: Interviews Analysis: Thematic |

n = 16 Age range (60 and above) Sampling: Convenience and snowball |

| Chiu and Ho, 2020 | To examine Chinese grandparenting migrants’ contributions to social reproduction through transnational care circulation and the changes in their perspectives of intergenerational family caregiving contracts in the Singaporean context. | Qualitative ethnography Primary data: Interviews; participant observation Analysis: Thematic |

n = 41 Mean age: 64 Sampling: Convenience |

| Chou, 2007 | To examine whether the origin of country and visa type predicted psychological distress among older migrants to Australia over a period of 1 year and whether their association changed after factors in health, social roles, cohort effect, and social support were adjusted. | Quantitative Data set: Secondary data—Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Australia (LSIA) Measurements: Psychological distress (12-item General Health Questionnaire, GHQ-12) Analysis: Descriptive statistics; bivariate analysis of associations of GHQ-12 with paired t-tests at baseline and one 1-year follow-up and two regression models to check the influence of predictors on outcome |

Nationwide representative sample n = 431 (baseline assessment) n = 359 (1 year after baseline assessment) Age range (50 and above) Sampling: Stratified random |

| Dhillon andHumble, 2020 | To understand how Punjabi Indian women living in Nova Scotia, Canada, define their mental health and well-being regarding their sociocultural roles held in their families and community. | Qualitative Primary data: Semistructured interviews Analysis: Thematic |

n = 5 Age range (65–68) Sampling: Convenience |

| Girgis, 2020 | To explore the protective factors and processes that foster resilience and buffer psychosocial distress among later-life Egyptian immigrants in the United States. | Qualitative Primary data: Structured interviews Analysis: Thematic; interpretive phenomenological |

n = 30 Age range (62–6) Sampling: Criterion and snowball |

| Guo et al., 2019 | To understand if migrating at an older age is associated with the poorer psychological well-being of Chinese immigrants in the United States. If so, what factors account for such differences? | Quantitative Data set: Secondary data— Baseline population of Chinese Elderly (PINE study) Measurements: Psychological well-being (Public Health Questionnaire, PHQ-9); Health status (Katz Activity of Daily Living Index and the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale); Social psychological change (Likert scale) and quality of life (QoL; four-point scale); Sense of Community Index Analysis: Group differences were measured using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square test. Correlation analysis for key variables; negative binominal and logistic regressions used to check the influence of predictors on outcome |

n = 3,138 n = 467 Age range (60–105) Sampling: Representative |

| Hamilton et al., 2021 | To explore how the idealized norms of intergenerational care provision interact with Australian immigration and work regimes to produce specific patterns of transnational care and support arrangements among Chinese, Vietnamese, and Nepalese migrants. | Qualitative Primary data: focus group discussion (FGD), semistructured interview Analysis: Content |

n = 12 Age range (55–74) Sampling: Convenience |

| Karacan, 2020 | To discuss the vulnerability patterns of German retirees in Alanya, Turkey, and the role of social networks, with a particular focus on intergenerational family relations. | Mixed methods Primary data: Qualitative interviews; nonstandardized questionnaires Analysis: Thematic, descriptive |

n = 34 immigrants n = 10 experts Age range (50–89) Sampling: Purposive |

| Lai and McDonald, 1995 | To understand the life satisfaction of Chinese immigrants in Canada and to identify associations with several independent variables. | Quantitative Measurements: Life satisfaction (Life Satisfaction Index); Psychological health (Psychiatric Evaluation Scale); Physical health (General Health Index, self-perceived health status questionnaire); Social support and activity level questionnaire by Wan & associates; Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale; modified version of Sense of Personal Control Instrument by Pearlin & Schooler; English capacity (researcher-constructed instrument); Financial adequacy question Analysis: Descriptive statistics; ANOVA; multiple regression |

n = 81 Age range (65–-96) Sampling: Simple random |

| Lee et al., 1996 | To investigate the impacts of quantitative, structural, and functional aspects of social relationships on the prevalence of depressive symptoms among older Korean immigrants in the United States, considering their acculturation level, life stress, and demographic characteristics. | Quantitative Data set: Secondary data—Ethnic Elderly Needs Assessment Survey Measurements: Acculturation level and social support: (structured interview schedule); Life stress: (sum of standardized scores of undesirable life events and financial strains); Depression: Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression Scale (20 items) Analysis: Multiple regression |

n = 200 Age range (50 and above) Sampling: Convenience random |

| Montayre et al., 2017 | To explore older Filipino migrants’ experiences regarding adjustment to life in New Zealand. | Qualitative Primary data: Semistructured interviews Analysis: Thematic |

n = 17 Age range (60 and above) Sampling: Purposive |

| Mullins and Tucker, 1992 | To compare emotional and social isolation among older French Canadian seasonal residents in Florida, the United States, and their English–Canadian counterparts. | Quantitative Primary data: survey questionnaire Analysis: Descriptive statistics chi-square test |

n = 673 Mean age: 65.45 Sampling: Convenience and purposive |

| Park and Kim, 2013 | To explore the immigrant experiences of older Koreans and their intergenerational family relationships in New Zealand. | Qualitative Primary data: Multistepped phenomenological interviews with migrants; interviews with key informants Analysis: Concept mapping |

n = 10 migrants n = 20 key informants Age range of migrants (71–88) Age range of key informants (30–80) Sampling: Snowball and convenience |

| Ron, 2007 | To compare levels of depression, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation among new immigrants from the Former Soviet Union and veterans living in Israel since 1948. | Quantitative Primary data: Demographic questionnaire; Depression (Beck Depression Inventory); Hopelessness (Beck Hopelessness Scale); Suicide ideation (Beck Scale of Suicide Ideation) Analysis: Linear regression analysis t-Test and Pearson correlation |

n = 394 veterans Age range (65–84) n = 376 recent older immigrants Age range (65–82) Sampling: Convenience |

| Sah et al., 2018 | To understand the drivers of mental distress in older Nepalese women living in the United Kingdom. | Qualitative Primary data: Narrative style interviews; FGD Analysis: Grounded thematic network |

