Key Points

Question

Is discrimination of interpatient variabilities of RAS gene variants associated with improved accuracy in malignancy diagnosis among thyroid nodules?

Findings

This diagnostic study of 620 patients, including 438 surgically resected thyroid tumor tissues and 249 thyroid nodule fine-needle aspiration biopsies, delineated interpatient differences in RAS variants at the variant allele fraction (VAF) levels, ranging from 0.15% to 51.53%. While RAS variants alone, regardless of the extent of variation, were associated with low-risk thyroid cancer in 88.8% of tumor samples, they did not definitively distinguish malignancy of an unknown tumor; however, detection of interpatient variabilities of RAS, BRAF, and TERT promoter variants in combination could assist in classifying indeterminate thyroid nodules.

Meaning

These findings suggest that discrimination of interpatient differences in genomic variants could facilitate precision cancer detection, including preoperative malignancy diagnosis and stratification of low-risk tumors from high-risk ones, among patients with indeterminate thyroid nodules.

This diagnostic study assesses interpatient differences in RAS variants and their utility in malignancy detection among patients with thyroid nodules.

Abstract

Importance

Interpatient variabilities in genomic variants may reflect differences in tumor statuses among individuals.

Objectives

To delineate interpatient variabilities in RAS variants in thyroid tumors based on the fifth World Health Organization classification of thyroid neoplasms and assess their diagnostic significance in cancer detection among patients with thyroid nodules.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective diagnostic study analyzed surgically resected thyroid tumors obtained from February 2016 to April 2022 and residual thyroid fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies obtained from January 2020 to March 2021, at Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Data were analyzed from June 20, 2022, to October 15, 2023.

Exposures

Quantitative detection of interpatient disparities of RAS variants (ie, NRAS, HRAS, and KRAS) was performed along with assessment of BRAF V600E and TERT promoter variants (C228T and C250T) by detecting their variant allele fractions (VAFs) using digital polymerase chain reaction assays.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Interpatient differences in RAS, BRAF V600E, and TERT promoter variants were analyzed and compared with surgical histopathologic diagnoses. Malignancy rates, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values, and negative predictive values were calculated.

Results

A total of 438 surgically resected thyroid tumor tissues and 249 thyroid nodule FNA biopsies were obtained from 620 patients (470 [75.8%] female; mean [SD] age, 50.7 [15.9] years). Median (IQR) follow-up for patients who underwent FNA biopsy analysis and subsequent resection was 88 (50-156) days. Of 438 tumors, 89 (20.3%) were identified with the presence of RAS variants, including 51 (11.6%) with NRAS, 29 (6.6%) with HRAS, and 9 (2.1%) with KRAS. The interpatient differences in these variants were discriminated at VAF levels ranging from 0.15% to 51.53%. The mean (SD) VAF of RAS variants exhibited no significant differences among benign nodules (39.2% [11.2%]), noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTPs) (25.4% [14.3%]), and malignant neoplasms (33.4% [13.8%]) (P = .28), although their distribution was found in 41.7% of NIFTPs and 50.7% of invasive encapsulated follicular variant papillary thyroid carcinomas (P < .001). RAS variants alone, regardless of a low or high VAF, were significantly associated with neoplasms at low risk of tumor recurrence (60.7% of RAS variants vs 26.9% of samples negative for RAS variants; P < .001). Compared with the sensitivity of 54.2% (95% CI, 48.8%-59.4%) and specificity of 100% (95% CI, 94.8%-100%) for BRAF V600E and TERT promoter variant assays, the inclusion of RAS variants into BRAF and TERT promoter variant assays improved sensitivity to 70.5% (95% CI, 65.4%-75.2%), albeit with a reduction in specificity to 88.8% (95% CI, 79.8%-94.1%) in distinguishing malignant neoplasms from benign and NIFTP tumors. Furthermore, interpatient differences in 5 gene variants (NRAS, HRAS, KRAS, BRAF, and TERT) were discriminated in 54 of 126 indeterminate FNAs (42.9%) and 18 of 76 nondiagnostic FNAs (23.7%), and all tumors with follow-up surgical pathology confirmed malignancy.

Conclusions and Relevance

This diagnostic study delineated interpatient differences in RAS variants present in thyroid tumors with a variety of histopathological diagnoses. Discrimination of interpatient variabilities in RAS in combination with BRAF V600E and TERT promoter variants could facilitate cytology examinations in preoperative precision malignancy diagnosis among patients with thyroid nodules.

Introduction

Thyroid cancer, especially papillary thyroid cancer (PTC), has experienced a rapid increase in incidence since the 1980s1 and is primarily diagnosed through ultrasonographic examinations and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy of suspicious nodules.2,3 However, approximately 30% of FNAs exhibit an indeterminate diagnosis, and 10% of findings are nondiagnostic.4 Patients with indeterminate thyroid nodule findings usually undergo diagnostic surgery, with 20% to 30% of nodules being detected as malignant. Thus, up to 70% to 80% of patients with indeterminate nodules found histologically benign have undergone unnecessary surgical procedures. Patients with nondiagnostic cytological findings are typically recommended for a repeat FNA, with 13% of nodules detected as being malignant.4 Cancer arises along with genetic alterations. Molecular assays of FNA specimens are being increasingly used to enhance preoperative diagnostic accuracy for patients with indeterminate cytological findings and avoid unnecessary surgery for benign thyroid nodules.2,5

RAS is the most frequently variated gene family in human cancer. Approximately 19% of patients with cancer harbor activating variations from 3 RAS gene isoforms: NRAS (OMIM 164790) in 17% of patients, HRAS (OMIM 190020) in 7% of patients, or KRAS (OMIM 190070) in 75% of patients.6 Similarly, RAS variants are the second most common alterations in thyroid nodules, with NRAS variants being the dominant isoform followed by HRAS and KRAS.7,8,9,10 In thyroid tumors, RAS gene variations are detected in tumors spanning a wide spectrum of histological diagnoses, with a prevalence of 10% to 30% in PTC,11,12,13 40% to 50% in follicular thyroid carcinomas (FTCs),14,15 12% to 85% in follicular adenoma or hyperplasia, and 5% to 46% in noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTPs).14,16 Indeterminate thyroid nodules carrying RAS variants have shown malignancy rates varying from 9% to 83%,7,8,9,10,17 and such discrepancies can be primarily attributed to the use of small patient cohorts in these studies. Despite the widespread application of RAS variants in panel tests, assays of RAS variants often yield inconclusive results in detecting malignancy of thyroid nodules, frequently leading to a diagnostic surgery.2,12,18 On the contrary, BRAF V600E and TERT promoter variants (C228T and C250T) are the most frequently detected genetic variants in thyroid nodules, providing a more definitive basis for cancer diagnosis.19,20,21

Interpatient variabilities in genomic variants may reflect differences in tumor statuses among individuals.20 However, the diagnostic impact of discriminating interpatient variabilities of RAS variants on cancer detection remains unclear, particularly under the 2022 updated fifth World Health Organization (WHO) classification of thyroid neoplasms.22 In alignment with the WHO classification, the 2023 Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology (BSRTC)23 has updated nomenclature for each of the 6 diagnostic categories: I, nondiagnostic (ND); II, benign; III, atypia undetermined significance (AUS); IV, follicular neoplasm (FN); V, suspicious for malignancy (SFM); and VI, malignant.23 Currently, the methods of detecting RAS variations are mainly based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing (NGS). This study aimed to delineate interpatient disparities of RAS variants in thyroid tissues by quantifying variant allele fraction (VAF) using digital PCR (dPCR) assays and to examine their diagnostic associations with the preoperative detection of malignancy among patients with thyroid nodules.

