Abstract

Case series summary

This case series describes the clinical findings and surgical intervention of 86 declawed cats; 52 from a shelter or rescue and 34 owned cats. Historical reports from owners and shelter staff included house-soiling, biting behavior, repelling behavior, barbering, lameness, chronic digit infection and nail regrowth. All the cats had fragments of the third phalanx (P3) of varying sizes diagnosed on radiographs. Pathology visible on examination included digital subcutaneous swelling, ecchymosis, malaligned digital pads, ulcerations, exudate, tendon contracture, nail regrowth and callusing. Surgery was pursued in these cases to remove the P3 fragments, relieve tendon contracture and reposition the digital pads with an anchoring suture. Gross findings intraoperatively included fragmented growth of cornified and non-cornified nail tissue, osteophytes on the surface of the second phalanx, deep digital flexor tendon calcification, and both bacterial and sterile exudate. The most common complication 14 days postoperatively was mild (14%) to moderate (1%) lameness. All historical parameters recorded improved in both populations of cats (house-soiling, biting behavior, repelling behavior, barbering, lameness, tendon contracture and chronic digit infection). Postoperatively, 1/47 cats exhibited continued malalignment of two digital pads and there were no reports of long-term postoperative lameness.

Relevance and novel information

Two methods of declawing cats are detailed in the veterinary literature, including partial amputation of P3 and disarticulation of the entire P3 bone. The novel information in this report includes historical and clinical signs of declawed cats with P3 fragments, intraoperative gross pathology, surgical intervention and the postoperative follow-up results.

Keywords: Declaw, declawing, onychectomy, amputation, partial amputation, house-soiling, repelling, contracture

Introduction

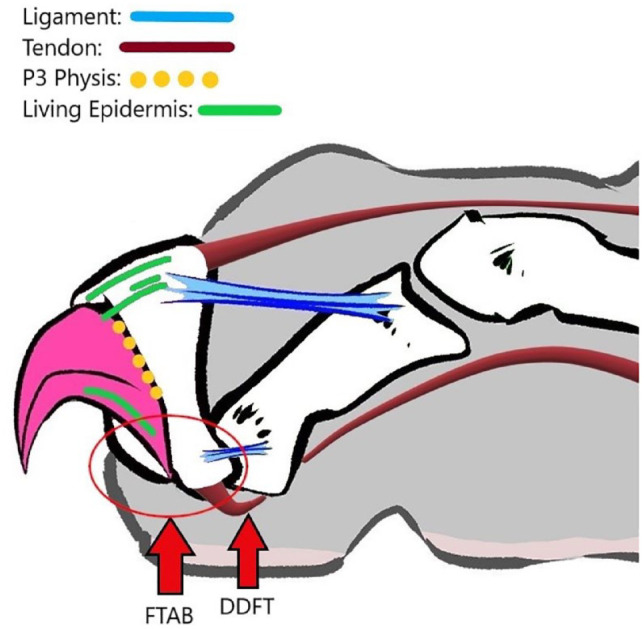

Declawing (onychectomy) involves either a full or partial amputation of the distal phalanx (P3). Both methods are considered acceptable according to the literature. 1 The partial amputation method intentionally leaves a portion of the P3. The most accurate anatomic description of the structure remaining in the published figures (Figure 1) is the flexor tubercle of the articular base (FTAB) or the insertion of the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT).1,2 Disarticulation of the distal phalanx is described with a scalpel blade or CO2 laser with the intention of removing the P3 bone. 1 One study demonstrated the potential for partial amputation with a guillotine, scalpel or laser. 3 Nail regrowth originates from the living epidermis and bone growth from the physis (Figure 1). Leaving any portion of the living epidermis or physis could result in proliferative tissue. 2

Figure 1.