n = 20 Age range (60 and above) Sampling: Naturalistic purposive |

| Sepulveda et al., 2016 | To gather information on the needs of culturally and linguistically diverse grandparent carers in Australia to ascertain the gaps in service provision. | Qualitative Primary data: Service provider consultations; grandparent carers forums Analysis: Thematic |

n = 60 service providers n = 56 grandparent carers Age range (not mentioned) Sampling: Purposive |

| Serafica and Reyes, 2019 | To describe the factors contributing to acculturative stress among recent older Filipino immigrants who co-resided with their adult children in the United States. | Qualitative Primary data: FGDs Analysis: Content |

n = 40 Age range (65 and above) Sampling: Purposive |

| Stewart et al., 2011 | To explore general barriers to access and appropriateness of services for older immigrants from diverse ethnicities in Canada. | Qualitative Primary data: Interviews with seniors; group interviews with service providers Analysis: Thematic content |

n = 48 immigrants n = 26 service providers Age range (55 and above) Sampling: Purposive and snowball |

| Treas and Mazumdar, 2002 | To understand the reasons for the loneliness, isolation, and boredom of older immigrants from diverse ethnicities in the United States. | Qualitative Primary data: Interviews Analysis: Thematic |

n = 28 Age range (61–85) Sampling: Convenience |

| Treas, 2008 | To explore the international migration patterns and the transnational family lives of migrants from diverse ethnicities in the context of contested public policies in the United States. | Qualitative Primary data: Interviews Analysis: Thematic |

n = 54 Age range (60 and above) Sampling: Criterion |

The review classified motivations for migration in later life as push factors, pull factors, and family reunification (technically also a pull factor). The pull factors included migrations for personal motivations, such as lifestyle seeking and relational factors leading to family reunification. Lifestyle seekers migrate to destinations offering improved quality of life through factors such as better weather (Mullins & Tucker, 1992), lower cost of living (Karacan, 2020), and better access to facilities (Sah et al., 2018). The primary motivation for family reunification is to be close to adult children (Caidi et al., 2020; Chiu & Ho, 2020; Dhillon & Humble, 2020; Girgis, 2020; Park & Kim, 2013; Serafica & Thomas Reyes, 2019; Stewart et al., 2011; Treas, 2008), highlighting the importance of social relationships and connections in the migration decision-making process. Family reunification studies either focused on temporary migration and the transnational lifestyle of migrants (Chiu & Ho, 2020) or a combination both of permanent and temporary migration (Hamilton et al., 2021; Treas & Mazumdar, 2002). Two of the studies did not specify the focus area (Chou, 2007; Sepulveda et al., 2016). This group of migrants mostly migrate during important life events such as the marriage of adult children or the birth of grandchildren. The third factor identified by two studies is the push factor with structural inequalities in the migrants’ home countries motivating the decision to migrate (Alvi & Zaidi, 2017; Girgis, 2020). However, these migrations were mostly achieved via the family reunification route (see Table 2 for an overview).

Table 2.

Context of Migration and Mental Health Outcomes

| Authors, year | Context of migration | Migration flows | Key outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | |||

| Alvi and Zaidi, 2017 | Structural inequalities | India Sri Lanka Pakistan |

Canada | Limited social networks, cultural differences, lack of mobility, language difficulties, dependence on children, unfulfilled care expectations, and abuse at the hands of the family led to loneliness and isolation. Physiological decline was not identified as a significant factor. |

| Caidi et al., 2020 | Family reunification | China | Australia Canada |

Language barriers, unfamiliar environments, inaccessibility of services, declining health, diminished social networks, loss of autonomy, and higher cost of living all led to psychological distress. Coping strategies included seeking out co-ethnics and expanding the local network. |

| Chiu and Ho, 2020 | Family reunification | China | Singapore | Prioritizing future generations over oneself, time-consuming childcare duties, adapting to new environments and language, financial dependence, lack of social protection, discrimination, and loss of autonomy led to loneliness and isolation. |

| Chou, 2007 | Family reunification | Asian countries 44.7% western and developed countries 21.5% other countries 33.8% | Australia | General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) score deteriorated over a period of 1 year among older migrants. Family reunification migrants had better mental health than refugees but worse than skilled labor visa holders. Older migrants from developing nations, retirees, and women experienced higher psychological distress. |

| Dhillon and Humble, 2020 | Family reunification | India | Canada | Family reunification was found to have a positive impact on mental health. However, factors such as reliance on offspring, language barriers, and decreased social networks contributed to feelings of loneliness. |

| Girgis, 2020 | Structural inequalities | Egypt | United States | To manage daily stress migrants leveraged social capital, family support, religious organizations, and social services as part of problem-solving coping. Emotion-focused coping involved adherence to traditional gender roles and cognitive strategies like acceptance, mindfulness, and reminiscence. |

| Guo et al., 2019 | Family reunification | China | United States | Low income, poor health, dependence on family, weak social ties, and lack of health care access contributed to emotional distress and depression. Family support and social ties confounded the effect of age at migration on depression. |

| Hamilton et al., 2021 | Family reunification | China Nepal Vietnam |

Australia | Language barriers, cultural differences in childrearing practices, inaccessible health care, intense childcare duties, dependence on adult children, and financial concerns caused psychological distress. Community engagement promoted emotional well-being. |

| Karacan, 2020 | Lifestyle migrants | Germany | Turkey | Despite social and economic advantages, migrants felt vulnerable due to limited familial support, fears about obtaining residence permits, limited access to public health care, and bureaucratic hurdles caused by the legal regulations of the two nation-states. |

| Lai and McDonald, 1995 | Sponsored migrants | Hong Kong or mainland China | Canada | Both genders valued financial adequacy, social support, personal control, and psychological/physical health. Men specifically valued activity levels, while women also emphasized the length of residency in Canada, English proficiency, and self-perceived health. |

| Lee et al., 1996 | Not stated | Korea | United States | Too much or too little contact with children was harmful, and infrequent contact with friends raised depressive symptom risk. Emotional support from family was crucial to mental health. |