Methods

This prospective diagnostic study was reviewed and approved by the Sinai Health Research Ethics Bord. All patients provided written informed consent, and samples were deidentified for data analysis. Data are reported in alignment with the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) reporting guideline.

Patients and Clinical Samples

A total of 438 thyroid tissue specimens were obtained from surgically resected thyroid tumors with a maximum dimension of 1 cm or larger from 436 consecutive patients who underwent surgery between February 1, 2016, and April 4, 2022, and 249 FNA specimens were collected from 234 consecutive patients who underwent biopsy procedures between January 22, 2020, and March 2, 2021, at Mount Sinai Hospital, Sinai Health, Toronto, Canada. All surgical tissue specimens sampled were quickly placed in liquid nitrogen and transferred to −80 °C for long-term preservation. As for preoperative biopsies, all FNAs were routinely obtained under ultrasonographic guidance using a 23-gauge needle and subjected to CytoLyte (Hologic) fixation. After cytological examination according to the BSRTC,4,23 the leftover materials of a total of 249 FNA biopsies were collected and stored at 4 °C until DNA purification. These preoperative biopsies primarily included ND and indeterminate (BSRTC categories I, III, IV, and V) specimens, along with some malignant (BSRTC category VI) and benign (BSRTC category II) specimens. A follow-up of thyroid nodules was conducted among patients who had previously undergone FNA procedures and subsequently underwent surgery. The patient clinical records, surgical pathology reports, and hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections were reviewed. The final histological diagnoses were made in accordance with the fifth WHO classification of thyroid neoplasms22 and Protocol for the Examination of Specimens From Patients With Carcinomas of the Thyroid Gland.24 Patients with cancer were further stratified as having low, intermediate, or high risk of recurrence based on the 2015 American Thyroid Association guidelines.25

Droplet dPCR Assays of RAS, BRAF V600E, and TERT promoter variants

Molecular assays for the most prevalent RAS variants of 3 RAS genes, NRAS (Q61R or Q61K), HRAS (Q61R or Q61K), and KRAS (G12C, G12D, G12V, G12A, or G13D), were developed using locked nucleic acid probe–based droplet dPCR by following the strategy and procedures recently established for the VAF assays of BRAF V600E and TERT promoter variants (C228T and C250T).20,26 The details of DNA extraction, dPCR assays, and verification of RAS variants using PCR and Sanger sequencing were documented in the eMethods in Supplement 1.

Statistical Analysis

Data were summarized as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and SDs for continuous variables. Blinded central review–based 2022 WHO histologic classification and 2023 BSRTC were used as the reference standard.22,23 The continuous parametric variables were compared by t test or 1-way analysis of variance test. Associations between molecular status and the clinicopathological characteristics were assessed by χ2 or Fisher exact test with 95% CIs. Statistical tests were conducted using SPSS software version 22.0 (IBM). P values were 2-sided, with P < .05 considered statically significant. Data were analyzed from June 20, 2022, to October 15, 2023.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Patients and Thyroid Specimens

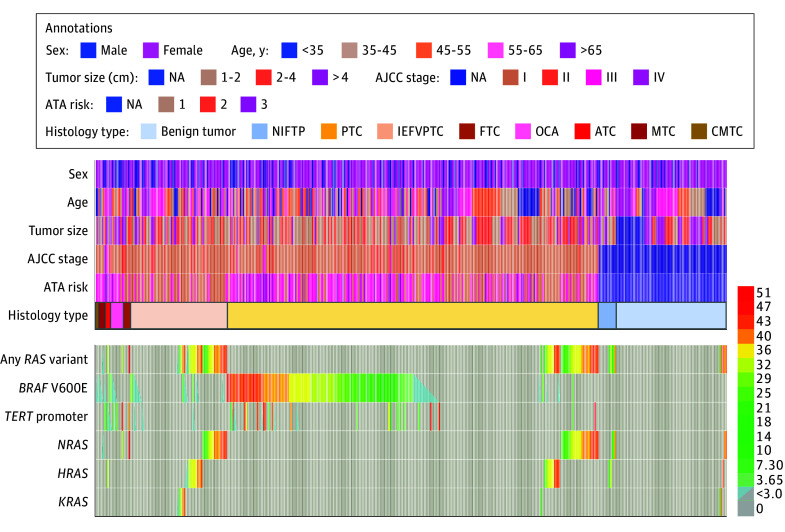

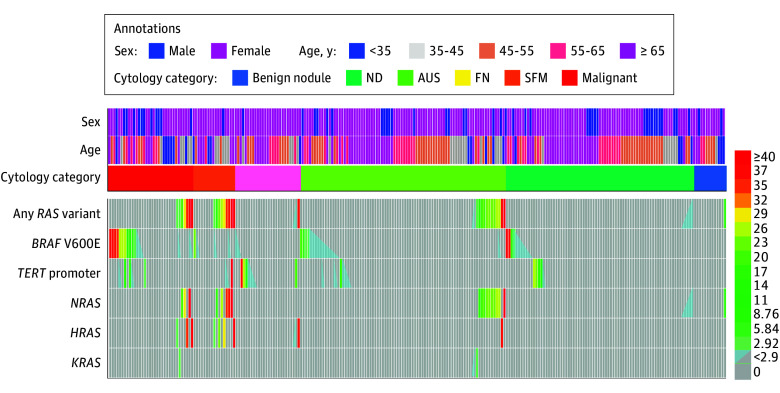

A total of 438 surgically resected thyroid tumor tissues and 249 thyroid nodule FNA biopsies were obtained from 620 patients (470 [75.8%] female; mean [SD] age, 50.7 [15.9] years). Of 438 thyroid tumors, 431 were follicular cell-derived neoplasms, comprising 77 benign tumors (thyroid follicular nodular disease, follicular adenoma, or oncocytic adenoma), 12 NIFTPs, and 343 malignant neoplasms, including 258 PTCs, 67 invasive encapsulated follicular variant PTCs (IEFVPTCs), 5 FTCs, 10 oncocytic carcinomas of the thyroid (OCAs), and 3 anaplastic thyroid carcinomas (ATCs). The cohort also included 5 medullary thyroid carcinomas (MTCs) and 2 cribriform morular thyroid carcinomas (CMTCs) (Figure 1 and Table 1; eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Hence the surgical tumor cohort exhibited a high tumor malignancy rate of 79.7% (95% CI, 75.5%-83.3%). In a separate cohort of 249 FNA biopsies, there were 76 (30.5%) with ND findings, 126 (50.6%) with indeterminate findings, 34 (13.7%) with malignant findings, and 13 (5.2%) with benign findings (Figure 2 and Table 2; eTable 2 in Supplement 1). The indeterminate FNAs comprised 83 AUS (65.9%), 26 FN (20.6%), and 17 SFM (13.5%).

