Abstract

目的

鉴于脓毒症的高发病率和高病死率,早期识别高风险患者并及时干预至关重要,而现有死亡风险预测模型在操作、适用性和预测长期预后等方面均存在不足。本研究旨在探讨脓毒症患者死亡的危险因素,构建近期和远期死亡风险预测模型。

方法

从美国重症监护医学信息数据库IV(Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV,MIMIC-IV)中选取符合脓毒症3.0诊断标准的人群,按7꞉3的比例随机分为建模组和验证组,分析患者的基线资料。采用单因素Cox回归分析和全子集回归确定脓毒症患者死亡的危险因素并筛选出构建预测模型的变量。分别用时间依赖性曲线下面积(area under the curve,AUC)、校准曲线和决策曲线评估模型的区分度、校准度和临床实用性。

结果

共纳入14 240例脓毒症患者,28 d和1年病死率分别为21.45%(3 054例)和36.50%(5 198例)。高龄、女性、高感染相关器官衰竭评分(sepsis-related organ failure assessment,SOFA)、高简明急性生理学评分(simplified acute physiology score II,SAPS II)、心率快、呼吸频率快、脓毒症休克、充血性心力衰竭、慢性阻塞性肺疾病、肝脏疾病、肾脏疾病、糖尿病、恶性肿瘤、高白细胞计数(white blood cell count,WBC)、长凝血酶原时间(prothrombin time,PT)、高血肌酐(serum creatinine,SCr)水平均为脓毒症死亡的危险因素(均P<0.05)。由PT、呼吸频率、体温、合并恶性肿瘤、合并肝脏疾病、脓毒症休克、SAPS II及年龄8个变量构建的模型,其28 d和1年生存的AUC分别为0.717(95% CI 0.710~0.724)和0.716(95% CI 0.707~0.725)。校准曲线和决策曲线表明该模型具有良好的校准度及较好的临床应用价值。

结论

基于MIMIC-IV建立的脓毒症患者近期和远期死亡风险预测模型有较好的识别能力,对患者预后风险评估及干预治疗具有一定的临床参考意义。

Keywords: 脓毒症, 近期和远期死亡, 美国重症监护医学信息数据库IV, 预后因素, 预测模型

Abstract

Objective

Given the high incidence and mortality rate of sepsis, early identification of high-risk patients and timely intervention are crucial. However, existing mortality risk prediction models still have shortcomings in terms of operation, applicability, and evaluation on long-term prognosis. This study aims to investigate the risk factors for death in patients with sepsis, and to construct the prediction model of short-term and long-term mortality risk.

Methods

Patients meeting sepsis 3.0 diagnostic criteria were selected from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV (MIMIC-IV) database and randomly divided into a modeling group and a validation group at a ratio of 7꞉3. Baseline data of patients were analyzed. Univariate Cox regression analysis and full subset regression were used to determine the risk factors of death in patients with sepsis and to screen out the variables to construct the prediction model. The time-dependent area under the curve (AUC), calibration curve, and decision curve were used to evaluate the differentiation, calibration, and clinical practicability of the model.

Results

A total of 14 240 patients with sepsis were included in our study. The 28-day and 1-year mortality were 21.45% (3 054 cases) and 36.50% (5 198 cases), respectively. Advanced age, female, high sepsis-related organ failure assessment (SOFA) score, high simplified acute physiology score II (SAPS II), rapid heart rate, rapid respiratory rate, septic shock, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, liver disease, kidney disease, diabetes, malignant tumor, high white blood cell count (WBC), long prothrombin time (PT), and high serum creatinine (SCr) levels were all risk factors for sepsis death (all P<0.05). Eight variables, including PT, respiratory rate, body temperature, malignant tumor, liver disease, septic shock, SAPS II, and age were used to construct the model. The AUCs for 28-day and 1-year survival were 0.717 (95% CI 0.710 to 0.724) and 0.716 (95% CI 0.707 to 0.725), respectively. The calibration curve and decision curve showed that the model had good calibration degree and clinical application value.

Conclusion

The short-term and long-term mortality risk prediction models of patients with sepsis based on the MIMIC-IV database have good recognition ability and certain clinical reference significance for prognostic risk assessment and intervention treatment of patients.

Keywords: sepsis, short-term and long-term deaths, Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV database, prognostic factors, predictive model

