Abstract

Objective:

This study examined if empathy was a significant moderator of several empirically established risk factors for sexual violence perpetration among college males.

Participants:

Data are from 544 college males who participated in a longitudinal study from 2008 to 2011 at a large, public university.

Methods:

Participants completed a self-report survey in their first through fourth years in college. A series of generalized linear models were conducted using sexual violence risk factors and empathy during the sophomore year as predictors of sexual violence perpetration frequency during junior year.

Results:

Empathy was found to be a significant moderator of six out of the ten sexual violence risk factors tested, such that high levels of empathy were associated with lower sexual violence perpetration rates among high-risk males.

Conclusions:

Additional research, including the measurement and evaluation of empathy in implementation of college sexual violence prevention and intervention efforts, should be undertaken.

Keywords: Empathy, Sexual Violence, Rape, Sexual Aggression

Introduction

Sexual violence is a serious, widespread public health concern on college campuses across the United States.1 Empathy, meanwhile, is a positive trait associated with numerous prosocial outcomes,2,3 and has been found to be malleable among college students.4 While there is a general consensus that there is an empathy deficit among sexual violence perpetrators,5 limited research has been conducted examining the relationship between empathy and sexual violence perpetration among college males. In their seminal article on sexual violence perpetration among young adult males, Malamuth, Linz, Heavey, Barnes, and Acker6 recommended that future longitudinal research examine the role of empathy in sexual aggression among young adults. The present study used longitudinal data to determine if empathy was a significant moderator of several empirically established risk factors of sexual violence perpetration among college males.

Prevalence of Sexual Violence among College Students

Sexual violence is defined as a completed or attempted sexual act committed against someone without that person’s freely given consent.7 Sexual violence has a range of negative consequences for physical, mental, and behavioral health, as well as for social and interpersonal relationships.8 College students represent a subpopulation at increased risk for sexual violence, and researchers have hypothesized that this might be due to the range of social situations common in college settings that increase interactions between young men and women.9 Various studies have shown that one in five to one in three female college students report being a victim of sexual violence,1, 8, 10 and as many as one in five college males have perpetrated sexual violence.11

Risk Factors for Sexual Violence Perpetration among College Males

Sexual violence perpetration among college males is associated with several empirically established risk factors. Peer pressure for sex and peer approval for forced sex have been found to be significant predictors of sexual violence, highlighting the importance of peer groups in facilitating or creating opportunities to be engaged in sexually violent actions.12 Alcohol consumption has been identified as a predictor of both single and repeat sexual violence, and one study found that 47% of college male perpetrators of attempted or completed rape had used incapacitation via alcohol or drugs as their tactic.13 Sexual compulsivity, a higher number of sexual partners, and exposure to pornography have been found to be significantly associated with sexual violence perpetration.13–15 In a longitudinal study of college males, Thompson, Swartout, and Koss15 found that hostility towards women was one of the most consistent predictors of sexual aggression across the college years. Rape supportive beliefs differentiated perpetrators from non-perpetrators in research analyzing group tactics in sexual aggression, and were associated with single and repeat sexual violence perpetration.11,13 Anger has also been associated with sexual aggression, and in high levels it may precipitate sexual violence.11 Finally, superficial charm, or social charm used for personal benefit rather than out of true care for another, predicted higher levels of sexual violence perpetration in a study of college males.13

Empathy among College Students

Empathy can be defined as “the natural capacity to share, understand, and respond with care to the affective states of others.”16(pvii) High levels of empathy are associated with a number of positive outcomes including other-oriented helping and prosocial behavior,3 volunteerism,2 and success in employment areas ranging from medicine to sales.17,18 Conversely, lower levels of empathy are associated with a number of antisocial outcomes including violent criminal offenses,19 child abuse,20 and sexual aggression.21

Given the numerous prosocial outcomes associated with empathy, and negative outcomes associated with a lack of empathy, empathy has been a growing area of interest for researchers concerned with college student development. A 2011 meta-analysis found evidence that empathy has declined among college students in recent decades. College students in the 2000s demonstrated lower scores on the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI), a common measure of empathy, compared to students in the 1980s and 1990s.22 However, a more recent longitudinal study found that many college males’ IRI scores underwent significant change from the freshman to senior years, with 51% of students demonstrating a significant increase in empathy, and 35% demonstrating a significant decrease.4 Empathy malleability during the college years is unsurprising in the context of the theory of emerging adulthood,23 which contends that emerging adults from the ages of 18–25 explore their identity in the areas of love, work, and worldviews before settling into the more permanent roles and responsibilities of adulthood. This period of identity exploration and new experiences appears to influence the development of empathy among college students.