Figure 1. Clinicomolecular Chacteristics of Interpatient Variabilities of RAS, BRAF V600E, and TERT Promoter Variants at the Variant Allele Fraction (VAF) Level in Thyroid Tumors.

AJCC indicates American Joint Committee on Cancer Cancer Staging Manual, 8th Edition; ATA, American Thyroid Association; ATC, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; CMTC, cribriform morular thyroid carcinoma; FTC, follicular thyroid carcinomas; IEFVPTC, invasive encapsulated follicular variant papillary thyroid carcinoma; MTC, medullary thyroid carcinomas; NA, not applicable; NIFTP, noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features; OCA, oncocytic carcinomas of the thyroid; and PTC, papillary thyroid carcinomas.

Table 1. Association of VAF Assay Findings of RAS Variants With Clinicohistopathologic Features of Thyroid Tumors.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | P valuea,b | Patients with RAS VAF>0 | P valueb | Patients by RAS variant, No. (%) | P valueb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | RAS VAF = 0 | RAS VAF > 0 | VAF < 1 | VAF ≥ 1 | HRAS | KRAS | NRAS | ||||

| Sample | 438 (100) | 349 (79.7) | 89 (20.3) | NA | 5 (1.1) | 84 (19.2) | NA | 29 (6.6) | 9 (2.1) | 51 (11.6) | NA |

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Male | 113 (25.8) | 93 (26.6) | 20 (22.5) | .50 | 1 (20.0) | 19 (22.6) | .80 | 11 (37.9) | 1 (11.1) | 8 (15.7) | .11 |

| Female | 325 (74.2) | 256 (73.4) | 69 (77.5) | 4 (80.0) | 65 (77.4) | 18 (62.1) | 8 (88.9) | 43 (84.3) | |||

| Age, y | |||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 49.7 (15.2) | 50.3 (15.3) | 47.2 (14.4) | .08 | 39.5 (10.2) | 47.7 (14.6) | .11 | 49.3 (11.7) | 50.2 (14.5) | 45.5 (15.8) | .21 |

| <55 | 271 (61.9) | 211 (60.5) | 60 (67.5) | .27 | 5 (100) | 55 (65.5) | .17 | 18 (62.1) | 7 (77.8) | 35 (68.6) | .55 |

| ≥55 | 167 (38.1) | 138 (39.5) | 29 (32.6) | 0 | 29 (34.5) | 11 (37.9) | 2 (22.2) | 16 (31.4) | |||

| Thyroidectomy | |||||||||||

| Partial | 178 (40.6) | 131 (37.5) | 47 (52.8) | .01 | 2 (40.0) | 45 (53.6) | .02 | 19 (65.5) | 3 (33.3) | 25 (49.0) | .01 |

| Total | 260 (59.4) | 218 (62.5) | 42 (47.2) | 3 (60.0) | 39 (46.4) | 10 (34.5) | 6 (66.7) | 26 (51.0) | |||

| Tumor size, cmc | |||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.0 (1.9) | 3.0 (1.9) | 3.0 (1.9) | .98 | 3.1 (1.7) | 3.0 (1.9) | .98 | 2.8 (2.3) | 2.4 (0.9) | 3.2 (1.7) | .58 |

| 1-2 | 170 (40.7) | 137 (41.6) | 33 (37.1) | .13 | 2 (40.0) | 31 (36.9) | .35 | 13 (44.8) | 4 (44.4) | 16 (31.4) | .31 |

| 2-4 | 156 (37.3) | 115 (35.0) | 41 (46.1) | 2 (40.0) | 39 (46.4) | 12 (41.4) | 4 (55.6) | 24 (47.1) | |||

| >4 | 92 (22.0) | 77 (23.4) | 15 (16.9) | 1 (20.0) | 14 (16.7) | 4 (13.8) | 0 | 11 (21.6) | |||

| ETEd | |||||||||||

| None | 310 (88.8) | 232 (85.9) | 78 (98.7) | .002 | 5 (100) | 73 (98.6) | .002 | 25 (96.2) | 7 (100) | 46 (100) | .008 |

| Identified | 39 (11.2) | 38 (14.1) | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 1 (3.8) | 0 | 0 | |||

| LNMd | |||||||||||

| None | 240 (68.8) | 165 (61.1) | 75 (94.9) | <.001 | 4 (80.0) | 71 (95.9) | <.001 | 25 (96.2) | 6 (85.7) | 44 (95.7) | <.001 |

| Identified | 109 (31.2) | 105 (38.9) | 4 (5.1) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (4.1) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (4.3) | |||

| Capsular invasiond | |||||||||||

| None | 254 (72.8) | 221 (81.9) | 33 (41.8) | <.001 | 3 (60.0) | 30 (40.5) | <.001 | 11 (42.3) | 3 (42.9) | 19 (41.3) | <.001 |

| Identified | 95 (27.2) | 49 (18.1) | 46 (58.2) | 2 (40.0) | 44 (59.8) | 15 (57.7) | 4 (57.1) | 27 (58.7) | |||

| Lymphatic invasiond | |||||||||||

| None | 243 (69.6) | 169 (62.6) | 74 (93.7) | <.001 | 3 (60.0) | 71 (95.9) | <.001 | 26 (100) | 6 (85.7) | 42 (91.3) | <.001 |

| Identified | 106 (30.4) | 101 (37.4) | 5 (6.3) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (4.1) | 0 | 1 (14.3) | 4 (8.7) | |||

| Perineural invasiond | |||||||||||

| None | 322 (92.3) | 244 (90.4) | 78 (98.7) | .01 | 5 (100) | 73 (98.6) | .03 | 25 (96.2) | 7 (100) | 46 (100) | .08 |

| Identified | 27 (7.7) | 26 (9.6) | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 1 (3.8) | 0 | 0 | |||

| ATA malignant riskd | |||||||||||

| 0 | 89 (20.4) | 79 (22.6) | 10 (11.2) | <.001 | 0 | 10 (11.9) | <.001 | 3 (10.3) | 2 (22.2) | 5 (9.8) | <.001 |

| 1 | 148 (33.8) | 94 (26.9) | 54 (60.7) | 2 (40.0) | 52 (61.9) | 21 (72.4) | 6 (66.7) | 27 (52.9) | |||