脓毒症是人体对感染反应失调引起的危及生命的器官功能障碍综合征[1]。由于脓毒症具有高发病率、高病死率以及高昂的医疗费用等特点,已成为全世界的重大公共卫生问题[2]。据统计,脓毒症相关的死亡人数占全球死亡人数的19.7%[3]。在中国,脓毒症在重症监护病房(intensive care unit,ICU)的发病率、ICU病死率和住院死亡率分别为20.6%、29.63%和32.13%[4]。脓毒症患者出院后,其并发症和后遗症还可能继续危害患者的健康,导致该部分患者的90 d病死率达35.5%,1年病死率更高[4]。因此,早期识别高死亡风险的脓毒症患者,尽早进行医疗干预对改善患者预后及降低病死率至关重要。但脓毒症病情复杂、症状多样,临床医师常常无法在病情早期作出可靠的诊断,导致许多脓毒症幸存者死于后期持续性、复发性感染,因此脓毒症患者远期存活率的预测对其疾病康复和生活质量具有深远影响。然而,现有脓毒症预后预测模型多聚焦于短期死亡风险,对患者长期存活率的预测和评估还不够充分[5]。鉴于死亡风险预测模型在脓毒症患者早期诊治及改善预后方面具有重要的辅助作用,且现有的预测模型在操作、适用性等方面存在一定的局限性,如特异性低、敏感性低、过度诊断、无法预测远期死亡风险等[6-8],本研究对美国重症监护医学信息数据库IV(Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV,MIMIC-IV)中符合脓毒症3.0诊断标准的脓毒症患者进行回顾性分析,利用数据库中患者的数据资料,构建28 d及1年死亡风险预测模型,旨在提高临床医师对脓毒症患者近期和远期死亡风险的预判能力,促进个体化治疗的持续改进和降低病死率。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 数据来源

本研究是基于MIMIC-IV开展的一项回顾性队列研究。MIMIC-IV是麻省理工学院计算生理学实验室发布的一个单中心重症监护数据集,该项目获麻省理工学院和贝斯以色列女执事医疗中心的机构审查委员会批准,数据库中包含的患者信息是匿名的,并获得了放弃知情同意的权利。MIMIC-IV v2.0包括2008至2019年入住ICU的382 278名患者的医疗信息。本课题组成员已通过“数据或标本研究”课程培训,并获得了MIMIC-IV数据库的使用授权(编号:40060500)。

1.2. 纳入和排除标准

纳入标准:1)符合脓毒症3.0诊断标准,脓毒症3.0诊断标准包括怀疑或有记录的感染以及感染相关器官衰竭评分(sepsis-related organ failure assessment,SOFA)急性升高≥2[9];2)年龄≥18岁。排除标准:1)同一患者有多次入住ICU记录,只纳入首次记录;2)ICU住院时间<48 h;3)怀孕或哺乳期患者;4)终末期心力衰竭或终末期肾脏疾病患者;5)入住ICU后才进展为脓毒症的患者。

1.3. 数据提取与管理

使用结构化查询语言(structured query language,SQL)和PostgreSQL工具(9.6版本)进行数据提取。提取的变量包括年龄、性别、种族、SOFA、简明急性生理评分II(simplified acute physiology score II,SAPS II)、格拉斯哥昏迷评分(Glasgow coma scale,GCS)、生命体征(平均动脉压、心率、体温、呼吸频率)、是否为脓毒症休克、临床合并症(充血性心力衰竭、慢性阻塞性肺疾病、肝脏疾病、肾脏疾病、糖尿病和恶性肿瘤)以及实验室指标[血红蛋白(hemoglobin,Hb)、白细胞计数(white blood cell,WBC)、凝血酶原时间(prothrombin,PT)、血肌酐(serum creatinine,SCr)]。对于多次检测的基线数据,本研究采用ICU入住后24 h内的生命体征的平均值和实验室指标的最差值。其中脓毒症定义为人体对感染反应失调引起的危及生命的器官功能障碍综合征,脓毒症休克是伴有循环和细胞/代谢功能障碍的脓毒症的一个子集,临床表现为在充分的液体复苏情况下,仍需使用血管加压药维持平均动脉压≥65 mmHg(1 mmHg=0.133 kPa)和乳酸>2 mmol/L(18 mg/dL)[9]。近期死亡定义为28 d死亡,远期死亡定义为1年死亡[10]。

1.4. 统计学处理

使用R(4.2.0版本)和EmpowerStats软件(4.1版本)进行统计学分析。正态分布变量以均数±标准差( ±s)表示,组间比较采用Student’s t检验;偏态分布变量以中位数(第1四分位数,第3四分位数)[M(P 25, P 75)]表示,组间比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验;分类变量以例数(%)表示,组间比较采用χ 2检验。变量的缺失值用均值或中位数插补。

将样本按7꞉3的比例随机分为建模组和验证组后,比较2组患者基线临床特征。采用单因素Cox回归分析影响患者总死亡的预后因素,计算风险比(hazard ratio,HR)及其95%可信区间(95% confidence interval,95% CI)。采用全子集回归法对单因素分析中有意义的变量(P<0.05)进一步筛选,用于构建列线图。采用时间依赖性曲线下面积(area under the curve,AUC)评价模型的区分判别能力。采用校准曲线和Hosmer-Lemeshow检验评估模型的一致度和准确性。采用决策曲线评估模型的临床实用价值。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结 果