Relevant anatomy of the distal phalanx. Base illustration by Kirstin Watlington

The potential long-term effects of declawing include barbering, 4 chronic back pain, 4 lameness,5,6 tendon contracture5,6 and osteosarcoma formation on P3 fragments. 7 A study published in 2023 demonstrated antebrachial myology in exotic cats that were declawed, resulting in decreased deep digital flexor muscle size and function. 8 Behavioral changes are also documented, such as biting behavior, repelling behavior (RB) and house-soiling (HS). 4 One study demonstrated that declawed cats with P3 fragments had more documented pain and adverse behavior than those without in the long term. 4 There are no current reports examining methods of P3 fragment removal, pre- and intraoperative pathology, and postoperative outcomes.

Case series description

Methods and data collection

Owned, declawed cats were presented for preventive or illness examinations to a single practitioner between 2013 and 2023. The cats from multiple shelters and rescues were presented as part of a ‘paw evaluation’ program. Many of the cats were previously included in a data set evaluating pain and adverse behavior published in 2018. These cats were included in this case series due to the added information surgical intervention could provide. Radiographs were recommended for every declawed patient, whether they had clinical signs or not. Those cats radiographed with P3 fragments that were in good body condition and free from or had well-managed metabolic disease were offered surgical excision. All cats included were free from ectoparasites and required to be current on core vaccinations with a current retroviral status. The historical information was obtained by a veterinary technician and verified by the author.

HS (urine or feces) in owned cats was determined by one or more episodes documented in the medical history in the previous year. Shelter cats with HS reports were based on the reason for surrender or documented episodes of litter box avoidance while in a cage or free-roaming room.

Biting behavior was determined by verbal warning from the owner or shelter staff that the cat will bite, consultation with a veterinarian about biting behavior or a pre-existing medical record alert entered by handling technicians, groomers or shelter staff indicating that the cat was prone to biting during light restraint.

RB refers to a documented incident by the owner reporting hissing, growling, vocalizing, swatting and/or lunging toward a person when at home or during a veterinary visit. Cats in a shelter setting were determined to have RB based on similar behaviors involving relinquishing owners or shelter staff.

Barbering behavior was recorded when there was no evidence of a primary skin condition causing pruritus. A full range of diagnostics was not pursued in all barbering cats. However, all cats included in the study were required to be current on topical monthly veterinary-obtained flea prevention.

All cats received a physical examination and historical review to evaluate other causes for the HS, biting, RB and barbering, along with preoperative complete blood count, serum chemistry, total thyroxine and urinalysis with ultrasound-guided cystocentesis and examination of the bladder for those with HS.

Lameness was reported by the owner and verified on physical examination by the author. Lameness included toe-touching or non-weight-bearing on one or more limbs. Patients with gait abnormalities, such as a short stride, palmigrade or plantigrade stance, decreased activity or inability to jump were not included in this category.

A single slightly obliqued, lateral radiograph of the distal declawed limbs was obtained (Figure 2). The patient was restrained in a right lateral position and the limbs undisturbed, naturally falling into the correct position. If the view obtained was not sufficiently oblique, the patient was rotated into a left lateral position. Sedation was used in any patient with RB, uncomfortable with this restraint or too painful. All images were obtained and evaluated by the author. All findings were recorded in the medical record and transferred to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

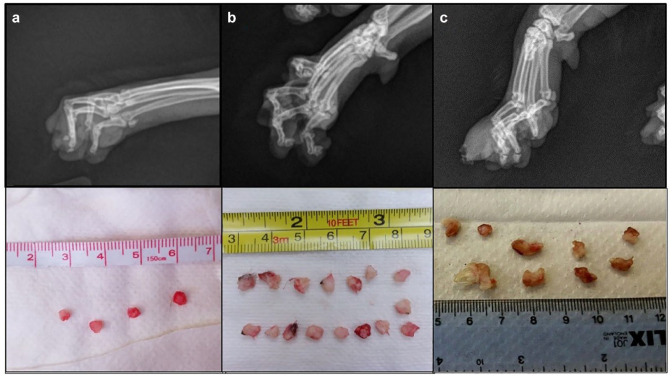

Figure 2.