| 2 | 201 (45.9) | 176 (50.4) | 25 (28.1) | 3 (60.0) | 22 (26.2) | 5 (17.2) | 1 (11.1) | 19 (37.3) | |||

| Histology | |||||||||||

| Benign | 77 (17.6) | 72 (20.6) | 5 (5.6) | <.001 | 0 | 5 (6.0) | <.001 | 1 (3.4) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (3.9) | <.001 |

| NIFTP | 12 (2.7) | 7 (2.0) | 5 (5.6) | 0 | 5 (6.0) | 2 (6.9) | 0 | 3 (5.9) | |||

| PTC | 258 (58.9) | 217 (62.2) | 41 (46.1) | 3 (60.0) | 38 (45.2) | 12 (41.4) | 2 (22.2) | 27 (52.9) | |||

| IEFVPTC | 67 (15.3) | 33 (9.5) | 34 (38.2) | 2 (40.0) | 32 (38.1) | 12 (41.4) | 5 (55.6) | 17 (33.3) | |||

| FTC | 5 (1.1) | 4 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.0) | |||

| OCA | 10 (2.3) | 9 (2.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.0) | |||

| CMTC | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| ATC | 3 (0.7) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 1 (3.4) | 0 | 0 | |||

| MTC | 4 (0.9) | 3 (0.9) | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 1 (3.4) | 0 | 0 | |||

Abbreviations: ATA, American Thyroid Association; ATC, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; CMTC, cribriform morular thyroid carcinoma; ETE, extrathyroidal extension; FTC, follicular thyroid carcinomas; IEFVPTC, invasive encapsulated follicular variant papillary thyroid carcinoma; LNM, lymph node metastasis; MTC, medullary thyroid carcinomas; NA, not applicable; NIFTP, noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features; OCA, oncocytic carcinomas of the thyroid; PTC, papillary thyroid carcinomas; VAF, variant allele fraction.

The VAF = 0 group was included as an additional group and an overall statistic test comparing all groups was conducted.

Assessed using χ2 or Fisher exact test (2-sided) for categorical variables and 1-way analysis of variance test for independent parametric continuous measures.

Analysis of 418 nodules for tumor sizes (329 RAS-negative and 89 RAS-positive nodules) due to lack of information for the missing nodules.

Analysis of 349 malignant tumors for tumor ETE, LNM, capsular invasion, lymphatic invasion, perineural invasion, and ATA malignancy risk (0, not available; 1, low risk of recurrence; 2, intermediate to high risk of recurrence).

Figure 2. Interpatient Variabilities of RAS, BRAF V600E, and TERT Promoter Variants at the Variant Allele Fraction Level in Residual Fine-Needle Aspiration Specimens.

AUS indicates atypia of undetermined significance; FN, follicular neoplasm; ND, nondiagnostic; and SFM, suspicious for malignancy.

Table 2. VAF Assay Findings of Residual Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy Specimens From Indeterminate, Malignant, and Benign Thyroid Nodules.

| Characteristics | Patients, No. (%) | Cytological category | P valuea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ND | AUS | FN | SFM | Malignant | Benign | |||

| Sample | 249 (100) | 76 (30.5) | 83 (33.3) | 26 (10.4) | 17 (6.8) | 34 (13.7) | 13 (5.2) | NA |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 53 (21.3) | 20 (26.3) | 17 (20.5) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (5.9) | 12 (35.3) | 2 (15.4) | .02 |

| Female | 196 (78.7) | 56 (73.7) | 66 (79.5) | 25 (96.2) | 16 (94.1) | 22 (64.7) | 11 (84.6) | |

| Age at biopsy, y | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 55.5 (15.6) | 57.7 (14.2) | 56.1 (15.7) | 59.0 (13.6) | 50.0 (18.6) | 50.4 (16.7) | 52.4 (17.2) | .10 |

| <55 | 124 (49.8) | 33 (43.4) | 42 (50.6) | 12 (46.2) | 10 (58.8) | 19 (55.9) | 8 (61.5) | .68 |

| ≥55 | 125 (50.2) | 43 (56.6) | 41 (49.4) | 14 (53.8) | 7 (41.2) | 15 (44.1) | 5 (38.5) | |

| RAS variants | ||||||||

| Absent | 213 (85.5) | 72 (94.7) | 70 (84.3) | 24 (92.3) | 8 (47.1) | 27 (79.4) | 12 (92.3) | <.001 |

| Any | 36 (14.5) | 4 (5.3) | 13 (15.7) | 2 (7.7) | 9 (52.9) | 7 (20.6) | 1 (7.7) | |

| HRAS | 10 (4.0) | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 2 (7.7) | 4 (23.5) | 3 (8.8) | 0 | <.001 |

| KRAS | 3 (1.2) | 0 | 2 (2.4) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.9) | 0 | |

| NRAS | 23 (9.2) | 4 (5.3) | 10 (12.0) | 0 | 5 (29.4) | 3 (8.8) | 1 (7.7) | |

| BRAF V600E variant | ||||||||

| Absent | 199 (79.9) | 65 (85.5) | 66 (79.5) | 24 (92.3) | 13 (76.5) | 18 (52.9) | 13 (100) | .001 |

| Present | 50 (20.1) | 11 (14.5) | 17 (20.5) | 2 (7.7) | 4 (23.5) | 16 (47.1) | 0 | |

| TERT promoter variants | ||||||||

| Absent | 224 (90.0) | 71 (93.4) | 77 (92.8) | 19 (73.1) | 15 (88.2) | 29 (85.3) | 13 (100) | .05 |

| Present | 25 (10.0) | 5 (6.6) | 6 (7.2) | 7 (26.9) | 2 (11.2) | 5 (14.7) | 0 | |

| BRAF and TERT variants | ||||||||

| Absent | 183 (73.5) | 62 (81.6) | 62 (74.7) | 17 (65.4) | 11 (64.7) | 18 (52.9) | 13 (100) | .005 |

| Present | 66 (25.5) | 14 (18.4) | 21 (25.3) | 9 (34.6) | 6 (35.3) | 16 (47.1) | 0 | |

| BRAF, TERT, and RAS variants | ||||||||

| Absent | 154 (61.8) | 58 (76.3) | 50 (60.2) | 16 (61.5) | 6 (35.3) | 12 (35.3) | 12 (92.3) | <.001 |

| Present | 95 (38.2) | 18 (23.7) | 33 (39.8) | 10 (38.5) | 11 (64.7) | 22 (64.7) | 1 (7.7) | |

Abbreviations: AUS, atypia undetermined significance; FN, follicular neoplasm; ND, nondiagnostic; SFM, suspicious for malignancy; and VAF, variant allele fraction.

χ2 or Fisher exact test (2-sided) for categorical variables and 1-way analysis of variance test for independent parametric continuous measures.

