Abstract

This chapter describes the isolation and culture of neonatal mouse calvarial osteoblasts. This primary cell population is obtained by sequential enzymatic digestion of the calvarial bone matrix and is capable of differentiating in vitro into mature osteoblasts that deposit a collagen extracellular matrix and form mineralized bone nodules. Maturation of the cultures can be monitored by gene expression analyses and staining for the presence of alkaline phosphatase or matrix mineralization. This culture system, therefore, provides a powerful model to test how various experimental conditions, such as the manipulation of gene expression, may affect osteoblast maturation and/or function.

Keywords: Mouse, Calvaria, Osteoblast, Bone, Maturation, Mineralization

1. Introduction

Osteoblasts are the cells responsible for new bone formation during skeletal development, remodeling, and repair. They arise from multipotent mesenchymal progenitor cells through a process governed by both systemic and local growth factors. These factors modulate signaling pathways that lead to the activation of transcription factors critical for the expression of genes required for differentiation into and throughout the osteoblast lineage (for review [1–3]). Once committed to the lineage, the osteoblast phenotype is defined by the sequential expression of genes involved in proliferation, extracellular matrix (ECM) maturation, and mineralization [4–6]. During the proliferative stage, immature osteoblasts begin to express and secrete type I collagen. This is the major protein product of the osteoblast and the primary building block of the organic bone matrix. As cells mature and exit the cell cycle, however, they begin to express other ECM molecules including various glycoproteins, proteoglycans, and γ-carboxylated (or gla) proteins that are involved in the subsequent maturation and mineralization of the matrix. Several of these proteins are considered established “markers” of osteoblast maturation and are thought to regulate the ordered deposition and turnover of hydroxyapatite crystals within the organic bone matrix. Alkaline phosphatase (encoded by mouse Alpl), for example, is the most abundant glycoprotein in the ECM and is expressed by osteoblasts immediately upon exit from the cell cycle [6]. It is a positive regulator of bone mineral deposition, and its deficiency leads to hypophosphatasia in both humans and mice [7]. Other maturation “markers” include bone sialoprotein (encoded by mouse Ibsp), osteopontin (encoded by mouse Spp1), and osteocalcin (encoded by mouse Bglap). Bone sialoprotein and osteopontin are both phosphoproteins and members of the small, integrin-binding ligand, N-linked glycoprotein (SIBLING) family of proteins. Osteopontin is a potent inhibitor of bone matrix mineralization, while bone sialoprotein is a confirmed nucleator of hydroxyapatite crystals making it a positive regulator of mineralization [8–10]. Osteocalcin, a gla protein, is secreted solely by mature osteoblasts and, when carboxylated, binds strongly to hydroxyapatite crystals in the mineralized matrix [11]. Rather than playing a direct role in matrix mineralization, however, osteocalcin has recently been shown to be released from the bone matrix during resorption and to play an active endocrine role in regulation of glucose metabolism [12, 13]. Mature osteoblasts, therefore, regulate not only bone formation but also other physiological processes by secreting proteins with endocrine properties.

To date, much progress has been made in defining the molecular and cellular properties of the osteoblast phenotype through characterization of primary calvarial-derived osteoblast cultures from chick, rat, and mouse. Primary bone cells were first successfully isolated from the frontal and parietal bones of fetal and neonatal rat calvaria by Peck et al. in 1964 [14]. Viable, alkaline phosphatase-expressing cells were released from the bone matrix by collagenase digestion; however, culture conditions did not allow for the formation of bone nodules and did not prevent the overgrowth of fibroblasts. Wong and Cohn later modified the procedure to isolate sequential populations of cells from mouse calvaria via short successive incubations with collagenase [15]. This method allows for the enrichment of cells with an osteoblastic phenotype from the third, fourth, and fifth populations [16, 17]. These cells produce a type I collagen matrix, express alkaline phosphatase, and generate mineralized bone nodules containing hydroxyapatite crystals when cultured with ascorbic acid and β-glycerophosphate [18–20]. This is still the standard isolation procedure used by most groups today and the one described in this chapter.