2.1. 建模组及验证组患者的一般资料

根据纳入和排除标准,初步纳入MIMIC-Ⅳ中成年脓毒症患者35 010例,排除7 870例非首次入ICU患者,9 721例ICU住院时间<48 h患者,57例怀孕或处于哺乳期的患者,849例终末期心力衰竭或肾衰竭患者及2 273例入住ICU后进展为脓毒症患者,本研究最终纳入14 240例患者,其中建模组9 968例,验证组4 272例。本队列患者的28 d病死率为21.45%(3 054/14 240),1年病死率为36.50%(5 198/14 240),年龄为(66.79±16.27)岁,57.63%为男性,SOFA为3.00(2.00,4.25),SAPS II为41.94±13.97,GCS为14.13±2.39,平均动脉压为(76.25±9.81) mmHg,心率为(88.14±16.56) 次/min,体温为(36.93±0.63) ℃,呼吸频率为(19.99±4.13)次/min,脓毒症休克占19.98%,合并充血性心力衰竭占32.40%,合并慢性阻塞性肺疾病占28.12%,合并肝脏疾病占16.54%,合并肾脏疾病占19.48%,合并糖尿病占30.15%,合并恶性肿瘤占16.10%,Hb为(9.79±2.18) g/dL,WBC为[14.30(10.30,19.50)]×109/L,PT为15.10(13.30,18.30) s,SCr为1.20(0.80,1.80) mg/dL。上述变量在建模组和验证组之间差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05,表1)。

表1.

建模组和验证组中脓毒症患者的临床特征

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of sepsis patients in the modeling and validation cohorts

| 组别 | n | 年龄/岁 | 男性/[例(%)] | 种族/[例(%)] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 白种人 | 黑种人 | 黄种人 | 其他 | ||||

| 建模组 | 9 968 | 66.66±16.40 | 5 713(57.31) | 6 703(67.25) | 790(7.93) | 276(2.77) | 2 199(22.06) |

| 验证组 | 4 272 | 66.84±16.22 | 2 493(58.36) | 2 867(67.11) | 353(8.26) | 107(2.50) | 945(22.12) |

| t/t'/χ 2 | t=0.632 | χ 2=1.333 | χ 2=1.214 | ||||

| P | 0.527 | 0.248 | 0.750 | ||||

| 组别 | SOFA | SAPS II | GCS | 平均动脉压/mmHg | 心率/(次·min-1) | 体温/℃ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 建模组 | 3.00(2.00, 4.00) | 41.96±13.98 | 14.12±2.38 | 76.25±9.86 | 88.23±16.58 | 36.92±0.63 |

| 验证组 | 3.00(2.00, 5.00) | 41.90±13.95 | 14.14±2.40 | 76.27±9.72 | 87.94±16.54 | 36.94±0.62 |

| t/t'/χ 2 | t'=-1.644 | t=0.199 | t=-0.425 | t=-0.109 | t=0.978 | t=-1.876 |

| P | 0.100 | 0.842 | 0.671 | 0.913 | 0.328 | 0.061 |

| 组别 | 呼吸频率/(次·min-1) | 脓毒症休克/[例(%)] |

合并充血性 心力衰竭/ [例(%)] |

合并慢性阻塞性肺疾病/ [例(%)] |

合并肝脏疾病/[例(%)] | 合并肾脏疾病/[例(%)] | 合并糖尿病/[例(%)] | 合并恶性肿瘤/[例(%)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 建模组 | 19.99±4.14 | 1 971(19.77) | 3 252(32.62) | 4 614(32.40) | 1 658(16.63) | 1 915(19.21) | 3 043(30.53) | 1 614(16.19) |

| 验证组 | 20.00±4.11 | 874(20.46) | 1 362(31.88) | 1 155(27.04) | 698(16.34) | 859(20.11) | 1 250(29.26) | 679(15.89) |

| t/t'/χ 2 | t=-0.147 | χ 2=0.879 | χ 2=0.752 | χ 2=3.531 | χ 2=0.188 | χ 2=1.531 | χ 2=2.281 | χ 2=0.196 |

| P | 0.883 | 0.348 | 0.386 | 0.060 | 0.665 | 0.216 | 0.131 | 0.658 |

| 组别 | Hb/(g·dL-1) | WBC/(×109·L-1) | PT/s | SCr/(mg·dL-1) | 28 d死亡/[例(%)] | 1年死亡/[例(%)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 建模组 | 9.79±2.18 | 14.30(10.30, 19.40) | 15.10(13.30, 18.30) | 1.20(0.80, 1.80) | 2 169(21.76) | 3 643(36.55) |

| 验证组 | 9.78±2.19 | 14.10(10.20, 19.50) | 15.10(13.40, 18.20) | 1.20(0.90, 1.80) | 885(20.72) | 1 555(36.40) |

| t/t'/χ 2 | t=0.271 | t'=0.753 | t'=0.115 | t'=-0.383 | χ 2=1.932 | χ 2=0.028 |

| P | 0.786 | 0.452 | 0.908 | 0.702 | 0.165 | 0.867 |

1 mmHg=0.133 kPa。正态分布的数据采用均数±标准差表示,非正态分布的数据采用中位数(第1四分位数,第3四分位数)表示。SOFA:感染相关器官衰竭评分;SAPS Ⅱ:简明急性生理学评分Ⅱ;GCS:格拉斯哥昏迷评分;Hb:血红蛋白;WBC:白细胞计数;PT:凝血酶原时间;SCr:血肌酐。