Because empathy appears to be malleable among college students, any relationship between empathy and sexual violence among college males takes on an added layer of importance since it is an attribute that may continue to be developed while in college. For example, several studies have found evidence that short-term simulations and class exercises had a positive impact on empathy among college students,24,25 and that long-term involvement in positive extracurricular activities are associated with increases in empathy over the course of a student’s college career.4

Empathy and Sexual Violence Perpetration among College Males

Despite evidence that lack of empathy may influence sexual aggression,26 limited research has been done on this relationship among college males, although a lack of empathy was included in Van Brunt, Murphy, and O’Toole’s (2015) list of twelve risk factors for sexual violence on college campuses (DD-12).50 The Confluence Model of sexual aggression hypothesizes that sexual aggression results from the confluence of hostile masculinity beliefs and impersonal sex tendencies among sexually aggressive males.6 In a cross-sectional study of undergraduate college males, Wheeler, George, and Dahl,28 sought to expand the confluence model by introducing empathy as a moderator. They found that empathy moderated the influence of hostile masculinity and impersonal sex on sexual violence. Males with high levels of hostile masculinity and impersonal sex and low empathy reported higher rates of sexual violence perpetration than all other males in the study. Conversely, males with high levels of hostile masculinity and impersonal sex and high empathy reported sexual violence perpetration rates comparable with males who expressed lower levels of hostile masculinity and impersonal sex.

An examination of the role of empathy as a moderator of additional sexual violence perpetration risk factors, beyond the hostile masculinity and impersonal sex pathways included in the Confluence Model, could help to improve the understanding of the relationship between empathy and sexual violence among college males, and inform sexual violence prevention and intervention efforts on college campuses. The present study thus sought to determine if empathy was a moderator of several empirically established sexual violence perpetration risk factors. It was hypothesized that empathy would significantly moderate the effect of most risk factors on the frequency of sexual violence perpetration, such that males with low scores on risk factors and high levels of empathy would report the lowest levels of sexual violence frequency in the sample, and males with high scores on risk factors and high scores on empathy would report sexual violence frequency rates comparable to low-risk males with low levels of empathy.

Methods

Participants

Data for this analysis came from a 2008–2011 longitudinal study of college males at a large, public, southeastern university. Participants were recruited via email, newspaper, and flyers, resulting in a nonrandom, recruited sample. After providing informed consent, participants completed a 20–30 minute, 158-item survey at the campus health center on men’s attitudes and behaviors regarding relationships with women. A total of 800 participants completed the confidential survey in the spring semester of their first year of college during a one-week period in March-April 2008. Participants who completed the first wave of the survey were contacted via email to complete follow-up surveys in March-April 2009, 2010, and 2011. Participants received $20 for completing the survey at Waves 1 and 2, and $25 at Waves 3 and 4. The study was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board, and a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health prior to data collection.

In this analysis, the sample included participants who completed each of the first three waves of the study, so that measures assessed at both the Wave 2 and Wave 3 could be included in the present analyses. Additionally, five participants who were either under the age of 18 or over the age of 21 at Wave 1 were removed. The final sample for this analysis was N = 544.

Measures

Predictors

Sexual violence perpetration risk factors were selected from Wave 2 of the study. Definitions and citations for the measures are presented in Table 1, and a description of each measure is presented below. As indicated by the citations, all composite measures used in the study have been validated in previous studies.

Table 1.

Sexual Violence Risk Factors

| Risk Factor scale source | Definition |

|---|---|

| Peer Pressure for Sex33 | The pressure a man feels from his current friends to have sexual experiences or talk about them. |

| Peer Approval of Forced Sex34 | The extent to which a man perceives his current friends approve of various methods to obtain sex |

| Hostility Towards Women35 | Attitudes and opinions within the past year that indicate feelings of distrust for the actions and motives of women |

| Rape Supportive Beliefs36 | Attitudes and opinions from the past year that imply the respondent believes rape is the fault of the woman or okay under certain circumstances |

| High-Risk Alcohol Use37 | How many times and how much the respondent drank alcohol in the past 30 days |

| Sexual Compulsivity38 | The degree to which sexual appetites over the past year influenced daily thoughts and actions |

| Exposure to Pornography | The amount of hours per week spent looking at sexually explicit material |

| Superficial Charm39 | Whether the respondent has used charm and cunning to manipulate others for personal benefit |

| Anger39 | Frequency with which the respondent felt angry and did or said angry things |

| Number of Sexual Partners | Number of people respondent has had vaginal or anal sex with since the age of 14 |

Peer Pressure for Sex33 (α = .77) was measured using three items (e.g., “How much pressure do you feel from your friends to have sex with many different women?”) with responses ranging from not at all (1) to a lot (4). Higher scores indicated more perceived pressure to have sex.