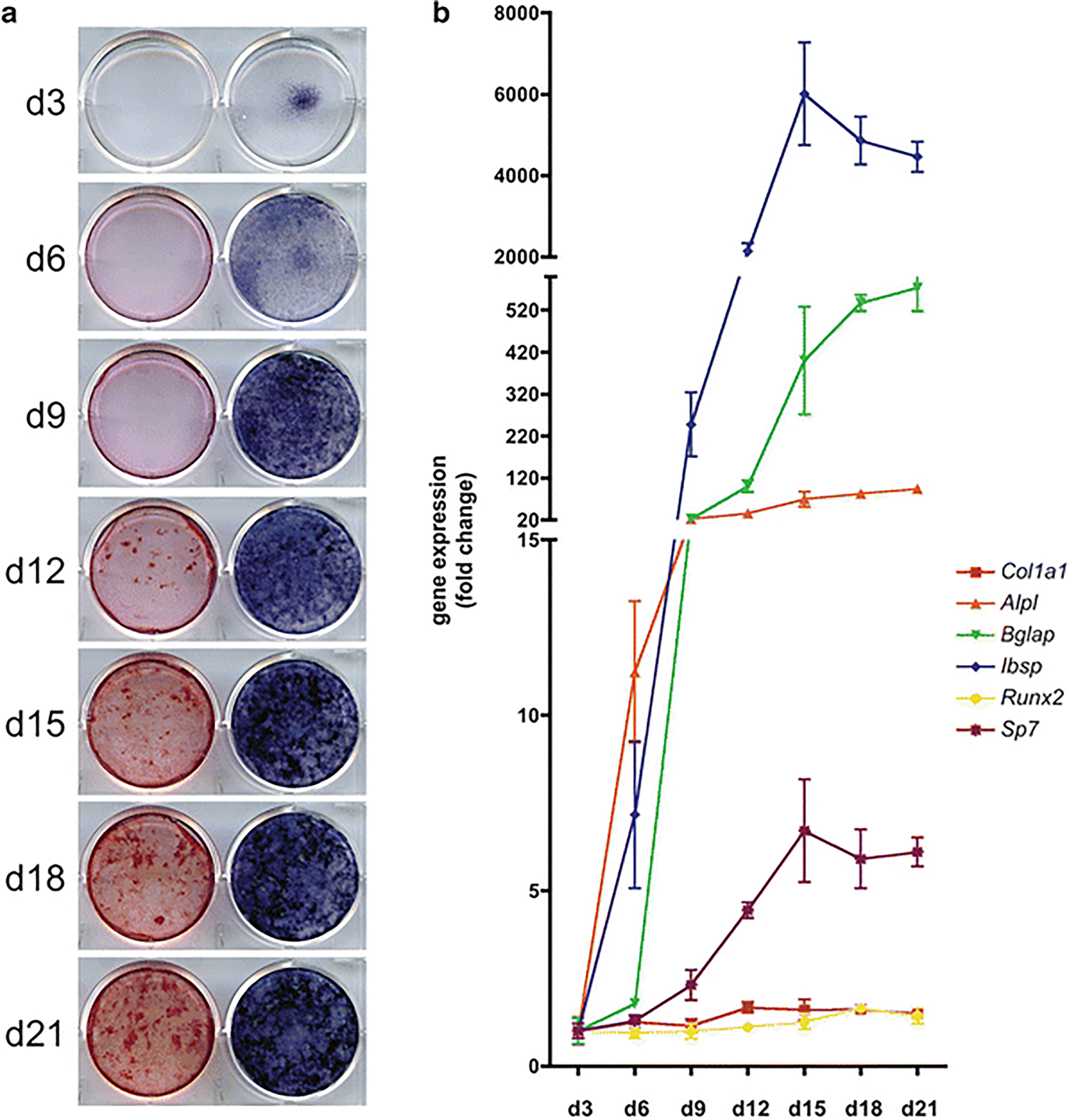

Because these cells are able to proliferate and synthesize a mature mineralized collagen matrix in vitro, they make an appealing experimental model system for testing how a given factor, gene product or small molecule inhibitor for example, may affect this process. While some cell lines, especially MC3T3 E1, also provide a good model for the study of osteoblast maturation, it is, at times, beneficial to use primary cells isolated from genetically altered mice [21]. Cells from floxed mice, for example, can be infected with virus encoding Cre recombinase to delete, in vitro, a portion of DNA flanked by loxP sites. The same cells, infected with a control virus, offer a “wild type” control for comparison in downstream applications such as the maturation assay. Over the course of maturation in vitro, typically 21–28 days, the cells will express maturation “marker” genes such as those described above and begin to build a mineralized bone matrix. The efficiency of this process can be monitored and compared among experimental groups and conclusions can be drawn with regard to how specific factors or growth conditions affect this process. It should be kept in mind, however, that this is a heterogeneous cell population comprised of osteoblasts that were likely at different stages of the maturation process upon isolation. Additionally, there are likely to be some contaminating fibroblasts or periosteal progenitor cells present in the population. Measurements of gene expression, therefore, should be interpreted as averages of expression from all cells in the population. Regardless of this heterogeneity, when cultured in appropriate conditions, the cultures as a whole are very efficient at synthesizing a mineralized bone matrix as a result of enhanced expression and secretion of osteoblastic ECM marker genes making them a suitable in vitro model of bone formation. It should also be noted that while the genes described in this chapter are those most widely accepted as “markers” of osteoblast maturation, a number of genomic screening studies have identified others [22–26]. In this chapter, we will not only describe the procedure for isolation of primary calvarial osteoblasts from neonatal mice, but also describe the culture conditions necessary for inducing the maturation of these cells in vitro with detailed staining protocols for detection of alkaline phosphatase and mineralization of the bone matrix (Fig. 1). A brief description of the procedure for adenoviral transduction of these cells is also provided.