Interpatient Variabilities of NRAS, HRAS, and KRAS Variants in Thyroid Tumors

Molecular VAF assays were developed for the quantitative detection of RAS variants at single-nucleotide resolution positive for NRAS, HRAS, and KRAS in tumor tissues but not in the adjacent healthy tissue, which were verified by Sanger sequencing (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). Of 438 tumors that underwent surgery, 89 (20.3%) were identified with the presence of RAS variants, including 51 (11.6%) with NRAS, 29 (6.6%) with HRAS, and 9 (2.1%) with KRAS variants, in mutually exclusive existence from each other (Figure 1 and Table 1). When compared with the 3 RAS gene isoforms across all tumor subtypes, the profiles of interpatient variabilities were delineated at the VAF levels ranging from 0.15% to 51.53%, specifically from 0.59% to 51.53% for NRAS, from 0.36% to 43.56% for HRAS, and from 0.15% to 46.64% for KRAS variants, with no significant difference among 3 isoforms (P = .16) (Figure 1; eFigure 2 in Supplement 1). Of these variants, 84 (94.4%) exhibited a VAF of greater than 1% and 5 showed a VAF of less than 1%, with 1 NRAS, 2 HRAS, and 2 KRAS variants. RAS variants were found in 5 benign neoplasms (6.4%), 5 NIFTPs (41.7%), and 79 malignant neoplasms (22.6%) (P < .001). Of 79 malignant neoplasms, 41 (51.9%) were PTCs, from 15.9% of total PTCs; 34 (43.0%) were IEFVPTCs, from 50.7% of total IEFVPTCs; and 4 (5.3%) comprised 1 each of FTCs, OCAs, ATCs, and MTCs, from 17.4% of all these carcinomas (P < .001) (Figure 1 and Table 1). Detection of RAS variants yielded a sensitivity of 22.6% (95% CI, 18.3%-27.0%), specificity of 88.8% (95% CI, 82.2%-95.3%), positive predictive value (PPV) of 88.8% (95% CI, 82.2%-95.3%), and negative predictive value (NPV) of 22.6% (95% CI, 18.3%-27.0%) in distinguishing malignant neoplasms from benign and NIFTP tumors (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). Notably, the VAF distribution of RAS variants was not statistically different among benign, NIFTP, and malignant neoplasms, as well as between PTCs and IEFVPTCs (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1), despite a high incidence of RAS variants in both NIFTPs (5 of 12 tumors [41.7%]) and IEFVPTCs (34 of 67 tumors [50.8%]). RAS variants, whether at a low or high VAF, were significantly associated with tumors undergoing partial thyroidectomy, with tumors absent for extrathyroidal extension, lymph node metastasis, capsular invasion, lymphatic invasion, or perineural invasion (Table 1). In addition, RAS variants alone had a significant association with a low-risk recurrence of thyroid carcinomas (Table 1).

RAS, BRAF V600E, and TERT Promoter Variants in Thyroid Carcinomas

Of 340 well-differentiated thyroid carcinomas, 77 (22.6%) were detected with RAS variants, including 46 (13.5%) with NRAS, 25 (7.4%) with HRAS, and 6 (1.8%) with KRAS. In addition, interpatient variabilities of BRAF V600E and TERT promoter variants (C228T and C250T) were detected in 173 (50.9%) and 55 (16.2%) carcinomas, respectively, with 45 (13.2%) of them in coexistence. Hence, there were 100 carcinomas (29.4%) with neither RAS nor BRAF V600E or TERT promoter variants (Figure 1; eTable 1 in Supplement 1). RAS variants were distributed in 41 PTCs, including 34 classical subtypes (CPTCs), 3 infiltrative follicular subtypes (IFPTCs), and 4 tall, hobnail, or columnar cell subtypes (thcPTCs); 34 IEFVPTCs; and 1 each of FTC and OCA (P < .001) (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Of 41 RAS variant PTCs, 6 (14.6%) coharbored BRAF V600E alone: 4 in CPTCs and 1 in each of IFPTC and thcPTC; 4 (9.8%) coharbored TERT promoter variants alone: 3 in CPTCs and 1 in thcPTC; and 2 (4.9%) coharbored both BRAF V600E and TERT promoter variants: 1 in each of CPTC and thcPTC. Of 34 RAS variant IEFVPTCs, 5 (14.7%) coexisted with BRAF V600E alone and 1 (2.9%) coexisted with both BRAF V600E and TERT promoter variants. For an additional 2 carcinomas with RAS variants, 1 in ATC was found coexisting with both BRAF V600E and TERT promoter variants, and the other in MTC coexisting with BRAF V600E alone. Of 57 malignant tumors harboring RAS variants alone, 29 (50.9%) were found in PTCs, with 26 CPTCs, 2 IFPTCs, and 1 thcPTC, and 28 (49.1%) were found in IEFVPTCs. No RAS variants were detected in the 2 CMTC tumors, but 1 CMTC tumor presented with the coexistence of BRAF V600E and TERT promoter variants. The inclusion of RAS variants into BRAF and TERT variant assays reached a sensitivity of 70.5% (95% CI, 65.4%-75.2%) and a specificity of 88.8% (95% CI, 79.8%-94.1%), with a PPV of 96.1% (95% CI, 92.7%-98.0%) and an NPV of 43.4% (95% CI, 36.2%-50.9%) in distinguishing malignant neoplasms from benign and NIFTP tumors. This represents a 30.2% increase in sensitivity but a 11.2% decrease in specificity compared with BRAF and TERT variant assays alone, which had a sensitivity of 54.2% (95% CI, 48.8%-59.4%) and specificity of 100% (95% CI, 94.8%-100%) (eTable 3 in Supplement 1).