The Peer Approval of Forced Sex34 scale (α = .79) consisted of six items (e.g., “To what extent would your current set of friends approve of getting a woman drunk or high in order to have sex with her?”), with responses ranging from not at all (1) to a lot (4). Higher scores indicated more perceived approval from friends for forced sex.

Hostility Towards Women35 (α = .92) was assessed with eight items (e.g., “It is safer not to trust women”). Response categories were a five-point Likert scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), and higher scores indicated greater hostility towards women.

The Rape Supportive Beliefs36 scale (α = .91) consisted of 19 items (e.g., “If a woman is raped, often it’s because she didn’t say “no” clearly enough”) with responses ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Higher scores represented attitudes supportive of rape.

High-Risk Alcohol Use37 (α = .92) was assessed using five questions originally used on the College Alcohol Survey (e.g., “On how many occasions have you had a drink of alcohol in the past 30 days”). Higher scores indicated greater levels of risky alcohol use.

The Sexual Compulsivity38 scale (α = .84) included ten items (e.g., “I have to struggle to control my sexual thoughts and behaviors”) with possible responses ranging from not at all (0) to a lot (4). Higher scores indicated that sexual thoughts and impulses disrupted daily life more frequently.

Exposure to pornography was assessed by a single question on the amount of time per week spent viewing sexually explicit material either in magazines or on the internet. The categories utilized in this analysis were none (16% of the sample), less than an hour (46%), 1–2 hours (25%), 3–4 hours (7%), and more than 5 hours (6%).

The Superficial Charm39 scale (α = .76) used six questions (e.g., “I have lied to someone to get them to do what I want them to”). Potential responses ranged from “definitely false” (1) to “definitely true” (5), with higher scores indicating more reported manipulation of others for personal benefit.

Anger39 (α = .87) was assessed using eight items (e.g., “I lose my temper easily”), and responses ranged from never (1) to very often (5). Higher scores indicated an angrier temperament.

Number of Sexual Partners was assessed by asking participants how many vaginal or anal sex partners they had since the age of 14.

Moderator

Empathy was measured during Wave 2 of the study using the Perspective Taking subscale of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index.36 Participants were asked to respond to each item on a five-point Likert scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Sample items from the scale include “I sometimes try to understand my friends better by imagining how things look from their perspective,” and “When I’m upset at someone, I usually try to ‘put myself in his shoes’ for a while.” One item typically found on the Perspective Taking subscale, “I believe that there are two sides to every question and try to look at them both,” had been omitted from the survey, resulting in a six-item scale. The scale showed adequate reliability (α = .72), which was consistent with reliability scores for the full Perspective Taking subscale in the original validation of the instrument among a sample of undergraduate college students (α = .75).40 Principal axis factor analysis revealed that all items in the measure adequately loaded on only one factor (factor loadings ranged from .33 to .76), indicating that the omission of one item did not change the structure of the Perspective Taking subscale. A mean score of the items was created, and higher scores indicated a greater level of empathy.

In the context of the present study, it is important to note that the Perspective Taking subscale of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index is a measure of empathy towards others in general, not specifically towards women or victims of sexual violence.

Outcome

Sexual violence perpetration was measured using the revised Sexual Experiences Survey,37 a widely used measure which has demonstrated good reliability and validity among samples of college students. The SES contains 35 items asking the respondent how often they have perpetrated or attempted to perpetrate specific types of sexual violence, with response options including 0, 1, 2, and 3 or more times. Sexual violence perpetration frequency at Wave 3 was calculated for participants by totaling the number of perpetrations committed during the summer after the second year of college and during the third year of college.