(a) Example of small FTAB fragments on radiography and after excision; (b) caudal deviation of FTAB fragments on radiography and after excision; (c) larger fragments involving the articular base, articular facet and portions of the unguicular hood and one with cornified nail on radiography and after excision. FTAB = flexor tubercle of the articular base

Data are n/n (%)

Case management

Pain management was initiated in 15 cats preoperatively including: gabapentin 10–20 mg/kg PO q12h, 1 mg/kg robenacoxib (Onsior; Elanco) PO q24h for 3–6 days and/or buprenorphine 0.02–0.03 mg/kg Oral Transmucosally (OTM) q8h–q12h. Four patients with chronic digital infections received antibiotics (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 12.5 mg/kg PO q12h) for at least 2 weeks preoperatively, based on culture and antibiotic sensitivity results.

Pre-medications varied depending on the age, health and temperament of the patient, the most common being dexmedetomidine (Dexdomitor; Zoetis), midazolam and butorphanol. Intravenous (IV) catheters and endotracheal tubes were placed, along with monitoring of ECG and heart rate, EtCO2 and respirations, body temperature, SpO2 and indirect blood pressure. Propofol IV to effect was used for induction and maintenance anesthesia with isoflurane gas.

Between 2013 and 2020, cefovecin (Convenia; Zoetis) 8 mg/kg SC was administered at induction to the cats that were not already on antibiotic therapy for pre-existing infections. In the interest of improved antibiotic stewardship, this was discontinued in later procedures. One case that required extensive exploration of the digits received amoxicillin + sulbactam 20 mg/kg IV at induction, then q8h for 48 h. Preoperative pain management was instituted at induction with buprenorphine (Simbadol; Zoetis) 0.24 mg/kg SC. Once anesthetized, bupivacaine 0.75 mg/kg was used as a ring block (before 2016) or a four-point block in accordance with the previously established protocol by Enomoto et al.9,10 The patient was placed in dorsal recumbency, the digits shaved to the carpus and limbs secured to the surgery table. A tourniquet with light pressure was placed proximal to the elbow joint or distal to the hock in pelvic limb procedures. The digits were scrubbed with chlorhexidine and isopropyl alcohol.

An incision was made 3–5 mm dorsal to each paw pad in an arc following the curvature of the pad. The skin and pad were dissected away from the second phalanx (P2) bone using a scalpel blade. If a joint space was still present between P2 and the P3 remnant, it was incised along with the collateral ligaments. Smaller fragments containing only the FTAB were dissected away from the cartilage of P2 or from within the groove of the DDFT. All P3 fragments were still attached to the DDFT. Any other abnormal structures or tissue were removed at that time. Excess skin was removed as needed to reduce dead space.

Those patients with tendon contracture were treated by surgically exploring the previously declawed digit, whether fragments were seen on radiographs or not. If a P3 fragment was present, it was surgically excised, ensuring the DDFT had no attachment to surrounding structures. In those cats with contracture that did not have P3 fragments, the DDFT attachment was dissected and 3–4 mm of the tendon was excised.

The digital pads were aligned with the end of P2 by suturing it to the surrounding subcutaneous tissue before closure. A 4-0 undyed fast-absorbing polyglycolic acid (PGA) suture was used (poliglecaprone used in two cats) with one of two methods as illustrated in Figure 3. These provided increased stability postoperatively by attempting to anchor the digital pad over the P2 cartilage. The purse-string suture was performed more frequently in heavier cats or in cases of increased dead space; however, most were completed with the single suture method. Incisions were closed with either a simple continuous or simple interrupted pattern (larger incisions). Once isoflurane was discontinued and the patient’s blood pressure was stable, they were administered robenacoxib 1 mg/kg SC. Each foot was wrapped with three layers of 1/8-inch tube gauze and cohesive bandage to the mid antebrachium, with hospital tape at the proximal edges, for 24 h. The IV catheter was left in place overnight to facilitate administration of the sedative for bandage removal the next day or for rescue analgesia if needed. Patients were evaluated by a trained veterinary technician for pain every 30 mins for the first 2 h then every hour for 48 h while staff was present in the clinic, using the Colorado State University Feline Acute Pain Scale. Rescue analgesia was required in three cats within the first 30 mins of recovery using a ketamine constant-rate infusion (CRI) for 24 h.