| Montayre et al., 2017 | Family reunification | Philippines | New Zealand | Immigrants were optimistic about adapting to new ways of life but faced challenges such as language barriers, navigating the health care system, cultural differences, and negative attitudes from hospital staff. |

| Mullins and Tucker, 1992 | Lifestyle migrants | Canada | United States | Living alone was linked to emotional isolation in English Canadians, while this association was moderated by age, gender, and self-rated health in French Canadians. French Canadians with fewer children and English Canadians with fewer friends reported higher levels of isolation. |

| Park and Kim, 2013 | Family reunification | Korea | New Zealand | Social isolation and depression resulted from language barriers, limited social life, lack of access to social welfare, decreased family support, and abuse or neglect. Gender served as a protective factor for women. |

| Ron, 2007 | Did not want to stay in USSR | USSR | Israel | Older immigrants had significantly higher scores on measures of depression, hopelessness, and suicide ideation compared to veterans. |

| Sah et al., 2018 | Lifestyle migrants | Nepal | United Kingdom | The absence of family, language barriers, limited mobility, housing issues, illness, fear of death, separation from children, and financial struggles led to emotional distress. |

| Sepulveda et al., 2016 | Family reunification | African, Asian, Spanish, Middle Eastern, European, Pacific Island and Maori | Australia | Caring for grandchildren provided a sense of purpose, but exhausting childcare duties, conflicts over childrearing, and limited access to legal and immigration advice led to social isolation. |

| Serafica and Reyes, 2019 | Family reunification | Philippine | United States | Caregiving, losing a sense of agency, authority, and confidence because of language issues, dependence on children for mobility, and diminished social networks all negatively affected the quality of life. |

| Stewart et al., 2011 | Family reunification | Chinese, Afro-Caribbean, former Yugoslavian, and Spanish-speaking immigrant seniors | Canada | Loss of social networks, harsh climate, family conflict, dependence on family, language, and cultural barriers, exhausting childcare responsibilities, inaccessibility of governmental services, and homesickness led to social isolation and loneliness. |

| Treas and Mazumdar, 2002 | Family reunification | Korea, Mexico, Taiwan, Iran, Egypt, Jordan, Pakistan, and Vietnam | United States | Partner loss, reduced socialization, language barriers, demanding caregiving duties, changing family dynamics, and reliance on kin for mobility led to loneliness and social isolation. Presence of partner, co-ethnics, and involvement in local organization activities protected against negative outcomes. |

| Treas, 2008 | Family reunification | Bangladesh, Cambodia, Cuba, El Salvador, Egypt, Iran, Japan, Jordan, Korea, Mexico, Pakistan, Philippines, Spain, Taiwan, and Vietnam | United States | Appreciation for better facilities in the United States did not mitigate the longing for the homeland. Concerns faced included loss of authority in their children’s house and the pressure for housekeeping and childrearing. |

The role of push-and-pull terminology has been limited to understanding the factors compelling people out of their homeland or attracting them to a destination country. Factors affecting mental health have been understood and reported using a customized socioecological framework (see Figure 2).

Individual Determinants

Individual-level determinants comprised personal characteristics of migrants such as age at migration, gender, marital status, and physical capabilities that acted either as protective or risk factors.

The age at migration emerged as an important factor influencing the mental health of these migrants. Mullins and Tucker (1992) found that older migrants experienced poorer mental health than younger migrants, likely due to the difficulties in adjusting to new environments, experiences of cultural dislocation, and higher rates of social isolation. Similarly, Ron (2007) found that later-life migrants had higher depression, hopelessness, and suicide ideation scores compared to those who migrated young.

Old age was accompanied by the fear of physiological decline and impending death, which was reported by migrants across migration contexts. The psychological consequences stemming from the fear of death could play a substantial role in shaping an individual’s mental health. Loss of independence and the fear of becoming a burden on adult children were the most prevalent concerns (Caidi et al., 2020; Karacan, 2020; Serafica & Thomas Reyes, 2019; Stewart et al., 2011). Sah et al. (2018) found that the absence of family members caused emotional distress among older Nepalese migrants in the United Kingdom. These individuals expressed a strong wish to age and pass away in the presence of their families, specifically adult male children who typically perform cultural rituals. This population group was Nepalese women who were wives or widows of the ex-British Gurkha Army and migrated to the United Kingdom to avail of pensions given to ex-Army men. Many migrated either without family or were restricted from living with family in the United Kingdom due to pension criteria. The potential financial burden of bringing overseas relatives together for their funerals further exacerbated their stress. Several studies also showed that temporary migrants’ ineligibility for public health care was linked to guilt for burdening their adult children with medical expenses, leading to a reluctance to seek medical care for health issues (Chiu & Ho, 2020; Hamilton et al., 2021; Stewart et al., 2011).

The role of gender in shaping migration experiences was prominent in the case of family reunification. Women who migrated alone from patriarchal societies for family reunification adapted well to their new environment (Park & Kim, 2013; Serafica & Thomas Reyes, 2019) because they continued to perform the same domestic duties as they did in their homelands, which provided them with a sense of familiarity and purpose. Sah et al. (2018) and Treas and Mazumdar (2002) reported that migration provided some women the opportunity to escape patriarchal gendered norms. However, ongoing challenges with cultural adaptation and loneliness remained a concern for the mental health in these studies irrespective of gender.

One study showed that engaging in traditional gender roles was a cognitive coping strategy (Alvi & Zaidi, 2017), whereas another reported that mindfulness and reminiscing about life in the home country helped in coping with the challenges of migration (Treas & Mazumdar, 2002).

The presence or absence of a partner was found to make a difference in the mental health of older migrants. Having a partner mitigated feelings of loneliness, as there was someone to talk to, and it led to lower acculturation stress (Girgis, 2020; Treas & Mazumdar, 2002), compared to those who had lost a partner having increased feelings of loneliness (Karacan, 2020; Ron, 2007; Sah et al., 2018). Chou (2007) and Sah et al. (2018) found that migrant status and language barriers, along with widowhood, may contribute to intensified experiences of isolation. Alternatively, men who migrated without their partners were shown to struggle with feelings of boredom and uselessness (Park & Kim, 2013; Serafica & Thomas Reyes, 2019), which could be associated with a low engagement in individual coping strategies.