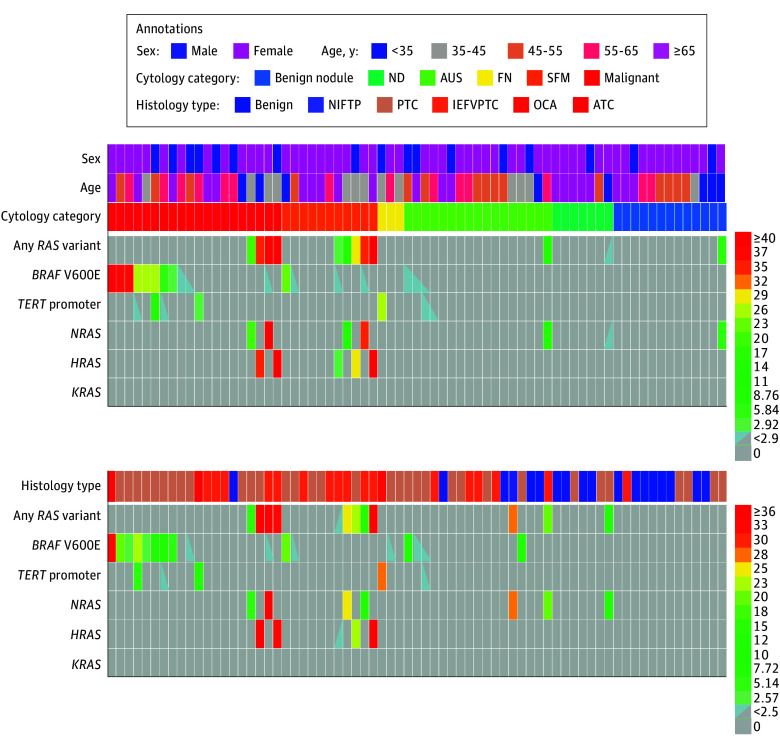

RAS, BRAF V600E, and TERT Promoter Variants in Preoperative Thyroid Nodules

VAF assays of 249 residual FNA specimens identified 36 specimens (14.5%) with RAS variants with interpatient variabilities (including 23 FNAs [9.2%] with NRAS, 10 FNAs [4.0%] with HRAS, and 3 FNAs [1.2%] with KRAS), 50 specimens (20.1%) with BRAF V600E, and 25 FNAs (10.0%) with TERT promoter variants (Figure 2 and Table 2). Of 36 FNA specimens with RAS variants, 28 (77.8%) had RAS variants alone in various BSRTC categories (4 ND, 9 AUS, 1 FN, 5 SFM, 5 malignant, and 1 benign); 5 (13.9%) coexisted with BRAF V600E: 1 AUS, 2 SFM, and 2 malignant; and 3 (8.3%) coexisted with TERT promoter variants: 1 FN and 2 SFM. Interpatient differences in the 5 gene variants (NRAS, HRAS, KRAS, BRAF, and TERT) were detected in 54 of 126 indeterminate FNAs (42.9%) and 18 of 76 ND FNAs (23.7%). During a median (IQR) follow-up of 88 (50-156) days for patients who underwent resections, VAF assays of 71 residual FNAs achieved a sensitivity of 56.6% (95% CI, 42.4%-69.9%), specificity of 100% (95% CI, 85.9%-100%), PPV of 100% (95% CI, 85.9%-100%), and NPV of 43.9% (95% CI, 28.8%-60.1%) in differentiating malignancy based on their surgical pathological findings (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). Of these FNAs, 12 (16.9%) had RAS variants (9 with RAS variants alone and 3 coexisting with BRAF V600E). Histopathologic outcomes confirmed all 12 (25.4%) nodules were malignant neoplasms, including 5 CPTCs and 7 IEFVPTCs (Figure 3; eTable 2 in Supplement 1). All FNAs with RAS variants coexisting with BRAF V600E (except for the patient with AUS, who was not available for follow-up) were subsequently found as IEFVPTC. In addition, among 18 nodules (25.4%) identified without RAS variants but with BRAF V600E or TERT promoter variants in the prior FNAs (9 with BRAF V600E alone, 3 with TERT promoter alone, and 4 in coexistence with both variants), 14 were subsequently found as PTC, with 12 for CPTC and 2 for thcPTC; 2 were found as ATC; and 1 each was found as IEFVPTC and OCA. Among 41 nodules (57.8%) identified with neither RAS, BRAF V600E, nor TERT promoter variants, 17 were benign tumors, 1 was NIFTP, 14 were CPTCs, and 9 were IEFVPTCs. Of note, 1 nodular goiter with an NRAS variant in its prior FNA was later confirmed as CPTC. Compared with the 5 gene variants detected in the matched surgical specimens, VAF assays on residual FNA biopsies exhibited a high agreement (κ = 0.799; P < .001) (Figure 3) and demonstrated a sensitivity of 87.1% (95% CI, 69.2%-95.8%), specificity of 92.5% (95% CI, 78.5%-98.0%), PPV of 90.0% (95% CI, 72.3%-97.4%), and NPV of 90.2% (95% CI, 75.9%-96.8%).

Figure 3. Correlation of Variant Allele Fraction (VAF) Assays of RAS, BRAF V600E, and TERT Promoter Variants Between Residual Fine-Needle Aspiration Specimens and Follow-Up Surgical Thyroid Tumors.

ATC indicates anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; AUS, atypia of undetermined significance; FN, follicular neoplasm; IEFVPTC, invasive encapsulated follicular variant papillary thyroid carcinoma; ND, nondiagnostic; NIFTP, noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features; OCA, oncocytic carcinomas of the thyroid; PTC, papillary thyroid carcinomas; and SFM, suspicious for malignancy.

Discussion

In this diagnostic study, interpatient variabilities in RAS variants were delineated in thyroid tumors with VAFs ranging from 0.15% to 51.53% using sensitive VAF assays. While RAS variants alone, regardless of the VAF levels, were associated with thyroid cancer in 88.8% of thyroid nodules harboring such variants, they did not definitively distinguish malignant tumors from NIFTP and benign ones. However, they did facilitate the stratification of low-risk tumors from high-risk ones among malignant neoplasms. Furthermore, interpatient differences in the 5 gene variants were discriminated in 42.9% of indeterminate FNAs, 23.7% ND FNAs, and all FNAs with follow-up surgical pathology-confirmed malignancy.

Currently, molecular assays of RAS variants do not effectively risk stratify tumors due to their limited sensitivities and specificities.27,28 In our study, the sensitive VAF assays identified substantial interpatient differences in the most common RAS gene variants, including 57.3% of NRAS variants in predominance, 33.7% of HRAS variants, and 9.0% of KRAS variants. In a comparable PTC cohort from The Cancer Genome Atlas study, the prevalence of RAS variants was 12.9% in PTCs, including 8.5% with NRAS, 3.5% with HRAS, and 1.0% with KRAS, based on NGS assays.11 In contrast, our study observed a prevalence of 23.1% for RAS variants in PTCs, classified by the 2017 WHO classification,29 including 13.5% with NRAS, 7.4% with HRAS, and 2.2% with KRAS (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1), suggesting that VAF assays revealed higher frequencies of RAS variants in thyroid neoplasms. Hence, significant discrepancies from different methods of detecting genomic variants may result in false-negative results or missed diagnoses of clinical significance, particularly when methods with lower sensitivities are used.28,30 In addition, a high agreement observed in VAF assays between residual FNA biopsies and matched surgical specimens underscores the clinical significance of using residual specimens. At a direct cost of $12.36 per laboratory-developed test reaction coupled with a turnaround time within 8 hours from specimen receipt to result (eTable 4 in Supplement 1), this approach facilitates the timely and rapid delivery of molecular results concurrently with cytological examination on the same source biopsies, holding promise as an effective addition to existing protocols for personalized thyroid cancer care.