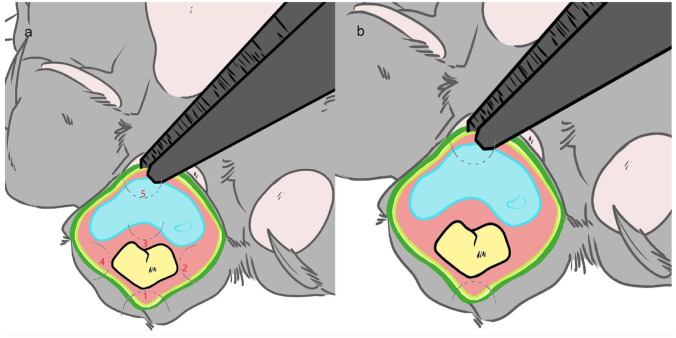

Figure 3.

Two methods of anchoring the digital pad over the cartilaginous end of the second phalanx: (a) purse-string-like suture is placed to reduce dead space and help align the digital pad when a larger incision or extensive exploration of the digit is needed; and (b) the anchoring suture used most with smaller incisions to aid in aligning the digital pad. Illustration by Kirstin Watlington

Data are n/n (%)

Postoperative pain management included robenacoxib 1 mg/kg PO q24h for 3 days starting 24 h after the injection, additional buprenorphine 0.24 mg/kg SC q24h on days 2 and 3, buprenorphine 0.02–0.03 mg/kg OTM q8–12h for days 4–8 and gabapentin 10–35 mg/kg PO q8h–q12h for at least 30 days. Patients were discharged on the third day with instructions to confine the patient to a large dog crate or small room to minimize jumping and running for 7 days. The recommended litter, if accepted by patients, was either shredded paper or a soft, fine-textured, non-clumping litter for 2–4 weeks. The sutures were allowed to dissolve and were not removed.

The 86 cats (45 castrated males, 41 spayed females; age range 10 months to 15 years) in the population were either domestic shorthairs or domestic longhairs and one Savannah; 34 cats were owned and 52 cats were from shelters. Two owned cats were positive for feline immunodeficiency virus. All owned cats were kept exclusively indoors. The outdoor access of shelter cats before relinquishment could not be reliably documented. In total, 12 cats were declawed on all four limbs. Excision of fragments on all four limbs was completed in a single procedure in 11/12 cats; one cat had a staged excision, with thoracic limbs first then pelvic limbs 2 months later.

The physical examination and historical findings for all cats are summarized in Table 1. The reliability of reason for relinquishment was low so an additional ‘unknown’ category was added. Gross pathology pre- and intraoperatively is summarized in Figure 4 and Table 2. Cloudy, white, yellow or gray fluid draining or found subcutaneously near the location of P3 fragments were deemed to be exudates without cytology. Aerobic bacterial culture with antibiotic sensitivity was performed. A β-hemolytic Streptococcus species was cultured in 4/6 samples, sensitive to β-lactam antibiotics, with two cultures resulting in no growth.

Table 1.

Historical and physical examination findings preoperatively

| History | Owned cats (n = 34) | Shelter cats (n = 52) | Total (%) (n = 86) | Shelter unknown |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS | 9 (26) | 19 (37) | 33 | 31/52 |

| Biting | 7 (21) | 13 (25) | 23 | 0 |

| RB | 6 (18) | 5 (10) | 13 | 0 |

| Nail regrowth | 8 (24) | 2 (4) | 12 | 0 |

| Barbering | 4 (12) | 4 (8) | 9 | 0 |

| Lameness | 6 (18) | 2 (4) | 9 | 0 |

| Chronic infection | 4 (12) | 0 (0) | 5 | 0 |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise indicated

HS = house-soiling; RB = repelling behavior

Table 2.