Factors such as employment, economic status, and the ability to maintain cultural practices were reportedly responsible for varying levels of acculturation stress (Caidi et al., 2020; Chiu & Ho, 2020; Sah et al., 2018). Paid employment provided a sense of purpose and meaning, which was shown to mitigate some individual factors affecting well-being (Chiu & Ho, 2020; Chou, 2007). However, unrecognized foreign credentials limited the employability of older migrants, which also led to dependency on adult children and contributed to mental health consequences (Alvi & Zaidi, 2017; Girgis, 2020; Stewart et al., 2011).

Furthermore, studies examining the relationship between the length of residency in the host country and mental health have yielded contrasting results. Lai et al. (1995) found that length of residency was positively associated with life satisfaction among older Chinese women migrants in Canada, whereas Chou (2007) showed that psychological distress increased over time among a general sample of older migrants in Australia. Additionally, Chou (2007) found that the country of origin was a predictor of psychological distress, with migrants from low-income countries experiencing higher levels as compared to migrants from high-income countries.

Lifestyle changes, such as the inability to cook familiar food or eat at familiar times, and the limited access or affordability of familiar ingredients also negatively affected mental health (Caidi et al., 2020; Sah et al., 2018; Serafica & Thomas Reyes, 2019).

Insights into how older migrants cope with psychological distress were provided by several studies. These strategies influenced by cultural and social factors included spending time with family and friends, using social media to stay in touch with the homeland, or gathering information to connect with co-ethnics in host countries (Caidi et al., 2020; Girgis, 2020; Karacan, 2020). Other strategies involved attending English language classes (Stewart et al., 2011), participating in community-based activities (Hamilton et al., 2021; Treas & Mazumdar, 2002), or emotion-focused religious coping at local churches or mosques (Girgis, 2020). Seeking support from family, friends, and community members was helpful for those who understood or had the confidence to navigate local systems.

Relational Determinants

Familial relationships were reportedly significant determinants of mental health, specifically among those migrating for family reunification. Cordial family dynamics served as protective factors, whereas complex family dynamics negatively affected well-being. Studies consistently showed that older migrants’ dependence on adult children due to limited knowledge or unfamiliarity with the host country (Stewart et al., 2011; Treas & Mazumdar, 2002) led to negative mental health outcomes (Alvi & Zaidi, 2017; Chiu & Ho, 2020; Hamilton et al., 2021; Treas, 2008) including a loss of agency, assertiveness, decision-making power, and self-esteem (Serafica & Thomas Reyes, 2019; Stewart et al., 2011; Treas & Mazumdar, 2002).

Changes in family roles, especially among family reunification migrants, affected their identity and the nature of family relationships, such that older migrants often prioritized family needs over their own (Serafica & Thomas Reyes, 2019) and rationalized their subordination to avoid conflict with adult children, as described in two studies (Chiu & Ho, 2020; Treas & Mazumdar, 2002). Several studies showed that older migrants provided financial support to their adult migrant children, or performed housekeeping and childrearing (Alvi & Zaidi, 2017; Caidi et al., 2020; Hamilton et al., 2021; Treas, 2008; Treas & Mazumdar, 2002). Older migrants’ care of grandchildren was usually to enable adult children to work (Chiu & Ho, 2020; Hamilton et al., 2021; Treas, 2008), which variously led to positive or negative well-being. Sepulveda et al. (2016) noted that caring for grandchildren provided these migrants with a sense of purpose that contributed to positive mental health. Other studies showed negative mental health related to physical and emotional exhaustion, lack of sleep, and fear related to not meeting adult children’s expectations (Hamilton et al., 2021), social isolation (Sepulveda et al., 2016), and lack of leisure time (Serafica & Thomas Reyes, 2019; Stewart et al., 2011). Hamilton et al. (2021) showed that the lack of information about child discipline and protection in the host country was additional stress for grandparent carers.

Many migrants belonging to collectivist cultures were reportedly disappointed that their adult children could not fulfill the cultural obligations of looking after them. Factors such as the busy lifestyles of adult children, limited emotional support and companionship, left older migrants feeling disconnected from their families (Serafica & Thomas Reyes, 2019), and resulted in poor mental health when disconnected from the community in the host country (Caidi et al., 2020; Serafica & Thomas Reyes, 2019; Stewart et al., 2011; Treas & Majumdar, 2002). Loss of familiar routines, traditions, and social activities left older migrants questioning whether family reunification had been worth the trouble (Caidi et al., 2020; Chiu & Ho, 2020). Lee et al. (1996) showed that emotional support was a mitigator of the negative effects of migration on migrants’ mental health, more so than instrumental support. However, emotional support is difficult to achieve when adult children were busy and not available.

Social organizing based on individualism in the host country had an impact on relational contexts and, therefore, well-being. According to Alvi and Zaidi (2017), the breakdown of the collectivist culture’s family ethos contributed to poor mental health among migrants seeking family reunification. Alternatively, Treas and Mazumdar (2002) noted that some older migrants welcomed individualism as it allowed them an opportunity to break free from traditional interdependence. Regarding lifestyle migrants, Karacan (2020) explained how these migrants prioritized their autonomy over traditional familial obligations of care and made it clear that they did not expect care from their adult children in return.

Structural Determinants

The review identified various structural factors affecting the mental health of these migrants. Among these, poor language proficiency emerged as the most prominent factor across migration contexts (Alvi & Zaidi, 2017; Caidi et al., 2020; Chiu & Ho, 2020; Chou, 2007; Dhillon & Humble, 2020; Hamilton et al., 2021; Karacan, 2020; Montayre et al., 2017; Park & Kim, 2013; Sah et al., 2018; Serafica & Thomas Reyes, 2019; Stewart et al., 2011; Treas & Mazumdar, 2002).