Fig. 1.

In vitro maturation of mouse primary calvarial-derived osteoblasts. Osteoblasts isolated from the calvaria of P4 mice were seeded at 10,500 cells/cm2 in 6-well plates, grown to confluence and, subsequently, cultured in osteogenic media until harvest on the indicated days. Cells were then stained for the presence of alkaline phosphatase (right) or matrix mineralization (left) (a). Gene expression analyses were also performed via reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR for the indicated genes (b) (Color figure online)

2. Materials

2.1. Isolation of Osteoblasts from Neonatal Mouse Calvaria

Neonatal mice from postnatal age (P) 2–5 days (see Note 1).

Dissection scissors, fine forceps (Dumont #5), and standard forceps with blunt, serrated ends. These should be cleaned well with 70 % ethanol prior to use.

Sterile 10 cm petri dishes.

Sterile cell scraper.

Sterile specimen cup (120 ml capacity) with screw cap. Alternatively, a sterile 50 ml polypropylene centrifuge tube could be used.

Sterile 70 μm cell strainers.

Sterile 50 ml polypropylene centrifuge tubes.

75 cm2 cell culture flask, tissue-culture treated with vented cap.

Sterile 1× Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4.

Collagenase A solution: Dissolve Collagenase A (Roche) to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml in Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium (Gibco) or MEM α supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Make fresh and filter-sterilize.

Complete culture media: MEM α supplemented with 10 % FBS (do not heat-inactivate), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

2.2. Mouse Calvarial Osteoblast Culture and Maturation Assays

0.05 % Trypsin-EDTA solution.

Tissue-culture treated polystyrene multi-well plates (12-well and 6-well) (see Note 2).

Osteogenic media: Complete culture media with 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate (see Note 3). Filter-sterilize.

1× Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4.

4 % Paraformaldehyde in 1×PBS.

Double distilled water (ddH2O).