Preoperative and intraoperative findings

| Gross findings | All cats (n = 86) |

|---|---|

| Callus | 45 (52) |

| Contracture | 29 (34) |

| Non-cornified regrowth | 26 (30) |

| Cornified regrowth | 22 (26) |

| SC swelling | 13 (15) |

| Erythema | 8 (9) |

| Exudate | 6 (7) |

| DDFT calcification | 2 (2) |

| Osteophyte | 3 (3) |

| Ulcerations | 1 (1) |

Data are n (%)

DDFT = deep digital flexor tendon; SC = subcutaneous

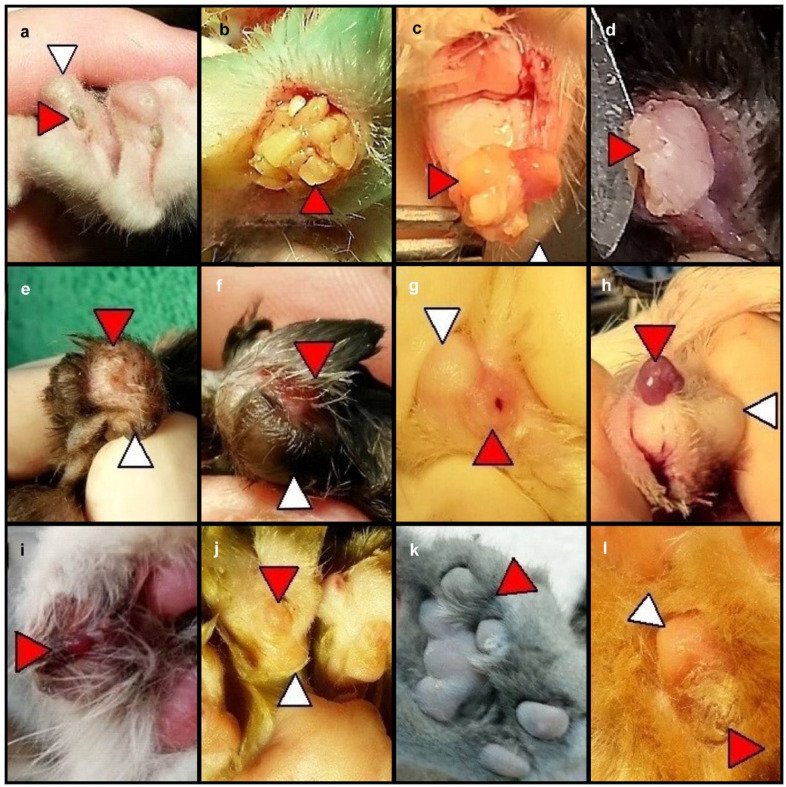

Figure 4.

Pre- and intraoperative findings: (a) externally visible nail regrowth; (b) cornified nail regrowth; (c) non-cornified nail regrowth; (d) osteophytes on the second phalanx (P2); (e) subcutaneous swelling; (f) epidermal ecchymosis; (g) ulceration; (h) sterile exudate; (i) bacterial exudate; (j) skin callus due to P2–pad malalignment; (k) contracture; and (l) callus over atrophied portion of paw pad. Red arrowheads denote lesions; white arrowhead denotes the digital pad

All cats with non-cornified or cornified nail regrowth subcutaneously or penetrating the skin had larger fragments (⩾5 mm), usually including at least the palmar flange of the coronary horn and/or the unguicular hood. The cats with subcutaneous swelling found preoperatively had either non-cornified or cornified nail regrowth at that location.

There was a subset of cats that did not have radiographic evidence of fragments in all declawed digits that did have tendon contracture. All digits were explored in these cases. The digits with tendon contracture had either miniscule (⩽2 mm) FTAB fragments or no fragments at all. The exact number was not quantified.

The images in Figure 5 were obtained using dental radiography to demonstrate the variable appearance of osteophytes vs P3 fragments. Tissue from one patient that had hard, irregularly textured projections removed from the P2 cartilage–bone junction on two digits was evaluated by a veterinary pathologist and described as fibrovascular tissue with a center of ossification (Figure 6). These were assumed to be osteophytes. The P3 fragments evaluated were also characterized as fibrovascular tissue with central ossification.

Figure 5.