Studies highlighted how poor language proficiency made daily tasks, such as buying groceries or reading medical prescriptions, overwhelming for older migrants (Caidi et al., 2020). In fact, the ability to communicate in the local language was found to be a prerequisite for survival (Park & Kim, 2013). Migrants who had difficulty communicating often experienced loneliness, social isolation, and depression (Alvi & Zaidi, 2017; Park & Kim, 2013), and had difficulty forming meaningful relationships and friendships (Alvi & Zaidi, 2017; Caidi et al., 2020; Chiu & Ho, 2020; Dhillon & Humble, 2020; Sah et al., 2018; Serafica & Thomas Reyes, 2019; Stewart et al., 2011). Conversations with locals were often limited to nonverbal expressions (Caidi et al., 2020), and in some cases, they were unable to communicate with their grandchildren due to language barriers (Treas & Mazumdar, 2002).

Stewart et al. (2011) highlighted the association between language barriers and the ability to access services, saying it was a fundamental issue because older migrants were often precluded from accessing the information they needed to respond to their declining health. Although family reunification migrants relied on adult children for support, lifestyle migrants continually relied on social networks to navigate systems and services (Karacan, 2020). The availability of translators in health care systems was rendered futile because of long waiting times (Sah et al., 2018; Stewart et al., 2011). Migrants who could not access language services had to rely on adult children for translation when visiting medical services. This left them experiencing a loss of privacy (Dhillon & Humble, 2020), a loss of control (Stewart et al., 2011), and sometimes even misdiagnosis (Sah et al., 2018). Additionally, two studies showed systemic biases such as racial stereotypes, negative attitudes, and a lack of ethnic understanding among medical providers, led to the neglect of the psychosocial and emotional needs of these migrants (Alvi & Zaidi, 2017; Stewart et al., 2011).

Language barriers had an impact on independent movement as migrants struggled to understand signage and maps, leading to a lack of confidence in driving (Alvi & Zaidi, 2017; Caidi et al., 2020; Dhillon & Humble, 2020) or taking public transport (Chiu & Ho, 2020). As a result, structural factors interacted with individual and relational factors, leading to a loss of self-confidence and relationship tensions with adult children (Dhillon & Humble, 2020; Sah et al., 2018; Serafica & Thomas Reyes, 2019; Stewart et al., 2011; Treas & Mazumdar, 2002). Chiu and Ho (2020) emphasized that language barriers affected the ability of migrants to navigate their surroundings, limiting their access to essential services and places of interest. The combination of language barriers and mobility issues was reported to increase the risk of social isolation and loneliness, leading to a decline in mental health and well-being (Alvi & Zaidi, 2017; Dhillon & Humble, 2020; Sah et al., 2018; Stewart et al., 2011).

Girgis (2020) observed that the presence of conflicting cultural expectations while co-residing with adult children led to unfulfilled emotional needs and social isolation for older migrants. They felt pressured to prove their relevance in the household and many were reported to experience emotional, psychological, and financial abuse or neglect (Alvi & Zaidi, 2017; Park & Kim, 2013; Stewart et al., 2011). Treas (2008) found that many preferred to move out of their children’s houses to live independently. However, financial strain (Sah et al., 2018) and inaccessibility of safe and affordable housing (Karacan, 2020) affected their quality of life. Sah et al. (2018) illustrated how some were forced into share-house situations, with people from different cultures, vegetarians with nonvegetarians, and not able to cook and eat what they chose, leading to suboptimal housing and often going to bed hungry.

Three studies identified policies as a factor affecting the mental health of older migrants. According to Chiu and Ho (2020), older Chinese migrants in Singapore faced challenges related to unclear migration pathways, high costs of settlement, and regulatory mechanisms that limited their access to social security. These migrants had to renew their visas continuously in the absence of specific pathways for permanent settlement, which prevented them from accessing welfare benefits. Similarly, Sah et al. (2018) found that older Nepalese migrants in the United Kingdom who resided with their adult children were unable to access state benefits, causing financial stress and tensions within the family. Hamilton et al. (2021) criticized the constraints associated with Australian migration regulations, where older Nepalese and Vietnamese transnational migrants feared their eventual aging away from their adult children when they were no longer able to access visas or travel back and forth to Australia.

Discussion

The review explored the drivers of unforced migrations in later life and the SDH influencing the mental health of these migrants. Migration decisions are complex and involve multiple factors that interact with each other to inform the final decision to migrate (de Haas, 2021). The same is true for the three contexts in which unforced migration in later life occurs—a desire for family reunification, seeking a better lifestyle, or escaping the disadvantages associated with structural inequity in their homelands. A common feature that underpinned motivation across contexts was the pursuit of improved quality of life, which is consistent with Warnes' (2009) typology of migration later in life in Europe.

In the case of lifestyle seekers, financial constraints and the absence of affordable health care facilities are significant factors driving them to migrate to places offering better amenities or lower cost of living. The desire to be closer to family emerged as the most prevalent motivation for migrations in later life. For these migrants, the desire for familial proximity acts as a pull factor, along with the absence of adequate social and welfare support in their homeland pushing them to be closer to their adult children for care needs who are culturally entrusted to do so (Thapa et al., 2018). Those facing structural inequities in their homeland also migrate to safer places in later life. Thus, narrowly perceiving unforced migrations as solely personal preference may overlook the complex realities and challenges faced by migrants, potentially leading to the state neglecting its responsibilities toward them (Ottonelli & Torresi, 2013).

Individual-centric psychological perspectives have significantly influenced how mental health is conceptualized, practiced, and researched so far (Georgeou et al., 2021). However, we observed that the mental health of these migrants is influenced by a combination of factors operating at individual, relational, and structural levels. For example, gender roles played a significant role in older family reunification migrants’ adaptation to the host country as women bore the burden of caregiving due to discursive cultural expectations, making it easier for them to adapt to new environments but more challenging for them to engage in social activities. Engaging in traditional gender roles was reportedly a cognitive coping strategy for these women (Alvi & Zaidi, 2017). Alternatively, older migrant men reportedly took on different roles, such as household repair work, shopping, gardening, or casual jobs (Hamilton et al., 2021), which gave them an outlet and prevented boredom, if they had linguistic skills and confidence to participate in their new community.