Analyses

In order to assess empathy as a moderator of risk factors for sexual violence perpetration, a series of generalized linear models were conducted including a centered Wave 2 risk factor, the centered Wave 2 empathy variable, and the interaction term between the risk factor and empathy as predictors of sexual violence perpetration frequency at Wave 3. Risk factors, empathy, and sexual violence perpetration were assessed in all four waves of the study, but Wave 3 was selected as the time point for the outcome measure due to a higher sexual violence frequency rate relative to other Waves, therefore maximizing the amount of potential variance observed in the models. Risk factors were assessed at Wave 2 in order to determine their impact on sexual violence perpetration one year later, and empathy was assessed as a moderator in Wave 2 in accordance with a “half-longitudinal” design.38 Because the sexual violence frequency data were not normally distributed, with a high proportion of non-perpetrators, the negative binomial distribution of sexual violence frequency was assessed in the model. This approach was derived from recommendations for analyzing sexual violence outlined by Swartout, Thompson, Koss, and Su,39 which emphasized the importance of modeling non-normally distributed frequency data appropriately in order to avoid faulty conclusions, and found that the negative binomial model was the best fit for this data.

Models which demonstrated significant two-way interactions underwent post-hoc probing using the method outlined by Holmbeck,40 where the zero point of the moderator was manipulated such that high empathy equaled zero when empathy was centered to one standard deviation above its mean, and low empathy equaled zero when empathy was centered to one standard deviation below its mean. New interaction terms that incorporated these conditional moderators were then computed, and two regression lines were plotted to test the association of each risk factor and sexual violence perpetration frequency under conditions of high and low empathy.

Results

The mean age of participants at Wave 2 was 19.6 years (SD = .51). Most participants in the sample were white (N = 483; 88.8%), and 7.7% of participants were African American (N = 42). About two thirds of participants described their hometown as suburban (N = 355; 65.3%), while 24.6% described their hometown as rural (N = 134), and 10.1% described their hometown as urban (N = 55). The mean score for the empathy measure within the sample was 3.51 (SD = 0.59, min. = 3.33, max. = 5.00). Total instances of self-reported sexual violence perpetrations ranged from 0 – 49, with 455 participants (83.9%) reporting no sexual violence perpetrations, 22 participants (4.1%) reporting one perpetration, 15 participants (2.8%) reporting two perpetrations, and 50 participants (9.2%) reporting three or more total perpetrations. Descriptive statistics for all prospective risk factors of sexual violence are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Sexual Violence Risk Factors

| Risk Factor scale source | Mean | SD | Min. | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer Pressure for Sex33 | 1.62 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Peer Approval of Forced Sex34 | 1.24 | 0.36 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Hostility Towards Women35 | 2.55 | 0.85 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Rape Supportive Beliefs36 | 2.15 | 0.63 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| High-Risk Alcohol Use37 | 3.40 | 1.57 | 0.20 | 7.00 |

| Sexual Compulsivity38 | 1.41 | 0.40 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Exposure to Pornography | 1.41 | 1.02 | 0.00 | 4.00 |

| Superficial Charm39 | 2.81 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Anger39 | 2.34 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Number of Sexual Partners | 2.68 | 4.43 | 0 | 38 |

Empathy was a significant moderator of six out of the ten risk factors for sexual violence perpetration tested (peer approval of forced sex, hostility towards women, rape supportive beliefs, alcohol use, sexual compulsivity, and number of sexual partners). Interactions between empathy and peer pressure for sex, pornography usage, superficial charm, and anger were non-significant, although the interaction between empathy and peer pressure for sex approached significance, p = .051. Table 3 illustrates the parameter estimates for each of the models.

Table 3.

Parameter estimates of empathy moderation models

| 95% CI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | β | SE | Lower | Upper | Wald χ2 | df | |

| Peer Pressure for Sex | Peer Pressure1 | 1.06*** | .08 | .90 | 1.23 | 160.10 | 1 |

| Empathy1 | −.24* | .11 | −.45 | −.03 | 5.18 | 1 | |

| Interaction | .23 | .12 | .00 | .46 | 3.81 | 1 | |

| Peer Approval of Forced Sex | Peer Approval1 | 3.12*** | .19 | 2.73 | 3.49 | 255.92 | 1 |

| Empathy1 | −.18 | .12 | −.40 | .05 | 2.30 | 1 | |

| Interaction | .72** | .25 | .23 | 1.21 | 8.19 | 1 | |

| Hostility Towards Women | Hostility1 | 1.00*** | .07 | .86 | 1.14 | 198.69 | 1 |

| Empathy1 | −.46*** | .10 | −.66 | −.25 | 19.27 | 1 | |

| Interaction | .29** | .11 | .51 | .51 | 7.03 | 1 | |

| Rape Supportive Beliefs | Rape Beliefs1 | .73*** | .10 | .54 | .92 | 55.82 | 1 |