High rates of RAS variants were identified in lesions exhibiting follicular architecture, such as NIFTP (41.7%) and IEFVPTC (50.7%). It is noteworthy that 70.6% of CPTCs carrying RAS variants exhibited a predominantly follicular growth pattern, with most of them presenting encapsulation. Unfortunately, discriminating variant differences did not improve the stratification power of RAS variants in distinguishing between malignant neoplasms and NIFTPs, follicular adenomas, or oncocytic adenomas, nor between lesions exhibiting differential follicular architecture, such as NIFTP and IEFVPTC neoplasms. The limited effectiveness of RAS variants in stratifying these histological types may be attributed to their close similarity in gene expression profiles.27,31,32 Moreover, low VAF events of RAS variations, including those at VAF less than 1%, were associated with an equally high risk of cancer as high VAF events. This finding aligns with that of a 2017 study that reported an equivalent malignancy rate in RAS variants detected at VAF less than 10% compared with variants detected at VAF greater than 10%.8 Further studies are needed to elucidate the biological role and clinical significance of the different extents of RAS variations in tumor development.33,34,35

The widespread implementation of molecular assays as routine cancer diagnosis remains a challenge. First, interpretation of genomic variations can be complex and may vary due to interpatient differences in such variants.36,37,38 RAS variants alone, including the low VAF events, do not confirm the malignancy of an unknown tumor; therefore, they should not solely dictate clinical decisions.39 However, RAF variants do enhance the stratification of low-risk tumors,12,27 aiding in informing the extent of operation. Second, BRAF V600E and TERT promoter variants were detected exclusively in malignant tumors and exhibited a stronger association with aggressive tumor behaviors, aligning with our prior findings and those of other studies.20,21,40,41 The inclusion of RAS variants into BRAF V600E and TERT promoter variant assays significantly enhanced the sensitivity for malignancy detection, albeit with a trade-off of reduced specificity. In addition, RAS variants coexisting with BRAF V600E and/or TERT promoter variants tend to be enriched in high-risk cancers, such as thcPTC, FTC, OCA, ATC, and MTC.42,43,44 Third, search for novel molecular markers is needed to screen the rest 29.5% of malignant tumors and 64.4% of thyroid nodules that did not have BRAF V600E, TERT promoter variants, or RAS variants. Hence, leveraging NGS with a high-fidelity read capability may help identify additional actionable molecular alterations for detecting malignancy among tumors negative for RAS, BRAF, and TERT variants.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. This study was conducted at a single center, where our surgical tumor cohort exhibited a high tumor malignancy rate, potentially contributing to the observed high prevalence of RAS variants in malignant tumors. With its ultrasensitivity in absolute quantification, VAF assay stands out as a favorable choice for testing known and definitive biomarkers, be they single variants or a small panel of variants, particularly when dealing with low variant levels. However, VAF assay has a relatively limited capacity of detecting multiple genomic variants in a single reaction. To reinforce the clinical utility of our findings, further larger-scale multicenter validation is necessary, using sensitive VAF assays targeting RAS in conjunction with other genomic variants.

Conclusions

This diagnostic study delineated interpatient variabilities of RAS variants in thyroid tumors with various histopathological diagnoses. These findings suggest that discrimination of interpatient differences in RAS in combination with BRAF V600E and TERT promoter variants could facilitate cytology examinations in preoperative precision malignancy diagnosis among patients with thyroid nodules.

eMethods.

eTable 1. Association of Variant Allele Fraction of RAS and BRAF V600E and TERT Promoter Variants With Clinicohistopathologic Features of Well-Differentiated Thyroid Tumors

eTable 2. Surgical Pathology Follow-up of Variant Allele Fraction Assays of RAS, BRAF V600E, and TERT Promoter Variants on the Residual FNA Biopsy Specimens From Thyroid Nodules

eTable 3. Performance of Variant Allele Fraction Assays of RAS and BRAF and TERT Variants in Differentiating Malignancy Among Thyroid Surgical Tumors and Preoperative Thyroid Nodules

eTable 4. Direct Cost of Laboratory Developed Tests for Variant Allele Fraction Assays

eFigure 1. Detection and Quantification of HRAS, NRAS, and KRAS Variants by dPCR Assays and Verification by Sanger Sequencing

eFigure 2. Variant Allele Fraction Distributions Across 3 RAS Gene Isoforms in Thyroid Tumors and Different Histology Diagnoses

eFigure 3. Clinicomolecular Characteristics of Interpatient Variabilities of RAS, BRAF V600E, and TERT Promoter Variants at the Variant Allele Fraction Level in Papillary Thyroid Carcinomas (PTC) Classified by The 2017 WHO Classification of Thyroid Neoplasms

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):1-133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoo WS, Choi HS, Cho SW, et al. The role of ultrasound findings in the management of thyroid nodules with atypia or follicular lesions of undetermined significance. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2014;80(5):735-742. doi: 10.1111/cen.12348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali SZ, Cibas ES. The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. 2nd ed. Springer; 2018. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-60570-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durante C, Grani G, Lamartina L, Filetti S, Mandel SJ, Cooper DS. The diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules: a review. JAMA. 2018;319(9):914-924. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prior IA, Hood FE, Hartley JL. The frequency of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 2020;80(14):2969-2974. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-3682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taye A, Gurciullo D, Miles BA, et al. Clinical performance of a next-generation sequencing assay (ThyroSeq v2) in the evaluation of indeterminate thyroid nodules. Surgery. 2018;163(1):97-103. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel SG, Carty SE, McCoy KL, et al. Preoperative detection of RAS mutation may guide extent of thyroidectomy. Surgery. 2017;161(1):168-175. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.04.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikiforov YE, Carty SE, Chiosea SI, et al. Highly accurate diagnosis of cancer in thyroid nodules with follicular neoplasm/suspicious for a follicular neoplasm cytology by ThyroSeq v2 next-generation sequencing assay. Cancer. 2014;120(23):3627-3634. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinmetz D, Kim M, Choi JH, et al. How effective is the use of molecular testing in preoperative decision making for management of indeterminate thyroid nodules? World J Surg. 2022;46(12):3043-3050. doi: 10.1007/s00268-022-06744-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network . Integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell. 2014;159(3):676-690. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta N, Dasyam AK, Carty SE, et al. RAS mutations in thyroid FNA specimens are highly predictive of predominantly low-risk follicular-pattern cancers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(5):E914-E922. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yip L, Nikiforova MN, Yoo JY, et al. Tumor genotype determines phenotype and disease-related outcomes in thyroid cancer: a study of 1510 patients. Ann Surg. 2015;262(3):519-525. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nikiforova MN, Lynch RA, Biddinger PW, et al. RAS point mutations and PAX8-PPAR gamma rearrangement in thyroid tumors: evidence for distinct molecular pathways in thyroid follicular carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(5):2318-2326. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsiao SJ, Nikiforov YE. Molecular approaches to thyroid cancer diagnosis. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21(5):T301-T313. doi: 10.1530/ERC-14-0166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcadis AR, Valderrabano P, Ho AS, et al. Interinstitutional variation in predictive value of the ThyroSeq v2 genomic classifier for cytologically indeterminate thyroid nodules. Surgery. 2019;165(1):17-24. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2018.04.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shrestha RT, Evasovich MR, Amin K, et al. Correlation between histological diagnosis and mutational panel testing of thyroid nodules: a two-year institutional experience. Thyroid. 2016;26(8):1068-1076. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nikiforova MN, Mercurio S, Wald AI, et al. Analytical performance of the ThyroSeq v3 genomic classifier for cancer diagnosis in thyroid nodules. Cancer. 2018;124(8):1682-1690. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang CF, Yang MH, Lee JH, et al. The impact of BRAF targeting agents in advanced anaplastic thyroid cancer: a multi-institutional retrospective study in Taiwan. Am J Cancer Res. 2022;12(11):5342-5350. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu G, Chazen RS, Monteiro E, et al. Facilitation of definitive cancer diagnosis with quantitative molecular assays of BRAF V600E and TERT promoter variants in patients with thyroid nodules. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2323500. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.23500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xing M, Liu R, Liu X, et al. BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations cooperatively identify the most aggressive papillary thyroid cancer with highest recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(25):2718-2726. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.5094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baloch ZW, Asa SL, Barletta JA, et al. Overview of the 2022 WHO classification of thyroid neoplasms. Endocr Pathol. 2022;33(1):27-63. doi: 10.1007/s12022-022-09707-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali SZ, Baloch ZW, Cochand-Priollet B, Schmitt FC, Vielh P, VanderLaan PA. The 2023 Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Thyroid. 2023;33(9):1039-1044. doi: 10.1089/thy.2023.0141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seethala RR, Asa SL, Bullock MJ, et al. ; College of American Pathologists . Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with carcinomas of the thyroid gland. Accessed April 10, 2024. https://documents.cap.org/protocols/cp-endocrine-thyroid-19-4200.pdf