Guo et al. (2019) suggest that later-life migrants find it particularly difficult to acculturate due to their long exposure to heritage culture. We observed that family reunification migrants from collectivist to individualistic societies often experience psychological distress due to unfulfilled emotional needs resulting from the busy lifestyles of their adult children. These older migrants, with limited financial resources, language proficiency, social networks, and familiarity with the local culture, experience significant drawbacks. They often disregard their own needs and instead undertake exhausting household chores for their adult children, driven by a sense of guilt of dependency. The absence of desired emotional support led to feelings of alienation, social isolation, and loneliness for the older people in their new environments. The link between social isolation, loneliness in older adults, and compromised mental health, including the development of depressive symptoms, is well established (Chen & Feeley, 2014). Additionally, it has been associated with cognitive decline, increased vulnerability to alcohol dependence, a higher prevalence of suicidal thoughts, and deteriorating physical functioning (Perissinotto et al., 2012). Strained familial relationships exacerbate their challenges underscoring the need for formal support services for these migrants. In the absence of a formal support system, lifestyle seekers, who willingly prioritize their personal aspirations over familial obligations, also yearn for the support and closeness of their family during times of poor health.

The review highlighted that for those who could afford it, transnational migration offers a potential solution, allowing migrants to maintain familial proximity through frequent visits to family in the host nation and returning home to maintain personal well-being associated with familiar culture, language, and place. The trend of transnational lifestyles is becoming more prevalent, breaking away from the traditional notion of migration being limited to labor or amenity-seeking purposes. Recent research indicates that this phenomenon is part of the globalization of migration, characterized by increased mobility and blurred national boundaries (Czaika & de Haas, 2014; Holecki et al., 2020).

Consistent with the findings of Wali and Renzaho (2018), we observed that bonding with co-ethnics played a crucial role in participants’ acculturation journeys by providing a platform to share culture, language, and challenges, alleviating stress, and fostering a sense of belonging to the new environment.

It was also observed that the existing literature on migration tends to overlook the significant influence of upstream factors other than language barriers and access to health care. The migrant status, a key determining factor influencing mental health, is often overlooked. Unless these migrants become permanent, they have limited access to social protection and resources such as employment and health care. Although forced migrants benefit from protective welfare policies, unforced migrants experience differential access to resources, leading to persistent fear and stress surrounding their circumstances.

Consistent with the findings of Georgeou et al. (2021) and Ma and Joshi (2021), we also identified language barriers as a significant and ongoing challenge for older migrants, regardless of whether they are permanently settled or engaged in transnational migration. Notably, the degree of linguistic, cultural, and adaptation barriers may vary depending on the context, age, and gender of the migrant. Older migrants face unique challenges in learning a new language due to age-related cognitive impairments and declining adaptive capacity (Caidi et al., 2020; Slade & Borovnik, 2018). Attending language classes may also be challenging for family reunification migrants due to limited time, as they may be burdened with caregiving duties, leading to further feelings of loneliness (Treas & Majumdar, 2002). However, Stewart et al. (2011) note that language classes and social programs can provide opportunities for older migrant carers to escape their caregiving responsibilities.

Our findings underscore the importance of considering the role of migration policies in shaping kinship ties of family reunification migrants and their mental health consequences. Limited migration pathways for permanent settlement of the older migrants belonging to collectivist societies compel them to maintain dual lives to fulfill their cultural responsibilities. Future research could explore the aging aspirations and caregiving and receiving experiences of such migrants and their mental health concerns.

Limitations

The diverse sample populations from multiple nations in the selected studies posed a challenge for categorizing and generalizing the results, highlighting the importance of contextualizing migratory experiences. The focus on English peer-reviewed journal articles may have led to the exclusion of relevant studies published in other languages and gray literature. There is also a likelihood of exclusion of potential studies covering this topic because varied terms related to different aspects of mental health are used in different cultures. Despite clearly defined inclusion–exclusion criteria, subjectivity in the screening process could not have been completely avoided.

Conclusion

The review highlights that older unforced migrants often fall through the cracks due to the perception that their migrations are entirely voluntary, and thus undeserving of state support. However, their migrations are influenced by push and pull factors, which are operational at multiple levels and significantly affect their mental health. Recognizing distinct contexts and avoiding homogenized categorizations of older migrants is crucial to developing tailored policies and programs that address their specific mental health needs. The review also challenges the notion that these migrants are a burden on host societies by emphasizing their significant contribution to providing reproductive labor within their adult children’s households, enabling them to be economically productive. Lastly, the review highlights the need to broaden the mental health field’s focus beyond individual factors and consider the interplay of relational and structural influences.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Pankhuri Bhatia, College of Education, Psychology and Social Work, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia.

Helen McLaren, College of Education, Psychology and Social Work, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia.

Yunong Huang, College of Education, Psychology and Social Work, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia.

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Data Availability

No original data were generated for this study. The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO, No. CRD42022359881.

Author Contributions

P. Bhatia (Conceptualization [Equal], Data curation [Equal], Formal analysis [Equal], Investigation [Equal], Methodology [Equal], Project administration [Equal], Resources [Equal], Software [Equal], Writing—original draft [Equal], Writing—review & editing [Equal]); H. McLaren (Conceptualization [Equal], Data curation [Equal], Formal analysis [Supporting], Methodology [Equal], Supervision [Lead], Writing—original draft [Supporting], Writing—review & editing [Equal]); Y. Huang (Conceptualization [Supporting], Formal analysis [Supporting], Methodology [Supporting], Supervision [Supporting], Writing—original draft [Supporting], Writing—review & editing [Supporting]).