Radiographs of tissue submitted for histopathology. The red arrowhead denotes projections on the bone–cartilage junction comprising bone surrounded by fibrovascular tissue. White arrows denote distal phalanx fragments comprising bone surrounded by fibrovascular tissue

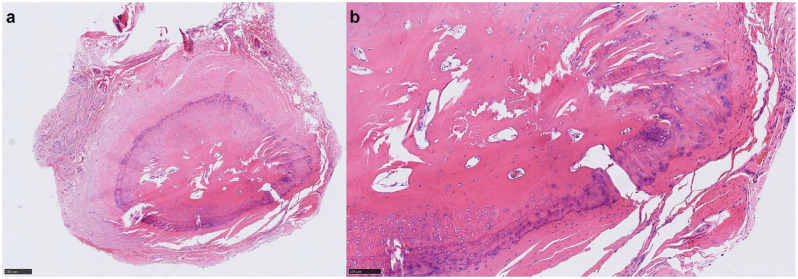

Figure 6.

Histopathology of a bony lesion at the second phalanx cartilage–bone junction described as a fibrovascular stroma with central ossification Bar in (a) = 100 micrometers and bar in (b) = 100 micrometers

All 86 cats recovered from surgery without serious complications. One owned patient experienced respiratory arrest and momentary cardiac arrest during surgical preparation and recovered without incident after cardiopulmonary resuscitation and supportive care. This patient was later diagnosed with suspected bacterial endocarditis via proBNP elevation and echocardiogram. The cat was treated with an antibiotic for 8 weeks based on the culture and sensitivity results of the infected digit. The proBNP level and echocardiography findings improved in week 8. The procedure was completed successfully, and the patient recovered without incident. It could not be determined if the endocarditis was a result of the chronic digital infection or if it was responsible for the arrest during anesthesia.

One patient from a rescue that had P3 fragments in all four limb digits had persistent postoperative pain that required buprenorphine 0.02 mg/kg OTM q8h for 14 days and gabapentin 35 mg/kg PO q8h for 120 days. This patient originally presented with lameness and back pain.

Two shelter cats were examined 5 days after discharge for chewing at incision sites. On physical examination, the cats resisted distal limb handling. Due to concern for pain leading to chewing, the frequency of buprenorphine was increased from q12h to q8h and gabapentin dosing from 10 mg/kg to 20 mg/kg q8h without improvement after 2 days. A poliglecaprone 4-0 suture was used in these two patients. They were both sedated and the remaining remnants of sutures were removed, considering the possible discomfort from the stiffer monofilament suture as the cause. The incision sites were healed so no sutures were replaced, and the cats did not continue chewing the sites after removal. The use of surgical adhesive was also attempted on one patient with small incision sites with a similar result. The softer 4-0 undyed fast-absorbing polyglycolic acid sutures were used in future cases without further reports of incision site chewing. The use of an Elizabethan collar was needed for one patient that had fragments excised from both thoracic and pelvic limbs for 7 days due to over-grooming the distal limbs between the elbow and carpus with mild lameness. Gabapentin was increased in frequency to q8h and buprenorphine continued for an additional 5 days.

The 2-week postoperative follow-up included a physical examination of the digits for all owned cats and four shelter cats. The follow-up for 48/52 shelter cats was completed via telephone or email consultation, with shelter staff using videos or photos as needed. The complications for all cats included mild (12/86) to moderate (1/86) lameness. Mild lameness was defined in this case as shorter stride and occasional toe touching without loss of normal behaviors (ie, eating, drinking, socializing). Moderate lameness was defined as consistent toe touching and limping without loss of other normal behaviors. The recommendation for patients experiencing lameness was to increase the gabapentin dosing by an additional 5 mg/kg and administer buprenorphine 0.03 mg/kg OTM q8h–q12h for another 4–6 days. If this was ineffective within 24–48 h, robenacoxib 1 mg/kg PO q24h for 3–6 days was prescribed. Follow-up phone calls were completed daily with owners or shelter staff until the lameness resolved.