| Empathy1 | −.32** | .10 | −.52 | −.13 | 10.74 | 1 | |

| Interaction | .48** | .16 | .18 | .79 | 9.44 | 1 | |

| High-Risk Alcohol Use | Alcohol Use1 | .45*** | .04 | .36 | .54 | 103.55 | 1 |

| Empathy1 | −.92*** | .13 | −1.18 | −.67 | 50.85 | 1 | |

| Interaction | .69*** | .09 | .52 | .86 | 63.00 | 1 | |

| Sexual Compulsivity | Compulsivity1 | .67*** | .16 | .35 | .99 | 16.53 | 1 |

| Empathy1 | −.07 | .09 | −.25 | .11 | .65 | 1 | |

| Interaction | −2.03*** | .31 | −2.65 | −1.41 | 41.62 | 1 | |

| Exposure to Pornography | Pornography1 | .45*** | .07 | .32 | .58 | 45.15 | 1 |

| Empathy1 | −.19 | .10 | −.39 | .01 | 3.45 | 1 | |

| Interaction | .00 | .08 | −.16 | .16 | .00 | 1 | |

| Superficial Charm | Superficial Charm1 | .81*** | .06 | .69 | .93 | 175.35 | 1 |

| Empathy1 | −.09 | .11 | −.30 | .13 | .64 | 1 | |

| Interaction | −.10 | .10 | −.30 | .10 | .97 | 1 | |

| Anger | Anger1 | 1.40*** | .10 | 1.22 | 1.59 | 211.61 | 1 |

| Empathy1 | .04 | .11 | −.18 | .26 | .12 | 1 | |

| Interaction | .22 | .12 | −.02 | .45 | 3.25 | 1 | |

| Number of Sexual Partners | # of Partners1 | .17*** | .02 | .13 | .21 | 71.40 | 1 |