1-Step NBT/BCIP solution (Pierce Thermo Scientific).

Alizarin red S solution: 1 % Alizarin red S in 95 % ethanol, store at room temperature.

2.3. Adenoviral Transduction of Mouse Calvarial Osteoblasts

10 mg/ml Polybrene stock solution (see Note 4).

Adenoviral particles (see Note 5).

Complete culture media (defined above in Subheading 2.1) minus antibiotics.

Complete culture media.

3. Methods

3.1. Isolation of Osteoblasts from Neonatal Mouse Calvaria

Euthanize neonatal mice via an approved IACUC method and proceed immediately with the protocol to avoid loss of cell viability.

From this point forward, all steps should be carried out in a Class II biological safety cabinet using sterile technique.

Douse the head and upper body in 70 % ethanol and decapitate using scissors. Place the head in a sterile petri dish.

Grasp each head with fine forceps placed ventrally and through the back of the head. Using blunt-ended forceps, peel the skin away from the top of the head toward the nasal bone revealing the calvaria. Cut along the edges of the parietal bones and place in a second petri dish with sterile PBS.

Using a small cell scraper, gently remove any loose connective tissue from the calvaria and transfer cleaned calvaria to a third petri dish with sterile PBS.

Carefully transfer the calvaria to a sterile specimen cup containing 10 ml of the 1 mg/ml Collagenase A solution, cap the cup tightly, and place in a 37 °C shaking water bath set at 70–80 rpm for 20 min.

Remove the specimen cup from the water bath and spray liberally with 70 % ethanol before reentering the biological safety cabinet. Discard the cells liberated during the first digest by aspirating the Collagenase A solution. Care should be taken to avoid touching the calvaria.

Add another 10 ml of the 1 mg/ml Collagenase A solution, cap the cup tightly, and place in the 37 °C shaking water bath for another 20 min.

Repeat steps 7 and 8, only this time incubate for 30 min in the 37 °C shaking water bath.

Remove the specimen cup from the water bath and spray liberally with 70 % ethanol before reentering the biological safety cabinet. Collect the Collagenase A solution (digest 3) with a sterile 10 ml pipette and dispense over a 70 μm cell strainer positioned over a 50 ml conical tube. Pellet the cells by centrifugation. Remove the supernatant by aspiration and resuspend the cells in 15 ml of complete culture media. Plate all of the cells in a 75 cm2 cell culture flask with vented cap and culture at 37 °C with 5 % CO2.

Add another 10 ml of the 1 mg/ml Collagenase A solution to the specimen cup, cap the cup tightly, and place in the 37 °C shaking water bath for another 30 min.

Repeat steps 10 and 11 two additional times to collect cells from digests 4 and 5.

Culture the cells to 70–80 % confluence prior to passaging (see Note 6).

3.2. Mouse Calvarial Osteoblast Cultures for Maturation Assays

Trypsinize and count the cells. Using complete culture media, plate the cells between 10,000 and 12,000 cells/cm2 in 6- or 12-well plates and grow to confluence. See Subheading 3.5 if adenoviral transduction of the cells is required.

Replace the media with osteogenic media and change the media every 2–3 days as needed throughout the maturation assay.

Harvest the cells every 2–3 days throughout the length of the maturation assay for isolation of mRNA (see Note 7) (Fig. 1) or staining as described below. At this point, all procedures can be performed on the benchtop or in a chemical fume hood as sterile conditions are no longer required.

3.3. Alkaline Phosphatase Staining of Mouse Calvarial Osteoblast Cultures

Wash cells once in 1× PBS (see Note 8).

Fix cells in 4 % paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 10–15 min. Perform this step in a chemical fume hood.

Wash cells three times in ddH2O.

Add a volume of 1-Step NBT/BCIP solution equivalent to the volume used when culturing the cells. Incubate at room temperature on a rocking platform for 20 min (see Note 9).

Remove NBT/BCIP solution and wash cells three times in ddH2O. Allow cells to air-dry and store at room temperature away from light (Fig. 1).