Long-term (⩾2 months) postoperative follow-up was available for 47/86 cats – 34 owned and 13 sheltered. The follow-up for all owned cats and one shelter cat was completed by physical examination in the clinic. The follow-up for 12/13 shelter cats was completed via telephone or email, with photos and videos as necessary. Of the 52 shelter cats, 39 were adopted without return when attempts were made via telephone or email to follow-up. Postoperative improvements are summarized in Table 3. One patient that had surgical excision on all four feet had two digital pads that did not completely align over the distal P2 found on examination. The two-bite anchoring suture was used in this patient.

Table 3.

Postoperative improvements ⩾2 months

| History | Owned cats | Shelter sats | Adopted/FU unavailable |

|---|---|---|---|

| HS | 6/9 (67) | 4/7 (57) | 12/19 (63) |

| Contracture | 10/10 (100) | 9/9 (100) | 10/19 (53) |

| Biting | 2/7 (43) | 5/8 (63) | 5/13 (38) |

| RB | 4/6 (67) | 5/5 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Barbering | 4/4 (100) | 3/3 (100) | 1/4 (25) |

| Lameness | 5/6 (83) | NA | 2/2 (100) |

| Chronic infection | 4/4 (100) | NA | NA |

Data are n (%)

FU = follow-up; HS = house-soiling; NA = not available; RB = repelling behavior

Discussion

In this case series, several abnormalities were documented in declawed cats with P3 bone fragments. Most of the cats with pathology improved with surgical intervention. Those that did not improve may have had persistent pain (eg, maladaptive pain, neuropathic pain), conditioned behaviors from previous pain requiring counterconditioning measures and/or behaviors unrelated to the P3 fragments or declaw status.

Several limitations affected the ability to obtain accurate histories and follow-up. In total, 52 cats were sheltered with limited medical history available before relinquishment. Several cats were evaluated immediately on entrance into the shelter without time to assess their habits. Most medical history obtained came from shelter staff reporting, necessitating an ‘unknown’ category for the HS cases. Several variables could complicate adding a shelter cat to this category, namely inaccurate reasons for relinquishment, as many shelters involved would not accept cats for HS, the high level of stress in shelter settings for cats and the complex nature of HS. An accurate history and follow-up for all cats would contribute more valuable insight to behaviors and improvements.

Behaviors such as biting or RB can be multifactorial, including the potential for chronic pain either in the limbs or, as previously reported, along the back. 4 One possibility for the lack of improvement in biting behaviors might be related to ongoing disrespectful handling or other deficiencies in care. The marked improvement in RB may be due to pain relief and/or anxiolytic properties associated with gabapentin use. There is no way to accurately determine which effect was more likely.

Two surgical procedures in this series were completed using 4-0 poliglecaprone sutures for skin closure, one in a simple interrupted pattern and the other in a simple continuous pattern. Both patients exhibited discomfort leading to self-mutilation of the surgery sites despite more aggressive pain management. This led to the use of the softer, braided 4-0 fast-absorbing PGA suture for future cases. After this transition, there were no further complications related to self-mutilation.

Cefovecin was initially given to patients not already on antibiotic therapy at induction as a preventive measure in the case series. With improving antibiotic stewardship, this practice was discontinued. In most cases where antibiotics are considered, short-term use of a first-line therapy such as amoxicillin instead of a third-generation cephalosporin would be appropriate. Other concerns to address for postoperative infection include antibacterial poliglecaprone sutures, a fast-absorbing monofilament suture and/or burying the sutures. There was no change in postoperative infection observed when cefovecin was discontinued.

Three cats early in the case series required rescue analgesia upon recovery using ketamine CRI 3–5 µg/kg/min IV for 24 h. This was most likely due to ineffective local anesthesia. After the protocol published for a more accurate distal limb four-point block9,10 was incorporated, no further rescue analgesia was required.

The presence of osteophytes is most likely under-reported in declawed cats as they are difficult to identify on traditional radiography. The use of dental radiography is likely needed to accurately diagnose miniscule fragments and osteophytes. The composition of a known P3 fragment within a joint space was the same as a bony structure tightly adhered to the bone cartilage. It is unknown if these structures are truly osteophytes or a P3 fragment ankylosed to the P2.