| Empathy1 | −.40*** | .09 | −.59 | −.22 | 18.49 | 1 | |

| Interaction | .16*** | .03 | .10 | .22 | 26.09 | 1 | |

Centered variable

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

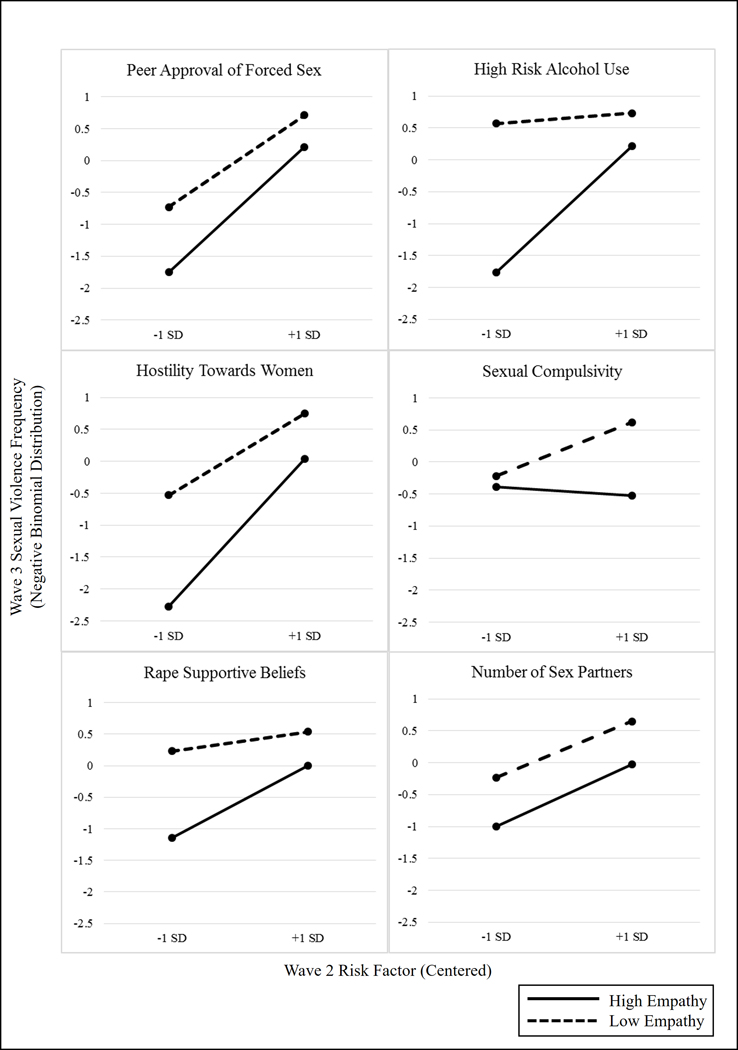

Graphs generated from post-hoc probing of significant models are illustrated in Figure 1. As demonstrated by the graphs, empathy was a moderator of risk factors of sexual violence perpetration such that participants with low scores for each risk factor and a high conditional level of empathy demonstrated the lowest sexual violence perpetration frequency. Empathy moderated rape supportive beliefs, alcohol use, and sexual compulsivity such that participants with high scores on the risk factor and a high conditional level of empathy demonstrated lower sexual violence perpetration frequency than participants with a low conditional level of empathy, regardless of their score on the risk factors. Finally, empathy moderated peer approval of forced sex, hostility towards women, and number of sexual partners such that individuals with high scores on the risk factor and a high conditional level of empathy demonstrated lower sexual violence perpetration frequency than individuals with high scores on the risk factor and a low conditional level of empathy, but higher sexual violence perpetration frequency than individuals with low scores on the risk factors and a low conditional level of empathy.

Figure 1.

Post-hoc Graphing of Significant Moderation Models

Comment

With empathy having demonstrated a significant moderating effect on six out of ten risk factors tested, the hypothesis that empathy would significantly moderate the effect of a majority of risk factors for sexual violence perpetration was mostly supported. Empathy was a significant moderator of peer approval of forced sex, and approached significance in moderating the risk from peer pressure for sex. These findings indicate that empathy among college males may help to offset external pressures and peer norms which promote sexual violence. Empathy was also a significant moderator of high risk alcohol use and number of sexual partners, suggesting that empathy may buffer the transition from a variety of risky behaviors to sexual violence perpetration. Finally, empathy was a significant moderator of sexual compulsivity, hostility towards women, and rape supportive beliefs, indicating that a college male’s perspective taking ability may override general attitudes and beliefs which are typically associated with increased sexual violence perpetration. Taken together, these findings indicate that empathy may play a significant role in moderating numerous risk factors for sexual violence perpetration among college males, ranging from external peer pressure, to participation in risky behavior, to attitudes and beliefs. Empathy should therefore be considered for inclusion in sexual violence prevention efforts and future research.

Empathy was not, however, a significant moderator of pornography usage, superficial charm, or anger. Pornography usage overall was relatively low among the sample, and in the moderation model it had one of the weakest main effects on sexual violence perpetration. The findings for superficial charm and anger, however, affirm that empathy is not a “silver bullet” which can moderate all risk factors of sexual violence perpetration. It is plausible that a college male with serious anger issues may be generally empathetic, but during episodes of severe anger or rage, empathy may not be important. It is also plausible that an individual with high levels of superficial charm may demonstrate traits of empathy such as understanding, care, and concern for others, but these qualities may in fact be superficial and not truly internalized. Finally, in the general sexual offender population, there is debate about whether empathy deficits are general in nature, or specifically limited to the individual victim,26 and it is plausible that some college males may exhibit empathy towards others in general, but may be limited in their ability to take the perspective of a victim of sexual violence. It is possible, therefore, that the general sense of empathy measured in the IRI Perspective Taking subscale relates more to some risk factors, such as peer approval of forced sex and hostility towards women, while individual victim-related empathy deficits are more pertinent to other risk factors.

The findings of the present study have important implications for practice and research. First, these findings add to the growing body of literature indicating that empathy is an important trait for healthy relationships and prosocial outcomes among college students. While concerns about an overall decrease in empathy among college students today may be well founded, there is mounting evidence that empathy is malleable during the college years and can be positively influenced both in and out of the classroom. For example, studies have found evidence that short-term simulations and class exercises had a positive impact on empathy among college students,24,25 and that long-term involvement in positive extracurricular activities are associated with increases in empathy over the course of a student’s college career.4 Taken together, the findings of the present study and previous findings about empathy malleability among college students suggest that empathy development could be an effective component of sexual violence prevention efforts on college campuses. Higher education administrators and educators may therefore wish to enhance efforts to foster empathy among students through both short-term exercises and promotion of long-term involvement in positive activities.