2.2. Cox回归分析

在单变量模型中,高龄、女性、高SOFA、高SAPS II、心率快、呼吸频率快、脓毒症休克、合并充血性心力衰竭、合并慢性阻塞性肺疾病、合并肝脏疾病、合并肾脏疾病、合并糖尿病、合并恶性肿瘤均为脓毒症死亡的危险因素(均P<0.05)。高WBC、长PT、高SCr也是脓毒症死亡的危险因素(均P<0.05)。高GCS、平均动脉压、体温、Hb是脓毒症死亡的保护因素(均P<0.05,表2)。

表2.

影响脓毒症患者死亡的单因素Cox回归分析结果

Table 2 Univariate Cox regression analysis results for factors influencing mortality in sepsis patients

| 变量 | 单因素分析 | 变量 | 单因素分析 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | ||

| 年龄 | 1.026 | 1.024~1.028 | <0.001 | 呼吸频率 | 1.051 | 1.044~1.058 | <0.001 |

| 女性 | 1.096 | 1.033~1.162 | 0.002 | 脓毒症休克 | 1.869 | 1.749~1.998 | <0.001 |

| 种族(白种人为参照) | 充血性心力衰竭 | 1.427 | 1.344~1.516 | <0.001 | |||

| 黑种人 | 1.079 | 0.972~1.197 | 0.154 | 慢性阻塞性肺疾病 | 1.250 | 1.175~1.331 | <0.001 |

| 黄种人 | 1.105 | 0.930~1.314 | 0.257 | 肝脏疾病 | 1.454 | 1.352~1.564 | <0.001 |

| 其他 | 0.982 | 0.912~1.058 | 0.642 | 肾脏疾病 | 1.561 | 1.459~1.669 | <0.001 |

| SOFA | 1.060 | 1.046~1.076 | <0.001 | 糖尿病 | 1.101 | 1.035~1.172 | 0.002 |

| SAPS II | 1.033 | 1.032~1.035 | <0.001 | 恶性肿瘤 | 2.406 | 2.249~2.574 | <0.001 |

| GCS | 0.977 | 0.966~0.988 | <0.001 | Hb | 0.949 | 0.936~0.962 | <0.001 |

| 平均动脉压 | 0.987 | 0.983~0.990 | <0.001 | WBC | 1.003 | 1.001~1.005 | 0.003 |

| 心率 | 1.004 | 1.003~1.006 | <0.001 | PT | 1.011 | 1.010~1.013 | <0.001 |

| 体温 | 0.703 | 0.674~0.734 | <0.001 | SCr | 1.110 | 1.091~1.129 | <0.001 |

SOFA:感染相关器官衰竭评分;SAPS Ⅱ:简明急性生理学评分Ⅱ;GCS:格拉斯哥昏迷评分;Hb:血红蛋白;WBC:白细胞计数;PT:凝血酶原时间;SCr:血肌酐;HR:风险比;95% CI:95%可信区间。

2.3. 死亡风险预测模型的构建

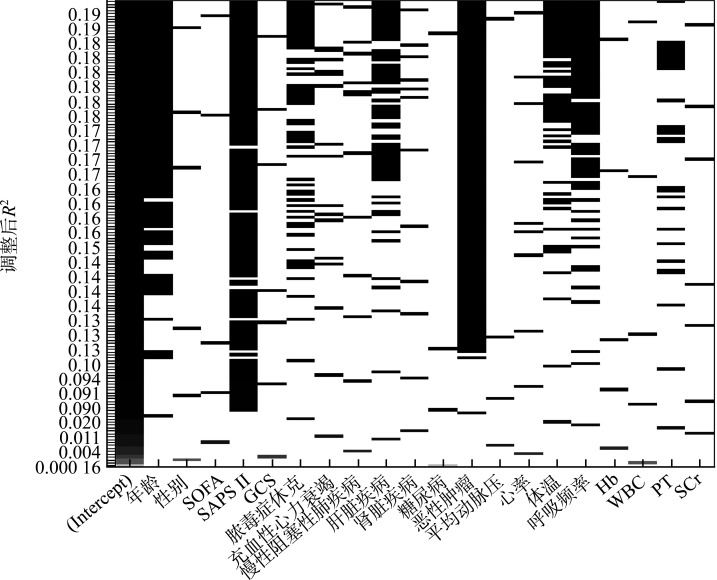

通过全子集回归对所有预测变量的可能组合进行模型拟合,根据最大调整后R 2值筛选出需要纳入模型的变量数目为8,分别为PT、呼吸频率、体温、合并恶性肿瘤、合并肝脏疾病、脓毒症休克、SAPS II及年龄(图1)。

图1.