3.4. Alizarin Red S Staining of Mouse Calvarial Osteoblast Cultures

Follow steps 1 and 2 above.

Wash cells three times in 1× PBS.

Add a volume of Alizarin red S staining solution equivalent to the volume used when culturing the cells. Incubate at room temperature on a rocking platform for 20 min (see Note 9).

Remove Alizarin red S solution and wash cells three times in 1× PBS. Allow cells to air-dry and store at room temperature away from light (Fig. 1).

3.5. Adenoviral Transduction of Mouse Calvarial Osteoblasts (Optional)

Trypsinize and plate cells in a format compatible for the desired downstream application (if carrying out a maturation assay subsequent to infection, plate cells as specified in Subheading 3.2). Culture cells to roughly 70–80 % confluence.

- Prior to infection, determine the amount of adenovirus that will be needed for the desired MOI (multiplicity of infection) (see Note 10) as follows:

Remove culture media and add fresh media without antibiotics at half the volume normally used for the particular culture vessel. Add an appropriate amount of Polybrene to the media such that the final concentration is between 5 and 10 μg/ml. Gently swirl the media to mix. Add the adenovirus directly to the media and, again, swirl to mix. Alternatively, if multiple wells/plates are to be infected with the same virus, it may be preferential to first dilute the Polybrene and virus in the total amount of media needed and, subsequently, aliquot the appropriate amount per well/plate.

Incubate cell cultures at 37 °C with 5 % CO2 in an incubator approved for Biosafety Level 2 agents. Remove virus and add complete culture media 24–48 h post-infection. If waiting 48 h, it is best to add an additional volume of complete culture media to the culture vessel at 24 h.

Continue to culture cells at 37 °C with 5 % CO2 until desired endpoints.

4. Notes

A litter of 6–8 mice should yield approximately 4 × 106–5 × 106 cells after 3–5 days in culture. This is sufficient for setting up a standard maturation assay with staining and isolation of mRNA as endpoints.

We recommend using 12-well plates for staining and 6-well plates for the collection of mRNA or protein during the maturation assay. This plating format can be scaled up, if desired, but scaling down is not recommended as it is very difficult to plate the cells evenly in a culture vessel smaller than one well of a 12-well plate. Additionally, the amount of mRNA obtained from a culture less than that in one well of a 6-well plate may not be sufficient for the desired number of qPCR reactions. We have not noticed a difference among plate manufacturers with regard to their suitability for this assay.

The addition of ascorbic acid to the media is essential for osteoblast maturation and bone nodule formation as it promotes the synthesis and secretion of collagen [18, 27, 28]. Additionally, nodules will not mineralize without the addition of an organic phosphate, such as β-glycerophosphate.

The addition of Polybrene to the culture media along with the addition of virus is documented to enhance adenovirus transduction efficiency. Polybrene is a cationic polymer thought to neutralize the charge of the cell membrane, thereby, reducing repulsive forces between the virus and target cell surface. Polybrene can be purchased from many vendors as a ready-to-use solution or as a powder that should then be diluted in sterile nuclease-free water to the desired stock concentration.

We regularly isolate primary osteoblasts from floxed mice and use adenovirus expressing Cre recombinase to delete, in vitro, a segment of DNA flanked by loxP sites. We purchase ready-to-use Ad5-CMV-Cre-GFP or Ad5-CMV-Cre and control Ad5-CMV-GFP adenoviral particles from Vector Development Laboratory (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX). We have also had success with virus purchased from Vector Biolabs (Philadelphia, PA). Vector Biolabs has many pre-made adenoviruses convenient for use in overexpression studies.

Culturing cells to this density may require anywhere from 3 to 7 days depending on the initial number of calvaria used for the isolation. During this time, the growth media should be changed every 3 days and the cells should not be grown to confluence as this may cause them to begin to mature. Morphologically, the cells should appear large and polygonal in shape with a single, large nucleus. Keep in mind that this is a heterogeneous population, however, and there may be contaminating fibroblasts or periosteal osteoprogenitors in the cultures. In our experience, though, this does not inhibit the osteogenic maturation of the cells in downstream applications. We have found that cells can be successfully passaged twice following the initial plating.