References

- Alvi, S., & Zaidi, A. U. (2017). Invisible voices: An intersectional exploration of quality of life for older South Asian immigrant women in a Canadian sample. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 32(2), 147–170. 10.1007/s10823-017-9315-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastia, T., Lulle, A., & King, R. (2022). Migration and development: The overlooked roles of older people and ageing. Progress in Human Geography, 46(4), 1009–1027. 10.1177/03091325221090535 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, P., McLaren, H., & Huang, Y. (2023). Study protocol for a systematic review of the social determinants of mental health and well-being of older migrants aged 50 years and above. F1000Research, 12, 16. 10.12688/f1000research.128154.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandenberger, J., Tylleskär, T., Sontag, K., Peterhans, B., & Ritz, N. (2019). A systematic literature review of reported challenges in health care delivery to migrants and refugees in high-income countries—The 3C model. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 755. 10.1186/s12889-019-7049-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brell, C., Dustmann, C., & Preston, I. (2020). The labor market integration of refugee migrants in high-income countries. Centre for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo). Working Paper No. 8050. 10.2139/ssrn.3526605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caidi, N., Du, J. T., Li, L., Shen, J. M., & Sun, Q. (2020). Immigrating after 60: Information experiences of older Chinese migrants to Australia and Canada. Information Processing & Management, 57(3), 102111. 10.1016/j.ipm.2019.102111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carney, M. A. (2015). Unending hunger—Tracing women and food insecurity across borders. University of California Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt13x1h8d [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y., & Feeley, T. H. (2014). Social support, social strain, loneliness, and well-being among older adults: An analysis of the health and retirement Study. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31(2), 141–161. 10.1177/0265407513488728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, T. Y., & Ho, E. L. E. (2020). Transnational care circulations, changing intergenerational relations and the ageing aspirations of Chinese grandparenting migrants in Singapore. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 61(3), 423–437. 10.1111/apv.12292 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chou, K.-L. (2007). Psychological distress in migrants in Australia over 50 years old: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 98(1-2), 99–108. 10.1016/j.jad.2006.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covidence. (2015). Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation. http://www.covidence.org [Google Scholar]

- Cromby, J., Harper, D., & Reavey, P. (2013). Psychology, mental health and distress. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Czaika, M., & de Haas, H. (2014). The globalization of migration: Has the world become more migratory? International Migration Review, 48(2), 283–323. 10.1111/imre.12095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Czaika, M., & de Haas, H. (2017). The effect of visas on migration processes. International Migration Review, 51(4), 893–926. 10.1111/imre.12261 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Haas, H. (2021). A theory of migration: The aspirations–capabilities framework. Comparative Migration Studies, 9(1), 1–35. 10.1186/s40878-020-00210-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon, S., & Humble, M. (2020). The sociocultural relationships of older immigrant Punjabi women living in Nova Scotia: Implications for well-being. Journal of Women & Aging, 33(4), 442–454. 10.1080/08952841.2020.1845563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drapeau, A., Marchand, A., & Beaulieu-Prévost, D. (2012). Epidemiology of psychological distress. In L’Abate L. (Ed.), Mental illnesses—Understanding, prediction and control (pp. 105–133). Intech Open. 10.5772/30872 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Georgeou, N., Schismenos, S., Wali, N., Mackay, K., & Moraitakis, E. (2021). A scoping review of aging experiences among culturally and linguistically diverse people in Australia: Toward better aging policy and cultural well-being for migrant and refugee adults. Gerontologist, 63(1), 182–199. 10.1093/geront/gnab191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgis, I. (2020). Protective factors and processes fostering resilience and buffering psychosocial distress among later-life Egyptian immigrants. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 63(1–2), 41–77. 10.1080/01634372.2020.1715522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M., Stensland, M., Li, M., Dong, X., & Tiwari, A. (2019). Is migration at older age associated with poorer psychological well-being? Evidence from Chinese older immigrants in the United States. Gerontologist, 59(5), 865–876. 10.1093/geront/gny066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield, J. C. (2014). The health of grandparents raising grandchildren: A literature review. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 40(4), 32–42; quiz 44. 10.3928/00989134-20140219-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, M., Hill, E., & Kintominas, A. (2021). Moral geographies of care across borders: The experience of migrant grandparents in Australia. Social Politics, 29(2), 379–404. 10.1093/sp/jxab024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, M. M., Schmitt, M. E., Adebayo, C. T., Weitzel, J., Olukotun, O., Christensen, A. M., Ruiz, A. M., Gilman, K., Quigley, K., Dressel, A., & Mkandawire-Valhmu, L. (2021). Promoting the health of refugee women: A scoping literature review incorporating the Social Ecological Model. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 45. 10.1186/s12939-021-01387-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holecki, T., Rogalska, A., Sobczyk, K., Woźniak-Holecka, J., & Romaniuk, P. (2020). Global elderly migrations and their impact on health care systems. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 8. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., & Nicolau, B. (2018). Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of Copyright, 1148552, 10. http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf

- International Organization for Migration. (2021). World migration report. https://worldmigrationreport.iom.int/wmr-2020-interactive/