全子集回归变量筛选图

Figure 1 Full subset regression variable selection plot

SOFA: Sepsis-related organ failure assessment; SAPS Ⅱ: Simplified acute physiology score II; GCS: Glasgow coma scale; Hb: Hemoglobin; WBC: White blood cell count; PT: Prothrombin time; SCr: Serum creatinine.

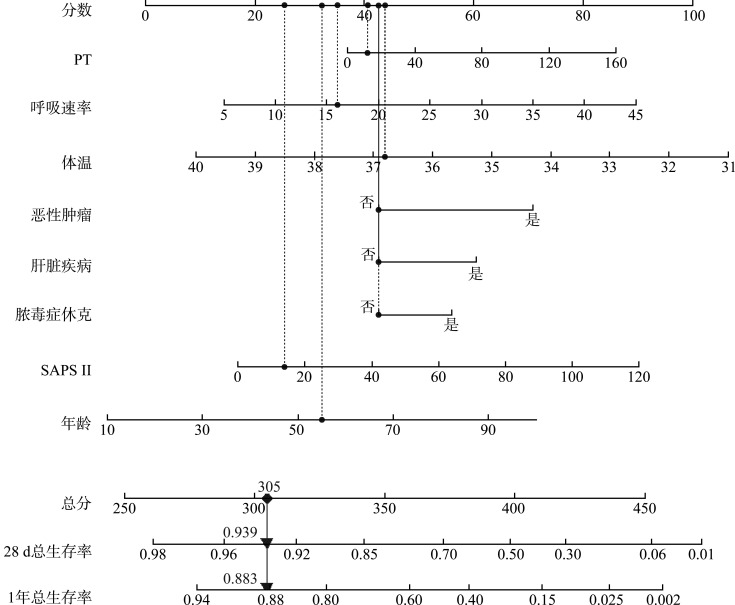

将上述全子集回归筛选出的8个预测因子纳入模型中,基于Cox回归构建脓毒症患者28 d及1年死亡风险预测模型,并绘制列线图(图2)。每个变量对应1个分值,如某患者PT为12 s(41分)、呼吸频率为 16次/min(34分)、体温为36.8 ℃(44分)、未合并恶性肿瘤(43分)、未合并肝脏疾病(43分)、无脓毒症休克(43分)、SAPS II为14(25分)及年龄为55岁(32分)。这8个预测因子对应的总分为305。305分对应的28 d生存率为0.939,1年生存率为0.883,表示该脓毒症患者28 d及1年死亡的概率分别为0.061和0.117。

图2.

预测脓毒症患者28 d及1年总生存率的列线图

Figure 2 Nomogram of predicted 28-day and 1-year overall survival rates in sepsis patients

PT: Prothrombin time; SAPS Ⅱ: Simplified acute physiology score II.

2.4. 模型评价与验证

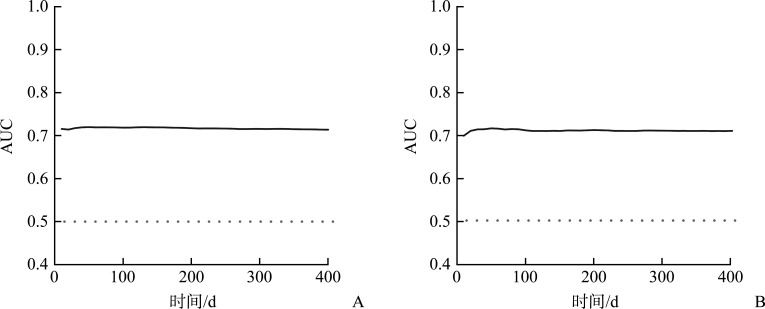

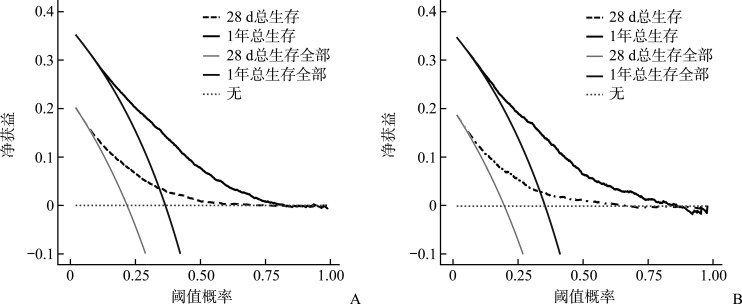

本研究所建立的死亡风险预测模型具有一定的区分能力,其中建模组预测28 d生存的AUC为0.717(95% CI 0.710~0.724),1年生存的AUC为0.716(95% CI 0.707~0.725)(图3A);验证组预测28 d生存的AUC为0.714(95% CI 0.705~0.723),1年生存的AUC为0.711(95% CI 0.701~0.721)(图3B)。

图3.

脓毒症患者死亡风险预测模型的时间依赖性AUC

Figure 3 Time-dependent AUC for the mortality risk prediction model in sepsis patients

A: Time-dependent AUC of mortality risk prediction model in the modeling group; B: Time-dependent AUC of mortality risk prediction model in the validation group. AUC: Area under the curve.