For isolation of mRNA, we typically use the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) and QIAshredder. Alternatively, when it is desired to obtain both protein and mRNA from the same cultures, we use the PARIS kit (Life Technologies) with subsequent concentration and cleanup of mRNA via the RNeasy MinElute Cleanup kit (Qiagen). When using the PARIS kit, however, it is usually necessary to break up the mineralized extracellular matrix that these cultures generate by passing the lysate through a syringe needle several times prior to adding it to the column.

Care should be taken to avoid touching the cell cultures during the staining procedure. Cultures at later time points will have a mineralized extracellular matrix that may easily lift from the plate while adding and aspirating liquid from the wells.

The length of time for staining can range from 15 to 60 min. Cultures from all time points within an experiment should be incubated with the staining solution for the same amount of time. Keep in mind that the earlier time points will express significantly less alkaline phosphatase and have little, if any, detectable mineral in the matrix.

MOI is the number of viral genomes per cell in the given culture. When using a particular virus for the first time, it is recommended to test a range of MOIs (0, 50, 100, 200, 500 and 1,000, for example). Control and experimental viruses should be used at equivalent MOIs within an experiment. When calculating the volume of a given virus to be used, be sure to use the value corresponding to the titer (pfu/ml) and not the total particles/ml. The virus stock may first need to be diluted 1:10, or even 1:100, in PBS to reach a suitable working stock concentration.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Yongchun Zhang, Donna Hoak, and Tzong-jen Sheu for technical assistance. This work was supported by Public Health Service Grants RO1 AR053717, P50 AR054041, and P30 AR061307.