- 25.Hay ID, Bergstralh EJ, Goellner JR, Ebersold JR, Grant CS. Predicting outcome in papillary thyroid carcinoma: development of a reliable prognostic scoring system in a cohort of 1779 patients surgically treated at one institution during 1940 through 1989. Surgery. 1993;114(6):1050-1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu G, Chazen RS, MacMillan C, Witterick IJ. Development of a molecular assay for detection and quantification of the BRAF variation in residual tissue from thyroid nodule fine-needle aspiration biopsy specimens. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2127243. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.27243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernandez-Prera JC, Valderrabano P, Creed JH, et al. Molecular determinants of thyroid nodules with indeterminate cytology and RAS mutations. Thyroid. 2021;31(1):36-49. doi: 10.1089/thy.2019.0650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vasko V, Ferrand M, Di Cristofaro J, Carayon P, Henry JF, de Micco C. Specific pattern of RAS oncogene mutations in follicular thyroid tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(6):2745-2752. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lloyd RV, Osamura RY, Klèoppel G, Rosai J. WHO Classification of Tumours of Endocrine Organs. 4th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaya C, Dorsaint P, Mercurio S, et al. Limitations of detecting genetic variants from the RNA sequencing data in tissue and fine-needle aspiration samples. Thyroid. 2021;31(4):589-595. doi: 10.1089/thy.2020.0307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basolo F, Macerola E, Ugolini C, Poller DN, Baloch Z. The molecular landscape of noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP): a literature review. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24(5):252-258. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu B, Serrette R, Tuttle RM, et al. How many papillae in conventional papillary carcinoma: a clinical evidence-based pathology study of 235 unifocal encapsulated papillary thyroid carcinomas, with emphasis on the diagnosis of noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features. Thyroid. 2019;29(12):1792-1803. doi: 10.1089/thy.2019.0328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simanshu DK, Nissley DV, McCormick F. RAS proteins and their regulators in human disease. Cell. 2017;170(1):17-33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bos JL. RAS oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49(17):4682-4689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. RAS oncogenes: the first 30 years. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(6):459-465. doi: 10.1038/nrc1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Najafian A, Noureldine S, Azar F, et al. RAS mutations, and RET/PTC and PAX8/PPAR-gamma chromosomal rearrangements are also prevalent in benign thyroid lesions: implications thereof and a systematic review. Thyroid. 2017;27(1):39-48. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris LGT. Molecular profiling of thyroid nodules—are these findings meaningful, or merely measurable: a review. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(9):845-850. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.1851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Livhits MJ, Zhu CY, Kuo EJ, et al. Effectiveness of molecular testing techniques for diagnosis of indeterminate thyroid nodules: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(1):70-77. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.5935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Medici M, Kwong N, Angell TE, et al. The variable phenotype and low-risk nature of RAS-positive thyroid nodules. BMC Med. 2015;13:184. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0419-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mungan S, Ersoz S, Saygin I, Sagnak Z, Cobanoglu U. Nuclear morphometric findings in undetermined cytology: possible clue for prediction of BRAF mutation in papillary thyroid carcinomas. Endocr Res. 2017;42(2):138-144. doi: 10.1080/07435800.2016.1255895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xing M, Alzahrani AS, Carson KA, et al. Association between BRAF V600E mutation and mortality in patients with papillary thyroid cancer. JAMA. 2013;309(14):1493-1501. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.3190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landa I, Ibrahimpasic T, Boucai L, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic hallmarks of poorly differentiated and anaplastic thyroid cancers. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(3):1052-1066. doi: 10.1172/JCI85271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fagin JA, Wells SA Jr. Biologic and clinical perspectives on thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1054-1067. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1501993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu B, Fuchs T, Dogan S, et al. Dissecting anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: a comprehensive clinical, histologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 360 cases. Thyroid. 2020;30(10):1505-1517. doi: 10.1089/thy.2020.0086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.

eTable 1. Association of Variant Allele Fraction of RAS and BRAF V600E and TERT Promoter Variants With Clinicohistopathologic Features of Well-Differentiated Thyroid Tumors

eTable 2. Surgical Pathology Follow-up of Variant Allele Fraction Assays of RAS, BRAF V600E, and TERT Promoter Variants on the Residual FNA Biopsy Specimens From Thyroid Nodules

eTable 3. Performance of Variant Allele Fraction Assays of RAS and BRAF and TERT Variants in Differentiating Malignancy Among Thyroid Surgical Tumors and Preoperative Thyroid Nodules

eTable 4. Direct Cost of Laboratory Developed Tests for Variant Allele Fraction Assays

eFigure 1. Detection and Quantification of HRAS, NRAS, and KRAS Variants by dPCR Assays and Verification by Sanger Sequencing

eFigure 2. Variant Allele Fraction Distributions Across 3 RAS Gene Isoforms in Thyroid Tumors and Different Histology Diagnoses

eFigure 3. Clinicomolecular Characteristics of Interpatient Variabilities of RAS, BRAF V600E, and TERT Promoter Variants at the Variant Allele Fraction Level in Papillary Thyroid Carcinomas (PTC) Classified by The 2017 WHO Classification of Thyroid Neoplasms

Data Sharing Statement