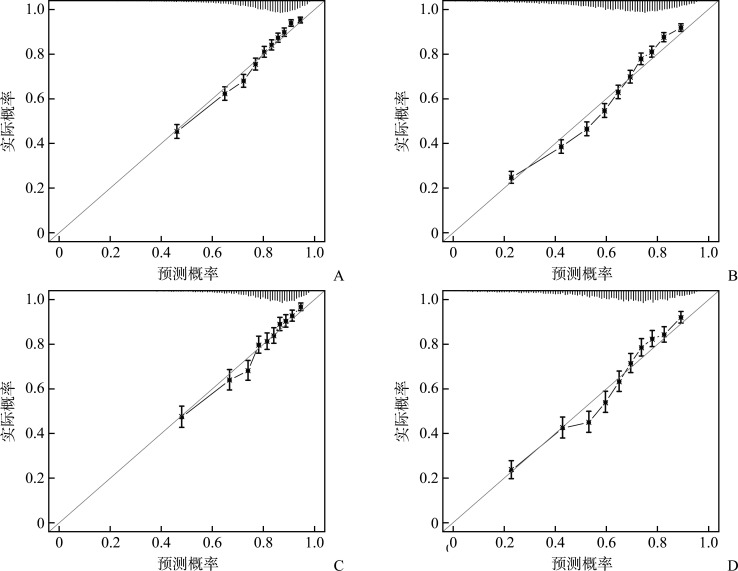

校准曲线显示建模组28 d死亡风险(图4A)、建模组1年死亡风险(图4B)、验证组28 d死亡风险(图4C)及验证组1年死亡风险(图4D)的预测概率均与实际概率基本一致。Hosmer-Lemeshow检验结果显示28 d死亡模型(χ 2=15.908,P=0.115)和1年死亡模型 (χ 2=15.450,P=0.051)的预测概率与实际概率之间差异无统计学意义,表明该模型具有良好的校准度。

图4.

脓毒症患者28 d及1年死亡风险预测模型的校准曲线

Figure 4 Calibration curves for the 28-day and 1-year mortality risk prediction models in sepsis patients

A: Calibration curve of the 28-day mortality risk prediction model in the modeling group; B: Calibration curve of the 1-year mortality risk prediction model in the modeling group; C: Calibration curve of the 28-day mortality risk prediction model in the validation group; D: Calibration curve of the 1-year mortality risk prediction model in the validation group.

决策曲线显示:当建模组(图5A)及验证组(图5B)的死亡风险阈值概率为0~0.7时,该模型预测脓毒症患者28 d死亡风险的标准化净收益是增加的;当建模组(图5A)及验证组(图5B)的死亡风险阈值概率为0~0.8时,该模型预测脓毒症患者1年死亡风险的标准化净收益是增加的。该预测模型预测患者1年死亡的收益大于28 d死亡预测,有较好的临床应用价值。

图5.

脓毒症患者28 d及1年死亡风险预测模型的决策曲线

Figure 5 Decision curves for the 28-day and 1-year mortality risk prediction models in sepsis patients

A: Decision curves of the mortality risk prediction model in the modeling group; B: Decision curves of the mortality risk prediction model in the validation group.

3. 讨 论

脓毒症患者的近期病死率及远期病死率均较高。筛选出影响其死亡的危险因素及保护因素,并对该部分患者进行积极的治疗及个性化的护理,可以减轻患者的病痛及经济负担,改善预后及降低病死率。本研究结果显示高龄、女性、高SOFA、高SAPS II、心率快、呼吸频率快、脓毒症休克、合并充血性心力衰竭、合并慢性阻塞性肺疾病、合并肝脏疾病、合并肾脏疾病、合并糖尿病、合并恶性肿瘤均为脓毒症死亡的危险因素。高WBC、长PT、高SCr也是脓毒症死亡的危险因素。高GCS、平均动脉压、体温、Hb是脓毒症死亡的保护因素。通过全子集回归对这些危险因素和保护因素进行模型拟合,筛选出PT、呼吸频率、体温、合并恶性肿瘤、合并肝脏疾病、脓毒症休克、SAPS II及年龄8个变量为最优变量组合,构建了脓毒症患者28 d及1年死亡风险预测模型。