As declawing cats for non-therapeutic purposes falls out of favor, veterinarians may not have surgical experience with the feline distal limb. Most North American veterinary schools do not offer declawing on their surgical service or provide instruction on the procedure to students; therefore, removing P3 fragments may be a novel experience. The aims of this case series were to provide veterinarians with a tool to address the population of cats that may be experiencing post-declaw pathology, provide new information to those that continue to perform intentional or unintentional partial P3 amputations, and increase awareness of the potential long-term effects of declawing cats.

Conclusions

All declawed cats should be screened on a routine basis for evidence of behavioral changes associated with pain, P3 fragments and associated pathology, tendon contracture and other declaw-related issues. Surgical excision of bony fragments and appropriate multimodal pain management may alleviate pain and associated unacceptable behaviors along with chronic infection.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the veterinary technicians involved in diligently caring for these patients, along with Dr Jennifer Conrad and Dr Jim Jensvold for their guidance, encouragement and support. Thank you to Dr Will Sims at the Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory for the histopathology photos.

Footnotes

Accepted: 28 February 2024

The author declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The author is a volunteer member of the Paw Project, serving as both the Indiana (2014–2017) and Texas (2017–2023) state directors.

Funding: The Paw Project funded 78 out of 86 surgeries and the Feline Medical Center partially funded the submission of this article.

Ethical approval: The work described in this manuscript involved the use of non-experimental (owned or unowned) animals. Established internationally recognized high standards (‘best practice’) of veterinary clinical care for the individual patient were always followed and/or this work involved the use of cadavers. Ethical approval from a committee was therefore not specifically required for publication in JFMS. Although not required, where ethical approval was still obtained, it is stated in the manuscript.

Informed consent: Informed consent (verbal or written) was obtained from the owner or legal custodian of all animals described in this work (experimental or non-experimental animals, including cadavers, tissues and samples) for all procedures undertaken (prospective or retrospective studies). No animals or people are identifiable within this publication, and therefore additional informed consent for publication was not required.

ORCID iD: Nicole K Martell-Moran  https://orcid.org/0009-0000-9419-6697

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-9419-6697

References

- 1. Wadron DR. Onychectomy. In: Norsworthy GD. (ed). The feline patient. 5th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Elsevier, 2018, pp 793–795. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Homberger DG, Ham K, Ogunbakin T, et al. The structure of the cornified claw sheath in the domesticated cat (Felis catus): implications for the claw-shedding mechanism and the evolution of cornified digital end organs. J Anat 2009; 214: 620–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clark K, Bailey T, Rist P, et al. Comparison of 3 methods of onychectomy. Can Vet J 2014; 55: 255–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martell-Moran NK, Solano M, Townsend HG. Pain and adverse behavior in declawed cats. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 280–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cabon Q, Plante J, Gatineau M. Digital flexor tendon contracture treated by tenectomy: different clinical presentations in three cats. JFMS Open Rep 2015; 1. DOI: 10.1177/2055116915597237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gaskin RW, Clarkson CE, Walter PA. Flexor tenectomy: salvage surgery following feline onychectomy. J Feline Med Surg 2023; 25. DOI: 10.1177/1098612X231162478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Breitreiter K. Late-onset osteosarcoma after onychectomy in a cat. JFMS Open Rep 2019; 5. DOI: 10.1177/2055116919842394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martens LL, Piersanti SJ, Berger A, et al. The effects of onychectomy (declawing) on antebrachial myology across the full body size range of exotic species of felidae. Animals (Basel) 2023; 13. DOI: 10.3390/ani13152462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Enomoto M, Lascelles BD, Gerard MP. Defining the local nerve blocks for feline distal thoracic limb surgery: a cadaveric study. J Feline Med Surg 2016; 18: 838–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Enomoto M, Lascelles BDX, Gerard MP. Defining local nerve blocks for feline distal pelvic limb surgery: a cadaveric study. J Feline Med Surg 2017; 19: 1215–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]