References

- 1.Jensen ED, Gopalakrishnan R, Westendorf JJ (2010) Regulation of gene expression in osteoblasts. Biofactors 36(1):25–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komori T (2011) Signaling networks in RUNX2-dependent bone development. J Cell Biochem 112(3):750–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long F (2012) Building strong bones: molecular regulation of the osteoblast lineage. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13(1):27–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aronow MA, Gerstenfeld LC, Owen TA, Tassinari MS, Stein GS, Lian JB (1990) Factors that promote progressive development of the osteoblast phenotype in cultured fetal rat calvaria cells. J Cell Physiol 143(2):213–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malaval L, Liu F, Roche P, Aubin JE (1999) Kinetics of osteoprogenitor proliferation and osteoblast differentiation in vitro. J Cell Biochem 74(4):616–627 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owen TA, Aronow M, Shalhoub V, Barone LM, Wilming L, Tassinari MS, Kennedy MB, Pockwinse S, Lian JB, Stein GS (1990) Progressive development of the rat osteoblast phenotype in vitro: reciprocal relationships in expression of genes associated with osteoblast proliferation and differentiation during formation of the bone extracellular matrix. J Cell Physiol 143(3):420–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whyte MP (2010) Physiological role of alkaline phosphatase explored in hypophosphatasia. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1192:190–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boskey AL, Maresca M, Ullrich W, Doty SB, Butler WT, Prince CW (1993) Osteopontin-hydroxyapatite interactions in vitro: inhibition of hydroxyapatite formation and growth in a gelatin-gel. Bone Miner 22(2):147–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boskey AL, Spevak L, Paschalis E, Doty SB, McKee MD (2002) Osteopontin deficiency increases mineral content and mineral crystallinity in mouse bone. Calcif Tissue Int 71(2):145–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter GK, Goldberg HA (1993) Nucleation of hydroxyapatite by bone sialoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90(18):8562–8565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hauschka PV, Lian JB, Cole DE, Gundberg CM (1989) Osteocalcin and matrix Gla protein: vitamin K-dependent proteins in bone. Physiol Rev 69(3):990–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferron M, Wei J, Yoshizawa T, Del Fattore A, DePinho RA, Teti A, Ducy P, Karsenty G (2010) Insulin signaling in osteoblasts integrates bone remodeling and energy metabolism. Cell 142(2):296–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fulzele K, Riddle RC, DiGirolamo DJ, Cao X, Wan C, Chen D, Faugere MC, Aja S, Hussain MA, Bruning JC, Clemens TL (2010) Insulin receptor signaling in osteoblasts regulates postnatal bone acquisition and body composition. Cell 142(2):309–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peck WA, Birge SJ Jr, Fedak SA (1964) Bone cells: biochemical and biological studies after enzymatic isolation. Science 146(3650):1476–1477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong G, Cohn DV (1974) Separation of parathyroid hormone and calcitonin-sensitive cells from non-responsive bone cells. Nature 252(5485):713–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCarthy TL, Centrella M, Canalis E (1988) Further biochemical and molecular characterization of primary rat parietal bone cell cultures. J Bone Miner Res 3(4):401–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong GL, Cohn DV (1975) Target cells in bone for parathormone and calcitonin are different: enrichment for each cell type by sequential digestion of mouse calvaria and selective adhesion to polymeric surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 72(8):3167–3171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellows CG, Aubin JE, Heersche JN, Antosz ME (1986) Mineralized bone nodules formed in vitro from enzymatically released rat calvaria cell populations. Calcif Tissue Int 38(3):143–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhargava U, Bar-Lev M, Bellows CG, Aubin JE (1988) Ultrastructural analysis of bone nodules formed in vitro by isolated fetal rat calvaria cells. Bone 9(3):155–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nefussi JR, Boy-Lefevre ML, Boulekbache H, Forest N (1985) Mineralization in vitro of matrix formed by osteoblasts isolated by collagenase digestion. Differentiation 29(2):160–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sudo H, Kodama HA, Amagai Y, Yamamoto S, Kasai S (1983) In vitro differentiation and calcification in a new clonal osteogenic cell line derived from newborn mouse calvaria. J Cell Biol 96(1):191–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck GR Jr, Zerler B, Moran E (2001) Gene array analysis of osteoblast differentiation. Cell Growth Differ 12(2):61–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia T, Roman-Roman S, Jackson A, Theilhaber J, Connolly T, Spinella-Jaegle S, Kawai S, Courtois B, Bushnell S, Auberval M, Call K, Baron R (2002) Behavior of osteoblast, adipocyte, and myoblast markers in genome-wide expression analysis of mouse calvaria primary osteoblasts in vitro. Bone 31(1):205–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishikawa K, Nakashima T, Takeda S, Isogai M, Hamada M, Kimura A, Kodama T, Yamaguchi A, Owen MJ, Takahashi S, Takayanagi H (2010) Maf promotes osteoblast differentiation in mice by mediating the age-related switch in mesenchymal cell differentiation. J Clin Invest 120(10):3455–3465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roman-Roman S, Garcia T, Jackson A, Theilhaber J, Rawadi G, Connolly T, Spinella-Jaegle S, Kawai S, Courtois B, Bushnell S, Auberval M, Call K, Baron R (2003) Identification of genes regulated during osteoblastic differentiation by genome-wide expression analysis of mouse calvaria primary osteoblasts in vitro. Bone 32(5):474–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seth A, Lee BK, Qi S, Vary CP (2000) Coordinate expression of novel genes during osteoblast differentiation. J Bone Miner Res 15(9):1683–1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franceschi RT, Iyer BS (1992) Relationship between collagen synthesis and expression of the osteoblast phenotype in MC3T3-E1 cells. J Bone Miner Res 7(2):235–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterkofsky B (1991) Ascorbate requirement for hydroxylation and secretion of procollagen: relationship to inhibition of collagen synthesis in scurvy. Am J Clin Nutr 54(6 Suppl):1135S–1140S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]