PT延长是反映凝血功能障碍的指标。当脓毒症患者出现凝血功能紊乱时,可能会导致微血栓的形成和组织缺血缺氧,进一步加重器官功能障碍而增加死亡风险[11]。体温与脓毒症患者死亡的关系一直存在争议。一些研究[12-13]认为体温增高会增加患者的死亡风险,因而推荐使用低温治疗来避免高温导致的血管扩张、水分和电解质流失以及心动过速。而Drewry等[14]的研究表示高温有利于机体对炎症反应的应答,不支持对脓毒症患者实施体温控制治疗。本研究结果与Drewry等[14]及郑晓东等[15]的结果一致,高体温是脓毒症患者死亡的保护因素,高体温与28 d及1年病死率降低有关。ICU脓毒症患者本身的病情凶险且发展迅速,如果患者年龄大又合并了一些基础疾病,机体功能下降、免疫力低,那么会导致更高的病死率[16-18]。本研究结果与上述研究结果一致,即高龄、合并恶性肿瘤和合并肝脏疾病是脓毒症患者死亡的危险因素。当脓毒症患者发展为脓毒症休克时,其病死率增加,为35%~40%[19]。SOFA及SAPS II等疾病严重程度评分通常用于判断ICU内重症患者的病情严重程度,并且这些评分指标广泛用于预测脓毒症患者的预后,在预测患者病死率方面有较好的区分度,SAPS II在这些评分中有较好的临床价值[20]。目前,现有证据无法就性别与脓毒症相关病死率之间的关联得出明确的结论。一些研究[21-22]报告脓毒症男性患者的病死率较高,而其他研究[23-24]则报告脓毒症女性患者的病死率较高。这些矛盾结果的背后可能存在多种原因,如合并症在男女患者间分布的差异、脓毒症的严重程度、器官支持率、决定中止/撤销治疗的比例、感染源的性别差异、研究方法的不同等混杂因素[25-28],与性别相关的许多重要生理问题仍有待研究。本研究的样本仅来源于单中心数据库,回顾性研究设计也具有一定的局限性,相关结论仍需要更多研究进行验证。

对于脓毒症患者死亡风险预测模型的研究,已有一些报道,如Ford等[29]构建了严重脓毒症患者的风险预测模型,该模型有较好的区分度和准确度,但患者的纳入并非基于脓毒症3.0标准。Zhang等[5]基于MIMIC-III构建了预测严重脓毒症患者院内死亡风险的预测模型,该模型有一定的推广价值,但缺少预测远期死亡风险的功能。

本研究基于脓毒症3.0诊断标准纳入MIMIC-IV中14 240例脓毒症患者,对其基线资料、生理指标和实验室指标进行分析,构建了脓毒症患者28 d及1年死亡风险的预测模型,该模型能够较为准确地预测脓毒症患者近期和远期死亡的风险,具有较好的区分度和一致性,也具有一定的临床应用价值。

基金资助

湖南省自然科学基金(2022JJ40840);中南大学湘雅医院青年基金(2021Q13)。This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2022JJ40840) and the Youth Fund of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (2021Q13), China.