Second, the rate of self-reported sexual violence perpetration among college males in the present study (16.1% of participants reporting they had perpetrated at least one act of sexual violence during their junior year of college) adds to the body of evidence suggesting that colleges and universities must do more to prevent sexual violence beyond solely responding to sexual violence accusations against students as required by law under Title IX. Both the CDC’s recommendations on preventing sexual violence on college campuses41 and the American College Health Association’s (ACHA) standards of practice for prevention and health promotion42 state that prevention efforts on college campuses should be evidence-based. The significant interaction between empathy and numerous risk factors of sexual violence perpetration found in this study provides evidence that empathy development should be a central component of sexual violence prevention and intervention programs on college campuses, just as it is for many rape prevention and offender programs in non-college populations.26,43 These programs should include multiple sessions over the course of student’s tenure on campus, be gender specific, and address both the theory and skills needed to reduce sexual violence.41 Empathy development could also be incorporated into national efforts such as the “It’s On Us” campaign, which was launched in 2014 and encourages campus community members to actively engage in preventing sexual violence.44

Finally, given the limited amount of previous research on the relationship between empathy and sexual violence perpetration among college students, additional research to better understand this relationship is needed. Research with a nationally representative sample will be essential in generalizing findings about the role of empathy as a moderator of sexual violence perpetration risk factors. Additionally, longitudinal research testing the effectiveness of empathy-driven sexual violence prevention programs in reducing sexual violence perpetration across the college years will be essential in the development and validation of continually improved prevention efforts.

Limitations

The strengths of this study should be viewed in light of three important limitations. First, the inclusion of only one of the four Interpersonal Reactivity Index subscales limited the ability to examine the relationship between sexual violence perpetration and all dimensions of empathy. Inclusion of the full IRI measure in future research could help to better understand which dimensions of empathy beyond perspective taking play a significant role in moderating risk factors for sexual violence. Second, the lack of racial and ethnic diversity in the present study prevented any sub-group analyses and limits the ability to generalize findings on the relationship between empathy and sexual violence to all American college students. Inclusion of more diverse samples in future research could allow for a better understanding of the relationship between empathy and sexual violence perpetration among minority students. Third, although the survey was confidential and participants were informed of the study’s NIH Certificate of Confidentiality, because data for the study came from self-report surveys, there is a possibility that study participants may have provided what they perceived as socially desirable responses to some items.

Conclusions

In conclusion, sexual violence is a widespread, serious public health concern on college campuses across the United States. Empathy was found to be a significant moderator of a majority of risk factors for sexual violence among college males, such that college males with low levels of risk factors and high levels of empathy are the least likely to perpetrate sexual violence, and students with high levels of risk factors and high empathy demonstrate perpetration rates more comparable to students with low levels of risk factors. These findings validate empathy as an important component of healthy relationships and positive outcomes among college students, and support the inclusion of empathy development components in sexual violence prevention and intervention programs on college campuses. Additional research including diverse samples and comprehensive measures of empathy to test the effectiveness of such programs will be essential to the efforts of higher education administrators and educators in preventing sexual violence on college campuses.