- Jang, H., & Tang, F. (2021). Loneliness, age at immigration, family relationships, and depression among older immigrants: A moderated relationship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(6), 1602–1622. 10.1177/02654075211061279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji, G., Cheng, X., Kannaiah, D., & Shabbir, M. S. (2022). Does the global migration matter? The impact of top ten cities migration on native nationals income and employment levels. International Migration, 60(6), 111–128. 10.1111/imig.12963 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karacan, E. (2020). Coping with vulnerabilities in old age and retirement: Cross-border mobility, family relations and social networks of German retirees in Alanya. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 18(3), 339–357. 10.1080/15350770.2020.1787048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, D. W.-L., & McDonald, J. R. (1995). Life satisfaction of Chinese older immigrants in Calgary. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 14(3), 536–552. 10.1017/S0714980800009107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. S., Crittenden, K. S., & Yu, E. (1996). Social support and depression among older Korean immigrants in the United States. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 42(4), 313–327. 10.2190/2vhh-jlxy-ebvg-y8jb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine, G. N., Cohen, B. E., Commodore-Mensah, Y., Fleury, J., Huffman, J. C., Khalid, U., Labarthe, D. R., Lavretsky, H., Michos, E. D., Spatz, E. S., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2021). Psychological health, well-being, and the mind–heart–body connection: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 143(10), e763–e783. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000947 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, C., Munn, Z., & Porritt, K. (2015). Qualitative research synthesis. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 179–187. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, M., & Joshi, G. (2021). Unpacking the complexity of migrated older adults’ lives in the United Kingdom through an intersectional lens: A qualitative systematic review. Gerontologist, 62(7), e402–e417. 10.1093/geront/gnab033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengesha, Z. B., Perz, J., Dune, T., & Ussher, J. (2017). Refugee and migrant women’s engagement with sexual and reproductive health care in Australia: A socio-ecological analysis of health care professional perspectives. PLoS One, 12(7), e0181421. 10.1371/journal.pone.0181421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., & Stewart, L. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1–9. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montayre, J., Neville, S., & Holroyd, E. (2017). Moving backwards, moving forward: The experiences of older Filipino migrants adjusting to life in New Zealand. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 12(1), 1–8. 10.1080/17482631.2017.1347011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, L. C., & Tucker, R. D. (1992). Emotional and social isolation among older French Canadian seasonal residents in Florida. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 19(2), 83–106. 10.1300/j083v19n02_06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ottonelli, V., & Torresi, T. (2013). When is migration voluntary? International Migration Review, 47(4), 783–813. 10.1111/imre.12048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.-J., & Kim, C. G. (2013). Ageing in an inconvenient paradise: The immigrant experiences of older Korean people in New Zealand. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 32(3), 158–162. 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2012.00642.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perissinotto, C. M., Stijacic Cenzer, I., & Covinsky, K. E. (2012). Loneliness in older persons. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(14), 1078–1083. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2022) NVivo (released in September 2022), https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Ron, P. (2007). Depression, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation among the older: A comparison between veterans and new immigrants. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 15(1), 25–38. 10.1177/105413730701500102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sah, L., Burgess, R., & Sah, R. (2018). ‘Medicine doesn’t cure my worries’: Understanding the drivers of mental distress in older Nepalese women living in the UK. Global Public Health, 14(1), 65–79. 10.1080/17441692.2018.1473888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright, C. P., & Schwartz, S. J. (2019). The study and prevention of alcohol and other drug misuse among migrants: Toward a transnational theory of cultural stress. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(2), 346–369. 10.1007/s11469-018-0023-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser, R. W., Wendt, O., Bhavnani, S., & Nail‐Chiwetalu, B. (2006). Use of information‐seeking strategies for developing systematic reviews and engaging in evidence‐based practice: The application of traditional and comprehensive pearl growing. A review. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 41(5), 567–582. 10.1080/13682820600742190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda, M., Henderson, S., Farrell, D., & Heuft, G. (2016). Needs-gap analysis on culturally and linguistically diverse grandparent carers’ ‘hidden issues’: A quality improvement project. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 22(6), 477–482. 10.1071/PY15051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafica, R., & Thomas Reyes, A. (2019). Acculturative stress as experienced by Filipino grandparents in America: A qualitative study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40(5), 421–430. 10.1080/01612840.2018.1543740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade, N., & Borovnik, M. (2018). ‘Ageing out of place’: Experiences of resettlement and belonging among older Bhutanese refugees in New Zealand. New Zealand Geographer, 74(2), 101–108. 10.1111/nzg.12188 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stern, C., Jordan, Z., & McArthur, A. (2014). Developing the review question and inclusion criteria. American Journal of Nursing, 114(4), 53–56. 10.1097/01.naj.0000445689.67800.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, M., Shizha, E., Makwarimba, E., Spitzer, D., Khalema, E. N., & Nsaliwa, C. D. (2011). Challenges and barriers to services for immigrant seniors in Canada: “You are among others but you feel alone.” International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 7(1), 16–32. 10.1108/17479891111176278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stokols, D. (1996). Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion, 10(4), 282–298. 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y., & Zolnikov, T. R. (2021). Examining opportunities, challenges and quality of life in international retirement migration. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 12093. 10.3390/ijerph182212093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, D. K., Visentin, D., Kornhaber, R., & Cleary, M. (2018). Migration of adult children and mental health of older parents ‘left behind’: An integrative review. PLoS One, 13(10), e0205665. 10.1371/journal.pone.0205665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treas, J. (2008). Transnational older adults and their families. Family Relations, 57(4), 468–478. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00515.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Treas, J., & Mazumdar, S. (2002). Older people in America’s immigrant families. Journal of Aging Studies, 16(3), 243–258. 10.1016/S0890-4065(02)00048-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Healthy People 2030, Social determinants of health. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health [DOI] [PubMed]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2020). International Migration 2020 Highlights. United Nations. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd_2020_international_migration_highlights.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wali, N., & Renzaho, A. (2018). “Our riches are our family,” the changing family dynamics & social capital for new migrant families in Australia. PLoS One, 13(12), 1–14. 10.1371/journal.pone.0209421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. J., & Lai, D. W. (2020). Mental health of older migrants migrating along with adult children in China: A systematic review. Ageing and Society, 42(4), 786–811. 10.1017/s0144686x20001166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warnes, T. (2009). International retirement migration. In Uhlenberg P. (Ed.), International handbook of population aging (Vol. 1, pp. 341–364). Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4020-8356-3_15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe (WHO/Europe). (2018). Health of older refugees and migrants (Technical guidance for refugee and migrant health). https://www.medbox.org/preview/5d527c8b-fe0c-4c5c-af9a-3a781fcc7b87/doc.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2022). World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338 [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel, N. H., Farrag, M. F., & Hymes, R. W. (2009). Acculturative stress and depression in an older Arabic sample. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 24(3), 273–290. 10.1007/s10823-009-9096-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z., & Penning, M. (2015). Immigration and loneliness in later life. Ageing & Society, 35(1), 64–95. 10.1017/S0144686X13000470 [DOI] [Google Scholar]