利益冲突声明

作者声称无任何利益冲突。

作者贡献

严丹阳 论文设计、撰写与修改,数据分析;谢茜、付翔杰、徐道妙 数据采集;李宁 论文指导;姚润 论文设计、撰写、指导及修改。所有作者阅读并同意最终的文本。

Footnotes

http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2024.230390

原文网址

http://xbyxb.csu.edu.cn/xbwk/fileup/PDF/202402256.pdf

参考文献

- 1. Seymour CW, Liu VX, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis: for the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3)[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8): 762-774. 10.1001/jama.2016.0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stoller J, Halpin L, Weis M, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis: 2008—2012[J]. J Crit Care, 2016, 31(1): 58-62. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990—2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study[J]. Lancet, 2020, 395(10219): 200-211. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32989-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xie JF, Wang HL, Kang Y, et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in Chinese ICUs: a national cross-sectional survey[J/OL]. Crit Care Med, 2020, 48(3): e209-e218[2023-07-11]. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang ZH, Hong YC. Development of a novel score for the prediction of hospital mortality in patients with severe sepsis: the use of electronic healthcare records with LASSO regression[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8(30): 49637-49645. 10.18632/oncotarget.17870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Du B, An YZ, Kang Y, et al. Characteristics of critically ill patients in ICUs in mainland China [J]. Crit Care Med, 2013, 41(1): 84-92. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31826a4082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Serafim R, Gomes JA, Salluh J, et al. A comparison of the quick-SOFA and systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria for the diagnosis of sepsis and prediction of mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Chest, 2018, 153(3): 646-655. 10.1016/j.chest.2017.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Song JU, Sin CK, Park HK, et al. Performance of the quick Sequential (sepsis-related) Organ Failure Assessment score as a prognostic tool in infected patients outside the intensive care unit: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Crit Care, 2018, 22(1): 28. 10.1186/s13054-018-1952-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3)[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8): 801-810. 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. 骆艳妮, 张静静, 李若寒, 等. ICU患者昼夜心率变异对近期和远期病死率的影响: 基于MIMIC-II数据库的回顾性队列研究[J]. 中华危重病急救医学, 2019, 31(9): 1128-1132. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-4352.2019.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; LUO Yanni, ZHANG Jingjing, LI Ruohan, et al. Effects of circadian heart rate variation on short-term and long-term mortality in intensive care unit patients: a retrospective cohort study based on MIMIC-Ⅱ database[J]. Chinese Critical Care Medicine, 2019, 31(9): 1128-1132. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-4352.2019.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. 胥志跃. 脓毒症凝血系统功能障碍与预后关系的研究[J]. 医学临床研究, 2007(6): 1030-1031. 10.3969/j.issn.1671-7171.2007.06.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; XU Zhiyue. Study on the relationship between coagulation system dysfunction and prognosis in sepsis[J]. Journal of Clinical Research, 2007(6): 1030-1031. 10.3969/j.issn.1671-7171.2007.06.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rumbus Z, Matics R, Hegyi P, et al. Fever is associated with reduced, hypothermia with increased mortality in septic patients: a meta-analysis of clinical trials[J/OL]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(1): e0170152[2023-07-12]. 10.1371/journal.pone.0170152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Niven DJ, Laupland KB, Tabah A, et al. Diagnosis and management of temperature abnormality in ICUs: a EUROBACT investigators’ survey[J]. Crit Care, 2013, 17(6): R289. 10.1186/cc13153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drewry AM, Ablordeppey EA, Murray ET, et al. Antipyretic therapy in critically ill septic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Crit Care Med, 2017, 45(5): 806-813. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. 郑晓东, 张凯. 脓毒症患者住院死亡的危险因素及预测模型的可视化呈现[J]. 临床医学研究与实践, 2021, 6(16): 37-40. 10.19347/j.cnki.2096-1413.202116009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; ZHENG Xiaodong, ZHANG Kai. Visualization of risk factors and predictive models for hospitalized death in patients with sepsis[J]. Clinical Research and Practice, 2021, 6(16): 37-40. 10.19347/j.cnki.2096-1413.202116009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. 魏锋, 洪志敏, 董海涛, 等. ICU重度脓毒症的流行病学特点及预后影响因素的分析[J]. 中华医院感染学杂志, 2018, 28(10): 1469-1471. 10.11816/cn.ni.2018-180865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; WEI Feng, HONG Zhimin, DONG Haitao, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of severe sepsis in ICU and influencing factors for prognosis[J]. Chinese Journal of Nosocomiology, 2018, 28(10): 1469-1471. 10.11816/cn.ni.2018-180865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. 刘冲, 林瑾, 李昂, 等. ICU严重脓毒症患者死亡原因分析[J]. 山东医药, 2014, 54(24): 78-80. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-266X.2014.24.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; LIU Chong, LIN Jin, LI Ang, et al. Analysis of the causes of death in ICU patients with severe sepsis[J]. Shandong Medical Journal, 2014, 54(24): 78-80. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-266X.2014.24.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. 费玉娟, 孟建标. ICU老年脓毒症患者的临床特点及预后影响因素分析[J]. 中国现代医生, 2018, 56(31): 69-72. [Google Scholar]; FEI Yujuan, MENG Jianbiao. Analysis on the clinical characteristics and influencing factors of prognosis in the elderly patients with sepsis in ICU[J]. China Modern Doctor, 2018, 56(31): 69-72. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vincent JL, Jones G, David S, et al. Frequency and mortality of septic shock in Europe and North America: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Crit Care, 2019, 23(1): 196. 10.1186/s13054-019-2478-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Poole D, Rossi C, Latronico N, et al. Comparison between SAPS II and SAPS 3 in predicting hospital mortality in a cohort of 103 Italian ICUs. Is new always better?[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2012, 38(8): 1280-1288. 10.1007/s00134-012-2578-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xu JH, Tong L, Yao JY, et al. Association of sex with clinical outcome in critically ill sepsis patients: a retrospective analysis of the large clinical database MIMIC-III[J]. Shock, 2019, 52(2): 146-151. 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Adrie C, Azoulay E, Francais A, et al. Influence of gender on the outcome of severe sepsis: a reappraisal[J]. Chest, 2007, 132(6): 1786-1793. 10.1378/chest.07-0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nachtigall I, Tafelski S, Rothbart A, et al. Gender-related outcome difference is related to course of sepsis on mixed ICUs: a prospective, observational clinical study[J]. Crit Care, 2011, 15(3): R151. 10.1186/cc10277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sunden-Cullberg J, Nilsson A, Inghammar M. Sex-based differences in ED management of critically ill patients with sepsis: a nationwide cohort study[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2020, 46(4): 727-736. 10.1007/s00134-019-05910-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mauvais-Jarvis F, Bairey Merz N, Barnes PJ, et al. Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine[J]. Lancet, 2020, 396(10250): 565-582. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31561-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Paoli CJ, Reynolds MA, Sinha M, et al. Epidemiology and costs of sepsis in the United States—an analysis based on timing of diagnosis and severity level[J]. Crit Care Med, 2018, 46(12): 1889-1897. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Benfield T, Espersen F, Frimodt-Møller N, et al. Increasing incidence but decreasing in-hospital mortality of adult Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia between 1981 and 2000[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2007, 13(3): 257-263. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Laupland KB, Gregson DB, Church DL, et al. Incidence, risk factors and outcomes of Escherichia coli bloodstream infections in a large Canadian Region[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2008, 14(11): 1041-1047. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ford DW, Goodwin AJ, Simpson AN, et al. A severe sepsis mortality prediction model and score for use with administrative data[J]. Crit Care Med, 2016, 44(2): 319-327. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]