References

- 1.Conley AH, Overstreet CM, Hawn SE, Kendler KS, Dick DM, Amstadter AB. Prevalence and predictors of sexual assault among a college sample. J Am Coll Health. 2017;65:41–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis MH, Mitchell KV, Hall JA, Lothert J, Snapp T, Meyer M. Empathy, expectations, and situational preferences: personality influences on the decision to participate in volunteer helping behaviors. J Pers. 1999;67:469–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smits I, Doumen S, Luyckx K, Duriez B, Goossens L. Identity styles and interpersonal behavior in emerging adulthood: the intervening role of empathy. Social Development. 2011;20:664–684. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hudson-Flege MD, Thompson MP. Empathy and extracurricular involvement in emerging adulthood: Findings from a longitudinal study of undergraduate college males. Journal of College Student Development. 2017;58:674–684 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varker T, Devilly GJ, Ward T, Beech AR. Empathy and adolescent sexual offenders: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008;13:251–260. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malamuth NM, Linz D, Heavey CL, Barnes G, Acker M. Using the confluence model of sexual aggression to predict men’s conflict with women: a 10-year follow-up study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:353–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control. Sexual violence: Definitions. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/sexualviolence/definitions.html. Accessed November 14, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson MP, Kingree JB. Sexual victimization, negative cognitions, and adjustment in college women. American Journal Health Behavior. 2010;34:55–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krebs PC, Lindquist HC, Warner DT, Fisher SB, Martin LA. The campus sexual assault (CSA) study: Final report. Available at http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/221153.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humphrey JA, White JW. Women’s vulnerability to sexual assault from adolescence to young adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27:419–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zinzow MH, Thompson M. Factors associated with use of verbally coercive, incapacitated, and forcible sexual assault tactics in a longitudinal study of college men. Aggressive Behavior. 2015;41:34–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swartout KM. The company they keep: How men’s social networks influence their sexually aggressive attitudes and behaviors. Psychology of Violence. 2013;2:309–312. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zinzow MH, Thompson M. A longitudinal study of risk factors for repeated sexual coercion and assault in US college men. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;44:213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis KC, Norris J, George WH, Martell J, Heiman JR. Men’s likelihood of sexual aggression: The influence of alcohol, sexual arousal, and violent pornography. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32:581–589. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson MP, Swartout KM, Koss MP. Trajectories and predictors of sexually aggressive behaviors during emerging adulthood. Psychology of Violence. 2013;3:247–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Decety J (Ed). Empathy: From bench to bedside. Cambridge: The MIT Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aggarwal P, Castleberry SB, Ridnour R, Shepherd CD. Salesperson empathy and listening: Impact on relationship outcomes. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice. 2005;13:16–31. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newton BW, Barber L, Clardy J, Cleveland E, O’Sullivan P. Is there hardening of the heart during medical school? Acad Med. 2008;83:244–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jolliffe D, Farrington DP. Empathy and offending: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;9:441–476. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiehe VR. Empathy and narcissism in a sample of child abuse perpetrators and a comparison sample of foster parents. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:541–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbey A, Jacques-Tiura AJ, LeBreton JM. Risk factors for sexual aggression in young men: An expansion of the confluence model. Aggressive Behavior. 2011;37:450–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konrath SH, O’Brien EH, Hsing C. Changes in dispositional empathy in American college students over time: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2011;15:180–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kazanowsk MK, Bennett LA. Engendering empathy in baccalaureate nursing students. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 2013;6:456–464. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Latshaw BA. Examining the impact of a domestic violence simulation on the development of empathy in sociology classes. Teaching Sociology. 2015;43:277–289. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Regehr C, Glancy G. Empathy and its influence on sexual misconduct. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2001;2:142–154. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Brunt B, Murphy A, O’toole ME. The dirty dozen: Twelve risk factors for sexual violence on college campuses (DD-12). Violence and Gender. 2015;2:145–160. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wheeler JG, George WH, Dahl BJ. Sexually aggressive college males: Empathy as a moderator in the “confluence model” of sexual aggression. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;33:759–775. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanin EJ. Date rapists: Differential sexual socialization and relative deprivation. Arch Sex Behav. 1985;14:219–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abbey A, McAuslan P. A longitudinal examination of male college students’ perpetration of sexual assault. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:747–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koss MP, Gaines JA. The prediction of sexual aggression by alcohol use, athletic participation, and fraternity affiliation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1993;8:94–108. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lonsway KA, Fitzgerald LF. Attitudinal antecedents of rape myth acceptance: A theoretical and empirical reexamination. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;68:704–711. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dawson DA, Room R. Towards agreement on ways to measure and report drinking patterns and alcohol-related problems in adult general population surveys: The Skarpo Conference overview. J Subst Abuse. 2000;12:1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalichman SC, Rompa D. The Sexual Compulsivity Scale: Further development and use with HIV-positive persons . J Pers Assess. 2001;76:379–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knight RA, Prentky RA, Cerce DD. The development, reliability, and validity of an inventory for the multidimensional assessment of sex and aggression. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 1994;21:72–94. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis MH Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;44:113–126. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S, Norris J, Testa M,... White J. Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31:357–370. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cole DA, & Maxwell SE (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;11:558–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swartout KM, Thompson MP, Koss MP, Su N. What is the best way to analyze less frequent forms of violence? The case of sexual aggression. Psychology of Violence. 2015;5:305–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preventing sexual violence on college campuses: Lessons from research and practice. CDC website; https://endingviolence.uiowa.edu/assets/CDC-Preventing-Sexual-Violence-on-College-Campuses-Lessons-from-Research-and-Practice.pdf. Updated June 18, 2014. Accessed September 5, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 42.ACHA guidelines: Standards of practice for health promotion in higher education (3rd ed.). American College Health Association Website; https://www.acha.org/documents/resources/guidelines/ACHA_Standards_of_Practice_for_Health_Promotion_in_Higher_Education_May2012.pdf. Uploaded May, 2012. Accessed September 5, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schewe PA. Guidelines for developing rape prevention and risk reduction interventions. In Schewe PA(Ed), Preventing violence in relationships: Interventions across the life span (107–136). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 44.President Obama launches the “It’s On Us” campaign to end sexual assault on campus. White House website; https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2014/09/19/president-obama-launches-its-us-campaign-end-sexual-assault-campus. Updated September 19, 2014. Accessed September 5, 2017. [Google Scholar]